Abstract

By performing homology modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations, we have developed three-dimensional (3D) structural models of both dopamine transporter and dopamine transporter-dopamine complex in the environment of lipid bilayer and solvent water. According to the simulated structure of dopamine transporter-dopamine complex, dopamine was orientated in a hydrophobic pocket at the midpoint of the membrane. The modeled 3D structures provide some detailed structural and mechanistic insights concerning how dopamine transporter (DAT) interacts with dopamine at atomic level, extending our mechanistic understanding of the dopamine reuptake with the help of Na+ ions. The general features of the modeled 3D structures are consistent with available experimental data. Based on the modeled structures, our calculated binding free energy (ΔGbind = −6.4 kcal/mol) for dopamine binding with DAT is also reasonably close to the experimentally derived ΔGbind value of −7.4 kcal/mol. Finally, a possible dopamine-entry pathway, which involves formation and breaking of the salt bridge between side chains of Arg85 and Asp476, is proposed based on the results obtained from the modeling and molecular dynamics simulation. The new structural and mechanistic insights obtained from this computational study are expected to stimulate future, further biochemical and pharmacological studies on the detailed structures and mechanisms of DAT and other homologous transporters.

INTRODUCTION

Dopamine transporter (DAT) is an important protein for movement and Parkinsonism. Its native substrate, dopamine, is a vital neurotransmitter for locomotor control and reward systems, including those lost or deranged in Parkinson's disease (1). DAT is also the primary target of cocaine. Cocaine is the most reinforcing of all drugs of abuse (2,3,4). Through binding with DAT, cocaine blocks the clearance (reuptake) of dopamine from central nervous system synapses and thereby prolongs dopaminergic neurotransmission in brain areas associated with reward. There are millions of individuals worldwide addicted to cocaine. Such a public health crisis has carried a substantial burden to the society in the form of increasing medical expenses, lost earnings, and increased crimes associated with psychostimulant abuse. There is no available medication approved by Food and Drug Administration to be used against cocaine addiction (1,5). The disastrous medical and social consequences of cocaine addiction have made the development of an effective pharmacological treatment a high priority (6–13).

Physiologically, DAT spatially and temporally buffers released dopamine at synaptic cleft, terminating dopaminergic neurotransmission and reaccumulating dopamine into presynaptic neurons. The transporting process can be roughly modeled as involving several different DAT states: bound state for dopamine and ions; intracellular unloading state of dopamine and ions; and finally extracellularly facing state as an unloaded carrier (14,15). Pharmacological studies have shown that dopamine transporting by DAT is Na+/Cl−-dependent. The overall stoichiometry is likely as dopamine/Na+/Cl− = 1:2:1 (16,17). Site-directed mutagenesis has been performed extensively on DAT to search for amino-acid residues responsible for the Na+ action, dopamine binding, and their coupling with the actions of cocaine (18–29). However, molecular mechanisms for these actions have appeared as complex and bewildering. A knock-in mouse model with functional DAT has been developed and found to be insensitive to cocaine (5). Such progress is paving the way of fully understanding the structure-function relationships of DAT system. However, structural details about the interactions of DAT with dopamine, cocaine, and its analogs remain to be uncovered. These facts make highly desirable a study on how the DAT interacts with its substrate.

DAT is a member of the neurotransmitter sodium symporters (NSS) family, belonging to the ion-coupled secondary transporters superfamily (STS) (30–34). The STS is known as the largest superfamily of membrane proteins of transporters with more than 1000 identified members to date (30). Driven by a solute gradient, these proteins transport ions, drugs, neurotransmitters, and other hydrophilic solutes. Some typical members of this superfamily have been structurally characterized through x-ray crystallography and, therefore, their possible transporting mechanisms have been explored. For example, the Glycerol-3-phosphate transporter (GlpT) (Protein Data Bank, i.e., PDB entry of 1PW4 with a resolution of 3.3 Å) operates by a singly-binding site, alternating-access mechanism (30). Another typical example is the Lactose permease (LacY, PDB entry of 1PV7 with a resolution of 3.6 Å) as a representative of Lactose subfamily (31). Besides the protonated, inward-facing conformation of LacY with bound substrate, the outward-facing conformation open to the periplasmic side is considered to be required for the final substrate transport across the membrane. Transporters in NSS family usually use sodium and chloride electrochemical gradients to catalyze the thermodynamically uphill movements for a series of substrates such as serotonin and dopamine (31,34). More recently, the x-ray crystal structure for a bacterial homolog (LeuTAa) of NSS from Aquifex aeolicus was determined in complex with substrate leucine and two sodium ions (PDB entry of 2A65 at 1.65 Å resolution) (34). This structure is viewed as an extracellularly faced state with the bound substrate. The possible substrate-entry pathway was proposed to be along transmembrane helices 1, 3, 6, and 8, starting from the extracellular end of these helices to the substrate-binding site. LeuTAa shares similar topological features with GlpT and LacY, i.e., 12 transmembrane α-helices with intracellular localization of both N-terminal and C-terminal, and a large internal substrate-binding cavity on the midpoint of the membrane. However, LeuTAa is quite different from GlpT and LacY (31,32,34). It bears a pseudo-twofold helix packing axis between helices 1–5 and helices 6–10, whereas GlpT and LacY have such a twofold axis between helices 1–6 and helices 7–12. The substrate-binding site in LeuTAa is located among partially unwound transmembrane helices 1, 3, 6, and 8 with main-chain atoms and helix dipoles playing a key role in the binding of substrate and sodium ions (34). In GlpT and LacY, the hydrophilic cavity is among helices 1, 4, 5, 7, and 11. These three typical transporters with available x-ray crystal structures belong to different families of transporter proteins. Some molecular modeling has been performed on DAT, serotonin transporter (SERT), and noradrenalin transporter (NET) (35,36) by using Na+/H+ antiporter or LacY (31) as the template. Now it is obvious that these templates in previous modeling studies are not suitable for the homology modeling of any member of the NSS family. Hence, the predicted atomic interactions are not reliable. No experimental evidence has been reported to support the previously reported models from any kind of structural or biological studies. Therefore, the previously reported structural models of DAT, SERT, and NET are not good enough to be used for studying molecular interactions of psychotropic drugs with these transporters. With similar structural folding and physiological features as other NSS family members, LeuTAa has been viewed as the most reasonable template to study the substrate binding and transporting mechanism for NSS transporters, especially for dopamine transporter and serotonin transporter (5).

In this work, a new three-dimensional (3D) structural model of DAT has been constructed through homology modeling based on the most reasonable template, i.e., the LeuTAa structure (34), and refined by performing molecular dynamics (MD) simulations in the environment of lipid bilayer and solvent water. Based on the developed structural model of DAT, the substrate-binding mode has been determined through further molecular docking, MD simulations, and binding free energy calculations. Through MD simulations on both the DAT model without dopamine and the DAT-dopamine binding complex, a possible substrate-entry pathway has been proposed. The overall agreement between the computational results and available experimental data (16,21,25,26,28) demonstrates important structural features of DAT and its binding with substrate, providing some valuable insight into the molecular mechanism for DAT modulating dopamine reuptake.

COMPUTATIONAL METHODS

Homology modeling and structural optimization of DAT in a physiological environment

To understand how dopamine binds with DAT and further explore the possible substrate-entry pathway, a 3D structural model of DAT was built based on the x-ray crystal structure of LeuTAa (34) by using the Homology module from the InsightII software (Ver. 2000, Accelrys, San Diego, CA). The amino-acid sequence of human DAT was directly extracted from the NCBI databank (access No.: Q01959). The sequence alignment was generated by using ClusterW with the Blosum scoring function (37,38). The best alignment was selected according to both the alignment score and the reciprocal positions of the conserved residues among the NSS family. These include the NGGGF motif between transmembrane helix 1 and 2, and other residues around the Na+ binding sites in DAT. The first 55 residues at the N-terminal and the last 32 residues at the C-terminal were omitted because of no corresponding homolog sequence in the template. A piece of 25 residues inside extracellular loop 2 was manually skipped under the template to get a better alignment at the conserved positions of Pro176 and Glu215 of DAT with the template and other members in the NSS family, including glycine transporter and serotonin transporter. The sequence identity reached 20.4% and the whole sequence homology became 42.0% for the final alignment (Fig. 1). The coordinates of the conserved regions were directly transformed from the template structure (i.e., the x-ray crystal structure of LeuTAa (34)), while the nonequivalent residues were mutated from the template to the corresponding ones of DAT. The side chains of those nonconserved residues were relaxed by using the Homology module of InsightII to remove the possible steric overlap or hindrance with the neighboring conserved residues. The conformation of the inserted 25 residues inside extracellular loop 2 was searched from the internal database of InsightII software and the best fit was selected from the generated 10 candidates.

