Abstract

Faithful chromosome segregation in mitosis requires the formation of a bipolar mitotic spindle with stably attached chromosomes. Once all of the chromosomes are aligned, the connection between the sister chromatids is severed by the cysteine protease separase. Separase also promotes centriole disengagement at the end of mitosis. Temporal coordination of these two activities with the rest of the cell cycle is required for the successful completion of mitosis. In this study, we report that depletion of the microtubule and kinetochore protein astrin results in checkpoint-arrested cells with multipolar spindles and separated sister chromatids, which is consistent with untimely separase activation. Supporting this idea, astrin-depleted cells contain active separase, and separase depletion suppresses the premature sister chromatid separation and centriole disengagement in these cells. We suggest that astrin contributes to the regulatory network that controls separase activity.

Introduction

To achieve faithful chromosome segregation, a bipolar spindle has to be established. In somatic mammalian cells, the mitotic spindle is nucleated from the two centrosomes, each consisting of two closely associated (engaged) centrioles surrounded by pericentriolar material. During exit from mitosis, the two centrioles separate, and this centriole disengagement is a prerequisite for the centriole duplication in the next cell cycle and, therefore, is tightly regulated (Tsou and Stearns, 2006). However, under some circumstances, premature disengagement of the centrioles can occur, leading to multipolar spindles and mitotic defects (Keryer et al., 1984; Sluder and Rieder, 1985; Hut et al., 2003).

Along with the formation of the mitotic spindle, stable attachments of the chromosomes to the microtubules and their alignment at the metaphase plate have to be achieved. Once all of the chromosomes are aligned, the connection between the sister chromatids is severed by the cysteine protease separase (Uhlmann et al., 2000; Waizenegger et al., 2000). Up to that point, separase activity is held in check both by inhibitory binding of its chaperone securin and Cdk1/cyclin B1 (Ciosk et al., 1998; Gorr et al., 2005; Holland and Taylor, 2006). In turn, the levels of securin and cyclin B1 are controlled by the spindle checkpoint (Musacchio and Hardwick, 2002) that prevents their degradation as long as kinetochore attachment to microtubules and tension across the kinetochores have not been established. Recently, it has been demonstrated that centriole disengagement at the end of mitosis also requires separase (Tsou and Stearns, 2006). Thus, the spindle checkpoint–mediated inhibition of separase protects both sister chromatid cohesion and the connection between engaged centrioles.

In this study, we have analyzed the function of the spindle- and kinetochore-associated protein astrin (Chang et al., 2001; Mack and Compton, 2001; Gruber et al., 2002). We find that in the absence of astrin, kinetochore–microtubule attachments are impaired, resulting in a spindle checkpoint arrest. Fixed and live cell analysis of astrin-depleted cells revealed both a high degree of premature centriole disengagement, resulting in multipolar spindles, and a loss of sister chromatid cohesion. The potential involvement of separase in the origin of these phenotypes is investigated.

Results and discussion

Astrin is a spindle pole and outer kinetochore protein

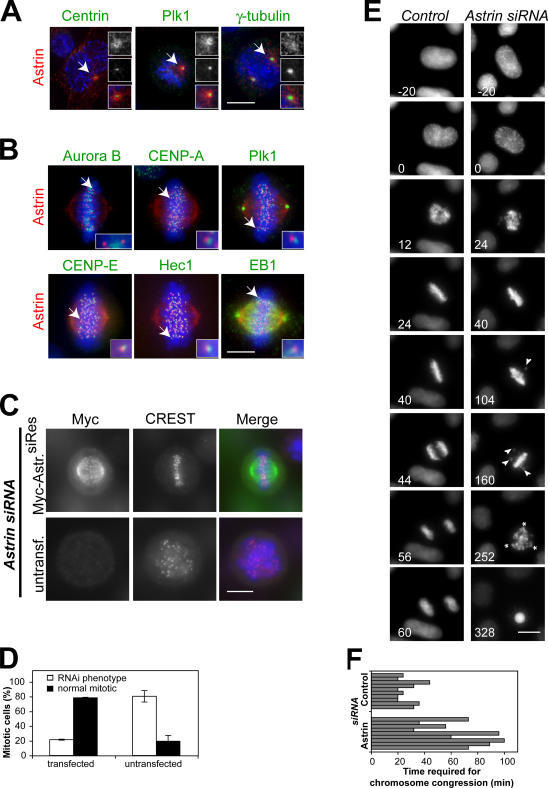

Astrin has previously been described as a spindle-associated protein involved in mitotic progression (Fig. S1, A and B; available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200701163/DC1; Chang et al., 2001; Mack and Compton, 2001; Gruber et al., 2002). During prophase and prometaphase, a centrosomal pool of astrin is diffusely localized to the pericentriolar material and microtubules emanating from the centrosome, overlapping with but distinct from the areas stained by antibodies against Pololike kinase 1 (Plk1), γ-tubulin, and centrin (Fig. 1 A). A second chromosome-associated pool of astrin partially overlaps with the outer kinetochore components Hec1 and centromere protein (CENP) E as well as the microtubule tip-binding protein EB1 but is discrete from other kinetochore proteins such as Plk1 and the centromeric markers aurora B and CENP-A (Fig. 1 B). Therefore, this second pool of astrin is most likely associated with the outer kinetochore. The dual localization of astrin to both centrosomes and kinetochores indicates that it may be required for spindle formation and chromosome segregation.

