Abstract

Recent reports have described a stem cell population termed stromal vascular cells (SVCs) derived from the stromal vascular fraction of adipose tissue, which are capable of intrinsic differentiation into spontaneously beating cardiomyocytes in vitro. The objective of this study was to further define the cardiac lineage differentiation potential of SVCs in vitro and to derive methods for enriching SVC-derived beating cardiac myocytes. SVCs were isolated from the stromal vascular fraction of murine adipose tissue. Cells were cultured in methylcellulose-based murine stem cell media. Analysis of SVC-derived beating myocytes included Western blot, and calcium imaging. Enrichment of acutely isolated SVCs was carried out using antibody tagged magnetic nanoparticles, and pharmacologic manipulation of Wnt and cytokine signaling. Under initial media conditions, spontaneously beating SVCs expressed both cardiac developmental and adult protein isoforms. Functionally, this specialized population can spontaneously contract and pace under field stimulation, and shows the presence of coordinated calcium transients. Importantly, this study provides evidence for two independent mechanisms of enriching the cardiac differentiation of SVCs. First, this study shows that differentiation of SVCs into cardiac myocytes is augmented by non-canonical Wnt agonists, canonical Wnt antagonists, and cytokines. Second, SVCs capable of cardiac lineage differentiation can be enriched by selection for stem cell-specific membrane markers Sca1 and c-kit. Adipose-derived SVCs are a unique population of stem cells that show evidence of cardiac lineage development making them a potential source for stem cell-based cardiac regeneration studies.

Keywords: Stromal Vascular Cells, Adipose Tissue, Stem Cells, Wnt signaling, Troponin I, Calcium Transients, Cytokines

Introduction

Numerous reports have studied the potential for various somatic stem cell populations to differentiate along the myogenic lineage (Cannon, 2004;Choi et al., 2004;Eisenberg et al., 2003;Fraser et al., 2004;Heng et al., 2004;Leri et al., 2005). Recent studies have identified stem cells within adipose tissue capable of differentiating along multiple pathways (Nakagami et al., 2006;Moseley et al., 2006;Parker and Katz, 2006). Compared to other stem cell populations, such as hematopoeitic stem cells, the field of adipose derived stem cells is in its infancy, although progress is being made to understand the plasticity and proper isolation methods for stem cells derived from this tissue (Bai et al., 2007;Fraser et al., 2006b;Fraser et al., 2006a;Nakagami et al., 2006).

One unique cell population, termed stromal vascular cells (SVCs), is derived from the stromal vascular fraction of adipose tissue (Planat-Benard et al., 2004a). These cells have been found to differentiate spontaneously into beating striated myocytes. Initial characterization of these myocytes was consistent with cardiac differentiation based on the detection of cardiac markers including Nkx2.5, MLC2a/2v, β-MHC, ANP, MEF2c, Cn43. Although some of these markers are necessary components of the cardiac developmental program (e.g. Nkx2.5, MLC2v (Moss and Fitzsimons, 2006)) others have more diverse involvement in cardiac/slow skeletal muscle myofibrilogenesis (e.g. β-MHC (Meissner et al., 2007)). More importantly, none of the markers used to describe differentiated SVCs to date are unequivocal adult cardiac isoforms which raises the question as to whether SVCs can differentiate into the adult cardiac phenotype. In addition to these markers of cardiac development, Planat-Benard et al. showed that differentiated SVCs have evidence of distinct sarcomeres and electrophysiologically show appropriate chronotropic responsiveness to adrenergic and cholinergic agents. Importantly, this population of cells shows spontaneous differentiation along the myogenic line ge without ectopic induction agents such as 5-azacytidine (Choi et al., 2004). Additional reports have shown that SVCs are able to regenerate skeletal muscle in a mouse hind limb ischemia model (Planat-Benard et al., 2004b). Although the present understanding of SVCs is incomplete, their potential versatility in cell based therapeutics is intriguing.

Several fundamental questions regarding SVC-derived beating myocytes remain to be fully addressed. Concerning their cardiac lineage determination, it is unknown whether these cells express protein isoforms found in the adult heart. Although there are few markers that are unique to the adult heart, troponin I is an ideal protein that provides isoform-specific transitions during unique stages of development showing unambiguous evidence for the cardiac lineage phenotype. This study follows the expression profile of troponin I to elucidate the cardiac developmental potential of differentiating SVCs in vitro. In addition to addressing lineage development, potential applications in cell based therapies necessitate the study of functional characteristics such as the regulation and kinetics of calcium handling in differentiated SVCs compared to adult mouse cardiac myocytes. Identifying mechanisms of augmenting the differentiation potential of SVCs will also contribute beneficially to our general understanding of pathways involved in stem cell differentiation along the cardiac lineage. Lastly, identifying markers for enrichment of this stem cell population will enable purification of SVCs, a procedure commonly used in cell based therapeutics.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The procedures used in this study are in agreement with the guidelines of the Internal Review Board of the University of Michigan and approved by the University of Michigan Committee on the Use and Care of Animals. Veterinary care was provided by the University of Michigan Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine. The University of Michigan is accredited by the American Association of Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Health Care, and the animal care use program conforms to the standards of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Pub. No. 86-23).

SVC Isolation and primary culture conditions

Cells from the stromal vascular fraction of adipose tissue were isolated according to Planat Benard et al (Planat-Benard et al., 2004a) with slight modifications. Briefly, interscapular adipose tissue from female C57BL6 mice was digested at 37°C in PBS containing 2% BSA and 2 mg/mL collagenase for 45 minutes (collagenase A, Roche). After filtration through 70 μm filter and centrifugation, isolated SVF cells were suspended in PBS, counted with a hemocytometer, and plated at 10×103 cells/mL in 1.5 mL of MethoCult GF M3534 (StemCell Technologies). The culture conditions referred to as minimum medium contain basic 1% methylcellulose in Iscove’s MDM with 1% bovine serum albumin, 15% fetal bovine serum, 2-mercaptoethanol (10−4 mol/L), L-glutamine (2 mmol/L), recombinant human insulin (10 μg/mL), and human transferrin (200 μg/mL) (StemCell Technologies, MethoCult GF M3234). The complete methylcellulose medium mostly used in these experiments (StemCell Technologies, MethoCult GF M3534) consisted of the same medium enriched with recombinant murine IL-3 (10 ng/mL), recombinant human IL-6 (10 ng/mL), and recombinant mouse SCF (50 ng/mL). SVF cells plated in methylcellulose media were observed every 2 days under an inverted phase-contrast microscope and number as well as morphology of developing clones was followed.

Mouse myocyte isolation and culture conditions

Isolation and culturing of adult murine cardiac myocytes was performed as previously described (Day et al., 2006).