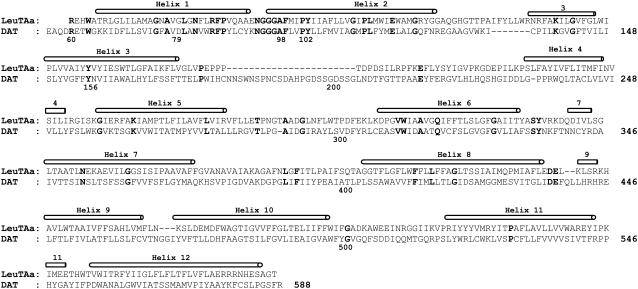

FIGURE 1.

Sequence alignment of human DAT with the bacterial homolog of Na+/Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporters (LeuTAa) by manual adjustment. Twelve helices are labeled above the sequence, and strictly conserved residues among the NSS family are shown in bold.

To simulate the actual physiological environment, the initial DAT model was inserted into a preequilibrated POPC lipid bilayer and then solvated by two layers of water molecules at each side of lipid bilayer. The POPC bilayer was generated by using the membrane plug-in of the VMD software (39) and the initial size of the membrane was expanded to be large enough to encompass the target protein. The geometry of POPC molecule was optimized by performing ab initio electronic structure calculation at the HF/6-31G* level using Gaussian-03 program (40). The HF/6-31G* calculation was also performed to determine the restrained electrostatic potential (RESP)-fitted charges for POPC molecules. The similar RESP-fitting calculations based on the first-principles electronic structure method were used in our previous computational studies of other protein-ligand systems and led to satisfactory binding structures (41–45). The relative orientation of DAT in the lipid bilayer was determined by referring the similar orientation of the LeuTAa structure (34), i.e., transmembrane helix 12 in parallel with the normal of the membrane, the binding sites of two Na+ placed at the midpoint of the membrane, and the two terminals (both N-terminal and C-terminal) intracellularly located. When inserting, any POPC molecule was removed if it had >50% of its nonhydrogen atoms within a distance of 2.5 Å to any nonhydrogen atoms of DAT. The solvent layers were added by using the LEaP module of AMBER8 program suite (46). The protein together with the lipid bilayer was solvated in a rectangular box of TIP3P water molecules (47) with a minimum solute wall distance of 10 Å. The redundant water molecules beyond the x,y boundary of the membrane were cut off to match the size of lipid bilayer. Standard protonation states at physiological environment (pH ∼7.4) were set to all ionizable residues of DAT, and the positions of protons were properly set on Nδ1 atom of His residues. Additional 4 Na+ were added in the solvent as counterions to neutralize the whole system. The final system size was ∼126 Å × 125 Å × 118 Å, composed of 154,114 atoms, including 351 POPC molecules and 32,390 water molecules.

After the whole system was set up, a series of energy minimizations (or geometric optimizations) were carried out by using the Sander module of AMBER8 program suite (46) with a nonbonded cutoff of 12 Å and a conjugate gradient energy-minimization method. The first 2000 steps of the energy minimization was done for the backbone of DAT while the side chains were fixed, and then the next 20,000 steps for the side-chain atoms with the backbone fixed. To get the solute (DAT) better solvated, the subsequent energy minimization and short-time MD simulations were performed on the environment (i.e., the lipid molecules, water molecules, and the counterions). After 50,000 steps of energy minimization on the environment, 80-ps MD simulations were performed on water molecules with NTV ensemble at T = 300 K. The environment was energy-minimized again for 20,000 steps followed by a 30-ps MD simulation on the lipid molecules. After these MD simulations, the environment and side chains of DAT were energy-minimized for 25,000 steps. Finally, the system was energy-minimized for 6000 steps for all atoms, and a convergence criterion of 0.001 kcal mol−1 Å−1 was achieved.

Molecular docking and binding free energy calculation

Based on the structural model of DAT obtained in this study, the binding mode of dopamine with DAT was explored through molecular docking by using the AutoDock 3.0.5 program and the DOCK 5.4 program (48,49). The two different docking programs were used for the same system for the purpose of increasing the number of possible candidates of the binding complex. The atomic charges of the protonated dopamine were also determined as the RESP charges determined by using the standard RESP procedure implemented in the Antechamber module of the AMBER8 program (46) after the electronic structure and electrostatic potential calculations at the HF/6-31G*. During the AutoDock docking process, a conformational search was performed using the Solis and Wets local search method (50), and the Lamarckian genetic algorithm (48) was applied to deal with the DAT-dopamine interactions. Among a series of docking parameters, the grid size was set to be 60 × 60 × 60 and the grid space was the default value of 0.375 Å. Similar grid size was used in the DOCK 5.0 docking operation, and the protonated dopamine molecule was flexibly treated by using the anchor-and-grow algorithm (49). The possible binding site in DAT was first roughly defined as a similar site in LeuTAa structure (34), i.e., the cavity around transmembrane helices 1, 3, 6, and 8. The binding site was then hunted by changing the center and the size of the docking grid. All the complex candidates were evaluated and ranked in terms of binding energy by using the standard energy score function implemented in the docking programs and the geometric matching quality.

As both the docking programs cannot consider the structural flexibility of the binding site during the docking process, further energy minimizations on those initially selected 20 complexes were performed in a similar way as described above, i.e., 10,000 steps with the fixed backbone of DAT, and then 15,000 steps or the convergence criteria 0.001 kcal mol−1 Å−1 reached for all of the atoms. The molecular mechanics (MM) method-based interaction energy for each of these energy-minimized 20 candidates was calculated according to the following equations,

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

where ΔEMM is the binding energy contributed from electrostatic and van der Waals interactions; Ecomplex, EDAT, and EDA were the energies of the complex, free DAT, and free dopamine, respectively. All these terms were calculated with the Sander module of the AMBER8 program (46). By this way of ranking and checking of geometric match quality, two complex structures were selected as the final candidates, and then subjected to more accurate binding free energy calculations by using the molecular mechanics-Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) method (51).

In the MM-PBSA calculations, the free energy of dopamine binding, ΔGbind, is calculated from the difference between the free energies of the complex (Gcomplex), the free DAT (GDAT), and free dopamine (GDA) as Eq. 3:

|

(3) |

The ΔGbind was evaluated as a sum of the changes in the MM gas-phase binding energy (ΔEbind), solvation free energy (ΔGsolv), and entropy contribution (−TΔS),

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

Electrostatic solvation free energy was calculated by the finite-difference solution to the Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) equation (ΔGPB) as implemented in the Delphi program (52,53). The dielectric constants used were 1 for the solute and 78.5 for the solvent. The SASA was calculated by the default surface area calculation program in the MM-PBSA module of AMBER8 program (46) with the default γ = 0.0072 kcal Å−2. In the MM-PBSA calculations, the lipid molecules were treated as part of the solute because DAT is a membrane protein. Keeping lipid molecules as part of the “solute” are helpful to reduce some possible systematic errors, especially for the calculation of ΔGPB. To avoid the insufficient accuracy of solvation energy calculation for metal ions by Delphi program, the two bound Na+ ions were removed only when calculating ΔGPB. The entropy contribution, −TΔS, to the binding free energy was calculated at T = 300 K by using the Nmode module of the AMBER8 program (46), which is based on a combination of the standard classical statistical formulas and normal mode analysis (54,55).

After the calculation of binding free energy, one of the two candidate structures was selected as the final DAT-dopamine complex based on its much lower binding free energy and higher quality of structural matching.