Figure 1.

Astrin depletion results in impaired chromosome alignment and the formation of multipolar spindles. (A) Pro- and prometaphase HeLa cells were stained with antibodies against astrin and centrin, Plk1, or γ-tubulin. Centrosomes indicated with arrows are shown enlarged in the insets. (B) Metaphase HeLa cells were processed for immunofluorescence using antibodies against astrin and aurora B, CENP-A, Plk1, CENP-E, Hec1, or EB1. The kinetochores indicated with arrows are shown enlarged in the insets. (C) HeLa cells were transfected with myc-astrin constructs containing five silent mutations in the sequence targeted by the astrin siRNA oligonucleotide 24 h before transfection with astrin siRNA oligonucleotides and stained with CREST antiserum and antibodies against myc. (D) The percentage of transfected and untransfected cells displaying the astrin depletion phenotype was scored in two independent experiments. Error bars represent SD. (E) Stills of representative videos of control and astrin-depleted cells. Time is indicated in minutes. All astrin-depleted cells analyzed (n = 10) exhibited delayed chromosome congression (compare t = 24 min in control and astrin siRNA cells) and unstable metaphase plates. Note the unaligned chromosomes in astrin siRNA at t = 104 min and t = 160 min (arrowheads). The depicted astrin-depleted cell is initially bipolar but forms a multipolar spindle (asterisks indicate spindle poles) during the mitotic arrest. (F) Control or astrin-depleted HeLa S3 cells expressing histone-H2B-GFP were followed by live cell analysis. The time required for chromosome congression was plotted. Bars, 10 μm.

Astrin is required for spindle pole integrity and efficient chromosome alignment

Supporting the aforementioned conclusion, the depletion of astrin resulted in an increase in the mitotic index and occurrence of cells with multipolar spindles and disorganized DNA (Fig. S1, C–E). Concomitantly, increased cell death by apoptosis was observed (Fig. S1 F; Gruber et al., 2002). These defects were efficiently rescued by the transfection of cells with siRNA- resistant myc-astrin before siRNA-mediated depletion of endogenous astrin (Fig. 1, C and D) and were not observed upon the depletion of several other outer kinetochore proteins (Fig. S1 G). Further analysis of HeLa-S3 H2B-GFP control cells or astrin-depleted cells by time-lapse imaging showed that astrin-depleted cells also exhibited a profound chromosome alignment defect (Fig. 1 E). Astrin-depleted cells required substantially more time to assemble a metaphase plate than control cells (63.9 ± 28.5 min in comparison with 27.0 ± 8.0 min; Fig. 1 F), and 60% of the cells never accomplished full alignment of all of the chromosomes (Fig. 1 E, right). Once metaphase chromosome alignment was achieved, chromosomes were lost again from this structure (Fig. 1 E, t = 104 min and t = 160 min), and cells remained arrested in a metaphase-like state for prolonged periods of time (up to 10 h) and eventually died by apoptosis.

Although most astrin-depleted cells (8/9) initially formed a bipolar spindle, after several hours of mitotic arrest (194.4 ± 46.5 min), bipolarity was lost, and a multipolar spindle was formed (Fig. 1 E, t = 252 min). In the one remaining case, a multipolar spindle was formed immediately without a preceding period of bipolarity. Together, these data suggest that astrin has functions at both spindle poles and kinetochores and that the lack of astrin leads to a prolonged mitotic arrest.

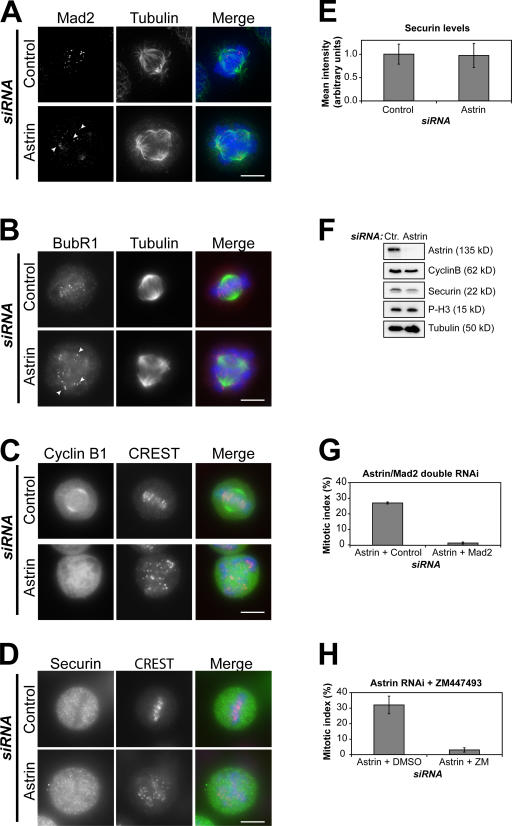

Astrin-depleted cells are spindle checkpoint arrested

Consistent with the observed cell cycle arrest, cells lacking astrin displayed Mad2 and strongly BubR1-positive kinetochores, indicating spindle assembly checkpoint activation (Fig. 2, A and B). These cells also stained brightly for cyclin B1 and securin, with mean pixel intensities similar to mitotic control cells (Fig. 2, C–E), and extracts prepared from them had levels of cyclin B1, securin, and phosphohistone H3 (Ser10) comparable with control nocodazole-arrested cells (Fig. 2 F). Moreover, the mitotic arrest caused by astrin depletion was relieved by the depletion of Mad2 in addition to astrin or the treatment of astrin-depleted cells with the aurora B inhibitor ZM447493, confirming its dependency on the spindle checkpoint (Fig. 2, G and H).

