Abstract

Chlamydia trachomatis (Ct) comprises distinct serogroups and serovars. The present study evaluates a novel Ct amplification, detection, and genotyping method (Ct-DT assay). The Ct-DT amplification step is a multiplex broad-spectrum PCR for the cryptic plasmid and the VD2-region of ompl. The Ct-DT detection step involves a DNA enzyme immunoassay (DEIA) using probes for serogroups (group B, C, and intermediate) and the cryptic plasmid, permitting sensitive detection of 19 Ct serovars (A, B/Ba, C, D/Da, E, F, G/Ga, H, I/Ia, J, K, L1, L2/L2a, and L3) without any cross-reactivity with other Chlamydia species and pathogenic bacteria or commensal organisms of the genital tract. Ct-positive samples are analyzed by a nitrocellulose-based reverse hybridization assay (RHA) containing probes for the 19 different serovars and for the cryptic plasmid. The sensitivity of the PCR-DEIA on clinical specimen is equivalent to that of the Cobas TaqMan assay [κ = 0.95 (95% confidence interval = 0.92 to 0.99)]. Using the RHA, 98% of the Ct-DT detection step-positive samples could be typed. Analysis of cervical swabs from Uganda and The Netherlands revealed that the most common serovars in Uganda are G/Ga (45%), E (21%), K (13%), and F (8%), and in The Netherlands serovars E (38%), F (23%), G/Ga (11%), and D/Da (7%) were most common. Thus, multiplex broad-spectrum PCR in combination with DEIA and RHA permits highly sensitive and specific detection and identification of Ct serovars.

Chlamydia trachomatis (Ct) is the most prevalent sexually transmitted bacterial pathogen. Annually, approximately 90 million new cases occur worldwide.1,2 Most infections remain asymptomatic, but when left untreated, these infections can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, and tubal infertility.3 C. trachomatis is also responsible for chronic keratoconjunctivitis (trachoma) that can cause blindness.4,5 As a species, C. trachomatis can be further divided into three serogroups, and subsequently into 19 serovars, including the five genovariants Ba, Da, Ia, Ga, and L2a.

Serovar identification is based on differences in the amino acid sequence of the major outer membrane protein (MOMP). Serovars were initially distinguished by culture of the strain and subsequent identification by monoclonal antibodies.6,7 The three main phylogenetic branches within the omp1 gene (encoding MOMP) represent serogroups B, C, and the intermediate group. The serogroup B complex comprises serovars B/Ba, D/Da, E, L1, and L2/L2a. The serogroup C complex contains serovars A, C, H, I/Ia, J, K, and L3; and the intermediate group contains serovars F and G/Ga.

The different serovars of C. trachomatis display diverse biological activities. Serovars A, B/Ba, and C are commonly associated with an ocular disease, trachoma.8 Serovars D/Da, E, F, G/Ga, H, I/Ia, J, and K are common in the urogenital tract and can sometimes be detected in the respiratory tract of infants,9 whereas serovars B and C are rarely detected in the urogenital tract.10 The serovars L1, L2/L2a, and L3 are mainly detected in the inguinal lymph nodes and the rectum and may cause lymphogranuloma venereum.11

C. trachomatis infection may also be a cofactor for an enhanced risk for the development of cervical cancer.12,13 The primary cause of cervical cancer is persistent infection with high-risk human papillomavirus, but C. trachomatis may also play a role in this process. Human papillomavirus and C. trachomatis are the most common sexually transmitted infections of the cervix and are often co-transmitted.14

Because C. trachomatis serovars may be associated with diverse clinical manifestations and little is known about the epidemiology of the different serovars, there is a clear need for accurate and efficient genotyping tools.2 Laboratory diagnosis of C. trachomatis infection is routinely performed by molecular methods such as PCR or liquid hybridization. Most assays aim at detection of the cryptic plasmid [Cobas TaqMan (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN); Hybrid Capture 2 (Digene Corporation, Gaithersburg, MD)]1,15 or ribosomal RNA genes [Pace 2 System (Gen-Probe Corporation, San Diego, CA)]. These commercial assays detect the presence of C. trachomatis but cannot differentiate between the different serovars. Serotype identification based on the omp1 gene can be performed by DNA sequencing,16 by restriction fragment length polymorphism,17 or by reverse hybridization.2,15 The aim of the present study was to evaluate a novel Ct amplification, detection, and genotyping system (Ct-DT assay), which combines sensitive detection of C. trachomatis infection by a multiplex broad-spectrum PCR and microtiterplate hybridization, targeting at the cryptic plasmid and the omp1 with the possibility to identify C. trachomatis serovars in positive samples by reverse hybridization, using the same amplicons.