Molecular dynamics simulations

To explore the possible substrate-entry pathway, MD simulations were performed on the aforementioned DAT system by using the Sander module of AMBER8 (46). MD simulations were performed also for the purpose of making the extracellular loop 2 more reasonably folded after a sequence of 25 residues was inserted during the modeling of DAT structure. The whole system was gradually heated to 300 K by weak-coupling method (56,57) and equilibrated for ∼49 ps. Throughout the MD simulations, a 12 Å nonbonded interaction cutoff was used and the nonbonded list was updated every 1000 steps. The particle-mesh Ewald method (58,59) was applied to treat long-range electrostatic interactions. The lengths of bonds involving hydrogen atoms were fixed with the SHAKE algorithm (60), enabling the use of a 2-fs time step to numerically integrate the equations of motion. Finally, the production MD was kept running ∼2.167 ns with a periodic boundary condition in the NTP ensemble at T = 300 K with Berendsen temperature coupling and at P = 1 atm with anisotropic molecule-based scaling (56,57).

Similar MD simulations were also performed for 2.476 ns on the constructed DAT-dopamine complex for the purpose of further relaxation of the structure.

Most of the MD simulations were performed on the HP supercomputers (Superdome SDX and Linux cluster XC) at University of Kentucky Center for Computational Sciences. The other computations were carried out on SGI Fuel workstations and a 34-processor IBM x335 Linux cluster in our own lab.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structural model of DAT

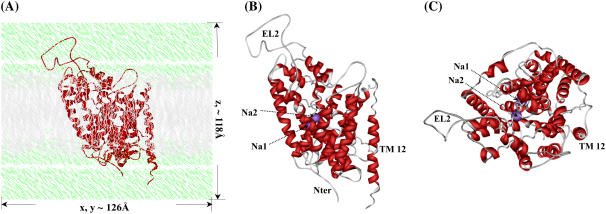

The amino-acid sequence alignment between human DAT and LeuTAa (Fig. 1) shows that 12 regions with high homology can be assigned to 12 α-helices. The assembly of these helices in a biological environment (Fig. 2 A) is structurally organized similar to the template LeuTAa (34). The whole model appeared to be a shallow glasslike shape opening toward the extracellular side and a pseudo-twofold axis between helices 1–5 and helices 6–10. The energy-minimized DAT structure (Fig. 2) has a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 0.13 Å for Cα atoms and 0.69 Å for all heavy atoms from the initial structural model. Compared with the template LeuTAa structure (34), the RMSD for Cα atoms of 12 transmembrane helices was only 0.52 Å. These small structural deviations suggest a high fidelity for the structure prediction of DAT. Like other bacterial homologs in the same family (61), the first 10 helices of DAT should act as the essential core structure for Na+/Cl−-dependent transporting. With inverted V-shape, helices 9 and 10 hold helices 3 and 8 like a pincer. By flanking the outer surfaces of helices 9 and 10, helix 12 protrudes the deepest into the intracellular side. Together with helix 9, helix 12 is situated probably at the interface of DAT dimer or other possible oligomers such as the tetramer (62,63).

FIGURE 2.

Initial structural model of human DAT in the physiological environment used for MD simulations. (A) DAT protein is represented as ribbon in red, lipid molecules in gray, and water molecules in green. Labeled also are the system sizes along x, y, and z axes. (B) Top view of DAT protein itself shown as ribbon in red, and Na+ ions as CPK in magenta. The Na+ ions, extracellular loop 2 (EL2), transmembrane helix 12 (TM12), and Nter are labeled. (C) Side view of DAT protein.

Our MD-simulated DAT model is considerably different from the previously reported DAT models (35,36). The major difference exists not only in the starting position and the length of each helix, but also in the assembly of 12 transmembrane helices. Furthermore, the second substrate (i.e., the two Na+ ions) (31) was not considered in the previous DAT models. These differences between the previous models and our current model are mainly due to the fact that the more reasonable template (34) was used in our DAT structure prediction. As noted above, the template (i.e., the structure of LeuTAa) used to build our model is in the same NSS family to which DAT belongs, whereas the previous models (35,36) were constructed from different templates, one from the Na+/H+ antiporter, and another from Lactose permease (31). The Na+/H+ antiporter and Lactose permease belong to different families of the ion-coupled secondary transporters superfamily; neither of these two templates shares the same family with DAT. In addition, the effects of the lipid bilayer and solvent molecules on the DAT structure were also accounted for in the structural optimization process (Fig. 2 A). The energy minimization on the system including the lipid bilayer and solvent molecules helped to improve the quality of interhelical packing and the helix-bilayer packing. The obtained model structure (Fig. 2) should be more reasonable than the previous models obtained from the in-vacuum modeling (35,36) In general, the existence of the membrane bilayer and solvent molecules is crucial for maintaining the proper folding of membrane proteins and their reasonable conformational changes necessary for the normal protein functions (64).

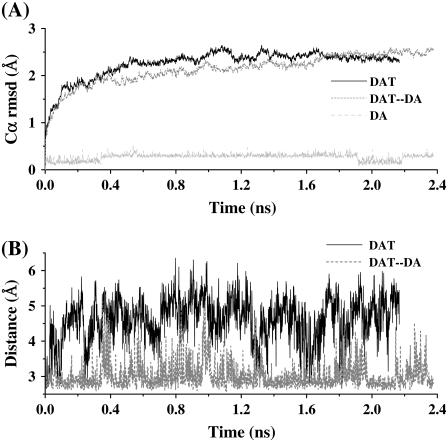

Based on the Cα RMSD changes during the MD simulation (black curve in Fig. 3 A), one can see that the optimized DAT structure became further relaxed after ∼0.4 ns of the significant structural perturbation. Such structural change during 0∼0.4 ns may be attributed to the dynamic packing effect by lipid molecules on the relative assembly of DAT helices. After ∼0.4 ns, the helix assembly of DAT became relatively stable as the Cα RMSD curve became quite flat.

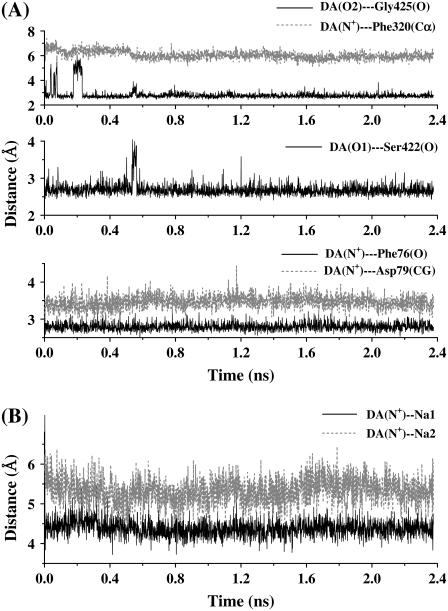

FIGURE 3.

Plots of the Cα RMSD and key distances in the simulated DAT and DAT-dopamine structures versus the simulation time (nanoseconds) during the MD simulations. (A) The DAT Cα RMSD, the Cα RMSD of the DAT-dopamine complex, and the RMSD of dopamine (DA) in the complex. (B) The minimum-distance changes between the positively charged side-chain atoms (NE, NH1, and NH2) of Arg85 and the negatively charged side-chain atoms (OD1 and OD2) of Asp476 in both the DAT and DAT-dopamine complex.

It is interesting to track the distance change between the positively charged side-chain atoms of Arg85 from helix 1 and the negatively charged side-chain atoms of Asp476 from helix 8 during the MD simulation (black curve in Fig. 3 B). As noted in the x-ray structure of LeuTAa (34), these two residues may also form an ion-pair in DAT without a substrate, and this ion-pair was supposed to be the major obstacle when the substrate is on the way to enter the binding pocket. There were hydrogen-bonding and strong electrostatic interactions between Arg85 and Asp476 in the starting DAT structure used for the MD simulation. During the MD simulation, the minimum distance between the side chains of these two residues became much larger and there was a very large fluctuation of the distance, indicating that the Arg85-Asp476 pair (salt bridge) was seldomly formed during the MD simulation and easy to be separated (Fig. 3 B).

