Abstract

In response to agonist stimulation, the αIIbβ3 integrin on platelets is converted to an active conformation that binds fibrinogen and mediates platelet aggregation. This process contributes to both normal hemostasis and thrombosis. Activation of αIIbβ3 is believed to occur in part via engagement of the β3 cytoplasmic tail with talin; however, the role of the αIIb tail and its potential binding partners in regulating αIIbβ3 activation is less clear. We report that calcium and integrin binding protein 1 (CIB1), which interacts directly with the αIIb tail, is an endogenous inhibitor of αIIbβ3 activation; overexpression of CIB1 in megakaryocytes blocks agonist-induced αIIbβ3 activation, whereas reduction of endogenous CIB1 via RNA interference enhances activation. CIB1 appears to inhibit integrin activation by competing with talin for binding to αIIbβ3, thus providing a model for tightly controlled regulation of αIIbβ3 activation.

Introduction

The αIIbβ3 integrin is expressed on platelets and platelet precursors, megakaryocytes. Integrin αIIbβ3, when in a resting state, does not bind plasma fibrinogen. However, upon platelet stimulation by agonists such as thrombin, intracellular signals are generated that change the conformation of αIIbβ3 to an active state via “inside-out” signaling (for review see Parise et al., 2001). Activated αIIbβ3 is competent to bind soluble ligands, such as fibrinogen or von Willebrand factor, which link platelets together in aggregates. Although it is known that activation of αIIbβ3 requires the integrin cytoplasmic tails (O'Toole et al., 1994; Hughes et al., 1996; Vinogradova et al., 2004), the role of the αIIb tail in this process is not well understood.

Previously, we identified calcium and integrin binding protein 1 (CIB1; also known as CIB [Naik et al., 1997] and calmyrin [Stabler et al., 1999]), which binds to the integrin αIIb cytoplasmic tail. CIB1 is an EF-hand–containing, calcium binding protein that interacts with hydrophobic residues within the membrane-proximal region of the αIIb cytoplasmic tail (Naik et al., 1997; Shock et al., 1999; Barry et al., 2002; Gentry et al., 2005). Although CIB1 is expressed in a variety of tissues including platelets, its potential interaction with other integrin α or β subunits to date has not been reported (Naik et al., 1997; Shock et al., 1999; Barry et al., 2002). However, CIB1 also interacts with several protein kinases, such as p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1; Leisner et al., 2005) and FAK (Naik and Naik, 2003a).

Because CIB1 is one of a few proteins known to bind directly to the αIIb cytoplasmic tail, we hypothesized that CIB1 may modulate platelet αIIbβ3 activation. To determine whether CIB1 affects αIIbβ3 activation, we used differentiated megakaryocytes from murine bone marrow because megakaryocytes, unlike platelets, are amenable to direct genetic manipulation. However, like platelets but unlike many cell lines, mature megakaryocytes express αIIbβ3 and activate this integrin in response to agonists (Shiraga et al., 1999; Shattil and Leavitt, 2001; Bertoni et al., 2002), making them a suitable model system for studying platelet integrin regulation. We provide evidence that CIB1 is an inhibitor of agonist-induced αIIbβ3 activation, most likely via competition with talin binding to αIIbβ3.