Western Blot

Each sample was isolated by removing methylcellulose media and, out of a heterogeneous cell population, isolating only spontaneously beating colonies by micropipette. Samples were then placed in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The following primary antibodies were used for Western blotting: 5c5 (Sigma; 1:5,000) for α-sarcomeric actin, 1F2 (RDI; 1:1000) for cardiac specific Troponin T, MAB 1691 (Chemicon; 1:1000) for Troponin I, MAB 1627 (Chemicon; 1:1000) for cardiac specific Troponin I, T-2780 (Sigma, clone TM311; 1:100,000) for tropomyosin. For detection of α-sarcomeric actin, cardiac Troponin T, and Troponin I a fluorescently labeled goat anti-mouse (Rockland, IRDye 680 or 800 conjugated affinity purified goat anti-mouse IgG; 1:1000) was used as a secondary antibody. In these cases, Western blot analysis was accomplished using the infrared imaging system, Odyssey (Li-Cor, Inc.) and images analyzed using Odyssey software v. 1.2. For detection of tropomyosin goat anti-mouse conjugated to horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody (Sigma; 1:1,000) was used with detection by enhanced chemiluminescence.

Cell Shortening and Calcium Transient Measurements

Functional measurements of calcium transients and contractility in adult mouse myocytes was performed as previously described (Day et al., 2006). In a similar fashion, SVCs were cultured on coverslips for two weeks in complete methylcellulose media (GF M3534). To measure cell shortening and calcium transients in differentiated SVCs, methylcellulose media was replaced with M199+ solution. For detection of calcium transients, differentiated SVCs were loaded for 10 minutes with the fluorescence indicator FURA 2AM (Molecular Probes). The heterogeneity of spontaneously beating colonies, which had regions of hyperkinetic activity and other regions with hypokinetic activity, was often normalized by the buffering activity of FURA-2AM. Consequently, only colonies quiescent after FURA-2AM loading were used for calcium transient measurements. All experiments were performed at 37 ± 1°C. Coverslips were mounted on a custom microscope stage. Cell shortening and Ca2+ transients were measured simultaneously using the fluorescence and contractility system from Ionoptix (Milton, MA). Analysis of contractility and calcium transients was acquired from spontaneously beating colonies of differentiated SVCs or by field stimulation of differentiated SVCs at 80 Voltz and 0.5 Hz. Pharmacologic manipulation involved acute addition of 2mM muscarine chloride (Sigma; M6532) in M199+ to colonies of spontaneously beating SVCs. All data were analyzed using the Ionoptix software.

Wnt treatment

Wnt treatment of cultured stromal vascular cells involved the use of complete methylcellulose media (Stem Cell Technologies, GF M3534) with the addition of recombinant mouse Wnt 5a (final concentrations: 10 ng/mL, 20 ng/mL, 40 ng/mL and 80 ng/mL) or recombinant mouse Dickkopf 1 (Dkk1, final concentrations: 40 ng/mL and 80 ng/mL), or recombinant mouse Wnt 3a (final concentration: 80 ng/mL), or lastly, co-treatment using recombinant mouse Wnt5a and recombinant mouse Dkk1 (final concentration for each: 50ng/mL). All recombinant proteins were acquired from R&D Systems. Final analysis of cultures was performed after two weeks of in vitro differentiation.

Cell Selection

After isolation of SVCs from adipose tissue, further purification of Sca1+ cells or c-kit+ cells from this heterogeneous cell population was performed using EasySep Mouse Sca1 Positive Selection Kit (StemCell Technologies, Cat# 18756) or EasySep Mouse CD117 Positive Selection Kit (StemCell Technologies, Cat# 18757), respectively. Three rounds of separation were performed to increase purification of selected cells for in vitro differentiation. Post-selection analysis of non-selected control cells and selected cells was performed by flow cytometry (Beckman-Coulter Epics XL). The positive fraction of selected cells, negative fraction of selected cells, and non-selected control cells were cultured in complete methylcellulose media (StemCell Technologies, GF M3534). Final analysis of differentiated SVCs was performed after two weeks of in vitro differentiation.

Statistics

All data are expressed as means ± s.e.m. All multivariable assays were analyzed by student’s t-test or one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Newman-Keuls post-hoc test.