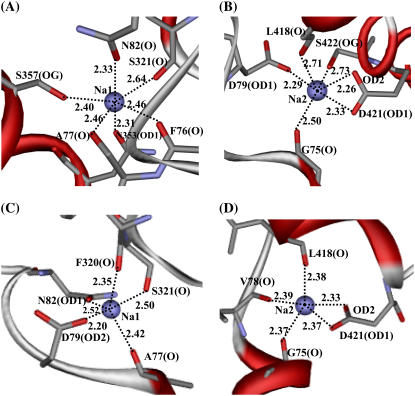

The Na+ ions were bound on the midpoint of the membrane, roughly around the unwound regions of helices 1 and 6 (Fig. 2, B and C). The major role of these two Na+ ions may be considered to stabilize the DAT core structure and the unwound helices 1 and 6. The two Na+ ions may also help to turn the DAT to externally facing form, thus allowing the access of the substrate to its binding site (16,17,20). In our starting structure of DAT used in the MD simulation, the first Na+ (denoted by Na1 in Fig. 2, B and C) was coordinated with the carbonyl oxygen of Ala77 (helix 1), side-chain carbonyl oxygen of Asn82 (helix 1), backbone carbonyl oxygen and side-chain hydroxyl oxygen of Ser321 (helix 6), and carbonyl oxygen of Asn353 (helix 7). In LeuTAa (34), the sixth coordination of the corresponding Na+ was from the carboxyl oxygen of the substrate. Correspondingly, the space around the sixth coordination of Na1 in DAT was squeezed by the surrounding backbone atoms. Tracking the coordination information in the MD trajectory, we found that the most conserved residues Ala77, Asn82, and Asn353 (Figs. 1 and 4 A) were always the ligands of Na1 (Table 1). Ser321 coordinated Na1 through its backbone carbonyl oxygen, but the coordination of its side-chain hydroxyl oxygen was replaced by the side-chain hydroxyl oxygen of Ser357. Further coordination by the backbone carboxyl oxygen of Phe76 made Na1 saturated to the typical hexacoordination and thus Na1 was stabilized in its binding site. During the MD simulation, Na1 had a fraction of 0.580 for hexacoordination and a fraction of 0.397 for pentacoordination. As shown in Fig. 4 A, for a typical DAT structure at 1.50-ns snapshot of the MD trajectory, most of the coordinating atoms interact with Na1 within an internuclear distance of 2.5 Å, except the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Ser321 with a distance of 2.64 Å. The details of the coordination for Na1 revealed in this MD simulation on DAT structure are all consistent with the observations from experimental studies for the existence of Na1 and its coupling with the substrate binding in DAT and SERT, suggesting a general structural feature around Na1 for NSS transporters (16,17,34).

FIGURE 4.

Representative local structures of DAT surrounding the Na+ ions (i.e., Na1 and Na2) captured at 1.50 ns snapshot of the MD simulations on DAT (A for Na1 and B for Na2) and DAT-dopamine complex (C for Na1 and D for Na2). In all cases, Na+ ions are shown in CPK style. The coordinating residues are shown in stick, and the protein in ribbon, representation. The coordinating distances are labeled.

TABLE 1.

Coordination details for the Na+ ions during the MD simulations for both the DAT model and its complex structure with dopamine

| DAT

|

DAT-dopamine complex

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ions | Residue | Atom | Fraction | Residue | Atom | Fraction |

| Na1 | Phe76 | O=C | 0.735 | Ala77 | O=C | 1.000 |

| Ala77 | O=C | 0.988 | Asp79 | OD2 | 1.000 | |

| Asn82 | OD1 | 0.998 | Asn82 | OD1 | 1.000 | |

| Ser321 | O=C | 0.991 | Phe320 | O=C | 0.995 | |

| Asn353 | O=C | 1.000 | Ser321 | O=C | 0.944 | |

| Ser357 | OG | 0.965 | ||||

| Ser321 | OG | 0.091 | ||||

| 4: 0.006 | ||||||

| Coordination No. and its fraction | 5: 0.397 | Coordination No. and its fraction | 5: 0.963 | |||

| 6: 0.580 | 6: 0.030 | |||||

| Na2 | Gly75 | O=C | 0.965 | Gly75 | O=C | 1.000 |

| Asp79 | OD1 | 0.948 | Val78 | O=C | 1.000 | |

| Leu418 | O=C | 0.911 | Leu418 | O=C | 0.994 | |

| Asp421 | OD1 | 1.000 | Asp421 | OD1 | 1.000 | |

| Asp421 | OD2 | 0.963 | Asp421 | OD2 | 1.000 | |

| Ser422 | OG | 0.741 | ||||

| Val78 | O=C | 0.032 | ||||

| Coordination No. and its fraction | 5: 0.200 | Coordination No. and its fraction | 4: 0.045 | |||

| 6: 0.780 | 5: 0.949 | |||||

A distance cutoff of 3 Å was used for the coordination criterion, and the fraction was calculated as the ratio of the number of snapshots with the coordination to the total number of snapshots taken from the stable MD trajectory. The fraction of each coordination number (4, 5, or 6) was calculated similarly.

The ligands of the second Na+ (denoted by Na2 in Fig. 2, B and C, and Fig. 4 B) in the starting DAT structure used in the MD simulation were mostly the backbone carbonyl oxygen atoms. These ligands were the carbonyl oxygen atoms of Gly75 (helix 1), Val78 (helix 1), and Leu418 (helix 8), the side chain OD1 of Asp79 (helix 1), and the side-chain atoms OD1 and OD2 of Asp421 (helix 8). As shown in Table 1 and Fig. 4 B, the most conserved residues Gly75 and Asp79 and the conservatively substituted Leu418 had very high fractions of the coordination to Na2 with short coordinating distances. Asp421 always coordinated to Na2 through the negatively charged side-chain atoms OD1 and OD2, which was the main source of electrostatic interactions. The coordination to Na2 by the side-chain hydroxyl oxygen of Ser422 was sometimes replaced by the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Val78, which only had a very small fraction of the coordination. The fraction of hexacoordination for Na2 was larger than that for Na1 by ∼0.200, as seen in Table 1.

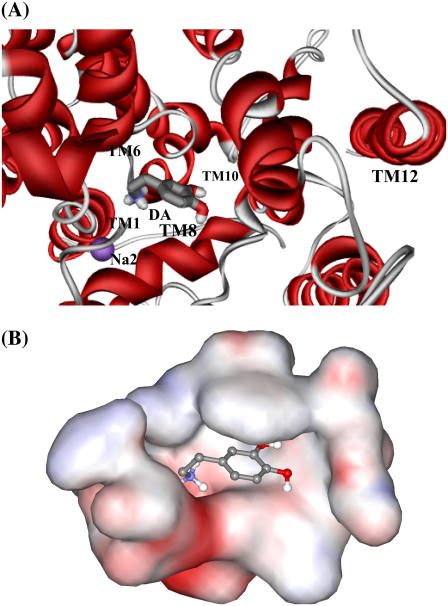

Complex model of DAT binding with dopamine

The dopamine-binding site in DAT was made by unwound regions of helices 1 and 6 and helices 3 and 8, which was close to the sites of Na+-binding, as seen in Fig. 5 A. In a typical structure of the MD-simulated DAT-dopamine complex at the 1.50-ns snapshot of the MD trajectory, dopamine was located in a totally dehydrated pocket (Fig. 5 B). The cationic head of dopamine was partially neutralized by the helix dipoles at the unwound regions of helices 1 and 6, and the negatively charged side chain of Asp79 from helix 1.

FIGURE 5.

Typical structure of the DAT-dopamine binding complex, which was the 1.50 ns snapshot of the MD trajectory. (A) Viewing the dopamine molecule (shown as ball-and-stick) in the complex model from the extracellular side. Only part of the DAT is shown as ribbon in red, and Na2 as CPK in magenta. Helices 1, 6, 8, 10, and 12 are labeled to indicate the relative position of dopamine in DAT. (B) Viewing the DAT in the binding pocket in the same orientation as panel A. The binding pocket is represented in molecular surface format, colored with electrostatic potentials in which blue is for positive and red is for negative potentials.

The dynamic behavior of the DAT-dopamine complex has been monitored by the Cα RMSD changes (Fig. 3 A), the Arg85-Asp476 paring (Fig. 3 B), the coordination information of Na+ ions (Fig. 4, C and D and Table 1), and the key distances from dopamine to several closely contacted residues and Na+ ions (Fig. 6). As shown in Fig. 3 A, during the first 2 ns of the MD simulation, the Cα RMSD change of DAT-dopamine complex was much smaller than that of the corresponding DAT structure without dopamine. More interestingly, Arg85 and Asp476 became a stable ion pair, as tracked by the minimum distance between the charged side chains of this pair of residues (Fig. 3 B), as the distance was <3 Å, at most, of the snapshots. These dynamic changes reveal that the Na+-bound DAT was stabilized by the binding of dopamine. In other words, the Na+-bound DAT can easily accept dopamine as a substrate. After binding with dopamine, the local intermolecular contacts became quite stable during the MD simulation (Fig. 6 A), although the Cα RMSD changes depicted in Fig. 3 A suggested a certain extent of backbone motion for the complex structure.

