Abstract

Spectroscopic methods such as circular dichroism and Förster resonance energy transfer are current approaches to monitoring protein conformational changes. Those analyses require special equipment and expertise. The need for fluorescence labeling of the protein may interfere with the native structure. We have developed a microtiter plate-based monoclonal antibody (mAb) epitope analysis to detect protein conformational changes in a high throughput manner. This method is based on the concept that the affinity of the antigen-binding site of an antibody for the specific antigenic epitope will change when the 3-D structure of the epitope changes. The effectiveness of this approach was demonstrated in the present study on troponin C (TnC), an allosteric protein in the Ca2+ regulatory system of striated muscle. Using TnC purified by a highly effective rapid procedure and mAbs developed against epitopes in the N- and C-domains of TnC Enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) clearly detected Ca2+-induced conformational changes in both the N-terminal regulatory domain and the C-terminal structural domain of TnC. On the other hand, Mg2+-binding to the C-domain of TnC resulted in a long-range effect on the N-domain conformation, indicating a functional significance of Ca2+-Mg2+ exchange at the C-domain metal ion-binding sites. In addition to further understanding of the structure-function relationship of TnC, the data demonstrate that the mAb epitope analysis provides a simple high throughput method for monitoring 3-D structural changes in native proteins under physiological condition and has broad applications in protein structure-function relationship studies.

Keywords: epitope affinity analysis, monoclonal antibody, ELISA, protein conformation, troponin C, Ca2+-regulation

The changes in protein three-dimensional (3-D)1 structure are commonly examined by spectroscopic methods such as circular dichroism and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET). These methods need to be performed in expert laboratories and require highly specialized equipment. Spectroscopic methods often require external labeling of the protein, which may interfere with the native structure. Therefore, a more readily accessible method would be desirable for detecting changes in protein 3-D structure.

The binding affinity between the paratope (the antigen binding site formed by the variable regions of immunoglobulin heavy and light chains) of an antibody and the specific epitope on a protein recognized by the antibody is dependent on the fit between the 3-D structures of the two proteins. Based on this concept, antibodies provide not only tools to identify specific proteins but also probes to detect and quantify changes in protein 3-D structure. The hybridoma technology has allowed the production of homogeneous monoclonal antibodies (mAb) [1] that recognize specific epitope structures on almost any given protein, generating site-specific probes for protein 3-D structural analysis. The infinite production of a mAb from the hybridoma cell line also allows the establishment of standardized probes for protein structural studies.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) is a rapid method to quantitatively determine antibody-antigen interactions [2]. Microtiter plate-based ELISA, like other solid phase immunological assays, applies repeated washes as the separation procedure and, therefore, is highly sensitive in detecting changes in antigen-antibody binding affinity to provide a quantitative measurement of the 3-D structural fit between the antigenic epitope and the antibody paratope. Together with its high throughput nature, microtiter plate-based ELISA can be readily employed for the epitope analysis of protein 3-D structures.

Troponin C (TnC) is the Ca2+-binding subunit of troponin and an allosteric protein that plays a key function in regulating muscle contraction [3,4]. During the activation of striated muscles, cytoplasmic Ca2+ rises, binds to TnC, and induces a series of conformational changes in the troponin complex and the actin thin filament to activate the actomyosin ATPase and the development of force [5]. Two homologous TnC genes (fast skeletal muscle TnC and cardiac/slow skeletal muscle TnC) have evolved in vertebrates to encode the muscle-type-specific TnC isoforms [6]. Primary structures of the two TnC isoforms are largely conserved. X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy have revealed the 3-D structure of TnC under various experimental conditions [7-9]. The structure of TnC is defined as the N-terminal regulatory domain and the C-terminal structural domain. A total of four E-F hand type divalent metal ion-binding sites are present in TnC. The C-domain of TnC contains two high affinity metal binding sites (sites III and IV) that bind Ca2+ (Kd of ∼107 M) and Mg2+ (Kd of ∼103 M) competitively. The N-domain of TnC contains two low affinity metal binding sites (Sites I and II) that bind only Ca2+ with Kd values of ∼16 μM and ∼1.7 μM, respectively, under the physiological Mg2+ concentrations [10,11]. The main structural difference between fast TnC and cardiac/slow TnC is that the N-domain Site I is inactive in cardiac/slow TnC [4]. The dynamic Ca2+-binding to the N-domain of TnC is the initial regulatory step of muscle contraction [12].

Based on the metal ion regulation of the allosteric protein TnC, we evaluated the application of ELISA epitope analysis using anti-TnC mAbs for detecting changes in the 3-D structure of TnC upon the binding of Ca2+ and/or Mg2+. The results showed a sensitive detection of Ca2+-induced conformational changes in both the N-terminal regulatory domain and the C-terminal structural domain of TnC. Mg2+-binding to the C-domain of TnC resulted in a long-range effect on the N-domain conformation, indicating a functional significance of Ca2+-Mg2+ exchange at the C-domain metal ion-binding sites. In addition to further understanding of the structure-function relationship of TnC, the data demonstrate that the mAb epitope analysis provides a simple high throughput method for monitoring 3-D structural changes in native proteins under physiological condition and has broad applications in protein structure-function relationship studies.

