Abstract

Optimal outcome in spine surgery is dependent of the coordination of efforts by the surgeon, anesthesiologist, and neurophysiologist. This is perhaps best illustrated by the rising use of intraoperative spinal cord monitoring for complex spine surgery. The challenges presented by neurophysiologic monitoring, in particular the use of somatosensory and motor evoked potentials, requires an understanding by each member for the team of the proposed operative procedure as well as an ability to help differentiate clinically important signal changes from false positive changes. Surgical, anesthetic, and monitoring issues need to be addressed when relying on this form of monitoring to reduce the potential of negative outcomes in spine surgery. This article provides a practical overview from the perspective of the neurophysiologist, the anesthesiologist, and the surgeon on the requirements which must be understood by these participants in order to successfully contribute to a positive outcome when a patient is undergoing complex spine surgery.

Keywords: Anesthesia, Spine surgery, Spinal cord monitoring, Somatosensory evoked potentials, Motor evoked potentials

Neurologic considerations

The role of intraoperative monitoring (IOM) in spinal surgery is to evaluate the integrity of the nervous system continuously while patients undergo procedures that have the potential to cause injury to the nervous system, particularly the spinal cord and spinal nerves. Since patients are under general anesthesia, techniques for examining the nervous system are limited to those that can be applied to an unconscious subject. The task of monitoring personnel is to: (1) identify neural irritation or injury at a time when the surgeon can take steps to reduce or reverse it and (2) define the nature of the injury in a way that will allow the surgeon to complete the procedure without risking further injury. Ideally, this is done in an efficient manner without interrupting the flow of the operation and producing unnecessary interruptions.

The risk of neural injury has long been recognized, and maneuvers such as the Stagnara wake-up test were devised to try to detect and correct problems before they become irreversible [68]. Electrophysiological IOM techniques have evolved, and they now provide timely evaluation and feedback to the surgeon at a point where interventions can be taken to prevent irreversible neural damage. The etiology of neural injury is varied, and mechanisms can range from structural compromise related to abnormal spinal anatomy to instrumentation-related injury and vascular insufficiency. The structures at risk include peripheral nerves, spinal roots, and spinal cord.

The decision to perform IOM involves many factors, and the approach to monitoring is a team effort that includes the surgeon, monitoring personnel, and the anesthesiologist. There must be an assessment of the risk of injury from a given operative procedure. The risk can vary from highly likely to none at all, and the surgeon and monitoring team must decide jointly on the need for monitoring. Since there are a variety of monitoring techniques and strategies, the surgeon and the monitoring team must also determine which neural structures are at risk so the appropriate monitoring protocol can be used.

Somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP) monitoring

The earliest form of electrophysiological monitoring for spinal surgery was SSEP recording. SSEPs were first used for monitoring scoliosis surgery [6]. SSEP recording was adapted for use in the operating room to take advantage of the ability to assess the integrity of sensory pathways that traverse the spinal cord in areas that are at risk for injury. SSEPs can be recorded repeatedly and reproducibly, and the spinal pathways they traverse are sensitive indicators of the integrity of the cord.

SSEP recording is done by stimulation of peripheral nerves while recording from multiple sites that span the site of the surgery. Typically, the stimulation site is either the posterior tibial nerve in the leg or the median nerve in the arm. When the tibial nerve is stimulated, recordings are made from electrodes over the popliteal space, the cervical spine, and the scalp. When the median nerve is stimulated, electrodes are placed over the brachial plexus in the supraclavicular fossa, the rostral cervical spine, and the scalp. The level of surgery determines the choice of stimulation and recording sites. If the surgical site is the cervical spine, median nerve SSEPs will be monitored, and if the site of the surgery is below the cervical level, tibial SSEPs are monitored. The choice of a recording site over a peripheral site such as the popliteal or supraclavicular spaces provides a control that allows the monitoring team to know that the recording system is intact and functioning properly. Since the peripheral sites are caudal to any potential site of injury, potentials should be recordable from those locations even if there is malfunction at a more rostral level. When there is a loss or absence of recordings at the peripheral site, this alerts the monitoring staff to the presence of either a technical malfunction or abnormality in the peripheral conduction pathways instead of spinal level neural injury. On the other hand, if there is injury at the site of the surgery, the peripheral potentials should not be affected. Dermatomal stimulation techniques have far less applicability in the operative setting and will not be discussed here.

The recordings from electrodes over the cervical spine and the scalp are potentials that arise from neural structures in the brainstem and cerebral cortex. The potentials recorded from the cervical spine originate in brainstem structures, and those recorded from the scalp originate in cortical or subcortical structures [41]. Recordings are typically made from both sites which are rostral to the site of the surgery. The recordings are made using signal averaging techniques that allow the small microvolt-range potentials to be extracted from electrically noisy background activity. Signal averaging requires multiple stimulus repetitions, and the typical recording time is ∼5 min. This means that a new SSEP recording can be generated at ∼5-min intervals.

Motor evoked potential (MEP) monitoring

The introduction of SSEP monitoring to spinal surgery reduced the rate of intraoperative injury by a significant amount. A survey of the Scoliosis Research Society and he European Spinal Deformities Society documented a reduction in injury rate from 0.7 to 4.0% in the pre-SSEP monitoring days to less than 0.55% with SSEP monitoring [10]. Nevertheless, there have been well-documented cases of patients who had SSEP monitoring that failed to detect significant spinal cord injury [25, 49, 70]. These cases are described as false negatives, since the SSEPs were unchanged from baseline recordings. The pathophysiology of such cases is felt to be related to vascular injury to the spinal cord. The primary conduction pathway of the SSEPs in the spinal cord is the dorsal columns [73]. The blood supply for the dorsal columns differs from that of the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord, which derives its blood supply from the anterior spinal artery. In theory, a loss of adequate blood flow through the anterior spinal artery would put the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord at risk, but the dorsal columns could remain intact. In this setting, SSEP recordings might not be affected.

In recognition of this risk, MEP recording techniques were devised. The descending motor pathways run primarily in the lateral columns of the spinal cord, and their blood supply would be affected by a loss of perfusion through the anterior spinal artery. Stimulation of descending motor pathways intraoperatively provides a supplementary monitoring capability that can serve as a check on the results of SSEP monitoring. A number of MEP recording techniques have been devised, including direct stimulation of the rostral spinal cord and transcranial magnetic cortical stimulation [13, 63]. In practice, however, the most commonly used stimulation technique is transcranial electrical stimulation [7, 62]. Corkscrew electrodes placed in the scalp overlying the cortical motor areas are used for stimulation to produce transcranial electrical MEPs (tceMEP). Electrical stimulation of the motor cortex in the setting of the operating room is possible due to the availability of stimulators that can deliver sufficient current density and repetition rates to stimulate the anesthetized brain through the intact skull [37, 38]. The most commonly used stimulation protocol involves multiple-pulse stimulation, where 4–6 stimuli are delivered at interstimulus intervals of 2.0 ms [24]. Although both cerebral hemispheres can be activated simultaneously, the hemisphere underlying the stimulating anode is preferentially activated, and a measure of lateralized recording is possible. Recordings are made from subcutaneous or intramuscular needle electrodes placed in multiple muscles in the arms and legs. The recording equipment available currently allows for simultaneous recording from eight or more sites bilaterally. Both proximal and distal muscles are monitored, but more consistent responses are evoked from distal muscles (Tibialis anterior and Abductor hallucis longis for the lower extremities, intrinsic muscles for the upper extremities).

