Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis is a common chronic disorder in children, especially in developed countries. It does not cause nasal symptoms only (such as congestion and sneezing) but may also cause general complaints such as fatigue and cough (box 1). It can also cause learning problems1 and has a great impact on quality of life. Uncontrolled allergic rhinoconjunctivtis may aggravate the symptoms of asthma.2 Although classic “hay fever” is easily recognised in children who have a runny nose, sneezing, and itchy eyes during the pollen season, the diagnosis of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis is often missed in children with perennial nasal congestion.

Box 1: Key symptoms of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children

Nasal

Blockage or congestion

Watery discharge

Sneezing

Itching

General

Cough

Fatigue, malaise, not feeling or looking well

Sore throat, repeated throat clearing

Halitosis, snoring, open mouth breathing

The term allergic rhinoconjunctivitis is preferable to allergic rhinitis because most patients also have ocular symptoms. In this review, we discuss the prevalence of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children, its causes, how it is diagnosed, and how it can be treated.

Sources and selection criteria

We used the Cochrane library to identify relevant systematic reviews on drugs for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children. Medline was searched for systematic reviews on diagnosis and treatment of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children using the keywords “rhinoconjunctivitis”, “systematic review”, “meta-analysis”, “diagnosis”, and “treatment”. We limited our searches to “all child”. We took additional references from our personal files.

SUMMARY POINTS

Most evidence on diagnosis and treatment allergic rhinitis and guidelines for the disease are based on adult studies

The disease has a high prevalence, a strong impact on quality of life and school performance, and may exacerbate allergic asthma

Initial treatment in primary care should be an individualised combination of allergen avoidance and pharmacotherapy

Nasal corticosteroids are the first line drugs for maintenance of persistent or severe intermittent disease

Sublingual immunotherapy should not be used in children until it has been shown to have clear benefits

How many children are affected?

The prevalence of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis has approximately doubled over the past 20 years.3 The prevalence of symptoms of rhinitis in children varies between countries, from 0.8% to 14.9% in 6-7 year olds and from 1.4% to 39.7% in 13-14 year olds. Environmental factors are probably responsible for these differences.4

Which allergens are involved?

The most important allergens involved in allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children include indoor allergens (present throughout the year, such as house dust mite and pet allergens) and outdoor allergens (seasonal, such as pollen from grass and trees). Food allergens do not cause allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. In population studies, about 40% of children with chronic nasal and ocular symptoms are not sensitised to any allergen (non-allergic rhinoconjunctivitis).3 5 The diagnosis and treatment of this disorder are similar to those of the allergic form.

What is the differential diagnosis?

Symptoms of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis are non-specific—they also occur during common viral upper respiratory tract infections. Arbitrarily, the duration of nasal symptoms in the common cold has been defined as <10 days.6 Therefore, children whose nasal symptoms of colds last longer than 10 days or those who seem to have colds all the time probably have allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. More rare causes of chronic nasal symptoms include mechanical stimuli (adenoidal hypertrophy, foreign bodies, deviated septum, polyps) and, occasionally, granulomas or malignancies.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children can be made by taking a history. Four key nasal symptoms exist (box 1). Children are often seen for a cough and malaise, and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis is only recognised when symptoms such as nasal congestion, discharge, and itch are specifically asked for.1 The probability of this diagnosis quadruples in adults if symptoms are associated with animal or pollen triggers.7 Children with the condition have twice the likelihood of a history of asthma, eczema, chronic sinusitis, and otitis media with effusion than healthy children.5

Physical examination

The diagnostic value of the findings of physical examination in allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children has never been formally studied. Classic findings include “allergic shiners”—darkening of the lower eyelids as a result of suborbital oedema (fig 1); the “allergic salute”—the upward rubbing of the nose with the palm of the hand to relieve nasal itching (fig 2); the “allergic crease”—a transverse white line across the nasal bridge caused by the allergic salute (fig 3); and watery red eyes—a sign of conjunctivitis (fig 1).

Fig 1 Darkening of the lower eyelids as a result of suborbital oedema (allergic shiner)

Fig 2 The upward rubbing of the nose with the palm of the hand to relieve nasal itching (the allergic salute)

Fig 3 A transverse white line across the nasal bridge caused by the allergic salute (the allergic crease)

Tests for allergic sensitisation

It is useful to screen for sensitising aeroallergens so that patients can be counselled on allergen avoidance. Skin prick tests or the measurement of specific IgE antibodies in blood are equally reliable tests.7 Either test can be performed in primary care. The accuracy of the skin prick test, however, depends on the skill and experience of the person performing the tests. In Western Europe, screening should include house dust mite, grass and tree pollen, and pet allergens. Screening for food allergens is not necessary.

