Abstract

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease that causes salivary and lacrimal gland tissue destruction resulting in impaired secretory function. Although lymphocytic infiltration of salivary epithelium is associated with SS, the mechanisms involved have not been adequately elucidated. Our previous studies have shown that the G protein-coupled P2Y2 nucleotide receptor (P2Y2R) is up-regulated in response to damage or stress of salivary gland epithelium, and in salivary glands of the NOD.B10 mouse model of SS-like autoimmune exocrinopathy. Additionally, we have shown that P2Y2R activation up-regulates vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) expression in endothelial cells leading to the binding of monocytes. The present study demonstrates that activation of the P2Y2R in dispersed cell aggregates from rat submandibular gland (SMG) and in human submandibular gland ductal cells (HSG) up-regulates the expression of VCAM-1. Furthermore, P2Y2R activation mediated the up-regulation of VCAM-1 expression in HSG cells leading to increased adherence of lymphocytic cells. Inhibitors of EGFR phosphorylation and metalloprotease activity abolished P2Y2R-mediated VCAM-1 expression and decreased lymphocyte binding to HSG cells. Moreover, silencing of EGFR expression abolished UTP-induced VCAM-1 up-regulation in HSG cells. These results suggest that P2Y2R activation in salivary gland cells increases the EGFR-dependent expression of VCAM-1 and the binding of lymphocytes, a pathway relevant to inflammation associated with SS.

Keywords: P2Y2 receptor, VCAM-1, EGF receptor, metalloproteases, inflammation, Sjögren’s Syndrome

Introduction

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease that is characterized by persistent dryness of the mouth and eyes due to functional impairment of the salivary and lacrimal glands, respectively (Kassan and Moutsopoulos, 2004; Ramos-Casals and Font, 2005). Despite extensive molecular, histological and clinical studies, the underlying cause of SS and its pathogenesis remain unknown (Garcia-Carrasco et al., 2006). SS may occur alone (primary SS) or in association with other autoimmune diseases (secondary SS). SS disproportionately affects women at a ratio of 9:1 over men and is typically diagnosed in the 5th or 6th decade of life (Jonsson et al., 2002). Diagnostic criteria for SS include lymphocytic infiltration of salivary glands, dry mouth, dry eyes (keratoconjunctivitis sicca/KCS) and circulating autoantibodies to Ro/SS-A and La/SS-B antigens (Vitali et al., 2002).

Glandular damage in SS is mediated by T lymphocytes, mainly primed CD4+ T helper lymphocytes that comprise ~60% of the infiltrating lymphocytes, whereas CD8+ T cells comprise ~10–20%, B lymphocytes ~20% and monocytes/macrophages less than 2% of the lymphocytic infiltrate in SS-affected glands (Zumla et al., 1991; Matsumoto et al., 1996; Xanthou et al., 1999; Jonsson et al., 2002). Lymphocytic infiltrates in SS salivary gland biopsies have been shown to be in direct contact with the glandular epithelial cells, indicating a causal role for cell-mediated immune responses in the pathogenesis of SS (Fox, 1996). The localization of lymphocytic infiltrates in salivary vascular endothelium in SS is associated with the increased expression of cell surface adhesion molecules that promote the binding of immune cells, particularly vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and intracellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) (Aziz et al., 1992; St. Clair et al., 1992; Edwards et al., 1993; Saito et al., 1993). In addition, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 are expressed in salivary gland epithelium of SS patients (Aziz et al., 1992; St. Clair et al., 1992; Saito et al., 1993; Tsunawaki et al., 2002) enabling direct interaction with infiltrating lymphocytes. The pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα stimulates the rapid expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 on endothelial and epithelial cells (Osborn et al., 1989; Burke-Gaffney and Hellewell, 1996; Atsuta et al., 1997; Spoelstra et al., 1999; Tu et al., 2001; Woo et al., 2005). Cytokine-mediated up-regulation of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 facilitates the recruitment of very late antigen-4 (VLA-4) and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) expressing T cells that accompany lymphocytic cell infiltration in SS salivary glands (Saito et al., 1993), however the mechanisms mediating the expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 are not fully understood.

The G protein-coupled P2Y2 nucleotide receptor (P2Y2R), distinguished pharmacologically by its ability to be equivalently activated by ATP or UTP, is barely detectable in normal rat salivary glands but is up-regulated upon disruption of tissue homeostasis by enzymatic dispersal and culture of cells from rat submandibular, parotid, or sublingual glands as a function of time in culture (Turner et al., 1997). P2Y2R up-regulation also occurs in rat salivary glands in vivo 3 days after SMG ductal ligation (Ahn et al., 2000), and in SMG of the NOD.B10 mouse model of autoimmune exocrinopathy that has characteristics similar to human SS (Schrader et al., 2005). The physiological consequences of P2Y2R up-regulation in salivary glands are unknown. Our recent studies have demonstrated that stress-induced up-regulation of P2Y2 nucleotide receptors (P2Y2Rs) in vascular endothelium leads to increased expression of VCAM-1 that promotes monocyte adherence and transendothelial migration (Seye et al., 2003), suggesting that P2Y2Rs for cytokine-like nucleotides play a role in inflammation. Since P2Y2Rs are up-regulated due to stress or injury in salivary gland epithelium (Turner et al., 1997; Ahn et al., 2000; Schrader et al., 2005), studies in this manuscript hypothesize that activation of P2Y2Rs leads to increased expression of cell adhesion molecules in human salivary gland cells to promote the binding and infiltration of lymphocytes associated with salivary gland destruction and hyposalivation (i.e., xerostomia) in SS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of dispersed cell aggregates from rat SMG

Dispersed cell aggregates from SMGs of Sprague-Dawley rats were prepared as described previously (Turner et al., 1990). Protocols conformed to Animal Care and Use guidelines of the University of Missouri-Columbia. Briefly, rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium injection (125 mg/kg body weight) and SMGs removed. Glands were finely minced in dispersion medium consisting of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM)-Ham’s F-12 (1:1) (Hyclone, Logan, UT) and 0.2 mM CaCl2, 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA), 50 units/ml collagenase (Worthington Biochemical, Freehold, NJ), and 400 units/ml hyaluronidase at 37°C for 40 min with aeration (95% O2-5% CO2). Cell aggregates in dispersion medium were suspended by pipetting at 20, 30, and 40 min. The dispersed cell aggregates were washed with enzyme-free assay buffer (120 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 15 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), pH 7.4) containing 1% (w/v) BSA and filtered through nylon mesh and cultured in DMEM-F12 (1:1) containing 2.5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) and the following supplements: 0.1 μM retinoic acid, 80 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 2 nM triiodothyronine, 5 mM glutamine, 0.4 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 5 μg/ml insulin, 5 μg/ml transferrin, 5 ng/ml sodium selenite, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, and 8.4 ng/ml cholera toxin. Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified 95% air and 5% CO2 atmosphere for 0 to 72 h.

2.2. HSG and Jurkat lymphocytic cell culture conditions

HSG cells were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 5% (v/v) FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Jurkat CD4+ lymphocytic cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 5% (v/v) FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. HSG grown to 80% confluence were cultured in serum-free DMEM overnight before the addition of inhibitors or agonists. In some experiments, HSG cells were pre-incubated for 30 min in serum-free DMEM with or without the selective EGFR inhibitor AG1479 (10 μM), the selective metalloprotease inhibitor TAPI-2 (10 μM) or the selective Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 μM). Then, cells were incubated for 6 h in the absence or presence of UTP (0.1–100 μM) or EGF (100 nM) and lysed in 200 μl of 2X Laemmli buffer (120 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 2% (w/v) SDS, 5% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.002% (w/v) bromophenol blue) for Western blot analysis.

2.3. siRNA-mediated suppression of EGFR and P2Y2R expression

HSG cells were transfected in reduced-serum medium (Opti-MEM) with 100 nM SMARTpool of double-stranded small interference EGFR RNA (i.e., EGFR siRNA; UPSTATE, Charlottesville, VA) to suppress EGFR expression, or double-stranded small interference P2Y2R RNA (i.e., P2Y2R siRNA; UPSTATE, Charlottesville, VA) to suppress P2Y2R expression, whereas 100 nM non-specific siRNA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used as a negative control. Transfection of cells with EGFR siRNA was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions at 1:2.5 (v/v) siRNA:Lipofectamine 2000. All siRNAs were dissolved in RNase-free buffer as described in UPSTATE’s protocol. After 24 h, cells were treated in the absence or presence UTP (100 μM) or EGF (100 nM) in serum-free DMEM for 6 h and lysed in 200 μl of 2X Laemmli buffer for Western blot analysis. The transfection efficiency of EGFR siRNA was determined by Western analysis and the transfection efficiency of P2Y2R siRNA was determined by Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) analysis.

