Abstract

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), ratified by most nations in 2000, set specific targets for poverty reduction, eradication of hunger, education, gender equality, health and environmental sustainability. MDG 4 aims to reduce child mortality with a target of reducing under‐five mortality rates by two thirds over the period 1990–2015. Over the last year, Live Aid, Make Poverty History, the G8 summits and prominent entertainers have directed unprecedented attention towards development and health. Africa particularly has been in the spotlight. Reports are published and commitments are made, but is there real progress? Are poor people being reached with essential health care? Who will hold leaders to account: celebrities, activists or health professionals?

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), ratified by most nations in 2000, set specific targets for poverty reduction, eradication of hunger, education, gender equality, health and environmental sustainability (table 1). “Countdown to 2015” grew out of The Lancet Child Survival and Neonatal Survival Series,1,2 as an accountability mechanism for the child survival goal which aims to reduce under‐five mortality rates by two thirds over the period 1990–2015. The first Countdown conference was held in London in December 2005 and focused primarily on child survival and MDG 4. Subsequent biannual conferences will track progress for MDGs 4 and 5 together,3 since maternal and child deaths have similar underlying causes and connected solutions. Countdown will focus on tracking progress in the 60 countries with the highest levels of mortality.4 It will monitor mortality rates, agree on key indicators, review coverage with essential child survival interventions, identify barriers to progress and how they can be addressed, and work on commitment and accountability by governments and international agencies (http://www.childsurvivalcountdown.com).

Table 1 The Millennium Development Goals and Targets.

| Goal | Target | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger | Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people whose income is less than US$1 a day |

| Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who suffer from hunger | ||

| 2 | Achieve universal primary education | Ensure that, by 2015, children everywhere, boys and girls alike, will be able to complete a full course of primary schooling |

| 3 | Promote gender equality and empower | Eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education, preferably by 2005, and in all levels of education no later |

| women | than 2015 | |

| 4 | Reduce child mortality | Reduce by two thirds, between 1990 and 2015, the under‐five mortality rate |

| 5 | Improve maternal health | Reduce by three quarters, between 1990 and 2015, the maternal mortality ratio |

| 6 | Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and | Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS |

| other diseases | Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the incidence of malaria and other major diseases | |

| 7 | Ensure environmental sustainability | Integrate the principles of sustainable development into country policies and programmes and reverse the loss of environmental resources |

| Halve, by 2015, the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and sanitation | ||

| By 2020, to have achieved a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers | ||

| 8 | Develop a global partnership for | Develop further an open, rule‐based, predictable, non‐discriminatory trading and financial system |

| development | Includes a commitment to good governance, development and poverty reduction, both nationally and internationally | |

| Address the special needs of the least developed countries | ||

| Includes: tariff and quota‐free access for least developed countries' exports; enhanced programme of debt relief for heavily indebted poor countries and cancellation of official bilateral debt; and more generous overseas development aid for countries committed to poverty reduction | ||

| Address the special needs of landlocked developing countries and small island developing states (through the Programme of Action for the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States and the outcome of the 22nd special session of the General Assembly) | ||

| Deal comprehensively with the debt problems of developing countries through national and international measures in order to make debt sustainable in the long term | ||

| In cooperation with developing countries, develop and implement strategies for decent and productive work for youth | ||

| In cooperation with pharmaceutical companies, provide access to affordable essential drugs in developing countries | ||

| In cooperation with the private sector, make available the benefits of new technologies, especially information and communications |

For further information see http://unstats.un.org/unsd/mi/mi_goals.asp.

