Abstract

The evolution of thalidomide as an effective treatment in several neoplasms has led to the search for compounds with increased antiangiogenic and anti-tumor effects, but decreased side-effects. The development of thalidomide analogues which retain the immunomodulatory effects of the parent compound, while minimizing the adverse reactions, brought about a class of agents termed the Immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs). The IMiDs have undergone significant advances in recent years as evidenced by the recent FDA-approvals of one of the lead compounds, CC-5013 (lenalidomide), for 5q-myelodysplasia and for multiple myeloma (MM). Actimid (CC-4047), another IMiD lead compound, has also undergone clinical testing in MM. Apart from hematologic malignancies, these drugs are actively under investigation in solid tumor malignancies including prostate cancer, melanoma, and gliomas, in which potent activity has been demonstrated. The preclinical and clinical data relating to these analogues, as well as ENMD-0995, are reviewed herein.

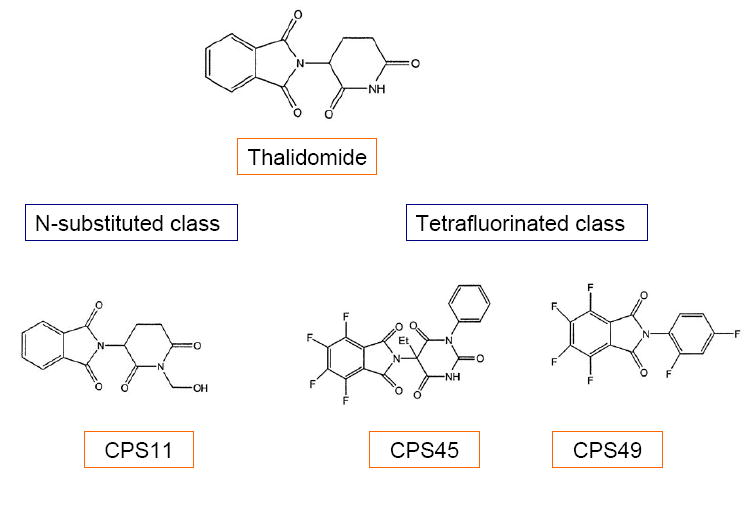

Encouraging results with these thalidomide analogues brought forth synthesis and screening of additional novel thalidomide analogues in the N-substituted and tetrafluorinated classes, including CPS11 and CPS49. This review also discusses the patents and preclinical findings for these agents.

Keywords: Thalidomide analogues, CC-5013, Lenalidomide, CC-4047, CPS49, CPS11, Multiple Myeloma, Prostate cancer

1. INTRODUCTION

The use of angiogenesis inhibitors for the treatment of cancer was first conceptualized over 30 years ago, when Dr. Folkman introduced the idea that angiogenesis is required for continued solid tumor growth [1]. Since then, a number of antiangiogenic agents have emerged for use in cancer therapy. Thalidomide (α -N-phthalimido-glutarimide) has emerged as a potent treatment for several disease entities. Although it was originally marketed in Europe as a sedative and antiemetic, reports of teratogenic effects[2] led to its withdrawal in the market in 1961 [3]. Thalidomide-associated congenital malformations were later thought to result from impaired vasculogenesis and that a similar mechanism may prevent the growth of blood vessels recruited to tumor sites, as confirmed in a rabbit cornea micropocket assay by D’Amato et. al. [4-7]. Further elucidation of the antiangiogenic and anti-inflammatory properties of thalidomide led to its approval in 1998 by the United States Food and Drug Administration after documented efficacy in the treatment of erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL). Apart from its antiangiogenic properties, thalidomide has been shown to inhibit tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF- α)[8], a key chemokine involved in the host immune response that contributes to the pathogenesis of a variety of autoimmune and infectious diseases. Since the approval of thalidomide for ENL, it has been used experimentally in a variety of inflammatory or immunological diseases [9-11], and in several neoplasms [12-16], but has only recently been approved (in May 2006) for use in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) patients, in conjunction with dexamethasone [17].

The combined antiangiogenic and anti-TNF properties of thalidomide have brought forth a wave of enthusiasm due to the perception that inhibition of angiogenesis may be a very promising strategy in cancer treatment. However, thalidomide treatment is accompanied by a number of side-effects, the most common of which is peripheral neuropathy[18], occurring with cumulative doses[19], especially in the elderly[20]. Thromboembolism is also a concern and although occurring at <5% when used as single-agent[21], risk increases from 19% to 28% with combined chemotherapeutic agents[22, 23]. In addition, to alleviate the aforementioned birth defect risk, intensive monitoring of all patients is required[24]. Thus, the search is ongoing for agents with similar or improved potency in comparison with thalidomide, but with improved tolerability. As such, numerous structural analogues of thalidomide have been synthesized by different researchers and tested for their antiangiogenic or anti-TNF- α properties.

Thalidomide analogues have primarily been tested for their ability to inhibit TNF- α [25-27], and several thalidomide analogues have shown increased potency over thalidomide at inhibiting TNF- α in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) bioassays[26]. The involvement of TNF- α in various disorders including cancer cachexia, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) disease, and septic shock has stimulated several investigations and patent applications on the use of thalidomide and its analogues[28]. These compounds, including the isoindolines, as described by Muller et al. were reported to down-regulate TNF- α and other inflammatory cytokines [29-32]. Based on the different chemokine secretion patterns of LPS stimulated PBMC after in vitro testing of different thalidomide analogues, two major classes of compounds have been identified, class I or IMiDs (Immunomodulatory imide Drugs) and class II or SelCiDs (Selective Cytokine Inhibitory Drugs)[33, 34]. The IMiDs demonstrated potent inhibition of TNF- α, as well as inhibition of proinflammatory and apoptotic chemokines such as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), IL-1β, TGF-β, and IL-6 from activated monocytes, along with no evidence of teratogenicity or mutagenesis pre-clinically [35]. These compounds are potent stimulators of LPS induced IL-10, as well as costimulators of T cells that have been partially activated by the T-cell receptor, in the CD8+ subset [33, 36]. Similar to thalidomide, IMiDs showed marked increases in IL-2 and interferon-gamma secretion and upregulation of CD40L expression on anti-CD3 stimulated T cells, resulting in activation of natural killer cells, and thus improving host immunity against tumor cells. These compounds do not inhibit phosphosdiesterase type 4 (PDE4), a phosphodiesterase isoenzyme found in human myeloid and lymphoid lineage cells[37] that functions to maintain cAMP at low intracellular levels, resulting in modulation of LPS-induced cytokines [26]. Representatives of this class are CC-5013 (lenalidomide), CC-4047 (Actimid), and ENMD-0995, which will be discussed in further detail.

