Observations of Vulnerability to Neoplastic Transformation in Early S Phase

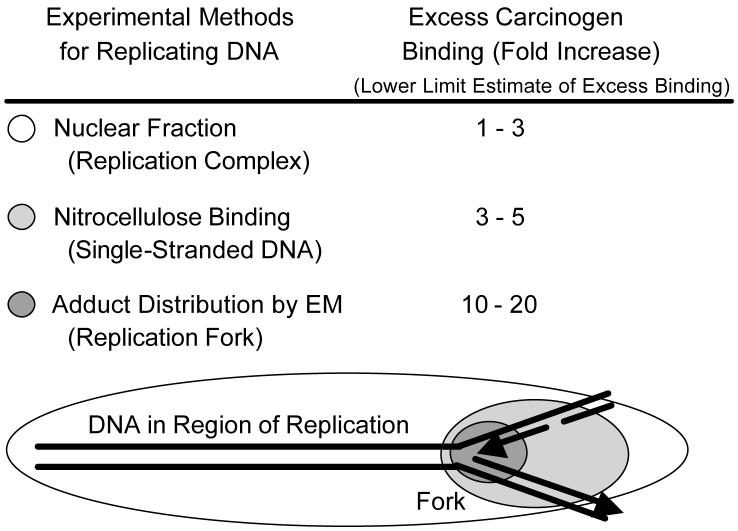

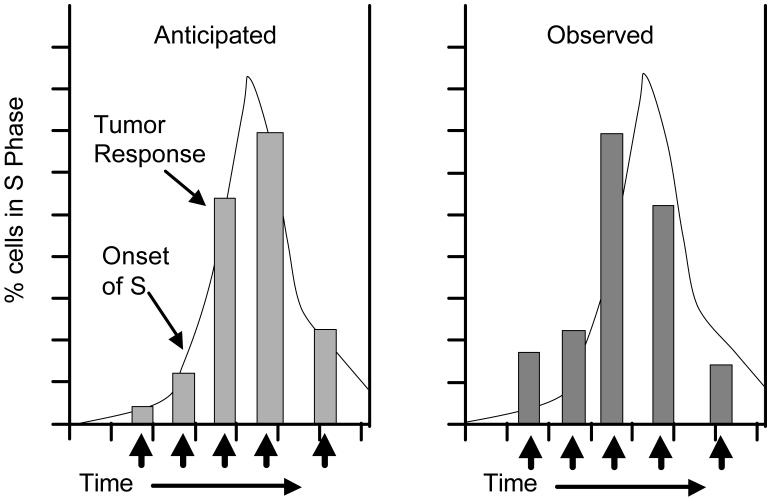

The most prevalent human neoplasms arise in tissues containing cells that normally proliferate rapidly or proliferate in response to injury. In contrast, neoplasms are rare in tissues whose cells replicate either infrequently or not at all. Several years ago we began to investigate the nature of the relationship between cell proliferation and carcinogenesis. Since we believed that the structure of DNA in the process of replication might make it more vulnerable to attack by chemical carcinogens, we initially undertook a series of studies that compared adduction of carcinogens to replicating DNA as compared to non-replicating DNA. Our initial studies compared a crude nuclear fraction enriched in replicating DNA as compared to the remainder of nuclear DNA. Subsequently we used the partially single stranded nature of replicating DNA to compare DNA with partial single strandedness to bulk of the nuclear DNA. Finally, we used antibodies to adducted DNA to visually localize sites of adduction and quantitated the levels of carcinogen adduction with respect to distance from the replication fork in electron micrographs of DNA fibers. Each of these studies revealed that chemical carcinogens bound more effectively to DNA that was replicating (Figure 1). Ultimately we demonstrated that the most extensive adduction to be at the site of replication (i.e., DNA replication forks) as compared to the rest of the nuclear DNA (Cordeiro-Stone et al., 1982; Paules et al., 1988). In view of the finding that replicating DNA was particularly prone to attack by chemical carcinogens we undertook studies to explore the question of whether the sensitivity of cells to neoplastic transformation induced by chemical carcinogens varies during the cell cycle. Since replicating DNA was more prone to carcinogen attack than DNA that was not replicating, it was our hypothesis that the vulnerability to neoplastic transformation would parallel the rate of DNA synthesis in the proliferating populations. In the studies we performed to investigate this issue, carcinogen treatments were performed at different points during synchronized cell cycles in cultured mouse cells in vitro (Grisham et al., 1980) and in regenerating rat liver in vivo (Kaufmann et al., 1987a, b). The results of these studies did not confirm our expectations that the tumor response would parallel the rate of DNA synthesis (Figure 2, left panel). Instead, these studies did not precisely parallel the rate of DNA replication but were skewed to an early time in the S phase (Figure 2, right panel). The results indicated to us that proliferating cells are most susceptible to neoplastic transformation by chemical carcinogens if they are treated in the earliest part of the S phase. When we more precisely analyzed the relationship between tumor response and the cycle distribution of cells at risk we found that there was an exquisite correlation between cells entering the S phase and the tumor response. This observation suggested that cells exposed to carcinogens when in early S phase are most likely to sustain persistent genetic damage, probably mutagenic or clastogenic damage, in DNA sequences that are replicating during this narrow window of the cell cycle. Presumably, the early replicating DNA fraction includes segments of DNA that are important genetic targets for the initiation of the process of malignant transformation. Based on these findings and the hypothesis we derived from them we began a program of studies seeking to identify areas of the genome that are replicated at the beginning of S phase. This was motivated by our reasoning that the genetic target explaining the vulnerability of cells to transformation at the start of the S phase would be found among them.

