Abstract

This paper aims to draw attention to the common oral and dental diseases and conditions in childhood in the context of aetiological factors and to highlight how many of the risk factors for oral and dental ill health are common to other areas of chronic diseases among this age group: diet, hygiene, trauma, stress, and in older children and adolescents, smoking, alcohol use, and use of illegal substances. Suggestions as to how to address these common risk factors are proposed.

Keywords: oral health, disadvantage, obesity

Oral ill health, whether it is due to dental caries (decay), tooth erosion, or gum disease, imposes a significant burden not only on the individual but also on the economy. In the USA, data from the National Health Interview Survey indicated that there were 2.9 million acute dental episodes in 1994, accounting for 3.9 million days lost from work in the over 18 age group and 1.2 million days of missed school for the 5–17 year age group.1 In addition, the survey identified that children from poor families suffered 12 times more restricted days activities as a consequence of dental disease than did children from higher income families. Among the low income families, 50% of the dental caries remained untreated.

In Ireland, the non‐capital cost of the primary dental services is in the region of €127 million, of which in excess of €100 million is spent on treating dental caries.

The treatment of this disease has other consequences; in young children, treatment of dental caries may require extraction of teeth under general anaesthesia (GA), a procedure not without risk in that, on average, two healthy children a year die under a dental GA. Bad dental experiences in childhood are cited as a cause of dental anxiety or phobias in adults of whom up to 39% can recall vivid dental episodes, experienced before they were 10 years of age.2

Oral health has been measured in national surveys, of Irish children since 1952, in the UK since 1973, and more recently internationally through the World Health Organisation.3 Baseline data on dental caries collected prior to the fluoridation of domestic water supplies in Ireland in 1964 showed that 12 year olds had over five permanent teeth affected by dental disease, although this had declined to an average of one decayed permanent tooth by 1997.4 Preliminary data from the 2001 national oral health survey of children in Ireland indicate that these improvements have been maintained in older children but that decay experience is actually increasing in 5 year old children.5 A similar pattern is observed in the UK where decennial surveys have shown initially a decline in caries experience in the 1980s but an increase caries experience in 5 year olds in the 1990s. In the most recent UK survey of children's oral health carried out in 2003, 8 year olds as well as 5 year olds are showing an increased prevalence of dental decay.6

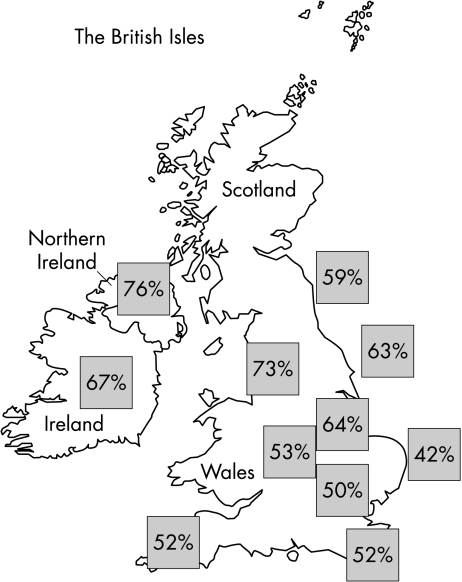

Fluoridation of water supplies to over 70% of households in the Republic of Ireland has undoubtedly had an impact on dental disease experience. By comparison with their peers in non‐fluoridated Northern Ireland, children in the South have less dental decay. However, it can be seen that among 15 year olds (fig 1), caries experience across the British Isles maps more to deprivation than to fluoridation status; it is predominantly the south of Ireland, the West Midlands, and parts of the northeast of England that have artificial water fluoridation schemes. Experience shows, in New Zealand as well, that while lifelong exposure to water fluoridation reduces socioeconomic gradients, it does not eliminate them.7,8 That notwithstanding, close inspection of the data on dental decay does show unequivocal advantages for oral health from the fluoridation of public water supplies, and should be implemented, especially in urban areas where dental decay levels are unacceptably high.9

Figure 1 Proportion of 15 year old children with decay experience (decayed, missing due to decay, or filled, permanent teeth) in the countries of the British Isles in 2002–03.

Nationwide fluoridation of water supplies in Ireland in the 1960s was a policy decision taken to support a small dental workforce, unable to cope with the epidemic of dental disease. Other countries responded to a dental manpower shortage by, for example, utilising dental auxiliaries to provide cost effective public dental care for children.10,11 It is recognised that children from low income families are more likely to have dental disease and also more likely to access care, when they do, through the publicly funded service.12 In the United States too, where children from low income families experience not only more dental disease but also more extensive disease they make greater use of publicly funded pain relief services.13 Disadvantaged children are more likely to be the ones who have teeth extracted rather than filled.14 This could become the norm in the UK, given that access to dental care by vulnerable groups of children may well be restricted by the developments in personal dental service arrangements in individual primary care trusts. Added to the lack of development of specialist services for children in primary dental care, together will impose further disadvantage.15

Dental disease is inextricably linked with deprivation. In the most recent all‐Ireland survey of children's oral health, deprived children, using possession of a medical card in the south and low income benefit in the north as proxies for disadvantage, had more decay than did children from more affluent families. However, medical card/low income benefit status are crude measures of deprivation and there is a need perhaps for a more refined measure of social inequality, as indicated by Thomson and Mackay,8 who recommend a combination of area and household based socioeconomic status measures to inform policy decisions for the better targeting of at‐risk children.