In contrast, the compounds in the class of thalidomide analogues known as SelCids have been shown to potently inhibit PDE 4. Although the SelCids have also been shown to inhibit TNF-alpha production and have affected a modest increase in IL-10 production by LPS-induced PBMC, little effect on T cell activation or IL6 was demonstrated. Early reports showed that one of the SelCID analogues (SelCID-3) was consistently effective at reducing tumor cell viability in a variety of solid tumor lines [38]. However, the most promising role of the SelCID compounds appears to be as anti-inflammatory agents. As such, these drugs are currently under investigation for treatment of inflammatory conditions, such as Crohn’s disease. Therefore, this review will focus mainly on the IMiDs, since this class of compounds is in the forefront of anticancer drug discovery and development.

Additional analogues of thalidomide have been synthesized, based on its metabolites. Preliminary screening, using the rat aortic ring assay, showed promising inhibition of microvessel outgrowth by seven of the 118 analogues, four from the N-substituted class and three from the tetrafluorinated class [39]. Of these analogues, N-substituted analogue CPS11 and tetrafluorinated analogues CPS45 and CPS49 has been investigated for in vitro therapeutic efficacy in several neoplasms[40, 41].

2. IMiDs – NOVEL THALIDOMIDE ANALOGUES AS ANTICANCER AGENTS

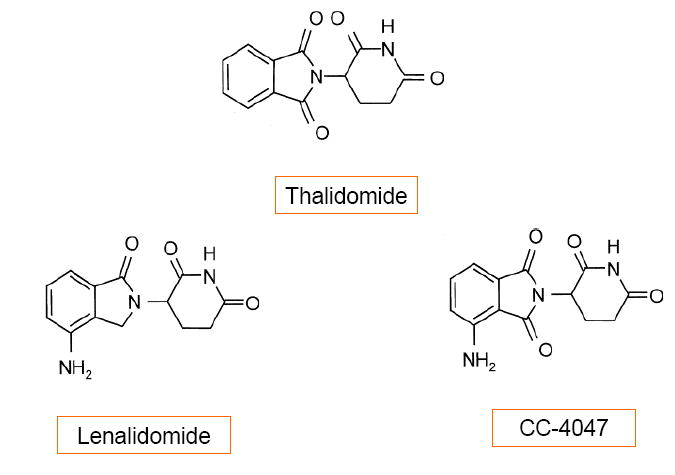

The search for thalidomide analogues with increased immunomodulatory activity and an improved safety profile led to the testing of amino-phthaloyl-substituted thalidomide analogues. These 4-amino analogues, in which an amino group is added to the fourth carbon of the phthaloyl ring of thalidomide (see Table 1 and Fig.(1)), brought about the class termed “IMiDs”. The bioactivities of the IMiDs follow the parent drug thalidomide closely, but with some increase in potency. Fig.(2) summarizes the multifaceted effects of thalidomide and its analogues.

Table 1. Thalidomide and its analogues and properties.

| Thalidomide | Lenalidomide | CC-4047 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-alpha inhibition | + | ++ | ++ |

| T cell costimulation | + | ++ | ++ |

| PDE4 inhibition | - | - | - |

Legend: TNF = Tumor necrosis factor; PDE4 = Phosphodiesterase 4

Fig. (1) . Chemical structure of thalidomide, lenalidomide, and CC-4047.

Fig (2). Mechanism of anti-angiogenic and immunomodulatory actions of IMiDs.

Mechanisms of anti-angiogenic and immunomodulatory functions of IMiDs. Immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs), like thalidomide metabolites upon oxidation, inhibits interleukin 1 β or TNF-alpha – induced activation of IκK, which prevents dissociation of IκBα from NFκB , precluding its nuclear translocation and induction of genes that function in metastasis, angiogenesis, cellular proliferation, inflammation, and protection from apoptosis. IMiDs and thalidomide metabolites also function in T cell activation as its T cell costimulatory function, enhancing T cell proliferation. The activated T cells release interleukin-2 (IL-2) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), which activate the Natural Killer cells (NK cells)

IMiDs as Immunomodulators

The potent inhibition of TNF-alpha using IMiDs was first demonstrated in LPS-induced PBMCs both in vitro and in vivo[34, 42]. It has been shown that relative to the parent drug thalidomide, the analogues inhibited TNF-alpha more potently, as well as inhibiting LPS-induced monocyte IL1-beta and IL12 production, and enhanced the production of interleukin 10 (IL-10). The IMiDs had only partial inhibitory effect on IL-6. When tested in vivo, the amide analogues protected 80% of LPS-treated mice against death from endotoxin-induced shock[42]. Among the earliest studies done on IMiDs had been on multiple myeloma (MM) cell lines. This provided a pathobiologic rationale for the use of IMiDs since TNF-alpha is present locally in the bone marrow microenvironment and induces NF-kappa B-dependent up-regulation of adhesion molecules on both MM cells and bone marrow stromal cells, resulting in increased adhesion[43]. This represents an attractive target for IMiDs in this disease entity. Although TNF-alpha has been shown to only modestly trigger the actual proliferation of MM cells, the subsequent activation of NF-kappa B, a transcription factor that confers significant survival potential in a variety of tumors, also stimulate IL-6 , another important survival signal, in bone marrow stromal cells[44], both of which are potential targets of the IMiDs.

IMiDs as Pro-apoptotic agents

Hideshima et. al. first demonstrated that thalidomide and its analogues induce tumor cell apoptosis, evidenced by increased sub-G1cells or induction of p21 and related G1growth arrest [45]. The IMiDs inhibited the proliferation of chemoresistant MM cells by 20% to 35%, and of Dexamethasone-resistant MM cells by 50%[43]. Enhanced caspase-8 activation, increased sensitivity to Fas induction, reduced expression of cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein-2, and potentiation of the activities of other apoptosis inducers such as TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), has been demonstrated with the IMiDs[46]. This antiproliferative effect was demonstrated in a chromosome 5 deleted (5q-) deletion cell line of Myelodysplasia (MDS) and other hematologic malignancies where the inhibitory concentration of 50% (IC50) was higher for the IMiDs as compared to thalidomide, with induced G0/G1 cell cycle arrest, inhibited Akt and Gab1 phosphorylation, and inhibited the ability of Gab1 to associate with a receptor tyrosine kinase [47].

