Abstract

In the present study, we demonstrate that AC5 (type V adenylate cyclase) interacts with Ric8a through directly interacting at its N-terminus. Ric8a was shown to be a GEF (guanine nucleotide exchange factor) for several α subunits of heterotrimeric GTP binding proteins (Gα proteins) in vitro. Selective Gα targets of Ric8a have not yet been revealed in vivo. An interaction between AC5 and Ric8a was verified by pull-down assays, co-immunoprecipitation analyses, and co-localization in the brain. Expression of Ric8a selectively suppressed AC5 activity. Treating cells with pertussis toxin or expressing a dominant negative Gαi mutant abolished the suppressive effect of Ric8a, suggesting that interaction between the N-terminus of AC5 and a GEF (Ric8a) provides a novel pathway to fine-tune AC5 activity via a Gαi-mediated pathway.

Keywords: cAMP, guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), Ric8a, type V adenylate cyclase (AC5)

Abbreviations: AC, adenylate cyclase; AC5, type V AC; C-SOM, cyclo-somatostatin; GEF, guanine nucleotide exchange factor; GST, glutathione S-transferase; HA, haemagglutinin; HEK-293T cells, human embryonic kidney 293 cells expressing the large T-antigen of SV40 (simian virus 40); PTX, pertussis toxin; RGS2, regulator of G-protein signalling 2; SST, somatostatin

INTRODUCTION

ACs (adenylate cyclases) are enzymes that convert ATP to cAMP upon extracellular stimuli. To date, nine different transmembrane ACs and one soluble AC have been identified, each with its own unique regulatory properties and tissue distribution. AC5 (type Vadenylate cyclase) is highly expressed in the striatum of the brain and heart [1]. Low levels of AC5 have also been detected in other tissues, including the prostate, ovaries, small intestine, colon, lungs, liver, kidneys and testes. Its activity is sensitive to regulation by different pathways (including those mediated by Gαs and protein kinase C). In addition, AC5 can be inhibited by many regulators including Gαi, Gαz, RGS2 (regulator of G-protein signalling 2), P-site inhibitors, protein kinase A-mediated phosphorylation, capacitate calcium entry and PAM (protein associated with Myc) [2–5]. Binding of several AC5 regulators has also been identified. For example, Gαs proteins bind to the C2 domain [6], whereas Gαi and RGS2 both bind to the C1 domain at two independent sites [3].

The N-terminus of each individual AC usually has a unique amino acid sequence that is important for isoform-specific regulation [7–10]. Several interacting proteins [e.g. snapin and PP2A (protein phosphatase 2A)] which bind the N-terminus of different ACs have been reported [10,11], suggesting that the N-terminus might function as a scaffold which selectively mediates the cross-talk between the cAMP signalling and other machinery. AC5 contains a very long N-terminus (242 amino acids) with no known function. In the present study, we report the identification of Ric8a as the first binding partner of the N-terminus of AC5. Ric8a (also known as synembryn) has been demonstrated previously to be associated with many Gα proteins in mammalian cells, including Gαs, Gαq, Gαo, Gαi and Gαi3 [12,13]. Based on its ability to stabilize the non-guanine-nucleotide-binding form of Gα proteins in vitro, Ric8a is thought to serve as a receptor-independent GEF (guanine nucleotide exchange factor) for several Gα proteins [12]. We show herein that by binding to the N-terminus of AC5, Ric8a suppresses the activity of AC5 via a Gαi-dependent pathway.

METHODS

Plasmid constructions

The cDNA of rat AC5 (accession no. M96159) was kindly provided by Dr Richard T. Premont (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, U.S.A.). A DNA fragment encoding the N-terminus of rat AC5 (amino acids 1–215; AC5N1–215) was amplified by PCR using the following primers: 5′-GGAATTCATGTCCGGCTCCAAAAGCGTGAGC-3′ and 5′-CGGGATCCCGTTACTGCAGCAAGGCCAGGCA-3′. The resulting DNA fragment was subcloned into pET-11D (Novagen, GE Healthcare, Pharmacia Co., Uppsala, Sweden) for expression in prokaryotic cells. The cDNA fragment encoding HA (haemagglutinin)-tagged Ric8a was subcloned into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for expression in eukaryotic cells, and into pET-11D or pGEX-2T (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to produce the recombinant His6–Ric8a or GST (glutathione S-transferase)–Ric8a protein respectively. All resultant plasmids were analysed by nucleotide sequencing to verify the inserts.

