Abstract

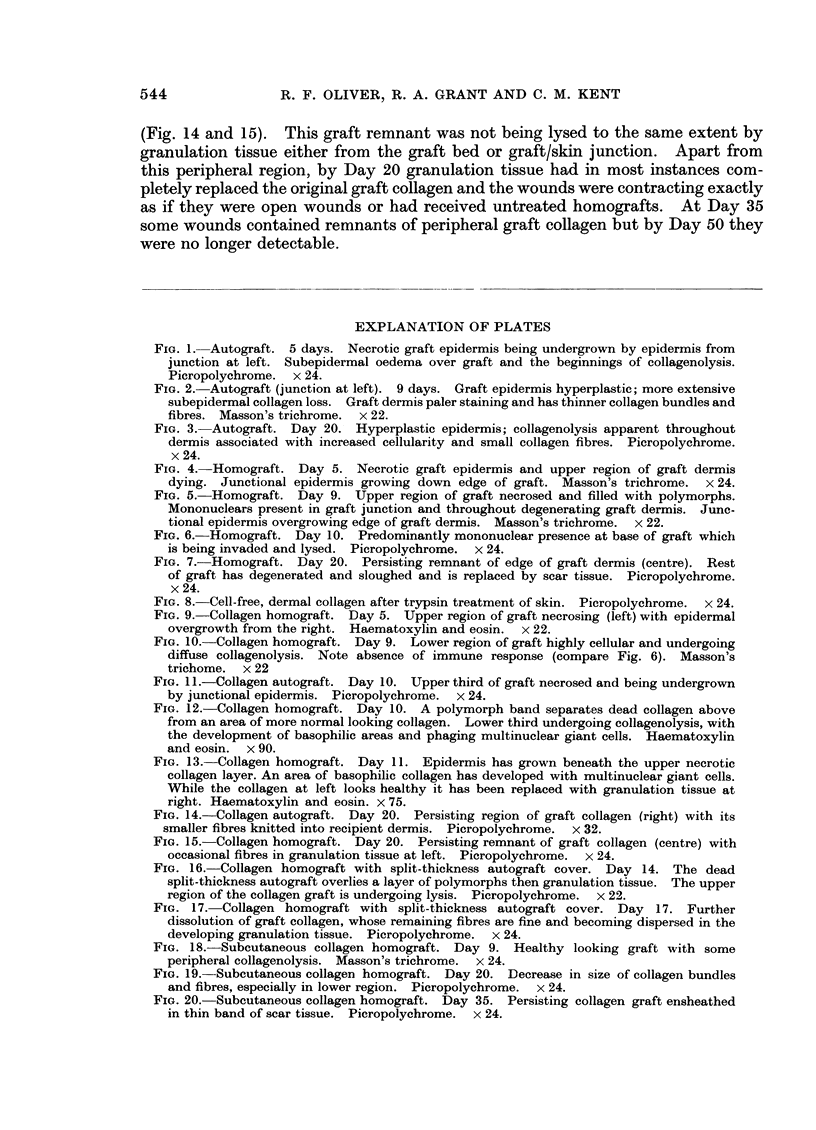

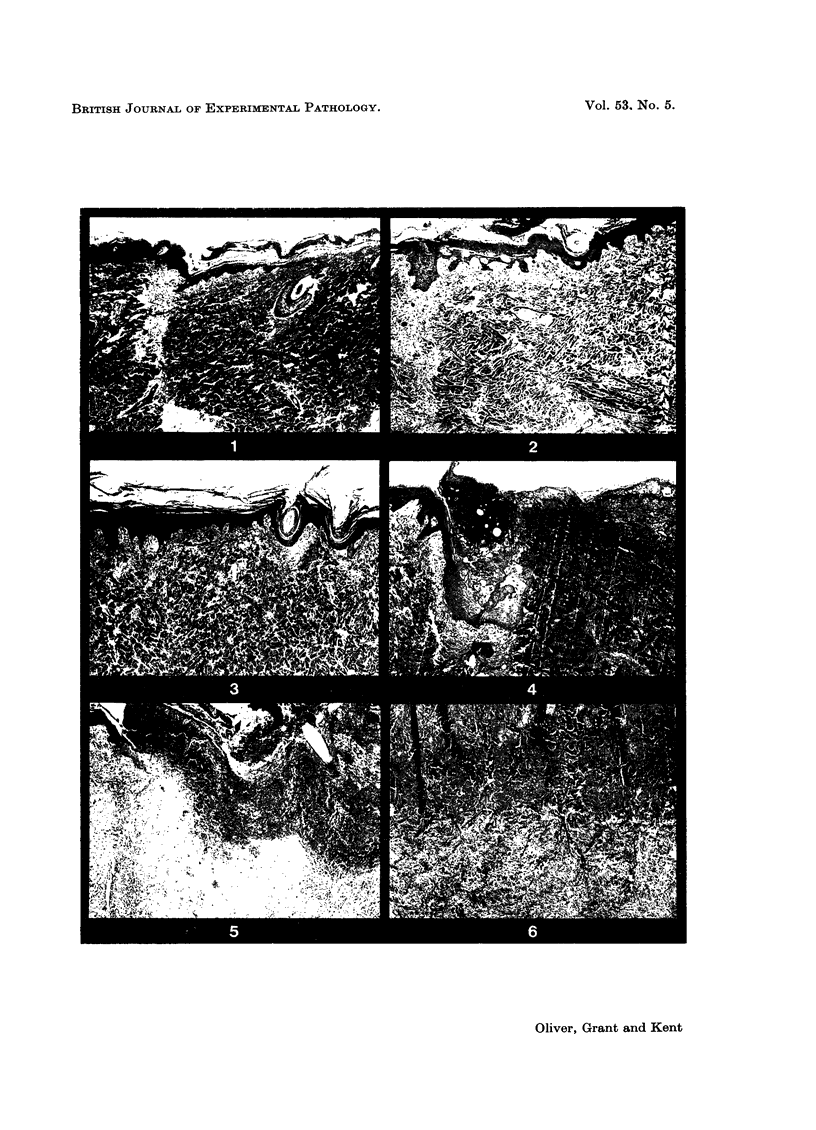

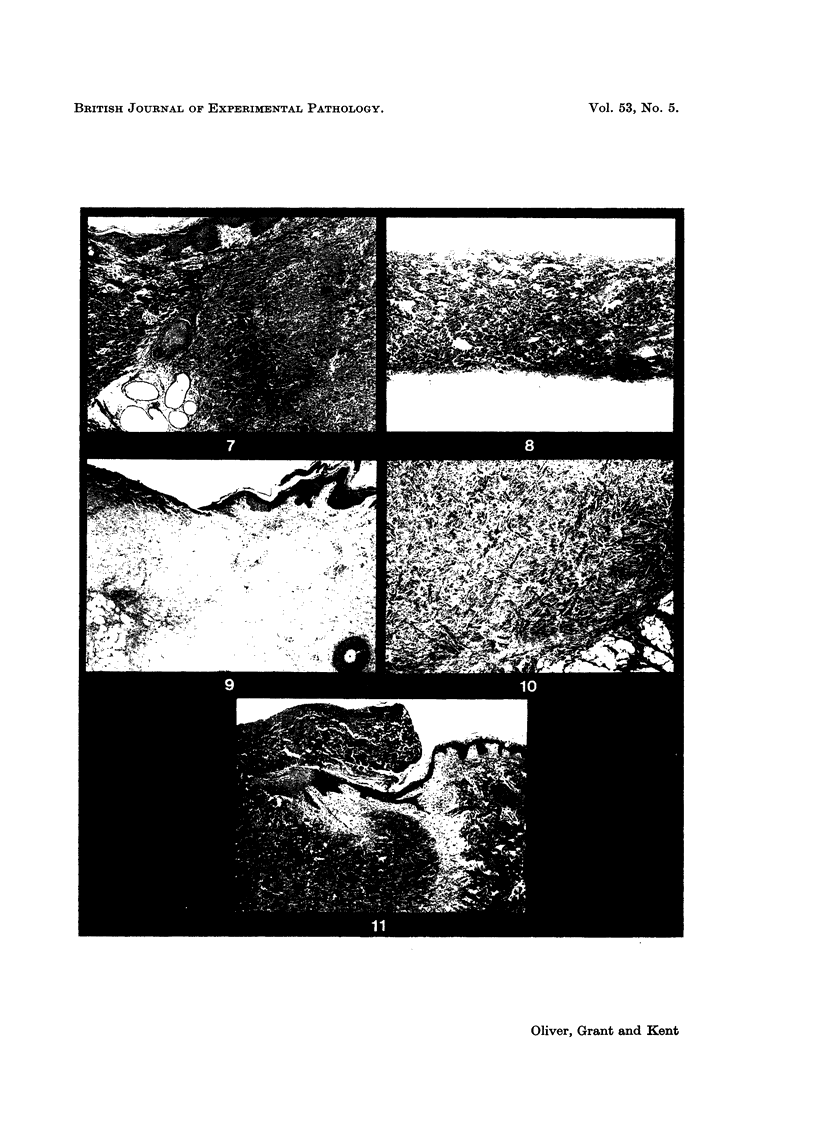

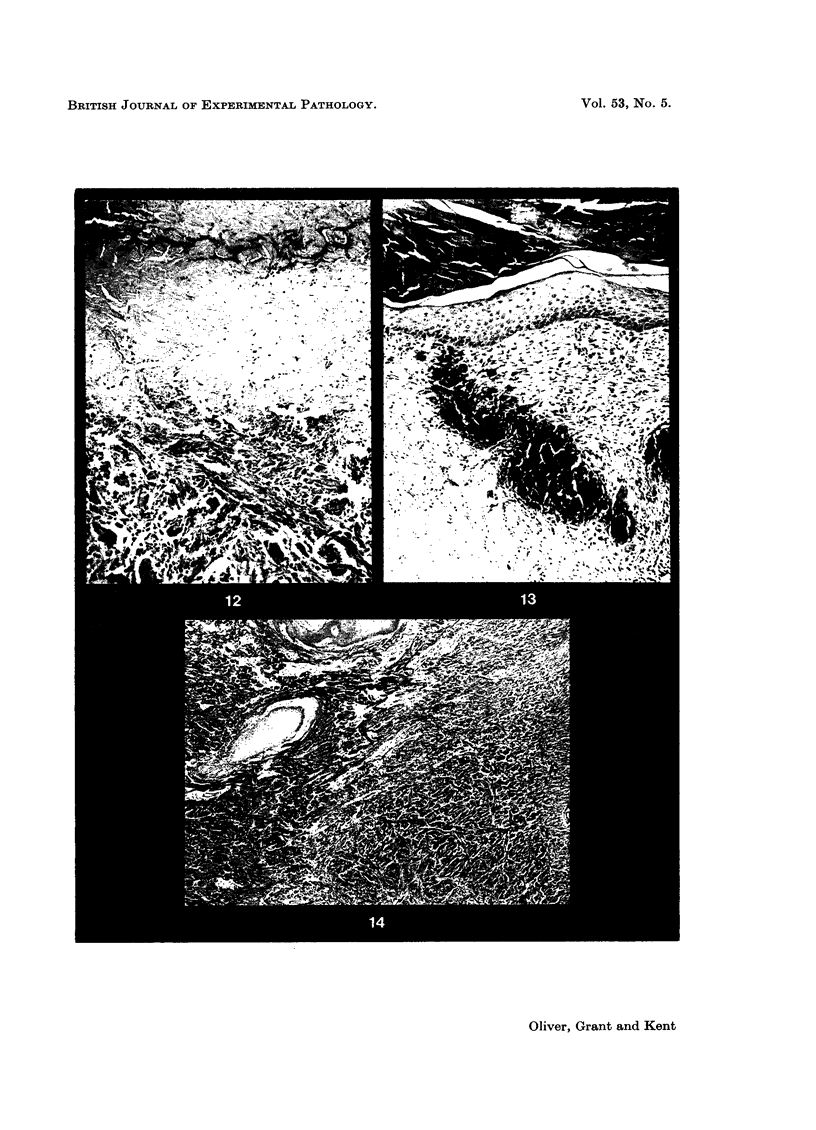

Pig dermal collagen was prepared by treating whole skin with a solution of crystalline trypsin at temperatures below 20°. The purified dermal collagen was implanted subcutaneously and into full thickness excised skin wounds in the pig. Biopsy specimens were removed after various periods of time and examined histologically. A parallel series of control experiments involving auto- and homografted skin were carried out under the same conditions, together with observations on full thickness excised wounds. Autografts and homografts behaved as previously described, the autografts appearing normal after 35 days while homografts were uniformly rejected and sloughed by Day 20 and contractions occurred as in open wounds. The dermal collagen grafts were invaded and colonized by host fibroblasts and other cells and became at least in part revascularized and re-epithelialized. The implanted collagen was progressively lysed and replaced by granulation tissue. Remnants of collagen persisted in peripheral parts of the graft up to Day 35 but had disappeared by Day 50. Dermal collagen implants covered with split thickness auto- and homografts suffered the same fate as the dermal collagen grafts. Dermal collagen implanted subcutaneously into adipose tissue achieved in some instances a state of permanence, the collagen bundles retaining their original form and containing fibroblasts and capillaries.