Abstract

The objective of this study was to improve upon leg somatosensory-evoked potential (SEP) monitoring that halves paraplegia risk but can be slow, miss or falsely imply motor injury and omits arm and decussation assessment. We applied four-limb transcranial muscle motor-evoked potential (MEP) and optimized peripheral/cortical SEP monitoring with decussation assessment in 206 thoracolumbar spine surgeries under propofol/opioid anesthesia. SEPs were optimized to minimal averaging time that determined feedback intervals between MEP/SEP sets. Generalized changes defined systemic alterations. Focal decrements (MEP disappearance and/or clear SEP reduction) defined neural compromise and prompted intervention. They were transient (quickly resolved) or protracted (>40 min). Arm and leg MEP/SEP monitorability was 100% and 98/97% (due to neurological pathology). Decussation assessment disclosed sensorimotor non-decussation requiring ipsilateral monitoring in six scoliosis surgeries (2.9%). Feedback intervals were 1–3 min. Systemic changes never produced injury regardless of degree. They were gradual, commonly included MEP/SEP fade and sometimes required large stimulus increments to maintain MEPs or produced >50% SEP reductions. Focal decrements were abrupt; their positive predictive value for injury was 100% when protracted and 13% when transient. Six transient arm decrements predicted one temporary radial nerve injury; five suggested arm neural injury prevention (2.4%). There were 15 leg decrements: six MEP-only, four MEP before SEP, three simultaneous and two SEP-only. Five were protracted, predicting four temporary cord injuries (three motor, one Brown–Sequard) and one temporary radiculopathy. Ten were transient, predicting one temporary sensory cord injury; nine suggested cord injury prevention (4.4%). Two radiculopathies and one temporary delayed paraparesis were unpredicted. The methods are reliable, provide technical/systemic control, adapt to non-decussation and improve spinal cord and arm neural protection. SEP optimization speeds feedback and MEPs should further reduce paraplegia risk. Radiculopathy and delayed paraparesis can evade prediction.

Keywords: Scoliosis, Spine surgery, Intraoperative monitoring, Motor-evoked potentials, Somatosensory-evoked potentials

Introduction

Spine surgery risks spinal cord, nerve root, brachial plexus and peripheral nerve injury. The principal concern of paraplegia strongly motivates spinal cord monitoring. Leg somatosensory-evoked potential (SEP) monitoring halves this risk, but paraplegia can still occur without SEP warning [11, 23]. In addition, SEP deterioration due to dorsal column injury, stimulus failure, distal conduction block and systemic reduction below an arbitrary 50% can falsely imply motor injury [16, 23]. Furthermore, inhalational anesthesia and traditional recording derivations produce low signal to noise ratios (SNRs) that delay surgical feedback by prolonging averaging time [19]. Finally, this approach offers no arm neural protection and does not detect sensorimotor non-decussation that can occur in scoliosis [17].

To address these deficiencies, we have developed a non-invasive method incorporating intravenous anesthesia with four-limb transcranial electric stimulation (TES) muscle motor-evoked potential (MEP) and optimized SEP monitoring including sensorimotor decussation assessment. The aims are to (1) minimize anesthetic-evoked potential depression, (2) avoid false predictions, (3) accelerate feedback by optimizing SEP derivations to highest SNR, (4) provide systemic control and arm neural protection, (5) control for stimulus failure and distal conduction block, and (6) detect and adapt to non-decussation.

We previously reported our initial experience in 33 scoliosis surgeries on neurologically intact patients [16]. The method appeared to fulfill its aims and applied generalized change to identify systemic alterations and focal decrement to prompt intervention instead of percentage criteria. Here, we extend our series and include patients with antecedent neurologic pathology.

