Abstract

Cell cycle checkpoints that monitor DNA damage and spindle assembly are essential for the maintenance of genetic integrity, and drugs that target these checkpoints are important chemotherapeutic agents. We have examined how cells respond to DNA damage while the spindle-assembly checkpoint is activated. Single cell electrophoresis and phosphorylation of histone H2AX indicated that several chemotherapeutic agents could induce DNA damage during mitotic block. DNA damage during mitotic block triggered CDC2 inactivation, histone H3 dephosphorylation, and chromosome decondensation. Cells did not progress into G1 but seemed to retract to a G2-like state containing 4N DNA content, with stabilized cyclin A and cyclin B1 binding to Thr14/Tyr15-phosphorylated CDC2. The loss of mitotic cells was not due to cell death because there was no discernible effect on caspase-3 activation, DNA fragmentation, or viability. Extensive DNA damage during mitotic block inactivated cyclin B1-CDC2 and prevented G1 entry when the block was removed. The mitotic DNA damage responses were independent of p53 and pRb, but they were dependent on ATM. CDC25A that accumulated during mitosis was rapidly destroyed after DNA damage in an ATM-dependent manner. Ectopic expression of CDC25A or nonphosphorylatable CDC2 effectively inhibited the dephosphorylation of histone H3 after DNA damage. Hence, although spindle disruption and DNA damage provide conflicting signals to regulate CDC2, the negative regulation by the DNA damage checkpoint could overcome the positive regulation by the spindle-assembly checkpoint.

INTRODUCTION

In mammalian cells, DNA damage checkpoints operate throughout the cell cycle to maintain genetic integrity. These checkpoints ensure that damaged DNA is not replicated in S phase or segregated to the daughter cells in mitosis until repaired. DNA damage checkpoints delay cell cycle progression by inhibition of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)–cyclin complexes. Cyclin–CDK complexes are key regulators of the cell cycle: cyclin D–CDK4/6 for G1 progression, cyclin E–CDK2 for the G1-S transition, cyclin A–CDK2 for S phase progression, and cyclin A/B–CDC2 for M-phase entry (reviewed in Poon, 2002).

DNA damage checkpoints in G1 and S phase are characterized by rapid responses involving cyclin D1 and CDC25A, and a slower response involving p53. Cyclin D1 is rapidly degraded by ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent mechanisms after DNA damage, resulting in the redistribution of the CDK inhibitors p21CIP1/WAF1 and p27KIP1 from cyclin D1–CDK4/6 to cyclin A/E–CDK2 (Poon et al., 1995; Agami and Bernards, 2000; Miyakawa and Matsushime, 2001). CDK2 is also inactivated by Thr14/Tyr15-phosphorylation after DNA damage-induced degradation of CDC25A (again through phosphorylation, by the ATM-CHK2 pathway) (Falck et al., 2001). A slower response of the G1 DNA damage checkpoint is carried out by the activation of p53. MDM2, one of the transcriptional targets of p53, inhibits p53-mediated transcription, shuttles p53 out of the nucleus, and targets p53 for ubiquitin/proteasome-mediated proteolysis (reviewed in Prives, 1998). Several DNA damage-induced protein kinases (ATM, ATR, DNA-PK, CHK1, and CHK2) phosphorylate sites in the N-terminal region of p53 and inhibit the binding of MDM2 to p53 (Chehab et al., 2000; Hirao et al., 2000; Shieh et al., 2000). The resulting activation of p53 increases the expression of p21CIP1/WAF1 and leads to the inhibition of cyclin–CDK2 complexes.

The G2 DNA damage checkpoint exerts its effects mainly through inhibitory phosphorylation of CDC2 (reviewed in Zhou and Elledge, 2000). In normal human fibroblasts, p21CIP1/WAF1 is sufficient for the inhibition of cyclin A/E–CDK2, but it is not responsible for the inhibition of the mitotic cyclin A/B–CDC2 after DNA damage (Levedakou et al., 1995; Poon et al., 1996). Instead of binding to p21CIP1/WAF1, the mitotic cyclin A/B–CDC2 complexes are inhibited by phosphorylation on Thr14/Tyr15 (Jin et al., 1996; Poon et al., 1997). After DNA damage, ATM/ATR phosphorylates and activates CHK1/CHK2, which in turn phosphorylates CDC25C on Ser216. This either directly inactivates the phosphatase activity of CDC25C, or indirectly through the creation of a 14-3-3 binding site (Blasina et al., 1999; Lopez-Girona et al., 2001). Destruction of another member of the CDC25 family, CDC25A, is necessary to prevent damaged cells from entering mitosis (Mailand et al., 2002).

Apart from its involvement in the G1 control, p53 is also implicated in the maintenance of the G2 DNA damage checkpoint (reviewed in Taylor and Stark, 2001). Progression through G2 may be affected by p53 through its activation of 14-3-3σ (a protein that normally sequesters cyclin B1-CDC2 in the cytoplasm) and p21CIP1/WAF1; Bunz et al., 1998; Chan et al., 1999), or its repression of the cyclin B1 promoter (Innocente et al., 1999; Passalaris et al., 1999). However, it has also been reported that neither p21CIP1/WAF1 nor 14-3-3σ prevents mitotic entry, but p21CIP1/WAF1 may induce cell cycle arrest in the resulting tetraploid cells (Andreassen et al., 2001a).

The spindle-assembly checkpoint, which inhibits the onset of anaphase until all chromosomes are attached to the mitotic spindles, maintains high level of active cyclin–CDC2 through inhibition of the APC/C (reviewed in Millband et al., 2002). The spindle-assembly checkpoint itself does not require p53, but the prevention of DNA reduplication when cells are adapted from spindle disruption involves p53 and p21CIP1/WAF1 (Cross et al., 1995; Minn et al., 1996; Di Leonardo et al., 1997; Lanni and Jacks, 1998; Notterman et al., 1998).

Compared with the DNA damage responses during G2, considerably less is known about the DNA damage responses during mitosis. Exactly how mammalian cells respond to DNA damage during mitosis has been a contentious issue (Smits et al., 2000; Mikhailov et al., 2002). Smits et al. (2000) showed that DNA damage during nocodazole block inhibits mitotic exit after the block is removed. The damaged cells maintain a 4N DNA content and high levels of cyclin B1 and MPM-2. The effects of DNA damage on mitotic cells were attributed to an inactivation of PLK1 (Smits et al., 2000) through an ATM/ATR-dependent mechanism (van Vugt et al., 2001). Using live cells analysis, however, Mikhailov et al. (2002) concluded that extensive DNA damage delays exit from mitosis not by ATM-dependent mechanism but by disruption of kinetochore functions.

Because both spindle-disrupting drugs and DNA-damaging drugs are important chemotherapeutic agents, we are interested in the underlying molecular mechanisms of DNA damage responses while the spindle-assembly checkpoint is activated. When the spindle-assembly checkpoint is activated, active cyclin B1–CDC2 accumulates and the cell is maintained in prometaphase-like state. Sustained activation of cyclin B1–CDC2 is necessary to prevent cells from going into anaphase with unattached kinetochores. The G2 DNA damage checkpoint, on the other hand, keeps cyclin B1-CDC2 inactive by phosphorylation of Thr14/Tyr15. Hence, the spindle-assembly checkpoint and DNA damage checkpoint send out conflicting signals to control CDC2. We present evidence that DNA damage during mitotic block triggered CDC2 inactivation, histone H3 dephosphorylation, and chromosome decondensation. Damaged cells retracted to G2-like state containing 4N DNA content, with stabilized cyclin A and cyclin B1 binding to Thr14/Tyr15-phosphorylated CDC2. Finally, we show that the mitotic DNA damage responses were dependent on ATM and correlated with the destruction of CDC25A. Ectopic expression of CDC25A or nonphosphorylatable CDC2 effectively inhibited the dephosphorylation of histone H3 after DNA damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless stated otherwise.

