Abstract

The d(TTGGGGGGTACAGTGCA) sequence, derived from the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) central DNA flap, can form in vitro an intermolecular parallel DNA quadruplex. This work demonstrates that the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein (NCp) exhibits a high affinity (108 M–1) for this quadruplex. This interaction is predominantly hydrophobic, maintained by a stabilization between G-quartet planes and the C-terminal zinc finger of the protein. It also requires 5 nt long tails flanking the quartets plus both the second zinc-finger and the N-terminal domain of NCp. The initial binding nucleates an ordered arrangement of consecutive NCp along the four single-stranded tails. Such a process requires the N-terminal zinc finger, and was found to occur for DNA site sizes shorter than usual in a sequence-dependent manner. Concurrently, NCp binding is efficient on a G′2 quadruplex also derived from the HIV-1 central DNA flap. Apart from their implication within the DNA flap, these data lead to a model for the nucleic acid architecture within the viral nucleocapsid, where adjacent single-stranded tails and NCp promote a compact assembly of NCp and nucleic acid growing from stably and primary bound NCp.

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) RNA genome is packed into viral particles by interactions with the C-terminal domain of the Gag precursor (1). Then, the mature virion core is generated with the non-cooperative coating of viral RNA by nucleocapsid protein (NCp) after proteolytic cleavage of the Gag precursor into its different subunit proteins, matrix (MA), capsid (CA), NCp and other polypeptides (2–4). In addition to its architectural role in virus formation, NCp also exhibits nucleic acids annealing and strand transfer stimulation properties that enhance both initiation and development of reverse transcription (5–12, reviewed in 13–15). This chaperone activity is closely related to the ability of NCp to bind, accelerate and promote annealing of nucleic acids to favor the most stable hybrids (8,9,13–18).

NCp tightly binds to single-stranded nucleic acids (RNA or DNA), oligonucleotides, and to a lesser extent to dsDNA. The binding mode includes both sequence-specific and non-specific interactions, involving both electrostatic and hydrophobic contributions (19–22). The dissociation constant observed for the interaction of mature NCp with single-stranded nucleic acids is in the submicromolar range, although binding of the Gag precursor to RNA appears to be stronger (20). At saturating levels and moderate ionic strength the nucleic acid binding site size of mature NCp(1–55) in vitro is generally 5–8 nt (20). NCp is a small basic polypeptide with a central globular domain containing two zinc-finger structures linked by a basic RAPRKKG sequence (Fig. 1A) (13,23). These zinc-finger domains, which dictate specificity for the viral RNA, are associated with a non-structured and basic N-terminal domain, which is responsible for non-specific binding (24). The zinc-finger structures arise from the zinc-mediated folding of the two highly conserved Cys–His motifs of the form C-aa2-C-aa4-H-aa4-C (CCHC), which leads to the formation of similar structures despite their different amino acid compositions (15,25,26). Binding of zinc directs a well defined folding of the CCHC motifs, as well as the exposure to the solvent of two aromatic amino acids, 16Phe and 37Trp, localized respectively in the N-terminal and the C-terminal finger (27–28). These amino acids, especially 37Trp, are able to participate in stacking interactions with nucleic acid bases, and are thus the stronger elements involved in the specific binding to nucleic acid lattices (19,27–29). Zinc ejection by oxidative components (30–31), deletion of one finger or mutation of a cysteine to serine in either finger causes a decrease in RNA packaging, and loss of nucleic acid binding and annealing activities (8,16,32). Consequently, the correct folding of the zinc fingers and of the aromatic amino acids is a crucial determinant for viral replication.

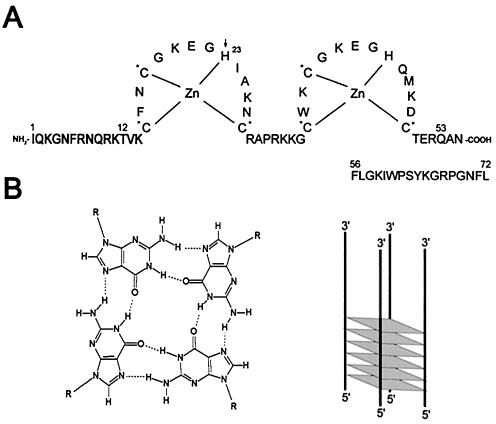

Figure 1.

Proteins and DNA. (A) Amino acid sequence and the two zinc-finger structure of HIV-1 NCp(1–55) used in this study (pNL4-3 isolate, GenBank accession no. AF324493). NCp(1–72) and NCp(12–53) are from the HX10 isolate (GenBank accession no. M15654). NCpcys is the H23C mutant (indicated by an arrow) (36); NCpser contains the SSHS mutations in both CCHC motifs (asterisk) (8). (B) G-quartet (left) and schematic organization of a parallel G-quadruplex containing six G-quartets (right).

It has been previously reported that NCp assists reverse transcriptase (RT) in vitro during the strand displacement synthesis that generates the HIV-1 central DNA flap (33). This suggests that some NCp units remain in close contact with the viral DNA after reverse transcription is completed. The HIV-1 central DNA flap contains two 99 nt long (+) strand overlaps, whose single-stranded nature may trap NC proteins. In an attempt to probe a specific binding of mature NCp(1–55) on these strands, we were surprised to find that NCp preferentially recognized the G-quadruplex structures we have recently observed in vitro from the d(5′-TTGGGGGTA CAGTGCA-3′) and d(5′-TTGGGGGTACAGTGCAGGG GAAA-3′) sequences (ODN1 and ODN2, respectively), which correspond to the first 17 and 24 nt of the 5′ tail of the (+) downstream strand of the HIV-1 central DNA flap (34). These quadruplexes are characterized by the association of two (ODN2) or four (ODN1) separate strands, held together by the hydrophobic stacking of planar Hoogsteen hydrogen-bounded DNA base quartets (G-quartets, Fig. 1B) (reviewed in 35). This report investigates the status of the complexes that are formed between NCp(1–55) and these G-quadruplexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The reagents used in this study correspond to the best grade available and were purchased from established manufacturers. Recombinant wild-type NCp(1–55) (8) as well as NCpser (SSHS) (8) and NCpcys (H23C) (36) mutants were expressed and purified as previously described. NCp derivatives p(12–53) and p(1–72) were obtained from B. Roques (Faculté de Pharmacie, Paris). The 3.3 kb circular ssDNA was prepared and purified as previously described (33). The pTZ-18R dsDNA plasmid was a gift from C. Esnault (IGM, Orsay). The 415mer RU5 RNA was provided by J.-L. Darlix (ENS, Lyon).

DNA oligonucleotides

16b8 is a pyrimidine oligonucleotide [d(5′-TCCTCCTTT TCCTCCT-3′)] used for comparison with ODN1. F21T is a fluorescently labeled G-rich oligonucleotide [fluorescein-d(GGGTTAGGGTTAGGGTTAGGG)-tetramethylrhodamine] used for the standard G-quadruplex melting fluorescence assay as described by Mergny et al. (37). Other sequences are listed in Table 1. DNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Eurogentec (Belgium) and diluted in water.

