Abstract

Adjacent transfer RNAs (tRNAs) in the A- and P-sites of the ribosome are in dynamic equilibrium between two different conformations called classical and hybrid states before translocation. Here, we have used single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer to study the effect of Mg2+ on tRNA dynamics with and without an acetyl group on the A-site tRNA. When the A-site tRNA is not acetylated, tRNA dynamics do not depend on [Mg2+], indicating that the relative positions of the substrates for peptide-bond formation are not affected by Mg2+. In sharp contrast, when the A-site tRNA is acetylated, Mg2+ lengthens the lifetime of the classical state but does not change the lifetime of the hybrid state. Based on these findings, the classical state resembles a state with direct stabilization of tertiary structure by Mg2+ ions whereas the hybrid state resembles a state with little Mg2+-assisted stabilization. The antibiotic viomycin, a translocation inhibitor, suppresses tRNA dynamics, suggesting that the enhanced fluctuations of tRNAs after peptide-bond formation drive spontaneous attempts at translocation by the ribosome.

INTRODUCTION

The ribosome is a molecular machine that synthesizes proteins from amino acids through repeated cycles of transfer RNA (tRNA) selection, peptide-bond formation, and translocation. During peptide-bond formation, the peptide on the tRNA in the peptidyl (P) site of the ribosome is transferred and covalently linked to the amino acid on the tRNA in the aminoacyl (A) site of the ribosome. In translocation, the messenger RNA (mRNA) is moved by one codon and the tRNAs in the A- and P-sites are moved to the P- and exit (E)-sites, respectively. Although the rate of translocation is increased by elongation factor G (EF-G), spontaneous translocation can occur, demonstrating the intrinsic capability of the ribosome to carry out this function. Therefore, the dynamics of the ribosome immediately after peptidyl transfer may be intimately linked to the process of translocation.

The aminoacylation state of the A-site tRNA affects the rate (1,2) and accuracy (3) of translocation and the configuration of tRNA-binding sites (4,5). These results suggest that the product of the process of peptidyl transfer significantly lowers the energy barrier for coupled translocation of tRNAs and mRNA. The peptidyl-tRNA in the A-site and decacylated tRNA in the P-site have been proposed to adopt a hybrid configuration, with the codon-anticodon interactions remaining in the A- and P-sites on the small ribosomal subunit, and the 3′ ends of the tRNA moved to the P- and E-sites on the large ribosomal subunit; these hybrid states are called A/P and P/E, respectively (5). However, the exact binding sites for peptidyl tRNA and deacylated tRNA remain unclear, since the hybrid binding sites were not observed in cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) or x-ray crystallographic studies (6,7).

Previously, we provided evidence for the presence of the hybrid state based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between the two tRNAs (8). The lower FRET value, corresponding to a larger distance between the elbow regions of the tRNAs, was identified with the hybrid state as it became more populated with a peptidyl A-site tRNA than an aminoacyl A-site tRNA. The classical and hybrid states were found to be in dynamic equilibrium.

In this article, we present an in-depth analysis of the tRNA dynamics on the ribosome before translocation. To obtain a better understanding on the nature of RNA-based interactions before and after peptidyl transfer, we studied the effect of Mg2+ on the tRNA dynamics with and without an acetyl group on the A-site tRNA. We also studied the effect of viomycin, a translocation inhibitor, on the observed tRNA dynamics. The results presented here underscore the importance of intrinsic tRNA dynamics in ribosome function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The detailed protocol for preparing tight-couple 70 S ribosomes from Escherichia coli MRE600 is documented elsewhere (9).

Formyl-methionine-specific (tRNAfMet) or phenylalanine-specific (tRNAPhe) tRNAs were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) and were labeled with Cy3 and Cy5 (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) at position 8 of 4-thiouridine (s4U8) and position 47 of 3-(3-amino-3-carboxypropyl)uridine (acp3U47), respectively. Cy5-labeled tRNAPhe (hereafter denoted tRNAPhe (Cy5)) was aminoacylated with phenylalanine using RNA-free S100 enzyme extract. More details about dye labeling and aminoacylation procedures can be found in our previous work (8). N-acetyl-Phe-tRNAPhe (Cy5) was prepared as described previously (5). A 57-base-long RNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) derived from T4 gene 32 with biotin at the 5′-end was used as the mRNA. The default ribosome buffer for all experiments consists of 50 mM Tris-acetate (pH = 7.5), 100 mM potassium chloride, 5 mM ammonium acetate, 0.5 mM calcium acetate, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 6 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Ribosome complexes were formed by mixing tight-coupled ribosomes with mRNA and incubating at 37°C for 5 min. The reaction was then mixed with tRNAfMet (Cy3) and further incubated at 22°C for 10 min to fill the P-site. Finally, to fill the A-site, the reaction was mixed with either Phe-tRNAPhe (Cy5) or AcPhe-tRNAPhe (Cy5) and incubated on ice for 1 h. The final reaction was 0.5 μM of ribosome, 0.5 μM of mRNA, and 0.5 μM of tRNAs in ribosome buffer with 15 mM Mg2+. The ribosome complexes were purified away from unbound mRNA and tRNA by using size exclusion spin columns (MicroSpin S300 HR, Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK) divided into small aliquots, flash-frozen, and stored at −80°C. For each experiment, an aliquot is quickly thawed by incubation at 37°C for 2 min and kept on ice.