2.4. RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from transfected HSG cells using a RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA), followed by treatment with ribonuclease-free deoxyribonuclease (DNase) (Ambion, Austin, TX). The quantity and quality of total RNA was assessed by spectrophotometry and agarose gel electrophoresis, respectively, after the DNase treatment. cDNA synthesis was performed using a first strand cDNA synthesis kit (BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA) with 1 μg of total RNA and oligo dT primer. Ten percent of the cDNA was used as template in the PCR with primers specific for P2Y2R cDNA. For amplification of P2Y2R cDNA, the upstream primer, 5′-CTTCAACGAGGACTTCAAGTACGTGC-3′, and the downstream primer, 5′-CATGTTGATGGCGTTGAGGGTGTGG-3′ (DNA Technologies Inc., Coralville, IA), were used to amplify a 778-bp fragment. Positive controls for housekeeping mRNA were performed using human glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (hG3PDH) primers according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech., Palo Alto, CA) to amplify a 983-bp fragment. The PCR reaction was performed with 3 units of Vent (exo−) DNA polymerase, 0.25 units of Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), 2 mM MgCl2, and 20 pmol of each primer in a 50 μl reaction volume. The PCR conditions were as follows: 1 min at 94°C, then 30 cycles of denaturation for 1 min at 94°C, annealing for 1 min at 60°C, and extension for 1 min at 72°C, followed by a 7 min extension at 72°C. The resulting products were resolved on a 1% (w/v) agarose ethidium bromide gel.

2.5. Binding of Jurkat cells to HSG cells

To quantitate adherence of lymphocytes to HSG cell monolayers grown in 12 well plates at an initial density of 5.0 × 105 cells per well, Jurkat lymphocytic cells (106) were labeled with the green fluorescent dye PKH2 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and were then added to 80% confluent cultures of HSG cells for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed in RPMI serum-free medium, and adherent lymphocytes were counted using fluorescence microscopy. To investigate the involvement of cell adhesion molecules in lymphocyte binding, HSG cells were treated with UTP (100 μM) for 6 h at 37°C followed by the addition of 10 μg/ml mouse anti-human VCAM-1 (P3C4), mouse anti-human ICAM-1 (P2A4), or mouse anti-human E-selectin (P2H3) antibodies (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA), for 45 min before addition of lymphocytes. Cell numbers were determined in seven different fields of view in nine culture wells from three experiments.

2.6. Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were sonicated for 5 sec with a Branson Sonifier 250 (microtip; output level 5; duty cycle 50%) and boiled for 3 min. The lysates were subjected to 7.5% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on mini-gels, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 h with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline (0.137 M NaCl, 0.025 M Tris (hydroxymethyl)-aminomethane, pH 7.4) containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 (TBST) and immunoblotted overnight at 4°C in TBST containing 3% (w/v) BSA and 0.02% (w/v) sodium azide and goat anti-rabbit VCAM-1 antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) that recognizes an epitope corresponding to amino acids 25–300 mapping within the N-terminus of VCAM-1, goat anti-rabbit EGFR antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) that recognizes an epitope corresponding to amino acids 1005–1016 mapping at the C-terminus of EGFR, or goat anti-rabbit phospho-Src antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) that recognizes the phosphorylated tyrosine 416 of human Src. Membranes were washed 3 times with TBST during a 45 min period and incubated with peroxidase-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:2,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at room temperature for 1 h. After three more washes with TBST, the membrane was subjected to chemiluminescence detection and the protein bands were visualized on X-ray film and quantified using a computer-driven scanner and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). For signal normalization, membranes were treated with stripping buffer (0.1 M glycine pH 2.9 and 0.02% (w/v) sodium azide) and reprobed with goat anti-rabbit (total) extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or goat anti-mouse Src antibody (1:1,000 dilution; UPSTATE). All experiments were performed in duplicate and repeated at least three times.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Quantitative results are presented as means ± S.E.M. of three or more determinations. P values <0.05 calculated from a two tailed t-test are taken to represent significant differences.

3. Results

3.1. P2Y2R activation up-regulates VCAM-1 expression in dispersed cell aggregates from rat SMG and in HSG cells

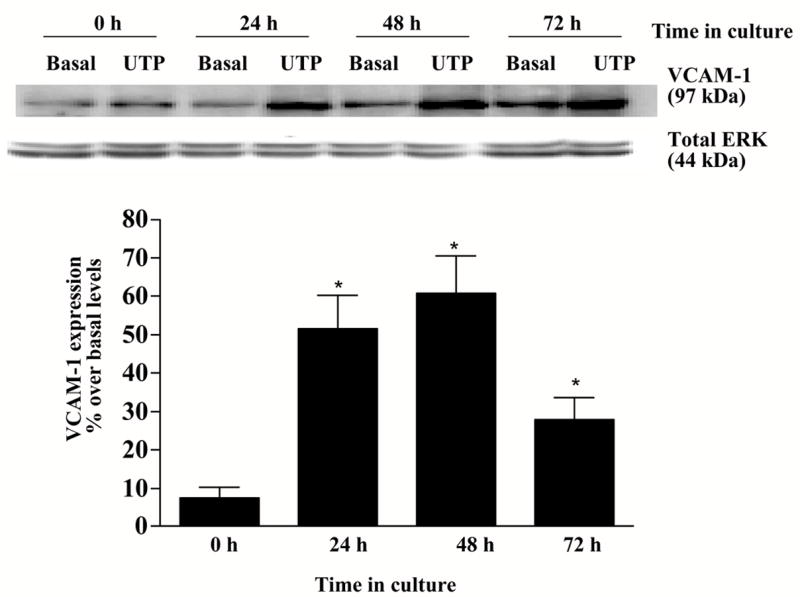

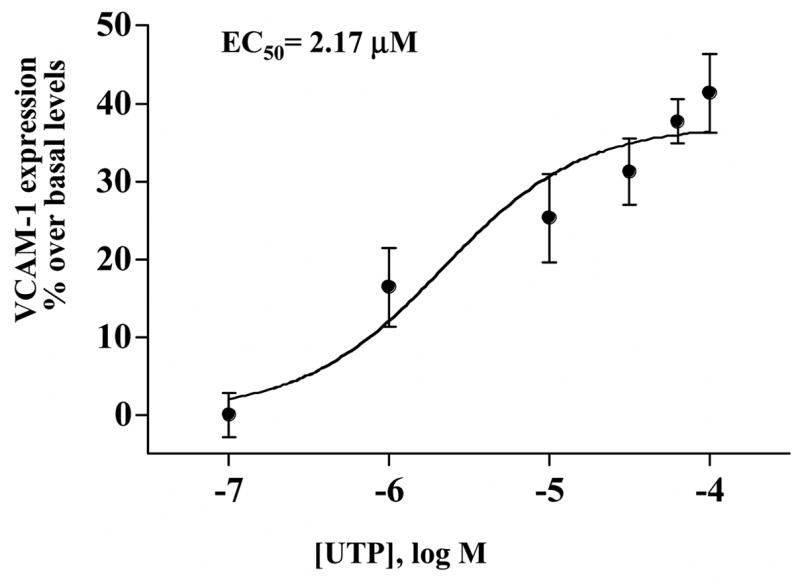

Dispersed cell aggregates from rat SMG were cultured for 0–72 h and then incubated in the absence or presence of the P2Y2R agonist UTP (100 μM) for 6 h. Cells cultured for 24–72 h exhibited a significant increase in the expression of VCAM-1 in response to UTP whereas cells cultured for 0 h before UTP addition did not exhibit a significant increase in VCAM-1 as compared to untreated controls (Fig. 1), consistent with the time-course for up-regulation of the P2Y2R in dispersed rat SMG cells (Turner et al., 1997). In dispersed rat SMG cells cultured for 48 h, UTP (0.1–100 μM) caused a dose-dependent increase in VCAM-1 expression with an EC50 of 2.17 μM (Fig. 2), a value characteristic of P2Y2R activation (Parr et al., 1994; Turner et al., 1997; Garrad et al., 1998; Turner et al., 1998; Camden et al., 2005). These data are consistent with the conclusion that activation of the P2Y2R receptor by UTP increases VCAM-1 expression in rat salivary acinar cells from submandibular gland.

Figure 1.

P2Y2R activation up-regulates VCAM-1 expression in dispersed cell aggregates from rat SMG. Dispersed rat SMG cells were cultured for 0–72 h and then incubated in the absence or presence of UTP (100 μM) for 6 h at 37°C. Protein extracts from SMG cells were subjected to Western blot analysis and normalized to total ERK as described in “Methods”. Data represent the means ± S.E.M. of results from three experiments, where *p<0.05 indicates a significant difference from cells cultured for 0 h before UTP addition (lower panel). Results from a representative experiment are shown at the top of the figure.

Figure 2.

UTP dose-dependent induction of VCAM-1 expression in dispersed cell aggregates from rat SMG. Dispersed SMG cells cultured for 48 h were incubated in the absence or presence of UTP at the indicated concentrations for 6 h at 37°C. Protein extracts from SMG cells were subjected to Western blot analysis and normalized to total ERK as described in “Methods”. Data represent the means ± S.E.M. of results from three experiments.

