Abstract

Mammalian cells increase transcription of genes for adaptation to hypoxia through the stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) protein. How cells transduce hypoxic signals to stabilize the HIF-1α protein remains unresolved. We demonstrate that cells deficient in the complex III subunit cytochrome b, which are respiratory incompetent, increase ROS levels and stabilize the HIF-1α protein during hypoxia. RNA interference of the complex III subunit Rieske iron sulfur protein in the cytochrome b–null cells and treatment of wild-type cells with stigmatellin abolished reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation at the Qo site of complex III. These interventions maintained hydroxylation of HIF-1α protein and prevented stabilization of HIF-1α protein during hypoxia. Antioxidants maintained hydroxylation of HIF-1α protein and prevented stabilization of HIF-1α protein during hypoxia. Exogenous hydrogen peroxide under normoxia prevented hydroxylation of HIF-1α protein and stabilized HIF-1α protein. These results provide genetic and pharmacologic evidence that the Qo site of complex III is required for the transduction of hypoxic signal by releasing ROS to stabilize the HIF-1α protein.

Introduction

Oxygen homeostasis is important for normal cellular function (Semenza, 2000). As oxygen levels decrease in the surrounding environment (hypoxia), cells respond by activating hypoxia- inducible factor (HIF) dependent gene transcription to facilitate cellular adaptation to hypoxia. HIF is a heterodimer of two basic helix-loop-helix/Per/Arnt/Sim domain proteins, HIF-α and the aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator (ARNT or HIF-β; Wang et al., 1995). Under normal oxygen conditions, ARNT is constitutively stable, whereas the α subunit is labile. In normal oxygen conditions, the α subunit is hydroxylated at proline residues by a family of prolyl hydroxylase enzymes (PHDs). Proline hydroxylation targets the protein for ubiquitination by the von Hippel-Lindau protein (pVHL)/E3 ubiquitin ligase and for subsequent proteasomal degradation (Maxwell et al., 1999; Bruick and McKnight, 2001; Epstein et al., 2001; Ivan et al., 2001; Jaakkola et al., 2001). The α subunit is also hydroxylated at an asparagine residue by the enzyme factor inhibiting HIF-1 (FIH-1) under normal oxygen conditions (Mahon et al., 2001; Lando et al., 2002a,b). Asparagine hydroxylation blocks the binding of the transcriptional coactivators p300 and CREB binding protein (CBP) to HIF-1 (Dames et al., 2002; Freedman et al., 2002). Under hypoxic conditions, the α subunit is not hydroxylated by the PHDs or FIH, resulting in the stabilization of the HIF-α protein, dimerization with ARNT, and association with p300/CBP to initiate gene transcription.

The mechanism by which cells transduce the hypoxic signal to activate HIF is a subject of ongoing research. Previous studies indicate that mitochondria are involved in the transduction of hypoxic signals; however, the mechanism is not fully understood. One model proposes that mitochondria regulate the ability of the PHDs to hydroxylate HIF-1α protein because of their capacity to consume oxygen (Hagen et al., 2003; Doege et al., 2005). Mitochondrial oxygen consumption would generate a gradient of oxygen within the cytosol of the cell, thereby limiting the availability of oxygen, a necessary cosubstrate for PHD activity. Another model proposes that mitochondria increase the levels of cytosolic reactive oxygen species (ROS) during hypoxia to activate HIF (Bell et al., 2005). Initial evidence to support this model came from observations that cells treated with mitochondrial electron transport inhibitors, and cells devoid of mitochondrial DNA (ρ0 cells), fail to activate HIF during hypoxia because of a lack of mitochondrially generated ROS (Chandel et al., 1998, 2000). Recently, three independent studies genetically confirmed the initial finding that mitochondria-generated ROS are required for hypoxic activation of HIF. Cells devoid of the cytochrome c gene do not increase cytosolic ROS or stabilize HIF-1α in hypoxic conditions (Mansfield et al., 2005). Cells with either transient or stable RNAi of the Rieske Fe-S protein, a component of the mitochondrial complex III (the bc1 complex), inhibits hypoxic increase of cytosolic ROS and stabilization of HIF-1α protein (Brunelle et al., 2005; Guzy et al., 2005).

Although these studies indicate that ROS generated within the mitochondrial electron transport chain are required to relay the hypoxic signal, they do not indicate which complex of the electron transport chain is the site of ROS generation. The mitochondrial electron transport chain generates superoxide at complexes I, II, and III (Turrens, 2003). Complexes I and II generate superoxide within the mitochondrial matrix (Turrens and Boveris, 1980; Turrens et al., 1982; Zhang et al., 1998; Genova et al., 2001; Lenaz, 2001; Kushnareva et al., 2002; Paddenberg et al., 2003). Complex III generates superoxide at the Qo site, resulting in the release of superoxide into either the intermembrane space or the matrix (Boveris et al., 1976; Cadenas et al., 1977; Turrens et al., 1985; Han et al., 2001; Starkov and Fiskum, 2001; Muller et al., 2004). Complex IV has not been reported to generate ROS; however, cytochrome c was recently demonstrated to participate in the generation of hydrogen peroxide by providing electrons to p66 Shc (Giorgio et al., 2005). The observations that loss of cytochrome c gene or RNAi of the Rieske Fe-S protein prevent hypoxic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein implicate either complex III or cytochrome c as the source of ROS generation required for hypoxic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein. In the present study, we examined which site within the mitochondrial electron transport chain is required for the generation of ROS and hypoxic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein independently of respiration.

Results

Hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α protein is independent of respiration and cytochrome b

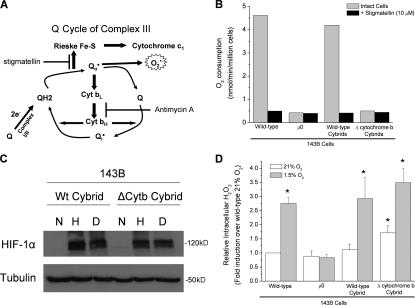

Mitochondrial complex III consists of 11 subunits, three of which have known electron transport activity (the Rieske Fe-S protein, cytochrome b, and cytochrome c 1). The electron flux from ubiquinol (QH2) to cytochrome c occurs through the ubiquinone (Q) cycle within complex III (Hunte et al., 2003). The first electron from ubiquinol is transferred to the Rieske Fe-S/cytochrome c 1/cytochrome c axis transiently, making the radical ubisemiquinone. The second electron from ubisemiquinone is transferred to cytochrome b. However, ubisemiquinone does have the capability of transferring an electron to oxygen to generate superoxide. This allows for the generation of ROS at the Qo site of complex III through the interaction between ubisemiquinone (Q) and molecular oxygen within the bc1 complex (Fig. 1 A). To explore the role of complex III in the stabilization of the HIF-1α protein, we used cells that are deficient in cytochrome b. These cells are cybrids that were generated by repopulating 143Bρ0 cells with mitochondria that contain either a wild-type (WT) mitochondria DNA or a 4-base pair deletion of the cytochrome b gene (Rana et al., 2000). The cytochrome b–deficient cells (ΔCyt b) do not consume oxygen, similar to ρ0 cells (Fig. 1 B). However, the ΔCyt b cybrid cells retain the ability to stabilize HIF-1α protein under hypoxia (Fig. 1 C). These data indicate that the ability of cells to consume oxygen is not related to their ability to stabilize HIF-1α protein.