Additional examinations

No other examinations are indicated. Complicated cases or those that are resistant to treatment may be referred to an ear, nose, and throat specialist, in which case nasal endoscopy and computed tomography scanning of paranasal sinuses may be considered.

Quality of life

Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis can have a severe effect on daily life. A World Health Organization working group put forward a new classification system for this condition in adults and children, including both pattern and severity of symptoms (box 2).8 The most commonly used method of measuring quality of life is the paediatric rhinoconjunctivitis quality of life questionnaire.9 Whether this helps in the management of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis is unclear.

Box 2 Classification of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children8

Pattern of symptoms

Intermittent: symptoms are present for fewer than four days a week and for fewer than four weeks

Persistent: symptoms are present for more than four days a week and for more than four weeks

Severity of symptoms

Mild

-

None of the following items are present:

- no sleep disturbance

- no impairment of daily activities, leisure, or sport

- no impairment of school

- symptoms are not troublesome

Moderate to severe

-

One or more of the following are present:

- sleep disturbance

- impairment of daily activities, leisure, or sport

- impairment of performance at school

- troublesome symptoms

How is allergic rhinoconjunctivitis treated in children?

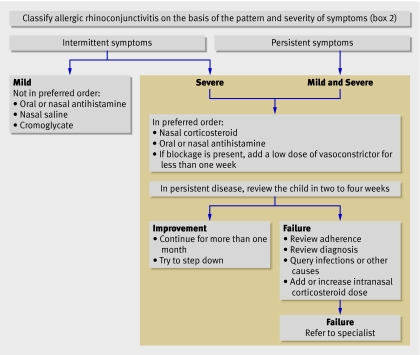

Management in primary care includes education of the patient and parent(s), avoidance of allergens and tobacco smoke, and pharmacotherapy. A stepwise approach is recommended, which depends on the severity of the disorder (box 2), the patient's preferences and adherence to treatment, and the presence of comorbidities such as asthma.8 10

Is allergen avoidance useful?

Few data are available on the effect of allergen avoidance in children with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Complete avoidance of allergens is undoubtedly effective—children with seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and allergy to pollen are symptom-free out of the pollen season. How much allergen exposure needs to be reduced to have a beneficial effect is unknown, however, and whether a major reduction in exposure can be achieved in “real life” is unclear.

A recent position paper summarised the evidence for the effectiveness of environmental control measures in the management of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma.11 Avoidance of mite allergen in children with asthma who are sensitised to house dust mites is effective (evidence from several randomised controlled trials). A comprehensive intervention to reduce exposure to mite allergens, cockroach allergens, pet allergens, and tobacco smoke in children in the United States improved asthma symptoms.12 No data were reported on rhinoconjunctivitis symptoms in these children.

A systematic review (four small studies of poor quality) on mite avoidance in allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children found no effect.13 In a randomised controlled trial in 279 children and adults, exposure to mite allergen was reduced by 30%, but rhinitis symptoms did not improve.14

Only two small studies examined the effects of avoidance of pet allergens in children with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. One found no effect, and the other showed some effect of a combined intervention for mites and pets.11

Although no studies examined the effect of reducing exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, because of comorbid conditions, such exposure should be avoided.

Drugs

The number of studies performed in children is small; therefore, data from adults are often extrapolated to children, and it is assumed that the principles of treatment are the same in both populations. The algorithm of treatment of children with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis that we propose is also adapted from adults (fig 4). This algorithm is likely to change if more clinical trials are done in children.

Fig 4 Recommended algorithm for the management of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children (adapted from adults10)

Intranasal glucocorticosteroids

A systematic review showed that intranasal glucocorticosteroids are the most effective treatment of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in adults.15 They reduce nose and eye symptoms and the use of other drugs, and they improve overall daily functioning. They are more effective than antihistamines (evidence from a systematic review of randomised controlled trials).15 A systematic review of nasal corticosteroids in children with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis applied such strict selection criteria that only three small old studies with methodological flaws were included.16

The most common local side effect is epistaxis (nose bleeds), which occurs in 17-23% of patients, although it is also common (10-15%) in patients treated with placebo in clinical trials.17 Therefore, local trauma caused by the nozzle of the nose spray probably causes epistaxis in many cases, rather than the drug itself. Application of a nasal cream containing vaseline usually solves the problem.

