Abstract

The molecular machines that mediate cell fusion are unknown. Previously, we identified a multispanning transmembrane protein, Prm1 (pheromone-regulated membrane protein 1), that acts during yeast mating (Heiman, M.G., and P. Walter. 2000. J. Cell Biol. 151:719–730). Without Prm1, a substantial fraction of mating pairs arrest with their plasma membranes tightly apposed yet unfused. In this study, we show that lack of the Golgi-resident protease Kex2 strongly enhances the cell fusion defect of Prm1-deficient mating pairs and causes a mild fusion defect in otherwise wild-type mating pairs. Lack of the Kex1 protease but not the Ste13 protease results in similar defects. Δkex2 and Δkex1 fusion defects were suppressed by osmotic support, a trait shared with mutants defective in cell wall remodeling. In contrast, other cell wall mutants do not enhance the Δprm1 fusion defect. Electron microscopy of Δkex2-derived mating pairs revealed novel extracellular blebs at presumptive sites of fusion. Kex2 and Kex1 may promote cell fusion by proteolytically processing substrates that act in parallel to Prm1 as an alternative fusion machine, as cell wall components, or both.

Introduction

Cell fusion is an important developmental event, from sperm–egg fusion during fertilization to syncytium formation in the development of placenta, muscle, and certain hematopoietic cell types. Although detailed mechanistic characterizations have been performed for virus–cell fusion and vesicle–organelle fusion, the molecular events mediating cell–cell fusion are poorly understood. In virus and vesicle fusion, a protein machine— a fusase—assembles between the fusing bilayers such that it spans both membranes (Hernandez et al., 1996). For influenza virus, the fusase is the hemagglutinin protein, which is anchored in the viral membrane and inserts itself into the target membrane (Ramalho-Santos and de Lima, 1998; Skehel and Wiley, 2000), whereas for vesicle–organelle fusion, the interaction of cognate SNARE family transmembrane proteins results in the assembly of a multiprotein complex anchored in both vesicle and target membranes (Weber et al., 1998). Hemagglutinin and the SNARE complex each adopt a coiled-coil structure that undergoes a series of conformational changes to winch the two bilayers into close proximity (Wilson et al., 1981; Sutton et al., 1998). During this process, the bilayer structure becomes distorted, and water separating the apposing membranes is squeezed out, initiating fusion (Hughson, 1995; Harbury, 1998).

A similar fusase mediates cell fusion during placental development: syncytin, a protein encoded by a retrovirus-derived gene, is necessary and sufficient for placental cell fusion (Mi et al., 2000). However, no analogous fusases have been identified in muscle precursors, sperm or egg, or other cells that fuse. Over a dozen proteins required for myoblast or osteoclast/macrophage fusion have been identified, but many of these proteins promote early steps, including cell migration and adhesion, rather than the later step of cell fusion (Han et al., 2000; Dworak and Sink, 2002). Likewise, in sperm–egg fusion, the fertilin complex was initially recognized as bearing hallmarks of a fusase (it contains a hydrophobic peptide capable of inserting into a membrane, and experimentally blocking fertilin function prevents fusion), yet fertilin knockout mice are primarily defective in sperm migration into the oviduct and binding to the zona pellucida that surrounds the egg, with a much weaker defect at the final step of cell fusion (Blobel et al., 1992; Cho et al., 1998, 2000).

A few proteins likely to act late in cell fusion, possibly at the ultimate step of membrane fusion, have been identified. EFF-1, a single-pass transmembrane protein, is required for syncytia formation in the hypodermal cells of Caenorhabditis elegans (Mohler et al., 2002) and, when ectopically expressed, is sufficient to fuse cells that do not normally fuse (Shemer et al., 2004; del Campo et al., 2005; Podbilewicz et al., 2006), thus making it an excellent candidate fusase. Two proteins, CD9 and CRISP-1, are important for sperm–egg fusion and seem to act after the initial steps of cell adhesion. CD9 is a multispanning membrane protein in the oocyte plasma membrane, and oocytes from mice lacking CD9 adhere normally to sperm but do not fuse with them (Kaji et al., 2000; Le Naour et al., 2000; Miyado et al., 2000). CRISP-1 is a peripherally associated membrane protein on the surface of sperm that, when blocked, prevents sperm–egg fusion but not adhesion (Cuasnicu et al., 2001).

Yeast mating offers a genetically powerful system in which to identify factors controlling the late steps of cell fusion. During yeast mating, haploid cells of mating types MATa and MATα secrete pheromone (MATa cells make a-factor, and MATα cells make α-factor), which is detected by a G-protein–coupled receptor on the complementary cell type, initiating a MAPK signaling cascade that results in G1 cell cycle arrest, polarized growth in the direction of highest pheromone concentration, and transcriptional up-regulation of ∼100 genes (Herskowitz, 1995). The mating partners adhere to one another through interactions in the cell wall to produce a mating pair. Finally, in a process whose molecular details have only begun to come to light, a small region of the cell wall at the interface between the mating partners is degraded, the mating partners' plasma membranes become apposed, and, finally, cell fusion occurs.

Numerous attempts to identify the cell fusion machinery have identified factors that are required for cell wall degradation at multiple steps, from regulating cell wall remodeling and secretory vesicle trafficking to the maintenance of osmotic integrity (Trueheart et al., 1987; Kurihara et al., 1994; Philips and Herskowitz, 1997, 1998; Brizzio et al., 1998). However, none of these genetic screens have identified genes that seem to act at the final step in cell fusion: the merging of plasma membrane bilayers. Previously, we designed a reverse genetic approach aimed at uncovering the fusion machinery (Heiman and Walter, 2000). We reasoned that the cell fusion machinery that acts during mating probably includes a transmembrane protein expressed specifically in response to mating pheromone. We began studying pheromone-regulated membrane proteins (PRMs), and, using the data-mining program Webminer (http://genome-www.stanford.edu/webminer), we identified the membrane protein most induced by pheromone, Prm1, and characterized its role in membrane fusion (Heiman and Walter, 2000).

Prm1 is a multispanning membrane protein that is not expressed under standard growth conditions but is induced in both mating types in response to pheromone (Heiman and Walter, 2000). It localizes to the site of cell fusion. If either mating partner lacks Prm1, ∼10% of mating pairs fail to fuse, but if both mating partners lack Prm1, ∼50% of mating pairs fail to fuse (Heiman and Walter, 2000). When we examined Δprm1 × Δprm1 mating pairs by electron microscopy, we observed a morphology never before seen. In some mating pairs, the cell wall had been degraded, and the plasma membranes had become apposed yet failed to fuse (Heiman and Walter, 2000). This result indicates that Prm1 facilitates the final step in cell fusion, that of plasma membrane fusion (White and Rose, 2001).

However, Prm1 cannot constitute the complete machinery. Even in its absence, about half of all mating pairs still fuse, indicating that Prm1 either facilitates the action of a yet unidentified fusase or that Prm1 is itself a fusase and one or more alternative fusases exist. Intriguingly, Δprm1 mating pairs frequently lyse when attempting to fuse, suggesting the remaining presence of an active but dysregulated fusase (Jin et al., 2004). Among Δprm1 mating pairs that are capable of fusion, the initial permeance and expansion rate of the fusion pore are slightly decreased, indicating a role for Prm1 in fusion pore opening; however, the subtlety of this defect again points to the presence of a redundant fusion activity (Nolan et al., 2006). The notion of an additional fusion machinery that is regulated by or acts in parallel to Prm1 implies that the disruption of additional components should create more severe blocks to membrane fusion than can be achieved by disrupting PRM1 alone. In this study, we have exploited this prediction to design a genetic screen that led to the identification of a gene acting in conjunction with PRM1 to promote cell fusion.

Results

A genetic screen for enhancers of the Δprm1 mating defect identifies mutations in KEX2

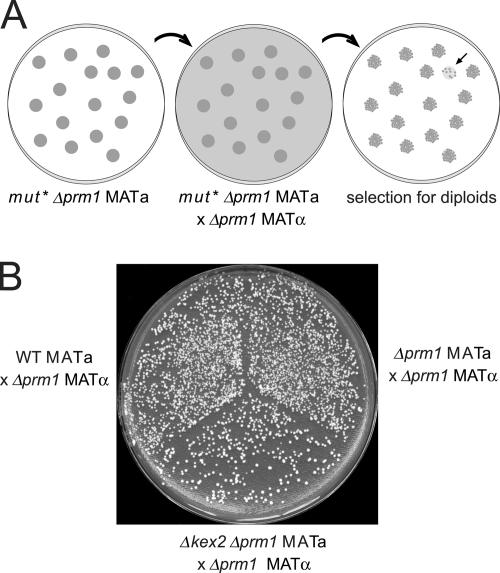

To identify factors required for Prm1-independent cell fusion, we screened for mutants that enhance the Δprm1 × Δprm1 mating defect. We performed random mutagenesis of a Δprm1 MATa strain bearing a selectable marker. We then plated the mutants, allowed them to form small colonies, and replica plated them to a lawn of Δprm1 MATα cells bearing a different selectable marker. We allowed mating to occur and replica plated to a medium selective for auxotrophic markers of both parent strains, thus allowing the growth only of diploids that arose during mating. Each mutant colony from the original plate resulted on the final selective plate in a small patch with many diploid microcolonies emerging from it as papillae (Fig. 1 A). The density of diploid papillae within each patch reflected the mating efficiency of the mutant that gave rise to it. Using this replica mating assay, we screened for mutants in the Δprm1 background that mated poorly to a Δprm1 partner.

