Abstract

Recent studies have documented the importance of Niemann Pick C1-like 1 protein (NPC1L1), a putative physiological target of the drug ezetimibe, in mediating intestinal cholesterol absorption. However, whether NPC1L1 is the high affinity cholesterol binding protein on intestinal brush border membranes is still controversial. In this study, brush border membrane vesicles (BBMV) from wild type and NPC1L1−/− mice were isolated and assayed for micellar cholesterol binding in the presence or absence of ezetimibe. Results confirmed the loss of the high affinity component of cholesterol binding when wild type BBMV preparations were incubated with antiserum against the class B type 1 scavenger receptor (SR-BI) in the reaction mixture similar to previous studies. Subsequently, second order binding of cholesterol was observed with BBMV from wild type and NPC1L1−/− mice. The inclusion of ezetimibe in these in vitro reaction assays resulted in the loss of the high affinity component of cholesterol interaction. Surprisingly, BBMVs from NPC1L1−/− mice maintained active binding of cholesterol. These results documented that SR-BI, not NPC1L1, is the major protein responsible for the initial high affinity cholesterol ligand binding process in the cholesterol absorption pathway. Additionally, ezetimibe may inhibit BBM cholesterol binding through targets such as SR-BI in addition to its inhibition of NPC1L1.

Keywords: Niemann Pick C1-like 1 protein (NPC1L1), micelle, brush border membrane vesicle (BBMV), cholesterol transport proteins, ezetimibe

1. Introduction

Dietary cholesterol absorption contributes to elevated serum cholesterol, a major causative factor for premature coronary heart disease. Accordingly, widespread studies have been conducted to identify genetic determinants, biochemical elements, and physiochemical properties that regulate the efficiency of intestinal cholesterol absorption [1]. The collective data from these studies show that dietary cholesterol is emulsified with triglycerides, phospholipids, and other fat-soluble nutrients and transported to the intestinal lumen where they are mixed with bile and pancreatic juice. As the triglycerides and phospholipids are hydrolyzed by lipolytic enzymes present in the pancreatic juice, dietary cholesterol moves from the emulsion surface to unilamellar vesicles and then ultimately incorporated into bile salt mixed micelles [2]. The importance of bile salt micellar solubilization of dietary cholesterol for its absorption by enterocytes is best illustrated by the minimal dietary cholesterol absorption observed in mice that are defective in bile acid synthesis [3]. Likewise, defects in bile salt or phospholipid export from the liver to the bile, due to deletion of P-glycoprotein genes, also result in abnormal cholesterol absorption [4].

The mechanism by which micellar cholesterol is taken up by enterocytes is not completely understood. In vitro cell culture studies showed that micellar cholesterol is initially taken up at the apical brush border membranes (BBM) of enterocytes prior to its subsequent transport to the endoplasmic reticulum for esterification and assembly into chylomicrons [5]. Kinetic studies utilizing BBM vesicles (BBMV) and Caco-2 cells as in vitro models of enterocytic cholesterol uptake revealed that the initial step of the cholesterol absorption process is protein-mediated [6–8]. Several publications from Hauser and his colleagues have consistently demonstrated second-order sterol binding kinetics in these models. Importantly, the high affinity component of sterol binding was shown to be sensitive to protease treatments. A protein-facilitated cholesterol absorption hypothesis is further supported by the observations of sterol specificity in intestinal absorption [9] and the inhibitory action by small molecules and drugs such as ezetimibe toward cholesterol absorption [10, 11]. Consistently, the heritability of cholesterol absorption efficiency among inbred strains of mice and in humans, despite the overall wide range (20%–80%), also suggested the participation of specific gene products in cholesterol absorption regulation [1, 12]. These results have prompted many subsequent studies devoted to identifying candidate BBM proteins responsible for mediating the intestinal binding of dietary cholesterol. However, the subject remains contentious at the present time.

Earlier studies have suggested that the class B type 1 scavenger receptor (SR-BI), a lipoprotein receptor that is highly expressed in the apical side of proximal small intestine villus where the bulk of cholesterol absorption takes place [13], is the protein on brush border membrane responsible for the initial step of cholesterol binding by enterocytes [14]. In support of SR-BI being the intestinal cholesterol transporter were studies showing that the expression of SR-BI in CHO cells induces cellular uptake of cholesterol from micellar substrates and that the increase is sensitive to inhibition by the cholesterol absorption inhibitor ezetimibe [15]. Additionally, ezetimibe has been shown to bind SR-BI in a saturable and specific manner [15]. However, despite the strong evidence suggesting that SR-BI is an important mediator of cholesterol absorption and a target of ezetimibe inhibition, its role as a cholesterol transporter in the intestine remains controversial since dietary cholesterol absorption by mice lacking SR-BI is largely unaffected and remains sensitive to ezetimibe inhibition [15, 16].

In more recent studies, Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1) protein has emerged as a key regulator of intestinal cholesterol absorption and a target of ezetimibe inhibition. Mice deficient in NPC1L1 have approximately a 70% reduction in sterol absorption, with the residual being insensitive to ezetimibe [17]. While some reports indicate the location of this protein to be cell surface [17, 18], others describe NPC1L1 as an endosomal protein [19]. More recent studies have confirmed the presence of NPC1L1 in both regions [20, 21], with plasma membrane localization most prominent under cholesterol depleted conditions [21]. Thus, these results implicated NPC1L1 as the ezetimibe-sensitive apical BBM sterol transporter in intestinal enterocytes. This hypothesis was further supported by studies showing increased binding of ezetimibe to the plasma membrane surface of cells transfected with the rat NPC1L1 cDNA [22]. However, these studies did not reveal whether NPC1L1 is the high affinity cholesterol binding protein in intestinal BBM required for the initial step in the cholesterol absorption pathway. The current study prepared BBMV from wild type and NPC1L1-defective mice to ascertain the role of NPC1L1 in mediating cholesterol binding to BBM. Thus, this study examined cholesterol interaction with proteins present on BBMV, particularly SR-BI and NPC1L1, rather than transport or the overall cholesterol uptake process.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

The NPC1L1−/− mice and their wild type littermates were generated as previously described [19], by directly targeting the NPC1L1 gene in a C57BL/6 background, and transferred to the University of Cincinnati where they were bred in house. The NPC1L1 genotype of the progenies was determined by polymerase chain reaction as previously described [19]. All animals were maintained in a temperature- and humidity-controlled room with a 12 hr light and 12 hr dark cycle and had free access to food and water. All animal protocols used in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Cincinnati.

