Abstract

Aims

To assess the relation between fatigue and somatic symptoms in healthy adolescents and adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalopathy (CFS/ME).

Methods

Seventy two adolescents with CFS were compared within a cross‐sectional study design with 167 healthy controls. Fatigue and somatic complaints were measured using self‐report questionnaires, respectively the subscale subjective fatigue of the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS‐20) and the Children's Somatization Inventory.

Results

Healthy adolescents reported the same somatic symptoms as adolescents with CFS/ME, but with a lower score of severity. The top 10 somatic complaints were the same: low energy, headache, heaviness in arms/legs, dizziness, sore muscles, hot/cold spells, weakness in body parts, pain in joints, nausea/upset stomach, back pain. There was a clear positive relation between log somatic symptoms and fatigue (linear regression coefficient: 0.041 points log somatic complaints per score point fatigue, 95% CI 0.033 to 0.049) which did not depend on disease status.

Conclusions

Results suggest a continuum with a gradual transition from fatigue with associated symptoms in healthy adolescents to the symptom complex of CFS/ME.

Keywords: chronic fatigue syndrome, fatigue, somatic complaints, adolescence, healthy

Whether chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalopathy (CFS/ME) is a distinct illness with its own causal processes is still a central question in research and clinical practice. The symptom complex is characterised by persistent debilitating fatigue causing a marked reduction of school and social activity. The minimal illness duration to fulfil criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is 6 months.1 Recently developed clinical guidelines in the UK, however, concluded that the diagnosis should be based primarily on the impact of the condition and not require a specific illness duration.2 Adolescents who suffer from CFS/ME additionally report a variety of physical complaints such as headache, memory and concentration impairments, and muscle and joint pain.2 The symptom complex is not unique for CFS/ME but overlaps with syndromes such as fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome, equally ill defined in terms of pathophysiology.3,4

This raises the question of how fatigue is related to other somatic symptoms in adolescents with CFS/ME. Fatigue is not only a symptom of illness but also a common phenomenon in healthy adolescents. A recent prevalence study in the USA established that 21% of healthy adolescents experience fatigue.5 Other somatic symptoms, like headache, stomach ache, back ache, and dizziness, also occur in healthy adolescents, as recently published in a WHO report on European countries.6,7

We hypothesised that fatigue is proportionally related to other somatic symptoms, not only in adolescents with CFS/ME but in healthy adolescents as well. Secondly, we hypothesised that CFS/ME is positioned at the end of a continuous scale that includes the symptoms of healthy adolescents.

Methods

A total of 132 adolescents (12–18 years of age) with severe fatigue were referred to a specific CFS/ME clinic of the Department of General Paediatrics of the University Medical Center Utrecht between January 2001 and May 2004. All patients were Caucasian and 83 adolescents fulfilled the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria for CFS/ME.1 A child psychologist performed psychological examinations, using specific Dutch questionnaires for anxiety and depression in combination with an interview of both child and parent. Additional to the CDC exclusion criteria, patients with life long problems of somatisation (n = 2) or an established diagnosis of a severe depression or a primary anxiety disorder dependent on pharmaceutical treatment (n = 3) or severe somatic co‐morbidity (n = 1) were excluded. Five adolescents refused to participate (2 on account of fatigue, 1 received no permission from the rehabilitation centre, 2 gave no reason). Individual measurements took place from 2002 to 2004 in separate rooms in the hospital. Of the remaining 72 adolescents, 66 fulfilled all CDC criteria for CFS/ME at the moment of the research examinations: 6 months' duration, debilitating fatigue particularly affecting school attendance, and a minimum of four side symptoms. Six patients had less than four side symptoms, but were still included.

As a reference group, 363 adolescents aged 12–18 years from a general secondary school, De Breul in the Dutch City of Zeist, were invited to participate. Inclusion criteria were age (12–18 years) and no current illness. A total of 167 adolescents (46%) agreed to participate and were examined during sessions at school in April 2002. All subjects were Caucasian.

