Abstract

Little is known about the virulence mechanisms employed by Haemophilus ducreyi in the production of genital ulcers. This Gram-negative bacterium previously has been shown to produce a soluble cytotoxic activity that kills HeLa and HEp-2 cells. We have now identified a cluster of three H. ducreyi genes that encode this cytotoxic activity. The predicted proteins encoded by these genes are most similar to the products of the Escherichia coli cdtABC genes that comprise the cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) of this enteric pathogen. Eleven of 12 H. ducreyi strains were shown to possess this gene cluster and culture supernatants from these strains readily killed HeLa cells. The culture supernatant from a single strain of H. ducreyi that lacked these genes was unable to kill HeLa cells. When the H. ducreyi cdtABC gene cluster was cloned into E. coli, culture supernatant from the recombinant E. coli clone killed HeLa cells. A monoclonal antibody that neutralized this soluble cytotoxic activity of H. ducreyi was shown to bind to the H. ducreyi cdtC gene product. This soluble H. ducreyi cytotoxin may play a role in the development or persistence of the ulcerative lesions characteristic of chancroid.

Keywords: chancroid, bacterial pathogenesis, virulence factor

Chancroid, an ulcerogenital disease caused by the fastidious Gram-negative bacterium Haemophilus ducreyi, remains one of the least understood sexually transmitted diseases (1, 2). However, the recognized association between genital ulcer disease and transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (3, 4) has stimulated investigation of the pathogenesis of chancroid. Prior to this decade, studies by Ronald and coworkers (5), which culminated in recognition of an association between serum resistance and virulence of H. ducreyi, represented the sole successful endeavor to address issues concerning the host-parasite interaction in chancroid. Only recently was it established that this pathogen can adhere to human cells (6, 7) and even invade some of these cells in vitro (7, 8). Although several bacterial products, including a diffusible (soluble) cytotoxin (9–11), pili (12), a cell-associated hemolysin (13, 14), a hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein (15, 16), and lipooligosaccharide (17) have been proposed as virulence factors for this pathogen, there is little known about the pathogenesis of this disease at the molecular level.

This dearth of information about the parasitic strategies used by H. ducreyi is even more apparent when one considers the complex pathology involved in the formation of chancroidal ulcers and buboes. Such basic issues as the causes of tissue necrosis (ulcer formation) and the retardation of healing, both characteristic features of chancroid (2), remain to be fully explained. The possible involvement of protein exotoxins in these processes has been suggested (18), and there has been a series of reports concerning the existence of a soluble cytotoxin elaborated by H. ducreyi that kills HeLa and HEp-2 cells in vitro (9–11).

We have now identified a set of three genes in H. ducreyi that encode predicted protein products that closely resemble (24–51% identity) proteins that comprise the cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) elaborated by certain E. coli strains (19, 20) and by some Shigella and Campylobacter species (21–23). In this report, we demonstrate directly that the proteins encoded by the cdt-like genes in H. ducreyi are responsible for the soluble cytotoxic activity first described by Lagergard and Purven (9–11). In addition, antibody that neutralizes this soluble cytotoxic activity was shown to be directed against one of the three protein products of the H. ducreyi cdt gene cluster.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions.

H. ducreyi strain 35000 is a well-characterized isolate of this pathogen (15). The other 11 H. ducreyi strains used in this study (RO18, BG411, WPB506, LA228, Hd12, Hd13, 541, STD102, 1145, Hd2, and 512) were all originally isolated from chancroidal ulcers of patients in diverse geographic locations and have been described (7, 15). H. ducreyi strains were routinely cultivated on chocolate agar plates as described (24). For detection of CDT activity, H. ducreyi was cultured overnight in brain heart infusion (Difco) broth containing 1% IsoVitalex (BBL), 5% fetal bovine serum, and hemin (50 μg/ml). E. coli strains were grown in Luria–Bertani medium or on Luria–Bertani agar plates (25) with appropriate antimicrobial supplementation.

Genetic Techniques, Nucleotide Sequence Analysis, and PCR Method.

