Abstract

In the present study, we have used DNA microarray and quantitative real-time PCR analysis to examine the transcriptional changes that occur in response to cellular depletion of the yeast acyl-CoA-binding protein, Acb1p. Depletion of Acb1p resulted in the differential expression of genes encoding proteins involved in fatty acid and phospholipid synthesis (e.g. FAS1, FAS2, ACC1, OLE1, INO1 and OPI3), glycolysis and glycerol metabolism (e.g. GPD1 and TDH1), ion transport and uptake (e.g. ITR1 and HNM1) and stress response (e.g. HSP12, DDR2 and CTT1). In the present study, we show that transcription of the INO1 gene, which encodes inositol-3-phosphate synthase, cannot be fully repressed by inositol and choline, and UASINO1 (inositol-sensitive upstream activating sequence)-driven transcription is enhanced in Acb1p-depleted cells. In addition, the reduction in inositol-mediated repression of INO1 transcription observed after depletion of Acb1p appeared to be independent of the transcriptional repressor, Opi1p. We also demonstrated that INO1 and OPI3 expression can be normalized in Acb1p-depleted cells by the addition of high concentrations of exogenous fatty acids, or by the overexpression of FAS1 or ACC1. Together, these findings revealed an Acb1p-dependent connection between fatty acid metabolism and transcriptional regulation of phospholipid biosynthesis in yeast. Finally, expression of an Acb1p mutant which is unable to bind acyl-CoA esters could not normalize the transcriptional changes caused by Acb1p depletion. This strongly implied that gene expression is modulated either by the Acb1p–acyl-CoA ester complex directly or by its ability to donate acyl-CoA esters to utilizing systems.

Keywords: acyl-CoA-binding protein (ACBP), fatty acid, inositol, phospholipid, transcriptional regulation

Abbreviations: ACBP, acyl-CoA-binding protein; COP, cytidyl diphosphate; Cy3, indocarbocyanine; Cy5, indodicarbocyanine; ER, endoplasmatic reticulum; ESI, electrospray ionization; FAS, fatty acid synthase; HA, haemagglutinin; HNF-4α, hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α; HRP, horseradish peroxidase; LCACoA, long-chain acyl-CoA; L-FABP, liver FABP; LC, liquid chromatography; Opi−, overproduction of inositol; PA, phosphatidic acid; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PS, phosphatidylserine; Q-RT-PCR, quantitative real-time PCR; SC, synthetic complete; SCP, sterol carrier protein; UASINO1, inositol-sensitive upstream activating sequence; UPR, unfolded protein response; YNB, yeast nitrogen base; YNBD, YNB and dextrose; YPD, yeast extract, peptone and dextrose; YPgal, yeast extract, peptone and galactose

INTRODUCTION

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, fatty acids and fatty acid derivatives have been suggested to function as regulators of gene expression. This suggestion is supported by the fact that two oleate-activated transcription factors, Oaf1p and Pip2p, have been shown to be essential for fatty-acid-mediated induction of genes encoding peroxisomal enzymes and proteins [1]. Furthermore, transcriptional regulation of the yeast Δ9 desaturase OLE1 by unsaturated fatty acids involves Spt23p and Mga2p [2].

It has been suggested that the regulatory properties of fatty acids are mediated through their activation to acyl-CoA esters, since fatty acids are unable to repress the expression of ACC1 [3] and OLE1 [4] and induce expression of the peroxisomal enzymes, acyl-CoA oxidase (POX1) and acyl-CoA synthetase (FAA2) [5] in S. cerevisiae depleted of the two acyl-CoA synthetases, Faa1p and Faa4p. However, disruption of both FAA1 and FAA4 affects fatty acid import, and does not prove that fatty acid activation is necessarily required for fatty-acid-mediated regulation of gene expression.

In S. cerevisiae, LCACoA (long-chain acyl-CoA) esters are either synthesized endogenously by the FAS (fatty acid synthase) complex or produced from exogenous fatty acids imported by the fatty acid import machinery. Inside the cell, acyl-CoA esters are bound to proteins in order to increase their solubility and to protect them from hydrolysis by thioesterases. A number of intracellular proteins have been reported to bind LCACoA esters, including L-FABP (liver fatty-acid-binding protein), SCP (sterol carrier protein)-2 and ACBP (acyl-CoA-binding protein). L-FABP is predicted to have a role in LCACoA ester metabolism, and this is highlighted by the fact that L-FABP-knockout mice display an altered cytosolic LCACoA ester-binding capacity and ester acyl-chain distribution [6]. Similarly, SCP-2/SCP-X-knockout mice demonstrate impaired catabolism of methyl-branched fatty acyl-CoAs, inefficient transport of phytanoyl-CoA into peroxisomes and defective thiolytic cleavage of 3-oxopristanoyl-CoA [7]. However, S. cerevisiae does not express fatty-acid-binding protein [8] or a SCP-2 homologue [9]. Thus S. cerevisiae is suited for use as a model to study the function of ACBP, since potential compensatory effects caused by L-FABP and/or SCP-2 can be avoided.

Yeast ACBP, Acb1p, belongs to a large multi-gene family encoding a protein approx. 10 kDa in size. Acb1p binds LCACoA esters in a non-covalent and reversible manner with very high affinity (Kd of 1–10 nM) and specificity [10]. ACBP has been very highly conserved throughout evolution, and it has been detected in all eukaryotic organisms examined so far [11]. The high degree of sequence and structural conservation of ACBP among eukaryotic species, and the fact that human ACBP can complement ACBP function in yeast (S. Feddersen, J. Knudsen and N. J. Færgeman, unpublished work), suggest that its function is associated with one or more basal cellular function(s) common to all cells [11].

In vitro experiments have shown that ACBP can attenuate the inhibitory effect of LCACoA esters on acetyl-CoA carboxylase and the mitochondrial adenine nucleotide translocase, stimulate the mitochondrial long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase, and extract membrane-imbedded acyl-CoA esters and donate them to utilizing systems such as glycerolipid synthesis and β-oxidation [12,13]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that overexpression of Acb1p and bovine ACBP in S. cerevisiae increased the acyl-CoA ester pool size [14,15]. Thus ACBP may act as an acyl-CoA ester pool former and transporter in vivo. Despite this, the precise in vivo function of ACBP is currently unknown. Yeast cells which lack Acb1p activity display a variety of defects, including fragmented vacuoles, a multi-layered plasma membrane, accumulation of vesicles of variable sizes, a 3–5.5-fold elevation in the OLE1 mRNA level, and reduced levels of very-long-chain fatty acids, ceramides and sphingolipids [4,16,17]. Owing to the high affinity of ACBP for acyl-CoA esters and the presence of cytosolic acyl-CoA hydrolases, the intracellular free acyl-CoA ester concentration is predicted to be very low [10]. It can therefore be expected that the Acb1p–acyl-CoA ester complex can modulate processes which are regulated by acyl-CoA esters and processes which consume acyl-CoA esters, either directly or indirectly through the donation of acyl-CoA esters.

In the present study, we used whole genome cDNA microarrays and Q-RT-PCR (quantitative real-time PCR) in order to identify transcriptional changes in response to the cellular depletion of Acb1p. Current knowledge suggested that depletion of Acb1p changes the expression of genes encoding proteins involved in fatty acid and phospholipid synthesis, glycolysis, glycerol metabolism, ion transport/uptake and the stress response. Moreover, the present study has identified an Acb1p-dependent connection between fatty acid metabolism and transcriptional regulation of phospholipid biosynthesis in yeast. It also demonstrated that the regulatory effects of Acb1p depended on its ability to bind acyl-CoA esters.

EXPERIMENTAL

Chemicals

Bacto peptone, yeast extract and YNB (yeast nitrogen base) were purchased from Difco (BD Diagnostic Systems). HRP (horseradish peroxidase)-conjugated goat anti-(mouse IgG) and goat anti-(rabbit IgG) secondary antibodies were obtained from Promega. Restriction enzymes and DNA/RNA-modifying enzymes were either from New England Biolabs or Invitrogen. All chemicals were of analytical grade.

Yeast strains, media and growth

The S. cerevisiae strains used in the present study are listed in Table 1. Y700 pGAL-ACB1 is a conditional knockout strain constructed by insertion of the GAL1 promoter in front of the ACB1 gene, as described by Gaigg et al. [16]. In the wild-type strain, Y700, and the Y700 pGAL-ACB1 strain, single disruptions in SCS2 and PLD1 (SPO14), in which the target ORF (open reading frame) was disrupted by the TRP1 marker, were constructed by PCR-mediated gene replacement using pFA6a-TRP1 as a template (a gift from Professor John R. Pringle, Department of Biology, The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, U.S.A.) as described previously [18]. Disruption of the HAC1 gene was achieved by homologous recombination of the BamHI-linearized pHAKO1 plasmid (a gift from Professor Peter Walter, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, U.S.A.) into the wild-type strain, Y700, and the Y700 pGAL-ACB1 strain. Correct integration of TRP1 PCR products and pHAKO1 in Y700 and Y700 pGAL-ACB1 cells was confirmed by PCR. Media used to grow yeast included YPD (yeast extract, peptone and dextrose), YPgal (yeast extract, peptone and galactose) and YNBD (YNB and dextrose), made as described previously [17], and glucose-supplemented SC (synthetic complete) medium, made as described by Sherman [19]. Myo-inositol was either omitted from SC medium or added to the concentration indicated as required. Choline was added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and palmitic acid or palmitoleic acid was added to a final concentration of 500 μM where indicated. Yeast strains were established on YPgal or YNBgal (YNB and galactose) medium and cultivated at 30 °C. Prior to experimentation, glucose-supplemented SC, YNBD or YPD medium was inoculated with yeast cells to a D600 (attenuance) of 0.005–0.01 and grown for 24 h. These cultures were diluted into fresh medium to a D600 of 0.05–0.1 and grown to the required D600. Depletion of Acb1p was confirmed by Western blotting after each experiment.