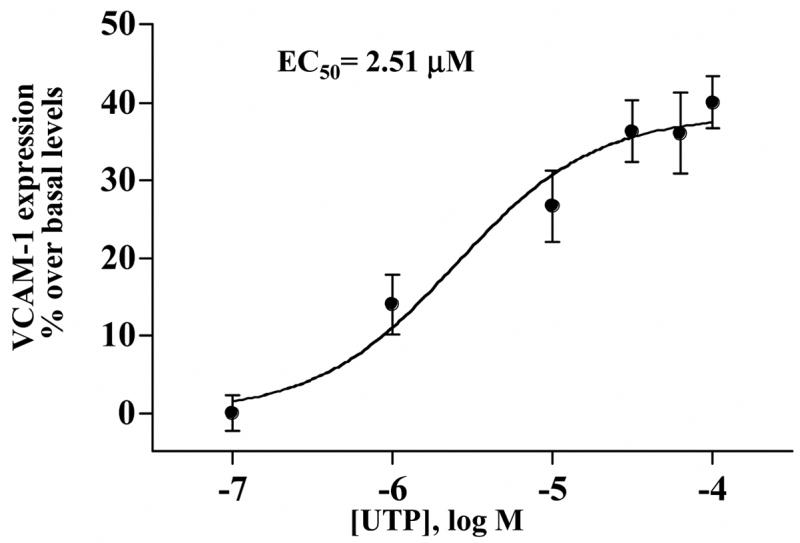

The human submandibular gland (HSG) ductal cell line gland expresses endogenous P2Y2Rs (Yu and Turner, 1991). In HSG cells, UTP (0.1–100 μM) also induced VCAM-1 expression with an EC50 of 2.51 μM (Fig. 3). This result suggests that activation of the P2Y2R receptor by UTP increases VCAM-1 expression not only in freshly isolated cells from rat submandibular glands but also in a submandibular gland cell line of human origin. In contrast to VCAM-1 expression, UTP did not significantly increase the expression of ICAM-1, PNAd, E-selectin or E-cadherin in HSG cells (data not shown). Among other known uridine nucleotide receptors, HSG cells do not express P2Y4R mRNA but express P2Y6R mRNA (data not shown), although no functional response to the P2Y6R agonist UDP was detected as measured by increases in [Ca2+]i (data not shown). Thus, UTP-induced activation of VCAM-1 expression in HSG cells is likely mediated by the P2Y2R.

Figure 3.

UTP dose-dependent induction of VCAM-1 expression in HSG cells. Cells were incubated in the absence or presence of UTP at the indicated concentrations for 6 h at 37°C. Protein extracts from HSG cells were subjected to Western blot analysis and normalized to total ERK as described in “Methods”. Data represent the means ± S.E.M. of results from three experiments.

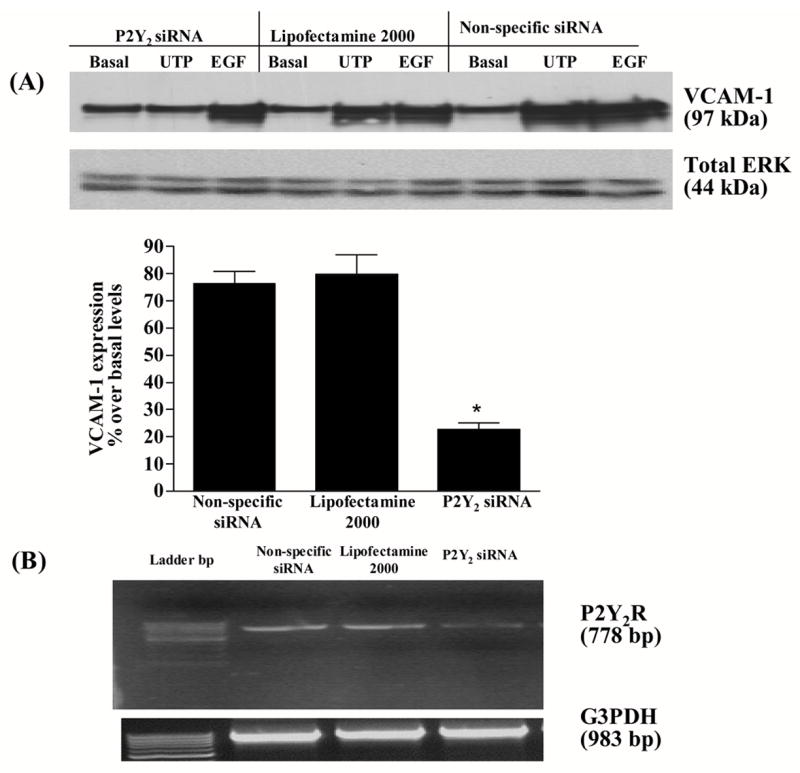

3.2. The P2Y2R mediates VCAM-1 expression in HSG cells

To unambiguously determine whether the P2Y2R was the nucleotide receptor responsible for UTP-induced VCAM-1 up-regulation, HSG cells were transfected with P2Y2R siRNAs to inhibit expression of the endogenous P2Y2R. Inhibition of P2Y2R expression with the corresponding siRNAs blocked UTP-stimulated VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 4 panel A) but not EGF-stimulated VCAM-1 expression, whereas non-specific siRNA or lipofectamine treatment of cells did not affect UTP-stimulated VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 4 panel A). The extent of suppression of P2Y2R mRNA expression by the siRNAs is shown in (Fig. 4 panel B). Based on these data, we conclude that the P2Y2R is the primary nucleotide receptor responsible for VCAM-1 up-regulation in HSG cells.

Figure 4.

P2Y2R-mediated VCAM-1 expression in HSG cells is decreased by P2Y2R siRNA. HSG cells were transfected with SMARTpool small interfering P2Y2R RNA (100 nM) using lipofectamine 2000, as described in “Methods”. Cells transfected with non-specific siRNA or treated with lipofectamine alone served as controls. Transfected cells were incubated in the absence or presence of UTP (100 μM) for 6 h at 37°C. UTP-induced VCAM-1 expression was detected by Western blot analysis (panel A) and P2Y2R and hG3PDH mRNA expression was measured by RT-PCR (panel B) as described in “Methods”. Data in panel A represent the means ± S.E.M. of results from three experiments, where *p<0.05 indicates a significant difference from cells transfected with non-specific siRNA. Results from a representative experiment are shown at the top of panel A.