Standard recombinant DNA techniques and nucleotide sequence analysis were performed as described (25, 26). Oligonucleotide primers used in PCR systems in this study are numbered in Fig. 2 and referred to in the text as P#. To obtain certain DNA fragments not contained in recombinant plasmids, a modification of the anchored PCR method was employed (27). Briefly, 2–4 kb fragments of H. ducreyi strain 35000 chromosomal DNA that had been partially digested with Sau3AI were ligated into pBluescript II SK+ (Stratagene), which had been digested with BamHI. The ligation reaction mixture was then subjected to PCR amplification using one oligonucleotide primer corresponding to a known H. ducreyi DNA sequence, with the other primer corresponding to either the T3 or T7 promoter of the vector. All nucleotide sequence data derived from the use of this ligation-based PCR method were confirmed by using PCR to amplify the desired fragment from the H. ducreyi chromosome for nucleotide sequence analysis. Southern blot analysis was performed as described (15). Northern blot and primer extension analyses were performed as described (E.J.H., L.D.C., and C. Aebi, unpublished data) using H. ducreyi cells grown on chocolate agar for 16 hr as the source of RNA.

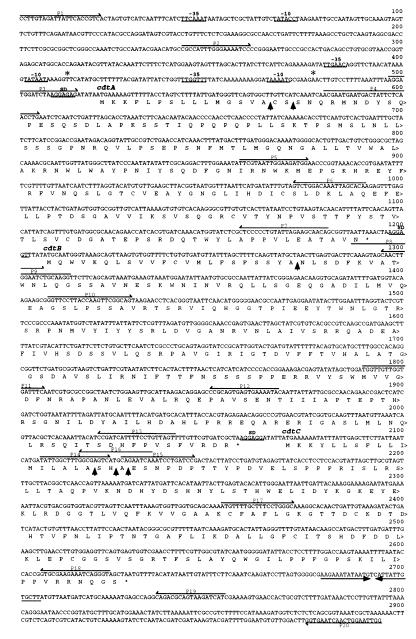

Figure 2.

Nucleotide sequence of the H. ducreyi strain 35000 cdtABC genes together with the deduced amino acid sequence of the predicted proteins. Putative −35 and −10 regions are underlined, as are the putative ribosomal binding sites (SD). An inverted repeat located 3′ from the end of the cdtC gene is indicated by →← opposing arrows. Oligonucleotide primers (P) used in PCR reactions are numbered above the relevant sequences. Putative signal peptidase I cleavage sites are indicted by ↑. Putative transcription initiation sites detected by primer extension studies are indicated by ∗.

Cytotoxicity Assays.

Supernatants from overnight broth cultures of both H. ducreyi and E. coli strains were subjected to sequential centrifugations at 7,600 × g and 140,000 × g to remove bacteria and cellular debris. These supernatants were sterilized by filtration and frozen at −70°C until used. Exposure of eukaryotic cells to culture supernatants was performed as described (9) except that 24-hr-old, 20–30% confluent monolayers were exposed to the culture supernatants for 2 hr at 37°C. After removal of the culture supernatants, the monolayers were incubated for 72 hr. Cell monolayers were then fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in PBS and stained with 0.4% Giemsa.

mAb.

Using spleen cells from mice immunized with proteins released from H. ducreyi strain CCUG 7470 (9) by osmotic shock, an IgG1 mAb was obtained that neutralized the cytotoxic activity of H. ducreyi for HeLa and HEp-2 cells (M.P., A. Frisk, I. Lonnroth, and T.L., unpublished data).

Construction of Protein Fusions.

The H. ducreyi CdtA, CdtB, and CdtC proteins were expressed as fusion proteins after ligating DNA fragments encoding most or all of the putative mature form of each protein into the pRSET vector (Invitrogen) that had been digested with both BamHI and EcoRI. Oligonucleotide primers used in PCR to prepare these DNA fragments contained the appropriate BamHI or EcoRI restriction sites at their 5′ ends and the relevant sequence from the cdt genes. The oligonucleotide primers were: P4 and P7 for CdtA, P8 and P13 for CdtB, P15 and P18 for CdtC. The resultant recombinant plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) and expression of the polyhistidine (His)-Cdt fusion proteins was induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside.

Analysis of Fusion Proteins.

Recombinant E. coli cells containing fusion proteins were disrupted by repeated freeze/thaw cycles. Identical portions of the fusion proteins present in these preparations were resolved by SDS/PAGE and either stained with Coomassie blue or probed with the cytotoxin-neutralizing mAb in Western blot analysis (15).

Expression of H. ducreyi Proteins in Vitro.

