Abstract

Pulmonary involvement is common in sarcoidosis, an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder that is characterized by non-caseating granulomas in tissue. Sarcoid patients with advanced pulmonary disease, especially end-stage pulmonary fibrosis, risk developing pulmonary hypertension (World Health Organization group III pulmonary hypertension secondary to hypoxic lung disease). Increased levels of endothelin (ET)-1 in plasma and bronchoalveolar lavage of some sarcoid patients suggest that ET-1 may be driving pulmonary fibrosis and sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension. Although a relationship between raised levels of ET-1 and clinical phenotype is yet to be identified, early evidence from studies of ET-1 blockade with drugs such as bosentan is encouraging. Such therapy possibly could be combined with standard anti-inflammatory agents to improve outcome.

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease of unknown aetiology that is characterized by the presence of non-caseating granulomas in tissue. Although many patients experience disease resolution, in about 25% of cases the disease has a progressive, chronic course [1]. Because the cause of sarcoidosis remains unknown, diagnosis is established when clinical and radiographic findings are supported by histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas in biopsied tissue. Importantly, because there are several conditions that may involve the development of noncaseating granulomatous lesions, accurate diagnosis requires exclusion of these causes of granulomatous disease (which can be a confounding factor for diagnosis) and the presence of noncaseating granulomatous in at least two organs. Importantly, it is almost impossible to be sure that the condition is in fact sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis is a classic multisystem disease, which can affect the heart, skin (as in lupus pernio), liver, eyes, lymph nodes, salivary glands and, in particular, the respiratory tissues. Pulmonary involvement is common in sarcoid patients and may contribute to deteriorating lung function and the eventual development of end-stage pulmonary fibrosis [2].

The chest roentgenogram of patients with sarcoidosis includes those with interstitial lung disease with adenopathy (stage II), interstitial lung disease (stage III), or fibrosis (stage IV). Patients with advanced pulmonary disease, with vital capacities of less than 60% predicted, or with extensive interstitial lung disease or fibrosis (stages II, III and IV) are prone to pulmonary hypertension (PH) and cor pulmonale. This review focuses on sarcoid patients with persistent chronic pulmonary disease. It explores the role of the endothelin system in the pathophysiology of pulmonary fibrosis and discusses the therapeutic potential of endothelin blockade.

Pathophysiology of sarcoidosis: current opinion

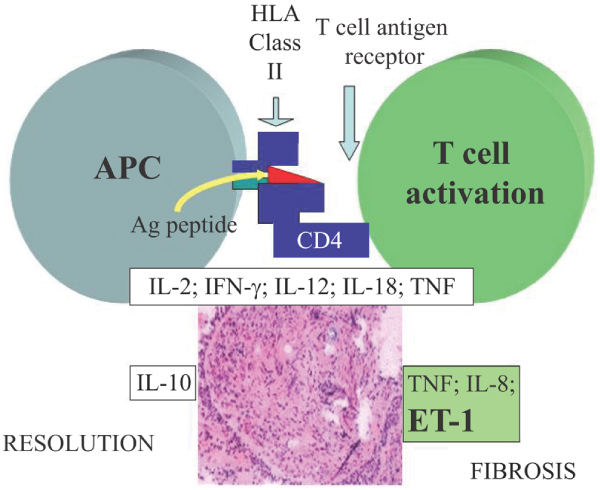

The precise cause of sarcoidosis is yet to be elucidated. However, current opinion holds that the disease is triggered by exposure to an antigen, such as Propionibacterium acnes, or a number of antigens [3,4]. Although the precise identity of the antigen(s) remains elusive, the subsequent activation of a complicated cascade of cytokines is unequivocal. Antigenic exposure leads to T-cell activation and an increase in CD4+ helper T cells. A cascade of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-2, interferon-γ, IL-12, IL-18 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, is released, which leads to inflammation and eventually fibrosis [5] (Figure 1). In a series of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) studies conducted in the 1970s, it was shown that in patients with sarcoidosis there is an influx of CD4+ cells [6], suggesting that elimination of these cells would be sufficient to cure sarcoidosis. However, cyclosporine is not effective in sarcoidosis, and whereas the influx of CD4+ cells is among the initiating events in sarcoidosis, these cells are not important in longstanding, persistent, fibrotic forms of the disease.