2.2. Brush border membrane vesicle preparation

Ten to 12 week old wild type and NPC1L1−/− mice were fed a rodent chow (LM485; Harlan-Teklad, Madison, WI) with or without 100 mg/kg ezetimibe (Schering Corporation, Kenilworth, NJ) for 2 weeks. The inclusion of ezetimibe in the diet has no effect on food consumption and resulting in the ingestion of 0.3 to 0.4 mg of ezetimibe each day by mice in the treatment group. Intestines were removed from anesthetized mice after a 12 h fasting period. The intestines were flushed with buffered saline (5 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 0.96 mM NaH2PO4, 5.5 mM glucose, 117 mM NaCl, and 5.4 mM KCl) prior to collecting mucosal scraping. Intestinal mucosas were homogenized and BBMV were prepared by the Mg2+ precipitation method [8, 23]. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford asasy kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. Integrity of proteins in the BBMV preparations was analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

2.3. Cholesterol binding assays

The binding of cholesterol in mixed micelles to the BBMV was determined by incubating the combined BBMV from 2 mice with varying concentrations of [14C]cholesterol-containing mixed micelles according to established procedures [8, 24, 25], but at 4°C for 30 min to focus on the initial step of cholesterol absorption and to limit any residual cholesterol trafficking remaining in the BBMV. A stock solution of micellar substrate containing 12.5 µM [14C]cholesterol (180 µCi/µmol), 312.5 µM sodium taurocholate, 125 µM egg PC, 1.875 µM monoacylglycerol, and 31.25 µM oleate was prepared by sonication of the dried lipids after their dissolution in buffer containing 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl. All lipids were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO) and [14C]cholesterol was obtained from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). The stock substrate solution was diluted with the same buffer to appropriate concentrations prior to addition to BBMV (10 µg protein) in the same buffer to initiate the binding reaction in a volume of 100 µL. At the end of the incubation period, the BBMV were separated from the unbound micellar substrates by collection and washing on cellulose acetate membrane filters (0.45 µm) purchased from Sterlitech Corp. (Kent, WA) that had been presoaked with unlabeled mixed micelles that were 160-fold more concentrated than the test substrate used for the reaction. Radioisotope associated with BBMV was quantified by scintillation counting and cholesterol mass was calculated based on the specific radioactivity of the substrate. Specific binding of [14C]cholesterol in micellar substrate to BBMV was measured in duplicate and calculated based on the difference of [14C]cholesterol bound to the BBMV when incubated in the presence or absence of 160-fold excess unlabeled substrate. In selected experiments, BBMV cholesterol binding assays were also performed after a 10 min incubation at room temperature with 20 µM ezetimibe (Sequoia Research Products, Pangbourne, UK) or 1:1000 dilution anti-SR-BI neutralizing antibodies obtained from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO) or as a gift from Dr. Karen F. Kozarsky (GlaxoSmithKline, King of Prussia, PA).

Binding constants were estimated by Scatchard analysis utilizing the Rosenthal graphic model of non-specific binding normalization [26, 27] and confirmed by non-linear regression analysis using SigmaPlot version 9.01 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). The linearity of each of the binding groups was determined by the least square method from triplicate measurements for each data point in each experiment. The resulting regressions from different test groups within each experiment were statistically compared utilizing analysis of covariance.

2.4. Immunoblot assays

Ten µg of BBMV protein was resolved by 4–20% SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and immunoblotted with antibodies against mouse SR-BI (NB400-101, Novus Biologicals), CD36 (ABM-5525, Cascade Bioscience, Winchester, MA), or NPC1L1 (kind gift of Dr. Helen Hobbs, University of Texas Southwestern Medical School). Protein loading and integrity was verified by Ponceau S staining. Immunoreactive proteins were detected using goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and then visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