FIGURE 6.

(A) Distances from the atoms (the nitrogen and hydroxyl oxygen atoms) of dopamine to the carbonyl oxygen of Phe76, side chain CG of Asp79, Cα of Phe320, carbonyl oxygen of Ser422, and carbonyl oxygen of Gly425. (B) Distances from the cationic head of dopamine to the bound Na+ ions as observed during the MD simulation of the DAT-dopamine complex.

The coordination of Na1 was perturbed by the binding of dopamine. As listed in Table 1, Na1 kept Ala77 and Asn82 as its ligands, and it lost the coordination from Phe76, Asn353, and Ser357, while Asp79 and Phe320 became the new ligands of Na1. Meanwhile, Ser321 also restored its role as a ligand of Na1 (Fig. 4 C). It is worth noting that Asp79 switched its role from coordinating Na2 through its side chain OD1 in the DAT structure without dopamine to coordinating Na1 through its side chain OD2 in the DAT-dopamine complex. This was the most remarkable change in the local binding environment after the binding with dopamine, suggesting an indispensable role of this charged residue in the process of substrate-binding to DAT. Concerning the coordination of Na2, after the dopamine binding to DAT, the OD1 atom of Asp79 no longer coordinated to Na2 while its OD2 atom coordinated the Na1. The coordination of Na2 from the OD1 of Asp79 in the DAT structure without dopamine was replaced by the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Val78 (Fig. 4 D) in the simulated DAT-dopamine complex. Na2 kept its coordination from Gly75, Leu418, and Asp421, but its coordination from Ser422 was lost. Another significant change was the coordination numbers of both Na+ ions after the dopamine binding, i.e., from 6 in the DAT structure without dopamine to 5 in the DAT-dopamine complex (Table 1). The decreased coordination numbers of both Na+ ions can be attributed to both the steric and electrostatic effects of the positively charged dopamine. The MD-simulated average distances from the cationic head of dopamine to Na1 and Na2 (Fig. 6 B) were ∼4.5 Å and ∼5.5 Å, respectively. On the other hand, the repulsion between the positive charges was neutralized by the negatively charged Asp79 and partially by the surrounding helix dipoles.

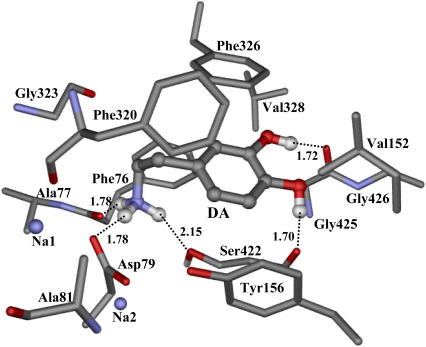

The detailed atomic interactions between dopamine and DAT are featured as electrostatic, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic contacts, as shown in Fig. 7 for a typical structure of the MD-simulated complex at the 1.50 ns snapshot. The hydrogen atoms on the positively charged head of dopamine formed three hydrogen bonds with DAT. One hydrogen bond was formed with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Phe76 from helix 1, the second was formed with the side chain OD2 of Asp79 from helix 1, and the third with the side-chain hydroxyl oxygen of Ser422 from helix 8. Meanwhile, the side-chain hydroxyl group of Ser422 had a hydrogen bond with the side chain OD2 of Asp421. The distance from the positively charged head of dopamine to the center of the aromatic side chain of Phe76 was as short as 4.18 Å. The nearest hydrogen atom on the cationic head of dopamine had a distance of 3.83 Å with the aromatic side chain of Phe76, indicating a cation-π interaction. The role of Asp79 from helix 1 was twofold. The side chain OD2 of Asp79 coordinated to Na1 and hydrogen-bonded to the cationic head of dopamine, while its side chain OD1 hydrogen-bonded to the side-chain hydroxyl group of Tyr156 from helix 3. The average distances from the nitrogen atom of the positively charged head of dopamine to the OD1 and OD2 atoms of Asp79 are within the range of effective electrostatic interactions (2.79 Å and 4.16 Å, respectively). The aromatic side chain of Tyr156 was in close side packing with the aromatic ring of dopamine (Fig. 7). Such strong interactions between dopamine and the side chains of Asp79, Tyr156, and Ser422 should be the major binding forces anchoring dopamine to its binding site. Tyr156 is a strictly conserved residue between all members in the NSS family (Fig. 1), and Ser422 is also conservative. Therefore, the mutual interactions between the side chains of Tyr156 and Asp79 may act as a latch to stabilize the irregular structure around the unwound region of helix 1. The involvement of Asp79 in the vital local interactions with both dopamine and Na+ can explain why mutations Asp79Ala, Asp79Gly, and Asp79Glu dramatically reduced dopamine reuptake as demonstrated in previously reported experimental studies on DAT (18,19). The mode of electrostatic attraction plus hydrogen bonding between Asp79 and the positively charged head of dopamine is also supported by a recent mutational study on the Asp79Glu mutant of DAT (24). The corresponding position of Tyr156 in other members of the NSS family has also been indicated in the substrate binding and translocation, such as in serotonin transporter and γ-aminobutyric acid transporter (65–67). The substrate binding was not investigated in the previous modeling studies on DAT (35,36).

FIGURE 7.

Representative molecular interactions between dopamine and DAT, taken at the 1.50-ns snapshot of the MD-simulated DAT-dopamine complex. Residues from DAT within 5 Å of dopamine are labeled and shown in stick style, while dopamine is shown in ball-and-stick. Critical hydrogen-bonding interactions between dopamine and DAT are represented as dash lines with labeled distances, also labeled the bound Na+ ions (Na1 and Na2).

In addition, the hydroxyl groups of dopamine formed two hydrogen bonds with DAT, one with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Ser422 and the other with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of Gly425 from helix 8. These two hydrogen bonds helped to orient the aromatic ring of dopamine in better parallel packing with the aromatic side chain of Phe326 from helix 6. Additional hydrophobic contacts between dopamine and DAT came from the hydrophobic side chains of several other residues. Side chains of Ala77, Ala81, and Phe320 interact with the alkyl chain of dopamine between its cationic head and aromatic ring. Gly426 and side chains of Val152 and Val328 added more contacts with the aromatic ring of dopamine.

As observed from the MD simulation, Phe76, Asp79, Ser422, and Gly425 had strong hydrogen-bonding interactions with the cationic head and hydroxyl groups of dopamine (Table 2). The total fraction of hydrogen bonding for each of these residues is always over 0.95 during the 2.476 ns MD simulation.

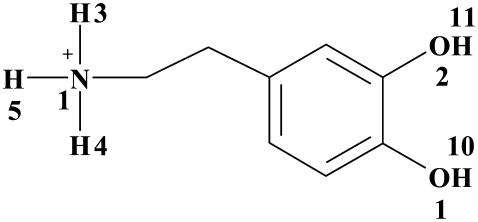

TABLE 2.

The hydrogen-bonding (HB) interactions between DAT and dopamine in the MD-simulated DAT-dopamine complex

| Residue | Donor | Acceptor | Residue | HBdist (Å) (SD) | Fraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DA | N1-H3 | O=C | Phe76 | 2.796 (0.11) | 0.731 |

| DA | N1-H5 | O=C | Phe76 | 2.794 (0.10) | 0.258 |

| DA | N1-H5 | OD2 | Asp79 | 2.839 (0.12) | 0.732 |

| DA | N1-H4 | OD2 | Asp79 | 2.850 (0.13)) | 0.253 |

| DA | N1-H4 | OG | Ser422 | 2.987 (0.15) | 0.618 |

| DA | N1-H3 | OG | Ser422 | 2.976 (0.17) | 0.211 |

| DA | O1-H10 | O=C | Ser422 | 2.672 (0.11) | 0.979 |

| DA | O1-H10 | O=C | Gly425 | 2.360 (0.15)) | 0.024 |

| DA | O2-H11 | O=C | Gly425 | 2.745 (0.14) | 0.953 |

The criteria/cutoffs used for the HB counting was 3.5 Å for the distance (HBdist) between the donor and acceptor atoms and 110° for the HB angle along the donor, hydrogen, and the acceptor. The HB fraction was calculated as the ratio of the number of snapshots with the HB to the number of total snapshots collected. All HB pairs with fractions over 1% and their average HBdist values are listed with the standard deviations (SD) in parentheses. See scheme below.