Cell culture and transfection

HEK-293T cells [human embryonic kidney 293 cells expressing the large T-antigen of SV40 (simian virus 40)] were cultured in DMEM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium) plus 10% foetal bovine serum, 2 mM of L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen GibcoBRL, Carlsbad, CA, U.S.A.) at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen) based on the manufacturer's protocol. Primary striatal neurons were prepared from Sprague–Dawley rat brains at embryonic day 18 as described previously [10] and grown in Neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen).

Antibody preparation

Recombinant His6–AC5N1–215 or His6–Ric8a proteins were obtained from Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) transformed with pET11D-AC5N1–215 or pET151D-Ric8a respectively. The desired fusion proteins were then purified by Ni-coupled beads (Novagen, GE Healthcare) following the manufacturer's protocol, and used to immunize rabbits by a splenic injection. The resultant antibodies were respectively designated anti-AC5N and anti-Ric8a. Biotinylation of anti-AC5N was performed as described previously [10]. Affinity purification of the anti-Ric8a antiserum was conducted using a Ric8a-conjugated CNBr-column. In brief, approx. 10 mg of recombinant GST or GST–Ric8a was conjugated with CNBr beads (Pierce, Rockford, IL, U.S.A.) following the manufacturer's protocol. Purification of the anti-Ric8a antibody was carried out by first removing the antibodies recognizing GST by passing the antiserum through a CNBr–GST column, followed by a second column packed with the CNBr–GST–Ric8a beads.

SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis

Protein concentrations were determined by using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay Dye Reagent Concentrate (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA, U.S.A.). Equal amounts of sample were separated by SDS/PAGE using 8–15% polyacrylamide gels, followed by Western blot analyses as described previously [14]. Typically, dilutions of 1:10000 and 1:500 were used for anti-AC5N and anti-Ric8a respectively.

In vitro binding

Recombinant GST-fusion proteins were purified using glutathione–Sepharose beads (Promega) following the manufacturer's protocol. For brain tissues, pregnant and 8-week-old Sprague–Dawley rats were obtained from the National Laboratory Animal Center (Taipei, Taiwan). Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines (Taiwan) under protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Academia Sinica (Taipei, Taiwan). Brain tissues were harvested to prepare total lysates and P1 membrane fractions as described elsewhere [15]. A GST pull-down assay was conducted by incubating 20 μg of GST or GST–Ric8a with glutathione–Sepharose 4B beads in the presence of 1 ml of harvest buffer [10 mM Hepes, pH 7.3, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM benzamidine, 5 mM EDTA, 1× Complete™ protease cocktail (Roche), 1 μM leupeptin, 10 μM PMSF and 0.5% Triton X-100] at 4 °C for 1 h on a rolling wheel. After extensive washing using ice-cold harvest buffer, the protein–bead complexes were then incubated with the soluble P1 membrane fraction (250 μg) collected from the rat striatum or 30 μg of the purified recombinant N-terminus of AC5 (AC5N1–215) at 4 °C for 1 h, washed five times with ice-cold harvest buffer, and resolved by SDS/PAGE and Western blot analysis.

Co-immunoprecipitation

HEK-293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmid(s) for 72 h. Cells were lysed with 1 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer [20 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 140 mM NaCl, 1× Complete™ protease cocktail, 1 μM leupeptin and 10 μM PMSF] as described previously [16]. Briefly, the cell lysate (1 mg) was incubated with an anti-c-Myc antibody (9E10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.) for 1 h at 4 °C on a rolling wheel. The complexes were then mixed with 50 μl of Protein A beads (Sigma–Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, U.S.A.) and incubated for 1 h at 4 °C on a rolling wheel. After extensive washing with ice-cold lysis buffer, the resulting immunoprecipitation complexes were resolved on 20 μl of 4× sampling buffer, and analysed by SDS/PAGE and Western blot assay.

For the co-immunoprecipitation of AC5 and Ric8a from the striatum, membrane lysates (150 μg per reaction) were prepared as described previously [17], and immunoprecipitated using the anti-Ric8a antiserum (10 μl) as detailed in [18]. Immunocomplexes were captured using an immunoprecipitation matrix (ExactaCruz F, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) following the manufacturer's protocol, washed extensively using an immunoprecipitation buffer [150 mM NaCl, 1% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 1× Complete™ protease cocktail (Roche), 1 μM leupeptin and 10 μM PMSF], and analysed by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting.