Figure 1.

Inflammatory reaction of sarcoidosis. The initial response of sarcoidosis is mediated by CD4 and APCs which release a large number of cytokines. Over time, the granuloma can either resolve or go on to form fibrosis. Fibrosis is associated with TNF, IL-8 and ET-1. Ag, antigen; APC, antigen-presenting cell; ET, endothelin; HLA, human leucocyte antigen; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumour necrosis factor. Reproduced with permission from Baughman et al.: Tumour necrosis factor in sarcoidosis and its potential for targeted therapy. Biodrugs 2003, 17(6):425–431. © Wolters Kluwer Health [5].

One of the confounding aspects of sarcoidosis is that in many people the condition will resolve spontaneously and in many cases the initiation of treatment influences the likelihood of long-term treatment being required. As a consequence, approximately half of sarcoidosis patients never need therapy and about one-quarter require years of therapy. The ACCESS (A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis) study [1] evaluated a subset of patients seen within 6 months of diagnosis and 2 years later. In all, 205 sarcoidosis patients were analyzed. Use of systemic therapy within the first 6 months after diagnosis appeared to be strongly associated with continued use of therapy 2 years later. Approximately 25% of all patients studied developed chronic persistent sarcoidosis. In these patients, there is evidence that IL-8 and TNF-α are among the most important mediators of inflammation and fibrosis [5].

TNF-α is a potent cytokine that has been implicated in many immune-mediated disorders. One study, in which patients with sarcoidosis were treated for 2 years with methotrexate, a nonspecific inhibitor of TNF-α, showed that 60% to 80% of patients with pulmonary disease responded to therapy [7]. Correspondingly high response rates of between 60% and 70% were observed in patients with brain, eye and skin involvement. Evidence for the efficacy of methotrexate in sarcoidosis was also demonstrated in a subsequent randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial in patients with acute pulmonary disease [8]. In this study patients received either methotrexate or placebo in addition to standard corticosteroid therapy (prednisone), which also blocks cellular release of TNF-α. Over a 12-month period, patients in the methotrexate arm of the study required significantly lower doses of steroids than did those who were randomly assigned to placebo. These steroid-sparing effects of methotrexate were evident after the first 6 months when placebo-treated patients required twice as much steroid therapy to prevent relapse as those given methotrexate.

The role of endothelin in sarcoidosis and rationale for endothelin blockade

In scleroderma the role of endothelin (ET)-1 in pulmonary fibrosis and associated complications such as PH is well documented [9-11]; in contrast, less is known about the importance of ET-1 in sarcoidosis. Sofia and coworkers [12] published data showing that ET-1 was elevated in the urine of patients with sarcoidosis but not in those with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). However, in their study no difference was observed in plasma ET-1 levels between sarcoid patients, IPF patients, and healthy control individuals. This finding is at variance with the large body of evidence showing that IPF patients have significantly raised plasma ET-1 levels [13,14], and insufficient clinical correlative information was available.

More recently, Letizia and colleagues [15] showed that plasma ET-1 levels were raised in patients with sarcoidosis compared with those in healthy control individuals. Sarcoid patients also had raised levels of serum angiotensin-converting enzyme, a finding consistent with those of many other studies [16,17], and a raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Interestingly, in patients who went into remission following successful corticosteroid therapy, ET-1 levels decreased and other parameters of disease activity normalized.