Table 1. Strains used in the present study.

| Strain | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Y700 | MATa, ade2-1 trp1 can1-100 leu2-112 his3-11 his3-15 ura3 | [16] |

| Y700 pGAL-ACB1 | MATa, ade2-1 trp1 can1-100 leu2-112 his3-11 his3-15 ura3, pGAL-ACB1::KanMX | [16] |

| Y700 INO1-HA3 | MATa, ade2-1 trp1 can1-100 leu2-112 his3-11 his3-15 ura3, INO1-HA3::His3MX | Present study |

| Y700 pGAL-ACB1 INO1-HA3 | MATa, ade2-1 trp1 can1-100 leu2-112 his3-11 his3-15 ura3, pGAL-ACB1::KanMX, INO1-HA3::His3MX | Present study |

| Y700 scs2Δ | MATa, ade2-1 trp1 can1-100 leu2-112 his3-11 his3-15 ura3, SCS2::TRP1 | Present study |

| Y700 pGAL-ACB1 scs2Δ | MATa, ade2-1 trp1 can1-100 leu2-112 his3-11 his3-15 ura3, pGAL-ACB1::KanMX, SCS2::TRP1 | Present study |

| AID | MATa/MATα, ade1/ade1 ino1/ino1 | S. Henry* |

| Y700 pld1Δ | MATa, ade2-1 trp1 can1-100 leu2-112 his3-11 his3-15 ura3, PLD1::TRP1 | Present study |

| Y700 pGAL-ACB1 pld1Δ | MATa, ade2-1 trp1 can1-100 leu2-112 his3-11 his3-15 ura3, pGAL-ACB1::KanMX, PLD1::TRP1 | Present study |

| Y700 hac1Δ | MATa, ade2-1 trp1 can1-100 leu2-112 his3-11 his3-15 ura3, HAC1::URA3 | Present study |

| Y700 pGAL-ACB1 hac1Δ | MATa, ade2-1 trp1 can1-100 leu2-112 his3-11 his3-15 ura3, pGAL-ACB1::KanMX, HAC1::URA3 | Present study |

*AID was a gift from Professor Susan Henry, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, U.S.A. [22]

Protein extraction, electrophoresis and Western blotting

Protein extraction, electrophoresis and Western blotting was performed as described in [17], with the exception that PVDF membranes were used instead of nitrocellulose membranes. Mouse influenza HA (haemagglutinin) antiserum was obtained from Roche Diagnostics and used at a 1:5000 dilution. HRP-conjugated goat anti-(mouse IgG) and goat anti-(rabbit IgG) secondary antibodies were both used at a concentration of 1:8000.

DNA microarray

Yeast DNA microarrays were purchased from MWG. A total of 6250 gene-specific oligonucleotide probes (40-mers) representing the complete S. cerevisiae genome were spotted on to one single epoxy-coated slide (1.8 cm×3.6 cm). In addition, each MWG Yeast Array contained 86 replicated spots and 32 Arabidopsis control spots.

Yeast culture and total RNA isolation

Wild-type (Y700) and conditional ACB1-knockout (Y700 pGAL-ACB1) cells were grown to a D600 of 0.9–1.3 in YPD, YNBD or glucose-supplemented SC medium as described above. Following growth, cells were collected by centrifugation at 4500 g for 10 min at 4 °C in 50 ml Falcon tubes half-filled with crushed ice. The supernatant was removed, and cells were transferred to 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tubes and pelleted by centrifugation at 12800 g for 3 min at 4 °C. Harvested cells were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Total RNA was extracted using the hot phenol method as described previously [20]. DNase I digestion of the extracted RNA was performed following the manufacturer's instructions (MWG).

cDNA synthesis and post-labelling

RNA was isolated from Y700 and Y700 pGAL-ACB1 cells grown in YPD medium. For cDNA synthesis and post-labelling, the CyScribe cDNA post-labelling kit (Amersham Biosciences) was used. cDNA synthesis and post-labelling was performed as described by the manufacturer (Amersham Biosciences), except that amino allyl-modified cDNA was purified using the Qiagen QIAquick PCR purification kit, in which the supplied wash and elution buffers were replaced with phosphate wash buffer [5 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, and 80% (v/v) ethanol] and phosphate elution buffer (4 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 8.5) respectively to avoid production of free amines.

Hybridization, washing and scanning

For hybridization, a formamide-based hybridization buffer (MWG) was used. Cy3 (indocarbocyanine)- and Cy5 (indodicarbocyanine)-labelled cDNA was pooled, dried, resuspended in 30 μl of pre-heated (42 °C for 10 min) formamide-based buffer (MWG) and then incubated at 95 °C for 3 min. This hybridization mixture was centrifuged briefly at 10000 g for 15 s at 22 °C and applied to the yeast DNA microarray under a clean coverslip. Slides were then placed into a wet hybridization chamber (GeneMachines®) and incubated for 18–22 h in a 42 °C water bath. After incubation, the microarrays were washed as described by the manufacturer (MWG). The arrays were then dried by centrifugation at 500 g for 2 min at room temperature (22 °C) and scanned at 532 nm (Cy3) and 635 nm (Cy5) in a GMS-418 scanner (Genetic MicroSystems). Overlay images were constructed using the microarray spot-finding and quantification software, ImaGene version 4.2 (BioDiscovery).

Experimental setup and data analysis

RNA isolated from five different cultures of either Y700 or Y700 pGAL-ACB1 cells grown in YPD medium was pooled in two different tubes. cDNA synthesized from Y700 and Y700 pGAL-ACB1 RNA was labelled with Cy3 and Cy5 respectively. The experiment was repeated on independent cultures with opposite Cy3/Cy5 labelling. Overlay images were processed using ImaGene version 4.2 software (BioDiscovery). Fluorescent spots were located, and extracted intensity values were corrected for local background by subtracting the intensity level around each spot from the spot's signal intensity. Intensities corrected for background were processed and analysed further using Acuity version 4.0 software (Axon Instruments). Data from each microarray were normalized using print-tip locally weighted linear regression (lowess) normalization, and average log2 (R/G) values (M values) were calculated. In dual-colour experiments, R and G represent the processed and normalized intensity values measured using the red and green channel respectively. Subsequently, data were filtered in order to remove unreliable data from the dataset. Quality measurements were collected using ImaGene 4.2 and used to identify low-quality spots. Two quality parameters were measured for each spot: the number of pixels that touch the signal area which are neither signal nor background and all of the ignored and background pixels that fall within the circle defined by the spot-finding method. Spots defined by this quality control method to be ‘bad quality’ and data with intensity levels below the highest intensity level of the 32 Arabidopsis control spots at 532 nm (Cy3) and 635 nm (Cy5) were removed. Furthermore, data that were not present in both microarrays were also excluded. M values were then transferred to Microsoft Excel and the S.D. was calculated. Data with S.D.>0.6 were removed. However, to avoid removing data which represented genes which were highly up- or down-regulated in both arrays but had S.D.>0.6, the list of removed data was checked for such important data. Finally, genes considered to be differentially expressed were identified using a fold-change filter, in which the cut-off was set to an absolute M value of 0.70 (which corresponded to a 1:1.6 ratio of expression between wild-type and Acb1p-depleted cells).

Q-RT-PCR, RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was isolated from cells cultured and harvested as described above. RNA was extracted using the hot phenol method as described previously [20] and treated with DNase I, following the manufacturer's instructions (MWG). cDNA was synthesized using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and random hexamers (deoxy-NTP6) (Amersham Biosciences). Q-RT-PCR was performed on an ABI PRISM 7700 RealTime PCR-machine (Applied Biosystems) using 2×SYBR Green JumpStart™ Taq ReadyMix™ and Sigma Reference Dye (Sigma–Aldrich), following the manufacturer's instructions. Reactions were incubated at 95 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 45 s. Fluorescence signals were measured during the elongation step, and all reactions were performed in duplicate. The level of the target mRNAs was examined and normalized to the level of the ACT1 gene (actin) using the 2−ΔΔCT method [21]. Primers for Q-RT-PCR were designed using Primer Express version 2.0 (Applied Biosystems), and the efficacy and specificity of the primers was tested by dilution experiments and melting curves respectively. Used primer sets are listed in Supplementary Table S1 (http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/407/bj4070219add.htm). Primer pairs were designed to amplify a fragment of approx. 50 bp, except for the HAC1 primer pairs which amplified a fragment of 91 bp.

β-Galactosidase assay in yeast

Y700 and Y700 pGAL-ACB1 cells transformed with plasmid pJH359 carrying an INO1-CYC1-lacZ fusion (a gift from Professor Susan Henry, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, U.S.A. [22]) were grown overnight in an appropriate medium, diluted to a D600 of 0.05–0.1 and grown to a D600 of 0.6–0.8. β-Galactosidase activity in yeast was determined as described previously [23]. β-Galactosidase activity (in units) was calculated according to the following equation:

|

where A420 is the absorbance of ONP (o-nitrophenol), D600 is the attenuance of the culture at the time of assay, volume is the amount of the culture used in the assay (in ml) and time is measured in min.