Figure 2.

Astrin-depleted cells are spindle checkpoint arrested. (A–D) Control or astrin-depleted HeLa cells were stained with antibodies against α-tubulin (green) and either Mad2 or BubR1 (red; A and B) or were stained with CREST antiserum (red) and antibodies against cyclin B1 or securin (green; C and D), respectively. Mad2- or strongly BubR1-positive kinetochores are indicated by arrowheads. DNA was visualized with DAPI. (E) The levels of securin staining in control or astrin-depleted mitotic cells were measured in four independent experiments using ImageJ software, analyzing 15–20 cells of each kind per experiment. (F) Lysates of mitotic control and astrin-depleted HeLa cells harvested by mitotic shake off were immunoblotted with antibodies against the indicated proteins. The two astrin bands appear as one because of a higher percentage of SDS gel used. (G) HeLa cells were transfected with astrin siRNA and 16 h later with Mad2 or control siRNA oligonucleotides for an additional 24 h, and the mitotic index was scored. (H) Control or astrin-depleted cells were treated with DMSO or 10 μM ZM447493 for 3 h, and the mitotic index was scored. Error bars represent SD. Bars, 10 μm.

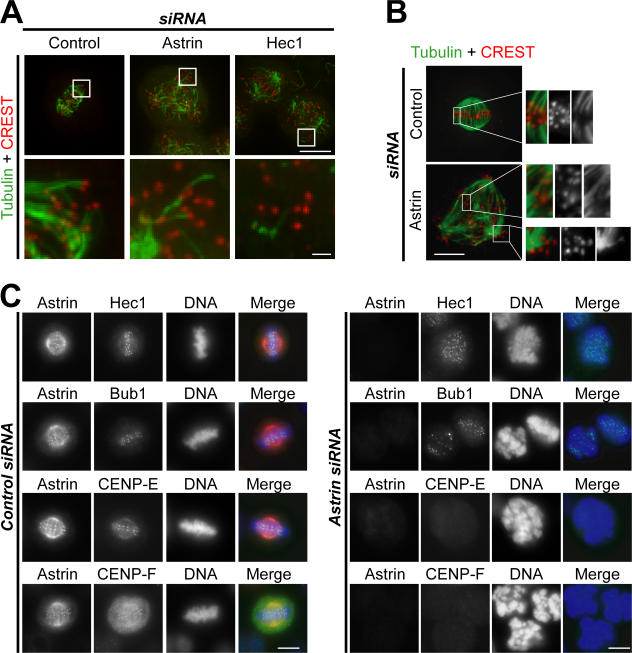

Cells lacking astrin have unstable microtubule–kinetochore interactions

The persistent activation of the spindle checkpoint together with the delay in metaphase plate formation suggested that microtubule–kinetochore interactions require astrin. To test this idea, cells were analyzed after cold treatment (Rieder, 1981) or were preextracted before fixation to differentially preserve kinetochore fibers (Holt et al., 2005). Under both conditions, astrin- depleted cells displayed many unattached kinetochores and fewer stable kinetochore microtubules than control cells, although the phenotype was not as drastic as the one observed in Hec1-depleted cells (Fig. 3, A and B; DeLuca et al., 2002). The kinetochores that were microtubule associated often appeared to be attached laterally rather than end on in cells lacking astrin (Fig. 3 B, bottom; insets). Furthermore, although both the core kinetochore protein Hec1 and the spindle checkpoint kinase Bub1 were unaffected (Fig. 3 C), the kinetochore resident motor protein CENP-E (Yen et al., 1992) and its interaction partner CENP-F (Chan et al., 1998) were delocalized from the kinetochore in the absence of astrin. These cells remained cyclin B1 positive (unpublished data), confirming that they were still in mitosis. These data suggest that the presence of astrin is required for the kinetochore recruitment or maintenance of CENP-E and CENP-F. In combination with the lack of astrin, this may cause unstable microtubule–kinetochore interactions, unaligned chromosomes, and persistent activation of the spindle checkpoint. However, these finding do not explain why multipolar spindles are formed in cells lacking astrin.

Figure 3.

Microtubule–kinetochore interactions are unstable, and outer kinetochore components are mislocalized in astrin-depleted cells. (A) HeLa control cells and astrin- or Hec1-depleted cells were incubated on ice for 20 min before fixation. Cold-stable K-fiber microtubules were revealed by kinetochore staining with CREST serum and antibodies against α-tubulin. The boxed areas are shown magnified in the bottom panels. Note the presence of unattached kinetochores in astrin-depleted cells. Bars (top), 10 μm; (bottom) 1 μm. (B) Control or astrin-depleted HeLa cells were preextracted before fixation, and microtubule–kinetochore interactions were visualized as in A. (C) Control (left) and astrin-depleted HeLa cells (right) were stained for astrin (red) and either Hec1, Bub1, CENP-E, or CENP-F (green). (B and C) Bars, 10 μm.