Progress in reducing child deaths

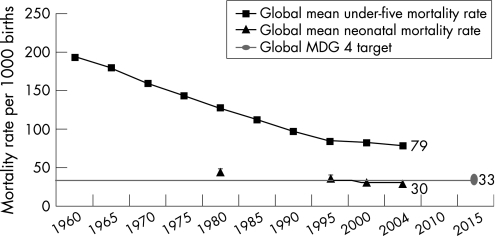

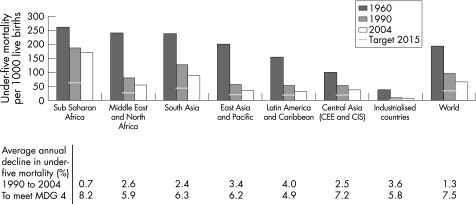

Each year 10.5 million children die, 4 million in the first month of life, mostly in Sub Saharan Africa (48%) and South Asia (35%). The MDG 4 target was projected from under‐five mortality trends from the 1960s to the 1980s, which had witnessed steady progress and an average global decline in under‐five mortality of over 3% per year (fig 1). By 2000, the picture had changed with the average global decline being almost flat in the later 1990s. Figure 2 shows the regional variation in decline in under‐five mortality rate since 1960. All regions have shown some decline. Since 1990, Latin America has made the fastest progress. South East Asia has made steady progress, although progress has been faster in some countries than in others. South Asia and North Africa and the Middle East have shown an average annual decline of 2.4% and 2.6% per year, but would need 6.2% and 5.9% per year to reach MDG 4. This is a challenging but achievable goal. For the South Asian regional target, if not the global target, much rests on India, where 2.2 million children die every year, half of them in the first month of life. Africa needs to increase its annual rate of mortality reduction almost seven‐fold, from 0.7% to over 8% per year, a 10‐fold increase in the rate of progress.

Figure 1 Global progress towards Millennium Development Goal 4 to improve child survival. Sources: UNICEF databases, WHO estimates of neonatal mortality and Demographic and Health Surveys data.

Figure 2 Progress towards Millennium Development Goal 4 of reducing under‐five mortality by two thirds by the year 2015, from the 1990 baseline according to world region. Sources: UNICEF's State of the world's children, various years; average annual rate of reduction to meet MDG 4 from UNICEF's Progress for children: a child survival report card. 2004, available from http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/29652L01Eng.pdf.

Africa: new hope for child mortality reduction?

Africa is often described as a continent in crisis for most MDG targets.5 For MDG 4, the average regional progress since 1990 has been very slow (0.7% reduction per year), but the regional figure hides national variation. Some countries in Africa, mainly with high HIV prevalence, have seen increases in under‐five mortality since 1990; these include Botswana, Cote d'Ivoire, Kenya, South Africa, Swaziland and Zimbabwe. Other countries such as Rwanda have been affected by armed conflicts. Most of the other larger countries in Africa have reported little change in under‐five mortality since the MDG baseline.

However, there are also reasons for optimism. A few countries have made steady progress: Eritrea has maintained a 4.1% average annual reduction in under‐five mortality for 25 years, despite having one of the world's lowest incomes per capita (US$180). In 2006, three high‐mortality countries with stagnant child death rates over the 1990s – Ethiopia, Malawi and Tanzania – reported reductions in under‐five mortality rates of 25–30% in the last 5 years based on large Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) (fig 3). In most of these countries, the proportion of neonatal deaths has now increased to around 30% of under‐five deaths.6

Figure 3 New hope in Africa? Recent rapid reductions in under‐five mortality in three large African countries based on new survey data. NMR, neonatal mortality rate; U5M, under‐five mortality. Sources: Country profiles. In: Lawn J, Kerber K, eds. Opportunities for Africa's newborns. PMNCH, Cape Town, South Africa. Data from UNICEF and from National Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) (http://www.measuredhs.com/statcompiler/). Note that the most recent data points for NMR and U5MR are final DHS results and that some of the other data points are modelled or adjusted data from DHS.

Why has child mortality fallen in some African countries?

These new data are not yet reflected in global or regional averages (figs 1 and 2), but perhaps they herald the start of a downward trend. Understanding the reasons for fluctuations in progress is not merely academic, it is essential to accelerating progress to save more lives now. Various explanations can be offered: improvements in sanitation, immunisation and malaria control, reductions in civil unrest and food insecurity, economic recovery and growth, rising female literacy, and improvements in health systems that can provide consistent preventive and curative care with increasing coverage.7 For Ethiopia, the period 2000–2005 saw the end of a 20 year war and relative food security for the first time in decades. Community perceptions may also be changing such that people see infant and childhood illness as actionable and remediable rather than taking a fatalistic view. Another major factor may be that in some countries the HIV epidemic has peaked and begun to fall. In Malawi and Tanzania, improvements in malaria control, and latterly HIV prevention, may have been important factors.