Complementation of INO1 expression by increased fatty acid synthesis

Increased fatty acid synthesis was achieved by transforming Y700 (wild-type) and the Y700 pGAL-ACB1 strains with high-copy plasmids expressing either ACC1 (pG1M-ACC1, a gift from Keiji Furukawa, Kiku-Masamune Sake Brewing Co., Kobe, Japan [24]) or FAS1 (pJS229, a gift from Professor Hans-Joachim Schüller, Universität Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany [25]). The corresponding empty vectors were transformed to be used as controls. Total RNA was extracted from exponentially growing cells cultured in selective SC medium supplemented with 0.2 mM inositol and used for Q-RT-PCR analysis.

Assay for the Opi− (overproduction of inositol) phenotype

To test for the Opi− phenotype, Acb1p-depleted cells and wild-type cells were dotted on to inositol-free SC plates and grown at 30 °C. Plates were then sprayed with a suspension of a diploid tester strain, AID (provided by Professor Susan Henry), which is homozygous for ino1 and ade1, and incubated at 30 °C as previously described [26].

LC (liquid chromatograhy)–ESI (electrospray ionization) MS of lipids

The number of Acb1p-depleted cells at a given D600, is reduced compared with wild-type cells, implying that Acb1p-depleted cells are bigger than wild-type cells (S. Feddersen, J. Knudsen and N. J. Færgeman, unpublished work). Thus whenever quantifying the relative phospholipid content of Acb1p-depleted cells compared with wild-type cells, we corrected for differences in cell numbers. Lipids were extracted from 25 D600 units of exponentially growing cells (D600 of ∼1) using procedure IIIA as described by Hanson and Lester [27]. Aliquots corresponding to 10 D600 units of cells were dissolved in 65 °C solvent A (chloroform/methanol/water, 16:16:5, by vol.) and mixed with internal standard lipids extracted from 10 D600 units of cells grown on 13C-glucose as the sole carbon source. The solvent was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen, and the lipids were redissolved in 10 μl of solvent A (heated to 65 °C) by stirring using a rotating pestle at 30000 rev./min for 5 min. Immediately after mixing, 1 μl of the lipid solution was injected on to a PVA SIL HPLC column (1 mm×150 mm, YMC Europe) and eluted at 45 μl/min. Solvents B (hexane/propan-2-ol, 98:2, v/v), C (chloroform/propan-2-ol, 65:35, v/v) and D (methanol) were changed linearly over time to give the proportions (by vol.) of B/C/D at the following time points: 0 min, 100:0:0; 22 min, 12:88:0; 30 min 10:74:16; 45 min, 8:61:31; 50–65 min, 0:0:100; 70–72.5 min, 0:100:0, and 75–82.5 min, 100:0:0. Ions in the effluent were ionized by ESI with an electrode potential of 3500 V, and the masses were detected using a Bruker Esquire-LC ion-trap mass spectrometer. The 12C/13C ratio of ion counts for each individual 12C species and one selected 13C species in each lipid class were calculated for both strains. Differences in the relative amount of individual lipid species between wild-type and Acb1p-depleted cells were calculated by dividing the wild-type 12C/13C ratio with the corresponding 12C/13C ratio of Acb1p-depleted cells. Species percentage composition, based on the sum of ion counts for all species within a certain lipid class, was calculated for all lipid classes. The content of a given phospholipid class in Acb1p-depleted cells was normalized to wild-type levels (wild-type=100%) and calculated using the following equation:

|

where Δ is Y700 pGAL-ACB1 and wild-type (Wt) is Y700.

RESULTS

Genome-wide changes in gene expression of S. cerevisiae in response to Acb1p depletion

DNA microarray profiling revealed that the effect of Acb1p depletion on gene expression is not restricted to OLE1 [4,16]. A total of 134 genes were identified as being differentially expressed more than 1.6-fold, of which 44 genes were down-regulated and 90 genes were up-regulated in Acb1p-depleted cells compared with wild-type cells.

Confirmation of microarray data by Q-RT-PCR

Expression of 22 selected genes, of which ten had been shown to be differently expressed by microarray analysis, was examined by Q-RT-PCR (Table 2). The ten genes identified by microarray analysis were all shown to be differentially expressed to the same degree by Q-RT-PCR analysis (Table 2). We propose that the identified changes in gene expression measured by microarray analysis may reflect actual changes in mRNA levels, in response to Acb1p depletion. However, in the present study, we primarily focus on microarray data which have been confirmed by Q-RT-PCR.

Table 2. Comparison of fold change (Acb1p depleted cells compared with wild-type cells) obtained by microarray and Q-RT-PCR analysis.

| Fold change* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene ID | Gene | Function | Process | Microarray analysis | Q-RT-PCR† |

| Stress response | |||||

| ygr088w | CTT1 | Catalase T, cytosolic | Response to stress | No data‡ | 3.1±0.14 |

| ybr072w | HSP26 | Heat-shock protein | Response to stress | No data‡ | 5.9±1.4 |

| yol052c-a | DDR2 | Heat-shock protein DDRA2 | Response to stress | 6.9±0.71 | 2.7±0.66 |

| yll026w | HSP104 | Heat-shock protein | Response to stress | No data‡ | 3.1±0.41 |

| yfl014w | HSP12 | Heat-shock protein | Response to stress | No data‡ | 6.8±1.6 |

| C-compound and carbohydrate metabolism | |||||

| ydl022w | GPD1 | Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (NAD+), cytoplasmic | Intracellular accumulation of glycerol | 6.4±1.8 | 5.5±0.89 |

| yjl052w | TDH1 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 | Glycolysis; gluconeogenesis | 4.8±0.16 | 3.3±0.91 |

| Lipid metabolism | |||||

| ygl055w | OLE1 | Stearoyl-CoA desaturase | Fatty acid desaturation | 1.9±0.75 | 1.9±0.45 |

| yjl196c | ELO1 | Fatty acid elongation protein | Fatty acid elongation | No data‡ | 1.2±0.11 |

| ykl182w | FAS1 | Fatty-acyl-CoA synthase, β chain | Fatty acid biosynthesis | 1.6±0.25 | 1.6±0.41 |

| ypl231w | FAS2 | Fatty-acyl-CoA synthase, α chain | Fatty acid biosynthesis | 1.8±0.17 | 1.6±0.26 |

| yhr007c | ERG11 | Cytochrome P450 lanosterol 14α-demethylase | Ergosterol biosynthesis | No data‡ | -1.9±0.10 |

| yjl153c | INO1 | Myo-inositol-3-phosphate synthase | PI biosynthesis | No data‡ | 151±10.7 |

| ygr170w | PSD2 | Phosphatidylserine decarboxylase 2 | PS biosynthesis | No data‡ | 1.3±0.11 |

| ygr157w | CHO2 | Phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase | PC biosynthesis | 1.8±0.51 | 1.6±0.02 |

| yjr073c | OPI3 | Methylene-fatty-acyl-phospholipid synthase | PC biosynthesis | 2.9±0.68 | 6.5±0.55 |

| ynl169c | PSD1 | Phosphatidylserine decarboxylase 1 | PS biosynthesis | No data‡ | 1.3±0.17 |

| ypr113w | PIS1 | CDP-diacylglycerol–inositol 3-phosphatidyltransferase | PI biosynthesis | No data‡ | 1.1±0.07 |

| yer026c | CHO1 | CDP-diacylglycerol serine O-phosphatidyltransferase | PS biosynthesis | 1.8±0.24 | 1.7±0.14 |

| Others | |||||

| ypl154c | PEP4 | Aspartyl protease | Vacuolar protein, catabolism | 1.8±0.14 | 1.7±0.32 |

| yor061w | CKA2 | CK2 α′ chain | G2/M and G1/S transition etc. | No data‡ | −1.2±0.12 |

| yfl031w | HAC1 | Transcription factor | Unfolded protein response | No data‡ | 5.6±0.39 |

| ylr350w | ORM2 | Strong similarity to ORM1 | Response to unfolded protein | 2.8±0.43 | Not determined |

| ycl043c | PDI1 | Protein disulfide-isomerase precursor | Protein folding | 2.2±0.17 | Not determined |

| yjl034w | KAR2 | Nuclear fusion protein | Response to unfolded protein | 1.9±0.98 | Not determined |

*Positive values represent fold up-regulation in Acb1p-depleted cells compared with wild-type cells, whereas negative values represent fold down-regulation in Acb1p-depleted cells compared with wild-type cells. Data are means±S.D. Q-RT-PCR, n≥3; microarray analysis, n=2.

†For each Q-RT-PCR analysis, RNA from three or four different cell cultures were used for cDNA synthesis and mean values were calculated. ACT1 was used as endogenous reference.

‡Data are not given because value for intensities were below that of Arabidopsis controls or because data were not present in both (dye-reversal) arrays.

Genes associated with lipid metabolism

The present microarray analysis and Q-RT-PCR analysis show that genes encoding proteins involved in fatty acid biosynthesis (ACC1, FAS1, FAS2 and OLE1) all are up-regulated in Acb1p-depleted cells compared with wild-type cells (Table 2 and see Supplementary Table S2 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/407/bj4070219add.htm). Consistent with previous findings, the gene encoding the yeast Δ9 desaturase OLE1, was found to be up-regulated approx. 4-fold in Acb1p-depleted cells cultured in YNBD medium (results not shown) and approx. 2-fold in cells cultured in YPD medium (Table 2) [4,16].