Materials and methods

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and Western blotting

Crude or purified TnC from bacterial expression or muscle tissue samples was homogenized in SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 2% SDS, heated to 80 °C for 5 min and clarified by centrifugation. The total protein extracts were resolved by 15% Laemmli gel with an acrylamide:bisacrylamide ratio of 29:1. The resulting gels were stained with Coomassie Blue R250 to reveal the resolved protein bands and duplicate gels were electrically blotted to nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes as previously described [13].

The recombinant N-domain and C-domain peptides of chicken fast TnC were provided by Prof. Larry Smillie, University of Alberta. They were expressed in E. coli and purified as described previously [14]. SDS-PAGE and Western blotting analysis of the TnC fragments were carried out using small-pore gels and Tris-Tricine running buffer as described previously [15]. Concentrations of the resolving and stacking gels were 15% and 4%, respectively. The acrylamide:bisacrylamide ratio was 20:1 and SDS was omitted from the resolving gel to avoid destacking effect on low molecular weight protein bands running close to the dye front.

Troponin C and its fragments are of low molecular weight and high negative charge as calculated from the amino acid sequence, rendering a high mobility during the electric Western transfer procedure. To avoid over-transfer of the TnC proteins and peptides, the semi-dry transfer conditions were determined by a series of trial experiments. Using a BioRad apparatus, the strength of transfer was reduced to 1 mA/cm2 for 6 min. After blocking in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), the blotted nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes were incubated with anti-TnC mAbs. The membranes were then washed with high stringency using Tris-buffered saline containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and 0.05% SDS, incubated with alkaline phosphatase-labeled anti-mouse IgG second antibody (Sigma Chemical Co.), washed again and developed in 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium substrate solution as previously described [16] to reveal the TnC bands.

Expression of TnC protein in E. coli and development of a rapid purification procedure

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was applied to clone full length cDNAs encoding chicken fast TnC and mouse cardiac TnC. Two μg of total RNA extracted from adult chicken breast muscle or mouse ventricular muscle by the Trizol method (Invitrogen) was used as the template. As described previously [17], total first strand cardiac cDNA was synthesized using avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase and an anchored oligo-dT primer with a dV (dA, dC or dG) at the 3'-end (TV20). From the total first strand cDNA synthesized, PCR was carried out using paired oligo nucleotide primers flanking the coding region of chicken fast TnC or mouse cardiac/slow TnC, respectively. Based on published cDNA sequences (GenBank accession numbers NM_205450 and NM_009393), the upstream forward primers were synthesized according to the sequence flanking the translation initiation codon. The downstream reverse primers were designed as a complementary sequence to the region flanking the translation termination codon. Double-stranded cDNAs were obtained by PCR using 90% Taq DNA polymerase and 10% pfu DNA polymerase with proofreading activity (Stratagene) to reduce the rate of spontaneous mutations. At restriction enzyme sites constructed in the PCR primers, the double stranded TnC cDNA was digested with NdeI and EcoRI and purified by the Prep-A-Gene glass beads-binding method (Bio-Rad Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The cDNA inserts were ligated to NdeI-EcoRI-cut pAED4 prokaryotic expression vector [15]. After transformation of competent JM109 strain E. coli cells, ampicillin-resistant colonies bearing the recombinant plasmids were identified by PCR for the presence of specific cDNA inserts. The cloned fast and cardiac/slow TnC cDNAs were confirmed by dideoxy chain termination DNA sequencing at a service facility.

Troponin C protein was expressed in E. coli from the expression vectors. As described previously [17], BL21(DE3)pLysS E. coli cells [18] were transformed with the recombinant pAED4 plasmid and cultured in LB broth containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 25 μg/ml chloramphenical. At O.D.600nm = ∼0.8, the culture was induced with 0.4 mM isopropyl-1-thiol-β-D-glactoside. After three additional hours of culture at 37 °C, the bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C.

The bacterial cells were lysed by three passes through a French cell press in 2.5 mM EDTA, 15 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsufanyl fluoride, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The bacterial lysate was fractionated by ammonium sulfate precipitation. Majority of the bacterial proteins were precipitated in the 0-80% saturation pellet and TnC was recovered in the 80-100% saturation fraction. The 80-100% pellet concentrated with TnC protein was dissolved in a minimal volume, clarified by high speed centrifugation, and loaded on a gel filtration column (Sephadex G75, Pharmacia-Amersham) in 6 M urea, 0.5 M KCl, 10 mM imidazole-HCl, pH 7.0 for size exclusive fractionation. The column was eluted with the same buffer and the fractions collected were examined by SDS-PAGE to identify the TnC peak. The purified TnC was dialyzed against three changes of cold water containing 1 mM NaHCO3 and lyophilized.

