Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the relationship of myelin content, axonal density, and gliosis with the fraction of macromolecular protons (fB) and T2 relaxation of the macromolecular pool (T2B) acquired using quantitative magnetization transfer (qMT) MRI in postmortem brains of subjects with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Materials and Methods

fB and T2B were acquired in unfixed postmortem brain slices of 20 subjects with MS. The myelin content, axonal count, and severity of gliosis were all quantified histologically. t-Tests and multiple regression were used for analysis.

Results

MR indices obtained in unfixed postmortem MS brains were consistent with in vivo values reported in the literature. A significant correlation was detected between Tr-myelin (inversely proportional to myelin content) and 1) fB (r = -0.80, P < 0.001) and 2) axonal count (r = -0.79, P < 0.001). fB differed between 1) normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) and remyelinated WM lesions (rWMLs) (mean: fB 6.9 [SD 2] vs. 4.0 [1.8], P = 0.01), and 2) rWMLs and demyelinated WMLs (mean: 4.2 [2.2] vs. 2.5 [1.3], P = 0.016). No association was detected between T2B and any of the histological measures.

Conclusion

fB in MS WM is dependent on myelin content and may be a tool to monitor patients with this condition.

Keywords: quantitative magnetization transfer, postmortem MRI, multiple sclerosis, myelin, axonal loss

MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS (MS) IS CHARACTERIZED by chronic inflammation and demyelination of the central nervous system. Magnetic resonance (MR) techniques are widely used to monitor the course of patients with MS. T2-weighted and gadolinium (Gd)-enhanced T1-weighted MR images display MS white matter lesions (WMLs) with high sensitivity and are useful in diagnosis (1,2). However, these MR measures correlate only modestly with disability (3,4), in part because—apart from a relationship between inflammation and Gd enhancement (5,6)—they do not distinguish key pathological features of MS, such as demyelination, remyelination, axonal loss, and gliosis (7). Additional MR measures have been developed that are quantitative and potentially more pathologically specific. These include volumetric measurements, magnetization transfer (MT) imaging, quantitative T1- and T2-relaxation time (RT) measurements, diffusion, and MR spectroscopic (MRS) metabolite concentrations (8).

Investigation of postmortem tissue allows direct assessment of the relationship between quantitative MR (qMR) measures and their pathological substrates. So far such studies have been performed to investigate the pathological correlates of T1-hypointensity (9,10), T1-RT (11), transverse magnetization decay (also known as multiexponential T2-RT) (12), and MT ratio (MTR) (10,11,13).

The MTR reflects the exchange of magnetization between protons in (at least) two pools: those that are freely mobile (conventionally referred to as the “A pool”), and those that are associated with macromolecules, such as in myelin or axonal membranes (the “B pool”) (14,15). Recent studies have suggested MTR as a putative marker of myelin content in postmortem MS brain and, by inference, in patients with MS in vivo (11,13). However, studies using animal models of demyelination have suggested that MTR may also be influenced by 1) other tissue properties, including inflammation (16,17), concentrations, and the RTs of the different proton pools; and 2) sequence-dependent factors, such as the frequency of the saturation pulse (18-20). A more detailed description of the MT effect can be achieved by extracting fundamental indices of MT, such as the fraction of macromolecular protons (fB) (21-23). As these quantitative MT (qMT) indices are absolute measures, they may also be independent of the MR system used, making comparisons between studies involving different sites and MR systems more straightforward (14).

Promising results of in vivo studies in patients with MS (22,24-27) prompted us to assess in postmortem MS brain the association of two qMT indices, fB and T2-RT of the macromolecular proton pool (T2B), with myelin content, axonal count, and gliosis. MTR and T1-RT were acquired from the same brain specimens, thereby significantly extending a previously reported dataset (11).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients/Samples

This study was approved by the ethics committee of our institution. Postmortem brain slices of 37 patients with MS (29 women and eight men) were provided by the UK Multiple Sclerosis Tissue Bank (MSTB). The mean age of the patients was 59 years (SD: 13 years; range: 34-82 years), and the mean disease duration was 27 years (SD: 12 years; range: 6-58 years).

The course of MS (28) and the disability of the patients were assessed retrospectively from the case records collected at the MSTB. Disability was estimated using the expanded disability status score (EDSS) scale (29). The brain weight of each patient was provided by the MSTB. Coronal postmortem brain slices (thickness: 1 cm) of one cerebral hemisphere were obtained a mean of 15 hours (SD: 8 hours; range: 4.5-43 hours) after death. The mean time between death and scanning was 43 hours (SD: 22; median: 38; range: 10-107 hours). The brain slices were stored in sealed plastic bags at 2-8°C until 3 hours before scanning, when they were taken out of their cool environment and plastic bags, wrapped in cling film to minimize dehydration, and left to reach room temperature. The temperature of the samples was assessed immediately after scanning using a K-type hypodermic thermocouple temperature probe connected to an HI 93551 thermometer (Hanna Instruments Ltd., Leighton Buzzard, UK). After the temperature was measured, the specimens were immersed in 10% buffered formalin solution.

MRI

Using a GE Signa Horizon Echospeed 1.5T system (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA), the following MR sequences were acquired as a single slice (thickness: 5 mm) that was centered in the middle and parallel to the coronal surfaces of the specimen (Figs. 1 and 2):

2D spin-echo (SE) T1-weighted (repetition time [TR]: 540 msec; echo time [TE]: 18 msec) and dual SE proton density (PD)- and T2-weighted (TR: 2000 msec; TE: 30-120 msec; flip angle: 90°, matrix size: 256 × 256; field of view [FOV]: 240 × 180 mm). These scans were acquired in all 37 samples.

2D spoiled gradient-echo (SPGRE) images (TR/TE/flip angle: 1180 msec/12 msec/25°; FOV: 240 × 180 with a partial k-space coverage, reconstructed as 256 × 256 over a 24-cm FOV). As previously described (26), a Gaussian MT pulse of 14.6-msec duration was applied at 10 different combinations of MT pulse offsets and powers (Table 1). Data from these acquisitions were fitted to a model based on that of Henkelmann et al (21), with modifications by Ramani et al (23) to allow for the pulsed rather than continuous MT saturation. The model allows calculation of six parameters (RB, RM0A, gM0A, f/RA(1 - 2d f), 1/RAT2A, and T2B), which are combinations of the fundamental parameter fB (the fraction of macromolecular protons), RA and RB (the inverse of the T1-RT of the A and B pools, respectively), R (the time constant for the interaction of the two pools), T2A and T2B (their transverse RTs), M0A (the initial magnetization of the A pool), and g (the scanner gain). With a separate measurement of RA (see below), fB can be separately determined, although independent determination of the other interlinked parameters is not possible. These datasets were acquired in 20 of 37 brain slices.