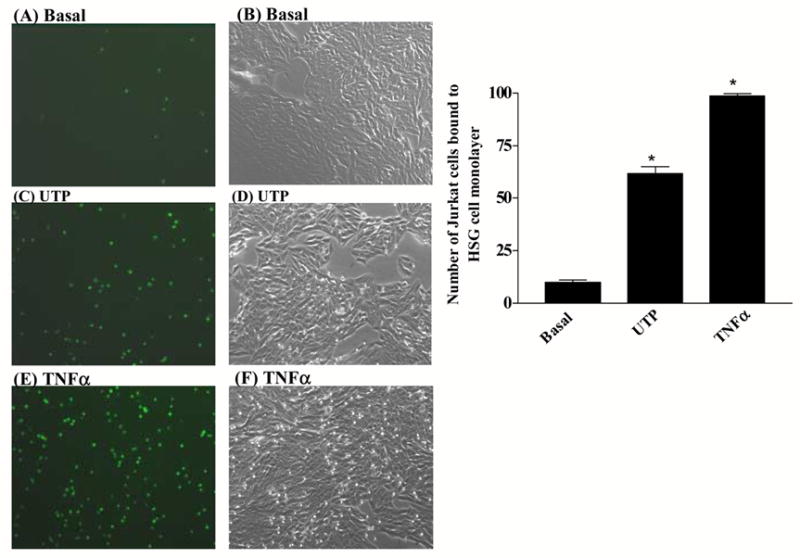

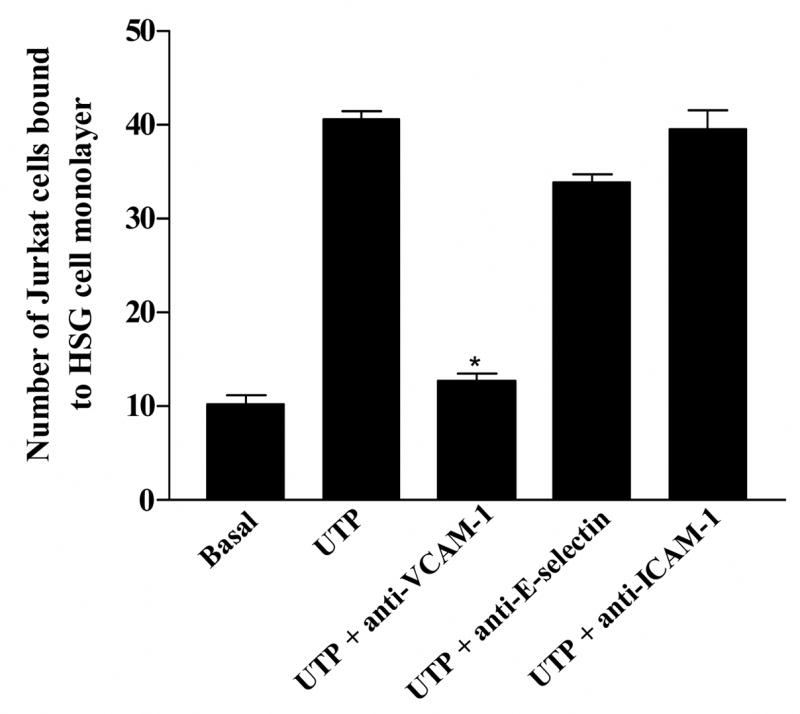

3.3. VCAM-1 mediates lymphocyte binding to HSG cells

UTP caused an ≈ 6.2 fold increase in the adherence of Jurkat lymphocytic cells to HSG cells (Fig. 5 panel C), as compared to the absence of UTP (Fig. 5 panel A). TNFα, known to up-regulate VCAM-1 expression in endothelial and epithelial cells (Osborn et al., 1989; Burke-Gaffney and Hellewell, 1996; Atsuta et al., 1997; Spoelstra et al., 1999; Tu et al., 2001; Woo et al., 2005), caused an ≈ 10 fold increase in the adherence of Jurkat cells to HSG cells (Fig. 5 panel E) as compared to the absence of ligand (Fig. 5 panel A). Fig. 5 panels B, D and F show light micrographs of the HSG cell monolayers at 10× magnification. Incubation of HSG cells with anti-VCAM-1 antibody, but not with anti-ICAM-1 antibody or anti-E-selectin antibody, significantly decreased Jurkat cell binding to UTP-stimulated HSG cells (Fig. 6) indicating that P2Y2R-mediated VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 3) regulates lymphocyte binding to HSG cells. These data support the hypothesis that up-regulation and activation of P2Y2Rs in salivary gland epithelium promotes lymphocyte infiltration, a critical event in the pathogenesis of SS.

Figure 5.

P2Y2R activation by UTP in HSG cells increases lymphocyte binding. Confluent serum-starved HSG cell cultures in 12-well plates were incubated in the absence (Basal; panels A and B) or presence of 100 μM UTP (panels C and D) or 10 ng/ml TNFα (panels E and F) for 6 h at 37°C. Binding of PKH2-labeled Jurkat lymphocyte cells to HSG cell monolayers was determined as described in “Methods”. Fluorescence of PKH2-bound Jurkat cells (panels A, C and E) and light micrographs of HSG cell monolayers at 10X magnification (panel B, D and F) are shown. Data on the right represent the means ± S.E.M. of results from three experiments, where *p<0.05 indicates a significant difference from basal levels.

Figure 6.

Lymphocyte binding to UTP-stimulated HSG cell monolayers is mediated by VCAM-1. Confluent serum-starved HSG cell cultures in 12-well plates were incubated in the absence (Basal) or presence of UTP (100 μM) for 6 h at 37°C. Binding of PKH2-labeled Jurkat cells to HSG cell monolayers was determined as described in “Methods”. For some HSG cell cultures, 10 μg/ml anti-VCAM-1, anti-E-selectin, or anti-ICAM-1 antibody was added to UTP-stimulated HSG cells for 45 min prior to the addition of Jurkat cells. Data represent the means ± S.E.M. of results from three experiments, where *p<0.05 indicates a significant difference from UTP-stimulated cells.

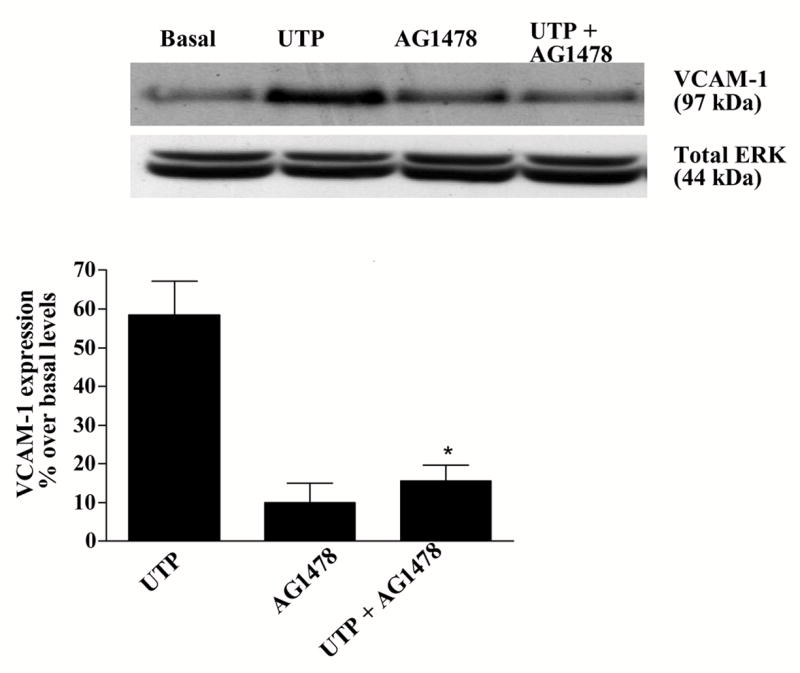

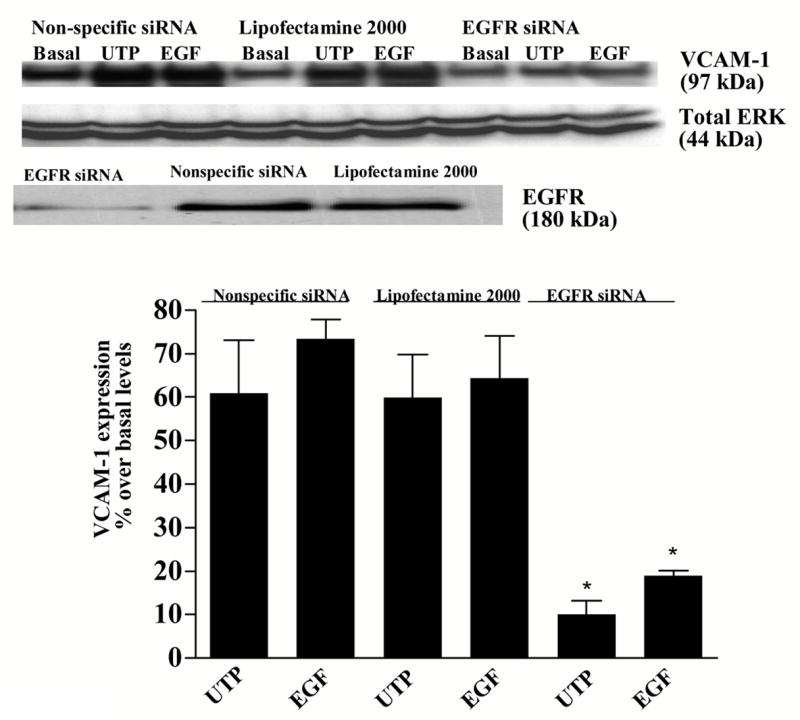

3.4. UTP-induced VCAM-1 expression in HSG cells and lymphocyte binding is dependent on EGFR activation

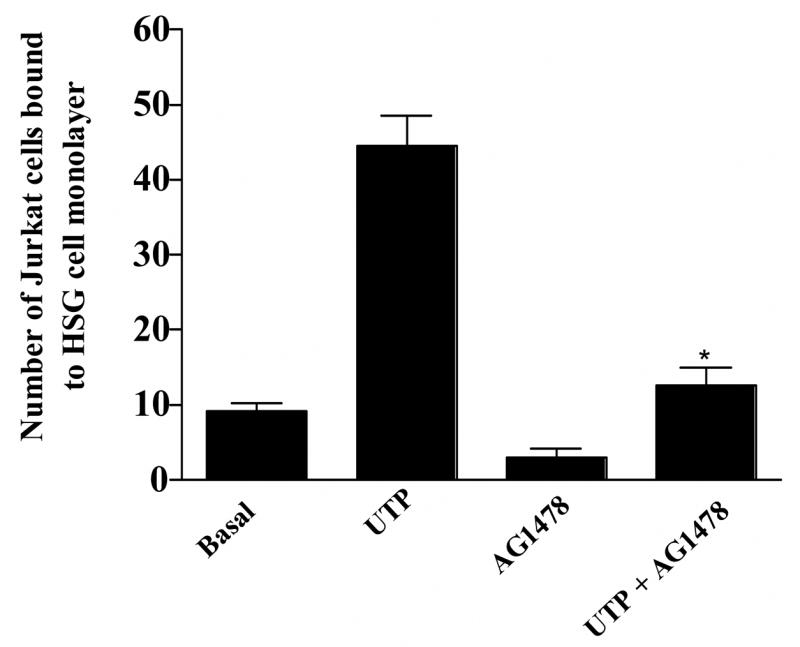

We have shown previously that P2Y2Rs induce VCAM-1 expression in vascular endothelial cells (Seye et al., 2003) via activation of VEGFR-2 (Seye et al., 2004), a response inhibited by the selective VEGFR-2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor SU1498 (Seye et al., 2004). Since HSG cells do not express VEGFR (data not shown), we examined whether other growth factor receptors regulate Jurkat lymphocyte adherence to HSG cells in response to P2Y2R activation. UTP-induced expression of VCAM-1 in HSG cells was inhibited by the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 (Fig. 7) and by EGFR siRNA (Fig. 8). Additionally, lymphocyte binding to UTP-stimulated HSG cells was prevented by the tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 (Fig. 9). These data suggest that EGFR tyrosine kinase activity is required for P2Y2R mediated up-regulation of VCAM-1 in HSG cells and promotes lymphocyte binding, responses relevant to the pathogenesis of SS.