Figure 1.

Replica mating strategy to isolate enhancers of Δprm1. (A) A Δprm1 MATa strain was mutagenized and plated to form colonies. Colonies were replica plated to a lawn of Δprm1 MATα mating partner on a YPD plate and incubated at 30° for 8 h. The mating was then replica plated to medium selective for diploids. Mutant colonies yielding a low density of diploid papillae (arrow in right panel) were identified. (B) Patches of WT, Δprm1, and Δprm1 Δkex2 MATa haploids were replica mated as in A to a lawn of Δprm1 MATα mating partner. The resulting diploid papillae are shown.

In addition to mutants in the PRM1-independent fusion pathway, we expected to find sterile mutants not relevant to this study. To distinguish these classes, we tested the ability of each mutant to mate to a wild-type (WT) partner. Mutants that mated poorly to a WT partner were considered sterile and were discarded.

To further characterize the remaining mutants, we performed a backcross to ensure that the observed phenotypes segregated as single mutations. To our surprise, 4/10 mutants revealed a new phenotype after backcrossing. MATα progeny bearing these mutations, but not MATa progeny, displayed complete sterility whether mated to a WT or Δprm1 partner. Therefore, we assumed that a set of mutations enhancing the Δprm1 phenotype in MATa cells causes sterility in MATα cells. Because sterility was easier to score, we used complementation cloning to isolate the gene responsible for the MATα-specific sterility in one of the mutants. The remaining mutants were not characterized further. We recovered four genomic fragments that restored mating to this mutant. These fragments overlapped in a region containing the coding sequence of KEX2.

Kex2 functions as a protease in the Golgi apparatus that processes several proteins traversing the secretory pathway, including the α-factor mating pheromone (Julius et al., 1983; Fuller et al., 1989). This essential role of Kex2 in the processing of prepro–α-factor readily explains why MATα Δkex2 mutants are sterile. In contrast, Kex2 does not process the a-factor mating pheromone, and MATa Δkex2 mutants do not display pheromone response defects, making it unlikely that the observed mating defect results from impairment of the pheromone signaling pathway (Leibowitz and Wickner, 1976).

As expected, a MATα Δkex2 Δprm1 mutant was sterile in our assay (unpublished data). In contrast, a MATa Δkex2 Δprm1 mutant mated efficiently to a WT partner but poorly to a Δprm1 partner. Although we could not detect the weakly penetrant Δprm1 × Δprm1 phenotype by replica mating, the more severe phenotype of a Δprm1 Δkex2 × Δprm1 mating was readily apparent (Fig. 1 B).

Loss of Kex2 synergizes with the loss of Prm1 to impair mating at the cell fusion step

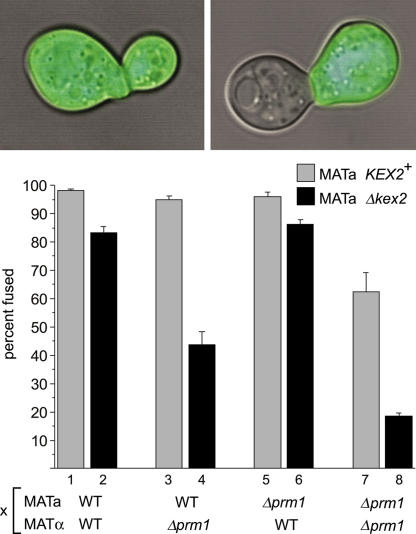

To learn whether Kex2 acts in cell fusion, we used a quantitative cell fusion assay as previously described (Heiman and Walter, 2000). Mating partners carrying deletions in PRM1, KEX2, both, or neither were mixed and allowed to mate. One partner expressed soluble cytoplasmic GFP to serve as a marker for cytoplasmic mixing. Mating pairs were examined by fluorescence microscopy. Mating pairs with GFP throughout their volume were scored as fused, whereas mating pairs in which GFP remained restricted to one partner were scored as unfused (Fig. 2). By counting the ratio of fused to total mating pairs, we quantitated the efficiency of cell fusion. This assay differs from replica mating in that it scores only the cell fusion step of mating rather than the entire mating process.

Figure 2.

Δkex2 enhances the Δprm1 cell fusion defect. (top) Δkex2 MATa cells were mixed with WT MATα cells expressing soluble cytosolic GFP as a reporter of cytoplasmic mixing between mating partners. This mixture was applied to a nitrocellulose filter and incubated at 30°C for 3 h on a YPD plate. Fluorescent micrographs showing the GFP-stained cytoplasm were superpositioned over brightfield images of the mating pairs. (bottom) Mating mixes in which mating partners carried deletions of PRM1, KEX2, both, or neither were prepared as described for the top panel. In all cases, the MATα partner carried soluble cytosolic GFP. Mating pairs were visually identified and scored with regard to cell fusion by microscopy. Bars represent the mean percentages of mating pairs that scored as fused in three independent experiments. Error bars represent SD. During each experiment, 300 mating pairs per mating mix were counted. All matings are written in the form MATa × MATα: WT × WT, 98.2 ± 0.6%; Δkex2 × WT, 83.2 ± 2.3%; WT × Δprm1, 94.8 ± 1.4%; Δkex2 × Δprm1, 43.6 ± 4.6%; Δprm1 × WT, 95.9 ± 1.6%; Δprm1 Δkex2 × WT, 86.3 ± 1.6%; Δprm1 × Δprm1, 62.4 ± 6.8%; and Δprm1 Δkex2 × Δprm1, 18.5 ± 1.2%.

In agreement with our previous results (Heiman and Walter, 2000), we observed in control mating reactions that the deletion of PRM1 from both mating partners creates a substantial block to cell fusion compared with WT (Fig. 2, compare bar 1 with 7), whereas the deletion of PRM1 from either mating partner alone produces a barely perceptible decrease in fusion efficiency (Fig. 2, compare bars 1, 3, and 5; Heiman and Walter, 2000).

Interestingly, the loss of KEX2 in the MATa partner alone decreases fusion by 15% compared with WT (Fig. 2, bars 1 and 2), thereby demonstrating a role for Kex2 in MATa cells in cell fusion. Although the defect was small, it was highly reproducible. Because of the role of Kex2 in α-factor processing, we could not reciprocally assay MATα Δkex2 mutants.

We observed a markedly greater Kex2 dependency of cell fusion in mating reactions in which both partners lacked Prm1. The efficiency of cell fusion in Δkex2 Δprm1 × Δprm1 mating pairs is 70% lower than that in Δprm1 × Δprm1 mating pairs (Fig. 2, bars 7 and 8). Thus, the Δkex2 mutation unilaterally and potently enhances the otherwise weakly penetrant Δprm1 fusion phenotype.

The Kex2 dependency of mating reactions in which only one partner expresses Prm1 proved more complicated. Mating pairs in Δkex2 × Δprm1 mating reactions fuse with a much reduced efficiency compared with WT × Δprm1 mating reactions (Fig. 2, bars 3 and 4). In contrast, Δkex2 Δprm1 × WT mating reactions do not differ greatly from Δprm1 × WT matings (Fig. 2, bars 5 and 6). In other words, the Δkex2 mutation produces a much stronger effect when placed in trans rather than in cis to the Δprm1 mutation.

Processing by Kex2 and Kex1 but not Ste13 synergizes with Prm1 in cell fusion

The Kex2 protease has been extensively characterized (Rockwell et al., 2002). In brief, Kex2 acts as a furin-type endopeptidase that cleaves substrate proteins at dibasic sequence LysArg sites as the proteins traverse the Golgi apparatus. For many substrates such as α-factor, the initial Kex2 cleavage is followed by the action of two exopeptidases, which trim the newly exposed ends: Kex1, a carboxypeptidase, removes the LysArg sequence from the C terminus of the N-terminal fragments, whereas Ste13, an aminopeptidase, removes pairs of residues (preferring X-Ala sequences) from the N terminus of the C-terminal fragments.

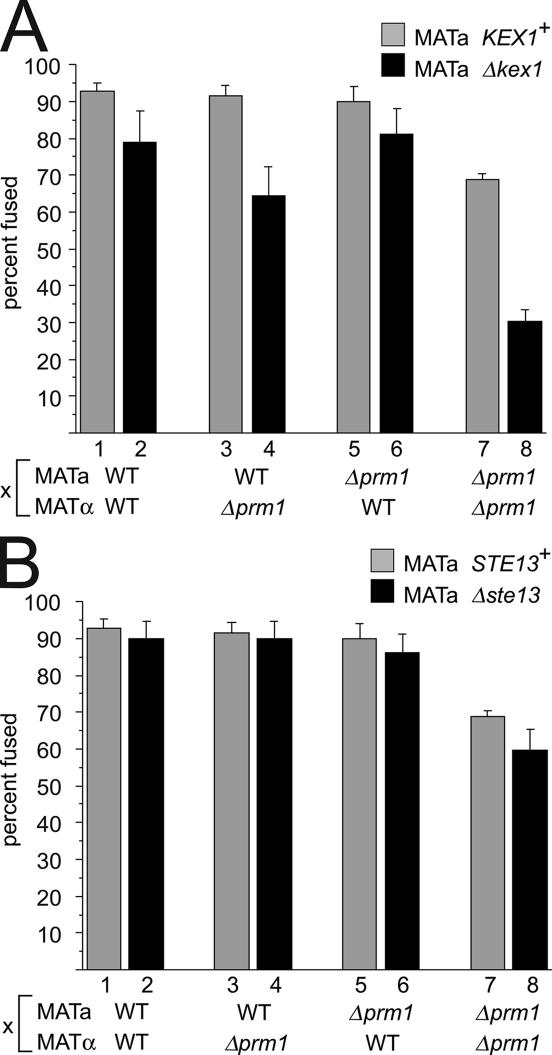

To test whether Kex1 or Ste13 also affects cell fusion, we subjected Δkex1 and Δste13 mutants to the same genetic analysis we used with Δkex2 mutants. We conducted mating reactions in which the partners lacked either Prm1 or Kex1 in all combinations or Prm1 or Ste13 in all combinations and assayed the resulting mating pairs for fusion using the GFP mixing assay.

