Abstract

Previous research has shown that early maturing girls at age 11 have lower subsequent physical activity at age 13 in comparison to later maturing girls. Possible reasons for this association have not been assessed. This study examines girls’ psychological response to puberty and their enjoyment of physical activity as intermediary factors linking pubertal maturation and physical activity. Participants included 178 girls who were assessed at age 11, of whom 168 were reassessed at age 13. All participants were non-Hispanic white and resided in the U.S. Three measures of pubertal development were obtained at age 11 including Tanner breast stage, estradiol levels, and mothers’ reports of girls’ development on the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS). Measures of psychological well-being at ages 11 and 13 included depression, global self worth, perceived athletic competence, maturation fears, and body esteem. At age 13, girls’ enjoyment of physical activity was assessed using the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale and their daily minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) was assessed using objective monitoring. Structural Equation Modeling was used to assess direct and indirect pathways between pubertal development at age 11 and MVPA at age 13. In addition to a direct effect of pubertal development on MVPA, indirect effects were found for depression, global self worth and maturity fears controlling for covariates. In each instance, more advanced pubertal development at age 11 was associated with lower psychological well-being at age 13, which predicted lower enjoyment of physical activity at age 13 and in turn lower MVPA. Results from this study suggest that programs designed to increase physical activity among adolescent girls should address the self-consciousness and discontent that girls’ experience with their bodies during puberty, particularly if they mature earlier than their peers, and identify activities or settings that make differences in body shape less conspicuous.

Keywords: USA, Adolescent girls, Physical activity, Puberty, Psychological health, Depression, Well-being

Physical activity brings with it many health benefits including a reduced risk of morbidity and mortality due to obesity, type II diabetes and cardiovascular disease (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1996). Among children and adolescents, health benefits include lower rates of obesity (Trost, Kerr, Ward, & Pate, 2001), higher bone density (Bailey & Martin, 1994) better physical fitness (Morrow & Freedson, 1994) and more positive psychosocial health (Calfras & Taylor, 1994). The majority of children and adolescents in the US, however, do not meet recommendations for physical activity (Grunbaum, Kann, Kinchen, Ross, Hawkins, Lowry et al., 2004; Pate, Freedson, Sallis, Taylor, Sirard, Trost et al., 2002). Furthermore, research suggests that adolescence is a risk period for physical activity attrition, particularly among girls (Grunbaum et al., 2004).

Developmental Declines in Girls’ Physical Activity

Considerable evidence documents the developmental decline in girls’ physical activity across adolescence (Grunbaum et al., 2004; Kimm, Glynn, Kriska, Barton, Kronsberg, Daniels et al., 2002). In a 10-year longitudinal study of youth assessed across ages 9 to 19 years, rates of habitual physical activity among girls (including sports and leisure activities) declined by 83% from year 1 (ages 9–10 years) to year 10 (18–19 years) (Kimm et al., 2002). While declines in girls’ physical activity have been repeatedly documented, little research attention has been directed toward understanding factors leading to girls’ disengagement from physical activity. One particular factor that may lead to low physical activity among adolescent girls is pubertal development and their psychological response to the accompanying physical changes.

Pubertal Development, Pubertal Timing, and Girls’ Physical Activity

Puberty is a momentous transition in a young woman’s life, bringing with it a host of changes in her physical appearance and body shape. As girls develop breasts and gain weight, their self-perceptions may be drastically altered (Brooks-Gunn & Reiter, 1993). Coupled with a heightened awareness of peers, particularly of the opposite sex, these outwardly visible characteristics may contribute to significantly lower self esteem and self-image among girls (Kimm, Barton, Berhane, Ross, Payne, & Schreiber, 1997; Murdey, Cameron, Biddle, Marshall, & Gorely, 2004). Recent research has identified links between pubertal development, in particular pubertal timing, and girls’ physical activity. Using a longitudinal sample of girls assessed at ages 11 and 13 years, Baker, Birch, Trost and Davison (2006) found that 11-year-old girls who experienced puberty early relative to their peers had lower objectively measured physical activity at age 13 than later maturing girls, controlling for differences in physical activity and body fat at age 11. While the study by Baker et al (2006) is a significant step forward in identifying factors leading to declines in physical activity among adolescent girls, the mechanisms linking pubertal timing and physical activity were not analyzed.

Mechanisms Linking Early Pubertal Maturation and Physical Activity Among Girls

Early maturing girls may be particularly sensitive to the physical changes accompanying puberty and more vulnerable to the ensuing psychological effects than later maturing girls. Early maturing girls frequently report more negative initial experiences of puberty than their peers (Ruble & Brooks-Gunn, 1982). In particular, research suggests that early maturing girls may experience higher levels of psychological distress, anxiety, depression and psychosomatic symptoms than their later developing peers (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 1996; Graber, Lewinsohn, Seelery, & Brooks-Gunn, 1997; Kaltiala-Heino, Marttunen, Rantanen, & Rimpela, 2003; Laitinen-Krispijn, Van der Ende, Hazebroek-Kampschreur, & Verhulst, 1999; Rierdan & Koff, 1991). While it has been suggested that puberty itself predisposes girls to higher rates of depression regardless of pubertal timing (Angold, Costello, & Worthman, 1998), a number of studies provide evidence that ‘off-time’ girls, those maturing earlier and later than their peers, are subject to higher incidence of depressive symptoms (Graber et al., 1997; Rierdan & Koff, 1991; Siegel, Yancey, Aneshensel, & Schuler, 1999).

In addition to depression, the emotional complexities of early pubertal maturation among girls can contribute to a host of negative feelings about themselves, their bodies and their athletic competencies. Early maturing girls are more overweight, both preceding and following pubertal development, than their later maturing peers (Davison, Susman, & Birch, 2003a; Must, Naumova, Phillips, Blum, Dawson-Hughes, & Rand, 2005). As weight status increases, so do girls’ negative perceptions of their bodies (Davison, Markey, & Birch, 2003b; Murdey et al., 2004) and their athletic skills (Kolody & Sallis, 1995; Stein, Bracken, Haddock, & Shadish, 1998). Consequently, early maturing girls are more likely to express dissatisfaction with their body weight and report less positive body image and self image than later developing girls (Blythe, Simmons, & Zakin, 1985; Duncan, Ritter, Dornbusch, Gross, & Carlsmith, 1985; Murdey et al., 2004; Siegel et al., 1999). Furthermore, early maturing girls often experience higher levels of popularity with boys due to their early physical development (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2004). Poor body image and lower perceived competency in combination with this added attention may fuel feelings of self-consciousness among early maturing girls, particularly in the physical activity domain.