As post‐neonatal child mortality falls, an increasing proportion of child deaths occur in the neonatal period (now 38% globally, more in South Asia). Neonatal mortality is often not addressed by traditional public health and maternal and child health programmes,8 and stillbirths, which account for more than 3 million infant deaths, are excluded from the existing MDGs.9 Recent research has shown that community‐based strategies could have a powerful effect on neonatal mortality, but few of these interventions have been taken to scale by national governments, and newborn health has lacked investment, apart from US$110 million donated by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to establish the Saving Newborn Lives Initiative between 2000 and 2011.

A note of caution is necessary. Worldwide, 95% of under‐five deaths occur in countries without reliable vital registration data, and most information comes from DHS. Under‐five mortality rates do have fairly wide confidence intervals, and prospective pregnancy surveillance data show that DHS surveys under‐report early neonatal deaths.10 Countdown strongly advocates the need for better quality data for decision making for MDG progress monitoring.4,11

Progress in providing essential child health interventions

Recent analysis suggests that around two thirds of both child and neonatal deaths could be prevented with high coverage of existing, low‐technology interventions.12,13 New analysis combining mortality reduction estimation models used in The Lancet neonatal series and by the Bellagio group has estimated that 67% of under‐five deaths could be prevented if a selected list of known and feasible interventions reached all women, infants and children (http://cs.server2.textor.com/programme.html).

The most important direct causes of child death are neonatal (preterm, asphyxia, sepsis), pneumonia, diarrhoea and malaria. Malnutrition increases the risk of death due to infectious causes. Table 2 lists the major direct causes of child death and some illustrative essential interventions which could avert many child deaths if high coverage was achieved. For example, 19% of under‐five deaths are due to pneumonia, which could be avoided through correct case management and antibiotics at primary care level or by community health workers. Such approaches have gained ground, but 59% of children in Africa are still not taken for appropriate treatment, and in one study of the poorest households in a district in Tanzania, none were.14 Likewise, more than two thirds of children in Africa and South Asia do not receive the correct home management for diarrhoea. For neonatal problems like sepsis and preterm birth, we know that management of infection and kangaroo mother care are efficacious interventions, but data on coverage are not available and are likely to be extremely low.13 These interventions have the potential for tremendous public health effects on mortality rates and require urgent operational research to take them to scale.

Table 2 Coverage of essential life saving interventions for the six main causes of death for children under 5 years of age.

| Cause of under‐five deaths | Under‐five deaths (%) | Example of essential intervention | Coverage (% of population in need) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub Saharan Africa | South Asia | |||

| Pneumonia | 19 | Percentage of under fives with pneumonia taken to a health provider | 41 | 59 |

| Diarrhoea | 18 | Percentage of children with diarrhoea in the last 2 weeks who received | 34 | 26 |

| the correct home management | ||||

| Neonatal infections | 10 | Hygienic cord care | – | – |

| Percentage of neonates with sepsis taken to a health provider | ||||

| Preterm birth complications | 10 | Kangaroo mother care for preterm babies | – | – |

| Birth asphyxia | 9 | Percentage of women in childbirth cared for by a skilled attendant | 42 | 36 |

| Malaria | 8 | Percentage of children under five sleeping under an insecticide treated bed net | 15 | NA |

| Total of 10.5 million child | 74 | |||

| deaths | ||||

– indicates no data; NA, not applicable.

Sources: Cause of death data from Bryce J, Boschi‐Pinto C, Shibuya K, et al. WHO estimates of the causes of death in children. Lancet 2005;365:1147–1152. Coverage data based on UNICEF's State of the world's children 2006.

