Abstract

Aim

Whether a prostate cancer diagnosis induces response shift has not been established so far. Therefore, we assessed response shift in men who were diagnosed with localized prostate cancer.

Patients and methods

Out of 3,892 men who completed a questionnaire before screening, 82 were subsequently diagnosed with prostate cancer. Response shift was assessed in 52 (response 63%) by the then-test (EuroQol self-rating of health, Short-Form 36 mental health and vitality) and a novel method: rating of vignettes relating to side effects of prostate cancer treatment (urinary, bowel and erectile dysfunction). Three then-tests were conducted: two referencing pre-diagnosis (measured pre- and post-treatment), and one referencing pre-treatment (measured post-treatment).

Results

Then-test scores of pre-diagnosis health were significantly higher than original scores, indicating a more positive judgement in retrospect. Then-test scores of pre-treatment health were lower than original scores. Especially the vignette on erectile dysfunction was rated less bad after diagnosis versus before (P < 0.001, moderate effect size).

Conclusions

We found evidence for response shift in men who were diagnosed with prostate cancer. Men evaluated urinary, bowel, and erectile dysfunction as less bad after they had become patients who can expect to experience these side effects. The rating of vignettes is a promising additional technique to assess response shift.

Keywords: Patient-reported outcome, Prostate cancer, Quality of life, Response shift

Introduction

Response shift, defined as an adaptation to changing health [1], is a beneficial process for patients because it can help in adapting to a new situation. However, it may complicate the correct interpretation of change in health-related quality of life (QoL) scores over time in intervention studies, and therefore needs to be understood. Response shift refers to a change in the meaning of QoL over time [2] and can result from a change in one’s internal standards of measurement (i.e. recalibration), a change in the importance attributed to the domains constituting QoL (i.e. change in values or reprioritization), or a change in the definition of the concept of QoL (i.e. reconceptualization) [3, 4]. These three forms of response shift are illustrated in the following example. Imagine a woman X. When asked to rate her QoL she thought of her (50-h a week) job, her partner and playing volleyball with friends, and rated her QoL as very good. Unfortunately she fell ill. For some months she was not able to work. Her partner and relatives supported her a great deal, which she appreciated enormously. Gradually she recovered and started working again for 20 h a week, but was no longer able to play volleyball. She rated her new QoL again as very good, but this time the main aspects of her QoL consisted of her partner, her family and work. Her ratings did not change, i.e. twice ‘very good’, but in fact three forms of response shift had occurred. ‘Work’ changed from a 50-h a week job to 20 h a week (recalibration), her partner became more important (reprioritization), and her concept of QoL has changed: no more sports, but relatives instead (reconceptualization).

This paper focuses on the assessment of response shift induced by a prostate cancer diagnosis. Schwartz and colleagues systematically addressed the state-of-the-art in the assessment and interpretation of response shift [5]. In a meta-analysis, following Cochrane guidelines, the magnitude and clinical relevance of response shifts across 19 longitudinal studies were evaluated. Most studies addressed global QoL and specific QoL domains such as fatigue, well-being, and pain, usually by conducting the then-test. Effect sizes, defined as the mean difference between tests divided by the standard deviation (SD) of the first assessment, were computed by the authors. These were generally small according to Cohen’s criteria [6], with the largest effect sizes found for fatigue, followed by global QoL, physical role limitation, physical well-being, and pain. Effect sizes varied in direction, which complicated their interpretation. Schwartz et al. concluded with recommendations for future response shift publications, such as explaining the meaning of the study results in terms of recalibration, reprioritization, and reconceptualization [5].

Response shift is more likely to occur when an intense and pervasive change in health is experienced [7]. A cancer diagnosis may have a large impact on a person’s experienced health. Our group previously described the process of being diagnosed with prostate cancer through a screening process consisting of a Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) test and, if indicated, a biopsy. Typically, localized prostate cancer diagnosed through screening is not associated with any physical symptoms. Men’s mental health and the valuation of their own health decreased significantly after they received their diagnosis, and we concluded that being diagnosed with prostate cancer was a deeply felt change in health [8]. We started the present study because we expected that a prostate cancer diagnosis induces response shift. We hypothesized that the pre-diagnosis health state would be rated more positively in retrospect (i.e. if assessed after diagnosis) than at the reference point itself (i.e. pre-diagnosis).