Negative affect or low psychological well-being among early maturing girls may contribute to negative perceptions of and motivation for physical activity and in turn low participation in physical activity. A recent study examining barriers to physical activity among adolescent girls found that the most consistently reported barrier was a feeling of self-consciousness (Robbins, Pender, & Kazanis, 2003). Other studies have confirmed self-consciousness and concerns about appearance as deterrents to participation in physical activity for adolescent girls (Leslie, Yancey, McCarthy, Albert, Wert, Miles et al., 1999; Taylor, Yancey, Leslie, Murray, Cummings, Sharkey et al., 1999). Similarly, low psychological well-being has been linked with lower enjoyment of physical activity (Ashford, Biddle, & Goudas, 1993). In turn, psychological well-being (Motl, Birnbaum, Kubik, & Dishman, 2004; Neumark-Sztainer, Stry, Hannan, Tharp, & Rex, 2003) and enjoyment of physical activity (Dishman, Motl, Saunders, Felton, Ward, Dowda et al., 2005; Motl, Dishman, Saunders, Dowda, Felton, & Pate, 2001) have been identified as significant predictors of physical activity in adolescent samples.

Goals of the Current Study

Building on the work of Baker and colleagues (2006), this study examines psychological mechanisms that may explain the association between earlier pubertal development and declines in physical activity among girls. Psychological factors that are examined include depression, global self worth, perceived athletic competence, body esteem, and concerns about weight due to pubertal maturation (i.e., maturity fears); these factors are referred to collectively as psychological well-being. In particular, this study assesses whether pubertal development at age 11 is associated with lower psychological well-being at age 13, controlling for self-reported physical activity and psychological well-being at age 11, and whether girls’ psychological well-being predicts their objectively-measured physical activity at age 13 either directly or indirectly via their enjoyment of physical activity.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 178 11-year-old (mean = 11.33, std = .28) non-Hispanic white girls who were part of a 10-year longitudinal study examining girls’ nutrition, dieting, physical activity and health, 168 of whom were reassessed at age 13 (mean=13.33, std = .28). Families were recruited for participation in the longitudinal study using flyers and newspaper advertisements. In addition, families with age-eligible female children within a 5-county radius in Pennsylvania, USA received mailings and follow-up phone calls. Families with age-eligible children were identified using data provided by Metromail, Inc., a national consumer database. Girls were not recruited based on preexisting physical activity behaviors or attitudes. The Institutional Review Board of the associated university approved all study procedures. Written consent from parents (for their daughters) and written assent from girls was obtained prior to girls’ completion of the study protocol.

Procedures

Girls visited the General Clinical Research Center at Pennsylvania State University during the summer of the years that they turned 11 and 13 years old. Girls’ pubertal development, self-reported physical activity, psychological well-being, and general demographic factors (e.g., family income) were assessed at this time. At age 13, trained research personnel visited girls during early fall (i.e., September and October) at their homes or at their schools to explain the accelerometer protocol and to give them their activity monitors. The monitors were returned by registered mail. All accelerometer data were collected during the school year to provide a more generalizable measure of girls’ physical activity and before the end of October to ensure that cold weather did not prevent girls from being active outdoors.

Measures: Background Variables

Parents’ years of education and combined family income were assessed using a brief background questionnaire. Mothers were asked to indicate the highest level of formal education from a list of 9 options for herself and her husband/partner. Responses were then converted to reflect the number of years of schooling. In addition, mothers reported the total family income from the following options: 0=<$20,000; 1= $20,000–$35,000; 2= $36,000–$50,000; 3=$51,000–$75,000; 4=$76,000–$100,000; 5=$100,000+. A composite family socioeconomic status (SES) score was created using Principal Component Analysis, specifying the retention of a single principal component.

Measures: Body Composition and Pubertal Development

Percent Body Fat

Dual-energy X-Ray absorptiometry (DXA) was used to measure percent body fat. Whole body scans were done using the Hologic QDR 4500W (S/N 47261) in the array scan mode and analyzed using whole body software, QDR4500 Whole Body Analysis. DXA has received widespread use and is the preferred method among children, because it provides an accurate, reliable, and non-invasive means of quantifying bone mineral content and body mass content, including fat and lean mass, while minimizing radiation exposure during measurement (Ellis, Shypailo, Pratt, & Pond, 1994; Goran, Driscoll, Johnson, Nagy, & Hunter, 1996; Lukaski, 1993; Mazess, Barden, Bisek, & Hanson, 1990).

Pubertal Development

Three measures of girls’ pubertal development were obtained at age 11. First, girls’ breast development was assessed using Tanner breast staging (Marshall & Tanner, 1969). Tanner stages range from 1 (no development) to 5 (mature development). Visual inspection of each breast was made unobtrusively by a trained nurse and nurse’s assistant while using a stethoscope to check heart rate. In cases where ratings of the two breasts were not equal, the lower stage was used because the girl had not fully attained the higher stage. Second, mothers provided information on their daughter’s pubertal development by completing the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS)(Peterson, Tobin-Richards, & Boxer, 1983). The PDS is a non-intrusive measure of pubertal development and consists of six items assessing growth or change in height, the presence of body hair (including underarm and pubic hair), skin changes (especially the presence of pimples), breast development, and menstruation. Previous research supports the reliability and validity of this scale (Peterson, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988; Peterson et al., 1983). Finally, blood samples collected on filter paper were used to measure girls’ circulating levels of estradiol (pg/mL). Girls arrived at the laboratory at 7:45 am after an overnight fast. All blood samples were collected between 8 am and 9 am. The samples were air dried and then frozen until assayed as outlined in Shirtcliff, et. al. (2000). The estradiol assay has been validated against serum samples in both adults and children and its sensitivity is sufficient for the detection of pre-pubertal levels of estradiol in girls (Shirtcliff et al., 2000). Specifically, the minimum concentration at which estradiol could be distinguished from 0 was 2 pg/mL. The intra assay coefficient of variation was 16% and the inter assay coefficient was 8.9%.