AC activity and cAMP assay

AC activity was assayed as described previously [19]. AC5 activity was determined as the difference between the cyclase activities measured from the membrane fractions collected from HEK-293T cells transfected with AC5 cDNA and those of an empty vector. The intracellular cAMP content was determined as described before [19] with slight modification. Cells were washed twice with Ca2+-free Locke's solution (150 mM NaCl, 5.6 mM KCl, 5 mM glucose, 1 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) containing 0.5 mM IBMX (isobutylmethylxanthine) and were then treated with the indicated reagent(s) for 20 min at room temperature (25 °C). The cAMP content was assayed using the 125I-cAMP assay system (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, U.K.). The results are presented as means±S.E.M. for at least three independent experiments.

Immunocytochemistry

Animal experiments were performed under protocols approved by the Academia Sinica Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee, Taiwan. In brief, male B6 mice were perfused with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Their brains were carefully removed and post-fixed. Double immunostaining of AC5 and Ric8a was conducted using an affinity-purified anti-Ric8a antibody (10 μg/ml) and biotinylated anti-AC5N antiserum (8.3 μg/ml) as detailed elsewhere [10]. For double label immunostaining of primary neurons, cells were fixed at 8 to 9 days in vitro in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde/4% (w/v) sucrose in PBS for 30 min. CellTracker™ CM-DiI was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, U.S.A.). For double immunostaining of AC5 and DiI, cells were first stained with DiI (4 μg/ml) for 5 min at 37 °C, followed by a 15 min incubation at 4 °C, and then they were fixed and stained with the biotinylated anti-AC5N antibody as described above. Patterns of double immunostaining were analysed with the aid of a laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM510, Carl Zeiss, Germany).

RESULTS

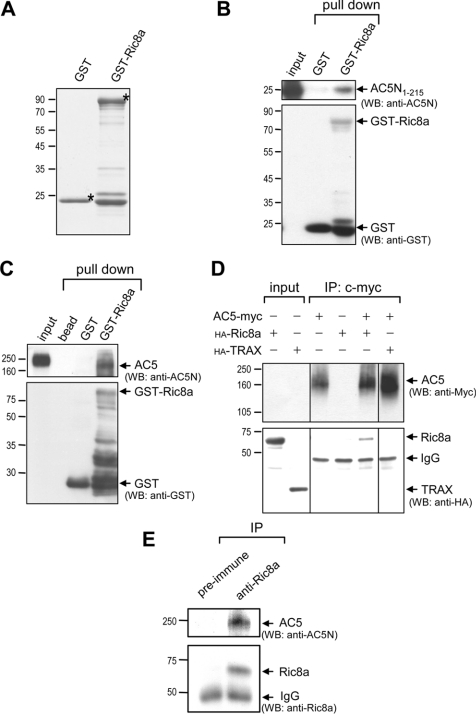

AC5 contains the longest N-terminus (amino acids 1–242) among all membrane-bound ACs. To search for novel molecules that interact specifically with the N-terminus of AC5, we used the most N-terminal fragment comprising amino acids 1–215 (designated AC5N1–215) as bait to screen a mouse brain cDNA library using the yeast 2-hybrid technique. Out of 2×106 clones screened, five candidate proteins were identified (results not shown). Among them, Ric8a is of the greatest interest due to its previous association with Gα proteins [12]. Interactions between AC5 and Ric8a were first verified by the GST-pull-down assays. Recombinant Ric8a fused to GST was prepared (Figure 1A). Note that some smaller proteins existed in the GST fusion protein preparations. These proteins appeared to be degradation products because they could be recognized by anti-GST antiserum (Figure 1B). Most importantly, recombinant GST–Ric8a (but not GST) was able to pull-down the N-terminus of AC5 (AC5N1–215; Figure 1B). We next examined whether recombinant GST–Ric8a interacted with full-length AC5 harvested from the rat striatum. Although incubation with striatal lysate caused slight degradation of GST–Ric8a, the remaining GST–Ric8a was able to pull-down the full-length AC5 protein, whereas GST alone did not (Figure 1C). Interactions between AC5 and Ric8a were further confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation of AC5–myc and HA–Ric8a expressed in HEK-293T cells, while no interaction was detected between AC5 and an irrelevant protein, TRAX (translin-associated protein X; Figure 1D) [18]. Most importantly, immunoprecipitation of endogenous Ric8a of the striatum successfully pulled-down striatal AC5 (Figure 1E), strengthening our hypothesis that the interaction between AC5 and Ric8a occurs in vivo and is likely to be physiologically important.

Figure 1. Ric8a interacts with AC5 in vitro.

