Abstract

The first events of the development of any embryo are under maternal control until the zygotic genome becomes activated. In the mouse embryo, the major wave of transcription activation occurs at the 2-cell stage, but transcription starts already at the zygote (1-cell) stage. Very little is known about the molecules involved in this process. We show that the transcription intermediary factor 1 α (TIF1α) is involved in modulating gene expression during the first wave of transcription activation. At the onset of genome activation, TIF1α translocates from the cytoplasm into the pronuclei to sites of active transcription. These sites are enriched with the chromatin remodelers BRG-1 and SNF2H. When we ablate TIF1α through either RNA interference (RNAi) or microinjection of specific antibodies into zygotes, most of the embryos arrest their development at the 2–4-cell stage transition. The ablation of TIF1α leads to mislocalization of RNA polymerase II and the chromatin remodelers SNF2H and BRG-1. Using a chromatin immunoprecipitation cloning approach, we identify genes that are regulated by TIF1α in the zygote and find that transcription of these genes is misregulated upon TIF1α ablation. We further show that the expression of some of these genes is dependent on SNF2H and that RNAi for SNF2H compromises development, suggesting that TIF1α mediates activation of gene expression in the zygote via SNF2H. These studies indicate that TIF1α is a factor that modulates the expression of a set of genes during the first wave of genome activation in the mouse embryo.

Introduction

After germinal vesicle (GV) breakdown, the fully grown oocyte is transcriptionally silent (Bachvarova, 1985). After fertilization, chromatin remodeling has been proposed to provide a window of opportunity for transcription factors to bind the regulatory sequences of genes that must be activated for development to proceed (Ma et al., 2001; Morgan et al., 2005). Concomitantly, a transcriptionally repressed state would be necessary to prevent promiscuous gene expression as a result of a “general permissiveness” of the genome (for reviews see Thompson et al., 1998; Schultz, 2002). In the mouse, two phases of transcriptional activation lead to the transition from maternal to zygotic control of gene expression (Schultz, 2002). The major and most studied wave of activation is the second one, which begins at the late 2-cell stage. However, less is known about the first wave, which occurs in the pronuclei of the zygote and represents 40% of the transcriptional levels observed at the 2-cell stage (Aoki et al., 1997; Bouniol-Baly et al., 1997; Hamatani et al., 2004).

Transcription intermediary factor (TIF) 1 α (Trim24) was first identified as a transcriptional regulator of nuclear receptors and has been shown to interact with numerous proteins involved in chromatin structure (Le Douarin et al., 1995, 1996; Fraser et al., 1998; Nielsen et al., 1999; Remboutsika et al., 2002; Germain-Desprez et al., 2003). TIF1α is one of four TIFs described in mammals that belong to the tripartite motif superfamily of proteins (Le Douarin et al., 1995, 1996; Venturini et al., 1999; Khetchoumian et al., 2004). TIF1β (Trim28) is required for the proper specification of the anteroposterior axis in the mouse (Cammas et al., 2000). Little is known about the biological function of TIF1α, and its expression pattern is only known at late stages of postimplantation development (Niederreither et al., 1999). Here, we have characterized the role of TIF1α in early mouse embryogenesis. We show that TIF1α acts as a modulator of the transcriptional state of a particular set of genes during the first wave of genome activation and that ablation of TIF1α compromises development.

Results

TIF1α expression is gradually restricted to the inner cells of cleavage stage embryos, and the protein translocates into the pronucleus at the onset of genome activation

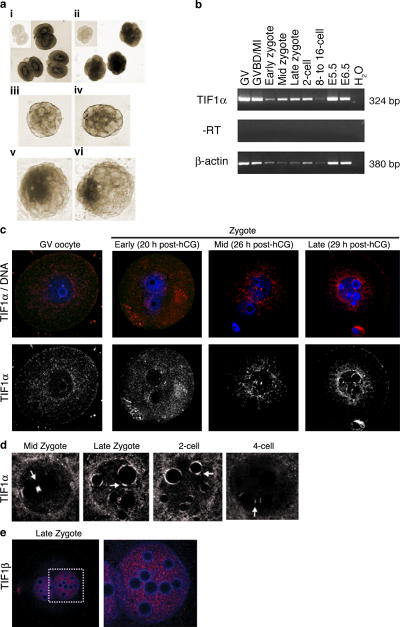

We first analyzed the expression pattern of Tif1α in oocytes and throughout preimplantation development by in situ hybridization and RT-PCR. Tif1α was expressed from the GV stage oocyte to the blastocyst (Fig. 1, a and b). Initially, Tif1α transcripts were present in all blastomeres, but as development progressed, Tif1α transcripts became restricted to the inner cells of the embryo (Fig. 1 a). This became evident at the 16-cell stage, and when the blastocyst formed, Tif1α expression was restricted to the inner cell mass (ICM).

Figure 1.

TIF1α expression becomes gradually restricted in the early embryo, and the protein translocates into the pronucleus around the onset of genome activation. (a) In situ hybridization for TIF1α of 2-cell (i), 5–8-cell (ii), 16-cell (iii), and 32-cell embryos (iv) and expanding (v) and late (vi) blastocyst. The insets within panels i and ii show embryos at the 2- and 8-cell stages, respectively, processed with the sense probe. Expression of TIF1α is enriched in the inner cells of the mouse embryo from the 16-cell stage onward and is restricted to the ICM of the blastocyst. Shown are representative embryos of at least 20 embryos and two independent experiments for each stage. (b) RT-PCR analysis for TIF1α of mouse oocytes and embryos at the specified stages. GVBD/MI, GV breakdown and metaphase I arrested oocytes; E, embryonic day. At least five embryos per stage were analyzed. Note that the mRNA levels of actin are known to decline after oocyte maturation (Temeles et al., 1994) and should only be considered as control of amplification and not for quantification purposes. (c) Immunolocalization of TIF1α protein (red) in GV oocyte and early, mid, and late zygote at 2- and 4-cell stages. All samples were analyzed under comparable confocal imaging settings. In all panels, DNA was stained with TOTO-3 (blue). Shown are representative embryos of at least 20 embryos analyzed per stage from at least three independent experiments. Below the merge panel, the red channel (TIF1α) is shown as grayscale. (d) Higher magnifications of the pronuclei of mid and late zygotes and the nuclei of 2- and 4-cell stage embryos. Arrows indicate the dense accumulation of TIF1α. Albeit weaker, association of TIF1α with NLBs persists in the 2- and 4-cell stage embryos. The pronuclei shown in higher magnification are male. (e) TIF1β (red) exhibits a diffuse pattern of localization in the two pronuclei of the mouse zygotes. The right panel is a higher magnification of the region (male pronucleus) marked with the white square in the left panel. DNA is shown in blue.

At the GV stage, TIF1α protein was detected in the oocyte cytoplasm (Fig. 1 c). Shortly after fertilization, TIF1α remained predominantly cytoplasmic, but it moved to both pronuclei at the mid and late zygote stages. TIF1α became localized to discrete regions associated with the nucleolar-like bodies (NLBs), which are a compact mass of DNA surrounded by a perinucleolar chromatin ring that cause the characteristic pattern of DNA staining visible at these stages (Fig. 1, c and d; Kopecny et al., 1995). This distribution was observed in both male and female pronuclei, although in some cases (11 of 32 zygotes analyzed), TIF1α was only seen in the male pronucleus, most likely reflecting the fact that the male pronucleus undergoes transcriptional activation earlier (Bouniol et al., 1995). TIF1α remained associated with NLBs through the 2-cell stage and, although less prominent, throughout the 4-cell stage. This pattern of localization in dense spots was specific for TIF1α because TIF1β was uniformly distributed throughout the nucleoplasm of the two pronuclei (Fig. 1 e).