Table 1. Sequences and structural requirements for NCp binding.

| Upstream tails | G-quartets | Downstream tails | Complex I | Complex II | Complex III | Complex IV | Complex V and superior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | TACAGTGCA | + | + | + | – | – |

| AA | G-G-G-G-G-G | TACAGTGCA | + | + | + | – | – |

| ACGTGACAT | G-G-G-G-G-G | TT | + | + | + | – | – |

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | – | – | – | – | – | |

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | T | – | – | – | – | – |

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | TG | – | – | – | – | – |

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | TGT | – | – | – | – | – |

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | TGTG | – | – | – | – | – |

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | TGTGT | + | – | – | – | – |

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | TGTGTGTG | + | + | – | – | – |

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | TGTGTGTGTG | + | + | + | – | – |

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | TGTGTGTGTGTGTG | + | + | + | + | |

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | (TG)10 | + | + | + | + | NR |

| TGTGT | G-G-G-G-G-G | TT | + | – | – | – | – |

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | AAAATGTGTGTG | + | – | – | – | – |

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | TGTGAAAATGTG | + | – | – | – | – |

| TT | G-G-G-G-G-G | TGTGTGTGAAAA | + | + | – | – | – |

The purified quadruplex form of each oligonucleotide was tested for binding activities under the conditions in Figure 6. NR (non-resolvable) indicates that the complexes formed are migrating as smearing species.

G-quadruplexes

Parallel G-quadruplex DNA was prepared by interstrand association of oligonucleotides (30 µM) incubated in 200 mM KCl at 40°C for 30 h. ODN2 G′2 DNA was formed using ODN2 (30 µM) incubated in 250 mM KCl/TE at 35°C for 45 h. Samples were electrophoresed on 8% non-denaturing polyacrylamide mini-gels containing 20 mM KCl. Bands corresponding to quadruplexes were identified according to their gel mobility by UV-shadowing and excised. DNA was eluted from the crushed gel slices by soaking in 0.5 M potassium acetate/1 mM EDTA at 37°C for 8–12 h, and purified with the Ultrafree-DA DNA extraction kit (Millipore) coupled to Microcon 10 (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA concentrations were quantified at 260 nm in a Genequant microspectrophotometer (APBiotech). Quadruplexes were 5′ end-labeled using [γ-33P]ATP (ICN) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). Denaturation of quadruplexes to their corresponding monomers was performed by alkaline denaturation using 70 mM sodium hydroxide (34).

Fluorescence measurements

Fluorescence emission spectra were recorded at 30°C with a 295 nm excitation on a Spex DM1 Fluorimeter (Jobin-Yvon SA), using a bandwidth of 4 nm and 0.2 × 1 cm path-length quartz cuvettes, containing 60 µl of solution in a pH 7.1, 0.5 M KCl, 10 mM sodium cacodylate buffer. DNA samples were added to a 1 µM solution of NCp(1–55). Fifteen minutes after each addition, a fluorescence emission spectrum was recorded. The melting behavior of the G-rich oligonucleotide F21T in the presence of increasing concentrations of NCp was assayed as described by Mergny et al. (37).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

Unless otherwise indicated, the standard buffer (10 µl) for the DNA-binding assay contained 5–15 nM of 33P-labeled nucleic acids in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2 and NCps at the indicated concentrations. Proteins were diluted in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.9), 30 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 3 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 10% glycerol. Reactions were performed at 37°C for 15 min. Samples were loaded onto 14% polyacrylamide/1% glycerol (29:1, polyacrylamide:bisacrylamide; Promega) gels in 0.5× TBE [0.45 M Tris-borate (pH 8.3), 0.5 mM EDTA], using a 10.5 × 10 cm mini-gel apparatus (Hoefer SE-250) connected to a cold circulating bath. The gels were run at 8–10 V/cm at room temperature. Gels were scanned using a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) and the bands were quantified using ImageQuant software. The fraction of bound DNA was determined as the ratio between each shifted band and the total number of counts in each lane. Equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) were estimated from protein concentrations at which half the total DNA is bound. Binding kinetics were assayed by immediately loading the samples onto a pre-running gel. To assay the effect of competitors (Figs 3C and 6), the labeled DNA probe and serial dilutions of unlabeled competitors were premixed in the standard assay buffer prior to the addition of NCp. Zn2+ ejection by EDTA was performed by pre-incubating the diluted protein for 10 min at 37°C. For the experiment in Figure 7B, SDS was added to 0.2% (w/v) final concentration after the binding reaction, and the sample was incubated for 10 min at 30°C.

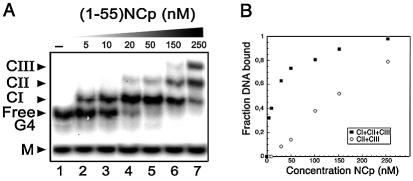

Figure 3.

Binding of NCp(1–55) to ODN1. (A) EMSA of NCp binding to the G-quadruplex form of ODN1 (T-ODN1; G4) or the unfolded monomer (M). The fractionation of complexes was carried out in a 14% non- denaturing polyacrylamide gel at 20°C. DNA concentration was fixed at 5 nM. Lanes 1–7 correspond to protein concentrations of 0, 5, 10, 20, 50, 150 and 250 nM, respectively. (B) Apparent equilibrium binding curves were obtained by calculating the fraction of T-OND1 bound at the various NCp concentrations. Squares, total shifted bands; circles, sum of CII and CIII. Total and bound DNA were quantitated as described in Materials and Methods.

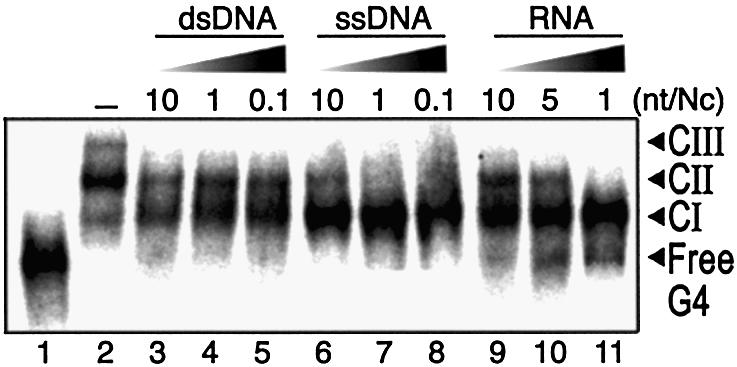

Figure 6.

Competition assay of NCp(1–55) binding to T-ODN1. Samples containing 15 nM of labeled T-ODN1 and increasing concentrations of unlabeled competitors were assayed for binding using 400 nM NCp(1–55). Added amounts of competitors are expressed as the number of nucleotides per NCp. Substrates are a 2.9 kb dsDNA plasmid (lanes 3–5), a 3.3 kb circular ssDNA (lanes 6–8) and a 415mer RNA containing the HIV-1 R/U5 sequence (lanes 9–11). Incubation was performed in 0.2 M NaCl.