For single-molecule fluorescence microscopy, we used prism-type total internal reflection geometry on a commercial microscope (TE300, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). In a FRET scheme, molecules were excited by a 532 nm laser (CrystaLaser, Reno, NV), and fluorescence light was collected by a 60×, 1.2 numerical aperture water immersion objective (Plan Apo, Nikon). After passing through a 550-nm long-pass filter (E550LP, Chroma, Rockingham, VT), Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence light was spatially separated by a 650 nm dichroic mirror (650DCXR, Chroma) and imaged onto two halves of a charge-coupled device (Cascade:512B, Roper Scientific, Tucson, AZ) using a triplet lens (Newport, Irvine, CA). In a dual excitation scheme, molecules were excited by both 532 nm and 635 nm laser, and band-pass filters (HQ580/60M and HQ700/75M, Chroma) instead of the long-pass filter were used for Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence emissions. Laser powers at 532 nm and 635 nm incident upon the prism were ∼10 mW and ∼2 mW, respectively. The data of each image frame was saved onto the hard disk using custom-written software in Visual C++ (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). The data acquisition rate was limited by the data writing speed, and to improve the signal/noise ratio and accelerate the data acquisition rate, 3 × 3 hardware pixel binning was used. To obtain single-molecule fluorescence time traces, four-pixel binning was used for each molecule postacquisition. In all measurements reported in this article, we used a 25-ms exposure time to acquire 40 frames per second.

Quartz microscope slides (Finkenbeiner, Waltham, MA) were cleaned using a mixture of sulfuric acid and Nochromix crystals (Godax Labs, Cabin John, MD). Coverslips and the cleaned slides were first silanized in 2% v/v Vectabond (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA)/acetone for 3 min at 22°C and then incubated in 10% w/v polyethylene glycol/0.1 M sodium bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.5) for 90 min at 22°C. The polyethylene glycol mix consists of 99 mol % normal polyethylene glycol (PEG) (mPEG-SPA (monomethoxy PEG succinimidyl propionate), molecular mass 5,000 Da, Nektar, San Carlos, CA) and 1 mol % biotinylated PEG (Biotin-PEG-NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide), molecular mass 5,000 Da, Nektar).

For immobilization of ribosome complexes, the flowcell constructed from the PEG-coated slide and coverslip was filled with 0.1 mg/ml streptavidin and kept for 5 min. After rinsing with buffer, ribosomes are introduced into the flowcell at ∼100 pM. Ribosomes specifically bind the surface through the biotinylated mRNA and yield ∼200 fluorescent spots per field of view (∼65 μm × 130 μm). All single-molecule fluorescence measurements were performed at 22°C in the ribosome buffer containing an oxygen scavenging system (1% w/v β-D-glucose, 30 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.2 mg/mL glucose oxidase (Roche, Basle, Switzerland) and 0.5 μL/mL catalase (Roche), which reduces the photobleaching rate of Cy5.

RESULTS

Previously, two different complexes were formed by enzymatically binding Phe-tRNAPhe to the A-site of ribosomes with N-formylmethionine (fMet)-tRNAfMet and deacylated tRNAfMet, respectively, in the P-site; tRNAs in complexes prepared with fMet-tRNAfMet transition from the classical state to the hybrid state at a rate of 5 s−1, sixfold faster than those in complexes prepared with deacylated tRNAfMet (8). The difference in dynamics between the two complexes can result from the peptidyl transfer reaction occurring only in the former complex, different A-site tRNAs, or a combination of both. By preforming a dipeptidyl-tRNA and binding it to the A-site of the ribosome with deacylated tRNA in the P-site to replace the former complex, the difference in tRNA dynamics can be solely attributed to the difference of the A-site substrate.

Due to the difficulty of preparing an ample amount of natural dipeptyl-tRNA for complex formation, here we used a peptidyl tRNA analog that is readily synthesized. The N-acetyl-aminoacyl tRNA has shown similar properties to a natural peptidyl tRNA in terms of the affinity to the ribosomal A-site (1) and binding position (4). In tandem with aminoacyl tRNA, N-acetyl-aminoacyl tRNA has been used to study the effect of the aminoacylation state of the A-site tRNA on tRNA binding site (5) and translocation (3,10).