Figure 1.

Cells that contain a cytochrome b–deficient bc1 complex are respiratory incompetent but still generate ROS and stabilize HIF-1α in hypoxia. (A) Mitochondrial complex III generates ROS through the ubiquinone (Q) cycle. The Q cycle generates ROS at the Qo and Qi site. The Rieske Fe-S protein is required for ROS production at the Qo site. The loss of complex III subunit cytochrome b abolishes the Qi site. (B) Oxygen consumption of 143B cells, 143Bρ0 cells, WT cybrids, and ΔCyt b cybrids with and without 1 μM of the mitochondrial electron transport inhibitor stigmatellin. (C) HIF-1α protein levels in WT and ΔCyt b cybrids subjected to 21% O2 (N), 1.5% O2 (H), or 1 mM DMOG (D) for 4 h. Representative blot from four independent experiments. (D) Intracellular H2O2 levels were measured by Amplex red in 143B cells, 143Bρ0 cells, WT cybrids, and ΔCyt b cybrids exposed to 1.5 or 21% O2 for 4 h. n = 4 (mean ± SEM); *, P < 0.05 (all groups were compared with the normoxia sample of WT cells).

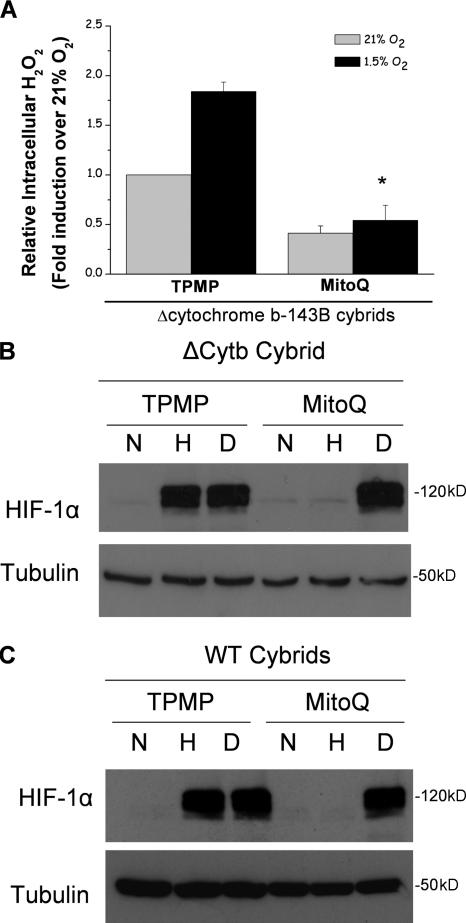

Moreover, under hypoxia, the ΔCyt b cybrids increase H2O2 levels measured in the cytosol using Amplex red (Fig. 1 D). ρ0 cells did not display an increase in ROS in the cytosol during hypoxia, indicating that mitochondria are the major source of ROS production during hypoxia. These data indicate that that the ability of mitochondria to increase cytosolic ROS and stabilize HIF protein in hypoxia is independent of both cytochrome b and oxygen consumption. Additionally, the levels of cytosolic antioxidant proteins Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase and catalase did not change drastically in hypoxic conditions (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200609074/DC1). To determine whether mitochondrial ROS generation was responsible for the increase in cytosolic ROS and stabilization of the HIF-1α protein in the ΔCyt b cybrids, these cells were treated with the mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant MitoQ. MitoQ abolished the increase in cytosolic ROS during hypoxia in the ΔCyt b cybrids (Fig. 2 A). Hypoxic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein was diminished in both WT and ΔCyt b cybrid cell lines treated with MitoQ but not in the presence of dimethyloxalylglycine (DMOG; Fig. 2, B and C). MitoQ diminished stabilization in a dose-dependent manner in both cell types (Fig. S2). These results are corroborated with the observation that EUK-134, a mimetic of both catalase and superoxide dismutase, inhibits hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α protein in both the WT and the ΔCyt b cybrids (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant MitoQ prevents hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α protein. (A) Intracellular H2O2 levels were measured in ΔCyt b cybrids using Amplex red in the presence of 1 μM MitoQ or 1 μM of the control compound TPMP for 4 h. n = 4 (mean ± SEM); *, P < 0.05 (TPMP hypoxia samples compared with MitoQ hypoxia samples). (B and C) HIF-1α protein levels of whole cell lysates from ΔCyt b cybrids (B) and WT cybrids (C) preincubated with 1 μM MitoQ or 1 μM of the control compound TPMP for 4 h and then subjected to 21% O2 (N), 1.5% O2 (H), or 1 mM DMOG (D) for 4 h. Representative blot from four independent experiments.

Figure 3.

Cytosolic antioxidant EUK-143 prevents hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α protein. HIF-1α protein levels of whole cell lysates from WT cybrids (A) and ΔCyt b cybrids (B) preincubated with 10 μM EUK-134 for 2 h and then subjected to 21% O2 (N), 1.5% O2 (H), or 1 mM DMOG (D) for 4 h. Representative blot from three independent experiments.

Hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α protein requires generation of ROS from the Qo site of the mitochondrial complex III

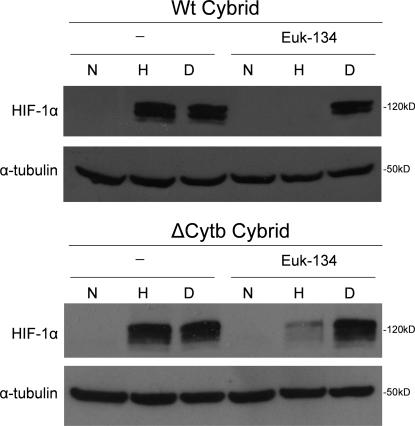

To further validate that the mitochondrial electron transport chain is required for hypoxic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein in the ΔCyt b cybrids, we used short hairpin RNA (shRNA) against the mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM). TFAM is required for the proper transcription and replication of mitochondrial DNA (Ekstrand et al., 2004). In the absence of TFAM, cells become depleted of their mitochondrial DNA (ρ0 cells; Larsson et al., 1998). Expression of TFAM shRNA in the ΔCyt b cybrids lowered TFAM mRNA expression and mitochondrial copy number by 75% compared with cells expressing the control shRNA against Drosophila melanogaster HIF (dHIF; Fig. 4, A and B). The cell containing TFAM shRNA diminished their ability to stabilize HIF-1α protein under hypoxia (Fig. 4 C). These data indicate that mitochondrial electron transport has an important role in hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α protein.