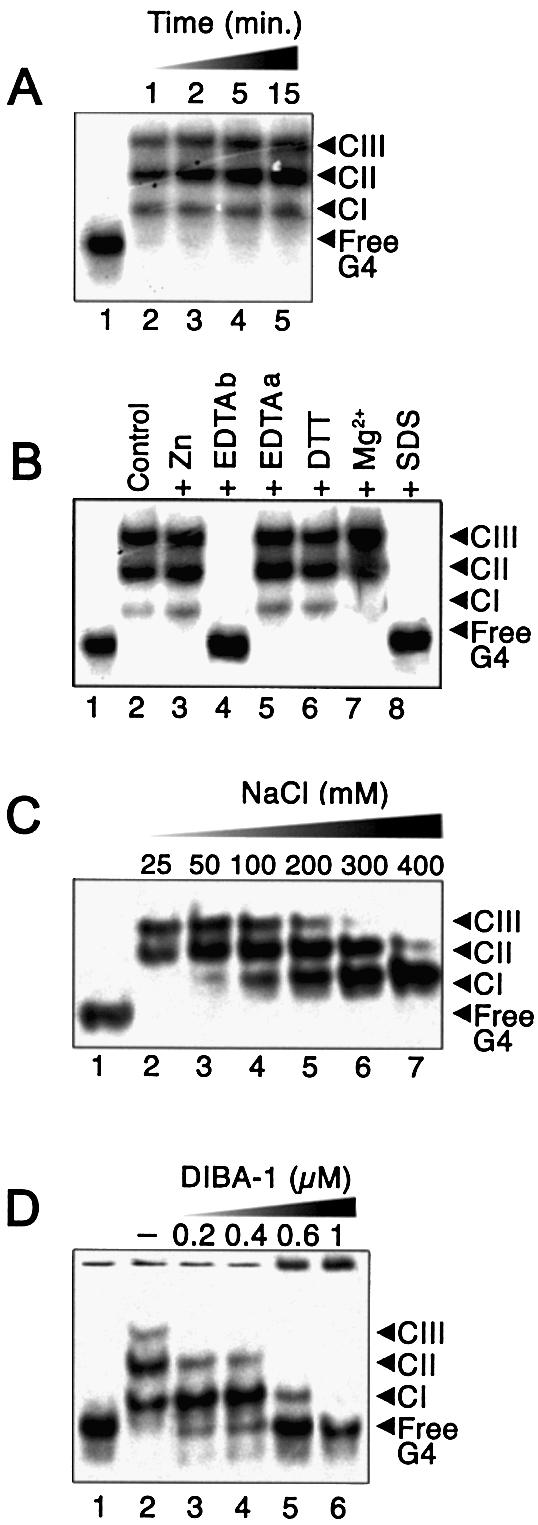

Figure 7.

Characterization of binding of NCp(1–55) to T-ODN1. Reactions were carried out in a standard assay buffer (10 µl) containing 10 nM of 33P-labeled T-ODN1 and 400 nM NCp(1–55), plus the indicated additional treatments, as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Kinetics of NCp binding to T-ODN1 with no added constituents. (B) Complex formation in the presence of zinc (10 mM), EDTA (10 mM) added before (EDTAb) or after (EDTAa) the reaction, DTT (10 mM), MgCl2 (10 mM) or 0.2% SDS. (C) Effect of NaCl added at the indicated concentrations. (D) Binding reaction (30 min) performed in the presence of DIBA-1 at the indicated concentrations using 15 nM T-ODN1 and 250 nM NCp(1–55) in 0.2 M NaCl. Lane 1, no protein added.

RESULTS

Preferential binding of G-quadruplex by recombinant NCp(1–55)

Fluorescent spectroscopy has been applied in a number of instances to the study of NCp–nucleic acid interactions since complex formation produces a shift in the intrinsic fluorescence of 37Trp (28). To initially investigate relevant sequence discrimination of mature NCp(1–55) for the overlapping (+) strands of the HIV-1 central DNA flap, NCp fluorescence emission measurements were performed at high ionic strength (0.5 M KCl) in the presence of the various DNA sequences (data not shown). Surprisingly, we observed that the G-quadruplex form of ODN1 (T-ODN1, 5′-TTGGGGG GTACAGTGCA-3′) efficiently quenched (>70%) 37Trp fluorescence, suggesting that NCp may interact with quadruplexes. ODN1 represents the immediate downstream (+) strand sequence that emerges from viral dsDNA during RT-mediated strand displacement synthesis. In contrast, a much weaker quenching was obtained in the presence of 16b8, a single-stranded pyrimidine oligonucleotide (data not shown). To confirm this preference towards oligonucleotides containing G-quartets, a fluorescence assay based on G-quadruplex binding was performed (37), using the thermal denaturation profile of an intramolecular quadruplex in the presence of various amounts of NCp (Fig. 2). Sub-micromolar concentrations of the peptide significantly stabilized the quadruplex, leading to a 5 or 16°C increase in melting temperature at a 0.2 and 0.4 µM NCp concentration, respectively. These stabilization values are in the same range as those obtained with 1 µM of specific G-quadruplex ligands (37,38), and therefore suggest a strong interaction between the protein and the quadruplex. Higher concentrations of NCp (1 µM) induced an aggregation of the quadruplex (Fig. 2, diamonds).

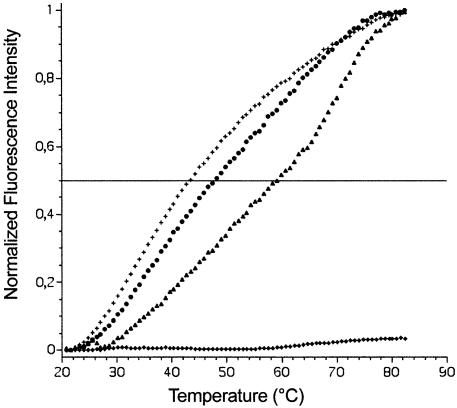

Figure 2.

Fluorescence melting experiments. Thermal melting of a fluorescently labeled G-rich oligonucleotide (F21T, 0.2 µM strand concentration) that forms an intramolecular quadruplex (37) was assessed in the presence of 0.2 (circles), 0.4 (triangles) or 1 µM (diamonds) NCp(1–55) in a 10 mM sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2), with 0.1 M LiCl. Crosses, oligonucleotide alone. Excitation was set at 470 nm and emission was recorded at 520 nm. Denaturation of the quadruplex, which leads to a fluorescence emission increase at 520 nm occurred at higher temperatures in the presence of 0.2 and 0.4 µM NCp. At 1 µM NCp concentration, aggregation/precipitation of the complex prevented an accurate measurement of the melting process.

These preliminary observations drove us to probe NCp(1–55) binding to ODN1 and its G-quadruplex counterpart using electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA). These substrates were tested separately for complex formation with increasing concentrations of NCp incubated while keeping the DNA constant (Fig. 3A). This experiment revealed that although no DNA shift was observed with ODN1, T-ODN1 was totally converted into a discrete, shifted complex [complex I (CI), Fig. 3A, lane 4] when incubated with nanomolar amounts of NCp. At higher NCp concentrations, two other shifted bands of lower mobility (CII and CIII, lanes 5–7) appeared with a concomitant reduction of CI, suggesting a multiple and ordered mechanism of NCp binding on the G-quadruplex. The apparent dissociation constants were determined to be Kd ∼ 9 nM for CI, and Kd ∼ 98 nM for the sum of CII and CIII (see Fig. 3B and Materials and Methods), which points towards T-ODN1 as the best substrate to date for limited NCp binding on DNA.