Collecting data on QoL before a cancer diagnosis is usually not feasible, since it is unknown who will develop cancer and when, so that the inclusion of a very large cohort would be required. However, the context of the European Randomized study for Screening on Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) [9] enabled us to include a cohort of men shortly before they were screened and subsequently diagnosed. We aimed at assessing the magnitude and direction of response shift effects after diagnosis and again after primary treatment. We employed two methods: the common then-test and a novel approach including rating of vignettes related to side effects of prostate cancer treatment (urinary, bowel, and erectile dysfunction).

Patients and methods

Ethics approval and informed consent

The Ethics Committee of the Erasmus MC approved the research protocol. All participants gave additional written informed consent to be interviewed for the study.

Parent study

Inclusion of the ERSPC participants was initiated in 1994 among all male inhabitants of the Rotterdam region aged between 55 and 74 years. The only exclusion criterion was a previous prostate cancer diagnosis. Details on study recruitment for the ERSPC have been reported earlier [9].

Respondents

Randomly selected participants from the parent study were approached. All men who were due for the second (n = 2,798) or third screening round (n = 2,024) between January 2003 and May 2004 were sent a short questionnaire on health (see below) by mail. Men who were diagnosed through the screening process were interviewed twice by one of the authors (IK); one month post-diagnosis (but before treatment) and again 7 months post-diagnosis.

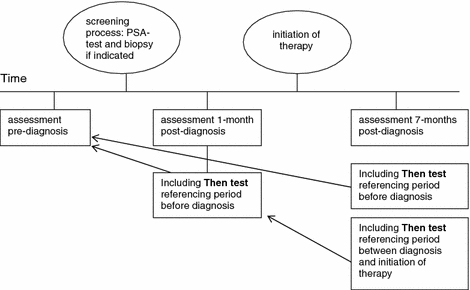

Assessing response shift

To assess the magnitude and direction of response shift effects two methods were used: the then-test, and vignettes (a novel method in response shift research). For the resulting study scheme, see Fig. 1.

The then-test is a retrospective evaluation of an earlier assessment (retrospective pre-test-post-test design). At post-test respondents are asked to remember how they were doing at the reference point and to retrospectively rate their level of functioning or QoL at that time. The then-test was originally developed to measure recalibration. The method assumes that respondents will use their post-test internal standards when providing a re-evaluation or ‘then-test’ rating of their health at the reference point [5]. The comparison between the then-test and the post-test is thus assumed not to be confounded by recalibration and can be considered as an indication of true change [2]. The comparison of the mean pre-test, which is the assessment that was completed at the reference point, and then-test scores would reflect an estimate of the magnitude and direction of response shift [2]. Because respondents in our study were included before diagnosis, they could provide then-test scores relating to their health before diagnosis and to their health between diagnosis and treatment. Before completing the then-test, respondents were explicitly reminded about the period the then-test was referring to: e.g. the time when the respondents had not yet been diagnosed with prostate cancer and were unaware of having prostate cancer. Respondents were then asked to re-assess their health at that time. Three then-tests were conducted: two referencing pre-diagnosis health (measured at 1 month post-diagnosis and 7 months post-diagnosis) and one referencing 1-month post diagnosis health (measured at 7-months post-diagnosis), see Figs. 2, 3, 4. The respondents completed generic QoL measures, i.e. the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) mental health and vitality, and the EQ-5D VAS for self-rated health, as a pre-test, post-test and then-test. The SF-36 consists of eight scales on physical and mental domains of health. We used the scales on mental health (five items on being nervous, down, peaceful, depressed and happy) and vitality (four items on being full of life, having a lot of energy, being worn out and tired). Higher scores (0–100) indicate better mental health and vitality [10]. The EuroQol (EQ) 5D valuation of own health is a visual analog scale on current overall health, anchored at the lower end (0) by ‘worst imaginable health state’ and at the upper end (100) by ‘best imaginable health state’ [11].

As a novel method to assess response shift we used vignettes that each described a health state relating to side effects of therapy for localized prostate cancer, i.e. urinary, bowel or erectile dysfunction. The vignettes contained items of the EQ-5D self-classifier complemented with items on dysfunction, for instance, ‘Mr. A has no problems in walking about, has no problems washing or dressing himself, experiences urinary leakage daily, has no pain or discomfort, is not anxious or depressed’. Respondents were asked to indicate how good or bad they evaluated these health states on visual analog scales anchored at the lower end (0) by ‘very bad’ and at the upper end (10) by ‘very good’. We used the vignettes to explore reprioritization. We hypothesized that men would value the health states as less detrimental after diagnosis than before. After diagnosis they knew they might experience these dysfunctions themselves in the context of prostate cancer treatment.

