Abstract

Background and purpose:

Nocistatin (NST) is a neuropeptide generated from cleavage of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) precursor. Evidence has been presented that NST acts as a functional antagonist of N/OFQ, although NST receptor and transduction pathways have not yet been identified. We previously showed that N/OFQ inhibited [3H]5-hydroxytryptamine ([3H]5-HT) release from mouse cortical synaptosomes via activation of NOP receptors. We now investigate whether NST regulates [3H]5-HT release in the same preparation.

Experimental approach:

Mouse and rat cerebrocortical synaptosomes in superfusion, preloaded with [3H]5-HT and stimulated with 1 min pulses of 10 mM KCl, were used.

Key results:

Bovine NST (b-NST) inhibited the K+-induced [3H]5-HT release, displaying similar efficacy but lower potency than N/OFQ. b-NST action underwent concentration-dependent and time-dependent desensitization, and was not prevented either by the NOP receptor antagonist [Nphe1 Arg14,Lys15]N/OFQ(1-13)-NH2 (UFP-101) or by the non-selective opioid receptor antagonist, naloxone. Contrary to N/OFQ, b-NST reduced [3H]5-HT release from synaptosomes obtained from NOP receptor knockout mice. However, both N/OFQ and NST were ineffective in synaptosomes pre-treated with the Gi/o protein inhibitor, Pertussis toxin. NST-N/OFQ interactions were also investigated. Co-application of maximal concentrations of both peptides did not result in additive effects, whereas pre-application of maximal b-NST concentrations partially attenuated N/OFQ inhibition.

Conclusions and implications:

We conclude that b-NST inhibits [3H]5-HT release via activation of Gi/o protein linked pathways, not involving classical opioid receptors and the NOP receptor. The present data strengthen the view that b-NST is, per se, a biologically active peptide endowed with agonist activity.

Keywords: 5-HT release, nociceptin/orphanin FQ, nocistatin, NOP receptor knockouts, pertussis toxin, UFP-101, synaptosomes

Introduction

Nocistatin (NST) is a biologically active neuropeptide generated from the cleavage of the nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) precursor (Okuda-Ashitaka et al., 1998). In contrast to N/OFQ, only the C-terminal portion of the NST sequence is conserved among species, while the full peptide isolated from the bovine, human, rat and mouse brain contains 17, 30, 35 and 41 amino acids, respectively. Bovine NST (b-NST; b-PNP-3) was originally described as a functional antagonist of N/OFQ, devoid of primary agonist activity. In mice, b-NST blocked the induction of hyperalgesia and allodynia induced by intrathecal administration of N/OFQ or prostaglandin E2 (Okuda-Ashitaka et al., 1998) and reversed the N/OFQ inhibition of learning and memory (Hiramatsu and Inoue, 1999), whereas, in rats, it reversed the N/OFQ inhibition of K+-stimulated cortical glutamate release (Nicol et al., 1998) and attenuated the N/OFQ-induced hyperphagia (Olszewski et al., 2000). A number of reports, however, have also shown that b-NST can exert per se biological effects, such as reversal of scopolamine-induced impairment of learning and memory (Hiramatsu and Inoue, 1999), reduction of pain responses in phase I of the formalin test (Yamamoto and Sakashita, 1999), disinhibition of discharge rate of thalamic neurons (Albrecht et al., 2001), increased anxiety (Gavioli et al., 2002) and potentiation of electropuncture-induced analgesia (Huang et al., 2003). Although these effects may be due to interference with endogenous N/OFQ transmission, the finding that b-NST and N/OFQ inhibited different populations of synapses in the spinal cord suggested that b-NST can act also via N/OFQ-independent pathways (Zeilhofer et al., 2000; Ahmadi et al., 2001). Indeed, in vitro studies showed that b-NST bound to mouse brain and spinal cord membranes with high affinity, but it did not displace [3H]N/OFQ binding nor did it prevent N/OFQ inhibition of forskolin-induced cyclic AMP accumulation in CHO cells transfected with the N/OFQ opioid peptide (NOP) receptor (Okuda-Ashitaka et al., 1998). The possibility that NST acts through a yet unidentified G protein-coupled receptor is supported by the finding that rat NST-induced suppression of inhibitory neurotransmission in the rat spinal cord in vitro (Zeilhofer et al., 2000) or b-NST-induced nociception in vivo (Inoue et al., 2003) is sensitive to the Gi/o protein inhibitor, Pertussis toxin (PTX).