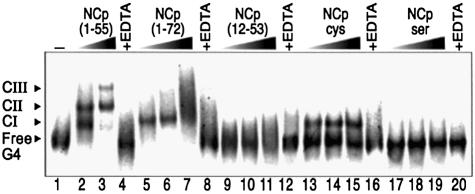

NCp domain mapping for the quadruplex-binding activity

Variant NC proteins were assayed for their binding on T-ODN1 (Fig. 4). The first peptide used was an intermediate product of Gag processing, NCp(1–72). Under conditions of maximal binding for NCp(1–55), NCp(1–72) forms a complex that co-migrates with NCp(1–55)/CI (lanes 5–6). Thereafter, NCp(1–72)/T-ODN1 complexes form smeared species above CI (lane 7), which shows that the additional C-terminal (56–72) domain strongly decreases the stability of larger complexes and inhibits, in cis, further discrete and sequential binding. The second peptide used was NCp(12–53) which lacks the wild-type basic N-terminal domain. As shown in lanes 9–10, NCp(12–53) does not form well defined complexes with T-ODN1, suggesting that the two zinc fingers are not sufficient for stable and discrete binding. Next, we tested recombinant (1–55) NCpcys and NCpser mutants. In the first protein, the CCHC motif in the N-terminal finger is substituted by a CCCC motif (8) which can be found in cellular zinc-finger proteins. Although this modification does not alter zinc coordination, the mutated virus is replication defective even though it packages significant levels of genomic RNA (32,39). In our system, NCpcys binds T-ODN1 in the first complex of the same mobility as CI formed with NCp(1–55). Remarkably, it was unable to form CII and CIII. The second mutant contains two fingers where tight zinc coordination was eliminated by changing all of the cysteine residues in both fingers to serine (SSHS) (36). Such modifications impair RNA packaging and, to a lesser extent, the chaperone activity (16). Here, NCpser failed to form any nucleoprotein complex (lanes 17–19), which emphasizes the critical contribution of the two correctly folded zinc fingers for binding activity on T-ODN1. As shown in lanes 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20, a pre-treatment of NCp(1–55) with EDTA generates a zinc-free apoprotein (40), which suppressed any binding to T-ODN1. Taken together, these data indicate that NCp binding on T-ODN1 requires a combination of a full-sized N-terminal domain linked to a native C-terminal finger to obtain the first complex. In addition, the N-terminal finger is crucial and the extended C-terminal domain appears to be detrimental to the stabilization of the well ordered, multi-NCp units in CII and CIII.

Figure 4.

NCp domain mapping for T-ODN1 binding activity using EMSA. Labeled T-ODN1 is 15 nM (lane 1). Lanes 2–3, binding reaction using 20 and 400 nM NCp(1–55), respectively. Next, concentrations of NCp(1–72) (lanes 5–7), NCp(12–53) (lanes 9–11), NCpcys (lanes 13–15) and NCpser (lanes 17–19) are 50, 200 and 400 nM, respectively. Lanes 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20, NCp(1–55), (1–72), (12–53), NCpcys and NCpser, respectively, pre- incubated with 10 mM EDTA for 10 min at 37°C (for 400 nM final concentration of protein).

Sequence and structural requirements for NCp binding

NCp is known to have a far higher affinity for d(TG)n than for d(A)n sequences. Thus, it is now established that while the electrostatic interaction between the basic protein and these two sequences is equivalent, there is a significant additional non-ionic component of the binding of NCp to d(TG)n, mainly due to 37Trp stacking with guanine bases (19). To test whether the single-stranded domain of the quadruplexes may have such an influence on binding, a set of oligonucleotides containing a G6 motif and tails of various sequences and lengths were synthesized (Table 1). Their tetramer forms (T-forms) were purified, radiolabeled and direct binding rather than band competition was used to probe complex formation. Figure 5A shows that NCp(1–55) binds to the quadruplex d[T2G6(TG)7] as strong as it binds to T-ODN1, leading to the formation of four discrete complexes (Kd ∼ 8 nM for CI; Kd ∼ 80 nM for the other complexes). Interestingly, the monomeric form of d[T2G6(TG)7] was also bound by NCp, but with moderate affinity. In contrast, the quadruplex of the d(T2G6A14) sequence engaged only one complex (Fig. 5B), weaker than the one observed with T-ODN1 (Kd ∼ 25 nM). Taken together, these experiments indicate an ordered two-step complexation pathway: the first event of binding, which only depends on the presence of a G-quartet motif and not of the sequence of its surrounding single-stranded tails, followed by a second event where sequences and the lengths of the tails are determinants. We next tested whether NCp was able to bind quadruplexes independently of the orientation of the single-stranded tails. As shown in Figure 5C, NCp binds a d(ACGTGACATG6 TACATGTCA) quadruplex in a complex manner since it first forms two consecutive major complexes (lanes 2–3) and a higher molecular weight species that could not be observed as discrete complexes (lane 4). In contrast, NCpcys only forms the two first complexes (lanes 5–7) with the d(ACGTGACATG6 TACATGTCA) quadruplex. These results suggest that these complexes are made of NCp bound to each terminal G-quartet since NCp(1–55) is able to form larger complexes with increasing protein concentrations, whereas NCpcys only forms smaller complexes with increasing protein concentration. This shows again that a single His–Cys substitution in the N-terminal zinc finger is sufficient to avoid NCp assembly upon the tails.

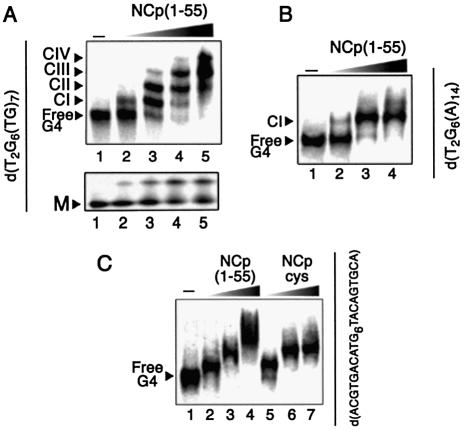

Figure 5.

EMSA of NCp(1–55) binding to quadruplexes containing tails of various lengths and sequences. (A) Binding to the quadruplex form of d[T2G6(TG)7] (top; G4) or its unfolded monomer M (bottom). The DNA concentration was fixed at 12 nM. Lanes 1–5 correspond to protein concentrations of 0, 20, 100, 200 and 500 nM, respectively. (B) Binding to the quadruplex form of d(T2G6(A)14). Lanes 1–4 correspond to protein concentrations of 0, 20, 100 and 400 nM, respectively, for a fixed DNA concentration of 15 nM. (C) Binding to the quadruplex form of d(ACGTGACATG6TACAGTGCA). The DNA concentration was fixed at 10 nM. Lane 1, no protein added; other lanes contain 50, 100 and 400 nM protein, respectively, using NCp(1–55) (lanes 2–4) or NCpcys (lanes 5–7).

Further results were obtained in binding experiments using quadruplexes of d(TG) tails of various lengths and sequences (Table 1). First, we successfully probed a binding comparable with those of ODN1 using its inverted counterpart d(5′-ACGTGACATG6T2-3′), which confirms that complex stabilization was not dependent on the orientation of the single-stranded tails. Replacement of two As for the two wild-type Ts at the 5′ end does not alter binding as well, suggesting that binding at the 5′ end requires more than two bases to occur. Effectively, the next data set indicates that besides the G-quartet core, at least five protruding nucleotides are needed for efficient formation of CI, and the number of TG residues required for the formation of CII is even higher. The addition of two other TG bases results in the stable formation of CIII. It should be noted that we were not able to confidently probe more than four stable complexes for quadruplexes containing more than 15 nt long single-stranded tails {see d[T2G6(TG)10]}, since smeared species (similar to those observed in lane 4 of Fig. 5C) indicative of increasingly larger complexes could not be resolved. Such a result may indicate that the ordered association along the single-stranded tails is difficult to extend properly over increasingly longer ranges. This may be due to a progressive decrease in binding stability or to other complicated events that result in non-specific DNA binding. Finally, we observed that addition of d(A) sequences disrupted the ordered mechanism, showing that this assembly was dependant on the specific sequence of the tails. Notably, the first complex formed when five As joined to the quadruplex did not allow further assembly even though they were followed by TG tails. This subtle effect strongly suggests some overlapping of the CI- and CII-associated NCp along the DNA, highlighting therefore a tight assembly of NCp along the four tails.

