Abstract

Aims

This pilot study was designed to evaluate the feasibility and benefits of electronic adherence monitoring of antiretroviral medications in HIV patients who recently started Highly Active Anti Retroviral Therapy (HAART) in Francistown, Botswana and to compare this with self-reporting.

Methods

Dosing histories were compiled electronically using Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS) monitors to evaluate adherence to prescribed therapies. Thirty patients enrolled in the antiretroviral treatment program were monitored over 6 weeks. These patients were all antiretroviral (ARV) naïve. After each visit (mean three times) to the pharmacy, the data compiled by the monitors were downloaded. Electronic monitoring of adherence was compared to patient self-reports of adherence.

Results

The mean individual medication adherence level measured with the electronic device was 85% (range 21–100%). The mean adherence level measured by means of self-reporting was 98% (range 70–100%). Medication prescribed on a once-a-day dose base was associated with a higher adherence level (97.9% for efavirenz) compared with a twice-a-day regimen (88.4% for Lamivudine/Zidovudine).

Conclusions

It is feasible to assess treatment adherence of patients living in a low resource setting on HAART by using electronic monitors. Adherence, even in the early stages of treatment, appears to be insufficient in some patients and may be below the level required for continuous inhibition of viral replication. This approach may lead to improved targeting of counselling about their medication intake of such patients in order to prevent occurrence of resistant viral strains due to inadequate inhibition of viral replication. In this pilot study a significant difference between the data recorded through the electronic monitors and those provided by self-reporting was observed.

Keywords: HAART, MEMS CAPS, Adherence

Introduction

Botswana is one of the countries worst affected by the HIV pandemic with a prevalence of approximately 17% of the entire population [1]. An estimated 38.5% of those aged 15–49 years are HIV-positive, and it is estimated that one in every eight children is born with HIV [2].

Since 2002 the nation has embarked on the provision of antiretroviral drugs for all its eligible citizens by implementing the MASA program.(The national antiretroviral therapy program was given the name MASA, the Setswana world for “dawn”).

The use of potent antiretroviral combinations has provided unprecedented opportunities for effectively treating HIV disease by suppressing viral replication and has led to dramatic decline in HIV mortality [3, 4].

Adherence to antiviral regimens in HIV infected patients is essential for adequate suppression of viral replication. When adherence falls below a certain level, intermittent viremia will occur, and this may increase the chance of the development of resistant strains possibly followed by therapy failure [5–7].

In contrast, nonadherence to the prescribed antiretroviral regimens is associated with a rapid selection of resistant HIV strains resulting in treatment failure [8, 9].

The required high level of antiretroviral drug adherence in a poor resource setting remains therefore a serious concern. Assessment of adherence in HIV patients such as in this pilot-study may also provide tools to allow feedback and education on an individual health care provider–patient base.

For this reason patients in the Botswana Infectious Disease Care Centers (IDCC) treatment program are urged at each visit to the IDCC facility to comply with the prescribed ART regimen. This occurs in three stages: (1) in group instruction sessions together with other HIV patients and individual counselling by a trained nurse or pharmacist, (2) by their individual health care provider (physician), and (3) by the pharmacist. In addition, patients are usually accompanied by a close family member who is asked to assist or remind patients of the pill intake (adherence partner).

Reliable information about the actual tablet intake is a prerequisite for any form of management or modification of the adherence to therapy. It has been recognised that many of the traditional methods of assessing adherence such as pill counts, diaries, or self-reports are unreliable. Electronic monitoring enables the recording of the time points of pill bottle openings. This method also has drawbacks and may underestimate adherence [10] and, of course, it does not provide evidence of actual ingestion of the drug [11]. Despite these drawbacks it has been so far the closest to a gold standard for adherence measuring [12], although other methods remain of value.

A new method to measure adherence to prescribed medication regimen is the use of electronic monitoring [10, 13, 14]. Such systems commonly rely upon a microprocessor located in the cap of the medication container, where time and date of each opening are recorded. Each cap opening and closing is assumed to reflect a single medication-taking event. The data stored in the microprocessor are transferred to a computer database and uploaded for analysis [11]. Other methods like self-reporting, pharmacy records, and pill counts tend to overestimate patient adherence by anywhere from 20–30% [15–21].

