Abstract

The induction of immune tolerance is essential for the maintenance of immune homeostasis and to limit the occurrence of exacerbated inflammatory and autoimmune conditions. Multiple mechanisms act together to ensure self-tolerance, including central clonal deletion, cytokine deviation and induction of regulatory T cells. Identifying the factors that regulate these processes is crucial for the development of new therapies of autoimmune diseases and transplantation. The vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) is a well-characterized endogenous anti-inflammatory neuropeptide with therapeutic potential for a variety of immune disorders. Here we examine the latest research findings, which indicate that VIP participates in maintaining immune tolerance in two distinct ways: by regulating the balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors, and by inducing the emergence of regulatory T cells with suppressive activity against autoreactive T-cell effectors.

Keywords: Inflammation, Autoimmunity, Regulatory T cells, Tolerance, Neuroimmunology, Neuropeptide

1. Immune tolerance versus autoimmunity

Protection against infection is fundamental to the survival of all complex organisms. The successful elimination of most pathogens requires crosstalk between the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system. The innate immune system recognizes pathogen-associated molecular signatures through pattern-recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which induce the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and free radicals, the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the site of infection, and the lysis of infected host cells by natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Although critical for the successful elimination of pathogens, the inflammatory process needs to be limited, since an excessive response can result in severe inflammation and collateral tissue damage. Inflammatory responses also increase the risk of inducing harmful autoimmune responses, where immune cells and the molecules that respond to pathogen-derived antigens also react to self-antigens. The ability to safely induce antigen-specific long-term tolerance has long been the “holy grail” for the control of autoreactive T cells during autoimmune diseases and in obtaining transplantation tolerance. Inflammatory responses are self-limited by anti-inflammatory mediators secreted by the host innate immune system, thus the ability to control an inflammatory state depends on the local balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory factors. However, recent evidence indicates that the adaptive immune system might also help to maintain immune tolerance during infection-induced immunopathology [73].

In addition to central clonal deletion of self-reactive T cells in the thymus, the generation of antigen-specific regulatory T cells (Treg) plays a critical role in the induction of peripheral tolerance [5,83]. Thus unbalances between pro-inflammatory factors and anti-inflammatory cytokines, as well as between autoreactive/inflammatory T helper 1 (TH1) cells and regulatory/suppressive T cells, are central to the occurrence of inflammatory disorders and autoimmune diseases (Figure 1).

Figure 1. VIP restores tolerance in autoimmune disorders by acting at multiple levels.

Loss of immune tolerance compromises immune homeostasis and results in the onset of autoimmune disorders (Crohn’s disease is shown as an example). The initial stages of inflammatory bowel disease involve multiple steps that can be divided into two main phases: early events associated with initiation and establishment of autoimmunity to components of the colonic mucosa, and later events associated with the evolving immune and destructive inflammatory responses. Progression of the autoimmune response involves the development of self-reactive T helper 1 (TH1) cells in Peyer’s patches and mesenteric lymph nodes, their entry into the colonic mucosa, release of proinflammatory cytokines (tumor-necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and interferon-γ (IFNγ)) and chemokines and subsequent recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells (macrophages and neutrophils). Inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines, nitric oxide (NO) and free radicals, which are produced by infiltrating cells and resident lamina propria cells, have a crucial role in the destruction of the intestinal epithelium and mucosa. In addition, the TH1-mediated production of IgG2 autoantibodies, which activate complement and neutrophils, contributes to autoimmune pathology. Regulatory T cells are key players in maintaining tolerance by their suppression of self-reactive TH1 cells through a mechanism that involves production of interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ), and/or expression of the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 (CTLA4). VIP induces immune tolerance and inhibits the autoimmune response through several non-excluding mechanisms. A) VIP decreases TH1-cell functions directly on differentiating T cells, or indirectly via dendritic cell (DC). As a consequence, inflammatory and autoimmune responses are impaired because of reduced infiltration/activation of neutrophils and macrophages by IFNγ and the abolition of the production of complement-fixing IgG2a antibodies. B) VIP inhibits the production of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and free radicals by macrophages and resident cells. In addition, it impairs the costimulatory activity of macrophages on effector T cells, inhibiting subsequent clonal expansion. This avoids the inflammatory response and its cytotoxic effects against intestinal mucosa and epithelium. C) VIP induces the new generation of peripheral Treg cells that suppress autoreactive T cells activation through a mechanism that involves the production of interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ), and/or expression of the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 (CTLA4). In addition, VIP indirectly generates Treg cells through the differentiation of tolerogenic DCs. Arrows indicate a stimulatory effect. Back-crossed lines indicate an inhibitory effect.

Therefore, from a therapeutic point of view, in order to restore self-tolerance it is critical to identify agents able to target both unbalanced inflammatory and autoreactive responses. It has been speculated that endogenous factors might be produced by immune cells in order to coordinate or limit an ongoing inflammatory/autoimmune response. In an effort to identify such factors, many researchers have concentrated on traditional immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGFβ1) [94]. Meanwhile, others have focused their search on neuropeptides and hormones, classically considered as neuroendocrine mediators, but which are also produced by immune cells, especially under inflammatory conditions [47].

2. Neuroimmune crosstalk and immune tolerance

For many years, the neuroendocrine system and the immune system have been considered as two autonomous networks functioning to maintain a balance between host and environment. According to this view, while the immune system reacts to exposure to bacteria, viruses and trauma, the neuroendocrine system responds to external stimuli such as temperature, pain and stress. However, it has recently become clear that both systems are involved in a variety of essential, coordinated responses to potential threats.

Acting as a “sixth sense”, the immune system can induce the brain to respond to the “danger” of pathogen infection and inflammation, resulting in the orchestration of the febrile response and its subsequent effects on behavior (i.e., sleep and feeding) [4,85]. In contrast, the immune system is regulated by the central nervous system (CNS) in response to environmental stress, either directly via the autonomic nervous system or by way of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. That these two systems function as a closely linked network is supported by the fact that they both communicate using a mutual biochemical language, involving shared ligands such as neuropeptides, hormones, cytokines and their respective receptors [4]. Thus the traditional distinctions between neuropeptides, hormones and immune mediators are harder to define, raising the question of what can actually be considered as immune or neuroendocrine. As such, it is reasonable to think that factors produced by the neuroendocrine system could contribute to the maintenance of immune tolerance. Glucocorticoids and noradrenalin are the classical examples of endogenous immunosuppressive agents produced, by the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system respectively, in response to stress or systemic inflammation [4,85]. Furthermore, a number of neuropeptides and hormones have emerged over recent years as potential candidates for the treatment of the unwanted immune responses, which occur in inflammatory and autoimmune disorders, by restoring immune homeostasis [46,85]. In this review, we will focus on the most recent developments regarding the effects on immune tolerance of the vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), a well-known anti-inflammatory neuropeptide, highlighting the effectiveness of this neuropeptide for the treatment of several immune disorders.

3. VIP, a well-known anti-inflammatory factor

VIP is a 28-aminoacid peptide that was firstly isolated from the gastrointestinal tract for its capacity as a vasodilator [76]. VIP was subsequently identified in the central and peripheral nervous systems, and recognized as a widely distributed neuropeptide, acting as a neurotransmitter in many organs and tissues, including heart, lung, thyroid gland, kidney, immune system, urinary tract and genital organs [77]. The widespread distribution of VIP is consistent with its participation in a wide variety of biological processes including systemic vasodilatation, control of cardiac output, bronchodilatation, hyperglycemia, smooth muscle relaxation, hormonal regulation, analgesia, learning and behavior, and gastric motility. VIP shares structural similarities with other gastrointestinal hormones, such as secretin, glucagon, gastric inhibitory peptide, growth hormone-releasing factor, helodermin and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP). The VIP protein sequence has been well conserved during evolution, suggesting that it performs an important biological role [82].