The importance of demand‐side factors

Both supply and demand approaches are needed to achieve a rapid increase in preventive practices, utilisation of interventions and care‐seeking behaviour. Essential interventions often embody a supply driven paradigm in which specific activities are transferred from experts to the public based on assumptions about the potential effectiveness of individual technologies as they achieve population coverage. This approach is compatible with the concept of users as “pawns”,15 passive recipients of preventive and curative treatment. There is, however, a scenario in which change comes from the public themselves, encapsulated in terms such as “demand side” and “agency”.16,17 Users are seen as “queens” rather than pawns, with the power to enact health‐promoting behaviours and to obtain treatments and interventions through their own knowledge and efforts (individual and collective) and through social networks that bring mothers and families together.

For newborn care in poor communities where many births occur at home, demand‐side interventions such as women's groups can have a powerful independent effect on mortality, even where service delivery is poor.18 Even vertical supply‐side programmes such as polio and tetanus immunisation can achieve greater public health returns when communities are active in their support.19

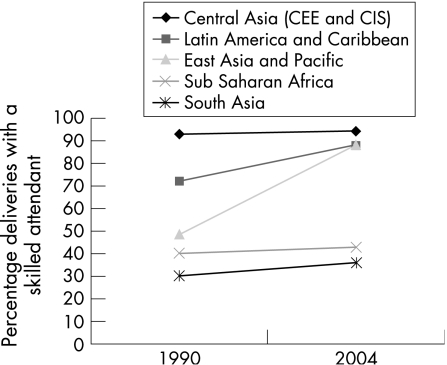

However, commodity‐driven interventions, such as insecticide‐treated nets for malaria or immunisations, may be rapidly scaled up. Countries like Vietnam, Laos and Mali have been highly successful at meeting the Abuja target of 80% bed net coverage from virtually zero in less than 5 years. Addressing other causes of child death such as birth asphyxia, as well as reducing maternal deaths, will need a longer‐term health systems approach to ensure skilled attendance at every birth. Figure 4 summarises current progress in scaling up skilled attendance by world region; the line is virtually flat for the two highest mortality regions of South Asia and Sub Saharan Africa.

Figure 4 Progress in scaling up coverage of deliveries with skilled attendance according to world region. Source: Data from UNICEF (see http://www.childinfo.org).

In Tanzania, a mixture of supply and demand‐side approaches has probably contributed to the recently reported fall in under‐five mortality and includes community mobilisation, access to integrated management of childhood illness, high immunisation coverage and promotion of bed nets.14 There is also a consistent focus on district level decision‐making and accountability within the health system.

Are the MDGs useful?

There has been some discussion of the rationale for the MDGs.5 It would be naive to see them simply as targets to be met. Ideally, they should stimulate collective benchmarking and are a work in progress. The indicators addressed by the MDGs do not stand alone but are enmeshed in a web of international concerns: changes in broader factors such as the balance of trade can affect health outcomes.20 Concerns have been voiced that the MDGs may be unrealistic and contribute to a sense of failure if they are not met. The strongest negative action for failure to meet a given goal is naming and shaming, but some countries with the least progress have other priorities higher than the deaths of their children. Naming is only effective if the leaders who can change the situation feel shame. Conversely, the strongest positive action once a goal is achieved, especially in a climate where countries feel set up to fail, is not only pride but also greater internal and external support to accelerate progress.

What have the MDGs achieved?

The most obvious effect of the MDGs to date has been to focus attention on saving lives and on reaching higher coverage of essential interventions. The explicit nature of the targets has stimulated concrete thinking by politicians, academics and other stakeholders.21 This has in turn highlighted just how little we know about child health in poor countries, a realisation that has happily coincided with the growth of an evidence‐based culture.22 Less than 10% of global research funding goes on conditions that affect more than 90% of the world's people (the 10/90 gap).23 There are larger gaps in our knowledge of health system strengthening: how to improve delivery, quality, access and uptake of services.24 We need better evidence, and to get better evidence we need better information. The MDGs have created a climate to consider definitions, measurement and how to track change.25 Good examples are work on financing and the cost‐effectiveness of potential strategies,26 health systems research24 and monitoring.27

Are we measuring the right indicators for child health and survival?