Figure 4.

RNAi of TFAM diminishes hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α protein. Quantitative real-time PCR of cDNA (A) or total DNA (B) generated from ΔCyt b cybrids stably expressing shRNA for D. melanogaster HIF (dHIF) or TFAM. n = 3 (mean ± SEM); *, P < 0.05 (dHIF shRNA compared with TFMA shRNA). (C) HIF-1α protein levels from whole cell lysates of ΔCyt b cybrids stably expressing shRNA for either D. melanogaster HIF (dHIF) or TFAM, exposed to 21% O2 (N), 1.5% O2 (H), or 1 mM DMOG (D) for 4 h. Representative blot from three independent experiments.

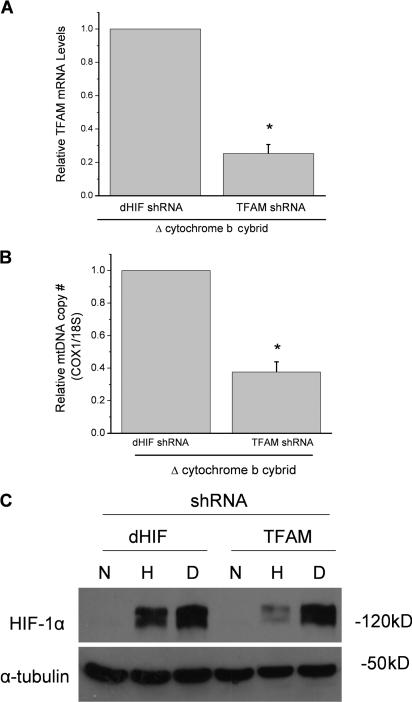

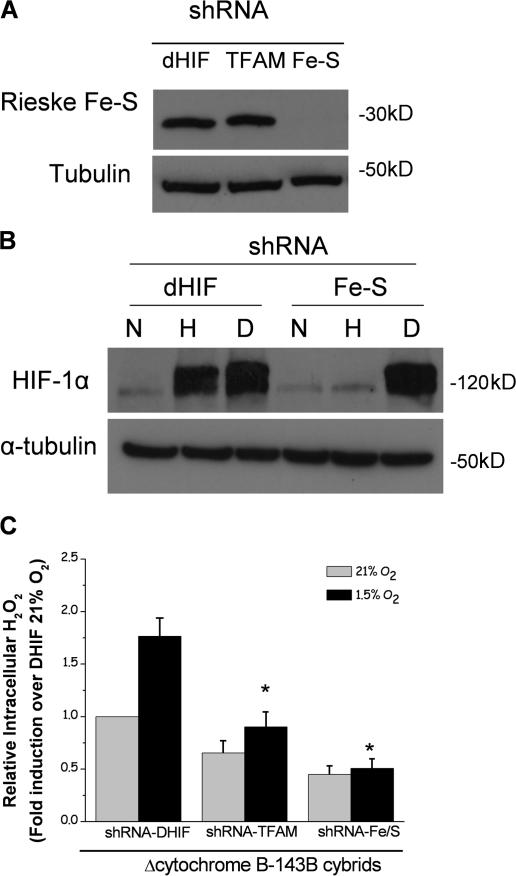

To determine whether ROS generation from the Qo site is responsible for the increase in cytosolic ROS and stabilization of the HIF-1α protein, the ΔCyt b cybrid cells were stably infected with retrovirus containing shRNA against the Rieske Fe-S protein. In the absence of the Rieske Fe-S protein, the Q cycle is not initiated and ROS are not generated at the Qo site. It is theoretically possible that the Qi site might generate ROS. However, activity of the Qi site is abolished in cells deficient in the cytochrome b protein (Fig. 1). Therefore, the data indicate that the Qi site is dispensable for hypoxic increase in cytosolic ROS and stabilization of HIF-1α. Stably expressing a shRNA against the Rieske Fe-S protein in the ΔCyt b cybrid cells decreases expression of the Rieske Fe-S protein (Fig. 5 A). These cells do not stabilize the HIF-1α protein when exposed to hypoxia but retain HIF-1α protein stabilization in the presence of DMOG (Fig. 5 B). As expected, neither the TFAM shRNA cells nor Rieske Fe-S shRNA cells were able to increase cytosolic ROS under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 5 C).

Figure 5.

Electron transfer at the Qo site of the bc1 complex is necessary for hypoxic generation of ROS and stabilization of HIF-1α protein. (A) Immunoblot analysis for Rieske Fe-S protein of whole cell lysates from ΔCyt b cybrids stably expressing shRNA for D. melanogaster HIF (dHIF), TFAM, or Rieske Fe-S protein (FE-S) at 21% O2. (B) HIF-1α protein levels from whole cell lysates of ΔCyt b cybrids stably expressing shRNA against either D. melanogaster HIF (dHIF) or Rieske Fe-S protein (FE-S) exposed to 21% O2 (N), 1.5% O2 (H), or 1 mM DMOG (D) for 4 h. Representative blot from four independent experiments. (C) Intracellular H2O2 levels measured with Amplex red in ΔCyt b cybrids stably expressing shRNA for D. melanogaster HIF, TFAM, or Rieske Fe-S protein exposed to either 21 or 1.5% O2 for 4 h. n = 4 (mean ± SEM); *, P < 0.05 (hypoxic dHIF shRNA compared with hypoxic TFMA shRNA and hypoxic Rieske Fe-S shRNA).