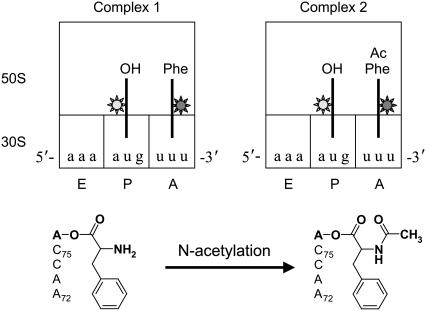

Two different ribosome complexes were prepared for our experiments. A Cy3-labeled deacylated tRNAfMet (OH-tRNAfMet (Cy3)) was loaded in the P-site first, and either a Cy5-labeled aminoacyl tRNAPhe (Phe-tRNAPhe (Cy5)) or a Cy5-labeled N-acetyl-aminoacyl tRNAPhe (AcPhe-tRNAPhe (Cy5)) was loaded in the A-site. The ribosome complex with OH-tRNAfMet (Cy3) in the P-site and Phe-tRNAPhe (Cy5) in the A-site will be referred to as complex 1, and the ribosome complex with OH-tRNAfMet (Cy3) in the P-site and AcPhe-tRNAPhe (Cy5) in the A-site, as complex 2 throughout this article (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Monitoring the FRET signal between A- and P-site tRNAs from two different kinds of ribosome complexes. The complex with Phe-tRNAPhe in the A-site is termed complex 1 and the one with AcPhe-tRNAPhe is termed complex 2. Both complexes have a deacylated-tRNAfMet in the P-site. FRET occurs from the Cy3 (light gray) on the P-site tRNA elbow to the Cy5 (dark gray) on the A-site tRNA elbow. The three binding sites are defined only for the 30 S small subunit. Thus, in our experiments, tRNAfMet is always in the P-site, and tRNAPhe is always in the A-site. The chemical modification of the α-amino group by acetylation is shown together with the 3′-end of the tRNA aminoacylated with phenylalanine.

Complex 1 mimics the state immediately before peptide-bond formation in terms of the placement of the 3′-ends of tRNAs (4,11) and the stability of tRNA binding (12). On the other hand, complex 2 can be regarded as the state immediately after peptide-bond formation. Therefore, comparison between complex 1 and complex 2 provides insights into tRNA dynamics before and after peptide-bond formation. We define the FRET value as ICy5/(ICy3 + ICy5), where ICy3 and ICy5 represent the measured Cy3 and Cy5 fluorescence intensities. Three major FRET states at ∼0, ∼0.4, and ∼0.75 are observed to be in dynamic exchange, confirming our previous results (8). The ∼0.75 and ∼0.4 FRET states correspond to the classical and hybrid states, respectively, as previously assigned. The exact nature of the 0-FRET state, where no fluorescence emission is detected from Cy5, is unclear because it can arise either from a Cy5 entering a nonfluorescent state or from a Cy5 being far away from Cy3 such that FRET is not detectable.

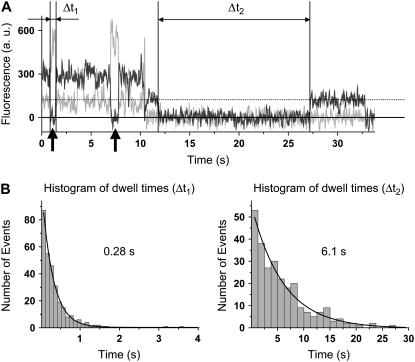

To distinguish these two 0-FRET states, we used a 635 nm laser as a probe laser to weakly excite Cy5 at all times. Between high FRET states (Fig. 2 A), Cy5 intensity occasionally drops to zero below the expected fluorescent level due to Cy5 excitation by the probe laser, indicating that the Cy5 molecule enters a nonfluorescent state. The observed reversible blinking dynamics of Cy5 is a repeated cycle of blinking of Cy5 by FRET excitation and photorecovery of Cy5 by 532 nm excitation, as also seen by other groups (13,14). We observe that the photoinduced recovery rate of Cy5 by 532 nm excitation is greatly enhanced by the presence of a fluorescently active Cy3 molecule in proximity (∼5 nm). After Cy3 is photobleached, the recovery rate of Cy5 is reduced more than 20-fold (Fig. 2 B). FRET fluctuations excluding the 0-FRET states reflect the actual tRNA dynamics.

FIGURE 2.

Probing the fluorescence state of Cy5 in 0-FRET events. (A) A typical time trajectory of Cy3 (light gray) and Cy5 (dark gray) fluorescence signals is shown (from complex 1). Lasers of 532 nm and 635 nm are switched on at all times, the former one to excite Cy3 for a FRET signal and the latter one to probe the fluorescence state of Cy5. The dotted horizontal line indicates the expected level of fluorescence signal when Cy5 is fluorescently active. The solid horizontal line indicates the background level when Cy5 is in the dark state or fluorescently inactive. The Cy5 signal during 0-FRET events indicated by the black arrows lies on the solid line below the dotted line, which directly proves that the 0-FRET events are caused by Cy5 blinking and not by tRNA dynamics. The dark events of Cy5 spanned by Δt1 and Δt2 represent reversible photobleaching events, but not photooxidation events, followed by photorecovery by the 532 nm excitation. (B) The fluorescence state of Cy3 affects the photorecovery rate of Cy5. Δt1 represents dwell times in the fluorescently inactive state of Cy5 while Cy3 is fluorescent, and Δt2 while Cy3 is not fluorescent. Dwell time histograms for Δt1 and Δt2 are shown. They are well fit to single exponential decays with lifetimes of 0.28 s and 6.1 s, respectively. The photorecovery rate is the inverse of the decay time. This rate is ∼24-fold faster when the Cy3-FRET pair is fluorescently active.