We previously showed that N/OFQ inhibited [3H]5-hydroxytryptamine ([3H]5-HT) release from rodent cortical synaptosomes via activation of NOP receptors (Sbrenna et al., 2000; Marti et al., 2003; Mela et al., 2004). We therefore sought to investigate whether and through which mechanisms b-NST regulates [3H]5-HT release in a synaptosomal preparation from the mouse neocortex. In particular, we employed a genetic model (NOP receptor knockout mice; NOP−/− mice) and a pharmacological approach (receptor antagonists) to investigate the involvement of classical opioid and NOP receptors in the b-NST action. Moreover, we tested the PTX sensitivity of the b-NST effects to evaluate the involvement of Gi/o protein-dependent transduction pathways. Finally, we investigated whether b-NST could modulate N/OFQ responses. The present study demonstrates that b-NST presynaptically inhibits [3H]5-HT release via activation of Gi/o protein-mediated mechanisms not involving classical opioid receptors and the NOP receptor.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Swiss mice (20–25 g; Stefano Morini, Modena, Italy), and CD1/C57BL6J/129 NOP+/+ and NOP−/−mice were employed in these studies. NOP+/+ and NOP−/− mice were generated on a mixed C57BL/6J and 129 genetic background (Nishi et al., 1997) and backcrossed with CD1 mice for nine generations (Marti et al., 2004). All animals were genotyped by PCR. Mice were kept under standard conditions (12 h dark:12 h light cycle, free access to food and water), and all procedures concerning animal treatment were in accordance with European Communities Council Directives (86/609/EEC) and National regulations (DL 116/92).

Preparation of synaptosomes

On the morning of the experiment, mice were decapitated under light ether anaesthesia and the fronto-parietal cortex was isolated. Synaptosomes were prepared as previously described (Sbrenna et al., 2000). Briefly, the cortex was homogenized in ice-cold 0.32 M sucrose buffer at pH 7.4 and centrifuged for 10 min at 1000 g (4°C). The supernatant was centrifuged for 20 min at 12 000 g (4°C) with the synaptosomal pellet being resuspended in oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) Krebs solution (mM: NaCl 118.5, KCl 4.7, CaCl2 1.2, MgSO4 1.2, KH2PO4 1.2, NaHCO3 25 and glucose 10) containing ascorbic acid (0.05 mM) and disodium ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA; 0.03 mM).

Synaptosomes were preloaded with [3H]5-HT by incubation (25 min) in medium containing 50 nM [3H]5-HT (specific activity of 30 Ci mmol−1; NEN DuPont, Boston, MA, USA), and 0.8 ml aliquots of the suspension (protein concentration of approximately 0.35 mg protein ml−1) were slowly injected into nylon syringe filters (inner diameter 13 mm, 0.45 μm pore size; internal volume approximately 100 μl; MSI, Westporo, MA, USA) connected to a peristaltic pump. Filters were maintained at 36.5°C in a thermostatic bath and superfused orthogonally at a flow rate of 0.4 ml min−1 with a preoxygenated Krebs solution. Sample collection (every 3 min) started after a 20 min period of filter washout. K+ stimulation (1 min pulse) was applied at the 38th minute. Under these experimental conditions, the 10 mM K+-evoked [3H]5-HT overflow has been previously reported to be largely Ca2+-dependent (∼90%) and tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive (∼50%; Sbrenna et al., 2000; Mela et al., 2004). b-NST and N/OFQ were added to the superfusion medium 9 min before the K+ pulse (unless otherwise stated). Antagonists were added 3 min before agonists and maintained until the end of the experiment.

When PTX was used, the toxin was entrapped into synaptosomes, that is, it was added to the sucrose buffer used for homogenization at a concentration of 5 nM (Raiteri et al., 2000). Following homogenization, synaptosomes were preincubated in Krebs solution containing PTX (5 nM) for 30 min at room temperature, and finally incubated with [3H]5-HT (in the presence of PTX).

[3H]5-HT analysis

At the end of the experiment, superfusate (3 min collection samples) and filter retained radioactivity (dissolved with 0.8 ml of 1 M NaOH followed by 0.8 ml of 1 M HCl and another 0.8 ml of 1 M NaOH) was determined by liquid scintillation spectrophotometry using a Beckman LS 1800 β-spectometer and Ultima Gold XR scintillation fluid (Packard Instruments BV, Groningen, The Netherlands).

Data presentation and statistical analysis

All data are expressed as means±s.e. mean of n determinations. Data were calculated as fractional release (FR, that is, tritium efflux expressed as percentage of the tritium content in the filter at the onset of the corresponding collection period) and expressed as percentage of K+-evoked tritium overflow. K+-evoked tritium overflow was calculated by subtracting the estimated spontaneous efflux (obtained by interpolation between the samples preceding and following the stimulation) from the total efflux observed in the stimulated sample and expressed as percentage of the tritium content in the filter at the onset of the corresponding collection period (NET FR). Statistical analysis was performed on NET FR values by analysis of variance, followed by the Newman–Keuls test for multiple comparisons.