MEP recording has advantages and disadvantages. The major disadvantage is that neuromuscular blockade must be minimized or avoided. As a consequence, each stimulation will produce movement of limb and axial muscles. The amount of movement can be minimized by using a threshold-level stimulation protocol that is based on determining the lowest stimulus intensity that produces consistent muscle activation [8]. The variable that is used for monitoring for this technique is the change in threshold needed to elicit muscle activation. Even with this technique, however, it is necessary to warn the surgeon when a stimulus train is going to be delivered to minimize the risk of movement during a critical part of the surgery. In addition, MEP recording introduces constraints into choice of anesthetic agents (vida infra).

Cerebral hemisphere stimulation introduces other risks. The stimulation directly activates masseter muscles, and forceful contraction can produce tongue laceration, tooth fracture or even mandible fracture. These risks can be minimized or eliminated by proper use of bite blocks (see Fig. 1). MEP recording is considered to be contraindicated in patients with epilepsy, cortical lesions, skull defects, increased intracranial pressure, surgically implanted intracranial devices, cardiac pacemakers or other implanted pumps. Actual experience with tceMEP monitoring has seen a very low incidence of complications [36].

Fig. 1.

During MEP stimulation, prevention of a tongue bite requires the insertion of three soft bite blocks in the mouth. One is placed between the molars on each side and one is placed centrally. These replace the use of a hard orophayngeal airway (e.g., Guedel oropharyngeal airway)

The major advantage of MEP monitoring is that the time required for any one stimulation is very brief. Meaningful monitoring information can be obtained in a minute or less, and multiple stimulations can be done without interrupting the ongoing flow of the surgery. Unlike SSEP monitoring, which requires a turn-around time of ∼5 min, MEP information can be updated multiple times during critical portions of the operation.

Free-run and stimulated EMG monitoring

An additional benefit of MEP monitoring is that recording electrodes are in place for monitoring from muscles. In addition to recording the response to motor pathway stimulation, ongoing spontaneous electromyographic (EMG) activity can be monitored. Free-run EMG activity can be monitored continuously when peripheral nerves or roots are at risk for potential injury. When nerves are irritated by, for example, stretch or compression, they discharge spontaneously, producing trains of motor unit potential discharges in the muscles they innervate (see case example Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Preop lateral X-rays of a 75-year-old patient with thoracolumbar kyphosis above a previous lumbar fusion (a). The planned procedure was a pedicle substraction osteotomy at L2 (dashed lines). Electrophysiology monitoring consists of SSEP, MEP, and EMG. During the closure of the osteotomy, the SSEP and MEP remained perfectly normal; however, on the right side the iliopsoas muscle started to fire with burst activity (b). The foramen containing the L1 and L2 nerve was checked further for possible compression. The foramen was further cleaned of soft tissue and the Iliopsoas decreased its firing with a train of activity for 5 min (c) and returned to baseline thereafter (d). Postoperatively, the patient has no complaints and the strength in the hip flexor was normal. Postoperative X-rays (e). In the oval the pedicle substraction osteotomy

These neurotonic discharges can be detected by monitoring personnel who watch the EMG tracings, but the surgical team can also hear the electrical discharges as they are amplified through the speakers attached to the monitoring equipment. Surgeons can often correlate specific activities they are doing, such as retracting a nerve root, with the occurrence of neurotonic discharges, since the feedback is more or less instantaneous. This allows modification of the procedure in a timely way to reduce injury to the roots.

Free-run EMG monitoring is most useful for procedures at spinal levels where nerve roots are most likely to be at risk of injury. Most commonly, this involves procedures at the lumbar level [20], but cervical level procedures are also amenable to free-run EMG monitoring.

Peripheral nerves and nerve roots are also exquisitely sensitive to direct stimulation. If a stimulating electrode is placed directly on an exposed nerve, it can be depolarized with a very low-intensity stimulus. If there is tissue interposed between the nerve and the stimulator, a much stronger stimulus is needed to produce depolarization. This aspect of the physiology of nerve can be used to monitor the safety of pedicle screw placement. When pedicle screws breach or fracture the pedicle, which is estimated to occur 5–6% of the time [24], they can come to rest against nerve roots. The potential for nerve root injury, pain, and instability can be reduced if the pedicle screw is stimulated electrically after placement. If the screw is not in proximity to nerve, either no muscle activation or activation only with very strong stimuli will be observed. If it is close to a nerve, compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) will be produced in muscles it innervates in response to very low intensity stimuli. EMG monitoring of pedicle screw stimulation is more sensitive than fluoroscopy and palpation in detecting improper screw placement [35]. Elicitation of CMAPs with a stimulus intensity of 10 mA or less is felt to indicate a breach of the pedicle, and CMAPs produced by stimuli less than 6 mA represent direct contact of the screw with a nerve root.

Warning criteria

In most cases, a combination of SSEP and tceMEP monitoring provides optimal safety. As noted above, the level of the surgery will determine which nerves and muscles will be monitored. In procedures that are limited to the lumbar spine, free-run EMG may be appropriate, and it can be supplemented by pedicle screw stimulation, where indicate.

The operating room is an electrically hostile environment, and electrical interference and other artifacts can complicate interpretation of the monitoring potentials. Variations in the depth of anesthesia, and changes in body temperature and blood pressure can also influence potentials. The monitoring personnel must be able to detect and understand the source of such variables in order to deal with them appropriately. It is not necessary or desirable to alert the surgeon to every change in the SSEP or tceMEP recordings, particularly if they are not physiologically meaningful. On the other hand, it is absolutely crucial to warn the surgeon when a change in the potentials that may reflect neural injury is observed. Since there can be moment-to-moment changes in any of the potentials, any variation in the recordings must be sustained and reproducible.

In practical terms, this means that a physiologically meaningful change in the potentials should be seen in more than one recording and, preferably in more than one monitoring modality. A complete loss of potentials in the appropriate monitoring channels in either SSEPs or tceMEPs, or both, is clearly an indication of significant disturbance of spinal cord function. The surgeon should be alerted to this occurrence in as timely a manner as possible. Given the fact that SSEP recordings require a 5-min lag time, tceMEP recordings are often more useful for confirming a loss of signals.

There is no clear consensus as to what degree of change in SSEP or tceMEP recordings is meaningful. In general for SSEPs, a loss of amplitude of SSEPs of more than 50% of baseline recordings and or increased of latency of more than 10% are considered as meaningful. For MEPs, a 50% increase in stimulus intensity needed to invoke tceMEPs is taken to be a significant change. It should be emphasized again, however, that the change is more meaningful if it is sustained for more than one recording and correspond to a surgical event that matches the findings.

Anesthetic considerations

The requirements for intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring place additional demands on the anesthesiologist. In addition to the usual concerns of providing anesthesia for the surgical procedure, it is necessary to tailor the anesthetic so that it helps maximize signal acquisition. During spine surgery, a variety of monitoring modalities can be employed depending on the operative site, the proposed procedure and surgical preference. At the present time, the measurement of somatosensory (SSEP) and motor evoked (MEP) potentials as a method to reduce neural risk and improve intraoperative surgical decision making are the most frequently used modalities that will impact on the anesthetic management of the patient. This combination of monitoring modalities provides for the ability to independently verify spinal cord integrity by two independent, but parallel systems, which should increase the opportunity to detect injury to either the motor and/or sensory pathways. An appreciation of the interaction of anesthetic agents on evoked potentials will allow the anesthesiologist to optimize the care provided to patient undergoing spine surgery.