(A) Purified recombinant GST fusion proteins (2 μg) were resolved by SDS/PAGE (15% gels) and visualized by staining with Coomassie Blue. Asterisks (*) indicate the corresponding recombinant protein of the correct size. The purified recombinant GST fusion protein (20 μg) was incubated with purified AC5N1–215 (15 μg) (B) or the soluble striatal membrane fractions (250 μg) (C) for 60 min at 4 °C to allow complex formation. The bound proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE (10–12% gels), followed by Western blot analyses. GST–Ric8a, but not by GST, effectively pulled-down AC5N1–215 (B) and AC5 harvested from the rat striatum (C). (D) HEK-293T cells were harvested 48 h after transfection with the indicated cDNAs for immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot analyses using the indicated antibodies. (E) Immunoprecipitation of endogenous Ric8a using the anti-Ric8a antibody from the striatum successfully pulled-down striatal AC5 detected using the anti-AC5N antibody. TRAX, translin-associated protein X.

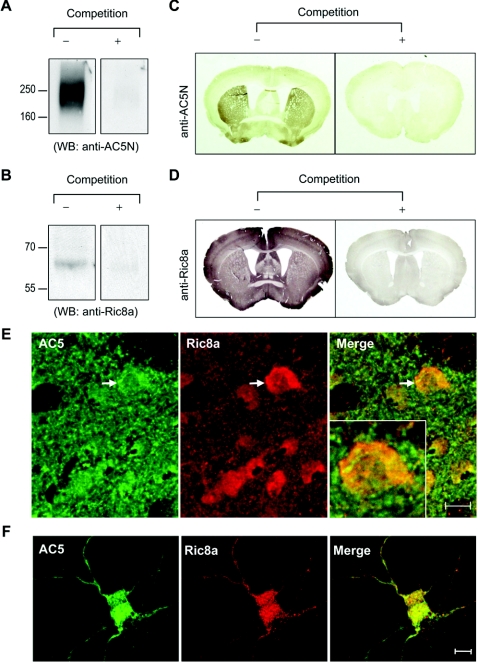

The interaction between AC5 and Ric8a was further supported by co-localization of these two molecules as demonstrated by immunocytochemical staining. Using recombinant AC5N1–215 as the antigen, we prepared a polyclonal anti-AC5 antibody (designated anti-AC5N; Figure 2A). The anti-Ric8a antibody was raised using recombinant His6–Ric8a proteins (Figure 2B). By Western blot analyses, both antibodies recognized specific bands of the correct sizes, which disappeared with an excess amount of antigen. Regional expression profiles of AC5 and Ric8a in the brain were revealed by immunohistochemical staining using these two antibodies. Again, the addition of excess antigen abrogated the corresponding immunoreactivity (Figures 2C and 2D). Consistent with an earlier report using in situ hybridization [20], AC5 was found to be highly enriched in the striatum. The expression patterns of AC5 detected using our anti-AC5N antibody and another commercially available anti-AC5 antibody (FabGennix, Shreveport, LA, U.S.A.) were identical (see Supplementary Figure S1 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/406/bj4060383add.htm), further supporting the anti-AC5N antibody authentically detecting endogenous AC5. Co-localization of AC5 and DiI (a membrane-partitioning fluorescent dye) demonstrated the existence of AC5 in the membrane fractions of striatal neurons (see Supplementary Figure S2 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/406/bj4060383add.htm). In addition, AC5-positive signals could also be detected in the intracellular compartment (Figure 2E), which has also been found for other AC isoforms [10]. In contrast with the striatum-enriched pattern of AC5, Ric8a was expressed in most of the brain areas examined (Figure 2D). Most importantly, co-localization of AC5 with Ric8a was observed in many brain regions including the striatum (Figure 2E) and in primary striatal neurons (Figure 2F).

Figure 2. Co-localization of AC5 and Ric8a in vivo.

(A) Characterization of anti-AC5N, an anti-AC5 antibody. Equal amounts (100 μg) of plasma membrane fractions from the striatum were loaded into each lane for Western blot analysis using anti-AC5N (1:10000 dilution) in the absence or presence of excess antigen (GST–AC5N1–215; 500 μg/ml) as indicated. (B) Equal amounts (100 μg) of whole-brain lysates from E19 rat brains were loaded into each lane for Western blot analysis using the affinity-purified anti-Ric8a antibody (1:500 dilution) in the absence or presence of excess antigen (GST–Ric8a; 500 μg/ml) as indicated. Brain sections were stained with either AC5N (C) or the anti-Ric8a antibody (D) in the absence or presence of an excess amount of antigen (500 μg/ml; GST–AC5N1–215 and GST–Ric8a respectively). (E) Double immunostaining of AC5 and Ric8a in the striatum of adult rat brains. AC5 was visualized by the streptavidin Alexa Fluor® 488 (green; left-hand panel). Ric8a was visualized by Alexa Fluor® 568 secondary antibody (red; centre panel). The merged image (yellow) is shown in the right-hand panel. The inset shows high magnification of the striatal cell marked with an arrow. (E) Double immunostaining of AC5 and Ric8a in primary striatal neurons (9 days in vitro). AC5 was visualized by the streptavidin Alexa Fluor® 488 (green; left-hand panel). Ric8a was visualized by Alexa Fluor® 568 secondary antibody (red; centre panel). The merged image (yellow) is shown in the right-hand panel. Scale bars are 10 μm.