Development of mAbs against fast skeletal muscle TnC

A short term immunization procedure was applied to develop specific anti-TnC mAbs. 8-week-old female Balb/c mice were injected intraperitoneally and intramuscularly with 50 μg purified chicken fast skeletal muscle TnC antigen in 100 μl phosphate buffered saline (PBS) mixed with an equal volume of Freund's complete adjuvant. Ten days after the primary immunization, the mouse was intraperitoneally boosted daily with 100 μg of the antigen in 200 μl PBS without adjuvant on three consecutive days. Two days following the final boost, spleen cells were harvested from the immunized mouse to fuse with SP2/0-Ag14 mouse myeloma cells using 50% polyethaglycol1500 (Invitrogen) containing 7.5% dimethyl sulfoxide as described previously [19]. Hybridomas growing in 96 well culture plates were selected by HAT (0.1 mM hypoxanthine, 0.4 μM aminopterin, 16 μM thymidine) media containing 20% fetal bovine serum and screened by indirect ELISA using chicken fast TnC coating and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled, goat anti-mouse total immunoglobulin second antibody (Sigma). The anti-TnC antibody-secreting hybridomas were subcloned three or four times by limiting dilution method using young Balb/c mouse spleen cells as feeder to establish stable cell lines. The immunoglobulin isotypes were determined on the hybridoma cultural supernatant using a rat anti-mouse immunoglobulin isotyping ELISA kit from BD Biosciences according to the manufacturer's instruction. The hybridoma cells were introduced into 2,6,10,14-tetramethyl pentadecane (pristane, Sigma)-primed peritoneal cavity of Balb/c mice to produce mAb-enriched ascites fluids.

ELISA epitope analysis to detect metal ion-induced conformational changes in TnC

ELISA-based solid-phase epitope analyses were designed to measure conformational changes in TnC induced by the binding of Ca2+ and/or Mg2+ to the N-domain and C-domain metal binding sites [20]. Outlined in Fig. 1, purified TnC, N-domain and C-domain fragments were dissolved at 5 μg/mL in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM KCl (an intracellular ionic environment to maintain the natural conformation of TnC), 0 or 3 mM free Mg2+ and 0 or 0.1 mM free Ca2+ buffered by 10 mM EGTA (calculated using the WEBMAXCLITE v1.15 computer program (http://www.stanford.edu/~cpatton/webmaxc/webmaxclite115.htm). Under the four different Mg2+ and Ca2+ conditions, TnC was non-covalently coated on 96-well microtiter plates at 100 μL/well.

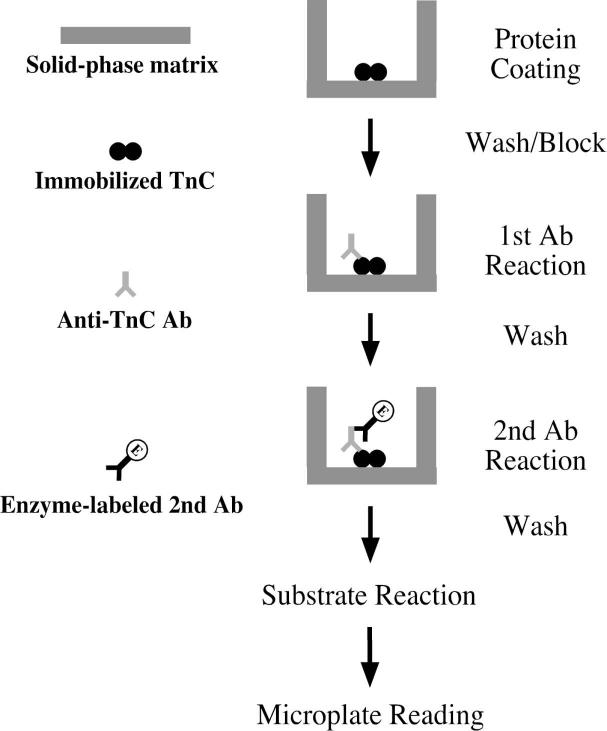

Fig. 1. ELISA epitope analysis.

This flowchart illustrates the ELISA-based epitope analysis using a mAb. The protein to be analyzed (TnC in this example) is non-covalently coated at random orientations onto the plastic surface in a 96-well microtiter plate. The coating buffer can apply various ionic, pH, and other conditions as a pre-treatment of the protein to be studied. After washing to remove unbound TnC, remaining free surface area in the assay wells is blocked by treatment with non-ionic detergent (Tween-20). A specific anti-TnC antibody will be added to the plate and incubated with the immobilized target protein (TnC) under buffer conditions that are the same as or different from that of the coating buffer. After incubation, the unbound antibody will be removed by washes under desired stringency and buffer conditions. The plate will then be incubated with enzyme-conjugated second antibody, washed again to remove unbound second antibody, and incubated with a colorimetric substrate of the enzyme. The binding affinity between the target protein and the first antibody will be quantified by enzymatic colorimetric reaction and recorded using a microplate reader.

After incubation at 4 °C overnight, the plates were washed three times for 5 min each with the coating buffer (to maintain the different metal ion conditions) plus 0.05% Tween-20 to remove any free TnC. The immobilized TnC was then incubated with anti-TnC mAbs against the N-domain or C-domain epitopes at five serial dilutions in the washing buffer with corresponding metal ion condition plus 0.1% BSA at room temperature for two hours. The plates were washed again three times to remove the unbound anti-TnC antibody and further incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG second antibody diluted in the buffer same as that used for the first antibody dilutions at room temperature for 1 hour. After washing three more times as above, H2O2-ABTS [2, 2′-azinobis-(3-ethybenzthiazoline sulfonic acid)] was added to the wells for the substrate reaction. The four Mg2+ and Ca2+ conditions tested in this study (pCa 4 and 9, plus or minus 3 mM Mg2+) were controlled throughout the ELISA procedure except for the final step of substrate development.