3. Results

3.1. Micellar cholesterol binding to intestinal BBMV from wild type mice

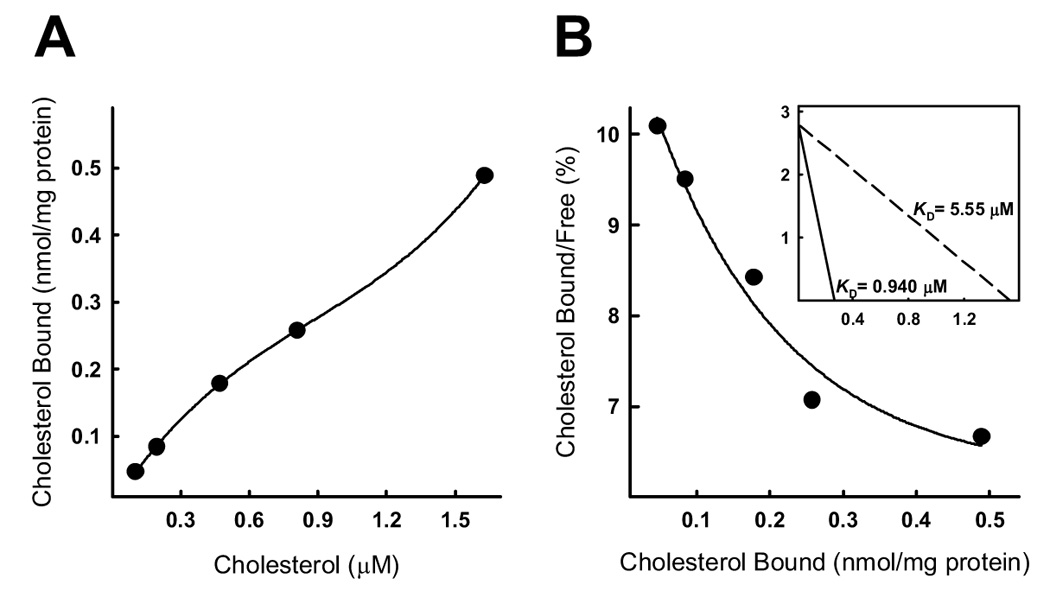

Cholesterol absorption is a multi-step process. Whether NPC1L1 participates in the first step of the cholesterol absorption process, namely the binding of cholesterol in mixed bile salt micelles to proteins in the BBM, is still controversial. To address this issue, BBMV were prepared from mouse intestine and the binding of cholesterol from mixed bile salt micelles were measured by adding various concentrations of mixed micelles containing [14C]cholesterol to a standard amount of BBMV [8, 23]. Specific binding of [14C]cholesterol by the BBMV, after subtracting the nonspecific association observed in the presence of excess unlabeled cholesterol-containing micelles, revealed a curvilinear reaction (Fig. 1A). Scatchard analysis of the results also reveals curvilinear response, with a steeper high affinity binding slope observed at low cholesterol concentrations and a low affinity component asymptotically approaching the passive cholesterol binding slope observed at higher cholesterol concentrations (Fig. 1B). These Scatchard plots were used to generate binding constant estimates for the high affinity binding and low affinity binding groups (Fig. 1B, inset). The binding constants generated by this in vitro model of cholesterol absorption, with a high affinity KD of 0.940 µM for BBMV isolated from control mice, are consistent with physiological concentrations of cholesterol found in the lumen of mice.

Fig. 1.

Micellar cholesterol binding to BBMV isolated from the small intestines of wild type mice. BBMV associated with 10 µg of protein from two wild type mice were incubated with various concentrations of bile salt mixed micelles containing [14C]cholesterol for 30 min at 4°C. Panel A shows concentration-dependent cholesterol binding to BBMV from wild type mice. The data represent representative of three independent experiments using BBMV preparations from different animals. Each data point represents the combined BBMV from 2 animals. Panel B shows Scatchard analysis of the binding data. Shown in the inset are linear representations of the high and low components of the binding curves with the estimated binding affinities (KD).

3.2. Ezetimibe inhibits high affinity binding of micellar cholesterol binding to intestinal BBMV

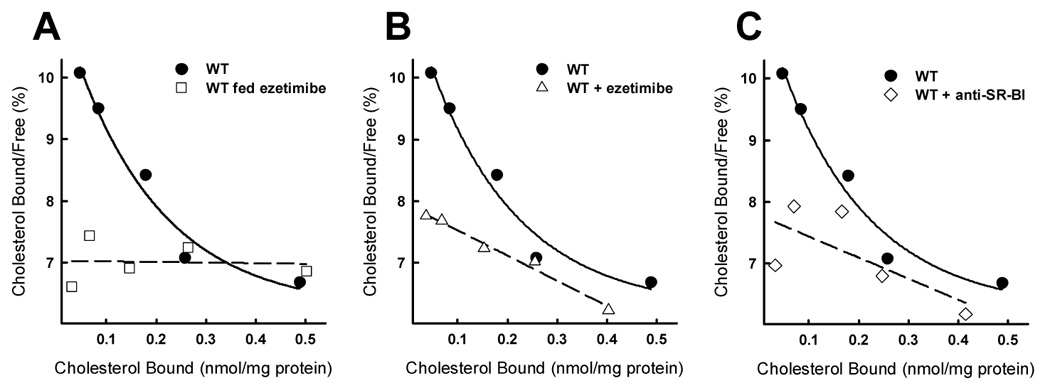

The cholesterol absorption inhibitor ezetimibe has been shown to associate with membrane proteins in BBMV [22]. Therefore, we measured cholesterol binding to BBMV isolated from wild type mice fed ezetimibe mixed with chow for two weeks. Results showed that cholesterol binding to these BBMV can be fitted into a linear Scatchard plot instead of the curvilinear characteristics of the cholesterol binding to BBMV from control mice (Fig. 2A). The loss of curvature in the resulting Scatchard plot represents an abrogation of high affinity cholesterol binding in mouse BBMV, presumably due to the presence of ezetimibe in the lumen at the time of intestine collection. As such, cholesterol binding to BBMV isolated from mice fed ezetimibe represents a model estimating the low affinity cholesterol association component and a loss of high affinity, second order cholesterol binding characteristics, similar to that observed after protease treatment of the BBMV [8].

Fig. 2.

Cholesterol binding to BBMV from wild type mice. Panel A shows cholesterol binding to BBMV isolated from wild type mice and wild type mice fed ezetimibe as estimated by Scatchard analysis. Scatchard curves for cholesterol binding to wild type BBMV in the presence of ezetimibe (20 µM) or anti-mouse SR-BI neutralizing antibody are shown as dashed lines in panels B and C. Cholesterol binding to BBMV prepared from wild type (WT) mice is displayed in each of the figures as solid lines. Each data point represents 10 µg of protein from BBMV combined from two mice and representative of 3 or 4 repeats each with fresh BBMV preparations from additional animals.