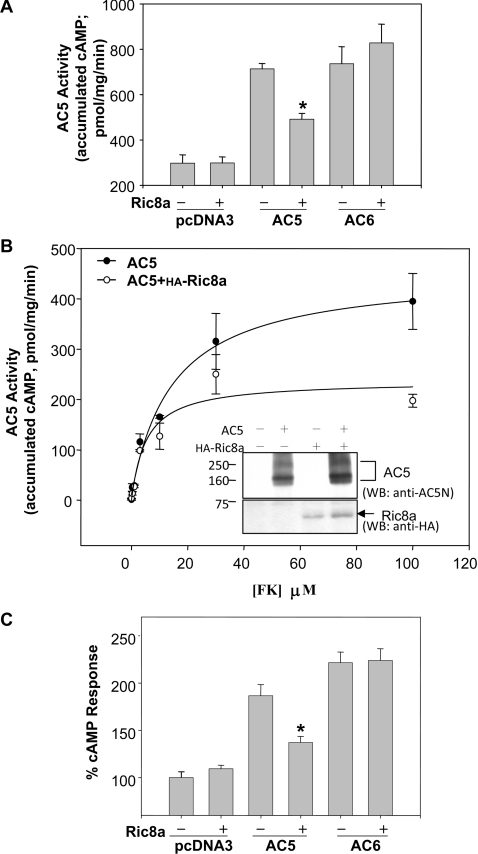

Ric8a was previously identified as a binding partner of several major classes of Gα protein and is thus implicated in their functions [12,13]. This is of particular interest because Gα proteins are key regulators of AC5 [21]. We first determined whether co-expression of Ric8a affected the activity of AC5 in HEK-293T cells where AC5 and Ric8a were co-localized in the membrane fraction (see Supplementary Figure S3 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/406/bj4060383add.htm). As shown in Figure 3A, Ric8a effectively suppressed the forskolin-stimulated activity of AC5, but not that of AC6. The suppressive effect of Ric8a was more obvious at high doses of forskolin (Figure 3B), suggesting that Ric8a might serve as a gatekeeper which prevents damage caused by over-activation of AC5 in trauma (e.g. heart failure [22]). Note that this inhibition of AC5 activity by Ric8a was not caused by a reduction in the expression of AC5. In contrast, due to an unknown mechanism, the expression of Ric8a slightly elevated the protein level of AC5 in HEK-293T cells (Figure 3B). Moreover, Ric8a also markedly suppressed the activation of AC5 induced by the agonist isoprenaline [(isoproterenol)] of a Gαs-coupled receptor (β2-adrenergic receptor) in an isoform-specific manner, while the isoprenaline-evoked activity of AC6 was not affected (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Suppression of AC5 by Ric8a in an isoform-specific manner.

HEK-293T cells were transfected with cDNAs of the indicated AC variant in the absence or presence of Ric8a for 72 h. (A) Membrane fractions were collected and assayed for AC activity evoked by forskolin (100 μM). Results are means±S.E.M. for 15 determinations from five independent experiments. (B) Membrane fractions were collected and assayed for AC5 activity evoked by forskolin at the indicated concentrations. The inset is a representative picture which demonstrates the expression levels of AC5 (upper panel) and Ric8a (lower panel) in membrane fractions (100 μg) of HEK-293T cells transfected with the indicated cDNA by Western blot analysis. Results are means±S.E.M. for three determinations (representative of three independent experiments). (C) Cells were harvested and treated either with or without isoprenaline (10 μM) for 20 min at room temperature in the presence of a phosphodiesterase inhibitor [isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX) 0.5 mM]. Intracellular cAMP levels are expressed as percentages of the cAMP response in the absence of Ric8a in the control, non-treated group. Results are means±S.E.M. for 15 determinations obtained from five independent experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated by one-way ANOVA. *, P<0.01 compared with that in the absence of Ric8a in each group. The cAMP accumulation of the control group obtained from five independent experiments was 659.1±76.0 pmol/106 cells.