Drugs

N/OFQ, [Nphe1, Arg14, Lys15]N/OFQ(1–13)-NH2 (UFP-101) and b-NST were prepared in the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences at the Ferrara University (Calo et al., 1998; Guerrini et al., 2000). A batch of b-NST was also purchased from NeoMPS (Strasbourg, France) for a comparison. No difference in activity was observed between b-NST synthesized in Ferrara and that commercially available. PTX was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA), naloxone from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK) and [3H]5-HT from Perkin Elmer Life Sciences Inc. (Boston, MA, USA).

All drugs were dissolved in distilled water before use.

Results

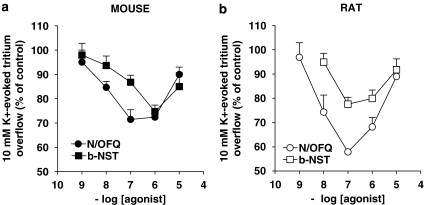

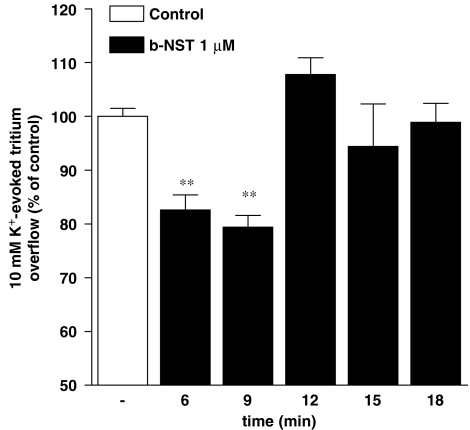

Spontaneous [3H]5-HT efflux (FR) from mouse cortical synaptosomes was 5.34±0.06% (n=190) and was not modified by pretreatment with N/OFQ and b-NST (data not shown). Conversely, tritium overflow (NET FR) evoked by 1 min pulse of 10 mM K+ (2.1±0.1%; n=46) was inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner by both N/OFQ (0.001–10 μM; Figure 1a) and b-NST (0.001–30 μM; Figure 1a). Maximal inhibition was observed at 0.1 μM N/OFQ (∼30% inhibition) and 1 μM b-NST (∼26% inhibition). For both peptides, higher concentrations were found to be ineffective. To investigate whether the effects of b-NST were species-dependent, b-NST was tested in rat cortical synaptosomes (Figure 1b). b-NST inhibited the K+-evoked tritium overflow showing maximal effect at 0.1 μM (∼23%) and loss of efficacy at 10 μM. For a comparison, N/OFQ was also tested (Figure 1b). N/OFQ inhibited tritium overflow in the 1 nM–0.1 μM range, showing maximal efficacy at 0.1 μM (∼40%) and progressive loss of efficacy at higher concentrations (Marti et al., 2003; Mela et al., 2004). As we had previously showed that the effects of N/OFQ were time-dependent (Mela et al., 2004), the effect of a maximal b-NST concentration (1 μM) was studied under different pre-application times (6–21 min before K+; Figure 2). b-NST caused essentially the same extent of inhibition when pre-applied for 6 or 9 min. However, longer pre-application periods resulted in a loss of b-NST efficacy.

Figure 1.

Nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) and bovine nocistatin (b-NST) inhibit [3H]5-HT overflow from cortical synaptosomes. Concentration–response curves describing the effects of N/OFQ (0.001–10 μM) and b-NST (0.001–10 μM) on the K+-evoked [3H]5-HT overflow from mouse (a) and rat (b) neocortical synaptosomes. Maximally effective b-NST concentrations were 1 μM (mouse) and 0.1 μM (rat; analysis of variance followed by the Newman–Keuls test for multiple comparisons). Drugs were perfused 9 min before K+ and maintained until the end of the experiment. Data are expressed as percentage of the K+ stimulation (control) and are means±s.e.m. of 10–20 determinations.

Figure 2.

Time dependency of the bovine nocistatin (b-NST) effect. Effect of b-NST (1 μM) on the K+-evoked [3H]5-HT overflow in neocortical mouse synaptosomes. b-NST was applied for 6, 9, 12, 15 and 18 min before K+ and maintained until the end of the experiment. Data are expressed as percentage of the K+ stimulation (control) and are means±s.e.m. of eight experiments. *P<0.05, **P<0.01; different from control (analysis of variance followed by the Newman–Keuls test for multiple comparisons).