Additionally, information on respondents’ age and on the Gleason score (a clinical criterion for histological grading of the aggressiveness of the tumour) were obtained through the screening office.

Fig. 1.

Study scheme

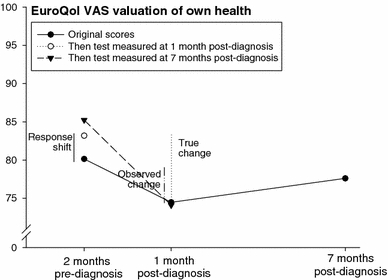

Fig. 2.

Original and then-test scores of the EuroQol valuation of own health by prostate cancer patients (n = 52). If we measure only EQ-VAS preceding diagnosis and at 1-month post-diagnosis, the difference between these scores is regarded the ‘observed change’. However, if the retrospective pre-diagnosis assessment provides a more valid comparison with the post-diagnosis assessment, the ‘true change’ is reflected by the difference between the retrospective pre-diagnosis assessment and the post-diagnosis assessment. The difference between the pre-diagnosis assessment and the retrospective pre-diagnosis assessment provides an indication of the size and direction of the ‘response shift’ induced by the diagnosis. Similar explanations are valid for the other data points in the figure

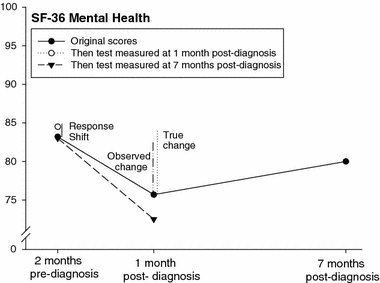

Fig. 3.

Original and then-test scores of the SF-36 mental health by prostate cancer patients (n = 52). ‘Observed change’, ‘True change’ and ‘Response shift’ refer to the differences in SF-36 mental health scores between the assessment at 2 months before diagnosis and post- and then-test at 1 month after diagnosis (for further explanation, see caption at Fig. 2.)

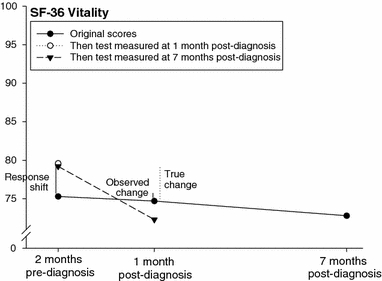

Fig. 4.

Original and then-test scores of the SF-36 vitality by prostate cancer patients (n = 52). ‘Observed change’, ‘True change’ and ‘Response shift’ refer to the differences in SF-36 vitality scores between the assessment at 2 months before diagnosis and post- and thentestthen-test at 1 month after diagnosis (for further explanation, see caption at Fig. 2.)

Statistical analysis

Procedures concerning imputation of missing responses in the SF-36 items were conducted according to the guidelines of the SF-36 Health Survey Manual [12]. Differences between assessments were tested with paired-samples t-tests. P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The type I error rate, i.e. the ratio of significant findings to the number of comparisons, was calculated. To assess the magnitude of the differences between the assessments we used Cohen’s effect sizes, defined as the mean difference between tests divided by the SD of the first assessment, and interpreted as follows: 0.2 < d < 0.5 indicates a small, 0.5 ≤ d < 0.8 a moderate, and d ≥ 0.8 a large effect size [6].

The minimal important difference (MID), which is the smallest change in a patient-reported outcome that is perceived by patients as beneficial or that would result in a change of treatment, was operationalized as a difference of at least half a SD [13].

Non-response bias was analysed by testing differences between the respondents and the non-respondents with unpaired t-tests.