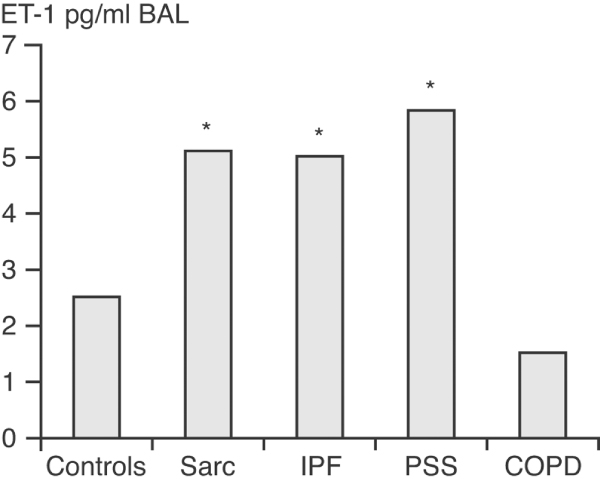

Further evidence to suggest that ET-1 may be involved in sarcoidosis came from assessments of ET-1 levels in BAL specimens. BAL is a standard method for assessing interstitial lung disease and it is a useful sampling procedure for obtaining direct evidence of alveolar inflammation. Reichenberger and colleagues [18] examined ET-1 levels in BAL specimens from patients with various lung conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, IPF, scleroderma and sarcoidosis. As expected, elevated ET-1 levels were observed in patients with IPF and scleroderma but not in those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or healthy control individuals (Figure 2). Comparably high ET-1 levels to those seen in scleroderma and IPF patients were also observed in the patients with sarcoidosis.

Figure 2.

Endothelin-1 levels in BAL fluid from patients with interstitial lung disease, COPD, and control individuals. Levels of endothelin (ET)-1 in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid specimens taken from patients with sarcoidosis (Sarc; n = 8), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF; n = 9), fibrosing alveolitis in systemic sclerosis (PSS; n = 13) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; n = 8) were examined. A heterogeneous group of 19 patients served as control individuals. *Significantly higher than controls of COPD [18].

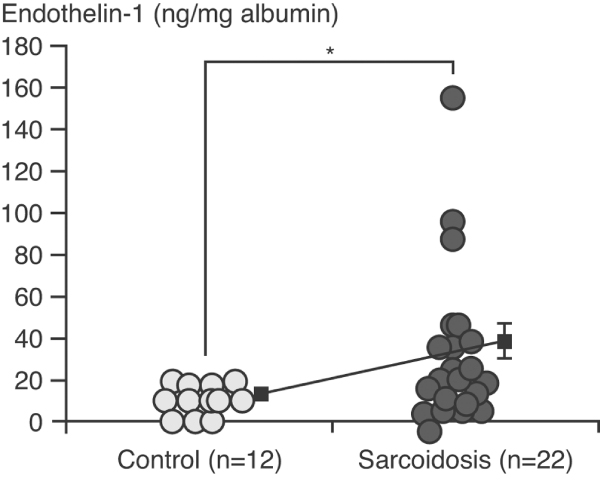

Some of the best data on the likely importance of ET-1 in sarcoidosis have come from a recent study in which ET-1 levels in BAL fluid were compared between 22 nonsmoking sarcoid patients and 12 nonsmoking healthy control individuals [19]. Although the study did not document clinical outcome in these patients, elevated ET-1 levels were observed in approximately 25% (Figure 3). ET-1 levels also correlated with the number of macrophages retrieved in the BAL specimens (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Endothelin-1 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) fluid in sarcoid patients and healthy controls. Endothelin-1 levels were measured by enzyme immunoassay and were corrected by albumin concentration in recovered BAL fluid. The data represent values ± standard error of the mean in both groups. *P < 0.05. Reproduced with permission from Terashita et al. Respirology 2006. © Blackwell Publishing [19].

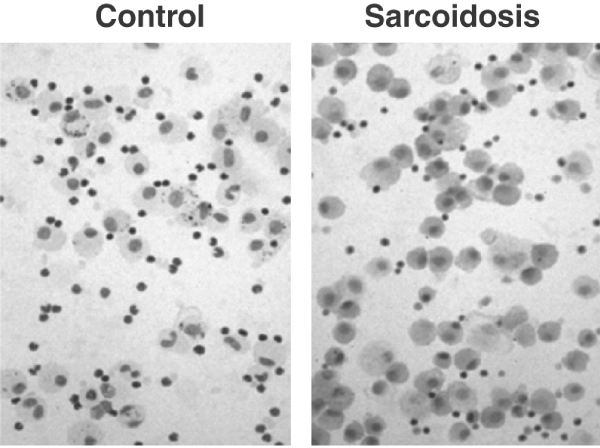

Figure 4.

