Abstract

Background. Hepatic injury secondary to warm ischemia and reperfusion (I/R) remains an important clinical issue following liver surgery. The aim of this prospective, randomized study was to determine whether steroid administration may reduce liver injury and improve short-term outcome. Patients and methods. Forty-three patients undergoing liver resection were randomized to a steroid group or a control group. Patients in the steroid group received 500 mg of methylprednisolone preoperatively. Serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate amminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin, anti-thrombin III (AT-III), prothrombin time (PT), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) were compared between the two groups. Length of stay and type and number of complications were recorded. Results. Postoperative serum levels of ALT, AST, total bilirubin, and inflammatory cytokines were significantly lower in the steroid group than in controls. The postoperative level of AT-III in the control group was significantly lower than in the steroid group (ANOVA p < 0.01). The incidence of postoperative complications in the control group tended to be significantly higher than that in the steroid group. Conclusion. These results suggest that steroid pretreatment represents a potentially important biologic modifier of I/R injury and may contribute to maintenance of coagulant/anticoagulant homeostasis.

Keywords: hepatic ischemia-reperfusion, surgical stress, liver surgery, corticosteroid administration

Introduction

Blood loss and transfusions during liver resection are associated with unfavorable short- and long-term outcomes 1,2,3,4. Inflow occlusion through clamping of the portal triad (Pringle maneuver) is routinely used in many centers to prevent blood loss during transection of the liver parenchyma. However, the Pringle maneuver causes ischemia and reperfusion (I/R) injury to the remaining liver, with a risk of poor postoperative outcome 2,5. Diseased liver with chronic liver disease poorly tolerates reperfusion injury and can develop liver failure even after short periods of ischemia 6.

Different strategies have been reported to confer a state of protection against hepatic I/R injury 7. In this context, pharmacologic protection, such as the administration of steroid before or during portal clamping, has been used to reduce I/R-dependent liver injury and surgical stress following hepatic resection 8,9. Although several studies in rodent models have demonstrated the biological efficacy of steroids in attenuating hepatic I/R injury 10,11,12,13,14, data about the clinical effectiveness of perioperative steroid administration in liver surgery are still limited 15,16,17. The aim of this prospective randomized study was to investigate the effects of preoperative steroid administration on hepatic ischemic injury and short-term outcome in patients undergoing hepatic resection.

Patients and methods

Patients

From April to September 2004, 43 consecutive patients undergoing elective hepatic resection in the Department of Surgery – Liver Unit at San Raffaele Scientific Institute, were enrolled into the trial. Patients were assigned randomly to a steroid group (n=21) or a control group (n=22). Patients in the steroid group received 500 mg of methylprednisolone (Pharmacia Corp., Peapack, NJ, USA) just before the surgery. Patients requiring concomitant thoracic or colorectal surgery, additional ablation therapies (radiofrequency), as well as liver resections performed under total vascular exclusion were excluded from the study. Patients undergoing a total ischemia time of <20 min were also excluded. All patients gave informed consent before enrolment in the trial. Postoperative complications were evaluated for 30 days after surgery.

Surgical procedure

Laparatomy was performed through a right subcostal incision and a midline incision. The intermittent Pringle maneuver was applied at the time of liver transection and consisted of cross-clamping of the hepatoduodenal ligament for 20 min and releasing the clamp for 10 min until the transection was completed. The procedure was repeated as necessary. Transection of the hepatic parenchyma was carried out by a combination of the clamp fracture technique, ultrasonic dissector (Soring, Quickborn, Germany), and harmonic scalpel (Ultracision, Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH, USA) along with hemostasis of the vessels by clips or ligation, and coagulation by electrocautery or argon beam. A closed suction drain was placed in the peritoneal cavity in all patients. Each patient was operated under the supervision of the same hepatobiliary surgeon (L.A.), who was unaware of the patient's group allocation. Unless clinically contraindicated, a systemic antibiotic, first-generation cephalosporin (Cefazolin, Mead Johnson, Princeton, NJ, USA) was routinely applied just before the surgery, ending on the fourth postoperative day.

Clinical variables

Postoperative markers of hepatocyte damage and recovery, including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), bilirubin, and coagulative parameters [prothrombin time (PT-INR) and antithrombin III (AT-III)] were measured on postoperative day (POD) 1, 2, and 5. Data regarding preoperative variables, duration of surgery, intraoperative blood loss and transfusion, intraoperative and postoperative complications, and hospital stay were collected prospectively. Underlying liver disorders such as steatosis, fibrosis, and other types of injury were also evaluated.