The abrogation of high affinity cholesterol binding to BBMV isolated from ezetimibe-treated mice indicates that ezetimibe may interfere directly with cholesterol binding to protein(s) on the BBMV. Alternatively, ezetimibe treatment in vivo may decrease the expression of the cholesterol binding protein by enterocytes resulting in BBMV lacking the high affinity cholesterol binding component. To test these possibilities, BBMV were isolated from control mice without ezetimibe treatment and then tested for cholesterol binding capabilities in the presence or absence of ezetimibe. Results indicated that the high affinity component of the cholesterol binding to BBMV from mice fed chow alone was inhibited by prior incubation of the BBMV in vitro with ezetimibe whereas treatment with DMSO alone had no effect (Fig. 2B). Analysis of the binding characteristics confirms that ezetimibe pretreatment decreases the affinity (KD= 9.44 µM) of cholesterol for BBMV by an order of magnitude while feeding the mice ezetimibe completely eliminated the high affinity binding. This difference may be partly explained by the glucuronidation of the drug in vivo, resulting in a more potent inhibitor of cholesterol absorption [11]. Nevertheless, both of these experiments showed that ezetimibe directly inhibits the high affinity cholesterol binding site in BBMV.

3.3. Importance of SR-BI in intestinal BBMV for high affinity micellar cholesterol binding

Previous studies have demonstrated that SR-BI inactivation by treatment with anti-SR-BI blocking antibody [25] or the absence of SR-BI [28] lessens cholesterol binding in BBMV. These results were confirmed in our current study by showing that preincubation of BBMV with neutralizing anti-mouse SR-BI antibody decreased the high affinity component of cholesterol binding by BBMV (Fig. 2C). The effects of non-specific antiserum on BBMV cholesterol binding were tested and found to be negligible. The binding affinity (KD= 4.49 µM) of cholesterol binding to BBMV treated with anti-SR-BI is similar to that of BBMV pretreated with ezetimibe, suggesting that ezetimibe inhibition of protein-mediated cholesterol binding may include SR-BI as a target.

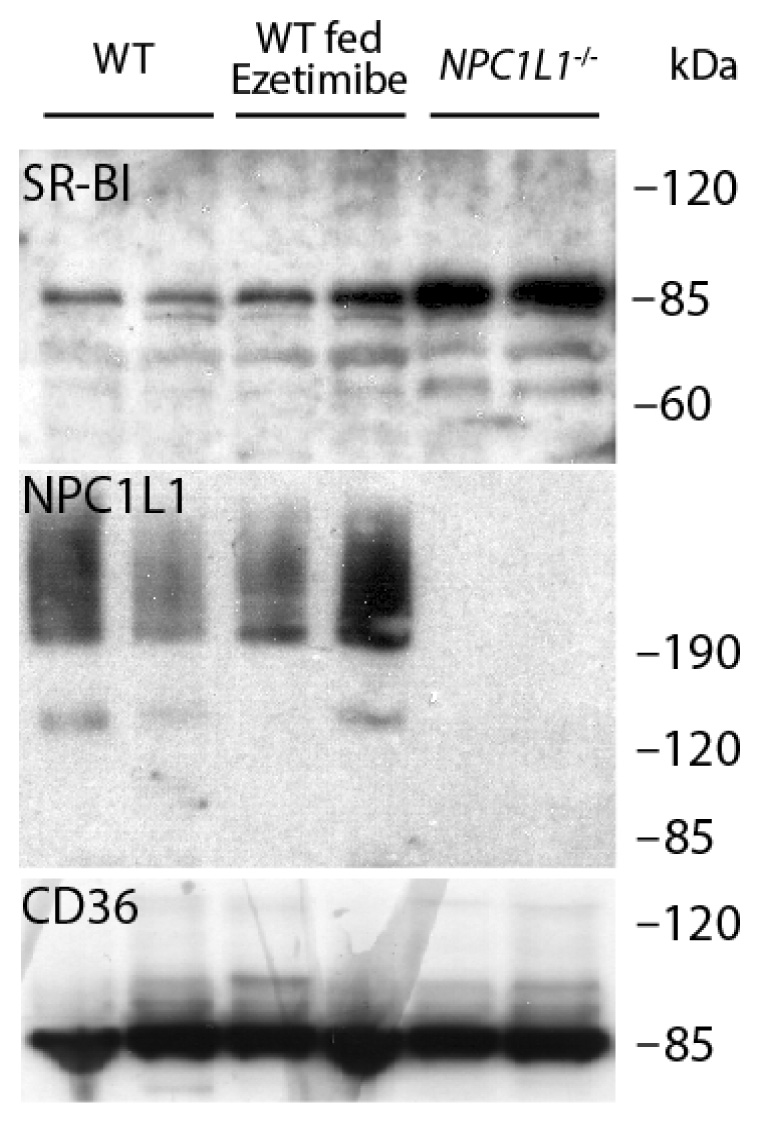

In view of prior studies implicating NPC1L1 as well as SR-BI as targets of ezetimibe important for its inhibition of cholesterol absorption, the relative abundance of these two proteins in BBMV used for the cholesterol binding experiments were determined. For these measurements, BBMV derived from mouse intestinal mucosa were evaluated for the expression of NPC1L1 and SR-BI by immunoblot analysis. SR-BI levels were unchanged by ezetimibe feeding (Fig. 3). However, the amount of SR-BI in BBMV increased from NPC1L1−/− mice relative to those made from wild type mice or wild type mice fed ezetimibe. Consistent with the proposed role of NPC1L1 in sterol absorption at the level of the BBM [18], NPC1L1 was detected in both in BBMV preparations from wild type mice and ezetimibe-treated wild type mice. This suggests that NPC1L1 levels are unchanged in BBM despite decreased cholesterol absorption via ezetimibe treatment. As expected, NPC1L1 was not detected in BBMV made from the small intestine of NPC1L1−/− mice. The quality and consistency of these BBMV preparations were documented by the presence of similar amounts of CD36, another class B scavenger receptor proposed to mediate long-chained fatty acid absorption in the lumen of the intestine [29, 30], in BBMV obtained from control mice, with or without ezetimibe treatment, and from NPC1L1−/− mice.