Of the various monitoring modalities, tceMEPs are particularly sensitive to interference by anesthetic agents. Given that tceMEPs are the more difficult to monitor during operative procedures, anesthetic conditions that are optimized for tceMEPs will usually produce acceptable SSEPs. The neurologic condition of the patient can influence the likelihood of success for monitoring evoked potentials. As an example, in a neurologically intact child, one can consistently obtain intraoperative MEPs, but in a child with preexisting neurologic deficits, obtaining these signals may be difficult in as much as 61% of children [11, 45, 71]. Clearly, the anesthetic approach needs to be optimized in order to obtain useful potentials that can help guide the surgical progress.

Most anesthetic agents depress evoked response amplitudes and increase latencies which makes intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring more difficult. Notable exceptions include the intravenous anesthetic agents etomidate and ketamine, both of which enhance SSEP and MEP amplitudes. The use of etomidate is limited to induction of anesthesia in potentially hemodynamically unstable patients since infusion of etomidate has been associated with adrenocortical suppression [9, 69]. Ketamine is used frequently in this patient population and will be discussed in greater detail below.

Halogenated anesthetics

All halogenated inhalational agents produce a dose-related increase in latency and reduction in the amplitude of cortically recorded SSEPs [28, 74]. It is also noteworthy that cortical SSEPs are more sensitive to interference than are subcortical or peripherally acquired potentials. As mentioned previously, MEPs are more sensitive to interference by anesthetics and are easily abolished by halogenated inhalational agents. In patients subjected to partial neuromuscular blockade, the halothane, isoflurane, and sevoflurane significantly reduced the amplitudes of tceMEPs at a concentration of 1.0 MAC, with the effect being less for halothane at 0.5 MAC when compared to isoflurane and sevoflurane. This was partially due to a lesser degree of neuromuscular blockade [58]. Generally speaking, keeping the concentration of the volatile anesthetic to less than 0.5 MAC should allow for the acquisition of acceptable MEPs. Our recommended approach to monitoring MEPs is to avoid volatile anesthetic agents and instead rely on a propofol-based anesthetic.

Nitrous oxide

The anesthetic gas nitrous oxide reduces SSEP cortical amplitude and increases latency when used alone or when combined with halogenated inhalational agents, opioids or propofol [47, 65, 67, 72]. Nitrous oxide also dose-dependently reduces the amplitude of MEPs when administered with propofol [51]. On an equipotent basis, nitrous oxide produces more profound changes in cortical SSEPs and muscle recordings from transcranial MEPs whereas its effects on subcortical and peripheral sensory responses and epidurally recorded MEPs are minimal. Given these limitations, the preferred anesthetic plan is to avoid inhalational agents, including nitrous oxide, for optimal MEP monitoring even when using high-frequency stimulation techniques [33]. While there are conflicting results on the effects of nitrous oxide on MEPs, in the presence of higher doses of propofol, significant suppression of MEPs have been reported leading to the suggestion that nitrous oxide be avoided when a higher dose of propofol is required [51].

Regardless whether inhalational anesthetics or intravenous anesthetics are used during spine operations where SSEPs and MEPs are being monitored, it is important to attempt to maintain constant (steady-state) concentrations of anesthetics. Bolus administration or acute changes in inhalational anesthetics can result in marked alterations in evoked potentials which must be distinguished from potential neuronal injury. When properly conducted, both approaches generally yield anesthetic conditions appropriate for intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring. However, the preferred anesthetic plan is to avoid inhalational agents for optimal MEP monitoring even when using high-frequency stimulation technique. Practically speaking, the use of a total intravenous anesthetic technique (TIVA) should give the optimal conditions for the operative procedure and the intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring. A recommended balanced anesthetic approach that has been successfully used to achieve acceptable intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring is described below. Typically, one utilizes the intravenous anesthetic agent propofol, a synthetic narcotic such as sufentanil, an infusion of the local aesthetic lidocaine and frequently the NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine. Generally speaking, all four of these drugs are initially administered intravenously as a bolus in order to induce anesthesia and then are administered as continuous infusions in order to maintain adequate steady-state conditions. In addition, a neuromuscular blocking agent (either a depolarizing agent such as succinylcholine or a nondepolarizing agent such as rocuronium) may be administered in order to facilitate endotracheal intubation.

Propofol

Propofol, a short-acting intravenous anesthetic agent, is used for the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia. As part of a balance anesthetic, it is typically administered in the range of 75–150 mcg/kg/min for maintenance of anesthesia. Propofol produces a dose-dependent reduction in the amplitude of MEPs, but has no effect on the latency [40]. MEP monitoring was made possible through the application of train pulse stimulation which enhanced MEP responses [30]. A comparison of the effects of propofol with the inhaled anesthetics isoflurane plus nitrous oxide on MEPs revealed that with multipulse stimulation propofol provided better recording conditions [48]. These findings support the current position of propofol being the standard anesthetic approach for IOM recording of MEPs. Propofol lacks analgesic properties and thus needs to be supplemented with a narcotic and/or with ketamine administration. When it administered peripherally, it often causes pain on injection which can be minimized by pre- or co-administration with lidocaine [32].

Narcotic infusions

Opioids have a limited impact on MEPs, based on laboratory reports and clinical experience although there are reports suggesting a suppressive effect of alfentanil, fentanyl, remifentanil, and sufentanil [29, 53, 54]. In contemporary practice, the synthetic opioids fentanyl, sufentanil or remifentanil are frequently administered as intraoperative and postoperative analgesic agents for spine surgery. The latter two are typically delivered as continuous infusions. The principal advantage of the continuous infusion is the avoidance of marked concentration differences which help minimize a confounding variable in the measurement of MEPs.

Sufentanil has an advantage due to the contact-sensitive half-life of remifentanil and the significant amount of pain these patients often experience along with the frequent occurrence of chronic pain conditions presenting in this patient population [55]. It is administered typically with a loading dose of 0.5–1 mcg/kg followed by an infusion of 0.2–0.5 mcg/kg/h. This infusion is usually terminated 30–60 min before the end of the surgery depending on the severity of the patient’s preoperative pain, prior narcotic usage, the duration of the operative procedure and the length of the operation. When used as part of a balanced anesthetic technique, this should allow for sufficient analgesia to be present at the time of emergence from anesthesia.

Lidocaine

Lidocaine is used as part of a balanced anesthetic technique due to it’s various beneficial properties. This local anesthetic has been shown to reduce the amount of volatile or intravenous anesthetics needed to maintain stable hemodynamic conditions. In addition, lidocaine has been shown to possess antianflammatory properties and analgesic properties [16, 21, 26, 27]. While lidocaine has been shown to depress the amplitude and prolong the latency of SSEPs, the SSEP waveforms were preserved and interpretable when used as part of a narcotic based anesthetic [56].

Lidocaine infusions are recommended to be administered as a loading dose of 1.5 mg/kg as part of the induction of anesthesia which is followed by lidocaine infusion at a rate of 40 mcg/kg/h. This dose should result in plasma concentrations that are comparable to those achieved when a lidocaine epidural is used for a surgical procedure, i.e., a concentration that is clinically relevant and less than one would be used as an antiarrhymithic agent. The maximum recommended dose is 4 mg/min in order to help minimize the potential for excessive accumulation when given for longer operative procedures. Lidocaine can be continued throughout the entire surgical procedure and into the post-operative period. Alternatively, lidocaine can be discontinued at the completion of the surgical procedure.