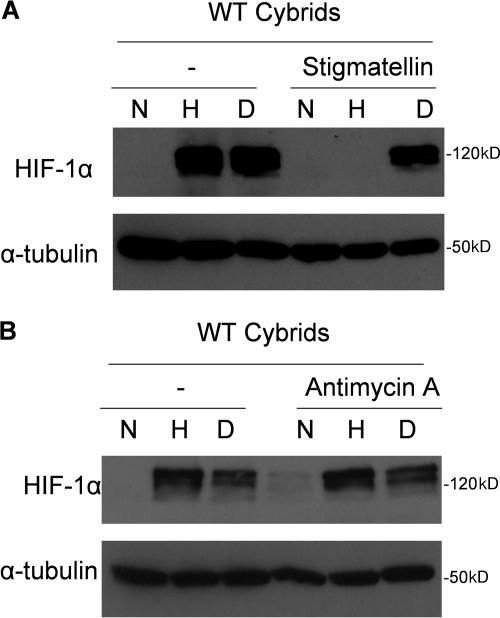

To ensure that our results were not due to any adaptation to the loss of cytochrome b protein or shRNA against Rieske Fe-S protein, we corroborated our genetic findings in WT cells using well-established pharmacological inhibitors of complex III. Incubating WT cells with the complex III inhibitor stigmatellin, which binds to the Qo site, inhibits hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α protein (Fig. 6 A). In contrast, the complex III inhibitor antimycin A, which preserves the ROS generation at the Qo site of complex III, did not decrease hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α in the WT cybrids (Fig. 6 B). Collectively, these data implicate the Qo site of complex III as the primary site of ROS generation for hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α protein.

Figure 6.

Hypoxic HIF-1α protein stability is attenuated by pharmacological inhibitors of the Qo but not Qi site in WT cells. (A) HIF-1α protein levels of whole cell lysates from WT cybrids incubated with 1 μM stigmatellin and subjected to 21% O2 (N), 1.5% O2 (H), or 1 mM DMOG (D) for 4 h. Representative blot from three independent experiments. (B) HIF-1α protein levels of whole cell lysates from WT cybrids incubated with 1 μM antimycin A and subjected to 21% O2 (N), 1.5% O2 (H), or 1 mM DMOG (D) for 4 h. Representative blot from three independent experiments.

ROS regulate hydroxylation of HIF-1α protein

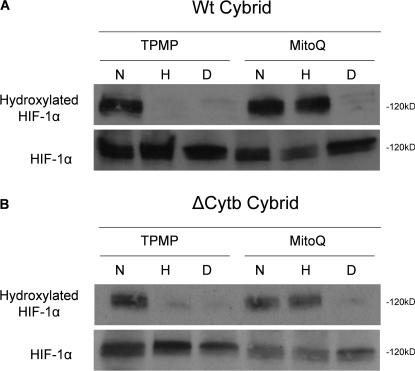

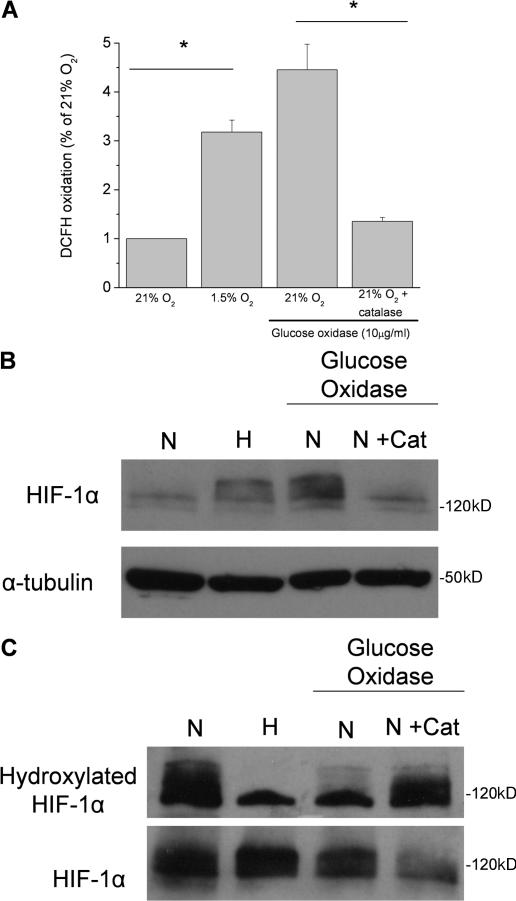

Under normal oxygen conditions, HIF-1α protein is hydroxylated by the PHDs, thereby facilitating ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation. Exogenous ROS are sufficient to stabilize HIF-1α protein under normal oxygen conditions (Chandel et al., 2000). Using an antibody that specifically recognizes HIF-1α protein hydroxylated on proline 564, we demonstrate that ROS inhibit the ability of the PHDs to hydroxylate HIF-1α protein. Quenching the increase in cytosolic ROS under hypoxia with MitoQ recovers hydroxylation of HIF-1α protein in both the WT and ΔCyt b cybrids (Fig. 7). To test whether exogenous ROS are sufficient to prevent hydroxylation of the HIF-1α protein, cells were exposed to glucose oxidase, an enzyme that generates H2O2. Addition of 10 μg/ml glucose oxidase increases intracellular ROS to levels that are similar to those measured in hypoxic conditions (Fig. 8 A). These levels of ROS generated in normal oxygen conditions are sufficient to stabilize HIF-1α protein (Fig. 8 B). Addition of the antioxidant protein catalase in this experiment inhibits stabilization of HIF-1α protein, indicating that H2O2 is responsible for the stabilization of the HIF-1α protein. The presence of glucose oxidase attenuates hydroxylation of HIF-1α protein, as assessed by reactivity with the hydroxylation-specific antibody (Fig. 8 C). The addition of catalase in the presence of glucose oxidase under normal oxygen conditions recovers hydroxylation of HIF-1α protein, indicating that the ability of the PHDs to hydroxylate HIF-1α protein is indeed regulated by ROS.

Figure 7.

Hypoxic increase in cytosolic ROS generated from the Qo site of complex III inhibits hydroxylation of HIF-1α protein. Immunoblot analysis of whole cell lysates for hydroxylated HIF-1α protein from WT cybrids (A) and ΔCyt b cybrids (B) treated with 20 μM MG132 to stabilize HIF-1α protein preincubated with 1 μM MitoQ or 1 μM control compound TPMP for 4 h and then subjected to 21% O2 (N), 1.5% O2 (H), or 1 mM DMOG (D) for 4 h. Representative blot from three independent experiments.

Figure 8.

