Abstract

The neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) regulates synapse formation and synaptic strength via mechanisms that have remained unknown. We show that NCAM associates with the postsynaptic spectrin-based scaffold, cross-linking NCAM with the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II α (CaMKIIα) in a manner not firmly or directly linked to PSD95 and α-actinin. Clustering of NCAM promotes formation of detergent-insoluble complexes enriched in postsynaptic proteins and resembling postsynaptic densities. Disruption of the NCAM–spectrin complex decreases the size of postsynaptic densities and reduces synaptic targeting of NCAM–spectrin–associated postsynaptic proteins, including spectrin, NMDA receptors, and CaMKIIα. Degeneration of the spectrin scaffold in NCAM-deficient neurons results in an inability to recruit CaMKIIα to synapses after NMDA receptor activation, which is a critical process in NMDA receptor–dependent long-term potentiation. The combined observations indicate that NCAM promotes assembly of the spectrin-based postsynaptic signaling complex, which is required for activity-associated, long-lasting changes in synaptic strength. Its abnormal function may contribute to the etiology of neuropsychiatric disorders associated with mutations in or abnormal expression of NCAM.

Introduction

At the ultrastructural level, the mature postsynaptic density (PSD) represents a weblike structure composed of filamentous components that hold together the particulate components (Landis and Reese, 1983; Ziff, 1997). The particulate components represent membrane-associated guanylate kinase proteins and signaling molecules, such as the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), whereas the filamentous components are formed by actin and spectrin filaments. The assembly of these components appears to be important for the formation and maintenance of the highly organized PSD. In search of the molecular mechanisms underlying this activity-dependent organization, we show that it is influenced by the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) that associates with the membrane–cytoskeleton linker protein spectrin, which is highly enriched in PSDs (Persohn et al., 1989; Malchiodi- Albedi et al., 1993). The spectrin scaffold is thought to accumulate functionally interactive proteins in many cell types (Pinder and Baines, 2000). In neurons, spectrin binds to the cytoplasmic domains of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunits (Wechsler and Teichberg, 1998) and associates with other cytoskeletal structures, protein kinases, and phosphatases enriched in synapses (De Matteis and Morrow, 2000; Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003; Bodrikov et al., 2005). Spectrin may, thus, serve to accumulate the postsynaptic machinery in PSDs. The mechanisms regulating this accumulation have, however, remained largely unknown.

Spectrin interacts with the intracellular domains of the two major transmembrane isoforms of NCAM, with molecular masses of 140 (NCAM140) and 180 kD (NCAM180; Pollerberg et al., 1986, 1987; Sytnyk et al., 2002; Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003), and may be indirectly linked to the 120-kD GPI-anchored NCAM isoform (NCAM120) via lipid rafts (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). NCAM180, which is the most potent spectrin-binding isoform (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003), is enriched in PSDs (Persohn et al., 1989; Schuster et al., 1998). NCAM is recruited to axodendritic contacts within minutes after initial contact formation and promotes stabilization of the newly formed contacts (Sytnyk et al., 2002, 2004). Reintroduction of NCAM into neurons of NCAM-deficient (NCAM−/−) mice stimulates synapse formation with NCAM-expressing neurons in an NMDA receptor–dependent manner (Dityatev et al., 2004). Moreover, the NMDA receptor–dependent form of long-term potentiation (LTP) is impaired in NCAM−/− mice (Muller et al., 1996; Bukalo et al., 2004) or after application of NCAM antibodies (Luthl et al., 1994). In humans, genetic variations in the NCAM gene have been reported to confer risk factors associated with bipolar affective disorders (Arai et al., 2004), and abnormal levels of NCAM have been found in the brains of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders (Vawter et al., 1999, 2001). Again, the molecular mechanisms underlying NCAM-mediated synaptogenesis and synaptic plasticity are not known.

We show that NCAM promotes accumulation of spectrin in PSDs, and thus assembles the spectrin-based postsynaptic scaffold, recruiting NMDA receptors and CaMKIIα. Assembly of these components is impaired in NCAM−/− mice and reduced in NCAM+/+ synapses by a dominant-negative spectrin fragment containing the NCAM-binding site or when βI spectrin expression is reduced by using siRNA technology. Reduced accumulation of spectrin and NMDA receptors in NCAM−/− PSDs results in an inability to recruit CaMKIIα to synapses in an activity-dependent manner that is required for longer lasting changes in synaptic strength. The combined observations indicate that NCAM promotes assembly and maintenance of the spectrin-based postsynaptic-signaling complex, and thus reveal a hitherto unknown mechanism that contributes to the organization of the PSD in excitatory synapses.

Results

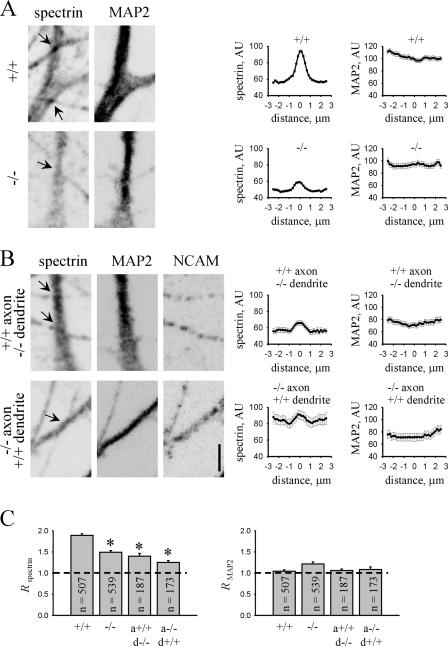

NCAM promotes accumulation of spectrin at axodendritic contacts

Because NCAMs accumulate at interneuronal contacts before their transformation into synapses, we first analyzed whether NCAM recruits spectrin to these contacts, thus transforming them into nascent synapses (Fig. 1). The distribution of spectrin was analyzed in cultured hippocampal neurons along thick, tapering MAP2-positive neurites, identified as dendrites, in the vicinity of contacts formed on the dendrites by thin neurites of a uniform diameter with multiple varicosities, identified as axons. In a separate set of experiments, we found that these thin neurites were positive for the established axonal markers, such as tau, L1, and synaptophysin (Sytnyk et al., 2002). In 4-d-old cultures, synaptophysin had not yet started to accumulate at contact sites (unpublished data), indicating that the immature axodendritic contacts were analyzed before elaboration of the presynaptic vesicle recycling machinery. In NCAM+/+ neurons, contacts accumulated spectrin. The average distribution of spectrin at these contacts was bell-shaped, with a peak in the center of the contact. In contrast, in NCAM−/− neurons, accumulation of spectrin at contacts was reduced. MAP2 was not accumulated at contacts of neurons from NCAM+/+ or NCAM−/− mice and was uniformly distributed in their vicinity.

Figure 1.

NCAM regulates accumulation of spectrin at immature axodendritic contacts. (A and B) NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− neurons maintained in homogenotypic cultures (A) or heterogenotypic coculture (B) for 4 d were labeled with antibodies against spectrin and MAP2. Immunolabeling for NCAM was included for heterogenotypic cultures to identify the genotype of neurons. Immunofluorescence signals were inverted to accentuate the difference in immunolabeling intensities between genotypes. Axodendritic contacts were identified as points of cross section between spectrin- and MAP2-positive dendrites and spectrin-positive and MAP2-negative axons (arrows). Note that spectrin accumulates more efficiently at NCAM+/+ contacts. Bar, 5 μm. Graphs show averaged values of spectrin and MAP2 immunolabeling intensity ± the SEM in arbitrary units (AU). Profiles of spectrin and MAP2 immunolabeling intensity were measured along dendrites with zero on the abscissa, corresponding to the center of the contact and profiles measured along neurites 2.5 μm away from the contact center in both directions. Note that spectrin accumulates at NCAM-positive contacts with a characteristic bell-shaped distribution around the contact center. Accumulation of spectrin at contact sites in which one or both neurites were NCAM negative is reduced. (C) Histograms show R spectrin and R MAP2 for NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− contacts and contacts formed by axons (a) and dendrites (d) of different genotypes. R is defined as the ratio of labeling intensities at the center of a contact and 2.5 μm away from the contact center. Mean values ± the SEM are shown. The number of analyzed contacts (n) is shown for each bar. Asterisks show statistically significant differences when compared with NCAM+/+ contacts; P < 0.05, t test.

The expression of spectrin has been shown to be decreased in adult NCAM−/− brains (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003), a phenomenon that may at least partially explain the reduced accumulation of spectrin in contact sites between NCAM−/− neurons. To investigate whether NCAM recruits spectrin to contact sites, we analyzed the ratio (designated hereafter as R) of spectrin-labeling intensities at the center of a contact and 2.5 μm away from the contact center, a parameter that describes the extent of spectrin accumulation at the contact site and that is independent of spectrin expression levels. R spectrin was reduced at contacts between NCAM−/− neurons (Fig. 1). Moreover, the percentage of contacts accumulating spectrin and defined as contacts with R > 1.5 was also reduced in NCAM−/− neurons (63.5% in NCAM+/+ neurons and 34.3% in NCAM−/− neurons), indicating that NCAM is required to recruit spectrin to axodendritic contacts.