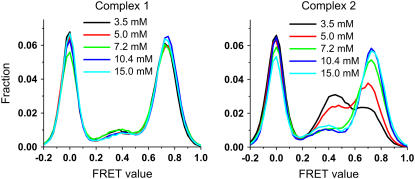

We characterized the tRNA dynamics by plotting the equilibrium histogram of FRET values observed from all molecules with a 25-ms integration time. The results from five different Mg2+ concentrations from 3.5 mM to 15 mM are shown in Fig. 3. The FRET distribution of complex 1 does not vary with [Mg2+], whereas for complex 2, the equilibrium fraction of the classical state increases with [Mg2+]. The apparent [Mg2+], where classical and hybrid states are equally populated, is ∼4 mM. Above [Mg2+] = 10 mM, FRET distributions of complex 1 and complex 2 are nearly identical. Dye properties of Cy3 and Cy5 might change as a function of [Mg2+], but we expect that the dye properties as a function of [Mg2+] would not be different between complexes 1 and 2 since the acetyl group in complex 2, the only chemical difference between the two complexes, is ∼7 nm away from the dye molecule. Therefore, we conclude that the observed Mg2+-dependent FRET fluctuations result from tRNA dynamics due to the presence of the acetyl group on the A-site tRNA.

FIGURE 3.

FRET value distribution as a function of Mg2+ concentration. Histograms of FRET values from complex 1 (left) and complex 2 (right) are obtained over five different Mg2+ concentrations (3.5, 5, 7.2, 10.4, 15 mM). Each FRET value is obtained with 25-ms integration time. The height or the frequency of occurrences of each histogram is normalized by the total number of data points.

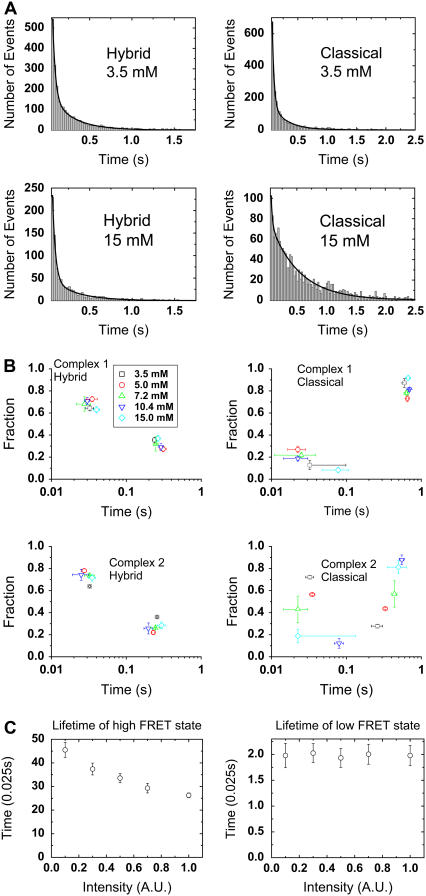

By building dwell-time histograms for the classical and hybrid states, one can extract the lifetime of each state. The fluorescence signals of Cy3 and Cy5 were first subjected to a two-point running average, and a threshold was found between the two peak FRET values, ∼0.75 and ∼0.4, that minimizes the number of transitions between the two states. In all cases, dwell-time histograms for the classical and hybrid states are well fit to a double-exponential decay. For example, curve fitting for dwell time histograms from complex 2 is shown in Fig. 4 A. Fitting with a double exponential decay model, A1 × exp (−t/τ1) + A2 × exp (−t/τ2), yields four parameters for each dwell time histogram, which are amplitude A1 and lifetime τ1 for the fast exponential decay, and A2 and τ2 for the slow exponential decay. We then estimated the frequency of occurrence of both kinetic states from the total number of dwells in each kinetic state, which is approximately proportional to the area under each exponential decay curve. The lifetimes (τ1, τ2) and the fractional frequencies of occurrence (F1, F2) of each kinetic state for different complexes and [Mg2+] are presented in Fig. 4 B as a two-dimensional scatter plot.

FIGURE 4.