The time when we observed TIF1α translocation into the pronuclei coincides with the time when chromatin remodelers and transcription machinery factors, such as Brahma-related gene 1 (BRG-1; SMARCA4), Brahma (BRM; SMARCA2), and high mobility group box 1 (HMGB-1), translocate into the pronuclei (Bellier et al., 1997; Legouy et al., 1998; Beaujean et al., 2000). This is also associated with the appearance of the hyperphosphorylated (active) form of the RNA polII (Bellier et al., 1997), concomitant with the activation of transcription of the embryonic genome (Bouniol et al., 1995). Thus, the change of TIF1α localization from the cytoplasm to the pronuclei occurs at the time of embryo genome activation.

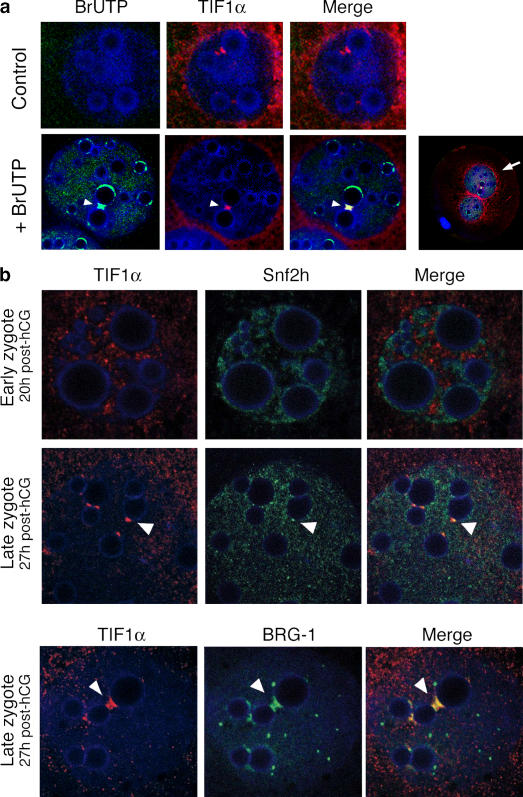

Sites enriched with TIF1α colocalize with transcription foci and are enriched with chromatin remodelers

To examine whether TIF1α is associated with regions of active transcription in the embryo, we assayed whether the sites of 5-bromo UTP (BrUTP) incorporation in vivo colocalize with TIF1α in the zygote. BrUTP staining was detected throughout the pronuclear nucleoplasm of the zygote, and sites of higher BrUTP accumulation were observed in the periphery and the proximity of the NLBs (Fig. 2 a, +BrUTP; and Fig. S2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200603146/DC1). Immunostaining for TIF1α in BrUTP-injected zygotes revealed that TIF1α colocalized with some of these sites of greater BrUTP incorporation. Note, however, that not all of the BrUTP sites colocalized with TIF1α (Fig. 2 a). This data indicates that TIF1α is recruited to specific sites of RNA synthesis at the late zygote stage.

Figure 2.

TIF1α localizes to active sites of transcription enriched with chromatin remodelers in the late zygote. (a) Colocalization of TIF1α and incorporated BrUTP in the pronuclei of late zygotes. Embryos were analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy using an anti-TIF1α (red) and anti-BrdU (green) antibody. No staining with the BrdU antibody was detected in the controls (top). Arrowheads point to the sites where TIF1α colocalizes with BrUTP. A lower magnification of the same zygote is shown in the right panel, where the arrow points toward the male pronucleus. Shown are one of the pronuclei (male) of representative zygotes from two different experiments (n = 20). (b) Sites of TIF1α accumulation are enriched with SNF2H and BRG-1 around the onset of genome activation. Confocal laser images of embryos stained with TIF1α (red) and SNF2H (green, top and middle) or BRG-1 (green, bottom). Arrowheads in the merge panels point to the regions of accumulation of TIF1α. Shown is one of the pronuclei of representative zygotes at the indicated stages (n = 6). DNA was stained with TOTO-3 (blue) in all panels.

Because the fully grown oocyte is transcriptionally silent (Bachvarova, 1985), chromatin remodeling is expected to be required after fertilization to enable embryo genome activation. The TIFs are characterized by the presence of a bromodomain in the C terminus, and it is known that bromodomain-containing proteins can have a role in chromatin remodeling, gene repression, and gene activation (Agalioti et al., 2000; Schultz et al., 2001; Ladurner et al., 2003). This led us to examine whether TIF1α colocalizes with chromatin remodelers. We assayed whether the sites of TIF1α accumulation relate to the localization of the ATPase subunits of the mammalian types switching defective–sucrose nonfermenting (SWI–SNF) and Imitation of Switch (ISWI) remodeling complexes. SNF2H (SMARCA5) is the ATPase subunit of the mammalian ISWI complex (Lazzaro and Picketts, 2001). At the late zygote stage, SNF2H localized to small foci throughout the nucleoplasm of both pronuclei and to larger foci around the NLBs (Fig. 2 b). BRG-1 is the ATPase subunit of the mammalian SWI–SNF complex (Kwon et al., 1994). BRG-1 localized to bigger foci than those of SNF2H and displayed increased accumulation around the NLBs (Fig. 2 b). A similar distribution has been reported for BRG-1 in earlier zygotes (Legouy et al., 1998). As expected, TIF1α did not colocalize with SNF2H in early zygotes (Fig. 2 b, top). In contrast at the late zygote stage, we found that sites around the NLBs that were enriched with TIF1α were also enriched with both SNF2H and BRG-1 (Fig. 2 b, middle and bottom). Moreover, similar to the pattern of BrUTP incorporation, not all SNF2H and BRG-1 foci contained TIF1α. Thus, sites of accumulation of TIF1α are also enriched with chromatin remodelers in the late zygote stage.

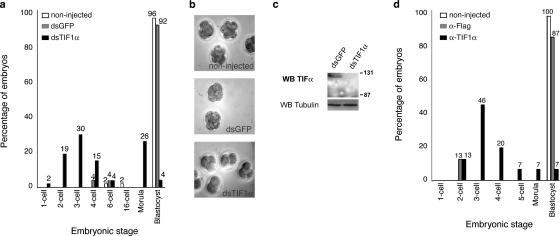

RNAi or injection of antibodies against TIF1α compromises early development

We next wished to assess the function of TIF1α at the beginning of development of the mouse embryo. To this end, we used two methods: RNAi and injection of antibodies. For RNAi, zygotes were microinjected with double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) for TIF1α at the fertilization cone stage. Injections of dsRNA for GFP as well as noninjected embryos were used as negative controls. We found that embryos injected with TIF1α dsRNA proceeded through the first cleavage and reached the 2-cell stage at the same time as the control embryos. However, although the control embryos developed normally to the blastocyst stage (noninjected, 96%, n = 85; dsGFP, 92%, n = 70; five independent experiments), the majority of the embryos injected with dsRNA for TIF1α arrested at the 2–4-cell stage (66%; n = 80; five independent experiments; Fig. 3, a and b). 19% of these embryos arrested at the 2-cell stage, 30% arrested at the 3-cell stage, and 15% developed only to the 4-cell stage (Fig. 3 a). To examine whether the down-regulation of TIF1α upon RNAi in zygotes was efficient, we analyzed embryos that had been injected with dsRNA for TIF1α or for GFP by Western blot, which showed that TIF1α protein was efficiently knocked down (Fig. 3 c). We also verified that injection of dsRNA for TIF1α was specific: it did not result in the reduction of TIF1β, E-cadherin, or β-actin mRNA levels in these embryos, and the protein levels of tubulin were unchanged (Fig. 3 c and Fig. S1 a, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200603146/DC1, and see Fig. 5 a).

Figure 3.