Ketamine

Ketamine, a dissociative anesthetic agent, is a NMDA receptor antagonist that offers several advantages when used as part of an anesthetic technique for patients undergoing spine surgery with concurrent intraoperative neurophysiologic monitoring. A ketamine infusion is particularly useful for chronic pain patients, especially those undergoing more major operations that are associated with significant postoperative pain. While ketamine is recognized as a dissociative anesthetic with intense analgesic properties, it also has as an added benefit the ability to enhance the signals acquired when monitoring evoked potentials. This can be achieved with clinically relevant doses [14]. While some authors have advocated doses of ketamine that are on the high side in order to enhance the evoked potentials, the downside of this approach is the greater likelihood that the patient will experience psychomimetic effects upon emergence from anesthesia [30]. While the use of ketamine during surgical procedures is well established, controversy remains as to its utility for controlling postoperative pain, especially in the setting of chronic pain [3, 22]. Many patients undergoing general anesthesia are now being monitored by one of the various EEG-derived awareness monitors. It is noteworthy that the intraoperative use of ketamine can result in an artificially elevated value on these awareness monitors (e.g., Aspect BIS, Sedline PSI or Datex-Ohmeda State and Response Entropy values) while in reality, the patient is actually becoming more deeply anesthetized [19].

The dose we recommend for surgical procedures of the spine is a loading dose of 0.5–1.0 mg/kg as part of the induction of the patient which is followed by an infusion of 0.3 mg/kg/h. The ketamine is administered throughout the operative procedure and is typically terminated at least 30 min prior to the end of the surgical procedure. The easiest way to administer this NMDA antagonist is to co-administer it with the lidocaine infusion. The standard concentration of lidocaine is an 8% solution in dextrose-based crystalloid. Ketamine (250 mg) is added to a 250 ml IV bag of lidocaine. When the infusion pump is set for a lidocaine dose of 40 mcg/kg/min (vida supra), the resultant ketamine dose that will be administered is 0.3 mg/kg/h. The ketamine/lidocaine solution will typically be administered throughout the operative procedure and will be discontinued ∼30 min before emergence is anticipated in order to minimize the psychomimetic effects of the drug. A practical way to accomplish this is to remove the ketamine from the lidocaine infusion by replacing the lidocaine/ketamine IV bag with a lidocaine, flushing the pump tubing and then continuing at the previously determined infusion rate. An additional benefit from utilizing lidocaine/ketamine infusions is that it reduces the requirement of propofol and/or inhalational anesthetics via the MAC sparing effect of lidocaine as well as that of ketamine. When used properly, this combination helps produce a more reliable wake-up at the conclusion of the operation.

Neuromuscular blocking agents

MEPs are impacted by the extent of neuromuscular blockade. Partial blockade, in order to reduce the potential for movement during the surgical procedure, has been advocated for spine surgery, but must be maintained in a relatively narrow range. The extent of neuromuscular blockade has an impact on the ability of the monitoring personal to achieve acceptable recordings [1, 66]. In order to minimize variations in the degree of neuromuscular blockade with their possible impact on MEP recordings, it is necessary to administer the neuromuscular blocking agents by continuous infusion, preferably using a closed-loop feedback approach. We avoid the use of neuromuscular blocking agents to prevent any deterioration in the quality of the MEPs. If the patient is not tolerating an adequate anesthetic for the surgical procedure, the administration of a low-dose phenylephrine infusion will allow for a higher concentration of anesthetic agents to be tolerated.

Temperature effects

Marked temperature-related drops in evoked potential amplitude may occur after exposure of the spine but before instrumentation and deformity correction. Hypothermia may increase false-negative outcomes [59]. With hypothermia, the MEPs demonstrate a gradual increase in onset as esophageal temperature decreased from 38 to 32°C. An increase in stimulation threshold was also observed at lower temperatures. This is consistent with both cortical initiation and peripheral conduction being affected by the drop in temperature. In contrast, hyperthermia reduced the latency and increased the conduction velocity of evoked potentials. Spinal SSEP amplitudes were unchanged, whereas cortical SSEPs and spinal MEPs deteriorated above 42°C. Hypothermia increased latency and decreased conduction velocities. Below 28°C, the amplitude of the spinal MEPs decreased and the cortical SSEPs and spinal MEPs disappeared. With both hyperthermia and hypothermia causing significant changes in the latency of MEPs and SSEPs, it has been suggested that evoked potential measurements be performed in a range of 2–2.5°C above or below the baseline temperature [43, 52].

Ventilation and oxygenation

Hypoxemia can cause evoked potential deterioration before other clinical parameters are changed. Alterations in carbon dioxide are known to alter spinal cord and cortical blood flow. The most notable changes in cortical SEP occur when the carbon dioxide tension is extremely low, suggesting excessive vasoconstriction may produce ischemia (PaCO2 20 mmHg). This effect has been suggested to contribute to alterations in SEP during spinal surgery and may be expected to produce some MEP changes. Because hypocapnia may produce small SEP changes, and possibly MEP, baseline recordings should be acquired prior to initiation of hyperventilation [17].

Blood rheology and hemodyamic effects

Changes in hematocrit can alter both oxygen carrying capacity and blood viscosity. The maximum oxygen delivery is often thought to occur in a midrange hematocrit (30–32%). SSEP response changes with hematocrit are consistent with this optimum range. An increase in amplitude has been noted with mild anemia, followed by an increase in latency at hematocrits of 10–15%; further latency changes and amplitude reductions were observed at hematocrits less than 10%. These changes are partially restored by an increase in the hematocrit [39]. No comparable studies have been performed with MEPs.

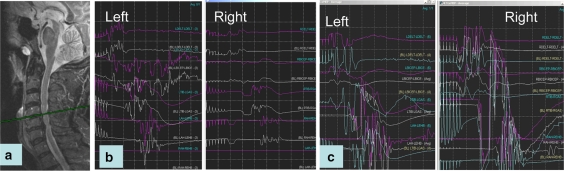

Minor drops in blood pressure may result in substantial recording changes that reverse when perfusion pressure is increased [59, 60] (see Fig. 3). Numerous studies have demonstrated a threshold relationship between regional cerebral blood flow and cortical evoked responses. The cortical SSEPs remain normal until blood flow is reduced to ∼20 ml/min/100 g. At more restricted blood flows of between 15 and 18 ml/min/100 g of tissue, the SSEP is altered and lost. As with anesthetic effects, subcortical responses appear less sensitive than cortical responses to reductions in blood flow. Local factors may produce regional ischemia not predicted by systemic blood pressure. For example, during spinal surgery, the effects of hypotension may be aggravated by spinal distraction, such that an acceptable limit of systemic hypotension cannot be determined without monitoring. This was illustrated by the demonstration that application of direct pressure during induced hypotension produced changes in evoked potentials which were associated with loss of lower extremity motor function [5].

Fig. 3.

Patient with cervical myelopathy (a) while being positioned prone on the OR table, he experienced a decrease MEPs on the right side (b) compared to the left side that remained normal. Restoration of normal MEP amplitude was produced by increasing the mean arterial blood pressure (c)

Keys to success

It is important to understand the proposed operative procedure to determine what forms of IOM will be employed. Based on this information, one can choose an anesthetic approach that is designed to maximize signal acquisition while maintaining, supporting, and, if necessary, correcting the physiologic state of the patient. Whenever possible, maintain a constant concentration of the inhalational and/or intravenous anesthetics since rapid alterations in anesthetic concentrations may make interpretation of evoked potentials challenging, especially during critical portions of the operative procedure. Communication with the team, especially the monitoring personnel, when there is a need to make significant changes in the anesthetic management helps place potential interpretation of this information in its proper perspective.

Surgical considerations

Which monitoring option is the most desirable?