Materials and Methods

Reference Strains

Cultured Chlamydia strains representing 14 different serovars (A/Sa-1, B/TW-5, C/UW-1, D/IC-CAL-8, E/DK-20, F/MRC-301, G/IOL-238, H/UW-4, I/UW-12, J/UW-36, K/UW-31, L1/440-L, L2/434-B, and L3/404-L), Chlamydophila psittaci isolate 6BC, Chlamydophila pneumoniae isolate TW183, and Chlamydia muridarum isolate MoPn were obtained from the Reinier de Graaf Hospital and the VU University Medical Center and grown/isolated as described previously.18 The serovar of each of the C. trachomatis isolates was confirmed by sequencing of the VD2 fragment of the omp1 gene. The most relevant non-Chlamydia pathogenic bacteria present in the genital tract used for specificity analysis of the multiplex broad-spectrum PCR are Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli, Gardnerella vaginalis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus.

Clinical Specimens

Cervical swab specimens were obtained from women attending the gynecology outpatient clinic of the Reinier de Graaf Hospital. Based on the initial diagnosis by an in-house PCR assay, 99 consecutive C. trachomatis-positive samples were selected. In addition, 191 ThinPrep cervical swab samples were obtained from women attending a primary health care center in Kampala, Uganda, between January 2003 and May 2005. Cervical swabs were used to obtain cervical cells, which were resuspended in PBS (Delft) or PreservCyt (Uganda).

DNA Isolation

DNA isolation from the cultured strains was performed with the QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany), including overnight pretreatment with proteinase K.

DNA from the clinical specimens was isolated from 200 μl of cervical cell suspension using the MagnaPure LC Isolation instrument and the Total Nucleic Acid isolation kit as described by the manufacturer (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Isolated DNA was resuspended in a final volume of 100 μl of dilution buffer, and 10 μl was used for each PCR sample (Primus HT multiblock thermal cycler; MWG-Biotech AG, Ebersberg, Germany).

C. trachomatis Sequences from GenBank

C. trachomatis omp1 sequences were obtained from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/index.html) and were used for the selection of the primers and probes. The GenBank numbers used for primer/probe selection were: Serovar A, M58938; Serovar B/Ba, AF063194, AF304856, AY535080, AY378287, and DQ064281; Serovar C, AF352789 and AY380118; Serovar D/Da, AY535092, AY535093, AF063196, AY535090, AY535087, AY535094, AY535089, AY535095, and AY535091; Serovar E, AY535111, U78528, AY535100, U78532, AY535106, AY535104, AY535099, U78536, AY535107, and AY535109; Serovar F, AY535118, AY535123, AY535120, AY535121, and AY535124; Serovar G, AY535136, AY535131, AY535127, and AY535134; Serovar H, AY535137 and AY464146; Serovar I/Ia, AY535152, AF202456, AY535139, AY535140, AY535144, AY535148, and AY535150; Serovar J/Ja, AY535156, AY535161, AY535165, AY535157, AY535162, and AY535166; Serovar K, AY535172, AY535167, AY535168, AY535169, and AY535170; Serovar L1, L35606 and M36533; Serovar L2/L2a, AF304858, DQ064295, and DQ217607; and Serovar L3, X55700.

C. trachomatis Amplification Step

From the Ct-DT assay (Labo Biomedical Products BV, Rijswijk, The Netherlands), the amplification step comprises a Ct-multiplex-broad-spectrum PCR primer mix with multiple forward and reverse primers, targeting regions A and E, as shown in Figure 1 and generating a biotinylated amplicon of 157 to 160 bp from the omp1 VD2 region (Figure 1, region D). The following forward (fw) and reverse (rv) primers are included in the primer mix: momp-fw1bio, 5′-TTCAATTTAGTTGGATTGTTTGG-3′; momp-fw2bio, 5′-TCAACTTAGTTGGITTATTCGG-3′; momp-fw3bio, 5′-TCAATTTAGTGGGGTTATTCGG-3′; momp-rv1bio, biotin-5′-CACATTCCCAGAGAGCTGC-3′; momp-rv2bio, biotin-5′-CACATTCCCACAAAGCTGC-3′; momp-rv3bio, biotin-5′-CGGACTCCCACAAAGCTGC-3′; and momp-rv4bio, biotin-5′-GCACTCCCACAAAGCTGC-3′. The primer mix also contains the following primers to generate a 241-bp amplicon from the cryptic plasmid: KL1, 5′-TCCGGAGCGAGTTACGAAGA-3′; and KL2-bio, biotin-5′-AATCAATGCCCGGGATTGGT-3′.19

Figure 1.