This study was designed as a pilot study to evaluate electronic adherence monitoring in an HIV infected patient group that was put on antiretroviral medication for the first time. A secondary objective was to compare the adherence measured by electronic monitoring with that of self-reporting by means of a medication diary.

Methods

Patients

Thirty consecutive patients were recruited into the study during the period 13–30 October 2005. All were patients with an AIDS-defining illnesses and/or CD4 cell counts< 200 cells/mm3 (uL) who were offered HAART according to the Botswana Guidelines on Antiretroviral Treatment [2]. All patients were ARV-naïve.

Design

This was a trial in which treatment-naïve patients were monitored with regard to adherence to prescribed anti-HIV medication. Patients were not informed about the use, blinded of the electronic monitoring system, and were only asked to return their pill-bottles at each visit to the pharmacy when they returned for a refill and a consultation. Patients were also supplied with a self-reporting form. The study did not involve study related interventions and the subjects were not required to change behaviour in any way. The subjects were informed that the medication was supplied in special containers that had to be returned to the clinic but not about the monitoring system to prevent bias. The study was approved by the hospital management and the chief physician of the department of internal medicine.

Treatment regimens

The treatment regimen used consisted of 2-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) plus 1 nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI). Patients started the recommended first-line treatment with three different agents. These were zidovudine and lamivudine in a combination tablet Combivir (CBV) plus efavirenz (EFV) or nevirapine (NVP).

Male and female patients who were not anaemic were prescribed Combivir medication whereas anaemic patients (Hb < 7.5 mmol) were given stavudine (d4T/Zerit) and lamivudine medication. The stavudine dose was adjusted according to bodyweight (30 or 40 mg).

All patients except females in the reproductive age category were given once daily EFV. All females of the former category were prescribed NVP at a 200 mg once daily dose for 14 days which, after assessing the liver function parameters, was increased to 200 mg twice daily.

The continuation of NVP or EFV was dependent on the absence of significant rise in hepatic enzymes (AST and ALT). Approximately 90% of those who started the NVP or EFV treatment are able to continue this medication. Patients returned to the IDCC after a month for a medical check and refill of their prescription unless clinical events dictated earlier visits to the clinic.

The treatment starters were booked to see the doctor after the first 2 weeks of therapy. After seeing the doctor, the self recorded medication card and the electronic monitors were collected, and the data stored in the microprocessor were transferred to a database in the computer. Following this, each bottle was refilled and provided with a new label with medication instructions. Most patients received a refill for a period of 1 month, some however for a shorter period. The potential side effects were discussed with each patient. The results of the first analysis of the electronic monitors were not used in any counselling.

The electronic monitors were MEMS IV Track Cap devices (Aardex, Zug, Switzerland) with a MEMS IV Communicator for read-out of the results.

Study endpoints

The primary study endpoint was the adherence level measured (over a minimal period of 6 weeks) by the percentage of days on which the patients took a correct dosing over the monitored period. Adherence was also expressed as the number of pill-intakes recorded on a self-reporting forms designed to reflect the intended schedule and timing of treatment.

In the event a patient opened his/her bottle more than was prescribed (surplus opening), it was assumed that the patient correctly took the prescribed pills. However, occasions on which a patient opened less than the prescribed dose frequency were considered as adherence failures.

Sequence and duration of trial period

Each patient was immediately given counselling and made familiar with the ART treatment. During the counselling session emphasis was given with regard to the need of strict adherence of the prescribed medication and to methods to prevent disease transmission. They were also informed about the self-reporting form and given a pen to mark taking a treatment with a cross.

ART medication was started thereafter and the adherence to the pill intake schedule was monitored by means of using electronic monitors and self-recording for a period of 6 weeks. At the start of the treatment, electronic monitors containing medication for a period of 2 weeks were provided. After an evaluation by the doctor at day 14 of treatment the electronic monitors and self-reporting form were collected and the data in the microprocessor were entered in the database. The electronic monitors were subsequently refilled with medication for the next period of 1 month. A new self-reporting form was also given.