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis of NPC1L1, SR-BI, and CD36 in BBMV isolated from the small intestine of mice. BBMV were prepared from small intestine mucosa collected from two wild type (WT) mice, two WT mice fed ezetimibe, and two NPC1L1−/− mice. SR-BI, NPC1L1, and CD36 were detected by immunoblot analysis with their respective antibodies and identified as 83-kDa, ~200-kDa, and 86-kDa proteins, respectively.

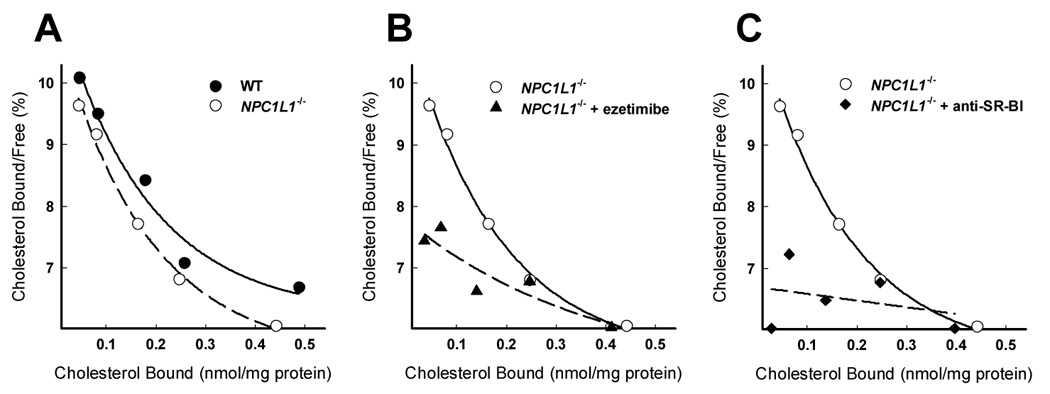

3.4. Micellar cholesterol binding to BBMV from wild type and NPC1L1 knockout mice

The potential direct involvement of NPC1L1 as the cholesterol binding protein responsible for the initial step of the cholesterol absorption process was explored by comparing the binding characteristics of cholesterol in mixed bile salt micelles to BBMV isolated from NPC1L1+/+ and NPC1L1−/− mice. Scatchard analysis of BBMV cholesterol binding reveals that high affinity cholesterol binding was unaffected by the presence or absence of NPC1L1 (Fig. 4A). The cholesterol binding behavior of BBMV from NPC1L1−/− mice was similar to BBMV from wild type mice as denoted by the almost superimposable data points from both groups of mice. Further, the high affinity binding constant estimates of BBMV from wild type (KD= 0.940 µM) and NPC1L1−/− mice (KD= 0.684 µM) were very similar. Additionally, cholesterol association with BBMV from NPC1L1−/− mice was sensitive to ezetimibe treatment (Fig. 4B). The Scatchard plot displays a minute upward curve at lower concentrations of cholesterol, suggesting a remnant of high affinity binding, but is too low to determine associated binding constants. Trace high affinity binding suggests another target for ezetimibe in the BBMV preparations. Additionally, pretreatment of BBMV from NPC1L1−/− mice with anti-SR-BI antiserum also reduced cholesterol binding to a virtually flat Scatchard curvilinear plot with non-detectable affinity constants (Fig. 4C). Taken together, these data suggest that NPC1L1 does not mediate initial association of cholesterol by BBM and that this process is achieved by other ezetimibe sensitive proteins such as SR-BI.

Fig. 4.

Scatchard analsyis of cholesterol binding to BBMV from wild type (WT) and NPC1L1−/− mice. Cholesterol binding assays were performed with BBMV from untreated NPC1L1−/− mice (A), BBMV from NPC1L1−/− mice treated with ezetimibe (20 µM) (B), and BBMV from NPC1L1−/− mice treated with anti-SR-BI neutralizing antiserum (C). The cholesterol binding curve of BBMV from wild type (WT) mice from Figure 2 is included in A (solid line) for comparison to cholesterol binding of BBMV from NPC1L1−/− mice (hatched line). Cholesterol binding to BBMV from NPC1L1−/− mice is repeated in B and C (solid line) for comparison to the estimated cholesterol association to BBMV from NPC1L1−/− mice treated with ezetimibe or anti-SR-BI neutralizing antiserum (hatched line), respectively. Each data point represents 10 µg of protein from BBMV combined from two mice and representative of 3 or 4 independent repeats each with fresh BBMV preparations from additional animals.

4. Discussion

The current study used BBMV as an in vitro model to identify the protein responsible for cholesterol binding to protein(s) on the BBM surface, which is the first step of the intestinal cholesterol absorption process. Results showed that both NPC1L1 and SR-BI, the two proteins that have previously been implicated as the ezetimibe-sensitive cholesterol transporter in intestine, were present in intestinal BBMV preparations of wild type mice. Cholesterol binding by these BBMV displayed second order characteristics with a high affinity/low capacity and a low affinity/high capacity component. The high affinity component of cholesterol binding, which has previously been shown to be a protein-mediated process [6–8], can be inhibited by prior treatment of the mice with ezetimibe or by inclusion of ezetimibe in the in vitro cholesterol binding assay. These observations are consistent with the interpretation that ezetimibe inhibits cholesterol absorption by interfering with cholesterol binding activity at the BBM.