Results and discussion

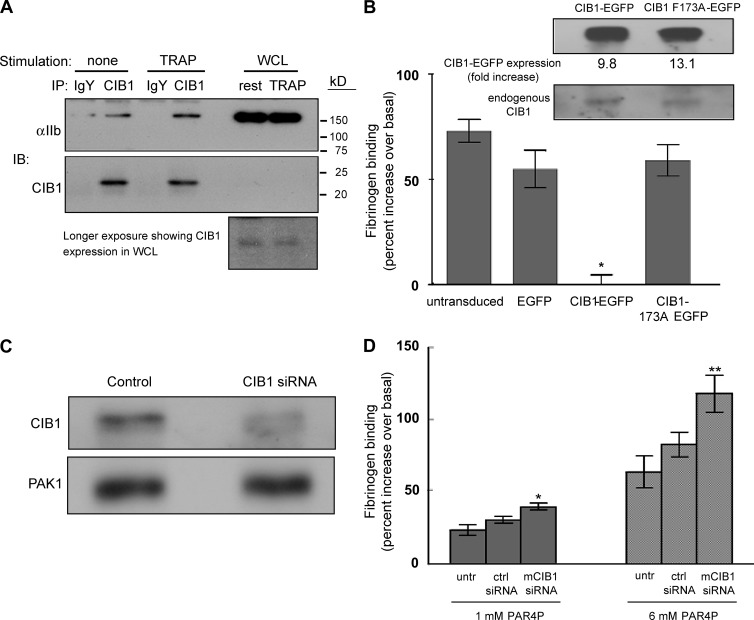

CIB1 has been shown to interact with the αIIb cytoplasmic tail by multiple approaches (Naik et al., 1997; Shock et al., 1999; Barry et al., 2002; Tsuboi, 2002) with an affinity of ∼0.3 μM (Barry et al., 2002). We find that endogenous CIB1 coimmunoprecipitates with αIIbβ3 from both resting and agonist-activated platelets, with an increased apparent association in activated platelets (Fig. 1 A ), in agreement with the purified protein studies of Vallar et al. (1999). However, the role of CIB1 in regulating αIIbβ3 function has been unclear. To address the role of CIB1 in αIIbβ3 activation, a well-characterized megakaryocyte model system (Shiraga et al., 1999; Shattil and Leavitt, 2001; Bertoni et al., 2002) was used. Stimulation of mature murine megakaryocytes with protease-activated receptor 4 activating peptide (PAR4P) significantly increased fibrinogen binding over basal levels to unstimulated megakaryocytes (agonist-induced binding is shown as percent over basal binding, which was subtracted from total binding). The PAR4P-induced fibrinogen binding was completely blocked by an anti-αIIbβ3 function-blocking mAb, 1B5 (Fig. S1 A, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200505131/DC1), in agreement with Shiraga et al. (1999), further confirming the use of fibrinogen binding as a specific marker of αIIbβ3 activation in megakaryocytes. Fibrinogen binding to unstimulated megakaryocytes was not affected by either the 1B5 mAb or by divalent cation chelation with EDTA (Fig. S1 A), indicating no basal αIIbβ3 activation.

Figure 1.

CIB1 coimmunoprecipitation and inhibition of agonist-induced fibrinogen binding to megakaryocytes. (A) αIIbβ3 coimmunoprecipitates with CIB1 in washed human platelets. CIB1 was immunoprecipitated from lysates of resting or thrombin receptor activating peptide (TRAP)–stimulated human platelets using either a control IgY or anti-CIB1 chicken IgY antibody. The membrane was probed with an anti-αIIb antibody and an anti-CIB1 chicken antibody. Whole cell lysates (WCL) indicate the position of αIIb. Blot represents three separate experiments. (B) Untransduced, EGFP-, CIB1-EGFP–, or CIB1 F173A-EGFP–expressing megakaryocytes were tested for agonist-induced increases in fibrinogen binding upon stimulation with 3 mM PAR4P. Data are percent increases in mean fluorescence over basal binding (i.e., total minus basal binding). *, P < 0.001, as compared with all other groups. The inset shows expression of CIB1-EGFP and CIB1 F173A-EGFP fusion proteins and endogenous CIB1 in transduced megakaryocytes, quantified by densitometry. Data are presented as fold increase over endogenous CIB1 expression. (C) Expression of endogenous CIB1 in control and CIB1 siRNA–transfected megakaryocytes. The membrane was also probed for PAK1 as a loading and siRNA-specificity control. (D) Percent increase in fibrinogen binding to siRNA-treated megakaryocytes stimulated with 1 and 6 mM PAR4P. The P value of murine (m) CIB1 siRNA–treated megakaryocytes was compared with untransfected (untr) or human CIB1 siRNA control cells (ctrl siRNA) at 1 and 6 mM PAR4P. All data represent means ± SEM (≥3). *, P < 0.02; **, P < 0.04.

We then asked whether CIB1 affects agonist-induced αIIbβ3 activation. Megakaryocytes overexpressing either EGFP or CIB1-EGFP were stimulated with a PAR4P, followed by three-color flow cytometric analysis to gate on large, live cells expressing GFP fluorescence (see Materials and methods). Protein overexpression was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 1 B, inset) and by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. S1 E). We found that CIB1-EGFP completely inhibited agonist-induced fibrinogen binding compared with either EGFP alone or untransduced megakaryocytes (Fig. 1 B) but did not inhibit fibrinogen binding to megakaryocytes exposed to 1 mM MnCl2 (Fig. S1 C), which directly activates αIIbβ3 independent of agonist-induced, inside-out signaling. These data suggest that CIB1 negatively regulates agonist-induced αIIbβ3 activation.

In addition to binding the αIIb tail, CIB1 also interacts with the serine/threonine kinase PAK1 (Leisner, et al., 2005; Fig. S2 A, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200505131/DC1). Because platelets (Leisner et al., 2005) and megakaryocytes (Fig. 1 C) express PAK1, we asked whether CIB1 inhibits αIIbβ3 activation via a direct interaction with αIIb or indirectly via PAK1. We therefore overexpressed a CIB1 mutant (CIB1 F173A-EGFP) that does not bind αIIb (Barry et al., 2002) but retains binding activity to PAK1 (Fig. S2 A). Previous analysis of this mutant by circular dichroism indicated minimal change of CIB1 structure (Barry et al., 2002), and yeast two-hybrid analysis confirmed that the mutant does not bind mouse αIIb (Fig. S2 B). Although the level of CIB1 F173A overexpression relative to endogenous CIB1 and percent of cells transduced was comparable to that of wild-type CIB1 (Fig. 1 B [inset] and Fig. S1 E), the CIB1 F173A mutant was unable to suppress PAR4P-induced αIIbβ3 activation (Fig. 1 B). In addition, expression levels of αIIbβ3 and basal fibrinogen binding to unstimulated megakaryocytes were comparable in megakaryocytes expressing CIB1 F173A-EGFP versus CIB1-EGFP (Fig. S1, B and D). These data suggest that a direct interaction between CIB1 and the αIIb tail is critical for suppression of αIIbβ3 activation.