The microarray and Q-RT-PCR data also revealed that genes encoding enzymes involved in phospholipid biosynthesis (INO1, CHO1, CHO2 and OPI3) are up-regulated in Acb1p-depleted cells (Table 2). Moreover, the expression of both PSD1 and PSD2, which also encode phospholipid biosynthesis enzymes, was increased 1.3-fold in Acb1p-depleted cells compared with wild-type cells (Table 2), as observed by Q-RT-PCR. This suggests that synthesis of glycerophospholipids may be affected in cells depleted of Acb1p. In particular, the INO1 gene encoding the inositol-3-phosphate synthase (Ino1p) that catalyses synthesis of inositol-3-phosphate, the rate-limiting and committed step in the synthesis of PI (phosphatidylinositol), was strongly affected by Acb1p depletion. Although below the detection level of the microarrays, INO1 mRNA levels were detected by Q-RT-PCR and found to be up-regulated approx. 150-fold after Acb1p depletion (Table 2). INO1 mRNA and Ino1p levels were investigated further under different growth conditions.

Regulation of INO1 expression in Acb1p-depleted cells

Most of the genes involved in phospholipid synthesis, e.g. INO1, OPI3, PIS1, CHO1 and CHO2, are characterized by the presence of a cis-acting UASINO1 (inositol-sensitive upstream activating sequence), also called an ICRE (inositol/choline-responsive element), in their promoters (for a review see [28]). Transcription of UASINO1-containing genes is positively regulated by Ino2p and Ino4p, which bind to UASINO1 elements and activate transcription when cells are grown in the absence of inositol and choline. Repression occurs in the presence of high concentrations of inositol and choline and is mediated by Opi1p, which acts as a negative regulator (for a review see [29]). In the absence of inositol and choline, Opi1p is sequestered in the ER (endoplasmic reticulum) membrane by binding to PA (phosphatidic acid) and Scs2p [30]. On addition of inositol and choline, PA is quickly consumed for the synthesis of PI and PC (phosphatidylcholine), followed by translocation of Opi1p to the nucleus [30] where it represses UASINO1-dependent expression indirectly, presumably by interacting with the Ino2p transcriptional activator.

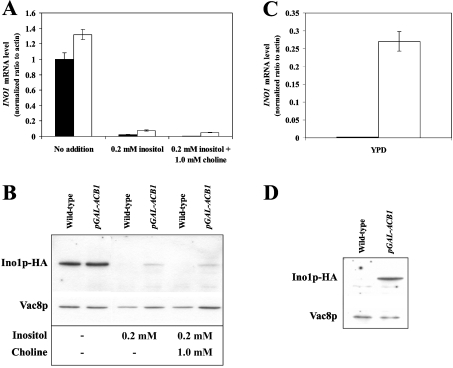

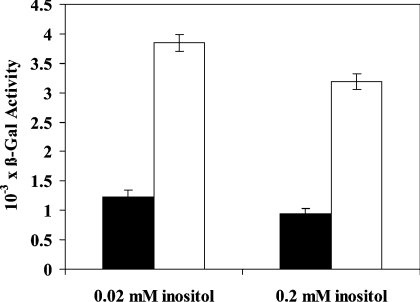

INO1 mRNA and the corresponding Ino1p protein level were both found to be significantly up-regulated in Acb1p-depleted cells in comparison with wild-type cells, when grown in both YPD and SC medium supplemented with 0.2 mM inositol (Figure 1). This suggests that full repression of INO1 mRNA and Ino1p by inositol requires the presence of Acb1p. Consistent with this, we did not observe a significant difference in UASINO1-driven β-galactosidase activity between wild-type and Acb1p-depleted cells when cultured in inositol-free medium (results not shown). In contrast, when grown in YNBD medium supplemented with either 0.02 mM inositol or 0.2 mM inositol, UASINO1-driven β-galactosidase expression was approx. 3-fold higher in Acb1p-depleted cells compared with wild-type cells (Figure 2). Up-regulation of INO1 transcription in Acb1p-depleted cells may be caused by increased UASINO1-driven transcription as a result of reduced inositol-mediated repression. This notion is supported by the fact that other genes containing UASINO1 elements in their promoter, including OPI3, CHO1 and CHO2, are also up-regulated in Acb1p-depleted cells (Table 2). In a recent microarray study, a total of 36 Ino2p and Ino4p target genes were identified [31]. On Acb1p depletion, 20 of these genes were found to be up-regulated (at least 1.5-fold), three were down-regulated (at least 1.5-fold), and 13 genes were not shown to be differently expressed when compared with wild-type cells. This indicates that inositol-mediated repression of Ino2p and Ino4p target genes at steady-state depends on Acb1p. Since Ino2p, Ino4p and Opi1p regulate transcription of UASINO1-containing genes, mRNA levels of these transcription factors were measured by Q-RT-PCR. We found that the mRNA level of INO2 and INO4 were increased approx. 2-fold in Acb1p-depleted cells on comparison with wild-type cells grown in rich medium, whereas no significant changes was observed for cells grown in minimal medium (results not shown). The mRNA level of OPI1 was increased approx. 1.3-fold in Acb1p-depleted cells compared with wild-type cells when grown in rich medium, whereas the mRNA level was decreased approx. 1.3-fold when cells were grown in minimal medium (results not shown).

Figure 1. INO1 mRNA and protein levels during different growth conditions in Acb1p-depleted cells.

Q-RT-PCR analysis of INO1 mRNA levels in wild-type (Y700, black bars) and pGAL-ACB1 (Acb1p-depleted Y700, white bars) cells grown in minimal medium (SC) supplemented with choline and/or inositol as indicated (A) or in rich medium (YPD) (C). Immunoblot analysis of protein extracts from S. cerevisiae containing Ino1p–HA. Wild-type (Y700 Ino1p–HA) and pGAL-ACB1 (Acb1p-depleted Y700 Ino1p–HA) cells were grown in SC medium supplemented with choline and/or inositol as indicated (B) or in YPD medium (D). The blots in (B) and (D) were re-probed with rabbit anti-Vac8p antibody (a gift from Professor Lois S. Weisman, Life Sciences Institute and Department of Cellular and Developmental Biology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A) (1:2000 dilution) to serve as loading control. Data in (A) and (C) are means±S.D. (n=3) and Western blots are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 2. UASINO1-driven gene expression is increased in Acb1p-depleted cells.

Wild-type (Y700, black bars) and pGAL-ACB1 (Acb1p-depleted Y700, white bars) cells were grown in YNBD medium (without inositol) or supplemented with inositol as indicated. Cells were transformed with the INO1-CYC1-lacZ plasmid and β-galactosidase activity was measured to assess the ability of UASINO1 elements to drive lacZ expression in wild-type and Acb1p-depleted cells. β-Galactosidase activity was defined as described in the Experimental section. Data are means±S.D. (n=3).

Acb1p depletion reduces inositol-mediated repression of INO1 by an Opi1p-independent regulatory mechanism

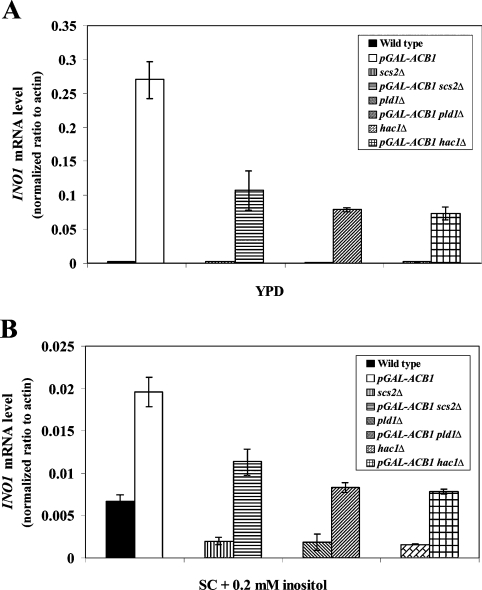

Since INO1, CHO1, CHO2 and OPI3 were identified to be up-regulated in Acb1p-depleted cells, we speculate that the transcriptional repressor Opi1p is sequestered in the ER membrane of these cells, as a result of higher levels of PA and/or Scs2p. Disruption of SCS2 reduced INO1 expression in both wild-type and Acb1p-depleted cells, but INO1 mRNA levels were still increased approx. 60-fold (Figure 3A) and approx. 5.5-fold (Figure 3B) in Acb1p-depleted cells grown in YPD medium or SC medium containing 0.2 mM inositol respectively. A similar expression pattern was observed for OPI3 on disruption of SCS2 (results not shown). Moreover, SCS2 mRNA levels were unaffected by Acb1p depletion (results not shown), and relative PA levels were unchanged or lower in Acb1p-depleted cells compared with wild-type cells (Table 3). Finally, overexpression of OPI1 did not reduce INO1 mRNA levels of Acb1p-depleted cells to that of wild-type cells (results not shown). Taken together, these observations suggest that Acb1p depletion reduces inositol-mediated repression of INO1 and other Ino2p and Ino4p target genes by an Opi1p-independent regulatory mechanism.

Figure 3. INO1 mRNA levels in wild-type and Acb1p-depleted cells with SCS2, PLD1 or HAC1 disrupted.

Q-RT-PCR analysis of INO1 mRNA levels in wild-type (Y700) and pGAL-ACB1 (Acb1p-depleted Y700) cells disrupted in SCS2, PLD1 or HAC1 genes, following growth in rich (YPD) medium (A) or minimal (SC) medium supplemented with 0.2 mM inositol (B). Data are means±S.D. (n=3).