Results

SVCs undergo intrinsic differentiation along the cardiac lineage

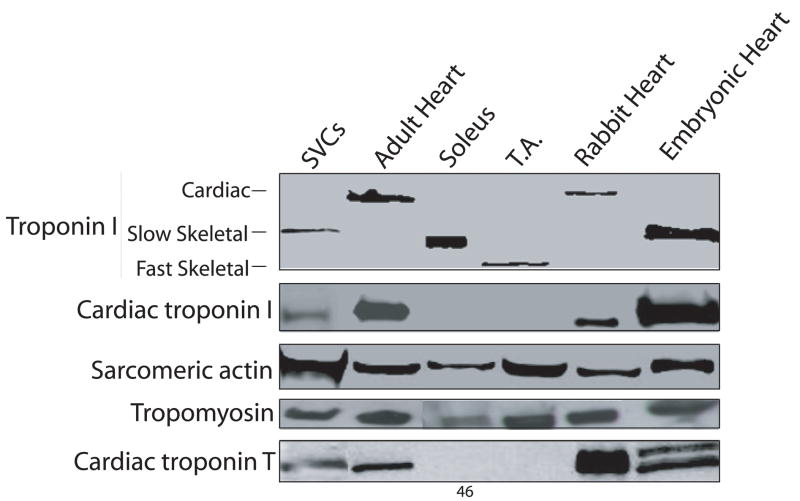

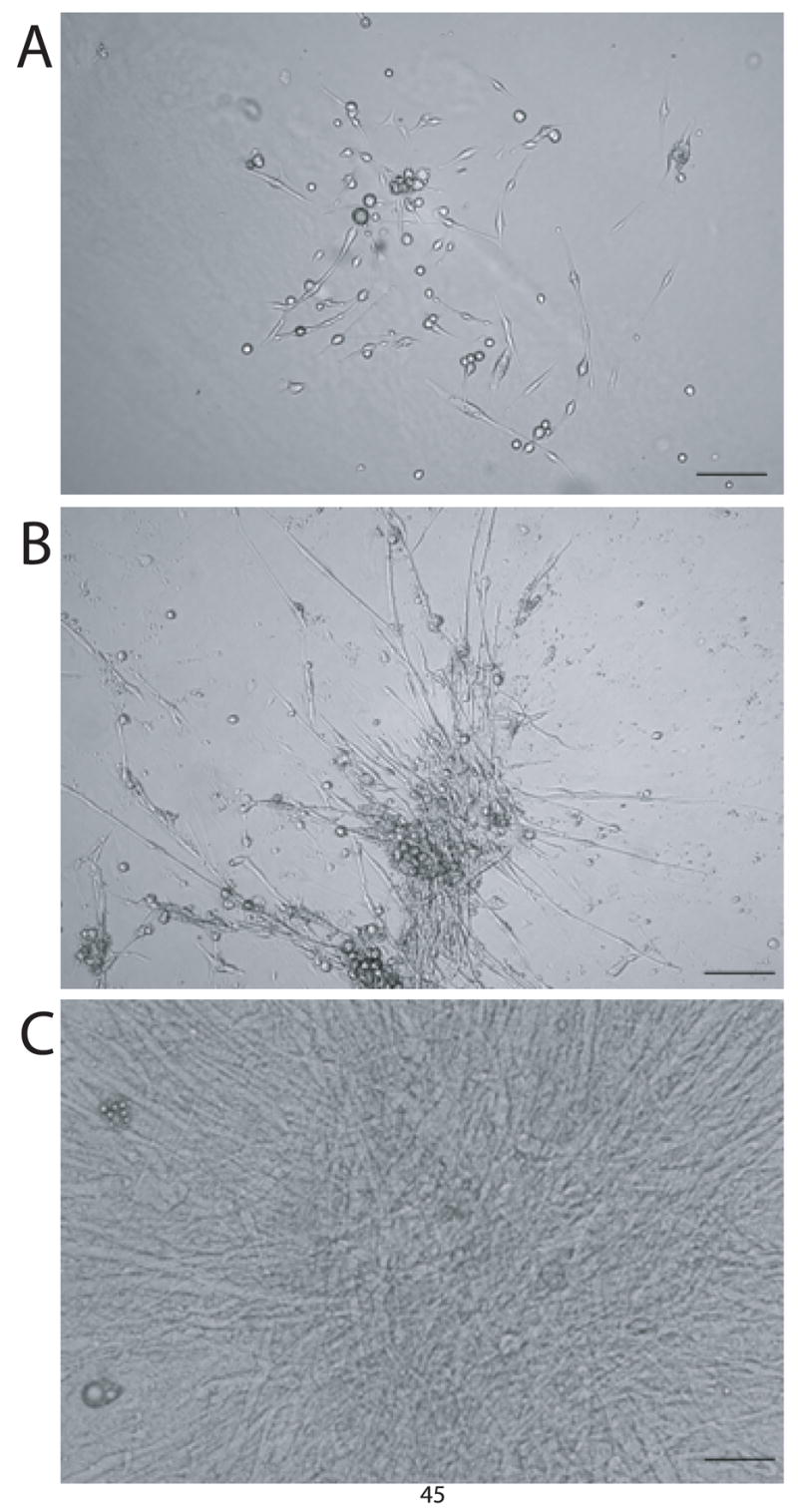

The stromal vascular fraction of brown adipose tissue was isolated and cultured in complete media. Over the course of two weeks, small circular SVCs differentiated into elongated cells (Figure 1A–C) with the subsequent initiation of spontaneously beating (Supplementary video online). Spontaneous beating occurred as early as 7 days with the emergence of SVC-derived beating colonies increasing over time (data not shown). Analysis of protein isoform expression in micro-dissected colonies of spontaneously beating SVC-derived cardiac myocytes after fourteen days of in vitro differentiation showed the presence of both developmental and adult cardiac-specific isoforms of thin filament proteins (Figure 2). Specifically, SVC-derived beating myocytes expressed slow skeletal troponin I (ssTnI), the fetal/neonatal isoform of TnI in the heart. Additionally, differentiated SVCs were able to develop further to express adult cardiac markers including cardiac troponin I (cTnI). Although the slow skeletal isoform of TnI was repeatedly detectible in microdissected colonies of SVC-derived beating myocytes by Western blot using a pan-TnI antibody (MAB 1691), the presence of the adult cardiac isoform was never observed by this method. However, the developmental switch to the adult phenotype could be detected by Western blot when using an antibody with high fidelity for the cardiac-specific isoform of TnI (MAB 1627). In terms of a ratiometric comparison, this suggests that SVC-derived beating myocytes predominantly existed in the early cardiac developmental stage whereas an unquantifiable subset of differentiated SVCs was able to transition to the adult phenotype. In addition to troponin I, thin filament proteins observed included cardiac troponin T, α-sarcomeric actin and tropomyosin (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Microscopic analysis of SVC-derived cardiac myocytes during in vitro differentiation.

Adipose tissue derived SVCs were plated in methylcellulose media (GF M3534) and observed during the course of in vitro differentiation. Images were acquired at 10x magnification under a phase contrast microscope showing colonies which have differentiated to day 5 (A), day 10 (B), and day 15 (C). Spontaneous beating was observed as early as day 7 when colonies grew into an intercalated syncitium. Bar = 75 μm.

Figure 2. Western blot of sarcomeric proteins in SVCs isolated after 14 days of in vitro differentiation.

Acutely isolated adipose derived SVCs were cultured in methylcellulose media (GF M3534) and allowed to differentiate for two weeks. Western blot was performed after microdissection of spontaneously beating colonies. Western blot controls include adult mouse heart, soleus (slow skeletal muscle), tibialis anterior (TA; fast skeletal muscle), adult rabbit heart, and embryonic mouse heart. By western blot, SVC-derived cardiac myocytes express slow skeletal troponin I, cardiac troponin I, α-sarcomeric actin, tropomyosin, and cardiac troponin T.

SVC-derived cardiac myocytes have fast kinetics of calcium regulation compared to adult mouse myocytes

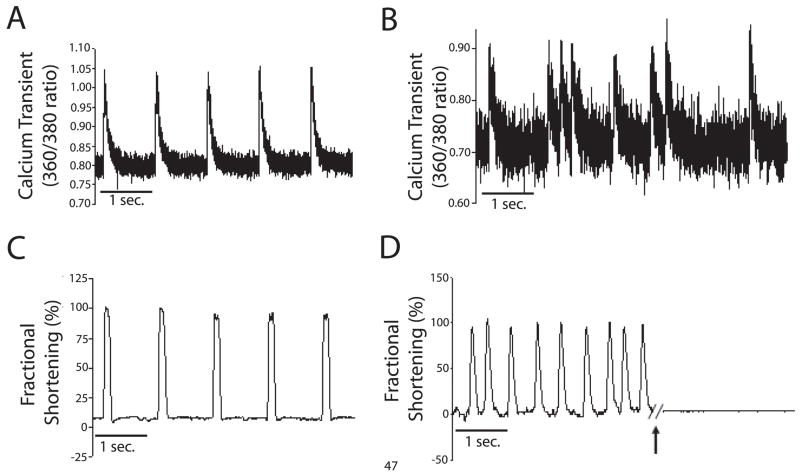

Calcium imaging using the fluorophore FURA 2AM and edge detection were used to characterize the functional phenotype of differentiated, beating SVC-derived cardiac myocytes. This specialized population spontaneously contract as well as pace under field stimulation indicated functionally by the presence of precise calcium transients (Figure 3A,B) and cellular contractility (Figure 3C,D) similar to isolated cardiac myocytes. Spontaneously beating SVC-derived myocytes had an intrinsic pacing frequency around two hertz (data not shown). Supporting findings by Planat Benard et al (Planat-Benard et al., 2004a), the spontaneous beating of differentiated SVCs was ablated by acute addition of 2 mM muscarine chloride, suggesting that these cells contain an intrinsic pacemaker phenotype (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Raw data showing calcium transients and contractility in SVC-derived cardiac myocytes.

After two weeks of in vitro differentiation, beating colonies of differentiated SVCs were loaded with the calcium indicator FURA 2AM in M199+. Using the Ionoptix imaging system colonies were analyzed for calcium transients during field stimulation at 80V and a rate of 0.5 Hz (A) or derived during spontaneous beating (B). Simultaneously, contractility was measured by edge detection during field stimulation (C). During analysis by edge detection, spontaneously beating SVC-derived cardiac myocytes were pharmacologically manipulated by acute addition of 2 mM muscarine chloride (arrow) (D).