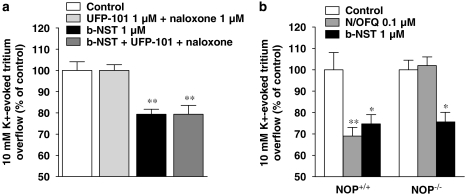

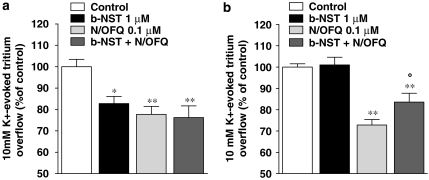

A pharmacological and genetic approach was then taken to study whether the effects of NST were due to activation of classical opioid or NOP receptors. First, b-NST was tested in the presence of a mixture of 1 μM naloxone (a non-selective opioid receptor antagonist) and 1 μM UFP-101 (a selective NOP receptor antagonist). Naloxone and UFP-101, ineffective alone, did not antagonize b-NST inhibition of the K+-evoked tritium overflow (Figure 3a). Second, a maximally effective b-NST concentration (1 μM) was tested in synaptosomes obtained from NOP−/− mice (Figure 3b). Spontaneous and K+-evoked [3H]5-HT overflow from NOP−/− and NOP+/+ mice was not different from that measured in Swiss mice. In NOP+/+ and NOP−/− mice, spontaneous efflux (FR) was 5.8±0.2 and 6.2±0.1% respectively, while the K+-evoked [3H]-5-HT overflow (NET FR) was 1.9±0.2 and 2.2±0.1%. NST (1 μM)inhibited the K+-evoked tritium overflow approximately to the same extent (∼25%) in NOP+/+ and NOP−/− mice. Conversely, N/OFQ inhibited tritium overflow in NOP+/+ (∼30%) but not NOP−/− mice.

Figure 3.

The effect of bovine nocistatin (b-NST) is mediated by neither classical opioid nor N/OFQ opioid peptide (NOP) receptors. (a) Effect of the non-selective opioid receptor antagonist naloxone (1 μM) and the NOP selective receptor antagonist [Nphe1, Arg14, Lys15]N/OFQ(1–13)-NH2 (UFP-101; 1 μM) on the inhibition of K+-evoked [3H]5-HT overflow induced by b-NST (1 μM) in neocortical mouse synaptosomes. Antagonists were perfused 3 min before b-NST and maintained until the end of the experiment. (b) Effect of b-NST (1 μM) and N/OFQ (0.1 μM) on the K+-evoked [3H]5-HT overflow from neocortical synaptosomes obtained from wild-type (NOP+/+) and NOP receptor knockout (NOP−/−) mice. Data are expressed as percentage of the K+ stimulation (control) and are means±s.e.m. of 8–12 determinations. *P<0.05; **P<0.01, different from control (analysis of variance followed by the Newman–Keuls test for multiple comparisons).

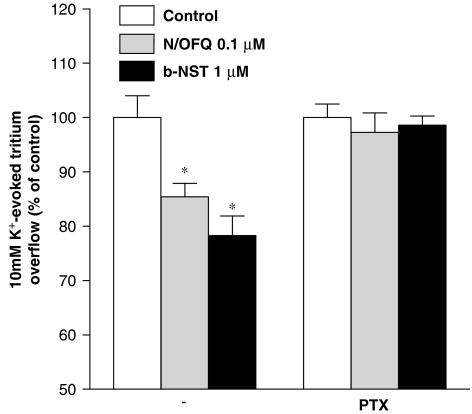

To provide evidence for Gi/o protein involvement in the b-NST inhibition of [3H]-5-HT overflow, we tested maximally effective b-NST concentrations in synaptosomes pretreated with PTX (5 nM; Figure 4). For a comparison, the effect of N/OFQ under the same conditions was also investigated. PTX treatment did not modify the spontaneous tritium efflux (FR, 5.7±0.1 and 5.9±0.1% in the absence and presence of the toxin, respectively; n=20) nor the K+-evoked [3H]5-HT overflow (NET FR, 2.0±0.1 and 1.8±0.1%, respectively, in the absence and presence of PTX; n=20). However, in the presence of PTX, both N/OFQ (0.1 μM) and NST (1 μM) failed to inhibit the K+-evoked [3H]5-HT overflow (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The effects of bovine nocistatin (b-NST) and nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) are prevented by Pertussis toxin (PTX). Effect of pretreatment with PTX (5 nM) on the inhibition of K+-evoked [3H]5-HT overflow induced by b-NST (1 μM) and N/OFQ (0.1 μM) in mouse neocortical synaptosomes. Data are expressed as percentage of the K+ stimulation (control) and are means±s.e.m. of 8–12 determinations. *P<0.05; different from control (analysis of variance followed by the Newman–Keuls test for multiple comparisons).

Finally, experiments were carried out to investigate whether the two peptides could interact to modulate tritium overflow (Figure 5). First b-NST was challenged with N/OFQ following an ‘agonist protocol'. Co-application of maximally effective concentrations of both peptides (1 and 0.1 μM, respectively), which produced similar inhibition of tritium overflow (Figure 1a), did not produce additive effects (Figure 5a). Then, we tested b-NST following an ‘antagonist protocol'. Application of b-NST (1 μM) 9 min before N/OFQ (0.1 μM; that is, 18 min before K+) significantly attenuated (∼40%) N/OFQ inhibition (Figure 5b). Under these conditions, b-NST alone did not affect tritium overflow (see also Figure 1).