DNA Constructs

Human CDC25A cDNA was a gift of Hiroto Okayama (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan). The cDNA was digested with NcoI and HindIII and ligated into pBluescript KS(+)3 × HA vector (Ito et al., 1999). The NotI fragment containing 3HA-CDC25A was subcloned into pCAGGS vector (Niwa et al., 1991). GST-CDC25A in pGEX-KG was constructed by ligation of the BglII-PstI and Klenow-treated fragment of CDC25A into EcoR I-cut and Klenow-treated pGEX-KG. The resulting fusion protein lacked the first 169 residues of CDC25A. Cyclin A2 in pET21d was as described (Yam et al., 2000). The NcoI-EcoR I of cyclin B1(NΔ88)-H6 in pET21d (Yam et al., 2001) was put into NcoI-EcoR I-cut pUHD-P1 (Yam et al., 1999) to produce FLAG-cyclin B1(NΔ88) in pUHD-P1. FLAG-CDC2 in pUHD-P1 was constructed by polymerase chain reaction amplification of the CDC2 cDNA with the oligonucleotides 5′-GAGAATTCATGGAAGATTATACCAAAA-3′ (CDC2 forward) and 5′-TCGAATTCCTACATCTTCTTAATCTG-3′; the polymerase chain reaction product was cut with EcoR I and put into EcoR I-cut pUHD-P1. FLAG-CDC2(T14A+Y15F) in pUHD-P1 was constructed the same way except that the CDC2 forward oligonucleotide was replaced by 5′-GAGAATTCATGGAAGATTATACCAAAATAGAGAAAATTGGAGAAGGTGCCTTTGGAG-3′.

Cell Culture

HeLa (human cervical carcinoma) and HepG2 (human hepatoblastoma) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Normal diploid human fibroblasts (GM04390), normal human lymphoblastoid cells (GM03798), and ataxia-telangiectasia (AT) lymphoblastoid cells (GM03189) were obtained from Coriell Cell Repositories (Camden, NJ). E1A-immortalized wild-type mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and p53–/– MEFs were gifts from Dr. Richard Woo (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Hong Kong). Cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) calf serum (HeLa), 15% fetal bovine serum (lymphoblastoid cells), or 10% fetal bovine serum (other cells) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Unless stated otherwise, cells were treated with the following reagents at the indicated final concentration: adriamycin (ADR) (0.2 μg/ml; ∼0.4 μM), caffeine (5 μM), cisplatin (CIS) (4 μg/ml), camptothecin (CMP) (0.7 μM), etoposide (ETP) (10 μg/ml), Ac-Leu-Leu-norleucinal (50 μM), nocodazole (NOC) (0.1 μg/ml), and Taxol (5 μg/ml). Trypan blue analysis was performed as described previously (Siu et al., 1999). For mitotic spread, cells were trypsinized, washed, and incubated in 2 ml of 0.56% KCl at 37°C for 20 min. The cells were collected by centrifugation and fixed in 4 ml of 3:1 MeOH/acetic acid at 25°C for 30 min. Cells were again collected by centrifugation and applied onto slides. Slides were air-dried and stained with Giemsa stain at 25°C for 15 min. The slides were then washed with water and examined under light microscopy. More than 300 cells were scored for each experiment, and only cells with clearly resolved mitotic figures were regarded as mitotic cells. Images were captured with a color cooled charge-couple device camera (CoolSnap; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). Release of cells from NOC block, transient transfection, and preparation of cell-free extracts were performed as described previously (Poon et al., 1995).

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry after propidium iodide staining was performed as described previously (Siu et al., 1999). Both floating and attached cells were collected.

Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis Assay

The method for detecting DNA breaks in individual cells was performed as described by Singh et al. (1988) by using the pH >13 electrophoresis buffer.

Expression of Recombinant Proteins and In Vitro Degradation Assay

Coupled transcription-translation reactions in the presence of [35S]methionine in rabbit reticulocyte lysate were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). Expression and purification of glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged proteins from Escherichia coli (Poon et al., 1993), and in vitro protein degradation assays (Fung et al., 2002) were performed as described previously.

Histone H1 Kinase Assays and Phosphatase Assays

Histone H1 kinase assays were performed as described previously (Poon and Hunter, 1995). Phosphorylation was detected and quantified with a PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The conditions for GST-CDC25A treatment were as described previously (Poon et al., 1997).

Antibodies and Immunological Methods

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation were performed as described previously (Poon et al., 1995). Polyclonal antibodies against CDC2, CDK2 (Li et al., 2002), cyclin B1 (Poon et al., 1994), and FLAG tag (Wang et al., 2001) were as described previously. Polyclonal antibodies against Ser139-phosphorylated histone H2AX were gifts from Junjie Chen (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). Rat monoclonal antibodies YL1/2 against tubulin, monoclonal antibody (mAb) E23 against cyclin A2, A17 against CDC2, and PC10 against proliferating cell nuclear antigen were gifts from Julian Gannon and Tim Hunt (Cancer Research UK, London, United Kingdom). Anti-cyclin E mAb HE12 was a gift from Emma Lees (DNAX Research Institute, Palo Alto, CA). mAb M2 against FLAG tag was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Tyr15-phosphorylated CDC2 were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Monoclonal antibodies against p53 (sc-126), caspase-3 (sc-7272), CDC25A (sc-7389), cyclin B1 (sc-245), and Ser10-phosphorylated histone H3 (sc-8656R), and polyclonal antibodies against p21CIP1/WAF1 (sc-397) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

RESULTS

Topoisomerase (Topo) Inhibitors-induced DNA Damage during Spindle-Assembly Disruption

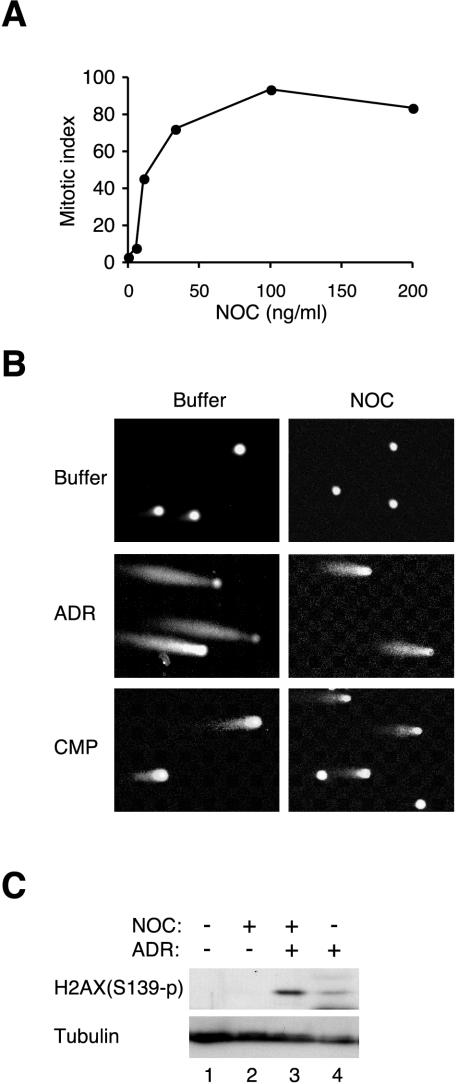

To see whether radiomimetic drugs can trigger DNA damage when the spindle-assembly checkpoint is activated, we investigated whether DNA breaks were generated by using single cell gel electrophoresis assay (comet assay). About 90% of cells exhibited mitotic figures when HeLa cells were incubated with 100 ng/ml microtubule assembly inhibitor NOC for 16 h before DNA damage (Figure 1A). Further incubation in NOC did lead to some increases in apoptosis and adaptation (see below). Unless stated otherwise, NOC or other drugs were not washed out and were continuously applied in this study. Figure 1B shows that although NOC alone did not trigger DNA damage, addition of Topo inhibitors promoted the appearance of “comets” in both mocktreated and NOC-blocked cells.

Figure 1.

Topoisomerase poisons trigger DNA damage during mitotic block. (A) HeLa cells were treated with different concentrations of NOC for 16 h. Mitotic index was analyzed as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. (B) HeLa cells were treated with either buffer or NOC for 16 h. Control buffer, ADR, or CMP was then added (without prior washing), and the cells were incubated for another 16 h. The cells were then harvested for single cell gel electrophoresis assay as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. (C) HeLa cells were treated with either buffer or NOC for 16 h. Buffer or ADR was then added and the cells were incubated for another 16 h. Cell extracts were prepared and Ser139-phosphorylated histone H2AX was detected by immunoblotting. Tubulin analysis was included to assess protein loading and transfer.

We also used phosphorylation of histone H2AX as an indicator of DNA double-stranded breaks (Rogakou et al., 1998) (Figure 1C). Although NOC alone did not trigger histone H2AX phosphorylation, addition of ADR after NOC-block induced robust histone H2AX phosphorylation. Finally, activation of proteins of the DNA damage response pathways was also indicative of DNA damage. As will be described below, both p53 and p21CIP1/WAF1 were activated by radiomimetic drugs during mitotic block (Figure 2).

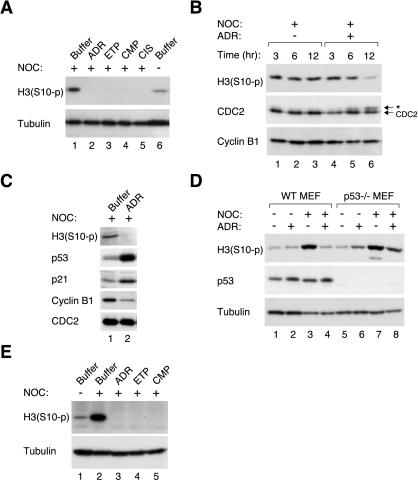

Figure 2.