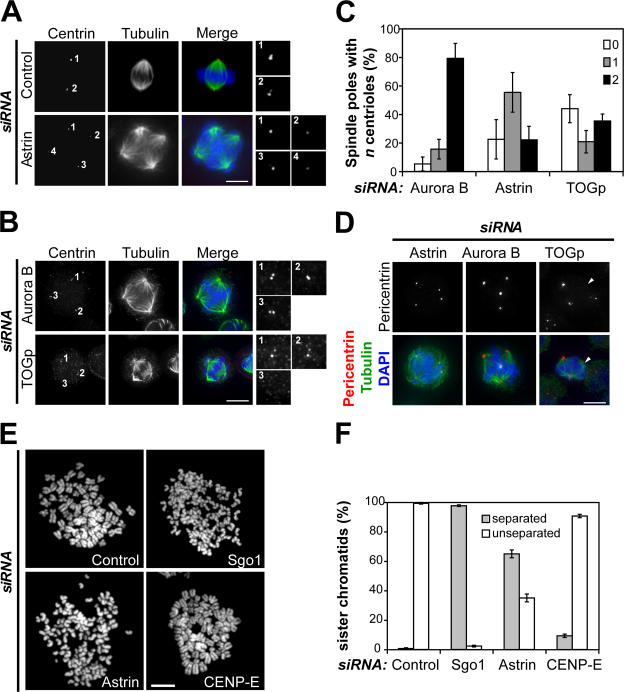

The absence of astrin results in centriole disengagement

To analyze the molecular basis of the multipolar spindle phenotype in more detail, the localization of centrin, a marker for individual centrioles (Paoletti et al., 1996), was investigated in astrin-depleted cells. Multipolar spindles can arise by several different routes that can be distinguished by the number of centrioles found at the individual poles. Failure of cytokinesis will lead to multiple spindle poles with two centrin-positive centrioles at each pole. In contrast, aberrant centriole disengagement will cause the formation of multipolar spindles with single centrioles at individual spindle poles (Keryer et al., 1984; Sluder and Rieder, 1985). A further possible cause for the loss of spindle bipolarity is the loss of microtubule anchoring at the centrosome, which is observed, for instance, upon tumor overexpressed gene protein (TOGp) depletion (Cassimeris and Morabito, 2004; Holmfeldt et al., 2004).

In contrast to the bipolar spindles of control cells, which displayed two centrin dots at each pole, the multipolar spindles in cells lacking astrin often displayed single centrin dots at each pole (Fig. 4 A). For a further quantitative comparison, the number of centrin dots per pole in multipolar cells depleted of aurora B that is known to be required for correct chromosome segregation and progression through cytokinesis (Honda et al., 2003) or TOGp, a protein important for maintaining intact spindle poles (Gergely et al., 2003; Cassimeris and Morabito, 2004; Holmfeldt et al., 2004), was evaluated (Fig. 4, B and C). This approach revealed that 79.2% of multipolar spindles in aurora B–depleted cells displayed two centrin-positive dots per pole (Fig. 4, B [top] and C), which is consistent with the idea that these spindles had arisen from a previous cytokinesis failure. Multipolar spindles in TOGp-depleted cells often showed poles with no centrin staining in addition to two normal poles with two centrin dots and therefore contained the highest number of acentriolar poles (43.9%; Fig. 4, B [bottom] and C). Strikingly, and in contrast to both aurora B and TOGp depletion, in astrin-depleted cells, 55.4% of poles had single centrioles, which is suggestive of aberrant centriole disengagement (Fig. 4 C).

Figure 4.

Astrin depletion causes the loss of centriole and sister chromatid cohesion. (A) Control or astrin-depleted cells were stained with antibodies against centrin (red) and α-tubulin (green). DNA was visualized with DAPI. Individual centrosomes are shown enlarged on the right. (B) HeLa cells depleted of aurora B or TOGp were stained as in A. (C) Quantitative analysis of the centriole number at the poles of multipolar spindles in cells depleted of astrin, aurora B, or TOGp. The number of poles containing no, one, or two centrin stainings was plotted as a percentage of the total number of poles. The cells were analyzed double blind by three different researchers. The graphs represent triplicate experiments of at least 40 cells each. (D) Astrin-, aurora B–, and TOGp-depleted cells were stained with antibodies against pericentrin (red) and α-tubulin (green). The arrowheads indicate acentriolar spindle poles in the TOGp-depleted cell. (E) Chromosome spreads were prepared from mitotic HeLa cells depleted of Gl2 (control), CENP-E (both 48-h RNAi), Sgo1, and astrin (both 40-h RNAi). Representative pictures of each sample are shown. (F) Quantitation of the chromosome spreads shown in E. Each bar represents triplicate experiments. 100 cells of each sample were counted per experiment. Error bars represent SD. Bars, 10 μm.

In line with these data, aurora B and astrin-depleted cells generally displayed pericentrin staining at all poles of multipolar spindles, whereas TOGp-depleted cells often possessed multipolar spindles with only two pericentrin-positive poles, confirming published results (Fig. 4 D; Holmfeldt et al., 2004). Collectively, these results suggest that the formation of multipolar spindles upon astrin depletion is mainly caused by an untimely loss of the connection between the two centrioles of each centrosome.