Biochemical requirements for NCp binding

To further explore the specificity of NCp interactions with quadruplexes, we assayed the binding of protein to T-ODN1 under various conditions. Initially, binding was tested in competition experiments with various unlabeled competitors (circular ssDNA, circular dsDNA, ssRNA) that were added at the same time as T-ODN1. As shown in Figure 6, binding was not suppressed by increasing amounts of the circular dsDNA. Such results suggest that NCp bound in CII and CIII have a higher affinity for those DNA sites than for any site present in the dsDNA plasmid used here. On the other hand, the addition of ssDNA competed effectively for CII and CIII formation, whereas CI remained resistant even to a large excess of competitor (lane 8). The addition of a 415mer HIV-1 RU5 RNA also competed efficiently for CII and CIII but did not disrupt the stabilization of CI (lanes 9–11). Therefore, the affinity of NCp directly associated with the DNA quadruplex is much stronger than any site present in both the 3.3 kb ssDNA and the HIV-derived RNA used here.

Other parameters controlling NCp binding were explored by varying the reaction conditions. Figure 7A shows that binding had already occurred strongly within the briefest incubation period tested (1 min) and did not change appreciably with longer incubations. We also explored the effect of added zinc ion, DTT, EDTA and magnesium (Fig. 7B). The addition of zinc (lane 2) or DTT (lane 6) did not alter binding, while magnesium increased slightly the yield of CII and CIII (lane 7). As shown before, pre-incubation with 10 mM EDTA dramatically prevents any binding (lane 4). However, this effect was not observed when binding was assayed in the presence of 10 mM EDTA. This result indicates that binding of NCp to T-ODN1 protects the zinc fingers against zinc ejection. Finally, it can also be seen here that complexes were absent if the reaction mixture was treated with 0.2% SDS (lane 8), which confirms that EMSA probes effectively nucleoprotein complexes and also that NCp binding does not alter quadruplex structure. Next, the effect of ionic strength was tested for saturating levels of NCp (Fig. 7C): although the addition of NaCl below 0.2 M had no effect, CIII formation was abolished at 0.3 M NaCl, followed by CII at 0.4 M NaCl, whereas CI remained strongly salt resistant. Such a result suggests that CI stability is largely governed by hydrophobic interactions, although CII and CIII could be more weakly bound to T-ODN1 with both tight hydrophobic and efficient electrostatic contributions. Moreover, it confirms the ordered mechanism of NCp binding on these substrates.

It has been shown that disulfide-substituted benzamides compounds (DIBAs) covalently modify zinc-coordinating cysteine thiolates of the NCp zinc fingers, causing zinc ejection, loss of native protein structure and nucleic acid binding ability (30). The effect of DIBA-1 (31) on binding to T-ODN1 was evaluated. As seen in Figure 7D, an approximately equal molarity of DIBA-1 with protein caused a significant decrease in CIII, CII and CI. For higher concentrations, a significant fraction of the labeled quadruplex failed to migrate beyond the gel well (lanes 5–6), suggesting the formation of an insoluble aggregate, since DIBA-1 is known to generate intermolecular disulfide bridges within a mixture of NCp (31). On the other hand, limited concentrations of DIBA-1 only inhibited formation of CII and CIII, confirming the differences in stabilities for NCp assembly on T-ODN1. Therefore, this binding assay appears to be a very convenient way to quantify NCp inhibition, since G-quadruplexes very efficiently bind NCp in a number of discrete complexes, some of which are very sensitive to alterations to NCp.

Binding of G′2-hairpin dimer by NCp

The d(5′-TTGGGGGGTACAGTGCAGGGGAAA-3′) sequence, corresponding to the first 24 nt of the 5′ tail of the HIV-1 central DNA flap (i.e. ODN1 + GGGGAAA), can also form G-quartet-mediated products, and especially a G′2-hairpin dimer (34) that we have also tested for NCp binding. This is reported in Figure 8, where a fixed concentration of a purified radiolabeled G′2 (D-form) of ODN2 sequence was incubated in the presence of increasing amounts of NCp. Like T-ODN1, but with a far lower affinity (Kd ∼ 270 nM), D-ODN2 was partially converted into a shifted complex (CI, lane 2) followed by a second one for higher amounts of protein (lanes 3–5). The same experiment showed that, in the presence of 0.4 M NaCl, only the formation of CI (lanes 7–9) occurred, and similar results were obtained using the H23C mutant at lower ionic strength (NCpcys, lanes 11–13). Thus, even though we do not yet know the spatial arrangement of the strands in the G′2 used here, it seems quite clear that the presence of two 9 nt long DNA hairpins is sufficient for CI formation and a second binding on the tails. This second complex could be reinforced by the presence of the trinucleotide TGT at the probable position of the loop, which itself inhibits further binding on the tails. Once again, the N-terminal zinc finger is a key element for progression of multiple binding in this system.

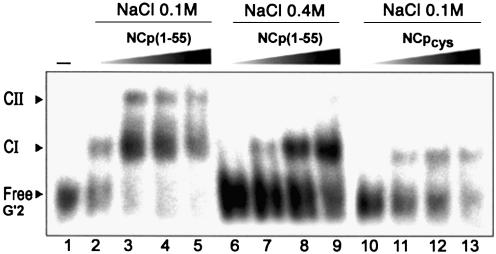

Figure 8.

EMSA of NCp binding to a G′2 DNA (D-ODN2). Complexes were resolved on a 15% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel at 20°C. The DNA concentration was fixed at 20 nM. Lane 1, no protein added; other lanes contain 250 nM, 500 nM, 750 nM and 1 µM protein, respectively, using NCp(1–55) in a standard assay buffer containing 0.1 M NaCl (lanes 2–5) or 0.4 M NaCl (lanes 6–9), or using NCpcys in 0.1 M NaCl (lanes 10–13).

DISCUSSION

Dimeric G′2 and parallel four-stranded G-quadruplex DNA with short single-stranded tails are shown here to bind multiple NCps, describing a unique ordered mechanism of a sequential and compact assembly of NCp along a nucleic acid. Such a discrete assembly with NCp allowed us to study the critical properties of both the protein and the DNA required to promote it. The use of EMSA without any special electrophoresis techniques highlights the very stable nature of this assembly, especially for the first complex that is formed with the parallel quadruplex (CI species). These results are reminescent of the binding of the ssDNA-binding gene 5 protein of filamentous bacteriophage fd to parallel G-quadruplex structures (41).