All experiments were done in triplicate wells and repeated at least once. A405nm for each assay well was recorded by an automated microplate reader (BioRad Benchmark) at a series of time points. The data in the linear range of the colorimetric development were used for plotting the affinity titration curves of the mAb against a TnC N- domain or C-domain epitope to investigate the effects of metal ion binding on the molecular conformation of TnC. Student's t test was performed for paired data with two-tail distribution to analyze the statistical significance of the ELISA results. All values are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Results and discussion

A rapid procedure for highly effective purification of TnC from bacterial lysate

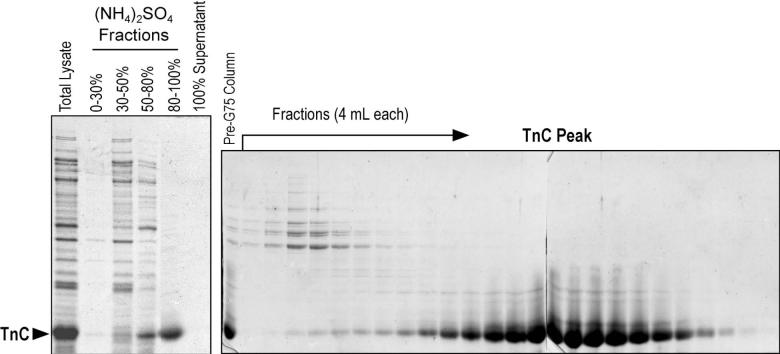

Based on the fact that TnC is a highly soluble protein, which expresses at high levels in E. coli, we developed a rapid purification of TnC protein from total bacterial lysate. As shown in Fig. 2, ammonium sulfate of 80% saturation at near neutral pH effectively precipitated almost all bacterial proteins whereas TnC almost all remained in the supernatant. Adding ammonium sulfate to 100% saturation, on the other hand, effectively precipitated all TnC that can be collected by centrifugation. Without the need of dialysis, the precipitate dissolved in a small volume can be directly loaded on a G-75 gel filtration chromatography column to further purify the TnC protein.

Fig. 2. Expression of recombinant TnC in E. coli and rapid purification.

The SDS-PAGE gels show the bacterial expression and purification profile of mouse cardiac TnC. The TnC protein recovered in the total bacterial lysate was effectively enriched by ammonium sulfate fractionation between 80-100% saturation and purified by sizing fractionation on a Sephadex G-75 sizing column. The same procedure has been reproduced for the purifications of human cardiac TnC and chicken fast TnC (data not shown).

This simple and highly effective procedure for recombinant TnC preparation takes only about 30 hours from the making of bacterial lysate to the beginning of dialysis of the purified TnC. The high ionic strength condition during the ammonium sulfate fractionation and 6 M urea in the gel filtration column separation provided a high stringency for an effective isolation of TnC from any bacterial proteins that may bind TnC. In comparison to the established purification protocols for TnC expressed in bacterial cultures [21], the eliminating of ion-exchange chromatography from the procedure also increased the final yield of TnC protein. The overloaded SDS-gel of the G75 column elution profile in Fig. 2 detected very little contaminating proteins in the TnC peak, demonstrating the effectiveness of purification.