To confirm this and analyze whether homophilic transinteractions of NCAM are important for spectrin accumulation at axodendritic contacts, we analyzed contacts formed between NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− neurons in coculture (Fig. 1; Sytnyk et al., 2002). The distribution of spectrin was then analyzed along dendrites of NCAM+/+ neurons in the vicinity of contacts formed by NCAM−/− axons or along dendrites of NCAM−/− neurons in the vicinity of contacts formed by NCAM+/+ axons. For this type of contact, which we hereafter call heterogenotypic contacts, only transinteractions of NCAM, but not spectrin protein levels, were affected in NCAM+/+ neurons. Accumulation of spectrin at the heterogenotypic contacts was reduced, as indicated by reduced R spectrin. Only 32% of the heterogenotypic contacts formed by NCAM+/+ axons contacting NCAM−/− dendrites and 25.4% of the heterogenotypic contacts formed by NCAM−/− axons contacting NCAM+/+ dendrites showed R spectrin > 1.5, indicating that NCAM homophilic interactions are required for recruitment of spectrin to axodendritic contacts.

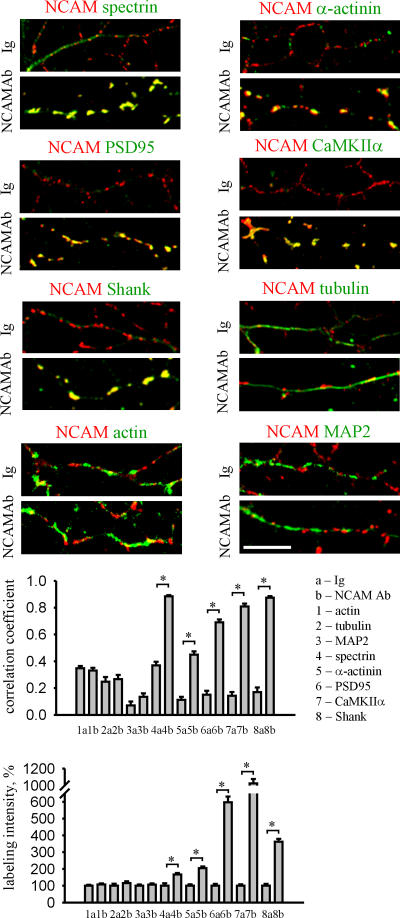

Clustering of NCAM induces formation of PSD-like structures in developing neurons

Because spectrin is a potent scaffolding protein (Pinder and Baines, 2000), and because NCAM promotes accumulation of spectrin at axodendritic contacts, we analyzed whether clustering of NCAM at the cell surface also redistributes other postsynaptic components into the NCAM-associated molecular scaffold (Fig. 2). Thus, we clustered NCAM with antibodies against its extracellular domain at the surface of hippocampal neurons maintained in culture for 4 d, i.e., before synapse formation. To analyze whether proteins of interest were indeed integrated in a scaffold with NCAM, we treated neurons with 1% Triton X-100, thereby removing detergent-soluble molecules, but sparing cytoskeletal scaffolds (Allison et al., 2000). Spectrin redistributed to NCAM clusters and formed detergent-insoluble complexes with NCAM, as indicated by an increase in the correlation between distributions of the two proteins when neurons treated with NCAM antibodies were compared with neurons treated with nonspecific immunoglobulins (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). Interestingly, other postsynaptic scaffolding proteins, such as PSD95 and α-actinin, which are located proximal to the plasma membrane, and Shank, which is located more on the cytoplasmic face of the PSD (Valtschanoff and Weinberg, 2001), also redistributed to detergent-insoluble clusters of NCAM, suggesting that NCAM not only clusters PSD components, but does so in an organized fashion, generating a structure that resembles the actual PSD. Strikingly, CaMKIIα, which is an enzyme enriched in PSDs, was also redistributed. Clustering of NCAM not only induced redistribution but also increased levels of detergent-insoluble spectrin, CaMKIIα, PSD95, Shank, and α-actinin, indicating that these proteins are recruited from the soluble pool and integrated in the NCAM-assembled scaffold (Fig. 2). In contrast, neither distribution nor levels of detergent-insoluble actin, tubulin, and MAP2 were affected by clustering of NCAM (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Clustering of NCAM induces formation of PSD-like structures in developing neurons. Neurons maintained in culture for 4 d were incubated live with nonspecific Igs or antibodies against the extracellular part of NCAM (NCAMAb) to cluster the protein at the cell surface, treated with 1% Triton X-100, and colabeled with antibodies against postsynaptic and cytoskeletal proteins, as indicated. Note the enhanced overlap of NCAM clusters with detergent-insoluble accumulations of spectrin, PSD95, Shank, CaMKIIα, and α-actinin in NCAM antibody–treated neurons. Histograms show coefficients of the correlation between distributions of NCAM and indicated proteins, and mean intensities of the labeling of the indicated proteins along neurites in Ig- and NCAMAb-treated neurons normalized to the mean labeling intensity of the protein in Ig-treated neurons. n ≥ 30 neurites were analyzed in each group. Mean values ± the SEM are shown. *, P < 0.05, t test.

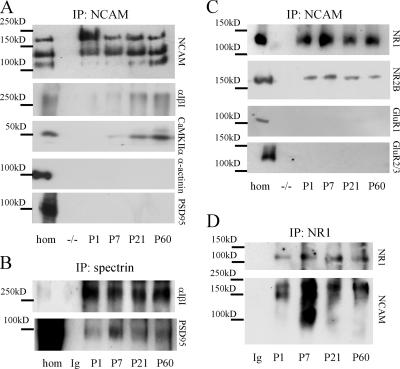

Postsynaptic components are linked to NCAM

Redistribution to NCAM clusters does not imply that proteins form a tight molecular complex with NCAM, but may reflect that proteins coredistribute to an NCAM-assembled scaffold in a more indirect manner. To analyze which postsynaptic proteins form a firmer complex with NCAM, we immunoprecipitated NCAM from detergent-solubilized brain homogenates and analyzed the immunoprecipitates with antibodies against postsynaptic components. Spectrin and CaMKIIα, but not PSD95 and α-actinin, coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM (Fig. 3). The ability of NCAM to redistribute PSD95 and α-actinin in cultured neurons, thus, suggests that although these proteins may not be in as tight a complex with NCAM as spectrin and CaMKIIα, PSD95 and α-actinin may relate to NCAM-associated proteins. PDZ domains have been shown to bind to spectrinlike motifs in α-actinin-2 (Xia et al., 1997), and indeed, when we immunoprecipitated spectrin from brain homogenates, PSD95 was coimmunoprecipitated (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

NCAM forms a complex with spectrin, NMDA receptors, and CaMKIIα. (A–D) NCAM (A and C), spectrin (B), or NR1 (D) were immunoprecipitated from brain homogenates of 1-d-old (P1), P7, P21, or P60 wild-type mice. Immunoprecipitations from NCAM−/− brains with NCAM antibodies (A and C) or from NCAM+/+ brains with nonspecific immunoglobulins (B and D) were performed for control. Precipitates were analyzed with antibodies as indicated. Spectrin (α1β1), CaMKIIα, NR1, and NR2B coimmunoprecipitate with NCAM (A and C) and NCAM coimmunoprecipitates with NR1 (D). GluR1, GluR2/3, α-actinin, and PSD95 do not coimmunoprecipitate with NCAM, but are detectable in the homogenate used for coimmunoprecipitation (hom). PSD95 coimmunoprecipitates with spectrin (B).

We also analyzed whether postsynaptic glutamate receptors associate with NCAM. The NMDA receptor subunits NR1 and NR2B, but not the AMPA receptor subunits GluR1 and GluR2/3, coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM, and NCAM coimmunoprecipitated with NR1 (Fig. 3). NR1 and NR2B also coclustered with NCAM at the surface of cultured hippocampal neurons (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200604145/DC1). Because PSD95 and α-actinin did not coimmunoprecipitate with NCAM, these results also indicate that NMDA receptors and CaMKIIα form a firmer complex with NCAM, most likely independent of PSD95 and α-actinin.

Association of NCAM with postsynaptic components was developmentally regulated; spectrin and NMDA receptors were already associated with NCAM in detergent-solubilized homogenates of brains from 1-d-old mice (the earliest age tested), whereas only low levels of CaMKIIα were found in NCAM immunoprecipitates in brains of mice of this age (Fig. 3). The levels of CaMKIIα in NCAM immunoprecipitates were significantly increased in adult brains reflecting the increased expression levels of CaMKIIα (unpublished data). In the adult brain, 27 ± 9.5% of total NR1 protein and 23 ± 13% of total CaMKIIα protein were associated with NCAM. These values may represent an underestimation of the actual levels because only ∼80% of NCAM, 60% of NR1, and 70% of CaMKIIα were solubilized under the detergent lysis conditions used (Fig. S2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200604145/DC1). In adult brains, the majority of NMDA receptors was associated with NCAM180, which is the predominant spectrin-binding isoform localized postsynaptically (Fig. 3). In brains of 1- and 7-d-old mice, NCAM140 and the predominantly glial NCAM120 isoform were also detected in the NR1 immunoprecipitates. The presence of NCAM120 in the immunoprecipitates may be caused by the presence of NMDA receptors in glia (Conti et al., 1996). The highest number of NCAM–NR1 complexes was found at postnatal day 7, the time of most active overall synaptogenesis.