Given that aggregate figures are only useful up to a point, it is worth examining the idea of change in response to MDG 4. Changes may not be apparent from the chosen indicators (under‐five mortality, infant mortality and measles immunisation coverage), or the indicators may only tell part of the story. This is particularly the case for improvements in morbidity, wellbeing and social capital that are not reflected in mortality figures. Some authors suggest that a longer‐term health systems approach may be neglected if governments focus on commodity‐driven or vertical approaches to interventions.24

The MDG indicators may show improvements that are difficult to interpret. If the means to track progress to targets is lacking, the actual data we use might not be accurate. There might also be substantial improvements in child health that are not the result of MDG initiatives. It is likely that survival improvements will be attributed by governments and politicians to their actions, which could be harmful if it legitimises either a relaxing of effort or the maintenance of the status quo. Finally, the chosen indicators may be based on assumptions that do not hold. This is particularly true of coverage of essential interventions where the community effectiveness may be lower than predicted.

Investment and financing for child survival

Most development agencies now specifically link donor aid funding to MDG progress. However, Powell‐Jackson and colleagues estimate that donor spending on activities related to maternal, newborn and child health was US$1990 million in 2004, representing just 2% of gross aid disbursements to developing countries.28 The 60 priority low‐income countries that account for most child and newborn deaths received US$1363 million, or US$3.1 dollars per child. This level of aid to maternal, newborn and child health is inadequate to provide more than a small portion of the total resources needed to reach the MDGs.

Aid flows for child health are mainly focused on vertical programmes for vaccine delivery (the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation, GAVI), the President's Malaria Initiative, the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). In recent years, UNICEF and Save the Children (UK) had reduced the proportion of their funds committed to child survival,29 but with new leadership at both organisations this situation may change. UNICEF are showing strong signs of putting child survival at the core of their priorities. There is currently no Global Fund for mothers and children, but the new Global Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, formed in 2005 and led by Dr Francisco Songane, a former Minister of Health in Mozambique, has just received a welcome donation of US$35 million from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Some argue that donor finance should only be directed towards country programmes through basket funds held by recipient governments. This alone may not be adequate, especially in countries with instability where basket funding is not an option. Some of us have argued elsewhere that a Global Fund, ring‐fenced specifically for maternal and child health, is necessary to accelerate the flow of finances to where they are needed most.30 Whichever funding mechanism is used, there are many other problems to solve: limited financial absorptive capacity in ministries, loss of doctors and nurses through emigration or AIDS, political instability, a rigid organisational culture, corruption (public sector drugs and equipment are a target for criminals to make quick profits in parallel markets), and care which is often not user‐friendly or evidence‐based.

A major issue within countries is inequity in access. If the poorest quintile of households had a similar child mortality rate as the richest quintile, under‐five mortality would be reduced by 41% in Brazil, 54% in India and 59% in Indonesia.31 The inverse care law suggests that those who need services most have least access to them,32 and progress toward the MDGs may not be accompanied by reductions in inequalities within countries.33 There is some evidence for this,34 and also evidence that typical assessments of equity in health outcomes lack precision and that we might do better to take account of other factors.35 Any improvement in child survival is good, but if equity is an aim of the MDGs, countries and donors need to prioritise approaches which purposefully reach out to the most disadvantaged groups.36

What can paediatricians do for MDG 4?

If MDG4 is a “post‐it note” for child survival, a means of retaining focus on an important issue, can enough people see it? As an informed reader of ADC, you are probably aware of the MDGs, although maybe unable to summarise all of them, and perhaps not confident about the child health goal and exact target. Paediatricians working in developing countries may take heart that the MDGs can be invoked to make policy makers take heed of suggestions for improving child survival. Interventions that are likely to improve the survival of young children should, at least in principle, be welcomed. In many countries paediatricians already play a central role in leading the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness strategy (IMCI). The International Paediatric Association has recently led an initiative for paediatricians to be advocates for newborn survival in their countries (see http://www.ipachildhealth.org/). Twenty seven African Paediatric Associations have signed up and are forming newborn interest groups. This would benefit from technical and financial partnership from outside Africa.