Ablation of TIF1α reduces the number of embryos that develop to the blastocyst stage. (a) RNAi for TIF1α results in arrested development at the 2–4-cell stage transition. Early zygotes were injected with dsRNA for GFP or dsRNA for TIF1α or were not injected. The embryos were cultured until the blastocyst stage, and the embryos of each experimental group were counted and scored. Shown is the percentage of embryos for each group that reached a determined developmental stage, where the total number of embryos derives from five different experiments. (b) Pictures of noninjected controls and embryos injected with dsRNA for GFP or dsRNA for TIF1α taken 42 h after dsRNA injection. The embryos injected with dsRNA for TIF1α remain at the 2-, 3-, or 4-cell stages, whereas the control groups reached later stages. Shown are representative embryos of eight independent experiments. (c) Western blot analysis for TIF1α of control embryos injected with dsRNA for GFP and experimental embryos injected with dsRNA showing down-regulation of TIF1α protein induced by RNAi. Tubulin was used as loading control. (d) Neutralization of TIF1α function through antibody injection leads to developmental arrest. Early zygotes were injected with antibodies anti-Flag or anti-TIF1α or were not injected and were cultured until the controls reached the blastocyst stage. Embryos were counted and scored according to their developmental stage. Shown is the percentage of embryos for each group from a total of five different experiments.

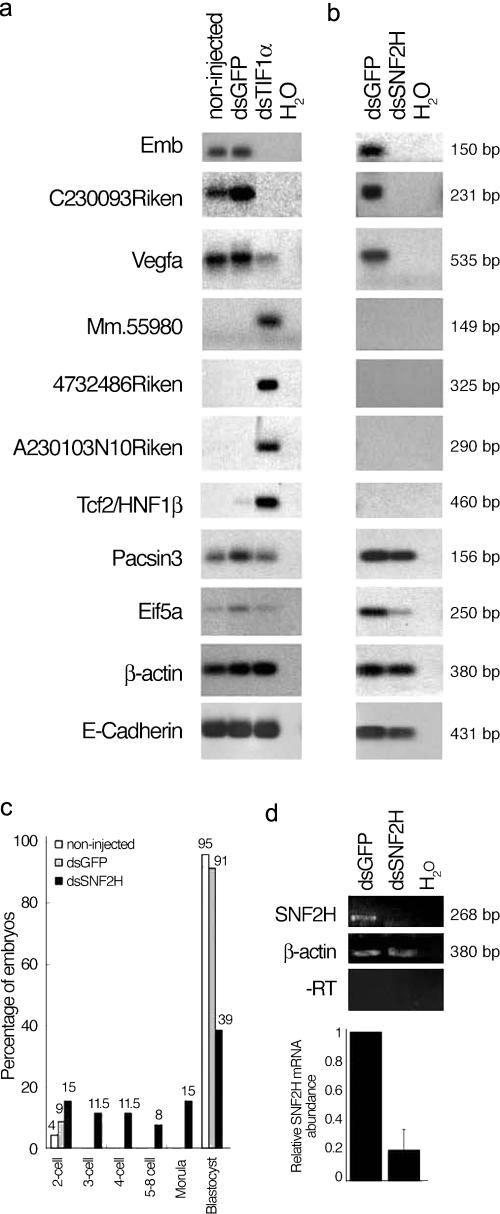

Figure 5.

Misregulation of the expression of TIF1α target genes identified through ChIP cloning induced by RNAi. (a) RT-PCR analysis for nine of the genes identified through ChIP cloning. Early zygotes were microinjected with dsRNA for GFP or for TIF1α or were not injected and were analyzed by RT-PCR. Shown are representative samples for the noninjected controls, for the dsGFP controls, and from embryos injected with dsRNA for TIF1α. (b) Misregulation of a subset of TIF1α target genes upon RNAi for SNF2H in early zygotes. Early zygotes were microinjected as in panel a with dsRNA for SNF2H and analyzed by RT-PCR for the TIF1α target genes as indicated. β-Actin was used as an internal control. (c) Development of embryos upon SNF2H RNAi. Early zygotes were injected with dsRNA for GFP or for SNF2H or were not injected. Embryos were cultured until the blastocyst stage, and embryos of each experimental group were counted and scored. Shown is the percentage of embryos for each group that reached a determined developmental stage. (d) Down-regulation of SNF2H upon dsRNA injection in zygotes. The same samples used in panel b were analyzed by RT-PCR for SNF2H. β-Actin and no reverse-transcriptase controls are shown. The graph shows the quantification of SNF2H transcripts upon RNAi normalized against β-actin mRNA. Shown are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

As an additional approach to test TIF1α function, we performed a similar series of experiments, this time blocking TIF1α protein through injection of antibodies. Although the majority of the Flag antibody–injected (87%; n = 35; four independent experiments) and noninjected control embryos (100%; n = 56; four independent experiments) developed to the blastocyst stage, 86% of the embryos injected with antibodies against TIF1α arrested between the 2- and 4-cell stages (n = 50; four independent experiments; Fig. 3 d). Most embryos (46%) arrested at the 3-cell stage, and 20% of the embryos developed to the 4-cell stage. Thus, injection of antibodies, similarly to RNAi, caused the majority of embryos to arrest at the 2–4-cell stage. Although the arrest was slightly stronger upon antibody injection, this is unsurprising, as the injection of antibodies may result in a more immediate neutralization of TIF1α than RNAi. These results show that reducing the levels of TIF1α by two complementary approaches (either through interference with the message or with the protein) results in a decreased number of embryos that develop to the blastocyst stage.

Ablation of TIF1α function leads to aberrant localization of SNF2H, BRG-1, and RNA polII

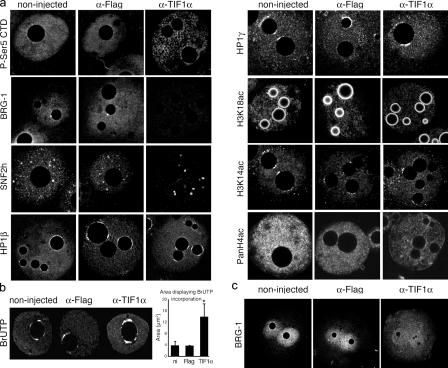

To further understand the phenotype resulting from ablation of TIF1α, we injected TIF1α antibodies before the onset of genome activation and examined the localization of SNF2H and BRG-1 at the late zygote stage, that is, at the time of genome activation. We also analyzed the localization of the active (Ser5-phosphorylated) form of the RNA polII in the injected zygotes. We found that ablation of TIF1α resulted in a change in the distribution of the active Ser5-phosphorylated form of RNA polII (Fig. 4 a). The active RNA polII localized in a patchy and foci-network distribution instead of the homogeneous pattern throughout the nucleoplasm observed in the control embryos (n = 10; Fig. 4 a), suggesting an effect on transcription. Blocking of TIF1α resulted in the mislocalization of BRG-1, which was only barely detected in the pronuclei of the injected zygotes and showed a diffuse staining in the cytoplasm (n = 9; Fig. 4, a and c). The distribution of SNF2H was also affected: the small foci observed throughout the nucleoplasm of the control embryos were no longer visible after ablation of TIF1α. Instead, SNF2H accumulated in few larger foci (n = 10; Fig. 4 a). Given that heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) recruitment and histone acetylation increase gradually in the zygote and that both are involved in regulation of gene expression (Adenot et al., 1997; Arney et al., 2002; Hediger and Gasser, 2006), we also examined the effect of TIF1α ablation on HP1 localization and histone acetylation. Moreover, HP1 proteins can associate with both active and silent chromatin (Hediger and Gasser, 2006). Ablation of TIF1α did not affect HP1β (n = 15) or HP1γ (n = 9) localization. Similarly, the acetylation status of lysines 14 and 18 of histone H3 remained unchanged and that of histone H4 was not drastically affected (n = 8; Fig. 4 a). Similar results were observed when the same experiments were performed upon RNAi (unpublished data).

Figure 4.