The primers used to amplify individual cdt genes from the chromosome of H. ducreyi strain 35000 were: for cdtA, P2 and P9; for cdtB, P5 and P16; and for cdtC, P11 and P20. These PCR products were used in an E. coli S30 extract system for linear DNA templates (Promega). In addition, the cdtA gene (P1 and P9), the cdtAB gene pair (P1 and P16), and the cdtABC gene cluster (P1 and P19) were amplified from the chromosome of strain 35000 by using the primers enclosed in parentheses and subcloned into the plasmid vector pCRII (Invitrogen), yielding the recombinant plasmids pLDC101, pLDC102, and pLDC103, respectively. These plasmids were used in the E. coli S30 extract system for circular DNA templates (Promega). [3H]Leucine was used to radiolabel proteins expressed in these coupled transcription/translation systems.

RESULTS

Identification of the H. ducreyi cdt Gene Cluster.

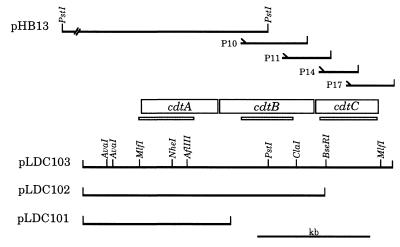

When a genomic library of H. ducreyi strain 35000 was screened for expression of heme-binding activity (15), one of the positive recombinant clones [E. coli RR1(pHB13)] was found to contain an 11-kb PstI fragment of H. ducreyi chromosomal DNA (Fig. 1). Nucleotide sequence analysis of one end of this insert detected a partial ORF encoding an incomplete 16 kDa protein with similarity to the CdtB protein expressed by certain pathogenic strains of E. coli (19, 20). The CdtB protein is encoded by the second of three tightly linked E. coli genes (i.e., cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC) that are required for expression of the cytolethal distending toxin (CDT) by E. coli strain 6468/62 (19). Further investigation revealed that, immediately 5′ from this partial ORF, was a 671-bp ORF encoding a protein with similarity to the E. coli CdtA protein (19, 20).

Figure 1.

Partial restriction enzyme map of the H. ducreyi cdtABC gene cluster. The 11-kb insert from the recombinant plasmid pHB13 is shown in truncated form. The relative position of the four oligonucleotide primers (P10, P11, P14, and P17) used in ligation-based PCR reactions (together with the T3 or T7 primers) to obtain initial sequence information for the downstream half of the cdtB gene and all of the cdtC gene are indicated together with the size of the relevant PCR product. The thin shaded bars (░⃞) beneath the ORFs demarcate the probes used for both Northern and Southern blot analyses. Plasmids pLDC101, pLDC102, and pLDC103 contain the H. ducreyi cdtA, cdtAB, and cdtABC genes as indicated.

Using a modification of the anchored PCR technique, an oligonucleotide primer from the 3′ end of the partial ORF was used to amplify a 600-bp fragment from the H. ducreyi chromosome that spanned the PstI site that terminated this ORF (Fig. 1). This same strategy was used to sequence an additional 1.1 kb of DNA that contained both a 414-bp segment that completed the partial ORF found in pHB13 and another complete ORF of 561 nucleotides encoding a protein that was most similar to the CdtC protein of E. coli strain 6468/62 (19).

Characterization of the H. ducreyi cdt Gene Cluster.

Three putative promoters were located upstream from the first ORF but no putative promoters were apparent in front of the second and third ORFs (Fig. 2). A stem-loop structure similar to a rho-independent transcription terminator was located 3′ from the third ORF. The proteins encoded by these three ORFs had calculated molecular masses of 24,662, 31,537, and 20,615 Da, respectively. Consistent with the possible presence of a leader peptide, each of these proteins had a hydrophobic region of ≈15–19 amino acids at the N terminus that was usually preceded by one or two basic amino acids and terminated by a sequence resembling the signal peptidase I consensus. The putative mature forms of these proteins had calculated molecular masses of 23, 29, and 19 kDa. The protein encoded by the first ORF was 38% identical to the E. coli strain 6468/62 CdtA gene product, whereas the proteins encoded by the second and third ORFs were 51% and 24% identical to the CdtB and CdtC proteins, respectively, of this same E. coli strain (19). Accordingly, these three ORFs were designated as the H. ducreyi cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC genes (Figs. 1 and 2).

Nucleotide sequence analysis of H. ducreyi chromosomal DNA extending 3 kb upstream from the cdtABC gene cluster revealed the presence of an incomplete ORF encoding an predicted protein with 36% identity to transposase A (tnpA) from Staphylococcus aureus transposon Tn554 (28). Within 2 kb downstream from cdtABC, we found two incomplete ORFs encoding predicted proteins with similarity to the IstA and IstB proteins that are known to be involved in transposition functions (29) and a complete ORF encoding a predicted protein that was 58% identical to the transposon gamma-delta resolvase (tnpR) (recombinase) from E. coli (30).