Histological evidence of endothelin-1 in macrophages from sarcoid patients. Immunocytochemical detection of endothelin-1 in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cells from patients with sarcoidosis and control individuals, using rabbit monoclonal antibody to human endothelin-1. Cytoplasm of BAL cells from sarcoidosis was strongly stained relative to controls. Immunostaining also demonstrated that most of the immunopositive cells were macrophages. Reproduced with permission from Terashita et al. Respirology 2006. © Blackwell Publishing [19].

Earlier work demonstrated that alveolar macrophages harvested in BAL fluid from patients with IPF and sarcoidosis were a primary source of ET-1, and that the supernatant from these alveolar macrophages stimulated the growth of fibroblasts [20]. In their study, Terashita and coworkers [19] were also able to demonstrate that BAL supernatants from the sarcoid patients led to increased fibroblast proliferation. Moreover, in the presence of an ET-1 inhibitor, fibroblast proliferation was blocked.

Thus, although data are currently limited, there is growing evidence to suggest that levels of ET-1 in urine, plasma and BAL fluid are increased in some, albeit not all, patients with sarcoidosis. This raises intriguing questions about the clinical significance of ET-1 in sarcoidosis and whether blockade of ET-1 is a rational approach to therapy. Two case studies provide some interesting insight into these questions.

Case 1: unexplained dyspnoea in sarcoidosis

Case 1 is that of a 45-year-old Caucasian female patient who presented with severe dyspnoea 8 months after first seeing her pulmonologist. The patient had initially developed a painful rash (hives) on her legs and abdomen, which resolved with steroids but recurred when therapy was withdrawn. A further course of steroid therapy proved effective but the patient went on to develop dyspnoea on exertion that progressively worsened. Three months before referral for a second opinion, the patient was hospitalized for severe dyspnoea.

On admission to hospital the chest radiograph showed adenopathy and a soft pulmonary infiltrate, classified as stage II sarcoid with lymph nodes and infiltrates but no fibrosis. Granulomas were found on mediastinoscopy and sarcoidosis was diagnosed. Aggressive therapy with 60 mg/day prednisone improved symptoms, but any reduction in dosage led to an exacerbation of dyspnoea. Eventually, prednisone was tapered to 25 mg/day. By this stage the patient no longer had a skin rash, the lungs were clear, and the chest radiography showed minimal infiltrates and a marked improvement from the pre-steroid film. Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) revealed a forced expiratory volume in 1 s of 2.04 l and forced vital capacity of 2.52 l (84% of predicted), but dyspnoea persisted.

Despite normal PFTs and no evidence of pulmonary fibrosis, severe impairment was observed on the 6-min walk test (6 MWT), with the patient only managing to walk 300 m on room air. Heart rate increased from 116 beats/min at baseline to 140 beats/min after the 6 MWT, arterial oxygen saturation dropped to 77%, and the Borg dyspnoea index increased from 3 to 10. PH with a right to left shunt was suspected and subsequently confirmed by catheterization; right atrium pressure was normal (10 mmHg), pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) was 79/39 mmHg and pulmonary artery occlusion pressure was 41 mmHg, but left ventricular end-diastolic pressure was 12 mmHg.

The eventual diagnosis of PH in this patient with previously unexplained, persistent dyspnoea is in accordance with growing evidence suggesting that PH secondary to sarcoidosis is relatively common. Indeed, among end-stage sarcoid patients awaiting lung transplantation, PH is documented in approximately 75% of cases, in which it is predictive of increased mortality [21,22]. PH has also been documented in approximately 50% of patients with advancing pulmonary disease associated with sarcoidosis [23]. The mechanism of PH in sarcoidosis appears to be multifactorial. Among the possible causes are direct compression of the pulmonary arteries, fibrotic destruction of the lung vasculature, hypoxia and a pulmonary vasculopathy [24-26]. Direct vessel involvement has been documented in some cases [26]. The PH can respond to vasodilator drugs such as epoprostenol [27], which emphasizes the importance of vascular disease in PH associated with sarcoidosis.

PH in sarcoidosis can also be due to vasculitis. Extensive vasculitis from the granulomatous involvement of sarcoidosis usually leads to a presentation referred to as 'necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis' [28]. Whether this condition is an extreme form of sarcoidosis or is a distinct entity is controversial [29].