VIP possesses a number of characteristics that suggest its involvement in immune tolerance. Firstly, VIP is produced by immune cells, mainly TH2 CD4 and type 2 CD8 cells, especially under inflammatory conditions, or following antigenic stimulation [17]. Secondly, VIP exerts its biological actions through various G-protein-coupled receptors (VPAC1, VPAC2 and PAC1), that are expressed in several immune cells, including T cells, macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells (DCs) and neutrophils [36]. Finally, VIP signaling involves the activation of cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) pathway [36], which is considered an immunosuppressive signal [3].

3.1. VIP acts as an anti-inflammatory agent in innate immunity

VIP has been shown to be a potent anti-inflammatory agent both in vitro and in vivo. Mounting evidence indicates that VIP acts via multiple mechanisms to counter inflammatory factors: a) VIP inhibits phagocytic activity, free radical production, adherence and migration of macrophages [12]; b) VIP reduces the production of inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor [TNFα], IL-12, IL-6 and IL-1β) and downregulates the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and the subsequent release of nitric oxide by macrophages, DCs and microglia [33,35-37,55,66,87]; c) VIP limits the release of various chemokines and impairs signaling through chemokine receptors [18,25,36,53,55,72,95]; d) VIP stimulates the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, TGFβ1 and IL-1Ra [34,87]; e) VIP can decrease the co-stimulatory activity of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) toward antigen-specific T cells by downregulating the expression of the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 [38]; and f) by reducing the expression of TLRs and associated molecules [29,46].

The functional importance of VIP as a natural anti-inflammatory factor in vivo has been validated by two recent publications reporting that mice that lack VIP or the PAC1 receptor exhibit higher systemic inflammatory responses and mortality by septic shock than wild-type animals [65,86].

These observations give rise to an obvious question; how does VIP regulate such a plethora of inflammatory and immunomodulatory mediators? The answer may lie in the fact that VIP exerts most of its effects, in the majority of tissues, via the cAMP/PKA pathway, including the downregulation of inflammatory mediators [12,18,25,33,35-37,66]. Several cAMP-inducing agents have been shown to be potent anti-inflammatory factors [3,8,64]. VIP downregulates the activity of several transduction pathways and their associated transcription factors essential for the transcriptional activation of most inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and costimulatory factors (Figure 2), including nuclear factor-κB (NFκB), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK), interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) and activator protein 1 (AP1) [18,19,21-24,33,34,37].

Figure 2. Molecular mechanisms and transcription factors involved in the anti-inflammatory effects of VIP.

The binding of an inflammatory stimulus, such as the bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide (LPS), to the membrane-bound CD14-toll like receptor (TLR) complex in inflammatory cells (i.e., macrophage, microglia and dendritic cells) results in the stimulation of two different pathways involved in the transcription activation of several inflammatory mediators: nuclear factor-κB (NFκB) and a mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade. In unstimulated cells, NFκB is sequestered in the cytosol by its inhibitor IκB. Cellular stimulation results in IκB phosphorylation by a specific kinase (IKK), triggering IκB ubiquitination, and proteosomal degradation, releasing NFκB to translocate to the nucleus where it binds to specific κB promoter elements. Interaction between NFκB and coactivators such as the cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB)-binding protein (CBP) is required for maximal transactivation. Such coactivators bridge various transcriptional activators and components of the basal transcriptional machinery. Meanwhile, the activation of MAPK kinase kinase 1 (MEKK1) activates different MAPKs, leading to the phosphorylation/activation of cJun by Jun kinase (JNK), of TATA-box-binding protein (TBP) by p38MAPK, and of Elk1 by extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2). cJun, which together with cFos comprise the activator protein-1 (AP1), which acts to transactivate various inflammatory genes through its binding to AP1 sites and cAMP-response elements (CRE). TBP participates in the initiation of transcription by recruiting the basal transcriptional machinery and various transcription factors through its binding to TATA-box sequences. On the other hand, the binding of IFNγ to its receptor initiates the phosphorylation/activation of the Janus kinases Jak1/Jak2, resulting in the generation of the phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription-1 (STAT1) dimers, their translocation to the nucleus and the expression of the IFN regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) which in turn transactivates multiple effector genes. The binding of VIP to VPAC1 increases cyclic AMP (cAMP), activates protein kinase A (PKA) and inhibits IKK, stabilizing the inhibitor IκB and preventing nuclear translocation of NFκB p50/p65 complex (1). In addition, PKA activation induces the phosphorylation of CREB which, due to its high affinity for the coactivator CBP, prevents the association of CBP with p65 (2). Furthermore, PKA activation inhibits MEKK1 activation, and the subsequent activation of p38MAPK and TBP (3). Non-phosphorylated TBP lacks the ability to bind to the TATA box, and to form an active transactivating complex with CBP and NFκB, resulting in inefficient recruitment of the RNA polymerase II, which further weakens transcription. Inhibition of MEKK1 also deactivates JNK and cJun phosphorylation (4). In addition, PKA induces the expression of JunB, which can inactivate the transcriptional AP1 complex via displacement of of c-Jun with JunB or CREB. PKA activation can also inhibit both NFκB and MAPK pathways by downregulating TLR and CD14 expression (5). Finally, PKA signaling inhibits Jak-STAT1 pathway and subsequent induction of IRF1 (6). The end result is that the complex of transcriptional transactivators, which were recruited to the promoters of several inflammatory mediators (tumor-necrosis factor-α (TNFα) is shown as an example) in response to the signaling via the TLR4 receptor, is significantly disrupted by neuropeptide treatment (compare profile A with profile B). Arrows indicate a stimulatory effect. Back-crossed lines indicate an inhibitory effect.

Compelling evidence indicates that VIP regulates all these pathways via cAMP/PKA signaling [11]. Interestingly, VIP inhibition of NFκB nuclear translocation in microglia and DCs is cAMP-dependent, whereas it is partially cAMP-independent in macrophages [11]. Considering that both microglia and DCs represent more advanced states of cell differentiation than macrophages, it suggests that the cAMP-dependence of the VIP inhibition of NFκB might be a function of the differentiation state of the cell. Although these transduction pathways have not been definitively associated with the therapeutic effect of VIP on immune disorders, neuropeptide treatment has been shown to inhibit NFκB and AP1 signaling in arthritic mice in vivo [58,98].

3.2. VIP acts as a TH1-supressive factor in adaptive immunity

Although the balance of T-cell differentiation into TH1 or TH2 effectors depends mainly on the nature of the APCs involved and the cytokine microenvironment, the involvement of other endogenous factors, such as VIP, has been proposed recently. Murine macrophages and DCs treated with VIP in vitro induce the production of TH2-type cytokines (IL-4 and IL-5) and inhibits the production of TH1-type cytokines (IFNγ, IL-2) in antigen-primed CD4+ T cells [31,38]. In addition, the administration of VIP to immunized mice results in decreased numbers of IFNγ-secreting cells and increased numbers of IL-4 secreting cells [31]. Correspondingly, VPAC2 receptor-deficient mice show increased TH1-type responses (i.e., delayed-type hypersensitivity), whereas mice that overexpress VPAC2 receptors exhibit eosinophilia, high levels of IgE and IgG1, and increased cutaneous anaphylaxis (typical TH2-type responses) [45,91]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the endogenous VIP expression from mouse TH2 cells maintains theTH2 bias, via positive feedback regulation [92].

Although the precise mechanisms remain to be elucidated, VIP appears to regulate the TH1/TH2 balance in several ways. Firstly, VIP inhibits the production of the TH1- associated cytokine IL-12 [35]. Secondly, VIP induces CD86 expression in resting murine DCs, which is important for the development of TH2 cells [31,38]. Thirdly, VIP has been shown to promote specific TH2-cell recruitment by inhibiting CXC-chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10) production and inducing CC-chemokine ligand 22 (CCL22) production, two chemokines that are involved in the homing of TH1 cells and TH2 cells, respectively [28,57]. Fourthly, VIP inhibits CD95 (FasL)- and granzyme B-mediated apoptosis of mouse TH2 but not of TH1 effector cells [30,81]. Finally, VIP induces the TH2 master transcription factors c-MAF, GATA-3 and JUNB in differentiating murine CD4+ T cells, and inhibits T-bet, which is required for TH1 cell differentiation [73,90]. Thus VIP regulates the TH1/TH2 balance by acting both directly on differentiating T cells and indirectly via the regulation of APC functions.

