Abstract

Pav-KLP is the Drosophila member of the MKLP1 family essential for cytokinesis. In the syncytial blastoderm embryo, GFP-Pav-KLP cyclically associates with astral, spindle, and midzone microtubules and also to actomyosin pseudocleavage furrows. As the embryo cellularizes, GFP-Pav-KLP also localizes to the leading edge of the furrows that form cells. In mononucleate cells, nuclear localization of GFP-Pav-KLP is mediated through NLS elements in its C-terminal domain. Mutants in these elements that delocalize Pav-KLP to the cytoplasm in interphase do not affect cell division. In mitotic cells, one population of wild-type GFP-Pav-KLP associates with the spindle and concentrates in the midzone at anaphase B. A second is at the cell cortex on mitotic entry and later concentrates in the region of the cleavage furrow. An ATP binding mutant does not localize to the cortex and spindle midzone but accumulates on spindle pole microtubules to which actin is recruited. This leads either to failure of the cleavage furrow to form or later defects in which daughter cells remain connected by a microtubule bridge. Together, this suggests Pav-KLP transports elements of the actomyosin cytoskeleton to plus ends of astral microtubules in the equatorial region of the cell to permit cleavage ring formation.

INTRODUCTION

Mutations in the Drosophila gene pavarotti lead to a failure of cytokinesis in cycle 16 of embryogenesis whereby cells fail to form a correctly organized central spindle in the late stages of mitosis and do not undergo cell division (Adams et al., 1998). The gene encodes a kinesin-like protein (Pav-KLP) that is a member of the MKLP-1 subfamily. In mammals, MKLP1 (Nislow et al., 1992) has a longer isoform CHO1 (Sellitto and Kuriyama, 1988), a splice variant with an additional exon (Kuriyama et al., 2002). Family members in other organisms include ZEN-4 in Caenorhabditis elegans (Raich et al., 1998) and KRP110 in sea urchin (Chui et al., 2000). The phenotype of zen-4 mutants in C. elegans suggests that the motor is required for completion of cytokinesis (Powers et al., 1998; Raich et al., 1998). In contrast, Drosophila Pav-KLP seems to have an additional role in initiation of cytokinesis, because pav mutant embryos at cycle 16 fail to form a contractile ring (Adams et al., 1998). In vitro microtubule bundling experiments with one of the founder members of the family, MKLP1, suggested that the protein might enable antiparallel microtubules to slide against each other (Nislow et al., 1992). This finding, which is supported by hydrodynamic experiments on sea urchin KRP110 (Chui et al., 2000), led to the suggestion that one of its functions might be in spindle elongation during anaphase. However, measurements of pole-to-pole distances indicated that such spindle elongation was unaffected in pavarotti mutants, thus arguing against an exclusive role for the motor protein in this process (Adams et al., 1998). Nevertheless, a function in regulating the organization of overlapping microtubules may still be important to establish correct central spindle structure for the correct execution of cytokinesis (Giansanti et al., 1998; Gatti et al., 2000).

The MKLP-1 family members have been reported at the central spindle during late anaphase and telophase and on the midbody after the completion of cytokinesis. During interphase the proteins accumulate in the nucleus before mitosis. In the incomplete cytokinesis that occurs during gametogenesis in Drosophila, Pav-KLP is retained in the ring canals that form from the contractile ring and that connect cells of the germ line within cysts (Carmena et al., 1998; Minestrini et al., 2002). Nuclear localization of a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged form of the protein was observed after its expression in the female germ line and could be prevented by mutations in either the conserved ATP binding site of the motor domain or in nuclear localization sequences in the C-terminal domain (Minestrini et al., 2002). Both such mutations led to the formation of stable arrays of cytoplasmic microtubules, and the progressive disruption of the actin cytoskeleton, ultimately resulting in the accumulation of cytoplasmic aggregates containing tubulin, actin, and at least some of their binding proteins.

A GTPase-activating protein for Rho family GTPases (CYK-4) is required to recruit the ZEN-4 protein to the central region of the late mitotic spindle (Jantsch-Plunger et al., 2000). These two proteins are physically complexed in C. elegans (Mishima et al., 2002) as are their fly counterparts, Pav-KLP and RacGAP50C (Somers and Saint, 2003). In mammals the corresponding GTPase-activating protein MgcRacGAP is also required for cytokinesis and associates with the central spindle in late mitosis (Hirose et al., 2001). In Drosophila, RacGAP50C has also been shown to interact with the Rho-GTP exchange factor encoded by pebble, a protein required to regulate actinomyosin organization in cytokinesis (Prokopenko et al., 1999; Somers and Saint, 2003). This points toward the existence of a multisubunit complex that can mediate interactions between the microtubule and actinomyosin cytoskeletons during cytokinesis. An interaction between the mammalian CHO1 KLP and actin has also been reported by Kuriyama et al. (2002), adding to evidence that this family of motor proteins plays a crucial role in mediating such cytoskeletal interactions.

The Drosophila embryo is syncytial for the first 13 rapid cycles of mitosis, suggesting that its maternal dowry of Pav-KLP might participate in processes other than cytokinesis. The nuclei are initially found in the interior of the embryo, but during division cycles 8 and 9 migrate to its surface. Syncytial blastoderm divisions (cycles 10–13) occurring at the cortex of the embryo then involve microtubule-mediated, cyclic rearrangements of F-actin and myosin II (Foe et al., 1993; Foe et al., 2000). Nuclei are contained within buds of cortical cytoplasm during interphase that flatten slightly concomitant with spindle formation during metaphase, break down when spindle poles separate during anaphase and telophase, and reform during interphase of the following cycle. Actin polymerizes at the cortex directly above the forming buds during telophase and interphase and cortical myosin II begins to vacate the regions where the F-actin “caps” form (Foe et al., 1993, 2000). As bud growth continues during prophase, newly polymerized actin is lost from the caps and accumulates at the sites already occupied by myosin II. Pseudocleavage furrows transiently form to separate neighboring buds during cycles 10–13 and so serve as barriers between adjacent spindles. After cycle 14, plasma membranes extend from the cortex to surround individual nuclei in a process that necessitates coordinate function of the actomyosin cytoskeleton and microtubules. A G2 phase is introduced into the 14th division cycle that occurs in distinct spatiotemporal domains.

In this article, we examine the dynamics of localization of GFP-tagged Pav-KLP in nuclear division cycles in syncytial embryos, in the process of cellularization, and in cell division cycles at subsequent stages. The localization of the Pav-KLP motor is consistent with its participation in interactions between the actomyosin and microtubule cytoskeletons at each of these stages. We find that during cell division Pav-KLP associates with the midzone region of the anaphase-telophase spindle as described previously, but also with the entire cortex of the cell later to concentrate at the contractile ring. This is perturbed by dominant mutants in the ATP-binding motif of the motor domain that result in an unusual accumulation of both the mutant protein and actin at the spindle poles. We discuss these patterns of intracellular localization with respect to the functions of the motor protein particularly in cytokinesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

GFP-tagged Pav-KLP and Its Variants

In this study, we have used genes expressing chimeric forms of GFP and Pav-KLP that were described previously (Minestrini et al., 2002). To study the dynamics of Pavarotti localization at different stages of embryonic development, we carried out observations on embryos derived from females homozygous for a second-chromosomal insertion of a ubiquitin-driven gfp-pavarotti transgene.