mAbs specifically recognizing epitopes in the N- and C-domains of TnC

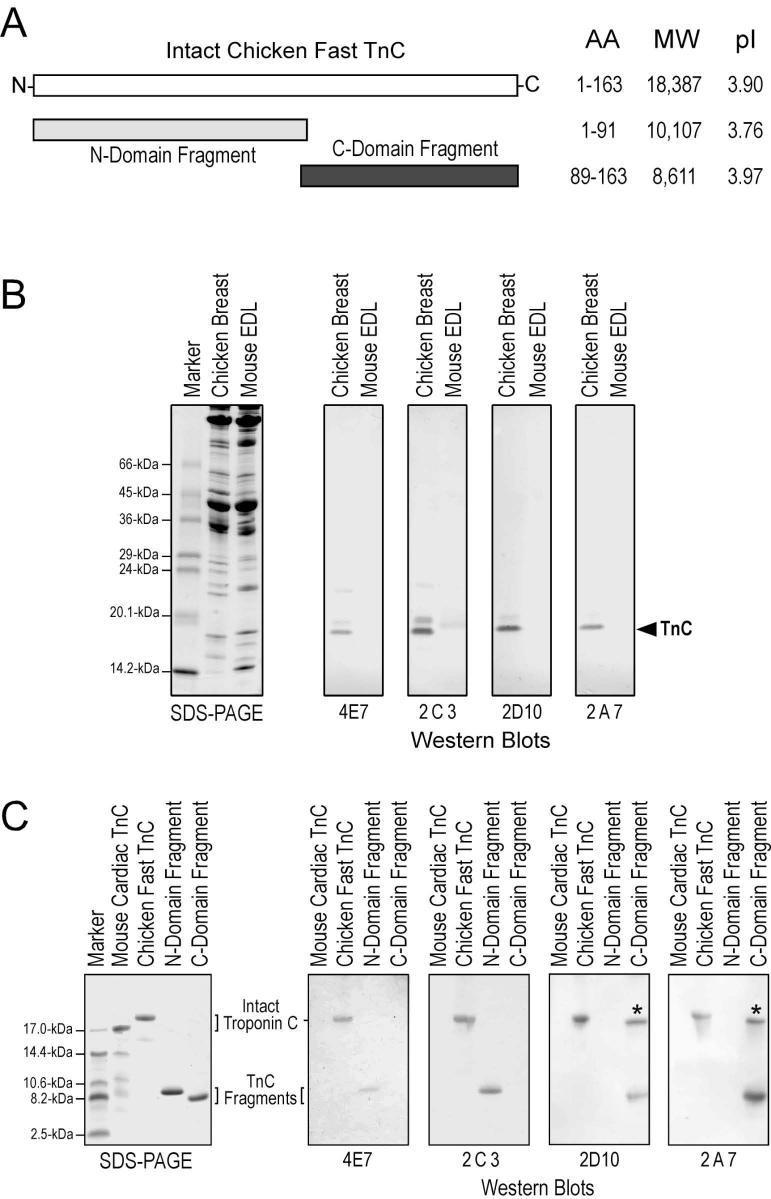

TnC is a very soluble protein highly conserved among vertebrate species [6]. These two features render an expected low immunogenicity. Nonetheless, we successfully developed 11 specific anti-TnC mAbs from a single fusion using a short term immunization protocol in Balb/c mice with chicken fast skeletal muscle TnC as immunogen. Representatives of these mAbs recognizing the N- or C-domain of TnC (Fig. 3A) were used in the present study to demonstrate the use of mAb as probes to investigate protein 3-D structural changes. The Western blots in Fig. 3B showed the specificity of four of the mAbs that recognize chicken fast skeletal muscle TnC with one (2C3) cross-reacting weakly with mouse fast TnC. None of the mAbs tested cross-reacts with cardiac TnC (Fig. 3C). Western blots on the N-domain and C-domain fragments of fast TnC (Fig. 3A) showed that mAbs 4E7 and 2C3 recognize epitopes in the N-domain and mAbs 2A7 and 2D10 recognize C-domain epitopes (Fig. 3C). Immunoglobulin isotyping showed that mAbs 2C3 and 4E7 are IgG2aκ, 2A7 is IgG1κ, and 2D10 is IgG1λ. The anti-N-domain mAb 4E7 and anti-C-domain mAb 2D10 were used in the present study as representatives to show their application in epitope analysis of metal ion-induced conformational changes in TnC.

Fig. 3. Anti-TnC mAbs.

(A) The illustration shows a linear structure map of TnC with the N-domain and C-domain fragments aligned. AA, number of amino acids; MW, molecular weight; pI, isoelectric point. (B) Total protein extracts from chicken breast and mouse extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles were resolved by SDS-PAGE and examined by Western blotting using mAbs 4E7, 2C3, 2D10 and 2A7. The results show that all four mAbs recognized the immunogen, chicken fast TnC and only 2C3 reacted weakly to mouse fast TnC. The higher molecular weight bands weakly recognized by mAbs 4E7, 2C3 and 2D10 are likely myosin light chains that are proteins homologous to TnC [6]. (C) Intact mouse cardiac TnC, intact chicken fast TnC, chicken fast TnC N-domain and chicken fast TnC C-domain were analyzed by Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. The results showed that these mAbs raised against fast TnC do not cross react with cardiac TnC. The epitopes recognized by mAbs 4E7 and 2C3 are in the N-domain fragment and that of 2D10 and 2A7 are in the C-domain fragment. The higher molecular weight band detected in the TnC C-domain fragment sample (indicated by the *) was likely aggregated dimmers, although a sufficient amount of reducing agent was present in the SDS-gel sample buffer.

Ca2+- and Mg2+-induced conformational changes in the N-domain of TnC

The effect of metal ion binding on the molecular conformation of TnC was examined by mAb ELISA epitope analysis of intact TnC as well as the isolated N- and C-domains.