3.3. Beneficial effects of VIP on experimental autoimmunity

The capacity of VIP to regulate a wide spectrum of inflammatory factors and to move the TH1/TH2 balance in favor of TH2 immunity makes it an attractive therapeutic candidate for the treatment of inflammatory disorders and/or TH1-type autoimmune diseases. Indeed, administration of VIP has been shown to delay the onset, decrease the frequency and/or severity of various experimental models of collagen-induced arthritis [15,43,99], inflammatory bowel disease [1], type I diabetes [55,73], multiple sclerosis [51,61], Sjogren’s syndrome [63], pancreatitis [60], uveoretinitis [59] and keratitis [87]. VIP treatment impairs both early events, which are involved with the initiation and establishment of autoimmunity to self-tissue components, and the later phases, which are associated with the evolving immune and destructive inflammatory responses. VIP reduces the development of self-reactive TH1 cells, their entry into the target organ, the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (mainly TNFα and IFNγ) and chemokines, and the subsequent recruitment and activation of macrophages and neutrophils (Figure 1). This results in the decreased production of destructive inflammatory mediators (cytokines, nitric oxide, free radicals and matrix metalloproteinases) by both infiltrating and resident (i.e., microglia or synoviocytes) inflammatory cells. In addition, the inhibition of the self- reactive TH1-cell response by VIP is associated with a decreased titer of IgG2a autoantibodies, which can otherwise activate complement and neutrophils, and further contribute to tissue destruction.

4. Generation of Treg cells contributes to VIP control of immune tolerance

Although the idea of CD4+ Treg cells has been around for more than two decades, only recently it has become generally accepted that Treg cells can be divided into two populations: natural (or constitutive) and inducible (or adaptive) (Figure 3). This realization has opened up new therapeutic avenues for the treatment of the several human diseases that are associated with Treg dysfunction [5,83]. For example, Treg cells have been shown to be deficient in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes and other autoimmune diseases [39,62,88]. A large body of literature describes the ontogeny and mechanisms involved in the suppressive action of Treg cells on autoreactive lymphocytes [5,68,83]. However, the endogenous factors and mechanisms controlling their peripheral generation or expansion are mostly unknown.

Figure 3. VIP generates various populations of regulatory T cells involved in immune tolerance.

Immune tolerance depends on the generation of both natural and inducible populations of regulatory T (Treg) cells, which have complementary and overlapping functions in the control of immune responses in vivo. Natural Treg cells develop and migrate from the thymus and constitute 5-10% of peripheral T cells in normal mice and humans. These CD4+CD25+ Treg cells express the transcriptional repressor FoxP3 (forkhead box P3) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 (CTLA4). Natural Treg cells suppress clonal expansion of self-reactive T cells through a mechanism that is cell-cell contact dependent and mediated by CTLA4. Interaction of CTLA4 with CD80 and/or CD86 on the surface of the antigen-presenting cells (APCs) delivers a negative signal for T-cell activation. In vivo studies, but not most in vitro studies, have found a role for cytokines such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) in the function of natural Treg cells. Other populations of antigen-specific Treg cells can be induced from CD4+CD25- or CD8+CD25- T cells in the periphery under the influence of semi-mature tolerogenic dendritic cells and/or various soluble factors such as IL-10, TGFβ1 and interferon-α. The inducible Treg populations consist of distinct subsets: T regulatory 1 (Tr1) cells, which secrete high levels of IL-10 and probably TGFβ1; T helper 3 (Th3) cells, which secrete high levels of TGFβ1; and CD8+ Treg cells, which secrete IL-10. These immunosuppressive cytokines inhibit the proliferation of effector T cells and their production of cytokines, as well as the cytotoxic (CTL) activity of CD8+ T cells, either directly or through their inhibitory action on the maturation/activation of APCs. In addition, CD8+ Treg cells induce the expression of the immunoglobulin-like transcripts ILT3 and ILT4 in APCs, which negatively affect APC function. These suppressive responses can be beneficial for the restoration of immune homeostasis in the host. In treating autoimmune disease, Treg cells suppress autoreactive TH1 responses involved in the destruction of the target tissue. While in transplantation, Treg cells inhibit host CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that can otherwise recognize and react to alloantigens causing transplant rejection. In the case of bone-marrow transplantation Treg cells suppress alloreactive T cells present in the graft that are responsible for causing acute graft-versus-host disease. However, it can also be detrimental as Treg cells can impair effective immune responses to infections, pathogens and tumors. VIP induces the generation of different types of Treg cells by two independent mechanisms. A. The presence of VIP during the initial stages of differentiation of dendritic cells (DCs) from bone-marrow cells or monocytes generates semi-mature DCs that are unable to mature even after adequate activation. Such semi-mature DCs show a tolerogenic phenotype that is characterized by low expression of the co-stimulatory molecules CD40, CD80 and CD86, low production of inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), IL-12 and IL-6, and increased secretion of IL-10. It is the lack of essential costimulatory signals and the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10 in allogeneic or antigen-specific VIP-differentiated tolerogenic DCs that permits them to stimulate the generation of CD4+ and CD8+ T regulatory 1 (Tr1)-like cells. The resulting T cells show the characteristic cytokine profile (high IL-10/transforming growth factor-β1 (TGFβ1) production, little interferon-γ (IFNγ), IL-2, IL-4 secretion), antigen-specific suppressive activity on effector T cells and high expression of the suppressive molecule CTLA4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4) B. VIP also triggers the generation of peripherally induced FoxP3+CD4+CD25+ Treg cells from naïve CD4+CD25- T cells. These cells express high levels of CTLA4 and produce IL-10 and/or TGFβ1. Both VIP-induced Treg cell subtypes contribute to the suppression of self-reactive TH1 cells in autoimmune conditions and alloantigen-specific T cells in transplantation. This can help to restore immune tolerance, and inhibit autoimmunity, transplant rejection and graft-versus-host disease.

4.1. VIP effect on Treg cells: beyond regulation of Th1/Th2 balance in autoimmunity

Although a direct inhibitory effect of VIP on both inflammatory and autoreactive TH1-type responses would be sufficient to explain its therapeutic action upon autoimmune diseases (see section 3.3), recent observations suggest that additional mechanisms might also be involved. For example, VIP is able to inhibit events of the inflammatory phase in mice with rheumatoid arthritis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) following the activation/differentiation of antigen-specific effector TH1 cells [15,51]. Furthermore, T-cell proliferation in response to the corresponding autoantigen is almost completely abolished in VIP-treated animals, although the levels of TH2-type cytokines produced by these low-proliferating cells are significantly increased [15,51].

In order to understand both observations we should consider that Treg cells confer significant protection against autoimmunity by promoting protective TH2 responses and decreasing the homing of self-reactive T cells to the affected tissues [68,97]. In this sense, we found that CD4+ T cells from VIP-treated arthritic and EAE mice did not transfer their respective diseases [41,50]. However, when these cells were depleted of CD4+CD25+ cells prior to transplantation, disease transfer did occur, suggesting that VIP might induce the generation and/or activation of Treg cells during the autoimmune process. In fact, VIP treatment of EAE and arthritic mice resulted in a 4-fold increase in CD4+CD25+ T-cell numbers in lymph nodes, brain and joints [41,50].