ROS are sufficient to prevent hydroxylation of HIF-1α protein. (A) Intracellular ROS measured by DCFH in WT cybrids subjected to 21% O2 (N), 1.5% O2 (H), 21% O2 plus glucose oxidase (10 μg/ml), or 21% O2 plus glucose oxidase and catalase for 2 h. n = 4 (mean ± SEM); *, P < 0.05 (normoxia compared with hypoxia or normoxia + glucose oxidase compared with normoxia + glucose oxidase + catalase). (B) Immunoblot analysis of whole cell lysates for HIF-1α protein from WT cybrids subjected to 21% O2 (N), 1.5% O2 (H), 21% O2 plus glucose oxidase, or 21% O2 plus glucose oxidase and catalase for 2 h. Representative blot from three independent experiments. (C) Immunoblot analysis for hydroxylated HIF-1α protein from whole cell lysates of WT cybrids treated with 20 μM MG132 subjected to 21% O2 (N), 1.5% O2 (H), 21% O2 plus glucose oxidase, or 21% O2 plus glucose oxidase and catalase for 2 h. Representative blot from three independent experiments.

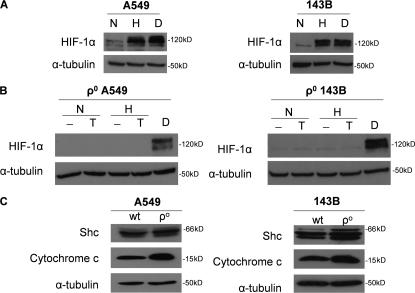

Cytochrome c reduction is not sufficient to stabilize HIF under hypoxia

Previous findings indicate that loss of cytochrome c prevents the hypoxic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein (Mansfield et al., 2005). To determine whether cytochrome c–generated ROS are required for the hypoxic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein, we exposed ρ0 cells to normoxia or hypoxia in the presence of N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (TMPD). ρ0 cells lack a functional complex III and IV, resulting in a loss of electron flux through cytochrome c. TMPD donates electrons to cytochrome c, thereby fully reducing cytochrome c. The electrons from cytochrome c could then be donated to p66 Shc in the absence of a functional complex IV, resulting in ROS generation and HIF stabilization. WT 143B or A549 cells stabilize the HIF-1α protein during hypoxia (1.5% O2) or in the presence of DMOG (Fig. 9 A). In contrast, the 143Bρ0 or A549ρ0 cells do not stabilize HIF-1α protein during hypoxia. The addition of TMPD to either 143Bρ0 or A549ρ0 cells also did not stabilize the HIF-1α protein under normoxia (21% O2) or hypoxia (1.5% O2; Fig. 9 B). This was not due to reduced levels of p66Shc or cytochrome c in the ρ0 cells (Fig. 9 C). TMPD did reduce cytochrome c, and under these conditions it did not generate ROS (Fig. S3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200609074/DC1). Previous results indicate that ROS due to electron transfer between cytochrome c and p66shc is observed only during DNA damage and may not be the normal physiological response in healthy cells (Giorgio et al., 2005). These results indicate that reduction of cytochrome c is not sufficient for hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α protein.

Figure 9.

Reduced cytochrome c is not sufficient to stabilize the HIF-1α protein. (A) HIF-1α protein levels of 143B and A549 cells subjected to 21% O2 (N), 1.5% O2 (H), and 1 mM DMOG (D) for 2 h. Representative blot from three independent experiments. (B) HIF-1α protein levels of 143Bρ0 and A549ρ0 whole cell lysates <21% O2 (N) or 1.5% O2 (H) for 2 h after a 15-min pulse of 100 μM of the cytochrome c–reducing agent TMPD and 400 μM ascorbate (T) or 1 mM DMOG (D). Representative blot from three independent experiments. (C) Cytochrome c and p66Shc protein levels in 143Bρ0 and A549ρ0 whole cell lysates. Representative blot from three independent experiments.

Discussion

Mammalian cells transduce signals that couple decreases in oxygen levels to initiate HIF-dependent gene expression. The mechanism of how cells transduce hypoxic signals is not fully understood. Mitochondrial electron transport chain has been proposed as part of the hypoxic signal transduction machinery. Indeed, previous genetic evidence indicates that loss of cytochrome c or the Rieske Fe-S protein prevents the hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α, indicating that these proteins are involved in the increase in cytosolic ROS during hypoxia (Brunelle et al., 2005; Guzy et al., 2005; Mansfield et al., 2005). RNAi of the Rieske Fe-S protein or loss of cytochrome c prevents the formation of ubisemiquinone, thus preventing ROS generation at the Qo site of complex III. The loss of cytochrome c or RNAi of Rieske Fe-S protein would also not cause a reduction in cytochrome c, thereby preventing cytochrome c–dependent ROS generation. In the present study, we demonstrate that cytochrome c is not the primary site of ROS generation in hypoxia. We demonstrate that fully reducing cytochrome c levels is not sufficient to stabilize the HIF-1α protein during hypoxia or normoxia. Therefore, cytochrome c does not contribute to hypoxic signal transduction through its ability to generate ROS via p66Shc.

Our data indicate that the Qo site of complex III is part of the hypoxic signal transduction machinery. Cells deficient in cytochrome b protein are able to generate ROS at the Qo site of complex III. During hypoxia, these cells stabilize the HIF-1α protein. Preventing ROS generation at the Qo site in the cytochrome b–deficient cells with MitoQ or by shRNA against the Rieske Fe-S protein prevents the increase in cytosolic ROS and stabilization of the HIF-1α protein during hypoxia. The present data also demonstrate that ROS regulate the ability of the PHDs to hydroxylate HIF in both normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Quenching ROS with MitoQ in hypoxic conditions allows for continued hydroxylation of HIF-1α protein, whereas addition of exogenous ROS in normal oxygen conditions inhibits the ability of the PHDs to hydroxylate HIF-1α protein. These data suggest that the Qo site of the bc1 complex participates in hypoxic signal transduction via ROS generation to initiate HIF-mediated transcriptional responses that facilitate cellular adaptation to low oxygen.

The present data are in contrast with other groups that have proposed that the ability of mitochondria to consume oxygen is the major requirement for stabilization of the HIF-1α protein in hypoxic conditions. Their model proposes that respiring mitochondria generate an oxygen gradient, preventing hydroxylation, and thereby increasing stabilization of the HIF-1α protein (Hagen et al., 2003; Doege et al., 2005). According to this model, in the absence of a functioning respiratory chain, the oxygen gradient would be reduced, resulting in hydroxylation and degradation of the HIF-1α protein. However, the cytochrome b–null cells are respiratory incompetent and therefore unable to generate an oxygen gradient. Contrary to this model, these cells still retain the ability to stabilize the HIF-1α protein during hypoxia. Furthermore, the mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant MitoQ or the cytosolic antioxidant EUK-134 prevents stabilization of the HIF-1α protein in the cytochrome b–deficient cells, indicating ROS involvement in HIF stabilization. MitoQ has been shown to prevent hypoxic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein in respiratory-competent cells, demonstrating the importance of ROS in HIF-1α protein stabilization (Sanjuan-Pla et al., 2005). However, there are instances when an oxygen gradient created by the mitochondria during normoxia can create a hypoxic environment within cells, causing HIF-1α protein accumulation (Doege et al., 2005). For example, if metabolically active cells are cultured at high confluency, their demand for oxygen exceeds the supply of oxygen, resulting in a local hypoxia. Under these conditions, respiratory inhibition would result in restoration of the oxygen levels to normoxia within the cells, resulting in the degradation of the HIF-1α protein. Cells that are cultured at a high confluency under hypoxia (1–2% O2) would experience anoxia (0% O2). Under these conditions, respiratory inhibition would result in restoration of oxygen levels only to the hypoxic levels. If respiratory inhibition does not result in attenuating ROS generation, such as in the cytochrome b–deficient cells, then cells would still be able to stabilize the HIF-1α protein in conditions of high confluency under hypoxia. Collectively, our data indicate that the ability of mitochondria to generate ROS and not an oxygen gradient is required for the stabilization of the HIF-1α protein during hypoxia.