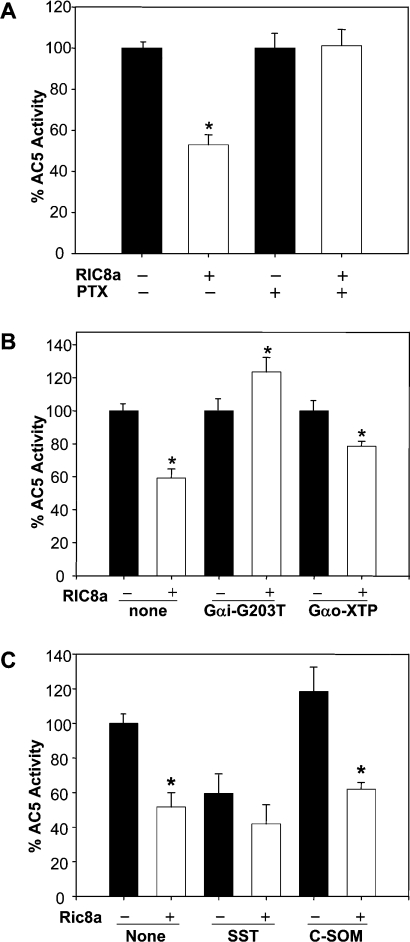

Since Ric8a has been shown to serve as a GEF of Gαi proteins that negatively regulates AC5 [12], we next investigated the involvement of Gαi proteins in the action of Ric8a. As shown in Figure 4(A), inactivation of Gαi/Gαo using 0.1 μg/ml PTX (pertussis toxin) eliminated the inhibitory effect of Ric8a on AC5 activity. Expression of a dominant negative Gαi mutant, Gαi2G203T, [23] also blocked the action of Ric8a, whereas a Gαo dominant negative mutant, Gαo-XTP [24], did not affect the inhibitory effect of Ric8a (Figure 4B). These observations suggest that Gαi might be involved. We noted that chronic treatment of HEK-293T cells with either PTX or Gαi2G203T reduced AC5 activity (see the legend for Figure 4). This might have been due to compensation for the chronic suppression of the Gαi protein as reported previously [25]. Most interestingly, activation of Gαi by stimulating an endogenous Gαi/o-coupled receptor (the somatostatin receptor, sstr2) [26,27] reduced AC5's activity as expected. Importantly, Ric8a did not further suppress AC5's activity in the presence of SST (somatostatin), indicating that the action of Ric8a might overlap with that utilized by SST. On the other hand, the inhibitory effect of Ric8a on AC5 was not abolished by an antagonist of sstr2 [C-SOM (cyclo-somatostatin)] (Figure 4C), demonstrating that activation of a Gαi/o-coupled receptor is not required.

Figure 4. Inhibition of AC5 by Ric8a requires Gαi.

HEK-293T cells were transfected with an empty vector or AC5 cDNA in the absence or presence of the indicated cDNAs for 2 days. (A) Cells were treated with or without PTX (0.1 μg/ml) for an additional 16 h. Membrane fractions were collected. The AC5 activities evoked by forskolin (100 μM) are expressed as percentages of the AC5 activity in the absence of Ric8a in each group. Results are means±S.E.M. for 17 determinations obtained from five independent experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated by one-way ANOVA. The AC5 activities in the absence of Ric8a for the control and PTX-treated groups obtained from five independent experiments were 137.7±18.9 and 63.7±6.9 pmol/min per mg of protein respectively. (B) The AC5 activities evoked by forskolin (100 μM) are expressed as percentages of the AC5 activity in the absence of Ric8a in each group. Results are means±S.E.M. for nine determinations obtained from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated by one-way ANOVA. The AC5 activities in the absence of Ric8a for the control, Gαi-G203T and Gαo-XTP-transfected groups obtained from three independent experiments were 137.0±24.3, 89.1±11.4 and 131.6±18.0 pmol/min per mg of protein respectively. (C) AC5 activities were evoked by forskolin (10 μM) plus SST (5 μM) or C-SOM (0.1 nM). The results are expressed as percentages of AC5 activity in the control membrane, and represented as means± S.E.M. for nine determinations from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was evaluated by one-way ANOVA. The AC5 activity in the control membranes from three independent experiments was 32.6±5.7 pmol/min per mg of protein. *, P<0.01 compared with cells in the absence of Ric8a in each group.

