Abstract

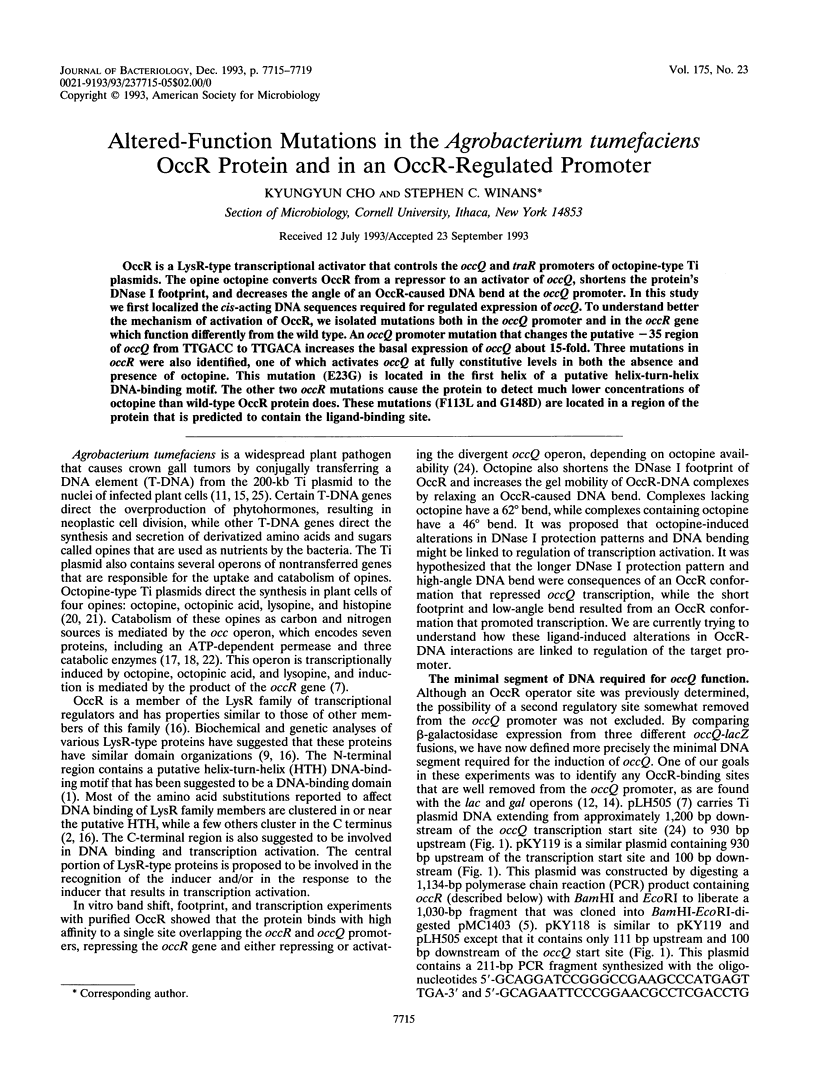

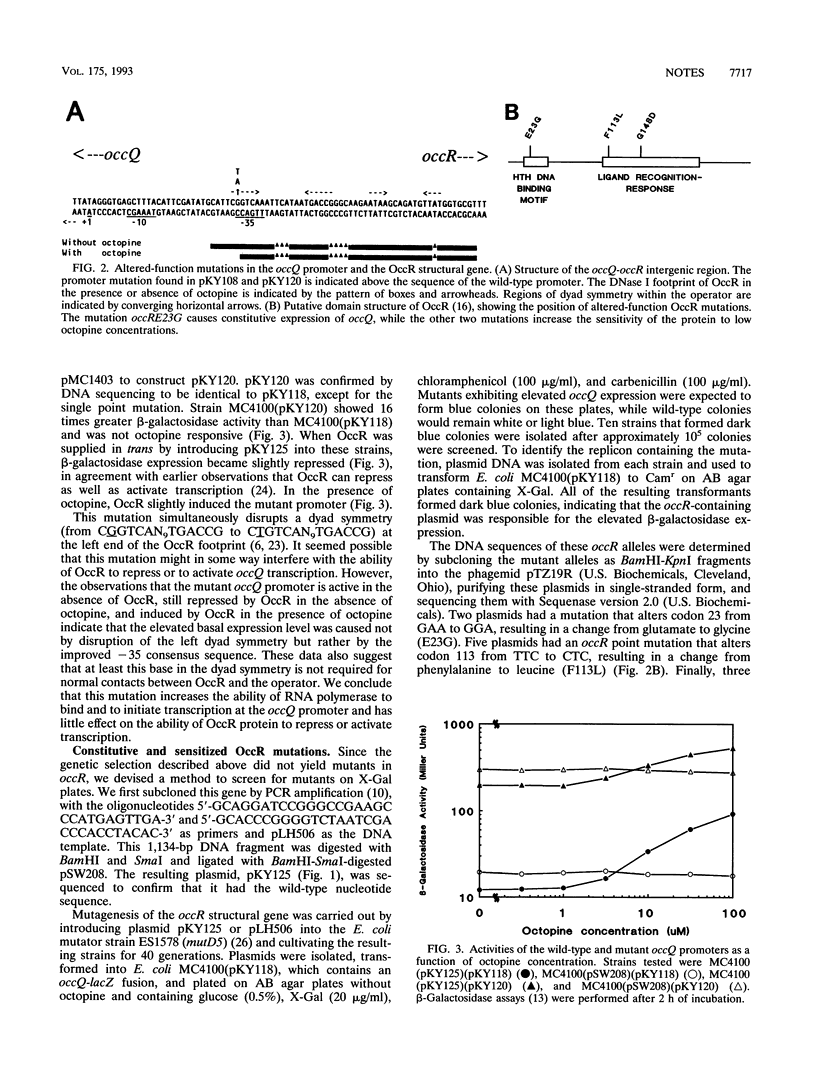

OccR is a LysR-type transcriptional activator that controls the occQ and traR promoters of octopine-type Ti plasmids. The opine octopine converts OccR from a repressor to an activator of occQ, shortens the protein's DNase I footprint, and decreases the angle of an OccR-caused DNA bend at the occQ promoter. In this study we first localized the cis-acting DNA sequences required for regulated expression of occQ. To understand better the mechanism of activation of OccR, we isolated mutations both in the occQ promoter and in the occR gene which function differently from the wild type. An occQ promoter mutation that changes the putative -35 region of occQ from TTGACC to TTGACA increases the basal expression of occQ about 15-fold. Three mutations in occR were also identified, one of which activates occQ at fully constitutive levels in both the absence and presence of octopine. This mutation (E23G) is located in the first helix of a putative helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif. The other two occR mutations cause the protein to detect much lower concentrations of octopine than wild-type OccR protein does. These mutations (F113L and G148D) are located in a region of the protein that is predicted to contain the ligand-binding site.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Brennan R. G., Matthews B. W. The helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif. J Biol Chem. 1989 Feb 5;264(4):1903–1906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burn J. E., Hamilton W. D., Wootton J. C., Johnston A. W. Single and multiple mutations affecting properties of the regulatory gene nodD of Rhizobium. Mol Microbiol. 1989 Nov;3(11):1567–1577. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangelosi G. A., Best E. A., Martinetti G., Nester E. W. Genetic analysis of Agrobacterium. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:384–397. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04020-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadaban M. J., Chou J., Cohen S. N. In vitro gene fusions that join an enzymatically active beta-galactosidase segment to amino-terminal fragments of exogenous proteins: Escherichia coli plasmid vectors for the detection and cloning of translational initiation signals. J Bacteriol. 1980 Aug;143(2):971–980. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.2.971-980.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habeeb L. F., Wang L., Winans S. C. Transcription of the octopine catabolism operon of the Agrobacterium tumor-inducing plasmid pTiA6 is activated by a LysR-type regulatory protein. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1991 Jul-Aug;4(4):379–385. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-4-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley D. K., McClure W. R. Compilation and analysis of Escherichia coli promoter DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983 Apr 25;11(8):2237–2255. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.8.2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henikoff S., Haughn G. W., Calvo J. M., Wallace J. C. A large family of bacterial activator proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Sep;85(18):6602–6606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal N., Su W., Haber R., Adhya S., Echols H. DNA looping in cellular repression of transcription of the galactose operon. Genes Dev. 1990 Mar;4(3):410–418. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.3.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oehler S., Eismann E. R., Krämer H., Müller-Hill B. The three operators of the lac operon cooperate in repression. EMBO J. 1990 Apr;9(4):973–979. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler U., Sans N., Schröder J. Ornithine cyclodeaminase from octopine Ti plasmid Ach5: identification, DNA sequence, enzyme properties, and comparison with gene and enzyme from nopaline Ti plasmid C58. J Bacteriol. 1989 Feb;171(2):847–854. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.847-854.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz G. E. A critical evaluation of methods for prediction of protein secondary structures. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1988;17:1–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.17.060188.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdivia R. H., Wang L., Winans S. C. Characterization of a putative periplasmic transport system for octopine accumulation encoded by Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid pTiA6. J Bacteriol. 1991 Oct;173(20):6398–6405. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.20.6398-6405.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Helmann J. D., Winans S. C. The A. tumefaciens transcriptional activator OccR causes a bend at a target promoter, which is partially relaxed by a plant tumor metabolite. Cell. 1992 May 15;69(4):659–667. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90229-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winans S. C. Two-way chemical signaling in Agrobacterium-plant interactions. Microbiol Rev. 1992 Mar;56(1):12–31. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.12-31.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T. H., Clarke C. H., Marinus M. G. Specificity of Escherichia coli mutD and mutL mutator strains. Gene. 1990 Mar 1;87(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90488-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]