Materials and methods

Patients and surgeries

We reviewed 206 consecutively monitored thoracolumbar spine surgeries involving 173 patients (124 females and 49 males, age 2–43 years, median 14 years) of whom 143 had one surgery, 27 had two and 3 had three. The etiologies in 190 scoliosis surgeries were idiopathic (109), congenital (37), neurofibromatosis (15), neuromuscular (13), horizontal gaze palsy and progressive scoliosis (HGPPS) (6) and other causes (10). The indications of 16 other surgeries were vertebral or pedicle tumor (7), spondylolisthesis (6), spinal fracture (2) or previous laminectomy requiring stabilization (1). Neurological pathology that could degrade SEPs or MEPs existed in 23 and 30 surgeries, respectively. This included cerebral palsy (1); Arnold–Chiari malformation (2); diastamatomyelia (4); tethered cord (2); spinal cord compression (6), tumor (5) or recent injury (2); spinal muscular atrophy (2); polio (1); Freidrich’s ataxia (1) and muscular dystrophy or myopathy (4). One patient had controlled epilepsy. The surgeon obtained informed consent for surgery with monitoring.

Pre-induction procedures

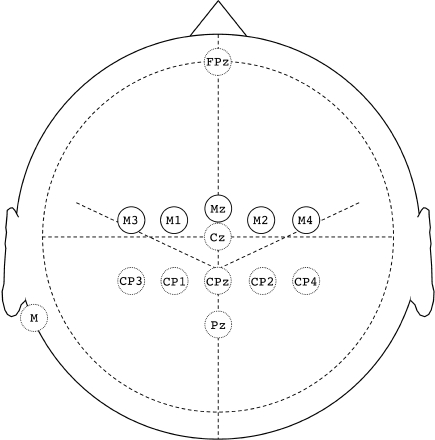

Surface electrodes applied with <2 kΩ impedance were collodion-fixed EEG cups on the scalp and adhesive ECG discs elsewhere. The pre-braided scalp SEP set was FPz, Cz, Pz, CP4, CP2, CPz, CP1, CP3, mastoid, and shoulder ground. The TES set was M2 and M1 for the first 105 surgeries and subsequently M4, M2, Mz, M1 and M3, where M (motor) sites were 1 cm anterior to 10–20 central sites (Fig. 1). Brachial (Br) and popliteal fossa (PF) peripheral SEP recording electrode pairs were placed longitudinally about 3 cm apart medial to the biceps tendon just above each elbow and just above the crease behind each knee. Median and tibial nerve stimulating electrodes were placed at each wrist and medial malleolus. The patient was then taken to the operating room for induction.

Fig. 1.

Scalp electrodes. Solid circles depict the transcranial electric stimulation set and broken circles designate the scalp SEP set

Anesthesia

Either total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) with propofol and opioid infusion (n = 119), or sevoflurane with or without nitrous oxide (n = 87) was used before patient positioning according to the anesthesiologist’s preference. TIVA was used after positioning and muscle relaxation was omitted after intubation. Anesthetic depth was adjusted to standard clinical parameters.

Post-induction procedures

First, tibial cortical SEP derivations were optimized to highest SNR as previously described [13, 18, 19]. The left tibial nerve procedure follows:

A referential recording of FPz, Cz, CPz, Pz, CP4, CP2, CP1 and CP3-mastoid and of right and left PF to confirm left stimulation was made and replicated. A bipolar recording of Cz-CP4, CPz-CP4, Pz-CP4, CP1-CP4, CP3-CP4, Cz-FPz, CPz-FPz, Pz-FPz, CP1-FPz, CP3-FPz and Cz-Pz comprising all possible optimal derivations for normal decussation was simultaneously made and replicated.

P37 and N37 scalp potentials were evaluated in the referential recording during acquisition. A predominantly ipsilateral scalp P37 field and usually contralateral N37 confirmed decussation; reversed lateralization identified non-decussation.

In the event of non-decussation, another recording using Cz-CP3, CPz-CP3, Pz-CP3, CP2-CP3, CP4-CP3, Cz-FPz, CPz-FPz, Pz-FPz, CP2-FPz, CP4-FPz and Cz-Pz derivations appropriate for an ipsilateral cortical source was made.