As shown in Fig. 3, a Δkex1 mutant displays a slight but reproducible fusion defect when crossed to a WT partner (Fig. 3 A, bars 1 and 2). This defect was enhanced when we introduced a Δprm1 mutation in trans but not in cis (Fig. 3 A, bars 3 and 4 and bars 5 and 6, respectively). Finally, the most severe defect occurred when we introduced a Δkex1 mutation into a Δprm1 × Δprm1 cross, which reduced the number of successful fusions by more than half (Fig. 3 A, bars 7 and 8). Thus, the effects of the Δkex1 mutation qualitatively phenocopy those of the Δkex2 mutation, although the Δkex1 mutation produces slightly milder fusion defects.

Figure 3.

Δkex1 but not Δste13 enhances the Δprm1 cell fusion defect. Mating mixes in which mating partners carried deletions of PRM1, KEX1, or STE13 singly or in combination were subjected to filter matings followed by microscopic inspection of mating pairs, and fusion efficiencies were quantitated using the GFP mixing assay as described in Fig. 2. All matings presented in this figure were conducted in parallel, and three independent trials were performed, with 300 mating pairs per mating mix counted each time. All matings are written in the form MATa × MATα. (A) Matings with deletions of KEX1: WT × WT, 92.9 ± 2.3%; Δkex1 × WT, 78.8 ± 8.6%; WT × Δprm1, 91.5 ± 2.8%; Δkex1 × Δprm1, 64.5 ± 7.7%; Δprm1 × WT, 90 ± 4.2%; Δprm1 Δkex1 × WT, 81.3 ± 6.9%; Δprm1 × Δprm1, 68.7 ± 1.6%; and Δprm1 Δkex1 × Δprm1, 30.4 × 3.0%. (B) Matings with deletions of STE13: WT × WT, 92.9 ± 2.3%; Δste13 × WT, 90.1 ± 4.5%; WT × Δprm1, 91.5 ± 2.8%; Δste13 × Δprm1, 90.1 ± 4.5%; Δprm1 × WT, 90 ± 4.2%; Δprm1 Δste13 × WT, 86.1 ± 5.2%; Δprm1 × Δprm1, 68.7 ± 1.6%; and Δprm1 Δste13 × Δprm1, 59.7 ± 5.6%. Error bars represent SD.

In contrast, the deletion of STE13 from a WT × WT mating reaction produced no substantial difference in cell fusion (Fig. 3 B, bars 1 and 2). Furthermore, Δste13 did not enhance the Δprm1 fusion phenotype when placed in trans or in cis (Fig. 3 B, bars 3 and 4 and bars 5 and 6, respectively). Finally, when introduced into a Δprm1 × Δprm1 mating, the Δste13 mutation did not appreciably reduce mating (Fig. 3 B, bars 7 and 8). These results demonstrate that the complement of proteases required to promote cell fusion in MATa cells is distinguishable from that required for α-factor processing.

The Δkex2 fusion defect is not caused by inactivation of a previously known substrate or either of two novel substrates

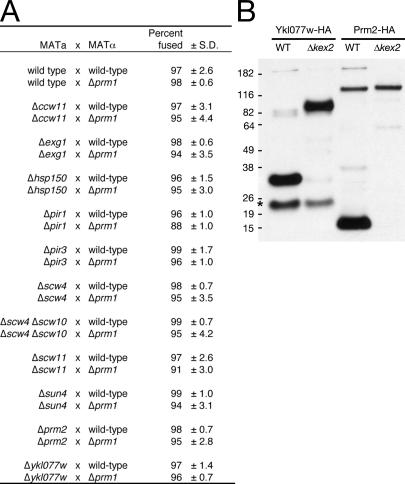

The dependency of cell fusion on Kex2 and Kex1 suggests the existence of a proteolytically activated protein that facilitates fusion. To try to identify such a protein, we generated strains carrying deletions of known Kex2 substrates and assayed their fusion efficiencies.

Among known Kex2 substrates are cell wall glucosidases such as Scw4 and Scw10 (Basco et al., 1990; Mrsa et al., 1997; Cappellaro et al., 1998) and cell wall structural components such as Hsp150 (Russo et al., 1992). We systematically generated deletions in eight known Kex2 substrates and mated each mutant to a WT or Δprm1 mating partner (Fig. 4 A). If proteolytic activation of a given substrate is required for fusion, we expected the loss of that substrate to phenocopy the loss of Kex2; it should display a mild decrease in fusion when crossed to a WT partner and a more severe decrease when crossed to a Δprm1 partner. As shown in Fig. 4 A, none of the mutants displayed such a fusion defect. Thus, the Δkex2 fusion defect does not result from the inactivation of any one of these substrates singly.

Figure 4.

Deletion of known Kex2 substrates fails to enhance the Δprm1 fusion defect in trans. (A) MATa strains bearing deletions of genes for known Kex2 substrates were crossed to WT or Δprm1 MATα strains. After filter mating and fixation, 100 mating pairs per experiment were scored for cytoplasmic mixing; data shown are derived from three independent experiments. (B) Kex2-dependent mobility shift of Ykl077w and Prm2 was assayed by Western blotting. Protein was prepared from whole cell lysates of vegetatively growing cultures (Ykl077w-HA strains) or α-factor–induced cultures (Prm2-HA strains; 10 μg/ml α-factor for 30 min). A likely degradation product of Ykl077w-HA (asterisk) is independent of Kex2.

Some of these Kex2 substrates may act redundantly and only show a phenotype when removed in combination. For example, it has been shown that the lack of Scw4 or Scw10 alone causes a very mild cell wall defect, but the loss of both results in extreme weakening of the cell wall and a mating defect (Cappellaro et al., 1998). We tested the Δscw4 Δscw10 double mutant in our fusion assays and saw no effect with a WT or Δprm1 mating partner (Fig. 4 A) or with a Δscw4 Δscw10 mating partner (unpublished data). It remains possible that inactivation of some other combination of known Kex2 substrates would recapitulate the Δkex2 fusion defect.

We hypothesized that there might be an additional, unidentified Kex2 substrate that mediates Kex2-dependent fusion. We designed a bioinformatics screen to attempt to identify such a substrate. In brief, we developed a scoring matrix based on the cleavage site sequences of known substrates and used it to rank potential cleavage sites in all other Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteins, discarding high-scoring candidate sites that are not conserved among closely related yeasts or that are predicted to be cytoplasmic (Table S1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200609182/DC1). We tested 11 proteins with the highest ranked candidate sites by generating epitope-tagged alleles of each in WT and Δkex2 backgrounds and performing SDS-PAGE and Western blotting of cell lysates. With this approach, we identified two new Kex2 substrates, Prm2 and Ykl077w (Fig. 4 B).

Prm2 is predicted to be a pheromone-regulated multispanning membrane protein with a topology similar to Prm1 and was identified in the bioinformatics screen that led to the characterization of Prm1 (Heiman and Walter, 2000). Ykl077w is an uncharacterized protein predicted to have a large (∼300 amino acid) extracellular/lumenal domain and a single transmembrane segment. Both proteins showed a shift in apparent molecular weight in a Δkex2 mutant background that is consistent with Kex2-dependent proteolysis (Fig. 4 B).

We generated Δprm2 and Δykl077w mutants and tested them in our fusion assays. Neither mutant showed a defect with WT or Δprm1 mating partners (Fig. 4 A). Thus, although we were able to identify two novel Kex2 substrates, neither appears to be the hypothetical substrate relevant to fusion. It may be that another, currently unidentified substrate or a combination of redundant Kex2 substrates acts during cell fusion.

Δkex2 shares a spectrum of phenotypes with other cell wall mutants but uniquely enhances the Δprm1 cell fusion defect

We asked whether the sum of physiological effects resulting from a lack of processing of Kex2 substrates might explain the Δkex2 fusion defect. For example, cells lacking Kex2 display a weakened cell wall phenotype, as assayed by the up-regulation of cell integrity pathway target genes and hypersensitivity to the cell wall–binding dye Congo red (Tomishige et al., 2003). Cell wall stress is known to induce the PKC signaling pathway, which can inhibit cell fusion (Philips and Herskowitz, 1997). Thus we next asked whether cell wall stress could explain the cell fusion defect caused by the loss of Kex2.

To this end, we first established whether the PKC cell integrity pathway is activated in Δkex2, Δkex1, and Δprm1 mutant cells. Cell wall stress and low osmolarity signals activate Pkc1 through the Bck1 MAPK module, eventually leading to activation of the transcription factor Rlm1, which activates the transcription of many genes, including MPK1 (Banuett, 1998). Thus, an MPK1-lacZ reporter gene has been used to detect activation of the PKC cell integrity pathway (Jung and Levin, 1999; Muller et al., 2003). We grew strains bearing the MPK1-lacZ reporter overnight with or without the addition of 1 M sorbitol as osmotic support, harvested cultures in exponential phase, and assayed for reporter activity during vegetative growth or after exposure to α-factor pheromone (Fig. 5 A).