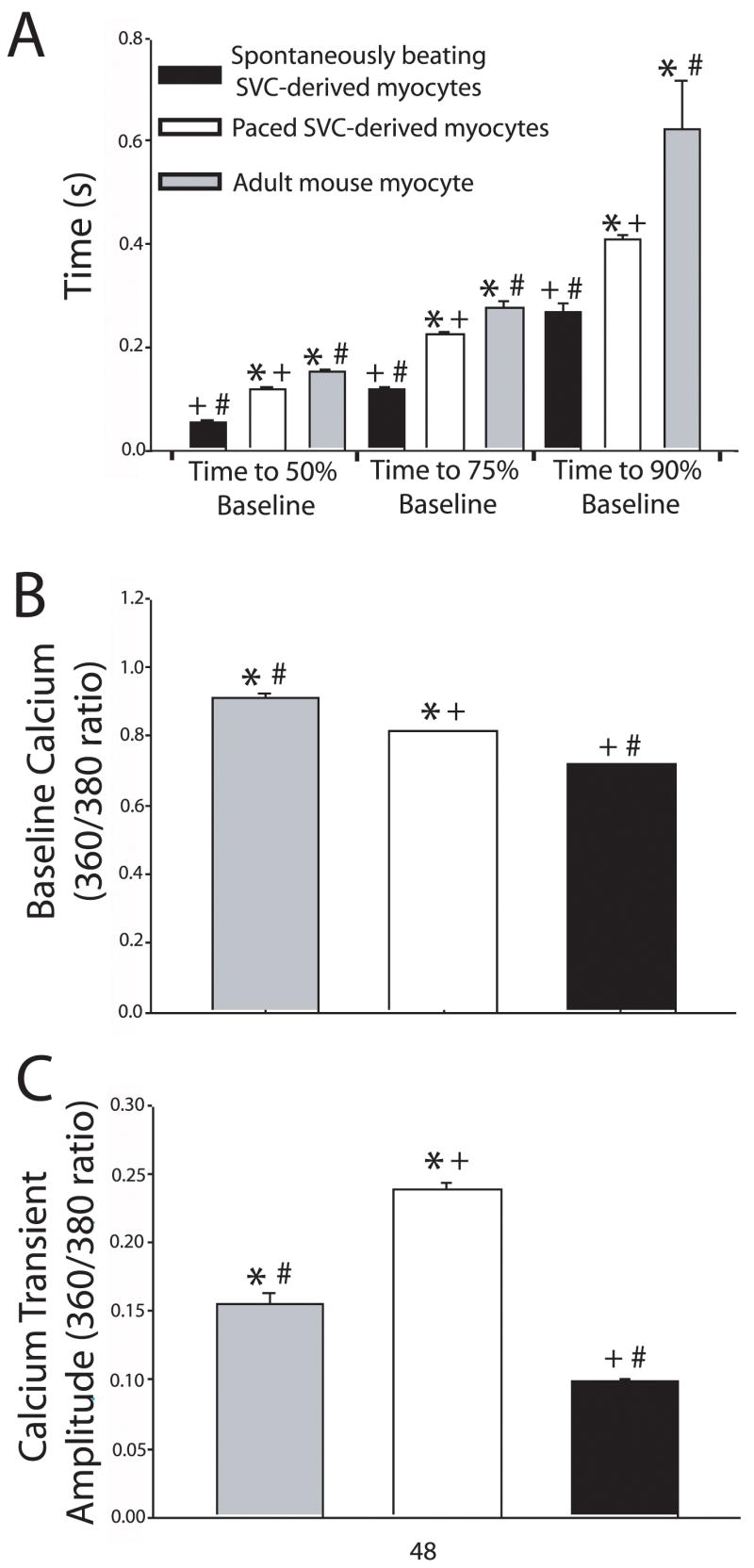

Interestingly, SVC-derived cardiac myocytes have different calcium handling kinetics when compared to adult mouse myocytes. All parameters measured showed a significant difference between paced vs. spontaneously beating SVC-derived myocytes as well as paced or spontaneously beating SVC-derived myocytes independently compared to adult cardiac myocytes. In terms of the rate of calcium re-sequestration at all phases of diastole (time of 50%, 75%, and 90% return to baseline) spontaneously beating SVC-derived myocytes were fastest followed by paced SVC-derived mycoytes with the slowest rate of calcium re-uptake observed in adult cardiac myocytes (50%: 0.055 ± 0.001 sec. vs. 0.120 ± 0.001 sec. vs. 0.153 ± 0.003 sec.; 75%: 0.120 ± 0.004 sec. vs. 0.225 ± 0.003 sec. vs. 0.278 ± 0.009 sec.; 90%: 0.267 ± 0.018 sec. vs. 0.409 ± 0.01 sec. vs. 0.625 ± 0.091 sec., respectively; P < 0.001). It was also observed that adult mouse cardiac myocytes have the highest level of baseline diastolic calcium followed by paced SVC-derived myocytes with the lowest diastolic calcium levels observed with spontaneously beating SVC-derived myocytes (0.91 ± 0.01 vs. 0.81 ± 0.002 vs. 0.72 ± 0.001, respectively; P < 0.001) (Figure 4B). Finally, we measured the calcium transient amplitude and found that paced SVC-derived myocytes had the largest amplitude of calcium release followed by adult cardiac myocytes with the smallest amplitude observed with spontaneously beating SVC derived myocytes (0.24 ± 0.004 vs. 0.15 ± 0.009 vs. 0.1 ± 0.001, respectively; P < 0.001) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Kinetics of calcium regulation in SVC-derived cardiac myocytes paced and spontaneously beating compared to murine cardiac myocytes.

These data show that paced SVC-derived myocytes, spontaneously beating SVC-derived myocytes, and adult mouse myocytes have significantly different calcium transient kinetics including rate of calcium sequestration at time points of 50%, 75%, and 90% return to baseline normalized to time of calcium transient peak (A), baseline calcium (B), and calcium transient amplitude (C). Spontaneously beating SVC-derived myocytes (black bars), n=44; paced SVC-derived myocytes (white bars), n= 150; Mouse cardiac myocytes (gray bars), n=39. * = P<0.001 paced SVCs vs. mouse myocytes; # = P<0.001 spontaneously beating SVCs vs. mouse myocytes; + = P<0.001 spontaneously beating SVCs vs. paced SVCs. All values are mean ± s.e.m. Data were analyzed by one way ANOVA with Newman Keul’s post-hoc test.