Figure 5.

Nociceptin/orphanin FQ (N/OFQ) and bovine nocistatin (b-NST) interacted in modulating [3H]5-HT overflow. Effect of co-application (a) or pre-application (b) of maximal b-NST (1 μM) and N/OFQ (0.1 μM) concentrations on the K+-evoked [3H]5-HT overflow. (a) Drugs were co-applied 9 min before K+ and maintained until the end of the experiment. (b) b-NST and N/OFQ were applied 18 and 9 min before K+, respectively. Data are expressed as percentage of the K+ stimulation (control) and are means±s.e.m. of 12 (a) or 10 (b) determinations. *P<0.05, **P<0.01; different from control. °P<0.05; different from N/OFQ (analysis of variance followed by the Newman–Keuls test for multiple comparisons).

Discussion

NST is one of the products of cleavage of the prepro-N/OFQ precursor peptide, and it has been isolated from porcine, rat, mouse and human brain (Okuda-Ashitaka et al., 1998; Lee et al., 1999; Joseph et al., 2006). The original finding that NST antagonized N/OFQ actions, although not replicated in all the models tested (Connor et al., 1999; Habler et al., 1999; Shirasaka et al., 1999; Amano et al., 2000), was particularly attractive since it put forward the hypothesis that different by-products of the N/OFQ gene could modulate, in opposite ways, a specific biological function (Zeilhofer et al., 2000; Gavioli et al., 2002). A number of reports have pointed out a physiological role for NST in the regulation of pain transmission at the spinal cord level (for a review see Okuda-Ashitaka and Ito, 2000). However, consistent with the widespread expression of the N/OFQ gene in the CNS (Neal et al., 1999), evidence has been presented for an involvement of this peptide in the modulation of other central functions such as mood (Gavioli et al., 2002), learning and memory (Hiramatsu and Inoue, 1999) and food intake (Olszewski et al., 2000).

We previously showed that N/OFQ inhibited exocytotic (that is TTX- and Ca2+-dependent) 5-HT overflow in the rat and mouse neocortex via activation of presynaptic NOP receptors (Sbrenna et al., 2000; Marti et al., 2003; Mela et al., 2004). Indeed, N/OFQ inhibition of 5-HT release from mouse synaptosomes orthogonally perfused (a preparation that minimizes indirect effects) was prevented by both NOP receptor antagonists (such as UFP-101) and deletion of the NOP receptor gene (Mela et al., 2004). The present finding that PTX prevented N/OFQ inhibition of the K+-stimulated [3H]5-HT release confirmed NOP receptor involvement, since the NOP receptor is coupled to Gi/o proteins (Connor et al., 1996; Knoflach et al., 1996). From a methodological point of view, entrapping PTX into synaptosomes (Raiteri et al., 2000) led to rapid and complete inhibition of N/OFQ effects, without the need of prolonged incubation with the toxin. Consistent with a previous study on [3H]5-HT release from synaptosomes (Sarhan and Fillion, 1999), PTX did not affect K+-stimulated tritium overflow under these conditions. b-NST reproduced the effects of N/OFQ on 5-HT release, evoking a similar degree of inhibition in both rats and mice (while N/OFQ was more effective in rats) and being consistently less potent than N/OFQ. A few in vitro studies have dealt with the effects of NST at the cellular levels; in two of these, b-NST has been shown to exert primary agonist activity, namely inhibition of glycinergic and GABAergic transmission in dorsal horn interneurons (Zeilhofer et al., 2000) or induction of neurogenesis in hippocampal neurons in culture (Ring et al., 2006). In both studies, NST qualitatively replicated N/OFQ effects, although, in the spinal cord, N/OFQ and b-NST inhibited different populations of synapses (Zeilhofer et al., 2000). From a quantitative point of view, a pEC50∼6 has been calculated for b-NST in spinal cord slices (Zeilhofer et al., 2000), while effective b-NST concentrations in a preparation of hippocampal neurons in culture were found to be >1 μM (Ring et al., 2006). These values are similar to those found in mouse cortical synaptosomes but greater than those observed in the rat preparation, possibly suggesting the existence of species-dependent sensitivity to b-NST. Consistent with previous findings that b-NST did not displace [3H]N/OFQ binding nor did it prevent N/OFQ inhibition of forskolin-induced cyclic AMP accumulation (Okuda-Ashitaka et al., 1998), b-NST inhibition was not attenuated by NOP receptor antagonists or deletion of the NOP receptor gene. Likewise, 1-[(3R,4R)-1-cyclooctylmethyl-3-hydroxymethyl-4-piperidyl]-3-ethyl-1,3-dihydro-2H benzimidazol-2-one (J-113397, a non-peptide NOP receptor antagonist) did not attenuate pro-nociceptive response to b-NST in vivo (Inoue et al., 2003) and deletion of the NOP receptor gene did not affect NST inhibition of neurotransmission in vitro (Ahmadi et al., 2001). b-NST effects in synaptosomes were also naloxone-insensitive, suggesting that the actions of b-NST were not mediated by either the classical opioid receptors or the NOP receptor. Nevertheless, consistent with reports that PTX abolished b-NST-evoked responses in vivo (Inoue et al., 2003) and in vitro (Zeilhofer et al., 2000), PTX also prevented b-NST inhibition of synaptosomal 5-HT release. Zeilhofer et al. (2000) have proposed that a yet unidentified non-opioid and Gi/o protein-coupled receptor mediates electrophysiological effects of NST in the spinal cord. Such a receptor may also be located on cortical nerve terminals releasing 5-HT, although the failure of b-NST in promoting GTP-γ-S binding in brain slices (Neal et al., 2003) challenges this view. However, the autoradiographic method employed in that study may not be sensitive enough to detect small changes at the presynaptic level. To confirm the presence of presynaptic NST–Gi/o protein-linked pathways, loss of response following high b-NST concentrations or prolonged b-NST application time was detected. Consistent with a previous study (Mela et al., 2004), such a loss of response was also observed for N/OFQ. In that study, a 9-min exposure to high concentrations (10 μM) of N/OFQ or the NOP receptor peptide agonist [Arg14, Lys15]N/OFQ failed to affect [3H]5-HT release. However, when applied for a shorter period (that is 3 min), N/OFQ (10 μM) maximally inhibited tritium overflow, suggesting that the loss of response was related to time- and concentration-dependent NOP receptor desensitization. In our preparation, b-NST and N/OFQ clearly activate different receptors although they both act through a Gi/o protein-linked pathway. We thus can speculate that receptor desensitization also underlies the loss of response to high b-NST concentrations. Of note, the anxiogenic effect of b-NST in vivo was also described to follow a bell-shaped dose–response curve (characterized by loss of response to high doses; Gavioli et al., 2002). In vitro, no bell-shaped curve has been reported for b-NST so far. Instead, a careful concentration–response study performed in spinal cord slices showed no loss of response following concentrations as high as 10 μM b-NST or 100 μM rat NST (Zeilhofer et al., 2000). It is possible, however, that experimental reasons (for example, brain area investigated, loss of tissue architecture and/or receptor modulators, different kinetics of drug diffusion) can explain the discrepancy with our study.