Fig. 1.

Results and schematic representation of observed findings for enhancement of carcinogen adduction of replicating DNA in three different types of experiments. The tabular data in the figure reports the fold-excess of carcinogen adduction in each of the types of replicating DNA preparations. The schematic representation at the bottom of the figure illustrates the relationship between regions of DNA evaluated in each of the experiments with color coding relating the affected regions to the tabular data.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of expected and observed findings of tumor response as function of treatment time. This cartoon illustrates how the formation of liver tumors in partially hepatectomized rats was maximal when the carcinogen was administered when most of the proliferating hepatocytes were at the beginning of the S phase. The curve profiles the percentage of cells in S phase; columns represent tumor response (both number of tumors per liver and number of animals with liver tumors); black arrows indicate the time of administration of the carcinogen (Kaufmann et al., 1987a, b).

Temporal Order of DNA Replication

Given that our goal was to identify areas of the genome that are replicated at the beginning of S phase we had to learn more about the temporal order of DNA replication. As we began these studies it was the general belief that actively expressed genes were replicated early in the S phase, early here meaning the first half of the S phase. Inactive genes and structural DNA, like centromeric DNA, were thought to replicate in the second half of the S phase. It was clear that to pursue our goal we needed to have far better resolution about the time of replication of genes and the ability to assess the stability of the temporal order of gene replication. Our ability to perform studies with the capacity to define the temporal order of DNA replication with higher resolution required the availability of a very well synchronized population of cells. We chose to use human cells because of the powerful genomic knowledge and tools that were in prospect and because of their obvious greater relevance to human cancers. The cells we used were non-immortalized, low passage human foreskin fibroblasts established in our laboratory. These studies used the DNA polymerase inhibitor aphidicolin to improve the synchronization of mammalian cells in culture (Pedrali-Noy et al., 1980; Cordeiro-Stone and Kaufman, 1985). In this protocol, cells are first arrested at confluence, and then replated at lower densities in fresh medium containing aphidicolin (2 μg/ml). When the medium containing aphidicolin is replaced with normal medium the cells rapidly regain their ability to synthesize DNA and they progress through the cell cycle with most cells poised to begin the S phase with a high degree of synchrony. This synchronization protocol enabled us to obtain information on the timing of replication of DNA sequences across the entire S phase (Doggett et al., 1988; Cordeiro-Stone et al., 1990). If the cells released from the aphidicolin block are allowed to proceed through the S phase, the DNA being synthesized in different 1-hr periods of the S phase could be labeled with BrdU and isolated in CsCl gradients. Initially, we blotted these DNA samples on nitrocellulose filters for hybridization with radioactive probes for specific genes, and were able to determine the time of replication of a number of oncogenes in rodent (Doggett et al., 1988) and human (Cordeiro-Stone et al., 1990) cells. In initial studies, we examined the replication of specific genes during the S phase and found that their replication timing was highly ordered and conserved in a given cell type (Doggett et al., 1988; Kaufman and Cordeiro-Stone, 1990; Sorscher and Cordeiro-Stone, 1991). More recently, we have prepared DNA with the same protocol and used this DNA as template in PCR amplification reactions with primers designed for specific region of the genome under analysis (Brylawski et al., 2004; Chastain et al., 2006). By comparing the quantitative PCR signal obtained using template DNA from each of the time fractions of the S phase, we have been able to estimate the time of replication of any amplifiable genomic region with considerable precision.