Measures: Enjoyment of Physical Activity

The Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) was originally developed by Kendzierski and DeCarlo (1991) and was later revised by Motl, Dishman, Saunders, Dowda, Felton & Pate (2001) for use with adolescents The revised scale uses 16 items (e.g., When I am active, I enjoy it, When I am active my body feels good). Participants respond to each statement using a 5-point scale from 1=disagree a lot to 5=agree a lot. Negatively worded items were reverse coded and scores across all items were averaged to create a total enjoyment score. In a biracial sample of adolescent girls, the internal consistency coefficients of the revised Enjoyment Scale ranged between α=.85 and α=.90 and 2 week test-retest reliability was r=.75, p<.01 (Motl et al., 2001). In addition, factorial invariance across racial group was established and scores illustrated concurrent validity with self-reported moderate to vigorous physical activity and sports involvement (Motl et al., 2001). In the current sample, the internal consistency coefficient for the Enjoyment Scale was α=.90.

Measures: Physical Activity

Self-reported Physical Activity

The Children’s Physical Activity Scale (CPA) was used to measure girls’ self-reported physical activity (Tucker, Seljaas, & Hager, 1997). The Physical Activity report includes 15 statements (e.g., I participate in sports almost every day) and uses a 4- point response scale ranging from 1=mostly false to 4=completely true. The internal consistency coefficient for this sample was α=.73 at age 11 and α=.77 at age 13. Previous research shows that scores on the Physical Activity report are significantly correlated with children’s one-mile run/walk time (r = −.43, p < 0001), body fat percentage (r = −.41, p <.0001), and BMI (r = − .32, p <.0001) (Tucker et al., 1997).

Objectively-Measured Physical Activity

Objective assessments of physical activity were obtained using the ActiGraph 7164 accelerometer (Shalimar, FL). The ActiGraph is a uniaxial accelerometer designed to detect vertical accelerations ranging in magnitude from 0.05 to 2.00 G’s with a frequency response of 0.25 – 2.50 Hz. These parameters allow for the detection of normal human motion and will reject high frequency vibrations encountered during activities such as operation of a lawn mower. The filtered acceleration signal is digitized, rectified, and integrated over a user-specified epoch interval. At the end of each epoch, the summed value or “activity count” is stored in memory and the integrator is reset. For the current study, a 30 s epoch was used. The Actigraph 7164 has been shown to be a valid and reliable tool for assessing physical activity in children and adolescents (Trost, Ward, Moorehead, Watson, Riner, & Burke, 1998).

After receiving detailed instructions regarding the care and use of the accelerometers, girls were instructed to wear the ActiGraph at all times, except bathing and swimming, for the 7 consecutive days. Consistent with previous research, the ActiGraph was worn on the right hip (mid-axilla line at the level of the iliac crest). To evaluate compliance with the monitoring protocol, each data file was screened for non-wearing time. Non-wearing time for each monitoring day was calculated by counting the number of zero counts accumulated in strings of 20 minutes or longer. A monitoring day was considered valid if wearing time (1440 minutes – non-wearing time) was equal to or greater than 10 hours (Masse, Fuemmeler, Anderson, Matthews, Trost, Catellier et al., 2005). Girls were included in the analyses if they had 4 or more valid monitoring days. Previous work has shown that 4 days of monitoring provides reliable estimates of usual physical activity in adolescent youth (Trost, McIver, & Pate, 2005). Data for 4 of the 149 girls who completed the accelerometer protocol were deleted based on these criteria. Therefore, 145 girls had valid accelerometer data.

Raw accelerometer counts were uploaded to a customized software program for determination of daily time (min) spent in moderate -to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA). The age-specific count thresholds corresponding to the aforementioned intensity levels were derived from the MET prediction equation developed by Freedson and co-workers (Freedson, Pober, & Janz, 2005; Trost, Pate, Sallis, Freedson, Taylor, Dowda et al., 2002). To accommodate the 30-sec epoch length, count thresholds were divided by 2 (Nilsson, Ekelund, Yngve, & Sjostrom, 2002).

Measures: Psychological Well-Being

Depression

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) was used to measure girls’ depression. The CDI, a widely used measure of depression for children and adolescents (Kovacs & Beck, 1977), consists of 27 items each made up of three statements graded in severity and scored from 0 to 2 (e.g., What do you think of yourself? 0=I like myself; 1=I do not like myself; 2=I hate myself). The child is asked to choose the statement that best describes him/her over the past 2 weeks. Scores are summed across the items yielding a total score ranging from 0 (no indication of depression) to 54 (high depressive tendencies). In a sample of elementary school (grades 3 to 6) and junior high school (grades 7 to 9) girls and boys, the internal consistency coefficient for the Inventory ranged between α=.84 to α=.87 (Smucker & Craighead, 1984) and 3-week test-retest reliability was r=.77, p<.001 for boys and r=.74, p<.001 for girls. In addition, parents’ and children’s reports of children’s depression were highly correlated (r=.74, p<.0001) in a sample of 8–11 year old children (Romano & Nelson, 1984). In the current sample, the internal consistency coefficient for the CDI was α=.78 at age 11 and α=.83 at age 13.

Perceived Athletic Competence and Global Self Worth

The Self Perception Profile for Children (SPP) is a 36-item scale assessing six dimensions of perceived competence including global self worth, athletic ability, social acceptance, physical appearance, behavioral conduct, and scholastic competence (Harter, 1985). Only global self worth (e.g., I like the kind of person I am) and perceived athletic competence (e.g., I think I could do well at just about any new athletic activity) were of interest in the present study. The Self-Perception Profile adopts a 4-point response scale from 1=really disagree to 4=really agree. Scores are averaged for each subscale to create a score ranging from 1 (low perceived competence) to 4 (high perceived competence). Previous research with the Profile in a large biracial sample of 11- and 12-year girls from the a Growth and Health Study supports the reliability and validity of the scale with white girls (Schumann, Striegel-Moore, McMahon, Waclawiw, & Morrison, 1999). Specifically, the factorial structure of the scale was confirmed among white girls and the internal consistency coefficients ranged between α=.72 (global self worth) to α=.79 (athletic competency). In the current sample, the internal consistency coefficients at ages 11 and 13 respectively were α=.82 and α=.82 for global self worth and α=.84 and α=.86 for perceived athletic competence.