Lifetime analysis of classical and hybrid states for complex 1 and complex 2. (A) Dwell time histograms for the classical and hybrid states of complex 2 are shown at two different [Mg2+], 3.5 mM and 15 mM. All histograms are fitted with a double exponential function, A1 × exp (−t/τ1) + A2 × exp (−t/τ2), and fitted curves are shown in black. The decay profile of the hybrid state is similar between the two [Mg2+]s, whereas the average lifetime of the classical state becomes significantly longer at [Mg2+] = 15 mM. (B) Apparent kinetics of the classical and hybrid states at five different [Mg2+]s is shown as two-dimensional scatter plots. All dwell-time histograms have two decay components, and each decay component is summarized by its lifetime along the x axis and its fractional frequency of occurrence along the y axis. The lifetimes (τ1, τ2) and fractional frequencies of occurrence (F1, F2) were obtained from the fitting parameters as explained in the main text. The error bars represent standard errors for the fitting parameters, which are computed from the variation of the fitting parameters across five different bootstrap data sets. [Mg2+] is specified by the same color scheme as in Fig. 3. (C) Monte Carlo simulation of apparent lifetimes as a result of Cy5 photophysics. Blinking and recovery rates of Cy5 were experimentally determined as a function of laser intensity. The intensity used throughout our experiments is defined to be 1. The unit of time is 0.025 s, which is our integration time. As an example, when the real lifetimes of the classical and hybrid states are taken to be 1.0 s and 0.05 s, the apparent lifetimes will be 0.6 s and 0.05 s at intensity = 1 according to this simulation. Therefore, the lifetimes we extracted, especially the ones for slow decay components, are likely to be shorter than the real values.

From Fig. 4 B, it is apparent that hybrid-state lifetimes of complex 1 and complex 2 are approximately independent of [Mg2+]. They are also approximately similar in value and distribution: the fast component at ∼0.03 s is ∼70% and the slow component at ∼0.25 s is ∼30%. However, the classical state lifetimes of complex 1 and complex 2 show different [Mg2+] dependence. The classical state lifetime of complex 1 does not vary significantly with [Mg2+]. The slow component at ∼0.65 s is ∼85% and the fast component at ∼0.03 s is ∼15%. For complex 2, the classical state lifetime is similar to that of complex 1 above 10 mM [Mg2+]. However, the fraction of the fast component increases, and the fraction of the slow component decreases as [Mg2+] is lowered toward physiological concentrations, 3.5 and 5.0 mM. To estimate the relative stabilities of the classical and hybrid states, we calculated average times (T) spent in each FRET state using the equation, T = F1τ1 + F2τ2. As shown in Table 1, the average classical state lifetime of complex 2 varies ∼5-fold over Mg2+ concentrations tested. All other average lifetimes remain relatively unchanged. We currently do not know the origin of the double exponential decay from the classical and hybrid states.

TABLE 1.

Average lifetimes of the classical and hybrid states at different [Mg2+]; uncertainties are the bootstrap errors from Fig. 4 B

| [Mg2+] (mM) | 3.5 | 5.0 | 7.2 | 10.4 | 15.0 | |

| Complex 1 | Hybrid (ms) | 105 ± 6 | 110 ± 15 | 97 ± 20 | 105 ± 8 | 122 ± 10 |

| Classical (ms) | 526 ± 24 | 476 ± 29 | 500 ± 26 | 556 ± 20 | 625 ± 22 | |

| Complex 2 | Hybrid (ms) | 112 ± 4 | 73 ± 4 | 88 ± 16 | 70 ± 20 | 110 ± 13 |

| Classical (ms) | 95 ± 18 | 161 ± 13 | 263 ± 54 | 500 ± 22 | 400 ± 17 |

The differences between all these decay times and our previously measured values (8) obtained at [Mg2+] = 15 mM and with a fMetPhe-tRNAPhe are less than twofold, which can be explained by different time resolution and excitation intensity. At the laser intensity used to acquire 25-ms resolution data (∼10 μW/μm2), the blinking of Cy5 is significant enough to bias the observed dwell times toward shorter values. This, in addition to the finite signal/noise ratio, will lead to an apparent lifetime shorter than the real lifetime of the particular state of interest. This effect can be demonstrated by a Monte Carlo simulation of FRET fluctuations among the classical, hybrid, and 0-FRET states due to Cy5 blinking. Given three states, i, j, and k, dwell times in state i are randomly chosen from exponentially distributed numbers with a decay rate equal to the sum of the two transition rates, ki→j and ki→k, and the next state is determined probabilistically based on the branching ratios, ki→j/(ki→j + ki→k) and ki→k/(ki→j + ki→k).

By repeating this procedure, a statistically consistent trajectory can be generated. Using blinking and recovery rates of Cy5 measured at the same laser intensity (0.8 s−1 and 4.4 s−1), the apparent lifetimes for classical and hybrid states can be compared to the real lifetimes of these states. For instance, taking 1.0 s and 0.05 s as the real lifetimes, Cy5 blinking makes the apparent lifetime of the classical state smaller than the real lifetime by as much as 40% (0.6 s vs. 1 s), whereas the lifetime of the hybrid state is not altered much from its real value (0.05 s vs. 0.05 s) (Fig. 4 C). Qualitatively, a process, the rate of which is comparable to or slower than the blinking rate, will appear faster than it actually is. Therefore, the lifetimes plotted in Fig. 4, especially the apparent lifetimes for the classical state, should be taken as lower estimates of the actual lifetimes.