.

.

Comparison with available site-directed mutagenesis studies

Our modeled structures of DAT and its binding with dopamine can be used to understand the experimental results obtained from previously reported site-directed mutagenesis studies (18,19,22,28). As discussed above, according to our DAT model, the negatively charged atoms at the side chain of Asp79 interact with the cationic head of dopamine through the direct hydrogen-bonding and electrostatic interactions. Mutations on this residues, such as Asp79Ala and Asp79Gly, are expected to abolish these crucial interactions, and thus these mutations lead to the loss of the dopamine-reuptake function as reported by Uhl et al. (18). Asp79Glu mutation is also expected to significantly weaken its interactions with the cationic head of dopamine and the two Na+ ions, which explains why this mutation also dramatically reduced the dopamine reuptake (18). As reported also by Uhl et al. (19), Phe155Ala mutation caused only 3% decrease in the binding affinity of dopamine. According to our model of DAT in complex with dopamine, Phe155 is located just above the dopamine binding pocket, and the shortest internuclear distance between Phe155 and dopamine is >5 Å. The possible hydrophobic interaction between Phe155 with dopamine should be very weak, making this residue much less important than other residues inside the dopamine-binding pocket.

It has been known that Asp313Asn mutation decreased the Km for dopamine binding with DAT by sixfold (22), whereas Lys257A and Arg283Ala mutations increased the Km for dopamine binding with DAT by sixfold and threefold, respectively (28). Based on our modeled structures, the distance between the negatively charged atoms of Asp313 side chain and the cationic head of dopamine is ∼8 Å, whereas the distances from the cationic head of dopamine to the positively charged atoms of Lys257 and Arg283 side chains are ∼10 Å and ∼11 Å, respectively. In consideration of the long-range electrostatic interactions between the charged dopamine and these charged residues, with the Asp313Asn mutation, the net charge of the residue changes from −1 to 0 and, therefore, the favorable electrostatic attraction between Asp313 and dopamine is expected to vanish. With the Lys257 or Arg283 mutation, the net charge of the residue changes from +1 to 0 and, therefore, the unfavorable electrostatic repulsion between the residues and dopamine is expected to disappear. These results qualitatively explain why the Asp313Asn mutation decreased the Km for dopamine binding with DAT (22), whereas Lys257A and Arg283Ala mutations increased the Km for dopamine binding with DAT (28).

As observed in previously reported experimental studies, the Trp84Leu mutation on helix 1 and the Leu104Val, Phe105Cys, and Ala109Val mutations on helix 2 had no obvious effects on the Km value for dopamine binding with DAT (22,25,26). This is because these residues are far away from the dopamine-binding site according to our modeled structures. In addition, based on our modeled structures and the MD simulations trajectory, amino-acid residues His375 to Ile379 at the extracellular end of helix 7 belong to a loop and residue Glu396 is at the beginning of helix 8. Such a structural feature is also consistent with the key distances determined in a study of the structure-function relationship by performing the Zn2+-site engineering (20).

Binding free energy

In the MM-PBSA calculation of the binding free energy for the DAT-dopamine binding using the modeled structure before the MD simulation, we obtained ΔEbind = −21.6 kcal/mol and −TΔS = 16.0 kcal/mol at T = 298.15 K. Thus, the binding free energy (ΔGbind) between dopamine and DAT was calculated to be −5.6 kcal/mol by using the DAT structure before the MD simulation. Based on the calculated ΔGbind value, the dissociation constant (Kd) for the DAT-dopamine complex is estimated to be 7.8 × 10−5 M (or 78 μM). We also calculated the binding free energy by using the MD-simulated DAT-dopamine structure. The MM-PBSA calculations were performed on 120 snapshots (i.e., one snapshot per 10 ps) taken from the last 1.2 ns of the MD trajectory (see Fig. 3 A). For each of these 120 snapshot structures, we carried out the calculations on both the gas-phase binding energy and the solvent shift. The final results were taken as the averages of the corresponding energetic values calculated with the 120 snapshots. Based on the calculated results, the binding energy shift due to the MD simulation was determined to be −0.8 kcal/mol, i.e., ΔGbind (after MD) = −5.6 − 0.8 = −6.4 kcal/mol. Based on the ΔGbind value of −6.4 kcal/mol, the dissociation constant (Kd) is evaluated to be 20 μM, which is closer to the experimental ΔGbind value of −7.4 kcal/mol derived from the experimental KM value of 3.466 ± 0.200 μM (28). The deviation (∼1.0 kcal/mol) of the calculated binding affinity from the experimental value may be attributed to the approximations inherent in MM-PBSA method (51). For example, explicit solvent molecules were employed in the optimization and MD simulations of the DAT-dopamine complex model, but were subsequently replaced with a continuum solvent model in the calculation of the solvation free energy contribution (ΔGsolv) through solving the PB equation (52,53). A recently reported computational study (68) also demonstrated that the MM-PBSA method could significantly underestimate the binding free energy.

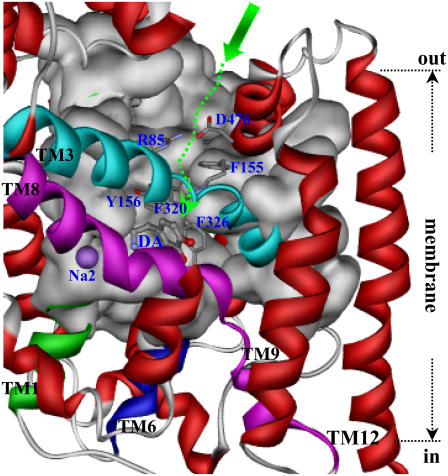

Substrate-entry pathway

Based on the MD-simulated DAT-dopamine complex structure, a top view on the dopamine binding site from the extracellular side shows that dopamine was positioned inside a hydrophobic pocket (Fig. 5). The cradlelike pocket was covered by the aromatic side chains of Phe320 and Phe326 and the hydrophobic side chain of Val152 (Figs. 7 and 8). This top cover of the binding pocket was further stacked by the side chains of Phe155 from helix 3, Arg85 from helix 1, and Asp476 from helix 10. Although the charged side-chain atoms of residues Arg85 and Asp476 were seldomly in direct charge-charge interactions, as indicated in the MD simulation on DAT (black curve in Fig. 3 B), the mutual interactions between these two residues were probably mediated by the surrounding solvent water molecules. These two charged residues were just over the top of Phe326 from helix 6. The NH groups of Arg85 side chain also formed a hydrogen bond with the carbonyl oxygen on the side chain of Gln317 from helix 6. Except these intramolecular interactions, the funnel-like tunnel formed by the helices 1, 3, 6, 8, and 10 was quite opening toward the extracellular side of the membrane bilayer (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 8.

Side view of the proposed dopamine-entry pathway in DAT with TM12 parallel to the normal of the membrane. The protein is shown as ribbon with helix 1 in green, helix 3 in cyan, helix 6 in blue, helix 8 in magenta, and other helices in red. With helices 3 and 8 in front, the back wall of the pathway is represented by molecular surface in gray, and residues 220–241 are not shown for clear view of the pathway back wall. The relative position of the membrane bilayer is indicated. The proposed substrate-entry pathway starts from the extracellular side as indicated by the large green arrow, going down inside the tunnel along the dashed green arrow to the binding pocket. The side chains of residues on the way of the tunnel to the binding pocket are shown in stick representation and labeled in blue. These are the salt-bridge pair of Arg85 and Asp476, aromatic residues as Phe155, Ty156, Phe320, and Phe326. Dopamine is labeled as DA and the second Na+ as Na2 in blue.

Considering the unwinding features of helices 1 and 6 around the midpoint of the membrane, it is not difficult for the up-half of helices 1 and 6 to move apart or toward each other by using the unwound regions of these two helices as the joint points. Such unique flexibility of the substrate-binding domain of DAT affords a possible, reasonable pathway for the entry of Na+ ions and substrate dopamine toward their binding sites. That is, once captured near the mouth in the extracellular side of DAT, dopamine molecule can slide down to the door of binding pocket (dashed green arrow in Fig. 8). By the help of electrostatic attraction from Asp476, the entering of dopamine probably brings about local motion of the up-half of helices 1 and 6. After further sliding of dopamine molecule toward the binding pocket, the charged atoms of Arg85 and Asp476 come closer to each other. In coupling with the dopamine molecule orientating in the binding pocket, the coordinations of both Na+ ions are adjusted. As a balance, the Arg85-Asp476 salt bridge is formed (Fig. 3 B), thus stabilizing the whole complex structure (Figs. 6 and 7).