2D PD- and T1-weighted GRE (TR/TE/flip angle: 1500 msec/ 11 msec/45° and 36 msec/ 11 msec/45°, respectively), from which T1-RT maps were generated (30). This sequence was applied in 36 of 37 samples.

2D dual SE images (TR/TE/flip angle: 1720 msec/80 msec/90°) obtained with and without a saturation prepulse (16 msec, 23.2 μT Hamming apodized three-lobe sinc pulse, applied 1 kHz from water resonance) from which MTR maps were generated in all 37 cases (31).

Figure 1.

Correlation of MRI and histopathology in a postmortem brain slice (A) of a subject with MS. Four exemplary regions of high signal (RHS) on T2-weighted MRI (B) are pathologically confirmed MS WM lesions (WMLs, a-h). The RHS are coregistered (circles) to the respective MTR (C), fB (D), and T1-RT (E) maps. On sections stained for LFB all WMLs appear demyelinated (a-d and h). For one chronic inactive lesion sections stained for LFB (d), CD68 (c), BIEL (e and g), and GFAP (f) are shown. The myelin content and extent of gliosis were assessed by measuring transmittance (see text) on sections stained for LFB (a, b, d, and h) and GFAP (f), respectively, at a final magnification of × 125. Axonal counts were determined on sections stained for BIEL at a final magnification of × 1250 (g).

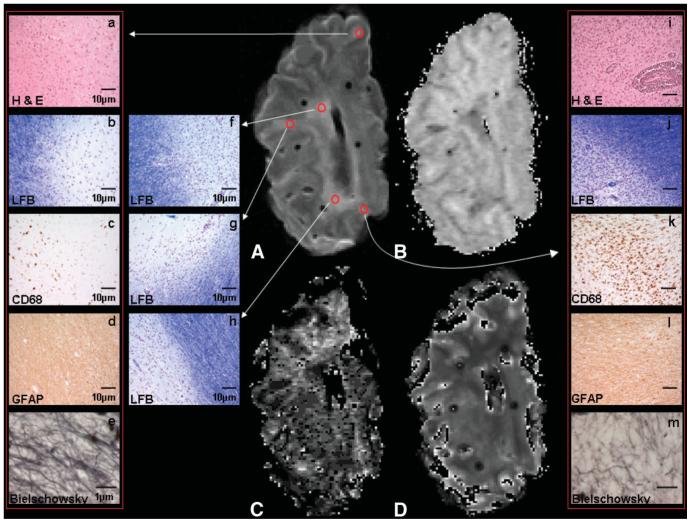

Figure 2.

Correlation of MRI (A-D) and histopathology (a-m) in postmortem MS brain. Five exemplary RHS on T2-weighted MRI (A) are pathologically confirmed MS WMLs (a-m). The respective MTR (B), fB (C), and T1-RT (D) maps are shown. For one chronic inactive (a-e) and one chronic active lesion (i-m) sections stained for H&E (a and i), LFB (b and j), CD68 (c and k), GFAP (d and l), and BIEL (e and m) are shown. Note the inflammatory infiltrate on H&E- and CD68-stained sections of the active WML (i and k) and compare with the respective sections of the chronic hypocellular WML (a and c).

Table 1.

The ten combinations of amplitude and offset frequency of the magnetization pulse used for quantitative magnetization transfer (MT) acquisition in this study

| Flip angle θSAT [°] |

Amplitude of the CWPE MT pulse ωICWPE [radians/s] | Offset frequency [Hz] |

|---|---|---|

| 212 | 185 | 1000 |

| 212 | 185 | 2500 |

| 212 | 185 | 7500 |

| 434 | 378 | 1000 |

| 434 | 378 | 3500 |

| 434 | 378 | 15000 |

| 499 | 435 | 1000 |

| 499 | 435 | 2500 |

| 499 | 435 | 5000 |

| 499 | 435 | 7500 |

CWPE = continous wave power equivalent.

The matrix size for the T1 and MTR maps was 256 × 256, and the FOV was 240 × 240 mm.

All scans and maps were displayed on a Sun workstation (Sun Microsystems, Mountain View, CA, USA) using DispImage (32). Regions of interest (ROIs) were detected, marked, and labeled on the T2-weighted scans as follows: 1) areas of hyperintense signal suspected to be MS lesions, and 2) regions of normal-appearing WM (NAWM). The ROIs were then applied to the T1-, MTR-, and qMT images, which were all inherently registered.

In 17 of 37 specimens, correspondence between ROIs detected on MRI and their pathological substrate in the specimens was performed following formalin fixation using a stereotactic procedure as previously described (33). In a further 11 of 37 specimens, this coregistration procedure was performed using the same stereotactic system during scanning under fresh conditions, i.e., before formalin fixation. In the remaining nine of 37 specimens, stereotactic coregistration was not available, and matching between lesions on MRI and in the specimen was achieved visually (11,34).

Pathological and Morphometric Procedures

In the 28 cases in which stereotactic coregistration was used, tissue blocks of approximately 2.25 cm3 in volume and centered on each lesion were dissected. The blocks were then cut in half using a 5-mm-deep iron angle, resulting in two blocks of equal thickness with the cut surface corresponding to the center of the MRI plane. In the nine cases where visual matching between MRI and the brain sample was performed, the brain slice was divided using a 5-mm-deep iron angle with the cut surface corresponding to the center of the MRI plane (34). Guided by the T2-weighted scans, several blocks containing lesions and NAWM were dissected. All dissected blocks were marked with notches at known positions, usually on the ventral and lateral cut surfaces, in order to ensure the orientation in space after further processing. The blocks were processed for embedding in paraffin. Sections were stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Luxol-Fast blue (LFB), and Bielschowsky’s silver impregnation (BIEL). Immunocytochemistry included antibodies to glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, 1/1500) and CD68 (1/100; all from Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) (Figs. 1 and 2).

MS WMLs were defined in comparison to surrounding NAWM as clearly distinct, sharply demarcated areas of 1) essentially lost staining for myelin (demyelinated plaques) or 2) uniformly thin myelin sheathing (in relationship to axon diameter), which occurs either throughout the lesion (fully remyelinated “shadow” plaque) or at the edge of an otherwise demyelinated lesion (partially remyelinated plaque) (35-37). The minimum area of remyelination required for a lesion to be considered partially remyelinated was 10% of the whole WML (11). The lesion stage was categorized as either active (inflammation throughout the lesion), chronic active (CA, hypocellular center, inflammation only at the rim of the lesion), or chronic inactive (CI, no inflammation) (Fig. 2) (38,39). Only when there was agreement between the T2-weighted MRI and histology about the presence of a WML was it included in the analysis.