The unique feature of parallel G-quadruplexes is the association of four separate strands held together by the hydrophobic stacking of large, planar hydrogen-bonded DNA base quartets coordinated with a monovalent cation (Fig. 1B) (42–44). The observed dissociation constant (∼9–10 nM) for the CI species with T-ODN1 is the lowest described for NCp interaction with nucleic acids of such a short size (17mer). An explanation for this strong binding is that the G-quartet structure offers an extraordinarily attractive site for hydrophobic stacking with the aromatic residues contained in the zinc fingers of the protein. The preference of NCp for single-stranded nucleic acids principally involves its zinc fingers and is largely governed by hydrophobic interactions of 16Phe and 37Trp with bases. In addition, electrostatic interactions between charged residues probably govern the non-specific binding via the N-terminal domain of the protein (4,19,24,28). The NMR structures of NCp(1–55) bound to a 20 nt RNA containing the Ψ-SL3 motif (24) and NCp (1–72) bound to d(5′-ACGGC-3′) sequence (45) show that 37Trp in the C-terminal zinc finger directly interacts with a guanine base, which is in line with studies that detect a strong preference of NCp for G over other bases (19). Taken together, these data may explain the nature of the first complex selected in the present study. Several proteins have already been reported to bind such DNA structures (reviewed in 35,46). In many cases, it has been suggested that G-quadruplexes also present an array of phosphates that are highly favorable for non-specific binding by the basic domains of these proteins.

The absence of binding of both zinc-free apoprotein and the NCpser mutant, as well as DIBA-1 disruption of binding confirmed the crucial role of native zinc fingers in the formation of CI. This points to the 37Trp, if exposed to the solvent by a correct folding of the C-terminal zinc finger, as the amino acid that is interacting with the G-quartet. This is in complete agreement with the general model in which this amino acid interacts with nucleic acids (4,13,28). Moreover, evidence for this hydrophobic interaction is supported since the first complex (CI) is resistant to up to 0.4 M NaCl. However, binding to T-ODN1 requires more than just the G-quartet core since on the 3′ or 5′ end, at least five nucleotides were necessary on the protruding single-stranded tails for efficient complex formation (Table 1). This number, which corresponds to the binding site size of NCp on short oligonucleotides (18–19), shows that, to be efficient, the highly stable CI requires a second interaction between NCp and the adjacent single-stranded tails. This takes place without any sequence specificity or directionality. This could also explain the lower affinity observed for the G′2 quadruplex (Fig. 8) where both loops access the G-quartet plane and the absence of symmetry in the spatial arrangement of the tails should certainly minimize CI over-stabilization. One explanation is that the interaction between the G-quartet and the C-terminal zinc finger may orient the N-terminal domains of the polypeptide towards one of the four protruding single-stranded tails of the quadruplex, and not toward the G-quartet core. This implies that any dissociation event of the basic domain with DNA should be rapidly compensated by re-capture of one of the other negatively charged single-stranded tails via a rotational permutation of the 37Trp within a G-quartet plane. Such a system may be the major stabilization force for CI formation, as the NCp(12–53) lacking the N-terminal domain is not able to form this particular complex under our conditions. It has been suggested that a single NCp molecule can simultaneously bind or cross-link two oligonucleotides (18). Fisher et al. (19) have observed that NCp binds more stably to oligonucleotides that are in close spatial proximity, as a consequence of their attachment on the same streptavidine molecule on Biacore chips. It is possible that the sugar-phosphate backbone of adjacent strands emerging from the quadruplex are about the right distance apart to occupy two sites for one unit of NCp, and, therefore with four tails, two NCps per G-quartet. Development of probing experiments based on protein cross-linking are currently in progress to confirm this possibility.

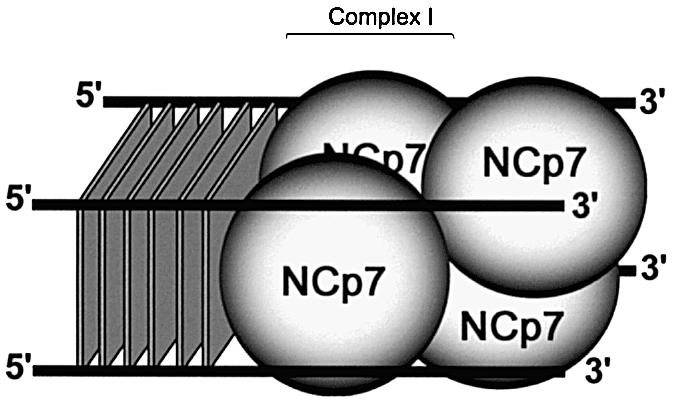

Our data also indicate a two-step model for NCp attachment to quadruplexes containing single-stranded tails that are longer than five bases. According to the binding model proposed by Oliver et al. (41) for the binding of fd gene 5 protein to quadruplexes, the G-quartet core may serve to nucleate cooperative binding of stalled NCp along the protruding single-stranded tails, with a strong dependency on the primary sequences of the tails. The number of these complexes rises with an increase in the length of the tails, to a maximum of 15 bases for observable binding (Fig. 5A). This binding is sequence dependent, and is dramatically more efficient with parallel tails, and also when these tails contain TG rather than A sequences. Such an observation correlates with sequence preferences already observed for NCp with nucleic acids. Interestingly, binding on external TG sequences are inhibited by the insertion of As (Table 1). Moreover, ssDNA and RNA efficiently compete for these complexes. In the case of T-ODN1, NCp has ∼10-fold less affinity to form CII than CI. The enhanced sensitivities to ionic strength for the formation of slower migrating complexes (CII, CIII, …) also indicate weaker binding and different structural interfaces compared with CI. This could involve electrostatic, non-ionic as well as weak hydrophobic interactions. If the first complex occupies two NCp units and five nucleotides on the single-stranded tails of the quadruplex, a simple side-by-side (longitudinal) attachment of NCp along these tails does not allow the formation of the two additional complexes on the four remaining nucleotides for T-ODN1, as well as for the d[T2G6(TG)7] sequence. Even though we do not yet know the NCp stoichiometry within the assembled complexes CII and CIII, postulating that two NCp units can bind on the same surface of the quadruplex covering the 5 nt long tails, we propose a model where two diametrically opposed NCp units bind to one quadruplex substrate. Consequently, this would orient the two independent N-terminal domains along the single-stranded tails. Taking into account that the first five nucleotides direct the formation of the first complex, while only four more nucleotides are sufficient to form both the second and the third complex, the larger complexes could be formed with incoming NCp units stabilized upon two free interspersed DNA lattices by an upstream interaction with the previous bound protein(s). This event could then be reinforced by binding of each NCp to two single-stranded tails, and/or by lateral protein–protein interactions between neighboring proteins. Such lateral interactions may be relevant to the self-association properties described by Zabransky et al. (47) for the following NC domain: the N-terminal domain plus N-terminal zinc finger. An illustration of the proposed assembly is presented in Figure 9. Nevertheless, this data confirms that the binding of NCp to nucleic acids is polarized (28). Requirements for the N-terminal zinc finger as a crucial domain to allow such interactions are highlighted by the failure of the NCpcys mutant to promote these secondary complexes, when it can form the initial one. Partially processed NCp in its C-terminal domain [NCp(1–72)] is not efficient in promoting the proper assembly of CI, when it favors DNA aggregation. This suggests that complete NCp processing may be an important factor to promote an ordered coating of NCp along the RNA, with a strong influence of the N-terminal zinc finger.

Figure 9.

Proposed model of ordered binding of NCp7 on quadruplex depending on the anchorage onto G-quartets. Two diametrically opposed NCp may bind to one quadruplex substrate. This binding may orient the two independent N-terminal domains along the single-stranded tails. Next, additional complexes could be formed with incoming NCp units stabilized upon two free interspersed DNA lattices by an upstream interaction with the previous bound protein(s). The two incoming NCp may together cause formation of CII, therefore implying another pair to form CIII. Alternatively, one unit may associate before the other, successively generating CII and CIII.