Body Esteem

The Body Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults (BESAA) is a 23 item scale measuring three dimensions of body esteem including appearance-related body esteem (e.g., I wish I looked better), weight and body-shape related body esteem (e.g., I’m proud of my body, I like what I weigh) and body esteem attribution (e.g., Other people consider me good looking) (Mendelson, Mendelson, & White, 2001). Only weight and body-shape-related body esteem was of interest in the current study. Using a 5-point response scale (0=never to 4 =always), items for body esteem are averaged for each subscale to create a total score ranging from 0 to 4. Previous research with youth between the ages of 12- to 25-years supports the reliability and validity of the body esteem scale (Mendelson et al., 2001). Scores on the scale were positively correlated with scores on the Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale and the Global Self Worth Scale of the Self-Perception Profile. Three month test-retest reliability ranged between r=.83 (p<.001) and r=.92 (p<.001), and internal consistency coefficients ranged between α=.81 and α=.94. In this study, the internal consistency coefficients at ages 11 and 13 respectively were α=.92 and α=.93 respectively.

Maturity Fears

In the absence of a published and validated measure of girls’ adjustment to the physical changes of puberty, the Maturity Fears Scale (MFS) was developed for the larger longitudinal project (Sinton, Davison, & Birch, 2005). The scale has 18-items that assess girls’ awareness of changes, the social environment of changes, and weight- and body-shape-related discontent due to changes in their bodies. It uses a 4-point response scale (1=really false to 4 =really true). Only items assessing weight- and body-shape-related discontent (e.g., I think more about my weight now that my body is changing; I don’t like the changes in my body because they make me feel fat) were included in the present study. Scores for these items were averaged to create a total weight- and body-shape-related maturity fears score ranging from 1 to 4. Preliminary analyses with this sample at ages 11 and 13 years support the scale’s factorial structure, validity and reliability (Sinton et al., 2005). The internal consistency coefficients were α=.76 at ages 11 and 13 years.

Statistical Analyses

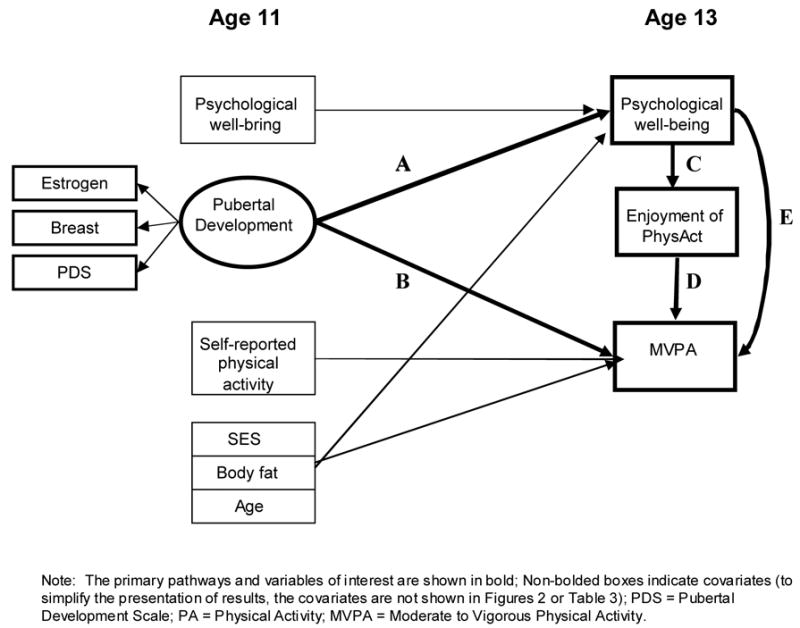

Bivariate associations between measures of girls’ pubertal development at age 11, psychological well-being at ages 11 and 13 years, physical activity at age 13 and covariates including age, percentage body fat and family SES were assessed using Spearman Rank Correlation Analysis. Structural Equation Modeling, using AMOS software, was used to assess girls’ psychological well-being and enjoyment of physical activity as possible explanatory mechanisms linking girls’ pubertal development at age 11 and their physical activity at age 13. A key strength of AMOS is its ability to model missing data using Maximum Likelihood estimation, thus enabling the use of all available information (Byrne, 2001). Models were run separately for each measure of psychological wellbeing. Girls’ pubertal development at age 11 was modeled as a latent construct using the three measures of pubertal development. As shown in Figure 1, a path modeling was constructed in which pubertal development at age 11 predicted psychological wellbeing at age 13, controlling for psychological well-being at age 11 (path A); the direct association between pubertal and objective physical activity (MVPA) was also modeled (path B). Psychological wellbeing at age 13 was, in turn, modeled as a direct predictor of girls’ MVPA at age 13 (path E), controlling for self-reported physical activity at age 11, and as an indirect predictor of MVPA via enjoyment of physical activity at age 13 (path D). Thus, the primary pathways of interest (as indicated in bold in Figure 1) were from pubertal development at age 11 to psychological wellbeing at age 13 (path A), to enjoyment of activity at age 13 (path C), and finally to MVPA at age 13 (path D). Analyses also controlled for girls’ age, body percentage fat (at age 11), and family SES (at age 11). Body fat was included as a covariate given previous research outlining links between body fat and pubertal timing (Blogowska, Rzepka-Gorska, & Krzyzanowska-Swiniarska, 2005; Davison et al., 2003a), physical activity (Trost et al., 2001), and psychological well-being (Presnell, 2004; Roberts, 2002).

Figure 1.

General model that was assessed for each measure of psychological well-being

Results

Sample Characteristics

Girls were generally from middle to upper income, well-educated families. The median family income was between $51,000 and $75,000 and mothers and fathers reported an average of 14.8 (2.3) and 14.9 (2.6) years of education respectively. As shown in Table 1, girls had in general begun pubertal development. The percentage of girls at each stage of breast development was 11% (S1), 61% (S2), 22% (S3), 5% (S4), and 1% (S5) at age 11, and 0% (S1), 5% (S2), 42% (S3), 28% (S4), and 25% (S5) at age 13 years. On average, girls reported low levels of depression and moderate to high levels of global self worth, perceived athletic competence, and body esteem. Finally, girls’ maturity fears were low to moderate and increased slightly between ages 11 and 13 years.

Table 1.