A surprising finding of the current study is that BBMV isolated from NPC1L1−/− mice also displayed both high affinity and low affinity components of cholesterol binding similar to those observed with BBMV from NPC1L1+/+ mice. Moreover, the high affinity component of micellar cholesterol binding by BBMV of NPC1L1−/− mice remained sensitive to ezetimibe inhibition. Previous studies have shown that mice deficient in NPC1L1 absorbed cholesterol poorly and the residual cholesterol absorption in the NPC1L1−/− mice was no longer sensitive to ezetimibe inhibition [17, 31]. These earlier results were interpreted to indicate that NPC1L1 is the ezetimibe-sensitive cholesterol transporter in intestinal BBM. However, our results showing that BBMV from NPC1L1−/− mice display an ezetimibe-sensitive cholesterol binding mechanism argue against the role of NPC1L1 as the principal ezetimibe-sensitive cholesterol binder on BBM surface. It is important to note, however, that our observations of similar cholesterol association with BBMV from NPC1L1+/+ and NPC1L1−/− mice, do not dispute the importance of NPC1L1 in overall cholesterol absorption because cholesterol absorption in these NPC1L1−/− mice was dramatically reduced [17, 19], The data reported by Mathur et al. examining the effect of docosahexaenoic acid on cholesterol trafficking from plasma membrane suggested that NPC1L1 probably participates in cholesterol absorption at the BBM subsequent to cholesterol binding to the membrane [32]. These authors further speculated that the NPC1L1 cholesterol-sensing domain may serve to detect cholesterol levels in rafts to regulate cholesterol influx from these specialized domains. Our data showing that NPC1L1 is present in BBMV but is not essential for its cholesterol binding activity, and the previous report of aberrant intracellular cholesterol transport in cells lacking NPC1L1 [19, 33], are consistent with this hypothesis.

The relationship between NPC1L1 and ezetimibe inhibition of cholesterol absorption has been explored extensively during the past year. Although at first glance results from these earlier reports suggesting NPC1L1 is the ezetimibe-sensitive cholesterol transporter on the cell surface may appear to contradict results reported in the current study, a closer examination of the data revealed that they are not necessarily inconsistent or mutually exclusive. For example, in the study by Garcia-Calvo et al, comparing HEK293 cells with or without NPC1L1 expression, the data showed direct ezetimibe interaction with NPC1L1 [22], That study also revealed direct ezetimibe binding to intestinal BBMV [22], thus implicating NPC1L1 as a membrane target of ezetimibe inhibition. However, their study failed to reveal whether NPC1L1 expressed in HEK293 cells can promote cholesterol binding and uptake from micellar substrates. In fact, the same investigators have reported previously that the intestinal cholesterol transport properties cannot be reconstituted simply by transfecting nonenterocytic cells with NPC1L1 [17, 18]. In a more recent study, Yu et al showed that NPC1L1 cDNA transfected into McArdle RH7777 rat hepatoma cells increased cholesterol uptake when cells were depleted of cholesterol [21]. Importantly, the NPC1L1-mediated increase in cholesterol uptake by cholesterol-depleted NPC1L1-expressing hepatoma cells was shown to be sensitive to ezetimibe inhibition [21]. These authors proposed that cholesterol depletion promotes NPC1L1 translocation from an intracellular compartment to the cell surface to facilitate cholesterol uptake. However, this latter study did not show whether translocated or cell surface NPC1L1 directly binds to cholesterol from the incubation medium or acts in concert with another cholesterol-binding protein on the cell surface membrane to facilitate cholesterol uptake. Thus, while these two studies clearly established the importance of NPC1L1 in facilitating overall cellular cholesterol uptake and that the NPC1L1 pathway is sensitive to ezetimibe inhibition, whether the presence of other cell surface proteins is required for NPC1L1-mediated translocation of cholesterol to the cell interior remains uncertain. In fact, both Garcia-Calvo et al [22]and Iyer et al [18] suggested that NPC1L1 may function within a multiprotein complex in facilitating the multi-step process of cholesterol transport from the external micellar sources to internal cholesterol pool(s).

The current study revealed that SR-BI may be another protein in this multiprotein complex required for cholesterol absorption. Our results showing anti-SR-BI neutralizing antibodies inhibited high affinity cholesterol binding by BBMV from both NPC1L1+/+ and NPC1L1−/− mice, thus confirming previous reports that SR-BI is responsible for the high affinity cholesterol binding properties of BBMV [13, 25, 28]. This current study builds on these observations and showed that the high affinity cholesterol binding by BBMV from NPC1L1+/+ and from NPC1L1−/− mice were both sensitive to ezetimibe inhibition. These results are also consistent with previous studies demonstrating ezetimibe inhibition of cholesterol uptake by SR-BI transfected CHO cells [15]. Taken together, these data suggest that NPC1L1 works together with other cell surface proteins, such as SR-BI, in effecting cholesterol uptake from micelles in the gut. For example, in cells not expressing SR-BI such as HEK293 and COS-1 [34, 35], transfection of NPC1L1 did not result in increased cholesterol uptake [17, 22]. In contrast, SR-BI expressing cells such as the McArdle RH7777 hepatoma cells displayed increased cholesterol uptake after NPC1L1 transfection, especially under cholesterol-depleted conditions when SR-BI expression is presumably induced [21, 36].