IMiDs as T cell costimulators

Thalidomide and the immunomodulatory drugs induced proliferation of MM patients’ T cells and interleukin-2 and interferon-gamma production in vitro, but were not cytotoxic to MM cells[33]. These drugs enhanced natural killer cell-mediated lysis of autologous tumor cells[48]. The increase in IL2 and IFN-gamma also upregulates the CD40L expression on T cells when IMiDs were added to anti-CD3 stimulated T cells[33]. Although a greater costimulatory effect on the CD8+ T cell subset compared to the CD4+ T cell subset has been observed in one study [34], another showed similar co-stimulation for CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes which correlated with TNFR2 inhibition[49]. This T cell costimulatory effect of the IMiDs may be paradoxical to the suppression of ligand-stimulated release of apoptotic and inflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF-alpha), and the effects of the IMiDs therefore, similar to thalidomide, results in the clinically divergent effects with regard to specific pathways involved during an inflammatory response or clinical condition [35, 50].

IMiDs as Angiogenesis inhibitors

In vitro assays have demonstrated the antiangiogenic activities of the IMiDs, [4, 51, 52] believed to be secondary to the inhibition of secretion of two angiogenic cytokines, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) from both tumor and stromal cells [4, 5]. Using a human umbilical artery explant assay, the IMiD analogues exhibited a 100-fold increased antiangiogenic potency as compared to thalidomide; [35, 51, 53] albeit, thalidomide requires metabolism in order to have activity in this model. In addition, the IMiD compounds have been shown to inhibit endothelial cell migration and adhesion perhaps due to downregulation of endothelial cell integrins[51]. The antiangiogenic activity of the IMiDs bears important significance in the pathophysiology of hematologic malignancies, like MM, where treatment with thalidomide and IMiDs inhibited the upregulation of VEGF and IL-6 from co-cultures of bone marrow stromal and MM cells[54]. However, the therapeutic utility of the IMiDs may not be limited to hematologic malignancies, based on this antiangiogenic activity.The following sections will discuss the preclinical and clinical development of the three leading IMiD drugs: lenalidomide, CC-4047, and ENMD-9095.

2.1. LENALIDOMIDE (CC-5013)

CC-5013, lenalidomide (α -(3-aminophthalimido) glutarimide; Revlimid®)) is an immunomodulatory analogue that has demonstrated higher potency than thalidomide in the HUVEC (human umbilical vein endothelial cells) proliferation and tube formation assays[55]. The proliferation inhibition responded in a dose-dependent manner with increasing concentrations of the drug. Anti-migratory effects as well as tumor growth inhibition in vivo have also been demonstrated [56]. Metabolism studies with lenalidomide have shown no effect on cytochrome P-450 activity, and no phase I and II metabolism by human liver microsomes or supersomes was detected[53]. In rats and monkeys demonstrated, 50% of lenalidomide is excreted unchanged, and the other 50% is metabolized to hydrolysis metabolites, including N-acetyl and glucose conjugates. In humans, lenalidomide is rapidly absorbed following oral administration, and about 67% is excreted unchanged in urine in less than 24 hours, with a mean half-life of 8 hours. Lenalidomide was well tolerated in healthy volunteers with only minor adverse immunologic events noted[53]. In a phase I study of lenalidomide in individuals with MM, multiple doses did not alter the pharmacokinetic profile, with a time of maximum concentration (Tmax) of 1 hour or 1.5 hours on day 1 and day 28 of each dose level (5, 10, 25, 50 mg/day)[57]. Initially patented by Muller et. al for its ability to inhibit TNF-α [58], lenalidomide has entered clinical trials in a variety of hematologic and solid tumors.

Multiple Myeloma

Phase I and II studies have found promising results with the use of lenalidomide in the treatment of MM, and indicated responses in patients who were refractory to other prior treatment modalities.(See Table 2) In a Phase I dose escalation study (doses of 5, 10, 25, and 50 mg/day) using lenalidomide in 27 refractory and heavily pretreated (median of 3 prior treatments with 60% of patients having undergone autologous stem cell transplant) patients, no dose-limiting toxicity was observed during the first 28 days and myelosuppression developed after day 28 in all 13 patients at a dose of 50 mg/day, subsequent dose reduction to 25 mg/day was well-tolerated and was considered the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) [57]. Adverse events included rash, fatigue and lightheadedness but noticeably absent significant neuropathy or somnolence was observed. Seventy-one percent of the 24 patients had at least 25% reduction in paraproteins and stable disease (less than 25% reduction in paraproteins) was observed in 8% of patients. A similar schedule of lenalidomide in another phase I study showed a ≥ 50% reduction in paraprotein in 30% (3 patients), with doses of 25 mg or above [59].

Table 2. Selected clinical trials using lenalidomide in relapsed Multiple Myeloma.

| Investigator | Phase | No. of patients | Response | Adverse events (Grade 3 or 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richardson et. al.[57] | I | 27 | 17 of 24 pts (71%) with at least 25% reduction in paraproteins; 11 of 24 pts (46%) response from Thal failures;2 of 24 pts (8%) with stable disease; ORR: 71% | 13 pts with neutropenia for 50mg/d dose |

| Richardson et. al.[60] | II | 70 | ORR=25%; Median OS in 30mg daily: 28 mos and 15mg BID : 27 mos; Median PFS 30mg daily: 7.7 mos and 15 mg BID: 3.9 mos (p=0.2) | Time to myelosuppresion shorter in 15mg BID: 1.8 mos vs 30mg daily: 5.5 mos (p=0.05); Neuropathy in 15mg BID:23% vs. 30mg daily:10% |

| Dimopoulos et. al.[61] | III | 351 | Median TTP Len/Dex: 13.3 mos vs Dex/placebo:5.1 mos( p < 0.000001);ORR for Len/Dex 58% vs. Dex/placebo 22%; p < 0.001). | Neutropenia 16.5% vs. 1.2% |