Ablation of TIF1α leads to aberrant localization of RNA polII, SNF2H, and BRG-1 but does not affect HP1β localization or histone H3 acetylation. (a) Zygotes were microinjected with the antibodies anti-Flag or anti-TIF1α or were not injected and were cultured for 7 h, until the late zygote stage. The embryos were then analyzed with the indicated antibodies using a 60× oil objective under confocal microscopy. For each antibody, embryos from the three groups were processed in parallel and were analyzed using the same confocal laser power. Shown are representative pronuclei of at least 10 zygotes analyzed for each experimental group and for each antibody used. The same results were observed in both female and male pronuclei. (b) Pattern of BrUTP incorporation upon ablation of TIF1α. BrUTP incorporation was analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence in zygotes after microinjection of antibodies. After injection of BrUTP and the indicated antibodies, embryos were cultured for 7 h, fixed, and analyzed using a BrdU antibody. All the samples were processed in parallel and analyzed under a 60× oil objective using the same confocal parameters. (left) Representative pronuclei of six (noninjected [ni] and Flag) and nine (TIF1α) zygotes. For quantification, the area of the pronuclei was first delimited and extracted using Volocity, and the area displaying BrUTP incorporation within each pronucleus was quantified using the same software. The graph shows the mean ± SD of at least six replicates for each group of embryos. *, P = 0.0001, t test. (c) BRG-1 was localized in the cytoplasm and was barely detected in the pronuclei upon TIF1α ablation. Zygotes were microinjected as in panel a and processed for immunostaining with a BRG-1 antibody in parallel. Shown are representatives of at least 10 zygotes.

Given that TIF1α ablation provoked a change in the localization of the RNA polII, we next wished to assess whether ablation of TIF1α elicited a general defect in transcription. To this end, we analyzed the pattern of staining of BrUTP incorporation in the late zygote after ablation of TIF1α. The embryos remained transcriptionally active after interference with TIF1α (Fig. 4 b). Ablation of TIF1α did not appear to result in striking differences in the pattern of BrUTP incorporation in comparison with the control groups. However, an in-depth observation revealed that the general signal of fluorescence was more disperse, and the accumulation of BrUTP around the NLBs seemed slightly enhanced. This observation was confirmed by quantification of the area containing transcription foci, which showed a small and reproducible increase in the area being transcribed in the embryos after ablation of TIF1α compared with the two control groups (Fig. 4 b). Thus, blocking of TIF1α did not abolish transcription, consistent with our observation that TIF1α localizes only to specific sites of active transcription (Fig. 2 a), but induced a significant change in the area of BrUTP incorporation.

Mislocalization of BRG-1 and SNF2H observed by immunofluorescence after TIF1α ablation suggested that TIF1α might be involved in the nuclear localization of these two chromatin remodeling proteins in the late zygote. Given that not all of the BRG-1 colocalized with TIF1α (Fig. 2 b), the reduced signal of BRG-1 staining in the pronuclei resulting from TIF1α ablation suggests that TIF1α may play a role in the nucleation of BRG-1. Alternatively, the absence of TIF1α could affect the expression of SNF2H and/or BRG-1. We attempted to examine by Western blot whether the protein levels of SNF2H and/or BRG-1 were affected after ablation of TIF1α, but because of technical limitations attributable to the amount of material, we could not draw any conclusion. However, we found that the mRNA levels of both BRG-1 and SNF2H were maintained in the embryos after ablation of TIF1α (Fig. S2 b). We observed a slight decrease of the mRNA levels of SNF2H upon TIF1α ablation, which could correlate with the decreased staining that we observed in our immunofluorescence experiments. Thus, our data indicate that ablation of TIF1α function results in the mislocalization of BRG-1 and SNF2H in the zygote.

TIF1α modulates transcription of a specific set of genes in the embryo

The mislocalization of the active form of the RNA polII, together with the change in the transcriptionally active area resulting from TIF1α loss, could indicate that specific sites of initiation of transcription may be disrupted and/or mislocalized in the zygote after TIF1α ablation. Therefore, we next examined whether TIF1α binds to specific genes in the zygote and whether the expression of these genes would be misregulated as a consequence of TIF1α ablation. To this end, we first used a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) cloning approach in late zygotes, which we modified to circumvent the constraint of the requirement of large amounts of material (see the supplemental text, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200603146/DC1). Our approach allowed us to identify 18 candidate target genes of TIF1α in the late zygote. These encode proteins that perform diverse cellular functions (Table I). Second, to validate these target genes and to explore whether the genes identified by ChIP cloning are indeed regulated by TIF1α, we randomly chose 10 of them and examined their expression in embryos that had been subjected to TIF1α RNAi. We injected dsTIF1α in zygotes before the onset of genome activation (at the fertilization cone stage) and performed RT-PCR at a time when the embryos would have been gone through genome activation. We found that 9 out of the 10 genes that we analyzed were indeed misregulated after TIF1α interference (Fig. 5). The changes elicited in the levels of gene expression varied from complete loss of the corresponding mRNA (Emb and C230093Riken), to partial (Vegfa) or very slight (Pacsin3 and Eif5a) down-regulation, to robust up-regulation (Tcf2, Mm.55980, 4732486Riken, and A230103N10Riken). Although the expression pattern between the zygote and the 4-cell stage of most of these genes is not known, Emb expression has been shown to increase its mRNA levels around the zygote stage (Wang et al., 2004), consistent with it being one of the genes that requires TIF1α to be activated at the zygote stage (Fig. 5).

Table I.

Identification of genes regulated by TIF1α in the mouse zygote

| Gene | Chromosome |

|---|---|

| Cytoskeleton/processing | |

| Flrt3 | 1 |

| Pacsin3 | 2 |

| Itih2 | 2 |

| Emb | 13 |

| Npm-Rar | 5 |

| Translation | |

| Eif5a | 11 |

| Transcriptional regulators | |

| Tcf2 (HNF1β) | 11 |

| Npas3 | 12 |

| Signaling | |

| Vegfa | 17 |

| Epha6 | 16 |

| Prkcq | 2 |

| Unknown genes | |

| 4732486Riken cDNA | 2 |

| C230093Riken cDNA | 2 |

| A830008007Riken cDNA | 1 |

| cDNA Mm.55980 | 9 |

| 1700012H17 Riken cDNA | 4 |

| A230103N10Rik cDNA | 11 |

| LOC384193 | 5 |

To verify whether the changes in gene expression upon TIF1α RNAi were specific, we analyzed the mRNA levels of three genes as internal control: β-actin, TIF1β, and E-cadherin. None of these three genes showed changes in their mRNA levels (Fig. 5 and Fig. S2). This suggests, in agreement with what we observed for the BrUTP incorporation profile, that down-regulation of TIF1α does not elicit a general defect in transcription but only affects the expression of a specific set of genes. Moreover, TIF1α acts not only as an activator of its target genes but can also prevent the activation of others. Importantly, genes such as Vegfa, Tcf2 (HNF1β), Emb, and Eif5a have documented functions in early embryonic development and/or cell growth (Huang et al., 1993; Barbacci et al., 1999; Coffinier et al., 1999; Miquerol et al., 1999, 2000). Thus, our data indicate that TIF1α is required to determine the transcriptional state (active or repressed) of a set of genes in the late zygote.