DNA damage during mitotic block inhibits histone H3 phosphorylation in established cell lines and primary cells and is not affected by the status of p53 and pRb. (A) HeLa cells were blocked in mitosis with NOC for 16 h before the indicated drugs were applied for another 16 h. Cell extracts were prepared and Ser10-phosphorylated histone H3 was detected by immunoblotting. Extracts from cells without receiving treatment was loaded in lane 6. Uniform loading of lysates was confirmed by immunoblotting for tubulin. (B) HeLa cells were blocked with NOC for 16 h before either buffer or ADR was applied. Cell extracts were prepared at the indicated time points, and phosphorylated histone H3, CDC2, and cyclin B1 were detected by immunoblotting. The asterisk indicates the position of the slower migrating form of CDC2. (C) HepG2 cells were blocked with NOC for 16 h before either buffer or ADR was applied for another 16 h. Cell extracts were prepared, and Ser10-phosphorylated histone H3, p53, p21CIP1/WAF1, cyclin B1, and CDC2 were detected by immunoblotting. (D) Wild-type MEFs or p53–/– MEFs were treated with either buffer or NOC for 16 h before ADR was applied for another 16 h as indicated. Cell extracts were prepared, and Ser10-phosphorylated histone H3 and p53 were detected by immunoblotting. Uniform loading of lysates was confirmed by immunoblotting for tubulin. (E) Normal diploid human fibroblasts were treated with either buffer or NOC for 16 h before the indicated DNA-damaging drugs were applied for another 16 h. Cell-free extracts were prepared and Ser10-phosphorylated histone H3 was detected by immunoblotting. Uniform loading of lysates was confirmed by immunoblotting for tubulin.

Together, these data indicate that Topo inhibitors could generate DNA damage even when chromosomes were highly condensed during the spindle-assembly checkpoint.

DNA Damage Inhibits Mitotic Histone H3 Phosphorylation

As expected, phosphorylation of histone H3 at Ser10 (which usually begins before prophase and is required for chromosome condensation; Hendzel et al., 1997) increased after addition of NOC (Figure 2A, lanes 1 and 6). While still in the presence of NOC, treatment with DNA-damaging drugs abolished histone H3 phosphorylation. This effect was not limited to a particular type of drug because poisons of Topo I (CMP), Topo II (ADR and ETP), or non-Topo inhibitors (CIS) were equally effective. Figure 2B shows that histone H3 phosphorylation was reduced to background level at 12 h. In contrast, histone H3 phosphorylation remained elevated in the absence of ADR for the duration of the experiment.

The loss of histone H3 phosphorylation after DNA damage in mitotic cells was not limited to a specific cell type. HeLa cells lack functional p53 and pRb due to the presence of HPV E6 and E7 (Scheffner et al., 1991). Treatment of NOC-blocked HepG2 cells (containing functional p53 and pRb) with ADR likewise abolished histone H3 phosphorylation (Figure 2C). Both p53 and its downstream target p21CIP1/WAF1 accumulated after HepG2 cells were treated with ADR. Unlike HeLa cells (Figure 2B), cyclin B1 level in HepG2 was reduced after DNA damage (Figure 2C). The decrease of cyclin B1 was probably due to the repression of the cyclin B1 promoter by p53 (Innocente et al., 1999; Passalaris et al., 1999), rather than due to the activation of proteolytic pathway (see below).

To evaluate whether p53 is required for the mitotic DNA damage responses, wild-type or p53–/– MEFs were pretreated with NOC before addition of ADR. Figure 2D shows that histone H3 phosphorylation was repressed in both wild-type and p53–/– MEFs by ADR, suggesting that p53 was not required for mitotic DNA damage responses. Nevertheless, ADR was less effective in the p53–/– than in the wild-type background, suggesting that p53 may contribute to the responses. We next examined whether normal cell strains, instead of established cell lines, also responded to DNA damage during mitotic block. Figure 2E shows that as in the cell lines, histone H3 phosphorylation in human diploid fibroblasts was stimulated by NOC and was abolished by subsequent treatment with DNA-damaging agents.

Together, these data show that treatment of NOC-blocked cells with DNA-damaging agents decreased histone H3 phosphorylation in a variety of cell types.

DNA Damage Triggers Inhibitory Phosphorylation of CDC2 during Spindle-Assembly Checkpoint

During NOC-imposed spindle checkpoint, CDC2 was present exclusively in the faster mobility, activated state. Figure 2B and Figure 3A show that DNA damage of NOC-blocked cells induced gel mobility shifts of CDC2, which represent phosphorylation of Thr14 and Tyr15 (Poon et al., 1997). Phosphorylation of CDC2 mirrored the loss of histone H3 phosphorylation temporally (Figure 2B). Immunoblotting with a phospho-Tyr15–specific antibody confirmed that CDC2 was phosphorylated on Tyr15 after DNA damage (Figure 3A).

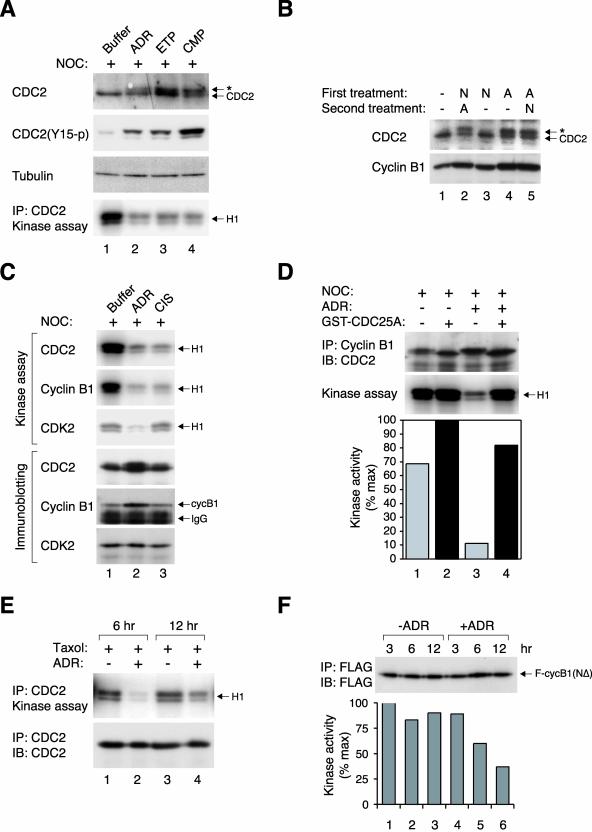

Figure 3.

DNA damage during mitotic block inactivates cyclin-CDC2. (A) HeLa cells were blocked in mitosis with NOC for 16 h before the indicated drugs were applied for another 16 h. Cell extracts were prepared and were subjected to immunoblotting for total CDC2 or the Tyr15-phosphorylated form of the protein. The asterisk indicates the position of the slower migrating form of CDC2. Uniform loading of lysates was confirmed by immunoblotting for tubulin. CDC2 was immunoprecipitated from the same samples and the associated histone H1 kinase activities were measured as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. (B) HeLa cells were treated with buffer, NOC (N), or ADR (A) for 16 h, followed by a second 16-h treatment as indicated. Cell extracts were prepared and CDC2 and cyclin B1 were detected by immunoblotting. The position of the slower-migrating form of CDC2 is indicated by the asterisk. (C) HeLa cells were blocked in mitosis with NOC for 16 h before the indicated drugs were applied for another 16 h. The histone H1 kinase activities associated with immunoprecipitates of CDC2, cyclin B1, or CDK2 were assayed. The level of proteins in the immunoprecipitates was confirmed by immunoblotting as indicated. (D) HeLa cells were blocked with NOC for 16 h before buffer or ADR was applied for another 12 h. Cell extracts were prepared and immunoprecipitated with antibodies against cyclin B1. The immunoprecipitates were incubated with either purified GST or GST-CDC25A. After washing out the recombinant proteins, the histone H1 kinase activities were assayed. Phosphorylation was detected and quantified with a PhosphorImager. CDC2 in the immunoprecipitates was detected by immunoblotting. (E) HeLa cells were incubated with Taxol for 16 h before by either buffer or ADR was applied. Cell extracts were prepared after 6 or 12 h, and the histone H1 kinase activities associated with CDC2-immunoprecipitates were assayed. The CDC2 in the immunoprecipitates was detected by immunoblotting. (F) HeLa cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-cyclin B1(NΔ88). After 24 h, the cells were either mock treated or treated with ADR, and cell extracts were prepared at the indicated time points. Histone H1 kinase activities associated with the FLAG-immunoprecipitates were assayed and quantified with a PhosphorImager. The presence of FLAG-cyclin B1(NΔ88) in the immunoprecipitates was detected by immunoblotting.