We also studied a number of mutant forms of Pav-KLP that were described by Minestrini et al. (2002), except that rather than being cloned into the pUASp vector (Rorth, 1998) they were cloned into pUAST (Brand and Perrimon, 1993). This permitted expression in the soma rather than the female germ line. The chimeric genes encode GFP-tagged full-length wild-type protein; forms carrying point mutations in one, three, or four C-terminal putative nuclear localization signals [UAS-GFP-PavNLS5*; GFP-PavNLS(5-7)*, or GFP-PavNLS(4-7)*, respectively]; and a form carrying a mutation in the ATP binding region of the motor domain (UAS-GFP-PavDEAD). These were introduced into Drosophila by using standard techniques for germ line transformation. Expression of GAL4 from the tub(matα4)GAL4-VP16 transgene (a kind gift of D. St Johnston, Wellcome Trust-CRUK Institute, Cambridge, United Kingdom) was then used to drive expression of the GFP-tagged Pav-KLP mutant. Flies carrying two copies of the UAS-GFP-PavNLS5* transgene and two copies of the GAL4-VP16 transgene were viable and fertile and could therefore be kept as a homozygous stock. Similarly, flies carrying two copies of GFP-PavNLS(5-7)* or GFP-PavNLS(4-7)*, which carry deletions of, respectively, three or four NLS-like motifs and two copies of the GAL4-VP16 driver transgene could also be kept as a homozygous stock. To observe the phenotype of GFP-PavDEAD, it was necessary to cross females homozygous for the tub(matα4)GAL4-VP16 transgene to males homozygous for the pUAST-GFP-PavDEAD transgene and analyze the resulting F1 embryos.

To determine whether expression of GFP-PavNLS(5-7)* or GFP-PavNLS(4-7)* could rescue the embryonic lethality of pav mutant embryos, we expressed these constructs in a pav mutant background when GAL4 was matrernally provided from tub(matα4)GAL4-VP16. This led to rescue of the embryonic lethality with the pav mutants surviving to late pupal and adult stages.

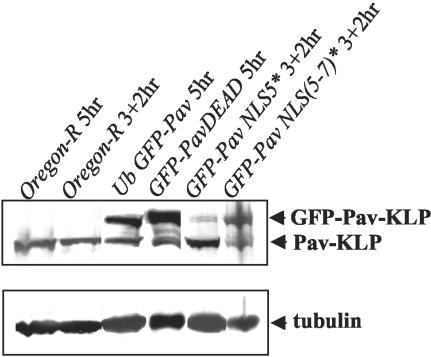

To monitor expression levels of GFP-tagged forms of Pav-KLP, embryos were collected on grape juice agar plates from each of these lines and from an Oregon R wild-type stock either over a 5-h period or over a 3-h period and then allowed to develop for a further 2 h. They were then dechorionated using 50% bleach for 3 min, washed, and homogenized on ice in 1 mM Mg Cl2, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5. An equal volume of 3× SDS-gel loading buffer was added and the samples boiled for 5 min and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 min at room temperature before being subjected to electrophoresis on 10% polyacrylamide SDS gels followed by Western blotting. A 1:5000 dilution of the rabbit anti-Pav-KLP antibody GM2 raised against the bacterially expressed full-length protein (Minestrini, 2001) was used to detect both wild-type and GFP-tagged forms of Pavarotti. The mouse anti-tubulin N356 antibody was used to detect tubulin as a loading control. Levels of expression of the transgenic constructs are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Western blot to show expression levels of GFP-tagged forms of Pav-KLP. Embryo extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS.

Time-Lapse Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy

Embryos were collected at 25°C on grape juice agar plates. All subsequent operations were performed at 18°C. Embryos were dechorionated by hand with forceps and transferred to a drop of Voltalef 10S halocarbon oil sitting on a slide. Two coverslips were put on each side of the drop to prevent squashing of the embryos, which were covered with another coverslip. All images were acquired on an MRC-1024 confocal microscope (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Time series were generated using the “Time Series” function of the Bio-Rad software. Each image results from two to three scans of the sample, and new images were acquired every 20–60 s. In general, each embryo was not followed for >1 h.

Fixation and Immunostaining of Embryos

Embryos were collected at 25°C on grape juice agar plates, dechorionated by using 50% bleach, and washed before fixation. For phalloidin staining, embryos were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 20 min and devitellinized using 80% ethanol. For immunostaining without phalloidin, embryos were fixed with 37% formaldehyde for 5 min and devitellinized using 100% methanol. Embryos were blocked for 1 h in PBT (Phosphate Buffered Saline [Sigma] plus 0.1% Triton X-100) + 1% bovine serum albumin and the anti-Pavarotti GM2 antibody (1/500) was incubated overnight at 4°C. Embryos were washed in PBT and then incubated in fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated secondary antibody (1/200; Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 2 h at room temperature before again washing in PBT. Phalloidin staining (phalloidin-Texas Red, 1/200; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was then performed for 1 h in PBT before mounting in Vectashield mounting medium H-1000 (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). TOTO-3 iodide staining for DNA (1/1000; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was performed overnight at 4°C before mounting in Vectashield mounting medium H-1000 (Vector Laboratories). All images were acquired on an MRC-1024 confocal microscope (Bio-Rad).

RESULTS

In Preblastoderm Embryos GFP-Pav-KLP Associates With Astral and Spindle Microtubules Independently of the Actomyosin Cytoskeleton