In order to avoid partial-volume effects at the interface of NAWM and WMLs, NAWM ROIs on MR scans were not placed immediately adjacent to WML, whereas on histological sections the distinction between WMLs and nonlesional WM was always clear (no partial-volume effect). This allowed the assessment of WMLs and NAWM on the same slide (with the benefit of avoiding potential effects of staining batch and section thickness).

Axons were counted on BIEL-stained slides using a 21-bar (bar length: 13 μm) quadrate grid graticule (size: 160 μm2) and a final magnification of × 1250. Random points were superimposed to WML and surrounding NAWM. On each slide the total number of bars that intersected axons was counted in 12-16 areas of both the lesion and surrounding NAWM (40). The counts were then averaged for each WML and respective NAWM ROI.

Myelin content was quantified in WML and NAWM by assessing transmittance (Tr), defined as the transmitted light divided by the incident light, on LFB-stained sections using a Leica Q500MC digital image analyzer with a 256 grayscale resolution (Leica Cambridge Ltd., UK), which was mounted on a Zeiss photomicroscope 3 (Carl Zeiss, Jena, FRG). The program was set in red-green-blue (RGB) mode, the white level was kept constant at 75% of the maximum, and a final magnification of × 125 was used. Within every ROI (i.e., a lesion or an equally sized region of NAWM adjacent to a lesion) the light intensity was assessed in three to five random areas using a field size of 400 × 385 μm. The values obtained from each area were averaged and then divided by the light intensity transmitted through the object slide (away from the tissue section) to result in the Trmyelin values for WMLs and NAWM (11,41,42). A high value of Trmyelin reflects low myelin content.

Gliosis in lesions and NAWM was classified on GFAP-stained slides 1) by visual inspection as mild, moderate, or severe; and 2) quantitatively in WMLs and surrounding NAWM by light transmittance in the same manner as for myelin content and expressed as Trgliosis. A low value of Trgliosis reflects more severe gliosis than a high Trgliosis.

The thickness of LFB- and GFAP-stained sections was assessed using a stereological microscope and a final magnification of ×787.5, in order to control for possible effects of section thickness on the measurements of Tr values. On each slide, three to five measurements were performed and averaged.

Statistical Methods

When (as in this study) there are a number of tissue samples for some patients, within-patient dependency cannot be ignored, and thus tissue samples cannot be analyzed as independent observations. An analysis must recognize the data hierarchy and examine associations entirely between patients, entirely within patients, or a combination thereof that takes into account the lack of independence. In order to compare means, two methods were used. To compare means of variables in WMLs vs. NAWM, there was insufficient within-patient variability of some measures. Hence, between-patient comparisons are reported. Paired t-tests were carried out on patient means averaged over their respective tissue samples. To compare means between demyelinated and remyelinated WML, it was possible to use a combination of between- and within-subject information, and the underestimated standard error and P-values that would have resulted from a simple t-test were inflated by using linear regression with the Huber-White method (43) for inflating standard error, resulting in correctly estimated P-values. A similar approach was not possible to investigate associations between quantitative MRI and pathology indices, as here there was insufficient between-patient variability in some measures to sustain consistent use of between-patient information. Thus, within-patient associations were obtained using within-patient Pearson correlation coefficients estimated from fixed patient intercept regression (44), which ignores between-patient differences and fits an estimated average regression slope to each patient’s samples (the within-patient correlation measures the strength of the association in tissue samples belonging to the same patient, and must therefore not be interpreted as accurately representing the predictive potential between patients).

Potential confounding by slide thickness or batch was investigated by adding these terms to the regression models where appropriate (for slide batch, potential confounding is not applicable to within subject results, all of which were in the same batch). Variation within batch was assessed using a random intercept model to allow for within- and between-patient variability, with restricted maximum likelihood estimation. Where there was doubt concerning the normality of model residuals, estimates were checked against those from a nonparametric bias-corrected bootstrap with 1000 replicates (45), and validity was confirmed. Analyses were carried out using Stata 9.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

The clinical course had been secondary progressive in 22 subjects and primary progressive in four, and one each had a relapsing-remitting or progressive relapsing course. In nine subjects the clinical course could not be determined (Table 2). The estimated mean EDSS at the time of death was 8 (SD: 0.87; median: 8.5; range: 6.5-9.5). The mean brain weight was 1172 g (SD: 158 g; range: 950-1525 g).

Table 2.

Overview of patients and lesion characteristics in post mortem brain slices of 37 patients with multiple sclerosis (105 lesions).

| course | n patients | n white matter lesions |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2w | T1w [% of T2w] | demy | remy | partially remy | EA | CA | CI | ||

| RR | 1 | 3 | 2 [66.7] | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| SP | 22 | 67 | 34 [50.8] | 50 | 12 | 5 | 0 | 12 | 55 |

| PR | 1 | 1 | 1 [100] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| PP | 4 | 12 | 7 [84] | 10 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 9 |

| unclear | 9 | 22 | 19 [86.4] | 20 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 15 |

RR = relapsing-remitting MS; SP = secondary progressive MS; PR = progressive relapsing MS; PP = primary progressive MS; T2w = T2 weighted; T1w = T1 weighted; EA = early active; CA = chronic active; CI = chronic inactive; demy = demyelinated lesions; remy = remyelinated lesions.

Figures 1 and 2 provide examples of the correlation between MRI and histology, and of the image quality. The overall MR image and map quality was excellent, except for the fB maps, which had a lower signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), albeit comparable to maps acquired in vivo (26,27). Further, since the analysis performed was carried out on an ROI basis (mean size: 28 mm2), the effect of noise on the ROI mean will be reduced from the levels seen on inspection of these pixel-by-pixel maps.

Lesion Findings

Between one and seven lesions in each brain slice (mean: 3.0 lesions; SD: 1.7 lesions) could be used for the analysis. Overall, 105 MRI-visible and histologically confirmed MS WMLs were studied. Quantitative MR and pathological analyses were also performed on a single NAWM ROI in each slice. A further 63 ROIs thought to be MS lesions on T2-weighted MRI were discarded from the study due to 1) poor in-plane coregistration between MRI and the specimen (17), 2) poor identification of different tissue components on histology (10), 3) misidentification of a vascular lesion (2) or NAWM (17) as WMLs, 4) disappearance of the WML following sectioning of the tissue block (1), or 5) other technical problems (16).