Our results and previous studies showing SR-BI participation in the cholesterol absorption pathway as the high affinity cholesterol binding protein in BBMV are also consistent with studies demonstrating accelerated lipid absorption in mice overexpressing intestinal SR-BI [37]. However, these results are in striking contrast to the observation of unaltered cholesterol absorption efficiency in SR-BI-defective mice [15, 16]. Moreover, cholesterol absorption in SR-BI−/− mice was also sensitive to ezetimibe inhibition [15, 28]. Thus, other proteins in the BBMV may serve a compensatory role in mediating cholesterol binding in the absence of SR-BI, and may also act in concert with NPC1L1 to facilitate intestinal cholesterol absorption and transport in an ezetimibe-sensitive manner. The other class B scavenger receptor, CD36, is also present in intestinal BBMV and may serve this compensatory function. The ability of ezetimibe to inhibit CD36-mediated cellular binding of cholesterol from micellar substrates [28] is consistent with this possibility. Other ezetimibe binding proteins, such as CD13 or the caveolin-1/annexin-2 complex [38], may also serve a compensatory role to SR-BI or act in a multiprotein complex in promoting cholesterol absorption. In summary, the current study along with results reported previously by others demonstrate that, although NPC1L1 is present in BBM of intestine and its activity is critically important for cholesterol absorption, SR-BI is the major protein responsible for the high affinity cholesterol binding activity in intestinal BBMV.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lisa Camarota and Josh Basford for superb technical assistance and Dr. Dean Gilham for helpful discussions and advice. This work was supported by Grant DK67416 from the National Institutes of Health (to D.Y.H.) and Postdoctoral Fellowship 0525340B from the Ohio Affiliates of the American Heart Association (to E.D.L.).