Alignment of the 157- to 160-bp target sequences from the VD2 omp1 gene, which are amplified by the Ct-amplification step, generating region D. Regions A and E are the targets for forward and reverse primers, respectively. The interprimer region (B) is used as target for serovar-specific probes. Serogroup-specific probes are aimed at region C. The reference sequences that were used for this alignment are as follows: Serovar A, M58938; Serovar B, DQ064281; Serovar C, AF352789; Serovar D, AF063196; Serovar E, AY535104; Serovar F, AY535123; Serovar G, AY535136; Serovar H, AY535137; Serovar Ia, AY535150; Serovar J, AY535161; Serovar K, AY535167; Serovar L1, M36533; Serovar L2, DQ064295; and Serovar L3, X55700.

The PCR mix consisted of 10 μl of isolated DNA, 2.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1× GeneAmp PCR Buffer II, 1.5 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), 0.2 mmol/L deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 15 pmol of each primer (Eurogentec S.A., Seraing, Belgium) in a total volume of 50 μl. The standard PCR program involves a 9-minute preheating step at 94°C followed by 40 cycles of amplification (30 seconds at 94°C, 45 seconds at 55°C, and 45 seconds at 72°C) and a final 5-minute elongation step at 72°C.

Gel Electrophoresis

Gel electrophoresis was performed on 3% agarose gels for 225 to 300 volt-hours in 0.5× Tris borate-EDTA buffer.

Sequence Analysis

Amplified DNA fragments were excised from the 3% Tris-borate-EDTA agarose gels and purified with the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen). Purified amplicons were directly sequenced using the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). The sequenced products were subsequently analyzed using the ABI 3100-Avant Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The resulting DNA sequences were analyzed with the Vector NTI Advance 9.0 software (Invitrogen) and compared with C. trachomatis serovars present in GenBank using the BLAST software (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).20

C. trachomatis Detection Step

The Ct detection step from the Ct-DT assay comprises a DNA enzyme immunoassay (DEIA) with a mix of conserved probes. As the first step in the analysis of C. trachomatis, PCR products were hybridized to a mixture of probes for the cryptic plasmid and the omp1 gene (Figure 1, region C) in a DEIA.21 This assay permits general detection of the presence of C. trachomatis DNA in a clinical sample. Briefly, the biotinylated PCR products are captured onto streptavidin-coated microtiter plates and denatured by the addition of NaOH. Uncaptured DNA strands are removed by washing. A mix of one digoxigenin-labeled cryptic plasmid probe and four digoxigenin-labeled serogroup probes were added and hybridized to the captured strand of the PCR product. After washing, the hybrids are detected by an enzymatic reaction, resulting in a colored product. The optical density at 450 nm is measured in each well and evaluated by comparison with titrated positive, borderline positive, and negative controls included in each DEIA run.

Cobas TaqMan Ct Testing

The Cobas TaqMan Ct test (Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ) was performed exactly according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The test to detect C. trachomatis in clinical samples is run on the Roche Diagnostics Cobas TaqMan 48 Analyzer, an instrument that offers automated real-time PCR amplification and detection in a closed system. The Cobas TaqMan 48 Analyzer can process up to 48 tests per cycle and provide results in 2.5 hours after sample preparation. Systematic internal controls and built-in cross-contamination prevention further enhance reliability of results.

C. trachomatis Genotyping Step

The Ct genotyping step from the Ct-DT assay is based on the reverse hybridization assay (RHA) methodology,22 allowing the simultaneous identification of multiple C. trachomatis serovars in a single hybridization step. This assay is based on the serovar-specific sequence heterogeneity in the VD2 region of the omp1 gene (Figure 1) permitting the development of specific probes for the three serogroups (B, C, and intermediate), 14 different serovars (the differentiation between B and Ba, D and Da, G and Ga, I and Ia, and L2 and L2a is not possible), and the cryptic plasmid.

The RHA kit, containing the strips and all assay reagents, was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 10 μl of the biotin-labeled multiplex PCR product was mixed with 10 μl of denaturation solution in a plastic trough containing the Ct strip. The mix was incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature. Preheated (37°C) hybridization buffer was added and incubated at 50°C for 1 hour. All incubations and washing steps were performed automatically in an AutoLiPA instrument (Tecan Austria GmbH, Salzburg, Austria). The strips were washed twice for 30 seconds and once for 30 minutes at 50°C with wash solution (3× SSC and 0.1% SDS). After this wash, the strips were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-streptavidin conjugate for 30 minutes at room temperature. Strips were washed twice with rinse solution and once with substrate buffer. Substrate (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate and nitroblue tetrazolium) was added and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature, generating a purple precipitate on the location of hybrid formation. The reaction was stopped by washing for 3 and 10 minutes with rinse solution and by a wash with water. The strips were dried, and the signals were visually interpreted.