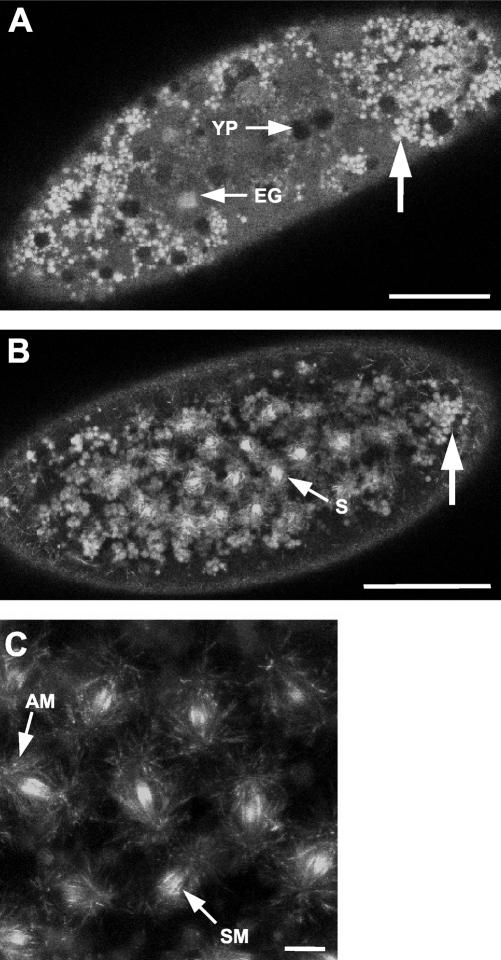

Because Pav-KLP is supplied to the Drosophila embryo as a maternal dowry (Adams et al., 1998), we wished to follow the dynamics of its localization before the onset of zygotic gene expression. We first examined the distribution of Pav-KLP before the microtubules of the mitotic apparati within the syncytium make contact with the actomyosin structures at the cortex. The first nine nuclear division cycles occur in the interior of the embryo and during this time nuclei become uniformly distributed along the anterior posterior axis of the embryo before they undergo their cortical migration. We found these early embryos contain aggregates of GFP-Pav-KLP (Figure 2, A and B, arrow) that can be distinguished from the dark yolk particles (Figure 2A, YP). Because nuclei increase in number throughout mitotic cycles 1–9, GFP-Pav-KLP binds to the spindle microtubules as soon as the spindle is established (Figure 2B, S). It concentrates at the spindle midzone (SM) during anaphase and telophase and along astral microtubules (Figure 2C, AM).

Figure 2.

Maternally contributed GFP-Pav-KLP becomes incorporated into spindle microtubules in preblastoderm syncytial embryos. (A) Live early preblastoderm embryo in which GFP-Pav-KLP is found in small aggregates (arrow) that seem preferentially distributed at both embryonic poles. Energids (EG), the developing somatic nuclei, look like light fluorescent spheres, whereas yolk particles (YP) are dark spheres that exclude fluorescent protein. Bar, 100 μm. (B) Preblastoderm embryo at a later stage than in A undergoing mitosis. GFP-Pav-KLP is found on spindle microtubules (S) and is still present in maternal aggregates (arrow). Bar, 100 μm. (C) Field of mitotic nuclei in the late stages of their migration to the cortex of the embryo. GFP-Pav-KLP binds to AMS and moves along interpolar microtubules to the SM. Bar, 10 μm.

At Syncytial Blastoderm GFP-Pav-KLP Accumulates in Midbodies and Is Recycled into the Cortical Actomyosin Cytoskeleton

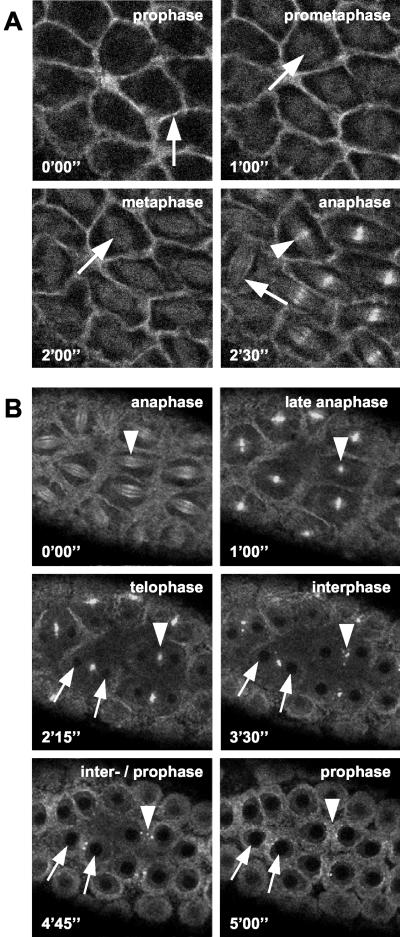

The actomyosin cytoskeleton becomes organized into a network that surrounds the migrating nuclei as they arrive at the cortex before cycle 10 at the onset of the syncytial blastoderm stage. In many respects, the distribution of GFP-Pav-KLP in this network resembles that described for myosin II (Foe et al., 2000). During prophase, GFP-Pav-KLP moves away from the regions occupied by cytoplasmic buds and accumulates in the pseudocleavage furrows that separate neighboring nuclei (Figure 3A, arrow at 0′00″). Concomitant with the breakdown of the nuclear membrane at the poles at the onset of prometaphase (Stafstrom and Staehelin, 1984), GFP-Pav-KLP moves into the region occupied by the spindle, with which it stays associated throughout metaphase (Figure 3A, arrows at 1′00″ and 2′00″). At the onset of anaphase the motor protein is more clearly associated with spindle microtubules (Figure 3A, arrow at 2′30″) and moves toward the midzone region (arrowheads in Figure 3, A and B, at 2′30″ and 0′00″, respectively) where it concentrates throughout telophase (Figure 3B, arrowhead at 1′00″). During the interphase preceeding the next cycle, GFP-Pav-KLP is not associated with nuclei (Figure 3B, arrows at 2′15″ and 3′30″) and has a more diffuse distribution on the cortical cytoskeleton. As the embryo moves into prophase the GFP-Pav-KLP that accumulated in midbodies becomes incorporated into the pseudocleavage furrows as they reform (Figure 3B, arrows at 2′15″ to 5′00″).

Figure 3.

Association of GFP-Pav-KLP with pseudocleavage furrows and spindle midzone during nuclear division cycles of the syncytial blastoderm. Two series of time frames from live syncytial blastoderm embryos undergoing mitosis. Time intervals are indicated in minutes and seconds. (A) At prophase, GFP-Pav-KLP vacates the cortical region above protruding nuclei and accumulates in the pseudocleavage furrows (arrow at 0′00″). From prometaphase to anaphase, GFP-Pav-KLP shows an additional association with the spindle (arrows at 1′00″ to 2′30″) and becomes concentrated along spindle microtubules (arrow at 2′30″) in the spindle midzone (arrowhead at 2′30″). (B) GFP-Pav-KLP is also accumulating at the spindle midzone in the anaphase of this second series (arrowhead at 0′00″) to become concentrated at the midbody during late anaphase (arrowhead at 1′00′) and telophase (arrowhead at 2′15″). The positions of two sister nuclei are marked with arrows from telophase to the subsequent prophase (2′15″ to 5′00″). GFP-Pav-KLP from the midbodies fragments and becomes incorporated into pseudocleavage furrows during interphase and into the prophase of the next cycle (arrowheads from 3′30″ to 5′00″).