Recombinant Wnt proteins and cytokines augmentt the differentiation potential of SVCs into beating cardiac myocytes

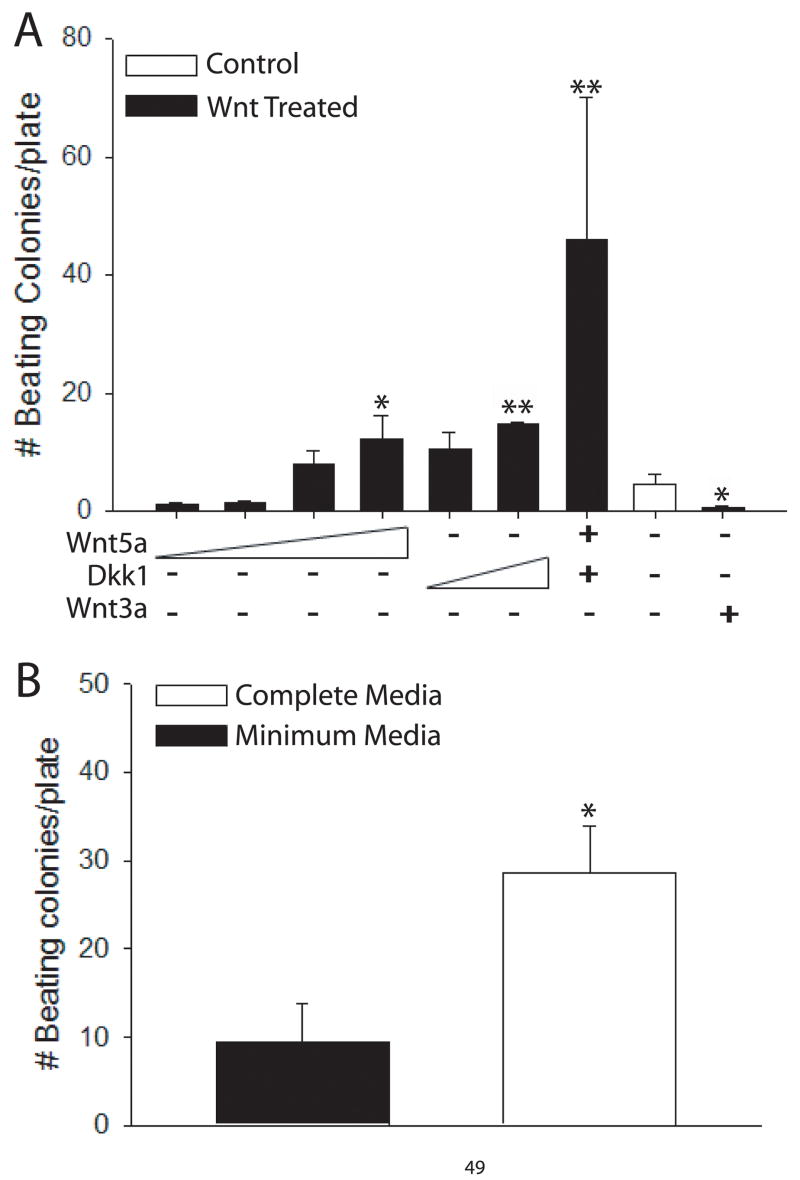

Recombinant proteins known to act on key signaling cascades of the Wnt pathway were applied to acutely isolated SVCs. Specifically, we used the non-canonical Wnt agonists Wnt5a, which signals through calcium, PKC, and JNK (Slusarski et al., 1997), or the canonical Wnt antagonist Dickkopf 1 (Dkk1) (Foley and Mercola, 2005), which blocks signaling through beta catenin. Wnt5a and Dkk1 independently increased the differentiation potential of SVCs toward the beating myocyte phenotype in a dose dependent manner as shown by increased beating colonies after two weeks of in vitro differentiation compared to non-treated controls (12.3 ± 3.8 vs. 4.5 ± 1.5; P < 0.05 and 14.6 ± 0.3 vs. 4.5 ± 1.5; P < 0.01, respectively) (Figure 5A). Furthermore, when combined, Wnt5a and Dkk1 had a synergistic effect resulting in significant induction of cultured SVCs into spontaneously beating cardiac myocytes compared to control (46 ± 24.1 vs. 4.5 ±1.5; P < 0.01). In contrast, the canonical Wnt agonist, Wnt3a, which activates the Wnt pathway mediated through beta-catenin (Nakamura et al., 2003), significantly inhibited cardiac differentiation of SVCs based on the absence of beating colonies compared to non-treated controls (0.5 ± 0.4 vs. 4.5 ± 1.5; P < 0.01) (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Treatment of cultured SVCs with recombinant Wnt proteins and cytokines.

(A) Acutely isolated adipose derived SVCs were cultured in methylcellulose media (GF M3534) with the addition of recombinant proteins including the non-canonical Wnt agonist Wnt5a (concentrations: 10 ng/mL, 20 ng/mL, 40 ng/mL, and 80 ng/mL), the canonical Wnt antagonist Dickkopf 1 (Dkk1) (concentrations: 40 ng/mL and 80 ng/mL), Wnt5a/Dkk1 together (50ng/mL of each protein), or the canonical Wnt agonist Wnt3a (80 ng/mL). * = P < 0.05 and ** = P < 0.01 compared to control. (B) Acutely isolated SVCs were cultured in cytokine replete minimum media (GF M3234) or complete media (GF M3534) enriched with cytokines Il-3 (10 ng/mL), Il-6 (10 ng/mL), and stem cell factor (SCF) (50 ng/mL). n = 5 cultures from 2 or more preparations. * = P < 0.05. All values are mean ± s.e.m. Data were analyzed by student’s t-test.

In addition to Wnts, we compared the growth potential of SVCs in cytokine replete minimum media (GF M3234) compared to cytokine enriched complete media (GF M3534). Cytokines present only in complete media included Il-6, part of the gp130 family of cytokines, as well as Il-3 and Stem Cell Factor (SCF) both of which belong to the same structural class of cytokines first observed for growth hormone (Woldbaek et al., 2002;Seiler et al., 2001). After two weeks in vitro, we found that SVCs differentiated significantly more effectively in complete media compared to minimum media (28.5 ± 5.3 vs. 9.5 ± 4.3; P < 0.05) (Figure 5B). Both Wnt and cytokine treated cultures resulted in no change in protein expression profiles compared to non-treated controls after two weeks of in vitro differentiation as shown in figure 2 (data not shown).