Serum levels of TNF-α and IL-6

Serum levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were measured at the induction of anesthesia, and on POD 1, 2, and 5. Serum levels were quantified by using an ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's specifications (Bouty, Milan, Italy). Data were then presented as picograms per milliliter of serum TNF-α. The detection limit of the assay was 1 pg/ml for TNF-α and 0.1 pg/ml for IL-6.

Statistical analysis

A minimal sample size of 17 patients per group was calculated to detect a 100 U/L difference in the peak ALT levels with a SD of 100 U/L with a level of statistical significance of 0.05 and a power of 0.80, using a post hoc two-sample t test. Continuous variables were expressed using the Mann–Whitney test and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Multiple comparisons were made using repeated-measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) as needed. Results are reported as mean±SD. Significance was defined as p < 0.05. All analyses were performed using the statistical package SPSS 12.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Clinical variables of patients

Twenty-nine males and 14 females were included in the study. There was no significant difference regarding the patients’ age, gender, ischemia time, or underlying liver disease between patients randomized in the steroid group versus control group (Table I). Even though ischemia time was longer in the steroid group (48±18 min) than in the control group (29±17 min), possibly because of a higher number of extended right hepatectomies in the steroid group, no significant difference was recorded. Thirteen patients were operated for liver metastases from colorectal cancer, 16 for hepatocellular carcinoma, 5 for various kinds of metastatic diseases, 3 for cholangiocellular carcinoma, 2 for hemangioendothelioma, and 1 patient for gallbladder cancer. In three patients liver resection was performed for benign diseases, such as focal nodular hyperplasia, hemangioma or hepatolithiasis. The different diagnoses were distributed homogeneously between the steroid and control groups. An extended right hepatectomy was performed in five patients and a formal left or right hepatectomy was performed in nine and eight patients, respectively. Nine patients received a segmental resection involving at least two segments, a segmentectomy was performed in seven patients and a wedge resection in five patients. The type and number of procedures were comparable between both groups.

Table I. Comparison of preoperative and intraoperative variables between the control and steroid group.

| Preoperative and intraoperative variables | Control group (n=22) | Steroid group (n=21) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65±8.9 | 60.7±13.4 | 0.149 |

| Gender (male/female) | 16/6 | 13/8 | 0.449 |

| Diagnosis (HCC/CCC/CMET/NCM/GBL/HEM/BEN) | 10/1/6/3/1/2/1 | 6/2/7/2/0/0/2 | 0.358 |

| Underlying liver disease (normal/hepatitis/steatosis) | 11/8/3 | 12/7/2 | 0.386 |

| Concomitant diseases | |||

| Diabetes | 8 | 5 | |

| Hypertension | 3 | 3 | |

| Previous systemic chemotherapy | 3 | 3 | |

| Previous intrahepatic chemotherapy | 1 | 1 | |

| Arrhythmia | 0 | 2 | |

| TACE | 1 | 2 | |

| COPD | 0 | 2 | |

| Total [no. (%)] | 16 (72%) | 18 (85%) | 0.295 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 48±8.1 | 44±7.2 | 0.132 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.92±0.4 | 0.97±0.6 | 0.756 |

| ALT (U/L) | 37±21 | 38±21 | 0.896 |

| AST (U/L) | 48±32 | 37±22 | 0.270 |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.02±0.04 | 1.02±0.05 | 0.926 |

| AT-III (%) | 84.5±15.3 | 83.6±16 | 0.894 |

| Operative procedures (Rhr/Lhr/ExRhr/Biseg/Seg/Wedge) | 6/3/1/6/3/3 | 2/6/4/3/4/2 | 0.146 |

| Operation time (min) | 421±112 | 378±97 | 0.191 |

| Ischemia time (min) | 29±17 | 48±18 | 0.134 |

| Blood loss (ml) | 585±436 | 487±245 | 0.125 |

| Transfusion (units) | |||

| Red blood cells | 1.1±0.8 | 0.8±0.9 | 0.321 |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 1.1±3.2 | 0.7±2.4 | 0.112 |

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; CCC, cholangiocellular carcinoma; CMET, colorectal metastasis; NCM, non-colorectal metastasis; GBL, gallbladder cancer; BEN, benign diseases; HEM, hemangioendothelioma; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Rhr, right hepatectomy; Lhr, left hepatectomy; ExRhr, extended right hepatectomy; Biseg, bisegmentectomy; Seg, segmentectomy; Wedge, wedge resection. Data are given as mean±SD.