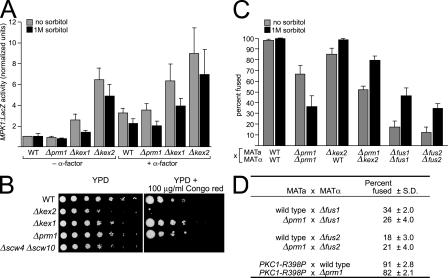

Figure 5.

Δkex1 and Δkex2 mutants exhibit cell wall phenotypes similar to other mutants but are unique in synergizing with Δprm1. (A) To assay activation of the cell integrity pathway, WT, Δprm1, Δkex1, and Δkex2 strains bearing an MPK1-lacZ reporter were grown to log phase without pheromone (– α-factor) or were treated with 10 μg/ml α-factor (+ α-factor) for 2 h, and β-galactosidase activity was quantified. Values were normalized to that of uninduced WT. (B) Cells were grown to OD 1.0 and spotted onto YPD plates with or without 100 μg/ml Congo red in 1:5 serial dilutions and were cultured for 2 d at 30°C. (C) Indicated crosses were performed by filtering mating mixtures onto nitrocellulose filters and incubating for 3 h on YPD or YPD supplemented with 1 M sorbitol. (A and C) Bars represent the mean ± SD (error bars) of three experiments. (D) Strains bearing deletions of FUS1 or FUS2 or expressing an activated allele of PKC1 (PKC1-R398P) were mated to a Δprm1 partner for 3 h and assayed for cytoplasmic mixing.

WT cells show enhanced MPK1 activation upon α-factor treatment, as expected from the cell wall remodeling that accompanies the pheromone response. The presence of osmotic support slightly decreased MPK1 activation in WT cells (Fig. 5 A, black bars). Note that Δprm1 mutant cells were indistinguishable from WT in the absence and presence of α-factor, strongly suggesting that the deletion of PRM1 does not affect cell wall structure (Fig. 5 A). In contrast, Δkex1 and Δkex2 mutants showed enhanced baseline MPK1 activation (2.5- and 6-fold greater than WT levels, respectively), which is consistent with a cell wall structural defect. The enhanced MPK1 activation was exacerbated by pheromone treatment and weakly mitigated by the presence of osmotic support (Fig. 5 A). Δste13 mutants did not show these effects (unpublished data).

As a further measure of cell wall integrity, we assayed each mutant for Congo red sensitivity. Mutants with compromised cell walls generally do not grow on media containing Congo red. Consistent with previously reported results, Δkex2 growth was severely inhibited on plates containing 100 μg/ml Congo red (Fig. 5 B; Tomishige et al., 2003), which is similar to the phenotype of the Kex2 substrate mutant Δscw4 Δscw10 (Fig. 5 B; Cappellaro et al., 1998). In contrast, the viability of neither Δkex1 nor Δprm1 was affected by Congo red. Thus, as assayed by MPK1 activation and Congo red sensitivity, cell wall defects are severe in Δkex2 mutant cells, mild in Δkex1 mutant cells, and undetectable in Δprm1 mutant cells.

Most cell wall defects manifest themselves as a result of a failure of the cell wall to provide a rigid support counteracting the outward force on the cell membrane caused by the osmotic imbalance between cytoplasm and the growth medium. Thus, we next asked whether osmotically stabilized medium (i.e., growth medium formulated at an osmolarity closer to that of cytoplasm), which relieves many phenotypes resulting from cell wall defects, could suppress the Δkex2 cell fusion defect. Mating reactions were performed under standard conditions with or without 1 M sorbitol, and fused mating pairs were counted in the quantitative cell fusion assay. As controls, we showed that bilateral crosses of the classical cell wall remodeling mutants Δfus1 and Δfus2 were partially suppressed by mating on osmotic support (Fig. 5 C). Surprisingly, we found that Δprm1 cells displayed a decreased fusion efficiency in the presence of osmotic support (Fig. 5 C; a similar observation was reported by Jin et al. [2004]). The explanation for this decrease is not clear, but it suggests that the Δprm1 defect is distinct from cell wall stress. In contrast, the mild Δkex2 × WT defect was suppressed by osmotic support (Fig. 5 C), as was the Δkex1 × WT defect (not depicted). The strongly deficient Δkex2 × Δprm1 mating was partially suppressed, but, importantly, fusion was not restored to WT levels. Thus, Δkex2 and Δkex1 behave similarly to other fusion mutants known to affect cell wall degradation, whereas Δprm1 does not.

If cell wall defects caused by the loss of Kex2 are responsible for strongly enhancing the Δprm1 fusion defect, we expect other mutants with similar cell wall defects also to synergize with Δprm1 in a fusion assay; alternatively, if the failure to process Kex2 substrates that act specifically with Prm1 causes the enhanced fusion defect, other cell wall mutants will not synergize with Δprm1. To distinguish these possibilities, we mated strains bearing a Δfus1, Δfus2, or PKC1-R398P (a gain of function allele that mimics constitutive cell wall stress; Nonaka et al., 1995) mutation to a Δprm1 partner and scored mating pairs with the cell fusion assay. Unlike Δkex2 × Δprm1, no combination of mutants in these mating reactions showed a synergistic defect (Fig. 5 D). Mating reactions with the cell wall structure mutant Δscw4 Δscw10 × Δprm1 (Fig. 4 B) similarly did not produce a synergistic defect. Thus, collectively, Δkex2 mutant cells experience cell wall stress and concomitantly increase MPK1 activation. However, those defects are not sufficient to explain the unique synergy we observe between Δkex2 and Δprm1 mating partners. Therefore, these results strongly suggest that the synergistic effect of the Δkex2 and Δprm1 mutations on cell fusion results from combined defects in the cell fusion machinery.

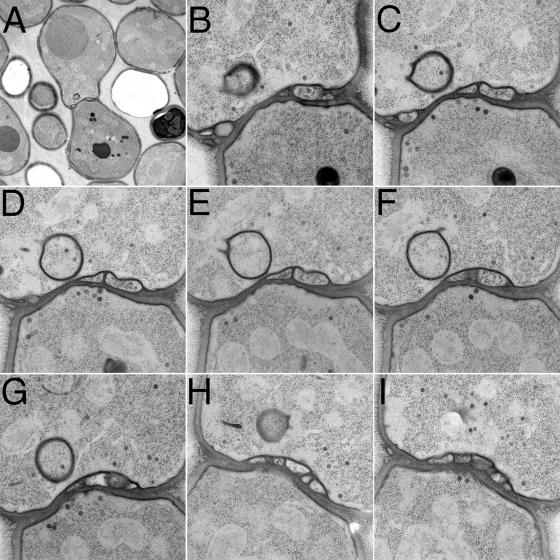

Δkex2 mutants produce cytoplasmic blebs embedded in the cell wall

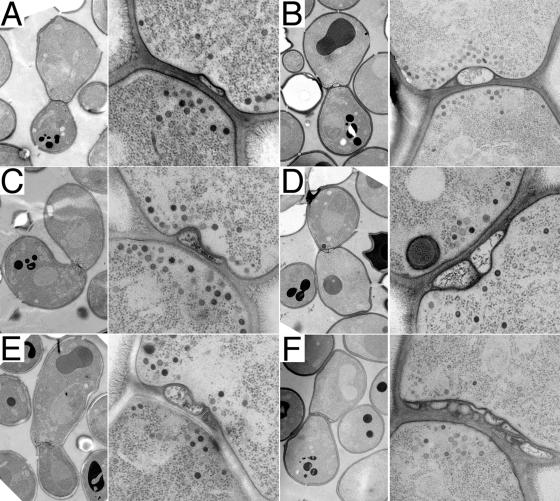

To characterize ultrastructurally the cell fusion intermediate at which Δkex2 × WT mating reactions arrest, we examined fusion-arrested mating pairs using electron microscopy. In the majority (80%) of unfused Δkex2 × WT mating pairs, we observed novel bleblike structures in the cell wall separating the two mating partners. Such cell wall–embedded blebs appear disconnected from both cells (Figs. 6 and 7). The blebs are bounded by a visible lipid bilayer (Figs. 6 E and 7, F and M; in other views, the bilayer is harder to discern because of the angle of the section relative to the plane of the bilayer). A gap of a relatively consistent width of ∼8 nm separates the blebs from the plasma membrane that they appear adhered to (Figs. 6, A, C, and E; and 7, F, J, and M). About 90% of the blebs appear preferentially linked to one mating partner, but ∼10% of the blebs closely approach the plasma membrane of the other mating partner as well (Figs. 6, B and C; and 7, F and M). In any given section, we observed numbers ranging from one bleb (Fig. 6, A and C) to one primary bleb with others clearly above or below it (Fig. 6, B and E), to two blebs side by side with their surfaces tightly apposed (Fig. 6 D), to a cascade of blebs spread out across the diameter of the cell–cell interface (Fig. 6 F). About 75% of unfused mating pairs have one to five blebs, with 5% having more and 20% having none. In serial sections, we never detected a clear cytoplasmic continuity between a bleb and either mating partner. The texture of the staining inside the blebs often appears fibrous, unlike the regular punctate staining of ribosomes observed in normal cytoplasm (Fig. 6 D).

Figure 6.

Δkex2 × WT mating pairs fail to fuse and develop cell wall–embedded blebs. Mating mixes of Δkex2 × WT partners were prepared on filters as described in Materials and methods and were incubated for ∼3 h at ambient temperature. The cells were then subjected to high-pressure freezing and were fixed, stained, and imaged by transmission electron microscopy. Two different magnifications are shown for each image. (A–F) Mating pairs showing one, two, or more blebs trapped within the cell wall near the center of the cell–cell interface.