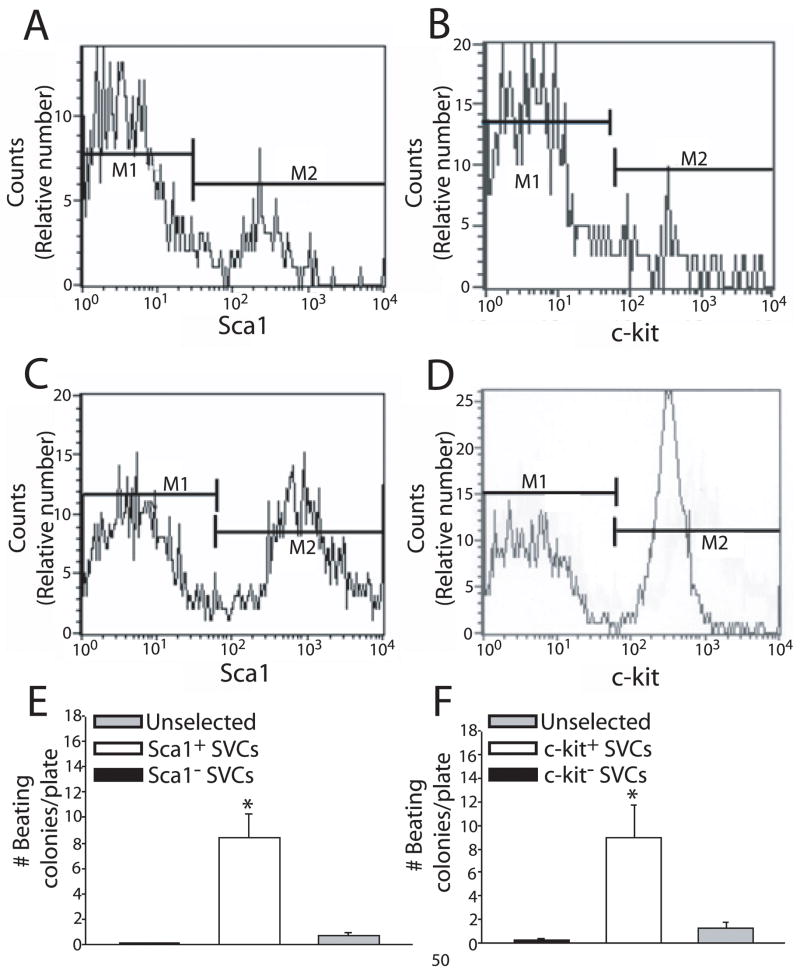

SVCs capable of differentiating into spontaneously beating cardiac myocytes can be enriched by selecting for cells expressing Sca1 and c-kit

Throughout the field of somatic stem cell research, mechanisms have been derived for isolating progenitor cells out of heterogeneous cell populations. Consistent with these methodologies, we tested the hypothesis that SVCs could be isolated out of adipose tissue using stem cell specific membrane markers including Sca1 and c-kit. We found that acutely isolated murine adipose tissue contains both Sca1+ and c-kit+ cells (Figure 6 A, B). Three cycles of selection for these cells using antibody-tagged magnetic nanoparticles results in significant purification of the Sca1+ population (Figure 6C) and the c-kit+ population (Figure 6D). To determine if these stem cell populations are comprised of SVCs, we cultured enriched Sca1+ and c-kit+ cells separately in complete media (GF M3534). After two weeks of in vitro differentiation, the Sca1 enriched (Figure 6E) and the c-kit enriched (Figure 6F) populations contained significantly greater numbers of spontaneously beating colonies compared to their respective negative populations and non-selected controls (8.4 ± 1.9 vs. 0.1 ± 0.05 vs. 0.7 ± 0.3; P < 0.01 and 9 ± 2.7 vs. 0.2 ± 0.15 vs. 1.2 ± 0.52; P < 0.01, respectively). The protein expression profile for both Sca1 and c-kit selected cells after in vitro differentiation was not different from non-selected cells (data not shown, see figure 2).

Figure 6. Analysis of Sca1 and c-kit selected SVCs.

Flow cytometry analysis of purified SVCs prior to Sca1 selection (A), after three rounds of Sca1 selection (B), prior to c-kit selection (C), and after three rounds of c-kit selection (D). Comparison between Sca1+, Sca1−, and non-selected SVCs (E) as well as c-kit+, c-kit−, and non-selected SVCs (F) to form SVC-derived spontaneously beating cardiac myocytes after two weeks of in vitro differentiation. n = 5 cultures from 3 or more preparations. * = P < 0.01 for positive selected cells compared to negative selected cells and unselected cells. All values are mean ± s.e.m. Data were analyzed by student’s t-test.

Discussion

This study provides new data contributing to our understanding of adipose-derived SVCs as cardiac progenitor cells. Although previous studies have reported the myogenic potential of this cell population (Planat-Benard et al., 2004a), this study provides evidence supporting their nature as stem cells with adult cardiac developmental potential. First, this study shows for the first time that differentiating adipose-derived SVCs express protein isoform changes representing the full progression of cardiac lineage development from the embryonic heart to the adult heart (Figure 2). Second, these data indicate that differentiated SVCs show the presence of calcium transients and contractility similar to adult myocytes (Figures 3 and 4). Third, this study shows that Wnt and cytokine signaling (Figure 5) affect the differentiation potential of SVCs consistent with their effects during embryonic cardiogenesis. Fourth, we have defined specific mechanisms for cytometrically selecting cardiogenic SVCs from adipose tissue using stem cell specific membrane markers Sca1 and c-kit (Figure 6).

Cardiac development is defined in part by changes in protein expression that enable progression from the neonatal myocyte to the adult myocyte structurally and functionally. One of the unequivocal identifiers of this developmental switch is defined by an irreversible change from the slow skeletal troponin I (TnI) isoform during neonatal development to the adult cardiac TnI isoform around the time of birth. We show here for the first time that SVC-derived cardiac myocytes are able to express both the early developmental ssTnI and the adult cTnI isoform during the time course of in vitro differentiation. Further evidence for cardiac lineage development was seen in the presence of other thin filament proteins cTnT, α-sarcomeric actin, and tropomyosin (Figure 2).

SVC-derived beating cardiac myocytes show some functional similarities to adult mouse cardiac myocytes based on the presence of calcium transients and cellular contractility (Figure 3). We found that SVC-derived cardiac myocytes show the presence of spontaneous contractile activity associated with corresponding calcium transients (Figure 3). These functional characteristics were also observed when differentiated SVCs were exposed to field stimulation. The ablation of spontaneous contractions was observed after the addition of a muscarinic agonist indicating that SVCs have a cardiac pacemaker phenotype.

Despite the cardiac characteristics observed by differentiated SVCs, closer analysis of calcium homeostasis showed significant differences between paced SVC-derived myocytes, spontaneously beating SVC-derived myocytes and murine adult cardiac myocytes. The rate of calcium sequestration was significantly faster in spontaneously beating SVC-derived cardiac myocytes compared to either paced SVC-derived myocytes or adult cardiac myocytes (Figure 4A). We observed that spontaneously beating SVCs had an intrinsic pacing rate of about two Hz with a maximum frequency of about four Hz (data not shown). Our data are consistent with previous reports that have shown a rate-dependent increase in calcium transient kinetics during higher pacing frequencies (Layland and Kentish, 1999). Although aspects of calcium handling that regulate the rate of calcium release and sequestration are not known in differentiated SVC-derived myocytes, these data suggest a similarity in calcium handling kinetics between SVC-derived myocytes and the adult heart. Further studies are required to look more closely at the changes in calcium transient kinetics over the course of in vitro differentiation.

Sarcoplasmic reticulum formation during cardiac development can give some insight into the maturity of stem cell differentiation. As an indirect measure of SR development, treatment of cells with isoproterenol can provide evidence for the stage of cell maturity. Previously Planat-Benard et al (Planat-Benard et al., 2004a) showed that SVCs are able to respond to treatment with isoproterenol in a dose dependent manner. Among its numerous effects, isoproterenol results in functional changes in SR proteins including SERCA and the ryanodine receptor. These changes, in part, regulate calcium handling and contribute to the observed increase in beating rate and contractility derivatives during isoproterenol treatment. Although this is an indirect measure of SR function, this data indicates that SR proteins within differentiated SVCs respond similar to those of adult cardiac myocytes.