While dental decay remains a public health problem, despite the fact that it is totally preventable, loss of dental hard tissues by acid erosion is assuming increasing importance. Data from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey of 1½–4½ year olds in the UK16 have shown that the prevalence of dental erosion is high in this age group and that following through a cohort of children from the UK national survey of children's oral health of 5–15 year olds, indicates that tooth erosion may be increasing in children.17 Likewise, gum disease and poor oral hygiene are more prevalent in young people now than they were 10 years ago.6 Although fluoride in toothpaste has had a significant impact on dental caries prevalence, tooth brushing per se seems, from these data at least, to be less effectively employed in removing plaque and preventing gum disease. Data from a number of countries have shown that starting to brush before a year old, twice a day, and with parental involvement, doubles the odds of being decay free, irrespective of the level of disadvantage. Further research is needed to evaluate the outcomes of developing parenting skills to reduce dental caries in children from disadvantaged communities.18

Poor diet, specifically frequent consumption of sweet foods and drinks, is the main cause of dental decay and tooth erosion. Evidence for this relationship has been documented most recently in the oral health surveys conducted as part of the National Diet and Nutrition Surveys of both 1½–4½ year olds and 4–18 year olds.16,19 Data from the ALSPAC study in the UK have shown that parents do not follow weaning guidelines, so that children develop nutritional deficiencies, obesity, and dental disease.20,21 There is an inverse relationship between breast feeding and consumption of sweetened drinks.22 The use of sweetened drinks rather than milk occurs earlier in infants from low income families.23 Parents from disadvantaged families have a poor understanding of the effects of constant exposure of teeth from sugared drinks in feeding bottles. There is a perception that giving water as an alternative to milk or sweetened drinks is cruel and is rejected by children. Milk is viewed as a food rather than a drink and water in a feeding bottle is seen as a sign, by parents, of poverty.24

An increase in soft drink consumption is inversely related to milk consumption and thus a decrease in calcium intake, which in turn has an inverse relationship with body mass index.25 Obesity is the most common nutritional disease in many parts of the western world and, like dental caries, is more likely to affect children who are disadvantaged.26

Like the parallels with obesity, oral health in childhood is a predictor for adult oral health, and while there is a direct relationship with low socioeconomic status and childhood decay prevalence, the oral health effects are not reversed with upward social mobility into adolescence and beyond.27,28 It is agreed that markers of disadvantage—poverty, underachievement in education, lone parenting, oral disease—are increasing in many societies and posing a significant risk for morbidity in adult life.29 Addressing these root causes will impact more significantly on the lives of children, and eventually adults, than will merely treating the disease in those that present for care.

Individual oral/dental health education programmes, targeted as they are on attempting to change behaviours in isolation from the very significant influence of the socio‐political context in which people exist, are doomed to failure.30 Acknowledgement of the risks common to all chronic diseases and conditions outlined above, dental included, means that all healthcare workers need to engage inter‐professionally in tackling the determinants of ill health.

While clinicians are becoming more aware of their respective roles in what have traditionally been seen as the preserve of other disciplines, for example, dentists working on the risk of low birth weight, smoking, and periodontal disease in mothers,31 as well as paediatricians and health visitors taking a role in oral health promotion,32,33 it is acknowledged that training is a fundamental issue in ensuring that healthcare workers have the confidence and competence to become involved in such health promoting activities, especially among disadvantaged children.33,34,35

In the short term, a way forward would be:

To incorporate this common risk factor approach into all health students' teaching, ideally as part of a core course to all healthcare workers so that key messages are consistent.

To incorporate cross‐referrals where appropriate into care plans, consistent with the patient‐centred approach, reflective of the common risk approach and not disease specific. For example, health visitors would work with oral healthcare teams in alerting them to high risk families—where poor nutrition, compliance, and risk taking predisposed such children to diseases—oral, dental, and others. Likewise, oral health teams would need to work more closely with dieticians and other members of primary care teams.

The development of evidence based clinical guidelines to incorporate consideration of common risk factors. The Scottish Intercollegiate Network's two guidelines on dental caries and obesity that have been adopted by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health are a good example (http://www.rcpch.ac.uk/publications/clinical_docs.html).

To promote joint working between professional bodies to monitor educational input and utilise communication channels to healthcare workers, for example websites, journals, and newsletters. Much work goes on within the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health in liaison groups; the one with the British Society of Paediatric Dentistry, among its other activities, has produced guidance particularly for the trainee paediatrician in diagnosing and managing common oral and dental problems of childhood through the PIER website and through the BACCH newsletter.