A subset of TIF1α target genes is misregulated upon RNAi for SNF2H

After observing the mislocalization of SNF2H and BRG-1 upon TIF1α ablation, we hypothesized that if these chromatin remodelers are relevant for its function in the zygote, the expression of at least some of the TIF1α target genes should be affected when either BRG-1 or SNF2H are knocked down. To test this hypothesis and given that SNF2H can coimmunoprecipitate with TIF1α (Fig. S4, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200603146/DC1), we performed RNAi for SNF2H using the same conditions as for TIF1α RNAi. Early zygotes at the fertilization cone stage were microinjected with dsRNA for SNF2H; injections of dsRNA for GFP as well as noninjected embryos were used as negative controls. The embryos subjected to SNF2H RNAi divided to the 2-cell stage normally (n = 52). The control embryos developed normally to the blastocyst stage (noninjected, 95%, n = 23; dsGFP, 91%, n = 23). Although approximately half of the embryos injected with dsRNA for SNF2H developed to the morula and blastocyst stages (54%; n = 52), the other half showed developmental arrest between the 2- and 8-cell stages (46%; n = 52; Fig. 5 c).

We then analyzed the same genes that we analyzed after RNAi for TIF1α. RT-PCR of these genes revealed a subset of genes (Emb, C230093Riken, and Vegfa) that showed a drastic down-regulation in their mRNA levels after injection of dsRNA for SNF2H (Fig. 5 b). These genes corresponded to the genes that were down-regulated upon TIF1α RNAi (Fig. 5 a). Similar to what we observed for TIF1α RNAi, we also observed a slight decrease in the expression of Pacsin3 and Eif5a after RNAi for SNF2H. We did not observe any effect on the expression of Tcf2, Mm.55980, 4732486Riken, or A230103N10Riken, which remained not expressed in the embryos after RNAi for SNF2H (Fig. 5 b). This was in contrast to what we observed after RNAi for TIF1α, which resulted in a robust up-regulation of the corresponding mRNA for this second group of genes (Fig. 5, compare a and b). Fig. 5 d shows that SNF2H knockdown was induced efficiently in the embryos. Thus, although the effect on gene regulation elicited upon TIF1α ablation was both up- and down-regulation of target genes, RNAi for SNF2H resulted only in down-regulation of the same target genes that were down-regulated after TIF1α RNAi. This data suggests that TIF1α regulates activation of gene expression of a subset of its target genes in the zygote through SNF2H function.

Discussion

We have investigated the role of TIF1α in the early development of the mouse embryo. We show that at the onset of genome activation, TIF1α translocates into the pronuclei and accumulates in specific regions of RNA synthesis that are enriched with chromatin remodelers. Ablation of TIF1α results in the mislocalization of RNA polII, SNF2H, and BRG-1, and in the misregulation of a particular set of genes. Thus, TIF1α is a maternal factor that functions in the first wave of embryonic genome activation as a modulator of the transcriptional state of a subset of genes.

TIF1α was originally cloned because of its ability to interact with nuclear receptors (Le Douarin et al., 1995). Although we cannot rule out a functional interaction with the nuclear receptors at this stage, the expression of the nuclear receptors known to interact with TIF1α is undetectable in the stages of development that are within the time window of our study (Wang et al., 2004). Our data show that TIF1α plays a role as a modulator of embryonic transcription and suggest that its function in the zygote is required for the proper localization of chromatin remodelers and the RNA polII.

Several reports have documented TIF1α acting as a repressor or as an activator in cultured cells and, therefore, its role as a coactivator appears controversial (Le Douarin et al., 1995, 1996; Venturini et al., 1999; Peng et al., 2002). Although the discrepancies could be explained by the differences in the systems used in those studies, it is also likely that TIF1α plays a dual role in regulating repression versus activation of specific genes. This is supported by the effects on gene expression observed here after TIF1α RNAi in early mouse embryos.

TIF1α function could also be regulated, as it may associate with different chromatin remodeling complexes, ultimately causing changes in the transcription of selected genes. Thus, the proteins TIF1α associates with would determine the specificity and the outcome on transcription (activation versus repression). Indeed, remodeling complexes containing BRG-1 and SNF2H can lead to both activation and repression of gene expression (Pal et al., 2003, 2004; Eberharter and Becker, 2004). Our results suggest that TIF1α regulates activation of a subset of its target genes through SNF2H function. Further, lack of recruitment of BRG-1 may also account for some of the changes in gene expression that we observed after TIF1α ablation. Mislocalization of SNF2H, BRG-1, and RNA polII itself suggests that TIF1α may be involved at least partially in the localization of these remodeling complexes in the zygote. In support, we found that SNF2H can coimmunoprecipitate with TIF1α (Fig. S4). Moreover, TIF1α's ability to nucleate the formation of a ternary complex with coactivators has recently been documented (Teyssier et al., 2005). Thus, we propose that recruitment of TIF1α to specific sites in the genome would ensure the localization of initiating RNA polII on one hand and of chromatin remodeling complexes on the other, and the “choice” of particular chromatin remodeling complexes will determine the outcome on transcription.

The tripartite motif proteins have been implicated in processes such as cell differentiation, growth, and development. In Drosophila melanogaster, Bonus, a TIF homologue, is essential for cell viability and embryogenesis (Beckstead et al., 2001). Of the four TIF members reported in mammals (Le Douarin et al., 1995, 1996; Venturini et al., 1999; Khetchoumian et al., 2004), TIF1β has been shown to be required for the specification of the anteroposterior axis in the mouse (Cammas et al., 2000). However, in view of the observation that TIF1β is also expressed in early embryos, it remains to be established whether TIF1β also plays a role earlier in development. Although the protein motifs in the TIFs are conserved—a tripartite domain composed of a coiled-coiled, a RING (really interesting new gene) domain, and a B-box, and a bromodomain in the C terminus (Reymond et al., 2001)—some molecular differences have been documented that translate into functional differences among the TIFs: only TIF1β can target histone deacetylase activity, thereby acting as a corepressor, and it localizes to heterochromatin, the latter via interactions with HP1 (Schultz et al., 2001; Cammas et al., 2002). Additionally, TIF1β has so far not been reported to interact with nuclear receptors, in contrast to TIF1α (Le Douarin et al., 1996). Moreover, TIF1α possesses a kinase activity (Fraser et al., 1998) that has not been documented for the other TIFs. Likewise, the RING domain of TIF1γ acts as a ubiquitinase (Dupont et al., 2005), but this activity has so far not been detected in TIF1α or -β. Interestingly, this RING-like ubiquitinase activity is required for ectoderm induction in Xenopus laevis (Dupont et al., 2005). The functional heterogeneity of the TIFs may account for the different roles that so far have been assigned to some of them during embryogenesis.

Our work now documents a role for TIF1α in early development and in regulation of transcription in the mouse zygote. In this context, it is important to note that altogether the group of TIF1α target genes that we have identified cover several cellular processes that are essential for early development, such as translation (Eif5a) and adhesion (Flrt3, Emb, and Itih2; Fleming et al., 2000; Schultz, 2002). In fact, the expression of some translation initiation factors correlates with the maternal-to-zygotic transition in mouse embryos (De Sousa et al., 1998). The target genes under the “unknown” category include a conserved mRNA for a protein containing a highly basic lysine domain of unknown function (4732486Riken), a protein with domains predicted to be involved in RNA processing and transcriptional regulation (C230093Riken), and an mRNA deadenylase (A230103N10Rik). Although the relevance of each of these genes in early development remains to be investigated, their coordinated expression may be of functional significance in the control of the maternal-to-zygotic transition.

The expression pattern of TIF1α in the preimplantation embryo is reminiscent of that of Oct4/Pou5f1, which is expressed initially in all blastomeres but then becomes restricted to the ICM, and whose expression is essential for maintaining the pluripotency of the ICM cells (Nichols et al., 1998). Moreover, TIF1α expression decreases upon differentiation of embryonic stem cells (Remboutsika et al., 1999). It is also noteworthy that TIF1α has been reported to be a direct target gene of Nanog in mouse embryonic stem cells (Loh et al., 2006). Thus, in the future, it will be interesting to determine whether expression of TIF1α contributes to the establishment or the maintenance of the pluripotent capacities of the early mouse embryo. Such a role for TIF1α is supported by the failure of most embryos lacking TIF1α to develop to the blastocyst stage, and by the changes in the localization of SNF2H and BRG-1 resulting from TIF1α ablation, both of which are required for ICM and/or trophectoderm survival in the mouse (Bultman et al., 2000; Stopka and Skoultchi, 2003). During the early stages of development, decisions about cell fate determination, pluripotency, and patterning are made. Thus, the chromatin has to be dynamically remodeled for opening and closing specific regions in response to those events. TIF1α could take part in this process by activating or repressing particular sets of genes. Our data suggest that TIF1α is a factor involved in epigenetic mechanisms in early mammalian development.