Table 3. The relative phospholipid content of Y700 pGAL-ACB1 cells compared with Y700 cells.

The content of a given phospholipid class in Acb1p-depleted cells (Y700 pGAL-ACB1) was normalized to wild-type (Y700) levels (wild-type=100%) and calculated using the following equation: Content=Σ {% individual phospholipid species in Wt/[(Wt 12C/13C)/(Δ 12C/13C)]}, where Δ is Y700 pGAL-ACB1 and wild-type (Wt) is Y700. Data are means±S.D. (n=2).

| Phospholipid content (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | PA | PI | PG | PS | PE | PC |

| YPD | 95±7.8 | 128±15.2 | 89±18.9 | 78±2.5 | 129±7.8 | 98±15.5 |

| SC medium +0.2 mM inositol | 81±6.8 | 80±4.4 | 46±7.6 | 72±20.8 | 80±19.1 | 96±18.1 |

| SC medium without inositol | 120±22.5 | 223±0.9 | 66±8.4 | 125±18.9 | 139±23.5 | 100±15.9 |

Acb1p-depleted S. cerevisiae exhibit an Opi− phenotype, but do not accumulate PA

The Opi− phenotype has previously been associated with deregulation of the INO1 gene [32]. Therefore we tested Acb1p-depleted cells for an Opi− phenotype [32]. Growth of an inositol-dependent strain around Acb1p-depleted cells grown on synthetic inositol-free plates, shows that Acb1p depletion leads to inositol secretion (Figure 4A). Moreover, it has been shown that strains carrying deletions in CHO1, CHO2 or OPI3 have defects in PC synthesis, are unable to repress INO1 in the presence of inositol and exhibit a conditional Opi− phenotype, owing to the accumulation of PA [32,33]. Expression of INO1 and the Opi− phenotype can be normalized in these strains by the addition of exogenous choline, which alleviates PA accumulation by increasing PC synthesis via the CDP (cytidyldiphosphate)–choline pathway [28,34]. Thus if accumulation of PA causes increased INO1 expression in Acb1p-depleted cells, supplementation of both choline and inositol would be expected to repress INO1 mRNA and Ino1p levels further in both wild-type and Acb1p-depleted cells, compared with addition of inositol alone. However, addition of choline to inositol-containing medium resulted in only a minor decrease in INO1 mRNA and Ino1p levels in Acb1p-depleted cells compared with wild-type cells (Figures 1A and 1B). Hence increased INO1 expression in Acb1p-depleted cells may not be caused by the accumulation of PA as a result of reduced PC synthesis by the PE (phosphatidylethanolamine) methylation pathway. Increased phospholipase D1 (Pld1p)-mediated turnover of PC has also been reported to result in derepression of the INO1 gene [26] probably by accumulation of PA. However, in a pld1-null background, INO1 levels were still increased approx. 90-fold (Figure 3A) and approx. 4.5-fold (Figure 3B) in Acb1p-depleted cells grown in YPD medium and SC medium containing 0.2 mM inositol respectively. Increased PC turnover does not seem to cause derepression of INO1 in Acb1p-depleted cells. This is in agreement with our previous data, which showed that PC turnover is only slightly reduced in Acb1p-depleted cells, compared with wild-type cells [16]. No increase was found in the relative levels of PC and PA in Acb1p-depleted cells when compared with wild-type cells (Table 3). Taken together, these results indicate that changes in PC metabolism or accumulation of PA are not responsible for increasing INO1 mRNA and Ino1p levels in cells depleted of Acb1p.

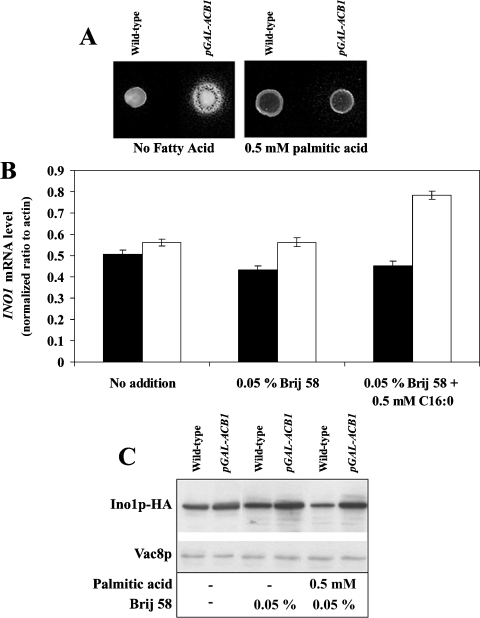

Figure 4. Acb1p-depleted cells exhibits an Opi− phenotype.

(A) Wild-type (Y700) and pGAL-ACB1 (Acb1p-depleted Y700) cells were tested for their ability to secrete inositol to the surrounding medium when supplemented with or without 0.5 mM palmitic acid. (B) Q-RT-PCR analysis of INO1 mRNA levels in wild-type (Y700, black bars) and pGAL-ACB1 (Acb1p-depleted Y700, white bars) cells grown in YNBD medium (without inositol) supplemented with or without 0.05% (v/v) Brij58 and 0.5 mM palmitic acid as indicated. (C) Immunoblot analysis of protein extracts from S. cerevisiae expressing Ino1p–HA. Wild-type (Y700 Ino1p–HA) and pGAL-ACB1 (Acb1p-depleted Y700 Ino1p–HA) cells were grown in YNBD medium (without inositol) supplemented with or without 0.05% (v/v) Brij 58 detergent and 0.5 mM palmitic acid as indicated. The blot was re-probed with an antibody against Vac8p to serve as a loading control. Data in (B) are means±S.D. (n=3) and the Western blot is representative of three independent experiments.

The mechanism causing induction of INO1 in Acb1p-depleted cells is independent of HAC1 expression

Eukaryotic cells respond to the accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER by activating a stress-response pathway known as the UPR (unfolded protein response) pathway (for a review see [35]). In S. cerevisiae, the UPR pathway may also be activated in response to inositol starvation and it is coupled to inositol biosynthesis, as cells defective in UPR activation require exogenous inositol for growth and express low levels of INO1 [36]. In yeast, it has been proposed that Hac1p negatively regulates the activity of Opi1p [37]. Interestingly, HAC1, PDI1, KAR2 and ORM2 were identified in the present study as being up-regulated in cells depleted of Acb1p (Table 2), which is indicative of induction of the UPR pathway. Disruption of HAC1 diminished INO1 mRNA levels in wild-type cells and cells depleted of Acb1p (Figure 3). However, INO1 mRNA levels were still increased approx. 40-fold (Figure 3A) and approx. 5-fold (Figure 3B) in Acb1p-depleted cells compared with wild-type cells when grown in YPD and SC medium containing 0.2 mM inositol respectively. These results clearly demonstrate that the observed reduction in inositol-mediated repression of INO1 in cells lacking Acb1p is not the result of induction of the UPR pathway. This suggestion is supported by a recent microarray study which showed that Opi1p-mediated repression of INO1 in response to inositol cannot be prevented by constitutive activation of the UPR pathway [31].

Phospholipid analysis by LC–ESI MS/MS

To examine whether the observed induction of genes encoding enzymes involved in phospholipid biosynthesis in Acb1p-depleted cells is caused by changes in the overall phospholipid content, we measured the relative levels of PC, PI, PE, PG (phosphatidylglycerol), PS (phosphatidylserine) and PA using LC–ESI–MS/MS, with 13C-labelled yeast lipids used as internal standards. Acb1p-depleted cells grown in YPD medium, exhibited an approx. 30% increase in the relative level of the major glycerolphospholipids, PI and PE, and unchanged levels of PC, PG and PA compared with wild-type cells (Table 3). However, the relative level of PS was decreased by approx. 20% in the Acb1p-depleted cells. For Acb1p-depleted cells grown in SC medium supplemented with 0.2 mM inositol, it was found that the relative levels of PA, PI, PS and PE was reduced by approx. 20%, whereas the PC level was unchanged compared with wild-type cells. In contrast, the relative PG level was decreased by approx. 50% (Table 3). These results indicate that a reduction in the relative phospholipid content is not solely responsible for the induction of phospholipid biosynthesis genes in Acb1p-depleted cells, since only the relative PS level was consistently reduced under all conditions. Therefore Acb1p may act downstream or independently of the signal produced through phospholipid metabolism to affect INO1 expression. However, it should be noted that the relative phospholipid species composition is altered in Acb1p-depleted cells compared with wild-type cells (see Supplementary Tables S3–S8 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/407/bj4070219add.htm). Acb1p depletion causes a shift from C34:1 species towards C34:2 and C32:1 or C32:2 species in the PI, PG, PS and PA classes, independently of whether cells are grown in YPD medium or SC medium supplemented with 0.2 mM inositol (see Supplementary Tables S3–S8). These results confirm that Acb1p depletion leads to changes in the relative species composition of phospholipids, as reported previously [17]. Thus it cannot be excluded that changes in the relative species composition of phospholipids in Acb1p-depleted cells results in the observed alteration in expression of genes encoding enzymes involved in phospholipid biosynthesis.