The dominance of DNA damage over the spindle-assembly checkpoint on CDC2 activity was further examined by reversing the order of the treatments. Figure 3B shows that although ADR triggered CDC2 phosphorylation in cells pretreated with NOC, NOC had no effect on CDC2 in cells pretreated with ADR.

Importantly, cyclin B1 (which accumulated during mitotic block) was not degraded after DNA damage (Figures 2B and 3C). Despite the sustained level of cyclin B1 and CDC2, their associated kinase activities were inactivated after DNA damage (Figure 3, A and C). For comparison, the kinase activity of CDK2 remained at background level during mitotic block and DNA damage (Figure 3C). These data indicate that DNA damage during mitotic block inactivated cyclin B1–CDC2 complexes by promoting inhibitory phosphorylation of CDC2. To further corroborate this idea, the kinase activity of cyclin B1–CDC2 complexes isolated from DNA-damaged mitotic cells was restored by treatment with recombinant CDC25A (Figure 3D).

To exclude the possibility that the effects of DNA damage on mitotic cells were specific to NOC, the spindle-assembly checkpoint was activated instead with Taxol (disrupted microtubule disassembly). Similar to NOC treatment, CDC2 was inactivated when ADR was applied to Taxol-blocked cells (Figure 3E). Instead of using drugs, cells were also trapped in mitosis by expression of an indestructible cyclin B1 (Wheatley et al., 1997). Figure 3F shows that treatment of cells expressing FLAG-cyclin B1(NΔ88) with ADR decreased the kinase activities associated with the FLAG-tagged cyclin. As with the endogenous cyclin B1, the decrease in kinase activity of the indestructible mutant was not due to the disappearance of the protein. The loss of kinase activity of cyclin B1(NΔ88) after DNA damage was not as impressive as the endogenous cyclin B1, probably reflecting the fact that the recombinant protein was ectopically expressed.

Together, these data indicate that DNA damage during the spindle checkpoint induces inhibitory phosphorylation of CDC2 and inactivation of cyclin B1–CDC2. Importantly, the presence of high level of cyclin B1 in the damaged cells (Figure 2B) indicates that the loss of CDC2 activity was not simply due to cells adapting to the spindle checkpoint and escaping into G1 (Cross et al., 1995; Minn et al., 1996; Di Leonardo et al., 1997; Lanni and Jacks, 1998; Notterman et al., 1998).

DNA Damage during Spindle Checkpoint Induces Chromosome Decondensation without G1 Entry

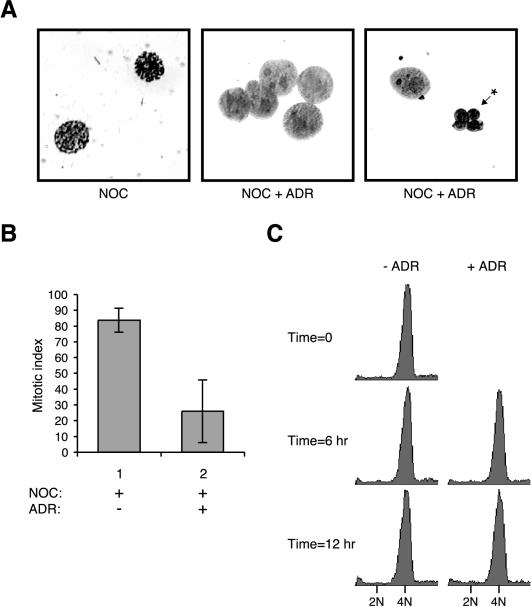

We found that chromosomes were condensed in cells treated with NOC but were decondensed in cells that received additional treatment of DNA-damaging agents (Figure 4A). The percentage of cells that contained mitotic figures was significantly reduced after 6-h incubation in ADR (Figure 4B). One possible explanation of the decondensed chromosomes is that the cells had exited mitosis and divided into daughter cells. However, flow cytometry analysis indicated that the cells treated with ADR stayed with a 4N DNA content (Figure 4C), indicating that they had not undergone cytokinesis. Longer treatment with ADR reduced the mitotic index further, but the concomitant increase in apoptotic cells caused by prolong incubation in NOC (Figure 4A), and the possibility of adaptation from the spindle checkpoint could compromise our interpretation. By 12 h after ADR treatment, the percentage of apoptotic figures was as high as 20% in some experiments.

Figure 4.

DNA damage during mitotic block induces chromosome decondensation. (A) HeLa cells were blocked with NOC for 16 h before either buffer or ADR was applied for another 6 h. The cells were fixed and stained as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Representational images of mitotic figures in NOC-treated cells, and decondensed nuclei in cells treated with both NOC and ADR are shown. The asterisk indicates a typical fragmented cell found after prolong incubation with NOC. (B) Cells were treated as described in A, and the number of mitotic cells was scored. The average of three independent experiments and their standard deviations are shown. (C) HeLa cells were blocked with NOC for 16 h before either buffer or ADR was applied. At the indicated time points, cell cycle distribution was analyzed by flow cytometry.

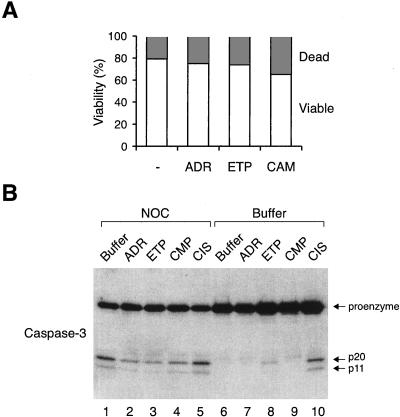

For 6 h after ADR addition, the sub-G1 population was not substantially increased in both damaged and control cells (Figure 4C), suggesting that there was no significant increase in apoptosis after DNA damage at that stage. Moreover, trypan blue exclusion analysis indicated that DNA damage did not substantially decrease viability of NOC-blocked cells (Figure 5A). Likewise, although NOC alone promoted certain degree of caspase-3 cleavage, addition of DNA-damaging drugs did not further enhance cleavage (Figure 5B). These results show that DNA damage during mitotic block induced chromosome decondensation, and at least for a relatively short time (up to 6 h) after DNA damage, the loss of mitotic figures was not due to massive cell death or exit into G1.

Figure 5.

DNA damage during mitotic block does not induce apoptotic cell death. (A) HeLa cells blocked with NOC for 16 h before ADR, ETP, or CMP was applied for another 12 h. Viability was measured by trypan blue exclusion analysis. (B) HeLa cells were treated with either buffer or NOC for 16 h before the indicated DNA-damaging drugs were applied for 12 h. Cell extracts were prepared and caspase-3 was detected by immunoblotting. The positions of the caspase-3 proenzyme and the two cleavage products are indicated.

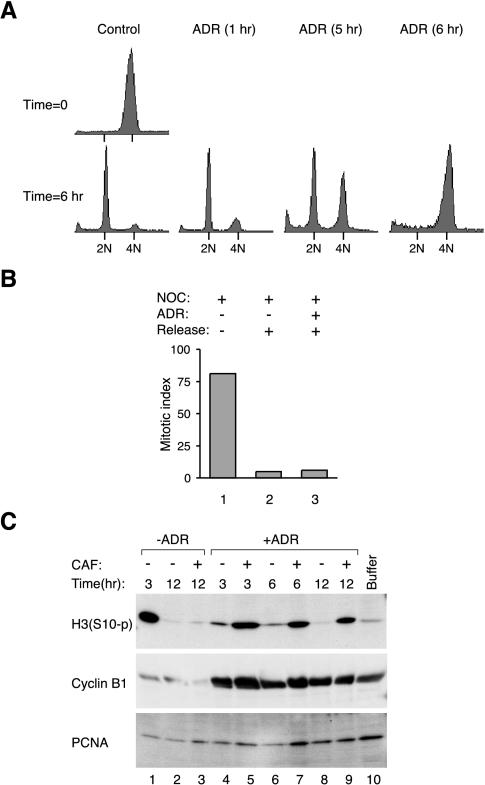

To circumvent the toxic effects of prolong NOC treatment, we next examined whether cells that received DNA damage during mitotic block could resume cell cycle progression once the mitotic block was removed. Cells blocked in prometaphase by NOC (with 4N DNA) were completely in G1 (with 2N DNA) at 6 h after release from the block (Figure 6A). However, cells failed to enter G1 when they were treated with ADR for 6 h before the release. The inhibition of G1 entry became progressively less effective with shorter ADR treatments. Figure 6B verifies that irrespective of whether cells received DNA damage, chromosome decondensation occurred when NOC was removed. Figure 6C shows that cyclin B1 was destroyed and histone H3 was dephosphorylated as cells were released from mitotic block into G1 (lanes 1 and 2). In contrast, cyclin B1 remained at high level when DNA damage was inflicted during the mitotic block (lanes 4–9). This datum clearly shows the difference of cyclin B1 level between cells in G1 and cells that received damage during spindle checkpoint. Although cyclin B1 was not destroyed after NOC and ADR were washed out, histone H3 was still dephosphorylated (lanes 4, 6, and 8). Because this occurred in the absence of NOC, this indicates that the loss of histone H3 phosphorylation was not merely due to the toxic effects of NOC. These findings further support the idea that the loss of histone H3 phosphorylation in cells damaged during spindle checkpoint was not simply due to an adaptation into a G1-like state. Interestingly, the loss of histone H3 phosphorylation after DNA damage was reversed by caffeine, implicating a role for ATM/ATR (see below).