Detection of the cdt Gene Cluster in Other H. ducreyi Strains.

PCR was used to amplify 493-bp, 459-bp, and 512-bp segments from the cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC genes, respectively, using H. ducreyi strain 35000 chromosomal DNA as the template. The oligonucleotide primers for these probes were P3 and P6 for cdtA, P10 and P12 for cdtB, and P14 and P18 for cdtC. These three PCR products were used to probe chromosomal DNA from twelve H. ducreyi strains that had been digested with AvaI; an AvaI restriction site was located 261-bp 5′ from the start codon for cdtA. Eleven of the twelve strains possessed a 4.7-kb AvaI fragment that hybridized with the cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC probes whereas a single strain (i.e., 512) hybridized to none of these probes (data not shown).

PCR was used to amplify the cdtABC gene cluster from three of these H. ducreyi strains (RO18, STD102, and HD12). Nucleotide sequence analysis revealed that the cdtABC structural genes of these three strains were identical to those of strain 35000 (data not shown).

Expression of Soluble Cytotoxic Activity by H. ducreyi Strains.

Culture supernatant from H. ducreyi strain 35000 was shown to kill HeLa, HEp-2, and Chinese hamster ovary cells in vitro, as was expected from previous reports describing the soluble cytotoxic activity expressed by the vast majority of H. ducreyi strains (9, 11, 31). Cell death and destruction of the monolayer caused by this H. ducreyi-derived preparation was preceded by progressive distention of the cells that resembled that produced by both E. coli CDT and E. coli heat-labile enterotoxin on Chinese hamster ovary cells (32). This same H. ducreyi supernatant preparation did not kill rat Y-1 adrenal cells that have been reported to be resistant to killing by E. coli CDT (33). Similarly, when culture supernatants from the twelve H. ducreyi strains described above were tested for their relative abilities to kill HeLa cells in vitro, eleven of these, as typified by strain 35000 (Fig. 3A), readily killed HeLa cells. Only the supernatant from H. ducreyi strain 512, whose DNA did not hybridize with the cdt gene probes, was unable to kill these human cells (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Killing of HeLa cells by wild-type and recombinant H. ducreyi cdt gene products. Partial monolayers of HeLa cells (20–30% confluent) in 24-well tissue culture plates were exposed to culture supernatants (A–D) or to bacterial culture medium (E) for 2 hr. The wells were stained and photographed 72 hr later. (A) H. ducreyi strain 35000; (B) H. ducreyi strain 512; (C) E. coli DH5α(pLDC103); (D) E. coli DH5α(pCRII); (E) Luria–Bertani culture medium. (Bar = 50 μm.)

The H. ducreyi cdtABC Gene Cluster Encodes the Soluble Cytotoxin.

The fact that culture supernatant from the single H. ducreyi strain that apparently lacked the cdtABC gene cluster was unable to kill HeLa cells in culture provided circumstantial evidence for the involvement of these genes in expression of the soluble cytotoxic activity of H. ducreyi (9, 31). To address this matter directly, the intact cdtABC gene cluster was amplified from the H. ducreyi strain 35000 chromosome using primers P1 and P19 and cloned into a plasmid vector, yielding the recombinant plasmid pLDC103. Culture supernatant from the recombinant E. coli strain DH5α(pLDC103) readily killed HeLa cells (Fig. 3C) whereas culture supernatant from E. coli DH5α containing only the plasmid vector pCRII had no toxic effect on these cells (Fig. 3D). It should be noted that E. coli strain DH5α(pLDC103) did not bind heme, a finding that indicated that the original heme-binding phenotype of the recombinant clone E. coli RR1(pHB13) involved expression of another H. ducreyi gene(s) present in the 11-kb insert.

Expression of H. ducreyi cdt Gene Products.