Eighty-four of 105 lesions (80%) were demyelinated, 13 (12.4%) were fully remyelinated, and eight (7.6%) were partially remyelinated (Table 2). Three of 105 (2.9%) WMLs were classified as early active, 19 (18.1%) as CA, and 83 (79.1%) as CI WMLs. All (fully or partially) remyelinated WMLs were also CI WMLs. Three of 85 (3.5%) demyelinated WMLs were early active, 19 of 85 (23.4%) were CA, and 63 of 85 (74.1%) were CI WMLs.

Sixty-three of 105 lesions (60%) were hypointense, and 42 (40%) were isointense on T1-weighted MRI. Fully remyelinated shadow plaques represented four of 63 (6.4%) T1 hypointense WMLs and nine of 42 (21.4%) T1 isointense WMLs. Partially remyelinated WMLs contributed four of 63 (6.4%) T1 hypointense WMLs and four of 42 (9.5%) T1 isointense WMLs.

Fibrillary gliosis was classified in 101 of 105 lesions and observed as being nil in two of 101, mild in five of 101, moderate in 24 of 101, and severe in 74 of 101 WMLs.

Comparison of MS Lesions and NAWM (Tables 3 and 4)

Table 3.

Comparison of white matter lesions (WMLs) and normal appearing white matter (NAWM)

|

Post mortem multiple sclerosis brain (this study) |

In vivo valuesa from reference #26b |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n patients | WMLs mean (SD) | NAWM mean (SD) | difference (95% CI) | P value | WMLs mean (range) | NAWM mean (range) | |

| fB [pu] | 20 | 2.9 (1.3) | 6.7 (1.8) | -3.8 (-4.7, -3.0) | <0.0001 | 4.4 (3.0-5.8) | 8.0c |

| T2B [μs] | 20 | 11.0 (2.4) | 11.0 (1.8) | -0.1 (-1.1, 1.0) | 0.9083 | 11.6 (9.1-13.5) | 11.2c |

| MTR [pu] | 37 | 23.2 (3.5) | 33.7 (3.0) | -10.6 (-11.7, -9.4) | <0.0001 | 23.7 (20.5-25.6) | 30.9 (29.7-32.3) |

| T1-RT [ms] | 36 | 1258 (270) | 689 (144) | 569 (475, 662) | <0.0001 | 1000 (840-1210) | 710 |

| Trmyelin | 36 | 0.85 (0.11) | 0.39 (0.11) | 0.46 (0.42, 0.51) | <0.0001 | xxx | xxx |

| Axon count | 36 | 9.5 (5.7) | 18.6 (2.2) | -9.1 (-10.8, -7.5) | <0.0001 | xxx | xxx |

| Trgliosis | 34 | 0.75 (0.06) | 0.78 (0.05) | -0.03 (-0.05, -0.02) | 0.0003 | xxx | xxx |

fB = fraction of macromolecular protons; pu = percent units; T2B = T2 relaxation time of the macromolecular proton pool; MTR = magnetisation transfer ratio; T1-RT = T1 relaxation time; Trmyelin = transmittance of slides stained for Luxol fast blue; Trgliosis = transmittance of slides immuno-stained for glial fibrillary acidic protein; xxx = not applicable.

All values obtained in patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Except for MTR values in WMLs, which were obtained from reference #46 as they have not been analysed in reference #26.

No range given in reference #26.

Table 4.

Comparison of remyelinated white matter lesions (rWMLs) and normal appearing white matter (NAWM).

| n patients | rWMLs mean (SD) | NAWM mean (SD) | difference (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fB [pu] | 8 | 4.0 (1.8) | 6.9 (2.0) | -2.9 (-4.8, -0.9) | 0.0102 |

| T2B [μs] | 8 | 9.6 (1.1) | 10.9 (1.3) | -1.3 (-2.4, -0.2) | 0.0259 |

| MTR [pu] | 12 | 26.4 (3.4) | 33.7 (3.0) | -7.4 (-9.9, -4.8) | 0.0001 |

| T1-RT [ms] | 11 | 1132 (410) | 720 (156) | 411 (180, 642) | 0.0027 |

| Trmyelin | 12 | 0.66 (0.15) | 0.38 (0.11) | 0.29 (0.22, 0.36) | <0.0001 |

| Axonal count | 11 | 13.5 (5.2) | 19.2 (2.0) | -5.7 (-8.7, -2.8) | 0.0014 |

| Trgliosis | 11 | 0.74 (0.05) | 0.78 (0.03) | -0.04 (-0.07, -0.01) | 0.0163 |

fB = fraction of macromolecular protons; pu = percent units; T2B = T2 relaxation time of the macromolecular proton pool; MTR = magnetisation transfer ratio; T1-RT = T1 relaxation time; Trmyelin = transmittance of slides stained for Luxol fast blue; Trgliosis = transmittance of slides immuno-stained for glial fibrillary acidic protein.

Taking all WMLs into account fB, MTR, T1-RT, Trmyelin (inversely proportional to myelin content), axonal count, and gliosis (Trgliosis) all differed significantly between WMLs and NAWM, whereas no difference was detected for T2B. Similar results were found when the analysis was restricted to those cases in which remyelinated lesions were detected: all qMR measures (including T2B) as well as Trmyelin, axonal count and Trgliosis differed significantly between remyelinated WMLs and NAWM.

Correlation of Quantitative MR Measures and Pathology (Table 5, Fig. 3)

Table 5.

Correlations between indices assessed in post mortem brain slices of 37 patients with multiple sclerosis (20 patients/samples in which fB and T2B were investigated)

| Pearson r, p-value (n regions/n patients) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2B | fB | MTR | T1-RT | Trmyelin | Axonal count | |

| fB | -0.16, 0.214 (80/20) | |||||

| MTR | 0.06, 0.621 (80/20) | 0.82, <0.001 (80/20) | ||||

| T1-RT | -0.09, 0.481 (80/20) | -0.81, <0.001 (80/20) | -0.75, <0.001 (137/36) | |||

| Trmyelin | -0.01, 0.945 (78/20) | -0.80, <0.001 (78/20) | -0.84, <0.001 (132/36) | 0.69, <0.001 (129/35) | ||

| Axonal count | 0.05, 0.688 (77/20) | 0.72, <0.001 (77/20) | 0.68, <0.001 (129/36) | -0.57, <0.001 (126/35) | -0.79, <0.001 (194/36) | |

| Trgliosis | 0.12, 0.363 (76/19) | 0.41, 0.001 (76/19) | 0.29, 0.005 (126/34) | -0.32, 0.002 (123/33) | -0.31, <0.001 (192/34) | 0.32, <0.001 (190/34) |

fB = fraction of macromolecular protons; T2B = T2 of macromolecular protein pool; MTR = magnetisation transfer ratio; Trmyelin = transmittance of slides stained for Luxol fast blue; Trgliosis = transmittance of slides immuno-stained for glial fibrillary acidic protein.