In our initial studies we had found that inhibition of DNA synthesis by aphidicolin under these conditions is not complete. Cells exposed to aphidicolin are able to begin S phase, but because DNA replication proceeds very slowly, at approximately 2% of the normal rate, only a small percentage of the DNA is labeled under these conditions (Tribioli et al., 1987; Brylawski et al., 2000). If one keeps the cells in aphidicolin for extended periods of time but labels the DNA synthesized, the same temporal order of replication is observed although it takes vastly longer times to replicate the DNA. We utilized this synchronization technique and the leakiness of the aphidicolin blockade to identify early replicating sites on a genomic scale. Cells cultured with aphidicolin for synchronization also were treated with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) to label the DNA synthesized as the entered the S phase. Thereafter the cells were washed to remove both the aphidicolin and BrdU and allowed to progress to mitosis. Areas of bi-allelic BrdU incorporation were identified with fluorescent antibodies and associated with specific chromosomal bands in the metaphase chromosomes. A few chromosomal band regions that consistently replicated at the onset of S phase were detected and assigned to chromosomal bands; the most notable BrdU incorporation was found in chromosomal bands 1p36.1, 8q24.1, 12q13, 15q22, 15q15, and 22q13 (Cohen et al., 1998).

Using the same protocol, we used BrdU to label the DNA replicated during the aphidicolin incubation (and thus containing the very earliest sequences synthesized in S phase) and harvested the cells before the inhibitor was removed. The DNA containing BrdU was separated and purified by density gradient centrifugation and this DNA was used to construct a cosmid library of approximately 10,000 clones (Brylawski et al., 2000). We showed first that the library was enriched in early-replicating genes, and found a correlation between the presence of both early replicating and matrix binding site sequences in library clones (Brylawski et al., 2000). By the time the genome project delivered the (almost) complete sequence of the human genome, we used sequence information about individual clones and the available genomic information to map these clones to human chromosomes. Ultimately high quality sequence data was obtained for the ends of about 8,000 of the library clones and most clones could be mapped precisely to the human genome (Genome-Wide Sequence and Functional Analysis of Early Replicating DNA in Human Fibroblasts. Cohen SM, Furey TS, Doggett NA, and Kaufman DG, submitted manuscript). This analysis showed that a large portion of the clones clustered in discrete areas of the genome. These sites included, but were not limited to, the chromosomal bands that were previously found to be prominently labeled early in S phase (Cohen et al., 1998). The clones were also shown to be enriched in elements typical of early replicating DNA. The ability to map regions of early replication in the genome advanced our quest considerably, allowing us to identify several potential targets for carcinogenic damage.

Identification of origins of DNA replication

In our quest to identify preferential targets for carcinogenic damage, we have also focused our attention on origins of DNA replication that fire early in the S phase. We reasoned that origin sequences would be vulnerable to DNA modifications during the unwinding of DNA strands necessary to allow for replicon initiation. We also reasoned that the origins of DNA replication would be the very earliest sites of replication in regions of the genome replicated early in the S phase. In these studies, we employed a modification of the nascent strand abundance assay introduced by Giacca (Giacca et al., 1994, 1997) to identify origins of DNA replication, typically within a DNA region of a few hundreds of base pairs. Our efforts focused initially on regions that were represented both in library clones and in early replicating chromosomal bands (Cohen et al., 1998; Brylawski et al., 2004). Later, these studies were extended to other early replicating origins, identified mainly because of their association to gene promoters and CpG islands, both of which are characteristically enriched in early replicating DNA (Delgado et al., 1998; Antequera and Bird, 1999). Four origins of bidirectional replication were mapped to the X chromosome: the origins associated with the HPRT (Cohen et al., 2002) and G6PD gene promoters, which replicate early (Cohen et al., 2003), and the FMR2 (Chastain et al., 2006) and FMR1 (manuscript accepted pending revisions) gene promoters, which replicate late in the S phase. These studies added several new origins to the relatively small number of recognized human origins of DNA replication. The determination of the time of replication of these specific origins was also done in the hope of finding sequence determinants that might be common to early or late activation of origins of bidirectional replication as well as sequence features that might distinguish origins of DNA replication that are activated early.