Mean (sd) scores for each measure of pubertal development, psychological well-being and physical activity

| Construct | Scale range | Age 11 | Age 13 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pubertal development | |||

| Tanner Breast Stage | 1 – 5 | 2.24 (.74) | 3.74 (.89) |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 0 – 21.76† | 6.42 (5.72) | - |

| Pubertal Development Scale | 1 – 4 | 2.05 (.47) | - |

| Psychological well-being | |||

| Depression | 0 – 17† | 3.54 (3.43) | 3.31 (2.92) |

| Global Self Worth | 1 – 4 | 3.51 (.45) | 3.55 (.45) |

| Perceived Athletic Competence | 1 – 4 | 2.95 (.63) | 2.84 (.63) |

| Body Esteem – weight related | 1 – 4 | 3.22 (.75) | 2.72 (.92) |

| Maturity Fears | 1 – 4 | 1.88 (.80) | 2.07 (.82) |

| Physical Activity | |||

| Self-reported physical activity | 1 – 4 | 2.95 (.35) | 2.78 (.41) |

| Enjoyment of physical activity | 1 – 4 | - | 4.24 (.60) |

| Objectively measured MVPA (min/day) | 4.64 – 83.64† | - | 35.40 (14.10) |

Range of scores in this sample

Correlations Between the Predictor Variables, Outcome Variables and Covariates

At age 11, significant negative associations were identified between body esteem and all three measures of pubertal development (see Table 2, columns 1–3). No other measures of psychological well-being were associated with pubertal development at age 11. At least one of the three measures of pubertal development at age 11 was significantly correlated (in the anticipated direction) with girls’ depression, global self worth, body esteem and maturity fears at age 13. Although few associations were identified between each measure of pubertal development and girls’ physical activity at age 13, correlations between girls’ MVPA and breast stage (r=−.16, p<.10) and scores on the Pubertal Development Scale (r=−.15, p<.10) were marginally significant.

Table 2.

Correlations between measures of pubertal development, psychological well-being, physical activity and possible covariates

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Estradiol (11) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Tanner Breast Stage (11) | .24** | |||||||||||||||||

| 3. Pubertal Dev S (11) | .40** | .34** | ||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Depression (11) | −.17 | .00 | −.11 | |||||||||||||||

| 5. Global Self Worth (11) | .15 | −.03 | .04 | −.50** | ||||||||||||||

| 6. Athletic Competence (11) | −.05 | .01 | −.07 | −.33** | .45** | |||||||||||||

| 7. Body Esteem (11) | −.19* | −.20** | −.19* | −.41** | .61** | .40** | ||||||||||||

| 8. Maturity Fears (11) | .03 | .09 | .10 | .46** | −.32** | −.20* | −.50** | |||||||||||

| 9. Depression (13) | −.02 | .18* | .09 | .46** | −.20** | −.20** | −.23** | .32** | ||||||||||

| 10. Global Self Worth (13) | −.06 | −.27** | −.15 | −.33** | .31** | .09 | .47** | −.31** | −.52** | |||||||||

| 11. Athletic Competence (13) | −.03 | −.12 | −.06 | −.20** | .21** | .54** | .30** | −.19* | −.30** | .28** | ||||||||

| 12. Body Esteem (13) | −.18* | −.25** | −.24** | −.26** | .23** | .18* | .62** | −.44** | −.51** | .67** | .34** | |||||||

| 13. Maturity Fears (13) | .08 | .26** | .23** | .27** | −.22** | −.13 | −.51** | .43** | .53** | −.61** | −.22** | −.75** | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| 14. Self-rept PhysAct (13) | −.12 | −.19* | −.16 | −.12 | .17** | .37** | .21* | −.13 | −.29** | .31** | .60** | .30** | −.19* | |||||

| 15. MVPA (13) | −.12 | −.16 | −.15 | −.11 | .11 | .16 | .19* | −.02 | −.09** | .21* | .36** | .20* | −.07 | .38** | ||||

| 16. Enjoyment of PhysAct (13) | −.02 | −.06 | −.11 | −.26** | .15 | .37** | .28** | −.06 | −.34** | .36** | .56** | .32** | −.24** | .49** | .28** | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| 17. Percentage Body Fat (11) | .17 | .19* | .17* | .13 | −.15 | −.20* | −.50** | .31** | .15 | −.20* | −.18* | −.57** | .30** | −.23** | −.16 | −.17 | ||

| 18. Age (11) | .25** | .19* | .00 | −.06 | .08 | .07 | −.04 | .11 | .13 | −.25** | −.02 | −.17* | .18* | −.08 | −.02 | −.04 | .05 | |

| 19. SES (11) | .00 | −.14 | −.07 | −.05 | .12 | −.02 | .13 | −.11 | −.06 | .17* | −.07 | .18* | −.15* | −.25** | −.03 | −.13 | −.20* | .00 |

p<.05

p<.01

With respect to the covariates shown at the bottom of Table 2, girls’ percentage body fat was significantly correlated with 2 out of 3 measures of pubertal development and most measures of psychological well-being at ages 11 and 13 years. Sporadic associations were noted between age and SES and the key variables of interest in the study. Finally, the five measures of psychological well-being exhibited moderate inter-correlations within each age group and a moderate degree of stability across time.

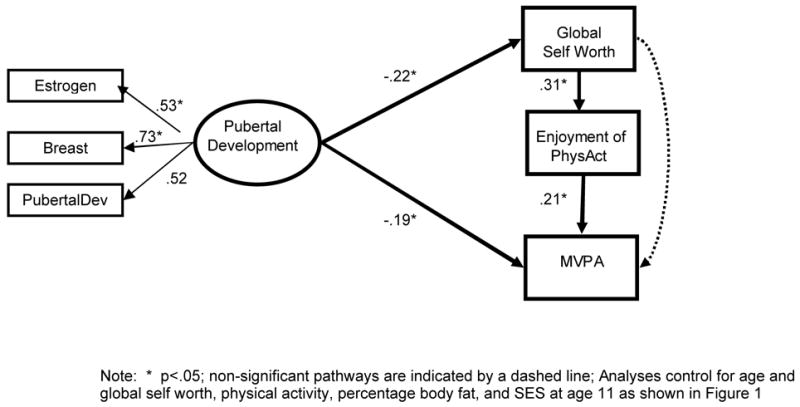

Psychological Well-Being and Enjoyment Of Physical Activity as Intermediary Factors Linking Girls’ Pubertal Development and Physical Activity

The path model that was assessed for each measure of psychological well-being is illustrated in Figure 1. The results from the analyses are presented in Figure 2 and Table 3. A direct association between pubertal development and MVPA was identified in all models, with more advanced pubertal development at age 11 predicting fewer minutes of MVPA at age 13, controlling for differences in age, percentage body fat, SES and self-report physical activity at age 11. For the models including perceived athletic ability and body esteem there was no evidence of an additional indirect association between pubertal development and MVPA via the psychological variable and enjoyment of physical activity. That is, pubertal development was not associated with perceived athletic competence or body esteem, after controlling for covariates. For the models assessing global self worth, depression, and maturity fears, both direct and indirect effects of pubertal development on MVPA were identified.