Materials and methods

Embryo collection and culture

Embryos were collected from F1 (C57BL/6 × CBA/H) 6-wk-old superovulated females as described previously (Hogan et al., 1994). For the RNAi experiments, F1 females were mated with EF-1α MmGFP transgenic males (Zernicka-Goetz and Pines, 2001). All other experiments were performed with F1 × F1 crosses. Zygotes and cleavage stage embryos were collected at the indicated hours after human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) injection and cultured in KSOM medium (Specialty Media, Inc.) as described previously (Hogan et al., 1994). All animals were handled in accordance to Home Office legislation.

In situ hybridization

Freshly collected embryos at various stages were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. In situ hybridizations were performed as described previously (Wilkinson et al., 1990), except that the embryos were not dehydrated and the proteinase K treatment was omitted. The TIF1α probe was prepared and labeled with digoxygenin-UTP using the pSK.TIF1α plasmid (provided by R. Losson, Institut de Génétique et de Biologie Moléculaire et Cellulaire [IGBMC], Strasbourg, France) as a template (Niederreither et al., 1999).

Immunostaining and confocal analysis

After removal of the zona pellucida with acid Tyrode's solution (Sigma-Aldrich), embryos were washed three times in PBS and fixed in 5% paraformaldehyde, 0.04% Triton X-100, 0.3% Tween, and 0.2% sucrose in PBS for 20 min at 37°C. After permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min, the embryos were washed three times in 0.1% Tween in PBS (PBS-T), blocked in 3% BSA in PBS-T, and incubated with the primary antibodies for ∼12 h at 4°C. Embryos were then washed twice in PBS-T, blocked for 30 min, and incubated for 2 h at 25°C with the corresponding secondary antibodies. After two washes in PBS-T, the DNA was stained with TOTO-3 (Invitrogen) and the embryos were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) and analyzed using a 60×/1.40 oil objective (Nikon) in an upright confocal laser microscope (Radiance; Bio-Rad Laboratories) using the LaserSharp 2000 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories) at room temperature. The antibodies used in this work are as follows: TIF1α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), KAP1 (TIF1β; Abcam), RNA polII (recognizing the CTD phosphorylated in Ser5; CTD4H8; Upstate Biotechnology), BRG-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), hSNF2H (provided by P. Varga-Weisz, The Babraham Institute, Cambridge, UK; Bozhenok et al., 2002), tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich), HP1β (IGBMC), HP1γ (IGBMC), acetylated histone H4 (Upstate Biotechnology), acetylated K14 histone H3 (provided by B. Turner, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK), and acetylated K18 histone H3 (Abcam). Secondary antibodies were coupled with either Alexa Fluor 568 or 488. Images were then prepared or analyzed using Photoshop 7 (Adobe) and Volocity (Improvision), respectively.

BrUTP labeling

BrUTP labeling was performed as described previously (Borsuk and Maleszewski, 2002). Embryos were collected 24 h after hCG injection and microinjected using a transjector (model 5246; Eppendorf) with 1–2 pl of 100 mM BrUTP (Sigma-Aldrich) in 2 mM Pipes and 140 mM KCl, pH 7.4. Embryos were fixed after 3 h of culture and processed for immunostaining using an anti-BrdU antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). For quantification of BrUTP incorporation in pronuclei after microinjection of antibodies, the embryos were collected at 20 h after hCG injection and microinjected with BrUTP followed by microinjection of antibodies as described (see Microinjection of antibodies). For the analysis after immunostaining, the area of the pronucleus of injected zygotes was defined and cropped using Volocity. The pixels were then selected under a 30% tolerance level, and the area displaying BrUTP staining was quantified using the measurement tools of the software as recommended by the manufacturer.

RNAi and RT-PCR

Zygotes were collected and microinjected at 20 h after hCG injection with 1–2 pl of 1 μg/μl long dsRNA for TIF1α, long dsRNA for SNF2H, or long dsRNA for GFP (Wianny and Zernicka-Goetz, 2000). The sequence for the dsRNA for TIF1α spans nucleotides 1284–1771, which shares no homology with the other members of the family. For the SNF2H RNAi experiments, dsRNA spanning nucleotides 2041–2520 of the cDNA was used.

For RT-PCR analysis, embryos were collected ∼42 h after dsRNA injection and processed for RT in pools of five embryos, each using the Dynabeads mRNA direct micro kit (Dynal). Embryos were collected at the same stages for all the samples to avoid variation resulting from embryos derived from different stages. Half of the mRNA extracted (10 μl) was used for the reverse-transcriptase controls and the other half for cDNA synthesis. PCR was performed with 1/20 of the cDNA (0.5 μl), such that all genes were analyzed in the same sample using 60 cycles for amplification, except for Eif5a and Tcf2, in which 35 cycles were used, and Epha6, Snf2h, and Brg-1, in which 50 cycles were used. It was verified that the cycling conditions were within the exponential phase of amplification for each gene. The products were transferred onto a Hybond N+ membrane (GE Healthcare), hybridized against the corresponding probes, and exposed for autoradiography.

RT-PCR analysis of TIF1α was performed in 15 freshly collected oocytes, 15 zygotes, 15 2-cell stage, 4 6–16-cell stage, 5 embryonic day 5.5, and 5 embryonic day 6.5 embryos. cDNA samples were amplified for 40 cycles. Note that maternal transcripts are not distinguishable from zygotic ones.

Microinjection of antibodies

Antibodies against TIF1α and Flag (Sigma-Aldrich) were microdialyzed overnight at 4°C against Tris-EDTA, pH 8.0, and concentrated using a filter (Centricon; Amicon) to a final concentration of 215 ng/μl (Bevilacqua et al., 2000). Zygotes collected at 20 h after hCG injection were microinjected with ∼1–2 pl of antibody solution and cultured. For the immunostaining analysis, the embryos were fixed after 7 h of culture.

Western blot analysis

Embryos from five different experiments were collected 42 h after dsRNA injection, washed three times in PBS, pooled (155 embryos per group), and subjected to Tris-Glycine PAGE-SDS. Competition assays with the corresponding TIF1α-blocking peptide were performed to ensure the specificity of the antibody (Fig. S3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200603146/DC1).

ChIP and cloning

We first assessed the ability of the antibody to immunoprecipitate TIF1α in pronuclei extracts (Fig. S3). For the ChIP, 413 zygotes were collected in M2 at 27 h after hCG injection, formaldehyde cross-linked, washed, and lysed in 5 mM Pipes, pH 8.0, 85 mM KCl, and 0.05% NP-40. The pronuclei were then lysed and sonicated. For the immunoprecipitation, 1 μg of TIF1α antibody was used after preclearing of the chromatin. The samples were then extensively washed, eluted with 50 mM NaHCO3 and 1% SDS, and treated with proteinase K at 65°C for 4 h. After purification, DNA was incubated with T4 DNA polymerase and ligated to two unidirectional linkers (Oberley et al., 2003). The samples were amplified by PCR, cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega), and sequenced. Out of 25 clones sequenced, 19 contained inserts that corresponded to regions of different genes, many of them unknown. The remaining six clones contained background sequences corresponding to the cloning vector or Escherichia coli. Two clones contained sequences of the same gene, which led us to select 18 candidate genes. We provide a detailed protocol in the supplemental text.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows typical BrUTP accumulation in late zygote and 2-cell stage embryos. Fig. S2 provides evidence that RNAi for TIF1α does not induce down-regulation of TIF1β and an analysis of the mRNA levels of SNF2H and BRG-1 upon TIF1α RNAi. Fig. S3 shows the characterization of the TIF1α antibody used in this work. Fig. S4 depicts coimmunoprecipitation of SNF2H with TIF1α. The supplemental text provides a detailed protocol for ChIP cloning in zygotes. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200603146/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. R. Losson for kindly providing the pSK.TIF1a plasmid, Dr. P. Varga-Weisz for the hSNF2H antibody, Dr. B. Turner for the acetylK14 H3 antibody, and C. Lee for the mouse embryonic fibroblasts. We thank R. Schneider, S. Daujat, P. Varga-Weisz, and K. Ancelin for helpful discussions and A. Bannister, R. Livesely, and J. Pines for critical reading of the manuscript.