On the basis of the positive cooperation between mu opioid (MOP) and NOP receptor agonists in regulating 5-HT release found in rat neocortical synaptosomes (Sbrenna et al., 2000), we attempted to investigate the reciprocal interactions between b-NST and N/OFQ in the same mouse preparation. The lack of additivity at maximal concentrations may be due to a ceiling effect (see also Sbrenna et al., 2000). Alternatively, the possibility of a different representation of NOP and (putative) NST receptors on different populations of serotonergic nerve terminals cannot be ruled out, since evidence that serotonergic nerve terminals are heterogeneous in terms of morphology and pharmacological properties has been presented (Kosofsky and Molliver, 1987; Fritschy et al., 1988; Brown and Molliver, 2000). This view, however, was challenged by the finding that prolonged exposure to b-NST attenuated responses to N/OFQ, which indicates that the two receptors colocalize to some extent. On the basis of this finding, it may be speculated that partial loss of N/OFQ inhibition after prolonged (minutes) exposure to b-NST reflects the occurrence of short-term heterologous desensitization, which has been described within the opioid receptor family (Kovoor et al., 1995; Samoriski and Gross, 2000).

Concluding remarks

Using a combined genetic and pharmacological approach, we demonstrated that b-NST inhibits 5-HT release in the mouse neocortex via activation of a presynaptic Gi/o protein-mediated pathway not involving classical opioid receptors or the NOP receptor. These results represent the first direct evidence of the presence of a functional NST–Gi/o protein-linked pathway on 5-HT terminals in the cerebral cortex and strengthen the view that NST can act through signal transduction mechanisms distinct from N/OFQ. It has been proposed (Calo et al., 2000) that the anxiolytic effect of N/OFQ (Jenck et al., 1997) is due to its ability to inhibit 5-HT transmission both at the somatodendritic (Vaughan and Christie, 1996) and nerve terminal (Sbrenna et al., 2000; Marti et al., 2003; Mela et al., 2004) level. Thus, based on the present data, one would expect NST to replicate the anxiolytic effects of N/OFQ. b-NST has been reported to modulate anxiety in vivo following a bell-shaped curve (Gavioli et al., 2002). Therefore, the possibility that the loss of response (observed at higher doses) is the result of recruitment of anxiolytic mechanisms opposing the anxiogenic ones (activated at lower doses) appears justified on the basis of the present results. In conclusion, although the physiological meaning of the present results remains to be investigated, this study indicates that NST modulates cortical 5-HT transmission and, therefore, may influence biological functions regulated by 5-HT, other than pain transmission.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the University of Ferrara (ex 60%).