Postoperative liver injury

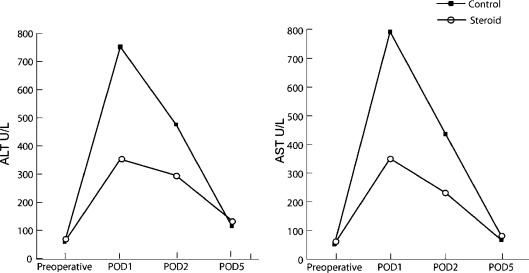

The degree of I/R injury of the liver was assessed by postoperative peak serum ALT and AST levels. The transaminase peak occurred within the first postoperative day in all patients. Patients treated with preoperative steroid pulse had a significantly lower peak ALT value when compared with the control group on POD1 (353±221 vs 752±345 U/L, p=0.002) and POD2 (295±120 vs 476±280 U/L, p=0.045). Similarly, peak AST values were significantly reduced in the steroid group when compared with patients receiving portal clamping alone on POD1 (351±269 vs 793±369 U/L, p=0.001) and POD2 (231±180 vs 436±210 U/L, p=0.040) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. .

Comparison of mean ALT and AST levels between the control and steroid groups.

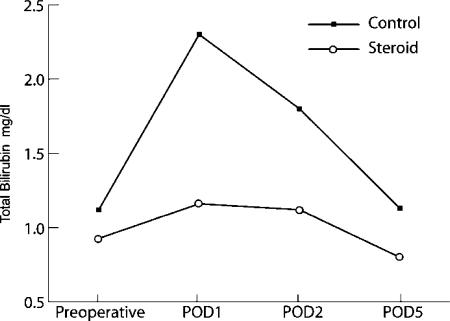

The postoperative bilirubin values were also significantly lower in the steroid group than in the control group on POD1 (1.16±0.54 vs 2.3±1.4 mg/dl, p=0.0001), POD2 (1.12±0.6 vs 1.8±1.1 mg/dl, p=0.004), and POD5 (0.8±0.3 vs 1.3±1.0 mg/dl, p=0.037) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. .

Comparison of mean postoperative total bilirubin levels between the control and steroid groups.

Coagulation parameters

Significant differences between the steroid and control groups were also observed for coagulant parameters. Prothrombin time was significantly prolonged in the control group compared with the steroid group on POD1 (1.28±0.19 vs 1.14±0.85 INR, p=0.06), POD2 (1.2±0.14 vs 1.11±0.07 INR, p=0.023).

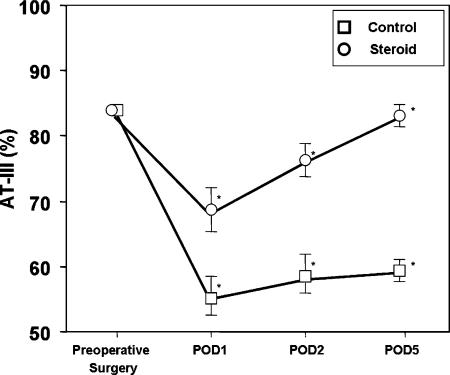

AT-III levels in both groups significantly decreased compared with the preoperative levels and reached their minimal levels on POD1. The AT-III levels in the control group were significantly lower than in the steroid group on POD1 (55±10 vs 68±13%, p=0.012), POD2 (58±10.6 vs 76±14%, p=0.01), and POD5 (59±11 vs 83±19%, p=0.02) (Figure 3). ANOVA with repeated measures revealed that the AT-III levels in the steroid group were significantly maintained compared with the control group (p<0.01).

Figure 3. .

Comparison of mean AT-III levels between the control and steroid groups.

Serum cytokines levels

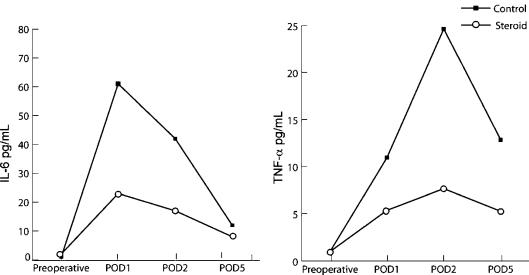

Il-6 serum levels in both groups reached a peak on POD1 and declined thereafter, TNF-α levels peaked later on POD2 and declined thereafter. IL-6 and TNF-α levels in the steroid group were significantly lower than in the control group at each time point measured after the surgery (Table II, Figure 4).