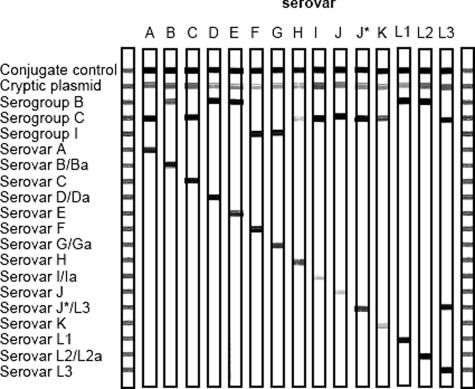

Most of the C. trachomatis serovars are recognized by hybridization to one of the serogroup probes and to a serovar-specific probe. The outline of the RHA strip and representative examples of C. trachomatis serovars are shown in Figure 2. The top line (conjugate control) contains a positive control of biotinylated DNA. Because the C. trachomatis serovars often differ by only a few nucleotides in the interprimer sequences, well-controlled hybridization conditions are required.

Figure 2.

Outline and representative example of the RHA C. trachomatis genotyping step. The positions of the control line and the 19 specific probes for the cryptic plasmid, three different serogroups, and 15 serovars are shown at the left. The letter above each strip indicates the Ct serovar for which DNA was amplified by the multiplex broad spectrum PCR. The exact interpretation of hybrid patterns is described in Materials and Methods. J* was found as a clinical isolate.

An additional probe was included for a genovariant of serovar J (designated J*). This probe also reacts with serovar L3. For this specific genovariant, pattern recognition was used. The genovariant J* was present if probe J*/L3 was positive and the probe for L3 negative. Consequently, in mixed infections of serovar L3 and J*, the serovar J* cannot be identified.

Results

Sensitivity and Specificity of Ct-DT Assay Compared with the Cobas TaqMan

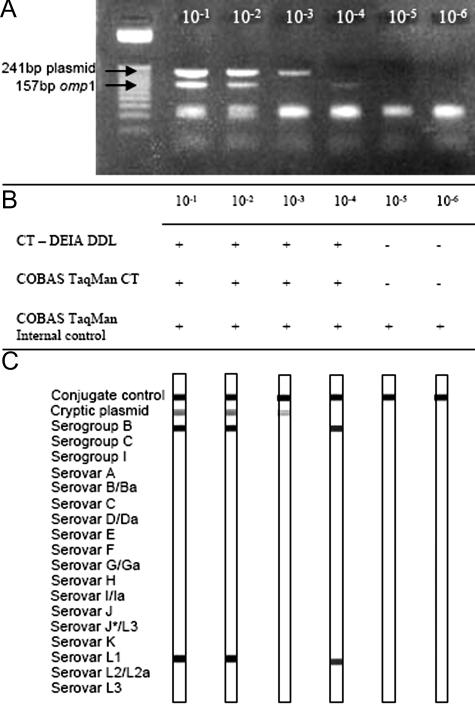

Several 10-fold limiting dilution series of the DNA from C. trachomatis L1 serovars were tested by the multiplex PCR, followed by agarose gel electrophoresis and the DEIA. The same DNA samples were also subjected to analysis by the Cobas TaqMan assay. The exact copy number of C. trachomatis DNA in the dilutions was not known. Analysis on an agarose gel showed that the lower border of detection of the cryptic plasmid in the 10-fold dilution series was similar as for the omp1 gene (Figure 3A). The Ct-DT detection step (DEIA) and the Cobas TaqMan Ct Test were equal in detection of C. trachomatis DNA (Figure 3B) with a sensitivity of 20 copies (according the Manufacturer’s instruction). The Ct-DT assay was able to detect DNA from all strains representing 14 different serovars (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K, L1, L2, and L3). No amplicons were generated from DNA of Chlamydophila psittaci, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Chlamydia muridarum or from the bacterial isolates E. faecalis, E. coli, G. vaginalis, K. pneumoniae, N. gonorrhoeae, P. aeruginosa, S. pyogenes, and S. aureus.

Figure 3.

Limiting dilution series of C. trachomatis DNA, analyzed for the presence of the plasmid and the omp1 gene. A: Agarose gel (3%) showing amplicons from the dilution series of Ct serovar L1. B: DEIA and Cobas TaqMan results. The Cobas TaqMan internal control shows no inhibition. C: RHA results of the corresponding amplicons, which agree with the results of the agarose gel.

Accuracy of Ct-DT Assay in Comparison with the Cobas TaqMan Ct Test in Clinical Specimen

The accuracy of the multiplex PCR-DEIA Ct assay was assessed by testing 290 clinical samples in parallel with the Cobas TaqMan Ct Test. Results are presented in Table 1. Of the 191 samples from Uganda, 51 samples were positive and 135 samples were negative in both assays. Three samples were DEIA negative but COBAS TaqMan positive, and vice versa, two samples were DEIA positive but Cobas TaqMan negative [κ = 0.94 (95% confidence interval 0.88 to 0.99)].

Table 1.