Figure 7.

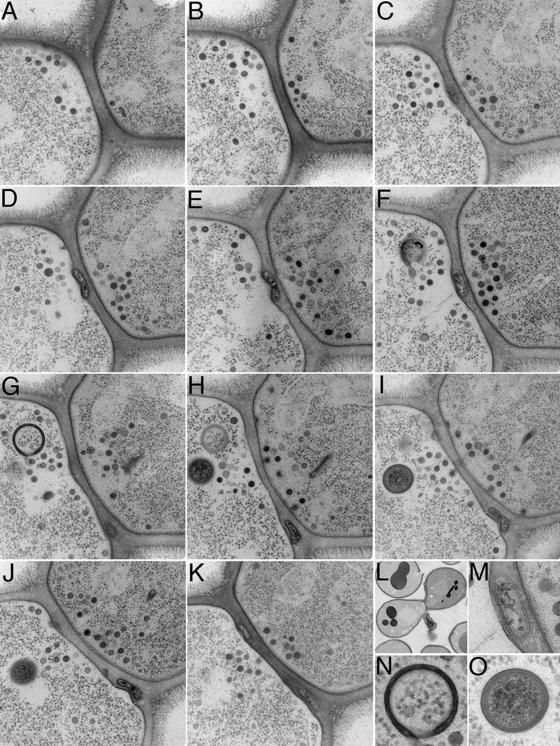

Serial section analysis of a Δkex2 × WT mating pair. (A–K) Transmission electron micrographs of serial sections through the cell–cell interface of a Δkex2 × WT mating pair prepared as in Fig. 6. (L) Low magnification view of the mating pair. (M) High magnification view of the bleb seen in F. (N) High magnification view of an intracellular structure from G. (O) High magnification view of an intracellular structure from I.

We examined the 3D structure and arrangement of blebs in more detail by serial section analysis. A representative set of serial sections is shown in Fig. 7. At one end of the series, the cell–cell interface appears restricted, and secretory vesicles are sparse, indicating the sections come from a region where the cells are just beginning to make contact off center of the long axis of the mating pair (Fig. 7, A and B). As the sections approach the center of the mating pair, the contact zone widens, the number of secretory vesicles in the cytoplasm increases, and a cell wall–embedded bleb appears (Fig. 7, C and D). Moving more to the center of the cell–cell interface, the bleb broadens and appears to push slightly into the mating partner on the left (Fig. 7, E and F) before disappearing from view (Fig. 7 G). A second bleb appears in a lower section and widens (Fig. 7, G–K); a third and possibly a fourth bleb appear still farther along the stack of sections (Fig. 7, J and K). The bleb in Fig. 7 (C–F) almost contacts both plasma membranes; in Fig. 7 F (magnified in Fig. 7 M), it appears only ∼10 nm from the partner on the right.

Other structures of unknown function are also frequently observed in these images. A dark, unclosed circle reminiscent of the formation of autophagic structures by the fusion of small vesicles (Kim and Klionsky, 2000) appears to begin enclosing a region of cytoplasm (Fig. 7 G; magnified in N). Similarly, a spherical lipid bilayer enclosed in a second, equidistant bilayer contains dark-staining cytoplasm (Fig. 7 I; magnified in O) and suggests a mature form of the first structure. Both structures are surrounded by a zone of ribosome exclusion. Similar structures appear often in sections of Δkex2 mutant–derived mating pairs (Fig. 6 D).

Δprm1 Δkex2 × Δprm1 mating pairs exhibit blebs, bubbles, and enormous barren bubbles

We have previously described the formation of bubbles as characteristic features of fusion-arrested Δprm1 × Δprm1 mating pairs (Heiman and Walter, 2000). Bubble formation appeared to result from a block in fusion of the mating partners after the intervening cell wall had been removed and plasma membranes had tightly adhered to each other, often buckling as a double membrane into either cell. Based on the morphologically distinguishable phenotypes of the Δkex2 × WT and Δprm1 × Δprm1–derived mating pairs, we wished to explore whether the ultrastructure of Δprm1 Δkex2 × Δprm1 mating pairs would reflect the order of KEX2 and PRM1 function in the fusion pathway. Rather than observing a single epistatic phenotype, however, we saw a more complex heterogeneous mixture of three classes of structures.

First, we observed bubbles in Δprm1 Δkex2 × Δprm1 mating pairs similar to those seen in Δprm1 × Δprm1 mating reactions. A characteristic bubble in such mating pairs is shown in Fig. 8 (A and B). In this example, the mating partner on the bottom forms an extension past the midline of the mating pair and well into the space previously occupied by the mating partner on the top. The plasma membranes appear tightly apposed but unfused. The cytoplasmic continuity between the bubble and the bottom cell is obvious, and the texture of the staining within the bubble matches that of normal cytoplasm.

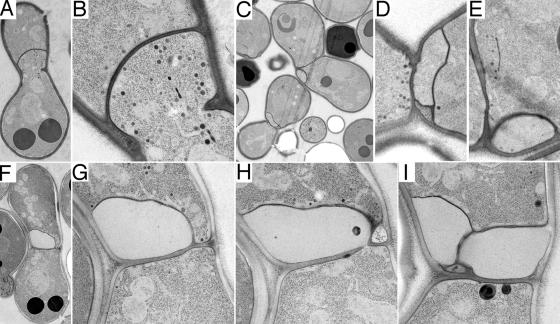

Figure 8.

Δprm1Δkex2 × Δprm1 mating pairs fail to fuse and develop a variety of structures. Mating mixes were prepared as in Fig. 6. (A and B) A mating pair in low and high magnification views with a region of cytoplasm extending across the midline from one partner to the other. (C–E) Two mating pairs in low and high magnification views containing membrane-bounded inclusions with staining textures consistent with that of cytoplasm. (F–I) A mating pair in low magnification view and three serial sections in high magnification view with a membrane-bounded structure that extends across the midline from one partner to the other and that has a staining texture different from the cytoplasm.

Second, we observed cell wall–embedded blebs similar to Δkex2 × WT mating reactions. Serial sections of a Δprm1 Δkex2 × Δprm1 bleb are shown in Fig. 9. Several blebs extend over the full width of the cell–cell interface. No cytoplasmic continuity between the blebs and either mating partner can be found. Additionally, a double bilayer-bound structure appears in the upper mating partner of this pair. In some mating pairs, blebs of an enormous size accumulated (both mating pairs in Fig. 8 C; magnified in D and E).

Figure 9.

Serial section analysis of a Δprm1Δkex2 × Δprm1 mating pair. (A) Low magnification transmission electron micrograph of a Δprm1 Δkex2 × Δprm1 mating pair prepared as in Fig. 6. (B–F) High magnification serial sections across the cell–cell interface of the mating pair shown in A.

Third, some Δprm1 Δkex2 × Δprm1 mating pairs display a unique morphology that was not previously observed, which is referred to here as enormous barren bubbles. Enormous barren bubbles appear similar to Δprm1 × Δprm1 bubbles but are essentially devoid of the staining of ribosomes and vesicles that populate normal cytoplasm (serial sections; Fig. 8, F–I). These structures also lack the fibrous pattern typical of Δkex2 blebs. Instead, they present the appearance of empty, organelle-free cytoplasm despite the presence of clear continuities to one mating partner (Fig. 8 H). One section shows an enormous barren bubble that may be folded back onto itself, thus giving the appearance of two separate structures (Fig. 8 I). The lack of cytosol might reflect a lysis event, which a fraction of Δprm1 mating pairs undergo (Jin et al., 2004). Similarly, barren areas have been observed in ultrastructural studies of myoblast fusion pores and within membrane sacs subsequent to cell–cell fusion (see Fig. 2 in Doberstein et al., 1997). It remains an intriguing mystery how a portion of the cytoplasm could become so distinctly different without a visibly delimiting barrier.

Discussion

The molecular machine that fuses cells during yeast mating has remained elusive. In this study, we describe the discovery of a role of Kex2 during cell fusion. To date, Kex2's only known function in mating involved an earlier step, namely the proteolytic processing of the pheromone α-factor in MATα cells (Rockwell et al., 2002). In contrast, Kex2 is not required in MATa cells for pheromone processing, which allowed the discovery of its role in cell fusion. This duality mirrors the Axl1 protease, which processes a-factor pheromone in MATa cells and is required in MATα cells for efficient fusion (Adames et al., 1995; Elia and Marsh, 1998). However, as Axl1 activity is cytoplasmic and Kex2 activity is lumenal/extracellular, it is unlikely that this curious parallel reflects a shared mechanism. MATa cells lacking the exopeptidase Kex1 display a cell fusion defect similar to that of cells lacking Kex2, strongly suggesting that it is the lumenal/extracellular proteolytic activities of Kex2 and Kex1 that are required in this process. Therefore, we propose that Kex2 and Kex1 proteolytically activate at least one (yet to be identified) substrate protein that comprises part of the fusion machinery. By analogy, furin, a Kex2 family protease, proteolytically activates the fusases of several viruses. Mechanistically, the postulated Kex2 substrate could form a complex with Prm1 and possibly other components to constitute the membrane fusion machine. Alternatively, the Kex2 substrate and Prm1 could act at distinct yet mechanistically coupled sites in the membrane to promote fusion.