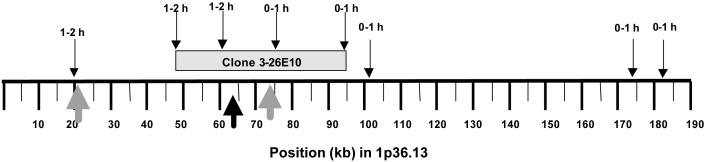

Having established the position of two early- and two late-replicating origins on the same chromosome, we are now much closer to being able to evaluate the link between carcinogen binding and DNA replication at different times in the S phase and at specific chromosomal sites, a correlation that was hypothesized on the basis of our earliest carcinogenesis studies. Our efforts toward locating origins of replication and determining replication timing have also aided us in gaining insight in the organization of replicons. Among the clones that mapped to 1p36.13, one of the chromosomal bands that was labeled early in S phase, clone 3-26E10 was found to contain a region that replicates very early during the first hour of the S phase at one end, and a region replicating in the second hour of the S phase at the other end (Figure 3). Two origins of replication were found in this genomic region, one in the clone itself and the other only about 50 kb away from the first. We determined the time of replication across the whole region and found that there was more than a one-hour difference in the time of activation of the two origins despite their close proximity. Under typical rates of fork progression during replication the second origin would have been passed by the fork activated earlier. This did not happen, however, perhaps because of an intervening boundary area at which replication is delayed. At the boundary region we found two inverted copies of a 275-bp sequence (92% homology), separated by about 1 kb (Brylawski et al., 2004), and proposed that these might function as a fork barrier or pause site, analogously to the role of transcriptional insulators. Inverted repeats (palindromes) have been reported to be obstacles to the progression of replication forks (Lebofsky and Bensimon, 2005).

Fig. 3.

Identification of a transition in replication timing found in a clone from a library of early replicating DNA sequences from normal human fibroblasts. Arrows on top of the schematic point to the time of replication in clone 3-26E10 and the illustrated contig from 1p36.13. Below, large gray arrows point to the two origins found in the contig; the black arrow indicates the region possibly responsible for slowing or stopping the replication fork emanating from the earlier of the two origins (gray arrow on the right). The distances in the contig are indicated in kb, starting from position 18,954,557 in 1p36.13.

In other studies of human origins of DNA replication, we assessed the activity of the human HPRT replicator by placing it into the homologous region in the mouse genome and demonstrated that the human sequence directed cross-species initiation of DNA synthesis (Cohen et al., 2004). We also evaluated origin usage on both the inactive and the active X chromosomes We found that the same origin of DNA replication was used on both the inactive and the active X chromosomes despite the fact that the two origins are activated at different times in the S phase and that one gene is transcribed and the other is not (Cohen et al., 2003). Our studies suggest that determinants of the location and timing of activation of origins will require understanding of chromatin structure and associated chromatin proteins as well as features of DNA sequence.