In normal cells, the connection between the two centrioles is lost at the end of mitosis or early G1 phase, when the two centrioles are disengaged. It has recently been demonstrated that this disengagement of the two centrioles is dependent on the activity of separase (Tsou and Stearns, 2006), a protease that also controls cohesin cleavage between sister chromatids (Uhlmann et al., 2000). One possible explanation for the formation of multipolar spindles in cells depleted of astrin could therefore be an inefficient inhibition of separase during the checkpoint arrest, leading to premature disengagement of the centrioles. In this case, one would predict that cohesion between sister chromatids would also be affected.

Consistent with this idea, immunofluorescence analysis of cells or single chromosomes showed that the chromosomes of mitotically arrested astrin-depleted cells displayed single dots of CREST staining, which is indicative of separated sister chromatids, in comparison with paired dots in metaphase control cells (Fig. S2, A and B; available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200701163/DC1). Furthermore, 65.0% of mitotic chromosomes in chromosome spreads prepared from astrin-depleted cells displayed separated sister chromatids compared with <1.0% of control cell spreads, 97.7% of chromosome spreads of Sgo1-depleted cells, which are known to display a loss of sister chromatid cohesion (McGuinness et al., 2005), and 9.3% of spreads of CENP-E–depleted cells (Fig. 4, E and F; and Table I; Tanudji et al., 2004). Time-lapse analysis of astrin-depleted cells expressing YFP-tagged CENP-A showed that these cells established and maintained cohesion normally in early mitosis through to the formation of (imperfect) metaphase plates but lost cohesion during subsequent mitotic arrest, on average 89.6 ± 42.3 min (n = 10) after forming a metaphase (like) plate (Fig. S2 C). This loss of cohesion was not caused by lack of the centromeric protector Sgo1 (Fig. S2 D). In summary, the data obtained from imaging histone H2B-GFP or CENP-A–YFP expressing astrin-depleted cells indicate that loss of sister chromatid cohesion precedes loss of centrosome integrity in these cells but that both events occur after the formation of an imperfect metaphase plate.

Table I.

Analysis of centrosome integrity and sister chromatid cohesion in spindle checkpoint–arrested cells

| Treatment | Separated chromatids |

Mitotic index |

Multipolar/ mitotic cellsa |

Poles with a single centrioleb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astrin siRNAc | 65.0 ± 2.6 | 16.2 ± 2.0 | 67.3 ± 2.1 | 55.4 ± 13.9 |

| CENP-E siRNA | 9.3 ± 1.2 | 26.3 ± 3.2 | 12.8 ± 3.7 | 16.3 ± 4.8 |

| Nocodazole (16 h)d | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 52.7 ± 2.9 | 23.0 ± 2.0 | 28.7 ± 10.2 |

Mitotic cells = 100%.

Percentage of poles with a single centriole relative to all poles in multipolar spindles.

Live cell imaging showed that mitotic arrest lasts for ∼10 h before apoptosis occurs.

Cells were synchronized with aphidicolin for 16 h, released for 6 h, and blocked in mitosis for 16 h by adding nocodazole. For the immunofluorescence analysis of mitotically arrested cells, the cells were released into fresh medium for 40 min to allow formation of a mitotic spindle.

To confirm that loss of centriole and sister chromatid cohesion was a specific effect of astrin depletion rather than an indirect effect of the prolonged mitotic arrest, cells depleted of CENP-E by RNAi or treated after presynchronization with nocodazole for 16 h, both causing extended mitotic arrest, were analyzed (Table I). Although both treatments resulted in a moderate increase in multipolar cells (12.8 ± 3.7% and 23.0 ± 2.8%, respectively), this did not seem to have been caused by centriole disengagement (Table I). Furthermore, neither CENP-E–depleted nor nocodazole-treated cells displayed a substantial loss of sister chromatid cohesion after extended periods of mitotic arrest (Fig. 4, E and F; and Table I). In summary, astrin depletion causes unique defects (67.3 ± 2.1% of multipolar mitotic cells and 65.0 ± 2.6% of separated sister chromatids) that cannot be phenocopied by forcing cells into extended mitotic arrest by other means.

Separase-dependent loss of spindle bipolarity and sister chromatid cohesion in astrin-depleted cells