In industrialised countries, paediatricians should be aware of child survival issues and consider formalising connections with colleagues in poorer settings. Collaboration on international committees, membership of pressure groups for international equity and child health, partnership with specific health providers in developing countries and opportunities for training and reciprocal service strengthening all deserve consideration. Whatever the realities of the MDGs, they give us a platform for advocacy and collaboration.

Conclusion

Given current progress, the Millennium Development Goal for child survival will not be met by 2015. According to the Countdown analysis, only seven of the 60 countries with the highest burden of under‐five mortality in 2004 are on track to achieve MDG 4: Bangladesh, Brazil, Egypt, Indonesia, Mexico, Nepal and the Philippines. Across Sub Saharan Africa a 10‐fold increase is required in the annual rate of reduction of under‐five mortality. Recent survey findings from Ethiopia, Tanzania and Malawi suggest that there is new hope of sizeable reductions in child mortality in those countries.

Coverage of child survival interventions to prevent or treat neonatal problems, pneumonia, diarrhoea, malaria, HIV and malnutrition has increased in some countries, but most essential interventions still reach less than half of the world's children, and poor children are the most likely to miss out. There is huge scope for improvement especially for skilled attendance at deliveries. Demand‐side interventions to empower communities are also effective but neglected.

Donor aid for child health is well below the investment necessary to improve health systems. Many donors view child health as little more than immunisation programmes, with occasional contributions from disease‐specific global funds. “Countdown to 2015” has called for accelerated action and investment focused specifically on health system strengthening to implement essential maternal, newborn and child health interventions on a large scale. Recent commitments by the UK prime minister, and from Norway, give hope for more rapid progress. Promises and commitments are easy, but action to reduce child mortality is dependent on consistent long‐term support.[37]

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Kate Kerber for the MDG 4 trend charts in fig 3.

Electronic‐database information

The following URLs have been mentioned in this article: Countdown to 2015. Child survival: http://www.childsurvivalcountdown.com/; Millennium Development Goals Indicators: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/mi/mi_goals.asp; UNICEF, Progress for children: http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/29652L01Eng.pdf; Tracking progress in child survival countdown to 2015: http://cs.server2.textor.com/programme.html; STATcompiler: http://www. measuredhs.com/statcompiler/; UNICEF, Monitoring the situation of children and women: http://www.childinfo.org; IPA, Healthy children for a healthy world: http://www.ipachildhealth.org/.

Abbreviations

DHS - Demographic and Health Surveys

MDGs - Millennium Development Goals

Footnotes

Joy Lawn is supported though a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to Saving Newborn Lives/Save the Children‐US. We thank the UK Department for International Development for their support for a Research Programme Consortium directed jointly by the UCL Centre for International Health and Development at the Institute of Child Health and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Competing interests: None.

The following URLs have been mentioned in this article: Countdown to 2015. Child survival: http://www.childsurvivalcountdown.com/; Millennium Development Goals Indicators: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/mi/mi_goals.asp; UNICEF, Progress for children: http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/29652L01Eng.pdf; Tracking progress in child survival countdown to 2015: http://cs.server2.textor.com/programme.html; STATcompiler: http://www. measuredhs.com/statcompiler/; UNICEF, Monitoring the situation of children and women: http://www.childinfo.org; IPA, Healthy children for a healthy world: http://www.ipachildhealth.org/.

