Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study was to assess the clinical significance and prognosis of a prolonged isolated elevation of serum aminotransferases without cholestasis (>3 months) in infants and young children, investigated for a variety of conditions, and to determine a protocol for their follow‐up and investigation.

Methods

A combined prospective‐retrospective analysis of apparently healthy babies and young children with isolated elevation of serum aminotransferases of at least 1.5 times above the norm for age which persisted for at least 3 months and whose creatine phosphokinase (CK), gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels remained normal throughout the study duration. The children underwent the following investigations: abdominal ultrasound and infectious, metabolic and/or immunological investigation depending on the duration of the abnormality.

Results

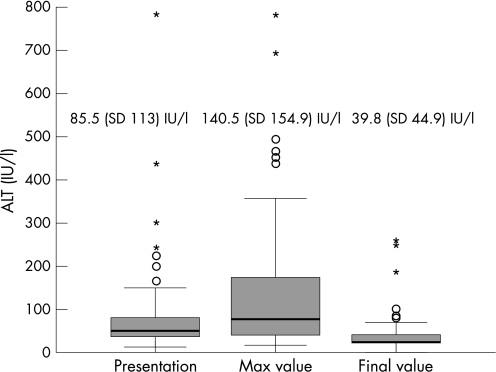

Six children were eliminated following the finding of positive cytomegalovirus (CMV) antigen in the urine. 72 children were investigated (47 males and 25 females). The duration of serum aminotransferases elevation was 3–36 months (average 12.4, median 11.5 months). The initial, maximal and final alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values were 85.5, 140.5 and 39.8 IU/l, respectively. Of seven children who had liver biopsies performed, three (42.8%) were suspected of having a glycogen storage disease which was not confirmed enzymatically. Four biopsies revealed non‐specific histological changes.

Conclusions

Isolated elevation of serum aminotransferases in healthy looking young children is mostly a benign condition that usually resolves within a year. If no pathology is found during routine investigation, these children can be followed conservatively. Liver biopsy does not contribute much to the diagnosis and is probably unnecessary.

There is a plethora of literature on the investigation of the infant or child with cholestasis.1,2,3,4 In the adult literature much attention is devoted to evaluation of the asymptomatic patient with abnormal liver enzymes.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 On the other hand, there are few if any studies on the investigation and prognosis of the asymptomatic infant or child with isolated elevation of serum aminotransferases. In most cases increased enzyme levels resolve within a few weeks and need no further evaluation. However, some of these apparently healthy subjects continue to exhibit high enzyme levels for several months.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess the clinical significance and prognosis of isolated elevation of serum aminotransferases without cholestasis (>3 months) in infants and young children, and to establish a protocol for their investigation and follow‐up.

Methods

We conducted a combined retrospective‐prospective analysis of apparently healthy infants and young children without pathology on physical examination and elevated serum aminotransferases (both alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST)), at least 1.5 times above the norm for age, for 3 months or longer. The studies were originally performed for a variety of reasons such as prolonged neonatal jaundice, febrile illness or parents' request. Creatine phosphokinase (CK), alkaline phosphatase, direct bilirubin and gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT) were normal for the whole study duration. The children underwent the following investigations: a complete blood count, urinalysis, urea and creatinine, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), fT4, abdominal ultrasound, serology for hepatitis A, B, C, Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) and urinary CMV antigen. In addition, metabolic screening and immunological assessment with autoimmune markers, including anti‐tissue transglutaminase in those who had been exposed to gliadin‐related proteins, were performed.

Exclusion criteria included neonatal cholestasis, hepatomegaly and/or splenomegaly, clinical or laboratory signs of haemolysis, previous blood transfusion, obesity (above 85th percentile for age), a family history of liver disease, failure to attend regular clinic follow‐up, dysmorphism, a known chronic disease or abnormal course during the neonatal period, use of total parenteral nutrition, regular use of medications or herbs, personal contact with patients with hepatitis as well as any pathology in any of the above listed tests. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Statistical analysis

A comparison of continuous variables between the two groups was carried out using the t test or Mann Whitney test as appropriate. A χ2 test was performed for comparison of proportions between the two groups.