To further determine whether CIB1 suppresses integrin activation by a direct or indirect mechanism, we tested its ability to suppress activation of αV integrins because we previously determined that CIB1 does not interact with the αV cytoplasmic tail (Naik et al., 1997; Barry et al., 2002) and because megakaryocytes express the αV integrin subunit (Fig. S3 A, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200505131/DC1). We found that neither CIB1-EGFP nor CIB1 F173A-EGFP had an effect on αV integrin activation as detected with WOW-1, a mAb that selectively recognizes activated αVβ3 and to a lesser extent, activated αVβ5 (Pampori et al., 1999), compared with untransduced megakaryocytes or megakaryocytes expressing EGFP alone (Fig. S3 B). These results suggest that CIB1 selectively inhibits the activation of αIIbβ3, most likely via a direct interaction with the integrin.

To determine the role of endogenous CIB1 in agonist-induced αIIbβ3 activation, we reduced CIB1 levels by RNA interference. Introduction of murine CIB1–specific small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) into megakaryocytes resulted in a consistent knockdown of endogenous CIB1 protein levels by 40–60% (Fig. 1 C). We observed a statistically significant increase in fibrinogen binding to megakaryocytes with reduced CIB1 expression, relative to cells transfected with a human CIB1 siRNA control or untransfected cells, at two different concentrations of PAR4P (Fig. 1 D). This increased fibrinogen binding was not attributable to changes in αIIb expression because flow cytometric data indicated comparable expression levels of αIIbβ3 integrin in all transfected groups (Fig. S3 C). Moreover, no enhancement of basal fibrinogen binding in the absence of agonist was observed in CIB1-depleted cells (Fig. S3 D). Thus, a consistent correlation was observed between reduced CIB1 expression and increased fibrinogen binding to agonist-stimulated megakaryocytes. These data therefore complement the CIB1 overexpression studies and indicate a negative regulatory role for CIB1 in αIIbβ3 activation.

Our data showing that CIB1 is an endogenous inhibitor of αIIbβ3 activation are in apparent contradiction to a study showing that CIB1 activates αIIbβ3 (Tsuboi, 2002). In this study, a CIB1 peptide introduced into platelets blocked agonist-induced αIIbβ3 activation. It was proposed that this blockage occurred because the peptide displaced endogenous CIB1 from αIIb, implying that CIB1 activates αIIbβ3. However, this study did not show a direct interaction between the CIB1 peptide and αIIb. Moreover, these results may be interpreted as an ability of this peptide to bind αIIb and mimic the inhibitory function of intact CIB1.