Case 2: worsening dyspnoea in steroid-refractory sarcoidosis

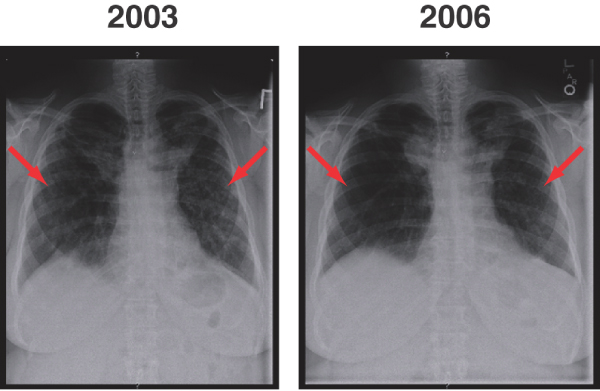

Case 2 is that of a Caucasian female patient with biopsy-confirmed sarcoidosis who experienced worsening dyspnoea despite a 12-month course of prednisone. Over the 12-month period, chest radiography revealed a worsening picture with increased fibrotic changes in the upper lobes of the lung. Cardiac catheterization revealed a PAP of 60 mmHg, elevated pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) of 253 dynes and a pulmonary artery occlusion pressure of 8 mmHg, in conjunction with normal left end-diastolic pressure. Treatment with the dual endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) bosentan and the specific anti-TNF-α agent infliximab was initiated [30]. Over a 3-year treatment period, PAP and PVR dropped to the near normal range (Table 1). Commensurate improvements were observed on chest radiography (Figure 5).

Table 1.

Sarcoidosis before and after treatment: cardiac catheterization data

| January | March | September | |

| 2002 | 2003 | 2006 | |

| PAP systolic (mmHg) | 60 | 42 | 37 |

| PAP mean (mmHg) | 36.7 | 24 | 19 |

| CO (l/min) | 7.8 | 10.2 | 6.9 |

| PVR (dyn·s/cm5) | 253 | 125 | 151 |

| Bosentan dose (mg) | 0 | 125 | 125 |

| twice daily | twice daily | ||

Shown are pretreatment and post-treatment cardiac catheterization data in a patient with steroid-refractory sarcoidosis who was treated with bosentan and infliximab. CO, cardiac output; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance.

Figure 5.

Sarcoidosis before and after treatment: chest radiography. Shown are pretreatment (2003) and post-treatment (2006) chest radiographs in a patient with steroid-refractory sarcoidosis treated with bosentan and infliximab. Arrows indicate areas of infiltrates within both lung fields. The infiltrates have improved between 2003 and 2006 with treatment for the patient's sarcoidosis.

Preliminary clinical data with endothelin receptor antagonists in sarcoidosis

As case 2 illustrates, ERAs such as bosentan appear to have clinical benefit in sarcoidosis-associated PH. Although data remain limited, other case studies support this encouraging finding. Data from our centre on a small cohort of sarcoid patients with persistent dyspnoea and elevated PAP indicative of PH have shown that treatment with bosentan reduces PAP [31] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Improvement in PAP in patients with sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension following bosentan treatment

| Patient | Initial mean PAP (mmHg) | Follow-up mean PAP (mmHg) | Pulmonary hypertension therapy | Other sarcoidosis medications |

| 1 | 73 | 41 | Epoprostenol | Prednisone, methotrexate, azathioprine, infliximab |

| 2a | 63 | 45 | Bosentan | Prednisone |

| 3a | 61 | ND | Bosentan, epoprostenol | Prednisone, azathioprine |

| 4 | 53 | 23 | Amlodipine | Prednisone, methotrexate |

| 5 | 50 | ND | Bosentan | Prednisone, methotrexate |

| 6 | 38 | 36 | Bosentan | Prednisone, methotrexate, azathioprine |

| 7 | 36 | 24 | Bosentan | Prednisone, methotrexate, infliximab |

Shown are data demonstrating improvement in pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) following addition of bosentan to standard anti-inflammatory therapy in a small cohort of patients with sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension. aPatient died. ND, not determined.