Legend: pts = patients; ORR= overall response rate; OS = Overall survival; mos=months; PFS= progression free survival; TTP = Time to progression; Len = Lenalidomide (CC-5013); Dex = Dexamethasone; BID = twice a day

These encouraging findings led to a Phase II trial that initially enrolled 70 patients with 35 patients randomized to each of two cohorts; cohort 1 was to receive 15mg twice a day dose and cohort 2 was to receive 30 mg daily dose of lenalidomide [60]. Patients were treated on days 1-21, and subsequent courses began on day 28. However, an interim analysis of cohort 1 showed increased myelosuppression, despite similar response rates, and the twice daily arm closed to accrual and an additional 30 patients were added to the 30mg daily arm to further define the efficacy of daily dosing. Among the 107 patients available for response, the overall response rate (including complete response, partial response and minor response) to lenalidomide was 25% (see Table 2), while stable disease was achieved in 42% of both cohorts combined. The median overall survival (OS) for the twice-daily and once-daily arm was comparable at 27 and 28 months, respectively, and the responses were durable (about 20 months). Noteworthy is the myelosuppressive effect which is comparable in both cohorts (69% vs 61% neutropenia for the twice-daily vs daily arm, respectively), but the time to achieve myelosuppression was shorter for the twice daily arm. The incidence of grade 3 neuropathy was 23% (8 of 35) in the twice-daily arm vs. 10% (7 of 67 patients) in the once-daily arm.

These promising results led to two large Phase III double-blind trials, one in North America (MM-009 trial), and the other in Europe (MM-010 trial), that compared lenalidomide plus dexamethasone versus dexamethasone plus placebo. In the MM-010 trial, 351 patients were treated with dexamethasone 40 mg daily on days 1–4, 9–12, and 17–20 every 28 days and were randomized to receive either lenalidomide 25 mg daily orally on days 1–21 every 28 days or placebo[61]. With a study duration of 18 months, the median time to progression (TTP) for patients treated with the combination of lenalidomide plus dexamethasone was 13.3 months compared to 5.1 months for patients treated with dexamethasone and placebo (p < 0.000001). The overall response rate (ORR) was greater in patients who received lenalidomide plus dexamethasone than in patients who were given dexamethasone alone (58% vs. 22%; p < 0.001). Lenalidomide with dexamethasone was tolerable, with similar frequencies of grade 3 or 4 infections between treatment groups, but greater frequency of grade 3 or 4 neutropenia adverse events reported in patients given combination therapy than in patients treated with dexamethasone alone (16.5% vs. 1.2%), and 8.5% incidence of thromboembolic events in the combined lenalidomide/dexamethasone arm versus 4.5% in the dexamethasone arm. These results were updated with almost similar findings of response rate of 59% in the combination arm versus 24% with dexamethasone alone[62]. The MM-009 also had a similar finding, with longer median TTP of 11.1 months for the combination arm versus 4.7 months for the dexamethasone arm [63]. These aforementioned studies were done in MM patients who had relapsed or were otherwise refractory to thalidomide or previous regimens, and studies looking at frontline treatment of MM using lenalidomide has also shown promising results, including a phase II trial which utilized a schedule of lenalidomide 25 mg daily on days 1 to 21 of a 28-day cycle, along with dexamethasone orally 40 mg daily on days 1 to 4, 9 to 12, and 17 to 20 of each cycle [64]. Overall objective response was 91% (31 of 34 patients), with 2 (6%) achieving complete response (CR) and 11 (32%) meeting criteria for both very good partial response (VGPR) and near complete response, defined as a decrease in serum monoclonal protein level by 50% or greater and a decrease in urine M protein level by at least 90% or to a level less than 200 mg/24 hours, confirmed by 2 consecutive determinations at least 4 weeks apart. This data has recently been updated and among the subset of patients (21 of the 34 patients) who went on to receive lenalidomide and dexamethasone as primary therapy, without undergoing stem cell transplant, the ORR was 67% [65].

In summary, lenalidomide has emerged from clinical testing for MM in the relapsed setting, to front-line chemotherapy for newly diagnosed MM as induction regimen, with response rates exceeding 90%. Lenalidomide is also being combined with other agents in MM, such as bortezomib [66]. Currently, a phase III trial comparing lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone versus lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone as first line therapy in newly diagnosed MM has accrued 445 patients, and final results of this Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial (E4A03), is being awaited [67].

Myelodysplasia

Similar to the preclinical data on the response seen in 5q- deletion cell lines, List et. al. showed that among 148 patients with low or intermediate-risk MDS characterized by del5q31 and treated with 10 mg/d for 21 days every month, 55% had a complete cytogenetic response, and 29% achieved a complete morphologic remission[68]. In addition, transfusion requirement decreased in 76% of patients while 67% became red-cell- transfusion-independent. The response to lenalidomide was rapid (median of 4.6 weeks), and sustained; and the median duration of transfusion independence had not been reached after a follow-up of 104 weeks [69]. This trial was pivotal in gaining lenalidomide FDA approval in the treatment of low and intermediate risk MDS characterized by del5q31 [70]. This work also resulted in the issue of a patent for the use of this agent in the treatment and management of myelodysplastic syndromes [71].

Prostate Cancer

The involvement of angiogenesis in prostate cancer has been demonstrated by increased microvessel density, which has been shown as a predictor of tumor stage [72, 73]. Encouraging early studies using thalidomide in prostate cancer led to several studies utilizing thalidomide alone or in combination with chemotherapy in androgen-independent prostate cancer (AIPC) [12, 74]. An open-label phase II randomized trial comparing low-dose (200 mg/day) and high-dose (up to 1200 mg/day) thalidomide was completed in 63 patients (50 patients in the low-dose arm, and 13 patients in the high-dose arm) and showed 28% reduction in the serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) of ≥ 50%. The low-dose arm showed sustainable response of >150 days in 4 patients with a >50% decrease in PSA [12]. In contrast, patients on the high-dose arm showed no PSA reduction but had adverse effects of sedation and fatigue that limited further dose escalation beyond 200mg/day in 30% of the patients.