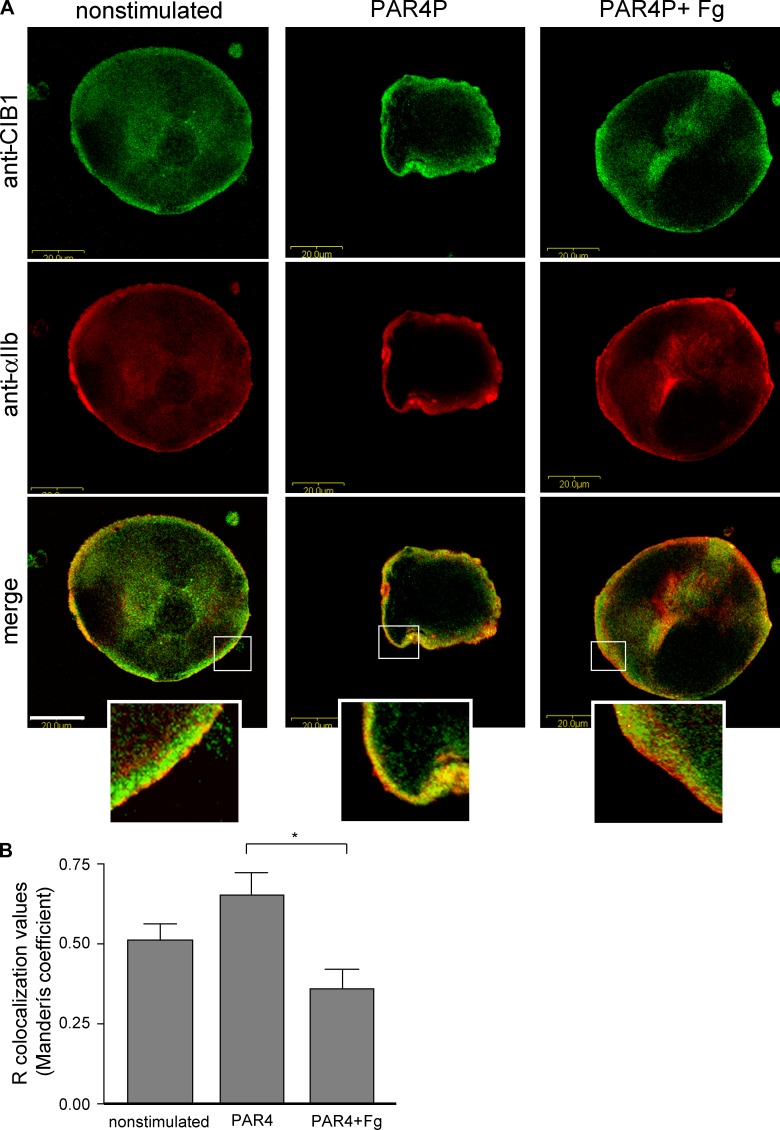

We next examined the localization of CIB1 and αIIbβ3 in resting and activated megakaryocytes by immunofluorescence. Confocal images of nonstimulated megakaryocytes showed CIB1 colocalizing with αIIb at the cell periphery (Fig. 2 A , left and inset). Upon agonist stimulation (PAR4P) in the absence of added fibrinogen, we observed a potential increase in membrane colocalization of CIB1 with αIIb (Fig. 2 A, middle and inset) that did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2 B). However, this trend is in agreement with our coimmunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 1 A) and Vallar et al. (1999). In contrast, upon agonist stimulation in the presence of soluble fibrinogen, CIB1 colocalization with αIIb decreased considerably (Fig. 2 B), as shown by distinct areas of nonoverlapping staining of CIB1 and αIIb (Fig. 2 A, right and inset), suggesting a loss of the CIB1–αIIb interaction upon ligand occupancy of αIIbβ3. These results suggest that the CIB1–αIIb interaction is dynamically and spatially regulated by agonist stimulation and ligand occupancy. In addition to the effects of CIB1 on inside-out signaling, the significant redistribution of CIB1 upon fibrinogen binding to activated αIIbβ3 suggests that CIB1 may also become available to mediate outside-in signaling events. In this regard, it has been reported that CIB1 contributes to outside-in signaling via αIIbβ3 (Naik and Naik, 2003b).

Figure 2.

Colocalization of endogenous CIB1 and αIIbβ3 in nonstimulated and agonist-stimulated megakaryocytes. (A) Nonstimulated, PAR4P, or PAR4P + fibrinogen (Fg)–treated megakaryocytes were adhered to poly-l-lysine, fixed, and stained with antibodies against CIB1 and αIIb. CIB1 is shown in green, αIIb in red, and colocalization in yellow. Boxed areas are enlarged to show membrane distribution of CIB1 and αIIb. Bars, 20 μm. (B) Histogram depicts relative colocalization R values calculated as described in Materials and methods. *, P < 0.01, as compared with agonist-stimulated conditions. Data represent means ± SEM (n = 4) for each condition.