Figure 6.

DNA damage during mitotic block prevents G1 entry. (A) HeLa cells were incubated with NOC for 16 h before buffer or ADR was added. ADR was left for 1, 5, or 6 h before the cells were washed and released into growth media without NOC or ADR. Cells were harvested immediately (time 0) or 6 h later and the DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) HeLa cells were pretreated with NOC for 16 h before buffer or ADR was applied for another 6 h. Cells were either left in NOC (lane 1) or released into normal growth media (lanes 2 and 3) for 6 h. The cells were fixed, stained, and the mitotic index was measured. (C) HeLa cells were pretreated with NOC for 16 h before buffer (lanes 1–3) or ADR (lanes 4–9) was applied for another 6 h. Cells were released into normal growth media in the presence or absence of caffeine as indicated. Cell extracts were prepared at the indicated time points and subjected to immunoblotting for Ser10-phosphorylated histone H3 and cyclin B1. Extracts from control cells were loaded in lane 10 and uniform loading of lysates was confirmed by immunoblotting for PCNA.

DNA Damage during Mitotic Block Induces Accumulation of Cyclin A

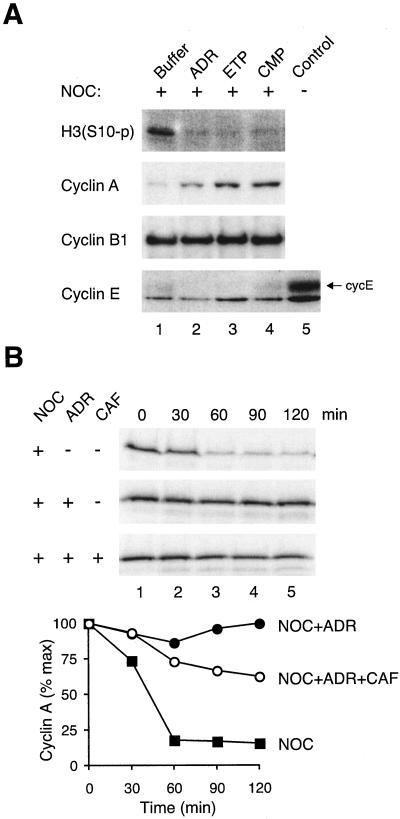

We and others have shown that cyclin A is usually destroyed before cyclin B1 in the cell cycle. Unlike cyclin B1, cyclin A is degraded during NOC-induced spindle-assembly checkpoint (reviewed in Yam et al., 2002). Surprisingly, DNA damage of NOC-blocked cells resulted in an accumulation of cyclin A (Figure 7A). In contrast, cyclin B1 was constant and cyclin E remained at background level.

Figure 7.

Cyclin A is stabilized after DNA damage of mitotic blocked cells. (A) HeLa cells were blocked with NOC for 16 h before the indicated DNA-damaging drugs were applied for 16 h. Cell extracts were prepared and Ser10-phosphorylated histone H3, cyclin A, cyclin B1, and cyclin E were detected by immunoblotting. Lane 5 was from control growing cells to indicate the position and level of cyclin E. (B) HeLa cells blocked with NOC for 16 h before treated with buffer, ADR, or ADR and caffeine together. Cell extracts were prepared 12 h later and used for in vitro degradation assay by using radiolabeled cyclin A as a substrate. Samples were collected at the indicated time points and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and phosphorimagery.

To further investigate whether cyclin A was stabilized after DNA damage, an in vitro degradation assay was performed with recombinant cyclin A and extracts prepared from drug-treated cells (Figure 7B). As we have shown previously (Yam et al., 2000), cyclin A was efficiently destroyed in extracts derived from NOC-blocked cells. Significantly, destruction of cyclin A was inhibited in extracts pretreated with NOC followed by ADR (Figure 7B).

In summary, DNA damage inflicted during spindle checkpoint induced chromosome decondensation with a 4N DNA content. Both cyclin A and inactive cyclin B1–CDC2 accumulated as in the G2 DNA damage checkpoint.

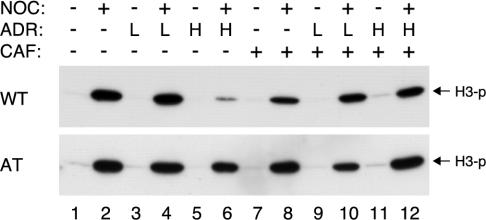

DNA Damage Responses during Spindle-Assembly Checkpoint Are ATM Dependent

Interestingly, when caffeine was applied at the same time as ADR in the above described in vitro destruction assay, degradation of cyclin A was slightly accelerated compared with the reaction without caffeine (Figure 7B). Moreover, caffeine inhibited the decrease of histone H3 phosphorylation in cells treated with NOC and ADR (Figure 6C). These data suggest that ATM or ATR may be involved in the DNA damage responses during the spindle checkpoint. We tested this hypothesis by comparing the DNA damage responses in age-matched lymphoblastoid cells derived from AT or normal individuals (Figure 8). As expected, histone H3 phosphorylation accumulated during NOC-induced spindle checkpoint in normal and ATM–/– lymphoblastoid cells (lane 2). As with other cells tested herein, ADR decreased histone H3 phosphorylation in wild-type lymphoblastoid cells (lane 6) (but not with a lower dose of ADR, lane 4). Significantly, the same treatment only slightly decreased histone H3 phosphorylation in ATM–/– cells. Furthermore, the decrease of histone H3 phosphorylation in normal lymphoblastoid cells was abolished by caffeine (lane 12). The results from caffeine treatment and from ATM–/– cells both point to the idea that ATM is required for the loss of histone H3 phosphorylation when mitotic cells were treated with ADR.

Figure 8.

Decrease of histone H3 phosphorylation after DNA damage in mitotic cells is ATM-dependent. Wild-type (WT) or ATM–/– lymphoblastoid cells were treated with buffer or NOC for 16 h. Two doses of ADR, L (0.02 μg/ml) and H (0.2 μg/ml), were applied in the presence or absence of caffeine for 12 h as indicated. Cell extracts were prepared and Ser10-phosphorylated histone H3 was detected by immunoblotting. Uniform loading of lysates was confirmed by protein staining (our unpublished data).

The Mitotic DNA Damage Responses Involve Destruction of CDC25A

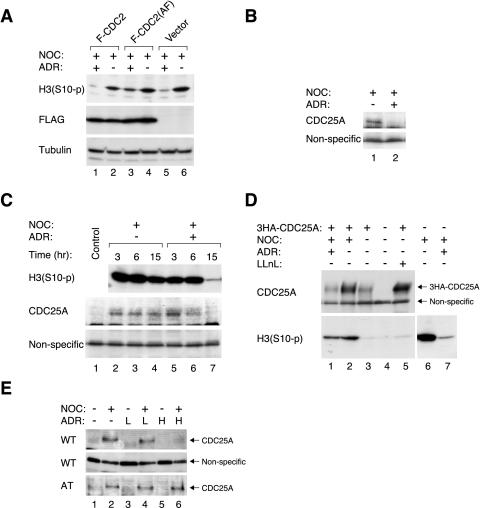

Given the clear correlation between CDC2 Thr14/Tyr15 phosphorylation and mitotic DNA damage responses, we next demonstrated that the damage responses could be disrupted by preventing CDC2 phosphorylation. Figure 9A shows that although expression of wild-type CDC2 has no discernible effect, a nonphosphorylatable mutant (T14A+Y15F) prevented the decrease of histone H3 phosphorylation after DNA damage.