References

- 1.Bellagio Study Group on Child Survival Child survival V. Knowledge into action for child survival. Lancet 2003362323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martines J, Paul V, Bhutta Z.et al Neonatal survival 4. Neonatal survival: a call for action, Lancet 20053651189–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horton R. The coming decade for global action on child health. Lancet 20063673–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryce J, Terreri N, Victora C.et al Countdown to 2015: tracking intervention coverage for child survival. Lancet 200668(9541)1067–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haines A, Cassels A. Can the millennium development goals be attained? BMJ 2004329394–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawn J, Kerber K.Opportunities for Africa's newborns: practical data, policy and programmatic support for strengthening newborn care in African countries. PMNCH: Cape Town, 2006

- 7.Huynh M, Parker J, Harper S.et al Contextual effect of income inequality on birth outcomes. Int J Epidemiol 200534888–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lawn J, Cousens S, Zupan J.et al Neonatal survival 1. 4 million neonatal deaths: When, Where? Why? Lancet 2005365891–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanton C, Lawn J, Rahman H.et al Stillbirth rates: delivering estimates in 190 countries. Lancet 20063671487–1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bang A, Reddy M, Deshmukh M. Child mortality in Maharashtra. Economic and Political Weekly 2002374947–4965. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horton R. The Ellison Institute: monitoring health, challenging WHO. Lancet 2005366179–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones G, Steketee R, Black R.et al Child survival II. How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet 200336265–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darmstadt G, Bhutta Z, Cousens S.et al Neonatal survival 2. Evidence‐based, cost‐effective interventions: how many newborn babies can we save, Lancet 2005365977–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masanja H, Schellenberg J, De Savigny D.et al Impact of Integrated Management of Childhood Illness on inequalities in child health in rural Tanzania. Health Policy Plan 200520(Suppl 1)S77–S84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Grand J.Motivation, agency and public policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003

- 16.Sen A.Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999

- 17.Ensor T, Cooper S. Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy Plan 20041969–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manandhar D, Osrin D, Shrestha B.et al Effect of a participatory intervention with women's groups on birth outcomes in Nepal: cluster randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2004364970–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Save the Children U S A. State of the world's mothers 2006. Saving the lives of mothers and newborns. http://www.savethechildren.org/publications/SOWM_2006_final.pdf (accessed 28 February 2007)

- 20.Moore S, Teixeira A, Shiell A. The health of nations in a global context: trade, global stratification, and infant mortality rates. Soc Sci Med 200663165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans D, Lim S, Adam T.et al Evaluation of current strategies and future priorities for improving health in developing countries. BMJ 20053311457–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garner P, Meremikwu M, Volmink J.et al Putting evidence into practice: how middle and low income countries “get it together”. BMJ 20043291036–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doyal L. Gender and the 10/90 gap in health research. Bull WHO 200482162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Travis P, Bennett S, Haines A.et al Overcoming health‐systems constraints to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. Lancet 2004364900–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Child Mortality Coordination Group Tracking progress towards the Millennium Development Goals: reaching consensus on child mortality levels and trends. Bull WHO 200684225–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adam T, Lim S, Mehta S.et al Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies for maternal and neonatal health in developing countries. BMJ 20053311107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhutta Z. The million death study in India: can it help in monitoring the Millennium Development Goals? PLoS Med 20063(2)e103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powell‐Jackson T, Borghi J, Mueller D H.et al Countdown to 2015: tracking donor assistance to maternal, newborn, and child health. Lancet 2006368(9541)1077–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horton R. UNICEF leadership 2005–2015: a call for strategic change. Lancet 20043642071–2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costello A, Osrin D. The case for a new Global Fund for maternal, neonatal, and child survival. Lancet 2005366603–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Victora C, Wagstaff A, Armstrong Schellenberg J.et al Child survival IV. Applying an equity lens to child health and mortality: more of the same is not enough, Lancet 2003362233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hart J. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971i(7696)405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Houweling T, Kunst A, Looman C.et al Determinants of under‐5 mortality among the poor and the rich: a cross‐national analysis of 43 developing countries. Int J Epidemiol 2005341257–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moser K, Leon D, Gwatkin D R. How does progress towards the child mortality millennium development goal affect inequalities between the poorest and least poor? Analysis of Demographic and Health Survey data. BMJ 20063311180–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wirth M, Balk D, Delamonica E.et al Setting the stage for equity‐sensitive monitoring of the maternal and child health Millennium Development Goals. Bull WHO 200684519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green A, Gerein N. Exclusion, inequity and health system development: the critical emphases for maternal, neonatal and child health. Bull WHO 200583402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]