In addition to studying the basic biology of SVC differentiation, this study provides significant input into our understanding of mechanisms for enriching SVC-derived cardiac myocytes. To begin, in recent years debate has ensued within the field of cardiac myogenesis regarding the role of Wnt signaling in stem cell differentiation along the cardiac lineage(Koyanagi et al., 2005;Naito et al., 2005;Nakamura et al., 2003;Pandur et al., 2002;Terami et al., 2004). Wnts are a family of secreted glycoproteins necessary for numerous aspects of embryonic development including the heart (Miller, 2002). We show that the differentiation potential of SVCs into beating cardiac myocytes increases in response to the non-canonical agonist Wnt5a and the canonical Wnt antagonist Dkk1. However, the cardiac lineage differentiation of SVCs was significantly inhibited by the canonical Wnt agonist Wnt3a (Figure 5A). Mechanistically these findings are supported by recent studies using canonical Wnt antagonists (e.g. Dkk1) which suggests that early cardiac lineage gene expression (e.g. Nkx2.5, Tbx4, GATA4) during embryonic cardiogenesis and cardiac myogenesis of stem cells occurs 1) by directly inhibiting canonical Wnt signaling and 2) by indirectly activating non-canonical Wnt signaling through JNK (Foley and Mercola, 2005;Naito et al., 2005;Nakamura et al., 2003;Pandur et al., 2002). In contrast, activation of the non-canonical Wnt signaling pathway (e.g. Wnt5a) has been found to promote cardiogenesis during embryonic development and in vitro stem cell differentiation (Sachinidis et al., 2003;Koyanagi et al., 2005;Pandur et al., 2002). Specifically, it appears that non-canonical Wnt signaling 1) directly activates CamKII and PKC/JNK and 2) indirectly inhibits canonical Wnt signaling at multiple levels. Together, these promote expression of developmental cardiac genes such as α-MHC and adult cardiac TnI (Foley and Mercola, 2005;Maye et al., 2004). It can be seen, therefore, that the combined effects of Wnt5a and Dkk1 result in strong inhibition of canonical Wnt signaling and correspondingly strong activation of the non-canonical Wnt signaling pathway leading to a profound induction of cardiac lineage development. Our data show that SVC differentiation is stimulated by the non-canonical Wnt pathway and is inhibited by the canonical Wnt pathway which corroborates with the hypothesis that SVCs contain a predetermined potential for cardiac lineage development.

Together with Wnts, cytokines are also essential for proper cardiac development (Seiler et al., 2001;Wollert and Chien, 1997;Ulich et al., 1991). Although research has been performed on the in vivo role of cytokines in cell therapies and heart repair(Ebelt et al., 2007), no research has been performed on the role of cytokines on in vitro stem cell differentiation along the cardiac lineage. We tested the hypothesis that cytokines would enhance the cardiac differentiation potential of SVCs in vitro. Our data indicate that Il-3, Il-6, and stem cell factor (SCF) together are capable of stimulating the differentiation of SVCs into spontaneously beating cardiac myocytes (Figure 5B). This study does not analyze the mechanistic basis of this observation. However, known aspects of cytokine signaling may explain our data. First, reports have shown that activation of gp130 by Il-6 results in expression of the cardiac fetal gene program (e.g. β-myosin heavy chain, and ANF). Furthermore, Il-3, Il-6, and SCF together with other cytokines have been shown to act synergistically to be potent stimulators of stem cell survival and proliferation (Zsebo et al., 1990;Nocka et al., 1990;Martin et al., 1990). Here we have shown that cytokine treated media acts as a second methodology for increasing the yield of differentiated cardiac myocytes from adipose-derived SVCs.