Figure 9.

The involvement of CDC25A destruction in the mitotic DNA damage responses. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with control vector, FLAG-CDC2, or FLAG-CDC2(T14A+Y15F). Cells were immediately treated with NOC for 16 h and followed by either buffer or ADR for 12 h. Cell extracts were prepared and Ser10-phosphorylated histone H3 was detected by immunoblotting. Expression of the recombinant proteins was confirmed by anti-FLAG antibodies. Uniform loading of lysates was confirmed by immunoblotting for tubulin. (B) HeLa cells were pretreated with NOC for 16 h before buffer or ADR was applied for another 12 h. Cell extracts were prepared and CDC25A was detected by immunoblotting. A nonspecific protein recognized by the anti-CDC25A antibodies served as loading control. (C) HeLa cells were pretreated with NOC for 16 h before buffer or ADR was applied for the indicated time. Cell extracts were prepared and Ser10-phosphorylated histone H3 and CDC25A were detected by immunoblotting. A nonspecific protein recognized by the anti-CDC25A antibodies served as loading control. (D) HeLa cells were transfected with control vector or 3HA-CDC25A. Cells were immediately treated with buffer or NOC for 16 h followed by either buffer or ADR for 12 h. Cell extracts were prepared and CDC25A and Ser10-phosphorylated histone H3 were detected by immunoblotting. The nonspecific protein recognized by the anti-CDC25A antibodies served as loading control. Proteasome inhibitor LLnL was applied to cells in lane 5 to stabilize the 3HA-CDC25A to serve as a control for blotting. (E) Wild-type or ATM–/– lymphoblastoid cells were treated with buffer or NOC for 16 h, followed by 0.02 μg/ml (L) or 0.2 μg/ml (H) of ADR for 12 h as indicated. Cell extracts were prepared and CDC25A was detected by immunoblotting. Uniform loading of wild-type lysates was confirmed by a nonspecific protein recognized by the anti-CDC25A antibodies.

For a protein to be a potential regulator of the mitotic DNA damage responses, the level or activity of the protein should be modulated at the same time or before histone H3 dephosphorylation and CDC2 inactivation. Stronger evidence is suggested if the modifications are irreversible and are not indirectly caused by the inactivation of CDC2. We found that several CDC2 regulators (MYT1, WEE1, and CDC25C) were posttranslationally modified when mitotic cells were treated with DNA-damaging agents (our unpublished data). However, it is not possible to evaluate conclusively whether these were the cause or consequence of CDC2 inactivation because most CDC2 regulators are modified by positive and negative feedback controls (Morgan, 1997).

An important player for the mitotic DNA damage responses may be CDC25A. The first indication came from the observation that proteasome inhibitors abolished the decrease of histone H3 phosphorylation when ADR was applied to NOC-blocked cells (our unpublished data), suggesting that a critical regulator of the mitotic DNA damage responses may be regulated by proteolysis. We found that addition of ADR to NOC-blocked cells promoted the destruction of CDC25A (Figure 9B). Destruction of CDC25A after ADR treatment was rapid, occurring at similar kinetics as histone H3 dephosphorylation (Figure 9C) and CDC2 phosphorylation (Figure 2B).

To demonstrate directly that CDC25A is involved in the mitotic DNA damage responses, recombinant CDC25A was overexpressed in cells followed by treatment with NOC and ADR (Figure 9D). As with the endogenous protein, pretreatment with NOC stabilized the recombinant CDC25A (lane 2) and addition of ADR reduced the CDC25A level (lane 1) (although reduced by NOC treatment, the level of recombinant CDC25A was still much higher than the endogenous protein). Significantly, the loss of histone H3 phosphorylation after DNA damage was inhibited by CDC25A. Experiments with control vector did not rescue the histone H3 phosphorylation (lanes 6 and 7). Similar results were obtained with a more stable N-terminally truncated version of CDC25A (our unpublished data).

Given that the decrease in histone H3 phosphorylation after DNA damage was defective in ATM–/– lymphoblastoid cells (Figure 8), we next investigated whether the degradation of CDC25A was also compromised in the absence of ATM. As expected, endogenous CDC25A accumulated during mitotic block in both wild-type and ATM–/– lymphoblastoid cells (Figure 9E). Addition of ADR to wild-type lymphoblastoid cells triggered the destruction of CDC25A. In mark contrast, CDC25A was not destroyed after ADR treatment in ATM–/– lymphoblastoid cells.

Together, these data indicate that ATM-dependent degradation of CDC25A correlated with the mitotic DNA damage responses. Ectopic expression of CDC25A or nonphosphorylatable mutant of CDC2 disrupted the mitotic DNA damage responses. Destruction of CDC25A may remove the dephosphorylation activity toward Thr14 and Tyr15 of CDC2.

DISCUSSION

Mitosis occupies a relatively short period within the normal mammalian cell cycle. However, individual cells may contain lagging chromosomes that require substantial amount of time for the spindles to find all kinetochores (thus the importance of the spindle-assembly checkpoint). This period provides opportunities for DNA damage. Moreover, both spindle-disrupting drugs and Topo poisons are being used extensively as chemotherapeutic agents (often in combination); it is thus important to understand the DNA damage responses during spindle-assembly checkpoint.

It is puzzling that drugs such as the Topo inhibitors could cause DNA damage when the chromosomes were highly condensed. Based on single cell eletrophoresis assay, increase in histone H2AX phosphorylation, and activation of checkpoint proteins (p53, and p21CIP1/WAF1), we demonstrated that DNA could be damaged during the spindle-assembly checkpoint. The presence of DNA breaks was not simply due to DNA fragmentation-associated apoptosis, because there was neither an increase in sub-G1 DNA (Figure 4) nor caspase-3 cleavage (Figure 5). Herein, we detected H2AX phosphorylation by immunoblotting (Figure 1). Mikhailov et al. (2002) has also reported an increase in H2AX phosphorylation by immunostainning when ADR was applied to NOC-blocked cells.

We found that DNA damage during spindle checkpoint induced inactivation of CDC2, loss of histone H3 phosphorylation, and chromosome decondensation. This occurred in a variety of primary cells and established cell lines and was independent on p53 and pRb (Figure 2). A conspicuous difference between cells with or without p53, however, is that cyclin B1 was maintained after DNA damage in p53-negative cells but not in p53-containing cells. This is probably due to the repression of the cyclin B1 promoter by p53 (Innocente et al., 1999; Passalaris et al., 1999).

One of our concerns is the relatively harsh treatment the cells received to elicit the DNA damage responses during mitotic block. Complete loss of histone H3 phosphorylation was only achieved after 12 h of incubation with ADR (Figure 2). Together with the previous 16 h of incubation with NOC, cell cycle block was imposed for a relatively long duration. One possible explanation is as follows. In asynchronously growing cells, only a fraction of the cells contains phosphorylated histone H3. The decrease of mitotic index and histone H3 phosphorylation after DNA damage is simply achieved by preventing cells from entering mitosis. In contrast, in cells already completely locked in mitosis with high histone H3 phosphorylation (as in our experiments), the loss of histone H3 phosphorylation after DNA damage requires dephosphorylation histone H3 (as well as stopping its phosphorylation). It is thus expected that the effects of DNA damage on histone H3 phosphorylation in mitotic cells should be relatively slow. We have used shorter treatment of ADR (6 h) to obtain a subsequent loss of histone H3 phosphorylation and cell cycle arrest (Figure 6). Similar results were also obtained when cells were first released from thymidine block into a shorter NOC block (9 h) before ADR was applied for 12 h (our unpublished data). Hence, shorter treatment with both NOC and ADR could also elicit similar DNA damage responses in mitotic cells. Smits et al. (2000) showed that treatment of NOC-blocked U2OS cells with ADR for 1 h inhibits the subsequent mitotic exit when NOC is removed. Conflicting results obtained by Mikhailov et al. (2002) showed that similar treatment does not hinder mitotic exit, but more extensive damage does delay mitotic exit with a MAD2-dependent mechanism. For experiments that allowed cells to exit mitosis (Figure 6), our data are more atoned with that of Mikhailov et al. (2002) because mitotic exit still occurred when cells were treated with ADR for 1 h (at a similar dosage as in other reports). However, we found that more extensive damage (6 h) inhibited mitotic exit. It should be noted that it is not possible to distinguish between cells in G2/M with cells that had undergone nuclear division but not cytokinesis by using the assays described herein. Smits et al. (2000) found that cells that fail to exit mitotic maintain high level of cyclin B1 and MPM2 phosphorylation. We have not examined MPM2 phosphorylation directly, but the loss of histone H3 phosphorylation and inhibition of CDC2 after more extensive damage (6 h) seem to disagree with the MPM2 data.