The abbreviations used are

- BBM

brush border membranes

- BBMV

brush border membrane vesicles

- NPC1L1

Niemann Pick C1-like 1

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hui DY, Howles PN. Molecular mechanisms of cholesterol absorption and transport. Sem. Cell Develop. Biol. 2005;16:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernell O, Staggers JE, Carey MC. Physical-Chemical behavior of dietary and biliary lipids during intestinal digestion and absorption. Biochemistry. 1990;29:2041–2056. doi: 10.1021/bi00460a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishibashi S, Schwarz M, Frykman PK, Herz J, Russell DW. Disruption of cholesterol 7-alpha hydroxylase gene in mice. I. Postnatal lethality reversed by bile acid and vitamin supplementation. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:18017–18023. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.18017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voshol PJ, Havinga R, Wolters H, Ottenhoff R, Princen HMG, Oude Elferink RPJ, Groen AK, Kuipers F. Reduced plasma cholesterol and increased fecal sterol loss in multidrug resistance gene 2 P-glycoprotein-deficient mice. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1024–1034. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70323-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field FJ, Born E, Mathur SN. Triacylglycerol-rich lipoprotein cholesterol is derived from the plasma membrane in Caco-2 cells. J. Lipid Res. 1995;36:2651–2660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Compassi S, Werder M, Weber FE, Boffelli D, Hauser H, Schulthess G. Comparison of cholesterol and sitosterol uptake in different brush border membrane models. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6643–6652. doi: 10.1021/bi9620666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulthess G, Compassi S, Boffelli D, Werder M, Weber FE, Hauser H. A comparative study of sterol absorption in different small intestinal brush border membrane models. J. Lipid Res. 1996;37:2405–2419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thurnhofer H, Hauser H. Uptake of cholesterol by small intestinal brush border membrane is protein-mediated. Biochemistry. 1990;29:2142–2148. doi: 10.1021/bi00460a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glover J, Morton RA. The absorption and metabolism of sterols. Br. Med. Bull. 1958;14:226–233. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a069688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salisbury BG, Davis HR, Burrier RE, Burnett DA, Boykow G, Caplen MA, Clemmons AL, Compton DS, Hoos LM, McGregor DG, Schnitzer-Polokoff R, Smith AA, Weig BC, Zilli DL, Clader JW, Sybertz EJ. Hypocholesterolemic activity of a novel inhibitor of cholesterol absorption, SCH 48461. Atherosclerosis. 1995;115:45–63. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)05499-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Heek M, France CF, Compton DS, Mcleod RL, Yumibe NP, Alton KB, Sybertz EJ, Davis HR., Jr In Vivo Metabolism-Based Discovery of a Potent Cholesterol Absorption Inhibitor, SCH58235, in the Rat and Rhesus Monkey through the Identification of the Active Metabolites of SCH48461. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;283:157–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang DQH, Paigen B, Carey MC. Genetic factors at the enterocyte level account for variations in intestinal cholesterol absorption efficiency among inbred strains of mice. J. Lipid Res. 2001;42:1820–1830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauser H, Dyer JH, Nandy A, Vega MA, Werder M, Bieliauskaite E, Weber FE, Compassi S, Gemperli A, Boffelli D, Wehrli E, Schulthess G, Phillips MC. Identification of a receptor mediating absorption of dietary cholesterol in the intestine. Biochemistry. 1998;37:17843–17850. doi: 10.1021/bi982404y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai SF, Kirby RJ, Howles PN, Hui DY. Differentiation-dependent expression and localization of the class B type I scavenger receptor in intestine. J. Lipid Res. 2001;42:902–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altmann SW, Davis HR, Yao X, Laverty M, Compton DS, Zhu L-j, Crona JH, Caplen MA, Hoos LM, Tetzloff G, Priestley T, Burnett DA, Strader CD, Graziano MP. The identification of intestinal scavenger receptor B, type (SR-BI) by expression cloning and its role in cholesterol absorption. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1580:77–93. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(01)00190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mardones P, Quinones V, Amigo L, Moreno M, Miquel JF, Schwarz M, Miettinen HE, Trigatti B, Krieger M, VanPatten S, Cohen DE, Rigotti A. Hepatic cholesterol and bile acid metabolism and intestinal cholesterol absorption in scavenger receptor class B type I-deficient mice. J. Lipid Res. 2001;42:170–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altmann SW, Davis HR, Zhu L-J, Yao X, Hoos LM, Tetzloff G, Lyer SPN, Maguire M, Golovko A, Zeng M, Wang L, Murgolo N, Graziano MP. Niemann-Pick C1 like 1 protein is critical for intestinal cholesterol absorption. Science. 2004;303:1201–1204. doi: 10.1126/science.1093131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iyer SPN, Yao X, Crona JH, Hoos LM, Tetzloff G, Davis HR, Graziano MP, Altmann SW. Characterization of the putative native and recombinant rat sterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 (NPC1L1) protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1722:282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies JP, Scott C, Oishi K, Liapis A, Ioannou YA. Inactivation of NPC1L1 Causes Multiple Lipid Transport Defects and Protects against Diet-induced Hypercholesterolemia. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:12710–12720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sane AT, Sinnett D, Delvin E, Bendayan M, Marcil V, Menard D, Beaulieu JF, Levy E. Localization and role of NPC1L1 in cholesterol absorption in human intestine. J. Lipid Res. 2006;47:2112–2120. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600174-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu L, Bharadwaj S, Brown JM, Ma Y, Du W, Davis MA, Michaely P, Liu P, Willingham MC, Rudel LL. Cholesterol-regulated translocation of Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 to the cell surface facilitates free cholesterol uptake. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:6616–6624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511123200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Calvo M, Lisnock J, Bull HG, Hawes BE, Burnett DA, Braun MP, Crona JH, Davis HR, Jr, Dean DC, Detmers PA, Graziano MP, Hughes M, MacIntyre DE, Ogawa A, O'Neill KA, Iyer SPN, Shevell DE, Smith MM, Tang YS, Makarewicz AM, Ujjainwalla F, Altmann SW, Chapman KT, Thornberry NA. The target of ezetimibe is Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 (NPC1L1) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:8132–8137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500269102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauser H, Howell K, Dawson RMC, Bowyer DE. Rabbit small intestinal brush border membrane. Preparation and lipid composition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1980;602:567–577. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(80)90335-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulthess G, Lipka G, Compassi S, Boffelli D, Weber FE, Paltauf F, Hauser H. Absorption of monoacylglycerols by small intestinal brush border membrane. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4500–4508. doi: 10.1021/bi00181a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Werder M, Han C-H, Wehrli E, Bimmler D, Schulthess G, Hauser H. Role of scavenger receptors SR-BI and CD36 in selective sterol uptake in the small intestine. Biochemistry. 2001;40:11643–11650. doi: 10.1021/bi0109820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scatchard G. The attractions of proteins for small molecules and ions. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1949;51:660–672. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenthal HE. A graphic method for the determination and presentation of binding parameters in a complex system. Anal. Biochem. 1967;20:525–532. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(67)90297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Bennekum AM, Werder M, Thuahnai ST, Han C-H, Duong P, Williams DL, Wettstein P, Schulthess G, Phillips MC, Hauser H. Class B scavenger receptor-mediated intestinal absorption of dietary beta-carotene and cholesterol. Biochemistry. 2005;44:4517–4525. doi: 10.1021/bi0484320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen M, Yang Y, Braunstein E, Georgeson KE, Harmon CM. Gut expression and regulation of FAT/CD36: possible role in fatty acid transport in rat enterocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 2001;281:E916–E923. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.5.E916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drover VA, Ajmal M, Nassir F, Davidson NO, Nauli AM, Sahoo D, Tso P, Abumrad NA. CD36 deficiency impairs intestinal lipid secretion and clearance of chylomicrons from the blood. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1290–1297. doi: 10.1172/JCI21514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis HR, Jr, Zhu L-j, Hoos LM, Tetzloff G, Maguire M, Liu J, Yao X, Iyer SPN, Lam M-H, Lund EG, Detmers PA, Graziano MP, Altmann SW. Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 (NPC1L1) is the intestinal phytosterol and cholesterol transporter and a key modulator of whole-body cholesterol homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:33586–33592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405817200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathur SN, Watt KR, Field FJ. Regulation of intestinal NPC1L1 expression by dietary fish oil and docosahexaenoic acid. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48:395–404. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600325-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davies JP, Ioannou YA. The role of the Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 protein in the subcellular transport of multiple lipids and their homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2006;17:221–226. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000226112.12684.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kellner-Weibel G, de la Llera-Moya M, Connelly MA, Stoudt G, Christian AE, Haynes MP, Williams DL, Rothblat GH. Expression of scavenger receptor BI in COS-7 cells alters cholesterol content and distribution. Biochemistry. 2000;39:221–229. doi: 10.1021/bi991666c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, Connelly MA, Ostermeyer AG, Chen H-h, Williams DL, Brown DA. Caveolin-1 does not affect SR-BI mediated cholesterol efflux or selective uptake of cholesteryl ester in two cell lines. J. Lipid Res. 2003;44:807–815. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200449-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhainds D, Bourgeois Ph, Bourret G, Huard K, Falstrault L, Brissette L. Localization and regulation of SR-BI in membrane rafts of HepG2 cells. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:3095–3105. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bietrix F, Yan D, Nauze M, Rolland C, Bertrand-Michel J, Comera C, Schaak S, Barbaras R, Groen AK, Perret B, Terce F, Collet X. Accelerated lipid absorption in mice overexpressing intestinal SR-BI. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:7214–7219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508868200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smart EJ, De Rose RA, Farber SA. Annexin 2-caveolin 1 complex is a target of ezetimibe and regulates intestinal cholesterol transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:3450–3455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400441101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]