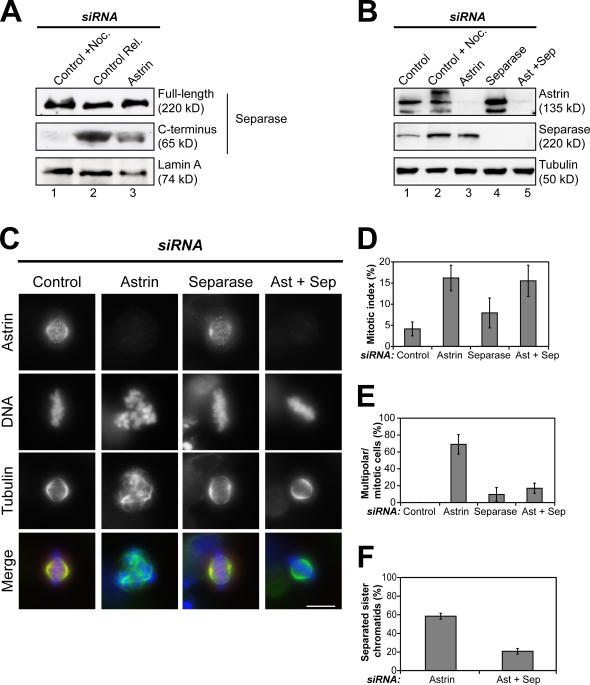

Separation of the sister chromatids in cells lacking astrin would be consistent with the premature activation of separase. This hypothesis was tested by exploiting the fact that active separase undergoes self-cleavage, resulting in a 65-kD C-terminal fragment (Waizenegger et al., 2002). Extracts prepared from mitotically arrested or mitotically arrested and released cells were used to create situations in which separase was either inactive (mitotic arrest) or active (release from mitotic arrest). Immunoblotting revealed the presence of a C-terminal cleavage product only in the control cells that had been released from the mitotic block (Fig. 5 A, compare lane 1 with lane 2). Importantly, in extracts prepared from astrin-depleted cells, the C-terminal separase cleavage product was present at ∼30% of the level observed in the released control cells (Fig. 5 A, lane 3). These data suggest that a fraction of separase is active in mitotic astrin- depleted cells.

Figure 5.

Separase-dependent formation of multipolar spindles and loss of sister chromatid cohesion in cells depleted of astrin. (A) Extracts prepared from nocodazole-arrested HeLa control cells (lane 1), control cells that had been released from a nocodazole block for 100 min (lane 2), or astrin-depleted cells harvested by mitotic shake off (lane 3) were immunoblotted with mouse anti–C-separase antibodies and mouse anti–lamin A as a loading control. The blot shown is a representative example of five independent experiments. (B) HeLa cells were depleted of astrin and separase individually or together. Extracts from these and control cells were blotted for astrin and separase and tubulin as a loading control. Note that astrin-depleted cells (lane 3) contain more separase than asynchronous (lane 1) but similar amounts to nocodazole-arrested control cells (lane 2) because of the elevated mitotic index. (C) Cells treated as in B were stained with antibodies against astrin (red) and α-tubulin (green). Representative images of each cell population are shown. (D–F) Quantitation of the mitotic index, percentage of multipolar cells of mitotic cells, and degree of sister chromatid separation observed in astrin-, separase-, or double-depleted cells and control cells. Error bars represent SD. Bar, 10 μm.

To directly test the involvement of separase in the astrin phenotype, cells were simultaneously depleted of astrin and separase. Immunofluorescence and Western blotting analysis showed that both proteins could be efficiently depleted either singly or together (Fig. 5, B and C). Cells lacking both separase and astrin displayed a similarly elevated mitotic index in comparison with cells depleted only of astrin (15.5 ± 3.7% in the double depletion in comparison with 16.2 ± 3.0% in astrin depletion; Fig. 5 D). However, in contrast to astrin depletion alone, cultures depleted of both astrin and separase contained considerably fewer cells with multipolar spindles (16.9 ± 6.0% in the double depletion vs. 68.8 ± 11.5% in the astrin RNAi; Fig. 5 E). Importantly, chromosome spreads of these cultures showed that sister chromatid cohesion was restored in cells in which both astrin and separase expression had been repressed (Fig. 5 F). In contrast, no effect on the TOGp phenotype was observed upon the additional depletion of separase (Fig. S3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200701163/DC1). Collectively, these data show that both the aberrant centriole disengagement and the premature loss of sister chromatid cohesion observed in astrin-depleted cells involve separase.

The cleavage of sister chromatid cohesion by separase is subject to multiple layers of control, involving regulation of the enzymatic activity of separase by cyclin B1 and securin, which are both targets of the spindle assembly checkpoint. Our present results suggest the existence of additional layers of control. Although it is not immediately obvious how to reconcile premature separase activation in astrin-depleted cells with the persistence of the spindle assembly checkpoint in these cells, our observations clearly indicate that a subpopulation of separase can be activated even though the general mitotic arrest of the cell is maintained. This implies that astrin contributes to the tight regulation of separase activity.

Materials and methods

RNAi

Plasmid transfection and RNAi were performed as described previously (Hanisch et al., 2006a). Sgo1, aurora B, Hec1, TOGp, Ska1, Ska2, CENP-F, and Mad2 siRNA oligonucleotides were described previously (Honda et al., 2003; Holt et al., 2005; McGuinness et al., 2005; Hanisch et al., 2006b). Astrin, separase, and CENP-E were targeted with 5′-TCCCGACAACTCACAGAGAAA-3′, 5′-AAGCTTGTGATGCCATCCTGA-3′, and 5′-ACTCTTACTGCTCTCCAGTTT-3′ (QIAGEN), respectively. For Western blot analysis of whole cell lysate, cells of one 2-cm plate were harvested and lysed in laemmli buffer. For Western blot analysis of mitotic cells, HeLa S3 cells were collected by mitotic shake off and lysed in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 40 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 10 mM NaF, 0.3 mM Na-vanadate, 1 mM EDTA, 1% [vol/vol] IGEPAL, 0.1% [vol/vol] deoxycholate, 2 mM Pefabloc, 100 nM okadaic acid, and protease inhibitor cocktail without EDTA (Roche Diagnostics). For the analysis of separase activity by Western blotting, N-ethylmaleimide (2.5-mM final concentration; Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the lysis buffer.