Patients were given 2 (in case of Lamivudine/Zidovudine + NVP or EVF) or 3 electronic monitors (in case D4T, 3TC, and NVP or EFV).

Patients recruited in the study were asked to return the electronic caps and the self-reporting form on each occasion of a visit to the IDCC. A self-reporting form was issued at the start of the study. This form contains rows where the patient had to mark with x each time they took the pill at the correct time. As some people in Botswana could not read or write, this form was kept very basic. A pencil was given to every patient who participated in the study.

Results

A total of 30 HIV infected adults were enrolled in the study. In five patients full data could not be obtained because of various reasons. This leaves an evaluable group of 25 (9 male, 16 female; average age 35.6 years, range 22–55 years). Twenty patients completed the 6-week monitoring period and the mean follow-up period was 49 days (range 42–72 days).

The reasons for lack of follow-up in the five patients varied, but in three patients it was due to mortality. In these three cases, as the relatives or nursing staff did not know about the value of the medication bottle (due to the blinding of the patients), the bottles were not returned. One patient was admitted to hospital where the nursing staff discarded the pill bottles. One patient failed to return for follow-up. Full follow-up was not obtained in another five patients for various reasons. This included technical failure of the compliance monitor in two cases and a change in the return date of the subjects who then received a refill in a normal container. Adherence assessed from the dosing histories compiled by electronic monitoring are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Adherence (%) of the patients (n = 25) by MEMS caps and self-reporting

| Patient number | TC | Follow-up (days) | MEMS | Self report | Lamivudine /zidovudine (bd) | EFV (od) | Lamivudine (bd) | NVP (od/bd) | d4T (bd) | Drop out/non-retrievel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 11 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 3 | |||

| 2 | 2 | 70 | 95 | 100 | 91 | 100 | ||||

| 3 | 2 | 14 | 100 | No data | 100 | 100 | 3 | |||

| 4 | 1 | 51 | 98 | 100 | 98 | 100 | ||||

| 5 | 4 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1 |

| 6 | 1 | 44 | 71 | 100 | 71 | 95 | ||||

| 7 | 3 | 45 | 73 | 70 | 92 | 81 | 96 | |||

| 8 | 1 | 44 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| 9 | 2 | 44 | 98 | 100 | 100 | 98 | ||||

| 10 | 2 | 14 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 3 | |||

| 11 | 1 | 44 | 88 | 100 | 88 | 98 | ||||

| 12 | 2 | 43 | 93 | 100 | 93 | 93 | ||||

| 13 | 1 | 44 | 98 | 89 | 98 | 100 | ||||

| 14 | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 2 |

| 15 | 2 | 44 | 93 | 100 | 98 | 93 | ||||

| 16 | 2 | 15 | 62 | 100 | 100 | 62 | 3 | |||

| 17 | 2 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 2–1 |

| 18 | 2 | 44 | 84 | 100 | 84 | 86 | ||||

| 19 | 2 | 45 | 98 | 100 | 98 | 100 | ||||

| 20 | 1 | 9 | 100 | No data | 100 | 100 | 3 | |||

| 21 | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1 |

| 22 | 1 | 72 | 75 | 100 | 75 | 94 | ||||

| 23 | 2 | 44 | 21 | 100 | 21 | 29 | ||||

| 24 | 2 | 42 | 93 | 100 | 93 | 95 | ||||

| 25 | 2 | 66 | 97 | 100 | 100 | 97 | ||||

| 26 | 1 | 43 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| 27 | 1 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | 4 |

| 28 | 1 | 49 | 94 | No data | 96 | 96 | ||||

| 29 | 1 | 56 | 100 | 100 | ||||||

| 30 | 1 | 47 | 20 | 100 | 20 | 100 | ||||

| avg | 42 | 85 | 98 | 89 | 98 | 92 | 87 | 96 |

Treatment codes (TC) are: 1 Lamivudine/zidovudine, Efavirenz (EFV); 2 Lamivudine/Zidovudine, Nevirapine (NVP); 3 Lamivudine, Nevirapine and stavudine (d4T); and 4 Lamivudine and Efavirenz. MEMS indicates the data combined for all different treatments. Patient numbers are not consecutive because patients who died have been omitted. Reasons for drop out and nonretrieval: 1 death; 2 MEMS thrown away; 3 missed by investigator (patients showed up on another date than the investigator expected); and 4 lost to follow-up