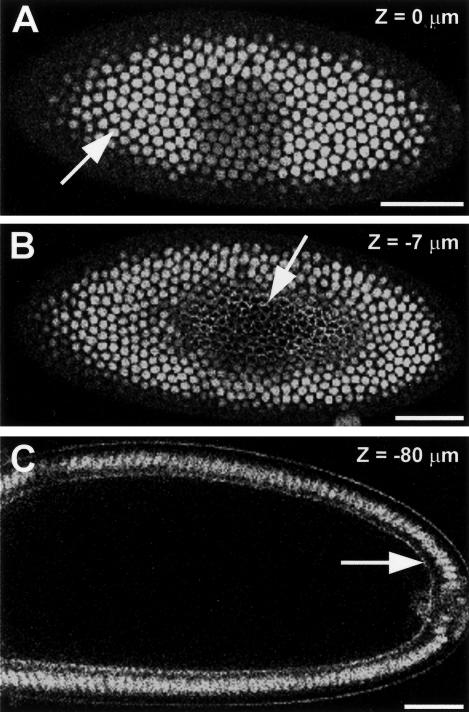

GFP-Pav-KLP Is Present at the Leading Edge of the Furrow Canals and in the Somatic Nuclei During Formation of the Cellular Blastoderm at Cycle 14

The lengthening of interphase that occurs in the syncytial blastoderm stages permits increasing levels of GFP-Pav-KLP to accumulate within nuclei reaching high levels during cycle 14 (Figure 4A, arrow). It is also present at lower levels in the cortical network that surrounds each nucleus (our unpublished data). As cellularization proceeds GFP-Pav-KLP concentrates at the leading edge of invaginating furrow canals (Figure 4, B and C, arrows) until they reach their maximum depth of ∼30 μm from the surface (Young et al., 1991). Thus, GFP-Pav-KLP becomes localized with the actomyosin rings at the basal end of the nascent columnar cells that contract to complete cellularization (Warn, 1986; Pesacreta et al., 1989; Young et al., 1991). This suggests that GFP-Pav-KLP might be the motor that, through interactions with the membrane-bound actomyosin ring, could participate in pulling furrows down around cells moving toward the plus end of astral microtubules that extend toward the interior of the embryo, a mechanism previously suggested by Foe et al. (1993, 2000).

Figure 4.

GFP-Pav-KLP accumulates in nuclei and at the leading edge of furrow canals during formation of the cellular blastoderm at cycle 14. (A–C) Optical sections of an embryo at cellularization. (A) A plane close to the embryo surface in which GFP-Pav-KLP is seen concentrated in the cell nuclei (arrow). (B) An optical section of the same embryo at a depth of 7 μm more toward the interior. The depth of focus is coincident with the leading edge of the furrow canals, with which GFP-Pav-KLP is associated (arrow). (C) Saggital section of the same embryo (80 μm deeper than section A) reveals that GFP-Pav-KLP is present in the leading edge of the furrow canals (arrow) but is not visible in the lateral parts of the membrane that separates the nuclei. Bars, 20 μm.

In Mononucleate Cell Division GFP-Pav-KLP Cycles from the Nucleus to the Cellular Cortex and Concentrates in the Cleavage Furrow

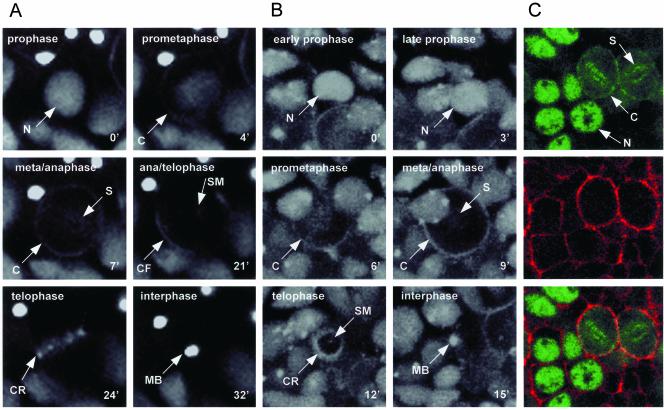

The staining of fixed preparations of cellularized embryos had previously shown that Pav-KLP was associated with interphase nuclei and with the mitotic spindle during mitosis (Adams et al., 1998). The lines expressing GFP-Pav-KLP allowed us to examine the dynamics of this redistribution. Two such cells undergoing mitosis are shown from separate viewpoints in Figure 5, A and B (lateral in A and polar in B). During prophase, GFP-Pav-KLP was only found in the cell nucleus (N in Figure 5, A and B, at 0′). On partial break down of the nuclear membrane during prophase/prometaphase, GFP-Pav-KLP was released from the nucleus and began to accumulate at the cell cortex (C in Figure 5A at 4′; B at 6′). In metaphase and early anaphase it seemed to be uniformly distributed around the cortex (C in Figure 5A at 7′; B at 9′). At these times what seemed to be a smaller proportion of GFP-Pav-KLP associated with the spindle. It can be seen along the length of the region occupied by the spindle in Figure 5A (S at 7′) and looking “end-on” at the spindle in Figure 5B (S at 9′). During late anaphase and telophase, the cortical GFP-Pav-KLP moved away from the poles of the dividing cell and began to concentrate in the region where the cleavage furrow was about to form (CF in Figure 5A at 21′). At this same time, spindle-bound GFP-Pav-KLP seemed to translocate to the SM. During telophase, the cortical GFP-Pav-KLP had concentrated into the cleavage ring (CR in Figure 5A at 24′). The polar viewpoint of the other cell at a slightly later stage of telophase showed that seemingly the majority of GFP-Pav-KLP was within this cortical ring as it contracted (CR in Figure 5B at 12′). However, some of the labeled protein was also associated with the SMs running through the cleavage ring. As the daughter cells entered interphase at the end of cytokinesis, the GFP-Pav-KLP was concentrated in the midbody (MB in Figure 5, A and B at 32′ and 15′, respectively). To localize GFP-Pav-KLP with respect to the actin cytoskeleton, we stained such embryos with Texas Red-labeled phalloidin. A major subpopulation of GFP-Pav-KLP (Figure 5C, green) could clearly be seen to colocalize with cortical actin (red) in early mitotic cells.

Figure 5.

Nuclear GFP-Pav-KLP reassociates with the cell cortex and the spindle microtubules during embryonic mononucleate cell divisions. (A and B) Two time-lapse series of dividing cells, one in which the axis of the spindle lies in the focal plane (A) and the other looking down the spindle axis that lies perpendicular to the focal plane (B). The mitotic phase is indicated for each time frame and time points are given in minutes. GFP-Pav-KLP seems to relocate from the nucleus (N) to the cell cortex (C) from where it becomes concentrated in the region of the cleavage furrow (CF) and then to be integrated into the CR. Some GFP-Pav-KLP also associates with the spindle (S) and the SM. By interphase GFP-Pav-KLP in the cleavage ring and spindle midzone seem to coalesce in the MB. (C) An example of a fixed embryo showing an identical localization of GFP-Pav-KLP to the nucleus (N), cell cortex (C), and S. GFP-Pav-KLP is shown in green (top), phalloidin stain for filamentous actin is shown in red (middle), and a merge of these two images (bottom).