DISCUSSION

Although a handful of interacting proteins (including Gαi, Gαs, RGS2 and PAM) that bind to the catalytic domains (C1 and C2) of AC5 have been reported [3,4,28–31], Ric8a is a unique binding protein of AC5 because it binds to the most divergent N-terminal residues of AC5. For example, PAM was earlier found to bind to the C2 domain of AC5 and to suppress its activity [4]. Because the C2 domain of AC5 is highly conserved among the AC superfamily, PAM also inhibits several other isoforms of AC. On the contrary, the suppression of AC5 mediated by Ric8a is highly selective and isoform-specific (Figures 3A and 3C), because Ric8a binds to the most variable domain of AC5. Interestingly, because Ric8a also binds to Giα and Gsα, which are associated with the catalytic core of AC isoenzymes [28,30], immunoprecipitation of AC6 or an AC5 variant (AC5Δ215) lacking the N-terminus sometimes also pulled-down Ric8a (results not shown). Such binding between Ric8a and AC6 was most probably due to an association of Ric8a with the catalytic domains of AC via Gα proteins. It should be pointed out that our data demonstrate that only binding to the N-terminus of AC5 caused suppression of AC, since the activity of AC6 was not affected by Ric8a (Figure 3).

Besides Ric8a, another interacting protein of AC5 (PAM) also contains a GEF domain [4,12]. At least two GEFs (PAM and Ric8a) negatively modulate the activity of AC5 via direct binding. Note that although Ric8a is considered a G-protein activator, it is unable to activate trimeric forms of G-proteins in vitro [12]. Indeed, in the absence of AC5, Ric8a by itself did not alter AC activity (Figures 3A and 3C). Nevertheless, in the presence of AC5, but not AC6, Ric8a suppressed AC5 activities in a Gαi-dependent manner (Figures 3 and 4). One attractive hypothesis is that, in the membrane environment as examined herein, binding to the N-terminus of AC5 allows Ric8a to activate Gαi proteins in the absence of receptor activation. In line with this theory, the suppressive effect of Ric8a on AC5 activity was evident even in the presence of C-SOM, which blocks the potential activation of Gαi by endogenous sstr2 (Figure 4C). Further study is necessary to explore whether binding with the N-terminus of AC5 stimulates GEF activity of Ric8a in vivo. In addition to interacting with Gαi, Ric8a has also been shown to bind and regulate Gαq, Gα13 and Gαo [12]; it will be of great interest in the future to explore whether the expression of AC5 might provide an additional layer of regulation for receptor-independent G-protein activation.

Online data

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms S. P. Lee for help with the fluorescence microscopy analysis and Mr Dan Chamberlin for editing the manuscript. This work was supported by grants (NHRI-EX92-9203NI, NHRI-EX93-9203NI and NHRI-EX94-9203NI) from the National Health Research Institutes and Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan.