The case of a 54-year-old male patient with sarcoidosis-associated PH successfully treated with bosentan has also been described [32]. This patient presented with stage II pulmonary disease, exhibiting limited lung capacity and low diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide but no evidence of pulmonary fibrosis. Treatment with prednisone proved to be of only limited clinical benefit, because the patient experienced recurrence of symptoms when the dosage was reduced to 20 mg/day. However, within 6 months of additional therapy with bosentan, there was a marked reduction in PAP and an even greater reduction in PVR. The mean PAP dropped from 55 mmHg before institution of bosentan to 23 at follow up, whereas PVR dropped from 571 to 83 mmHg at follow up. Additionally, during this period concomitant steroid therapy was tapered to prednisone 7.5 mg/day.

Improvement in 6 MWT following treatment with bosentan was reported in the case of a 72-year-old black male patient with secondary PH due to sarcoidosis [33]. Before treatment, the patient had a forced vital capacity of 40% predicted, a diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide of 46% predicted, a PAP of 78 mmHg and a 6 MWT distance of only 30 m. Following treatment with bosentan 125 mg twice daily, nifedipine, and prednisone, 6 MWT distance increased to 320 m. Improvement in cardiac function was also observed with a change in New York Heart Association functional class from class IV to II after treatment.

Sarcoidosis patients are of course susceptible to PH for other reasons. Cardiac sarcoidosis can lead to left heart failure and 'passive PH' [34]. In addition, although none of the patients included in our case series [31] exhibited evidence of significant liver disease, liver involvement does occur and may result in liver failure and portal hypertension, with subsequent portopulmonary hypertension [35]. There are also several reports in the literature of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease [36,37] associated with sarcoidosis. Once again, although our patients had radiological evidence of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, such as Kerley B lines or septal lines and ground glass infiltrates [38], it is critical to diagnose pulmonary veno-occlusive disease correctly in these patients because they may develop potentially fatal pulmonary oedema if they are given vasodilator therapy, particularly epoprostenol [39]. Finally, sarcoidosis patients may have profound hypoxaemia leading to PH, although in our patient series the degree of PH and the fact that pressures remained elevated despite oxygen therapy are consistent with hypoxia not being a major contributing factor.

It could therefore be concluded that PH-associated sarcoidosis fits into all five classes of the accepted World Health Organization classification of PH [40]. Although PH associated with sarcoidosis is officially grouped in World Health Organization class 5, this is controversial and there clearly are cases of PH associated with sarcoidosis that fit more appropriately into other groups of this classification.

Conclusion

An expanding body of evidence suggests that PH is a relatively common complication of sarcoidosis, not only in patients with end-stage pulmonary fibrosis (stage IV), for whom it is predictive of increased mortality, but also in those with earlier stage pulmonary disease. There is also evidence that ET-1 levels are elevated in urine, plasma and BAL specimens from sarcoid patients, albeit not in all. A relationship between elevated ET-1 levels in body fluids, such as plasma or BAL fluid, and clinical phenotype has yet to be determined. However, outcomes from a small number of case studies point to potential clinical benefit from dual endothelin receptor antagonism with bosentan in sarcoidosis-associated PH. This suggests that ET-1 may be an important driver of pulmonary fibrosis and associated complications such as PH. Future studies are planned to measure plasma and BAL fluid levels of ET-1 in sarcoidosis patients, with and without PH.

Sarcoidosis is an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder, with a wide range of clinical outcomes. Although the majority of patients do well with no or minimal therapy, some patients can develop chronic disease. Use of immunosuppressive drugs can control this disease. In elucidating the role of ET-1 in sarcoidosis, it would be worthwhile to study further the effects of immunomodulatory drugs on levels of ET-1. Potentially suppressing the inflammatory response could have a corresponding effect on ET-1 levels and on effects mediated by ET-1. In one of the few studies in which ET-1 levels were measured before and after corticosteroid therapy, plasma ET-1 levels were seen to decrease in patients who went into remission [14]. Additional studies are needed to confirm the effects of immunomodulatory therapy on ET-1 levels as well as to substantiate the extent to which augmenting standard anti-inflammatory therapy with ERAs provides additional clinical benefit in sarcoidosis-associated PH.

Abbreviations

BAL = bronchoalveolar lavage; ERA = endothelin receptor antagonist; ET = endothelin; IL = interleukin; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; 6 MWT = 6-min walk test; PAP = pulmonary artery pressure; PFT = pulmonary function test; PH = pulmonary hypertension; PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance; TNF = tumour necrosis factor.