The decision of which neurophysiology monitoring option to utilize obviously relies on a team approach between the anesthesiologist, the electrophysiologist, and the surgeon who remains the main stakeholder in the decision:

If the surgery is a simple lumbar surgery (e.g., discectomy or lumbar decompression) without any instrumentation, we do not recommend any special monitoring as such modalities will increase OR time, prevent muscle relaxation and the monitoring is unlikely to alter the surgical outcome.

In the case of lumbar spine surgery with instrumentation, different choices can be taken: The most common one will be the free running EMG and triggered EMG monitoring of the mucles innervated by the segmental nerves where pedicle screws are inserted. We do not use SSEP or MEP for routine instrumented lumbar cases (e.g., L4-S1 fusion) except for more complex cases such as degenerative scoliosis, lumbar spine osteotomy, or spondylolisthesis reduction. Gunnarson, in a retrospective series of 213 consecutive patients, found that the sensitivity of EMG was 100%, but its specificity was only 23% [18]. Therefore, we pay attention to their modification if they correspond to the specific area of the spine we are working in.

For triggered EMG monitoring, we use the classic anode electrode inserted in the spine muscles with the cathode stimulating the pedicle screw once it has been inserted. Other new EMG monitoring modalities (Medtronics, Memphis Tenessee; Nuvasive, San Diego, CA) use a cathode electrode that clips to the pedicle screw probe to provide a real time audible feedback during pedicle screw insertion. A warning sound can be heard when there is stimulation of the nerves during pedicle probe insertion. However, possible concerns of bypassing the electrocautery system and bovie pad possibly resulting in burns have led us to use the classic method of pedicle screw stimulation. If one uses percutaneous insertion of pedicle screws, one should be aware that tapping of the screw path may increase the threshold by compacting the dense trabecular bone [44]. The use of plastic sheet around the pedicle probe will also give a better accuracy of the monitoring by optimizing the thresholds [12]. Confirmation of pedicle screw placement with fluoroscopy is essential.

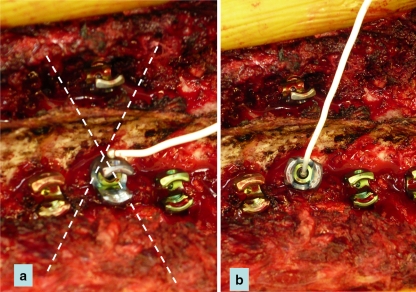

As opposed to the use of monoaxial screw, the use of polyaxial pedicle screws requires the application of the cathode stimulator probe directly to the hexagonal part or directly to the screw shank to avoid a false-negative result. Stimulating a polyaxial screw over the crown of the screw may result in total loss of electrical conduction or a high resistance pattern [2] (see Fig. 4). In the case of a chronically injured nerve with weakness (axonotmesis), the usual acceptable threshold (<10 mamp) of pedicle screw stimulation may be higher [23]. On the other hand, in the case of osteoporosis, the thresholds can be decreased [12].

Fig. 4.

Triggered EMG: In the case of a polyaxial screw, the cathode should not be positioned on the crown of the screw (a) as it may lead to false negative (increased threshold), but rather on the hexagonal part of the screw itself (b)

A positive EMG response may present in the form of a “burst” (see Fig. 2) that is associated with a short term compression or stretch and or a “train” meaning sustained compression over time (see Fig. 2). In the case of EMG changes, whether they occur during screw insertion as free running modifications of the EMG or during stimulation, the surgeon has different choices: Removal of the pedicle screw and probing the path of the screw to make sure it has remained inside the bone, or perform a small laminotomy to expose the medial side of the pedicle and check any potential for nerve injury. In select cases, such as minimal breeching of the pedicle, the screw can be left in place despite a positive triggered response, but this decision must be left to the surgeon’s discretion as it may result in a root irritation. In case of doubt, the pedicle screw should be redirected. In the case of “firing” of the muscles while working in other areas of the spine, it has been our experience that it occurs very frequently and, unless the modifications are sustained, we usually tend to ignore such modifications. However, if spontaneous firing are sustained and are correlated to the area of the spine the surgeon is working on, the surgeon should take the necessary steps (see Fig. 2) until satisfied that the problem has been corrected. EMG seems to have been particularly useful during insertion of percutaneous screw fixation where EMG helps identify suboptimal screw trajectory [44].

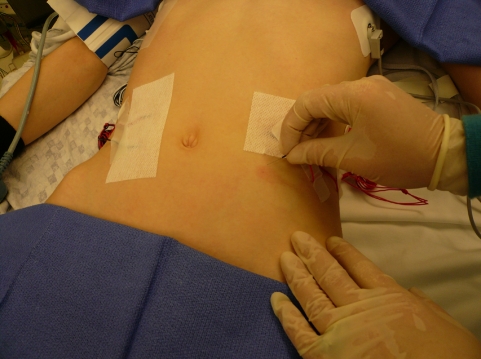

In the case of thoracic or thoracoabdominal surgery, we systematically employ a multimodality IOM approach consisting of SSEP, MEP, and EMG monitoring (e.g., fracture, tumors, deformities, or thoracic myelopathy). If the insertion of pedicle screws in the thoracic spine is planned for correction of a scoliotic deformity, we record the rectus abdominis EMG. This can provide information for the T6–T12 segmental nerves which can be injured during thoracic pedicle screw insertion (see Fig. 5). To assess thoracic pedicle screw placement, triggered EMG thresholds <6.0 mA, coupled with values 60–65% decreased from the mean of all other thresholds in a given patient, should alert the surgeon to suspect a medial or inferior pedicle wall breach [50]. We do no use epidural electrode for either SSEP or MEP recordings for the following reasons. First, they require a laminotomy either rostral, in the case of SSEP, or distal, in the case of MEP, to the levels undergoing instrumentation and can increase the risk for development of a junctional kyphosis subsequently. Secondly, recording the D wave (the epidural response of the MEP) during spinal deformity surgery can lead to false positive due to displacement of the electrodes or movement of the cord itself during the surgical correction of the deformity [64].

Fig. 5.

The insertion of EMG needles in the rectus abdominis muscles (in the case of thoracic pedicle screws for scoliosis surgery) will allow for the monitoring of the T6–T12 segmental nerves