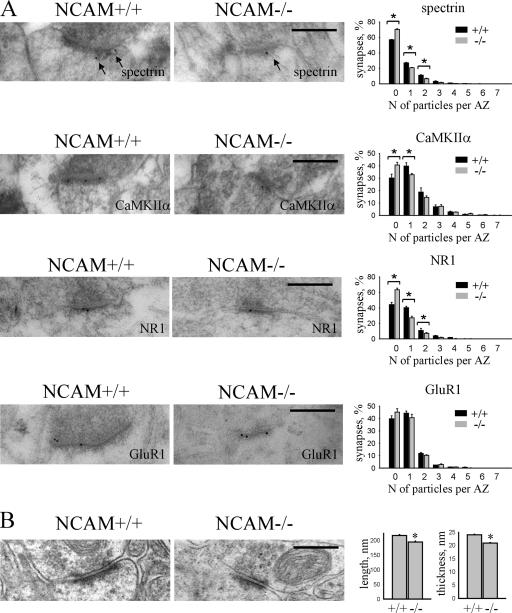

NCAM promotes accumulation of postsynaptic components in PSDs

To analyze the role of NCAM in the accumulation of PSD components in synapses in intact brains, we compared levels of spectrin, NR1, and CaMKIIα in synapses in the CA1 region of hippocampus of NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− mice by postembedding immunogold labeling (Fig. 4). In accordance with previous reports (Persohn et al., 1989; Malchiodi-Albedi et al., 1993), spectrin was accumulated in PSDs. Spectrin labeling was often associated with filamentous structures extending from the PSD (Fig. 4). In NCAM−/− mice, fewer synapses were labeled for spectrin, NR1, or CaMKIIα. Moreover, spectrin, NR1, and CaMKIIα-positive synapses in NCAM−/− mice contained fewer immunogold particles when compared with NCAM+/+ synapses. In contrast, synaptic accumulation of the GluR1 subunit of the AMPA receptor was not influenced in NCAM−/− brains.

Figure 4.

PSD size and accumulation of spectrin, NMDA receptors, and CaMKIIα are reduced in NCAM−/− synapses. (A) Examples of immunogold labeling of NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− synapses in the CA1 region of the hippocampus with antibodies against spectrin, NR1, CaMKIIα, and GluR1. Arrows show filamentous material recognized by spectrin antibodies. Histograms show the percentage of synapses containing an indicated number of gold particles per active zone in NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− brains. n = 6 animals were analyzed per genotype. Mean values ± the SEM are shown. *, P < 0.05, paired t test. Note that the percentage and labeling intensity of synapses labeled for spectrin, NR1, and CaMKIIα, but not GluR1, are reduced in NCAM−/− mice. (B) Examples of synapses in the CA1 region of the hippocampus of NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− mice. Histograms show the length and thickness (mean ± the SEM) of PSDs. n = 200 synapses were analyzed per genotype. Length and thickness of PSDs are reduced in NCAM−/− synapses. *, P < 0.05, t test. Bars, 0.3 μm.

To study whether reduced accumulation of spectrin, NMDA receptors, and CaMKIIα in NCAM−/− synapses may correlate with structural abnormalities of PSDs, we analyzed some ultrastructural features of PSDs in the CA1 region of the hippocampus; the length and thickness of PSDs in NCAM−/− brains were reduced by ∼10 and 15%, respectively, when compared with NCAM+/+ mice (215.9 ± 3.1 nm and 24.0 ± 0.2 nm in NCAM+/+ vs. 193.9 ± 3.3 nm and 20.9 ± 0.2 nm in NCAM−/− mice; Fig. 4). Assuming that the PSD is a disk, these apparently small changes would, however, yield a 20 and 30% decrease in the surface and volume of PSDs, respectively.

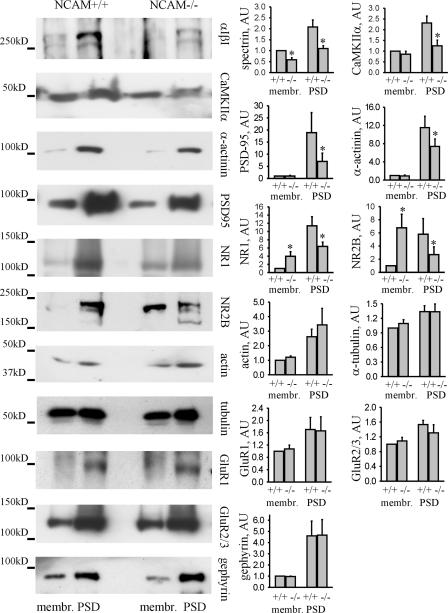

To extend this analysis, we isolated membrane fractions from adult NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− mouse brains, which were then used to isolate PSDs (Lai et al., 1998), and compared levels of NCAM-associated postsynaptic proteins in these fractions (Fig. 5). Spectrin levels were reduced in membrane and PSD fractions from NCAM−/− brains, confirming the role of NCAM in recruiting spectrin to membrane subdomains. Levels of NR1 and NR2B were reduced in the PSD fraction and increased in the membrane fraction isolated from NCAM−/− brains, suggesting that these transmembrane proteins are not efficiently recruited to PSDs in the absence of NCAM as a synapse-targeting cue and redistributed to other membrane domains. Interestingly, NR1 levels were increased in NCAM−/− brain homogenates (Fig. S3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200604145/DC1), indicating that the overall expression of NMDA receptors in NCAM−/− brains is increased, possibly as a compensatory reaction to its inefficient synaptic targeting. Levels of CaMKIIα, PSD95, and α-actinin were also reduced in PSDs from NCAM−/− mice, further confirming the relationship between NCAM and these postsynaptic components. In contrast, levels of GluR1, GluR2/3, actin, tubulin, and the postsynaptic scaffolding protein of inhibitory synapses, gephyrin, were similar in PSDs and membrane fractions from NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− mice (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Levels of postsynaptic components associating with NCAM and spectrin are reduced in the PSD fraction from NCAM−/− brains. Membrane and PSD fractions from NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− brains were probed by Western blotting with antibodies against postsynaptic proteins, as indicated. Histograms show quantitation of the protein levels in the fractions. *, P < 0.05, paired t test. Note a significant reduction of spectrin, CaMKIIα, PSD95, α-actinin, NR1, and NR2B in PSDs and increased levels of NR1 and NR2B in membrane fractions from NCAM−/− brains. AU, arbitrary units.

Spectrin is a linker between NCAM, the NMDA receptor, and CaMKIIα

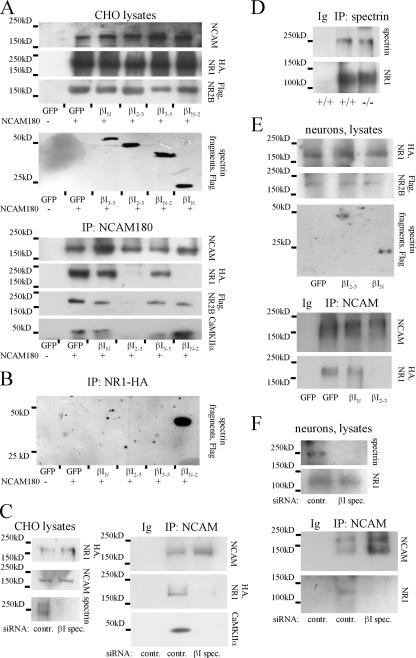

As a scaffolding protein, spectrin has been shown to cross- link NCAM with transmembrane and cytosolic proteins (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003; Bodrikov et al., 2005). To characterize the role of spectrin in complex formation between NCAM and the NMDA receptor and CaMKIIα, we analyzed the formation of these complexes in the presence of a βI spectrin fragment consisting of the 2 and 3 spectrin repeats (βI2-3). This fragment contains the NCAM-binding site and disrupts the association of NCAM with endogenous spectrin by a dominant-negative mechanism (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). CHO cells or cultured cortical neurons were therefore cotransfected with βI2-3, NR1 carrying a HA tag, and NR2B carrying a Flag tag. CHO cells, which do not express NCAM, were additionally cotransfected with NCAM180. In cotransfected CHO cells, NMDA receptors were detected at the cell surface, where they colocalized with NCAM (Fig. S4, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200604145/DC1). For control, we used GFP or fragments containing the N-terminal domain of βI spectrin (βIN), the N-terminal and 1–2 spectrin repeats (βIN-2), or the 3–5 spectrin repeats (βI3-5) for transfection. Whereas all transfected proteins were expressed in approximately equal amounts, as measured by Western blot analysis in cell lysates, coimmunoprecipitation of NMDA receptors and CaMKIIα with NCAM was reduced by βI2-3 but was not affected by βIN or βI3-5 in CHO cells or in cortical neurons (Fig. 6). Similar results were obtained when CHO cells were cotransfected with NCAM140 (unpublished data). However, NCAM180 was more potent in precipitating the NMDA receptor subunits and CaMKIIα when compared with NCAM140, correlating with their ability to bind spectrin (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003).

Figure 6.