Genetic analysis of KEX2 and PRM1 shows a synergistic interaction between these genes. To achieve efficient cell fusion, at least one mating partner must carry active KEX2 and PRM1. Cell fusion suffers greatly in mating efficiency when both mating partners lack one or both of the two genes (Δprm1 × Δprm1, Δkex2 × Δprm1, and Δprm1 Δkex2 × Δprm1), whereas only mild defects are observed whenever one mating partner is WT (WT × WT, Δprm1 × WT, WT × Δprm1, Δkex2 × WT, and Δkex2 Δprm1 × WT). Thus, a simple model emerges from the genetic data: (1) Prm1 and Kex2 (the latter likely acting by proxy through a substrate) are both important for the same step in cell fusion, and (2) this step can be performed by either mating partner. This model also accounts for the finding that Δprm1 and Δkex2 mutations synergize in trans but not in cis.

Therefore, this definition of KEX2's role in cell fusion illuminates another layer of genetic redundancy in the process. Originally, PRM1 eluded detection in traditional screens because a Δprm1 mutant only displays a cell fusion phenotype when mated to a partner also lacking PRM1. A Δkex2 mutant likewise displays a strong cell fusion phenotype only when mated to a Δprm1 partner. Consequently, kex2 mutants would be isolated for their cell fusion phenotype only in a sensitized screen, such as the one described here. This strategy can now be extended to identify other genes in the pathway, including, but by no means limited to, the postulated and eagerly sought-after Kex2 substrate.

Although the Kex2 substrate relevant to cell fusion remains unknown, one especially interesting candidate is Prm2. Prm2, a protein of unknown function, is topologically similar to Prm1, is expressed only during mating, and is a Kex2 substrate. However, the deletion of Prm2 causes no fusion defect. It is possible that Prm2 acts redundantly with another Kex2 substrate or that the deletion of Prm2 fails to mimic the presence of unprocessed Prm2. On the other hand, it also remains possible that Kex2 acts indirectly during fusion (for example, through general effects on the stability of the cell wall). Consistent with this hypothesis, the magnitude of the Δkex2 fusion defect is reduced by osmotic support. However, other mutants that affect cell wall integrity (Δscw4 Δscw10), cell wall remodeling (Δfus1 and Δfus2), or hyperactivate the cell wall stress pathway (PKC1-R398P) do not synergize with Δprm1, arguing that the Δkex2 defect is uniquely linked to the Prm1-dependent step of membrane fusion. Likewise, the electron microscopy phenotype of unfused zygotes resulting from matings of Δkex2 MATa cells suggests a specific and novel defect resulting from attempted fusion.

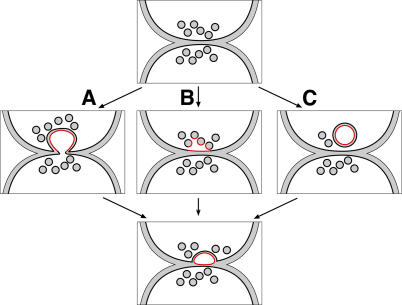

Although it is unlikely that the morphological features observed in arrested mating pairs reflect bona fide intermediates in the fusion pathway, the morphological consequences of blocking the fusion reaction are nevertheless intriguing. Rather than arresting at the same end point as one might naively expect, Δkex2 and Δprm1 mating pairs show unique morphologies at the electron microscope level. However, in many respects, the blebs observed here resemble bubbles seen previously in Δprm1 × Δprm1 matings, which is consistent with the notion that KEX2 and PRM1 act at similar steps. Like bubbles, blebs are membrane-bounded structures that are often found apposed to a nearby plasma membrane separated by a regular gap of ∼8 nm, and both bubbles and blebs appear to push into the space occupied by one mating partner. In contrast to bubbles, however, blebs are extracellular entities that show no continuity to either parent cell. This difference shows that the loss of Prm1 and the loss of Kex2 are not equivalent. If both Prm1 and the postulated Kex2 substrate are components of a single fusion machine, which becomes partially inactivated when either component is compromised, the residual machines in the respective mutant cells preferentially stall in the pathway at different points, thus leading to the characteristic and distinct morphological phenotypes. Consistent with this notion, stalling can occur at either end point when both Prm1 and Kex2 are missing in mating cells. Unfortunately, the effects of KEX2 disruption can currently only be observed in MATa cells because of the requirement for the Kex2 processing of α-factor.

One possible mechanism for the formation of blebs is that a Δprm1-like bubble forms first but then becomes severed from the partner that forms it (Fig. 10 A); an intermediate suggesting this state is seen in mutants deficient in the a-factor transporter Ste6 (Elia and Marsh, 1996). Alternatively, the delivery of exocytic vesicles may be misregulated, thus producing the blebs (Fig. 10 B), or blebs could derive from the unusual circular structures observed (Fig. 10 C). According to both of these latter possibilities, Δkex2 blebs would not be derived from Δprm1 bubbles because in either case, the membrane surrounding the bleb would come from the same cell that provides the apposing plasma membrane. Precedence for the mechanism shown in Fig. 10 B comes from our knowledge of the sperm acrosome reaction. In this system, a repository of fusogenic material is delivered to the sperm surface in a burst of exocytosis. As part of this process, membrane-bounded cytoplasmic fragments are excised from the sperm as a result of rapid exocytosis at many points along the plasma membrane (Talbot et al., 2003). To distinguish between these models, it will be helpful to determine in future studies from which of the two parental cells the blebs originate.

Figure 10.

Possible models for the mechanism of bleb formation. Three possibilities of how defective attempts at cell fusion could produce cell wall–embedded blebs at the cell–cell interface. (A) A cytoplasmic extension reaches across the midline and is severed. (B) Extensive fusion of vesicles to each other and to the plasma membrane excises a pocket of cytoplasm. (C) An intracellular inclusion forms and is delivered to the surface.

Materials and methods

Yeast strains, plasmids, and growth media

Strains used in this study are listed in Table I. Gene replacements were generated with the PCR transformation technique (Longtine et al., 1998). Strains MHY398 and MHY427 were derived from KRY18 (a gift from R. Fuller, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI; Komano and Fuller, 1995). The plasmid pDN291 was used to express soluble cytosolic GFP and contains the URA3 gene as previously described (Ng and Walter, 1996). The plasmid pRS314 is a standard vector containing the TRP1 gene and was used in conjunction with pDN291 to create a set of mating type–specific selectable markers (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989). The plasmid pJP67 is used to express the hyperactive allele PKC1(R398P) (Nonaka et al., 1995; Philips and Herskowitz, 1997). Congo red plates were prepared as previously described (Tomishige et al., 2003) by adding a 20-mg/ml stock solution of Congo red to <70°C autoclaved YPD (yeast extract/peptone/glucose) agar to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. The MPK1-lacZ plasmid was a gift from K. Cunningham (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD).

Table I.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| MHY425 | MATa, his3- Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| MHY189 | MATα, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pDN291 |

| MHY426 | MATa, Δprm1∷S. kluyveri HIS3 +, his3- Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| MHY191 | MATα, Δprm1∷S. kluyveri HIS3 +, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pDN291 |

| MHY398 | MATa, Δkex2∷TRP1, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre |

| MHY461 | MATa, Δkex1∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| MHY462 | MATa, Δste13∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| MHY427 | MATa, Δprm1∷S. kluyveri HIS3 +, Δkex2∷TRP1, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre |

| MHY445 | MATa, Δprm1∷S. kluyveri HIS3 +, Δkex1∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| MHY447 | MATa, Δprm1∷S. kluyveri HIS3 +, Δste13∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochr e, pRS314 |

| MHY189 | MATα, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pDN291 |

| MHY387 | MATa, Δscw4∷S. kluyveri HIS3 +, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| MHY388 | MATα, Δscw10∷S. kluyveri HIS3 +, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pDN291 |

| MHY389 | MATa, Δscw4∷S. kluyveri HIS3 +, Δscw10∷S.kluyveri HIS3 +, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| MHY390 | MATα, Δscw10∷S. kluyveri HIS3 +, Δscw10∷S.kluyveri HIS3 +, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pDN291 |

| AEY142 | MATa, Δpir3∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre |

| AEY143 | MATa, Δhsp150∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| AEY144 | MATa, Δsun4∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| AEY145 | MATa, Δccw11∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| AEY146 | MATa, Δexg1∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre |

| AEY147 | MATa, Δscw11∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| AEY148 | MATa, Δpir1∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| AEY14 | MATa, Δykl077w∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| MHY524 | MATa, Δprm2∷S. kluyveri HIS3 + , his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2101ochre, pRS314 |

| AEY7 | MATa, YKL077W-HA∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| AEY8 | MATa, YKL077W-HA∷kanR, Δkex2∷TRP1, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| MHY546 | MATa, PRM2-HA∷S. kluyveri HIS3 + , his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2101ochre, pRS316 |

| MHY548 | MATa, PRM2-HA: S. kluyveri HIS3 + , Δkex2∷TRP1, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2101ochre, pRS316 |

| AEY67 | MATa, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pMPK1-LacZ∷URA3 |

| AEY69 | MATa, Δkex2∷TRP1, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pMPK1-LacZ∷URA3 |

| AEY71 | MATa, Δkex1∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pMPK1-LacZ∷URA3 |

| AEY72 | MATa, Δprm1:S. kluyveri HIS3 +, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pMPK1-LacZ∷URA3 |

| AEY92 | MATa, Δste13∷kanR, his3−Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pMPK1-LacZ∷URA3 |

| AEY1 | MATα, Δfus1∷kanR, his3- Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pDN291 |

| AEY17 | MATa, Δfus1∷kanR, his3- Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| AEY2 | MATα, Δfus2∷kanR, his3- Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pDN291 |

| AEY18 | MATa, Δfus2∷kanR, his3- Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pRS314 |

| AEY58 | MATa, his3- Δ200, ura3- Δ99, leu2- Δ1, trp1- Δ99, ade2-101ochre, pJP67 |

All strains were constructed in the W303 background.