Figure 2.

Associations between pubertal development at age 11 and global self worth, enjoyment of physical activity, and MVPA at age 13

Table 3.

Results from path models assessing psychological well being and enjoyment of physical activity as intermediary factors linking puberty and physical activity

| Measure of psychological well-being | Pathway from Figure 1 |

Intermediary effects of psychological well-being and enjoyment of PA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | ||

| Global Self Worth | −.22* | −.19* | .31* | .21* | .01 | Yes |

| Depression | .23* | −.19* | −.33* | .24* | .12 | Yes |

| Perceived Athletic Competence | −.04 | −.18* | .53 | .13 | .19* | No |

| Body Esteem | −.11 | −.20 | .27* | .23* | .10 | No |

| Maturity Fears | .22* | −.22* | −.16* | .24* | .18† | Yes |

Note: p<.10

p<.05;

PA = physical activity; All models control for age and psychological wellbeing, physical activity, percentage body fat, and SES at age 11.

For global self worth, more advanced pubertal development at age 11 was associated with significantly lower global self worth at age 13 (path A), controlling for global self worth at age 11 (see Figure 2 and Table 3). Low global self worth at age 13 predicted low enjoyment of physical activity at age 13 (path C), which in turn was associated with lower MVPA (path D) independent of physical activity at age 11 and global self worth at age 13. These effects were independent of age, percentage body fat, and SES. Similar effects were noted for depression and maturity fears. Specifically, more advanced pubertal development at age 11 was associated with significantly higher depression and maturity fears at age 13 (path A) controlling for the measure of psychological well-being at age 11. Higher depression and maturity fears were in turn associated with lower enjoyment of physical activity (path C) and lower enjoyment predicted lower MVPA (path D) independent of the specified covariates.

Discussion

Recent research shows that early maturing girls at age 11 exhibit lower objectively measured physical activity at age 13 than later maturing girls, suggesting that early pubertal maturation may lead adolescent girls to disengage from physical activity (Baker et al., 2006). This study builds on research to date by assessing psychological mechanisms that may explain the link between pubertal timing and physical activity among girls. Overall, results from this study indicate that more advanced pubertal development at age 11 predicted lower psychological well-being at age 13 including depression, weight-related maturity fears, and low self worth. Furthermore, lower psychological well-being at age 13 predicted lower enjoyment of physical activity, which in turn predicted lower MVPA. Consequently, results from this study suggest that girls’ psychological response to early pubertal maturation at age 11 and its effect on their enjoyment of physical activity may partially explain why early maturing girls are less physically active at age 13.

Links between pubertal development and psychological well-being were evident for 3 out of 5 measures of well-being. Significant effects were found for depression (e.g., I hate myself, I have difficulty sleeping), global self worth (e.g., I am often disappointed with myself), and weight-related maturity fears (e.g., I don’t like the changes in my body because they make me feel fat) but not body esteem (e.g., I think I have a good body) or perceived athletic competence (e.g., I do well at most sports). Multicolinearity among the psychological well-being variables cannot explain the noted results as shown by the pattern of correlations in Table 2. Specifically, the variables for which there were significant effects did not represent a subset of variables with high intercorrelations. In addition, the absence of an effect for perceived athletic competence may be due to a non-linear association between pubertal timing and girls’ perceived athletic competence. For example, more advanced pubertal maturation at an early age (e.g., 11 years) may be perceived as an advantage for some sports (e.g., swimming) and a disadvantage for others (e.g., gymnastics). The absence of an effect for body esteem may be the result of controlling for percentage body fat in the analyses. It was necessary to control for body fat in the analyses because higher body fat or overweight status is linked with both the independent (i.e., pubertal development) and dependent (i.e., physical activity) variables (Davison et al., 2003a; Trost et al., 2001). Controlling for body fat, however, likely had the largest effect on the model including body esteem due to the high correlation between body fat and body esteem (Table 2, row 17). Thus, it cannot be ruled out that low body esteem also plays a role in the link early maturation and girls’ physical activity, particularly if this association is due to increases in body fat associated with pubertal maturation.

Results from this study have implications for the promotion of physical activity among adolescent girls. Efforts may be needed to help girls, particularly early maturing girls, feel better about themselves (enhance self-worth) and their bodies and to effectively adjust to their changing body shape during puberty. These efforts should begin before girls enter puberty. Approaches to decrease girls’ self consciousness about their bodies while being active should be identified. For example, uniforms could be less revealing and give girls more freedom of body movement. It is possible that early maturing girls may reject activities such as gymnastics and swimming due to their higher body fatness (Davison et al., 2003a) and greater concern about their weight (weight-related maturity fears). In such situations, parents and coaches could help girls identify activities with less of a focus on body shape including leisure activities such as walking or bike riding and sports such as soccer and volleyball. In addition, positive self worth could be promoted among girls in a physical activity setting by the use of team building activities rather than focusing on competition.

This study also has implications for the delivery of school-based physical education programs. The discontent that some girls have with their bodies during pubertal development suggests that physical education programs may be more effective in promoting physical activity among maturing girls if they are delivered in a gender-separated manner. Supporting this assertion are the results of the recently completed Lifestyle Education for Activity Project or Project LEAP (Pate, Ward, Saunders, Felton, Dishman, & Dowda, 2005), a group-randomized, comprehensive, school-based intervention on physical activity in high school girls. The LEAP intervention provided a choice-based, gender-segregated physical education curriculum that helped female participants build physical activity self-efficacy, increase enjoyment of physical activity, and develop behavioral skills needed to live a physically active lifestyle. The intervention had positive effects on girls self-reported vigorous physical activity (Pate et al., 2005), which were partially explained by increases in girls’ perceived self-efficacy (Dishman, Motl, Saunders, Felton, Ward, Dowda et al., 2004) and enjoyment of physical education (Dishman et al., 2005).

Findings here are consistent with previous research showing that early pubertal maturation is associated with negative psychological well-being among girls (Graber et al., 1997) and that psychological well-being (Biddle, Whitehead, O’Donovan, & Nevill, 2005) and enjoyment of physical activity (Dishman et al., 2005) predict physical activity among youth. Moreover, findings from this study build on previous research. In particular, it is the first study to assess associations between pubertal development and psychological well-being, enjoyment of physical activity and objectively measured moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, and the process by which these constructs may be linked using a longitudinal sample of adolescent girls.