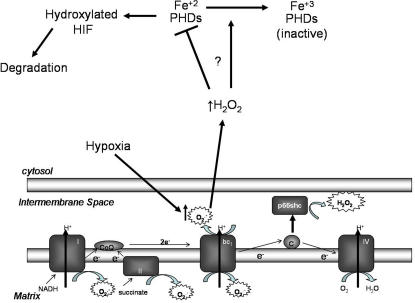

In summary, we demonstrate that the Qo site of complex III is necessary to increase cytosolic ROS in hypoxic conditions, which results in the inhibition of the ability of the PHDs to initiate degradation of HIF-1α protein (Fig. 10). We also conclusively demonstrate that the ability to consume oxygen by mitochondria is not required for hypoxic stabilization of the HIF-1α protein. The link between ROS and the PHDs is currently unknown. As oxygen levels fall, the enzymatic activity of PHDs decrease (Schofield and Ratcliffe, 2004). It is possible that the link could be an oxidant-dependent signaling pathway in which a posttranslational modification of the PHDs, such as phosphorylation, turns off the catalytic activity. In fact previous studies have implicated multiple signaling molecules that are required for hypoxic activation of HIF-1 (Aragones et al., 2001; Hirota and Semenza, 2001; Turcotte et al., 2003; Emerling et al., 2005; Hui et al., 2006). Alternatively, the link between ROS and the PHDs could be due to changes in the cytosolic redox state. The ROS may induce a shift in iron redox state from Fe+2 to Fe+3 as a result of the Fenton reaction, thereby limiting an essential cofactor of the PHDs, resulting in an inhibition of hydroxylation of HIF protein (Gerald et al., 2004). It could also be that the low oxygen levels decrease PHD activity and the ROS produced during hypoxia further decrease PHD activity to prevent hydroxylation of HIF-α protein. Furthermore, multiple factors affecting cellular redox state and metabolism are likely to affect hydroxylation of the HIF-1α protein (Pan et al., 2006). Our study also suggests that the targeting of mitochondrial ROS could serve as a therapeutic target for many HIF-dependent pathological processes, including cancer. It will be of interest in future studies to examine whether the Qo site of complex III serves as part of a signal transduction machinery for other hypoxia-initiated cellular events, such as calcium signaling.

Figure 10.

Schematic model of mitochondrial-generated ROS stabilization of HIF-1α in hypoxic conditions. Hypoxia increases generation of ROS from the Qo site of the bc1 complex. These ROS are released into the intermembrane space and enter the cytosol to decrease PHD activity, thus preventing hydroxylation of the HIF-1α protein. We speculate that ROS decrease the PHD activity from a combination of a posttranslational modification of the PHDs, such as phosphorylation or decreasing the availability of Fe (II), which is required for hydroxylation to occur.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

WT A549 and 143B cells were cultured in DME, whereas the ρ0 derivatives were cultured in DME supplemented with 100 μg/ml uridine. The ρ0 derivatives were made as previously described (Brunelle et al., 2005). The WT and ΔCyt b 143B cybrid cells (provided by I.F.M. de Coo, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, Rotterdam, Netherlands) were previously described by Rana et al. (2000) and were cultured in DME supplemented with 100 μg/ml uridine. Cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 humidified incubators for normoxic conditions. Hypoxic conditions (1.5% O2) were achieved in the humidified variable aerobic workstation InVivo2 (Biotrace). Glucose oxidase, catalase, stigmatellin, and antimycin A were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

RNAi in cytochrome b–null cells

The pSiren retroviral vector (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.) was used to express shRNA sequences for the Rieske Fe-S (5′-AAGGTGCCTGACTTCTCTGAA -3′), TFAM (5′-GTTGTCCAAAGAAACCTGT-3′), and D. melanogaster HIF (5′-GCCTACATCCCGATCGATGATG-3′). Stable lines were generated using retroviral infection methods with the PT67 packaging cell line (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc.).

ROS measurement

Intracellular ROS was measured using Amplex red (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's protocol. In brief, cells were lysed in 100 μM Amplex red solution supplemented with 2 U/ml HRP and 200 mU/ml superoxide dismutase (OXIS International) and incubated in the dark for 30 min. Fluorescence was measured in a plate reader (SpectraMax Gemini; Molecular Devices) with excitation of 540 nm and emission of 590 nm. Alternatively, ROS were measured using 10 μM of the oxidant-sensitive fluorescent probe 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate acetyl ester (CM-H2DCFDA; Invitrogen). Cells were plated at equal density in 60-mm plates. The next day, cells were incubated continuously with CM-H2DCFDA for 2 h and exposed to different experimental conditions. Subsequently, cells were washed and lysed in 0.1% Triton X-100. Fluorescence was measured in the SpectraMax Gemini plate reader with excitation of 488 nm and emission of 530 nm.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the Aurum Mini kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and cDNA was generated using the RNAqueous-4PCR system (Ambion) according to manufacturer's protocol. Prepared cDNA was analyzed for TFAM mRNA using SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Cycle threshold (Ct) values for TFAM were normalized to Ct values for ribosomal protein L19, and data were analyzed using the Pfaffl (2001) method. Primers used were as follows: TFAM, 5′-AAGATTCCAAGAAGCTAAGGGTGA-3′ and 5′-CAGAGTCAGACAGATTTTTCCAGTTT-3′; and RPL19, 5′-GTATGCTCAGGCTTCAGAAGA-3′ and 5′-CATTGGTCTCATTGGGGTCTAAC-3′.