Figure 3.

Scatterplots of myelin content (Trmyelin) on slides stained for LFB vs. (a) the fraction of macromolecular protons (fB), and (b) axonal count in postmortem brains of 20 and 37 patients with MS, respectively (r-values are within-patient correlation coefficients). A high value of Trmyelin reflects low myelin content.

Trmyelin correlated strongly with fB (r = -0.80, P < 0.001) and MTR (r = -0.84, P < 0.001), as did axonal count with fB (r = 0.72, P < 0.001). T1-RT correlated more moderately with myelin content, as did MTR with axonal count. A somewhat weaker association was detected between T1-RT and axonal count, and a still weaker correlation emerged between the severity of gliosis and fB,T1-RT, and MTR. No association was detected between T2B and any of the histological indices.

Correlation Between Neuropathological Features (Table 5, Fig. 3)

Trmyelin was strongly associated with axonal count (r= -0.79, P < 0.001). Both Trmyelin and axonal count were rather more weakly associated with Trgliosis. More severe gliosis correlated with lower myelin content and smaller axonal count.

Regression Analysis of Confounding Correlations

Predicting Myelin Content

The univariate correlation between Trmyelin and 1) fB (-0.80, P < 0.001) and 2) T1-RT (0.69, P < 0.001) was reduced to partial correlation -0.37, P = 0.004, and -0.06, P = 0.658, respectively, after adjusting for MTR. The univariate correlation between Trmyelin and MTR (-0.84, P < 0.001) was reduced to partial correlation -0.48, P < 0.001, after adjustment for fB. These results suggest that, statistically, Trmyelin is independently associated with both fB and MTR, but not with T1-RT.

Predicting Axonal Count

The univariate correlation between the axonal count and fB (0.72, P < 0.001), MTR (0.68, P = 0.001), and T1-RT (-0.57; P < 0.001) is reduced to partial correlation (0.21, P = 0.119; 0.18, P = 0.085; and -0.12, P = 0.242, respectively), after adjusting for Trmyelin. These results suggest that the association between the axonal count and fB, MTR, and T1-RT is not independent of the correlation between axonal count and Trmyelin.

Predicting Gliosis

The severity of gliosis was weakly associated with fB, MTR, and T1-RT individually (Table 5). However, regression models could not estimate the association between any qMR index and gliosis with sufficient precision to assess whether or not the associations are independent.

Comparison of Demyelinated and Remyelinated Lesions (Table 6)

Table 6.

Comparison of demyelinated and remyelinated multiple sclerosis lesions in post mortem brain specimens of seven patients with both lesion types

| mean (SD) [n lesions] |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| demyelinated max lesion n = 19 | remyelinated max lesion n = 11 | mean difference (95% CI) | p value | |

| fB [pu] | 2.4 (1.3) [16] | 4.2 (2.2) [9] | -1.8 (-3.1, -0.5) | 0.016 |

| T2B [μs] | 11.2 (3.3) [16] | 9.9 (2.6) [9] | 1.3 (-1.7, 4.2) | 0.310 |

| MTR [pu] | 21.8 (4.8) [19] | 27.4 (4.5) [10] | -5.6 (-7.5, -3.7) | <0.001 |

| T1-RT [ms] | 1348 (384) [19] | 1087 (532) [10] | 261 (19, 503) | 0.039 |

| Trmyelin | 0.91 (0.05) [19] | 0.64 (0.13) [11] | 0.27 (0.10, 0.44) | 0.008 |

| Axonal count | 6.3 (4.9) [17] | 12.9 (4.9) [10] | -6.56 (-11.17, -1.95) | 0.013 |

| Trgliosis | 0.74 (0.05) [17] | 0.74 (0.05) [10] | -0.004 (-0.06, 0.05) | 0.847 |

T1-RT = T1 relaxation time; MTR = magnetisation transfer ratio; fB = fraction of macromolecular protons; T2B = T2 relaxation time of the macromolecular proton pool; Trmyelin = transmittance of slides stained for Luxol fast blue; Trgliosis = transmittance of slides immuno-stained for glial fibrillary acidic protein; pu = percent units.

Demyelinated WMLs (which by definition are low in myelin content, and hence have a significantly higher Trmyelin than remyelinated WMLs) were lower in fB, MTR, and axonal count, and had a higher T1-RT. No difference was detected between the two lesion types for Trgliosis and T2B.

Comparison of CA and CI Lesions (Table 7)

Table 7.

Comparison of chronic active and inactive white matter lesions (WMLs) in five patients with both lesion types

| mean (SD) [n lesions] |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic active max lesion n = 11 | Chronic inactive max lesion n = 18 | mean difference (95% CI) | p value | |

| fB [pu] | 2.1 (1.4) [10] | 2.2 (1.6) [14] | -0.1 (-0.9, 0.8) | 0.847 |

| T2B [μs] | 11.3 (5.3) [10] | 11.1 (3.5) [14] | 0.2 (-1.7, 2.1) | 0.772 |

| MTR [pu] | 19.7 (4.0) [10] | 20.4 (6.3) [16] | -0.7 (-7.2, 5.9) | 0.793 |

| T1-RT [ms] | 1434 (418) [10] | 1532 (426) [16] | -98 (-475, 278) | 0.509 |

| Trmyelin | 0.87 (0.09) [10] | 0.84 (0.16) [18] | 0.03 (-0.05, 0.12) | 0.325 |

| Axonal count | 10.9 (6.8) [10] | 11.8 (5.6) [17] | -0.9 (-4.7, 2.9) | 0.542 |

| Trgliosis | 0.75 (0.03) [10] | 0.73 (0.05) [18] | 0.02 (-0.01, 0.05) | 0.127 |

T1-RT = T1 relaxation time; MTR = magnetisation transfer ratio; fB = fraction of macromolecular protons; T2B = T2 relaxation time of the macromolecular proton pool; Trmyelin = transmittance of slides stained for Luxol fast blue; Trgliosis = transmittance of slides immuno-stained for glial fibrillary acidic protein; pu = percent units.