Genetic screen for enhancers of Δprm1

Δprm1 TRP1 MATa cells were grown to log phase, and 4 A600U were washed once in a buffer of 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4 (10 ml; Sigma-Aldrich), and resuspended in the same solution. 300 μl of the mutagen ethyl methane sulfonate (Sigma-Aldrich) was added. Cells were vortexed and incubated for 30 min at 30°C. At that point, a 15-ml solution of 10% sodium thiosulfate (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to quench the reaction. Cells were washed twice in YPD medium and allowed to recover in YPD for 90 min at 30°C to fix any mutations that were induced. Serial dilutions of this stock were plated to medium lacking tryptophan, and the titer of colony-forming units was calculated; meanwhile, the stock was kept at 4°C. For screening, the stock was plated to 100 plates lacking tryptophan at a density of ∼120 colonies/plate. Colonies were allowed to grow for 40 h at 30°C. After ∼25 h, a stationary overnight culture of Δprm1 URA3 MATα was plated to 100 plates of YPD at 100 μl/plate and was incubated at room temperature for the remaining 15 h to form lawns. These lawns were respread with 100 μl/plate of water to a dull matte appearance indicative of homogeneity. Colonies of the mutagenized MATa cells were replica plated to mating lawns and incubated for 8 h at 30°C. The plates were then replica plated to medium lacking tryptophan and uracil to select for diploids. Phenotypes were scored on plates incubated for 2 d at 30°C. The clarity of the phenotypes critically depended on having homogeneous lawns of the proper density.

Complementation of the Δprm1 enhancer mutation

MATα-specific sterility appeared in several of the enhancer mutants. We aimed for complementation of this phenotype because it was easier to score. After backcross to a Δprm1 strain, the sterile Δprm1 MATα was transformed with a pRS316-based library (a gift from S. O'Rourke, University of Oregon Institute of Molecular Biology, Eugene, OR; O'Rourke and Herskowitz, 2002). 15,000 transformants were subjected to a replica mating assay as described in Fig. 1 A with a tester strain as partner.

Quantitative assay of cell fusion

The cell fusion assay was performed as described previously (Philips and Herskowitz, 1997). Cells of opposite mating types with the MATα strain expressing soluble cytosolic GFP were grown overnight to log phase, and 1 A600U of each were mixed and vacuumed to a nitrocellulose filter. The filter was placed cell-side up on a YPD plate, and the plate was incubated for 3 h at 30°C. Cells were then scraped off the filter, fixed in 4% PFA, and incubated at 4°C overnight. This mixture was then spotted on a slide and observed with a fluorescent microscope (Axiovert 200M; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) using a 63× plan-Apochromat oil-immersion objective (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.). First, a field was selected randomly using transmission optics. Then, groups of zygotes and mating pairs within that field were identified by brightfield microscopy and were subsequently scored as fused zygotes or unfused mating pairs by switching between brightfield and fluorescence. This procedure was continued until all the zygotes and mating pairs in the field were scored, at which point a new field was chosen and the procedure was repeated. To capture images, a single optical section was taken by both brightfield and fluorescence microscopy using a confocal microscope (TCS NT; Leica) with a 100× oil-immersion objective (Leica), a 150-mW, 488-nm argon excitation laser (Uniphase), and a 510–550-nm band-pass emission filter to visualize GFP. These images were then superimposed and contrast enhanced.

β-Galactosidase assays

Yeast strains containing the MPK1-lacZ reporter were grown to log phase in SC-URA with or without 1 M sorbitol. For pheromone induction, log-phase cultures were incubated with 10 μg/ml α-factor for 2 h. Reporter activity was quantified as previously described (Papa et al., 2003) using 0.8 mg/ml o-nitrophenol β-d-galactoside (Sigma-Aldrich). Reactions were incubated at 32°C for 10 min and stopped by adding an equal volume of 1 M NaCO3.

Bioinformatic search for novel Kex2 substrates

A scoring matrix to predict Kex2 cleavage sites was generated based on previously reported Kex2 substrates (Kex2 [Rockwell et al., 2002]; Mfα1 and Mfα2 [Kurjan and Herskowitz, 1982; Singh et al., 1983]; Ccw6/Pir1 and Ccw7/Hsp150 [Russo et al., 1992]; Ccw8/Pir2, Ccw11, Scw3/Sun4, and Scw4 [Cappellaro et al., 1998]; Scw6/Exg1 [Basco et al., 1990]; and Scw10, Scw11, and killer toxin [Bostian et al., 1984; Zhu et al., 1992]). The scoring matrix consisted of 10 protein sequence positions centered on the cleavage site, with the score for each residue at each position reflecting its prevalence among the known substrates at that position (Table S1). To obtain an overall score for a candidate sequence, the scores at each position were multiplied. For comparison purposes, we took the negative natural log of this value. Using a perl script, we searched the yeast genome for high-scoring potential cleavage sites. From the list of proteins that contained high-scoring sites, we discarded those that did not have a predicted transmembrane domain or signal sequence. Finally, candidates were selected that had high-scoring sites and in which the P2 and P1 positions were conserved among fungal homologues.

Electron microscopy

Mating reactions were performed identically to the method described for quantitative fusion assays but at room temperature. During the mating, plates were taken to the University of California, Berkeley, electron microscopy labaratory and subjected to high-pressure freezing after ∼3 h of total incubation (McDonald, 1999; McDonald and Müller-Reichert, 2002). Samples were fixed, stained, and embedded (McDonald, 1999). High-pressure freezing was found to yield superior contrast between membranes and surrounding areas and a smoother curvature to membranes than we had observed by conventional fixation (Heiman and Walter, 2000; McDonald and Müller-Reichert, 2002). Sections of ∼60-nm thickness were cut, poststained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate (Ted Pella Inc.), and imaged with an electron microscope (Tecnai-F20; Philips) equipped with a 200-kV LaB6 cathode and a bottom-mounted four-quadrant 16 million–pixel CCD camera (UltraScan 4000; Gatan).

Online supplemental material

The scoring matrix used in the bioinformatic screen for potential Kex2 substrates is available as Table S1. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200609182/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kyle Cunningham, Robert Fuller, Ira Herskowitz, and Sean O'Rourke for reagents. We thank Mei-Lie Wong for assistance with electron microscopy and Kent McDonald for expert preparation of high-pressure frozen samples. We also thank Pablo Aguilar, Hannah Cohen, Muluye Liku, Carolyn Ott, Claudia Rubio, and members of the Walter laboratory for helpful discussions. We dedicate this paper to the memory of our friend, colleague, and mentor Ira Herskowitz.

M.G. Heiman was a predoctoral fellow of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), and P. Walter is an HHMI investigator.

Note added in proof. Fig1 has recently been shown to act at a step similar to Prm1, after cell wall degradation but before membrane fusion (Aguilar, P.S., A. Engel, and P. Walter. 2006. Mol. Biol. Cell. doi:10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0776).

M.G. Heiman's present address is The Rockefeller University, New York, NY 10021.

Abbreviations used in this paper: PRM, pheromone-regulated membrane protein; WT, wild type.