Results

Out of the 3,892 men who completed the initial questionnaire before screening on prostate cancer, 82 were subsequently diagnosed. Of these, 52 (response 63%) consented to participate in two additional telephone interviews at 1 and at 7 months post-diagnosis. All 52 respondents participated in the first interview, which took place before treatment had been initiated. Due to personal circumstances one respondent later refused the second telephone interview. Average age at screening was 67.3 years (SD 4.4), ranging from 60 to 74 years. The Gleason score was favourable in 42 of the 52 patients, i.e. below seven (Table 1). In all respondents but one, treatment had been initiated at 7 months post-diagnosis, i.e. radical prostatectomy (n = 25), brachytherapy (n = 12), active surveillance (n = 10), external radiotherapy (n = 3), or hormonal treatment (n = 1), see Table 1.

Table 1.

Gleason scores and treatment modality of the respondents (n = 52)

| Gleason score < 7 n = 42 | Gleason score ≥ 7 n = 10 | Total n = 52 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radical prostatectomy | 18 | 7 | 25 |

| External radiotherapy | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Brachytherapy | 13 | 13 | |

| Active surveillance | 9 | 9 | |

| Hormonal treatment | 1 | 1 | |

| No treatment choice yet | 1 | 1 |

Original scores, i.e. scores relating to the respondents’ health at the time of the assessment and interviews, and then-test scores relating to the two reference points are given in Table 2. For example, ‘85.2’ in the upper right corner of Table 2 reflects the ‘EQ valuation of own health’ score of the then-test measured at 7 months post-diagnosis referencing 2 months pre-diagnosis. Mental and self-rated health scores worsened significantly from 2 months preceding diagnosis to 1 month post-diagnosis. The average mental health score, for instance, was 83.2 at 2 months pre-diagnosis, and 75.8 at 1-month post-diagnosis; a decrease of 7.4 that exceeds the MID. At 7 months post-diagnosis mental and own health scores had increased again, but not to their original level.

Table 2.

Mean health scores (standard deviation) of the respondents (n = 52) before and after diagnosis, original and thentests scores

| Referring to | Original scores (n = 52) | P-value* | Thentests | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month post-diagnosis (n = 52) | P-value: thentest vs. original | Effect size: thentest vs original | 7 months post-diagnosis (n = 51) | P-value: thentest vs. original | Effect size: thentest vs. original | |||

| 2 months pre-diagnosis | ||||||||

| EuroQol own health | 80.2 (11.7) | 83.2 (9.0) | 0.058 | −0.26 | 85.2 (7.6) | 0.002a | −0.43 | |

| SF-36 mental health | 83.2 (11.6) | 84.5 (11.0) | 0.304 | −0.10 | 83.2 (10.9) | 1.00 | 0.01 | |

| SF-36 vitality | 75.3 (15.6) | 79.6 (12.0) | 0.008 | −0.28 | 79.4 (12.4) | 0.046 | −0.26 | |

| 1 month post-diagnosis, before initiation of treatment | ||||||||

| EuroQol own health | 74.5 (15.1) | 0.010 | 74.1 (14.5) | 0.618 | 0.03 | |||

| SF-36 mental health | 75.8 (16.8) | 0.001a | 72.8 (18.3) | 0.042 | 0.17 | |||

| SF-36 vitality | 74.7 (14.2) | 0.771 | 72.6 (13.7) | 0.111 | 0.15 | |||

| 7 months post-diagnosis, after intiation of treatment in 80% of respondents | ||||||||

| EuroQol own health | 77.6 (13.7) | 0.196 | ||||||

| SF-36 mental health | 80.4 (13.8) | 0.066 | ||||||

| SF-36 vitality | 73.1 (17.7) | 0.213 | ||||||

*P-value of difference with previous original score (P ≤ 0.05 are considered significant)

aChange exceeds the minimal important difference (operationalised as ½ standard deviation)

Original scores of pre-diagnosis health were lower, indicating worse health than on the then-test scores. For example, the original pre-diagnosis mental health score was 83.2 on average, but the then-test score measured at 1 month post-diagnosis was 84.5, indicating a more positive judgement of pre-diagnosis mental health in retrospect. Original scores of health between diagnosis and treatment, on the other hand, were higher, indicating better health than on the then-test scores. The original vitality score, for instance, was 74.7 at 1 month post-diagnosis, but the then-test score measured at 7 months post-diagnosis was 72.6. This means that vitality between diagnosis and treatment was judged worse when measured in retrospect than when measured at the reference point itself. Original and then-test scores are presented in Figs. 2–4, including estimates of the response shift effects, i.e. the difference between mean pre-test and then-test scores, and estimates of ‘true’ change, i.e. the difference between the mean post-test and then-test scores.