Analysis of DNA fibers using the molecular combing technique

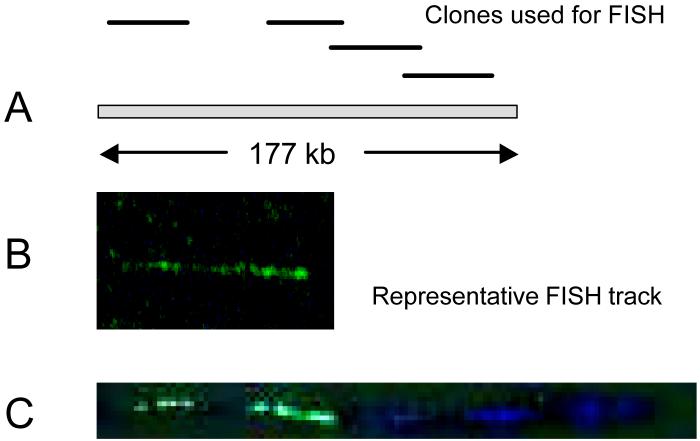

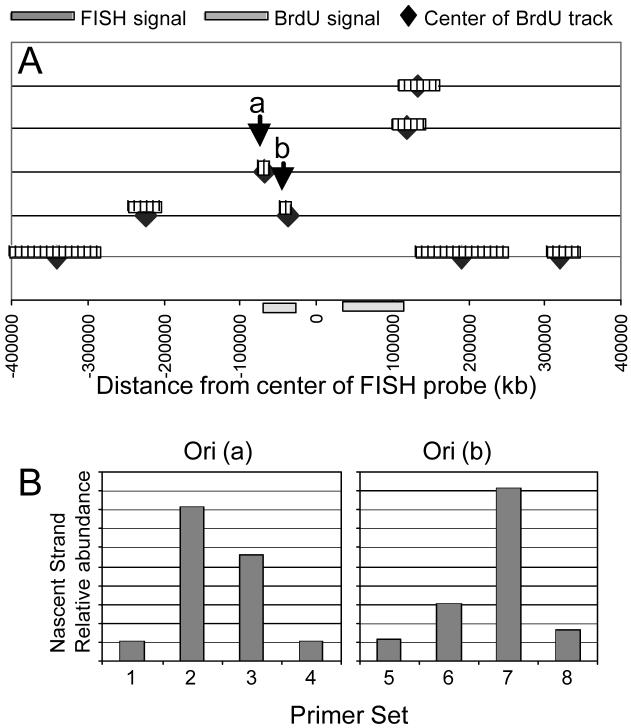

The replication origins we have been able to identify to date have all been associated with CpG islands in transcriptional promoter regions of genes. This sequence characteristic provides a useful marker that will aid in the future search of gene-associated origins and in the study of the relationship of replication and transcription. However, there are other origins of replication. There are probably many origins that are not associated with genes, particularly in large non-coding intergenic regions, such as the origin in the β-globin (Aladjem et al., 1995) and DHFR (Hamlin et al., 1992) regions. The nascent strand abundance assay that we and others have used to locate origins of replication requires the use of a high density of PCR markers (sometimes overlapping) around a prospective origin. Although very accurate, this methodology is not applicable to the screening of large expanses and is most useful for identifying origins in small regions of the genome, preferably those regions coding for a gene and with a CpG island associated with its transcriptional promoter. Therefore, an alternative method of surveying large regions for the presence of initiation of DNA replication would be useful, such as the analysis of replication tracks on DNA fibers. Sites of replication initiation and of ongoing bidirectional DNA replication have been visualized by DNA fiber autoradiography after labeling of the nascent strands with a radioactive nucleotide (Huberman and Riggs, 1966) and, more recently, with BrdU (Jackson and Pombo, 1998) and other halogenated nucleotide analogs (Takebayashi et al., 2001). Exciting results have also been observed where DNA is straightened and aligned on a microscope slide in a procedure called molecular combing and this aligned DNA from proliferating cells is used to observe DNA synthesized when pulsed with one or more DNA precursors (Bensimon et al., 1994). The incorporation of halogenated precursors is detected with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies, and the tracks can be measured and ordered according to their relative positions and sizes. It is also possible to look for DNA replication activity in specific regions of the genome by employing a FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) probe labeled by nick translation with a biotinylated DNA precursor. The probe hybridized to the DNA fiber is then detected with an anti-biotin antibody conjugated to a different fluorochrome than those used to visualize the replication tracks. We have recently applied this method to search for labeling patterns that would indicate the presence of an origin of replication in the vicinity of the DNA sequence highlighted by the FISH probe. When we applied this combined technique we were able to find the approximate location of origins of DNA replication in the 22q13 early replicating band, as illustrated in Figure 4. Using the information obtained in these combed DNA studies with a FISH probe to distinguish a region of chromosome 22, we detected labeling patterns that were suggestive of the presence of origins of DNA replication. Preliminary data using the nascent strand abundance assay, made feasible by the narrowing of the region to be tested by information from the DNA fiber immunofluorescence technique, appear to have identified the presence of origins of DNA replication at predicted sites (Figure 5).

Fig. 4.

Identification of novel origins in an early replicating region of chromosome 22. Genomic DNA from proliferating human fibroblasts labeled for 10 min with 100 μM bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) was combed onto glass slides and hybridized with FISH probes for sequences in 22q13.1. Regions of BrdU incorporation were also detected on the same slides. A: Relative position of the clones from our early library used for FISH, chosen to provide specificity and orientation. B: Representative FISH probe signal (green); C: Regions of blue fluorescence indicate where replication activity is located relative to the specific FISH probe (green).

Fig. 5.

Analysis of replication tracks in 22q13.1 leading to the mapping of replication origins. A: Five DNA fibers were aligned according to the FISH probe location. Replication tracks (blue boxes) were found in different areas of this large region. For simplicity, the FISH track (green) is shown only once, at the bottom. The center of each replication track was considered a potential replication origin. The two regions labeled (a) and (b) were further tested by using the nascent strand abundance assay. B: Preliminary results of nascent strand abundance assays of two of the possible initiation sites detected by fiber analysis.