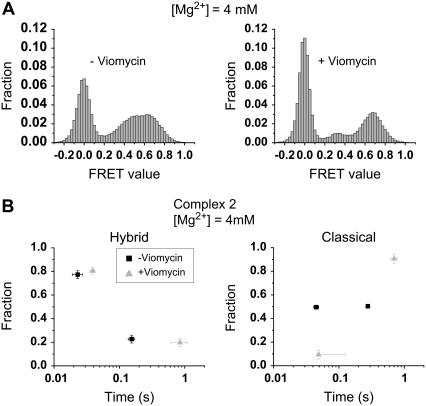

Using the observed FRET signal between the two tRNAs, we determined the effect of the antibiotic viomycin on tRNA dynamics. Viomycin is known to inhibit both EF-G-dependent and spontaneous translocation but not tRNA binding or peptide-bond formation (15,16). It likely binds at the 30–50 S subunit interface (17), stabilizes subunit association (18), and increases the affinity of tRNA to the A-site (16,19). When 100 μM viomycin is added to complex 2, which is the correct substrate for EF-G-dependent translocation, FRET fluctuations are significantly diminished, which is reflected as more clearly separated peaks in the FRET distribution (Fig. 5 A). The effect of viomycin on lifetimes of the classical and hybrid states at [Mg2+] = 4 mM is presented in Fig. 5 B. It changes the lifetime of the hybrid state by extending the lifetime of the slow component by more than sixfold. It also changes the lifetime of the classical state by extending the lifetime of the slow component by more than threefold and significantly suppressing the fraction of the fast component. Thus, tRNAs undergo slower fluctuations between the classical and hybrid states in the presence of viomycin.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of viomycin on the observed tRNA dynamics. (A) FRET value distributions, before (left) and after (right) the addition of 100 μM viomycin (bar graph), are compared at [Mg2+] = 4 mM. In the presence of viomycin, the FRET signal fluctuations are significantly reduced, which is reflected in better separated peaks in the FRET value distribution. (B) Lifetimes of hybrid (left) and classical (right) states are shown before (black square) and after (gray triangle) the addition of viomycin. The two-dimensional scatter plots are generated in the same fashion as in Fig. 4 B. Viomycin lengthens the longer lifetimes of the classical and hybrid state and reduces the fraction of the fast decaying component of the classical state.

DISCUSSION

In our previous work, tRNAs that are allowed to undergo peptide-bond formation were found to be less stable in the classical state (8). In this work, complex 2, formed without ribosome-catalyzed peptide-bond formation, is also less stable in the classical state than complex 1. Therefore, the previously observed difference in the stability of the classical state probably arose from the difference in the final aminoacylation state of tRNAs but not from the peptide-bond formation on the ribosome per se. The higher stability of the classical state of complex 1 might come from the absence of the acetyl group, presenting an α-amino group that can form stabilizing interactions in the A-site of the 50 S subunit. For example, at [Mg2+] = 3.5 mM, Keq, the apparent equilibrium constant between the classical state and the hybrid state is 5 for complex 1, and 0.8 for complex 2. Therefore, the difference of ΔG0 between complex 1 and complex 2 (ΔΔG0), where ΔG0 is the Gibbs energy of reaction, is RT × ln (5/0.8) = 4.5 kJ mol−1 at 22°C, consistent with formation of weak stabilizing interactions in the classical compared to the hybrid state.

In support of this possibility, a refined structure of ribosome complex with A- and P-site substrates shows that the α-amino group is indeed close enough to hydrogen-bond with the N3 of A-2486 (2451), the O2′ of A-2486 (2451), or the O2′ of A-76 of the P-site-bound tRNA (7). Two models that involve participation of these groups have been proposed (20,21). These groups may serve as hydrogen-bond acceptors to orient the attacking α-amino group of the aminoacyl-tRNA or be involved in metal ion coordination.

Results from structural and biochemical studies seem to favor the role of ribosomes in peptide-bond formation as an entropy trap (22), although we cannot completely rule out its role in chemical catalysis (21). Either way, frequent large-scale dynamic movements of tRNAs would be unfavorable for peptide-bond formation, which requires precise position and orientation of the two tRNA substrates. Our result on complex 1 shows that the ribosome indeed adopts a conformation that is mostly stable in the classical state as opposed to complex 2, in accordance with its need to carry out peptide-bond formation.

Mg2+ is important for structural stabilization of RNA and can affect RNA movement through specific binding (23) or electrostatic screening (24). The classical state lifetime of complex 1 is not affected by Mg2+, whereas that of complex 2 is highly sensitive to [Mg2+], increasing almost fivefold from 3.5 mM to 15 mM. The observation that these two complexes, only different by a single acetyl group in the peptidyl transferase center, show such a huge difference in Mg2+ dependence is surprising, all the more so considering the numerous tRNA-ribosomal RNA (rRNA) contacts in the ribosome (25). It is possible that hydrogen bonds through the α-amino group of Phe-tRNAPhe compensate for the stabilizing effect of Mg2+. Nonetheless, assuming that peptide bond forms in the classical state, this result indicates the robustness of the ribosome as a peptide-bond-forming machine in maintaining positional stability of substrates under all physiological [Mg2+], now believed to be in the range of 1–2 mM (26).