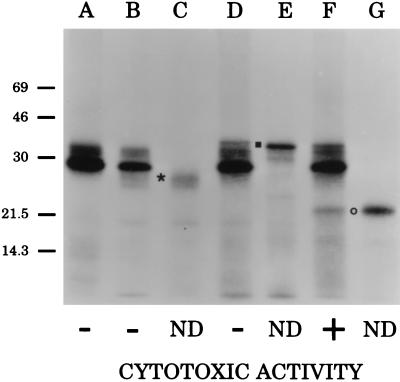

The cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC genes from H. ducreyi strain 35000 were amplified individually by PCR and used in an in vitro coupled transcription/translation system for linear DNA molecules to establish the SDS/PAGE migration characteristics of the protein product of each gene (Fig. 4). Each of these PCR products contained approximately 200-bp of flanking DNA 5′ from the start codon in an attempt to encompass possible promoters preceding each gene, even though putative promoters were not apparent in front of either the cdtB or cdtC gene (Fig. 2). Proteins with apparent molecular masses of 26, 33, and 22 kDa (Fig. 4, lanes C, E, and G) were expressed by the cdtA, cdtB, and cdtC genes, respectively, in this system. These results indicated that each of these three PCR products possessed a promoter(s) that was functional in this in vitro system.

Figure 4.

Fluorographic detection of H. ducreyi CDT proteins expressed in vitro. The H. ducreyi cdtA gene (lane C), the H. ducreyi cdtB gene (lane E), and the H. ducreyi cdtC gene (lane G) were each amplified from the chromosome of H. ducreyi strain 35000 and used in an in vitro coupled transcription/translation system for linear DNA templates to establish the size of the protein product of each gene. The position of CdtA is indicated by ∗, that of CdtB by ▪, and that of CdtC by ○. The vector pCRII (lane A) and recombinant plasmids containing the H. ducreyi cdtA gene (pLDC101, lane B), the H. ducreyi cdtAB gene pair (pLDC102, lane D), and the entire H. ducreyi cdtABC gene cluster (pLDC103, lane F) were used in an in vitro coupled transcription/translation system for circular DNA templates. The HeLa cell killing ability (cytotoxic activity) of culture supernatants from E. coli DH5α-derived recombinant strains containing pLDC101, pLDC102, pLDC103, and the vector plasmid pCRII is indicated. ND, not determined.

Recombinant plasmids containing the H. ducreyi cdtA, cdtAB, and cdtABC genes (pLDC101, pLDC102, and pLDC103, respectively, in Fig. 1) were used in a coupled in vitro protein synthesis system for circular DNA templates to establish that each plasmid was expressing the appropriate CDT proteins (Fig. 4, lanes B, D, and F, respectively). When culture supernatants from these three recombinant E. coli strains were tested for their cytotoxic activity, only the strain expressing all three gene products [DH5α(pLDC103)] (Fig. 4, lane F) was able to kill HeLa cells.

RNA Transcript Analysis.

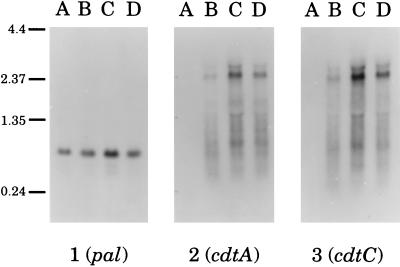

Probes derived from cdtA, from cdtC, and from a gene encoding the conserved 18 kDa lipoprotein (PAL) of H. ducreyi (34) were used in Northern blot analysis of total RNA extracted from three H. ducreyi strains (i.e., 35000, RO18, and STD102) that expressed the soluble cytotoxic activity and the single strain (i.e., 512) that did not express this activity. A 0.7–0.8 kb transcript was detected in all four strains when a pal-specific probe was used (Fig. 5, panel 1, lanes A–D); this is consistent with the size of the H. ducreyi pal ORF (0.5 kb) (34). In contrast, the three strains that produced the soluble cytotoxic activity expressed a 2.4 kb transcript that bound both the cdtA- and cdtC-specific probes (Fig. 5, lanes B–D, panels 2 and 3, respectively); this latter result suggested that the H. ducreyi cdtABC genes constituted a polycistronic operon. The cdtC-specific probe did not detectably hybridize with any smaller transcripts corresponding to transcription initiated from the cdtB or cdtC genes. The single strain that did not elaborate the soluble cytotoxin also did not express a transcript reactive with these cdt-specific probes (Fig. 5, panels 2 and 3, lane A).

Figure 5.

Northern blot analysis of transcripts from the H. ducreyi cdt and pal genes. Total RNA prepared from cells of strain 512 (lane A), 35000 (lane B), RO18 (lane C), and STD102 (lane D) was analyzed with a pal-specific probe (panel 1), a cdtA-specific probe (panel 2), and a cdtC-specific probe (panel 3). Size markers (in kb) are shown on the left side of this figure.

Primer extension analysis revealed two putative transcription start sites immediately 5′ from the beginning of the cdtA gene (nucleotides 413 and 477 in Fig. 2). Primer extensions performed with several oligonucleotide primers complementary to the 5′ regions of the cdtB and cdtC genes did not detect any putative transcription start sites preceding these two genes (data not shown).