The exact biological role of G-quadruplex DNA structures remains to be elucidated. The presence of G-quadruplexes in the macronuclei of ciliates was demonstrated with a specific antibody (48). G-quadruplexes have been implicated in HIV-1 RNA dimerization (49) and were recently described to occur between the overlapping strands of the HIV-1 central DNA flap in vitro (34). NCp has been shown to activate synthesis of the central DNA flap during HIV-1 reverse transcription (33). As discussed before (34), one can imagine a stabilizing effect, or capping of NCp on transient G-quartet structures induced in the DNA flap, a hypothesis that is reinforced by the binding to the G′2 DNA related to the central DNA flap. Such a property should have a positive effect within the preintegration steps. G-quartet structures in the central portion of the HIV genome may also be involved in virion particle structure, where it should be associated with both RNA dimerization and nucleoprotein core assembly. A discrete number of NCp units trapped within each nucleoprotein complex is the original aspect of the system described here. It emphasizes the influence of the single-stranded tails linked to the G-quartets, suggesting therefore that these strands, spatially organized in the quadruplex, may act as a non-resolvable DNA intermediate trapping the NCp chaperone activity in its transition step (18,50). Hence, the parameters governing the NCp–G-quadruplex assembly may be relevant to the biological assembly of mature nucleocapsid in the virion core. Such a stable system provides a simple and useful quantitative method for NCp titration and a powerful tool for biochemical and pharmacological studies. A detailed analysis of this surprisingly efficient in vitro assembly should determine how many NCps are positioned from the G-quartet surface to the tails with respect to the DNA lattices, how each NCp is oriented with respect to one another and what are the molecular interactions that promote the ordered mechanism. Such a simple and controlled assembly of NCps and nucleic acids should serve as a model to decipher how 2000 NCp units and two RNA molecules (representing 18 500 nt) generate a highly compact nucleoprotein core that is internalized within the mature viral capsid structure. A redistribution of NCp along the two RNA copies during viral maturation after Gag processing may direct nucleocapsid assembly and RNA compaction via anchorage of processed NCp to some preferential RNA secondary structures that stabilize a transversal and ordered cooperation of overlapping NCp, discretely associated with ssRNA.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank B. Roques for the gift of NCp(1–72) and NCp(12–53), J.-L. Darlix for the 415mer RNA, C. Esnault (IGM, Orsay) for dsDNA plasmid, S. Lafosse and J. Jeusset (IGR, Villejuif) for ssDNA phagemid, J.-F. Mouscadet (ENS, Cachan) for DIBA-1 compound and Anthony Justome for helpful assistance. S.L. is the recipient of a fellowship from ANRS. G.M. is Assistant Professor at the Université Pierre et Marie Curie (ParisVI). The work was supported by grants from ANRS and from ARC 4321 to J.-L.M. It was also supported in part by the National Cancer Institute under contract no. N01-CO-12400 with SAIC Frederick, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clever J., Sasseti,C. and Parslow,T.G. (1995) RNA secondary structure and binding sites for gag gene products in the 5′ packaging signal of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol., 69, 2101–2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henderson L.E., Bowers,M.A., Sowder,R.C., Serabyn,S.A., Johnson,D.G., Bess,J.W., Arthur,L.O., Bryant,D.K. and Fenselau,C. (1992) Gag protein of the highly replicative MN strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: posttranslational modifications, proteolytic processing and complete amino acid sequences. J. Virol., 66, 1856–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mervis R.J., Ahmad,N., Lillehoj,E.P., Raum,M.G., Salazar,F.H.R., Chan,H.W. and Venkatesan,S. (1988) The gag gene products of human immunodeficiency virus t-type 1: alignment within the gag open reading frame, identification of posttranslational modifications and evidence for alternative gag precursors. J. Virol., 62, 3993–4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urbaneja M.A., Kane,B.P., Johnson,D.G., Gorelick,R.J., Henderson,L.E. and Casas-Finet,J.R. (1999) Binding properties of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein p7 to a model RNA: elucidation of the structural determinants for function. J. Mol. Biol., 287, 59–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darlix J.L., Vincent,C., Gabus,C., De Rocquigny,H. and Roques,B.P. (1993) Trans-activation of the 5′ to 3′ viral DNA strand transfer by nucleocapsid protein during reverse transcription of HIV-1 RNA. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris Life Sci., 316, 763–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeStefano J.J. (1995) Human immunodeficiency virus nucleocapsid protein stimulates strand transfer from internal regions of heteropolymeric RNA templates. Arch. Virol., 140, 1775–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo J., Henderson,L.E., Bess,J.W., Kane,B.F. and Levin,J.G. (1997) Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein promotes efficient strand transfer and specific viral DNA synthesis by inhibiting TAR-dependant self-priming from minus-strand strong-stop DNA. J. Virol., 71, 5178–5188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo J., Wu,T., Anderson,J., Kane,B.F., Johnson,D.G., Gorelick,R.J., Henderson,L.E. and Levin,J.G. (2000) Zinc finger structures in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein facilitate efficient minus- and plus-strand transfer. J. Virol., 74, 8980–8988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lapadat-Tapolsky M., Pernelle,C., Borie,C. and Darlix,J.L. (1995) Analysis of the nucleic acid annealing activities of nucleocapsid protein from HIV-1. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 2434–2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez-Rodriguez L.Z., Tsuchihashi,Z., Fuentes,G.M., Bambara,R.A. and Fay,P.J. (1995) Influence of human immudeficiency virus nucleocapsid protein on synthesis and strand transfer by the reverse transcriptase in vitro. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 15005–15011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peliska J.A., Balasubramanian,D.P., Giedroc,D.P. and Benkovic,S.J. (1994) Recombinant HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein accelerates HIV-1 reverse transcriptase catalyzed DNA strand transfer reactions and modulates RNase H activity. Biochemistry, 33, 13817–13823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.You J.C. and Mc Henry,C.S. (1994) Human immudeficiency virus nucleocapsid protein accelerates strand transfer of the terminally redundant sequences involved in reverse transcription. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 31491–31495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darlix J.L., Lapadat-Tapolsky,M., de Rocquigny,H. and Roques,B.P. (1995) First glimpses at structure–function relationships of the nucleocapsid protein of retroviruses. J. Mol. Biol., 254, 523–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herschlag D. (1995) RNA chaperones and the RNA folding problem. J. Biol. Chem., 270, 20871–20874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rein A., Henderson,L.E. and Levin,J.G. (1998) Nucleic-acid-chaperone activity of retroviral nucleocapsid proteins: significance for viral replication. Trends Biochem. Sci., 23, 297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo J., Wu,T., Kane,B.F., Johnson,D.G., Henderson,L.E., Gorelick,R.J. and Levin,J.G. (2002) Subtle alterations of the native zinc finger structures have dramatic effects on the nucleic acid chaperone activity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol., 74, 4370–4378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuchihashi Z. and Brown,P.O. (1994) DNA strand exchange and selective DNA annealing promoted by the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol., 68, 5863–5870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urbaneja M.A., Wu,M., Casas-Finet,J.R. and Karpel,R.L. (2002) HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein as a nucleic acid chaperone: spectroscopic study of its helix-destabilizing properties, structural binding specificity and annealing activity. J. Mol. Biol., 318, 749–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher R.J., Rein,A., Fivash,M., Urbaneja,M.A., Casas-Finet,J.R., Medaglia,M. and Henderson,L.E. (1998) Sequence-specific binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein to short oligonucleotides. J. Virol., 72, 1902–1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karpel R.L., Henderson,L.E. and Oroszlan,S. (1987) Interaction of retroviral structural proteins with single-stranded nucleic acids. J. Mol. Biol., 262, 4961–4967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan R. and Giedroc,D.P. (1994) Nucleic acid binding properties of recombinant Zn2 HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein are modulated by COOH-terminal processing. J. Biol. Chem., 269, 22538–22546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu J.Q., Ozarowski,A., Maki,A.H., Urbaneja,M.A., Henderson,L.E. and Casas-Finet,J.R. (1997) Binding of the nucleocapsid protein of type 1 human immunodeficiency virus to nucleic acids studied using phosphorescence and optically detected magnetic resonance. Biochemistry, 36, 12506–12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coffin J.M., Hughes,S.H. and Varmus,H.E. (1997) Retroviruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Guzman R.N., Rong Wu,Z., Stalling,C.C., Pappalardo,L., Borer,P.N. and Summers,M.F. (1998) Structure of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein bound to the SL3-RNA recognition element. Science, 279, 384–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mély Y., de Rocquigny,H., Morellet,N., Roques,B.P. and Gérard,D. (1996) Zinc binding to the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein: a thermodynamic investigation by fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochemistry, 35, 5175–5182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.South T.L., Blake,P.R., Hare,D.R. and Summers,M.F. (1991) C-terminal retroviral-type zinc finger domain from the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein is structurally similar to the N-terminal zinc finger domain. Biochemistry, 30, 6342–6349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorfman T., Luban,J., Goff,S.P., Haseltine,W.A. and Gottlinger,H.G. (1993) Mapping of functionally important residues of a cysteine–histidine box in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol., 67, 6159–6169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vuilleumier C., Bombarda,E., Morellet,N., Gérard,D., Roques,B.P. and Mély,Y. (1999) Nucleic acid sequence discrimination by the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein NCp7: a fluorescence study. Biochemistry, 38, 16816–16825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dannull J., Surovoy,A., Jung,G. and Moelling,K. (1994) Specific binding of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein to PSI RNA in vitro requires N-terminal zinc finger and flanking basic amino acid residues. EMBO J., 13, 1525–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loo J.A., Holler,T.P., Sanchez,J., Gogliotti,R., Maloney,L. and Reily,M.D. (1996) Biophysical characterization of zinc ejection from HIV nucleocapsid protein by anti-HIV 2,2′-dithiobis [benzamides] and benzisothiazolones. J. Med. Chem., 39, 4313–4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rice W.G., Supko,J.G., Malspeis,L., Buckheit,R.W., Clanton,D., Bu,M., Graham,L., Schaeffer,C.A., Turpin,J.A., Domagale,J., Gogliotti,R., Bader,J.P., Halliday,S.M., Coren,L., Sowder,R.C., Arthur,L.O. and Henderson,L.E. (1995) Inhibitors of HIV nucleocapsid protein zinc fingers as candidates for the treatment of AIDS. Science, 270, 1194–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorelick R.J., Gagliardi,T.D., Bosche,W.J., Wiltrout,T.A., Coren,L.V., Chabot,D.J., Lifson,J.D., Henderson,L.E. and Arthur,L.O. (1999) Strict conservation of the nucleocapsid protein zinc finger is strongly influenced by its role in viral infection processes: characterization of HIV-1 particles containing mutant nucleocapsid zinc-coordinating sequences. Virology, 256, 92–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hameau L., Jeusset,J., Lafosse,S., Coulaud,D., Delain,E., Unge,T., Restle,T., Le Cam,E. and Mirambeau,G. (2001) Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 central DNA flap: dynamic terminal product of plus-strand displacement DNA synthesis catalyzed by reverse transcriptase assisted by nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol., 75, 3301–3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyonnais S., Hounsou,C., Teulade-Fichou,M.-P., Jeusset,J., Le Cam,E. and Mirambeau,G. (2002) G-quartets assembly within a G-rich DNA flap. A possible event at the center of the HIV-1 genome. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 5276–5283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simonsson T. (2001) G-quadruplex DNA structures—variations on a theme. Biol. Chem., 382, 621–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carteau S., Gorelick,R.J. and Bushman,F.D. (1999) Coupled integration of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cDNA by purified integrase in vitro: stimulation by the viral nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol., 73, 6670–6679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mergny J.L., Lacroix,L., Teulade-Fichou,M.P., Hounsou,C., Guittat,L., Hoarau,M., Arimondo,P.B., Vigneron,J.-P., Lehn,J.M., Riou,J.F., Garestier,T. and Hélène,C. (2001) Telomerase inhibitors based on quadruplex ligands selected by a fluorescence assay. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 3062–3067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riou J.F., Guittat,L., Mailliet,P., Laoui,A., Renou,E., Petitgenet,O., Megnin-Chanet,F., Hélène,C. and Mergny,J.L. (2002) Cell senescence and telomere shortening induced by a new series of specific G-quadruplex DNA ligands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 2672–2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanchou V., Decimo,D., Péchoux,C., Lener,D., Rogemond,V., Berthoux,L., Ottmann,M. and Darlix,J.L. (1998) Role of the N-terminal zinc finger of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein in virus structure and replication. J. Virol., 72, 4442–4447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chertova E.N., Kane,B.P., McGrath,C., Johnson,D.G., Sowder,R.C., Arthur,L.O. and Henderson,L.E. (1998) Probing the topography of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein with the alkylating agent N-ethylmaleimide. Biochemistry, 37, 17890–17897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliver A.W., Bogdarina,I., Schroeder,E., Taylor,I.A. and Kneale,G.G. (2000) Preferential binding of fd gene 5 protein to tetraplex nucleic acid structures. J. Mol. Biol., 301, 575–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sen D. and Gilbert,W. (1988) Formation of parallel four-stranded complexes by guanine rich motifs in DNA and its implications for meiosis. Nature, 334, 364–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilbert D.A. (1999) Multistranded DNA structures. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 9, 305–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williamson J.R. (1994) G-quartet structures in telomeric DNA. Annu. Rev. Biomol. Struct., 23, 703–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morellet N., Déméné,H., Teilleux,V., Huynh-Dinh,T., de Rocquigny,H., Fournié-Zaluski,M.C. and Roques,B.P. (1998) Structure of the complex between the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein NCp7 and the single-stranded pentanucleotide d(ACGCC). J. Mol. Biol., 283, 419–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rhodes D. and Giraldo,R. (1995) Telomere structure and function. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 5, 311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zabransky A., Hunter,E. and Sakalian,M. (2002) Identification of a minimal HIV-1 gag domain sufficient for self-association. Virology, 294, 141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schaffitzel C., Berger,I., Postberg,J., Hanes,J., Lipps,H.J. and Plückthun,A. (2001) In vitro generated antibodies specific for telomeric guanine-quadruplex DNA react with Stylonychia lemnae macronuclei. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 8572–8577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sundquist W.I. and Heaphy,S. (1993) Evidence for interstrand quadruplex formation in the dimerization of human immunodeficiency virus 1 genomic RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 3393–3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams M.C., Rouzina,I., Wenner,J.R., Gorelick,R.J., Musier-Forsyth,K. and Bloomfield,V.A. (2001) Mechanism for nucleic acid chaperone activity of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein revealed by single molecule stretching. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 6121–6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]