Antibodies and inhibitors

Astrin aa 1–481 (N-astrin) or astrin aa 1,014–1,193 (C-astrin) were cloned into pQE30 (QIAGEN) or pGEX-5X-1 (GE Healthcare), respectively, and were expressed and purified according to standard protocols. Antibodies against C- and N-astrin were raised in rabbits (Charles River Laboratories) and affinity purified using maltose-binding protein–tagged astrin. Goat polyclonal antibodies against centrin-3 were raised against recombinant full-length His-tagged centrin-3 and were affinity purified using GST-tagged centrin-3. Antibodies against aurora B, CENP-A, CENP-E, CENP-F, BubR1, Bub1, Hec1, Plk1, Mad2, α-tubulin, and myc and CREST serum were described previously (Baumann et al., 2007). Other antibodies used in this study were as follows: rabbit anti–pericentrin B, mouse antisecurin, mouse antiseparase (clone XJ11-1B12), and rabbit antiphosphohistone H3 (Ser10) (Abcam); mouse anti–cyclin B1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.); mouse anti-EB1 (BD Biosciences); mouse anti−γ-tubulin (clone GTU88; Sigma-Aldrich); and mouse anti-Sgo1 (Abnova). Rabbit anti-TOGp antibodies were gifts from X. Yan (Third Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration, Xiamen, China). Secondary antibodies conjugated to HRP, Cy2, Cy3, or Cy5 were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories. DNA was stained with DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich). Aurora B inhibitor ZM447439 was obtained from Tocris Biosciences.

Image acquisition and time-lapse microscopy

Image acquisition was performed as previously described (Hanisch et al., 2006a). The fixation for the K-fiber analysis was performed as described previously (Holt et al., 2005). Cold treatment was performed as described previously (Hanisch et al., 2006a). For high resolution images and for time-lapse microscopy of HeLa-S3 H2B-GFP cells, a high resolution imaging system (Deltavision; Applied Precision) on an inverted microscope (IX71; Olympus) equipped with plan Apo 40× NA 0.95, plan Apo 60× NA 1.4, and 100× NA 1.35 oil immersion objectives (Olympus) and a camera (CoolSnap HQ; Photometrics) was used as described previously (Hanisch et al., 2006a). HeLa–CENP-A–YFP cells were filmed on the same system at intervals of 4 min, imaging seven focal planes 2 μm apart, with an exposure of 0.8 s and 100% neutral density.

Mitotic chromosome spreads

HeLa S3 cells were treated with Gl2 (control), CENP-E, astrin, or Sgo1 siRNA oligonucleotides for 43 or 35 h (Sgo1), and then 100 ng/ml nocodazole was added for a further 5 h. Alternatively, HeLa S3 cells were arrested in G1/S phase with 1.6 μg/ml aphidicolin for 16 h, released for 6 h, and arrested in G2/M phase for 16 h by adding 100 ng/ml nocodazole. Mitotic cells were collected by mitotic shake off, and chromosome spreads were prepared as described previously (Hanisch et al., 2006b).

Online supplemental material

Videos 1 and 2 show a control and an astrin-depleted cell progressing through mitosis (Fig. 1 E). Fig. S1 shows that the depletion of astrin induces the formation of multipolar spindles. Fig. S2 shows that the absence of astrin causes the loss of sister chromatid cohesion. Fig. S3 shows that the formation of multipolar spindles in TOGp-depleted cells is not dependent on separase. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200701163/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Drs. H.H. Sillje, D.W. Cleveland, T. Yen, S.S. Taylor, O. Stemmann, X. Yan, and J.M. Peters for reagents. We also thank Drs. F.A. Barr, O. Stemmann, and J.M. Peters for helpful suggestions and critical reading of the manuscript and all members of the Nigg laboratory for advice.

This work was supported by the Max Planck Society, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant SFB 646), and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie. U. Gruneberg is supported by a Cancer Research UK Career Development Fellowship.

U. Gruneberg's present address is University of Liverpool Cancer Research Centre, Liverpool L3 9TA, UK.

Abbreviations used in this paper: CENP, centromere protein; Plk1, Pololike kinase 1; TOGp, tumor overexpressed gene protein.