Normal daily doses of most intranasal glucocorticosteroids have no systemic side effects in children. Growth retardation was not seen with one year of treatment with fluticasone, mometasone, budesonide, or triamcinolone (evidence from individual randomised controlled trials).18 19 20 21 Concurrent use of intranasal and inhaled fluticasone did not affect function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (evidence from a randomised controlled trial).22 However, intranasal beclomethasone for one year was associated with a reduced growth rate, so this drug should not be used in children.23

Antihistamines

Second generation H1 antihistamines (such as (levo)cetirizine and (des)loratadine) are effective and safe for treating allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children. They reduce malaise and may improve learning ability (evidence from a randomised controlled trial).24 First generation oral H1 antihistamines should not be used because of their effects on the central nervous system. Topical antihistamines have the benefit of rapid onset of action. They reduce nasal and ocular symptoms but have little effect elsewhere (evidence from several randomised controlled trials).8 These drugs are useful in children with symptoms limited to the nose or eyes.

Other drugs

No other drugs are currently recommended. Disodium cromoglycate is available over the counter but is less effective than intranasal steroids or antihistamines.8 Another disadvantage is that it needs to be taken four to six times a day.

The leukotriene receptor antagonist montelukast is more effective than placebo—it is as effective as oral H1 antihistamines but inferior to nasal steroids.25 Its use is not advocated in general practice because of the costs and the lack of data on long term effects.

Omalizumab (anti-IgE) improves symptoms and quality of life in adolescents and adult patients with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. However, treatment is expensive and burdensome because of monthly injections. It is not licensed for the treatment of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in children in Europe.

Intranasal decongestants relieve nasal congestion, irrespective of its cause, for a short period of time, without improving nasal itching, sneezing, or rhinorrhea. Prolonged use (>10 days) is not recommended because of rebound mucosal swelling.

Tips for non-specialists

Recommend the patient for consultation with a specialist (allergist, paediatric allergist, ear, nose, and throat specialist) if31:

The patient has severe complaints that do not respond to allergen avoidance and pharmacotherapy

Complications of rhinitis (sinusitis, polyps, or otitis) are present

Advice about allergen avoidance would be useful

Immunotherapy might be a reasonable option

What is the status of immunotherapy in children?

Systematic reviews on immunotherapy in children and adolescents with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis found no convincing evidence that any form of immunotherapy improves symptoms or the use of drugs.26 27 28 29 A recent well designed randomised double blind placebo controlled study showed no effect of two years of sublingual immunotherapy with grass pollen extract in 168 children aged 6-18 years with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and grass pollen allergy in primary care (evidence level 1b, evidence from an individual randomised controlled trial).30