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abbenhaus J. I., MacMahon R. A., Rosenkrantz J. G., Paton B. C. Collagen sheets as a dressing for large excised areas. Surg Forum. 1965;16:477–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BILLINGHAM R. E., REYNOLDS J. Transplantation studies on sheets of pure epidermal epithelium and on epidermal cell suspensions. Br J Plast Surg. 1952 Apr;5(1):25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(52)80004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRENNER S., HORNE R. W. A negative staining method for high resolution electron microscopy of viruses. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1959 Jul;34:103–110. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(59)90237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN R. W., POSTLETHWAIT R. W. Ascorbic acid in the biosynthesis and maintenance of collagen. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1961 Jun;112:667–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUKES C. D., BLOCKER T. G., Jr Studies on the survival of skin homografts. I. Prolongation of life of full-thickness grafts by the action of streptokinase-streptodornase. Ann Surg. 1952 Dec;136(6):999–1006. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195212000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen A. Z., Bauer E. A., Jeffrey J. J. Animal and human collagenases. J Invest Dermatol. 1970 Dec;55(6):359–373. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12260483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen A. Z., Jeffrey J. J., Gross J. Human skin collagenase. Isolation and mechanism of attack on the collagen molecule. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1968 Mar 25;151(3):637–645. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(68)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GILLMAN T., HATHORN M., PENN J. Is skin homografting necessary? A re-examination of the rationale for auto- or homo-grafting of cutaneous injuries and a preliminary report on the action of plastic dressings. Plast Reconstr Surg (1946) 1956 Oct;18(4):260–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GROSS J., LAPIERE C. M. Collagenolytic activity in amphibian tissues: a tissue culture assay. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1962 Jun 15;48:1014–1022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.48.6.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant R. A., Cox R. W., Kent C. M. The effects of irradiation with high energy electrons on the structure and reactivity of native and cross-linked collagen fibres. J Cell Sci. 1970 Sep;7(2):387–405. doi: 10.1242/jcs.7.2.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOUCK J. C., JACOB R. A., DEANGELO L., VICKERS K. Dermal chemistry of local necrotic ulceration. Surgery. 1962 Mar;51:382–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw J. R., Miller E. R. Histology of healing split-thickness, full-thickness autogenous skin grafts and donor sites. Arch Surg. 1965 Oct;91(4):658–670. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1965.01320160112027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang A. H., Gross J. Amino acid sequence of cyanogen bromide peptides from the amino-terminal region of chick skicollagen. Biochemistry. 1970 Feb 17;9(4):796–804. doi: 10.1021/bi00806a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Tamayo R. Collagen resorption in carrageenin granulomas. II. Ultrastructure of collagen resorption. Lab Invest. 1970 Feb;22(2):142–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROTHBARD S., WATSON R. F. Antigenicity of rat collagen; reverse anaphylaxis induced in rats by anti-rat collagen serum. J Exp Med. 1956 Jan 1;103(1):57–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.103.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulitzeanu D. Antigenic components of rat connective tissue. Br J Exp Pathol. 1965 Oct;46(5):481–488. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D. G. Elevated bone collagenolytic activity and hyperplasia of parafollicular light cells of the thyroid gland in parathormone-treated grey-lethal mice. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1966;72(1):100–124. doi: 10.1007/BF00336900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]