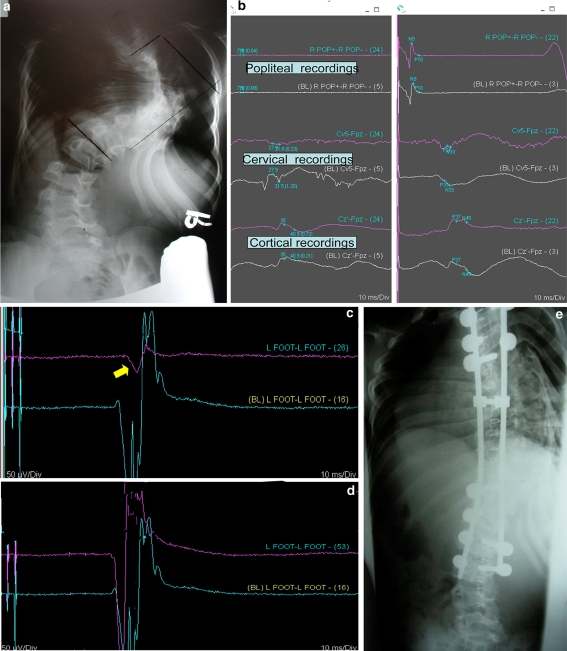

SSEP recordings are continuously obtained throughout the case, except when as long as the electrocautery is required, and signals are averaged with a 5-min time lag. In contrast, MEP recordings require a train stimulation that forces the surgeon to stop his surgical procedure for 15–30 s in order to obtain adequate readings. The MEP result is obtained immediately. During MEP stimulation, the patient may twitch with variable muscle contractions that could induce a complication such as cord contusion with a suction tubing, increased dural retraction with a dura retractor or misplacement of a screw. We obtain MEP recordings after each specific event that can compromise the spinal cord. We routinely run MEP stimulation after the insertion of every single thoracic pedicle screw. During the correction maneuvers of a spinal deformity, we run MEP recordings before correction, after the insertion of the concave rod, then after the insertion the convex rod or after completion of a spine osteotomy. Literature gained from aortic aneurysms surgery has clearly shown that MEP signal change could occur within 3 min of clamping of the aorta, whereas SSEP changes may take between 15 and 30 min to occur. It has been our experience that MEP changes occur very rapidly and can be reverted to baseline if proper corrective maneuvers are taken (see Fig. 6). Return of SSEP to baseline will at least require the time necessary for signal acquisition and can be observed once the insult has been corrected [46]. As insult to the cord can be related to an ischemic event, we recommend the continuation of SSEP and MEP monitoring until the end of the case. No wake up test is done if the electrophysiology recordings remain normal throughout the case due to the high negative predictive value of multimodality IOM

Fig. 6.

a Twelve-year-old boy with 120° curve will undergo posterior release, concave costoplasties and posterior instrumentation and fusion. b Throughout the surgery the SSEPs remained normal (baseline recordings are represented in blue and the current in purple). c During the insertion of the convex rod, an 80% decrease in the MEP amplitude in left foot was noted (yellow arrow). The baseline recording is in blue; the current recording is in purple. The right side (not shown) remained normal. d Return of baseline MEP in the foot 5 min after decreasing the spine correction. The blue (baseline) and the purple (current) recordings show equal amplitudes. e Postoperatively, the patient was neurologically intact

In the case of cervical spine surgery, we routinely do multimodality spinal cord monitoring yet some surgeons may argue that in simple cases of cervical radiculopathy requiring anterior cervical fusion spinal cord monitoring adds little to the safety of the surgery. However, for patients presenting with cervical myelopathy or who have preexisting cervical stenosis and who will have instrumentation reconstruction of the spine, we strongly recommend such monitoring. Because of he high incidence of postoperative C5 nerve palsy in cervical spine surgery like laminoplasty or laminectomy, we strongly recommend the monitoring of the deltoid and biceps activity on the top of recording he classic distal intrinsic muscles. Such TcMEP and EMG at the level of C5 can decrease the incidence of C5 nerve palsy [15]. During surgery for cervical myelopathy we routinely run MEP every 15 min during the spinal decompression.

Positioning the patient and spinal cord monitoring

Positioning of the spine patient may have adverse outcome on the SCM and potential neurologic complications. SCM changes can occur during positioning. As an example, the blood pressure may drop during positioning; restoration of an adequate blood pressure will correct the problem (see Fig. 3). In patients with cervical myelopathy, positioning the head in a position of extension may be responsible for a loss of signals. Repositioning the head can result in restoration of signals. Cervical spine fractures or instabilities can also see changes during positioning. In cervical surgery, a modification of the upper extremities signal is more often related to a brachial plexus neurapraxia due to the taping of the shoulders in order to visualize the lower cervical spine under C-arm fluoroscopy. Schwartz, in a series of 3,806 patients undergoing anterior cervical spine surgery, identified an incidence of 1.8% of patients who showed intraoperative evidence of impending neurologic injury secondary to positioning, prompting interventional repositioning of the patient. Most of the impending neurologic injuries were involving the brachial plexus after taping the shoulders (65%) followed by impending spinal cord injury due to neck extension 19% [57]. In skeletal dysplasia, Lonstein has reported modifications of SCM that required either head repositioning or changing surgical planning [42]. It should be the rule that after positioning, SSEP and MEP should be monitored as a second baseline to ensure safety.

Course of action in the case of spinal cord monitoring modifications

If there is a modification in the SCM signals, the surgical team should all work together to resolve the issues. The neurophysiologist must look for a possible technical problem, assess all the different monitoring modalities, check electrodes leads if necessary with the understanding that most technical problems are observed in an area unrelated to surgery. The anesthesiologist must determine whether the blood pressure is adequate. In addition, oxygenation, ventilation, and hematocrit should be verified to be in an acceptable range. Finally, any alterations in the anesthetic, particularly bolus administration of medications, need to be reconciled with the alterations in SCM signals. If there is no reason to believe that the signal change is related to the surgery itself, one could consider that addition of ketamine as was describe previously. In the absence of obvious technical or anesthetic reasons, the cause must be thought to be surgical. In the case of SSEP modifications, the surgeon must ask immediately for MEP recording to be checked. If these later remain perfectly normal, it is our opinion that the surgery can be carried out with further repetitive recordings, unless there is a specific reason to believe that only the posterior column of the spinal cord could be affected (e.g., insertion of a posterior laminar hook). In most cases SSEP will return to baseline as a result of the correction of a technical or anesthetic problem.

In the case of MEP changes with or without SSEP changes, the surgical team should immediately note the time of the onset of such an event as the duration of the change is essential for the prognosis. The second thing to determine is whether these modifications correspond to any specific event such as the insertion of a screw or a hook or any corrective maneuvers. If this is the case, immediately removing the implant (hook or screw) judged to be the source of the problem is recommended. If the operator is not aware of any possibly misplaced implant in the canal, we recommend an immediate AP fluoroscopic view to check all the implants. Rotation of the c-arm to visualize each vertebra in their true AP plane without rotation will give a better appreciation of each pedicle screw used in correction of the in spinal deformity. If the signal alterations occurred during the corrective maneuvers, immediately reversing such correction is mandatory. This can be achieved through release of the distractive forces (if any), in situ bending of the rod to decrease the correction, or removing a few implants specifically at the apex of the curve where the spinal cord is the most at risk (see Fig. 6). If the potentials recover, surgery can be carried out without any further correction. If, despite these maneuvers, the potentials are still decreased or absent, we recommend a comprehensive removal of the instrumentation.

In the case of a scoliosis operation, we start to remove first the rods and assess the potentials, then we remove the concave and apical implants, followed by the convex and apical implants. All intracanalar hooks (supra and infralaminar hooks) will also be removed as the blade of the hook may have rotated in the canal. The last implant to be removed are the sublaminar wires (if any) as their removal could further injure the spinal cord. Only the rostral and caudal implants, where the spine has no rotation are left in place, provided the potentials (both MEP and SSEP) were normal during their insertion. Only implants that are judged to be 100% safe can be retained. A wake up test can be performed, if necessary. A postoperative CT myelogram, as opposed to a MRI, should follow immediately the completion of the procedure in the absence of neurologic recovery. In the case of a spinal osteotomy with an unstable spine (e.g., after pedicle substraction osteotomy or osteotomy for ankylosing spondylitis) the implants are retained and the correction is reversed while keeping the rods in place. Assessment of sufficient spinal decompression is necessary. SSEP and MEP recordings are repeated and, if they are still absent or decreased, a wake up test is performed. Leaving the spine without any instrumentation could in this case be extremely dangerous due to the unstable nature of the ostetomy.