References

- 1.Ishikawa Y., Katsushika S., Chen L., Halnon N. J., Kawabe J., Homcy C. J. Isolation and characterization of a novel cardiac adenylylcyclase cDNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:13553–13557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dessauer C. W., Tesmer J. J., Sprang S. R., Gilman A. G. The interactions of adenylate cyclases with P-site inhibitors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1999;20:205–210. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salim S., Sinnarajah S., Kehrl J. H., Dessauer C. W. Identification of RGS2 and type V adenylyl cyclase interaction sites. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:15842–15849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scholich K., Pierre S., Patel T. B. Protein associated with Myc (PAM) is a potent inhibitor of adenylyl cyclases. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:47583–47589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunahara R. K., Dessauer C. W., Gilman A. G. Complexity and diversity of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1996;79:461–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.002333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sunahara R. K., Dessauer C. W., Whisnant R. E., Kleuss C., Gilman A. G. Interaction of Gsα with the cytosolic domains of mammalian adenylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:22265–22271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu C., Cooper D. M. Calmodulin-binding sites on adenylyl cyclase type VIII. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:8012–8021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kao Y. Y., Lai H. L., Hwang M. J., Chern Y. An important functional role of the N-terminus domain of type VI adenylyl cyclase in Gαi-mediated inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:34440–34448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401952200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai H. L., Lin T. H., Kao Y. Y., Lin W. J., Hwang M. J., Chern Y. The N-terminus domain of type VI adenylyl cyclase mediates its inhibition by protein kinase C. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:644–650. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.3.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou J.-l., Huang C.-L., Lai H.-L., Hung A. C., Chien C.-L., Kao Y.-Y., Chern Y. Regulation of type VI adenylyl cyclase by Snapin, a SNAP25-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:46271–46279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crossthwaite A. J., Ciruela A., Rayner T. F., Cooper D. M. F. A direct interaction between the N-terminus of adenylyl cyclase AC8 and the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 2A. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;69:608–617. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tall G. G., Krumins A. M., Gilman A. G. Mammalian Ric-8A (Synembryn) is a heterotrimeric Gα protein guanine nucleotide exchange factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:8356–8362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klattenhoff C., Montecino M., Soto X., Guzman L., Romo X., Garcia M. A., Mellstrom B., Naranjo J. R., Hinrichs M. V., Olate J. Human brain synembryn interacts with Gsα and Gqα and is translocated to the plasma membrane in response to isoproterenol and carbachol. J. Cell Physiol. 2003;195:151–157. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou S. Y., Lee Y. C., Chen H. M., Chiang M. C., Lai H. L., Chang H. H., Wu Y. C., Sun C. N., Chien C. L., Lin Y. S., et al. CGS21680 attenuates symptoms of Huntington's disease in a transgenic mouse model. J. Neurochem. 2005;93:310–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding Q., Gros R., Gray I. D., Taussig R., Freely I. P., Ferguson S. S. G., Feldman R. D. Raf kinase activation of adenylyl cyclases: isoform-selective regulation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;66:921–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunah A. W., Wyszynski M., Martin D. M., Sheng M., Standaert D. G. α-Actinin-2 in rat striatum: localization and interaction with NMDA glutamate receptor subunits. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2000;79:77–87. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun C. N., Cheng H. C., Chou J. L., Lee S. Y., Lin Y. W., Lai H. L., Chen H. M., Chern Y. Rescue of p53 blockage by the A(2A) adenosine receptor via a novel interacting protein, translin-associated protein X. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;70:454–466. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.021261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chern Y., Lai H. L., Fong J. C., Liang Y. Multiple mechanisms for desensitization of A2a adenosine receptor-mediated cAMP elevation in rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993;44:950–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuoka I., Suzuki Y., Defer N., Nakanishi H., Hanoune J. Differential expression of type I, II, and V adenylyl cyclase gene in the postnatal developing rat brain. J. Neurochem. 1997;68:498–506. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68020498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanoune J., Defer N. Regulation and role of adenylyl cyclase isoforms. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001;41:145–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iwatsubo K., Minamisawa S., Tsunematsu T., Nakagome M., Toya Y., Tomlinson J. E., Umemura S., Scarborough R. M., Levy D. E., Ishikawa Y. Direct inhibition of type 5 adenylyl cyclase prevents myocardial apoptosis without functional deterioration. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:40938–40945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winitz S., Gupta S. K., Qian N. X., Heasley L. E., Nemenoff R. A., Johnson G. L. Expression of a mutant Gi2 alpha subunit inhibits ATP and thrombin stimulation of cytoplasmic phospholipase A2-mediated arachidonic acid release independent of Ca2+ and mitogen-activated protein kinase regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:1889–1895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu B., Simon M. I. Interaction of the xanthine nucleotide-binding Goα mutant with G protein-coupled receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:30183–30188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hadcock J. R., Port J. D., Malbon C. C. Cross-regulation between G-protein-mediated pathways: activation of the inhibitory pathway of adenylylcyclase increases the expression of β2-adrenergic receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:11915–11922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Law S. F., Yasuda K., Bell G. I., Reisine T. Giα3 and Goα selectively associate with the cloned somatostatin receptor subtype SSTR2. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:10721–10727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tallent M., Reisine T. Giα1 selectively couples somatostatin receptors to adenylyl cyclase in pituitary-derived AtT-20 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;41:452–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dessauer C. W., Tesmer J. J., Sprang S. R., Gilman A. G. Identification of a Giα-binding site on type V adenylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:25831–25839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sunahara R. K., Dessauer C. W., Whisnant R. E., Kleuss C., Gilman A. G. Interaction of Gsα with the cytosolic domains of mammalian adenylyl cyclase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:22265–22271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tesmer J. J., Sunahara R. K., Gilman A. G., Sprang S. R. Crystal structure of the catalytic domains of adenylyl cyclase in a complex with Gsα·GTPS. Science. 1997;278:1907–1916. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5345.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan S.-Z., Huang Z.-H., Rao V. D., Hurley J. H., Tang W.-J. Three discrete regions of mammalian adenylyl cyclase form a site for Gsα activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:18849–18854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.18849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.