Table II. Serum cytokine levels.

| Cytokines | Control group (n=22) | Steroid group (n=21) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 preoperative | 1±0.5 | 1±0.4 | 0.810 |

| IL-6 POD1 | 61±16.4 | 23±18.9 | 0.001 |

| IL-6 POD2 | 42.3±13 | 17±11 | 0.025 |

| IL-6 POD5 | 30.2±6.8 | 11.3±8.6 | 0.012 |

| TNF-α preoperative | 0.8±0.4 | 0.7±0.3 | 0.840 |

| TNF-α POD1 | 11.4±8.8 | 5.4±7.2 | 0.040 |

| TNF-α POD2 | 24.7±12 | 7.7±8.2 | 0.005 |

| TNF-α POD5 | 12.9±6 | 5.3±4.1 | 0.006 |

Data are given as mean±SD. POD, postoperative day.

Figure 4. .

Comparison of mean IL-6 and TNF-α levels between the control and steroid groups.

Postoperative complications and hospital stay

Two patients (9.5%) in the steroid group and eight patients (37%) in the control group had one or more complications within 30 days after surgery. The postoperative complications are summarized in Table III. Significantly fewer patients in the steroid group had infectious complications, defined as positive culture of blood, sputum, or other fluids in the presence of clinical evidence of infection (p=0.027) 18. There was no death within 30 days of surgery in either group. Patients in the steroid group experienced a reduced hospital stay compared with the control group (p=0.040).

Table III. Postoperative complications in the control and steroid groups.

| Postoperative complications | Control group (n=22) | Steroid group (n=21) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemorrhage [no. (%)] | 1 (4.5%) | 0 | 0.512 |

| Bile leakage [no. (%)] | 2 (9%) | 0 | 0.256 |

| Transitory hepatic decompensation [no. (%)] | 1 (4.5%) | 1 (4.7%) | 0.744 |

| Cardiac [no. (%)] | 2 (9%) | 0 | 0.256 |

| Pleural effusion [no. (%)] | 1 (4.5%) | 0 | 0.512 |

| Infective complications [patients no. (%)]* | 7 (31%) | 1 (4.7%) | 0.027 |

| Hospital stay [median (range)] | 8 (5–39) | 6 (5–21) | 0.040 |

*Only a single infective event from each patient was counted as an infective complication.

Discussion

Hepatic injury and failure secondary to warm I/R injury remains an important clinical issue 19. It occurs in a variety of situations including transplantation, trauma, shock, and liver surgery, when hepatic inflow occlusion (Pringle maneuver) or inflow and outflow occlusion (total vascular exclusion) are induced to minimize blood loss while dividing the liver parenchyma 20. Therefore, there is a considerable interest in the prevention of hepatic I/R injury.

The first reports on the protective effects of steroids on liver ischemia were published in 1975 12. Santiago-Delpin and Figueroa found that methylprednisolone treatment before hepatic occlusion resulted in increased animal survival and reduced liver damage, as demonstrated by histology, when compared with ischemic controls. Even though the exact molecular-biologic mechanisms of steroid action on hepatic I/R injury remain partially unknown, it is supposed that steroid therapy suppresses liver injury by a variety of mechanisms, including increased tissue blood flow and suppression of oxygen free radicals, lysosomal proteases, suppression of calpain µ activation, reduced cytokine production and apoptotic activity 10,11,12,13,14.

Based on their biological effects, routine perioperative administration of steroids has been advocated to reduce hepatic ischemic injury. Although, some series recommended the preoperative administration of steroids 8,9, the use of corticosteroids in hepatic surgery remains controversial and clinical benefits are still uncertain 15,16,17. This disagreement probably stems from the limited number of patients, their dosage, administration schedule, and endpoints of clinical outcome in different studies. This prospective randomized study in an unselected group of patients establishes preoperative methylprednisolone administration as a protective strategy against I/R injury in humans. Postoperative indicators of hepatocyte damage and recovery (aminotransferase, bilirubin) were significantly modified by steroid administration.