Competing interests

The author has received speaker fees and reimbursement for travel expenses from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge medical writing support funded by an educational grant from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

This article is part of Arthritis Research & Therapy Volume 9 Supplement 2: Advances in systemic sclerosis and related fibrotic and vascular conditions, and is based on presentations made at a symposium entitled Advances in systemic sclerosis and connective tissue disease, sponsored by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd, held in Athens, Greece in April 2006. The full contents of the supplement are available online at http://arthritis-research.com/supplements/9/S2. This supplement has been supported by an educational grant from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

References

- Baughman RP, Judson MA, Teirstein A, Yeager H, Rossman M, Knatterud GL, Thompson B. Presenting characteristics as predictors of duration of treatment in sarcoidosis. QJM. 2006;99:307–315. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bihl MP, Laule-Kilian K, Bubendorf L, Rutherford RM, Baty F, Kehren J, Eryuksel E, Staedtler F, Yang JQ, Goulet S, et al. Progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis: a fibroproliferative process potentially triggered by EGR-1 and IL-6. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2006;23:38–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eishi Y, Suga M, Ishige I, Kobayashi D, Yamada T, Takemura T, Takizawa T, Koike M, Kudoh S, Costabel U, et al. Quantitative analysis of mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA in lymph nodes of Japanese and European patients with sarcoidosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:198–204. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.1.198-204.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman RP, Lower EE, du Bois RM. Sarcoidosis. Lancet. 2003;361:1111–1118. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12888-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman RP, Iannuzzi M. Tumour necrosis factor in sarcoidosis and its potential for targeted therapy. BioDrugs. 2003;17:425–431. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200317060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunninghake GW, Fulmer JD, Young RC, Jr, Gadek JE, Crystal RG. Localization of the immune response in sarcoidosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120:49–57. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.120.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lower EE, Baughman RP. Prolonged use of MTX for sarcoidosis. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:846–851. doi: 10.1001/archinte.155.8.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman RP, Winget DB, Lower EE. Methotrexate is steroid sparing in acute sarcoidosis: results of a double blind, randomized trial. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2000;17:60–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vancheeswaran R, Magoulas T, Efrat G, Wheeler-Jones C, Olsen I, Penny R, Black CM. Circulating endothelin-1 levels in systemic sclerosis subsets: a marker of fibrosis or vascular dysfunction? J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1838–1844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno K, Hirata Y, Emori T, Ohta K, Shichiri M, Shinohara S, Chida Y, Tomura S, Marumo F. Endothelin and Raynaud's phenomenon. Am J Med. 1991;90:130–132. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90519-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biondi ML, Marasini B, Bassani C, Agastoni A. Increased plasma endothelin levels in patients with Raynaud's phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1139–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofia M, Mormile M, Faraone S, Alifano M, Carratu P, Carratu L. Endothelin-1 excretion in urine in active pulmonary sarcoidosis and in other interstitial lung diseases. Sarcoidosis. 1995;12:118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uguccioni M, Pulsatelli L, Grigolo B, Facchini A, Fasano L, Cinti C, Fabbri M, Gasbarrini G, Meliconi R. Endothelin-1 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:330–334. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.4.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaid A, Michel RP, Stewart DJ, Sheppard M, Corrin B, Hamid Q. Expression of endothelin-1 in lungs of patients with cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Lancet. 1993;341:1550–1554. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90694-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letizia C, Danese A, Reale MG, Caliumi C, Delfini E, Subioli S, Cerci S, D'Erasmo E. Plasma levels of endothelin-1 increase in patients with sarcoidosis and fall after disease remission. Panminerva Med. 2001;43:257–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRemee RA. Sarcoidosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:177–181. doi: 10.4065/70.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietinalho A, Ohmichi M, Lofroos AB, Hiraga Y, Selroos O. The prognosis of pulmonary sarcoidosis in Finland and Hokkaido, Japan. A comparative five-year study of biopsy-proven cases. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2000;17:158–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenberger F, Schauer J, Kellner K, Sack U, Stiehl P, Winkler J. Different expression of endothelin in the bronchoalveolar lavage in patients with pulmonary diseases. Lung. 2001;179:163–174. doi: 10.1007/s004080000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashita K, Kato S, Sata M, Inoue S, Nakamura H, Tomoike H. Increased endothelin-1 levels of BAL fluid in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Respirology. 