Results

Of 101 subjects with isolated elevation of serum aminotransferases screened for the study, 23 were eliminated due to insufficient data and six due to the finding of positive CMV antigen in the urine.

Thus, 72 patients were available for the study (47 boys and 25 girls). Table 1 presents the number of blood tests, the time of abnormal blood tests, and age at presentation. The ALT results are presented in fig 1.

Table 1 Basic results.

| Range | Mean (SD) | Median | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of blood tests | 2–9 | 4.4 (1.9) | 4.0 |

| Duration of abnormal serum | 3–36 | 12.5 (8.3) | 11.5 |

| aminotransferases (months) | |||

| Age at presentation (months) | 0–48 | 10.9 (12.8) | 6.5 |

Figure 1 ALT values over the study period.

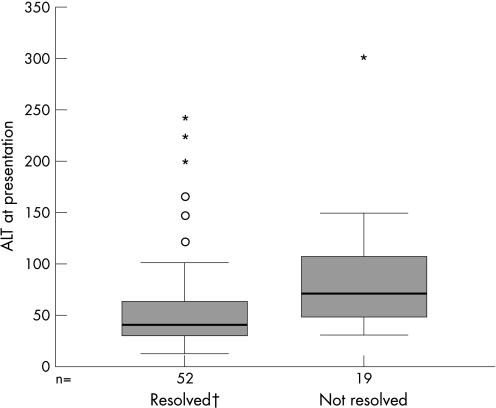

We divided the children into two groups: those in whom the serum aminotransferases normalised by the end of the study (n = 53, 73.6%) and those in whom they remained elevated (n = 19, 26.4%). We found that the group who normalised their serum aminotransferases had significantly lower initial and maximal ALT (mean 81.2 vs 97.4 IU/l, p = 0.013; mean 134.5 vs 157.3 IU/l, p = 0.039, respectively). These differences are presented graphically in fig 2. Although the age at presentation was slightly older in the group who normalised their serum aminotransferases (12.1 vs 7.6 months), these differences did not reach statistical significance. The period of follow‐up was identical for the two groups.

Figure 2 Differences in ALT levels at presentation according to normalisation. †One extreme case (ALT = 440) was not included.

Seventeen patients were offered a liver biopsy. Eight refused and two biopsies were cancelled on the day of biopsy due to normalisation of the serum aminotransferases. Of the seven children who had a biopsy, three showed an increased frequency of multi‐particulate type 1 glycogen particles in the hepatocytes suggesting the possibility of glycogen storage disease (GSD). This diagnosis was not confirmed by enzymatic assays for glycogen phosphorylase, debrancher, alpha glucosidase and phosphorylase kinase. Interestingly, the serum aminotransferases elevation resolved in two of the three subjects. The other four had non‐specific changes.

Information on breast feeding was available for 49 patients. Twenty nine children were breast fed for 1–8 months (mean (SD) 5.8 (1.4), median 6 months). Table 2 presents the differences between the two groups. Twenty six (90%) of the breastfed children normalised their serum aminotransferases compared to 14 (70%) of the non‐breastfed children. However, this difference was not significant. The only significant difference was the maximal ALT levels which were significantly lower in the breastfed infants.

Table 2 The effect of breastfeeding on liver enzyme levels.

| Breastfed, n = 29, mean (SD), | Non‐breastfed, n = 20, mean (SD), | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| median | median | ||

| Age at presentation | 14.5 (15.3) | 10.6 (10.5) | 0.61 |

| (months) | 9.0 | 9.5 | |

| Initial ALT (IU/l) | 54.0 (54.2) | 54.6 (35.4) | 0.45 |

| 38.0 | 42.5 | ||

| Initial AST (IU/l) | 73.4 (42) | 89.0 (79.5) | 0.65 |

| 64.0 | 59.0 | ||

| Maximal ALT (IU/l) | 87.2 (99.8) | 138.5 (129.1) | 0.04 |

| 60.0 | 89.0 | ||

| Maximal AST (IU/l) | 96.8 (62.5) | 122.5 (104.2) | 0.42 |

| 84.0 | 83.5 | ||

| Final ALT (IU/l) | 32.6 (34.4) | 31.9 (13.8) | 0.09 |

| 22.0 | 29.0 | ||

| Final AST (IU/l) | 50.8 (21.2) | 45.9 (15.1) | 0.97 |

| 41.0 | 42.0 | ||

| Duration of abnormal | 10.0 (6.9) | 12.8 (6.0) | 0.08 |

| serum | 9.0 | 13.0 | |

| aminotransferases | |||

| (months) |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

Discussion

We demonstrated that non‐cholestatic isolated elevation of serum aminotransferases in apparently healthy, thriving infants and young children is mostly a benign condition that usually resolves within a year. Since most healthy infants and children are not examined routinely for liver enzymes, we believe this may be the tip of the iceberg and probably this finding is much more common.