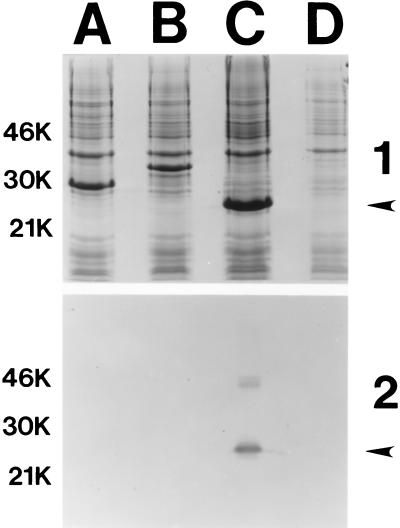

A H. ducreyi Cytotoxin-Neutralizing Antibody Binds a Protein Encoded by the cdtABC Gene Cluster.

To confirm that the H. ducreyi soluble cytotoxin-neutralizing mAb bound a product of the H. ducreyi cdtABC gene cluster, each of the H. ducreyi cdt genes was used to construct a fusion protein, containing six histidine residues at its N terminus, for use in Western blot analysis. All three fusion proteins (His-CdtA, His-CdtB, and His-CdtC) were readily expressed in E. coli (Fig. 6, panel 1, lanes A, B, and C, respectively). The apparent molecular weights of the protein fusions, as determined by SDS/PAGE, correlated with their calculated molecular weights. When these three fusion proteins were probed in Western blot analysis with the cytotoxin-neutralizing mAb, the His-CdtA and His-CdtB fusion proteins (Fig. 6, panel 2, lanes A and B, respectively) were unreactive with this mAb. In contrast, the His-CdtC fusion protein bound this mAb (Fig. 6, panel 2, lane C).

Figure 6.

Western blot-based identification of the H. ducreyi cdt gene product bound by the H. ducreyi cytotoxin-neutralizing mAb. After isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside induction, proteins in recombinant E. coli strains carrying genes encoding the His-CDT fusion proteins were resolved by SDS/PAGE and either stained with Coomassie blue (panel 1) or probed in Western blot analysis with the cytotoxin-neutralizing mAb (panel 2). Lanes: A, His-CdtA; B, His-CdtB; C, His-CdtC; D, vector only. The arrows on the right side of each panel indicate the position of the 22-kDa His-CdtC fusion protein that bound the cytotoxin-neutralizing mAb. Size markers (in kDa) are present on the left side of each panel.

DISCUSSION

The synthesis of a soluble cytotoxic factor by H. ducreyi was reported by Purven and Lagergard (9) several years ago and represented the first description of a potential extracellular virulence factor of this organism. We have now established that this soluble cytotoxic activity is encoded by the H. ducreyi cdtABC gene cluster. These genes encode relatively small (i.e., 20–31 kDa) products that most closely resemble the proteins expressed from the cdtABC gene cluster found in the enteropathogenic E. coli strain 6468/62 (19).

CDT is a novel toxic activity released by some E. coli strains (19, 20, 32), Shigella isolates (22, 35), and many Campylobacter species (21, 23) that causes elongation followed by progressive cellular distention and cytotoxicity with certain mammalian cell lines in vitro (i.e., Chinese hamster ovary, HeLa, HEp-2, and Vero) (33). To date, the cdtABC gene clusters from two E. coli strains (19, 20), Shigella dysenteriae (35), and Campylobacter jejuni (23) have been sequenced. The exact in vivo function of the enteric CDT proteins has not been determined to date, and a primary role for CDT in the pathogenesis of disease caused by these pathogens has not been established (36).

The H. ducreyi cdtABC genes were detected in eleven of twelve H. ducreyi strains tested in Southern blot analysis; the single H. ducreyi strain (i.e., 512) that lacked these genes did not elaborate soluble cytotoxic activity against HeLa cells (Fig. 3B). The involvement of the cdtABC gene cluster in expression of soluble cytotoxic activity by H. ducreyi was confirmed by experiments in which this H. ducreyi gene cluster was introduced into E. coli; the resultant recombinant strain released a cytotoxic activity into culture supernatant (Fig. 3C). It should also be noted that the target cell specificity of the H. ducreyi CDT resembles that of the CDT synthesized by certain E. coli strains in that both of these toxins killed HeLa, HEp-2, and Chinese hamster ovary cells while not affecting rat Y-1 adrenal cells (33).