Fatigue was measured with the subscale subjective fatigue of the self‐report questionnaire Checklist Individual Strength‐20 (CIS‐20) consisting of eight items about fatigue in the two weeks preceding the assessment, using a Likert scale (range: 1–7). The questionnaire has good reliability and discriminative validity.8

Somatic complaints were assessed with a validated Dutch translation of the Children's Somatization Inventory (CSI),9,10 a self‐report questionnaire, rating the presence of 35 somatic symptoms in the last two weeks using a five point Likert scale ranging from not at all (0) to a whole lot (4). This questionnaire was originally developed to measure somatisation and includes many functional somatic symptoms and most symptoms mentioned in the CDC criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome,1 except for the symptoms tender lymph nodes, unrefreshing sleep, and post‐exertion malaise. Two items from the CSI were omitted in the analysis: “weakness in body parts” and “low energy” because of overlap with the subscale subjective fatigue. We calculated the number of reported somatic symptoms irrespective of the severity (range 0–33). A total score, representing both number and severity of symptoms, was obtained by summing the ratings (range 0–132 (33×4)). This total somatic symptom score was judged as the best indicator of the burden of somatic symptoms, and was used in the analysis.

The medical ethics committee of the University Medical Center Utrecht approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from both adolescents and parents.

Analysis

Of the relevant variables, group specific means and standard deviations were calculated for descriptive purposes.

The data were analysed with linear regression using the variable of interest as dependent variable and a group indicator (patient = 1, control = 0) as independent variable to explore group differences. Results are presented as linear regression coefficients representing mean differences between CFS/ME adolescents and healthy controls for the investigated parameter with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The same models were used to adjust for age and gender.

Mean Likert scores for each somatic complaint were calculated and reported as a top 10 of somatic complaints.

To analyse the relation between fatigue and somatic complaints we performed a linear regression model with the somatic symptom score as the dependent variable and the fatigue score as an independent variable with adjustment for age and gender in the same model. The somatic symptom score was log transformed because its variance was not constant along different levels of the fatigue score. We tested for an interaction between CFS/ME and fatigue scores by adding an interaction term in the regression model (interaction is calculated as the product of CFS/ME status (yes or no) and fatigue scores).

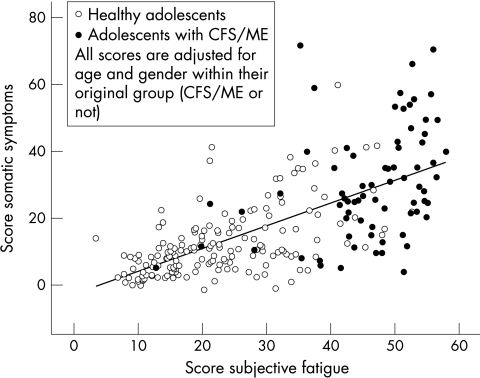

For a graphical depiction of the results (fig 1), we calculated for each participant adjusted fatigue score and adjusted somatic symptom score, to account for the slight difference in age and gender between the healthy adolescents and those with CFS/ME. All these individual scores were adjusted for age and gender within their original group (CFS/ME or not).

Figure 1 Relation between fatigue score and somatic complaints score for each individual. Each higher score point of fatigue resulted, on average, in a 0.57 higher score point of somatic complaints.

The analyses were performed with the use of SPSS 12.0.1 statistical package for Windows.

Results

A total of 72 patients (82% girls) and 167 controls (60% girls) were included. As shown in table 1, the score for both fatigue and somatic complaints, adjusted for the covariates age and gender, were significantly higher for the adolescents with CFS/ME. The top 10 of somatic symptoms in the CFS/ME adolescents was identical to the top 10 of somatic symptoms in healthy adolescents, except for “sore muscles” in the top 10 of the CFS/ME adolescents, which was substituted for “stomach pain” in the top 10 of the healthy adolescents.