Figure 7.

P2Y2R-mediated VCAM-1 expression in HSG cells is decreased by the selective EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor tyrphostin (AG1479). HSG cells were pre-incubated for 30 min with or without AG1479 (10 μM) and then incubated in the absence or presence of UTP (100 μM) for 6 h at 37°C. Protein extracts from HSG cells were subjected to Western blot analysis as described in “Methods”. Data represent the means ± S.E.M. of results from three experiments, where *p<0.05 indicates a significant difference from UTP-stimulated cells. Results from a representative experiment are shown at the top of the figure.

Figure 8.

P2Y2R-mediated VCAM-1 expression in HSG cells is decreased by EGFR siRNA. HSG cells were transfected with SMARTpool small interfering EGFR RNA (100 nM) using lipofectamine 2000, as described in “Methods”. Cells transfected with non-specific siRNA or treated with lipofectamine alone served as controls. Transfected cells were incubated in the absence or presence of UTP (100 μM) for 6 h at 37°C. VCAM-1 and EGFR expression was detected by Western blot analysis as described in “Methods”. Data represent the means ± S.E.M. of results from three experiments, where *p<0.05 indicates a significant difference from cells transfected with non-specific siRNA. Results from a representative experiment are shown at the top of the figure.

Figure 9.

Lymphocyte binding to UTP-stimulated HSG cell monolayers is inhibited by the selective EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor tyrphostin (AG1479). HSG cells were incubated with or without AG1479 (10 μM) and then incubated in the absence or presence of UTP (100 μM) for 6 h at 37°C. Binding of PKH2-labeled Jurkat lymphocytic cells to HSG cell monolayers was determined as described in “Methods”. Data represent the means ± S.E.M. of results from three experiments, where *p<0.05 indicates a significant difference from UTP-stimulated cells.

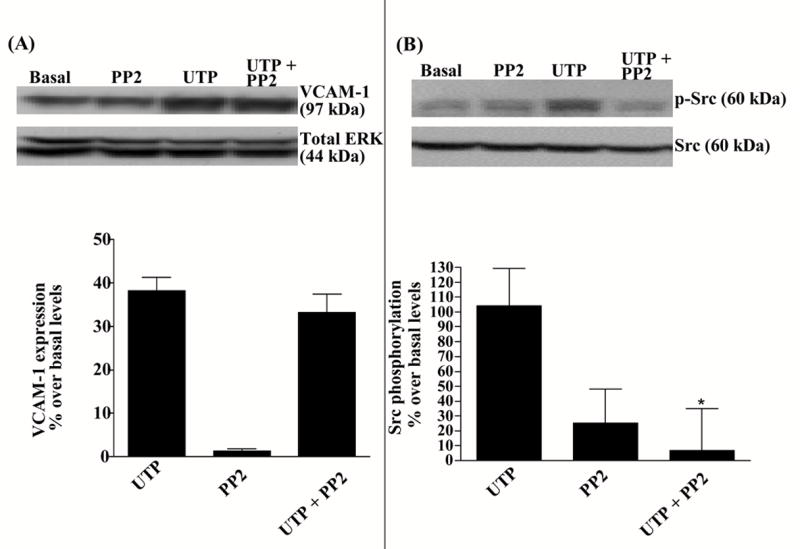

3.5. UTP-induced VCAM-1 expression is independent of Src tyrosine kinase activity

Our previous studies showed that inhibition of Src tyrosine kinase activity abolished P2Y2R-mediated transactivation of VEGFR-2 and VCAM-1 expression in endothelial cells (Seye et al., 2004), raising the possibility that UTP-induced VCAM-1 expression in HSG cells also requires Src kinase. In contrast to endothelial cells, however, VCAM-1 expression induced by 100 μM UTP in HSG cells was not inhibited by PP2 (1 μM), a selective Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor (Fig. 10 panel A). However, this PP2 concentration inhibited UTP-induced Src phosphorylation in HSG cells (Fig. 10 panel B) suggesting that mechanisms independent of Src link P2Y2R and EGFR signaling pathways that regulate UTP-induced VCAM-1 expression in salivary gland cells.

Figure 10.

P2Y2R-mediated VCAM-1 expression is unaffected by PP2, a selective Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor. HSG cells were incubated for 30 min with or without the selective Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 μM) and then incubated in the absence or presence of UTP (100 μM) either for 6 h at 37°C for VCAM-1 expression analysis (panel A) or for 1 min at room temperature for Src phosphorylation analysis (panel B). Protein extracts from HSG cells were subjected to Western blot analysis as described in “Methods”. Data represent the means ± S.E.M. of results from three experiments, where * p<0.005 indicates a significant difference from UTP-stimulated cells (panel B). Results from representative experiments are shown at the top of the figure.

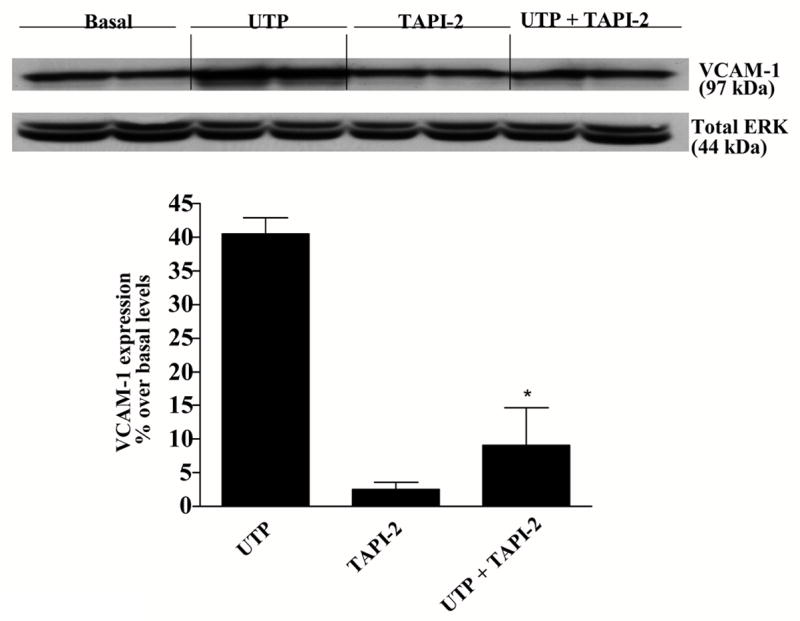

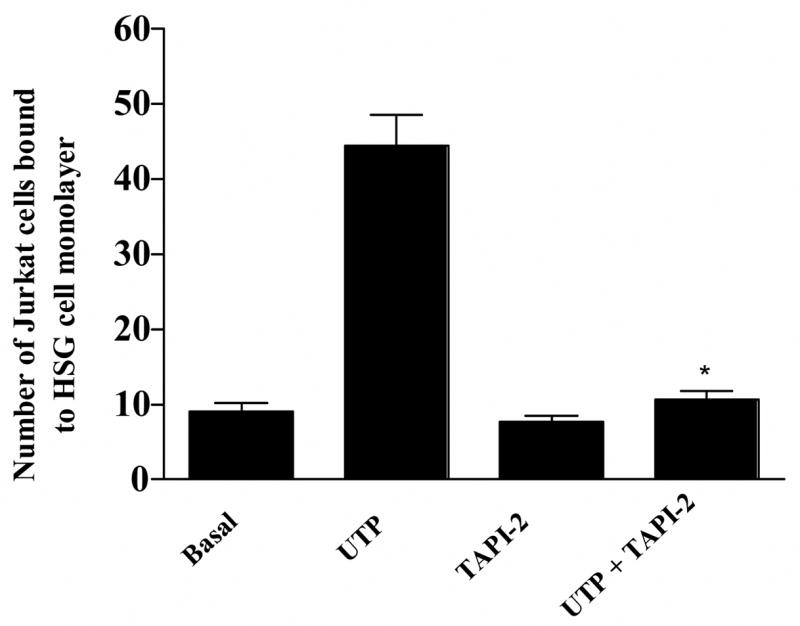

3.6. UTP-induced VCAM-1 expression in HSG cells and lymphocyte binding are dependent on metalloprotease activation

Many GPCRs are known to transactivate the EGFR through generation of EGFR ligands by activation of metalloproteases (Daub et al., 1997; Prenzel et al., 1999; Pierce et al., 2001), particularly metalloproteases of the adamalysin family (Sahin et al., 2004). We have previously reported that P2Y2R activation in 1321N1 astrocytoma cells enhances metalloprotease activity (Camden et al., 2005), and therefore we investigated the involvement of metalloproteases in P2Y2R-mediated VCAM-1 expression in HSG cells. TAPI-2, a selective inhibitor of ADAM17, inhibited both VCAM-1 expression (Fig. 11) and lymphocyte binding (Fig. 12) induced by UTP (100 μM) in HSG cell monolayers. These data suggest that P2Y2R-mediated activation of metalloproteases in HSG cells regulates increases in VCAM-1-dependent lymphocyte binding to HSG cells.