Supplementation with fatty acids or overexpression of FAS1 or ACC1 can normalize inositol-mediated repression of INO1 in Acb1p-depleted cells

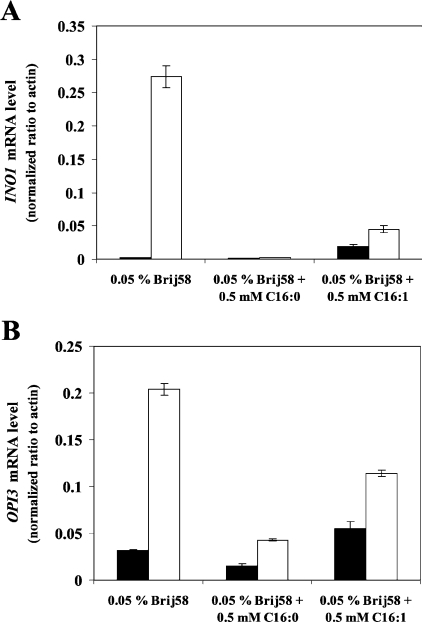

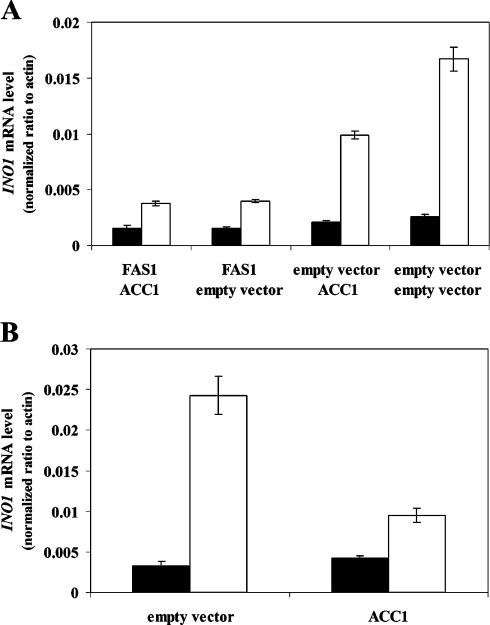

A link between fatty acid metabolism and INO1 expression has previously been reported by Shirra et al. [38], who found that inhibition of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (Acc1p) activity restored expression of INO1 in SNF1 disrupted cells. Moreover, it was shown that supplementation with palmitoleic acid (C16:1) relieved inositol auxotrophy and permitted INO1 expression in cells lacking SNF1 [38]. In addition, Gaspar et al. [39] suggested that the observed burst in PI synthesis following the addition of inositol depends on de novo fatty acid synthesis, further indicating a link between fatty acid biosynthesis and regulation of phospholipid biosynthesis. Addition of palmitic acid (C16:0) to inositol-containing medium normalized INO1 and OPI3 expression in Acb1p-depleted cells to that of wild-type cells (Figure 5). In contrast, palmitoleic acid only partly normalized INO1 and OPI3 expression in Acb1p-depleted cells to levels observed in wild-type cells (Figure 5). Notably, palmitoleic acid increased INO1 and OPI3 expression in wild-type cells (Figure 5). This shows that palmitic acid and palmitoleic acid affect inositol-mediated repression of Ino2p and Ino4p target genes differently in both wild-type and Acb1p-depleted cells. However, a signal generated from fatty acid metabolism may be involved in the regulation of inositol-mediated repression of Ino2p and Ino4p target genes. Wenz et al. [25] showed previously that FAS1, but not FAS2, increased FAS activity 2.8-fold when expressed from a high-copy plasmid. We therefore hypothesized that ectopic expression from a high-copy plasmid of FAS1 and ACC1, the rate-limiting enzyme in fatty acid biosynthesis, would increase fatty acid/acyl-CoA ester availability and thereby reduce INO1 expression in Acb1p-depleted cells. Overexpression of FAS1 reduced the ratio of INO1 mRNA levels in wild-type cells and Acb1p-depleted cells from approx. 1:6.5 to approx. 1:2.6 (Figure 6A). No further effect on INO1 expression was observed when FAS1 and ACC1 were overexpressed at the same time (Figure 6A). Notably, when ACC1 was overexpressed in cells transformed with the empty FAS1 vector, the ratio of INO1 mRNA levels in wild-type cells and Acb1p-depleted cells was only reduced from approx. 1:6.5 to approx. 1:4.7 (Figure 6A). However, ectopic expression of ACC1 from a high-copy plasmid in cells only transformed with this plasmid reduced the ratio of INO1 mRNA levels in wild-type cells and Acb1p-depleted cells from approx. 1:7.4 to approx. 1:2.2 (Figure 6B). A possible explanation for this observation is that transformation with two plasmids might perturb the copy number of each one, and therefore the level of expression of individual proteins may be affected. INO1 mRNA levels could not be reduced in Acb1p-depleted cells when FAS2 was overexpressed, further supporting the hypothesis that the observed effects are caused by an increased availability of fatty acids/acyl-CoA esters (results not shown). Together, these results show that increased availability of fatty acids/acyl-CoA esters in Acb1p-depleted cells normalizes the expression of genes involved in phospholipid biosynthesis. Thus Acb1p might facilitate removal of de novo synthesized acyl-CoA esters from the yeast FAS under normal physiological conditions, thereby making them available for further metabolism and regulatory processes.

Figure 5. Fatty acid supplementation normalizes INO1 and OPI3 expression on Acb1p depletion.

Q-RT-PCR analysis of INO1 (A) and OPI3 (B) mRNA levels in wild-type (Y700, black bars) and pGAL-ACB1 (Acb1p-depleted Y700, white bars) cells is shown. Cells were grown in rich medium (YPD) containing 0.05% (v/v) Brij 58 detergent in the presence or absence of 0.5 mM palmitic acid (C16:0) or 0.5 mM palmitoleic acid (C16:1) as indicated. Data are means±S.D. (n=3).

Figure 6. Ectopic overexpression of ACC1 and FAS1 decreases INO1 expression in Acb1p-depleted cells.

(A) Q-RT-PCR analysis of INO1 mRNA levels in wild-type (Y700, black bars) and pGAL-ACB1 (Acb1p-depleted Y700, white bars) cells transformed in pairs with combinations of empty vectors or construct to be expressed as indicated. Transformants were grown in selective medium (SC −uracil −tryptophan +0.2 mM inositol). (B) Q-RT-PCR analysis of INO1 mRNA levels in wild-type (Y700, black bars) and pGAL-ACB1 (Acb1p-depleted Y700, white bars) cells transformed with either empty vector or construct to be expressed as indicated. Transformants were grown in selective medium (SC −tryptophan +0.2 mM inositol). Data are means±S.D. (n=3).

Interestingly, the addition of 500 μM palmitic acid to inositol-free plates repressed the Opi− phenotype (Figure 4A), in accordance with the observed effect of palmitic acid on inositol uptake [16] and membrane abnormalities (S. Feddersen, J. Knudsen and N. J. Færgeman, unpublished work) in Acb1p-depleted cells. However, palmitic acid was unable to reduce the high INO1 mRNA and Ino1p levels of both wild-type and Acb1p-depleted cells cultured in inositol-free medium (Figures 4B and 4C). This implies that high INO1 expression is not necessarily associated with the Opi− phenotype.

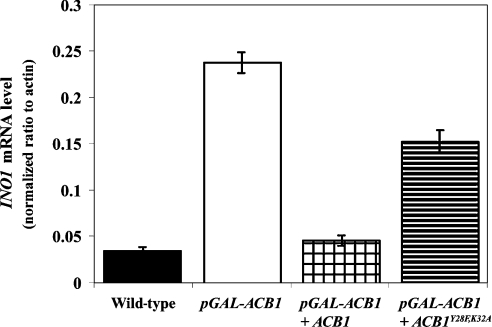

The in vivo function of Acb1p depends on ligand binding

Depletion of Acb1p in yeast results in slow growth and aberrant organelle morphology, including fragmented vacuoles, multi-layered plasma membranes and the accumulation of vesicles of variable sizes [16,17]. Ectopic expression of Acb1p in Acb1p-depleted cells normalizes vacuole morphology (S. Feddersen, J. Knudsen and N. J. Færgeman, unpublished work) and INO1 mRNA levels (Figure 7), whereas expression of Acb1pY28F/K32A, which exhibited a 1000-fold reduced affinity for acyl-CoA esters compared with wild-type Acb1p [40], was unable to restore INO1 mRNA levels (Figure 7) and vacuole morphology (S. Feddersen, J. Knudsen and N. J. Færgeman, unpublished work). The minor effect of Acb1pY28F/K32A on INO1 expression in Acb1p-depleted cells is likely to be a result of the protein being overexpressed and binding acyl-CoA esters with very low affinity. Ectopic expression of rat L-FABP, which binds acyl-CoA esters with a Kd of 14–1000 nM [41,42] in Acb1p-depleted cells was also unable to normalize the INO1 mRNA level (results not shown). This demonstrates that the function of Acb1p is closely linked to its ability to bind acyl-CoA esters with high affinity and supports the hypothesis of Acb1p playing a role in acyl-CoA trafficking.

Figure 7. Acb1p affects gene expression in an acyl-CoA ester-dependent manner.