Several clinical trials in patients undergoing elective cardiothoracic or gastrointestinal surgery, as well as in cases of septic shock 21, have evaluated the efficacy of steroid administration. Results suggest that several aspects of the surgical stress responses, organ dysfunction, and postoperative recovery are improved by administering preoperative steroids.

The potential side effects of perioperative steroid administration have been of much concern. However, a meta-analysis with data from more than 1900 patients concluded that perioperative methylprednisolone administration in major surgery, trauma, and spinal cord injury was not associated with any adverse effects 22.

The liver plays an important role in maintaining the balance between thrombosis and bleeding. Major liver surgery is often characterized by modifications in hemostatic balance 23,24. Postoperative liver dysfunction following removal of significant hepatic volume, vascular clamping, and heavy hemorrhage may result in a hypocoagulable state. On the other hand, a hypercoagulable status can result from impaired synthesis of anticoagulants, hemodilution, and excessive activation of inflammatory response 24. AT-III is known to play a fundamental role in the anticoagulant system by preventing thrombin formation and inhibiting coagulation by down-regulating procoagulant activities 25. Decrease of AT-III after major surgery is associated with an increased risk of complications and mortality 26,27. In addition to the anticoagulant effects, AT-III has important anti-inflammatory activity 28. Harada et al. have recently demonstrated that AT-III reduces I/R induced liver injury in rats by increasing the COX-1-mediated production of PGI1 and PGE229. Shimada et al. reported that preoperative administration of AT-III concentrates significantly decreases postoperative complications such as liver failure and hyperbilirubinemia after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma 30. Methylprednisolone administration resulted in a better preservation of coagulative function as shown by the preserved prothrombin time and attenuated the reduction of AT-III. As described previously 31, methylprednisolone pretreatment attenuates the decrease in AT-III by reducing the postoperative production of the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 which occurred after hepatic resection. Similar results were previously described for esophagectomy 32. IL-6 certainly has a significant role in the activation of the coagulation cascade: in fact this cytokine is thought to act over hemostasis activating the extrinsic pathway through tissue factor expression 33. It is of clinical interest that preoperative steroid administration before hepatic resection may maintain coagulant/anticoagulant homeostasis, attenuating postoperative cytokine levels.

Elevated plasma levels of IL-6 have been reported to correlate with postoperative morbidity and mortality 34, and the cytokine TNF-α – one of the main mediators of hepatic I/R injury – is known to have both local deleterious effects on the hepatocytes and to mediate remote organ damage 35. Inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α are also known to play a critical role in liver generation 36,37, and on the other hand, hyperstimulation of IL-6 has been suggested to inhibit liver regeneration 38. Serum levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α were significantly reduced in the steroid group. This trial confirmed the effect of suppression of surgical stress by preoperative steroid administration in patients undergoing hepatic resection.

Infectious complications were less frequent in the steroid group than in the control group (31% vs 4.7%). It is of great interest that the possible clinical effects of preoperative steroid administration include the prevention of bacterial translocation and immunosuppression induced by hepatic resection itself. Yamashita et al. 16 have previously reported that the administration of steroids in hepatic resection results in decreased values of immunosuppressive acid protein, and postoperative positive rate of serum Candida antigen, which is a marker of bacterial translocation 39. Similar findings were reported in other operations, including esophagectomy 40. In addition, the hospital stay was significantly shorter in the steroid group and adverse effects of steroid use, such as abnormality in glucose tolerance and delay in wound healing, did not occur in any of our patients.

The steroid administration regimen used in this study was based on the following considerations. The anti-inflammatory actions of methylprednisolone are five times as strong as those of cortisol, but it has a reduced activity on electrolytes 41. The duration of methylprednisolone's biologic action is 36 h and the half-life in the blood is 2.8 h 42. As a result, both early and late phase of hepatic I/R injury should be covered 43. Intravenous administration of 500 mg of methylprednisolone has been confirmed to result in a methylprednisolone level of > 1 µg/ml in blood or > 10 µg/ml in liver tissue 16, and > 10 µg/ml of methylprednisolone can significantly suppress lymphocyte blastoid transformation, immunoglobulin production, and NK cell activity 42. This prospective randomized study suggests that preoperative methylprednisolone administration may represent a valid protective strategy against hepatic ischemia reperfusion and confirmed the efficacy and safety of steroids in reducing surgical stress in patients undergoing hepatic resection.

Footnotes

Presented to the Annual Meeting of the American Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association (AHPBA), Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, April 14–17, 2005 (Session: Young Investigator Award).