Key strengths of this study include the use of a longitudinal design, the use of multiple measures of girls’ pubertal development and their psychological response to puberty, and the use of objective measures of girls’ pubertal development, percentage body fat, and physical activity. There are also a number of limitations to this study, which could be addressed in future research. The primary limitation of this study is that the results cannot be generalized beyond white girls from middle-income, well-educated families. A second limitation is that an objective assessment of girls’ physical activity was not available at age 11. Consequently, self-reported physical activity at age 11 was used as a covariate in the analyses. While research indicates that there are moderate correlations between self-reported and objectively measured physical activity (Kohl, Fulton, & Caspersen, 2000), an objective measure of physical activity at age 11 would have been optimal. In addition, enjoyment of physical activity was not assessed at age 11 therefore it was not possible to control for early levels of enjoyment.

In conclusion, early maturation was linked with depression, low self worth, and concern about one’s weight as a result the physical changes of puberty. These factors in turn predicted low enjoyment of physical activity and low MVPA. Programs to promote physical activity among adolescent girls should identify ways to increase girls’ positive self worth and reduce feelings of self consciousness about their changing bodies.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by NIH grants to Davison, K.K. (HD 46567-01) and Birch, L.L. (HD 32973, M01 RR10732). We would like to thank the participating girls and their families.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr Kirsten Krahnstoever Davison, University at Albany Rensselaer, NY UNITED STATES.

Jessica L Werder, University at Albany, jw244296@albany.edu.

Stewart G Trost, Kansas State University, strost@ksu.edu.

Birgitta L Baker, Pennsylvania State University, blb257@psu.edu.

Leann L Birch, Pennsylvania State University, llb15@psu.edu.

References

- Altabe M. Ethnicity and body image: Quantitative and qualitative analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;23(2):153–159. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199803)23:2<153::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Worthman CM. Puberty and depression: The roles of age, pubertal status and pubertal timing. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:51–61. doi: 10.1017/s003329179700593x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford D, Biddle S, Goudas M. Participation in community sports centers: motives and predictors of enjoyment. Journal of Sports Science. 1993;11(3):249–256. doi: 10.1080/02640419308729992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey D, Martin A. Physical activity and skeletal health in adolescents. Pediatric Exercise Science. 1994;6:330–347. [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, Birch LL, Trost SG, Davison KK. Advanced pubertal status at age 11 and lower physical activity in adolescent girls. Journal of Pediatrics. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.017. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddle S, Whitehead S, O’Donovan T, Nevill M. Correlates of participation in physical activity for adolescent girls: A systematic review of recent literature. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2005;2:423–434. [Google Scholar]

- Blogowska A, Rzepka-Gorska I, Krzyzanowska-Swiniarska B. Body composition, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and leptin concentrations in girls approaching menarche. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2005;18(10):975–983. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2005.18.10.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blythe DA, Simmons RB, Zakin DF. Satisfaction with body image for early adolescent females: the impact of pubertal timing within different school environments. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1985;14(3):207–225. doi: 10.1007/BF02090319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Reiter EO. The role of pubertal processes. In: Feldman SS, Elliott GR, editors. At the threshold. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Calfras KJ, Taylor WC. Effects of physical activity on psychological variables in adolescents. Pediatric Exercise Science. 1994;6:406–423. [Google Scholar]

- Davison K, Susman E, Birch L. Percent body fat at age 5 predicts earlier pubertal development among girls at age 9. Pediatrics. 2003a;111(4):815–821. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison KK, Markey CN, Birch LL. A longitudinal examination of patterns in girls’ weight concerns and body dissatisfaction from ages 5- to 9-years old. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003b;33:320–332. doi: 10.1002/eat.10142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishman R, Motl R, Saunders R, Felton G, Ward D, Dowda M, et al. Self-efficacy partially mediates the effect of a school based physical education intervention among adolescent girls. Preventive Medicine. 2004;38:628–636. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishman R, Motl R, Saunders R, Felton G, Ward D, Dowda M, et al. Enjoyment mediates effects of a school-based physical-activity intervention. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2005;37(3):478–487. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000155391.62733.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan PD, Ritter PL, Dornbusch SM, Gross RT, Carlsmith JM. The effects of pubertal timing on body image, school behavior, and deviance. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1985;14(3):227–235. doi: 10.1007/BF02090320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis KJ, Shypailo RJ, Pratt JA, Pond WG. Accuracy of dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry for body-composition measurements in children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1994;60:660–665. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.5.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedson PS, Pober D, Janz KF. Calibration of accelerometer output for children. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2005;S37(11):S523–530. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185658.28284.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Coming of age too early: pubertal influences on girls’ vulnerabiity to psychological distress. Child Development. 1996;67:3386–3400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goran M, Driscoll P, Johnson R, Nagy T, Hunter G. Cross-calibration of body-composition techniques against dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in young children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1996;63:299–305. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Lewinsohn PM, Seelery JR, Brooks-Gunn J. Is psychopathology associated with the timing of pubertal development? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(12):1768–1776. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199712000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunbaum J, Kann L, Kinchen S, Ross J, Hawkins J, Lowry R, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly. 2004;53(SS2):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the Self Perception Profile for Children: Revision of the Perceived Self Competence Scale for Children. Denver, CO: University of Denver; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino R, Marttunen M, Rantanen P, Rimpela M. Early puberty is associated with mental health problems in middle adolescence. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:1055–1064. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00480-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendzierski D, DeCarlo K. Physical activity enjoyment scale: Two validation studies. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 1991;13:50–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kimm SYS, Barton BA, Berhane K, Ross JW, Payne G, Schreiber GB. Self esteem and adiposity in black and white girls: the NHLBI growth and health study. Annals of Epidemiology. 1997;7(8):550–560. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimm SYS, Glynn NW, Kriska AM, Barton BA, Kronsberg SS, Daniels SR, et al. Decline in physical activity in black girls and white girls during adolescence. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(10):709–715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl H, Fulton J, Caspersen C. Assessment of physical activity among children and adolescents. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31:S11–S33. [Google Scholar]