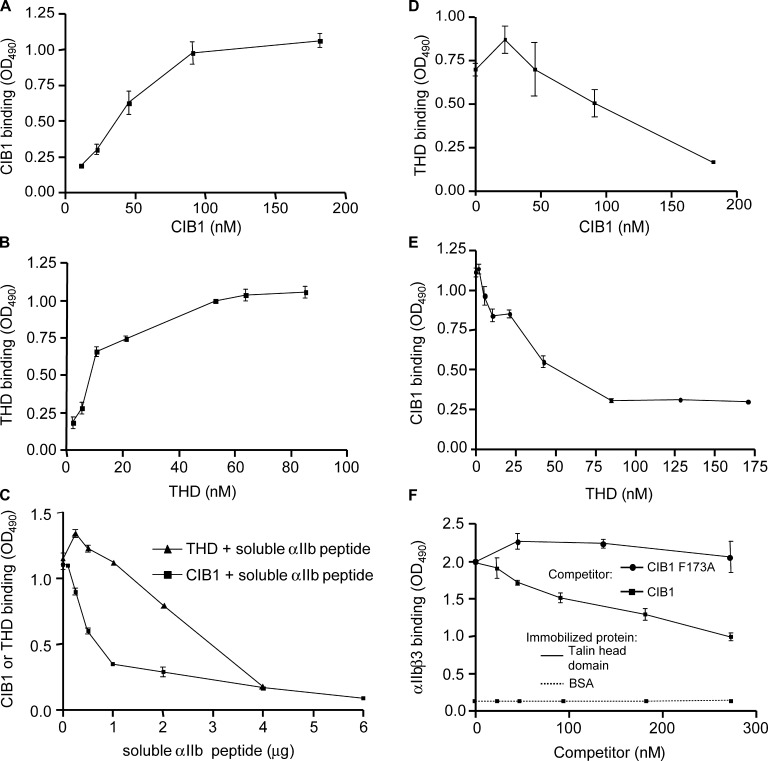

To determine a molecular mechanism by which CIB1 inhibits αIIbβ3 activation, we asked whether CIB1 affects binding of the integrin-activating protein talin with both the αIIb cytoplasmic tail and the intact integrin heterodimer. Talin is a cytoskeletal protein recently shown to play a critical role in activating several integrins via interaction of the talin head domain (THD) with β cytoplasmic tails, including β3 (Calderwood et al., 1999; Tadokoro et al., 2003); in addition, talin also binds to the αIIb cytoplasmic tail (Knezevic et al., 1996). Using recombinant CIB1 and THD in solid-phase binding assays, we found that both CIB1 and THD bound to immobilized αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide in a direct, saturable manner (Fig. 3, A and B ), with THD binding to immobilized αIIb peptide at a slightly higher apparent affinity. To determine relative affinities of CIB1 and THD for soluble versus immobilized αIIb tail, equimolar concentrations of soluble CIB1 and THD were incubated with increasing concentrations of soluble αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide before addition to immobilized αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide (Fig. 3 C). Although CIB1 binding was significantly inhibited at concentrations of <1 μg of soluble peptide per well, no inhibition of THD binding to immobilized αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide was observed at these concentrations, suggesting that CIB1 has a higher relative affinity than THD for soluble αIIb. These results also suggest that THD has a higher relative affinity than CIB1 for the immobilized αIIb tail peptide. Furthermore, competitive binding assays showed that increasing concentrations of soluble CIB1 almost completely inhibited THD binding to immobilized αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide (Fig. 3 D). Similarly, soluble THD inhibited CIB1 binding to immobilized αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide (Fig. 3 E). Consistent with THD having a higher affinity for immobilized αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide, ∼25 nM THD inhibited 50% of CIB1 binding to αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide, whereas this concentration of CIB1 had little effect on THD binding to αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide.

Figure 3.

CIB1 inhibits talin binding to the αIIb cytoplasmic tail and αIIbβ3. (A and B) Solid-phase binding studies using recombinant CIB1 and THD. Increasing concentrations of CIB1 (A) or THD (B) were added to wells coated with αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide. CIB1 or THD binding was detected using an anti-CIB1 or anti-talin antibody, respectively. (C) Increasing concentrations of αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide were incubated with a constant concentration of 10 nM CIB1 or THD before addition to αIIb peptide-coated wells. Binding of CIB1 or THD was detected as in A and B, respectively. (D) Competitive inhibition of THD binding to immobilized αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide by CIB1. 10 nM of soluble THD was added to wells in the presence of increasing concentrations of soluble CIB1. THD binding was detected using an anti-THD rabbit pAb. (E) Competitive inhibition of 10 nM CIB1 binding to immobilized αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide by increasing concentrations of THD. CIB1 binding was detected using a chicken anti-CIB1 antibody. (F) CIB1 partially inhibits αIIbβ3 binding to immobilized THD. Soluble, activated RGD affinity–purified αIIbβ3 (Frelinger et al., 1990) was incubated with increasing concentrations of CIB1 or CIB1 F173A before addition to immobilized THD. Integrin αIIbβ3 binding was detected using an anti-αIIb mAb. Data represent means ± SEM (≥3).

We then asked whether CIB1 interferes with THD binding to purified, activated αIIbβ3 heterodimer; CIB1 maximally inhibited ∼50% of the binding of solution phase αIIbβ3 to immobilized THD (Fig. 3 F) because higher concentrations of CIB1 had no further inhibitory effect (unpublished data). These data are consistent with a study showing that an anti–αIIb tail antibody also maximally inhibits ∼50% of αIIbβ3 binding to immobilized talin, with the remaining binding attributed to the β3 tail (Knezevic et al., 1996). Moreover, the mutant protein CIB1 F173A, which does not bind the αIIb tail, did not inhibit αIIbβ3 binding to immobilized THD (Fig. 3 F). These results suggest that CIB1 inhibits αIIbβ3 activation at least in part by competing with talin for direct binding to the αIIb cytoplasmic tail in platelets and megakaryocytes. These data may also indicate that CIB1 prevents a functional engagement of talin with αIIbβ3 via a CIB1-associated conformational change in αIIb that directly affects β3 so that bound talin cannot activate αIIbβ3. The finding that CIB1 overexpression completely inhibits αIIbβ3 activation but only partially inhibits talin interaction with αIIbβ3 also raises the possibility that talin binding to β3 alone is insufficient to activate αIIbβ3.