Failure of GFP-Pav-KLP to Relocalize to the Nucleus Seems Not to Affect Embryonic Cell Division

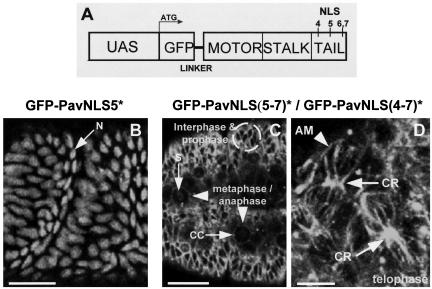

We have previously shown that when Pav-KLP was ectopically expressed in the female germ line, it would accumulate in nurse cell nuclei (Minestrini et al., 2002). This nuclear accumulation could be prevented by mutations in classical nuclear localization sequences in the C-terminal domain of the molecule or by a mutation in the ATP-binding site, resulting in a putatively inactive motor. Elevated expression of such mutant constructs resulted in the accumulation of stable cytoplasmic microtubules and a disruption of the actomyosin cytoskeleton of the egg chamber. We wished to determine the consequences of preventing the nuclear accumulation of Pav-KLP in dividing cells by expressing these same mutant constructs. We first found that the C-terminal nuclear localization signal 5 (NLS5) was not responsible for directing import of GFP-Pav-KLP into embryonic nuclei just as we had previously found for nurse cell nuclei (Minestrini et al., 2002). Flies carrying two copies of the UAS-GFP-PavNLS5* transgene and two copies of the GAL4-VP16 transgene were viable and fertile and could therefore be kept as a homozygous stock. Moreover, the subcellular distribution of the labeled molecule throughout mitosis followed exactly the same temporal pattern as wild-type protein and during interphase showed strong nuclear localization (Figure 6B). Similarly, expression of either GFP-PavNLS(5-7)* or GFP-PavNLS(4-7)* which carry point mutations in, respectively, three or four NLS-like motifs also showed no dominant effect on viability. Flies carrying two copies of the UAS construct directing the expression of either such a mutant protein and two copies of the GAL4-VP16 driver transgene could also be kept as a homozygous stock. However, both GFP-PavNLS(5-7)* and GFP-PavNLS(4-7)* were excluded from the nucleus and mainly associated with cytoplasmic microtubules of interphase cells (Figure 6C). The two forms of the mutant protein also showed a similar distribution in mitotic cells and localized at the cell cortex (CC in Figure 6C) and on the spindle in cells at prophase and through to metaphase and early anaphase. From late anaphase to telophase, the nuclear localization mutant proteins became concentrated at the cleavage furrow region to associate with the contractile ring throughout cytokinesis (Figure 6D, CR). The association of these mutant proteins with microtubules is pronounced at this stage particularly in the region of the cleavage ring. By the end of cytokinesis, the protein had accumulated in midbodies that were shed into the interstitial regions between interphase cells as is also seen with the wild-type protein. Together, this indicates that the overlapping nuclear localization signals 6 and 7 are necessary for nuclear import of Pavarotti and that at this stage of development and levels of expression failure of the protein to translocate to the nucleus is not deleterious to cell proliferation or to development. This was not simply due to the coexpression of endogenous wild-type protein in these embryos. We found that expression of either GFP-PavNLS(5-7)* or GFP-PavNLS(4-7)* can rescue the embryonic lethal pav mutant phenotype allowing survival of homozygous pav mutants to late pupal and adult stages from these constructs when driven by maternally provided GAL4.

Figure 6.

A subset of nuclear localization sequences is responsible for directing nuclear import of Pav-KLP. (A) A UAS construct, GFP-PavNLS(4-7)*, carried in germ line transformants, indicating the position of four potential NLSs subjected to point mutation. (B) Surface view of a live cellularized embryo showing that Pav-KLP carrying a mutation in NLS5, GFP-PavNLS5*, continues to accumulate in the nucleus (N) during prophase. (C) Expression of GFP-PavNLS(5-7)* in extended germ band embryos. A dashed circle surrounds a group of cells in interphase and prophase, that have GFP-PavNLS(5-7)* at the cell cortex. Arrowheads indicate cells at metaphase or anaphase, in which GFP-PavNLS(5-7)* is associated with the spindle (S) and the cell cortex (CC). (D) Telophase cells from a cellularized embryo in which GFP-PavNLS(5-7)* associates with cortex-bound AMs and the CR. Similar localization patterns are seen for GFP-PavNLS(4-7)* (our unpublished data). Bars, 5 μm (D) and 50 μm (B and C).

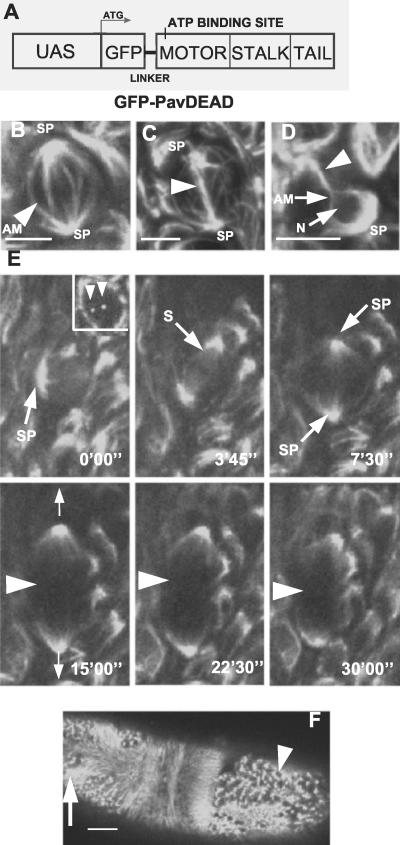

GFP-PavDEAD Accumulates with Actin on Spindle Pole Microtubules

We wished to know the extent to which the dynamic pattern of Pav-KLP localization in the mitotic cycles of mononucleate cells required its own motor activity. To this end, we followed the localization pattern of GFP-PavDEAD, a variant that carries a point mutation in a conserved residue of the ATP-binding region of the motor domain. We followed the distribution of this protein in embryos derived from mothers homozygous for the GAL4-VP16 transgene that had been mated to males homozygous for the UAS-GFP-PavDEAD transgene (Figure 7A). Such mothers accumulate GAL4 in their oocytes expressed from the maternal α4-tubulin promoter that in turn drives the expression of the paternally provided transgene in the late blastoderm embryo. We observed two consequences upon the extent of cytokinesis exhibited during cycles 14–16 of the cellularized embryo. One group of cells initiated but failed to complete cytokinesis. They accumulated GFP-PavDEAD at their spindle poles (SPs) and along AMs throughout prometaphase to anaphase (Figure 7B). At late anaphase/telophase, GFP-Pav-DEAD labeled narrow bundles of microtubules that connected the spindle poles (Figure 7C). These persisted as microtubular bridges between daughter cells (arrowhead in Figure 7D) that were connected to cytoplasmic microtubules. The other group of cells seemed not to initiate cytokinesis and accumulated GFP-Pav-DEAD at their SPs. Weak spindle staining could be seen (S in Figure 7E at 3′45″) that diminished further at later stages, suggesting the putative inactive motor might be transported to the poles from both astral and spindle microtubules by a minus end-directed motor or through the poleward flux. Most of the GFP-PavDEAD remained uniformly distributed at both spindle poles thereafter. Interestingly spindle lengthening occurred as though anaphase B were taking place (Figure 7E, between 7′30″ and 15′00″), indicating that the construct does not have a dominant negative effect upon this aspect of spindle function. However, not only did GFP-Pav-KLP fail to localize with any aspect of the contractile ring (arrowhead in Figure 7E, 15′00″ to 30′00d′), but cytokinesis was prevented. The consequence to the embryo was an accumulation of cells blocked in cell division (Figure 7F, arrowhead) and of cells containing abnormal arrays of microtubules (Figure 7F, arrow) both of which compromised development. We were unable to observe accumulation of GFP-PavDEAD in interphase nuclei, in association with the cortical regions of the cell or with any aspect of the contractile ring structure.