Effect sizes of the differences between then-test and original scores were small (Table 2).

The vignettes describing urinary, bowel and erectile dysfunction states were rated significantly higher (i.e. better) by respondents at 1 month post-diagnosis than at 2 months pre-diagnosis (P-values 0.038, 0.011, and <0.001, respectively). The valuation of erectile dysfunction showed the largest increase; i.e. from 5.3 to 6.7 on a 0–10 scale, with a moderate effect size of 0.57 (Table 3). This implies that respondents considered especially erectile dysfunction less detrimental after diagnosis with prostate cancer than before diagnosis. The differences between pre- and post-diagnosis valuations of the vignettes exceeded the MID in 4 out of 6 cases (Table 3).

Table 3.

Average valuation by VAS (SD) of prostate cancer specific vignettes, scale 0-10, P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant

| Health state description | Pre-diagnosis (n = 52) | 1 month post-diagnosis (n = 52) | P-value pre-diagnosis vs. 1 month post-diagnosis | Effect size pre-diagnosis vs. 1 month post-diagnosis | 7 months post diagnosis (n = 51) | P-value pre-diagnosis vs. 7 months post-diagnosis | Effect size pre-diagnosis vs. 7 months post-diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily urinary leakage | 5.6 (2.1) | 6.3 (1.5)a | 0.038 | −0.32 | 5.9 (1.5) | 0.348 | −0.14 |

| Daily bowel cramps | 5.3 (2.0) | 6.0 (1.6) | 0.011 | −0.41 | 6.2 (1.4)a | 0.012 | −0.39 |

| Serious erectile dysfunction | 5.3 (2.2) | 6.7 (1.8)a | <0.001 | −0.57 | 6.5 (1.8)a | 0.005 | −0.47 |

achange compared to previous score exceeds minimal important difference

The results of the then-test were significant in 4 out of 9 comparisons, the results of the vignettes in 5 out of 6. The overall type I error rate, which is the ratio of significant findings to the number of comparisons, was 0.6 (9 out of 15).

Non-response analysis

The baseline average age in men who were diagnosed with prostate cancer but did not respond to the questionnaire (n = 30) was 66.7 (SD 4.3, range 59–73) years. Respondents and non-respondents did not differ significantly in age or other health measures (data not shown).

Discussion

Men diagnosed with prostate cancer evaluated their pre-diagnosis health in retrospect as better than at the reference point itself. Post-diagnosis–pre-treatment health was rated worse in retrospect than at the reference point. This suggests that ‘true’ changes in health between the first assessment before diagnosis and the second one at 1 month post-diagnosis were larger than the original scores disclosed, and that response shifts were induced by first, the diagnosis, and second, subsequent treatment. The sizes of the response shifts induced by the diagnosis were larger than those induced by the treatment. The negligible to small effect sizes indicated that only some recalibration occurred. The directions of the effect sizes were interpretable and consistent with our hypotheses.

Additionally, men evaluated vignettes relating to side effects of prostate cancer treatment as less detrimental after they were diagnosed than before diagnosis. We interpreted this change as a reprioritization of respondents who became aware after being diagnosed with prostate cancer that they were at risk of experiencing these health states themselves as a consequence of being treated for prostate cancer. In this new context dysfunctional health states were evaluated as less bad than before. The effect sizes were moderate for erectile dysfunction and small in the two other ones, indicating that reprioritization also occurred. The directions of the effect sizes were interpretable and consistent with our hypotheses.

The overall type I error rate was 0.6, which indicated that the statistical significance is very unlikely to be caused by chance. This is an additional indication that our findings reflect real differences. We conclude that the results of the then-tests and the ratings of the vignettes both indicate the presence of a response shift and adaptation of the patients to their new situation.

In the meta-analysis of Schwartz et al., the largest effect sizes on response shift (although still small) were found for the dimensions global QoL and fatigue [5]. These dimensions, represented in our study by EQ-5D on own health and the SF-36 vitality scale respectively, also resulted in small effect sizes.

An important criticism of the then-test approach is its susceptibility to recall bias. Respondents are supposed to be able to remember their previous health at the reference point, which is extremely difficult in case of a chronic disease with no obvious trend towards better or worse health [14]. However, in a study on response shift in cancer patients undergoing various forms of treatment, there was evidence that recall bias was absent [2]. We assume that in the case of a deeply felt change in health (such as being diagnosed with cancer or the initiation of cancer therapy) recall will not cause memory difficulties for most respondents. Therefore, in our study we expect that recall bias did not have a major influence on the results.