Q-RT-PCR analysis of INO1 mRNA levels in wild-type (Y700), pGAL-ACB1 (Acb1p-depleted Y700), pGAL-ACB1+ACB1 (Acb1p-depleted Y700 complemented with ACB1) and pGAL-ACB1+ACB1Y28F/K32A (Acb1p-depleted Y700 complemented with mutant acb1) cells cultured in SC medium supplemented with 0.2 mM inositol. Data are means±S.D. (n=3).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have identified transcriptional changes in response to Acb1p depletion in genes encoding proteins which are involved in fatty acid and phospholipid synthesis, glycolysis, stress response, glycerol metabolism and ion transport and uptake (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2). Depletion of Acb1p was shown to increase transcription of INO1, CHO1, CHO2 and OPI3, all of which encode proteins required for phospholipid biosynthesis. A common feature of all of these genes is the presence of UASINO1 elements in their promoter regions (for a review see [28]). Regulation via UASINO1 elements involves the transcriptional activators Ino2p and Ino4p, and the transcriptional repressor Opi1p [30]. Nuclear localization of Opi1p is regulated by PA and Scs2p, which bind and detain Opi1p to the ER membrane. We show that the observed reduction in inositol-mediated repression of UASINO1-driven transcription in Acb1p-depleted cells is not caused by altered OPI1 levels or changes in PA and SCS2 levels. Moreover, INO2 and INO4 mRNA levels were not significantly altered in Acb1p-depleted cells grown in minimal medium compared with wild-type cells (results not shown). The approx. 3-fold increase observed in INO1 mRNA levels of Acb1p-depleted cells grown in minimal medium (Figure 3B) therefore may not be caused by increased levels of these transcriptional activators. Furthermore, Ino2p and Ino4p bind constitutively to the INO1 promoter, and it has been suggested that occupancy of the INO1 promoter by Ino2p and/or Ino4p is insufficient for its activation [37]. Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the reduction in inositol-mediated repression of Ino2p and Ino4p target genes in Acb1p-depleted cells occurs by an Ino2p, Ino4p and Opi1p-independent mechanism. However, it cannot be excluded that the Acb1p–acyl-CoA ester complex regulates the activity of Ino2p, Ino4p and Opi1p, either directly or indirectly. A possible regulatory mechanism is that Acb1p depletion alters Opi1p phosphorylation, which has been shown to affect its regulator activity [43].

Activation of the UPR pathway has previously been linked to increased phospholipid biosynthesis in yeast [37]. However, we did not find any connection between induction of the UPR pathway and increased expression of Ino2p and Ino4p target genes in Acb1p-depleted cells. Moreover, HAC1 disruption reduced the expression of OPI3 approx. 2-fold in Acb1p-depleted cells grown in YPD medium, whereas OPI3 expression in wild-type cells was unaffected by HAC1 disruption (results not shown). The absence of an effect of HAC1 disruption on OPI3 expression in wild-type cells confirms that the UPR pathway does not seem to be directly involved in transcriptional regulation of Ino2p and Ino4p target genes, as was recently suggested [31].

A large body of evidence suggests that Acb1p functions as an acyl-CoA ester transporter and pool former. We investigated the possibility that the altered expression of genes encoding enzymes involved in phospholipid synthesis, including INO1, in Acb1p-depleted yeast is the result of an absence of fatty acid metabolites. Supplementation of exogenous palmitic acid to Acb1p-depleted cells normalized INO1 and OPI3 mRNA levels to those of wild-type cells (Figure 5), in contrast with palmitoleic acid, which was found to partially normalize INO1 and OPI3 levels in Acb1p-depleted cells compared with wild-type cells (Figure 5). The difference in the effect of palmitic acid and palmitoleic acid may be a result of palmitic acid having additional effects on Acb1p-depleted cells.

Supplementation of palmitic acid to Acb1p-depleted cells partly restores inositol uptake [16] and reduced inositol secretion (Figure 4A). This may suggest that the reduction in inositol-mediated repression of Ino2p and Ino4p target genes, including INO1, in Acb1p-depleted cells, is simply a cellular response to low intracellular inositol levels. However, this is not likely to be the case since Acb1p-depleted cells, although unable to completely normalize INO1 levels on addition of inositol, do respond to exogenous inositol by repressing INO1 transcription (Figure 1A). Disruption of SCS2, which has previously been shown to reduce INO1 expression in response to inositol depletion [44], did not normalize INO1 expression in Acb1p-depleted cells (Figure 3). This further supports the hypothesis that INO1 deregulation in Acb1p-depleted cells is caused by means other than a lack of inositol. The steady-state expression of GPD1 and TDH1, which is only slightly affected by inositol [45], is dramatically increased in Acb1p-depleted cells (Table 2), suggesting that at least part of the transcriptional response accompanying Acb1p depletion is inositol-independent.

Overall, the above observations present the possibility that reduced inositol-mediated repression of Ino2p and Ino4p target genes in Acb1p-depleted cells is the result of decreased availability of fatty acids and/or acyl-CoA esters. This is strongly supported by the result that ectopic overexpression of FAS1 and ACC1 reduced ratios of INO1 mRNA levels in wild-type cells and Acb1p-depleted cells from approx. 1:6.5 and 1:7.4 to approx. 1:2.6 and 1:2.2 respectively (Figure 6). Notably, overexpression in Acb1p-depleted cells of FAS2, which is unable to enhance FAS activity [25], did not reduce INO1 mRNA levels (results not shown). This suggests that the Acb1p-mediated removal of de novo synthesized acyl-CoA esters from the yeast FAS [16] can be overcome by increasing the availability of fatty acids and/or acyl-CoA esters though enhancement of de novo fatty acid biosynthesis or supplementation with fatty acids (Figures 5 and 6). These results strongly support the hypothesis that the altered availability of fatty acids and/or fatty acid derivatives may be involved in the mechanism by which Acb1p depletion alters inositol-mediated repression of Ino2p and Ino4p target genes.

In addition to affecting the expression of phospholipid biosynthesis genes, Acb1p depletion also increased the expression of fatty acid synthetic genes, including ACC1, FAS1, FAS2 and OLE1 (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S2). This indicates that the expression of these genes is also regulated by the availability of specific acyl-CoA esters, made available by Acb1p–acyl-CoA ester complexes. We have shown previously that depletion of Acb1p in the temperature-sensitive mutant of ACC1, mtr7-1, results in lethality at the permissive temperature [16], supporting the notion that Acb1p affects the availability of acyl-CoA esters.

The acyl species composition of phospholipids is altered on Acb1p depletion (Supplementary Tables S3–S8). Thus it cannot be ruled out that these alterations can affect the expression of Ino2p and Ino4p target genes. One possible model, consistent with our results, is that Acb1p recruits LCACoA esters to phospholipid-remodelling enzymes, thereby affecting the acyl species composition of phospholipids, which then affects the expression of Ino2p and Ino4p target genes.

Several studies have shown that fatty acids and fatty acid derivatives affect gene expression directly in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes [46,47]. A number of these studies suggest that the active species is acyl-CoA ester. In Escherichia coli, fatty acid synthesis and degradation is transcriptionally co-ordinated by the acyl-CoA ester-regulated transcription factor, FadR (for a review see [46]). Eukaryotic PPARs (peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors) are activated by fatty acids and induce transcription of multiple genes involved in lipid metabolism [47], whereas LCACoA esters have been reported to antagonize this effect [48]. Immunogold EM (electron microscopy) has shown that ACBP/Acb1p is found in the nucleus of a number of mammalian [49,50] and yeast cells (S. Feddersen, J. Knudsen and N. J. Færgeman, unpublished work). The Acb1p–acyl-CoA complex may therefore modulate gene expression by donating acyl-CoA esters to gene regulatory components in the nucleus. Such a transport function is compatible with the recent suggestion implying that ACBP and HNF-4α (hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α) interact, and ACBP stimulates HNF-4α-mediated transactivation of HNF-4α target genes in hepatocytes [50].

In conclusion, we suggest that fatty acid derivatives are involved in the regulation of Ino2p and Ino4p target genes and that increased expression of these target genes in Acb1p-depleted cells is caused by a decrease in the availability of acyl-CoA esters, as a result of the absence of Acb1p.

Online data

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Danish Natural Science Council and Professor Henning Beck-Nielsen (Department of Medical Endocrinology, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark). We thank Hans Kristian Hannibal-Bach and Connie Gram for excellent technical assistance. We thank Tatjana Albrektsen (Novo-Nordisk A/S, Bagsværd, Denmark) for assistance with microarray experiments and helpful discussions.