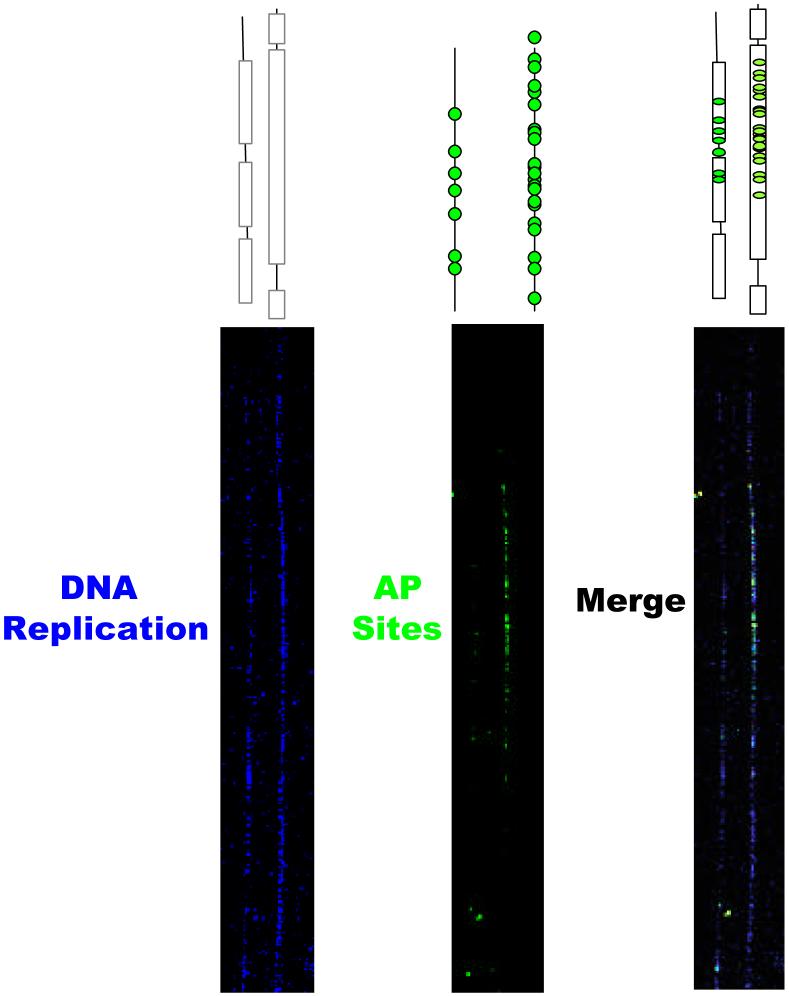

The powerful technique of fiber-FISH together with the visualization of sites of DNA replication as determined by the position of nucleotide analog tracks may also enable us to attempt to answer more thoroughly our original question: What are the specific early replicating targets of carcinogens in human cells? Towards this goal, we have used DNA combing to analyze inhibition of initiation of DNA replication in response to DNA damage (Chastain et al., 2006) and we are currently using the technology to examine the distribution of DNA damage at specific genomic sites. DNA base lesions generated by alkylation, deamination, and oxidative processes are repaired in the cell by the base excision repair (BER) pathway. This DNA repair pathway is initiated by a DNA glycosylase that excises modified bases by hydrolytic cleavage of the N-glycosylic bond between the modified base and deoxyribose, resulting in the formation of apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) sites as DNA repair intermediates. These abasic sites can be tagged with a FITC-conjugated Aldehyde Reactive Probe (F-ARP) and visualized on combed DNA strands. We have been able to visualize DNA replication and sites of damage in the form of abasic sites in the same DNA fibers (Figure 6). We found that the distribution of these sites of DNA damage was not random and that lesions found in clusters accounts for a sizable proportion of the total DNA damage. By adding al FISH signal that identifies a specific genomic region, it should be possible to precisely identify the distribution of DNA damage in selected regions of the genome.

Fig. 6.

Detection of replication and damage on combed DNA fibers. Genomic DNA from human fibroblasts was labeled with BrdU and combed onto glass slides. A: DNA replication (blue signal) detected with anti BrdU antibodies. B: Abasic sites detected with FITC-Aldehyde Reactive Probe (FARP, green signal). C: When the two images are merged, AP-site signal can be visualized within the confines of the BrdU label, indicating the presence of damage coincident with areas of DNA replication.