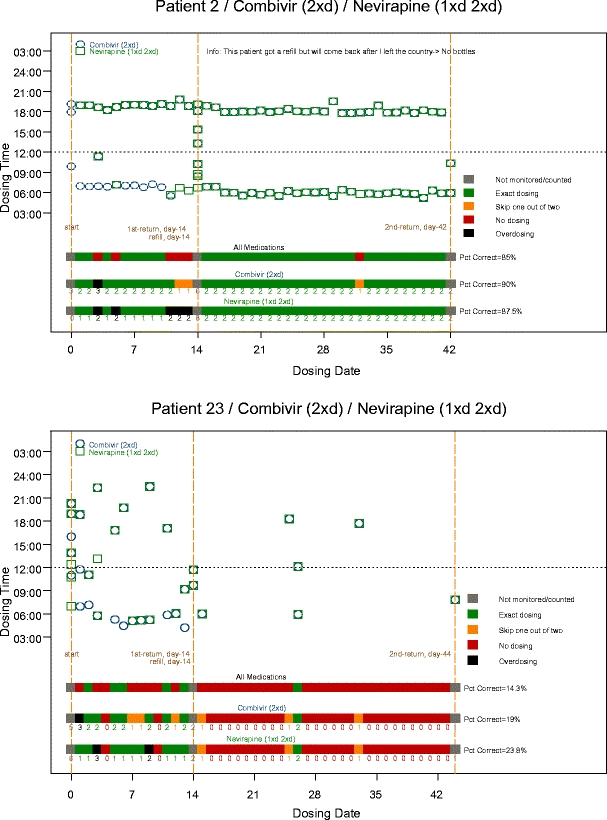

Assuming that surplus opening of the bottles was associated with correct medication intake, the mean adherence level was 85% (SD = 23%, range 20–100%). When surplus openings were calculated as incorrect, the adherence decreased to 70% (SD=23%, range 14–100%) (data not shown). Seven patients (23%) had an adherence under 90%, a level at which virological failure increases substantially [10]. Examples of the medication records obtained from the electronic monitoring device are shown in Fig. 1 for a patient with good adherence and a patient with low adherence to the regimen.

Fig. 1.

Examples of data of from patients with good and respectively poor adherence

Adherence assessed by means of self-reporting

The mean adherence assessed by means of self-reporting of medication intake was 98% with two (6%) patients recording adherence level lower than 90%. Adherence by self-reporting differed significantly from the adherence measured by the MEMS monitors method (p < 0.05, paired t-test). Three patients did not hand in their diary.

Discussion

In this pilot study we assessed the use of MEMS monitors to study the adherence to antiretroviral medication prescribed for HIV patients living in a low resource health care system. We demonstrated that assessment of adherence with this technique is feasible and may provide useful results. There was an approximately 30% drop-out rate of the recruited patients due to inability to recover data or early mortality. This may seem unacceptable in a well-resourced health care system. It is a reality in many countries where patients present with much more advanced disease, when there are sometimes great difficulties coming to the hospital, and patients can often not be reached by telephone or mail as they do not regularly have a postal address. It is likely that some association exists between failure to return to the hospital and adherence to the drug regimen and the current patient set therefore may reflect an overestimation of adherence.

Self-reporting of medication intake has been shown to be less reliable than the MEMS monitors [22, 23]. Therefore, it is not surprising that patients recorded adherence levels which were considerably higher compared with those assessed by the presumably more objective electronic monitors. Clearly, none of the methods used to measure adherence record actual intake of medication, and there are even indications that at least in some instances self-reporting is a more accurate record of adherence [24]. Despite these findings we consider the MEMS monitors more appropriate for a developing country with a larger potential for illiteracy. Patients knowledge about the monitoring of compliance will likely affect the absolute level of compliance [25], but there are no reasons why the relative ranking of compliance amongst patient groups is affected, and the device can still be used to improve adherence. In this study we chose not to inform the patients about the use of the monitoring device.