The initial phase of this work was supported by a Human Frontier Science Program grant awarded to R. Pedersen, J. Rossant, and M. Zernicka-Goetz. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust. M. Zernicka-Goetz is a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow. M.-E. Torres-Padilla is the recipient of a European Molecular Biology Organization long-term fellowship (ALT 2-2003).

Abbreviations used in this paper: BRG-1, Brahma-related gene 1; BrUTP, 5-bromo UTP; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; GV, germinal vesicle; hCG, human chorionic gonadotrophin; HP1, heterochromatin protein 1; ICM, inner cell mass; NLB, nucleolar-like body; TIF, transcription intermediary factor.

References

- Adenot, P.G., Y. Mercier, J.P. Renard, and E.M. Thompson. 1997. Differential H4 acetylation of paternal and maternal chromatin precedes DNA replication and differential transcriptional activity in pronuclei of 1-cell mouse embryos. Development. 124:4615–4625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agalioti, T., S. Lomvardas, B. Parekh, J. Yie, T. Maniatis, and D. Thanos. 2000. Ordered recruitment of chromatin modifying and general transcription factors to the IFN-beta promoter. Cell. 103:667–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, F., D.M. Worrad, and R.M. Schultz. 1997. Regulation of transcriptional activity during the first and second cell cycles in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Dev. Biol. 181:296–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arney, K.L., S. Bao, A.J. Bannister, T. Kouzarides, and M.A. Surani. 2002. Histone methylation defines epigenetic asymmetry in the mouse zygote. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 46:317–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachvarova, R. 1985. Gene expression during oogenesis and oocyte development in mammals. Dev. Biol. (N Y 1985). 1:453–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbacci, E., M. Reber, M.O. Ott, C. Breillat, F. Huetz, and S. Cereghini. 1999. Variant hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 is required for visceral endoderm specification. Development. 126:4795–4805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaujean, N., C. Bouniol-Baly, C. Monod, K. Kissa, D. Jullien, N. Aulner, C. Amirand, P. Debey, and E. Kas. 2000. Induction of early transcription in one-cell mouse embryos by microinjection of the nonhistone chromosomal protein HMG-I. Dev. Biol. 221:337–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead, R., J.A. Ortiz, C. Sanchez, S.N. Prokopenko, P. Chambon, R. Losson, and H.J. Bellen. 2001. Bonus, a Drosophila homolog of TIF1 proteins, interacts with nuclear receptors and can inhibit betaFTZ-F1-dependent transcription. Mol. Cell. 7:753–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellier, S., S. Chastant, P. Adenot, M. Vincent, J.P. Renard, and O. Bensaude. 1997. Nuclear translocation and carboxyl-terminal domain phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II delineate the two phases of zygotic gene activation in mammalian embryos. EMBO J. 16:6250–6262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, A., M.T. Fiorenza, and F. Mangia. 2000. A developmentally regulated GAGA box-binding factor and Sp1 are required for transcription of the hsp70.1 gene at the onset of mouse zygotic genome activation. Development. 127:1541–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsuk, E., and M. Maleszewski. 2002. DNA replication and RNA synthesis in thymocyte nuclei microinjected into the cytoplasm of artificially activated mouse eggs. Zygote. 10:229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouniol, C., E. Nguyen, and P. Debey. 1995. Endogenous transcription occurs at the 1-cell stage in the mouse embryo. Exp. Cell Res. 218:57–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouniol-Baly, C., E. Nguyen, D. Besombes, and P. Debey. 1997. Dynamic organization of DNA replication in one-cell mouse embryos: relationship to transcriptional activation. Exp. Cell Res. 236:201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozhenok, L., P.A. Wade, and P. Varga-Weisz. 2002. WSTF-ISWI chromatin remodeling complex targets heterochromatic replication foci. EMBO J. 21:2231–2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultman, S., T. Gebuhr, D. Yee, C. La Mantia, J. Nicholson, A. Gilliam, F. Randazzo, D. Metzger, P. Chambon, G. Crabtree, and T. Magnuson. 2000. A Brg1 null mutation in the mouse reveals functional differences among mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Mol. Cell. 6:1287–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammas, F., M. Mark, P. Dolle, A. Dierich, P. Chambon, and R. Losson. 2000. Mice lacking the transcriptional corepressor TIF1beta are defective in early postimplantation development. Development. 127:2955–2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammas, F., M. Oulad-Abdelghani, J.L. Vonesch, Y. Huss-Garcia, P. Chambon, and R. Losson. 2002. Cell differentiation induces TIF1beta association with centromeric heterochromatin via an HP1 interaction. J. Cell Sci. 115:3439–3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffinier, C., D. Thepot, C. Babinet, M. Yaniv, and J. Barra. 1999. Essential role for the homeoprotein vHNF1/HNF1beta in visceral endoderm differentiation. Development. 126:4785–4794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa, P.A., A.J. Watson, and R.M. Schultz. 1998. Transient expression of a translation initiation factor is conservatively associated with embryonic gene activation in murine and bovine embryos. Biol. Reprod. 59:969–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, S., L. Zacchigna, M. Cordenonsi, S. Soligo, M. Adorno, M. Rugge, and S. Piccolo. 2005. Germ-layer specification and control of cell growth by Ectodermin, a Smad4 ubiquitin ligase. Cell. 121:87–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberharter, A., and P.B. Becker. 2004. ATP-dependent nucleosome remodelling: factors and functions. J. Cell Sci. 117:3707–3711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, T.P., M.R. Ghassemifar, and B. Sheth. 2000. Junctional complexes in the early mammalian embryo. Semin. Reprod. Med. 18:185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, R.A., D.J. Heard, S. Adam, A.C. Lavigne, B. Le Douarin, L. Tora, R. Losson, C. Rochette-Egly, and P. Chambon. 1998. The putative cofactor TIF1alpha is a protein kinase that is hyperphosphorylated upon interaction with liganded nuclear receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 273:16199–16204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain-Desprez, D., M. Bazinet, M. Bouvier, and M. Aubry. 2003. Oligomerization of transcriptional intermediary factor 1 regulators and interaction with ZNF74 nuclear matrix protein revealed by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer in living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278:22367–22373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamatani, T., M.G. Carter, A.A. Sharov, and M.S. Ko. 2004. Dynamics of global gene expression changes during mouse preimplantation development. Dev. Cell. 6:117–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hediger, F., and S.M. Gasser. 2006. Heterochromatin protein 1: don't judge the book by its cover! Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 16:143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, B.L., R. Beddington, F. Costantini, and E. Lacy. 1994. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. 475 pp.