Lastly, we hypothesized that if SVCs are stem cells then common membrane markers for stem cells could be used to select for the cardiac progenitor cell population. We chose to select for the orphaned receptor and stem cell marker Sca1 (Ly-6A/E) as well as c-kit (CD-117), the ligand receptor for stem cell factor. Interestingly, no previous studies have shown that adipose tissue contains a population of Sca1+ cells (Figure 6A) as well as a more modest population of c-kit+ cells (Figure 6B). In this study, we enriched these cell populations (Figure 6C and D) and found that this yielded a significantly greater number of SVC-derived cardiac myocytes after two weeks of in vitro differentiation (Figure 6E and F). Due to the prevalence of Sca1 and c-kit in stem cells derived from multiple murine tissues in addition to the fact that these markers are classic identifiers of nearly all well-defined stem cell populations (e.g. hematopoeitic, mesenchymal, side population (SP)) (Bunting and Hawley, 2003) we cannot make any conclusions as to the specific cell type that correlates to adipose-derived SVCs. However, numerous additional cell markers have been shown to be identifiers for cardiac lineage development including Sca1, c-kit, Isl-1, Flk-1, Side Population (Hoechst 33342 exclusion), and others. Previous reports invoking the use of adipose derived stem cells have primarily focused on isolating mesenchymal stem cells with the following selection criteria: CD29+, CD34−, CD45−(Yamada et al., 2006;Miyahara et al., 2006;Strem et al., 2005b;Strem et al., 2005a). Reports showing the presence of mesenchymal-like stem cells in adipose tissue argues for the hypothesis that SVCs are of mesenchymal origin, however, further analysis of the aforementioned cardiac lineage markers and stem cell markers is required for clarification of this matter.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank DeWayne Townsend DVM, Ph.D., Eric Devaney MD, Todd Herron Ph.D., and Jennifer Davis for contributing training or insight into the progress of this study include. We also thank Omar Yilmaz and Mark Kiel from the lab of Dr. Sean Morrison for assistance with flow cytometry assays. Support was provided by the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- Bai X, Pinkernell K, Song YH, Nabzdyk C, Reiser J, Alt E. Genetically selected stem cells from human adipose tissue express cardiac markers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:665–671. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting KD, Hawley RG. Integrative molecular and developmental biology of adult stem cells. Biology of the Cell. 2003;95:563–578. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon RO. Cardiovascular potential of BM-derived stem and progenitor cells. Cytotherapy. 2004;6:602–607. doi: 10.1080/14653240410005294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SC, Yoon J, Shim WJ, Ro YM, Lim DS. 5-azacytidine induces cardiac differentiation of P19 embryonic stem cells. Experimental and Molecular Medicine. 2004;36:515–523. doi: 10.1038/emm.2004.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day SM, Westfall MV, Fomicheva EV, Hoyer K, Yasuda S, La Cross NC, D’Alecy LG, Ingwall JS, Metzger JM. Histidine button engineered into cardiac troponin I protects the ischemic and failing heart. Nat Med. 2006;12:181–189. doi: 10.1038/nm1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebelt H, Jungblut M, Zhang Y, Kubin T, Kostin S, Technau A, Oustanina S, Niebrugge S, Lehmann J, Werdan K, Braun T. Cellular Cardiomyoplasty: Improvement of Left Ventricular Function Correlates with the Release of Cardioactive Cytokines. Stem Cells. 2007;25:236–244. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg LM, Burns L, Eisenberg CA. Hematopoietic cells from bone marrow have the potential to differentiate into cardiomyocytes in vitro. Anatomical Record Part A-Discoveries in Molecular Cellular and Evolutionary Biology. 2003;274A:870–882. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley AC, Mercola M. Heart induction by Wnt antagonists depends on the homeodomain transcription factor Hex. Genes & Development. 2005;19:387–396. doi: 10.1101/gad.1279405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser JK, Schreiber R, Strem B, Zhu M, Alfonso Z, Wulur I, Hedrick MH. Plasticity of human adipose stem cells toward endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2006a;3(Suppl 1):S33–S37. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser JK, Schreiber RE, Zuk PA, Hedrick MH. Adult stem cell therapy for the heart. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2004;36:658–666. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser JK, Wulur I, Alfonso Z, Hedrick MH. Fat tissue: an underappreciated source of stem cells for biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2006b;24:150–154. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng BC, Haider HK, Sim EKW, Cao T, Ng SC. Strategies for directing the differentiation of stem cells into the cardiomyogenic lineage in vitro. Cardiovascular Research. 2004;62:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyanagi M, Haendeler J, Badorff C, Brandes RP, Hoffmann J, Pandur P, Zeiher AM, Kuhl M, Dimmeler S. Non-canonical Wnt signaling enhances differentiation of human circulating progenitor cells to cardiomyogenic cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16838–16842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500323200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layland J, Kentish JC. Positive force- and [Ca2+]i-frequency relationships in rat ventricular trabeculae at physiological frequencies. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H9–18. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.1.H9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leri A, Kajstura J, Anversa P. Cardiac stem cells and mechanisms of myocardial regeneration. Physiological Reviews. 2005;85:1373–1416. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin FH, Suggs SV, Langley KE, Lu HS, Ting J, Okino KH, Morris CF, McNiece IK, Jacobsen FW, Mendiaz EA. Primary structure and functional expression of rat and human stem cell factor DNAs. Cell. 1990;63:203–211. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90301-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maye P, Zheng J, Li L, Wu DQ. Multiple mechanisms for Wnt11-mediated repression of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24659–24665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311724200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner JD, Umeda PK, Chang KC, Gros G, Scheibe RJ. Activation of the beta myosin heavy chain promoter by MEF-2D, MyoD, p300, and the calcineurin/NFATc1 pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:138–148. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JR. The Wnts. Genome Biol. 2002;3:REVIEWS3001. doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-3-1-reviews3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyahara Y, Nagaya N, Kataoka M, Yanagawa B, Tanaka K, Hao H, Ishino K, Ishida H, Shimizu T, Kangawa K, Sano S, Okano T, Kitamura S, Mori H. Monolayered mesenchymal stem cells repair scarred myocardium after myocardial infarction. Nature Medicine. 2006;12:459–465. doi: 10.1038/nm1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley TA, Zhu M, Hedrick MH. Adipose-derived stem and progenitor cells as fillers in plastic and reconstructive surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:121S–128S. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000234609.74811.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss RL, Fitzsimons DP. Myosin Light Chain 2 Into the Mainstream of Cardiac Development and Contractility. Circ Res. 2006;99:225–227. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000236793.88131.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito AT, Akazawa H, Takano H, Minamino T, Nagai T, Aburatani H, Komuro I. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway plays a critical role in early cardiomyogenesis by regulating canonical Wnt signaling. Circ Res. 2005;97:144–151. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000175241.92285.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami H, Morishita R, Maeda K, Kikuchi Y, Ogihara T, Kaneda Y. Adipose tissue-derived stromal cells as a novel option for regenerative cell therapy. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2006;13:77–81. doi: 10.5551/jat.13.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Sano M, Songyang Z, Schneider MD. A Wnt- and beta-catenin-dependent pathway for mammalian cardiac myogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:5834–5839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0935626100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocka K, Buck J, Levi E, Besmer P. Candidate ligand for the c-kit transmembrane kinase receptor: KL, a fibroblast derived growth factor stimulates mast cells and erythroid progenitors. EMBO J. 1990;9:3287–3294. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandur P, Lasche M, Eisenberg LM, Kuhl M. Wnt-11 activation of a non-canonical Wnt signalling pathway is required for cardiogenesis. Nature. 2002;418:636–641. doi: 10.1038/nature00921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AM, Katz AJ. Adipose-derived stem cells for the regeneration of damaged tissues. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2006;6:567–578. doi: 10.1517/14712598.6.6.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planat-Benard V, Menard C, Andre M, Puceat M, Perez A, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Penicaud L, Casteilla L. Spontaneous cardiomyocyte differentiation from adipose tissue stroma cells. Circ Res. 2004a;94:223–229. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000109792.43271.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planat-Benard V, Silvestre JS, Cousin B, Andre M, Nibbelink M, Tamarat R, Clergue M, Manneville C, Saillan-Barreau C, Duriez M, Tedgui A, Levy B, Penicaud L, Casteilla L. Plasticity of human adipose lineage cells toward endothelial cells - Physiological and therapeutic perspectives. Circulation. 2004b;109:656–663. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114522.38265.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachinidis A, Fleischmann BK, Kolossov E, Wartenberg M, Sauer H, Hescheler J. Cardiac specific differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Cardiovascular Research. 2003;58:278–291. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00248-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler P, Plenz G, Deng MC. The interleukin-6 cytokine system in embryonic development, embryo-maternal interactions and cardiogenesis. European Cytokine Network. 2001;12:15–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slusarski DC, YangSnyder J, Busa WB, Moon RT. Modulation of embryonic intracellular Ca2+ signaling by Wnt-5A. Developmental Biology. 1997;182:114–120. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strem BM, Hicok KC, Zhu M, Wulur I, Alfonso Z, Schreiber RE, Fraser JK, Hedrick MH. Multipotential differentiation of adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Keio J Med. 2005a;54:132–141. doi: 10.2302/kjm.54.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strem BM, Jordan MC, Kim JK, Yang JQ, Anderson CD, Daniels EJ, Hedrick MH, Roos KP, Schreiber RE, Fraser JK, MacLellan WR. Adipose tissue-derived stem cells enhance cardiac function following surgically-induced myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2005b;112:U330. [Google Scholar]

- Terami H, Hidaka K, Katsumata T, Iio A, Morisaki T. Wnt11 facilitates embryonic stem cell differentiation to Nkx2.5-positive cardiomyocytes. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;325:968–975. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulich TR, delCastillo J, Yi ES, Yin SM, Mcniece I, Yung YP, Zsebo KM. Hematologic Effects of Stem-Cell Factor Invivo and Invitro in Rodents. Blood. 1991;78:645–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woldbaek PR, Hoen IB, Christensen G, Tonnessen T. Gene expression of colony-stimulating factors and stem cell factor after myocardial infarction in the mouse. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 2002;175:173–181. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2002.00989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollert KC, Chien KR. Cardiotrophin-1 and the role of gp130-dependent signaling pathways in cardiac growth and development. Journal of Molecular Medicine-Jmm. 1997;75:492–501. doi: 10.1007/s001090050134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y, Wang XD, Yokoyama S, Fukuda N, Takakura N. Cardiac progenitor cells in brown adipose tissue repaired damaged myocardium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:662–670. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsebo KM, Williams DA, Geissler EN, Broudy VC, Martin FH, Atkins HL, Hsu RY, Birkett NC, Okino KH, Murdock DC, Jacobsen FW, Langley KE, Smith KA, Takeish T, Cattanach BM, Galli SJ, Suggs SV. Stem cell factor is encoded at the SI locus of the mouse and is the ligand for the c-kit tyrosine kinase receptor. Cell. 1990;63:213–224. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90302-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.