The most frequent viral infections causing hepatitis are hepatitis A, B, C, E, non‐A–E hepatitis, EBV and CMV. We studied serological markers for hepatitis A, B, C, EBV and CMV and also CMV antigen in the urine. None of the children screened had evidence of these infections. We did not investigate for hepatitis E serology. Nevertheless, although hepatitis E is endemic in Israel,15 it is rarely found in children and resolves within 4 weeks.15,16

The aetiology is unclear but may be related to some unknown viral aetiology, especially in febrile subjects. In the subgroup in which we did demonstrate an aetiology (not included in this study), urine CMV antigen was the most informative test. The results of other investigations in this group with non‐cholestatic abnormality were nearly all negative.

Several papers have attempted to determine normal values for serum aminotransferases in children. Infants under 1 year of age show higher serum aminotransferases than older subjects, mainly higher ALT levels.17 Landaas et al18 studied a group of 291 children and found that ALT levels were 14–84 U/l between 3 weeks and 4.5 months, and 11–46 U/l between 4.5 months and 1½ years. On the other hand, Gomez et al19 examined 2099 child outpatients and found only slightly higher ALT levels in the first year. Jorgensen et al20 found significantly higher AST levels at 2 and 6 months in infants who were exclusively breastfed compared to formula‐fed infants. We found that the group who normalised their serum aminotransferases was older, consumed more breast milk and had significantly lower initial and maximal ALT levels.

Iorio et al evaluated the prevalence of different causes of elevated aminotransferase levels in a large series of asymptomatic children referred for hypertransaminasaemia not due to major hepatotropic viruses.21 A total of 425 consecutive children with isolated hypertransaminasaemia were retrospectively evaluated. Of these, 61% normalised their liver enzymes during the first 6 months of observation, and 43.6% of these had no overt cause of hypertransaminasaemia. Of the 39% who had hypertransaminasaemia for more than 6 months, 75 had obesity‐related liver disease and 51 (12%) were found to have genetic disorders. No aetiology was found in only 22 children in this group. Liver biopsy, performed in 18 of the 22 patients, showed minimal chronic hepatitis in 12, mild chronic hepatitis in four and moderate chronic hepatitis in two children. Unlike our study, their study population was significantly older. In addition, they also evaluated patients with cholestasis and did not limit their patients to those who had negative findings at physical examination.

The decision whether or not to perform a biopsy in these children is controversial. Biopsy of the liver may be indicated following evaluation of abnormal biochemical liver tests in association with a serologic workup which is negative or inconclusive.22 The results of the liver biopsies including electron microscopy were not helpful and did not contribute much to the diagnosis, as also found in the study by Iorio et al.21 Liver biopsy is probably unnecessary in the majority of cases and should be reserved only for selected patients. Liver biopsy should probably be considered after 14–16 months of elevated aminotransferases. In those selected for a liver biopsy, it is recommended that besides regular light and electron microscopy, an additional sample should be taken and frozen at −70°C for further metabolic or GSD enzymatic assays if needed.

The liver biopsy electron microscopy findings were compatible with GSD in three of these children. Iorio et al21 demonstrated GSD type IX in three of their children. None of the children in our study had clinical or biochemical findings suggestive of GSD and in two, the liver enzyme abnormality spontaneously resolved. The reason for these findings has not been elucidated; they may be the result of a mild, possibly transient, metabolic abnormality or a mild form of GSD for which an enzyme has yet to be identified. Therefore, biochemical screening for GSD, including fasting glucose, lactate, urate, lipids and oligosaccharides, should be part of the investigation.