While nothing is known about which of the enteric CDT proteins is directly involved in cytotoxic activity, we have established, for the first time, that a mAb that neutralizes H. ducreyi CDT activity binds to the product of the cdtC gene (Fig. 6, panel 2, lane C). In addition, we have used the His-CdtC fusion protein as an immunogen to produce additional H. ducreyi CdtC-specific mAbs that have neutralizing activity against the soluble H. ducreyi cytotoxin and that bind to the CdtC protein in H. ducreyi culture supernatant (data not shown).

Similar to the products of the E. coli cdtABC genes, the three protein products of the H. ducreyi cdtABC gene cluster also appear to have leader peptides (Fig. 2). The fact that the cytotoxin-neutralizing mAb bound to the His-CdtC fusion protein indicated that the cdtC gene product is present in H. ducreyi culture supernatant and directly involved in cytotoxic activity. Whether the products of the H. ducreyi cdtA and cdtB genes are present in the periplasmic space, the outer membrane, or released from the bacterial cell remains to be determined. It is possible that CdtA and CdtB may be cell-bound and required for release or activation of the CdtC protein. At this time, we also cannot eliminate the possibility that CdtA and CdtB are released from the H. ducreyi cell and that the CdtC protein is bound to either the CdtA protein or the CdtB protein, or both, to form the active cytotoxin.

Northern blot analysis of total RNA from H. ducreyi cells indicated that the cdtABC gene cluster likely constitutes a polycistronic operon (Fig. 5). Whether expression of these genes is constitutive or regulated at some level obviously will require more extensive analyses. Interestingly, when a linear form of each gene was used in a DNA-directed transcription/translation system, a protein product was obtained in each instance (Fig. 4), even though promoters were not apparent in front of the cdtB and cdtC genes (Fig. 2) and primer extension analysis of RNA from H. ducreyi cells did not detect transcription start sites in front of the cdtB and cdtC genes. These results suggest that, within the artificial environment of this in vitro system, the linear forms of both the cdtB and cdtC genes contain a region(s) that can function as a promoter.

The origin of the cdtABC gene cluster in H. ducreyi is open to speculation. The presence of closely related gene products in several enteric pathogens indicates that it is likely that the H. ducreyi cdtABC genes were acquired from another organism. What mechanism(s) was involved in this gene transfer cannot be determined from the available data. However, our discovery of genes (or gene fragments) likely involved in transposition (i.e., the tnpA, istA, istB, and tnpR homologs) in the H. ducreyi chromosome within 3 kb on either side of the cdtABC gene cluster raises the possibility that this gene cluster was introduced into H. ducreyi as part of a transposon. We have also established that the H. ducreyi CDT-neutralizing mAb used in this study does not neutralize CDT activity expressed by E. coli strain 6468/62 (data not shown), a finding that indicates that the epitope recognized by this mAb is absent from the E. coli CdtC protein.

The mechanism by which H. ducreyi CDT exerts cytotoxic activity is also not known at this time. It should be noted that the 122 kDa cell-associated H. ducreyi hemolysin has recently been shown to be responsible for killing human foreskin fibroblasts in vitro (13, 14) and this killing appears to require the binding of H. ducreyi to the human foreskin fibroblasts cells (14, 37). Moreover, an isogenic hemolysin-negative H. ducreyi mutant killed HeLa cells as effectively as did the wild-type parent strain (13). Because culture supernatant from this hemolysin-negative H. ducreyi mutant also killed HeLa cells (data not shown), it is now clear that H. ducreyi produces at least two different cytotoxic proteins.

What role may be played by H. ducreyi CDT in the development or persistence of genital ulcers remains to be determined. When one considers that cell death is involved in the development of ulcers, the elaboration of this cytotoxin by H. ducreyi may be very relevant. Moreover, the multifactorial nature of bacterial virulence makes it likely that H. ducreyi CDT may function in concert with other potential virulence factors of this organism including the hemolysin and lipooligosaccharide to kill cells or otherwise damage the integrity of the dermis. In this regard, it will be important to determine whether the few isolates of H. ducreyi that lack the ability to express CDT activity are any less virulent than the CDT-expressing strains that comprise the vast majority of isolates of this pathogen (11). Fortunately, the recent introduction of an experimental human model for H. ducreyi infection (38) has opened the way for direct investigation of the contribution of selected H. ducreyi gene products to the processes of infection and ulceration. Current efforts in this laboratory are directed toward obtaining an isogenic H. ducreyi cdt mutant for evaluation in this human model. Mutant analysis, together with studies of the mechanism of action of purified H. ducreyi CDT, should allow determination of the true importance of this cytotoxin in the pathogenesis of chancroid.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Almond and Leon Eidels for helpful discussions and Allan Ronald, Patricia Totten, Linda Parsons, Thomas Oberhofer, and E. Sng for supplying the H. ducreyi isolates used in this study. We also thank James B. Kaper for supplying E. coli strain 6468/62 and the recombinant E. coli strain DH5α(pDS7.96). This study was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant AI32011 (to E.J.H. and J.D.R.). M.K.S. was the recipient of a National Research Service Award (F32-AI08848).