Immunoblotting

Protein levels were analyzed in whole cell lysates obtained using lysis buffer (Cell Signaling), and 50 μg of samples were resolved on a SDS polyacrylamide gel. Gels were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies for HIF-1α, cytochrome c, p66Shc (BD Biosciences), Rieske Iron Sulfur protein (Invitrogen), and hydroxylated HIF-1α (a gift from P. Ratcliffe, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK), and α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a loading control.

Oxygen consumption

Cellular O2 consumption rates were measured in aliquots of 1–3 × 106 subconfluent cells removed from flasks and studied in a magnetically stirred, water-jacketed (37°C) anaerobic respirometer fitted with a polarographic O2 electrode (Oxytherm system; Hansatech Instruments). Oxygraph Plus software was used to determine oxygen consumption rate.

Mitochondrial copy number assay

The number of mitochondria was determined by analyzing the abundance of the mitochondrial DNA encoded gene cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (COX1) relative to the nuclear gene 18S. Total DNA was isolated using the DNEasy Tissue kit (QIAGEN). 10 ng of total DNA was subjected to quantitative Real-Time PCR using Sybr Green Chemistry. Primers used were as follows: 18S forward, 5′-ACAGGATTGACAGATTGATAGCTC-3′; 18S reverse, 5′-CAAATCGCTCCACCAACTAAGAA-3′; COX1 forward, 5′-CCCACCGGCGTCAAAGTATT-3′; and COX1 reverse, 5′-TTTGCTAATA- CAATGCCAGTCAGG-3′.

Statistical analysis

The data presented are means ± SEM. Data were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance using Graph Pad Prism 4. When the analysis of variance indicated a significant difference, individual differences were explored with paired t test. Statistical significance was determined at the 0.05 level.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows antioxidant protein profile of whole cell lysates from WT cybrids and ΔCyt b cybrids subjected to either 21% O2 (N) or 1.5% O2 (H) for 4 h. Fig. S2 shows HIF-1α protein levels in WT and ΔCyt b cybrids subjected to 21% O2 (N), 1.5% O2 (H), or 1 mM DMOG (D) for 4 h at various concentrations of MitoQ. Fig. S3 shows ρ0 cells treated with TMPD/ascorbate for 15 min and then subjected to either 21 or 1.5% O2; cytochrome redox state in isolated mitochondria or ROS measurement via DCFH oxidation was then assessed in whole cells. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200609074/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. IFM de Coo for the original cytochrome b mutant fibroblasts and to Dr. Peter Ratcliffe for the hydroxylation antibody.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants (GM60472-07, CA123067-01, and 1P01HL071643-01A10004) to Navdeep S. Chandel. Eric Bell is supported by American Heart Association Grant (0515563Z).

Abbreviations used in this paper: DMOG, dimethyloxalylglycine; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; PHD, prolyl hydroxylase enzyme; ROS, reactive oxygen species; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; TFAM, mitochondrial transcription factor A; TMPD, N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine; WT, wild-type.