Summary

Our studies have revealed that replicating DNA is more vulnerable to adduction than is non-replicating DNA. Contrary to our expectations that the vulnerability to neoplastic transformation induced by carcinogens in synchronized cells would parallel the rate of DNA replication, we actually found that the vulnerability was notably increased early in the S phase and more closely paralleled the rate of entry cells into the S phase (the very beginning of S phase) rather than the overall rate of DNA synthesis. From these findings we hypothesized that there were targets for the neoplastic transformation of cells that were among the earliest replicated sequences in the genome. To test that this hypothesis was plausible we investigated the temporal order of DNA replication during the S phase and showed that the order of DNA replication was far more precisely defined than had been recognized previously. The cell synchronization techniques that made those findings possible made it feasible to demonstrate that only a relatively few sites of DNA replication are identifiable in chromosomal bands at the earliest times in the S phase. The same synchronization techniques enabled us to label DNA replicated when populations of cells were very early in S phase and to isolate and clone this DNA. The clonal elements of this library of DNA prepared in this manner have been sequenced and mapped to the human genome. Efforts are in progress to characterize the genes and sequence features associated with these regions. We have utilized methods to identify and characterize origins of DNA replication as a means of locating the earliest replicating part of these early replicating regions. We have identified several new origins of DNA replication that are activated early and late in the S phase but the features of the chromatin at the origin that determines its time of activation remain obscure. In an effort to improve our ability to identify more origins, particularly adjacent origins in genomic regions, we have combined the methods of DNA combing and FISH analysis of combed DNA to search for DNA precursor incorporation patterns characteristic of origins of DNA replication. Preliminary nascent strand abundance studies appear to have proven the existence of two origins of DNA replication predicted from the precursor incorporation studies. We have found that the combed DNA techniques can be combined with precursor incorporation studies and antibodies to sites of DNA damage to address questions of mechanisms of DNA damage and repair. For example these studies have shown recently that DNA damage is not randomly distributed in the genome and that both inhibition of replicon initiation and inhibition of strand elongation are separately distinguishable as components of the S checkpoint function.