We found that DNA damage of NOC-blocked cells resulted in chromosome decondensation, dephosphorylation of histone H3, and inhibition of cyclin B1–CDC2 even in the continuous presence of NOC. In comparison, Smits et al. (2000) showed that treatment of NOC-blocked U2OS cells (16 h) with ADR (0.5 mM) for 1 h only marginally inhibits the cyclin B1 activity in the subsequent 10-h incubation in NOC. By following individual cells through mitosis, Mikhailov et al. (2002) showed that DNA damage during unperturbed mitosis does not affect the progression and exit of mitosis. Mikhailov et al. (2002) used pulses of laser light or the Topo II inhibitors ADR or ICRF-193 to induce DNA damage in CFPAC-1, Cos7, CV1, HeLa, hTERT-RPE, PtK1, and U2OS cells after they had become committed to mitosis. In this report, we have not examined the effects of DNA damage on normal mitosis but have placed our emphasis on DNA damage during the spindle-assembly checkpoint. Another major difference between the current study and previous reports is in more extensive DNA damage the cells received. HeLa cells that received the level of DNA damage described in this study will not be able to form colony in clonogenic survival assays (our unpublished data).

Another concern that we have is whether the cells moved to a G1-like or a G2-like state after DNA damage during mitotic block. This issue is significant because some NOC-treated cells are able to adapt to the spindle checkpoint and go into a G1-like state as tetraploids (Cross et al., 1995; Minn et al., 1996; Di Leonardo et al., 1997; Lanni and Jacks, 1998; Notterman et al., 1998). As in normal G1 phase, cyclin B1 is degraded in cells that are adapted to the spindle checkpoint (Lanni and Jacks, 1998; Notterman et al., 1998). Furthermore, adapted cells are able to synthesize DNA in the absence of p53 (Andreassen et al., 2001b). We think that the majority of the cells in this study are not in the adaptive G1-like state because cyclin B1 level remains elevated after DNA damage (Figures 3, B and C, and 6C). Moreover, we did not detect an increase in cyclin E expression (Figure 7) or BrdU incorporation (our unpublished data). Instead, the inactivation of cyclin B1-CDC2 by Thr14/Tyr15 phosphorylation and the stabilization of cyclin A (which usually accumulates during G2) (Figure 7) suggest a G2-like cell cycle arrest after DNA damage.

We found that both cyclin A and cyclin B1 are stabilized after DNA damage in NOC-blocked cells. This may have similarities to the mitotic DNA damage responses in other organisms. In cells of the Drosophila gastrula, cyclin A is stabilized during the DNA damage-induced delay in metaphase-anaphase transition (Su and Jaklevic, 2001). In budding yeast, destruction of Pds1p is normally required for relief the inhibition on APC/C, allowing entry into anaphase and mitotic exit. DNA damage induces mitotic arrest and inhibition of cyclin destruction by stabilization of Pds1p (Tinker-Kulberg and Morgan, 1999).

Regulation of G2-M comprises of a series of positive and negative feedback loops, making it difficult to untangle the cause and effects. Using caffeine to bypass the checkpoint and butyrolactone-I to inhibit the CDC2, our previous data implicated the phosphatases (CDC25), rather than the kinases (WEE1/MYT1), as the principal regulator of CDC2 after DNA damage (Poon et al., 1997). CDC25A is an attractive target of the mitotic damage response described herein because CDC25A accumulates during mitosis (Mailand et al., 2002) and has been implicated to play a role in DNA damage responses to UV and ionizing radiation (Mailand et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2002). We found that the mitotic damage response is sensitive to caffeine (Figures 6 and 7) and is dependent on ATM (Figure 8). This is in line with the idea that the stability of CDC25A is regulated by the ATM-CHK1 pathway (Shimuta et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2002). Furthermore, we found that mitotic CDC25A was degraded after DNA damage in wild-type but not ATM–/– lymphoblastoid cells (Figure 9).

It is conceivable that rapid destruction of CDC25A after DNA damage could represent a driving force behind the mitotic exit. Forced expression of nonphosphorylatable CDC2 or CDC25A (full length or NΔ) could disrupt the mitotic damage responses (Figure 9). We hypothesize that during spindle-assembly checkpoint, extensive DNA damage promotes CDC25A degradation, resulting in the inactivation of cyclin B1–CDC2, histone H3 dephosphorylation, decondensation of chromosomes, and accumulation of cyclin A. These events resemble a reversal into G2 phase and an activation of the G2 damage checkpoint. Stepping back to G2 and decondensing the chromosomes may allow a cell to repair its DNA before it is irreversibly divided into daughter cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Junjie Chen, Julian Gannon, Tim Hunt, Emma Lees, Hiroto Okayama, and Richard Woo for generous gifts of reagents. Many thanks to members of the Poon laboratory for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the Philip Morris External Research Program and the Research Grants Council grant HKUST6129/02M to R.Y.C.P. C.P.N is a recipient of the Lady Tata Memorial Trust for Leukemia Research Fellowship. R.Y.C.P. is a recipient of the Croucher Foundation Senior Fellowship Award.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E03–03–0168. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E03-03-0168.

Abbreviations used: ADR, adriamycin; AT, ataxia-telangiectasia; CMP, camptothecin; CIS, cisplatin; ETP, etoposide; NOC, nocodazole; Topo, topoisomerase.