References

- Aragones, J., D.R. Jones, S. Martin, M.A. San Juan, A. Alfranca, F. Vidal, A. Vara, I. Merida, and M.O. Landazuri. 2001. Evidence for the involvement of diacylglycerol kinase in the activation of hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1 by low oxygen tension. J. Biol. Chem. 276:10548–10555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, E.L., B.M. Emerling, and N.S. Chandel. 2005. Mitochondrial regulation of oxygen sensing. Mitochondrion. 5:322–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boveris, A., E. Cadenas, and A.O. Stoppani. 1976. Role of ubiquinone in the mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. Biochem. J. 156:435–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruick, R.K., and S.L. McKnight. 2001. A conserved family of prolyl-4- hydroxylases that modify HIF. Science. 294:1337–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelle, J.K., E.L. Bell, N.M. Quesada, K. Vercauteren, V. Tiranti, M. Zeviani, R.C. Scarpulla, and N.S. Chandel. 2005. Oxygen sensing requires mitochondrial ROS but not oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 1:409–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenas, E., A. Boveris, C.I. Ragan, and A.O. Stoppani. 1977. Production of superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide by NADH-ubiquinone reductase and ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase from beef-heart mitochondria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 180:248–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel, N.S., E. Maltepe, E. Goldwasser, C.E. Mathieu, M.C. Simon, and P.T. Schumacker. 1998. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species trigger hypoxia-induced transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:11715–11720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel, N.S., D.S. McClintock, C.E. Feliciano, T.M. Wood, J.A. Melendez, A.M. Rodriguez, and P.T. Schumacker. 2000. Reactive oxygen species generated at mitochondrial complex III stabilize hypoxia-inducible factor-1α during hypoxia: a mechanism of O2 sensing. J. Biol. Chem. 275:25130–25138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dames, S.A., M. Martinez-Yamout, R.N. De Guzman, H.J. Dyson, and P.E. Wright. 2002. Structural basis for Hif-1α/CBP recognition in the cellular hypoxic response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:5271–5276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doege, K., S. Heine, I. Jensen, W. Jelkmann, and E. Metzen. 2005. Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration elevates oxygen concentration but leaves regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) intact. Blood. 106:2311–2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand, M.I., M. Falkenberg, A. Rantanen, C.B. Park, M. Gaspari, K. Hultenby, P. Rustin, C.M. Gustafsson, and N.G. Larsson. 2004. Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mtDNA copy number in mammals. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13:935–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerling, B.M., L.C. Platanias, E. Black, A.R. Nebreda, R.J. Davis, and N.S. Chandel. 2005. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for hypoxia signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:4853–4862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, A.C., J.M. Gleadle, L.A. McNeill, K.S. Hewitson, J. O'Rourke, D.R. Mole, M. Mukherji, E. Metzen, M.I. Wilson, A. Dhanda, et al. 2001. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell. 107:43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, S.J., Z.Y. Sun, F. Poy, A.L. Kung, D.M. Livingston, G. Wagner, and M.J. Eck. 2002. Structural basis for recruitment of CBP/p300 by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:5367–5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genova, M.L., B. Ventura, G. Giuliano, C. Bovina, G. Formiggini, G. Parenti Castelli, and G. Lenaz. 2001. The site of production of superoxide radical in mitochondrial complex I is not a bound ubisemiquinone but presumably iron-sulfur cluster N2. FEBS Lett. 505:364–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerald, D., E. Berra, Y.M. Frapart, D.A. Chan, A.J. Giaccia, D. Mansuy, J. Pouyssegur, M. Yaniv, and F. Mechta-Grigoriou. 2004. JunD reduces tumor angiogenesis by protecting cells from oxidative stress. Cell. 118:781–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgio, M., E. Migliaccio, F. Orsini, D. Paolucci, M. Moroni, C. Contursi, G. Pelliccia, L. Luzi, S. Minucci, M. Marcaccio, et al. 2005. Electron transfer between cytochrome c and p66Shc generates reactive oxygen species that trigger mitochondrial apoptosis. Cell. 122:221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzy, R.D., B. Hoyos, E. Robin, H. Chen, L. Liu, K.D. Mansfield, M.C. Simon, U. Hammerling, and P.T. Schumacker. 2005. Mitochondrial complex III is required for hypoxia-induced ROS production and cellular oxygen sensing. Cell Metab. 1:401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen, T., C.T. Taylor, F. Lam, and S. Moncada. 2003. Redistribution of intracellular oxygen in hypoxia by nitric oxide: effect on HIF1alpha. Science. 302:1975–1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, D., E. Williams, and E. Cadenas. 2001. Mitochondrial respiratory chain-dependent generation of superoxide anion and its release into the intermembrane space. Biochem. J. 353:411–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, K., and G.L. Semenza. 2001. Rac1 activity is required for the activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J. Biol. Chem. 276:21166–21172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui, A.S., A.L. Bauer, J.B. Striet, P.O. Schnell, and M.F. Czyzyk-Krzeska. 2006. Calcium signaling stimulates translation of HIF-α during hypoxia. FASEB J. 20:466–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunte, C., H. Palsdottir, and B.L. Trumpower. 2003. Protonmotive pathways and mechanisms in the cytochrome bc1 complex. FEBS Lett. 545:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivan, M., K. Kondo, H. Yang, W. Kim, J. Valiando, M. Ohh, A. Salic, J.M. Asara, W.S. Lane, and W.G. Kaelin Jr. 2001. HIFα targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science. 292:464–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola, P., D.R. Mole, Y.M. Tian, M.I. Wilson, J. Gielbert, S.J. Gaskell, A. Kriegsheim, H.F. Hebestreit, M. Mukherji, C.J. Schofield, et al. 2001. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science. 292:468–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnareva, Y., A.N. Murphy, and A. Andreyev. 2002. Complex I-mediated reactive oxygen species generation: modulation by cytochrome c and NAD(P)+ oxidation-reduction state. Biochem. J. 368:545–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lando, D., D.J. Peet, J.J. Gorman, D.A. Whelan, M.L. Whitelaw, and R.K. Bruick. 2002. a. FIH-1 is an asparaginyl hydroxylase enzyme that regulates the transcriptional activity of hypoxia-inducible factor. Genes Dev. 16:1466–1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lando, D., D.J. Peet, D.A. Whelan, J.J. Gorman, and M.L. Whitelaw. 2002. b. Asparagine hydroxylation of the HIF transactivation domain a hypoxic switch. Science. 295:858–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, N.G., J. Wang, H. Wilhelmsson, A. Oldfors, P. Rustin, M. Lewandoski, G.S. Barsh, and D.A. Clayton. 1998. Mitochondrial transcription factor A is necessary for mtDNA maintenance and embryogenesis in mice. Nat. Genet. 18:231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenaz, G. 2001. The mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species: mechanisms and implications in human pathology. IUBMB Life. 52:159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon, P.C., K. Hirota, and G.L. Semenza. 2001. FIH-1: a novel protein that interacts with HIF-1alpha and VHL to mediate repression of HIF-1 transcriptional activity. Genes Dev. 15:2675–2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, K.D., R.D. Guzy, Y. Pan, R.M. Young, T.P. Cash, P.T. Schumacker, and M.C. Simon. 2005. Mitochondrial dysfunction resulting from loss of cytochrome c impairs cellular oxygen sensing and hypoxic HIF-α activation. Cell Metab. 1:393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, P.H., M.S. Wiesener, G.W. Chang, S.C. Clifford, E.C. Vaux, M.E. Cockman, C.C. Wykoff, C.W. Pugh, E.R. Maher, and P.J. Ratcliffe. 1999. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature. 399:271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, F.L., Y. Liu, and H. Van Remmen. 2004. Complex III releases superoxide to both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 279:49064–49073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddenberg, R., B. Ishaq, A. Goldenberg, P. Faulhammer, F. Rose, N. Weissmann, R.C. Braun-Dullaeus, and W. Kummer. 2003. Essential role of complex II of the respiratory chain in hypoxia-induced ROS generation in the pulmonary vasculature. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 284:L710–L719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y., K.D. Mansfield, C.C. Bertozzi, V. Rudenko, D.A. Chan, A.J. Giaccia, and M.C. Simon. 2006. Multiple factors affecting cellular redox status and energy metabolism modulate HIF prolyl hydroxylase activity in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:912–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl, M.W. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana, M., I. de Coo, F. Diaz, H. Smeets, and C.T. Moraes. 2000. An out-of-frame cytochrome b gene deletion from a patient with parkinsonism is associated with impaired complex III assembly and an increase in free radical production. Ann. Neurol. 48:774–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjuan-Pla, A., A.M. Cervera, N. Apostolova, R. Garcia-Bou, V.M. Victor, M.P. Murphy, and K.J. McCreath. 2005. A targeted antioxidant reveals the importance of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in the hypoxic signaling of HIF-1α. FEBS Lett. 579:2669–2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, C.J., and P.J. Ratcliffe. 2004. Oxygen sensing by HIF hydroxylases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:343–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza, G.L. 2000. HIF-1 and human disease: one highly involved factor. Genes Dev. 14:1983–1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkov, A.A., and G. Fiskum. 2001. Myxothiazol induces H2O2 production from mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 281:645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcotte, S., R.R. Desrosiers, and R. Beliveau. 2003. HIF-1alpha mRNA and protein upregulation involves Rho GTPase expression during hypoxia in renal cell carcinoma. J. Cell Sci. 116:2247–2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrens, J.F. 2003. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J. Physiol. 552:335–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrens, J.F., and A. Boveris. 1980. Generation of superoxide anion by the NADH dehydrogenase of bovine heart mitochondria. Biochem. J. 191:421–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrens, J.F., B.A. Freeman, J.G. Levitt, and J.D. Crapo. 1982. The effect of hyperoxia on superoxide production by lung submitochondrial particles. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 217:401–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrens, J.F., A. Alexandre, and A.L. Lehninger. 1985. Ubisemiquinone is the electron donor for superoxide formation by complex III of heart mitochondria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 237:408–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.L., B.H. Jiang, E.A. Rue, and G.L. Semenza. 1995. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:5510–5514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., L. Yu, and C.A. Yu. 1998. Generation of superoxide anion by succinate-cytochrome c reductase from bovine heart mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 273:33972–33976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.