Figure 11.

P2Y2R-mediated VCAM-1 expression is decreased by the selective metalloprotease inhibitor, TAPI-2. HSG cells were incubated for 30 min with or without the selective metalloprotease inhibitor TAPI-2 (10 μM) and then incubated in the absence or presence of UTP (100 μM) for 6 h at 37°C. Protein extracts from HSG cells were subjected to Western blot analysis as described in “Methods”. Data represent the means ± S.E.M. of results from three experiments, where *p<0.05 indicates a significant difference from UTP-stimulated cells. Results from a representative experiment are shown at the top of the figure.

Figure 12.

Lymphocyte binding to UTP-stimulated HSG cell monolayers is inhibited by the selective metalloprotease inhibitor TAPI-2. HSG cells were incubated for 30 min with the selective metalloprotease inhibitor TAPI-2 (10 μM) and then incubated in the absence or presence of UTP (100 μM) for 6 h at 37°C. Binding of PKH2-labeled Jurkat lymphocytic cells to HSG cell monolayers was determined as described in “Methods”. Data represent the means ± S.E.M. of results from three experiments, where *p<0.05 indicates a significant difference from UTP-stimulated cells.

4. Discussion

The present study indicates that UTP stimulates an increase VCAM-1 expression via P2Y2R activation in human submandibular gland (HSG) ductal cells and in dispersed cell aggregates from rat SMG. Additionally, our results show that the P2Y2R-mediated increase in VCAM-1 expression promotes the adherence of human Jurkat lymphocytic cells to HSG cell monolayers. Previous studies have shown that the P2Y2R is up-regulated in response to damage or stress of salivary gland epithelium and in salivary glands of the NOD.B10 mouse model of SS (Turner et al., 1997; Ahn et al., 2000; Schrader et al., 2005) and, accordingly, the current studies demonstrate that a consequence of P2Y2R up-regulation in salivary epithelium in vivo is likely to be increased lymphocyte binding and infiltration in salivary gland leading to inflammation and secretory dysfunction. HSG cells have been shown to express functional P2Y2Rs (Yu and Turner, 1991), and both P2Y2R and P2Y6R mRNAs were detected in these cells (data not shown). However, the lack of a functional response in HSG cells to the P2Y6R agonist UDP (data not shown) and the inability of UTP to increase VCAM-1 expression after suppression of P2Y2R expression with siRNA (Fig. 4) strongly suggests that the P2Y2R is the only functional uridine nucleotide receptor expressed in HSG cells. Additionally, the inability of UTP to induce VCAM-1 expression in freshly dispersed rat SMG cell aggregates (0 h time point in Fig. 1) when P2Y2R mRNA is barely detectable (Turner et al., 1997) indicates that the P2Y2R must be up-regulated to increase VCAM-1 expression and lymphocyte binding in HSG cells P2Y2R-mediated activation also increases VCAM-1 expression in human coronary artery endothelial cells (Seye et al., 2003), suggesting that this pathway may represent a common mechanism for promoting immune cell-associated inflammatory responses in various tissues.

The extracellular nucleotides ATP and UTP promote cell-cell adhesion in monocytes/macrophages and neutrophil and monocyte adherence to endothelial cell monolayers (Ventura and Thomopoulos, 1995; Parker et al., 1996; Seye et al., 2003), supporting the notion that released ATP and UTP induce endothelial cell activation by autocrine/paracrine mechanisms. Sources of extracellular nucleotides include aggregating platelets, degranulating macrophages, excitatory neurons, injured cells, and cells undergoing mechanical or oxidative stress (Pedersen et al., 1999; Bodin and Burnstock, 2001; Weisman et al., 2005). Release of nucleotides has been proposed to occur by exocytosis of ATP/UTP-containing vesicles, facilitated diffusion by putative ABC transporters, cytoplasmic leakage, and electrodiffusional movements through ATP/nucleotide channels (Zimmermann and Braun, 1996). Under pathological conditions, it is clear that nucleotides are released from the cytoplasm of injured or stressed cells and tissues in response to oxidative stress, ischemia, hypoxia or mechanical stretch (Bergfeld and Forrester, 1992; Ciccarelli et al., 1999; Pedersen et al., 1999; Bodin and Burnstock, 2001; Ostrom et al., 2001), whereupon they activate a variety of cellular responses including cell adhesion, neurotransmission, apoptosis, and cell growth (Wilden et al., 1998; Bodin and Burnstock, 2001; Chaulet et al., 2001; Ciccarelli et al., 2001; Coutinho-Silva et al., 2003; Weisman et al., 2005). In salivary glands, P2 nucleotide receptors are thought to be activated by neuronally released ATP, co-packaged with various neurotransmitters (Brown et al., 2004). Additionally, it has been proposed that ATP released from acinar cells through exocytosis of zymogen granules or transit through gap junction hemi-channels, acts in a paracrine manner on neighboring acinar cells (Brown et al., 2004). The G protein-coupled P2Y2R regulates some cellular responses to nucleotides via Gαq/11 protein-dependent stimulation of phospholipase C, an enzyme that regulates IP3-dependent intracellular calcium mobilization and protein kinase C activation (Boarder et al., 1995; Weisman et al., 1996). Moreover, our studies indicate that the P2Y2R contains two SH3 binding domains (PXXP motifs) in its intracellular C-terminal domain that mediate the binding of Src and the Src-dependent transactivation of growth factor receptors in human 1321N1 astrocytoma cells (Liu et al., 2004). In human coronary artery endothelial cells, the P2Y2R also mediates the Src-dependent transactivation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor type 2 (VEGFR-2) leading to increased VCAM-1 expression (Seye et al., 2003; Seye et al., 2004). The current study suggests that the P2Y2R regulates VCAM-1 expression and lymphocyte binding in HSG cells via transactivation of the EGFR (Figs. 7–9). However, this pathway is apparently Src-independent, since the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 did not affect P2Y2R-mediated VCAM-1 up-regulation (Fig. 10 panel A), although PP2 prevents P2Y2R-mediated Src phosphorylation (Fig. 10 panel B). Receptors for lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), endothelin (ET-1), thrombin, bombesin, muscarine (M1R), and the α2 adrenergic agonist UK14304 are known to transactivate EGF receptors through activation of metalloproteases that catalyze the shedding of the EGFR ligand, HB-EGF, leading to the stimulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (Daub et al., 1997; Prenzel et al., 1999; Kalmes et al., 2000; Pierce et al., 2001). In HSG cells (Figs. 11 and 12), we have shown that UTP-induced VCAM-1 expression and lymphocyte binding is inhibited by TAPI-2, a selective inhibitor of ADAM17, a member of the adamalysin family of metalloproteases (ADAMs) implicated in GPCR-mediated tumor cell migration (Schafer et al., 2004). ADAMs can mediate the shedding of a variety of EGFR ligands, including EGF, HB-EGF, TGFα, amphiregulin, epiregulin, and betacellulin (Sahin et al., 2004). Moreover, ADAM17 can release the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα that has been shown to induce apoptosis in salivary gland cells (Matsumura et al., 2000) and lymphocyte adherence to HSG cells (Fig. 5). Since TNFα and UTP have similar effects on lymphocyte adherence to HSG cells, it is tantalizing to propose that UTP stimulates TNFα release in HSG cells via activation of metalloproteases. Recently, we found that the human P2Y2R expressed in human 1321N1 astrocytoma cells mediates the proprotein convertase furin-dependent activation of ADAM17 leading to the proteolytic cleavage of the transmembrane amyloid precursor protein and the release of the neuroprotective fragment sAPPα (Camden et al., 2005). Further studies are needed to determine which EGFR ligands are released by P2Y2R activation in HSG cells.