Figure 7.

GFP-PavDEAD accumulates at the spindle poles and leads to stabilized microtubules. (A) Schematic representation of the UAS construct coding for GFP-PavDEAD that carries a point mutation in the ATP-binding site. (B–D) Distribution of GFP-PavDEAD in cells undergoing cell division. (B) GFP-PavDEAD is found at the SPs and along the AMs at metaphase. (C) At anaphase, GFP-PavDEAD is not only present at the SPs but also along a connection that has formed between the two poles (arrowhead). (D) Toward the completion of cytokinesis, AMs remain at the SP and still surround the nucleus (N) to form a bridge (arrowhead) between the daughter cells. (E) A time series of confocal images of a cell expressing GFP-PavDEAD. Time points are given in minutes and seconds. GFP-PavDEAD is found at separating centrosomes (arrowheads in inset at 0′00″) and the SPs throughout the cell division and is missing from the cell cortex and the cleavage ring (arrowheads at 15′00″ to 30′00″). (F) Example of an embryo that has accumulated apparently stabilized microtubules (arrow). Such embryos fail to develop. The arrowhead points at a group of cells, in which GFP-PavDEAD is localized at spindle poles/centrosomes. Bars, 5 μm (B–D) and 50 μm (E).

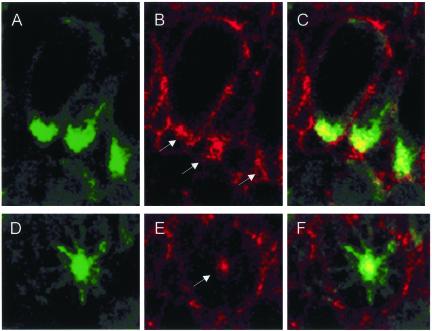

Because the localization of GFP-Pav-KLP in wild-type embryos suggested dynamic interactions with the actomyosin cytoskeleton, we wished to know whether this might be affected by accumulation of GFP-Pav-DEAD at the spindle poles. We therefore stained such cells with phalloidin to reveal actin in relation to GFP. The glancing section of three cells shown in Figure 8, A–C, shows the unusual accumulation of actin (red) in the vicinity of spindle poles that are heavily decorated with GFP-Pav-DEAD. The association of actin at the focus of such a pole in a cell sectioned through the centrosome is also shown (Figure 8, D–F). Thus, as previously observed after the expression of this molecule in oogenesis (Minestrini et al., 2002), mutation in the ATP-binding pocket seems to cause stable association of the motor protein with microtubules and thereby to affect the subcellular distribution of actin.

Figure 8.

Expression of GFP-PavDEAD results in abnormal accumulation of actin around spindle poles. Optical sections through individual spindle poles in fixed preparations of cellularized embryos to show GFP-PavDEAD (green; A and D) and actin (red; B and E). C and F are merged images. Three cells in glancing section (A–C) and one sectioned through the centrosome (D–F) showing strong accumulation of GFP-PavDEAD at the spindle poles. In addition to labeling the cell cortex actin accumulates at the poles (arrows; yellow in merged images).

DISCUSSION

Our findings extend those from a study of the phenotype of pavarotti mutant embryos where a role for the gene product in cytokinesis was indicated by the generation of binucleate cells (Adams et al., 1998). Although spindle elongation seemed to take place during anaphase, a properly organized central spindle did not form. Moreover, pavorotti mutants failed to initiate the formation of an actomyosin contractile ring after anaphase. These observations added to growing evidence that formation of the midzone region of the central spindle is a necessary precondition to organize the cleavage ring for cytokinesis. The immunolocalization of Pav-KLP to the spindle midzone was in keeping with such a role. The present study of the localization of GFP-tagged Pav-KLP in living embryos shows the motor protein also to be present at known sites of interaction between putative plus ends of microtubules and the actomyosin cytoskeleton in both synctial and cellularized embryos.

For the first 10 division cycles of the syncytial embryo, Pav-KLP seems not to interact with the actomyosin cytoskeleton. Before blastoderm most of the protein associates with the spindle. During this period, the molecule concentrates at the midzone during anaphase, much as it does in mononucleate cells, consistent with a plus end-directed motor activity. It also shows particularly strong labeling of astral microtubules. In this latter respect, localization of GFP-Pav-KLP differs from the previous observations by immunostaining that detected the endogenous protein on centrosomes rather than asters. Although either of these experimental approaches could lead to artifacts, it seems most likely that the particularly sensitive astral microtubules were insufficiently well preserved in the previous immunolocalization studies and so collapsed back to the centrosome during fixation. Its presence on astral microtubules may indicate a role in sliding antiparallel astral overlap microtubules against each other. Such a function is needed to keep the correct spacing between neighboring nuclei and for cortical migration of the nuclei during cycles 7–9 (Zalokar and Erk, 1976; Foe et al., 1993).

The characteristic colocalization of Pav-KLP with microtubules and actomyosin throughout subsequent successive stages of embryogenesis that suggest it could mediate a crucial link between these components of the cytoskeleton. Once nuclei have migrated to the cortex, Pav-KLP begins a dynamic pattern of colocalization with putative plus ends of spindle microtubules and the cortical actomyosin cytoskeleton. During metaphase it associates with pseudocleavage furrows and then in anaphase and telophase, spindle associated GFP-Pav-KLP molecules move toward the central spindle and concentrate in the midbody.

During cycle 14 membranes extend toward the embryo's interior to compartmentalize the 6000 or so cortical nuclei (Foe et al., 1993). At this time, GFP-Pav-KLP is present both in the nucleus and at the tips of invaginating membranes where F-actin, myosin II, Peanut, and anillin are also known to localize. The movement of the actomyosin network and its associated proteins to invaginate membranes around the newly forming cells has been postulated to track along microtubules with a plus end-directed motor providing the motile force (Foe et al., 1993; Foe et al., 2000). Pav-KLP is certainly one candidate for such a task.