References

- 1.Baumgartner U., Hamilton B., Piskacek M., Ruis H., Rottensteiner H. Functional analysis of the Zn2Cys6 transcription factors Oaf1p and Pip2p. Different roles in fatty acid induction of β-oxidation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:22208–22216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang S., Skalsky Y., Garfinkel D. J. MGA2 or SPT23 is required for transcription of the Δ9 fatty acid desaturase gene, OLE1, and nuclear membrane integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1999;151:473–483. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.2.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamiryo T., Parthasarathy S., Numa S. Evidence that acyl coenzyme A synthetase activity is required for repression of yeast acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase by exogenous fatty acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1976;73:386–390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.2.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi J. Y., Martin C. E. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae FAT1 gene encodes an acyl-CoA synthetase that is required for maintenance of very long chain fatty acid levels. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:4671–4683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faergeman N. J., Black P. N., Zhao X. D., Knudsen J., DiRusso C. C. The Acyl-CoA synthetases encoded within FAA1 and FAA4 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae function as components of the fatty acid transport system linking import, activation, and intracellular utilization. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:37051–37059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100884200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin G. G., Huang H., Atshaves B. P., Binas B., Schroeder F. Ablation of the liver fatty acid binding protein gene decreases fatty acyl CoA binding capacity and alters fatty acyl CoA pool distribution in mouse liver. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11520–11532. doi: 10.1021/bi0346749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seedorf U., Raabe M., Ellinghaus P., Kannenberg F., Fobker M., Engel T., Denis S., Wouters F., Wirtz K. W., Wanders R. J., et al. Defective peroxisomal catabolism of branched fatty acyl coenzyme A in mice lacking the sterol carrier protein-2/sterol carrier protein-x gene function. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1189–1201. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.8.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurlandzka A., Rytka J., Gromadka R., Murawski M. A new essential gene located on Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome IX. Yeast. 1995;11:885–890. doi: 10.1002/yea.320110910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tahotna D., Hapala I., Zinser E., Flekl W., Paltauf F., Daum G. Two yeast peroxisomal proteins crossreact with an antiserum against human sterol carrier protein 2 (SCP-2) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1148:173–176. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90175-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faergeman N. J., Knudsen J. Role of long-chain fatty acyl-CoA esters in the regulation of metabolism and in cell signalling. Biochem. J. 1997;323:1–12. doi: 10.1042/bj3230001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burton M., Rose T. M., Faergeman N. J., Knudsen J. Evolution of the acyl-CoA binding protein (ACBP) Biochem. J. 2005;392:299–307. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasmussen J. T., Rosendal J., Knudsen J. Interaction of acyl-CoA binding protein (ACBP) on processes for which acyl-CoA is a substrate, product or inhibitor. Biochem. J. 1993;292:907–913. doi: 10.1042/bj2920907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasmussen J. T., Faergeman N. J., Kristiansen K., Knudsen J. Acyl-CoA-binding protein (ACBP) can mediate intermembrane acyl-CoA transport and donate acyl-CoA for β-oxidation and glycerolipid synthesis. Biochem. J. 1994;299:165–170. doi: 10.1042/bj2990165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knudsen J., Faergeman N. J., Skott H., Hummel R., Borsting C., Rose T. M., Andersen J. S., Hojrup P., Roepstorff P., Kristiansen K. Yeast acyl-CoA-binding protein: acyl-CoA-binding affinity and effect on intracellular acyl-CoA pool size. Biochem. J. 1994;302:479–485. doi: 10.1042/bj3020479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandrup S., Jepsen R., Skott H., Rosendal J., Hojrup P., Kristiansen K., Knudsen J. Effect of heterologous expression of acyl-CoA-binding protein on acyl-CoA level and composition in yeast. Biochem. J. 1993;290:369–374. doi: 10.1042/bj2900369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaigg B., Neergaard T. B., Schneiter R., Hansen J. K., Faergeman N. J., Jensen N. A., Andersen J. R., Friis J., Sandhoff R., Schroder H. D., Knudsen J. Depletion of acyl-coenzyme A-binding protein affects sphingolipid synthesis and causes vesicle accumulation and membrane defects in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:1147–1160. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.4.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faergeman N. J., Feddersen S., Christiansen J. K., Larsen M. K., Schneiter R., Ungermann C., Mutenda K., Roepstorff P., Knudsen J. Acyl-CoA-binding protein, Acb1p, is required for normal vacuole function and ceramide synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. J. 2004;380:907–918. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Longtine M. S., McKenzie A., III, Demarini D. J., Shah N. G., Wach A., Brachat A., Philippsen P., Pringle J. R. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherman F. Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:3–21. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94004-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sambrook J., Fritsch E. F., Maniatis T. 2nd edn. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopes J. M., Hirsch J. P., Chorgo P. A., Schulze K. L., Henry S. A. Analysis of sequences in the INO1 promoter that are involved in its regulation by phospholipid precursors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1687–1693. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.7.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guarente L. Yeast promoters and lacZ fusions designed to study expression of cloned genes in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:181–191. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furukawa K., Yamada T., Mizoguchi H., Hara S. Increased ethyl caproate production by inositol limitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2003;95:448–454. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(03)80043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wenz P., Schwank S., Hoja U., Schuller H. J. A downstream regulatory element located within the coding sequence mediates autoregulated expression of the yeast fatty acid synthase gene FAS2 by the FAS1 gene product. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4625–4632. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patton-Vogt J. L., Griac P., Sreenivas A., Bruno V., Dowd S., Swede M. J., Henry S. A. Role of the yeast phosphatidylinositol/phosphatidylcholine transfer protein (Sec14p) in phosphatidylcholine turnover and INO1 regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:20873–20883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanson B. A., Lester R. L. The extraction of inositol-containing phospholipids and phosphatidylcholine from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Neurospora crassa. J. Lipid Res. 1980;21:309–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henry S. A., Patton-Vogt J. L. Genetic regulation of phospholipid metabolism: yeast as a model eukaryote. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 1998;61:133–179. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60826-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carman G. M., Kersting M. C. Phospholipid synthesis in yeast: regulation by phosphorylation. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004;82:62–70. doi: 10.1139/o03-064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loewen C. J., Gaspar M. L., Jesch S. A., Delon C., Ktistakis N. T., Henry S. A., Levine T. P. Phospholipid metabolism regulated by a transcription factor sensing phosphatidic acid. Science. 2004;304:1644–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1096083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jesch S. A., Liu P., Zhao X., Wells M. T., Henry S. A. Multiple endoplasmic reticulum-to-nucleus signaling pathways coordinate phospholipid metabolism with gene expression by distinct mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:24070–24083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenberg M. L., Reiner B., Henry S. A. Regulatory mutations of inositol biosynthesis in yeast: isolation of inositol-excreting mutants. Genetics. 1982;100:19–33. doi: 10.1093/genetics/100.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirsch J. P., Henry S. A. Expression of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae inositol-1-phosphate synthase (INO1) gene is regulated by factors that affect phospholipid synthesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 1986;6:3320–3328. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.10.3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griac P., Swede M. J., Henry S. A. The role of phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in the regulation of the INO1 gene of yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:25692–25698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mori K. Tripartite management of unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell. 2000;101:451–454. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cox J. S., Shamu C. E., Walter P. Transcriptional induction of genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum resident proteins requires a transmembrane protein kinase. Cell. 1993;73:1197–1206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90648-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brickner J. H., Walter P. Gene recruitment of the activated INO1 locus to the nuclear membrane. PLoS. Biol. 2004;2:e342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shirra M. K., Patton-Vogt J., Ulrich A., Liuta-Tehlivets O., Kohlwein S. D., Henry S. A., Arndt K. M. Inhibition of acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase activity restores expression of the INO1 gene in a snf1 mutant strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;21:5710–5722. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.17.5710-5722.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaspar M. L., Aregullin M. A., Jesch S. A., Henry S. A. Inositol induces a profound alteration in the pattern and rate of synthesis and turnover of membrane lipids in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:22773–22785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kragelund B. B., Poulsen K., Andersen K. V., Baldursson T., Kroll J. B., Neergard T. B., Jepsen J., Roepstorff P., Kristiansen K., Poulsen F. M., Knudsen J. Conserved residues and their role in the structure, function, and stability of acyl-coenzyme A binding protein. Biochemistry. 1999;38:2386–2394. doi: 10.1021/bi982427c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frolov A., Cho T. H., Murphy E. J., Schroeder F. Isoforms of rat liver fatty acid binding protein differ in structure and affinity for fatty acids and fatty acyl CoAs. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6545–6555. doi: 10.1021/bi970205t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rolf B., Oudenampsen-Kruger E., Borchers T., Faergeman N. J., Knudsen J., Lezius A., Spener F. Analysis of the ligand binding properties of recombinant bovine liver-type fatty acid binding protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1995;1259:245–253. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(95)00170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sreenivas A., Villa-Garcia M. J., Henry S. A., Carman G. M. Phosphorylation of the yeast phospholipid synthesis regulatory protein Opi1p by protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:29915–29923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kagiwada S., Zen R. Role of the yeast VAP homolog, Scs2p, in INO1 expression and phospholipid metabolism. J. Biochem. 2003;133:515–522. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jesch S. A., Zhao X., Wells M. T., Henry S. A. Genome-wide analysis reveals inositol, not choline, as the major effector of Ino2p-Ino4p and unfolded protein response target gene expression in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:9106–9118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411770200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Black P. N., Faergeman N. J., DiRusso C. C. Long-chain acyl-CoA-dependent regulation of gene expression in bacteria, yeast and mammals. J. Nutr. 2000;130:305S–309S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.305S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kliewer S. A., Sundseth S. S., Jones S. A., Brown P. J., Wisely G. B., Koble C. S., Devchand P., Wahli W., Willson T. M., Lenhard J. M., Lehmann J. M. Fatty acids and eicosanoids regulate gene expression through direct interactions with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors α and γ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:4318–4323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murakami K., Ide T., Nakazawa T., Okazaki T., Mochizuki T., Kadowaki T. Fatty-acyl-CoA thioesters inhibit recruitment of steroid receptor co-activator 1 to α and γ isoforms of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptors by competing with agonists. Biochem. J. 2001;353:231–238. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elholm M., Garras A., Neve S., Tornehave D., Lund T. B., Skorve J., Flatmark T., Kristiansen K., Berge R. K. Long-chain acyl-CoA esters and acyl-CoA binding protein are present in the nucleus of rat liver cells. J. Lipid Res. 2000;41:538–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petrescu A. D., Payne H. R., Boedecker A., Chao H., Hertz R., Bar-Tana J., Schroeder F., Kier A. B. Physical and functional interaction of acyl-CoA-binding protein with hepatocyte nuclear factor-4α. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:51813–51824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303858200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.