VIP-induced CD4+CD25+ cells exhibit an activated Treg cell phenotype [5,68,83], i.e. CD45RBlowCD62LhighCD69high, high expression of forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) and the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4), and produce high levels of IL-10 and TGFβ1 as suppressive molecules [41,50]. Similarly, other authors have reported that VIP administration to mice with type 1 diabetes is associated with increased pancreatic FoxP3 and TGFβ1 expression [73]. VIP mediated changes in FoxP3 expression in the CD4+ population were due solely to increased numbers of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells, and not to changes the expression level per cell, suggesting that VIP promotes the new generation of Treg cells [41,50,73].

A contribution of such Treg cells to the beneficial effect of VIP on autoimmunity is supported by the fact that the in vivo blockade of the Treg cell mediators CTLA4, IL-10 and TGFβ1, but not the TH2-type cytokine IL-4, significantly reversed the therapeutic action of VIP [41,50]. Therefore, the generation of Treg cells by VIP could explain the selective inhibition of TH1 immune responses after T cells have completed differentiation into TH1 effector cells, as evidenced by the therapeutic effect of delayed administration of VIP in established arthritis, EAE and diabetes [15,51,56].

4.2. VIP induces the generation of a mixture of Treg cell types through various mechanisms

Our understanding of the role of the VIP-induced Treg cells in immune homeostasis is far from complete, and there are several important questions that should be answered. Which type(s) of Treg cells are induced by VIP? By which mechanisms does VIP trigger the increase in Treg cells? A number of models have been postulated (see Figure 3). VIP could induce the de novo generation of natural CD4+CD25+ Treg cells in the thymus, or promote the formation of some type(s) of inducible Treg cells (Tr1 and Th3) from the CD4+CD25− T cell population or inducible CD8+ Treg cells from the CD8+CD25− T cell repertory. Alternatively, VIP could promote the peripheral expansion of pre-existing natural and/or inducible Treg cells.

Interestingly, murine CD4+CD25+ Treg cells, induced in vivo by VIP, mediate their suppressive action on autoreactive T cells by secreting suppressive soluble factors, such as IL-10 and TGFβ1, and through CTLA4-dependent cellular contact [16,41,47,50]. This distinguishes VIP-induced Treg cells from classical Tr1 or Th3 CD4+ Treg cells, whose suppressive mechanism is cytokine-dependent [5,68,83], and from CD4+CD25+ Treg cells (both natural and those induced from the peripheral CD4+CD25− population) which are contact-dependent and cytokine-independent suppressors (Figure 3). This suggests that the Treg population induced by VIP in vivo may represent a novel Treg cell population, or perhaps more plausibly, that VIP induces/activates one of the other types of Treg cells already described to act cooperatively in the suppressive response (Figure 3).

The minor IL-10/TGFβ-producing Treg cells induced by VIP phenotypically resemble the previously described Tr1 cells induced by tolerogenic DCs differentiated in response to various immunosuppressive factors [54]. Recent studies have shown that VIP promotes the generation of human and murine tolerogenic DCs in vitro and in vivo [27,48], which induce antigen-specific tolerance by generating Tr1-like cells.

VIP also induces a major population of mouse FoxP3+CTLAhighCD4+CD25+ Treg cells that resemble CD25+ T cells reported to be recruited from the peripheral CD25− T-cell population by IL-2 and TGFβ-activated CD4+CD25+ T cells [100]. Although the mechanism involved in the generation/expansion of this Treg population is not fully understood, VIP administration is thought to prevent disease progression in CD25-depleted arthritic and EAE mice by inducing the emergence of peripheral CD4+CD25+ Treg cells [41,50]. Moreover, VIP treatment generates CTLA4+FoxP3+CD4+CD25+ Treg cells from CD4+CD25− T cells isolated from arthritic mice [50], where the induction of cell cycle arrest and CTLA4 expression by VIP in the CD4+CD25− T cells seem to be critical (unpublished results). Together these observations suggest that VIP might act to expand the Treg cell population by inducing the production of new Treg cells from the CD4+CD25− T-cell repertoire.

Finally, although it is unknown whether or not CD8+ Treg cells are involved in the therapeutic action of VIP, we have found that VIP-induced tolerogenic DCs, generated from human monocytes, can induce antigen-specific human IL-10-producing CD8+CD28−CTLA4+ Tr1-like cells in vitro [44], suggesting that VIP might indirectly induce CD8+ Treg cells in vivo, via tolerogenic DCs. These CD8+ Treg cells appear to resemble two of the reported CD8+ Treg subsets generated after repeated stimulation of T cells with xenogenetic or antigen-pulsed APCs: the IL-10-producing CD8+ T-cell population induced with plasmacytoid DCs and the CD8+CD28−FoxP3+ T cells [44,89].

In this context, it is interesting that VIP has recently been described to regulate different functions of human plasmacytoid DCs, although the potential generation of CD8+ Treg cells was not addressed in this study [40]. Interestingly, CD8+CD28− Treg cells target APCs and render them tolerogenic by increasing the expression of suppressive genes encoding Ig-like transcripts, ILT3 and ILT4 and inhibiting the transcription of costimulatory molecules [89], through a mechanism that depends on the inhibition of NF-κB. Although an effect of VIP upon the expression of ILTs in APCs has not been reported, we have determined that the induction of tolerogenic DCs by VIP is related to a persistent inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway that maintains a “semi-mature” phenotype even under strong stimulation [27].

5. Regulatory T-cell therapy: new opportunities for the treatment of autoimmunity and transplantation

Over recent years considerable effort has been focused on the use of antigen-specific Treg cells generated ex vivo to treat autoimmune diseases, transplantation and asthmatic disorders [5]. The ability to translate important biological findings about Treg cells from the laboratory to the clinic has been limited by several issues, including their relative scarcity and the potential for pan immunosuppression. The solution for this problem may lie in expanding the cell population in vitro, and making them antigen-specific using selected antigens and peptides. However, while Treg cells replicate relatively efficiently in vivo, they are anergic and refractory to stimulation in vitro [42,83,93]. Thus in order to efficiently expand Treg populations in vitro while maintaining their immunoregulatory properties in vivo, new protocols must be developed which replicate those conditions that allow their expansion in vivo, including TCR occupancy, crucial co-stimulatory signals and selective growth factors. VIP could be one of the endogenous growth factors involved in the generation/expansion of Treg cells. This is supported by the fact that VIP is capable of inducing the generation of antigen-specific Treg cells from otherwise conventional T cells in vitro [41,50].

5.1. Therapy with VIP-induced Treg cells

How potent are VIP-induced Treg cells in regulating autoimmune responses? Recent results suggest that the Treg cells induced by VIP are very powerful suppressive cells. CD4 T cells derived from VIP-treated mice can efficiently suppress the autoreactive response of antigen-specific TH1 cells at ratios as low as one VIP-induced Treg cell to eight autoreactive CD4 cells [41,50]. Moreover in vivo transfer of VIP-induced mouse Treg cells can induce antigen-specific suppression to naïve hosts, inhibiting delayed-type hypersensitivity and antibody formation [16]. In addition, low numbers of these cells can efficiently prevent the progression of experimental autoimmune diseases by suppressing the systemic autoantigen-specific T and B cell responses and the tissue-localized inflammatory response [41,50]. This makes the use of VIP for ex vivo generation of highly efficient Treg cells an attractive future therapeutic tool, eliminating the need to directly administer the peptide to the patient.

The effective treatment of experimental arthritis by adoptive transfer of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells has been previously reported [69], although its therapeutic effect is mainly exerted through control of the local inflammatory response in the joint, rather than though the regulation of systemic T-cell and B-cell responses. These differences could be attributed to the fact that, in comparison with conventional CD4+CD25+ Treg cells, VIP-induced Treg cells consist of a mixture of cells expressing higher amounts of the mediators involved in their suppressive action, such as CTLA-4, IL-10, and TGFβ1, making them very efficient at suppressing autoreactive TH1 cells and subsequent B-cell responses (Figure 3).