Conclusions

Intraoperative multimodality spinal cord monitoring has a sensitivity and specificity close to 100% when one refers to the aortic aneurysm repair literature and to the spinal surgery literature [4, 31, 34, 61]. As opposed to the SSEP alone, which could provide a false negative, SSEP along with MEP can provide the surgical team a constant feedback on the state of the spinal cord. For the spine surgeon, the neurophysiologist and the anesthetist there is a learning curve to master all the tricks of the trade of this complex technology and its surgical and anesthetic applications.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest statement None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Adams DC, Emerson RG, et al. Monitoring of intraoperative motor-evoked potentials under conditions of controlled neuromuscular blockade. Anesth Analg. 1993;77(5):913–918. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson DG, Wierzbowski LR, et al. Pedicle screws with high electrical resistance: a potential source of error with stimulus-evoked EMG. Spine. 2002;27(14):1577–1581. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200207150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annetta MG, Iemma D, et al. Ketamine: new indications for an old drug. Curr Drug Targets. 2005;6(7):789–794. doi: 10.2174/138945005774574533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auerbach JD, Schwartz DM, et al (2006) Detection of impending neurologic injury during surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a comparision of transcranial motor and somatosensory evoked potential monitoring in 1121 consecutive cases. Russel Hibbs Award Winner: Scoliosis Research Society, Monterey, CA, 13–16 Sept 2006