The bipolar derivation showing the best balance of high signal amplitude and low noise was selected for monitoring (Table 1). When occasionally an −FPz derivation produced highest amplitude, the analogous −CP4 (or −CP3 for non-decussation) derivation was selected instead if it had substantially lower noise evident by faster reproducibility despite slightly lower signal amplitude.

In practice, both sides were simultaneously assessed using mirror image bipolar derivations (Fig. 2). The recording took 5–10 min during pre-positioning anesthesiology tasks. When non-decussation was present, bilateral scalp recordings to right and then left median nerve stimulation were also made to confirm abnormally ipsilateral cortical N20 potentials.

Table 1.

Optimal tibial cortical SEP derivations (412 nerves)

| Input 1 (+ down) | Input 2 (− down) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPc | FPz | CPia | Pz | |

| Cz | 80 | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| CPz | 176 | 26 | 11 | – |

| Pz | 38 | 7 | – | – |

| ICPi | 42 | – | – | – |

| Cpi | 7 | – | – | – |

| Absentb | 13 | |||

CPc and CPi, CP4 or CP3 contralateral and ipsilateral to the stimulated nerve; iCPi, CP1 or CP2 intermediate centroparietal sites, ipsilateral

aNon-decussation

bDue to neurological pathology

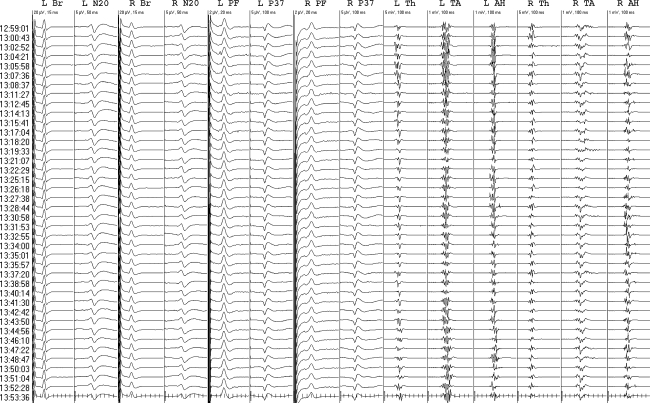

Fig. 2.

Tibial cortical SEP optimization. M mastoid; PF popliteal fossa. Referential recording showed P37 maxima at Cz for each nerve and confirmed sensory decussation by showing ipsilateral P37 fields and contralateral N37 potentials. Bipolar recording confirmed Cz-CP4 and Cz-CP3 optimal derivations. Note greater noise in −FPz derivations evident by lesser trace reproducibility

Next, bilateral median and tibial peripheral and optimized cortical SEPs were recorded and initial baselines set. Median cortical potentials were recorded with the highest SNR (most rapidly reproducible) derivation selected from CPc-FPz, CPc-CPz and CPc-CPi, where CPc and CPi were CP3 or CP4 contralateral and ipsilateral to the stimulated nerve. CPc and CPi were switched for non-decussation. Median and tibial stimuli were 5.1 and 4.7 Hz rectangular 0.2 ms pulses at supramaximal intensity for peripheral potentials. Peripheral and scalp recording bandwidths were 5–1,500 and 30–300 Hz.

Then unaveraged MEPs (bandwidth 20–1,500 Hz) were obtained from needle electrode pairs inserted about 3 cm apart in the thenar, tibialis anterior and abductor hallucis muscle bellies. A standard Nicolet intraoperative stimulator was used for TES (Nicolet Biomedical Instruments, Madison, WI, USA). Constant-voltage 0.5 ms duration pulses were selected. Train parameters were usually five pulses with a 4 ms inter-pulse interval. One or more rapidly administered preconditioning trains immediately preceding the test stimulus were typically used for facilitation. Voltage (150–400, median 300) and pulse number (3–9, median 5) were adjusted to produce clear supra-threshold MEPs.