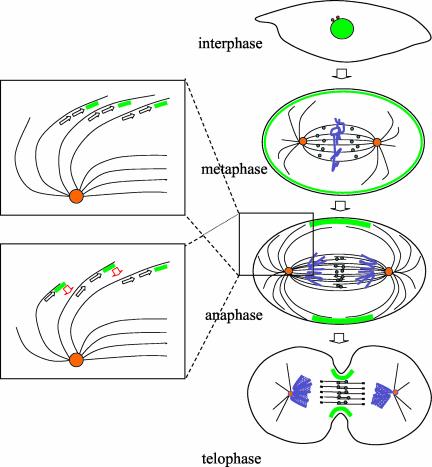

The dynamics of GFP-Pav-KLP localization in mononucleate cells undergoing cell division from cycle 14 onwards is consistent with the motor having at least two roles in facilitating the reorganization of the actomyosin cytoskeleton for cell division: one in the organization of or the transport of molecules along the central spindle during anaphase and telophase; and the other in reorganizing cortical molecules along astral microtubules. Our observations of the localization of GFP-Pav-KLP throughout cell division are summarized schematically in Figure 9. GFP-Pav-KLP is present in the cell nucleus until prophase and is redistributed into two populations after breakdown of the nuclear membrane. The first is represented by a low level of GFP signal occurring on the mitotic spindle around the time of metaphase and that will move to the spindle midzone from anaphase onward. The second population of GFP-Pav-KLP seems to constitute most of the GFP fluorescence. It is uniformly distributed at the cell cortex throughout metaphase. Such cortical association of the endogenous Pav-KLP is also apparent by immunostaining and can be seen in the original article of Adams et al. (1998). From anaphase to telophase, cortical GFP-Pav-KLP moves from the polar regions of the cortex toward the equatorial region where the cleavage furrow will form. Herein, it becomes incorporated into the cleavage ring. This dynamic relocalization of the protein is consistent with Pav-KLP providing the motor protein functions to transport components of the actomyosin cytoskeleton toward the plus ends of cortical microtubules to concentrate in a cylinder whose perimeter will become the contractile ring. Similar ideas have been previously suggested for plus end-directed motors by Foe et al. (2000). At the end of the division, when the ring is fully contracted, all GFP fluorescence accumulates in the midbody, and thus the majority of Pav-KLP seems to be discarded from the daughter cells with the loss of this structure.

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of distribution of Pav-KLP with respect to the cell cortex and the developing central spindle. Cells are shown at the indicated stages of division in which the distribution of Pav-KLP has been shown diagrammatically to represent the findings in this article. The motor protein is nuclear during interphase and prophase, but then separates into two populations: one associated with spindle microtubules (dark green) and the other with the cell cortex (light green) where we postulate it is complexed to components of the actomyosin cytoskeleton. We suggest the former population of molecules is responsible for organizing overlapping microtubules in the central region of the spindle. The insets illustrate how Pav-KLP might concentrate actomyosin-associated molecules in the equator of the cell. One possibility (top box) is that Pav-KLP and its associated cargo might move toward the plus ends of astral microtubules (open black arrows) ending in the equatorial region of the cell cortex. Alternatively, if microtubule ends are destabilized, the motor protein and its cargo might be transferred to an adjacent microtubule that extends further toward the equatorial region of the cell (open red arrows; bottom box). In this way, the motor and its cargo would accumulate around the nascent cleavage ring. Centrosomes are shown in orange and chromosomes in blue.

Surprisingly, neither the formation and function of the mitotic spindle nor cytokinesis is visibly affected in embryonic cells expressing GFP-PavNLS(4-7)*, a mutant form of the protein lacking nuclear localization sequences and unable to localize to the nucleus during interphase. Cell division of otherwise wild-type embryos seems not to be affected by expression of this mutant molecule that is still able to localize to the cell cortex and at later stages of the division to the cleavage ring. Moreover expression of GFP-PavNLS(4-7)* mutant in a pav background is able to rescue the embryonic lethality of this stock, allowing survival to late pupal and adult stages. On the other hand, expression of the putatively immotile GFP-PavDEAD molecule with a mutation in its ATP-binding site results in dominant lethality. This mutant form of Pav-KLP not only fails to enter the nucleus but also shows significantly reduced association with the cell cortex. This suggests that the plus end-directed motor activity of Pav-KLP is essential for its cortical localization and equatorial concentration. The rigor-like association of GFP-PavDEAD with microtubules is similar to that seen with an equivalent point mutation in the ATP-binding domain of the yeast motor protein Kar3p (Meluh and Rose, 1990). Moreover, a similar mutant of the centromere-associated mitotic centromere-associated kinesin has also been observed to undergo rigor binding to microtubules and fails to enter the nucleus (Wordeman et al., 1999). The GFP-PavDEAD protein seems not to be released from microtubules and is itself transported polewards. Two dominant mutant phenotypes are seen, presumably reflecting different degrees of expression of GFP-PavDEAD between cells. In the first, cells fail to enter cytokinesis and show no sign of formation of either a cleavage furrow or a central spindle. In this respect they resemble cells in pavarotti mutant embryos (Adams et al., 1998). In the second group of cells expressing the dominant mutant, daughter cells are produced that remain connected by stable microtubules, indicating defects at later stages of cytokinesis. This phenotype is very similar to that obtained by Matuliene and Kuriyama (2002) after the expression of the CHO1 isoform of mammalian MKLP1 with a mutation in its ATP-binding domain in CHO cells. This together with the finding that depletion of CHO1 by RNAi led to disorganization of midzone microtubules led these authors to conclude that this form of the mammalian homolog functions to ensure midbody formation for the completion of cytokinesis. Although it is possible that the homologous proteins have subtly different functions in different species or cell types, being required for the initiation of cytokinesis in some (`Adams et al., 1998) and its completion in others Powers et al., 1998; Raich et al., 1998; Matuliene and Kuriyama, 2002), it is difficult to draw direct comparisons because one cannot be sure of the extent to which function is lost either in mutants or in RNAi experiments. However, expression of the “motor-dead” protein in Drosophila does suggest both early and late roles for the molecule in cytokinesis.

A striking feature of cells in which the initiation of cytokinesis is prevented by expression of GFP-PavDEAD is the accumulation of the inactive motor protein on spindle pole microtubules. This may reflect either its transport by a minus end-directed motor or it may be the consequence of polar mircrotubule flux. A consequence of this is the accumulation of actin in the vicinity of the centrosome. A reorganization of the actomyosin cytoskeleton was also seen when this mutant form of the protein was expressed in Drosophila oogenesis (Minestrini et al., 2002). Although we do not know the molecular mechanism behind this reorganization of the actomyosin cytoskeleton, it indicates that the motor protein is able to mediate associations between the actomyosin and microtubule cytoskeletons. Such interactions are central to cytokinesis in wild-type cells and in other processes that share aspects of this machinery at other stages in Drosophila development.

The mammalian counterpart of Pav-KLP, CHO1, has also been shown to interact with actin (Kuriyama et al., 2002). In this case, the interaction has been mapped to an exon that is not present in the splice variant form MKLP1. It is not known however, whether this interaction is direct or indirect. On the other hand, MKLP1 has been shown to undergo a direct interaction with a small G protein, Arf, that is required for membrane trafficking and may have a function in facilitating membrane fusion events at cytokinesis (Bowman et al., 1999). Two members of the MKLP1 family have also been shown to interact directly with a conserved Rhofamily GTPase-activating protein. In C. elegans, this is encoded by cyk-4 (Jantsch-Plunger et al., 2000; Mishima et al., 2002) and in Drosophila it corresponds to RacGAP50C (Somers and Saint, 2003). Somers and Saint (2003) have proposed that Pav-KLP transports RacGap50C along cortical microtubules to the cell equator. Once at the cell equator, it is proposed that RacGAP50C mediates another interaction with the Pebble Rho GEF to position contractile ring formation and coordinate F-actin remodeling (Somers and Saint, 2003). Tatsumoto et al. (1999) have shown that Ect2, a mammalian ortholog of Pebble, is also involved in cytokinesis. Many components of this emerging complex remain to be defined. It does not seem that the Pebble GEF opposes RacGAP50C, thus leaving the open question of what the respective opposing proteins might be. It is of considerable future interest to determine precisely how Pav-KLP interacts with other proteins and how they are loaded and unloaded during the highly dynamic process of cytokinesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthew Savoian for helpful comments on the manuscript. Cancer Research UK and the European Union provided support for this work.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E03–04–0214. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E03-04-0214.