Spectrin is a linker protein between NCAM and NMDA receptors and CaMKIIα. (A and E) CHO cells (A) or cortical neurons (E) were cotransfected with NR1–HA/NR2B–Flag and βI spectrin fragments as indicated. CHO cells were additionally cotransfected with NCAM180. In control cells, NCAM180 and/or spectrin fragment cDNAs were replaced by GFP cDNA. NCAM180, NMDA receptor subunits, and spectrin fragments were expressed at similar levels in the cell lysates of all transfection combinations. NCAM was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates, and immunoprecipitates were analyzed with antibodies against HA and Flag tags and CaMKIIα. NMDA receptors and endogenous CaMKIIα coimmunoprecipitate with NCAM in cells where spectrin fragments were replaced by GFP. Coimmunoprecipitation is blocked by transfection with βI2-3 but is not affected by transfection with βIN or βI3-5. Coimmunoprecipitation of NR1 with NCAM180 from CHO cells is also blocked by βIN-2. (B) CHO cells were cotransfected with NR1-HA and GFP alone or GFP together with βI spectrin fragments. NR1-HA was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and immunoprecipitates were analyzed with antibodies against Flag tag. Only βIN-2 immunoprecipitates with NR1. (D) Spectrin was immunoprecipitated from NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− brains. NR1 coimmunoprecipitated with spectrin in both genotypes. (C and F) CHO cells (C) or hippocampal neurons (F) were transfected with control or βI spectrin siRNA. CHO cells were additionally cotransfected with NR1–HA/NR2B–Flag and NCAM180. Transfection with βI spectrin siRNA reduced expression of spectrin, but did not affect expression of NR1 and NCAM in the cell lysates. NCAM was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates and immunoprecipitates were analyzed with antibodies against NR1. Note that coimmunoprecipitation of NR1 and CaMKIIα with NCAM is blocked by βI spectrin siRNA. In C, D, and F, immunoprecipitation with nonspecific Ig was performed as control.

Interestingly, the βIN-2 spectrin fragment also blocked the association between NCAM and NR1, but did not affect binding of NCAM to spectrin (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003), CaMKIIα, or NR2B, suggesting that this fragment contains the binding site for NR1. To verify this, NR1 was immunoprecipitated from CHO cells cotransfected with different βI spectrin fragments and assayed for its ability to bind βI spectrin fragments. Only βIN-2 coimmunoprecipitated with NR1, indicating that this spectrin fragment contains the binding site for NR1 (Fig. 6). Because in these experiments the NR1 splice variant that was transfected into CHO cells without its heterodimeric partner NR2B was largely retained in the ER (McIlhinney et al., 1998), our data suggest that the interaction between NMDA receptors and spectrin already occurs in this intracellular compartment.

Coimmunoprecipitation of NR1 with spectrin was not affected in NCAM−/− brains, indicating that NCAM is not required for this interaction (Fig. 6). To further confirm that spectrin is necessary for the formation of the NCAM–NMDA receptor complex, CHO cells or cultured hippocampal neurons were cotransfected with βI spectrin siRNA. This reduction of spectrin expression abolished the interaction of NMDA receptors and CaMKIIα with NCAM180 in cotransfected CHO cells, and disrupted the complex of endogenous NCAM and NMDA receptors in hippocampal neurons (Fig. 6).

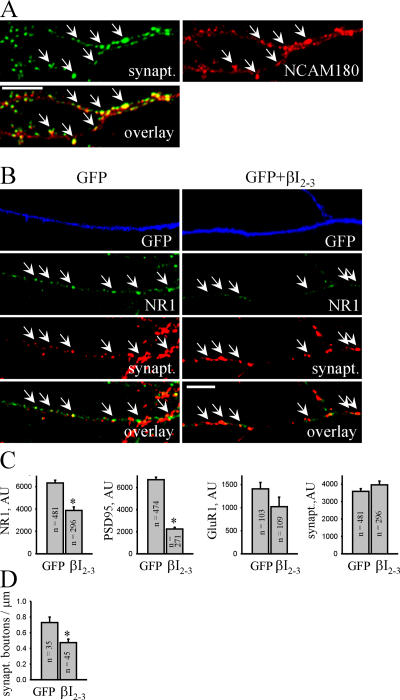

Disruption of the NCAM–spectrin complex reduces formation of postsynaptic complexes in cultured neurons

In hippocampal neurons maintained in culture for 14 d, NCAM180 accumulated in PSDs (Fig. 7), as previously observed in brain (Persohn et al., 1989; Schuster et al., 1998), indicating that cultured neurons are relevant for further analysis of the role of spectrin in NCAM-mediated recruitment of postsynaptic proteins to PSDs. To this aim, we transfected hippocampal neurons with the βI2-3 spectrin fragment and analyzed accumulation of postsynaptic components in synapses (Fig. 7). To distinguish transfected neurons, they were cotransfected with GFP. In neurons transfected with βI2-3, postsynaptic accumulation of NR1 and PSD95 was reduced when compared with GFP-only–transfected neurons, whereas presynaptic synaptophysin accumulations were not altered. We also found a small reduction in synaptic targeting of GluR1 in βI2-3-transfected neurons. Similar results were obtained when MAP2-GFP was used to identify dendrites of transfected neurons (unpublished data). Transfection with the βIN spectrin fragment did not affect synaptic targeting of the NMDA receptors (unpublished data).

Figure 7.

Transfection with the dominant-negative βI2-3 spectrin fragment interferes with PSD formation in cultured hippocampal neurons. (A) NCAM+/+ neurons were colabeled with antibodies against synaptophysin and NCAM180. Note the accumulations of NCAM180 apposed to synaptophysin-positive synaptic boutons (arrows). (B) NCAM+/+ neurons were transfected with GFP only or cotransfected with GFP and βI2-3 and maintained in culture for 14 d before immunostaining with antibodies against NR1 and synaptophysin. Note the reduced size of NR1 clusters (arrows) in βI2-3-transfected neurons. Bars, 10 μm. (C) Histograms show quantitation of the postsynaptic accumulation of NR1, PSD95, and GluR1 and presynaptic accumulation of the apposed synaptophysin in GFP- and βI2-3-transfected neurons. AU, arbitrary units. (D) The histogram shows the number of synaptophysin-positive boutons along neurites of GFP-transfected or GFP- and βI2-3–cotransfected neurons. The number of synapses formed on βI2-3-transfected neurons is decreased. For C and D, mean values ± SEM are shown. The number (n) of synapses (C) or neurites (D) analyzed is shown for each bar. *, P < 0.05, t test.

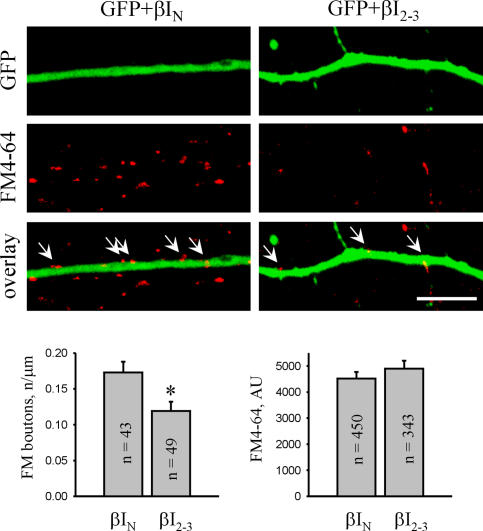

Interestingly, the number of synaptophysin puncta along dendrites of βI2-3-transfected neurons was reduced when compared with GFP-only–transfected neurons (Fig. 7). To investigate whether this phenomenon reflects a reduction in the number of functional synapses, presynaptic boutons capable of active exo- and endocytosis were loaded with the lipophilic dye FM4-64 applied to neurons in the presence of 47 mM K+ (Fig. 8). The number of FM4-64–loaded boutons along βI2-3-transfected dendrites was reduced by ∼40% when compared with βIN-transfected cells, indicating that NCAM-mediated postsynaptic accumulation of spectrin and spectrin-associated proteins is required for synapse formation. In contrast, uptake of FM4-64 into individual synaptic boutons along βI2-3- transfected dendrites was not affected, indicating that disruption of the postsynaptic NCAM–spectrin complex does not affect the presynaptic machinery.

Figure 8.

Transfection with the dominant-negative βI2-3 spectrin fragment interferes with synapse formation on transfected neurons. NCAM+/+ neurons were cotransfected with GFP and βI2-3 or βIN and maintained in culture for 14 d before synaptic boutons were loaded with FM4-64. Bar, 10 μm. Histograms show the number of FM4-64–loaded boutons and quantitation of FM4-64 uptake in synaptic boutons along neurites of βIN- or βI2-3–cotransfected neurons. Mean values ± the SEM are shown. The number (n) of analyzed synapses or neurites is shown for each bar. *, P < 0.05, t test. AU, arbitrary units.