One of the critics often cited about the electronic monitor is that the opening of the bottle does not prove ingestion. However, it has been shown recently that projected plasma concentrations based on electronically compiled dosing histories correlates very well with directly measured concentrations [26]. It has also been shown that t in HIV patients electronically compiled dosing histories strongly correlates with viral suppression or the occurrence of virological failure [27]. It is therefore assumed that this method is a fair reflection of medication intake [28]. In this small study performed in HIV patients, some subjects opened their bottles more often than needed (surplus opening). Such surplus opening was not considered as nonadherence (in that case our reported adherence level would be lower). If surplus opening had led to extra intake of medication, it would not have contributed the endpoints of virological failure or the induction of resistance. We assume, therefore, that such surplus opening of the pill bottles had occurred for other reasons. Surplus openings occurred especially in the group of patients that had to take a once daily regimen together with twice daily regimens. These extra openings occurred often at the same time as when the prescribed twice-daily regimen was taken. This may have occurred because the patients were unsure about which bottle belonged to which medication. This may indicate that clearer labelling is essential, especially in an illiterate society. Under-opening most likely reflects nonadherence, although it cannot be excluded that in some cases patients removed several tablets at the same time. However, such behaviour is highly likely to increase the chance of erroneous medication intake and was for this reason registered as nonadherence.

Several studies have indicated that medication adherence lower than approximately 90% increases the chance of virological failure and the development of resistant virus strains [12, 28, 29]. The result of this pilot study indicates that even after careful counseling and guidance, a significant number of patients did not manage to adhere sufficiently to the twice-daily pill intake regimen. This observation study was too short to allow an analysis of the clinical impact of the observed low adherence in such patients on the development of virological failure. Additionally, reliable measurement of viral load was impossible in the hospital. However, our data did help to identify some patients with low adherence at the start of treatment and allowed a diversion of scarce resources for extra counseling for such patients.

The outcome of monitoring pill intake by the electronic monitors may therefore assist in timely counseling of patients with regard to their medication intake and persistence with the prescribed regimen.

Adherence measurements by means of using electronic monitors together with self and adherence partner recording of pill intake are likely to be useful in a much needed larger, long-term and more comprehensive adherence study in a low-resource health-care-system setting. Such a study can contribute to directed efforts to optimise the treatment of HIV-infected patients worldwide.

Acknowledgements

Support for the trial was obtained from GSK Netherlands by an unconditional educational grant and from Aardex Ltd., Zug, Switzerland.

References

- 1.Weiser S, Wolfe W, Bangsberg D, Thior I, Gilbert P, Makhema J et al (2003) Barriers to antiretroviral adherence for patients living with HIV infection and AIDS in Botswana. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 34(3):281–288 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.de Korte DF, Darkoh E, Mazonde P, Soni A, Hazelwood J, Narasimhan F et al (2004) Strategies for a national AIDS treatment programme in Botswana. ACHAP Program Reviews 1(1):1–11

- 3.Palella FJ Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA et al (1998) Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 338(13):853–860 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hogg RS, Heath KV, Yip B, Craib KJ, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT et al (1998) Improved survival among HIV-infected individuals following initiation of antiretroviral therapy. JAMA 279(6):450–454 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.DOHMH (2005) DOHMH recommendations for treating at-risk patients. AIDS Alert 20(4):39 [PubMed]