The ability of P2Y2R activation to up-regulate VCAM-1 expression may be critical to immune cell infiltration and inflammatory responses in a variety of tissues. VCAM-1 is a transmembrane adhesion molecule that is expressed on the surface of endothelial cells (Osborn et al., 1989), fibroblasts derived from a variety of tissues (Morales-Ducret et al., 1992; Borrello and Phipps, 1996; Gao and Issekutz, 1996), follicular dendritic cells (Koopman et al., 1994), bone marrow stromal cells (Miyake et al., 1991), airway epithelial cells (Atsuta et al., 1999), thymic epithelium (Salomon et al., 1997), and salivary epithelium (Aziz et al., 1992; Saito et al., 1993; Tsunawaki et al., 2002). Several studies have documented that pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 (Osborn et al., 1989), TNFα (Osborn et al., 1989; Burke-Gaffney and Hellewell, 1996; Atsuta et al., 1997; Spoelstra et al., 1999; Tu et al., 2001; Woo et al., 2005), IFNγ (De Caterina et al., 2001), and interleukin-4 (Spoelstra et al., 1999) markedly enhance the expression of VCAM-1 in endothelial and epithelial cells. Since P2Y2R activation also can stimulate the expression of VCAM-1 in endothelial cells (Seye et al., 2004), dispersed rat SMG cell aggregates (Figs. 1 and 2) and HSG cells (Fig. 3), it is reasonable to propose that cytokine-like nucleotides also play a pro-inflammatory role in VCAM-1-dependent monocyte (Seye et al., 2003; Seye et al., 2004) and lymphocyte (Fig. 5) binding to endothelial and epithelial cells. These findings encourage further investigations to evaluate the contribution of P2Y2Rs to a variety of inflammatory diseases that have been linked to VCAM-1 expression, including inflammatory bowel disease (Jones et al., 1995; Rijcken et al., 2002), rheumatoid arthritis (Morales-Ducret et al., 1992; Kriegsmann et al., 1995; Ilgner and Stiehl, 2002) and Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) (Aziz et al., 1992; Edwards et al., 1993; Saito et al., 1993; Tsunawaki et al., 2002). Interestingly, the VCAM-1 ligand VLA-4 is expressed in a majority of infiltrating T lymphocytes in biopsies of minor salivary glands from patients with SS (Edwards et al., 1993; Saito et al., 1993), suggesting a mechanism whereby lymphocytes bind to VCAM-1 up-regulated in response to P2Y2R activation in salivary gland cells. Furthermore, VCAM-1 immobilized on beads with receptor globulin can induce both the expression of cell surface IL-2 receptor (CD25) and the secretion of IL-2 in activated human CD4+ T cells (Damle and Aruffo, 1991), suggesting that binding of lymphocytes to salivary epithelial VCAM-1 promotes the release of pro-inflammatory mediators that potentiate inflammation in SS.

In conclusion, the results presented indicate that activation of P2Y2Rs in the human submandibular (HSG) ductal cell line promotes the up-regulation of VCAM-1 to enhance the binding of lymphocytes to HSG cell monolayers, a response that may be relevant to lymphocyte-mediated chronic inflammation in salivary gland diseases, such as Sjögren’s syndrome (Fox and Speight, 1996; Kassan and Moutsopoulos, 2004; Ramos-Casals and Font, 2005; Garcia-Carrasco et al., 2006). Furthermore, we have determined a role for metalloproteases and EGFR in the P2Y2R-mediated regulation of VCAM-1 expression and lymphocyte binding in HSG cells, and these studies suggest pharmacological approaches to minimize nucleotide-induced inflammation in the salivary gland by targeting the P2Y2R and its signaling pathways.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH-NIDCR grants R01 DE017591-01, R01 DE07389-19, K08 DE017633-01 and a Sjögren’s Syndrome Foundation Research Grant.

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular free calcium concentration