ABBREVIATION

- CDT

cytolethal distending toxin

Footnotes

References

- 1.Trees D L, Morse S A. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:357–375. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.3.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ronald A R, Albritton W L. In: Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Holmes K K, Mardh P-A, Sparling P F, Wiesner P J, editors. New York: McGraw–Hill; 1990. pp. 263–271. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron D W, Simonsen J N, D’Costa L J, Ronald A R, Maitha G M, Gakinya M N, Cheang M, Piot P, Brunham R C, Plummer F A. Lancet. 1989;ii:403–408. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90589-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plummer F A, Wainberg M A, Plourde P, Jessamine P G, D’Costa J L, Wamola I A, Ronald A R. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:810–811. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Odumeru J A, Wiseman G M, Ronald A R. J Med Microbiol. 1987;23:155–162. doi: 10.1099/00222615-23-2-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alfa M J, DeGagne P, Hollyer T. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1735–1742. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1735-1742.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Totten P A, Lara J C, Norn D V, Stamm W E. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5632–5640. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5632-5640.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lammel C J, Dekker N P, Palefsky J, Brooks G F. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:642–650. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Purven M, Lagergard T. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1156–1162. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1156-1162.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagergard T, Purven M. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1589–1592. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1589-1592.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purven M, Falsen E, Lagergard T. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;129:221–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brentjens R J, Ketterer M, Apicella M A, Spinola S M. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:808–816. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.808-816.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmer K L, Goldman W E, Munson R S., Jr Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:13–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alfa M J, DeGagne P A, Totten P A. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2349–2352. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2349-2352.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens M K, Porcella S, Klesney-Tait J, Lumbley S R, Thomas S E, Norgard M V, Radolf J D, Hansen E J. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1724–1735. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1724-1735.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elkins C. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1241–1245. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1241-1245.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campagnari A A, Wild L M, Griffiths G, Karalus R J, Wirth M A, Spinola S M. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2601–2608. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2601-2608.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lagergard T. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:87–92. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)88888-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott D A, Kaper J B. Infect Immun. 1994;62:244–251. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.244-251.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pickett C L, Cottle D L, Pesci E C, Bikah G. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1046–1051. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.3.1046-1051.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson W M, Lior H. Microb Pathog. 1988;4:115–126. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson W M, Lior H. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;48:235–238. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pickett C L, Pesci E C, Cottle D L, Russell G, Erdem A N, Zeytin H. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2070–2078. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2070-2078.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Purcell B K, Richardson J A, Radolf J D, Hansen E J. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:359–367. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.2.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd Ed. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gray-Owen S D, Loosmore S, Schryvers A B. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1201–1210. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1201-1210.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy E, Huwyler L, do Carmo de Freire Bastos M. EMBO J. 1985;4:3357–3365. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown H J, Stokes H W, Hall R M. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4429–4437. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4429-4437.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reed R R, Shibuya G I, Steitz J A. Nature (London) 1982;300:381–383. doi: 10.1038/300381a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lagergard T. Microb Pathog. 1992;13:203–217. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90021-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson W M, Lior H. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;43:19–23. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90131-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson W M, Lior H. Microb Pathog. 1988;4:103–113. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(88)90052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spinola S M, Hiltke T J, Fortney K, Shanks K L. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1950–1955. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.1950-1955.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okuda J, Kurazono H, Takeda Y. Microb Pathog. 1995;18:167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(95)90022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albert M J, Faruque S M, Faruque A S G, Bettelheim K A, Neogi P K B, Bhuiyan N A, Kaper J B. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:717–719. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.3.717-719.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alfa M J. J Med Microbiol. 1992;37:43–50. doi: 10.1099/00222615-37-1-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spinola S M, Wild L M, Apicella M A, Gaspari A A, Campagnari A A. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1146–1150. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]