Table 1 Characteristics and scores of CFS/ME adolescents and healthy controls.

| 72 CFS/ME cases | 167 healthy controls | Mean difference (95% CI) | Adjusted mean difference* (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 16.0 (1.6) | 15.5 (1.6) | 0.5 (0.08; 0.97) | |

| Gender (% girls) | 82 | 60 | 22 (10; 34) | |

| Fatigue assessment | ||||

| Subscale Subjective Fatigue (CIS‐20) (8 items; 7 point Likert Scale; 1–7; range 8–56) | 46.1 (9.2) | 22.9 (11.0) | 23.2 (20.3; 26.1) | 21.6 (18.7; 24.5) |

| CDC criteria (range 0–8) | ||||

| Number of reported CDC minor symptoms | 5.7 (1.7) | Not specified | ||

| Children's Somatization Inventory | ||||

| (33 items, 5 point Likert Scale 0–4) | ||||

| Total score (range 0–132) | 30.2 (17.7) | 12.4 (10.5) | 17.8 (14.1; 21.4) | 16.2 (12.6; 19.9) |

| Number of symptoms (range 0–33) | 14.1 (6.0) | 7.7 (5.0) | 6.3 (4.8; 7.8) | 5.8 (4.3; 7.3) |

| Top 10 somatic complaints (range 0–4) | ||||

| 1. Low energy | 2.7 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.1) | ||

| 2. Headache | 2.1 (1.4) | 1.1 (1.1) | ||

| 3. Heaviness in arms/legs | 1.9 (1.3) | 0.4 (0.8) | ||

| 4. Dizziness | 1.9 (1.5) | 0.8 (1.0) | ||

| 5. Sore muscles | 1.9 (1.4) | 0.8 (0.9) | ||

| 6. Hot/cold spells | 1.7 (1.3) | 0.6 (1.0) | ||

| 7. Weakness in body parts | 1.7 (1.3) | 0.7 (1.1) | ||

| 8. Pain in joints | 1.7 (1.4) | 0.6 (1.0) | ||

| 9. Nausea/upset stomach | 1.6 (1.4) | 0.8 (1.0) | ||

| 10. Back pain | 1.5 (1.3) | 0.9 (1.2) |

*Adjusted for age and gender.

Values are mean (SD).

95% CI = 95% confidence interval corresponding with p<0.05.

What is already known on this topic

The symptom complex of adolescents with CFS/ME includes other somatic symptoms and overlaps with functional somatic syndromes such as fibromyalgia or irritable bowel syndrome

What this study adds

The hierarchy of self‐reported complaints is similar in healthy and CFS/ME adolescents. In both groups, an increase of fatigue was found to be positively related to the experience of other somatic symptoms

Results suggest a continuum with a gradual transition from fatigue with associated symptoms in healthy adolescents to the symptom complex of CFS/ME

Fatigue and somatic complaints were positively related, with a linear regression coefficient of 0.041 points log somatic complaints per score point fatigue (95% CI 0.033 to 0.049, p < 0.001) without a significant effect of interaction between fatigue score and CFS/ME (p = 0.847).

Eleven of the healthy adolescents showed a fatigue score ⩾40, corresponding to the fatigue score for adolescents with CFS/ME. Their fatigue, however, did not result in severe disability: eight showed no school absence in the past 6 months, and only three had considerable school absence (5–50%)—one because of multiple injuries, one because of an infectious illness, and one without reason.

Discussion

Healthy and CFS/ME adolescents share a symptom complex, of which fatigue is the main symptom as low energy ranks first in the top 10 of symptoms in both groups. Additionally, a graded positive relationship between fatigue and other somatic complaints is established without a significant effect of interaction between CFS/ME and fatigue. This might imply that the aetiology of experience of fatigue and other somatic symptoms is similar in healthy adolescents and in those with CFS/ME. Our findings suggest a continuum with a gradual transition from fatigue with associated symptoms in healthy adolescents to the symptom complex of CFS/ME.

Only 46% of the healthy adolescents invited to participate agreed, which may raise the question of whether this subgroup is sufficiently representative of the healthy adolescents. It is, however, unlikely that invitees reacted on the basis of specific associations between fatigue and somatic symptoms, in other words that the association between fatigue and somatic symptoms should be different among responders and non‐responders.