References

- 1.Wobbes T, Bemelmans BL, Kuypers JH, Beerthuizen GI, Theeuwes AG. Risk of postoperative septic complications after abdominal surgery treatment in relation to perioperative blood transfusion. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;171:1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makuuchi M, Mori T, Gunven P, Yamazaki S, Hasegawa H. Safety of hemihepatic vascular occlusion during resection of the liver. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1987;164:155–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagorney DM, van Heerden JA, Ilstrup DM, Adson MA. Primary hepatic malignancy: surgical management and determinants of survival. Surgery. 1989;10:740–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsao JI, Loftus JP, Nagorney DM, Adson MA, Ilstrup DM. Trends in morbidity and mortality of hepatic resection for malignancy: a matched comparative analysis. Ann Surg. 1994;220:199–205. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199408000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huguet C, Gavelli A, Bona S. Hepatic resection with ischemia of the liver exceeding one hour. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;178:454–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ezaki T, Seo Y, Tomoda H, Furusawa M, Kanematsu T, Sugimachi K. Partial hepatic resection under intermittent hepatic inflow occlusion in patients with chronic liver disease. Br J Surg. 1992;79:224–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selzener N, Rudiger H, Graf R, Clavien P. Protective strategies against ischemic injury of the liver. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:917–36. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torzilli G, Makuuchi M, Inoue K, Takayama T, Sakamoto Y, Sugawara Y, et al. No-mortality liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients: is there a way? A prospective analysis of our approach. Arch Surg. 1999;134:984–92. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.9.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torzilli G, Makuuchi M, Midorikawa Y, Sano K, Inoue K, Takayama T, et al. Liver resection without total vascular exclusion: hazardous or beneficial? An analysis of our experience. Ann Surg. 2001;233:167–75. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200102000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang M, Sakon M, Umeshita K, Okuyama M, Shiozaki K, Nagano H, et al. Prednisolone suppresses ischemia-reperfusion injury of the rat liver by reducing cytokine production and calpain µ activation. J Hepatol. 2001;34:278–83. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)00017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glanemann M, Strenziok R, Kuntze R, Munchow S, Dikopoulos N, Lippek F, et al. Ischemic preconditioning and methylprednisolone both equally reduce hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. Surgery. 2004;135:203–14. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figueroa I, Santiago-Delpin EA. Steroid protection of the liver during experimental ischemia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:368–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiappa AC, Makuuchi M, Zbar AP, Biella F, Vezzoni A, Torzilli G, et al. Protective effect of methylprednisolone and of intermittent hepatic pedicle clamping during liver vascular inflow occlusion in the rat. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:1439–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glanemann M, Munchow S, Schirmeier A, Al-Abadi H, Lippek F, Langrehr JM, et al. Steroid administration before partial hepatectomy with temporary inflow occlusion does not influence cyclin D1 and Ki-67 related liver regeneration. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2004;389:380–6. doi: 10.1007/s00423-004-0507-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muratore A, Ribero D, Ferrero A, Bergero R, Capussotti L. Prospective randomized study of steroids in the prevention of ischaemic injury during hepatic resection with pedicle clamping. Br J Surg. 2003;90:17–22. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamashita Y, Shimada M, Hamatsu T, Rikimaru T, Tanaka S, Shirabe K, et al. Effects of preoperative steroid administration on surgical stress in hepatic resection. Arch Surg. 2001;136:328–33. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.3.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimada M, Saitoh A, Kano T, Takenaka K, Sugimachi K. The effects of a perioperative steroid pulse on surgical stress in hepatic resection. Int Surg. 1996;81:49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emori TG, Culver DH, Horan TC, Jarvis WR, White JW, Olson DR, et al. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System (NNIS): description of surveillance methods. Am J Infect Control. 1991;19:13–15. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(91)90157-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu DL, Jeppson B, Hakansson CH, Odslius R. Multiple-system organ damage resulting from prolonged hepatic inflow interruption. Arch Surg. 1996;131:442–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430160100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farmer DG, Amersi F, Kupiec-Weglinski JW, Busuttil RW. Current status of ischemia reperfusion injury in the liver. Transplant Rev. 2000;14:106–26. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holte K, Kehler H. Perioperative single dose glucocorticoid administration: pathophysiologic effects and clinical implications. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:694–712. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sauerland S, Nagelschmidt M, Mallmann P, Neugebauer EA. Risks and benefits of preoperative high dose methylprednisolone in surgical patients: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2000;23:449–61. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200023050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsuji K, Eguchi Y, Kodama M. Postoperative hypercoagulable state followed by hyperfibrinolysis related to wound healing after hepatic resection. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:230–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinischalchi A, Begliomini B, De Pietri L, Braglia V, Gazzi M, Masetti M, et al. Increased prothrombin time and platelet counts in living donor right hepatectomy: implications for epidural anesthesia. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1144–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberg RD. Biochemistry of heparin antithrombin interactions, and the physiologic role of this natural anticoagulant mechanism. Am J Med. 1989;87:2S–9S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(89)80523-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson R, Mammen E, Robson M, Heggers J, Soulier G, DePoli P. Antithrombin, prekallikrein, and fibronectin levels in surgical patients. Arch Surg. 1986;121:635–40. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1986.01400060029002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto K, Yamagishi M, Sasaki T, Nakano M, Kurosawa H. Heparin and antithrombin III levels during cardiopulmonary bypass: correlation with subclinical plasma coagulation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:804–5. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)90752-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roemisch J, Gray E, Hoffmann JN, Wiedermann CJ. Antithrombin: a new look at the actions of a serine protease inhibitor. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2002;13:657–70. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harada N, Okajima K, Uchiba M, Kushimoto S, Isobe H. Antithrombin reduces ischemia/reperfusion-induced liver injury in rats by activation of cyclooxygenase-1. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:550–8. doi: 10.1160/TH03-07-0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimada M, Matsumata T, Kamakura T, Hayashi H, Urata K, Sugimachi K. Modulation of coagulation and fibrinolysis in hepatic resection: a randomized prospective control study using antithrombin III concentrates. Thromb Res. 1994;74:105–14. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pulitanò C, Aldrighetti L, Finazzi R, Arru M, Catena M, Ferla G. Inhibition of cytokine response by methylprednisolone attenuates antithrombin III reduction following hepatic resection. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:1199–200. doi: 10.1160/TH06-01-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsutani T, Onda M, Sasajima K, Miyashita M. Glucocorticoid attenuates a decrease of antithrombin III following major surgery. J Surg Res. 1998;79:158–63. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stouthard JM, Levi M, Hack CE, Veenhof CH, Romijn HA, Sauerwein HP, et al. Interleukin-6 stimulates coagulation, not fibrinolysis, in humans. Thromb Haemost. 1996;76:738–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Damas P, Ledoux D, Nys M, Vrindts Y, De Groote D, Franchimont P, et al. Cytokine serum level during severe sepsis in human IL-6 as a marker of severity. Ann Surg. 1992;215:356–62. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199204000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colletti LM, Remick DG, Burtch GD, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM, Campbell DA. Role of tumor necrosis factor-a in the pathophysiologic alterations after hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1936–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI114656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fujita J, Marino MW, Wada H, Jungbluth AA, Mackrell PJ, Rivadeneira DE, et al. Effect of TNF gene depletion on liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. Surgery. 2001;129:48–54. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.109120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallenius V, Wallenius K, Jansson JO. Normal pharmacologically-induced, but decreased regenerative liver growth in interleukin-6-deficient “IL-6 knockout” mice. J Hepatol. 2000;33:967–74. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wustefeld T, Rakemann T, Kubicka S, Manns MP, Trautwein C. Hyperstimulation with interleukin 6 inhibits cell cycle progression after hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology. 2000;32:514–22. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.16604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shirabe K, Takenaka K, Yamamoto K, Kawahara N, Itasaka H, Nishizaki T, et al. Impaired systemic immunity and frequent infection in patients with candida antigen after hepatectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimada H, Ochiai T, Okazumi S, Matsubara H, Nabeya Y, Miyazawa Y, et al. Clinical benefits of steroid therapy on surgical stress in patients with esophageal cancer. Surgery. 2000;128:791–8. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.108614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stubbs SS. Corticosteroids and bioavailability. Transplant Proc. 1975;7:11–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serracino-Inglott F, Habib N, Mathie R. Hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury Am J Surg. 2001;181:160–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00573-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Webel ML, Ritts RE, Jr, Taswell HF, Danadio JV, Jr, Woods JE. Cellular immunity after intravenous administration of methylprednisolone. J Lab Clin Med. 1974;83:383–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]