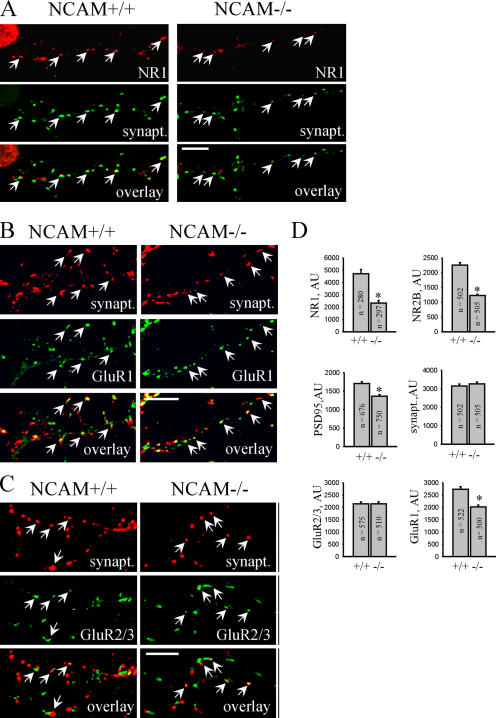

Similar to βI2-3-transfected neurons, postsynaptic accumulations of NR1, NR2B, and PSD95 were reduced in NCAM−/− neurons, whereas accumulation of synaptophysin in presynaptic boutons was not changed (Figs. 9 and 10). In contrast, although postsynaptic accumulation of GluR1 was slightly reduced in NCAM−/− neurons, synaptic targeting of GluR2/3 subunits was not changed (Fig. 9). It is noteworthy, in this context, that GluR1 interacts with protein 4.1, which is a prominent binding partner of spectrin that anchors AMPA receptors to the cytoskeleton (Shen et al., 2000). Reduced association of GluR1 with the synaptic scaffold because of spectrin deficiency may cause reduced synaptic targeting of GluR1 in cultured NCAM−/− and βI2-3-transfected neurons. However, PSDs from NCAM−/− brains contain normal levels of GluR1, suggesting more potent synapse-targeting cues than NCAM. Among those could be secreted molecules, such as neuronal activity–regulated pentraxin (Narp), which is involved in the clustering of AMPA receptors (O'Brien et al., 1999). Alternatively, NCAM-independent accumulation of PSD95 may suffice for proper synaptic targeting of AMPA receptors.

Figure 9.

PSD formation is impaired in cultured NCAM−/− hippocampal neurons. (A–C) NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− neurons maintained in culture for 14 d were labeled with antibodies against synaptophysin and NR1 (A), GluR1 (B), or GluR2/3 (C). Arrows show examples of postsynaptic NR1, GluR1, and GluR2/3 clusters. Note the reduced size of NR1 and GluR1 clusters in NCAM−/− neurons. Bars, 10 μm. (D) Histograms show quantitation of the postsynaptic accumulation of NR1, NR2B, PSD95, GluR1, and GluR2/3, and the presynaptic accumulation of the apposed synaptophysin immunolabeling in NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− neurons. Mean values ± the SEM are shown. The number (n) of analyzed synapses is shown for each bar. *, P < 0.05, t test. AU, arbitrary units.

Figure 10.

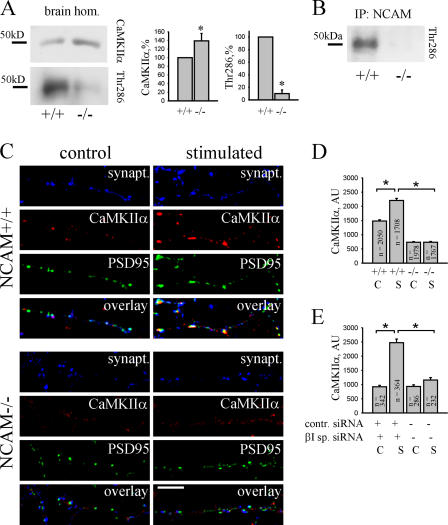

Activation and synaptic recruitment of CaMKIIα is impaired in NCAM−/− neurons. (A) NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− brain homogenates were probed by Western blotting with antibodies against total CaMKIIα and CaMKIIα phosphorylated at Thr286. Note that total CaMKIIα is increased, whereas phospho-Thr286 CaMKIIα is reduced in NCAM−/− brains. Histograms show quantitation of the blots. *, P < 0.05, paired t test. (B) NCAM immunoprecipitates from brain homogenates of P60 wild-type mice were analyzed with antibodies against phospho-Thr286 CaMKIIα. Immunoprecipitation from NCAM−/− brain homogenates was performed for control. Phospho-Thr286 CaMKIIα coimmunoprecipitates with NCAM. (C) NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− neurons were stimulated with 50 μM glutamate plus 5 μM glycine for 20 s. Control untreated and stimulated neurons were then labeled with antibodies against synaptophysin, CaMKIIα, and PSD95. Note the reduced size of PSD95 clusters in NCAM−/− neurons. Note the increased postsynaptic levels of CaMKIIα in stimulated NCAM+/+, but not in NCAM−/−, neurons. (D and E) The histograms show mean labeling intensity of CaMKIIα in postsynaptic PSD95 clusters in control (C) and stimulated (S; as indicated in C) NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− neurons (D) and control siRNA and βI spectrin siRNA-transfected NCAM+/+ neurons (E). Mean values ± the SEM are shown. The number (n) of analyzed synapses is shown for each bar. *, P < 0.05, t test. AU, arbitrary units.

Activity-dependent translocation of CaMKIIα to PSDs is impaired in NCAM−/− neurons

The current model for enhancement of synaptic strength suggests that Ca2+ entering through NMDA receptors activates CaMKIIα, which in turn leads to an increase in the number and conductivity of AMPA receptors within PSDs (Derkach et al., 1999; Shi et al., 1999). Interestingly, this type of synaptic plasticity is abnormal in NCAM−/− mice showing impaired NMDA receptor–dependent LTP (Muller et al., 1996; Bukalo et al., 2004). Thus, we hypothesized that abnormal PSD organization in NCAM−/− mice may affect signaling events in PSDs required for LTP. Indeed, whereas CaMKIIα protein levels were increased, levels of constitutively active CaMKIIα autophosphorylated at threonine 286 were reduced in NCAM−/− brains (Fig. 10), correlating with reduced levels of NMDA receptors in PSDs (Figs. 4, 5, and 9). NMDA receptor–dependent activation of CaMKIIα is accompanied by its translocation to postsynaptic sites (Shen and Meyer, 1999) and is regulated by the number of docking sites for CaMKIIα in PSDs (Leonard et al., 2002). Threonine 286–autophosphorylated CaMKIIα coimmunoprecipitated with NCAM (Fig. 10), indicating that the NCAM-associated scaffold may be a synapse-targeting cue for activated CaMKIIα. In accordance with this notion, clustering of NCAM induces redistribution and recruitment of CaMKIIα to the NCAM-assembled scaffold (Fig. 2). Accordingly, levels of CaMKIIα were reduced in NCAM−/− PSDs (Figs. 4 and 5). To extend this analysis and verify whether activity-dependent translocation of CaMKIIα to synapses is affected in NCAM−/− neurons, we compared levels of CaMKIIα in synapses of cultured NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− neurons at resting conditions and after incubation with 50 μM glutamate plus 5 μM glycine (Fig. 10), a protocol that induces NMDA receptor–dependent translocation of CaMKIIα to synapses (Shen and Meyer, 1999). Control and activated neurons were colabeled with antibodies against CaMKIIα and PSD95 to label PSDs and to determine CaMKIIα immunofluorescence intensity within PSD95 clusters. In nonstimulated neurons, CaMKIIα levels were reduced in PSDs of NCAM−/− neurons when compared with NCAM+/+ neurons, in accordance with data for brain tissue (Figs. 4 and 5). Stimulation with glutamate enhanced levels of CaMKIIα in PSDs of NCAM+/+ neurons, in accordance with previous reports (Shen and Meyer, 1999). However, redistribution of CaMKIIα to PSDs of NCAM−/− neurons was strongly inhibited. Because in these experiments glutamate was applied to neurons in the culture medium, not only synaptic but also extrasynaptic NMDA receptors were activated. Because the levels of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors were increased in NCAM−/− versus NCAM+/+ neurons (Fig. 5), reduced redistribution of CaMKIIα to NCAM−/− PSDs was not likely caused by reduced activation of NMDA receptors by glutamate in NCAM−/− neurons. It is noteworthy, in this respect, that overall CaMKIIα protein expression was increased in NCAM−/− when compared with NCAM+/+ brains (Fig. 10). Redistribution of CaMKIIα to synapses was also inhibited in cultured NCAM+/+ neurons transfected with βI spectrin siRNA (Fig. 10). The combined observations indicate that the spectrin-based NCAM-associated postsynaptic signaling complex is required for efficient activity-dependent translocation of CaMKIIα to PSDs.

Discussion

It is now well-documented that NCAM plays an important role in memory formation and synaptic plasticity (Bukalo et al., 2004), but the mechanisms by which NCAM exerts its functions have remained poorly understood. Using a variety of methods, we show that NCAM is an important PSD-targeting cue for spectrin, and that NCAM initiates and maintains a targeting platform for functionally crucial components of the synaptic machinery on dendrites. The fact that NCAM already promotes spectrin accumulation at immature axodendritic contacts before synapse formation suggests that NCAM clusters spectrin at contact sites, thereby promoting recruitment of the crucial binding partners, predominantly NMDA receptors and CaMKIIα, and thus transforming the initial contact into a functional synapse. Clustering of NCAM with antibodies in cultured neurons induces the formation of detergent- insoluble complexes enriched not only in NCAM, spectrin, and CaMKIIα but also in PSD95, Shank, and α-actinin, which are all constituents of PSDs. We call these complexes spectrin-based postsynaptic specializations, thus, highlighting spectrin as a cross-linking platform between NCAM and other components of the PSD. Whether Ca2+ influx and intracellular signaling cascades activated by NCAM clustering (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003; Bodrikov et al., 2005) induce posttranslational modifications of postsynaptic proteins, thereby priming them for recruitment to PSDs, is an important topic for further investigation.