Some healthy adolescents experience similar fatigue and associated symptoms as the adolescents with CFS/ME but lack the effect on school attendance and do not view themselves as patients. This may reflect the fact that the identification of a symptom complex as abnormal and requiring medical examination is known to be related to the patient's health beliefs, former experiences, medical knowledge, and norms and values in the family.11,12,13,14,15,16 This emphasises the need for a multidimensional approach with the identification of relevant illness beliefs and the medical and family history.

Biological formulations of the aetiology of these unexplained physical symptoms are scarce. Terminology is therefore predominantly descriptive in terms of symptoms. In general medicine, CFS/ME is categorised as one of the functional somatic syndromes, which is a non‐stigmatising and accepted description for adult patients.17 An overall aetiological concept is still lacking. The findings of our study support the idea that a possible substrate for the experienced symptoms in CFS/ME could be found in a mechanism which is present in all members of the population. A promising concept in this respect is interoception: “the sense of the physiological condition of the body”.18

The recent guidelines of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health do not propose to apply a time criterion for the clinical diagnosis of CFS/ME as opposed to the CDC and Oxford criteria.1,19 The degree of impairment as a consequence of the physical symptoms, is more critical to the diagnosis and treatment than the duration of symptoms. Positive recognition of the symptom complex may facilitate the process of making a diagnosis of CFS/ME and may diminish the need for extensive investigations to exclude other diagnoses. The findings of our study support this positive recognition by viewing fatigue in combination with other somatic symptoms and not only in combination with the minor CDC criteria.

Acknowledgements

We thank the adolescents with CFS/ME and the children of the secondary school De Breul in Zeist for their willingness to participate in this study

Abbreviations

CDC - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CFS - chronic fatigue syndrome

CIS‐20 - Children's Somatization Inventory

ME - myalgic encephalopathy

Footnotes

Competing interests: none declared

References

- 1.Fukuda K, Straus S E, Hickie I.et al The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1994121953–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Evidence based guideline for the management of CFS/ME (chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalopathy) in children and young people. London: RCPCH, 2004

- 3.Nimnuan C, Rabe‐Hesketh S, Wessely S.et al How many functional somatic syndromes? J Psychosom Res 200151549–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wessely S, Nimnuan C, Sharpe M. Functional somatic syndromes: one or many? Lancet 1999354936–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhee H, Miles M S, Halpern C T.et al Prevalence of recurrent physical symptoms in U.S. adolescents. Pediatr Nurs 200531314–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viner R, Christie D. Fatigue and somatic symptoms. BMJ 20053301012–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO Health policy for children and adolescents. No. 4. 1‐248. WHO 2002

- 8.Vercoulen J H, Swanink C M, Fennis J F.et al Dimensional assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res 199438383–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker L S, Garber J, Greene J W. Somatization symptoms in pediatric abdominal pain patients: relation to chronicity of abdominal pain and parent somatization. J Abnorm Child Psychol 199119379–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meesters C, Muris P, Ghys A.et al The Children's Somatization Inventory: further evidence for its reliability and validity in a pediatric and a community sample of Dutch children and adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol 200328413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katon W, Sullivan M, Walker E. Medical symptoms without identified pathology: relationship to psychiatric disorders, childhood and adult trauma, and personality traits. Ann Intern Med 2001134917–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campo J V, Fritsch S L. Somatization in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994331223–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crushell E, Rowland M, Doherty M.et al Importance of parental conceptual model of illness in severe recurrent abdominal pain. Pediatrics 20031121368–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schor E L. Family pediatrics: report of the Task Force on the Family. Pediatrics 20031111541–1571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogden J. What do symptoms mean? BMJ 2003327409–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van de Putte E M, Engelbert R H, Kuis W.et al Chronic fatigue syndrome and health control in adolescents and parents. Arch Dis Child 2005901020–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stone J, Wojcik W, Durrance D.et al What should we say to patients with symptoms unexplained by disease? The “number needed to offend”. BMJ 20023251449–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Craig A D. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body, Nat Rev Neurosci 20023655–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharpe M C, Archard L C, Banatvala J E.et al A report—chronic fatigue syndrome: guidelines for research. J R Soc Med 199184118–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]