C. trachomatis Detection Results of a Panel of 290 Cervical Swabs from Uganda and the Netherlands Tested with Both the Cobas TaqMan and the Multiplex PCR-DEIA Ct-Detection Step (Ct-DT Assay)

| Cobas TaqMan

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Netherlands (n = 99)

|

Uganda (n = 191)

|

Total | Total (n = 290)

|

|||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | |||

| Multiplex PCR- DEIA | Positive | 97 | 2 | 51 | 2 | 152 | 148 | 4 |

| Negative | 0 | 0 | 3 | 135 | 138 | 3 | 135 | |

| Total | 97 | 2 | 54 | 137 | 290 | 151 | 139 | |

| Not determined | κ = 0.93 (95% confidence interval = 0.88 to 0.99) | κ = 0.95 (95% confidence interval = 0.92 to 0.99) | ||||||

The 99 C. trachomatis-positive samples (as initially determined by an in-house PCR-DEIA) from The Netherlands were all confirmed positive with the new multiplex PCR-DEIA test. Two samples remained negative by Cobas TaqMan but were positive with the multiplex PCR-DEIA. Combining both groups (Table 1), 148 samples (51%) were positive, and 135 (47%) samples were negative with both tests. Four samples (1%) were Cobas TaqMan negative but multiplex PCR-DEIA positive, and three samples (1%) were multiplex PCR-DEIA negative but Cobas TaqMan positive [κ = 0.95, (95% confidence interval 0.92 to 0.99)].

Analytical Specificity of the Ct-DT Genotyping Step

The outline and representative examples of the Ct-genotyping step of Ct-DT assay are shown in Figure 2. The strip comprises a conjugate control line (biotinylated DNA), a probe for the cryptic plasmid, and a series of omp1 probes. The omp1 probes comprise three C. trachomatis serogroup-specific probes and 15 serovar-specific probes representing all of the known serovars. For serovar J, an additional probe was added to detect a genovariant, designated as J*.

Hybridization with amplicons from the 15 different serovar reference isolates (14 serovars and one genovariant) revealed no cross-reaction, and all of the serovar probes were highly specific. The serogroup probes also identified the correct serogroup for each of the reference serovars. The cryptic plasmid probe identified all of the different reference serovars.

Analytical Sensitivity of the Ct-DT Genotyping Step

The same multiplex PCR amplicons analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and DEIA were also characterized by the RHA method. Figure 3C shows that the RHA test of the 10−3 dilution was positive for the cryptic plasmid but remained negative for the serovar probes, whereas the 10−4 dilution showed the opposite results. These results reflect sampling variations that may occur around the border of detection, when only a few copies of the target sequence are present. This phenomenon was observed several times in testing dilution series around the border of detection (data not shown).

Typing of C. trachomatis-Positive Cervical Swabs

Of the 152 clinical samples that were positive for C. trachomatis by the DEIA, 149 were further analyzed by reverse hybridization. In 147 of the 149 samples (99%), the cryptic plasmid and the serogroup and serovar could be determined (Tables 2and 3). In two (1%) of the 149 samples, only the cryptic plasmid was detected by the RHA (Figure 4, lane 7). The results are summarized in Tables 2and 3. Of the 147 serogroup-positive samples, 141 (96%) contain a single Ct infection (Table 2). Only 6 samples (4%) contain multiple C. trachomatis serovars.

Table 2.

C. trachomatis Serogroup Distribution in Positive Samples from The Netherlands and Uganda as Determined by the Ct Genotyping Step

| Infection type | Serogroups detected in clinical samples

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serogroup | The Netherlands [n (%)] | Uganda [n (%)] | Total [n (%)] | |

| Single infection | 90 (96) | 51 (96) | 141 (96) | |

| B | 43 (46) | 14 (26) | 57 (39) | |

| C | 15 (16) | 9 (17) | 24 (16) | |

| Intermediate | 32 (34) | 28 (53) | 60 (41) | |

| Multiple infection | 4 (4) | 2 (4) | 6 (4) | |

| B, C, and Intermediate | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (1) | |

| B and C | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| B and Intermediate | 1 (1) | 2 (4) | 3 (2) | |

| Total | 94 (100) | 53 (100) | 147 (100) | |

Table 3.