The relationship between lifetimes and [Mg2+] for complex 2 resembles that found from a small RNA junction (23), where the transition rate is [Mg2+]-insensitive in one direction but significantly decreases with [Mg2+] in the other direction. In that study, the Mg2+-dependent transition corresponds to an opening transition, which accompanies the breaking of tertiary contacts in RNA that are stabilized by specifically bound Mg2+ ions, whereas the Mg2+-independent transition corresponds to a spontaneous folding or closing transition. Similarly, more tertiary interactions that require Mg2+ ions might be present in the classical state than in the hybrid state, which can give rise to the observed dependence of transition rates on [Mg2+]. In this picture, movements of tRNAs with respect to the ribosome are more favorable in the hybrid state than in the classical state, and thus the hybrid state is likely the one translocated by EF-G.

Relevant conformational changes of the ribosome complex have been suggested from cryo-EM studies. In one study, a ribosome complex was trapped in an intermediate state where EF-G is bound in the GTP form, but the positions of tRNAs are unchanged with respect to the 30 S subunit (27). This intermediate state was found to possess a less compact structure, a wider mRNA entrance channel, and a skewed tRNA orientation compared to the state before peptide-bond formation (27). Although this translocation intermediate state requires EF-G to be seen in a cryo-EM map, it might be transiently present in the absence of EF-G, as predicted by a normal mode analysis using an elastic network model of the ribosome (28,29). Consistent with this observation and our results, we interpret that the classical state is more compact and has more Mg2+-stabilized RNA-RNA interactions than the hybrid state. Similarly, the classical and hybrid states can also be identified with the locked and unlocked states of the ribosome (30).

Our interpretation of the classical state as possessing more Mg2+-stabilized RNA-RNA interactions than the hybrid state is in agreement with the decrease of the rupture force between mRNA and a ribosome complex upon peptide-bond formation (31). It also explains the fact that backslipping of mRNA occurs during translocation when the A-site tRNA is not acetylated (3) under certain circumstances. If the A-site tRNA is not acetylated, the ribosome complex remains mostly in the classical state. Therefore, uncoupled movement of mRNA and tRNAs might occur when forcing translocation by EF-G upon a state where the mRNA channel is closed.

Finally, this work provided a crucial link between our observed tRNA dynamics and ribosomal conformational changes required for translocation by studying the effect of viomycin on the apparent rates. Viomycin, a known potent inhibitor of spontaneous and EF-G-dependent translocation, is also known to strengthen subunit association (18) and stabilize one or more alternate ribosome 50–30 S subunit conformations (32). This work observes a significant increase in tRNA fluctuations after acetylation of the A-site tRNA and that these fluctuations are suppressed by viomycin. In light of these collective findings, the increased tRNA dynamics we observe with acetylation of A-site tRNA suggests that the underlying subunit movements of the ribosome associated with translocation are triggered by the formation of the peptide bond between the amino acids presented by the P-site and A-site tRNA at the peptidyl transfer center of the ribosome.

CONCLUSION

By investigating tRNA dynamics of two different complexes mimicking ribosomal states before and after peptide-bond formation, we gained new insights into the flexibility of ribosome during translation. The main role of the ribosome before peptide-bond formation is to place two amino acid substrates linked to A- and P-site tRNAs in precise geometry. Thus, it requires a rigid conformation that prevents tRNA fluctuations. Stabilization might be achieved through the free α-amino group on the A-site tRNA, which provides a similar free energy decrease for the classical state as mM concentrations of Mg2+ ions. After peptide-bond formation, the ribosome or tRNAs enter a rapidly fluctuating mode, which can be suppressed by viomycin. There results underscore a possible linkage between these fluctuations and translocation.

Harold D. Kim's present address is Dept. of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138.

Editor: David P. Millar.

References

- 1.Semenkov, Y. P., M. V. Rodnina, and W. Wintermeyer. 2000. Energetic contribution of tRNA hybrid state formation to translocation catalysis on the ribosome. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7:1027–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Studer, S. M., J. S. Feinberg, and S. Joseph. 2003. Rapid kinetic analysis of EF-G-dependent mRNA translocation in the ribosome. J. Mol. Biol. 327:369–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fredrick, K., and H. F. Noller. 2002. Accurate translocation of mRNA by the ribosome requires a peptidyl group or its analog on the tRNA moving into the 30S P site. Mol. Cell. 9:1125–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moazed, D., and H. F. Noller. 1989. Interaction of transfer-RNA with 23s ribosomal-RNA in the ribosomal A-sites, P-sites, and E-sites. Cell. 57:585–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moazed, D., and H. F. Noller. 1989. Intermediate states in the movement of transfer-RNA in the ribosome. Nature. 342:142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agrawal, R. K., C. M. T. Spahn, P. Penczek, R. A. Grassucci, K. H. Nierhaus, and J. Frank. 2000. Visualization of tRNA movements on the Escherichia coli 70S ribosome during the elongation cycle. J. Cell Biol. 150:447–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmeing, T. M., A. C. Seila, J. L. Hansen, B. Freeborn, J. K. Soukup, S. A. Scaringe, S. A. Strobel, P. B. Moore, and T. A. Steitz. 2002. A pre-translocational intermediate in protein synthesis observed in crystals of enzymatically active 50S subunits. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanchard, S. C., H. D. Kim, R. L. Gonzalez, J. D. Puglisi, and S. Chu. 2004. tRNA dynamics on the ribosome during translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:12893–12898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim, H. D. 2004. Single molecule studies of dynamic biological processes. PhD thesis. Stanford University, Stanford, CA.