The then-test results in a retrospective judgement that subsequently is used to construct ‘real change’ since the reference point. This approach assumes that the information that was acquired after the original judgment was made leads to more accurate estimates of QoL than the original judgment itself. This assumption is, however, not always true; for example in the case that the newly acquired information is not correct [14].

The valuation of disease-specific vignettes (the second method used to assess response shift) has to our knowledge not been described before. It resulted in a moderate effect size considering the vignette on erectile dysfunction. The directions of the effect sizes were consistent with our hypotheses. Our results showed that response shift can be studied by using vignettes. We consider the valuation of vignettes as a useful addition to the already available collection of tools to assess response shift. Apart from this theoretical value, the results of the vignettes may also have implications for clinical practice. In case of a diagnosis of localized prostate cancer several treatment options are available. Since there is no consensus about which of these treatments has the best outcome in terms of survival and QoL, considerations of patient preferences regarding mode of treatment and side effects are an essential element in shared decision making on the choice of therapy. To elicit a patient’s preferences and his individual trade-offs between benefits and side effects of various modes of treatment, vignettes can be useful [15].

However, our study showed that patient preferences may change in the course of the diagnostic and treatment process, which illustrates how difficult it is for a patient to imagine the consequences of an intervention in advance. This finding confirms the point made by Cowen et al. to recommend the use of individual utilities (“actually prefer”) instead of population’s utilities (“should prefer”) to optimise the choice of treatment for patients with prostate cancer [16].

We recommend further investigation of the vignettes method. The fact that being diagnosed with prostate cancer was found to induce response shift may be seen as an indication that men regard a prostate cancer diagnosis as a major life event, and is additional evidence for earlier findings [8].

In another study, men with metastic or locally advanced prostate cancer completed assessments on prostate symptoms shortly after diagnosis, and 3 and 6 months thereafter. The second and third assessments included then-tests. The presence of a response shift was suggested in patients and their spouses [17, 18]. The authors remarked that retrospective and prospective assessments cannot be used interchangeably.

Lepore and Eton tested two conceptual models of response shift among men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer to explain the frequently observed lack of association between health problems and QoL in cancer patients. No support was found for the suppressor model, according to which health change leads to response shift, which in turn leads to a change in QoL. Some evidence was found for the buffering model, according to which response shift effects moderate the negative association between health problems and QoL. Two aspects of response shift, recalibration and reprioritization, were assessed by then-tests and a measure of primary life goal changes, respectively. They were found to moderate the relation between negative changes in physical health and changes in QoL [19].

Indications of response shift were also found in an earlier study on men treated for localized prostate cancer. Men stated, for instance, that they accepted the side effects of treatment because ‘If they hadn’t intervened, that operation, maybe I wouldn’t be here anymore’ [20].

The present study has several strengths and limitations. The study design is one of its strengths; the unique context of the ERSPC enabled the inclusion of respondents before they (or anyone else) were aware that they had prostate cancer, which is usually unfeasible. To our knowledge this is the first study to measure response shift in men who were diagnosed with cancer. An additional strength is the compliance of the respondents; 51 of the 52 respondents completed the 7-month assessment.

For the then-test we selected measures that are considered subjective (i.e. SF-36 mental health and vitality, and EQ-5D of own health) but no objective items, which can be considered a drawback of the study. Furthermore, we acknowledge that offering questionnaires in two different modes (self-administered questionnaires before diagnosis vs. telephone interviews afterwards) may have been less than optimal. This design was chosen based on practical considerations, because assessments by telephone in 3,892 screen participants was not feasible, and self-administered questionnaires at 1 month after diagnosis undesirable since we wanted these assessments to be completed before the initiation of treatment. The unavailability of information on marital status and education is also a drawback. Another potential limitation of our study is that the interval between the initiation of treatment and the assessment at 7-months post-diagnosis was not the same for all respondents; it is possible that response shift may vary according to the length of time that elapsed since treatment. However, information on this interval had been of limited use. The most common therapies for localized prostate cancer nowadays are surgery, radiotherapy, and active surveillance. These therapies differ greatly (by nature) in duration, the onset of side effects and their course over time.