Online version of this article contains video material. Online version is available at www.molbiolcell.org.

References

- Adams, R.R., Tavares, A.A.M., Salzberg, A., Bellen, H.J., and Glover, D.M. (1998). pavarotti encodes a kinesin-like protein required to organize the central spindle and contractile ring for cytokinesis. Genes Dev. 12, 1483–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, A.L., Kuai, J., Zhu, X., Chen, J., Kuriyama, R., and Kahn, R.A. (1999). Arf proteins bind to mitotic kinesin like protein 1 (MKLP1) in a GTP dependent fashion. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 44, 119–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand, A.H., and Perrimon, N. (1993). Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118, 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmena, M., Riparbelli, M.G., Minestrini, G., Tavares, A.M., Adams, R., Callaini, G., and Glover, D.M. (1998). Drosophila Polo kinase is required for cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 143, 659–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chui, K.K., Rogers, G.C., Kashina, A.M., Wedaman, K.P., Sharp, D.J., Nguyen, D.T., Wilt, F., and Scholey, J.M. (2000). Roles of two homotetrameric kinesins in sea urchin embryonic cell division. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 38005–38011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foe, V.E., Odell, G.M., and Edgar, B.A. (1993). Mitosis and morphogenesis in the Drosophila embryo: point and counterpoint. In: The Development of Drosophila melanogaster, ed. M. Bate and A. Martinez-Arias, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 149–300.

- Foe, V.E., Field, C.M., and Odell, G.M. (2000). Microtubules and mitotic cycle phase modulate spatiotemporal distributions of F-actin and myosin II in Drosophila syncytial blastoderm embryos. Development 127, 1767–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatti, M., Giansanti, M.G., and Bonaccorsi, S. (2000). Relationships between the central spindle and the contractile ring during cytokinesis in animal cells. Microsc. Res. Tech. 49, 202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giansanti, M.G., Bonaccorsi, S., Williams, B., Williams, E.V., Santolamazza, C., Goldberg, M.L., and Gatti, M. (1998). Cooperative interactions between the central spindle and the contractile ring during Drosophila cytokinesis. Genes Dev. 12, 396–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose, K., Kawashima, T., Iwamoto, I., Nosaka, T., and Kitamura, T. (2001) MgcRacGAP is involved in cytokinesis through associating with mitotic spindle and midbody. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 5821–5828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantsch-Plunger, V., Gönczy, P., Romano, A., Schnabel, H., Hamill, D., Schnabel, R., Hyman, A., and Glotzer, M. (2000). CYK-4, a Rho family GTPase activating protein (GAP) required for central spindle formation and cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 149, 1391–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama, R., Gustus, C., Terrada, Y., Uetake, Y., and Matuliene, J. (2002). CHO1, a mammalian kinein-like protein, interacts with F-actin and is involved in the terminal phase of cytokinesis, J. Cell Biol. 156, 783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuliene, J., and Kuriyama, R. (2002). Kinesin like protein CHO1 is required for the formation of midbody matrix and the completion of cytokinesis in mammalian cells Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 1832–1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meluh, P., and Rose, M. (1990). kar-3, a kinesin-related gene required for yeast nuclear fusion. Cell 60, 1029–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minestrini, G. (2001). Pavarotti KLP: Linking the Actomyosin Cytoskeleton to Microtubules in Drosophila melanogaster. Ph.D. Thesis. Dundee, Scotland: University of Dundee.

- Minestrini, G., Máthé, E., and Glover, D.M. (2002). Domains of the Pavarotti kinesin-like protein that direct its subcellular distribution: effects of mislocalisation on the tubulin and actin cytoskeleton during Drosophila oogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 115, 725–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima, M., Kaitna, S., and Glotzer, M. (2002). Central spindle assembly and cytokinesis require a kinesin-like protein/RhoGAP complex with microtubule bundling activity. Dev. Cell 2, 41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nislow, C., V.A., L., Kuriyama, R., and McIntosh, J.R. (1992). A plus end directed motor enzyme that moves antiparallel microtubules in vitro and localizes to the interzone of mitotic spindles. Nature 359, 543–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesacreta, T.C., Byers, T.J., Dubreuil, R., Kiehart, D.P., and Branton, D. (1989). Drosophila spectrin: the membrane skeleton during embryogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 108, 1697–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers, J., Bossinger, O., Rose, D., Strome, S., and Saxton, W.A. (1998). A nematode kinesin required for cleavage furrow advancement. Curr. Biol. 8, 1133–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokopenko, S.N., Brumby, A., O'Keefe, L., Prior, L., He, Y., Saint, R., and Bellen, H.J. (1999). A putative exchange factor for Rho1 GTPase is required for initiation of cytokinesis in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 13, 2301–2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raich, W.B., Moran, A.N., Rothman, J.H., and Hardin, J. (1998). Cytokinesis and midzone microtubule organization in Caenorhabditis elegans require the kinesin-like protein ZEN-4. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 2037–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorth, P. (1998). Gal4 in the Drosophila female germline. Mech. Dev. 78, 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellitto, C., and Kuriyama, R. (1988). Distribution of a matrix component of the midbody during the cell cycle in Chinese Hamster Ovary cells. J. Cell Biol. 106, 431–439. 162–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somers, W.G., and Saint, R. (2003). A RhoGEF and Rho family GTPase-activating protein complex links the contractile ring to cortical microtubules at the onset of cytokinesis. Dev. Cell. 4, 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafstrom, J.P., and Staehelin, L.A. (1984). Dynamics of the nuclear envelope and of nuclear pore complexes during mitosis in the Drosophila embryo. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 34, 179–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumoto, T., Xie, X., Blumenthal, R., Okamoto, I., and Miki, T. (1999). Human ECT2 is an exchange factor for Rho GTPases, phosphorylated in G2/M phases, and involved in cytokinesis. J. Cell Biol. 147, 921–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warn, R.M. (1986). The cytoskeleton of the early Drosophila embryo. J. Cell Sci. Suppl. 5, 311–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warn, R.M., and Robert-Nicoud, M. (1990). F-actin organization during the cellularization of the Drosophila embryo as revealed with a confocal laser scanning microscope. J. Cell Sci. 96, 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wordeman, L., Wagenbach, M., and Manley, T. (1999). Mutations in the ATP-binding domain affect the sub cellular distribution of mitotic centromere-associated kinesin (MCAK). Cell Biol. Int. 23, 275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, P.E., Pesacreta, T.C., and Kiehart, D.P. (1991). Dynamic changes in the distribution of cytoplasmic myosin during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development 111, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalokar, M., and Erk, I. (1976). Division and migration of nuclei during early embryogenesis of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Microsc. Biol. Cell. 25, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.