References

- Baumann, C., R. Korner, K. Hofmann, and E.A. Nigg. 2007. PICH, a centromere-associated SNF2 family ATPase, is regulated by Plk1 and required for the spindle checkpoint. Cell. 128:101–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassimeris, L., and J. Morabito. 2004. TOGp, the human homolog of XMAP215/Dis1, is required for centrosome integrity, spindle pole organization, and bipolar spindle assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15:1580–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, G.K., B.T. Schaar, and T.J. Yen. 1998. Characterization of the kinetochore binding domain of CENP-E reveals interactions with the kinetochore proteins CENP-F and hBUBR1. J. Cell Biol. 143:49–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M.S., C.J. Huang, M.L. Chen, S.T. Chen, C.C. Fan, J.M. Chu, W.C. Lin, and Y.C. Yang. 2001. Cloning and characterization of hMAP126, a new member of mitotic spindle-associated proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 287:116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciosk, R., W. Zachariae, C. Michaelis, A. Shevchenko, M. Mann, and K. Nasmyth. 1998. An ESP1/PDS1 complex regulates loss of sister chromatid cohesion at the metaphase to anaphase transition in yeast. Cell. 93:1067–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca, J.G., B. Moree, J.M. Hickey, J.V. Kilmartin, and E.D. Salmon. 2002. hNuf2 inhibition blocks stable kinetochore-microtubule attachment and induces mitotic cell death in HeLa cells. J. Cell Biol. 159:549–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergely, F., V.M. Draviam, and J.W. Raff. 2003. The ch-TOG/XMAP215 protein is essential for spindle pole organization in human somatic cells. Genes Dev. 17:336–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorr, I.H., D. Boos, and O. Stemmann. 2005. Mutual inhibition of separase and Cdk1 by two-step complex formation. Mol. Cell. 19:135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, J., J. Harborth, J. Schnabel, K. Weber, and M. Hatzfeld. 2002. The mitotic-spindle-associated protein astrin is essential for progression through mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 115:4053–4059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch, A., H.H. Sillje, and E.A. Nigg. 2006. a. Timely anaphase onset requires a novel spindle and kinetochore complex comprising Ska1 and Ska2. EMBO J. 25:5504–5515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch, A., A. Wehner, E.A. Nigg, and H.H. Sillje. 2006. b. Different Plk1 functions show distinct dependencies on Polo-Box domain-mediated targeting. Mol. Biol. Cell. 17:448–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland, A.J., and S.S. Taylor. 2006. Cyclin-B1-mediated inhibition of excess separase is required for timely chromosome disjunction. J. Cell Sci. 119:3325–3336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmfeldt, P., S. Stenmark, and M. Gullberg. 2004. Differential functional interplay of TOGp/XMAP215 and the KinI kinesin MCAK during interphase and mitosis. EMBO J. 23:627–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, S.V., M.A. Vergnolle, D. Hussein, M.J. Wozniak, V.J. Allan, and S.S. Taylor. 2005. Silencing Cenp-F weakens centromeric cohesion, prevents chromosome alignment and activates the spindle checkpoint. J. Cell Sci. 118:4889–4900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda, R., R. Korner, and E.A. Nigg. 2003. Exploring the functional interactions between Aurora B, INCENP, and survivin in mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:3325–3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hut, H.M., W. Lemstra, E.H. Blaauw, G.W. Van Cappellen, H.H. Kampinga, and O.C. Sibon. 2003. Centrosomes split in the presence of impaired DNA integrity during mitosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:1993–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keryer, G., H. Ris, and G.G. Borisy. 1984. Centriole distribution during tripolar mitosis in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Cell Biol. 98:2222–2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack, G.J., and D.A. Compton. 2001. Analysis of mitotic microtubule-associated proteins using mass spectrometry identifies astrin, a spindle-associated protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:14434–14439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness, B.E., T. Hirota, N.R. Kudo, J.M. Peters, and K. Nasmyth. 2005. Shugoshin prevents dissociation of cohesin from centromeres during mitosis in vertebrate cells. PLoS Biol. 3:e86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio, A., and K.G. Hardwick. 2002. The spindle checkpoint: structural insights into dynamic signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:731–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti, A., M. Moudjou, M. Paintrand, J.L. Salisbury, and M. Bornens. 1996. Most of centrin in animal cells is not centrosome-associated and centrosomal centrin is confined to the distal lumen of centrioles. J. Cell Sci. 109:3089–3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieder, C.L. 1981. The structure of the cold-stable kinetochore fiber in metaphase PtK1 cells. Chromosoma. 84:145–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sluder, G., and C.L. Rieder. 1985. Centriole number and the reproductive capacity of spindle poles. J. Cell Biol. 100:887–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanudji, M., J. Shoemaker, L. L'Italien, L. Russell, G. Chin, and X.M. Schebye. 2004. Gene silencing of CENP-E by small interfering RNA in HeLa cells leads to missegregation of chromosomes after a mitotic delay. Mol. Biol. Cell. 15:3771–3781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsou, M.F., and T. Stearns. 2006. Mechanism limiting centrosome duplication to once per cell cycle. Nature. 442:947–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlmann, F., D. Wernic, M.A. Poupart, E.V. Koonin, and K. Nasmyth. 2000. Cleavage of cohesin by the CD clan protease separin triggers anaphase in yeast. Cell. 103:375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waizenegger, I.C., S. Hauf, A. Meinke, and J.M. Peters. 2000. Two distinct pathways remove mammalian cohesin from chromosome arms in prophase and from centromeres in anaphase. Cell. 103:399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waizenegger, I., J.F. Gimenez-Abian, D. Wernic, and J.M. Peters. 2002. Regulation of human separase by securin binding and autocleavage. Curr. Biol. 12:1368–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen, T.J., G. Li, B.T. Schaar, I. Szilak, and D.W. Cleveland. 1992. CENP-E is a putative kinetochore motor that accumulates just before mitosis. Nature. 359:536–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.