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

EGF receptor

- ERK

extracellular signal regulated kinase

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- HSG cells

human submandibular gland ductal cells

- IFNγ

interferon-γ

- LFA-1

lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1

- Opti-MEM

reduced-serum medium

- P2Y2R

P2Y2 receptor

- SMG

submandibular gland

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SS

Sjögren’s syndrome

- TAPI-2

TNFα protease inhibitor-2

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor-α

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VLA-4

very late antigen-4

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahn JS, Camden JM, Schrader AM, Redman RS, Turner JT. Reversible regulation of P2Y2 nucleotide receptor expression in the duct-ligated rat submandibular gland. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C286–94. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.2.C286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atsuta J, Plitt J, Bochner BS, Schleimer RP. Inhibition of VCAM-1 expression in human bronchial epithelial cells by glucocorticoids. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:643–50. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.4.3265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atsuta J, Sterbinsky SA, Plitt J, Schwiebert LM, Bochner BS, Schleimer RP. Phenotyping and cytokine regulation of the BEAS-2B human bronchial epithelial cell: demonstration of inducible expression of the adhesion molecules VCAM-1 and ICAM-1. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:571–82. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.5.2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz KE, McCluskey PJ, Montanaro A, Wakefield D. Vascular endothelium and lymphocyte adhesion molecules in minor salivary glands of patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1992;37:39–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergfeld GR, Forrester T. Release of ATP from human erythrocytes in response to a brief period of hypoxia and hypercapnia. Cardiovasc Res. 1992;26:40–7. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boarder MR, Weisman GA, Turner JT, Wilkinson GF. G protein-coupled P2 purinoceptors: from molecular biology to functional responses. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1995;16:133–9. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodin P, Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling: ATP release. Neurochem Res. 2001;26:959–69. doi: 10.1023/a:1012388618693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrello MA, Phipps RP. Differential Thy-1 expression by splenic fibroblasts defines functionally distinct subsets. Cell Immunol. 1996;173:198–206. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1996.0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Bruce JI, Straub SV, Yule DI. cAMP potentiates ATP-evoked calcium signaling in human parotid acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39485–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke-Gaffney A, Hellewell PG. TNFα-induced ICAM-1 expression in human vascular endothelial and lung epithelial cells: modulation by tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:1149–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camden JM, Schrader AM, Camden RE, Gonzalez FA, Erb L, Seye CI, Weisman GA. P2Y2 nucleotide receptors enhance α-secretase-dependent amyloid precursor protein processing. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18696–702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaulet H, Desgranges C, Renault MA, Dupuch F, Ezan G, Peiretti F, Loirand G, Pacaud P, Gadeau AP. Extracellular nucleotides induce arterial smooth muscle cell migration via osteopontin. Circ Res. 2001;89:772–8. doi: 10.1161/hh2101.098617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli R, Ballerini P, Sabatino G, Rathbone MP, D’Onofrio M, Caciagli F, Di Iorio P. Involvement of astrocytes in purine-mediated reparative processes in the brain. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2001;19:395–414. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(00)00084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli R, Di Iorio P, Giuliani P, D’Alimonte I, Ballerini P, Caciagli F, Rathbone MP. Rat cultured astrocytes release guanine-based purines in basal conditions and after hypoxia/hypoglycemia. Glia. 1999;25:93–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho-Silva R, Parsons M, Robson T, Lincoln J, Burnstock G. P2X and P2Y purinoceptor expression in pancreas from streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;204:141–54. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(03)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damle NK, Aruffo A. Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 induces T-cell antigen receptor-dependent activation of CD4+T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:6403–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.15.6403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daub H, Wallasch C, Lankenau A, Herrlich A, Ullrich A. Signal characteristics of G protein-transactivated EGF receptor. Embo J. 1997;16:7032–44. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Caterina R, Bourcier T, Laufs U, La Fata V, Lazzerini G, Neish AS, Libby P, Liao JK. Induction of endothelial-leukocyte interaction by IFNγ requires coactivation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:227–32. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JC, Wilkinson LS, Speight P, Isenberg DA. Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 and α4β1 integrins in lymphocyte aggregates in Sjögren’s syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52:806–11. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.11.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PC, Speight PM. Current concepts of autoimmune exocrinopathy: immunologic mechanisms in the salivary pathology of Sjögren’s syndrome. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1996;7:144–58. doi: 10.1177/10454411960070020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RI. Sjögren’s syndrome: immunobiology of exocrine gland dysfunction. Adv Dent Res. 1996;10:35–40. doi: 10.1177/08959374960100010601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao JX, Issekutz AC. Expression of VCAM-1 and VLA-4 dependent T-lymphocyte adhesion to dermal fibroblasts stimulated with proinflammatory cytokines. Immunology. 1996;89:375–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-750.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Carrasco M, Fuentes-Alexandro S, Escarcega RO, Salgado G, Riebeling C, Cervera R. Pathophysiology of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Arch Med Res. 2006;37:921–32. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrad RC, Otero MA, Erb L, Theiss PM, Clarke LL, Gonzalez FA, Turner JT, Weisman GA. Structural basis of agonist-induced desensitization and sequestration of the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor. Consequences of truncation of the C terminus. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29437–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilgner S, Stiehl P. Strong LFA-1 and VCAM-1 expression in histological type II of rheumatoid arthritis. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-legrand) 2002;48 Online Pub, OL243–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SC, Banks RE, Haidar A, Gearing AJ, Hemingway IK, Ibbotson SH, Dixon MF, Axon AT. Adhesion molecules in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1995;36:724–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.5.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson R, Moen K, Vestrheim D, Szodoray P. Current issues in Sjögren’s syndrome. Oral Dis. 2002;8:130–40. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.02846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmes A, Vesti BR, Daum G, Abraham JA, Clowes AW. Heparin blockade of thrombin-induced smooth muscle cell migration involves inhibition of epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor transactivation by heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor. Circ Res. 2000;87:92–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.2.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassan SS, Moutsopoulos HM. Clinical manifestations and early diagnosis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1275–84. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.12.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman G, Keehnen RM, Lindhout E, Newman W, Shimizu Y, van Seventer GA, de Groot C, Pals ST. Adhesion through the LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18)-ICAM-1 (CD54) and the VLA-4 (CD49d)-VCAM-1 (CD106) pathways prevents apoptosis of germinal center B cells. J Immunol. 1994;152:3760–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegsmann J, Keyszer GM, Geiler T, Brauer R, Gay RE, Gay S. Expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 mRNA and protein in rheumatoid synovium demonstrated by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry. Lab Invest. 1995;72:209–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Liao Z, Camden J, Griffin KD, Garrad RC, Santiago-Perez LI, Gonzalez FA, Seye CI, Weisman GA, Erb L. Src homology 3 binding sites in the P2Y2 nucleotide receptor interact with Src and regulate activities of Src, proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2, and growth factor receptors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8212–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312230200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto I, Tsubota K, Satake Y, Kita Y, Matsumura R, Murata H, Namekawa T, Nishioka K, Iwamoto I, Saitoh Y, Sumida T. Common T cell receptor clonotype in lacrimal glands and labial salivary glands from patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1969–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI118629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura R, Umemiya K, Goto T, Nakazawa T, Ochiai K, Kagami M, Tomioka H, Tanabe E, Sugiyama T, Sueishi M. IFNγ and TNFα induce Fas expression and anti-Fas mediated apoptosis in a salivary ductal cell line. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18:311–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake K, Medina K, Ishihara K, Kimoto M, Auerbach R, Kincade PW. A VCAM-like adhesion molecule on murine bone marrow stromal cells mediates binding of lymphocyte precursors in culture. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:557–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.3.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Ducret J, Wayner E, Elices MJ, Alvaro-Gracia JM, Zvaifler NJ, Firestein GS. α4/β1 integrin (VLA-4) ligands in arthritis. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in synovium and on fibroblast-like synoviocytes. J Immunol. 1992;149:1424–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn L, Hession C, Tizard R, Vassallo C, Luhowskyj S, Chi-Rosso G, Lobb R. Direct expression cloning of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, a cytokine-induced endothelial protein that binds to lymphocytes. Cell. 1989;59:1203–11. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90775-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom RS, Gregorian C, Drenan RM, Gabot K, Rana BK, Insel PA. Key role for constitutive cyclooxygenase-2 of MDCK cells in basal signaling and response to released ATP. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C524–31. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.2.C524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker AL, Likar LL, Dawicki DD, Rounds S. Mechanism of ATP-induced leukocyte adherence to cultured pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:L695–703. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.5.L695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr CE, Sullivan DM, Paradiso AM, Lazarowski ER, Burch LH, Olsen JC, Erb L, Weisman GA, Boucher RC, Turner JT. Cloning and expression of a human P2U nucleotide receptor, a target for cystic fibrosis pharmacotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3275–79. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen S, Pedersen SF, Nilius B, Lambert IH, Hoffmann EK. Mechanical stress induces release of ATP from Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1416:271–84. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce KL, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. New mechanisms in heptahelical receptor signaling to mitogen activated protein kinase cascades. Oncogene. 2001;20:1532–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenzel N, Zwick E, Daub H, Leserer M, Abraham R, Wallasch C, Ullrich A. EGF receptor transactivation by G-protein-coupled receptors requires metalloproteinase cleavage of proHB-EGF. Nature. 1999;402:884–8. doi: 10.1038/47260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Casals M, Font J. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome: current and emergent aetiopathogenic concepts. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:1354–67. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijcken E, Krieglstein CF, Anthoni C, Laukoetter MG, Mennigen R, Spiegel HU, Senninger N, Bennett CF, Schuermann G. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 antisense oligonucleotides attenuate in vivo leucocyte adherence and inflammation in rat inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2002;51:529–35. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.4.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahin U, Weskamp G, Kelly K, Zhou HM, Higashiyama S, Peschon J, Hartmann D, Saftig P, Blobel CP. Distinct roles for ADAM10 and ADAM17 in ectodomain shedding of six EGFR ligands. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:769–79. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito I, Terauchi K, Shimuta M, Nishiimura S, Yoshino K, Takeuchi T, Tsubota K, Miyasaka N. Expression of cell adhesion molecules in the salivary and lacrimal glands of Sjögren’s syndrome. J Clin Lab Anal. 1993;7:180–7. doi: 10.1002/jcla.1860070309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon DR, Crisa L, Mojcik CF, Ishii JK, Klier G, Shevach EM. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 is expressed by cortical thymic epithelial cells and mediates thymocyte adhesion. Implications for the function of α4β1 (VLA4) integrin in T-cell development. Blood. 1997;89:2461–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer B, Marg B, Gschwind A, Ullrich A. Distinct ADAM metalloproteinases regulate G protein-coupled receptor-induced cell proliferation and survival. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47929–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400129200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader AM, Camden JM, Weisman GA. P2Y2 nucleotide receptor up-regulation in submandibular gland cells from the NOD.B10 mouse model of Sjögren’s syndrome. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:533–40. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seye CI, Yu N, Gonzalez FA, Erb L, Weisman GA. The P2Y2 nucleotide receptor mediates vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression through interaction with VEGF receptor-2 (KDR/Flk-1) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35679–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401799200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seye CI, Yu N, Jain R, Kong Q, Minor T, Newton J, Erb L, Gonzalez FA, Weisman GA. The P2Y2 nucleotide receptor mediates UTP-induced vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in coronary artery endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24960–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoelstra FM, Postma DS, Hovenga H, Noordhoek JA, Kauffman HF. Interferon γ and interleukin-4 differentially regulate ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression on human lung fibroblasts. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:759–66. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d06.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Clair EW, Angellilo JC, Singer KH. Expression of cell-adhesion molecules in the salivary gland microenvironment of Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:62–6. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunawaki S, Nakamura S, Ohyama Y, Sasaki M, Ikebe-Hiroki A, Hiraki A, Kadena T, Kawamura E, Kumamaru W, Shinohara M, Shirasuna K. Possible function of salivary gland epithelial cells as nonprofessional antigen-presenting cells in the development of Sjögren’s syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1884–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z, Kelley VR, Collins T, Lee FS. I kappa B kinase is critical for TNFα-induced VCAM-1 gene expression in renal tubular epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:6839–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JT, James-Kracke MR, Camden JM. Regulation of the neurotensin receptor and intracellular calcium mobilization in HT29 cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;253:1049–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JT, Redman RS, Camden JM, Landon LA, Quissell DO. A rat parotid gland cell line, Par-C10, exhibits neurotransmitter-regulated transepithelial anion secretion. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:C367–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JT, Weisman GA, Camden JM. Upregulation of P2Y2 nucleotide receptors in rat salivary gland cells during short-term culture. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1100–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.3.C1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura MA, Thomopoulos P. ADP and ATP activate distinct signaling pathways in human promonocytic U-937 cells differentiated with 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:104–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, Moutsopoulos HM, Alexander EL, Carsons SE, Daniels TE, Fox PC, Fox RI, Kassan SS, Pillemer SR, Talal N, Weisman MH. Classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:554–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.6.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman GA, Turner JT, Fedan JS. Structure and function of P2 purinocepters. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisman GA, Wang M, Kong Q, Chorna NE, Neary JT, Sun GY, Gonzalez FA, Seye CI, Erb L. Molecular determinants of P2Y2 nucleotide receptor function: implications for proliferative and inflammatory pathways in astrocytes. Mol Neurobiol. 2005;31:169–83. doi: 10.1385/MN:31:1-3:169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilden PA, Agazie YM, Kaufman R, Halenda SP. ATP-stimulated smooth muscle cell proliferation requires independent ERK and PI3K signaling pathways. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H1209–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.4.H1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo CH, Lim JH, Kim JH. VCAM-1 up-regulation via PKCδ-p38 kinase-linked cascade mediates the TNFα-induced leukocyte adhesion and emigration in the lung airway epithelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L307–16. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00105.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthou G, Tapinos NI, Polihronis M, Nezis IP, Margaritis LH, Moutsopoulos HM. CD4+ cytotoxic and dendritic cells in the immunopathologic lesion of Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;118:154–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu HX, Turner JT. Functional studies in the human submandibular duct cell line, HSG-PA, suggest a second salivary gland receptor subtype for nucleotides. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;259:1344–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann H, Braun N. Extracellular metabolism of nucleotides in the nervous system. J Auton Pharmacol. 1996;16:397–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1996.tb00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumla A, Mathur M, Stewart J, Wilkinson L, Isenberg D. T cell receptor expression in Sjögren’s syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 1991;50:691–3. doi: 10.1136/ard.50.10.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]