Abbreviations

- b-NST

bovine nocistatin

- FR

fractional release

- J-113397

1-[(3R,4R)-1-cyclooctylmethyl-3-hydroxymethyl-4-piperidyl]-3-ethyl-1,3-dihydro-2H benzimidazol-2-one

- N/OFQ

nociceptin/orphanin FQ

- NOP

N/OFQ opioid peptide

- NOP−/−

NOP receptor knockout

- NST

nocistatin

- PTX

Pertussis toxin

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- UFP-101

[Nphe1, Arg14, Lys15]N/OFQ(1–13)-NH2

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmadi S, Kotalla C, Guhring H, Takeshima H, Pahl A, Zeilhofer HU. Modulation of synaptic transmission by nociceptin/orphanin FQ and nocistatin in the spinal cord dorsal horn of mutant mice lacking the nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;59:612–618. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.3.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht D, Bluhdorn R, Siegmund H, Berger H, Calo G. Inhibitory action of nociceptin/orphanin FQ on functionally different thalamic neurons in urethane-anaesthetized rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:333–342. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amano T, Matsubayashi H, Tamura Y, Takahashi T. Orphanin FQ-induced outward current in rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2000;853:269–274. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P, Molliver ME. Dual serotonin (5-HT) projections to the nucleus accumbens core and shell: relation of the 5-HT transporter to amphetamine-induced neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1952–1963. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01952.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calo G, Guerrini R, Bigoni R, Rizzi A, Bianchi C, Regoli D, et al. Structure–activity study of the nociceptin(1-13)-NH2 N-terminal tetrapeptide and discovery of a nociceptin receptor antagonist. J Med Chem. 1998;41:3360–3366. doi: 10.1021/jm970805q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calo G, Guerrini R, Bigoni R, Rizzi A, Marzola G, Okawa H, et al. Characterization of [Nphe(1)]nociceptin(1-13)NH(2), a new selective nociceptin receptor antagonist. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:1183–1193. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor M, Yeo A, Henderson G. The effect of nociceptin on Ca2+ channel current and intracellular Ca2+ in the SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cell line. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:205–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15387.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor M, Vaughan CW, Jennings EA, Allen RG, Christie MJ. Nociceptin, Phe(1)psi-nociceptin(1-13), nocistatin and prepronociceptin(154-181) effects on calcium channel currents and a potassium current in rat locus coeruleus in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:1779–1787. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Lyons WE, Molliver ME, Grzanna R. Neurotoxic effects of p-chloroamphetamine on the serotoninergic innervation of the trigeminal motor nucleus: a retrograde transport study. Brain Res. 1988;473:261–270. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90855-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavioli EC, Rae GA, Calo G, Guerrini R, De Lima TC. Central injections of nocistatin or its C-terminal hexapeptide exert anxiogenic-like effect on behaviour of mice in the plus-maze test. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:764–772. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini R, Calo G, Bigoni R, Rizzi A, Varani K, Toth G, et al. Further studies on nociceptin-related peptides: discovery of a new chemical template with antagonist activity on the nociceptin receptor. J Med Chem. 2000;43:2805–2813. doi: 10.1021/jm990075h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habler H, Timmermann L, Stegmann J, Janig W. Effects of nociceptin and nocistatin on antidromic vasodilatation in hairless skin of the rat hindlimb in vivo. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:1719–1727. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiramatsu M, Inoue K. Effects of nocistatin on nociceptin-induced impairment of learning and memory in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;367:151–155. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Long H, Shi YS, Han JS, Wan Y. Nocistatin potentiates electroacupuncture antinociceptive effects and reverses chronic tolerance to electroacupuncture in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2003;350:93–96. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue M, Kawashima T, Allen RG, Ueda H. Nocistatin and prepro-nociceptin/orphanin FQ 160–187 cause nociception through activation of Gi/o in capsaicin-sensitive and of Gs in capsaicin-insensitive nociceptors, respectively. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:141–146. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.049361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenck F, Moreau JL, Martin JR, Kilpatrick GJ, Reinscheid RK, Monsma FJ, Jr, et al. Orphanin FQ acts as an anxiolytic to attenuate behavioral responses to stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14854–14858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph T, Lee TL, Ning C, Nishiuchi Y, Kimura T, Jikuya H, et al. Identification of mature nocistatin and nociceptin in human brain and cerebrospinal fluid by mass spectrometry combined with affinity chromatography and HPLC. Peptides. 2006;27:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoflach F, Reinscheid RK, Civelli O, Kemp JA. Modulation of voltage-gated calcium channels by orphanin FQ in freshly dissociated hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6657–6664. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06657.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosofsky BE, Molliver ME. The serotoninergic innervation of cerebral cortex: different classes of axon terminals arise from dorsal and median raphe nuclei. Synapse. 