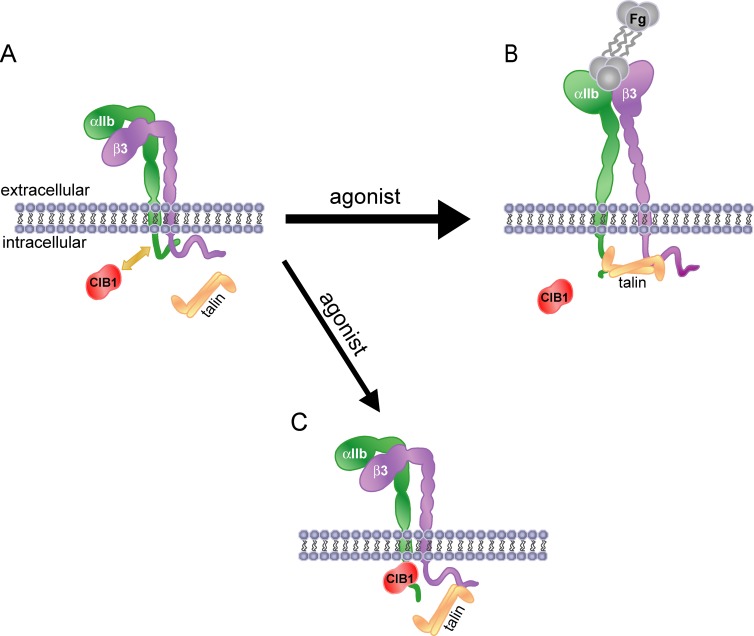

Our data demonstrate that CIB1 is an endogenous inhibitor of agonist-induced αIIbβ3 activation. We propose that in the resting state, CIB1 is associated with a portion of αIIbβ3 molecules (Fig. 4 A ). Agonist stimulation promotes talin association with the majority of integrin cytoplasmic tails (Tadokoro et al., 2003; Calderwood, 2004; Qin et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2004), resulting in αIIbβ3 activation and fibrinogen binding (Fig. 4 B). However, we also predict that during agonist-induced activation, talin cannot bind to αIIb and/or properly engage β3 within the CIB1-associated αIIbβ3 molecules (Fig. 4 C). The numbers of CIB1-associated complexes may increase during agonist-induced activation based on our coimmunoprecipitation data (Fig. 1 A) and the observed trend toward increased colocalization (Fig. 2), thus implicating a role for CIB1 during inside-out signaling events that regulate integrin αIIbβ3 activation. Consequently, this portion of CIB1-occupied αIIbβ3 would be unable to undergo agonist-induced activation and fibrinogen binding (Fig. 4 C). Furthermore, the redistribution upon soluble fibrinogen binding (Fig. 2) and decreased relative colocalization of CIB1 with αIIbβ3 suggests that CIB1 may also be regulated by and participate in outside-in signaling via αIIbβ3. Because a decrease in endogenous CIB1 levels does not induce spontaneous integrin activation (Fig. S3 D), our model further predicts that CIB1 exerts its effect on αIIbβ3 during agonist stimulation to limit the extent of activation, as opposed to maintaining αIIbβ3 in a resting state in unstimulated cells, which may instead be regulated by properties intrinsic to the integrin (O'Toole et al., 1990).

Figure 4.

Model of CIB1 regulation of αIIbβ3 activation. (A) In the resting state, a limited amount of CIB1 may be associated with a portion of resting αIIbβ3. (B) Upon agonist stimulation, most αIIbβ3 molecules are predicted to become associated with talin, which converts αIIbβ3 to an activated state such that the integrin can bind fibrinogen (Fg). (C) Agonist stimulation may induce a redistribution of additional CIB1 to the plasma membrane to facilitate further association of CIB1 with a portion of αIIbβ3 molecules via binding to the αIIb tail. CIB1-associated αIIbβ3 is unable to bind talin in a fully functional manner and therefore remains in a resting or intermediate state unable to bind fibrinogen.

In conclusion, our results indicate that CIB1 is a negative regulator of agonist-induced αIIbβ3 activation, thus providing a mechanism for the precise control of αIIbβ3 activation in megakaryocytes. Although megakaryocytes are not platelets, they are platelet precursors and share many similarities, suggesting that the function of CIB1 extends to platelets. It will be of interest in future studies to determine whether endogenous CIB1 levels in platelets correlate inversely with platelet reactivity, a known risk factor for coronary artery disease (Frenkel and Mammen, 2003).

Materials and methods

Megakaryocyte transfection and flow cytometry

The Sindbis expression system was obtained from Invitrogen. The human CIB1 gene or a mutant human CIB1 gene (F173A; Barry et al., 2002) was fused to the EGFP gene at the COOH terminus of CIB1 and cloned into the pSinRep5 vector. The virus was produced in BHK cells for megakaryocyte transduction. Megakaryocytes were derived from bone marrow cultures of C57BL/6J mice, and flow cytometry was performed as described previously (Shiraga et al., 1999). Differentiated megakaryocytes were transduced with various viral constructs for 20 h and collected in modified Tyrode's buffer with 1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 (Shiraga et al., 1999) at 106 cells/ml. Overexpression level of CIB1-EGFP and CIB1 F173A-EGFP were quantified via densitometry using the software Quantity One (Fluor-S Multimager; Bio-Rad Laboratories) and adjusted as fold over endogenous CIB1 expression. 50 μl of the megakaryocyte suspension was mixed with agonist PAR4P (GYPGKF) and soluble Alexa Fluor 546–conjugated fibrinogen (15 μg/ml final concentration; Invitrogen) at RT for 30 min and diluted with chilled Tyrode's buffer containing propidium iodide at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. Cells were immediately analyzed on a flow cytometer (FACStar Plus; Becton Dickinson). Live, EGFP-positive megakaryocytes were measured for Alexa Fluor 546 fibrinogen binding in the FL2 channel. Data were collected as mean fluorescence intensities using Summit software (DakoCytomation). Basal fibrinogen binding is defined as the mean fluorescence intensity of megakaryocytes with Alexa Fluor 546 fibrinogen but without agonist stimulation. The t test was used in statistical analyses in all experiments.

siRNA construction and transfection

Murine CIB1–specific siRNAs were generated with the Silencer siRNA construction kit (Ambion; Elbashir et al., 2002). Two 21-base sequences were developed that target sites (208) 5′-AAGGAGCGAAUCUGCAUGGUC-3′ and (448) 5′-AAGCAGCUGAUUGACAAUAUC-3′ of the mRNA transcript as well as a control human CIB1–specific siRNA (5′- AAGUG- CCCUUCGAGCAGAUUC-3′), which has no homology to murine CIB1 or to any sequence in the mouse genome. Megakaryocytes were transduced with siRNAs at 200 nM (according to the manufacturer's protocol; Mirus), incubated at 37°C for 48 h, and subjected to flow cytometry and Western blotting.