CONCLUSION

This computational modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations have led us to develop a reasonable three-dimensional (3D) structural model of dopamine transporter (DAT) and its binding dopamine. Our modeled 3D structures of DAT and its complex with dopamine have provided some detailed structural and mechanistic insights concerning how DAT interacts with its substrates at atomic level, extending our mechanistic understanding of DAT modulating the dopamine reuptake with the help of Na+ ions. The general features of our modeled 3D structures are consistent with all of the available experimental data. Based on the modeled 3D structures, our calculated binding free energy for dopamine binding with DAT is also reasonably close to the experimentally measured binding affinity. Finally, a possible substrate-entry pathway, which involves the formation and breaking of the Arg85-Asp476 salt bridge, is proposed according to the results obtained from the modeling and MD simulation. The new structural and mechanistic insights obtained from this computational study should be valuable for design of future, further biochemical and pharmacological studies on the detailed structures and mechanisms of DAT and other homologous members of the neurotransmitter sodium symporters (NSS) family.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Center for Computational Sciences at the University of Kentucky for supercomputing time on Superdome (a shared-memory supercomputer, with four nodes for 256 processors).

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant No. R01 DA013930 to C.-G. Z.).

Editor: Ron Elber.

References

- 1.Uhl, R. G. 2003. Dopamine transporters: basic science and human variation of a key molecule for dopaminergic function, locomotion, and Parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 18:S71–S80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendelson, J. H., and N. K. Mello. 1996. Management of cocaine abuse and dependence. N. Engl. J. Med. 334:965–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh, S. 2000. Chemistry, design, and structure-activity relationship of cocaine antagonists. Chem. Rev. 100:925–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paula, S., M. R. Tabet, C. D. Farr, A. B. Norman, and W. J. Jr. Ball. 2004. Three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationship modeling of cocaine binding by a novel human monoclonal antibody. J. Med. Chem. 47:133–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, R., M. R. Tilley, H. Wei, F. Zhou, F.-M. Zhou, S. Ching, N. Quan, R. L. Stephens, E. R. Hill, T. Nottoli, D. D. Han, and H. H. Gu. 2006. Abolished cocaine reward in mice with a cocaine-insensitive dopamine transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:9333–9338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sparenborg, S., F. Vocci, and S. Zukin. 1997. Peripheral cocaine-blocking agents: new medications for cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 48:149–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorelick, D. A. 1997. Enhancing cocaine metabolism with butyrylcholinesterase as a treatment strategy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 48:159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Redish, A. D. 2004. Addiction as a computational process gone awry. Science. 306:1944–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao, D., H. Cho, W. Yang, Y. Pan, G.-F. Yang, H.-H. Tai, and C.-G. Zhan. 2006. Computational design of a human butyrylcholinesterase mutant for accelerating cocaine hydrolysis based on the transition-state simulation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 45:653–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao, D., and C.-G. Zhan. 2006. Modeling evolution of hydrogen bonding and stabilization of transition states in the process of cocaine hydrolysis catalyzed by human butyrylcholinesterase. Proteins. 62:99–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pan, Y., D. Gao, W. Yang, H. Cho, G.-F. Yang, H.-H. Tai, and C.-G. Zhan. 2005. Computational redesign of human butyrylcholinesterase for anti-cocaine medication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:16656–16661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhan, C.-G., and D. Gao. 2005. Catalytic mechanism and energy barriers for butyrylcholinesterase-catalyzed hydrolysis of cocaine. Biophys. J. 89:3863–3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao, D., and C.-G. Zhan. 2005. Modeling effects of oxyanion hole on the ester hydrolyses catalyzed by human cholinesterases. J. Phys. Chem. B. 109:23070–23076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaintdinov, R. R., T. D. Sotmikova, and M. G. Caron. 2002. Monoamine transporter pharmacology and mutant mice. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 23:367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torres, G. E., R. R. Gainetdinov, and M. G. Caron. 2003. Plasma membrane monoamine transporters: structure, regulation and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4:13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen, N., and M. E. A. Reith. 2003. Na+ and the substrate permeation pathway in dopamine transporters. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 479:213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berfield, L. J., C. L. Wang, and E. A. M. Reith. 1999. Which form of dopamine is the substrate for the human dopamine transporter: the cationic or the uncharged species? J. Biol. Chem. 274:4876–4882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitayama, S., S. Shimada, H. Xu, L. Markham, M. D. Donovan, and R. G. Uhl. 1992. Dopamine transporter site-directed mutations differentially alter substrate transport and cocaine binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:7782–7785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uhl, G. R., and Z. Lin. 2003. The top 20 dopamine transporter mutants: structure-function relationships and cocaine actions. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 479:71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loland, C. J., K. Norgaard-Nielsen, and U. Gether. 2003. Probing dopamine transporter structure and function by Zn2+-site engineering. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 479:187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu, H. H., and X. Wu. 2003. Cocaine affinity decreased by mutations of aromatic residue phenylalanine 105 in the transmembrane domain 2 of dopamine transporter. Mol. Pharmacol. 63:653–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen, N., J. Zhen, and M. E. A. Reith. 2004. Mutation of Trp84 and Asp313 of the dopamine transporter reveals similar mode of binding interaction for GBR12909 and benztropine as opposed to cocaine. J. Neurochem. 89:853–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sen, N., L. Shi, T. Beuming, H. Weinstein, and J. A. Javitch. 2005. A pincer-like configuration of TM2 in the human dopamine transporter is responsible for indirect effects on cocaine binding. Neuropharmacology. 49:780–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ukairo, O. T., C. D. Bondi, A. H. Neuwman, S. S. Kulkarni, A. P. Kozikowski, S. Pan, and C. K. Surratt. 2005. Recognition of benztropine by the dopamine transporter (DAT) differs from that of the classical dopamine uptake inhibitors cocaine, methylphenidate, and mazindol as a function of a DAT transmembrane 1 aspartic acid residue. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 314:575–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen, R., D. D. Han, and H. H. Gu. 2005. A triple mutation in the second transmembrane domain of mouse dopamine transporter markedly decreases sensitivity to cocaine and methylphenidate. J. Neurochem. 94:352–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaughan, R. A., D. S. Sakrikar, M. L. Parnas, S. Adkins, J. D. Foster, R. A. Duval, J. R. Lever, S. S. Kulkarni, and A. Hauck-Newman. 2007. Localization of cocaine analog [125I]RTI82 irreversible binding to transmembrane domain 6 of the dopamine transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 282:8915–8925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kniazeff, J., C. J. Loland, N. Goldberg, M. Quick, S. Das, H. H. Sitte, J. A. Javitch, and U. Gether. 2005. Intramolecular cross-linking in a bacterial homolog of mammalian SLC6 neurotransmitter transporters suggests an evolutionary conserved role of transmembrane segments 7 and 8. Neuropharmacology. 49:715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dar, D. E., T. G. Metzger, D. J. Vandenbergh, and G. R. Uhl. 2006. Dopamine uptake and cocaine binding mechanisms: the involvement of charged amino acids from transmembrane domains of the human dopamine transporter. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 538:43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boudker, O., R. M. Ryan, D. Yernool, K. Shimamoto, and E. Gouaux. 2007. Coupling substrate and ion binding to extracellular gate of a sodium-dependent aspartate transporter. Nature. 445:387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang, Y., M. J. Lemieux, J. Song, M. Auer, and D.-N. Wang. 2003. Structure and mechanism of the glycerol-3-phosphate transporter from Escherichia coli. Science. 301:616–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abramson, J., I. Smirnova, V. Kasho, G. Verner, H. R. Kaback, and S. Iwata. 2003. Structure and mechanism of the lactose permease of Escherichia coli. Science. 301:610–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yernool, D., O. Boudker, Y. Jin, and E. Gouaux. 2004. Structure of a glutamate transporter homologue from Pyrococcus horikoshii. Nature. 431:811–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunte, C., E. Screpant, M. Venturi, A. Rimon, E. Padan, and H. Michel. 2005. Structure of a Na+/H+ antiporter and insights into mechanism of action and regulation by pH. Nature. 435:1197–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamashita, A., S. K. Singh, T. Kawate, Y. Jin, and E. Gouaux. 2005. Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporters. Nature. 437:215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ravna, A. W., I. Sylte, and S. G. Dahl. 2003. Molecular model of the neural dopamine transporter. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 17:367–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ravna, A. W., I. Sylte, K. Kristiansen, and S. G. Dahl. 2006. Putative drug binding conformations of monoamine transporters. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14:666–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties, and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henikoff, S., and J. G. Henikoff. 1992. Amino-acid substitution matrices from protein blocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 89:10915–10919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Humphrey, W., A. Dalke, and K. Schulten. 1996. VMD—visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14:33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frisch, M. J., G. W. Trucks, H. B. Schlegel, G. E. Scuseria, M. A. Robb, J. R. Cheeseman, Jr., J. A. Montgomery, T. Vreven, K. N. Kudin, J. C. Burant, J. M. Millam, S. S. Iyengar, J. Tomasi, V. Barone, B. Mennucci, M. Cossi, G. Scalmani, N. Rega, G. A. Petersson, H. Nakatsuji, M. Hada, M. Ehara, K. Toyota, R. Fukuda, J. Hasegawa, M. Ishida, T. Nakajima, Y. Honda, O. Kitao, H. Nakai, M. Klene, X. Li, J. E. Knox, H. P. Hratchian, J. B. Cross, C. Adamo, J. Jaramillo, R. Gomperts, R. E. Stratmann, O. Yazyev, A. J. Austin, R. Cammi, C. Pomelli, J. W. Ochterski, P. Y. Ayala, K. Morokuma, G. A. Voth, P. Salvador, J. J. Dannenberg, V. G. Zakrzewski, S. Dapprich, A. D. Daniels, M. C. Strain, O. Farkas, D. K. Malick, A. D. Rabuck, K. Raghavachari, J. B. Foresman, J. V. Ortiz, Q. Cui, A. G. Baboul, S. Clifford, J. Cioslowski, B. B. Stefanov, G. Liu, A. Liashenko, P. Piskorz, I. Komaromi, R. L. Martin, D. J. Fox, T. Keith, M. A. Al-Laham, C. Y. Peng, A. Nanayakkara, M. Challacombe, P. M. W. Gill, B. Johnson, W. Chen, M. W. Wong, C. Gonzalez, and J. A. Pople. 2003. Gaussian 03, Rev. A.1. Gaussian, Pittsburgh, PA.