The favorable results of this study led to another randomized phase II study that added docetaxel to thalidomide for the treatment of AIPC. As angiogenic activity is thought to be greatest when the tumor burden is low, the combination of cytotoxic chemotherapy (that functions to reduce tumor size) with a cytostatic agent that would stabilize disease, was hypothesized to be synergetic [75]. This study accrued 59 patients and was given weekly docetaxel with or without thalidomide, 200 mg at bedtime, in patients with chemotherapy-naive metastatic AIPC. Docetaxel, 30 mg/m2 intravenously, was administered every 7 days for 3 weeks, followed by a 1-week rest period [74]. 35% (6 of 17) of the patients receiving docetaxel alone and 53% (19 of 36) of those receiving docetaxel and thalidomide have had a PSA decline of at least 50%. Thrombotic events have been seen in the combination arm. Updated analysis of this trial showed an improvement in the 18-month survival in the combination arm vs. docetaxel alone arm (69.3% versus 47.2%, P < 0.05), with a median survival time of 25.9 months in the combination arm versus 14.7 months in the single agent arm [76, 77].

A recently concluded Phase III study of 159 Gonadotropic-releasing Hormone (GnRH) analogue naive patients at 7 centers with rising PSA following definitive local treatment for prostate cancer but no radiographic evidence of disease (D0) were enrolled on a double blinded randomized clinical trial of intermittent hormonal therapy (unpublished data). After 6 months of a GnRH analogue alone (leuprolide or goserelin), patients received either thalidomide 200 mg daily or placebo. When the PSA rose to 5 ng/dl or baseline (whichever was lower) patients who still had no radiographic evidence of disease commenced another 6 months of hormonal therapy then crossed over to the opposite oral treatment. Results of this trial will be upcoming.

To this end, lenalidomide was examined in patients with refractory solid tumors [78]. Forty-five patients were enrolled, 36 of which patients had prostate cancer. The objectives of the study were to determine the maximum-tolerated dose (MTD), characterize the side-effects, and characterize pharmacokinetics (PK) in patients with solid tumors. Dose levels used were 5 mg, 10mg, 15mg, 20mg, 25mg, 30mg, 35mg and 40mg. The dosing schedule was modified from daily to 21 out of 28 days dosing. Therapy had been well tolerated with mostly grade 1 or 2 side-effects and 2 patients with grade 4 neutropenias, 1 patient each with hemolysis and arrythmia. Furthermore, no differences observed between dose levels for either oral clearance values (p = 0.47) or the apparent volume of distribution (Vz) values (p = 0.23), and at a dose range of 35mg/day, CC-5013 exhibited linear PK [79].

2.2. ACTIMID (CC-4047)

CC-4047 is a costimulatory thalidomide analogue that can prime protective, long-lasting, tumor-specific, Th1-type responses in vivo [80].

A phase I study using CC-4047 studied 24 relapsed or refractory MM patients that were treated with a dose-escalating regimen of oral CC-4047[81]. CC-4047 treatment was associated with significantly increased serum interleukin (IL)-2 receptor and IL-12 levels, which is consistent with activation of T cells and monocytes and macrophages. Clinical activity was also noted in 67% of patients, with greater than 25% reduction in paraprotein noted, 13 patients (54%) experienced a greater than 50% reduction in paraprotein, and four (17%) of 24 patients entered complete remission. The treatment-related thrombosis incidence was 12.5%, similar to treatment with thalidomide alone in MM[82]. Similar to CC-5013, the dose-limiting toxicity was myelosuppression, with neutropenia occurring in 6 patients within 3 weeks of starting therapy. The maximum tolerated dose (MTD) was 2 mg/d. Based on the different activity profile of this agent, as compared to CC-5013, Phase II studies are currently being planned for treatment of myelofibrosis and sickle cell anemia [83].

2.3. ENMD-0995 (S-3-Amino-phthalimido-glutarimide, S-3APG)

ENMD-0995 is a small molecule analogue of thalidomide that is the S(-) enantiomer 3-amino thalidomide. Thalidomide is a racemic glutamic acid analogue, consisting of S(-) and R(+) enantiomers that interconvert under physiological conditions [5]. The S(-) form potently inhibits release of TNF-alpha from peripheral blood mononuclear blood cells[84], whereas the R(+) form seems to act as a sedative[85]. This 3-amino derivative of thalidomide was demonstrated to have improved angiogenesis inhibitor activity that in animal models has shown no evidence of the toxic side effects as reported for the thalidomide molecule. Patent applications were filed with claims directed to a method of treating undesired angiogenesis using 3-amino thalidomide and other compounds [86]. As such, the S(-) enantiomer ENMD-0995, has been tested preclinically to inhibit angiogenesis more potently than thalidomide in a murine corneal micropocket model [52]. ENMD-0995 has entered Phase I clinical trial with 6 patients that followed an initial dosing regimen of 20 mg/day, but was reduced to 10 mg every other day when excessive myelosuppression was seen in the first cohort [87]. Despite this myelosuppressive toxicity, all 6 patients had a decrease in M-spike seen with very good partial response (VGPR)(>90% decrease in M spike). ENMD-0995 has therefore shown anti-MM activity. In 2002, ENMD-0995 was granted Orphan Drug designation from the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of patients with MM. EntreMed, Inc., the manufacturer of ENMD-0995, announced the licensing of the company’s thalidomide analogue programs to Celgene Corporation in 2003.

3. CPS49 AND OTHER THALIDOMIDE ANALOGUES

Previous studies have demonstrated that thalidomide metabolites are responsible for its antiangiogenic functions. One of the products of cytochrome P450 2C19 isozyme biotransformation of thalidomide, 5’-OH-thaliomide, retains some antiangiogenic activity[88-90]. On the basis of the structure of these metabolites, several classes of thalidomide analogues were synthesized. The rat aortic ring assay was used to screen the analogues for their antiangiogenic activity [39]. Seven analogues from the N-substituted and tetrafluorinated classes significantly inhibited microvessel growth in this assay. Fig.(3). Antiangiogenic activity was subsequently confirmed by human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) proliferation and tube formation experiments. One N-substituted analogue, CPS11, and two tetrafluorinated analogues, CPS45 and CPS49, consistently exhibited the highest potency and efficacy in all three assays. The initial patent application for these compounds, as well as related analogues, was filed in 2002, and subsequently licensed to Celgene, Inc. [91]. Based on promising in vitro and ex vivo findings, the therapeutic potentials of these agents were subsequently evaluated in vivo. Severely combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice bearing subcutaneous human prostate cancer xenografts were treated with these analogues, at the determined MTD for daily dosing. Though CPS49 was the most potent, all three analogues significantly inhibited PC3 tumor growth. In addition, both CPS45 and CPS49 significantly reduced PDGF-AA levels in these tumors, while CPS49 also decreased the intratumoral microvessel density (MVD) [40].