Solid-phase binding assays

Microtiter wells (Immulon 2 HB; Dynex Technologies) were coated with and without 5 μg/well of full-length human αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide (LVLAMWKVGFFKRNRPPLEEDDEEGQ) or 2.5 μg/well of purified THD and blocked with 3% BSA. CIB1 or THD (50 μl) were incubated for 1 h, and binding was detected with a chicken anti-CIB1 polyclonal antibody (pAb) or mouse anti-talin (clone 8d4; Sigma-Aldrich). For competition binding assays, 10 nM of soluble CIB1 or THD was incubated with increasing concentrations of soluble αIIb cytoplasmic tail peptide, THD, or CIB1 before addition to wells containing immobilized αIIb peptide. Binding of CIB1 or THD was detected using an anti-CIB1 or -talin antibody, respectively. Binding of RGD-purified αIIbβ3 (Frelinger et al., 1990) to immobilized THD ± CIB1 or CIB1 F173A proceeded for 2–3 h. Integrin αIIbβ3 binding was detected with a mAb, 11G1, which recognizes the intracellular portion of αIIb and does not overlap with the CIB1 binding site.

Immunofluorescence

Cultured murine megakaryocytes on poly-l-lysine were stained with antibodies against CIB1 and αIIb. CIB1 localization was detected with a chick pAb, and αIIb was recognized by rabbit anti-αIIb pAb. Confocal images were captured by Fluoview software (Olympus) with a Fluoview 300 laser scanning confocal imaging system configured with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus; IX70) fitted with a Plan Apo 60× oil objective. The images were assembled (Fig. 2) in Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe). To quantify the relative colocalization of multiple images (n = 4), we calculated the RColoc value (Pearson's correlation coefficients, per image set, for pixels above the calculated thresholds for the images). Pearson coefficient is a statistical appraisal of how well a linear equation describes the relationship between two variables for a measured function and is commonly used in image colocalization analysis.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 characterizes the overexpression of wild-type CIB1 and mutant CIB1 F173A and the fibrinogen binding to megakaryocytes expressing these fusion proteins. Fig. S2 shows the binding characteristics of wild-type CIB1 and mutant CIB1 F173A to PAK1 and integrin αIIb. Fig. S3 shows integrin αV expression and activation and also shows effects of CIB1 depletion on integrin αIIbβ3 expression and basal activation. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200505131/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Sanford Shattil and the members of his laboratory for advice regarding primary murine megakaryocytes. We also thank Dr. Noah Sciaky for analysis of merged fluorescent images.

This research was funded by National Institutes of Health training grants F32 HL10381 to W. Yuan, HL41793 to S.C.-T. Lam, and 2-P01-HL45100 and 2-P01-HL06350 to L.V. Parise.

W. Yuan and T.M. Leisner contributed equally to this paper.

M.K. Larson's present address is Institute for Biomedical Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK.

Abbreviations used in this paper: CIB1, calcium and integrin binding protein 1; pAb, polyclonal antibody; PAK1, p21-activated kinase 1; PAR4P, protease-activated receptor 4 activating peptide; siRNA, small interfering RNA; THD, talin head domain.