1987;1:153–168. doi: 10.1002/syn.890010204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovoor A, Henry DJ, Chavkin C. Agonist-induced desensitization of the mu opioid receptor-coupled potassium channel (GIRK1) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:589–595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TL, Fung FM, Chen FG, Chou N, Okuda-Ashitaka E, Ito S, et al. Identification of human, rat and mouse nocistatin in brain and human nocistatin in brain and human cerebrospinal fluid. NeuroReport. 1999;10:1537–1541. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199905140-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti M, Stocchi S, Paganini F, Mela F, De Risi C, Calo G, et al. Pharmacological profiles of presynaptic nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptors modulating 5-hydroxytryptamine and noradrenaline release in the rat neocortex. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:91–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marti M, Mela F, Veronesi C, Guerrini R, Salvadori S, Federici M, et al. Blockade of nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptor signaling in rat substantia nigra pars reticulata stimulates nigrostriatal dopaminergic transmission and motor behavior. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6659–6666. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0987-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mela F, Marti M, Ulazzi L, Vaccari E, Zucchini S, Trapella C, et al. Pharmacological profile of nociceptin/orphanin FQ receptors regulating 5-hydroxytryptamine release in the mouse neocortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:1317–1324. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal CR, Jr, Mansour A, Reinscheid R, Nothacker HP, Civelli O, Akil H, et al. Opioid receptor-like (ORL1) receptor distribution in the rat central nervous system: comparison of ORL1 receptor mRNA expression with (125)I-[(14)Tyr]-orphanin FQ binding. J Comp Neurol. 1999;412:563–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal CR, Jr, Constance EO, Taylor LT, Hoversten MT, Akil H, Watson SJ., Jr Binding and GTPγS autoradiographic analysis od preorphanin precursor peptide products at the ORL1 and opioid receptors. J Chem Neuroanat. 2003;25:233–247. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(03)00032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicol B, Lambert DG, Rowbotham DJ, Okuda-Ashitaka E, Ito S, Smart D, et al. Nocistatin reverses nociceptin inhibition of glutamate release from rat brain slices. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;356:R1–R3. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00545-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi M, Houtani T, Noda Y, Mamiya T, Sato K, Doi T, et al. Unrestrained nociceptive response and disregulation of hearing ability in mice lacking the nociceptin/orphaninFQ receptor. EMBO J. 1997;16:1858–1864. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda-Ashitaka E, Minami T, Tachibana S, Yoshihara Y, Nishiuchi Y, Kimura T, et al. Nocistatin, a peptide that blocks nociceptin action in pain transmission. Nature. 1998;392:286–289. doi: 10.1038/32660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda-Ashitaka E, Ito S. Nocistatin: a novel neuropeptide encoded by the gene for the nociceptin/orphanin FQ precursor. Peptides. 2000;21:1101–1109. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(00)00247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski PK, Shaw TJ, Grace MK, Billington CJ, Levine AS. Nocistatin inhibits food intake in rats. Brain Res. 2000;872:181–187. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raiteri M, Sala R, Fassio A, Rossetto O, Bonanno G. Entrapping of impermeant probes of different size into nonpermeabilized synaptosomes as a method to study presynaptic mechanisms. J Neurochem. 2000;74:423–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring RH, Alder J, Fennell M, Kouranova E, Black IB, Thakker-Varia S. Transcriptional profiling of brain-derived-neurotrophic factor-induced neuronal plasticity: a novel role for nociceptin in hippocampal neurite outgrowth. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:361–377. doi: 10.1002/neu.20223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samoriski GM, Gross RA. Functional compartmentalization of opioid desensitization in primary sensory neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:500–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarhan H, Fillion G. Differential sensitivity of 5-HT1B auto and heteroreceptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1999;360:382–390. doi: 10.1007/s002109900067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbrenna S, Marti M, Morari M, Calo G, Guerrini R, Beani L, et al. Modulation of 5-hydroxytryptamine efflux from rat cortical synaptosomes by opioids and nociceptin. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:425–433. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaka T, Kunitake T, Kato K, Takasaki M, Kannan H. Nociceptin modulates renal sympathetic nerve activity through a central action in conscious rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R1025–R1032. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.4.R1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan CW, Christie MJ. Increase by the ORL1 receptor (opioid receptor-like1) ligand, nociceptin, of inwardly rectifying K conductance in dorsal raphe nucleus neurones. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:1609–1611. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Sakashita Y. Effect of nocistatin and its interaction with nociceptin/orphanin FQ on the rat formalin test. Neurosci Lett. 1999;262:179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeilhofer HU, Selbach UM, Guhring H, Erb K, Ahmadi S. Selective suppression of inhibitory synaptic transmission by nocistatin in the rat spinal cord dorsal horn. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4922–4929. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-13-04922.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]