Fig. (3) . The analogues CPS11, CPS45 and CPS49.

CPS11 and CPS49 were also evaluated for their anti-MM activity in vitro[41]. Compared to CPS11, CPS49 exhibited a wider activity spectrum and higher potency against MM cell lines. Importantly, pretreatment of bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) with CPS11 or CPS49 abrogated their ability to induce proliferation of MM cells, confirming their ability to target tumor cells in the bone marrow microenvironment. This effect was more prominent for CPS49, consistent with its down regulation of IL-6, VEGF and IGF secreted by BMSCs after binding to MM cells. Ongoing studies in animal models of MM will evaluate these analogues in vivo.

Recently, CPS45 and CPS49 were discovered to activate nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) transcriptional pathways while simultaneously repressing nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) via a rapid intracellular amplification of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [92]. The ROS generation is associated with a rapid increase in intracellular calcium, an equally rapid dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential, and the caspase-independent cell death. This cytotoxicity is highly selective for most lymphoid leukemia cell lines, compared to resting PBMCs. Considering that leukemia refractory to chemotherapy shows elevated ROS and has a higher susceptibility to cytotoxic compounds inducing ROS, CPS45 and CPS49 are ideal candidates for in vivo animal studies for leukemia and lymphoma, which are currently underway.

4. LIMITATIONS

Although much has been learned regarding the mechanisms of action of thalidomide and its analogues, the precise mechanisms and specific molecular targets of these agents remain to be identified. Improving toxicity while retaining the bioactivity observed with thalidomide is of paramount importance in the development of new thalidomide analogues. It has become clear that very simple modifications in chemical structure can significantly change the mechanism of action, and all thalidomide analogues cannot be considered to have activity profiles similar to that of the parent compound. For those analogues that do exhibit activity in certain models, such as the multiple assays to assess anti-angiogenic activity, the exact molecular target remains unclear. As such, despite their chemical structure, these compounds are best considered as new, novel drugs, rather than as true analogues of thalidomide.

5. CURRENT AND FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS

Thalidomide has re-surfaced in the field of oncology, despite its troubled history as a teratogen. The increasing realization of its potential clinical utility in different neoplasms make the study of thalidomide and its analogues very promising. The development of the IMiDs is an example of how active research efforts contribute to the synthesis of new thalidomide analogues that provide improved efficacy and/or reducing toxicity. While the IMiDs have shown encouraging results in both animal models and have successfully entered clinical trials, efforts are still underway to improve the toxicity profile as well as understanding further and identifying specific molecular targets that would also help delineate the neoplasms for which it may exhibit clinical potency. Understanding of the in vivo metabolism of thalidomide has led to the synthesis of novel thalidomide analogues, such as the N-substituted and tetrafluorinated classes of thalidomide analogues, many which have shown encouraging antiangiogenic activity in both ex vivo and in vitro assays. Several of these analogues have also shown significant anti-tumor activity in preclinical prostate cancer xenograft models. These preclinical data support the further development and evaluation of novel thalidomide analogues as antiangiogenic and anti-cancer therapeutic agents.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The promising results seen in clinical trials with the use of IMiDs lenalidomide and CC-4047 warrants continued clinical development of thalidomide analogues and increase research efforts in identification of potential targets in different neoplasms. Future generation of IMiDs, as well as substituted class of thalidomides, show encouraging antiangiogenic effects in preclinical testing and will be validated by further clinical investigations. Despite the success of these agents in certain types of neoplasms, the specific molecular mechanisms and targets are still incompletely understood. Understanding of the precise mechanisms of action will help in the rational design of better thalidomide analogues, optimizing clinical applications, and ultimately translating into beneficial activity in specific neoplasms.

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract N01-CO-12400. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.*

*E.R. Gardner

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

References

- 1.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: a possible control point in tumor growth. Ann Intern Med. 1975;82:96–100. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-82-1-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mellin GW, Katzenstein M. The saga of thalidomide. Neuropathy to embryopathy, with case reports of congenital anomalies. N Engl J Med. 1962;267:1184–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196212062672305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelsey FO. Thalidomide update: regulatory aspects. Teratology. 1988;38:221–6. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420380305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Amato RJ, Loughnan MS, Flynn E, Folkman J. Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:4082–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenyon BM, Browne F, D’Amato RJ. Effects of thalidomide and related metabolites in a mouse corneal model of neovascularization. Exp Eye Res. 1997;64:971–8. doi: 10.1006/exer.1997.0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Amato RJ. US5593990. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Amato RJ. US5629327. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sampaio EP, Kaplan G, Miranda A, et al. The influence of thalidomide on the clinical and immunologic manifestation of erythema nodosum leprosum. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:408–14. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.2.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klausner JD, Makonkawkeyoon S, Akarasewi P, et al. The effect of thalidomide on the pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and M. tuberculosis infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;11:247–57. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199603010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schuler U, Ehninger G. Thalidomide: rationale for renewed use in immunological disorders. Drug Saf. 1995;12:364–9. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199512060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogelsang GB, Farmer ER, Hess AD, et al. Thalidomide for the treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1055–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204163261604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figg WD, Dahut W, Duray P, et al. A randomized phase II trial of thalidomide, an angiogenesis inhibitor, in patients with androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1888–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahut WL, Gulley JL, Arlen PM, et al. Randomized phase II trial of docetaxel plus thalidomide in androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2532–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajkumar SV, Hayman S, Gertz MA, et al. Combination therapy with thalidomide plus dexamethasone for newly diagnosed myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4319–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Little RF, Wyvill KM, Pluda JM, et al. Activity of thalidomide in AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2593–602. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.13.2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisen T, Boshoff C, Mak I, et al. Continuous low dose Thalidomide: a phase II study in advanced melanoma, renal cell, ovarian and breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:812–7. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Press Release: Thalomid® sNDA Granted FDA Approval For Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. http://www.multiplemyeloma.org/in_the_news/6.03.023.html; Accessed on:March 21, 2007