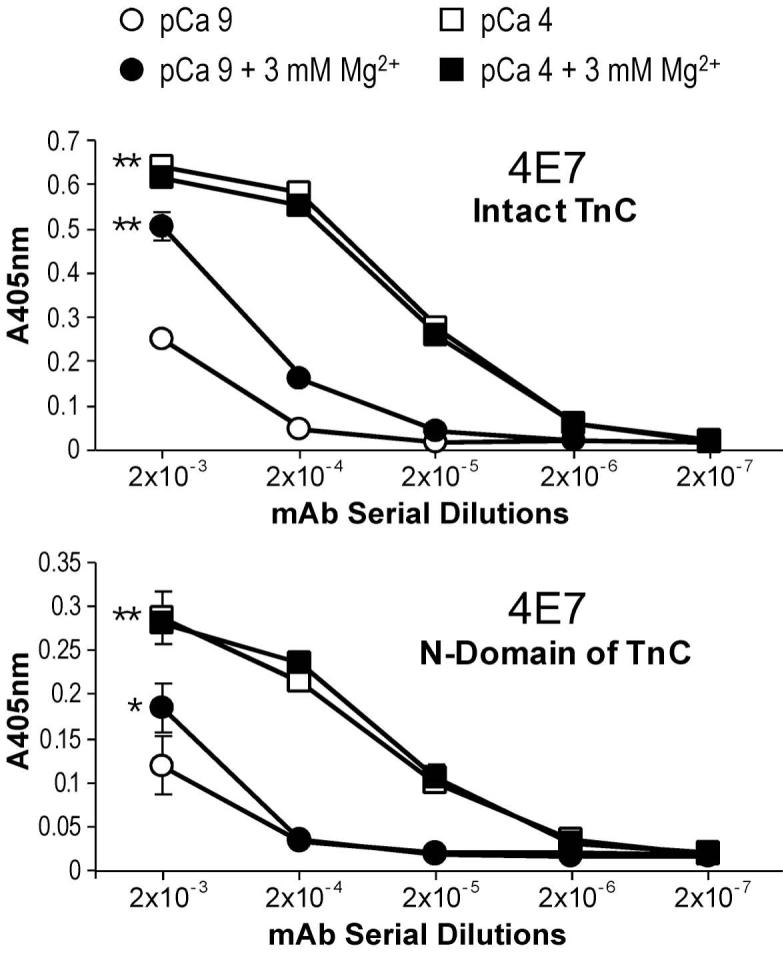

The ELISA titration curves in Fig. 4A showed that the binding affinity of the anti-TnC N-domain mAb 4E7 for intact TnC was significantly higher in the presence of Ca2+ (pCa 4) than that under the minus Ca2+ (pCa 9) condition. This result indicates a Ca2+-induced conformational change detectable at the 4E7 epitope in the N-domain of TnC. The presence of 3 mM free Mg2+ in the absence of free Ca2+ (pCa 9) resulted in a less extent of increase in the binding affinity of mAb 4E7. However, 3 mM free Mg2+ (to compete for the C-domain high affinity sites) in the presence of 0.1 mM free Ca2+ (pCa 4) did not produce any additive effect on the binding affinity of mAb 4E7. This result indicates an allosteric structure in the N-domain of TnC that has 3-D changes due to the binding of Ca2+ to the N-terminal low affinity sites independent of the presence of Ca2+ or Mg2+ at the C-domain high affinity sites. The increased mAb 4E7 affinity upon the binding of Ca2+ may reflect the open conformation of TnC N-domain in the metal bound state [22].

Fig. 4. Ca2+- and Mg2+-induced conformational change in the N-domain of TnC detected by ELISA epitope analysis.

(A) The ELISA titration curves showed that the affinity of the anti-N-domain mAb 4E7 for intact TnC was significantly higher in the presence of Ca2+ (pCa 4) than that at pCa 9 (**P<0.01), indicating a Ca2+-induced conformational change involving the mAb 4E7 epitope in the N-domain of TnC. The presence of 3 mM free Mg2+ at pCa 9 also resulted in an increase of the binding affinity of mAb 4E7 (**P<0.01), though in a less degree than the Ca2+ effect. However, 3 mM free Mg2+ at pCa 4 did not produce any additive effect on the binding affinity of mAb 4E7. (B) When the isolated N-domain fragment of TnC was tested for mAb 4E7 affinity in the presence or absence of Ca2+ and/or Mg2+, the titration curves demonstrated that Ca2+ binding-induced a conformational change in the isolated N-domain (**P<0.01) similar to that in the intact TnC. 3 mM free Mg2+, however, produce a detectable (*P<0.05) but much smaller change in the isolated N-domain than that in intact TnC. The results suggest that Mg2+ affects the N-domain conformation of intact TnC mainly through binding to the C-domain sites.

When the conformation of mAb 4E7 epitope was examined on isolated N-domain fragment of TnC, the Ca2+-iduced affinity change remained as observed in the intact TnC. However, the effect of Mg2+ was significantly diminished (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that Mg2+ affects the N-domain conformation in intact TnC (Fig. 4A) mainly through binding to the C-domain high affinity sites other than a direct binding to the N-domain low affinity sites.