- Huang, R.P., M. Ozawa, K. Kadomatsu, and T. Muramatsu. 1993. Embigin, a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily expressed in embryonic cells, enhances cell-substratum adhesion. Dev. Biol. 155:307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khetchoumian, K., M. Teletin, M. Mark, T. Lerouge, M. Cervino, M. Oulad-Abdelghani, P. Chambon, and R. Losson. 2004. TIF1δ, a novel HP1-interacting member of the transcriptional intermediary factor 1 (TIF1) family expressed by elongating spermatids. J. Biol. Chem. 279:48329–48341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecny, V., V. Landa, and A. Pavlok. 1995. Localization of nucleic acids in the nucleoli of oocytes and early embryos of mouse and hamster: an autoradiographic study. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 41:449–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H., A.N. Imbalzano, P.A. Khavari, R.E. Kingston, and M.R. Green. 1994. Nucleosome disruption and enhancement of activator binding by a human SW1/SNF complex. Nature. 370:477–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladurner, A.G., C. Inouye, R. Jain, and R. Tjian. 2003. Bromodomains mediate an acetyl-histone encoded antisilencing function at heterochromatin boundaries. Mol. Cell. 11:365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro, M.A., and D.J. Picketts. 2001. Cloning and characterization of the murine Imitation Switch (ISWI) genes: differential expression patterns suggest distinct developmental roles for Snf2h and Snf2l. J. Neurochem. 77:1145–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin, B., C. Zechel, J.M. Garnier, Y. Lutz, L. Tora, P. Pierrat, D. Heery, H. Gronemeyer, P. Chambon, and R. Losson. 1995. The N-terminal part of TIF1, a putative mediator of the ligand-dependent activation function (AF-2) of nuclear receptors, is fused to B-raf in the oncogenic protein T18. EMBO J. 14:2020–2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin, B., A.L. Nielsen, J.M. Garnier, H. Ichinose, F. Jeanmougin, R. Losson, and P. Chambon. 1996. A possible involvement of TIF1 alpha and TIF1 beta in the epigenetic control of transcription by nuclear receptors. EMBO J. 15:6701–6715. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legouy, E., E.M. Thompson, C. Muchardt, and J.P. Renard. 1998. Differential preimplantation regulation of two mouse homologues of the yeast SWI2 protein. Dev. Dyn. 212:38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh, Y.H., Q. Wu, J.L. Chew, V.B. Vega, W. Zhang, X. Chen, G. Bourque, J. George, B. Leong, J. Liu, et al. 2006. The Oct4 and Nanog transcription network regulates pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Genet. 38:431–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J., P. Svoboda, R.M. Schultz, and P. Stein. 2001. Regulation of zygotic gene activation in the preimplantation mouse embryo: global activation and repression of gene expression. Biol. Reprod. 64:1713–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquerol, L., M. Gertsenstein, K. Harpal, J. Rossant, and A. Nagy. 1999. Multiple developmental roles of VEGF suggested by a LacZ-tagged allele. Dev. Biol. 212:307–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquerol, L., B.L. Langille, and A. Nagy. 2000. Embryonic development is disrupted by modest increases in vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression. Development. 127:3941–3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, H.D., F. Santos, K. Green, W. Dean, and W. Reik. 2005. Epigenetic reprogramming in mammals. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14(Suppl.):R47–R58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, J., B. Zevnik, K. Anastassiadis, H. Niwa, D. Klewe-Nebenius, I. Chambers, H. Scholer, and A. Smith. 1998. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell. 95:379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederreither, K., E. Remboutsika, A. Gansmuller, R. Losson, and P. Dolle. 1999. Expression of the transcriptional intermediary factor TIF1alpha during mouse development and in the reproductive organs. Mech. Dev. 88:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, A.L., J.A. Ortiz, J. You, M. Oulad-Abdelghani, R. Khechumian, A. Gansmuller, P. Chambon, and R. Losson. 1999. Interaction with members of the heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) family and histone deacetylation are differentially involved in transcriptional silencing by members of the TIF1 family. EMBO J. 18:6385–6395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberley, M.J., D.R. Inman, and P.J. Farnham. 2003. E2F6 negatively regulates BRCA1 in human cancer cells without methylation of histone H3 on lysine 9. J. Biol. Chem. 278:42466–42476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal, S., R. Yun, A. Datta, L. Lacomis, H. Erdjument-Bromage, J. Kumar, P. Tempst, and S. Sif. 2003. mSin3A/histone deacetylase 2- and PRMT5-containing Brg1 complex is involved in transcriptional repression of the Myc target gene cad. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:7475–7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal, S., S.N. Vishwanath, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, and S. Sif. 2004. Human SWI/SNF-associated PRMT5 methylates histone H3 arginine 8 and negatively regulates expression of ST7 and NM23 tumor suppressor genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:9630–9645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H., I. Feldman, and F.J. Rauscher III. 2002. Hetero-oligomerization among the TIF family of RBCC/TRIM domain-containing nuclear cofactors: a potential mechanism for regulating the switch between coactivation and corepression. J. Mol. Biol. 320:629–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remboutsika, E., Y. Lutz, A. Gansmuller, J.L. Vonesch, R. Losson, and P. Chambon. 1999. The putative nuclear receptor mediator TIF1alpha is tightly associated with euchromatin. J. Cell Sci. 112:1671–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remboutsika, E., K. Yamamoto, M. Harbers, and M. Schmutz. 2002. The bromodomain mediates transcriptional intermediary factor 1alpha-nucleosome interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 277:50318–50325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymond, A., G. Meroni, A. Fantozzi, G. Merla, S. Cairo, L. Luzi, D. Riganelli, E. Zanaria, S. Messali, S. Cainarca, et al. 2001. The tripartite motif family identifies cell compartments. EMBO J. 20:2140–2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, D.C., J.R. Friedman, and F.J. Rauscher III. 2001. Targeting histone deacetylase complexes via KRAB-zinc finger proteins: the PHD and bromodomains of KAP-1 form a cooperative unit that recruits a novel isoform of the Mi-2alpha subunit of NuRD. Genes Dev. 15:428–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, R.M. 2002. The molecular foundations of the maternal to zygotic transition in the preimplantation embryo. Hum. Reprod. Update. 8:323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopka, T., and A.I. Skoultchi. 2003. The ISWI ATPase Snf2h is required for early mouse development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:14097–14102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temeles, G.L., P.T. Ram, J.L. Rothstein, and R.M. Schultz. 1994. Expression patterns of novel genes during mouse preimplantation embryogenesis. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 37:121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teyssier, C., C.Y. Ou, K. Khetchoumian, R. Losson, and M.R. Stallcup. 2005. Transcriptional intermediary factor 1α mediates physical interaction and functional synergy between the coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 and glucocorticoid receptor-interacting protein 1 nuclear receptor coactivators. Mol. Endocrinol. 20:1276–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E.M., E. Legouy, and J.P. Renard. 1998. Mouse embryos do not wait for the MBT: chromatin and RNA polymerase remodeling in genome activation at the onset of development. Dev. Genet. 22:31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venturini, L., J. You, M. Stadler, R. Galien, V. Lallemand, M.H. Koken, M.G. Mattei, A. Ganser, P. Chambon, R. Losson, and H. de The. 1999. TIF1gamma, a novel member of the transcriptional intermediary factor 1 family. Oncogene. 18:1209–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.T., K. Piotrowska, M.A. Ciemerych, L. Milenkovic, M.P. Scott, R.W. Davis, and M. Zernicka-Goetz. 2004. A genome-wide study of gene activity reveals developmental signaling pathways in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Dev. Cell. 6:133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wianny, F., and M. Zernicka-Goetz. 2000. Specific interference with gene function by double-stranded RNA in early mouse development. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, D.G., S. Bhatt, and B.G. Herrmann. 1990. Expression pattern of the mouse T gene and its role in mesoderm formation. Nature. 343:657–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zernicka-Goetz, M., and J. Pines. 2001. Use of green fluorescent protein in mouse embryos. Methods. 24:55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]