Because of preferential sub-anodal brain activation, left and then right MEPs were recorded to M2-M1 (anode-cathode) and then M1-M2 interhemispheric stimuli until we discovered non-decussation in the 105th surgery. Subsequent MEPs began with bilateral recordings to M3-Mz and then M4-Mz hemispheric stimulation to assess decussation; predominantly contralateral responses confirmed motor decussation, whereas ipsilateral potentials identified non-decussation. Occasionally, M3/4-Mz was used for monitoring, but normally M1/2 or if necessary, M3/4 was used instead. After deciding on technique, left and then right MEPs to right and then left anodal stimulation (or the reverse for non-decussation) were recorded and initial baselines set.

Monitoring

Sequential sets of all potentials were acquired as rapidly as permitted by averaging time to SEP reproducibility, defined as nearly exact trace superimposition and less than about 20–30% trial-to-trial amplitude variation [19]. Averaging was interrupted during electrosurgery until EEG traces from scalp SEP derivations showed amplifier recovery. Baselines were reset after substantial systemic changes.

The monitoring template was designed to simultaneously display current SEPs with automatic latency/amplitude measurement and baselines, current MEPs and baselines, stacked waveforms including comments and times, and EEG (Fig. 3). MEPs were unmeasured because peak variability produced inaccurate automatic measurements and manual tagging was time consuming. Baselines were used to visualize reproducibility and change, but percentage change was not a criterion per se. Stacked waveforms were used to visualize changes over time. EEG was used to assess raw scalp SEP input, the anesthesia pattern and to look for post-TES seizure patterns. Quadriceps, gastrocnemius and occasionally sphincter MEPs as well as EMG and pedicle screw stimulation were sometimes added.

Fig. 3.

Monitoring template. Br brachial, PF popliteal fossa, Th thenar, TA tibialis anterior, AH abductor hallucis. Optimal cortical SEP derivations were left median (LN20), CP4-CPz right median (RN20), CP3-CPz left tibial (LP37), Cz-CP4 and right tibial (RP37), CP2-CP3. Green traces are the most recent baselines. The median interval between evoked potential sets was 60 s

Peripheral SEP and thenar MEP preservation demonstrated stimulation and their loss led to a search for stimulus failure. Generalized changes were considered systemic and defined as approximately parallel four-limb amplitude or latency trends. Focal decrements were considered pathological and prompted intervention: amplitude decrement unequivocally exceeding trial-to-trial variation was sufficient for SEPs, but due to more substantial variability, unequivocal MEP decrement required disappearance of a response that had been consistently present. Inconsistent MEPs from the beginning were considered unmonitorable and their loss did not prompt an alarm.

Gradual change was defined as occurring over many minutes or hours. Abrupt change was defined as occurring within seconds or a few minutes, i.e. appearing in the next set or over 2–3 sets. Focal decrements were classified as transient when quickly resolved or protracted when they persisted to closure or for more than 40 min. Hypotension was defined as mean arterial pressure below 60 mmHg. The surgeon determined whether TES patient twitch interfered with surgery and assessed patient outcome, supplemented by neurological consultation for apparent deficits.

Results

Monitorability

Brachial, PF and median cortical SEPs were always monitorable. Tibial cortical SEP monitorability was 96.8% (399 of 412 tested nerves). All instances of absence were due to central sensory pathway pathology. Spinal cord tumor, compression or trauma and Freidrich’s ataxia caused bilateral absence in six surgeries and Arnold-Chiari malformation caused unilateral absence in one.

Thenar MEPs were always monitorable. Leg MEP monitorability was 97.8% (405 of 412 tested limbs). There were two instances of unilateral absence in neurologically intact patients monitored with M3/4-Mz or M1/2 stimulation. M3/4 appeared most efficient for evoking leg MEPs (Fig. 4) and never failed in neurologically intact patients. In one surgery it produced leg MEPs while M1/2 did not and in another it restored leg MEPs that had faded out to M3/4-Mz stimulation. All other instances of absence were due to central motor pathology. Freidrich’s ataxia or recent cord injury with paraparesis caused bilateral absence in three surgeries and polio caused unilateral absence in one.

Fig. 4.