No difference was detected for CA compared to CI lesions for any of the investigated indices. The number of early active lesions (N = 3) was considered too small to be included in this subanalysis.

None of the described relationships was substantially affected by estimated EDSS, age, disease duration, time between death and MRI, or time between death and tissue retrieval.

Slide Thickness and Batch

The mean section thickness was 8.4 μm (SD: 2.7 μm), and 4.9 μm (SD: 1.2 μm) for LFB- and GFAP-stained samples, respectively. Staining of the samples for LFB and GFAP was performed in 13 and 11 batches, respectively. Trmyelin in lesions did not vary with batch (P = 0.239), but significant batch variation was seen for Trmyelin in NAWM (P < 0.001), and borderline significance variation for Trgliosis in lesions (P = 0.064) and NAWM (P = 0.053). However, none of the observed pathology-MR correlations were affected by including section thickness and batch in the regression analysis (correlation coefficients were altered by no more than ±0.01, ±0.05, and significant P-values by no more than ±0.001, ±0.002 when adjusting for batch and thickness, respectively).

In order to test whether the 20 cases in which qMT indices were acquired differed from the entire caseload of 37 cases in terms of MTR, T1-RT, Trmyelin, axon counts, Trgliosis, and their associations, the 20 “qMT cases” were reanalyzed separately. Comparing the results of this analysis with the results described above (and in Tables 3-7) revealed a less than 10% difference in correlation coefficients, and no material difference in P-values.

DISCUSSION

This study provides robust information on the histological substrates of two novel qMT indices—fB and T2B—in postmortem MS brain. Our major findings are as follows:

fB is a predictor of myelin content in postmortem MS WM.

A significant difference of fB was seen between the following: 1) all WMLs and NAWM, 2) rWMLs and demyelinated WMLs, and 3) rWMLs and NAWM. Collectively these findings provide strong evidence that fB may be a useful tool to monitor the evolution of both demyelination and remyelination in MS WM.

Although fB was an apparent predictor of the number of axons, this correlation was largely explained by the association between 1) fB and myelin content, and 2) myelin content and axonal count.

T2B did not appear to be a useful marker in postmortem MS brain.

The MR values obtained in unfixed postmortem MS brain were similar to those reported in vivo using the same sequences (Table 3). fB was mildly reduced postmortem whereas T2B, MTR in WMLs, and T1 in NAWM were virtually identical to in vivo values. MTR in NAWM, and T1 in WMLs were slightly higher when acquired postmortem (26,46). Taken together, these data suggest that postmortem changes per se in our study had little effect on the acquired MR indices. Hence, it seems justified to infer likely in vivo changes from our data.

The novel MT index fB correlated strongly with myelin content (Table 5). According to the two-pool model of MT, fB is thought to reflect an absolute measure of the amount of macromolecular protons (i.e., the semisolid pool of protons) (14,22). The current study suggests that in WM, fB primarily reflects a proton pool (or pools) associated with myelin (26,27,47). Whereas fB was a primary predictor of myelin, this was not the case for T1-RT: multivariate regression revealed that the moderate correlation between T1-RT and myelin content was largely explained by the association of T1-RT with fB.

MTR also correlated strongly with Trmyelin. Based on a large caseload, this result confirms previous studies suggesting MTR to be a robust predictor of myelin content (10,11,13). However, although in the current study fB and MTR appeared to be similarly predictive of myelin, it should be kept in mind that they do not necessarily reflect identical molecular structures. In a simplistic model, MTR can be described as MTR = fB*T1-RT*k (where k is a constant). Hence, unlike fB, which is thought to reflect protons in the macromolecular pool only, MTR depends on both the macromolecular and the free-proton pool, with the latter also providing the physical basis of the measured T1-RT. Our study suggests that fB may indeed be a more specific marker of myelin content than MTR. Whereas fB in WMLs dropped to a mean of 43% of its value in NAWM, MTR in WMLs decreased only to 68.8%, a more significant drop being offset by the parallel increase in WMLs of T1-RT (Table 3). However, the larger variability of fB (compared to MTR) indicates that further work is needed to optimize the qMT sequence for improved accuracy of fB to assess myelin content (48).

None of the investigated MR indices was primarily associated with axonal count. This is consistent with recent studies of postmortem MS tissue suggesting the association between axonal count and MTR (and T1-RT) to be secondary to the correlation of these MR indices with myelin content, at least in chronic MS (11,13,49). In chronic postmortem MS tissue the amount and mobility of protons associated with axons appear to be less significant for the magnitude of the observed MT effect than variations in the presence and integrity of the myelin sheath (47).

Earlier studies using postmortem MS tissue suggested a strong correlation between axonal density and MTR, whereas the association between MTR and myelin appeared to be less pronounced (9,10). The difference between these studies and the current one may be explained by the following features of the present study: 1) acquisition of parametric data on myelin content and axonal count, 2) application of multivariate analysis to statistically determine the main factors of pathological change, and 3) improved accuracy of coregistration between ROIs on MRI and in tissue by using a stereotactic system in most cases.

Myelin content and axonal count were strongly associated in our study, underlining the close link between these two aspects of MS pathology, at least in the advanced stage of the disease, as has been described by many others (35,50). Thus, it is relevant to include measures of both myelin and axonal content as covariates when exploring the potential of MR measures as a marker of one or the other of these pathological processes. On average, about 50% of the axons in WMLs were lost compared to NAWM (Table 3), underlining the likely importance of axonal damage for the cumulative deficit in MS (51).

The analysis of cases with both CA and CI WMLs revealed no difference for any quantitative index (MRI or histology) between these two lesion types (Table 7). This finding suggests that in MS, inflammation may interfere to a lesser degree in the association between other pathological features, such as myelin content, and measures of MT than in animal models of inflammatory demyelination, where the intensity of inflammation is likely to be much higher than in CA MS lesions (52). As we were able to include only 18 WMLs of five cases in this analysis, further work is needed to define the effect of inflammation in postmortem MS tissue on MT indices.

We found little evidence for a potential role of T2B as a marker of a specific histological feature of MS. The significant difference of T2B between rWMLs and NAWM (P = 0.0259; Table 4) is based on the small subgroup of rWMLs, and this result is not corroborated by other analyses, including 1) a lack of difference of T2B between rWMLs and demyelinated WMLs (Table 6), and 2) a lack of correlation between T2B and Trmyelin (or any other histological index; Table 5). Hence, in line with a recent in vivo study using the same MT sequence, there is little evidence that T2B is a promising noninvasive tool to monitor MS pathology (27).