The main limitations of the study are its mostly retrospective nature. In addition, not all of the patients underwent complete workup since it was dependent on duration of abnormality. Nevertheless, this is the first report of a relatively large group of infants and young children with isolated elevation of serum aminotransferases that shows its mostly benign nature.

Conclusions

Non‐cholestatic isolated elevation of serum aminotransferases in an apparently healthy, thriving infants is mostly a benign condition that usually resolves within a year. The yield of broad investigation is low and if no pathology is found, these children can probably be followed conservatively.

What is already known on this topic

Incidental findings of isolated elevation of serum aminotransferases in infants and young children are not infrequent.

Currently, we do not have enough information in the literature regarding the management, clinical significance and prognosis of prolonged isolated elevation of serum aminotransferases without cholestasis in this population.

What this study adds

This study shows that non‐cholestatic isolated elevation of serum aminotransferases in apparently healthy, thriving infants is mostly a benign condition that usually resolves within a year.

The yield of the broad investigation is low and if no pathology is found, these children can probably be followed conservatively.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Michael Jaffe for help in reviewing the paper.

Abbreviations

ALT - alanine aminotransferase

AST - aspartate aminotransferase

CK - creatine phosphokinase

CMV - cytomegalovirus

EBV - Epstein‐Barr virus

GGT - gamma glutamyltransferase

GSD - glycogen storage disease

TSH - thyroid stimulating hormone

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.D'Agata I D, Balistreri W F. Evaluation of liver disease in the pediatric patient. Pediatr Rev 199920376–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moyer V, Freese D K, Whitington P F.et al Guideline for the evaluation of cholestatic jaundice in infants: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 200439115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenthal P, Sinatra F. Jaundice in infancy. Pediatr Rev 19891179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suchy F J. Neonatal cholestasis. Pediatr Rev 200425388–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Gastroenterological Association American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: evaluation of liver chemistry tests. Gastroenterology 20021231364–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goessling W, Friedman L S. Increased liver chemistry in an asymptomatic patient. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 20053852–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green R M, Flamm S. AGA technical review on the evaluation of liver chemistry tests. Gastroenterology 20021231367–1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathiesen U L, Franzen L E, Fryden A.et al The clinical significance of slightly to moderately increased liver transaminase values in asymptomatic patients. Scand J Gastroenterol 19993485–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minuk G Y. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Practice Guidelines: evaluation of abnormal liver enzyme tests. Can J Gastroenterol 199812417–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piton A, Poynard T, Imbert‐Bismut F.et al Factors associated with serum alanine transaminase activity in healthy subjects: consequences for the definition of normal values, for selection of blood donors, and for patients with chronic hepatitis C. MULTIVIRC Group. Hepatology 1998271213–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prati D, Taioli E, Zanella A.et al Updated definitions of healthy ranges for serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Ann Intern Med 20021371–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pratt D S, Kaplan M M. Evaluation of abnormal liver‐enzyme results in asymptomatic patients. N Engl J Med 20003421266–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rochling F A. Evaluation of abnormal liver tests. Clin Cornerstone 200131–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark J M, Brancati F L, Diehl A M. The prevalence and etiology of elevated aminotransferase levels in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 200398960–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karetnyi Y V, Favorov M O, Khudyakova N S.et al Serological evidence for hepatitis E virus infection in Israel. J Med Virol 199545316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aggarwal R, Krawczynski K. Hepatitis E: an overview and recent advances in clinical and laboratory research. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000159–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tietz N W.Clinical guide to laboratory tests. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: AACC Press, 1995

- 18.Landaas S, Skrede S, Steen J A. The levels of serum enzymes, plasma proteins and lipids in normal infants and small children. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem 1981191075–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez P, Coca C, Vargas C.et al Normal reference‐intervals for 20 biochemical variables in healthy infants, children, and adolescents. Clin Chem 198430407–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jorgensen M H, Ott P, Juul A.et al Does breast feeding influence liver biochemistry? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 200337559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iorio R, Sepe A, Giannattasio A.et al Hypertransaminasemia in childhood as a marker of genetic liver disorders. J Gastroenterol 200540820–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bravo A A, Sheth S G, Chopra S. Liver biopsy. N Engl J Med 2001344495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]