2006;11:145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar I, Fireman E, Topilsky M, Grief J, Schwarz Y, Kivity S, Ben-Efraim S, Spirer Z. Effect of endothelin-1 on alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and on alveolar fibroblasts proliferation in interstitial lung diseases. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1999;21:759–775. doi: 10.1016/S0192-0561(99)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcasoy SM, Christie JD, Pochettino A, Rosengard BR, Blumenthal NP, Bavaria JE, Kotloff RM. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with sarcoidosis listed for lung transplantation. Chest. 2001;120:873–880. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.3.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorr AF, Davies DB, Nathan SD. Predicting mortality in patients with sarcoidosis awaiting lung transplantation. Chest. 2003;124:922–928. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.3.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulica R, Teirstein AS, Kakarla S, Nemani N, Behnegar A, Padilla ML. Distinctive clinical, radiographic, and functional characteristics of patients with sarcoidosis-related pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2005;128:1483–1489. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzato G, Pezzano A, Sala G, Merlini R, Ladelli L, Tansini G, Montanari G, Bertoli L. Right heart impairment in sarcoidosis: haemodynamic and echocardiographic study. Eur J Respir Dis. 1983;64:121–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barst RJ, Ratner SJ. Sarcoidosis and reactive pulmonary hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:2112–2114. doi: 10.1001/archinte.145.11.2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes H, Humbert M, Capron F, Brauner M, Sitbon O, Battesti JP, Simonneau G, Valeyre D. Pulmonary hypertension associated with sarcoidosis: mechanisms, haemodynamics and prognosis. Thorax. 2006;61:68–74. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.042838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston IR, Klinger JR, Landzberg MJ, Houtchens J, Nelson D, Hill NS. Vasoresponsiveness of sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2001;120:866–872. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.3.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfes DB, Weiss MA, Sanders MA. Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis with suppurative features. Am J Clin Pathol. 1984;82:602–607. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/82.5.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popper HH, Klemen H, Colby TV, Churg A. Necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis – is it different from nodular sarcoidosis? Pneumologie. 2003;57:268–271. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman RP, Drent M, Kavuru M, Judson MA, Costabel U, du Bois R, Albera C, Brutsche M, Davis G, Donohue JF, et al. Infliximab therapy in patients with chronic sarcoidosis and pulmonary involvement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:795–802. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-402OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman RP, Engel PJ, Meyer CA, Barrett AB, Lower EE. Pulmonary hypertension in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley RJ, Metersky ML. Successful treatment of sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension with bosentan. Respiration. 2005 doi: 10.1159/000089815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Kashour T, Philipp R. Secondary pulmonary arterial hypertension: treated with endothelin receptor blockade. Tex Heart Inst J. 2005;32:405–410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughan AR, Williams BR. Cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart. 2006;92:282–288. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.080481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar A, Mana J, Sala J, Landoni BR, Manresa F. Combined portal and pulmonary hypertension in sarcoidosis. Respiration. 1994;61:117–119. doi: 10.1159/000196320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portier F, Lerebours-Pigeonniere G, Thiberville L, Dominique S, Tayot J, Muir JF, Nouvet G. Sarcoidosis simulating a pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Rev Mal Respir. 1991;8:101–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffstein V, Ranganathan N, Mullen JB. Sarcoidosis simulating pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:809–811. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.4.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resten A, Maitre S, Capron F, Simonneau G, Musset D. Pulmonary hypertension: CT findings in pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. J Radiol. 2003;84:1739–1745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer SM, Robinson LJ, Wang A, Gossage JR, Bashore T, Tapson VF. Massive pulmonary edema and death after prostacyclin infusion in a patient with pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. Chest. 1998;113:237–240. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonneau G, Galie N, Rubin LJ, Langleben D, Seeger W, Domenighetti G, Gibbs S, Lebrec D, Speich R, Beghetti M, et al. Clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;(Suppl S):5S–12S. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]