5.2. VIP induces DCs with tolerogenic capacity

Growing evidence suggests that DCs not only control immunity but also maintain tolerance to self-antigens, two complementary functions in ensuring the integrity of the organism. The capacity of certain classes of DCs to induce Treg cells makes them attractive for the expansion/generation of antigen-specific Treg cells ex vivo, or alternatively, for their use in vivo as therapeutic cells to restore immune tolerance by inducing Treg cells in the host [74,75,84].

A number of recent findings suggest that VIP-induced DCs may have considerable value in treating inflammatory diseases. For example VIP-induced tolerogenic mouse DCs pulsed with self-antigens have been shown to ameliorate the progression of rheumatoid arthritis, EAE and inflammatory bowel disease [10,49]. These effects appear to be primarily mediated through the generation of antigen-specific Tr1-like cells in the treated animal. In disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease, where inflammation is the predominant component, the effect of the tolerogenic DCs appears to be antigen non-specific and related to a direct impairment of inflammation by their production of anti-inflammatory factors (mainly IL-10) [49].

Such strategies can be used not only to control immune responses to self-antigens, but also to control responses to non-self molecules that are introduced into the host deliberately, such as the alloantigens of a cell/organ donor. In this case, manipulating the balance between the deletion and regulation of responder T cells is also an effective strategy in controlling immune responsiveness after cell or organ transplantation.

Numerous reports have demonstrated the beneficial effect of Treg cells and tolerogenic DCs in allogeneic transplantation [54,67,96], especially in allogeneic bone-marrow transplantation (BMT). BMT is the treatment of in many haematopoietic malignancies, where following irradiation or chemotherapy, the host is reconstituted with bone-marrow cells. While donor T-cells are responsible for tumor elimination they can at the same time initiate graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), which is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in recipients of BMT. Some protocols use tolerogenic DCs to prevent GVHD without affecting the graft-versus-tumor response in experimental models of BMT [74,78]. Similarly, tolerogenic mouse DCs generated using VIP have been shown to impair the allogeneic haplotype-specific responses of donor CD4+ T cells in recipient mice by inducing the generation of Treg cells in the graft, thus avoiding GVHD [9]. In this case, VIP-induced tolerogenic DCs did not abrogate the tumor eradication by the transplant, presumably because they did not affect the cytotoxic response of the grafted CD8+ T cells against the leukemic cells. Interestingly, in addition to the induction of allogeneic IL-10-producing CD4+CD25+CTLA4+ and CD8+ Treg cells, VIP-induced tolerogenic DCs also triggered the emergence of a cytotoxic T-cell population (CD8+CD44highCD62Llow) within the graft that prevented GVHD while maintaining graft-versus-tumor activity [9]. The involvement of Treg cells in the effects of VIP-induced tolerogenic DCs in transplantation has been confirmed by the partial reversion of the therapeutic effect by in vivo CD25-depletion and IL-10/TGFβ-blocking, as well as by the effective treatment of GVHD by allogeneic CD4+ and CD8+ Treg cells generated ex vivo with these DCs [9].

6. Therapeutic perspectives: is VIP ready for the clinic?

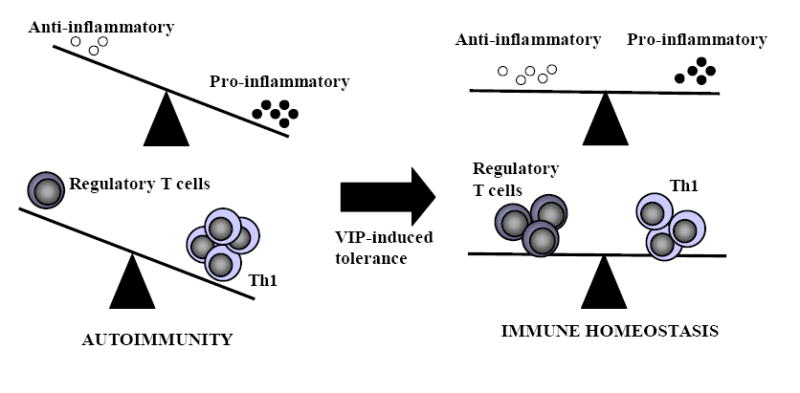

The findings reviewed above indicate that VIP acts in a pleiotropic and in many cases redundant manner to regulate the balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory factors, and between Th1 effector/autoreactive cells and regulatory T cells (Figure 4). Based on these characteristics, VIP appears to represent an exciting prospect as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of immune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, Crohn’s disease and other diseases characterized by both inflammatory and autoimmune components. Whereas VIP strongly ameliorates all these organ-specific autoimmune disorders, the effect of VIP on systemic autoimmune diseases has not been still investigated. However, autoantibodies against VIP have been found in animals and patients with systemic lupus erithematous [2], suggesting that the depletion of VIP by specific antibodies in this systemic autoimmune disease may exacerbate autoreactive responses.

Figure 4. VIP restores immune tolerance.

An imbalance between regulatory T cells versus TH1 cells, or of anti-inflammatory cytokines versus proinflammatory factors, are key causes of autoimmune disorders. VIP restores immune homeostasis by rebalancing this scenario by downregulating the inflammatory response and inducing regulatory T cells.

VIP shows therapeutic advantages versus agents directed only against one component of these diseases, where combinatory therapies have been proposed by other researchers. An important caveat to this is that, although many studies have confirmed the therapeutic potential of VIP, most studies carried out so far have been performed using animal models. Although valuable, the findings from these studies should be extended to human diseases with caution. Differences may be expected in terms of peptide dosage and in the expression of specific receptors by different immunocompetent cells. However, it is important to note that VIP has been previously tested in humans for the treatment of sepsis and other disorders [Ref. 71; and NCT00004494 clinical trial: http://www.ClinicalTrials.gov), suggesting that it should be well tolerated in humans in doses similar to those that are able to prevent immunological diseases in animals.

From a therapeutic point of view, in addition to its wide spectrum of action, it is its peptide nature, particularly its molecular structure and size, that makes VIP so attractive as a therapeutic agent against excessive inflammation. As a small and hydrophilic molecule, VIP possesses excellent permeability properties that permit rapid access to the site of inflammation, even in the CNS, where under inflammatory conditions the blood-brain-barrier is disturbed. In fact, VIP has been found to be therapeutically effective in various neuroinflammatory disorders [13,20,26], where it possesses the additional advantage that due to its small size, it does not generate antigenicity. Its second advantage owes to its high-affinity binding to specific receptors, thus making VIP very potent in exerting its action. Thirdly, as compared to existing anti-inflammatory drugs, VIP is not associated with dramatic side-effects, because as a physiological compound it is intrinsically non-toxic. In addition, VIP is rapidly cleared from the body through natural hepatic detoxification mechanisms and renal excretion. Moreover, other cytokines, neuropeptides and hormones often counterbalance VIP actions, meaning that the homeostasis of normal tissues should not be excessively perturbed. Finally, as a small peptide, the in vitro synthesis of VIP is straightforward and permits easy modification if necessary.

Despite these advantages, several obstacles stand between translating VIP based-treatment into viable clinic therapies. Due to its natural structural conformation, VIP is very unstable and extremely sensitive to the peptidases present in most tissues. Several strategies have been developed to increase VIP half-life such as by the modification and/or substitution of certain aminoacids in the sequence or cycling the structure increases the stability of the peptide [6,52]. Perhaps even more important is work towards improving neuropeptide delivery to target tissues and cells while protecting it against degradation. Different strategies being tested under experimental conditions include neuropeptide gene delivery or the insertion of VIP into micelles or nanoparticles [56,63,70,71,80]. Other methods include combining VIP treatment with inhibitors of neutral endopeptidases to reduce the degradation of the peptide in the circulation [79]. Others combinatory treatments aim to take advantage of the fact that activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway appears to be the major signal involved in the VIP immunomodulatory effect, thus combining VIP with inhibitors of phosphodiesterases (enzymes involved in the degradation of cAMP) has been found to be therapeutically attractive in the treatment of some inflammatory diseases [43].