It is our hope and expectation that these results and the opportunities that they provide for future studies will enable us to identify possible targets for malignant transformation that explain our observation that cells at the start of S phase are vulnerable to the initiation of carcinogenesis.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by NIH research grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA84493) and from the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences (ES09112).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aladjem MI, Groudine M, Brody LL, Dieken ES, Fournier RE, Wahl GM, Epner EM. Participation of the human beta-globin locus control region in initiation of DNA replication. Science. 1995;270:815–9. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antequera F, Bird A. CpG islands as genomic footprints of promoters that are associated with replication origins. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R661–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80418-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensimon A, Simon A, Chiffaudel A, Croquette V, Heslot F, Bensimon D. Alignment and sensitive detection of DNA by a moving interface. Science. 1994;265:2096–8. doi: 10.1126/science.7522347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brylawski BP, Cohen SM, Cordeiro-Stone M, Schell MJ, Kaufman DG. On the relationship of matrix association and DNA replication. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2000;10:91–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brylawski BP, Cohen SM, Horne H, Irani N, Cordeiro-Stone M, Kaufman DG. Transitions in replication timing in a 340 kb region of human chromosomal R-Band 1p36.1. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:755–69. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brylawski BP, Cohen SM, Longmire JL, Doggett NA, Cordeiro-Stone M, Kaufman DG. Construction of a cosmid library of DNA replicated early in the S phase of normal human fibroblasts. J Cell Biochem. 2000;78:509–17. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(20000901)78:3<509::aid-jcb15>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chastain PD, 2nd, Cohen SM, Brylawski BP, Cordeiro-Stone M, Kaufman DG. A late origin of DNA replication in the trinucleotide repeat region of the human FMR2 gene. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:869–72. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.8.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chastain PD, 2nd, Heffernan TP, Nevis KR, Lin L, Kaufmann WK, Kaufman DG, Cordeiro-Stone M. Checkpoint regulation of replication ynamics in UV-irradiated human cells. Cell Cycle. 2006:5. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.18.3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SM, Brylawski BP, Cordeiro-Stone M, Kaufman DG. Mapping of an origin of DNA replication near the transcriptional promoter of the human HPRT gene. J Cell Biochem. 2002;85:346–56. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SM, Brylawski BP, Cordeiro-Stone M, Kaufman DG. Same origins of DNA replication function on the active and inactive human X chromosomes. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:923–31. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SM, Cobb ER, Cordeiro-Stone M, Kaufman DG. Identification of chromosomal bands replicating early in the S phase of normal human fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 1998;245:321–9. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SM, Hatada S, Brylawski BP, Smithies O, Kaufman DG, Cordeiro-Stone M. Complementation of replication origin function in mouse embryonic stem cells by human DNA sequences. Genomics. 2004;84:475–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro-Stone M, Doggett NA, Laundon CA, Kaufman DG. Timing of proto-oncogene replication and its relationship to transformation sensitivity to chemical carcinogens. In: Paukovits WR, editor. Growth Regulation and Carcinogenesis. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1990. pp. 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro-Stone M, Kaufman DG. Kinetics of DNA replication in C3H 10T1/2 cells synchronized by aphidicolin. Biochemistry. 1985;24:4815–22. doi: 10.1021/bi00339a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro-Stone M, Topal MD, Kaufman DG. DNA in proximity to the site of replication is preferentially alkylated in S phase 10T1/2 cells treated with N-methyl-N-nitroso-urea. Carcinogenesis. 1982;3:1119–27. doi: 10.1093/carcin/3.10.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado S, Gomez M, Bird A, Antequera F. Initiation of DNA replication at CpG islands in mammalian chromosomes. Embo J. 1998;17:2426–35. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doggett NA, Cordeiro-Stone M, Chae CB, Kaufman DG. Timing of proto-oncogene replication: a possible determinant of early S phase sensitivity of C3H 10T1/2 cells to transformation by chemical carcinogens. Mol Carcinog. 1988;1:41–9. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940010110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacca M, Pelizon C, Falaschi A. Mapping replication origins by quantifying relative abundance of nascent DNA strands using competitive polymerase chain reaction. Methods. 1997;13:301–12. doi: 10.1006/meth.1997.0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacca M, Zentilin L, Norio P, Diviacco S, Dimitrova D, Contreas G, Biamonti G, Perini G, Weighardt F, Riva S, et al. Fine mapping of a replication origin of human DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:7119–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisham JW, Greenberg DS, Kaufman DG, Smith GJ. Cycle-related toxicity and transformation in 10T1/2 cells treated with N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:4813–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.8.4813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin JL, Dijkwel PA, Vaughn JP. Initiation of replication in the Chinese hamster dihydrofolate reductase domain. Chromosoma. 1992;102:S17–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02451781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberman JA, Riggs AD. Autoradiography of chromosomal DNA fibers from Chinese hamster cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1966;55:599–606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.55.3.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DA, Pombo A. Replicon clusters are stable units of chromosome structure: evidence that nuclear organization contributes to the efficient activation and propagation of S phase in human cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:1285–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman DG, Cordeiro-Stone M. Variation in susceptibility to initiation of carcinogenesis during the cell cycle. In: Milo GE, editor. Transformation of human diploid fibroblasts: Molecular and genetic mechanisms. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1990. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WK, Rahija RJ, MacKenzie SA, Kaufman DG. Cell cycle-dependent initiation of hepatocarcinogenesis in rats by (+/-)-7r,8t-dihydroxy-9t,10t-epoxy-7,8,9,10-tetrahydro-benzo(a)pyrene. Cancer Res. 1987a;47:3771–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann WK, Rice JM, Wenk ML, Devor D, Kaufman DG. Cell cycle-dependent initiation of hepatocarcinogenesis in rats by methyl(acetoxymethyl)nitrosamine. Cancer Res. 1987b;47:1263–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebofsky R, Bensimon A. DNA replication origin plasticity and perturbed fork progression in human inverted repeats. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6789–97. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6789-6797.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paules RS, Cordeiro-Stone M, Mass MJ, Poirier MC, Yuspa SH, Kaufman DG. Benzo[alpha]pyrene diol epoxide I binds to DNA at replication forks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:2176–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.7.2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrali-Noy G, Spadari S, Miller-Faures A, Miller AO, Kruppa J, Koch G. Synchronization of HeLa cell cultures by inhibition of DNA polymerase alpha with aphidicolin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:377–87. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.2.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorscher DH, Cordeiro-Stone M. Gene replication in the presence of aphidicolin. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1086–90. doi: 10.1021/bi00218a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebayashi SI, Manders EM, Kimura H, Taguchi H, Okumura K. Mapping sites where replication initiates in mammalian cells using DNA fibers. Exp Cell Res. 2001;271:263–8. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribioli C, Biamonti G, Giacca M, Colonna M, Riva S, Falaschi A. Characterization of human DNA sequences synthesized at the onset of S-phase. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:10211–32. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.24.10211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]