Distribution of C. trachomatis Serovars in Samples from The Netherlands and Uganda, as Determined by the RHA Ct Genotyping Step

| Infection type | Serovars detected in the clinical samples

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serovar | The Netherlands [n (%)] | Uganda [n (%)] | Overall [n (%)] | |

| Single infection | 90 (96) | 51 (96) | 141 (96) | |

| D/Da | 7 (7) | 3 (6) | 10 (7) | |

| E | 36 (38) | 11 (21) | 47 (32) | |

| F | 22 (23) | 4 (8) | 26 (18) | |

| G/Ga | 10 (11) | 24 (45) | 34 (23) | |

| H | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (1) | |

| I/Ia | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | |

| J | 5 (5) | 1 (2) | 6 (4) | |

| K | 7 (7) | 0 | 7 (5) | |

| K* | 0 | 7 (13) | 7 (5) | |

| Multiple infection | 4 (4) | 2 (4) | 6 (4) | |

| E, F, I/Ia | 2 (2) | 0 | 2 (1) | |

| E, F | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | |

| E, G/Ga | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| E, I/Ia | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Total | 94 (100) | 53 (100) | 147 (100) | |

Ct-DT assay H and K dual-positive samples were sequenced. K* is the result of sequence analysis of the whole omp1 gene.

Figure 4.

Examples of results that were found with the RHA. Table 3 shows the results after interpretation of the RHA strip (X, unknown).

The intermediate serogroup (containing serovars F and G) is the most prevalent serogroup (41% as a single infection and 3% as a multiple infection), followed by serogroup B (39% as a single infection and 4% as a multiple infection). Serogroup C was detected in only 27 samples (16% in a single infection and 2% as a multiple infection). Overall, the most prevalent serovar was serovar E (32%; serogroup B), followed by serovars G/Ga (23%; intermediate serogroup) and F (18%; intermediate serogroup), as shown in Table 3. Serovars D/Da, H, I/Ia, J, and K were infrequently observed.

In seven samples, reactivity to serovar H and K probes (both serogroup C) was observed (Figure 4, lanes 12 and 14). Sequence analysis of the whole omp1 gene from these seven cases revealed the presence of a sequence closely matching serovar K, which also contained a mutation resulting in a match with the probe for serovar H (data not shown). Therefore, this sequence was designated K*.

The distribution of the serovars and serogroups (Tables 2and 3) showed a clear difference between samples from Uganda and The Netherlands. In both countries, the same percentage of multiple infections (4%) is observed. The most common serovars detected in the Uganda samples were serovar G/Ga (45%), serovar E (21%), K (13%), and F (8%), whereas in The Netherlands, serovar E (38%) was the most prevalent one followed by F (23%), G/Ga (11%), and D/Da (7%). The prevalence of serovars E, F, and G/Ga is significant different between The Netherlands and Uganda.

Genovariant K* was detected in seven samples from Uganda but was not present in samples from The Netherlands. In these cervical samples, serovars A, B, C, L1, L2/L2a, and L3 were not detected.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the novel Ct-DT assay, which combines sensitive detection of C. trachomatis infection with the possibility to identify all different C. trachomatis serovars, using the same amplicons of a multiplex PCR. The advantage of this multiplex PCR is that both the cryptic plasmid and the omp1 gene targets can be detected independently, revealing an increase in sensitivity to detect C. trachomatis.

Analysis of clinical samples showed that the novel detection method has the same sensitivity as the Cobas TaqMan PCR system, which is based on the cryptic plasmid only. The sensitivity of the Cobas TaqMan has been determined on 20 copies of the cryptic plasmid (manufacturer’s instructions; Roche Molecular Systems). In clinical samples and in the 10-fold dilution series, the same sensitivity could be obtained.

Recently, a new variant strain has been isolated in Sweden with a 377-bp deletion in the cryptic plasmid, compromising several commercially available PCR-based systems.23 The PCR included in the present Ct-DT amplification step is aimed at another region of the cryptic plasmid and will therefore be able to also detect the new variant. Further analysis by RHA genotyping on the four Ct-DT-positive/Cobas-negative samples revealed that all contained the endogenous plasmid. Sequence analysis should be done to determine whether a deletion is present.

However, results from the serial dilutions of C. trachomatis DNA showed that around the limit of detection, the assay may show positivity for either the cryptic plasmid or the omp1 gene. This clearly reflects the effect of sampling variation as might be observed in the discrepant samples (Table 1). This may play an important role when input samples contain a very low number of target molecules or when using nonhomogeneous clinical materials, such as cervical swabs or biopsy specimens. Some studies detected plasmid-free C. trachomatis strains.24,25,26 However, sampling variations such as observed in the dilution series may increase the possibility of finding apparent plasmid-negative strains. The disadvantage of a single target PCR-based test like the Cobas TaqMan can result in false negativity, which will be minimized by the novel multiplex PCR DEIA system that recognizes both the cryptic plasmid and the omp1 gene targets.

Serotype identification by analysis of the MOMP gene can be achieved by DNA sequencing,16 by restriction fragment length polymorphism,17 or by reverse hybridization.2,15 The use of large fragments for RLFP (lower sensitivity), nucleotide sequencing (detection of mixed infections), or a nested PCR system for the described RHA methods (introduction of contamination) is not optimally suited for routine diagnostics.