- Kolody B, Sallis J. A prospective study of ponderosity, body image, self-concept and psychological variables in children. Journal of Development and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1995;16(1):1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Beck A. An empirical-clinical approach toward a definition of childhood depression. In: Schulterbrandt J, Raskin A, editors. Depression in childhood: Diagnosis, treatment and conceptual models. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1977. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen-Krispijn S, Van der Ende J, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AAJM, Verhulst FC. Pubertal maturation and the development of behavioural and emotional problems in early adolescence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1999;99:16–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb05380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie J, Yancey A, McCarthy W, Albert S, Wert C, Miles O, et al. Development and implementation of a school-based nutrition and fitness promotion program for ethnically diverse middle-school girls. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1999;99(8):967–970. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukaski HC. Soft tissue composition and bone mineral status: Evaluation by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. The Journal of nutrition. 1993;123(2):438–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Archives of Diseases in Children. 1969;44:291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masse LC, Fuemmeler BF, Anderson CB, Matthews CE, Trost SG, Catellier DJ, et al. Accelerometer data reduction: a comparison of four reduction algorithms on select outcome variables. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2005;37(11 Suppl):S544–554. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185674.09066.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazess RB, Barden HS, Bisek JP, Hanson J. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry for total-body and regional bone-mineral and soft-tissue composition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51(6):1106–1112. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.6.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA. A longitudinal study of pubertal timing and extreme body change behaviors among adolescent boys and girls. Adolescence. 2004;39(153):145–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson B, Mendelson M, White D. Body Esteem Scale for Adolescents and Adults. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2001;76(1):90–106. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7601_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow J, Freedson P. Relationship between habitual physical activity and aerobic fitness in adolescents. Pediatric Exercise Science. 1994;6:315–329. [Google Scholar]

- Motl R, Dishman R, Saunders R, Dowda M, Felton G, Pate R. Measuring enjoyment of physical activity in adolescent girls. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;21(2):110–117. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00326-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motl RW, Birnbaum AS, Kubik MY, Dishman RK. Naturally occurring changes in physical activity are inversely related to depressive symptoms during adolescence. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:336–342. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000126205.35683.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdey ID, Cameron N, Biddle SJH, Marshall SJ, Gorely T. Pubertal development and sedentary behavior during adolescence. Annals of Human Biology. 2004;31(1):75–86. doi: 10.1080/03014460310001636589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Must A, Naumova EN, Phillips SM, Blum M, Dawson-Hughes B, Rand WM. Childhood overweight and maturational timing in the development of adult overweight and fatness: the Newton Girls Study and its follow-up. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):620–627. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Stry M, Hannan P, Tharp T, Rex J. Factors associated with changes in physical activity: A cohort study of inactive adolescent girls. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:803–810. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson A, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sjostrom M. Assessing Physical Activity Among Children With Accelerometers Using Different Time Sampling Intervals and Placements. Pediatric Exercise Science. 2002;14:87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Pate R, Ward D, Saunders R, Felton G, Dishman R, Dowda M. Promotion of physical activity among high-school girls: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1582–1587. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.045807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate RR, Freedson PS, Sallis J, Taylor WC, Sirard J, Trost SG, et al. Compliance with physical activity guidelines: Prevalence in a population of children and youth. Annals of Epidemiology. 2002;12:303–308. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson A, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure pf pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson A, Tobin-Richards M, Boxer A. Puberty: Its measurement and its meaning. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1983;3:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Presnell KK. Risk Factors for Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescent Boys and Girls: A Prospective Study. The international journal of eating disorders. 2004;36(4):389–401. doi: 10.1002/eat.20045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rierdan J, Koff E. Depressive symptomalogy among very early maturing girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20(4):415–425. doi: 10.1007/BF01537183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins LB, Pender NJ, Kazanis AS. Barriers to physical activity perceived by adolescent girls. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2003;48(3):206–212. doi: 10.1016/s1526-9523(03)00054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RER. Are the fat more jolly? Annals of behavioral medicine. 2002;24(3):169–180. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano B, Nelson R. Discriminant and concurrent validity of measures of children’s depression. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1984;17:255–259. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble DN, Brooks-Gunn J. The experience of Menarche. Child Development. 1982;53:1557–1566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann B, Striegel-Moore R, McMahon R, Waclawiw M, Morrison JSGB. Psychometric properties of the Self-Perception Profile for Children in a biracial cohort of adolescent girls: The NHLBI Growth and Health Study. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1999;73(2):260–275. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7302_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirtcliff EA, Granger DA, Schwartz EB, Curran MJ, Booth A, Overman WH. Assessing estradiol in biobehavioral studies using saliva and blood spots: simple radioimmunoassay protocols, reliability, and comparative validity. Hormones & Behavior. 2000;38(2):137–147. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2000.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JM, Yancey AK, Aneshensel CS, Schuler R. Body image, perceived pubertal timing and adolescent mental health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;25:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinton M, Davison K, Birch L. Evaluating the association between girls’ reactions to pubertal development and girls’ risk for body dissatisfaction and disordered eating. International Conference on Eating Disorders; Montreal, Canada. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Smucker M, Craighead WCLW, Green BJ. Normative and reliability data for the Children’s Depression Inventory. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1984;14:25–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00917219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein R, Bracken B, Haddock C, Shadish W. Preliminary analyses of the Children’s Physical-Self Concept Scale. Journal of Development and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1998;19(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WC, Yancey A, Leslie J, Murray NB, Cummings SS, Sharkey SA, et al. Physical activity among African American and Latino school girls; consistent beliefs, expectations, and experiences across two sites. Women and health. 1999;30(2):67–82. doi: 10.1300/j013v30n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S, Corwin S, Sargent R. Ideal body size beliefs and weight concerns of fourth-grade children. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;21(3):279–284. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199704)21:3<279::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost S, Kerr L, Ward D, Pate R. Physical activity and determinants of physical activity in obese and non-obese children. International Journal of Obesity. 2001;25:822–829. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost S, McIver K, Pate R. Conducting accelerometer-based activity assessments in field-based research. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2005;37(11 suppl):S531–543. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185657.86065.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost S, Ward D, Moorehead S, Watson P, Riner W, Burke J. Validity of the computer science and applications (CSA) activity monitor in children. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1998;30(4):629–633. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199804000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost SG, Pate RR, Sallis JF, Freedson PS, Taylor WC, Dowda M, et al. Age and gender differences in objectively measured physical activity in youth. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2002;34:350–355. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200202000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LA, Seljaas GT, Hager RL. Body fat percentage of children varies according to their diet composition. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1997;97:981–986. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00237-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1996. [Google Scholar]