- 18.Tseng S, Pak G, Washenik K, Pomeranz MK, Shupack JL. Rediscovering thalidomide: a review of its mechanism of action, side effects, and potential uses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:969–79. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dimopoulos MA, Eleutherakis-Papaiakovou V. Adverse effects of thalidomide administration in patients with neoplastic diseases. Am J Med. 2004;117:508–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molloy FM, Floeter MK, Syed NA, et al. Thalidomide neuropathy in patients treated for metastatic prostate cancer. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:1050–7. doi: 10.1002/mus.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett CL, Schumock GT, Desai AA, et al. Thalidomide-associated deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Am J Med. 2002;113:603–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horne MK, 3rd, Figg WD, Arlen P, et al. Increased frequency of venous thromboembolism with the combination of docetaxel and thalidomide in patients with metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23:315–8. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.3.315.32106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zangari M, Anaissie E, Barlogie B, et al. Increased risk of deep-vein thrombosis in patients with multiple myeloma receiving thalidomide and chemotherapy. Blood. 2001;98:1614–5. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunzler V. Thalidomide in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients. A review of safety considerations. Drug Saf. 1992;7:116–34. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199207020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niwayama S, Turk BE, Liu JO. Potent inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by tetrafluorothalidomide and tetrafluorophthalimides. J Med Chem. 1996;39:3044–5. doi: 10.1021/jm960284r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller GW, Chen R, Huang SY, et al. Amino-substituted thalidomide analogs: potent inhibitors of TNF-alpha production. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999;9:1625–30. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collin X, Robert J, Wielgosz G, et al. New anti-inflammatory N-pyridinyl(alkyl)phthalimides acting as tumour necrosis factor-alpha production inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2001;36:639–49. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(01)01254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan G, Sampaio EG. US5385901. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller G, Stirling DI, Chen RS. US6281230. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller G, Stirling DI, Chen RS. US6335349. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller G, Stirling DI, Chen RS. US6395754. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Muller G, Stirling DI, Chen RS. US6316471. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corral LG, Haslett PA, Muller GW, et al. Differential cytokine modulation and T cell activation by two distinct classes of thalidomide analogues that are potent inhibitors of TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 1999;163:380–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corral LG, Kaplan G. Immunomodulation by thalidomide and thalidomide analogues. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999 ;58(Suppl 1):I107–13. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.2008.i107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartlett JB, Dredge K, Dalgleish AG. The evolution of thalidomide and its IMiD derivatives as anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:314–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Musto P. Thalidomide therapy for myelodysplastic syndromes: current status and future perspectives. Leuk Res. 2004;28:325–32. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verghese MW, McConnell RT, Lenhard JM, Hamacher L, Jin SL. Regulation of distinct cyclic AMP-specific phosphodiesterase (phosphodiesterase type 4) isozymes in human monocytic cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:1164–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marriott JB, Clarke IA, Czajka A, et al. A novel subclass of thalidomide analogue with anti-solid tumor activity in which caspase-dependent apoptosis is associated with altered expression of bcl-2 family proteins. Cancer Res. 2003;63:593–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ng SS, Gutschow M, Weiss M, et al. Antiangiogenic activity of N-substituted and tetrafluorinated thalidomide analogues. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ng SS, MacPherson GR, Gutschow M, Eger K, Figg WD. Antitumor effects of thalidomide analogs in human prostate cancer xenografts implanted in immunodeficient mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4192–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar S, Raje N, Hideshima T, et al. Antimyeloma activity of two novel N-substituted and tetraflourinated thalidomide analogs. Leukemia. 2005;19:1253–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corral LG, Muller GW, Moreira AL, et al. Selection of novel analogs of thalidomide with enhanced tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitory activity. Mol Med. 1996;2:506–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Poulaki V, et al. Biologic sequelae of nuclear factor-kappaB blockade in multiple myeloma: therapeutic applications. Blood. 2002;99:4079–86. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson KC, Jones RM, Morimoto C, Leavitt P, Barut BA. Response patterns of purified myeloma cells to hematopoietic growth factors. Blood. 1989;73:1915–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Shima Y, et al. Thalidomide and its analogs overcome drug resistance of human multiple myeloma cells to conventional therapy. Blood. 2000;96:2943–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Poulaki V, et al. Apoptotic signaling induced by immunomodulatory thalidomide analogs in human multiple myeloma cells: therapeutic implications. Blood. 2002;99:4525–30. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gandhi AK, Kang J, Naziruddin S, Parton A, Schafer PH, Stirling DI. Lenalidomide inhibits proliferation of Namalwa CSN.70 cells and interferes with Gab1 phosphorylation and adaptor protein complex assembly. Leuk Res. 2006;30:849–58. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davies FE, Raje N, Hideshima T, et al. Thalidomide and immunomodulatory derivatives augment natural killer cell cytotoxicity in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2001;98:210–6. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.1.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marriott JB, Clarke IA, Dredge K, Muller G, Stirling D, Dalgleish AG. Thalidomide and its analogues have distinct and opposing effects on TNF-alpha and TNFR2 during co-stimulation of both CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;130:75–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01954.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.List AF. Emerging data on IMiDs in the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) Semin Oncol. 2005;32:S31–5. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dredge K, Marriott JB, Macdonald CD, et al. Novel thalidomide analogues display anti-angiogenic activity independently of immunomodulatory effects. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:1166–72. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lentzsch S, Rogers MS, LeBlanc R, et al. S-3-Amino-phthalimido-glutarimide inhibits angiogenesis and growth of B-cell neoplasias in mice. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2300–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knight R. IMiDs: a novel class of immunomodulators. Semin Oncol. 2005;32:S24–30. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gupta D, Treon SP, Shima Y, et al. Adherence of multiple myeloma cells to bone marrow stromal cells upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor secretion: therapeutic applications. Leukemia. 2001;15:1950–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tohnya TM, Hwang K, Lepper ER, et al. Determination of CC-5013, an analogue of thalidomide, in human plasma by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2004;811:135–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raje N, Anderson KC. Thalidomide and immunomodulatory drugs as cancer therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2002;14:635–40. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Richardson PG, Schlossman RL, Weller E, et al. Immunomodulatory drug CC-5013 overcomes drug resistance and is well tolerated in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2002;100:3063–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muller G, Stirling DI, Chen RS. US5635517. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zangari M, Tricot G, Zeldis J, Eddlemon P, Saghafifar F, Barlogie B. Results of phase I study of CC-5013 for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM) patients who relapse after high dose chemotherapy (HDCT) [abstract] Blood. 2001;98:775a. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richardson PG, Blood E, Mitsiades CS, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of lenalidomide therapy for patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108:3458–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dimopoulos MA, Spencer A, Attal M, et al. Study of Lenalidomide Plus Dexamethasone Versus Dexamethasone Alone in Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma (MM): Results of a Phase 3 Study (MM-010) ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2005;106:6. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dimopoulos MA, Anagnotopoulos A, Prince M, et al. Lenalinomide (Revlimid) combination with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma and independent of the number of previous treatment. Haematologica. 2006;91(Suppl 1 ):181. Abstract 494. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weber DM, Chen C, Niesvizky R, et al. Lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone provides improved overall survival compared to high-dose dexamethasone alone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (MM): Results of a North American phase III study (MM-009) J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2006;24:7521. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rajkumar SV, Hayman SR, Lacy MQ, et al. Combination therapy with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone (Rev/Dex) for newly diagnosed myeloma. Blood. 2005;106:4050–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lacy M, Gertz M, Dispenzieri A, et al. Lenalidomide Plus Dexamethasone (Rev/Dex) in Newly Diagnosed Myeloma: Response to Therapy, Time to Progression, and Survival. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2006;108:798. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Richardson P, Schlossman R, Munshi N, et al. A Phase 1 Trial of Lenalidomide (REVLIMID(R)) with Bortezomib (VELCADE(R)) in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2005;106:365. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rajkumar SV, Jacobus S, Callander N, Fonseca R, Vesole D, Greipp P. A Randomized Phase III Trial of Lenalidomide Plus High-Dose Dexamethasone Versus Lenalidomide Plus Low-Dose Dexamethasone in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma (E4A03): A Trial Coordinated by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2006;108:799. [Google Scholar]