References

- Barry, W.T., C. Boudignon-Proudhon, D.D. Shock, A. McFadden, J.M. Weiss, J. Sondek, and L.V. Parise. 2002. Molecular basis of CIB binding to the integrin alpha IIb cytoplasmic domain. J. Biol. Chem. 277:28877–28883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoni, A., S. Tadokoro, K. Eto, N. Pampori, L.V. Parise, G.C. White, and S.J. Shattil. 2002. Relationships between Rap1b, affinity modulation of integrin alpha IIbbeta 3, and the actin cytoskeleton. J. Biol. Chem. 277:25715–25721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood, D.A. 2004. Integrin activation. J. Cell Sci. 117:657–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood, D.A., R. Zent, R. Grant, D.J. Rees, R.O. Hynes, and M.H. Ginsberg. 1999. The Talin head domain binds to integrin beta subunit cytoplasmic tails and regulates integrin activation. J. Biol. Chem. 274:28071–28074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir, S.M., J. Harborth, K. Weber, and T. Tuschl. 2002. Analysis of gene function in somatic mammalian cells using small interfering RNAs. Methods. 26:199–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frelinger, A.L.I.I.I., I. Cohen, E.F. Plow, M.A. Smith, J. Roberts, S.C. Lam, and M.H. Ginsberg. 1990. Selective inhibition of integrin function by antibodies specific for ligand-occupied receptor conformers. J. Biol. Chem. 265:6346–6352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, E.P., and E.F. Mammen. 2003. Sticky platelet syndrome and thrombocythemia. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 17:63–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, H.R., A.U. Singer, L. Betts, C. Yang, J.D. Ferrara, J. Sondek, and L.V. Parise. 2005. Structural and biochemical characterization of CIB1 delineates a new family of EF-hand-containing proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 280:8407–8415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, P.E., F. Diaz-Gonzalez, L. Leong, C. Wu, J.A. McDonald, S.J. Shattil, and M.H. Ginsberg. 1996. Breaking the integrin hinge. A defined structural constraint regulates integrin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 271:6571–6574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knezevic, I., T.M. Leisner, and S.C.T. Lam. 1996. Direct binding of the platelet integrin alphaIIbbeta3 (GPIIb-IIIa) to talin. Evidence that interaction is mediated through the cytoplasmic domains of both alphaIIb and beta3. J. Biol. Chem. 271:16416–16421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leisner, T.M., M. Liu, Z.M. Jaffer, J. Chernoff, and L.V. Parise. 2005. Essential role of CIB1 in regulating PAK1 activation and cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 170:465–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik, M.U., and U.P. Naik. 2003. a. Calcium-and integrin-binding protein regulates focal adhesion kinase activity during platelet spreading on immobilized fibrinogen. Blood. 102:3629–3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik, U.P., and M.U. Naik. 2003. b. Association of CIB with GPIIb/IIIa during outside-in signaling is required for platelet spreading on fibrinogen. Blood. 102:1355–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik, U.P., P.M. Patel, and L.V. Parise. 1997. Identification of a novel calcium-binding protein that interacts with the integrin alphaIIb cytoplasmic domain. J. Biol. Chem. 272:4651–4654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole, T.E., J.C. Loftus, X.P. Du, A.A. Glass, Z.M. Ruggeri, S.J. Shattil, E.F. Plow, and M.H. Ginsberg. 1990. Affinity modulation of the alpha IIb beta 3 integrin (platelet GPIIb-IIIa) is an intrinsic property of the receptor. Cell Regul. 1:883–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole, T., Y. Katagiri, R.J. Faull, K. Peter, R. Tamura, V. Quaranta, J.C. Loftus, S.J. Shattil, and M.H. Ginsberg. 1994. Integrin cytoplasmic domains mediate inside-out signal transduction. J. Cell Biol. 124:1047–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampori, N., T. Hato, D.G. Stupack, S. Aidoudi, D.A. Cheresh, G.R. Nemerow, and S.J. Shattil. 1999. Mechanisms and consequences of affinity modulation of integrin alpha(V)beta(3) detected with a novel patch-engineered monovalent ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 274:21609–21616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parise, L., S.S. Smyth, and B.S. Coller. 2001. Platelet morphology, biochemistry, and function. In Williams Hematology. E. Beutler, M.A. Lichtman, B.S. Coller, T.J. Kipps, and U. Seligsohn, editors. McGraw-Hill, New York. 1357–1408.

- Qin, J., O. Vinogradova, and E.F. Plow. 2004. Integrin bidirectional signaling: a molecular view. PLoS Biol. 2:726–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattil, S.J., and A.D. Leavitt. 2001. All in the family: primary megakaryocytes for studies of platelet alphaIIbbeta3 signaling. Thromb. Haemost. 86:259–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraga, M., A. Ritchie, S. Aidoudi, V. Baron, D. Wilcox, G. White, B. Ybarrondo, G. Murphy, A. Leavitt, and S. Shattil. 1999. Primary megakaryocytes reveal a role for transcription factor NF-E2 in integrin αIIbβ3 signaling. J. Cell Biol. 147:1419–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shock, D.D., U.P. Naik, J.E. Brittain, S.K. Alahari, J. Sondek, and L.V. Parise. 1999. Calcium-dependent properties of CIB binding to the integrin alphaIIb cytoplasmic domain and translocation to the platelet cytoskeleton. Biochem. J. 342:729–735. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabler, S.M., L.L. Ostrowski, S.M. Janicki, and M.J. Monteiro. 1999. A myristoylated calcium-binding protein that preferentially interacts with the Alzheimer's disease presenilin 2 protein. J. Cell Biol. 145:1277–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro, S., S.J. Shattil, K. Eto, V. Tai, R.C. Liddington, J. M.de Pereda, M.H. Ginsberg, and D.A. Calderwood. 2003. Talin binding to integrin beta tails: a final common step in integrin activation. Science. 302:103–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi, S. 2002. Calcium integrin-binding protein activates platelet integrin alpha IIbbeta 3. J. Biol. Chem. 277:1919–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallar, L., C. Melchior, S. Plancon, H. Drobecq, G. Lippens, V. Regnault, and N. Kieffer. 1999. Divalent cations differentially regulate integrin alphaIIb cytoplasmic tail binding to beta3 and to calcium- and integrin-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 274:17257–17266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova, O., J. Vaynberg, X. Kong, T.A. Haas, E.F. Plow, and J. Qin. 2004. Membrane-mediated structural transitions at the cytoplasmic face during integrin activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:4094–4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, T., J. Takagi, B.S. Coller, J.H. Wang, and T.A. Springer. 2004. Structural basis for allostery in integrins and binding to fibrinogen-mimetic therapeutics. Nature. 432:59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.