Longer term investment has to be made in the wider issues of education, housing, and other aspects of the environment that impact on health and compound disadvantage—for generations. In a recent Perspective in this journal, Weaver36 commented that, “Paediatricians must not regard their calling as too holy or pure a vocation and forget that child health is the basis for adult health. They have not led the way to re‐establishing this vital connection”. All those with an interest in future generations must engage together in this process.

Footnotes

Competing interests: none

References

- 1.Satcher D S. Surgeon General's Report on Oral Health. Public Health Rep 2000115489–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health National Adult Oral Health Survey 1998. London: The Stationery Office, 2002

- 3.Petersen P E. Socio‐behavioural risk factors in dental caries—international perspectives. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 200533274–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Children Forum on fluoridation. ISBN 0755 711 572. www.fluoridationforum.ie 2002

- 5.Department of Health and Children Children's oral health in Ireland 2002. Preliminary results. 2003.

- 6.Office for National Statistics Children's dental health in the United Kingdom 2003. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/STATBASE/Product.asp?vlnk = 12918Office for National Statistics

- 7.Bradnock G, Marchment M D, Anderson R J. Social background, fluoridation and caries experience in a 5‐year‐old population in the West Midlands. Br Dent J 1984156127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomson W M, Mackay T D. Child dental caries patterns described using a combination of area‐based and household‐based socio‐economic status measures. Community Dent Health 200421285–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Downer M C, Drugan C S, Blinkhorn A S. Dental caries experience of British children in an international context. Community Dent Health 20052286–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newton J T, Buck D, Gibbons D E. Workforce planning in dentistry: the impact of shorter and more varied career patterns. Community Dent Health 200118236–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris R, Burnside G. The role of dental therapists working in four personal dental service pilots: type of patients seen, work undertaken and cost‐effectiveness within the context of the dental practice. Br Dent J 2004197491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dugmore C, Nunn J H. Does the community dental service provide primary dental care for disadvantaged children? Prim Dent Care 2004119–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelstein B L. Disparities in oral health and access to care: findings of national surveys. Ambul Pediatr 20022(2 suppl)141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tickle M, Milsom K, Blinkhorn A. Inequalities in the dental treatment provided for children: an example from the UK. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 200230335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nunn J H, Crawford P J, Page J.et al The dental needs of children. Int J Paediatr Dent 19977203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hinds K, Gregory J.National Diet and Nutrition Survey: children aged 1½–4½‐years. Volume 2; report of the dental survey. London: HMSO, 1995

- 17.Nunn J H, Gordon P H, Morris A J.et al Dental erosion—changing prevalence? A review of British National children's surveys. Int J Paediatr Dent 20031398–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pine C M, Adair P M, Nicoll A D.et al International comparisons of health inequalities in childhood dental caries. Community Dent Health 200421(suppl)121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker A, Gregory J, Bradnock G.et alNational Diet and Nutrition Survey: young people 4 to 18 years. Volume 2: Report of the Oral Health Survey. London: TSO, 2000

- 20.Northstone K, Rogers L, Emmett P.et al Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood. Eur J Clin Nutr 200256236–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karp W B. Childhood and adolescent obesity: a national epidemic. J Calif Dent Assoc 199826771–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lande B, Anderson L F, Veierod M B.et al Breastfeeding at 12 months of age and dietary habits among breast‐fed and non‐breast‐fed infants. Public Health Nutr 20047495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohan A, Morse D, O'Sullivan D M.et al The relationship between bottle usage/content, age and number of teeth with mutans streptococci colonization in 6–24‐month‐old children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 19982612–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chestnutt I G, Murdoch C, Robson K F. Parents and carers' choice of drinks for infants and toddlers in areas of social disadvantage. Community Dent Health 200320139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bray G A. The epidemic of obesity and changes in food intake: the fluoride hypothesis. Physiol Behav 200482115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer C A. Dental caries and obesity in children: different problems, related causes. Quintessenz Int 200536457–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomson W M, Williams S M, Dennison P J.et al Were NZ's structural changes to the welfare state in the early 1990s associated with a measurable increase in oral health inequalities in children? Aust N Z J Public Health 200226525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poulton R, Caspi A, Milne B J.et al Association between children's experience of socio‐economic disadvantage and adult health: a life course study. Lancet 20023601619–1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Platt M J, Pharoah P O. Child health statistical review, 1996. Arch Dis Child 199675527–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheiham A, Watt R G. The common risk factor approach: a rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 200028399–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boutigny H, Boschin F, Delcourt‐debruyne E. Periodontal diseases, tobacco and pregnancy. J gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 20053474–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinn G, Freeman R. Dental Health. 2. Working together in dental health education. Health Visit 19946790–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de la Cruz G G, Rozier R G, Slade G. Dental screening and referral of young children by pediatric primary care providers. Pediatrics 2004114642–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunter M L, Hunter B, Chadwick B. The current status of dental health education in the training of midwives and health visitors. Community Dent Health 19961344–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis C W, Grossman D C, Domoto P K.et al The role of the paediatrician in the oral health of children: a national survey. Pediatrics 200010684–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weaver L T. Academic paediatrics. Arch Dis Child 200590991–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]