- 68.List A, Dewald G, Bennett CL, et al. Hematologic and cytogenetic (CTG) response to lenalidomide (CC-5013) in patients with transfusion-dependent (TD) myelodysplatic syndrome (MDS) and chromosome 5q31.1 deletion: Results of the multicenter MDS-003 Study. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2s. Abstract 5. [Google Scholar]

- 69.List A, Dewald G, Bennett J, et al. Lenalidomide in the myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1456–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.FDA Approval for Lenalidomide.2005;In: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/druginfo/fda-lenalidomide; Accessed on:March 21, 2007

- 71.Zeldis JB. US7189740. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weidner N, Carroll PR, Flax J, Blumenfeld W, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis correlates with metastasis in invasive prostate carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:401–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wakui S, Furusato M, Itoh T, et al. Tumour angiogenesis in prostatic carcinoma with and without bone marrow metastasis: a morphometric study. J Pathol. 1992;168:257–62. doi: 10.1002/path.1711680303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Figg WD, Arlen P, Gulley J, et al. A randomized phase II trial of docetaxel (taxotere) plus thalidomide in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:62–6. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Macpherson GR, Franks M, Tomoaia-Cotisel A, Ando Y, Price DK, Figg WD. Current status of thalidomide and its role in the treatment of metastatic prostate cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;46 (Suppl):S49–57. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(03)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Retter AS, Ando Y, Price DK, et al. Follow-up analysis of a randomized phase II study of docetaxel and thalidomide in androgen-independent prostate cancer: Updated survival data and stratification by CYP2C19 mutation status. Proceedings of the Prostate Cancer Symposium. 2005 Abstract 265. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Figg WD, Retter AS, Steinberg SM, Dahut W. In Reply: Inhibition of Angiogenesis: Thalidomide or Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin? J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2113–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tohnya TM, Ng SS, Dahut WL, et al. A phase I study of oral CC-5013 (lenalidomide, Revlimid), a thalidomide derivative, in patients with refractory metastatic cancer. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2004;2:241–3. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2004.n.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tohnya TM, Gulley J, Arlen PM, et al. Phase I study of lenalidomide, a novel thalidomide analog, in patients with refractory metastatic cancer. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2006;24:13038. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dredge K, Marriott JB, Todryk SM, et al. Protective antitumor immunity induced by a costimulatory thalidomide analog in conjunction with whole tumor cell vaccination is mediated by increased Th1-type immunity. J Immunol. 2002;168:4914–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schey SA, Fields P, Bartlett JB, et al. Phase I study of an immunomodulatory thalidomide analog, CC-4047, in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3269–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Urbauer E, Kaufmann H, Nosslinger T, Raderer M, Drach J. Thromboembolic events during treatment with thalidomide. Blood. 2002;99:4247–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Research IMiDs. http://www.celgene.com/Research.aspx?S=5; Accessed on:April 2, 2007

- 84.Wnendt S, Finkam M, Winter W, Ossig J, Raabe G, Zwingenberger K. Enantioselective inhibition of TNF-alpha release by thalidomide and thalidomide-analogues. Chirality. 1996;8:390–6. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-636X(1996)8:5<390::AID-CHIR6>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Frederickson RC, Slater IH, Dusenberry WE, Hewes CR, Jones GT, Moore RA. A comparison of thalidomide and pentobarbital - new methods for identifying novel hypnotic drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1977;203:240–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.D’Amato RJ. US5712291. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lacy M, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, et al. ENMD-0995 (S 3-APG), a Novel Thalidomide Analogue, Has Promising Clinical Activity for Patients with Relapsed Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Preliminary Results of a Phase I Clinical Trial. Blood. 102 Abstract #1654. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ando Y, Fuse E, Figg WD. Thalidomide metabolism by the CYP2C subfamily. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1964–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ando Y, Price DK, Dahut WL, Cox MC, Reed E, Figg WD. Pharmacogenetic associations of CYP2C19 genotype with in vivo metabolisms and pharmacological effects of thalidomide. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:669–73. doi: 10.4161/cbt.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Price DK, Ando Y, Kruger EA, Weiss M, Figg WD. 5’-OH-thalidomide, a metabolite of thalidomide, inhibits angiogenesis. Ther Drug Monit. 2002;24:104–10. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200202000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Figg WD, Eger K, Teubert U, Weiss M, Guetschow M, Hecker T, Hauschildt S. US20040077685. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ge Y, Montano I, Rustici G, et al. Selective leukemic-cell killing by a novel functional class of thalidomide analogs. Blood. 2006;108:4126–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]