None of the MR indices investigated in this study turned out to be a meaningful predictor of gliosis (Table 5). Further work is needed to define noninvasive markers of this important feature of MS pathology.

For some indices in this study there were relatively few subjects (compared to the number of tissue samples from these subjects), and as a result there was little power for these measures to detect between-subject associations. We therefore chose to focus on the within-subject analysis to enable a consistent approach over all of the relevant correlations. While within-subject associations can illuminate pathological processes, they do not necessarily describe accurately the potential of the indices studied for predicting between-subject differences. In order to assess the latter, samples collected from a substantially larger pool of subjects would be required.

In this study we focused on probing MS WM only. It is sometimes difficult to unequivocally distinguish on MRI between gray matter (GM) and WM in postmortem tissue, particularly when the distinction between cortex and WM is concerned. This may, at least in part, be due to volume averaging (12). Recently, it was shown that including an inversion-recovery experiment in the MR protocol can help to achieve better contrast between GM and WM in postmortem brain (53). Preliminary experiments in our laboratory support these findings (data not shown). We were careful, however, in the current study to place ROIs well inside the WM to avoid contamination with GM. Higher in-plane resolution, thinner MR slice thickness, and better SNR through the application of high-field (3T and above) MR systems may improve 1) overall image quality, 2) identification of MS lesions, and 3) correspondence between changes detected on MRI and histopathology (12,54).

In conclusion, fB is a novel index to noninvasively assess myelin content in postmortem MS brain and, by inference, in vivo. Hence, fB has potential as a tool for monitoring the natural course of MS and treatments that aim to promote remyelination in patients with this condition. For application in natural-history studies and treatment trials, MTR may currently be superior to fB. Whereas technical standards have been defined for the use of MTR in trials involving patients with MS (55,56), only a few centers have so far implemented acquisition protocols and processing algorithms to assess fB. Nevertheless, with higher field strengths (57) and further sequence optimization to improve the SNR and accuracy of measurement, the potentially higher specificity of fB for macromolecular proton spins may allow it to be incorporated as a measure of myelin in multicenter trials of patients with MS.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the MSTB for providing the tissue samples for this study; Ros Gordon, Christopher Benton, and David G. MacManus for expert radiographic assistance; Gerard R. Davies, Michael J. Groves, and Tamas Revesz for helpful discussions; and Stephen Dawodu, Derek Marsdon, Steve Duerr, and Waqar Rashid for technical support. K.S. is a Wellcome Intermediate Clinical Fellow (grant 075941). D.J.T. and G.J.B. were funded by the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Contract grant sponsor: Wellcome Trust; Contract grant number: 075941; Contract grant sponsor: Sir Jules Thorn Charitable Trust; Contract grant number: 03SC/08A; Contract grant sponsor: Multiple Sclerosis Society of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