Ca2+- versus Mg2+-induced conformational changes in the C-domain of TnC

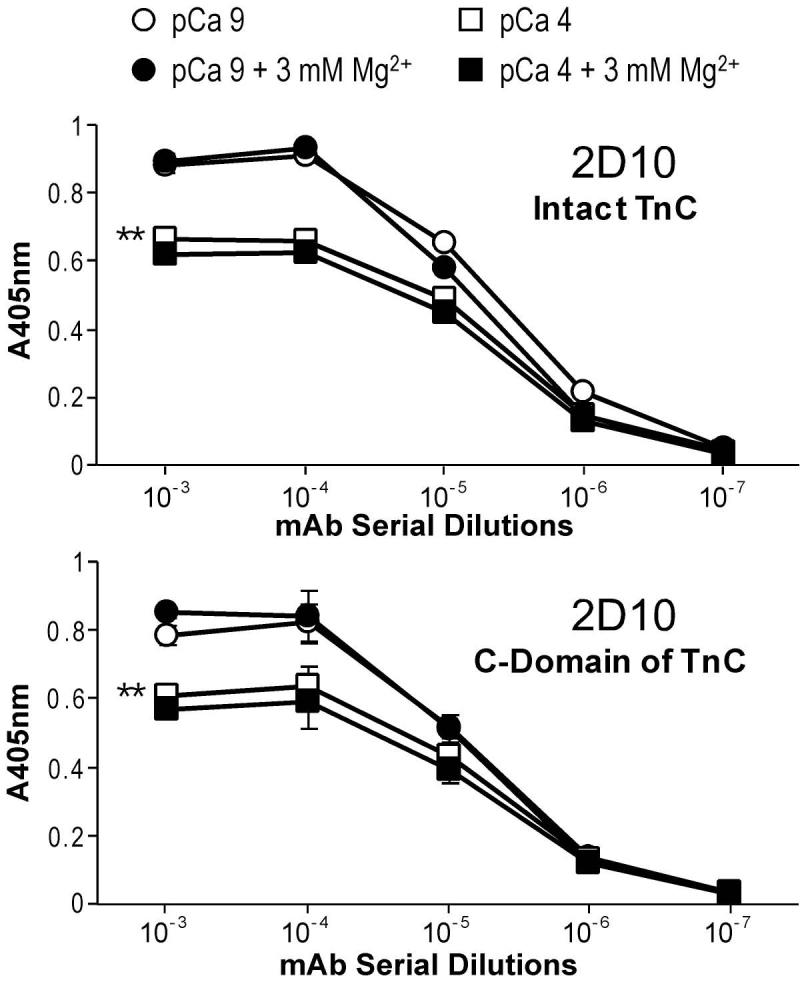

The ELISA affinity titration curves of the anti-C-domain mAb 2D10 against intact TnC (Fig. 5A) showed a significantly lower affinity in the presence of 0.1 mM Ca2+ (pCa 4) than that at pCa 9. This result indicates a Ca2+-induced conformational change that is detectable at the 2D10 epitope in the C-domain of TnC. However, the presence of 3 mM free Mg2+ in the absence of Ca2+ (pCa 9) did not produce a detectable change at the mAb 2D10 epitope and the addition of 3 mM free Mg2+ at pCa 4 did not affect the Ca2+-induced conformational effect.

Fig. 5. Ca2+-induced conformational change in the C-domain of TnC detected by ELISA epitope analysis.

(A) The ELISA titration curves showed that the affinity of the anti-C-domain mAb 2D10 for intact TnC was significantly lower in the presence of Ca2+ (pCa 4) than that at pCa 9 (**P<0.01), indicating a Ca2+-induced conformational change involving the mAb 2D10 epitope in the C-domain of TnC. The presence of 3 mM free Mg2+ alone (at pCa 9) did not result in significant change in the binding affinity of mAb 2D10 or any additive effect in the presence of Ca2+ (at pCa 4). (B) When the isolated C-domain fragment of TnC was tested for affinity to mAb 2D10, the results showed an almost identical Ca2+ effect to that on intact TnC (**P<0.01) and Mg2+ remained no significant effect. The results suggest that Ca2+ binding to the C-domain sites of TnC produces a conformational change that is absent upon the binding of Mg2+.

When the isolated C-domain fragment of TnC was tested for metal ion-induced conformational change at the mAb 2D10 epitope, the results in Fig. 5B showed the same Ca2+ and Mg2+ effects as that on the intact TnC. The results demonstrate that the different effect of Ca2+ versus Mg2+ on the C-domain conformation of TnC was due directly to the binding to the C-domain sites. While 0.1 mM Ca2+ is able to bind both the N-domain high affinity sites and the C-domain low affinity sites, Mg2+ at 3 mM will only bind the C-domain high affinity sites. Therefore, the data indicate a conformational change in the C-domain of TnC induced by Ca2+-binding but not Mg2+-binding. Similar to the effect of Ca2+ on the mAb 2D10 epitope, a previous study observed a Ca2+ induced decrease in the affinity of fast TnC to a mAb [23]. In contrast to the Ca2+-induced affinity increase for the anti-N-domain mAb 4E7 reflecting an open conformation (Fig. 4), the decreased affinity of the anti-C-domain mAb 2D10 upon the binding of Ca2+ versus that of Mg2+ reflects a more compact conformation of TnC C-domain in the Ca2+ bound state as suggested by the reduced radius of gyration of TnC C-domain upon Ca2+ binding [24].

Implications of the metal ion-induced conformational changes detected by ELISA epitope analysis

The results in Fig. 4B showed that 3 mM Mg2+ had a weak conformational effect on the mAb 4E7 epitope in the isolated N-domain of TnC at pCa 9. This observation implicated that Mg2+ was able to weakly bind the N-domain low affinity sites of TnC in the absence of Ca2+. A previous two-dimensional 1H NMR study [25] investigated the binding of Mg2+ to intact rabbit fast TnC. In the presence of 2 or 4 bound Ca, fast-exchange behavior was observed for residues located at the low-affinity Ca2+-binding sites in the N-domain. Their results suggest that Mg2+ bind to the N-domain as well as the C domain, and all Ca2+-binding sites in both the N- and C-domains can bind Mg2+ ions. However, the Mg2+ concentration used in the NMR study was much higher (over 50 mM) than the physiological concentration used in our study. To demonstrate the effect of a physiological concentration of Mg2+ on the N-domain conformation of TnC, our experiment showed that while 3 mM Mg2+ did not affect the C-domain epitope recognized by mAb 2D10 (Fig. 5B), Mg2+ had a conformational effect on the N-domain of TnC as detected at the mAb 4E7 epitope, mainly through its binding to the C-domain high affinity sites (Fig. 4A).

The different effects of Ca2+ and Mg2+ bindings on the C-domain conformation of TnC shown in Fig. 5B may reflect a functional significance of Ca2+-Mg2+ exchange at the C-domain high affinity metal ion-binding sites [26]. Together with the differentiated secondary effects of Ca2+ and Mg2+ on the N-domain conformation via binding to the C-domain sites (Fig. 4A), the C-domain structural changes due to Ca2+-Mg2+ exchange might have a functional significance in the Ca2+-regulation of muscle contraction.