- 6.Masquelier B, Pereira E, Peytavin G, Descamps D, Reynes J, Verdon R et al (2005) Intermittent viremia during first-line, protease inhibitors-containing therapy: significance and relationship with drug resistance. J Clin Virol 33(1):75–78 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C et al (2000) Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med 133(1):21–30 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Vanhove GF, Schapiro JM, Winters MA, Merigan TC, Blaschke TF (1996) Patient compliance and drug failure in protease inhibitor monotherapy. JAMA 276(24):1955–1956 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Montaner JS, Reiss P, Cooper D, Vella S, Harris M, Conway B et al (1998) A randomized, double-blind trial comparing combinations of nevirapine, didanosine, and zidovudine for HIV-infected patients: the INCAS Trial. Italy, The Netherlands, Canada and Australia Study. JAMA 279(12):930–937 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Schwed A, Fallab CL, Burnier M, Waeber B, Kappenberger L, Burnand B et al (1999) Electronic monitoring of compliance to lipid-lowering therapy in clinical practice. J Clin Pharmacol 39(4):402–409 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Bova CA, Fennie KP, Knafl GJ, Dieckhaus KD, Watrous E, Williams AB (2005) Use of electronic monitoring devices to measure antiretroviral adherence: practical considerations. AIDS Behav 9(1):103–110 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Paterson DL, Potoski B, Capitano B (2002) Measurement of adherence to antiretroviral medications. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 31(suppl 3):S103–S106 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Dunbar-Jacob J, Erlen JA, Schlenk EA, Ryan CM, Sereika SM, Doswell WM (2000) Adherence in chronic disease. Annu Rev Nurs Res 18:48–90 [PubMed]

- 14.Farmer KC (1999) Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther 21(6):1074–1090 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Burney KD, Krishnan K, Ruffin MT, Zhang DW, Brenner DE (1996) Adherence to single daily dose of aspirin in a chemoprevention trial. An evaluation of self-report and microelectronic monitoring. Arch Fam Med 5(5):297–300 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Farmer KC (1999) Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther 21(6):1074–1090 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Frick PA, Gal P, Lane TW, Sewell PC (1998) Antiretroviral medication compliance in patients with AIDS. Aids Patient Care Stds 12(6):463–470 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Liu HH, Golin CE, Miller LG, Hays RD, Beck K, Sanandaji S et al (2001) A comparison study of multiple measures of adherence to HIV protease inhibitors. Ann Intern Med 134(10):968–977 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Schwed A, Fallab CL, Burnier M, Waeber B, Kappenberger L, Burnand B et al (1999) Electronic monitoring of compliance to lipid-lowering therapy in clinical practice. J Clin Pharmacol 39(4):402–409 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Wagner GJ, Rabkin JG (2000) Measuring medication adherence: are missed doses reported more accurately then perfect adherence? AIDS Care 12(4):405–408 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C et al (2000) Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med 133(1):21–30 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Farley J, Hines S, Musk A, Ferrus S, Tepper V (2003) Assessment of adherence to antiviral therapy in HIV-infected children using the Medication Event Monitoring System, pharmacy refill, provider assessment, caregiver self-report, and appointment keeping. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 33(2):211–218 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Chamot E, Coughlin SS, Farley TA, Rice JC (1999) Gonorrhea incidence and HIV testing and counseling among adolescents and young adults seen at a clinic for sexually transmitted diseases. AIDS 13(8):971–979 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Jonsson EN, Wade JR, Almqvist G, Karlsson MO (1997) Discrimination between rival dosing histories. Pharm Res 14(8):984–991 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Kruse W, Weber E (1990) Dynamics of drug regimen compliance-its assessment by microprocessor-based monitoring. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 38(6):561–565 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Vrijens B, Tousset E, Rode R, Bertz R, Mayer S, Urquhart J (2005) Successful projection of the time course of drug concentration in plasma during a 1-year period from electronically compiled dosing-time data used as input to individually parameterized pharmacokinetic models. J Clin Pharmacol 45(4):461–467 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Vrijens B, Goetghebeur E, de Klerk E, Rode R, Mayer S, Urquhart J (2005) Modelling the association between adherence and viral load in HIV-infected patients. Stat Med 24(17):2719–2731 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C et al (2000) Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med 133(1):21–30 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Conway B, Wainberg MA, Hall D, Harris M, Reiss P, Cooper D et al (2001) Development of drug resistance in patients receiving combinations of zidovudine, didanosine and nevirapine. AIDS 15(10):1269–1274 [DOI] [PubMed]