- 10.Fredrick, K., and H. F. Noller. 2003. Catalysis of ribosomal translocation by sparsomycin. Science. 300:1159–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen, J. L., T. M. Schmeing, P. B. Moore, and T. A. Steitz. 2002. Structural insights into peptide bond formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:11670–11675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fahlman, R. P., and O. C. Uhlenbeck. 2004. Contribution of the esterified amino acid to the binding of aminoacylated tRNAs to the ribosomal P- and A-sites. Biochemistry. 43:7575–7583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bates, M., T. R. Blosser, and X. W. Zhuang. 2005. Short-range spectroscopic ruler based on a single-molecule optical switch. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94:108101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heilemann, M., E. Margeat, R. Kasper, M. Sauer, and P. Tinnefeld. 2005. Carbocyanine dyes as efficient reversible single-molecule optical switch. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127:3801–3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geigenmuller, U., T. P. Hausner, and K. H. Nierhaus. 1986. Analysis of the puromycin reaction. The ribosomal exclusion-principle for AcPhe-tRNA binding re-examined. Eur. J. Biochem. 161:715–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Modolell, J., and D. Vazquez. 1977. Inhibition of ribosomal translocation by viomycin. Eur. J. Biochem. 81:491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moazed, D., and H. F. Noller. 1987. Chloramphenicol, erythromycin, carbomycin and vernamycin-B protect overlapping sites in the peptidyl transferase region of 23s-Ribosomal RNA. Biochimie. 69:879–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamada, T., and K. H. Nierhaus. 1978. Viomycin favors formation of 70s ribosome couples. Mol. Gen. Genet. 161:261–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peske, F., A. Savelsbergh, V. I. Katunin, M. V. Rodnina, and W. Wintermeyer. 2004. Conformational changes of the small ribosomal subunit during elongation factor G-dependent tRNA-mRNA translocation. J. Mol. Biol. 343:1183–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erlacher, M. D., K. Lang, N. Shankaran, B. Wotzel, A. Huttenhofer, R. Micura, A. S. Mankin, and N. Polacek. 2005. Chemical engineering of the peptidyl transferase center reveals an important role of the 2′-hydroxyl group of A2451. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:1618–1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinger, J. S., K. M. Parnell, S. Dorner, R. Green, and S. A. Strobel. 2004. Substrate-assisted catalysis of peptide bond formation by the ribosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:1101–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sievers, A., M. Beringer, M. V. Rodnina, and R. Wolfenden. 2004. The ribosome as an entropy trap. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:7897–7901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim, H. D., G. U. Nienhaus, T. Ha, J. W. Orr, J. R. Williamson, and S. Chu. 2002. Mg2+-dependent conformational change of RNA studied by fluorescence correlation and FRET on immobilized single molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:4284–4289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bokinsky, G., D. Rueda, V. K. Misra, M. M. Rhodes, A. Gordus, H. P. Babcock, N. G. Walter, and X. W. Zhuang. 2003. Single-molecule transition-state analysis of RNA folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:9302–9307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yusupov, M. M., G. Z. Yusupova, A. Baucom, K. Lieberman, T. N. Earnest, J. H. D. Cate, and H. F. Noller. 2001. Crystal structure of the ribosome at 5.5 angstrom resolution. Science. 292:883–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cromie, M. J., Y. X. Shi, T. Latifi, and E. A. Groisman. 2006. An RNA sensor for intracellular Mg2+. Cell. 125:71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frank, J., and R. K. Agrawal. 2000. A ratchet-like inter-subunit reorganization of the ribosome during translocation. Nature. 406:318–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tama, F., M. Valle, J. Frank, and C. L. Brooks. 2003. Dynamic reorganization of the functionally active ribosome explored by normal mode analysis and cryo-electron microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:9319–9323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, Y. M., A. J. Rader, I. Bahar, and R. L. Jernigan. 2004. Global ribosome motions revealed with elastic network model. J. Struct. Biol. 147:302–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Valle, M., A. Zavialov, J. Sengupta, U. Rawat, M. Ehrenberg, and J. Frank. 2003. Locking and unlocking of ribosomal motions. Cell. 114:123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uemura, S., M. Dorywalska, T. Lee, H. D. Kim, J. D. Puglisi, and S. Chu. 2007. Peptide bond formation destabilizes Shine-Dalgarno interaction on the ribosome. Nature. 446:454–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jerinic, O., and S. Joseph. 2000. Conformational changes in the ribosome induced by translational miscoding agents. J. Mol. Biol. 304:707–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]