- 5.Brodkey JS, Richards DE, et al. Reversible spinal cord trauma in cats. Additive effects of direct pressure and ischemia. J Neurosurg. 1972;37(5):591–593. doi: 10.3171/jns.1972.37.5.0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown RH, Nash CL., Jr Current status of spinal cord monitoring. Spine. 1979;4(6):466–470. doi: 10.1097/00007632-197911000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke D, Hicks RG. Surgical monitoring of motor pathways. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;15(3):194–205. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199805000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calancie B, Klose KJ, et al. Isoflurane-induced attenuation of motor evoked potentials caused by electrical motor cortex stimulation during surgery. J Neurosurg. 1991;74(6):897–904. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.74.6.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohan P, Wang C, et al. Acute secondary adrenal insufficiency after traumatic brain injury: a prospective study. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(10):2358–2366. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000181735.51183.A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson EG, Sherman JE, et al. Spinal cord monitoring. Results of the Scoliosis Research Society and the European Spinal Deformity Society survey. Spine. 1991;16(8 Suppl):S361–S364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiCindio S, Theroux M, et al (2003) Multimodality monitoring of transcranial electric motor and somatosensory-evoked potentials during surgical correction of spinal deformity in patients with cerebral palsy and other neuromuscular disorders. Spine 28(16):1851–1855; discussion 1855–1856 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Dickerman RD, Guyer R. Intraoperative electromyography for pedicle screws: technique is the key! J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19(6):463. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200608000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edmonds HL, Jr, Paloheimo MP, et al. Transcranial magnetic motor evoked potentials (tcMMEP) for functional monitoring of motor pathways during scoliosis surgery. Spine. 1989;14(7):683–683. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erb TO, Ryhult SE, et al. Improvement of motor-evoked potentials by ketamine and spatial facilitation during spinal surgery in a young child. Anesth Analg. 2005;100(6):1634–1636. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000149896.52608.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan D, Schwartz DM, et al. Intraoperative neurophysiologic detection of iatrogenic C5 nerve root injury during laminectomy for cervical compression myelopathy. Spine. 2002;27(22):2499–2502. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer LG, Bremer M, et al. Local anesthetics attenuate lysophosphatidic acid-induced priming in human neutrophils. Anesth Analg. 2001;92(4):1041–1047. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200104000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gravenstein MA, Sasse F, et al. Effects of hypocapnia on canine spinal, subcortical, and cortical somatosensory-evoked potentials during isoflurane anesthesia. J Clin Monit. 1992;8(2):126–130. doi: 10.1007/BF01617431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunnarsson T, Krassioukov AV, et al. Real-time continuous intraoperative electromyographic and somatosensory evoked potential recordings in spinal surgery: correlation of clinical and electrophysiologic findings in a prospective, consecutive series of 213 cases. Spine. 2004;29(6):677–684. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000115144.30607.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hans P, Dewandre PY, et al. Comparative effects of ketamine on Bispectral Index and spectral entropy of the electroencephalogram under sevoflurane anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94(3):336–340. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harper CM, Jr, Daube JR, et al. Lumbar radiculopathy after spinal fusion for scoliosis. Muscle Nerve. 1988;11(4):386–391. doi: 10.1002/mus.880110416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Himes RS, Jr, DiFazio CA, et al. Effects of lidocaine on the anesthetic requirements for nitrous oxide and halothane. Anesthesiology. 1977;47(5):437–440. doi: 10.1097/00000542-197711000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hocking G, Cousins MJ. Ketamine in chronic pain management: an evidence-based review. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(6):1730–1739. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000086618.28845.9B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holland NR, Lukaczyk TA, et al. Higher electrical stimulus intensities are required to activate chronically compressed nerve roots. Implications for intraoperative electromyographic pedicle screw testing. Spine. 1998;23(2):224–227. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199801150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jameson LC, Sloan TB. Monitoring of the brain and spinal cord. Anesthesiol Clin. 2006;24(4):777–791. doi: 10.1016/j.atc.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones SJ, Buonamassa S, et al. Two cases of quadriparesis following anterior cervical discectomy, with normal perioperative somatosensory evoked potentials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74(2):273–276. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.2.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonsson A, Cassuto J, et al. Inhibition of burn pain by intravenous lignocaine infusion. Lancet. 1991;338(8760):151–152. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90139-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaba A, Laurent SR, et al. Intravenous lidocaine infusion facilitates acute rehabilitation after laparoscopic colectomy. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(1):11–18. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalkman CJ, Drummond JC, et al. Low concentrations of isoflurane abolish motor evoked responses to transcranial electrical stimulation during nitrous oxide/opioid anesthesia in humans. Anesth Analg. 1991;73(4):410–415. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199110000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalkman CJ, Drummond JC, et al. Effects of propofol, etomidate, midazolam, and fentanyl on motor evoked responses to transcranial electrical or magnetic stimulation in humans. Anesthesiology. 1992;76(4):502–509. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199204000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawaguchi M, Sakamoto T, et al. Low dose propofol as a supplement to ketamine-based anesthesia during intraoperative monitoring of motor-evoked potentials. Spine. 2000;25(8):974–979. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200004150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawanishi Y, Munakata H, et al. Usefulness of transcranial motor evoked potentials during thoracoabdominal aortic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(2):456–461. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King SY, Davis FM, et al. Lidocaine for the prevention of pain due to injection of propofol. Anesth Analg. 1992;74(2):246–249. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199202000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kunisawa T, Nagata O, et al. A comparison of the absolute amplitude of motor evoked potentials among groups of patients with various concentrations of nitrous oxide. J Anesth. 2004;18(3):181–184. doi: 10.1007/s00540-004-0245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langeloo DD, Lelivelt A, et al. Transcranial electrical motor-evoked potential monitoring during surgery for spinal deformity: a study of 145 patients. Spine. 2003;28(10):1043–1050. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200305150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leppanen RE, Abnm D, et al. Intraoperative monitoring of segmental spinal nerve root function with free-run and electrically-triggered electromyography and spinal cord function with reflexes and F-responses. A position statement by the American Society of Neurophysiological Monitoring. J Clin Monit Comput. 2005;19(6):437–461. doi: 10.1007/s10877-005-0086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacDonald DB. Safety of intraoperative transcranial electrical stimulation motor evoked potential monitoring. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;19(5):416–429. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200210000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marsden CD, Merton PA, et al. Direct electrical stimulation of corticospinal pathways through the intact scalp in human subjects. Adv Neurol. 1983;39:387–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merton PA, Morton HB. Electrical stimulation of human motor and visual cortex through the scalp. J Physiol. 1980;305:9P–10P. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagao S, Roccaforte P, et al. The effects of isovolemic hemodilution and reinfusion of packed erythrocytes on somatosensory and visual evoked potentials. J Surg Res. 1978;25(6):530–537. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(78)90141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nathan N, Tabaraud F, et al. Influence of propofol concentrations on multipulse transcranial motor evoked potentials. Br J Anaesth. 2003;91(4):493–497. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nuwer MR. Spinal cord monitoring. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:1620–1630. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199912)22:12<1620::AID-MUS2>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ofiram E, Lonstein JE, et al. The disappearing evoked potentials”: a special problem of positioning patients with skeletal dysplasia: case report. Spine. 2006;31(14):E464–E470. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000222122.37415.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oro J, Haghighi SS. Effects of altering core body temperature on somatosensory and motor evoked potentials in rats. Spine. 1992;17(5):498–503. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ozgur BM, Berta S, et al. Automated intraoperative EMG testing during percutaneous pedicle screw placement. Spine J. 2006;6(6):708–713. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Padberg AM, Wilson-Holden TJ, et al. Somatosensory- and motor-evoked potential monitoring without a wake-up test during idiopathic scoliosis surgery. An accepted standard of care. Spine. 1998;23(12):1392–1400. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199806150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papin P, Arlet V, et al. Unusual presentation of spinal cord compression related to misplaced pedicle screws in thoracic scoliosis. Eur Spine J. 1999;8(2):156–159. doi: 10.1007/s005860050147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pechstein U, Cedzich C, et al. Transcranial high-frequency repetitive electrical stimulation for recording myogenic motor evoked potentials with the patient under general anesthesia. Neurosurgery. 1996;39(2):335–343; discussion 343–344. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199608000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pechstein U, Nadstawek J, et al. Isoflurane plus nitrous oxide versus propofol for recording of motor evoked potentials after high frequency repetitive electrical stimulation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;108(2):175–181. doi: 10.1016/S0168-5597(97)00086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pelosi L, Jardine A, et al. Neurological complications of anterior spinal surgery for kyphosis with normal somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66(5):662–664. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.5.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raynor BL, Lenke LG, et al. Can triggered electromyograph thresholds predict safe thoracic pedicle screw placement? Spine. 2002;27(18):2030–2035. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200209150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sakamoto T, Kawaguchi M, et al. Suppressive effect of nitrous oxide on motor evoked potentials can be reversed by train stimulation in rabbits under ketamine/fentanyl anaesthesia, but not with additional propofol. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86(3):395–402. doi: 10.1093/bja/86.3.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sakamoto T, Kawaguchi M, et al. The effect of hypothermia on myogenic motor-evoked potentials to electrical stimulation with a single pulse and a train of pulses under propofol/ketamine/fentanyl anesthesia in rabbits. Anesth Analg. 2003;96(6):1692–1697. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000064202.24119.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scheufler KM, Zentner J. Total intravenous anesthesia for intraoperative monitoring of the motor pathways: an integral view combining clinical and experimental data. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(3):571–579. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.96.3.0571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmid UD, Boll J, et al. Influence of some anesthetic agents on muscle responses to transcranial magnetic cortex stimulation: a pilot study in humans. Neurosurgery. 1992;30(1):85–92. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199201000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scholz J, Steinfath M, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of alfentanil, fentanyl and sufentanil. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1996;31(4):275–292. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199631040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schubert A, Licina MG, et al. Systemic lidocaine and human somatosensory-evoked potentials during sufentanil-isoflurane anaesthesia. Can J Anaesth. 1992;39(6):569–575. doi: 10.1007/BF03008320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwartz DM, Sestokas AK, et al. Neurophysiological identification of position-induced neurologic injury during anterior cervical spine surgery. J Clin Monit Comput. 2006;20(6):437–444. doi: 10.1007/s10877-006-9032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sekimoto K, Nishikawa K, et al. The effects of volatile anesthetics on intraoperative monitoring of myogenic motor-evoked potentials to transcranial electrical stimulation and on partial neuromuscular blockade during propofol/fentanyl/nitrous oxide anesthesia in humans. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2006;18(2):106–111. doi: 10.1097/00008506-200604000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seyal M, Mull B. Mechanisms of signal change during intraoperative somatosensory evoked potential monitoring of the spinal cord. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;19(5):409–415. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith PN, Balzer JR, et al. Intraoperative somatosensory evoked potential monitoring during anterior cervical discectomy and fusion in nonmyelopathic patients—a review of 1,039 cases. Spine J. 2007;7(1):83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sutter M, Eggspühler A, et al (2007) The diagnostic value of multimodal intraoperative monitoring (MIOM) during spine surgery: a prospective study of 1,017 patients. Eur Spine J Suppl 17. (in press). doi:10.1007/s00586-007-0418-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Tabaraud F, Boulesteix JM, et al. Monitoring of the motor pathway during spinal surgery. Spine. 1993;18(5):546–550. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tamaki T, Takano H, et al. Spinal cord monitoring: basic principles and experimental aspects. Cent Nerv Syst Trauma. 1985;2(2):137–149. doi: 10.1089/cns.1985.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ulkatan S, Neuwirth M, et al. Monitoring of scoliosis surgery with epidurally recorded motor evoked potentials (D wave) revealed false results. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(9):2093–2101. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dongen EP, ter Beek HT, et al. Effect of nitrous oxide on myogenic motor potentials evoked by a six pulse train of transcranial electrical stimuli: a possible monitor for aortic surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82(3):323–328. doi: 10.1093/bja/82.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dongen EP, ter Beek HT, et al. Within-patient variability of myogenic motor-evoked potentials to multipulse transcranial electrical stimulation during two levels of partial neuromuscular blockade in aortic surgery. Anesth Analg. 1999;88(1):22–27. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199901000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dongen EP, ter Beek HT, et al. The influence of nitrous oxide to supplement fentanyl/low-dose propofol anesthesia on transcranial myogenic motor-evoked potentials during thoracic aortic surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1999;13(1):30–34. doi: 10.1016/S1053-0770(99)90169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vauzelle C, Stagnara P, et al (1973) Functional monitoring of spinal cord activity during spinal surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res (93):173–178 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Wagner RL, White PF, et al. Inhibition of adrenal steroidogenesis by the anesthetic etomidate. N Engl J Med. 1984;310(22):1415–1421. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198405313102202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wiedemayer H, Sandalcioglu IE, et al. False negative findings in intraoperative SEP monitoring: analysis of 658 consecutive neurosurgical cases and review of published reports. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(2):280–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wilson-Holden TJ, Padberg AM, et al. Efficacy of intraoperative monitoring for pediatric patients with spinal cord pathology undergoing spinal deformity surgery. Spine. 1999;24(16):1685–1692. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199908150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Woodforth IJ, Hicks RG, et al. Variability of motor-evoked potentials recorded during nitrous oxide anesthesia from the tibialis anterior muscle after transcranial electrical stimulation. Anesth Analg. 1996;82(4):744–749. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199604000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yamada T. Neuroanatomic substrates of lower extremity somatosensory evoked potentials. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;17:269–279. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200005000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zentner J, Albrecht T, et al. Influence of halothane, enflurane, and isoflurane on motor evoked potentials. Neurosurgery. 1992;31(2):298–305. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199208000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]