NCAM is required not only for spectrin accumulation at immature axodendritic contacts but also for the maintenance of spectrin and the accumulation of the associated proteins in PSDs in differentiated neurons. In culture, disruption of the NCAM–spectrin complex in differentiated NCAM-deficient neurons or by a functionally blocking spectrin fragment in differentiated wild-type neurons reduces the accumulation of associated proteins in PSDs. This was also seen by immunohistology at the electron microscopic level in brain tissue and in biochemically isolated PSDs from adult brain tissue.

The NCAM-associated spectrin scaffold is interconnected with other scaffolding proteins in PSDs, such as PSD95 and α-actinin. However, PSD95 and α-actinin are not tightly associated with NCAM because we could not detect them in NCAM immunoprecipitates. Nevertheless, disruption of the NCAM–spectrin complex also reduces synaptic accumulation of PSD95 and α-actinin. PSD95 and α-actinin are also recruited to detergent-insoluble complexes of NCAM after the NCAM antibody induced clustering at the cell surface, probably by interaction with NCAM-associated proteins. An additional linkage between NCAM and postsynaptic scaffolds is provided by the interaction between spectrin and actin. At the cell surface, NCAM forms complexes with other cell adhesion molecules, such as N-cadherin (Cavallaro et al., 2001), L1 (Kadmon et al., 1990), and the cellular prion protein (Santuccione et al., 2005). The interconnectivity of postsynaptic scaffolds implies that disruption of a single scaffolding system in PSDs would not necessarily lead to a complete dissociation of the PSD complex because other scaffolding proteins may compensate, at least partially, for the missing protein. Accordingly, synaptic targeting of NMDA receptors and synapse density of the receptor subunits are normal in PSD95-deficient mice or when PSD95 family proteins are dispersed by an interfering peptide (Migaud et al., 1998; Passafaro et al., 1999). Similarly, disruption of N-cadherin adhesion by a dominant-negative construct only delays, but does not abolish, synapse formation, resulting in smaller synapses (Bozdagi et al., 2004). We also show that disruption of the NCAM–spectrin complex does not abolish synapse formation, but produces smaller PSDs containing reduced levels of spectrin, NMDA receptors, and CaMKIIα.

Although synapse formation per se is not disrupted in NCAM−/− mice, the ability of synapses to produce NMDA receptor–dependent LTP is severely impaired in this mutant (Muller et al., 1996; Bukalo et al., 2004). Our observations yield at least a partial explanation to this phenomenon; one of the major enzymes required to produce long-lasting changes in the synaptic strength is CaMKIIα (Fink and Meyer, 2002; Lisman et al., 2002). Upon NMDA receptor activation and Ca2+ influx, CaMKIIα redistributes to PSDs, where it phosphorylates several substrates, including AMPA receptors. We show that this pathway is impaired in NCAM−/− neurons, which accumulate reduced levels of CaMKIIα in PSDs already under nonstimulated conditions and are not able to increase levels of CaMKIIα in response to synapse activation. A possible explanation for this could be twofold; lower numbers of NMDA receptors in NCAM−/− PSDs result in reduced activation of CaMKIIα, whereas reduced levels of spectrin in NCAM−/− PSDs result in impaired recruitment of CaMKIIα to synapses.

NCAM deficiency affects not only the structural organization of PSDs, resulting in reduction in their size, but disruption of the NCAM–spectrin complex also reduces the efficacy of excitatory synapse formation, thus, providing support for NCAM as a signal that recruits postsynaptic components to nascent synapses.

Genetic variations in the NCAM gene have been reported a risk factor in bipolar affective disorders in humans (Arai et al., 2004). Patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder accumulate secreted extracellular cleavage products of NCAM in hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (Vawter et al., 1999, 2001). These cleavage products may interfere with homophilic or heterophilic interactions of NCAM. Strikingly, transgenic mice ectopically expressing secreted NCAM display disturbed synaptic connectivity and abnormal behavior that may be relevant to schizophrenia (Pillai-Nair et al., 2005). Because neurological dysfunctions are, in many instances, likely to relate to synaptic abnormalities, our study lends support to the notion that NCAM is an important player in the assembly and function of a unique invention: the synapse.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and toxins

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies and rat monoclonal antibody H28 against mouse NCAM recognizing extracellular epitopes of the protein were as previously described (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). NCAM180 was detected with monoclonal antibody D3 (Schlosshauer, 1989). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against NR2B and goat polyclonal antibodies against synaptophysin were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; rabbit polyclonal antibodies against erythrocyte spectrin, CaMKIIα, and HA tag, mouse monoclonal antibodies against Flag tag, α-actinin, and MAP2, and nonspecific rabbit and rat immunoglobulins were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; mouse monoclonal antibodies against NR1 (clone 54.1), NR2B, and gephyrin were obtained from BD Biosciences; mouse monoclonal antibodies against PSD95 were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology; mouse monoclonal antibodies against CaMKII were obtained from Stressgen Biotechnologies; rabbit polyclonal antibodies against phospho-CaMKII (Thr286) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology; mouse monoclonal antibodies against actin (clone JLA20) and β-tubulin (clone E7) were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; and mouse monoclonal antibodies against HA tag (clone 12CA5) were purchased from Roche. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against GluR1, GluR2/3, NR1, and rabbit polyclonal antibodies reactive with mouse Shank were gifts from R.J. Wenthold (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, Bethesda, MA) and H.-J. Kreienkamp (Universitätskrankenhaus Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), respectively. Secondary antibodies against rabbit, goat, rat, and mouse Ig coupled to HRP, Cy2, Cy3, or Cy5 were obtained from Dianova. DL-AP5 was purchased from Tocris.

DNA constructs and siRNA

The vector containing the HA-NR1-1-GFP subunit of the NMDA receptor with the HA tag in the extracellular part of the protein and GFP tag in the intracellular part of the protein was a gift from G.A. Dekaban (The John P. Robarts Research Institute, London, Ontario, Canada). NR2B-Flag with the Flag tag in the extracellular part of the protein was a gift from L. Hawkins (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, Bethesda, Maryland). Constructs encoding βI spectrin fragments and NCAM isoforms have been described previously (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). The eGFP plasmid was purchased from CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc. Spectrin βI siRNA was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Control (nonsilencing) siRNA was purchased from QIAGEN.

Animals

NCAM−/− mice were provided by H. Cremer (Cremer et al., 1994) and were inbred for at least nine generations onto the C57BL/6J background. Animals for biochemical experiments (ages as indicated in the text) and electron microscopy (3-mo-old) were NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− littermates obtained from heterozygous breeding. To prepare cultures of hippocampal neurons, 1- to 3-day-old C57BL/6J and NCAM−/− mice from homozygous breeding pairs were used.

Cultures of hippocampal and cortical neurons and CHO cells

Cultures of hippocampal and cortical neurons were maintained on glass coverslips (for immunocytochemistry) or in 6-well plates (for biochemistry) in hormonally supplemented culture medium containing 5% horse serum (Sigma-Aldrich; Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). Coverslips and plates were coated overnight with 100 μg/ml poly-l-lysine in conjunction with 20 μg/ml laminin. For analysis of synaptic accumulation of NMDA receptors, neurons were chronically treated with 100 μM DL-AP5 to increase synaptic targeting of NMDA receptors (Fong et al., 2002). CHO cells were maintained in Glasgow's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% of fetal calf serum. Neurons were transfected 4 d after plating with DNA constructs or 12 d after plating with siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and analyzed 14 d after plating. CHO cells were transfected using Lipofectamine with Plus reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. In experiments analyzing activity-dependent synaptic translocation of CaMKIIα, neurons were treated for 20 s with 50 μM glutamate plus 5 μM glycine (Shen and Meyer, 1999).

Indirect immunofluorescence labeling

Immunolabeling was performed essentially as previously described (Sytnyk et al., 2002). For labeling of GluR1 and GluR2/3, cultures were fixed in 4% formaldehyde/4% sucrose in PBS, pH 7.3, for 10 min at 37°C, washed, and permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min. This type of mild fixation was also used for the labeling of GFP-transfected neurons to preserve GFP fluorescence. For labeling of NR1, NR2B, PSD95, CaMKIIα, and NCAM180 in nontransfected neurons, fixation with methanol (−20°C for 7 min) was used. Neurons were blocked in 3% BSA in PBS. The antibodies were applied in 3% BSA in PBS for 2 h at 37°C and detected with corresponding secondary antibodies after incubation for 45 min at room temperature. To label NCAM, Flag, or HA tag at the cell surface of live neurons, antibodies against NCAM, HA, or Flag tag were applied in culture medium to live cultures for 10 min and detected with fluorochrome-coupled secondary antibodies applied for 5 min, all in a CO2 incubator (Sytnyk et al., 2002). Detergent extraction was performed as previously described (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). Clustering of NCAM was induced by incubating live 4-d-old neurons for 15 min (5% CO2 at 37°C) with NCAM antibodies, and was visualized with secondary antibodies applied for 5 min (Leshchyns'ka et al., 2003). Detergent-extracted neurons were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS and labeled with antibodies.