Broad applications of antibody epitope analysis in the study of protein conformation

Antibody-antigen binding is a protein-protein interaction that depends on 3-D structure fits between the antigenic epitope and the antibody paratope. This is a well-known foundation for the classical application of antibodies as tools for identifying specific protein structures through binding affinity-based recognition of the antigenic epitopes. In the present study, we employed mAbs against TnC, a typical metal ion-modulated allosteric protein, to demonstrate the application of antibody affinity analysis to sensitively detect protein conformational changes. Monoclonal antibodies provide homogenous probes that recognize specific epitopes. Therefore, mAb epitope analysis can detect conformational changes in specific regions/sites of a protein [16, 27, 28], especially useful in monitoring structural dynamics and folding states [29]. In avian breast muscle fast troponin T studies, we used this analysis to demonstrate Zn2+ and Cu2+ binding induced long-range conformational changes [16], which were confirmed by fluorescence spectroscopy [28]. Using the microtiter plate-based ELISA mAb epitope analysis, we demonstrated in a previous study of smooth muscle calponin the detection of global conformational changes produced by phosphorylation or substitution of a single amino acid [27].

We have demonstrated that the epitope affinity analysis may also use polyclonal antibodies recognizing multiple epitopes on a protein to detect the overall conformational changes [16]. This observation indicates a broad distribution of conformation-sensitive epitopic structures in a protein and suggests that many existing antibodies may be used as probes to study changes in protein conformation. Combined with the highly affinity-dependent solid-phase ELISA method, antibody epitope analysis is a sensitive method to detect changes in the 3-D fitting between the antigen epitope and the antibody paratope, presenting a valuable approach to monitor protein conformational changes. An advantage over solution structure analyses is that the buffer conditions in each step of the ELISA epitope analysis can be varied to investigate ionic, ligand and pH effects. The high throughput feature of microtiter plate assay further allows rapid screening of a large number of experimental conditions in order to lay groundwork for high-resolution conformational investigations. Therefore, the ELISA epitope analysis has a broad application in protein structure-function relationship studies.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Larry Smillie, University of Alberta, for providing the fast TnT N-domain and C-domain proteins and critical reading of this manuscript. This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health AR048816 and HL078773 to J-PJ.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used:

3-D, three-dimensional; BSA, bovine serum albumin; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay; HRP, horse radish peroxidase; mAb, monoclonal antibody; PAGE, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; PBS, phosphate buffered saline; pCa, -log of free Ca2+; TBS, Tris-buffered saline (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5); TnC, troponin C.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kohler G, Milstein C. Nature. 1975;256:495–497. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engvall E, Perlman P. Immunochemistry. 1971;8:871–874. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(71)90454-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parmacek MS, Leiden JM. Circulation. 1991;84:991–1003. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.3.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gergely J, Grabarek Z, Tao T. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1993;332:117–123. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2872-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon AM, Homsher E, Regnier M. Physiol. Rev. 2000;80:853–924. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins JH. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1991;12:3–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01781170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herzberg O, James MN. J. Mol. Biol. 1988;203:761–779. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satyshur KA, Pyzalska D, Greaser M, Rao ST, Sundaralingam M. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:40–49. doi: 10.1107/S090744499300798X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gagne SM, Li MX, McKay RT, Sykes BD. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1998;76:302–312. doi: 10.1139/bcb-76-2-3-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li MX, Gagné SM, Tsuda S, Kay CM, Smillie LB, Sykes BD. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8330–8340. doi: 10.1021/bi00026a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li MX, Gagné SM, Spyracopoulos L, Kloks CP, Audette G, Chandra M, Solaro RJ, Smillie LB, Sykes BD. Biochemistry. 1997;36:12519–12525. doi: 10.1021/bi971222l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herzberg O, Moult J, James MNG. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:2638–2644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Z, Biesiadecki BJ, Jin J-P. Biochemistry. 2006;45:11681–11694. doi: 10.1021/bi060273s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li MX, Chandra M, Pearlstone JR, Racher KI, Trigo-Gonzalez G, Borgford T, Kay CM, Smillie LB. Biochemistry. 1994;33:917–925. doi: 10.1021/bi00170a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin J-P. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:6908–6916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Jin J-P. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14519–14528. doi: 10.1021/bi9812322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biesiadecki B, Jin J-P. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:18459–18468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Studier FW, Rosenberg AH, Dunn JJ, Dubendorff JW. Meth. Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin J-P, Malik ML, Lin JJC. Hybridoma. 1990;9:597–608. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1990.9.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langer GA. FASEB J. 1992;6:893–902. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.3.1310947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearlstone JR, Smillie LB. Methods Mol. Biol. 2002;172:161–174. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-183-3:161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearlstone JR, Chandra M, Sorenson MM, Smillie LB. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:35106–35115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strang PF, Potter JD. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1992;13:308–314. doi: 10.1007/BF01766458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujisawa T, Ueki T, Iida S. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 1990;107:343–351. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsuda S, Ogura K, Hasegawa Y, Yagi K, Hikichi K. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4951–4958. doi: 10.1021/bi00472a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finley N, Dvoretsky A, Rosevear PR. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1439–1446. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin J-P, Walsh MP, Sutherland C, Chen W. Biochem. J. 2000;350:579–588. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin J-P, Root DD. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11702–11713. doi: 10.1021/bi9927437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldberg ME. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1991;16:358–362. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90148-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]