References

- Adames, N., K. Blundell, M.N. Ashby, and C. Boone. 1995. Role of yeast insulin-degrading enzyme homologs in propheromone processing and bud site selection. Science. 270:464–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banuett, F. 1998. Signalling in the yeasts: an informational cascade with links to the filamentous fungi. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:249–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basco, R.D., G. Gimenez-Gallego, and G. Larriba. 1990. Processing of yeast exoglucanase (beta-glucosidase) in a KEX2-dependent manner. FEBS Lett. 268:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blobel, C.P., T.G. Wolfsberg, C.W. Turck, D.G. Myles, P. Primakoff, and J.M. White. 1992. A potential fusion peptide and an integrin ligand domain in a protein active in sperm-egg fusion. Nature. 356:248–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostian, K.A., Q. Elliott, H. Bussey, V. Burn, A. Smith, and D.J. Tipper. 1984. Sequence of the preprotoxin dsRNA gene of type I killer yeast: multiple processing events produce a two-component toxin. Cell. 36:741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brizzio, V., A.E. Gammie, and M.D. Rose. 1998. Rvs161p interacts with Fus2p to promote cell fusion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 141:567–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappellaro, C., V. Mrsa, and W. Tanner. 1998. New potential cell wall glucanases of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their involvement in mating. J. Bacteriol. 180:5030–5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, C., D.O. Bunch, J.E. Faure, E.H. Goulding, E.M. Eddy, P. Primakoff, and D.G. Myles. 1998. Fertilization defects in sperm from mice lacking fertilin beta. Science. 281:1857–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, C., H. Ge, D. Branciforte, P. Primakoff, and D.G. Myles. 2000. Analysis of mouse fertilin in wild-type and fertilin beta(−/−) sperm: evidence for C-terminal modification, alpha/beta dimerization, and lack of essential role of fertilin alpha in sperm-egg fusion. Dev. Biol. 222:289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuasnicu, P.S., D.A. Ellerman, D.J. Cohen, D. Busso, M.M. Morgenfeld, and V.G. Da Ros. 2001. Molecular mechanisms involved in mammalian gamete fusion. Arch. Med. Res. 32:614–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Campo, J.J., E. Opoku-Serebuoh, A.B. Isaacson, V.L. Scranton, M. Tucker, M. Han, and W.A. Mohler. 2005. Fusogenic activity of EFF-1 is regulated via dynamic localization in fusing somatic cells of C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 15:413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doberstein, S.K., R.D. Fetter, A.Y. Mehta, and C.S. Goodman. 1997. Genetic analysis of myoblast fusion: blown fuse is required for progression beyond the prefusion complex. J. Cell Biol. 136:1249–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworak, H.A., and H. Sink. 2002. Myoblast fusion in Drosophila. Bioessays. 24:591–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elia, L., and L. Marsh. 1996. Role of the ABC transporter Ste6 in cell fusion during yeast conjugation. J. Cell Biol. 135:741–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elia, L., and L. Marsh. 1998. A role for a protease in morphogenic responses during yeast cell fusion. J. Cell Biol. 142:1473–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, R.S., A. Brake, and J. Thorner. 1989. Yeast prohormone processing enzyme (KEX2 gene product) is a Ca2+-dependent serine protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 86:1434–1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, X., H. Sterling, Y. Chen, C. Saginario, E.J. Brown, W.A. Frazier, F.P. Lindberg, and A. Vignery. 2000. CD47, a ligand for the macrophage fusion receptor, participates in macrophage multinucleation. J. Biol. Chem. 275:37984–37992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbury, P.A. 1998. Springs and zippers: coiled coils in SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Structure. 6:1487–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiman, M.G., and P. Walter. 2000. Prm1p, a pheromone-regulated multispanning membrane protein, facilitates plasma membrane fusion during yeast mating. J. Cell Biol. 151:719–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, L.D., L.R. Hoffman, T.G. Wolfsberg, and J.M. White. 1996. Virus-cell and cell-cell fusion. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12:627–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskowitz, I. 1995. MAP kinase pathways in yeast: for mating and more. Cell. 80:187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughson, F.M. 1995. Structural characterization of viral fusion proteins. Curr. Biol. 5:265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H., C. Carlile, S. Nolan, and E. Grote. 2004. Prm1 prevents contact-dependent lysis of yeast mating pairs. Eukaryot. Cell. 3:1664–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julius, D., L. Blair, A. Brake, G. Sprague, and J. Thorner. 1983. Yeast alpha factor is processed from a larger precursor polypeptide: the essential role of a membrane-bound dipeptidyl aminopeptidase. Cell. 32:839–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, U.S., and D.E. Levin. 1999. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression regulated by the yeast cell wall integrity signalling pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 34:1049–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaji, K., S. Oda, T. Shikano, T. Ohnuki, Y. Uematsu, J. Sakagami, N. Tada, S. Miyazaki, and A. Kudo. 2000. The gamete fusion process is defective in eggs of Cd9-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 24:279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., and D.J. Klionsky. 2000. Autophagy, cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting pathway, and pexophagy in yeast and mammalian cells. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:303–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komano, H., and R.S. Fuller. 1995. Shared functions in vivo of a glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-linked aspartyl protease, Mkc7, and the proprotein processing protease Kex2 in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:10752–10756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara, L.J., C.T. Beh, M. Latterich, R. Schekman, and M.D. Rose. 1994. Nuclear congression and membrane fusion: two distinct events in the yeast karyogamy pathway. J. Cell Biol. 126:911–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurjan, J., and I. Herskowitz. 1982. Structure of a yeast pheromone gene (MF alpha): a putative alpha-factor precursor contains four tandem copies of mature alpha-factor. Cell. 30:933–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz, M.J., and R.B. Wickner. 1976. A chromosomal gene required for killer plasmid expression, mating, and spore maturation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 73:2061–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Naour, F., E. Rubinstein, C. Jasmin, M. Prenant, and C. Boucheix. 2000. Severely reduced female fertility in CD9-deficient mice. Science. 287:319–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M.S., A. McKenzie III, D.J. Demarini, N.G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J.R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 14:953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, K. 1999. High-pressure freezing for preservation of high resolution fine structure and antigenicity for immunolabeling. Methods Mol. Biol. 117:77–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, K., and T. Müller-Reichert. 2002. Cryomethods for thin section electron microscopy. Methods Enzymol. 351:96–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi, S., X. Lee, X. Li, G.M. Veldman, H. Finnerty, L. Racie, E. LaVallie, X.Y. Tang, P. Edouard, S. Howes, et al. 2000. Syncytin is a captive retroviral envelope protein involved in human placental morphogenesis. Nature. 403:785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyado, K., G. Yamada, S. Yamada, H. Hasuwa, Y. Nakamura, F. Ryu, K. Suzuki, K. Kosai, K. Inoue, A. Ogura, et al. 2000. Requirement of CD9 on the egg plasma membrane for fertilization. Science. 287:321–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler, W.A., G. Shemer, J.J. del Campo, C. Valansi, E. Opoku-Serebuoh, V. Scranton, N. Assaf, J.G. White, and B. Podbilewicz. 2002. The type I membrane protein EFF-1 is essential for developmental cell fusion. Dev. Cell. 2:355–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrsa, V., T. Seidl, M. Gentzsch, and W. Tanner. 1997. Specific labelling of cell wall proteins by biotinylation. Identification of four covalently linked O-mannosylated proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 13:1145–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, E.M., N.A. Mackin, S.E. Erdman, and K.W. Cunningham. 2003. Fig1p facilitates Ca2+ influx and cell fusion during mating of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 278:38461–38469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, D.T., and P. Walter. 1996. ER membrane protein complex required for nuclear fusion. J. Cell Biol. 132:499–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, S., A.E. Cowan, D.E. Koppel, H. Jin, and E. Grote. 2006. FUS1 regulates the opening and expansion of fusion pores between mating yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell. 17:2439–2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka, H., K. Tanaka, H. Hirano, T. Fujiwara, H. Kohno, M. Umikawa, A. Mino, and Y. Takai. 1995. A downstream target of RHO1 small GTP-binding protein is PKC1, a homolog of protein kinase C, which leads to activation of the MAP kinase cascade in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 14:5931–5938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Rourke, S.M., and I. Herskowitz. 2002. A third osmosensing branch in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires the Msb2 protein and functions in parallel with the Sho1 branch. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:4739–4749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa, F.R., C. Zhang, K. Shokat, and P. Walter. 2003. Bypassing a kinase activity with an ATP-competitive drug. Science. 302:1533–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips, J., and I. Herskowitz. 1997. Osmotic balance regulates cell fusion during mating in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 138:961–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips, J., and I. Herskowitz. 1998. Identification of Kel1p, a kelch domain-containing protein involved in cell fusion and morphology in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 143:375–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podbilewicz, B., E. Leikina, A. Sapir, C. Valansi, M. Suissa, G. Shemer, and L.V. Chernomordik. 2006. The C. elegans developmental fusogen EFF-1 mediates homotypic fusion in heterologous cells and in vivo. Dev. Cell. 11:471–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalho-Santos, J., and M.C. de Lima. 1998. The influenza virus hemagglutinin: a model protein in the study of membrane fusion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1376:147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell, N.C., D.J. Krysan, T. Komiyama, and R.S. Fuller. 2002. Precursor processing by kex2/furin proteases. Chem. Rev. 102:4525–4548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo, P., N. Kalkkinen, H. Sareneva, J. Paakkola, and M. Makarow. 1992. A heat shock gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae encoding a secretory glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:3671–3675. (published erratum appears in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992. 89:8857) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shemer, G., M. Suissa, I. Kolotuev, K.C. Nguyen, D.H. Hall, and B. Podbilewicz. 2004. EFF-1 is sufficient to initiate and execute tissue-specific cell fusion in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 14:1587–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, R.S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 122:19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A., E.Y. Chen, J.M. Lugovoy, C.N. Chang, R.A. Hitzeman, and P.H. Seeburg. 1983. Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains two discrete genes coding for the alpha-factor pheromone. Nucleic Acids Res. 11:4049–4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skehel, J.J., and D.C. Wiley. 2000. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:531–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.B., D. Fasshauer, R. Jahn, and A.T. Brunger. 1998. Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 A resolution. Nature. 395:347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot, P., B.D. Shur, and D.G. Myles. 2003. Cell adhesion and fertilization: steps in oocyte transport, sperm-zona pellucida interactions, and sperm-egg fusion. Biol. Reprod. 68:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomishige, N., Y. Noda, H. Adachi, H. Shimoi, A. Takatsuki, and K. Yoda. 2003. Mutations that are synthetically lethal with a gas1Δ allele cause defects in the cell wall of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 269:562–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trueheart, J., J.D. Boeke, and G.R. Fink. 1987. Two genes required for cell fusion during yeast conjugation: evidence for a pheromone-induced surface protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:2316–2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber, T., B.V. Zemelman, J.A. McNew, B. Westermann, M. Gmachl, F. Parlati, T.H. Sollner, and J.E. Rothman. 1998. SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell. 92:759–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, J.M., and M.D. Rose. 2001. Yeast mating: getting close to membrane merger. Curr. Biol. 11:R16–R20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, I.A., J.J. Skehel, and D.C. Wiley. 1981. Structure of the haemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus at 3 A resolution. Nature. 289:366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.S., X.Y. Zhang, C.P. Cartwright, and D.J. Tipper. 1992. Kex2-dependent processing of yeast K1 killer preprotoxin includes cleavage at ProArg-44. Mol. Microbiol. 6:511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]