References

- Agami, R., and Bernards, R. (2000). Distinct initiation and maintenance mechanisms cooperate to induce G1 cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage. Cell 102, 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen, P.R., Lacroix, F.B., Lohez, O.D., and Margolis, R.L. (2001a). Neither p21WAF1 nor 14–3-3sigma prevents G2 progression to mitotic catastrophe in human colon carcinoma cells after DNA damage, but p21WAF1 induces stable G1 arrest in resulting tetraploid cells. Cancer Res. 61, 7660–7668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen, P.R., Lohez, O.D., Lacroix, F.B., and Margolis, R.L. (2001b). Tetraploid state induces p53-dependent arrest of nontransformed mammalian cells in G1. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 1315–1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasina, A., de Weyer, I.V., Laus, M.C., Luyten, W.H., Parker, A.E., and McGowan, C.H. (1999). A human homologue of the checkpoint kinase Cds1 directly inhibits Cdc25 phosphatase. Curr. Biol. 9, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunz, F., Dutriaux, A., Lengauer, C., Waldman, T., Zhou, S., Brown, J.P., Sedivy, J.M., Kinzler, K.W., and Vogelstein, B. (1998). Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science 282, 1497–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, T.A., Hermeking, H., Lengauer, C., Kinzler, K.W., and Vogelstein, B. (1999). 14–3-3Sigma is required to prevent mitotic catastrophe after DNA damage. Nature 401, 616–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chehab, N.H., Malikzay, A., Appel, M., and Halazonetis, T.D. (2000). Chk2/hCds1 functions as a DNA damage checkpoint in G(1) by stabilizing p53. Genes Dev. 14, 278–288. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross, S.M., Sanchez, C.A., Morgan, C.A., Schimke, M.K., Ramel, S., Idzerda, R.L., Raskind, W.H., and Reid, B.J. (1995). A p53-dependent mouse spindle checkpoint. Science 267, 1353–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Leonardo, A., Khan, S.H., Linke, S.P., Greco, V., Seidita, G., and Wahl, G.M. (1997). DNA rereplication in the presence of mitotic spindle inhibitors in human and mouse fibroblasts lacking either p53 or pRb function. Cancer Res. 57, 1013–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falck, J., Mailand, N., Syljuasen, R.G., Bartek, J., and Lukas, J. (2001). The ATM-Chk2-Cdc25A checkpoint pathway guards against radioresistant DNA synthesis. Nature 410, 842–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung, T.K., Siu, W.Y., Yam, C.H., Lau, A., and Poon, R.Y.C. (2002). Cyclin F is degraded during G2-M by mechanisms fundamentally different from other cyclins. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35140–35149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendzel, M.J., Wei, Y., Mancini, M.A., Van Hooser, A., Ranalli, T., Brinkley, B.R., Bazett-Jones, D.P., and Allis, C.D. (1997). Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of histone H3 initiates primarily within pericentromeric heterochromatin during G2 and spreads in an ordered fashion coincident with mitotic chromosome condensation. Chromosoma 106, 348–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirao, A., Kong, Y.Y., Matsuoka, S., Wakeham, A., Ruland, J., Yoshida, H., Liu, D., Elledge, S.J., and Mak, T.W. (2000). DNA damage-induced activation of p53 by the checkpoint kinase Chk2. Science 287, 1824–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocente, S.A., Abrahamson, J.L., Cogswell, J.P., and Lee, J.M. (1999). p53 regulates a G2 checkpoint through cyclin B1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 2147–2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito, M., Yoshioka, K., Akechi, M., Yamashita, S., Takamatsu, N., Sugiyama, K., Hibi, M., Nakabeppu, Y., Shiba, T., and Yamamoto, K.I. (1999). JSAP1, a novel jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK)-binding protein that functions as a Scaffold factor in the JNK signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 7539–7548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, P., Gu, Y., and Morgan, D.O. (1996). Role of inhibitory CDC2 phosphorylation in radiation-induced G2 arrest in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 134, 963–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanni, J.S., and Jacks, T. (1998). Characterization of the p53-dependent postmitotic checkpoint following spindle disruption. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 1055–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levedakou, E.N., Kaufmann, W.K., Alcorta, D.A., Galloway, D.A., and Paules, R.S. (1995). p21CIP1 is not required for the early G2 checkpoint response to ionizing radiation. Cancer Res. 55, 2500–2502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.K.W., Ng, I.O.L., Fan, S.T., Albrecht, J.H., Yamashita, K., and Poon, R.Y.C. (2002). Activation of cyclin-dependent kinases CDC2 and CDK2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver 22, 259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Girona, A., Kanoh, J., and Russell, P. (2001). Nuclear exclusion of Cdc25 is not required for the DNA damage checkpoint in fission yeast. Curr. Biol. 11, 50–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailand, N., Falck, J., Lukas, C., Syljuasen, R.G., Welcker, M., Bartek, J., and Lukas, J. (2000). Rapid destruction of human Cdc25A in response to DNA damage. Science 288, 1425–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mailand, N., Podtelejnikov, A.V., Groth, A., Mann, M., Bartek, J., and Lukas, J. (2002). Regulation of G(2)/M events by Cdc25A through phosphorylation-dependent modulation of its stability. EMBO J. 21, 5911–5920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikhailov, A., Cole, R.W., and Rieder, C.L. (2002). DNA damage during mitosis in human cells delays the metaphase/anaphase transition via the spindle-assembly checkpoint. Curr. Biol. 12, 1797–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millband, D.N., Campbell, L., and Hardwick, K.G. (2002). The awesome power of multiple model systems: interpreting the complex nature of spindle checkpoint signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 12, 205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minn, A.J., Boise, L.H., and Thompson, C.B. (1996). Expression of Bcl-xL and loss of p53 can cooperate to overcome a cell cycle checkpoint induced by mitotic spindle damage. Genes Dev. 10, 2621–2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyakawa, Y., and Matsushime, H. (2001). Rapid downregulation of cyclin D1 mRNA and protein levels by ultraviolet irradiation in murine macrophage cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 284, 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D.O. (1997). Cyclin-dependent kinases: engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13, 261–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa, H., Yamamura, K., and Miyazaki, J. (1991). Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 108, 193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notterman, D., Young, S., Wainger, B., and Levine, A.J. (1998). Prevention of mammalian DNA reduplication, following the release from the mitotic spindle checkpoint, requires p53 protein, but not p53-mediated transcriptional activity. Oncogene 17, 2743–2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passalaris, T.M., Benanti, J.A., Gewin, L., Kiyono, T., and Galloway, D.A. (1999). The G(2) checkpoint is maintained by redundant pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 5872–5881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon, R.Y.C. (2002). Cell cycle control. In: Encyclopedia of Cancer, ed. J.R. Bertino, San Diego: Academic Press, 393–404.

- Poon, R.Y.C., Chau, M.S., Yamashita, K., and Hunter, T. (1997). The role of Cdc2 feedback loop control in the DNA damage checkpoint in mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 57, 5168–5178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon, R.Y.C., and Hunter, T. (1995). Dephosphorylation of Cdk2 Thr160 by the cyclin-dependent kinase-interacting phosphatase KAP in the absence of cyclin. Science 270, 90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon, R.Y.C., Jiang, W., Toyoshima, H., and Hunter, T. (1996). Cyclin-dependent kinases are inactivated by a combination of p21 and Thr-14/Tyr-15 phosphorylation after UV-induced DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 13283–13291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon, R.Y.C., Toyoshima, H., and Hunter, T. (1995). Redistribution of the CDK inhibitor p27 between different cyclin. CDK complexes in the mouse fibroblast cell cycle and in cells arrested with lovastatin or ultraviolet irradiation. Mol. Biol. Cell 6, 1197–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon, R.Y.C., Yamashita, K., Adamczewski, J.P., Hunt, T., and Shuttleworth, J. (1993). The cdc2-related protein p40MO15 is the catalytic subunit of a protein kinase that can activate p33cdk2 and p34cdc2. EMBO J. 12, 3123–3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon, R.Y.C., Yamashita, K., Howell, M., Ershler, M.A., Belyavsky, A., and Hunt, T. (1994). Cell cycle regulation of the p34cdc2/p33cdk2-activating kinase p40MO15. J. Cell Sci. 107, 2789–2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prives, C. (1998). Signaling to p53: breaking the MDM2–p53 circuit. Cell 95, 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogakou, E.P., Pilch, D.R., Orr, A.H., Ivanova, V.S., and Bonner, W.M. (1998). DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 5858–5868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffner, M., Munger, K., Byrne, J.C., and Howley, P.M. (1991). The state of the p53 and retinoblastoma genes in human cervical carcinoma cell lines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 5523–5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh, S.Y., Ahn, J., Tamai, K., Taya, Y., and Prives, C. (2000). The human homologs of checkpoint kinases Chk1 and Cds1 (Chk2) phosphorylate p53 at multiple DNA damage-inducible sites. Genes Dev. 14, 289–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimuta, K., Nakajo, N., Uto, K., Hayano, Y., Okazaki, K., and Sagata, N. (2002). Chk1 is activated transiently and targets Cdc25A for degradation at the Xenopus midblastula transition. EMBO J. 21, 3694–3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.P., McCoy, M.T., Tice, R.R., and Schneider, E.L. (1988). A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage in individual cells. Exp. Cell Res. 175, 184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu, W.Y., Arooz, T., and Poon, R.Y.C. (1999). Differential responses of proliferating versus quiescent cells to adriamycin. Exp. Cell Res. 250, 131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits, V.A., Klompmaker, R., Arnaud, L., Rijksen, G., Nigg, E.A., and Medema, R.H. (2000). Polo-like kinase-1 is a target of the DNA damage checkpoint. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, T.T., and Jaklevic, B. (2001). DNA damage leads to a cyclin A-dependent delay in metaphase-anaphase transition in the Drosophila gastrula. Curr. Biol. 11, 8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, W.R., and Stark, G.R. (2001). Regulation of the G2/M transition by p53. Oncogene 20, 1803–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinker-Kulberg, R.L., and Morgan, D.O. (1999). Pds1 and Esp1 control both anaphase and mitotic exit in normal cells and after DNA damage. Genes Dev. 13, 1936–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vugt, M.A., Smits, V.A., Klompmaker, R., and Medema, R.H. (2001). Inhibition of Polo-like kinase-1 by DNA damage occurs in an ATM- or ATR-dependent fashion. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41656–41660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X., Arooz, T., Siu, W.Y., Chiu, C.H., Lau, A., Yamashita, K., and Poon, R.Y.C. (2001). MDM2 and MDMX can interact differently with ARF and members of the p53 family. FEBS Lett. 490, 202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, S.P., Hinchcliffe, E.H., Glotzer, M., Hyman, A.A., Sluder, G., and Wang, Y. (1997). CDK1 inactivation regulates anaphase spindle dynamics and cytokinesis in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 138, 385–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam, C.H., Fung, T.K., and Poon, R.Y.C. (2002). Cyclin A in call cycle control and cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59, 1317–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam, C.H., Ng, R.W., Siu, W.Y., Lau, A.W., and Poon, R.Y.C. (1999). Regulation of cyclin A-Cdk2 by SCF component Skp1 and F-box protein Skp2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 635–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam, C.H., Siu, W.Y., Kaganovich, D., Ruderman, J.V., and Poon, R.Y.C. (2001). Cleavage of cyclin A at R70/R71 by the bacterial protease OmpT. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 497–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam, C.H., Siu, W.Y., Lau, A., and Poon, R.Y.C. (2000). Degradation of cyclin A does not require its phosphorylation by CDC2 and cyclin-dependent kinase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 3158–3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H., Watkins, J.L., and Piwnica-Worms, H. (2002). Disruption of the checkpoint kinase 1/cell division cycle 25A pathway abrogates ionizing radiation-induced S and G2 checkpoints. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14795–14800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.B., and Elledge, S.J. (2000). The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature 408, 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]