However, the principal approach of the pharmaceutical companies as a prerequisite for successful clinical applications is the development of metabolically stable analogues. Understanding of the structure/function relationship of VIP and its specific receptors, including receptor signaling, internalization and homo/heterodimerization, will be essential for the development of novel pharmacologic agents for the treatment of inflammatory/autoimmune disorders and opening up new applications for VIP derived treatments. However, in the case of the type 2 G protein-coupled receptors (i.e., receptors for VIP, urocortin, melanocyte-stimulating hormone and adrenomedullin), the pharmaceutical industry has so far failed to generate effective nonpeptide-specific agonists. Even where synthetic agonists were designed specifically for VIP receptors, they were less effective than the natural peptide as anti-inflammatory agents [1,15,32,51]. In any case, the focus on the use of natural peptides in therapy is not new, and may be a case of history repeating itself, since naturally occurring human compounds have often proved to have striking therapeutic value (e.g., insulin and cortisone).

It is significant that the organism responds to an exacerbated inflammatory response by increasing the peripheral production of endogenous anti-inflammatory neuropeptides, such as VIP, in an attempt to restore the immune homeostasis [7,14,32,51]. In addition, the presence of VIP in barrier organs like skin and mucosal barriers of the gastrointestinal, genital and respiratory tracts suggests that this neuropeptide may be a key component of the innate immune system. Indeed, we have recently found that VIP possesses antimicrobial properties (submitted for publication). The relevance of VIP as a natural anti-inflammatory factor is also supported by results obtained from several inflammatory models performed using animals deficient for VIP or its receptors [45,65,86,91]. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that VIP initially emerged as a natural component of the innate defense, which over the course of evolution acquired additional functions, to act in the co-ordination and homeostasis of immune responses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Health, the NIH and the Ramon Areces Foundation.

Glossary

- Allogeneic response

an immune response against antigens that are distinct between members of the same species, such as MHC molecules or blood-group antigens.

- cAMP/PKA pathway

binding of specific ligands (i.e., VIP) to GPCRs activates a stimulatory G-protein (Gs) that induces the intracellular accumulation of cAMP through the activation of adenylate cyclase (AC). cAMP-binding to the regulatory subunits of the protein kinase A (PKA) releases PKA catalytic subunits, which phosphorylates/activates different targets in the cytosol, such as the cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB). cAMP/PKA signaling has been mainly associated with immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory responses.

- Central clonal deletion

a mechanism of immune tolerance where developing self-reactive lymphocytes, generated by random gene recombination, that possess high affinity for ubiquitously expressed self-antigens, are eliminated in the thymus by several mechanisms, including deletion and receptor editing. Similarly, weakly self-reactive lymphocytes are rendered unresponsive by a phenomenon called central anergy.

- Chemokines

a family of small cytokines secreted by different cell types in response to bacterial or virus infection that induce directed chemotaxis in nearby responsive cells. Two major chemokine families have been described: CC chemokines with two adjacent cysteines near the amino terminus, and CXC chemokines in which cysteines are separated by an amino acid.

- Co-stimulatory signal

a secondary signal, required in addition to T-cell receptor signaling for the activation of T cells. Such signals are provided by costimulatory molecules expressed by antigen presenting cells, mainly CD80 and CD86 that binds to CD28 or CTLA4 in T cells, or CD40 that binds to CD154 in T cells.

- Crohn’s disease

a chronic and relapsing inflammatory bowel disease characterized by dysfunction of mucosal T cells, altered cytokine production and cellular inflammation that ultimately leads to damage of the distal small intestine and the colonic mucosa, resulting in abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, diarrhea and weight loss.

- Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 (CTLA4)

a T-cell surface protein that following its binding to CD80 or CD86 on antigen presenting cells negatively signals activated T cells to induce cell-cycle arrest and inhibit cytokine production. CTLA4 is constitutively expressed by and functionally associated with regulatory T cells.

- Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)

An inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system, which shows pathological and clinical similarities to multiple sclerosis. EAE is considered an archetypal CD4 TH1 cell-mediated autoimmune disease in which TH1 cells reactive to components of the myelin sheath, infiltrate the nervous parenchyma, releasing inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, promoting leukocyte infiltration and contribute to demyelization.

- G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)

a receptor comprised of seven membrane spanning helical segments, connected by extracellular and intracellular loops. GPCR receptors associate with guanine nucleotide binding proteins (G-proteins), which are a family of trimeric, intracellular signaling proteins with common β- and γ-chains, and one of several α-chains. The α-chain determines the nature of the signal that is transmitted from the ligand-bound GPCR to downstream effector pathways. The neuropeptide receptors are all members of this family of proteins.

- Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

an immune response mounted against the recipient of an allograft (generally in the context of allogeneic bone-marrow transplantation) by donor T cells derived from the graft.

- Rheumatoid arthritis

An autoimmune disease that leads to chronic inflammation in the joints and subsequent destruction of the cartilage and erosion of the bone. It is divided into two main phases: initiation and establishment of autoimmunity to collagen rich joint components, and later events associated with the evolving destructive inflammatory processes.

- Sepsis

a systemic response to severe bacterial infections, generally caused by Gram-negative bacterial endotoxins, that gives rise to a hyperactive and disturbed network of inflammatory cytokines, affecting vascular permeability, cardiac function, metabolic balance, leading to tissue necrosis and to multiple-organ failure and death.

- Toll-like receptors (TLRs)