Contributors: All authors helped interpret data from the literature, draft the article, and revise it critically for important intellectual content. They all approved the final version to be published. HdG is guarantor.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Baatenburg de Jong A, Rijdt JP te, Brand PLP. Cough and malaise in young children due to allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. [In Dutch.] Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2005;149:1545-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kocevar Sazonov V, Thomas J, Jonsson L, Valovirta E, Kristensen F, Yin DD, et al. Association between allergic rhinitis and hospital resource use among asthmatic children in Norway. Allergy 2005;60:338-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hakansson K, Thomsen SF, Ulrik CS, Porsbjerg C, Backer V. Increase in the prevalence of rhinitis among Danish children from 1986 to 2001. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2007;18:154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asher MI, Montefort S, Bjorksten B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 2006;368:733-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arshad SH, Kurukulaaratchy RJ, Fenn M, Waterhouse L, Matthews S. Rhinitis in 10-year old children and early life risk factors for its development. Acta Paediatr 2002;91:1334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fokkens W, Lund V, Bachert C, Clement P, Helllings P, Holmstrom M, et al. EAACI position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps executive summary. Allergy 2005;60:583-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gendo K, Larson EB. Evidence-based diagnostic strategies for evaluating suspected allergic rhinitis. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:278-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108(5 suppl):S147-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juniper EF, Howland WC, Roberts NB, Thompson AK, King DR. Measuring quality of life in children with rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1998;101:163-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bouquet J, van Cauwenberge P, Ait Khaled N, Bachert C, Baena-Cagnani CE, Bouchard J, et al. Pharmacologic and anti-IgE treatment of allergic rhinitis ARIA update (in collaboration with GA2LEN). Allergy 2006;61:1086-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Custovic A, Gerth van Wijk R. The effectiveness of measures to change the indoor environment in the treatment of allergic rhinitis and asthma: ARIA update (in collaboration with Ga2len). Allergy 2005;60:1112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan WJ, Crain EF, Gruchalla RS, O'Connor GT, Kattan M, Evans R, et al. Inner-City Asthma Study Group. Results of a home-based environmental intervention among urban children with asthma. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1068-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheikh A, Hurwitz B, Shehata Y. House dust mite avoidance measures for perennial allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(1):CD001563. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Terreehorst I, Hak E, Oosting AJ, Tempels-Pavlica Z, de Monchy JGR, Bruijzeel-Koomen CAAM, et al. Evaluation of impermeable covers for bedding in patients with allergic rhinitis. N Engl J Med 2003;349:237-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiner JM, Abramson MJ, Puy RM. Intranasal corticosteroids versus oral H1 receptor antagonists in allergic rhinitis: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 1998;317:1624-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al Sayyad JJ, Fedorowicz Z, Alhashimi D, Jamal A. Topical nasal steroids for intermittent and persistent allergic rhinitis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(1):CD003163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Waddell AN, Patel SK, Toma AG, Maw AR. Intranasal steroid sprays in the treatment of rhinitis: is one better than another? J Laryngol Otol 2003;117:843-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen DB, Meltzer EO, Lemanske RF Jr, Philpot EE, Faris MA, Kral KM, et al. No growth suppression in children treated with the maximum recommended dose of fluticasone propionate aqueous nasal spray for one year. Allergy Asthma Proc 2002;23:407-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schenkel EJ, Skoner DP, Bronsky EA, Miller SD, Pearlman DS, Rooklin A, et al. Absence of growth retardation in children with perennial allergic rhinitis after one year of treatment with mometasone furoate aqueous nasal spray. Pediatrics 2000;105:E22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy K, Uryniak T, Simpson B, O'Dowd L. Growth velocity in children with perennial allergic rhinitis treated with budesonide aqueous nasal spray. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006;96:723-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Möller C, Ahlström H, Henricson KA, Akerlund A, Hildebrand H. Safety of nasal budesonide in the long-term treatment of children with perennial rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy 2003;33:816-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheth KK, Cook CK, Philpot EE, Prillaman BA, Witham LA, Faris MA, et al. Concurrent use of intranasal and orally inhaled fluticasone propionate does not affect hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-axis function. Allergy Asthma Proc 2004;25:115-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skoner DP, Rachelefsky GS, Meltzer EO, Chervinsky P, Morris RM, Seltzer JM, et al. Detection of growth suppression in children during treatment with intranasal beclomethasone dipropionate. Pediatrics 2000;105:E23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simons FER, Simons SJ. Levocetirizine: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in children aged 6 to 11 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;116:355-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Razi C, Bakirtas A, Harmanci K, Turktas I, Erbas D. Effect of montelukast on symptoms and exhaled nitric oxide levels in 7- to 14-year-old children with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2006;97:767-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Röder E, Berger MY, de Groot H, Gerth van Wijk R. Immunotherapy in children and adolescents with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis: a systematic review. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2007. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Sopo SM, Macchiaiolo M, Zorzi G, Tripodi S. Sublingual immunotherapy in asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis; systematic review of paediatric literature. Arch Dis Child 2004;89:620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox LS, Linnemann DL, Nolte H, Weldon D, Finegold I, Nelson HS. Sublingual immunotherapy: a comprehensive review. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;117:1021-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson DR, Torres Lima M, Durham SR. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;(2):CD002893. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Röder E, Berger MY, Hop WC, Bernsen RM, de Groot H, Gerth van Wijk R. Sublingual immunotherapy with grass pollen is not effective in symptomatic youngsters in primary care. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;119:892-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dykewicz MS, Fineman S, Skoner DP, Nicklas R, Lee R, Blessing-Moore J, et al. Diagnosis and management of rhinitis: complete guidelines of the joint task force on practice parameters in allergy, asthma and immunology. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1998;81:478-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]