In the cervical material derived from Uganda, the most commonly detected serovar was serovar G/Ga (45%), followed by serovar E (21%). In the cervical swabs derived from The Netherlands, serovars E (38%) and F (23%) were the most common. The high prevalence of serovars E and F is in agreement with other studies. In Australia, the most common serovars were E (41%) and F (26%).2 In Sweden, serovar E (47%) was the most common, followed by serovar F (17%); and in Thailand, serovars F (25%) and D (22.6%) were the most commonly identified.27,28 In Colombia the most common serovars identified were serovars D (22.2%), F (18.5%), and G (13.6%).15 Serovars D, E, F, and G infection may sustain for a longer period than the other serovars, which would result in a more common detection of these serovars in the different populations.29

The present study focused on the diagnosis of urogenital C. trachomatis serovars. However, the RHA typing assay can also identify the serovars A, B/Ba, C, L1, L2/L2a, and L3, which are rarely detected in urogenital samples. Further studies are needed to get more insight in the prevalence of these serovars in different clinical samples and to determine the clinical value of genotyping.

The present Ct-serovar genotyping method aims at the identification of 3 serogroups and the 14 C. trachomatis main serovar types. However, in clinical samples, other genovariants of the serovars may be present that have not yet been fully characterized. These might result in aberrant results on the reverse hybridization strip. The Ct-genotyping RHA step contains serogroup probes and endogenous plasmid probes, which may serve to identify novel serovars or genotypes.

The Ct-DT assay can be used to identify new genovariants. We detected fewer multiple infections (4% in The Netherlands and in Uganda) than in Australia (13%) or Colombia (8.7%).2,30 The difference in detecting mixed infections might be caused by overestimating the presence of multiple types as a result of the absence of probes specific for new variants of C. trachomatis. Seven Uganda samples showed reactivity to probes for both serovars H and K, whereas no single infection of either serovar H or K was observed. Sequence analysis of these samples revealed presence of a variant of serovar K (designated K*). However, to classify a sequence as “a novel genovariant” or serovar, the complete omp1 gene has to be analyzed to confirm this finding.

The RHA technology offers the possibility for highly sensitive identification of multiple infections. However, because our knowledge about genovariants of C. trachomatis is still limited, we suggest that mixed infections of serovars belonging to the same serogroup are verified by sequence analysis.

The combination of Ct amplification, detection, and genotyping assay facilitates the detection and identification of C. trachomatis serovars and serogroups. The principle of screening samples for C. trachomatis with the DEIA method and further analysis of the positive samples with the same amplicon for serovar typing offers a rapid effective method for large epidemiological studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. Lindeman for his contribution and the production of the Ct-DT assay.

Footnotes

Supported by Swedish Agency for Research Cooperation with Developing Countries/Swedish International Development (cooperation) Agency (Sweden) and the Cancer Registry of Norway, which financed a part of the study in Uganda, through a collaborative research agreement with Makerere University.