- 41.Zhan, C.-G., O. Norberto de Souza, R. Rittenhouse, and R. L. Ornstein. 1999. Determination of two structural forms of catalytic bridging ligand in zinc-phosphotriesterase by molecular dynamics simulation and quantum chemical calculation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121:7279–7282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koca, J., C.-G. Zhan, R. Rittenhouse, and R. L. Ornstein. 2001. Mobility of the active site bound paraoxon and sarin in zinc-phosphotriesterase by molecular dynamics simulation and quantum chemical calculation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123:817–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhan, C.-G., F. Zheng, and D. W. Landry. 2003. Fundamental reaction mechanism for cocaine hydrolysis in human butyrylcholinesterase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125:2462–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamza, A., H. Cho, H.-H. Tai, and C.-G. Zhan. 2005. Understanding human 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase binding with NAD+ and PGE2 by homology modeling, docking and molecular dynamics simulation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 109:4776–4782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang, X., W. Yan, D. Gao, M. Tong, H.-H. Tai, and C.-G. Zhan. 2006. Structural and functional characterization of human microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1) by computational modeling and site-directed mutagenesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14:3553–3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Case, D. A., T. A. Darden, T. E. Cheatham III, C. L. Simmerling, J. Wang, R. E. Duke, R. Luo, K. M. Merz, B. Wang, D. A. Pearlman, M. Crowley, S. Brozell, V. Tsui, H. Gohlke, J. Mongan, V. Hornak, G. Cui, P. Beroza, C. Schafmeister, J. W. Caldwell, W. S. Ross, and P. A. Kollman. 2004. AMBER 8. University of California, San Francisco.

- 47.Jorgensen, W. L., J. Chandrasekhar, J. D. Madura, and R. W. Impey. 1983. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morris, G. M., D. S. Goodsell, R. S. Halliday, R. Huey, W. E. Hart, R. K. Belew, and A. J. Olson. 1998. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and empirical binding free energy function. J. Comput. Chem. 19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuntz, I. D., D. T. Moustakas, and P. T. Lang. 2006. DOCK 5.4. University of California, San Francisco.

- 50.Solis, F. J., and R. J. B. Wets. 1981. Minimization by random search techniques. Math. Oper. Res. 6:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kollman, P. A., I. Massova, C. Reyes, B. Kuhn, S. Huo, L. Chong, M. Lee, T. Lee, Y. Duan, W. Wang, O. Donini, P. Cieplak, J. Srinivasan, D. A. Case, and T. E. I. I. I. Cheatham. 2000. Calculating structures and free energies of complex molecules: combining molecular mechanics and continuum models. Acc. Chem. Res. 33:889–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gilson, M. K., and B. Honig. 1988. Calculation of the total electrostatic energy of a macromolecular system: solvation energies, binding energies and conformational analysis. Proteins. 4:7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nicholls, A., and B. Honig. 1991. A rapid finite difference algorithm, utilizing successive over-relaxation to solve the Poisson-Boltzmann equation. J. Comput. Chem. 12:435–445. [Google Scholar]

- 54.McQuarrie, D. A. A. 1976. Statistical Mechanics. Harper & Row, New York.

- 55.Brooks, B. R., D. Janežič, and M. Karplus. 1995. Harmonic analysis of large systems. I. Methodology. J. Comput. Chem. 16:1522–1542. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berendsen, H. J. C., J. P. M. Postma, W. F. van Gunsteren, A. DiNola, and J. R. Haak. 1984. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morishita, T. 2000. Fluctuation formulas in molecular dynamics simulations with the weak coupling heat bath. J. Chem. Phys. 113:2976–2982. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Darden, T., D. York, and L. Pedersen. 1993. Particle mesh Ewald—an N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toukmaji, A., C. Sagui, J. Board, and T. Darden. 2000. Efficient particle-mesh Ewald based approach to fixed and induced dipolar interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 113:10913–10927. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ryckaert, J. P., G. Ciccotti, and H. J. C. Berendsen. 1977. Numerical integration of the Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Androutsellis-Theotokis, A., R. N. Goldberg, K. Ueda, T. Beppu, L. M. Beckman, L. Das, A. J. Javitch, and G. Rudnick. 2003. Characterization of a functional bacterial homologue of sodium-dependent neurotransmitter transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 278:12703–12709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hastrup, H., N. Sen, and A. J. Javitch. 2003. The human dopamine transporter forms a tetramer in the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 278:45045–45048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sitte, H. H., and M. Freissmuth. 2003. Oligomer formation by Na+-Cl− coupled neurotransmitter transporters. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 479:229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patargias, G., P. J. Bond, S. S. Deol, and M. S. Sansom. 2005. Molecular dynamics simulations of GlpF in a micelle versus in a bilayer: conformational dynamics of a membrane protein as a function of environment. J. Phys. Chem. B. 109:575–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bismuth, Y., M. P. Kavanaugh, and B. I. Kanner. 1997. Tyrosine 140 of the γ-aminobutyric acid transporter GAT-1 plays a critical role in neurotransmitter recognition. J. Biol. Chem. 272:16096–16102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen, J. G., A. Sachpatzids, and G. Rudnick. 1997. The third transmembrane domain of the serotonin transporter contains residues associated with substrate and cocaine binding. J. Biol. Chem. 272:28321–28327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ponce, J., B. Biton, J. Benavides, P. Avenet, and C. Aragon. 2000. Transmembrane domain III plays an important role in ion binding and permeation in the glycine transporter GLYT2. J. Biol. Chem. 275:13856–13862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rafi, B. S., Q. Cui, K. Song, X. Cheng, J. P. Tonge, and C. Simmering. 2006. Insight through molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area calculations into the binding affinity of triclosan and three analogues for Fab1, the E. coli enoyl reductase. J. Med. Chem. 49:4574–4580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]