REFERENCES

- 1.McDonald WI, Compston A, Edan G, et al. Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines from the International Panel on the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:121–127. doi: 10.1002/ana.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald Criteria.”. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:840–846. doi: 10.1002/ana.20703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappos L, Moeri D, Radue EW, et al. Gadolinium MRI Meta-Analysis Group Predictive value of gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for relapse rate and changes in disability or impairment in multiple sclerosis: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 1999;353:964–969. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brex PA, Ciccarelli O, O’Riordan JI, Sailer M, Thompson AJ, Miller DH. A longitudinal study of abnormalities on MRI and disability from multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:158–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkins CP, Munro PM, Mackenzie F, et al. Duration and selectivity of blood-brain barrier breakdown in chronic relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis studied by gadolinium-DTPA and protein markers. Brain. 1990;113:365–378. doi: 10.1093/brain/113.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz D, Taubenberger JK, Cannella B, McFarlin DE, Raine CS, McFarland HF. Correlation between magnetic resonance imaging findings and lesion development in chronic, active multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:661–669. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore GRW. MRI-clinical correlations: more than inflammation alone—what can MRI contribute to improve the understanding of pathological processes in MS? J Neurol Sci. 2003;206:175–179. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00347-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tofts PS, editor. Quantitative MRI of the brain: Measuring changes caused by disease. 1st ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Walderveen MAA, Kamphorst W, Scheltens P, et al. Histopathologic correlate of hypointense lesions on T1-weighted spin-echo MRI in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1998;50:1282–1288. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.5.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Waesberghe JH, Kamphorst W, de Groot CJ, et al. Axonal loss in multiple sclerosis lesions: magnetic resonance imaging insights into substrates of disability. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:747–754. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199911)46:5<747::aid-ana10>3.3.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmierer K, Scaravilli F, Altmann DR, Barker GJ, Miller DH. Magnetization transfer ratio and myelin in postmortem multiple sclerosis brain. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:407–415. doi: 10.1002/ana.20202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore GRW, Leung E, MacKay AL, et al. A pathology-MRI study of the short-T2 component in formalin-fixed multiple sclerosis brain. Neurology. 2000;55:1506–1510. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.10.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barkhof F, Brück W, de Groot CJ, et al. Remyelinated lesions in multiple sclerosis: magnetic resonance image appearance. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1073–1081. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tofts PS, Steens SCA, van Buchem MA. MT: magnetization transfer. In: Tofts PS, editor. Quantitative MRI of the brain. Measuring changes caused by disease. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2003. pp. 257–298. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horsfield MA. Magnetization transfer imaging in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging. 2005;15(4 Suppl):S58–S67. doi: 10.1177/1051228405282242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gareau PJ, Rutt BK, Karlik SJ, Mitchell JR. Magnetization transfer and multicomponent T2 relaxation measurements with histopathologic correlation in an experimental model of MS. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;11:586–595. doi: 10.1002/1522-2586(200006)11:6<586::aid-jmri3>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanisz GJ, Webb S, Munro CA, Pun T, Midha R. MR properties of excised neural tissue following experimentally induced inflammation. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51:473–479. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanisz GJ, Kecojevic A, Bronskill MJ, Henkelman RM. Characterizing white matter with magnetization transfer and T(2) Magn Reson Med. 1999;42:1128–1136. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199912)42:6<1128::aid-mrm18>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henkelman RM, Stanisz GJ, Graham SJ. Magnetization transfer in MRI: a review. NMR Biomed. 2001;14:57–64. doi: 10.1002/nbm.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odrobina EE, Lam TY, Pun T, Midha R, Stanisz GJ. MR properties of excised neural tissue following experimentally induced demyelination. NMR Biomed. 2005;18:277–284. doi: 10.1002/nbm.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henkelman RM, Huang X, Xiang QS, Stanisz GJ, Swanson SD, Bronskill MJ. Quantitative interpretation of magnetization transfer. Magn Reson Med. 1993;29:759–766. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910290607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sled JG, Pike GB. Quantitative imaging of magnetization transfer exchange and relaxation properties in vivo using MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2001;46:923–931. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramani A, Dalton C, Miller DH, Tofts PS, Barker GJ. Precise estimate of fundamental in-vivo MT parameters in human brain in clinically feasible times. Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;20:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(02)00598-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tozer D, Ramani A, Barker GJ, Davies GR, Miller DH, Tofts PS. Quantitative magnetization transfer mapping of bound protons in multiple sclerosis. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:83–91. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davies GR, Ramani A, Dalton CM, et al. Preliminary magnetic resonance study of the macromolecular proton fraction in white matter: a potential marker of myelin? Mult Scler. 2003;9:246–249. doi: 10.1191/1352458503ms911oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies GR, Tozer DJ, Cercignani M, et al. Estimation of the macromolecular proton fraction and bound pool T2 in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004;10:607–613. doi: 10.1191/1352458504ms1105oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tozer DJ, Davies GR, Altmann DR, Miller DH, Tofts PS. Correlation of apparent myelin measures obtained in multiple sclerosis patients and controls from magnetization transfer and multicompartmental T2 analysis. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53:1415–1422. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lublin FD, Reingold SC. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology. 1996;46:907–911. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.4.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS) Neurology. 1983;33:1444–1452. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.11.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker GJ, Barker GJ, Tofts PS. Accurate multislice gradient echo T(1) measurement in the presence of non-ideal RF pulse shape and RF field nonuniformity. Magn Reson Med. 2001;45:838–845. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barker GJ, Tofts PS, Gass A. An interleaved sequence for accurate and reproducible clinical measurement of magnetization transfer ratio. Magn Reson Imaging. 1996;14:403–411. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(96)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plummer DL. Dispimage: a display and analysis tool for medical images. Riv Neuroradiol. 1992;5:489–495. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmierer K, Scaravilli F, Barker GJ, MacManus DG, Miller DH. Stereotactic coregistration of magnetic resonance imaging and histopathology in post-mortem multiple sclerosis brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2003;29:596–601. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2003.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Groot CJ, Bergers E, Kamphorst W, et al. Post-mortem MRI-guided sampling of multiple sclerosis brain lesions: increased yield of active demyelinating and (p)reactive lesions. Brain. 2001;124:1635–1645. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.8.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prineas JW, McDonald WI, Franklin RJM. Demyelinating diseases. In: Graham DI, Lantos PC, editors. Greenfield’s neuropathology. London: Arnold; 2002. pp. 471–550. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brück W, Kuhlmann T, Stadelmann C. Remyelination in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2003;206:181–185. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barkhof F, Brück W, de Groot CJ, et al. Remyelinated lesions in multiple sclerosis: magnetic resonance image appearance. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1073–1081. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trapp BD, Peterson J, Ransohoff RM, Rudick R, Mörk S, Bö L. Axonal transection in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:278–285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801293380502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Valk P, de Groot CJ. Staging of multiple sclerosis (MS) lesions: pathology of the time frame of MS. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2000;26:2–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2000.00217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brück W, Bitsch A, Kolenda H, Brück Y, Stiefel M, Lassmann H. Inflammatory central nervous system demyelination: correlation of magnetic resonance imaging findings with lesion pathology. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:783–793. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mize RR, Holdefer RN, Nabors LB. Quantitative immunocytochemistry using an image analyzer. I. Hardware evaluation, image processing, and data analysis. J Neurosci Methods. 1988;26:1–23. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(88)90125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gentleman SM, McKenzie JE, Royston MC, McIntosh TK, Graham DI. A comparison of manual and semi-automated methods in the assessment of axonal injury. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1999;25:41–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.1999.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huber PJ. The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under non-standard conditionse; Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability; Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1967. pp. 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baltagi H. Econometric analysis of panel data. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carpenter JR, Bithall JF. Bootstrap confidence intervals: when, which, what? A practical guide for medical statisticians. Stat Med. 2000;19:1141–1164. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000515)19:9<1141::aid-sim479>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gass A, Barker GJ, Kidd D, et al. Correlation of magnetization transfer ratio with clinical disability in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:62–67. doi: 10.1002/ana.410360113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Narayanan S, Francis SJ, Sled JG, et al. Axonal injury in the cerebral normal-appearing white matter of patients with multiple sclerosis is related to concurrent demyelination in lesions but not to concurrent demyelination in normal-appearing white matter. Neuroimage. 2006;29:637–642. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samson RS, Symms M, Tofts PS. Optimisation of quantitative MT (qMT) sequence acquisition parameters [Abstract] MAGMA. 2005;18(suppl 7):S243. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bot JC, Blezer EL, Kamphorst W, et al. The spinal cord in multiple sclerosis: relationship of high-spatial-resolution quantitative MR imaging findings to histopathologic results. Radiology. 2004;233:531–540. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2332031572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lassmann H, Wekerle H. The pathology of multiple sclerosis. In: Compston A, Confavreux C, Lassmann H, et al., editors. McAlpine’s multiple sclerosis. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006. pp. 557–600. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith K, McDonald WI, Miller DH, Lassmann H. The pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis. In: Compston A, Confavreux C, Lassmann H, et al., editors. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006. pp. 601–660. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stanisz GJ, Odrobina EE, Pun J, et al. T1, T2 relaxation and magnetization transfer in tissue at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54:507–512. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Geurts JJ, Pouwels PJ, Uitdehaag BM, Polman CH, Barkhof F, Castelijns JA. Intracortical lesions in multiple sclerosis: improved detection with 3D double inversion-recovery MR imaging. Radiology. 2005;236:254–260. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2361040450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mottershead J, Schmierer K, Clemence M, et al. High field MRI correlates of myelin content and axonal density in multiple sclerosis—a post-mortem study of the spinal cord. J Neurol. 2003;250:1293–1301. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-0192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berry I, Barker GJ, Barkhof F, et al. A multicenter measurement of magnetization transfer ratio in normal white matter. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999;9:441–446. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199903)9:3<441::aid-jmri12>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barker GJ, Schreiber WG, Gass A, et al. A standardised method for measuring magnetization transfer ratio on MR imagers from different manufacturers—the EuroMT sequence. MAGMA. 2005;18:76–80. doi: 10.1007/s10334-004-0095-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cercignani M, Symms MR, Ron M, Barker GJ. 3D MTR measurement: from 1.5 T to 3.0 T. Neuroimage. 2006;31:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]