References

- Gerbase AC, Rowley JT, Heymann DH, Berkley SF, Piot P. Global prevalence and incidence estimates of selected curable STDs. Sex Transm Infect. 1998;74(Suppl 1):S12–S16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong L, Kong F, Zhou H, Gilbert GL. Use of PCR and reverse line blot hybridization assay for rapid simultaneous detection and serovar identification of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1413–1418. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.4.1413-1418.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Owens LM, Marchbanks PA, Amsterdam LF, Mac Kenzie WR. Recurrent chlamydial infections increase the risks of hospitalization for ectopic pregnancy and pelvic inflammatory disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:103–107. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)80020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral K, Osaki S, Shreshta B, Panta CR, Boulter A, Pang F, Cevallos V, Schachter J, Lietman T. Reliability of clinical diagnosis in identifying infectious trachoma in a low-prevalence area of Nepal. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:461–466. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobo LD, Novak N, Munoz B, Hsieh YH, Quinn TC, West S. Severe disease in children with trachoma is associated with persistent Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1524–1530. doi: 10.1086/514151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CC, Wang SP, Holmes KK, Grayston JT. Immunotypes of Chlamydia trachomatis isolates in Seattle, Washington. Infect Immun. 1983;41:865–868. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.2.865-868.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossewaarde JM, Rieffe M, de Vries A, Derksen-Nawrocki RP, Hooft HJ, van Doornum GJ, van Loon AM. Comparison of two panels of monoclonal antibodies for determination of Chlamydia trachomatis serovars. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2968–2974. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2968-2974.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabey DC, Solomon AW, Foster A. Trachoma. Lancet. 2003;362:223–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13914-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darville T. Chlamydia trachomatis infections in neonates and young children. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2005;16:235–244. doi: 10.1053/j.spid.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millman K, Black CM, Johnson RE, Stamm WE, Jones RB, Hook EW, Martin DH, Bolan G, Tavare S, Dean D. Population-based genetic and evolutionary analysis of Chlamydia trachomatis urogenital strain variation in the United States. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2457–2465. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.8.2457-2465.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabey D, Peeling RW. Lymphogranuloma venereum. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78:90–92. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.2.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silins I, Ryd W, Strand A, Wadell G, Tornberg S, Hansson BG, Wang X, Arnheim L, Dahl V, Bremell D, Persson K, Dillner J, Rylander E. Chlamydia trachomatis infection and persistence of human papillomavirus. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:110–115. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JS, Bosetti C, Munoz N, Herrero R, Bosch FX, Eluf-Neto J, Meijer CJ, van den Brule AJ, Franceschi S, Peeling RW. Chlamydia trachomatis and invasive cervical cancer: a pooled analysis of the IARC multicentric case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:431–439. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz N, Castellsague X, de Gonzalez AB, Gissmann L. Chapter 1: HPV in the etiology of human cancer. Vaccine. 2006;24S3:S1–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molano M, Meijer CJ, Morre SA, Pol R, van den Brule AJ. Combination of PCR targeting the VD2 of omp1 and reverse line blot analysis for typing of urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis serovars in cervical scrape specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2935–2939. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.2935-2939.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunham R, Yang C, Maclean I, Kimani J, Maitha G, Plummer F. Chlamydia trachomatis from individuals in a sexually transmitted disease core group exhibit frequent sequence variation in the major outer membrane protein (omp1) gene. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:458–463. doi: 10.1172/JCI117347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morré SA, Ossewaarde JM, Lan J, van Doornum GJ, Walboomers JM, MacLaren DM, Meijer CJ, van den Brule AJ. Serotyping and genotyping of genital Chlamydia trachomatis isolates reveal variants of serovars Ba, G, and J as confirmed by omp1 nucleotide sequence analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:345–351. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.345-351.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer A, Morre SA, van den Brule AJ, Savelkoul PH, Ossewaarde JM. Genomic relatedness of Chlamydia isolates determined by amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4469–4475. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4469-4475.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahony JB, Luinstra KE, Sellors JW, Chernesky MA. Comparison of plasmid- and chromosome-based polymerase chain reaction assays for detecting Chlamydia trachomatis nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1753–1758. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1753-1758.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleter B, van Doorn LJ, ter Schegget J, Schrauwen L, van Krimpen C, Burger MP, ter Harmsel B, Quint WGV. A novel short-fragment PCR assay for highly sensitive broad-spectrum detection of anogenital human papillomaviruses. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:1731–1739. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65688-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleter B, van Doorn LJ, Schrauwen L, Molijn A, Sastrowijoto S, ter Schegget J, Lindeman J, ter Harmsel B, Quint WGV. Development and clinical evaluation of a highly sensitive PCR-reverse hybridization line probe assay for detection and identification of anogenital human papillomavirus. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2508–2517. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2508-2517.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripa T, Nilsson PA. A Chlamydia trachomatis strain with a 377-bp deletion in the cryptic plasmid causing false-negative nucleic acid amplification tests. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:255–256. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31805ce2b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson EM, Markoff BA, Schachter J, de la Maza LM. The 7.5-kb plasmid present in Chlamydia trachomatis is not essential for the growth of this microorganism. Plasmid. 1990;23:144–148. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(90)90033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farencena A, Comanducci M, Donati M, Ratti G, Cevenini R. Characterization of a new isolate of Chlamydia trachomatis which lacks the common plasmid and has properties of biovar trachoma. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2965–2969. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2965-2969.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard DR, Williams JA, Van Der PB, Jones RB. Identification of a Chlamydia trachomatis serovar E urogenital isolate which lacks the cryptic plasmid. Infect Immun. 1998;66:6010–6013. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.6010-6013.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurstrand M, Falk L, Fredlund H, Lindberg M, Olcen P, Andersson S, Persson K, Albert J, Backman A. Characterization of Chlamydia trachomatis omp1 genotypes among sexually transmitted disease patients in Sweden. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3915–3919. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.11.3915-3919.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandea CI, Kubota K, Brown TM, Kilmarx PH, Bhullar V, Yanpaisarn S, Chaisilwattana P, Siriwasin W, Black CM. Typing of Chlamydia trachomatis strains from urine samples by amplification and sequencing the major outer membrane protein gene (omp1). Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:419–422. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.6.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito JI, Jr, Lyons JM, iro-Brown LP. Variation in virulence among oculogenital serovars of Chlamydia trachomatis in experimental genital tract infection. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2021–2023. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.2021-2023.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molano M, Weiderpass E, Posso H, Morre SA, Ronderos M, Franceschi S, Arslan A, Meijer CJ, Munoz N, van den Brule AJ. Prevalence and determinants of Chlamydia trachomatis infections in women from Bogota, Colombia. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:474–478. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]