a family of receptors expressed on the surface of antigen presenting cells, which recognize conserved molecules from a wide variety of pathogens.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abad C, Martinez C, Juarranz MG, Arranz A, Leceta J, Delgado M, et al. Therapeutic effects of vasoactive intestinal peptide in the trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid mice model of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:961–71. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bangale Y, Karle S, Planque S, Zhou YX, Taguchi H, Nishiyama Y, et al. VIPase autoantibodies in Fas-defective mice and patients with autoimmune disease. FASEB J. 2003;17:628–35. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0475com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banner KH, Trevethick MA. PDE4 inhibition: a novel approach for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:430–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blalock JE. The immune system as the sixth sense. J Intern Med. 2005;257:126–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bluestone JA. Regulatory T-cell therapy: is it ready for the clinic? Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:343–9. doi: 10.1038/nri1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolin DR, Michalewsky J, Wasserman MA, O’Donnell M. Design and development of a vasoactive intestinal peptide analog as a novel therapeutic for bronchial asthma. Biopolymers. 1995;37:57–66. doi: 10.1002/bip.360370203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandtzaeg P, Oktedalen O, Kierulf P, Opstad PK. Elevated VIP and endotoxin plasma levels in human gram-negative septic shock. Regul Pept. 1989;24:37–44. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(89)90209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castro A, Jerez MJ, Gil C, Martinez A. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases and their role in immunomodulatory responses: advances in the development of specific phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Med Res Rev. 2005;25:229–44. doi: 10.1002/med.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chorny A, Gonzalez-Rey E, Fernandez-Martin A, Ganea D, Delgado M. Vasoactive intestinal peptide induces regulatory dendritic cells that can prevent acute graft-versus-host disease while maintain graft-versus-tumor. Blood. 2006;107:3787–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chorny A, Gonzalez-Rey E, Fernandez-Martin A, Pozo D, Ganea D, Delgado M. Vasoactive intestinal peptide induces regulatory dendritic cells with therapeutic effects on autoimmune disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13562–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504484102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chorny A, Gonzalez-Rey E, Varela N, Robledo G, Delgado M. Signaling mechanisms of vasoactive intestinal peptide in inflammatory conditions. Regul Pept. 2006;137:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2006.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De la Fuente M, Delgado M, Gomariz RP. VIP modulation of immune cell functions. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1996;6:75–91. doi: 10.1016/s0960-5428(96)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dejda A, Sokolowska P, Nowak JZ. Neuroprotective potential of three neuropeptides PACAP, VIP and PHI. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:307–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delgado M, Abad C, Martinez C, Juarranz MG, Arranz A, Gomariz RP, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide in the immune system: potential therapeutic role in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. J Mol Med. 2002;80:16–24. doi: 10.1007/s00109-001-0291-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delgado M, Abad C, Martinez C, Leceta J, Gomariz RP. Vasoactive intestinal peptide prevents experimental arthritis by downregulating both autoimmune and inflammatory components of the disease. Nat Med. 2001;7:563–8. doi: 10.1038/87887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delgado M, Chorny A, Gonzalez-Rey E, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide generates CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1327–38. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0605299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delgado M, Ganea D. Cutting Edge: Is vasoactive intestinal peptide a type 2 cytokine? J Immunol. 2001;166:2907–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delgado M, Ganea D. Inhibition of endotoxin-induced macrophage chemokine production by vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2001;167:966–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.2.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delgado M, Ganea D. Inhibition of IFN-gamma-induced janus kinase-1-STAT1 activation in macrophages by vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide. J Immunol. 2000;165:3051–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delgado M, Ganea D. Neuroprotective effect of vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease by blocking microglial activation. FASEB J. 2003;17:944–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0799fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delgado M, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide inhibit interleukin-12 transcription by regulating nuclear factor kappaB and Ets activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31930–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.31930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delgado M, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide inhibits IL-8 production in human monocytes by downregulating nuclear factor kappaB-dependent transcriptional activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;302:275–83. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delgado M, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide inhibit the MEKK1/MEK4/JNK signaling pathway in LPS-activated macrophages. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;110:97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(00)00359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delgado M, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide inhibit nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent gene activation at multiple levels in the human monocytic cell line THP-1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:369–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delgado M, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide inhibits IL-8 production in human monocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;301:825–32. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delgado M, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide prevents activated microglia-induced neurodegeneration under inflammatory conditions: potential therapeutic role in brain trauma. FASEB J. 2003;17:1922–4. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1029fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delgado M, Gonzalez-Rey E, Ganea D. The neuropeptide vasoactive intestinal peptide generates tolerogenic dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:7311–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delgado M, Gonzalez-Rey E, Ganea D. VIP/PACAP preferentially attract Th2 versus Th1 cells by differentially regulating the production of chemokines by dendritic cells. FASEB J. 2004;18:1453–5. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1548fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delgado M, Leceta J, Abad C, Martinez C, Ganea D, Gomariz RP. Shedding of membrane-bound CD14 from lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages by vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;99:61–71. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delgado M, Leceta J, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide promote in vivo generation of memory Th2 cells. FASEB J. 2002;16:1844–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0248fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delgado M, Leceta J, Gomariz RP, Ganea D. VIP and PACAP stimulate the induction of Th2 responses by upregulating B7.2 expression. J Immunol. 1999;163:3629–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delgado M, Martinez C, Pozo D, Calvo JR, Leceta J, Ganea D, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) protect mice from lethal endotoxemia through the inhibition of TNF-α and IL-6. J Immunol. 1999;162:1200–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delgado M, Munoz-Elías EJ, Gomariz RP, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide prevent inducible nitric oxide synthase transcription in macrophages by inhibiting NF-kB and IFN regulatory factor 1 activation. J Immunol. 1999;162:4685–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delgado M, Munoz-Elías EJ, Gomariz RP, Ganea D. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide enhance IL-10 production by murine macrophages: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Immunol. 1999;162:1707–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delgado M, Munoz-Elias EJ, Gomariz RP, Ganea D. VIP and PACAP inhibit IL-12 production in LPS-stimulated macrophages. Subsequent effect on IFNγ synthesis by T cells. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;96:167–81. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delgado M, Pozo D, Ganea D. The significance of vasoactive intestinal peptide in immunomodulation. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:249–90. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.2.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Delgado M, Pozo D, Martínez C, Leceta J, Calvo JR, Ganea D, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide inhibit endotoxin-induced TNF production by macrophages: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Immunol. 1999;162:2358–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delgado M, Reduta A, Sharma V, Ganea D. VIP/PACAP oppositely affect immature and mature dendritic cell expression of CD80/CD86 and the stimulatory activity of CD4+ T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:1122–30. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1203626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ehrenstein MR, Evans JG, Singh A, Moore S, Warnes G, Isenberg DA, et al. Compromised function of regulatory T cells in rheumatoid arthritis and reversal by anti-TNFα therapy. J Exp Med. 2004;200:277–85. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fabricius D, O’Dorisio MS, Blackwell S, Jahrsdorfer E. Human plasmacytoid dendritic cell function: inhibition of IFN-alpha secretion and modulation of immune phenotype by vasoactive intestinal peptide. J Immunol. 2006;177:5920–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernandez-Martin A, Gonzalez-Rey E, Chorny A, Ganea D, Delgado M. Vasoactive intestinal peptide induces regulatory T cells during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:318–26. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisson S, Darrasse-Jeze G, Litvinova E, Septier F, Klatzmann D, Liblau R, et al. Continuous activation of autoreactive CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in the steady state. J Exp Med. 2003;198:737–46. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Foey AD, Field S, Ahmed S, Jain A, Feldmann M, Brennan FM, et al. Impact of VIP and cAMP on the regulation of TNF-alpha and IL-10 production: implications for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:R317–28. doi: 10.1186/ar999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilliet M, Liu YJ. Generation of CD8 T regulatory cells by CD40 ligand activated plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:695–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goetzl EJ, Voice JK, Shen S, Dorsam G, Kong Y, West KM, et al. Enhanced delayed-type hypersensitivity and diminished immediate type hypersensitivity in mice lacking the inducible VPAC(2) receptor for VIP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13854–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241503798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gomariz RP, Arranz A, Abad C, Torroba M, Martinez C, Rosignoli F, et al. Time-course expression of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in inflammatory bowel disease and homeostatic effect of VIP. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:491–502. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1004564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzalez-Rey Ë, Chorny A, Delgado M. Regulation of immune tolerance by anti-inflammatory neuropeptides. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:52–63. doi: 10.1038/nri1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gonzalez-Rey E, Chorny A, Fernandez-Martin A, Ganea D, Delgado M. Vasoactive intestinal peptide generates human tolerogenic dendritic cells that induce CD4 and CD8 regulatory T cells. Blood. 2006;107:3632–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gonzalez-Rey E, Delgado M. Therapeutic treatment of experimental colitis with regulatory dendritic cells generated with vasoactive intestinal peptide. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1799–811. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gonzalez-Rey E, Fernandez-Martin A, Chorny A, Delgado M. Vasoactive intestinal peptide induces CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells with therapeutic effect on collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:864–76. doi: 10.1002/art.21652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gonzalez-Rey E, Fernandez-Martin A, Chorny A, Martin J, Pozo D, Ganea D, et al. Therapeutic effect of vasoactive intestinal peptide on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: downregulation of inflammatory and autoimmune responses. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1179–88. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gotthardt M, Boermann OC, Behr TM, Behe MP, Oyen WJ. Development and clinical application of peptide-based radiopharmaceuticals. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:2951–63. doi: 10.2174/1381612043383502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grimm MC, Newman R, Hassim Z, Cuan N, Connor SJ, Le Y, et al. Cutting edge: vasoactive intestinal peptide acts as a potent suppressor of inflammation in vivo by trans-deactivating chemokine receptors. J Immunol. 2003;171:4990–4. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.4990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hackstein H, Thomson AW. Dendritic cells: emerging pharmacological targets of immunosuppressive drugs. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:24–34. doi: 10.1038/nri1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hernanz A, Tato E, De la Fuente M, de Miguel E, Arnalich F. Differential effects of gastrin-releasing peptide, neuropeptide Y, somatostatin and vasoactive intestinal peptide on interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by whole blood cells from healthy young and old subjects. J Neuroummunol. 1997;71:25–30. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herrera JL, Fernandez-Montesinos R, Gonzalez-Rey E, Delgado M, Pozo D. Protective role for plasmid DNA-mediated VIP gene transfer in non-obese diabetic mice. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1070:337–41. doi: 10.1196/annals.1317.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiang X, Jing H, Ganea D. VIP and PACAP down-regulate CXCL10 (IP-10) and up-regulate CCL22 (MDC) in spleen cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;133:81–94. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(02)00365-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Juarranz Y, Abad C, Martinez C, Arranz A, Gutierrez-Canas I, Rosignoli F, et al. Protective effect of vasoactive intestinal peptide on bone destruction in the collagen-induced arthritis model of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:1034–45. doi: 10.1186/ar1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Keino H, Kezuka T, Takeuchi M, Yamakawa N, Hattori T, Usui M. Prevention of experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis by vasoactive intestinal peptide. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:1179–84. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.8.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kojima M, Ito T, Oono T, Hisano T, Igarashi H, Arita Y, et al. VIP attenuation of the severity of experimental pancreatitis is due to VPAC1 receptor-mediated inhibition of cytokine production. Pancreas. 2005;30:62–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li H, Mei Y, Wang Y, Xu L. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide suppressed experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting T helper 1 responses. J Clin Immunol. 2006;26:430–7. doi: 10.1007/s10875-006-9042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lindley S, et al. Defective suppressor function in CD4+CD25+ T-cells from patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:92–99. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lodde BM, Baum BJ, Tak PP, Illei G. Effect of human vasoactive intestinal peptide gene transfer in a murine model of Sjorgre’s disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:195–200. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.038232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lugnier C. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase (PDE) superfamily: a new target for the development of specific therapeutic agents. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;109:366–98. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martinez C, Abad C, Delgado M, Arranz A, Juarranz MG, Rodriguez-Henche N, et al. Anti-inflammatory role in septic shock of pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1053–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012367999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Martinez C, Delgado M, Pozo D, Leceta J, Calvo JR, Ganea D, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide modulate endotoxin-induced IL-6 production by murine peritoneal macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:591–601. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.5.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McCurry KR, Colvin BL, Zahorchak AF, Thomson AW. Regulatory dendritic cell therapy in organ transplantation. Transpl Int. 2006;19:525–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mills KHG. Regulatory T cells: friend or foe in immunity to infection? Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:841–55. doi: 10.1038/nri1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Morgan ME, Flierman R, van Duivenvoorde LM, Witteveen HJ, van Ewijk W, van Laar JM, et al. Effective treatment of collagen-induced arthritis by adoptive transfer of CD25+ regulatory T cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2212–21. doi: 10.1002/art.21195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Onyuksel H, Ikezaki H, Patel M, Gao XP, Rubinstein I. A novel formulation of VIP in sterically stabilized micelles amplifies vasodilation in vivo. Pharm Res. 1999;16:155–60. doi: 10.1023/a:1018847501985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Petkov V, Mosgoeller W, Ziesche R, Raderer M, Stiebellehner L, Vonbank K, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide as a new drug for treatment of primary pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1339–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI17500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pozo D, Guerrero JM, Calvo JR. Vasoactive intestinal peptide and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide inhibit LPS-stimulated MIP-1alpha production and mRNA expression. Cytokine. 2002;18:35–42. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosignoli F, Torroba M, Juarranz Y, Garcia-Gomez M, Martinez C, Gomariz RP, et al. VIP and tolerance induction in autoimmunity. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1070:525–30. doi: 10.1196/annals.1317.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rutella S, Danese S, Leone G. Tolerogenic dendritic cells: cytokine modulation comes of age. Blood. 2006;108:1435–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-006403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rutella S, Lemoli RM. Regulatory T cells and tolerogenic dendritic cells: from basic biology to clinical applications. Immunol Lett. 2004;94:11–26. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Said SI, Mutt V. Polypeptide with broad biological activity: isolation from small intestine. Science. 1970;169:1217–8. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3951.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Said SI, Rosenberg RN. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide: abundant immunoreactivity in neural cell lines and normal nervous tissue. Science. 1976;192:907–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1273576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sato K, Yamashita N, Baba M, Matsuyama T. Regulatory dendritic cells protect mice from murine acute graft-versus-host disease and leukemia relapse. Immunity. 2003;18:367–79. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sedo A, Duke-Cohan JS, Balaziova E, Sedova LR. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity and/or structure homologs: contributing factors in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:253–69. doi: 10.1186/ar1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sethi V, Onyuksel H, Rubinstein I. Liposomal vasoactive intestinal peptide. Methods Enzymol. 2005;391:377–95. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)91021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sharma V, Delgado M, Ganea D. Granzyme B, a new player in activation-induced cell death, is down-regulated by vasoactive intestinal peptide in Th2 but not Th1 effectors. J Immunol. 2006;176:97–110. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sherwood NM, Krueckl SL, McRory JE. The origin and function of the pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP)/glucagon superfamily. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:619–70. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.6.0414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shevach EM. From vanilla to 28 flavors: multiple varieties of T regulatory cells. Immunity. 2006;25:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;109:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sternberg EM. Neural regulation of innate immunity: a coordinated nonspecific host response to pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:318–28. doi: 10.1038/nri1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Szema AM, Hamidi SA, Lyubsky S, Dickman KG, Mathew S, Abdel-Razek T, et al. Mice lacking the VIP gene show airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation, partially reversible by VIP. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:880–6. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00499.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Szliter EA, Lighvani S, Barret RP, Hazlett LD. Vasoactive intestinal peptide balances pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected cornea and protects against corneal protection. J Immunol. 2007;178:1105–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Viglietta V, Baecher-Allan C, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. Loss of functional suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2004;199:971–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vlad G, Cortesini R, Suciu-Foca N. License to heal: Bidirectional interaction of antigen-specific regulatory T cells and tolerogenic APC. J Immunol. 2005;174:5907–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.5907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Voice J, Donnelly S, Dorsam G, Dolganov G, Paul S, Goetzl EJ. c-Maf and JunB mediation of Th2 differentiation induced by the type 2 G protein-coupled receptor (VPAC2) for vasoactive intestinal peptide. J Immunol. 2004;172:7289–96. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Voice JK, Dorsam G, Lee H, Kong Y, Goetzl EJ. Allergic diathesis in transgenic mice with constitutive T cell expression of inducible VIP receptor. FASEB J. 2001;15:2489–96. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0671com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Voice JK, Grinninger A, Kong Y, Bangale Y, Paul S, Goetzl EJ. Roles of vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) in the expression of different immune phenotypes by wild-type mice and T cell-targeted type II VIP receptor transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2003;170:308–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Walker LS, Chodos A, Aggena M, Dooms H, Abbas AK. Antigen-dependent proliferation of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2003;198:249–58. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wan YY, Favell RA. The roles for cytokines in the generation and maintenance of regulatory T cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:114–30. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Weng Y, Sun J, Wu Q, Pan J. Regulatory effects of vasoactive intestinal peptide on the migration of mature dendritic cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;182:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wood JK, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in transplantation tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:199–210. doi: 10.1038/nri1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wraith DC, Nicolson KS, Whitlet NT. Regulatory CD4+ T cells and the control of autoimmune disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16:695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yin H, Cheng H, Yu M, Zhang F, Lin J, Gao Y, et al. Vasoactive intestinal peptide ameliorates synovial cell functions of collagen-induced arthritis rats by down-regulating NF-kappaB activity. Immunol Invest. 2005;34:153–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zafirova Y, Yordanov M, Kalfin R. Antiarthritic effect of VIP in relation to the host resistance against Candida albicans infection. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1125–31. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zheng SG, Wang JH, Gray JD, Soucier H, Horwitz DA. Natural and induced CD4+CD25+ cells educate CD4+CD25- cells to develop suppressive activity: the role of IL-2, TGF-β, and IL-10. J Immunol. 2004;172:5213–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]