It may be that particular groups may be more prone to response shift than others, e.g. depending on age or prognosis. We plan to address this issue further, preferably in a larger sample than used in the current study.

Conclusions

Using two complementary techniques we found that a diagnosis of prostate cancer induces response shift. From a methodology point of view, the vignette-method needs to be explored further.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients for their participation in the study, and the urology screening office of the Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam for their friendly cooperation. This study was financed by the Dutch Cancer Society (EUR 2000-2329).

References

- 1.Schwartz, C., & Sprangers, M. (2000). Adaptation to changing health: Response shift in quality-of-life research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- 2.Visser, M. R., Oort, F. J., & Sprangers, M. A. (2005). Methods to detect response shift in quality of life data: A convergent validity study. Quality of Life Research, 14(3), 629–639. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Schwartz, C. E., & Sprangers, M. A. (1999). Methodological approaches for assessing response shift in longitudinal health-related quality-of-life research. Social Science & Medicine, 48(11), 1531–1548. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Sprangers, M. A., & Schwartz, C. E. (1999). Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: a theoretical model. Social Science & Medicine, 48(11), 1507–1515. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Schwartz, C. E., Bode, R., Repucci, N., Becker, J., Sprangers, M. A., & Fayers, P. M. (2006). The clinical significance of adaptation to changing health: A meta-analysis of response shift. Quality of Life Research, 15(9), 1533–1550. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press.

- 7.Sprangers, M. A., Moinpour, C. M., Moynihan, T. J., Patrick, D. L., & Revicki, D. A. (2002). Assessing meaningful change in quality of life over time: A users’ guide for clinicians. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 77(6), 561–571. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Korfage, I. J., de Koning, H. J., Roobol, M., Schroder, F. H., & Essink-Bot, M. L. (2006). Prostate cancer diagnosis: The impact on patients’ mental health. European Journal of Cancer, 42(2), 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Roobol, M. J., Kirkels, W. J., Schroder, F. H. (2003). Features and preliminary results of the Dutch centre of the ERSPC (Rotterdam, the Netherlands). BJU International, 92(Suppl 2), 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Ware, J. E., & Kosinski, M. (2001). Interpreting SF-36 summary health measures: A response. Quality of Life Research, 10(5), 405–413 discussion 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Brooks, R. (1996). EuroQol: The current state of play. Health Policy, 37(1), 53–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Ware, J. E. J., Snow, K. K., Kosinski, M., & Gandek, B. G. (1993). SF-36 health survey: Manual and interpretation guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center.

- 13.Norman, G. R., Sloan, J. A., & Wyrwich, K. W. (2003). Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Medical Care, 41(5), 582–592. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Norman, G. (2003). Hi! How are you? Response shift, implicit theories and differing epistemologies. Quality of Life Research, 12(3), 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Kramer, K. M., Bennett, C. L., Pickard, A. S., Lyons, E. A., Wolf, M. S., McKoy, J. M., et al. (2005). Patient preferences in prostate cancer: A clinician’s guide to understanding health utilities. Clinical Prostate Cancer, 4(1), 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Cowen, M. E., Miles, B. J., Cahill, D. F., Giesler, R. B., Beck, J. R., & Kattan, M. W. (1998). The danger of applying group-level utilities in decision analyses of the treatment of localized prostate cancer in individual patients. Medical Decision Making, 18(4), 376–380. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Rees, J, Waldron, D., O’Boyle, C., Ewings, P., & MacDonagh, R. (2003). Prospective vs retrospective assessment of lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with advanced prostate cancer: the effect of ‘response shift’. BJU International, 92(7), 703–706. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Rees, J., Clarke, M. G., Waldron, D., O’Boyle, C., Ewings, P., & MacDonagh, R. P. (2005). The measurement of response shift in patients with advanced prostate cancer and their partners. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 3, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Lepore, S. J., & Eton, D. T. (2000). Response shifts in prostate cancer patients: an evaluation of suppressor and buffer models. In C. E. Schwartz & M. A. G. Sprangers (Eds.), Adaptation to changing health, response shift in quality-of-life research. Washington DC.

- 20.Korfage, I. J., Hak, T., de Koning, H. J., & Essink-Bot, M. L. (2006). Patients’ perceptions of the side-effects of prostate cancer treatment–a qualitative interview study. Social Science & Medicine, 63(4), 911–919. [DOI] [PubMed]