Loading of synapses with FM4-64

Neurons were briefly washed in modified Tyrode solution containing 150 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, 10 mM Hepes, and 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4, (∼310 mosM) and incubated for 90 s in 47 mM K+ solution (modified Tyrode solution containing equimolar substitution of KCl for NaCl) containing 15 μM FM4-64 (Invitrogen) to induce synaptic vesicle exo- and endocytosis (Virmani et al., 2003). Neurons were then extensively washed with modified Tyrode solution. All staining protocols were performed with 10 μM CNQX and 50 μM AP-5 to prevent recurrent activity. Images were acquired from live neurons maintained in modified Tyrode solution at room temperature using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM510; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.).

Image acquisition and manipulation

Coverslips were embedded in Aqua-Poly/Mount (Polysciences, Inc.). Images were acquired at room temperature using a LSM510, LSM510 software (version 3), and an oil Plan-Neofluar 40× objective, NA 1.3 (all Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) at 3× digital zoom. Contrast and brightness of the images were further adjusted in Corel Photo-Paint 9 (Corel Corporation).

Immunofluorescence quantification

Immunofluorescence quantification was performed essentially as previously described (Fong et al., 2002). In brief, to define synaptic NR1, NR2B, GluR1, GluR2/3, or PSD95 clusters, the thresholds for each individual experiment and corresponding channels were chosen manually and corresponded approximately to two times the average intensity of fluorescence in the dendritic shafts. The same threshold was used for all neurons in one experiment. Binary images of clusters of NR1, NR2B, GluR1, GluR2/3, or PSD95 were compared with binary images of synaptophysin clusters. Any postsynaptic cluster that had at least one pixel of overlap with a presynaptic cluster was defined as synaptic. Cluster size and mean intensity of the labeling within a cluster were measured using Scion Image for Windows (Scion Corporation). Synaptic accumulation of the protein was then defined as a product of cluster size and mean labeling intensity of the protein and expressed in arbitrary units. CaMKIIα intensity was measured in PSD95 clusters. Values indicate the mean ± the SEM. Group comparisons were made by t test. Each experiment was reproduced at least two times. Colocalization profiles were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Correlation coefficients were calculated using Excel software (Microsoft).

Gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting

Proteins were separated by 6–16% SDS-PAGE and electroblotted to Nitrocellulose Transfer Membrane (PROTRAN; Schleicher & Schuell) for 3 h at 250 mA. Immunoblots were incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies, followed by incubation with HRP-labeled secondary antibodies, and visualized using Super Signal West Pico or West Dura reagents (Pierce Chemical Co.) on BIOMAX film (Sigma-Aldrich). Molecular mass markers were prestained protein standards obtained from Bio-Rad laboratories. For quantitative comparisons of chemiluminescence between the lanes, the same amounts of total protein or equal amounts of immunoprecipitates were loaded in each lane. All preparations were performed three times, and at least two Western blots were performed with an individual sample (n ≥ 6). In experiments, when NCAM+/+ and NCAM−/− total membrane and PSD fractions were compared, NCAM+/+ total membrane values were set to 1 and other intensities were normalized to these values. Values of all experiments were used to calculate mean values and SEMs. The chemiluminescence quantification was performed using TINA 2.09 software (University of Manchester, Manchester, England) or Scion Image for Windows (Microsoft). Group comparisons were made by paired t test.

Coimmunoprecipitation

Brain homogenates were prepared in 5 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, containing 1 mM of CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM NaHCO3. Samples containing 1 mg of total protein were lysed for 40 min at +4°C with lysis buffer, pH 7.5, containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1 mM Na2P2O7, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM NaVO4, 0.1 mM PMSF, and complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and centrifuged for 15 min at 20,000 g at 4°C. Supernatants were cleared with protein A/G–agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) for 3 h at 4°C and incubated with corresponding antibodies or control Ig overnight at 4°C, followed by precipitation with protein A/G–agarose beads for 1 h at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and two times with PBS, and then analyzed by immunoblotting.

Subcellular fractionation

Membrane fractions and PSDs were isolated as previously described (Lai et al., 1998). Total protein concentration was measured using the BC kit (Interchim).

Electron microscopy and postembedding immunocytochemistry

To measure PSD size, tissue was processed as previously described (Saghatelyan et al., 2004). Postembedding immunocytochemistry was also performed essentially as previously described (Wang et al., 1998). In brief, mice were deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused with 2% ice-cold dextran (70,000 kD) in PBS, and then with 4% formaldehyde/0.3% glutaraldehyde in PBS at room temperature. Brains were removed, incubated in the fixative overnight at 4°C, washed, and cut in 100-μm-thick coronal sections with a VT1000S vibratome (Leica) all in 4% sucrose in PBS. Sections were cryoprotected using a series of 10, 20, and 30% sucrose in PBS, plunge-frozen in 2-methyl-butane precooled with liquid nitrogen, and subjected to freeze-substitution and low-temperature embedding in Monostep Lowicryl HM20 resin. Frozen tissue was immersed in methanol at −90°C in an AFS instrument (Leica), infiltrated in Lowicryl HM 20 resin at −45°C, and polymerized with UV light (−45–0°C). 90-nm sections were cut on an Ultracut S ultramicrotome (Leica) and collected on parlodion-coated nickel grids. Grids were incubated in 0.1% sodium borohydride and 50 mM glycine in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.4, containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (TBST) for 10 min, and incubated for 10 min in 10% normal donkey serum (NDS) in TBST, followed by primary antibodies in 1% NDS in TBST for 2 h. Primary antibody concentrations were selected to produce no background immunogold labeling. Sections from both genotypes were labeled in parallel. Grids were washed in TBST, blocked in 10% NDS/TBST, and incubated with 12-nm immunogold particles (GE Healthcare; 1:20) in NDS/TBST plus 0.5% polyethylene glycol (20,000 kD) for 1 h. Sections were counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate.

Immunogold particles were counted in the regions designated as active zones encompassing the synaptic cleft and PSD of the synapse in the CA1 stratum radiatum in a transmission electron microscope (CEM 902A; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) at 20,000× magnification by analyzing randomly selected grid squares. The size of PSDs was measured in asymmetric synapses on randomly sampled digital images taken with a camera (MegaView II; Soft Imaging System) at 50,000× magnification. The length and thickness of PSD profiles were measured as longest and shortest dimensions of electron dense material in the postsynaptic part of the synapse, respectively, using the free UTHSCSA ImageTool program (University of Texas). Digital images were taken with the same threshold of the camera, and the observer was blind to the genotype.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that NMDA receptors cocluster with NCAM at the surface of hippocampal neurons. Fig. S2 shows efficiency of protein solubilization with 1% NP-40. Fig. S3 shows that expression of NMDA receptors is increased in NCAM−/− brains. Fig. S4 shows that NMDA receptors colocalize with NCAM at the surface of transfected CHO cells. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200604145/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Jon S. Morrow, Gregory A. Dekaban, and Lynda Hawkins for the spectrin, HA-NR1-1, and NR2B-Flag constructs; Drs. Robert J. Wenthold and Hans-Jürgen Kreienkamp for the antibodies against NR1, GluR1, GluR2/3, and Shank; and Dr. Harold Cremer for NCAM−/− mice. We are also grateful to Ute Eicke-Kohlmorgen, Achim Dahlmann, and Eva Kronberg for technical assistance, genotyping, and animal care.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SY43/2-1 to V. Sytnyk, I. Leshchyns'ka, and M. Schachner) and the Zonta Club Hamburg-Alster (I. Leshchyns'ka).

V. Sytnyk and I. Leshchyns'ka contributed equally to this paper.

Abbreviations used in this paper: LTP, long-term potentiation; NCAM, neural cell adhesion molecule; NMDA, N-methyl-d-aspartate; PSD, postsynaptic density.

References

- Allison, D.W., A.S. Chervin, V.I. Gelfand, and A.M. Craig. 2000. Postsynaptic scaffolds of excitatory and inhibitory synapses in hippocampal neurons: maintenance of core components independent of actin filaments and microtubules. J. Neurosci. 20:4545–4554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai, M., M. Itokawa, K. Yamada, T. Toyota, M. Arai, S. Haga, H. Ujike, I. Sora, K. Ikeda, and T. Yoshikawa. 2004. Association of neural cell adhesion molecule 1 gene polymorphisms with bipolar affective disorder in Japanese individuals. Biol. Psychiatry. 55:804–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodrikov, V., I. Leshchyns'ka, V. Sytnyk, J. Overvoorde, J. den Hertog, and M. Schachner. 2005. RPTPα is essential for NCAM-mediated p59fyn activation and neurite elongation. J. Cell Biol. 168:127–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozdagi, O., M. Valcin, K. Poskanzer, H. Tanaka, and D.L. Benson. 2004. Temporally distinct demands for classic cadherins in synapse formation and maturation. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 27:509–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukalo, O., N. Fentrop, A.Y.W. Lee, B. Salmen, J.W.S. Law, C.T. Wotjak, M. Schweizer, A. Dityatev, and M. Schachner. 2004. Conditional ablation of the neural cell adhesion molecule reduces precision of spatial learning, long-term potentiation, and depression in the CA1 subfield of mouse hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 24:1565–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro, U., J. Niedermeyer, M. Fuxa, and G. Christofori. 2001. N-CAM modulates tumour-cell adhesion to matrix by inducing FGF-receptor signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:650–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti, F., S. DeBiasi, A. Minelli, and M. Melone. 1996. Expression of NR1 and NR2A/B subunits of the NMDA receptor in cortical astrocytes. Glia. 17:254–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer, H., R. Lange, A. Christoph, M. Plomann, G. Vopper, J. Roes, R. Brown, S. Baldwin, P. Kraemer, S. Scheff, et al. 1994. Inactivation of the N-CAM gene in mice results in size reduction of the olfactory bulb and deficits in spatial learning. Nature. 367:455–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derkach, V., A. Barria, and T.R. Soderling. 1999. Ca2+/calmodulin-kinase II enhances channel conductance of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4- isoxazolepropionate type glutamate receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:3269–3274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dityatev, A., G. Dityateva, V. Sytnyk, M. Delling, N. Toni, I. Nikonenko, D. Muller, and M. Schachner. 2004. Polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule promotes remodeling and formation of hippocampal synapses. J. Neurosci. 24:9372–9382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink, C.C., and T. Meyer. 2002. Molecular mechanisms of CaMKII activation in neuronal plasticity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 12:293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong, D.K., A. Rao, F.T. Crump, and A.M. Craig. 2002. Rapid synaptic remodeling by protein kinase C: reciprocal translocation of NMDA receptors and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II. J. Neurosci. 22:2153–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadmon, G., A. Kowitz, P. Altevogt, and M. Schachner. 1990. Functional cooperation between the neural adhesion molecules L1 and N-CAM is carbohydrate dependent. J. Cell Biol. 110:209–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai, S.L., S.C. Ling, L.H. Kuo, Y.C. Shu, W.Y. Chow, and Y.C. Chang. 1998. Characterization of granular particles isolated from postsynaptic densities. J. Neurochem. 71:1694–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis, D.M., and T.S. Reese. 1983. Cytoplasmic organization in cerebellar dendritic spines. J. Cell Biol. 97:1169–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, A.S., K.U. Bayer, M.A. Merrill, I.A. Lim, M.A. Shea, H. Schulman, and J.W. Hell. 2002. Regulation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II docking to N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors by calcium/calmodulin and alpha-actinin. J. Biol. Chem. 277:48441–48448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshchyns'ka, I., V. Sytnyk, J.S. Morrow, and M. Schachner. 2003. Neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) association with PKCβ2 via βI spectrin is implicated in NCAM-mediated neurite outgrowth. J. Cell Biol. 161:625–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman, J., H. Schulman, and H. Cline. 2002. The molecular basis of CaMKII function in synaptic and behavioural memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3:175–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthl, A., J.P. Laurent, A. Figurov, D. Muller, and M. Schachner. 1994. Hippocampal long-term potentiation and neural cell adhesion molecules L1 and NCAM. Nature. 372:777–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIlhinney, R.A., B. Le Bourdelles, E. Molnar, N. Tricaud, P. Streit, and P.J. Whiting. 1998. Assembly intracellular targeting and cell surface expression of the human N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits NR1a and NR2A in transfected cells. Neuropharmacology. 37:1355–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchiodi-Albedi, F., M. Ceccarini, J.C. Winkelmann, J.S. Morrow, and T.C. Petrucci. 1993. The 270 kDa splice variant of erythrocyte β-spectrin (beta I sigma 2) segregates in vivo and in vitro to specific domains of cerebellar neurons. J. Cell Sci. 106:67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Matteis, M.A., and J.S. Morrow. 2000. Spectrin tethers and mesh in the biosynthetic pathway. J. Cell Sci. 113:2331–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migaud, M., P. Charlesworth, M. Dempster, L.C. Webster, A.M. Watabe, M. Makhinson, Y. He, M.F. Ramsay, R.G. Morris, J.H. Morrison, et al. 1998. Enhanced long-term potentiation and impaired learning in mice with mutant postsynaptic density-95 protein. Nature. 396:433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, D., C. Wang, G. Skibo, N. Toni, H. Cremer, V. Calaora, G. Rougon, and J.Z. Kiss. 1996. PSA-NCAM is required for activity-induced synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 17:413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, R.J., D. Xu, R.S. Petralia, O. Steward, R.L. Huganir, and P. Worley. 1999. Synaptic clustering of AMPA receptors by the extracellular immediate-early gene product Narp. Neuron. 23:309–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passafaro, M., C. Sala, M. Niethammer, and M. Sheng. 1999. Microtubule binding by CRIPT and its potential role in the synaptic clustering of PSD-95. Nat. Neurosci. 2:1063–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persohn, E., C.E. Pollerberg, and M. Schachner. 1989. Immunoelectron-microscopic localization of the 180 kD component of the neural cell adhesion molecule N-CAM in postsynaptic membranes. J. Comp. Neurol. 288:92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai-Nair, N., A.K. Panicker, R.M. Rodriguiz, K.L. Gilmore, G.P. Demyanenko, J.Z. Huang, W.C. Wetsel, and P.F. Maness. 2005. Neural cell adhesion molecule-secreting transgenic mice display abnormalities in GABAergic interneurons and alterations in behavior. J. Neurosci. 25:4659–4671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinder, J.C., and A.J. Baines. 2000. A protein accumulator. Nature. 406:253–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollerberg, G.E., M. Schachner, and J. Davoust. 1986. Differentiation state-dependent surface mobilities of two forms of the neural cell adhesion molecule. Nature. 324:462–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollerberg, G.E., K. Burridge, K.E. Krebs, S.R. Goodman, and M. Schachner. 1987. The 180-kD component of the neural cell adhesion molecule N-CAM is involved in a cell-cell contacts and cytoskeleton-membrane interactions. Cell Tissue Res. 250:227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saghatelyan, A.K., A.G. Nikonenko, M. Sun, B. Rolf, P. Putthoff, M. Kutsche, U. Bartsch, A. Dityatev, and M. Schachner. 2004. Reduced GABAergic transmission and number of hippocampal perisomatic inhibitory synapses in juvenile mice deficient in the neural cell adhesion molecule L1. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 26:191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santuccione, A., V. Sytnyk, I. Leshchyns'ka, and M. Schachner. 2005. Prion protein recruits its neuronal receptor NCAM to lipid rafts to activate p59fyn and to enhance neurite outgrowth. J. Cell Biol. 169:341–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosshauer, B. 1989. Purification of neuronal cell surface proteins and generation of epitope-specific monoclonal antibodies against cell adhesion molecules. J. Neurochem. 52:82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, T., M. Krug, H. Hassan, and M. Schachner. 1998. Increase in proportion of hippocampal spine synapses expressing neural cell adhesion molecule NCAM180 following long-term potentiation. J. Neurobiol. 37:359–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, K., and T. Meyer. 1999. Dynamic control of CaMKII translocation and localization in hippocampal neurons by NMDA receptor stimulation. Science. 284:162–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, L., F. Liang, L.D. Walensky, and R.L. Huganir. 2000. Regulation of AMPA receptor GluR1 subunit surface expression by a 4.1 N-linked actin cytoskeletal association. J. Neurosci. 20:7932–7940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S.H., Y. Hayashi, R.S. Petralia, S.H. Zaman, R.J. Wenthold, K. Svoboda, and R. Malinow. 1999. Rapid spine delivery and redistribution of AMPA receptors after synaptic NMDA receptor activation. Science. 284:1811–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sytnyk, V., I. Leshchyns'ka, M. Delling, G. Dityateva, A. Dityatev, and M. Schachner. 2002. Neural cell adhesion molecule promotes accumulation of TGN organelles at sites of neuron-to-neuron contacts. J. Cell Biol. 159:649–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sytnyk, V., I. Leshchyns'ka, A. Dityatev, and M. Schachner. 2004. Trans-Golgi network delivery of synaptic proteins in synaptogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 117:381–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valtschanoff, J.G., and R.J. Weinberg. 2001. Laminar organization of the NMDA receptor complex within the postsynaptic density. J. Neurosci. 21:1211–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vawter, M.P., A.L. Howard, T.M. Hyde, J.E. Kleinman, and W.J. Freed. 1999. Alterations of hippocampal secreted N-CAM in bipolar disorder and synaptophysin in schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 4:467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vawter, M.P., N. Usen, L. Thatcher, B. Ladenheim, P. Zhang, D.M. VanderPutten, K. Conant, M.M. Herman, D.P. van Kammen, G. Sedvall, et al. 2001. Characterization of human cleaved N-CAM and association with schizophrenia. Exp. Neurol. 172:29–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virmani, T., W. Han, X. Liu, T.C. Sudhof, and E.T. Kavalali. 2003. Synaptotagmin 7 splice variants differentially regulate synaptic vesicle recycling. EMBO J. 22:5347–5357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.X., R.J. Wenthold, O.P. Ottersen, and R.S. Petralia. 1998. Endbulb synapses in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus express a specific subset of AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunits. J. Neurosci. 18:1148–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, A., and V.I. Teichberg. 1998. Brain spectrin binding to the NMDA receptor is regulated by phosphorylation, calcium and calmodulin. EMBO J. 17:3931–3939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziff, E.B. 1997. Enlightening the postsynaptic density. Neuron. 19:1163–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, H., S.T. Winokur, W.L. Kuo, M.R. Altherr, and D.S. Bredt. 1997. Actinin-associated LIM protein: identification of a domain interaction between PDZ and spectrin-like repeat motifs. J. Cell Biol. 139:507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.