Transcranial electric stimulation. M3/4-Mz (anode–cathode) stimuli produced anode-contralateral muscle potentials confirming normal decussation. M1/M2 and M3/M4 produced larger and bilateral leg muscle potentials maximal opposite the anode. M3/M4 was most efficient. Nicolet stimulator, 300 V, five 0.5 ms duration pulses, 4 ms inter-pulse interval

Monitorability for at least one leg modality was 99.0%. Bilateral absence of both modalities occurred in one patient with recent transverse thoracic cord injury and another with Freidrich’s ataxia.

Decussation assessment

Sensorimotor non-decussation existed in six surgeries (2.9%) on four HGPPS patients (one patient had three surgeries). Since non-decussation had been unknown in this disorder, the first was discovered unexpectedly during SEP optimization. It was then anticipated by horizontal gaze palsy in two patients, but in another subtle gaze palsy went unnoticed and decussation screening made the diagnosis. Accurate optimal monitoring required ipsilateral SEP and MEP montages.

Rapidity

Peripheral SEPs were almost always visible in single sweeps and required minimal averaging. Optimized cortical potentials normally reproduced within 50–250 sweeps (about 10–50 s when there were no rejections and electrosurgery was not in use). Infrequently, more sweeps were needed when cortical SEP amplitude was unusually small or EEG noise was high, which was typical of young children. Muscle MEPs took only seconds. Device operation and comment entry took some time. The interval between complete-evoked potential sets was 1–3 min in the great majority of surgeries (Fig. 5).

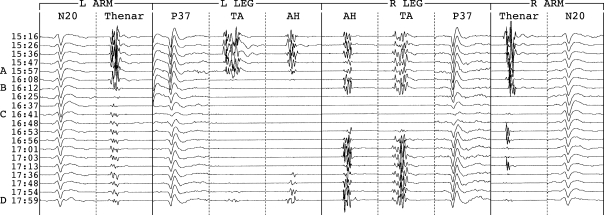

Fig. 5.

Typical rapidity and reproducibility. Br brachial, N20 optimized median cortical (CPc–FPz), PF popliteal fossa, P37 optimized tibial cortical (left CPz-CP4, right CP2-CP3); Th thenar, TA tibialis anterior, AH abductor hallucis. The median inter-set interval was 76 s without compromising SEP reproducibility

Technical control

Electrode disconnection, elevated impedance or software malfunction caused eight stimulus failures immediately detected by peripheral SEP loss or by simultaneous thenar and leg MEP loss. Each was quickly corrected without alarm. Peripheral SEP and thenar MEP preservation effectively excluded stimulus failure.

Systemic control

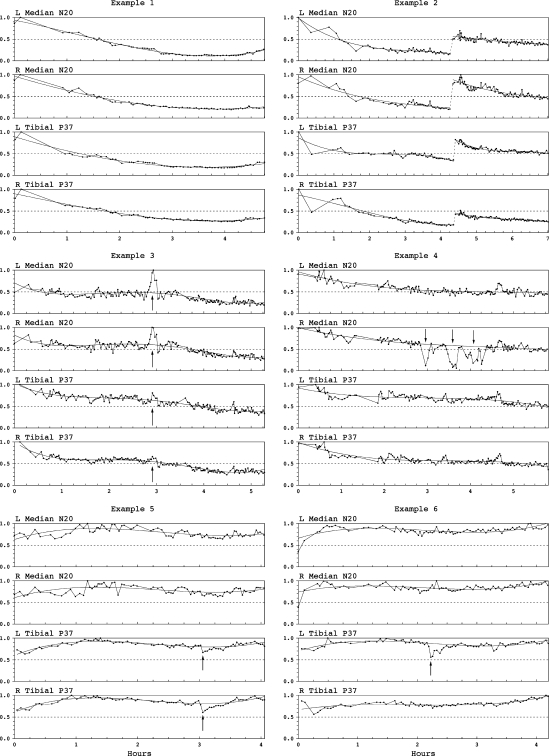

Systemic alterations occurred in virtually all surgeries and were gradual unless anesthesia changed abruptly. They were readily identified by generalized patterns. Latencies varied inversely with patient temperature. Cortical SEP amplitudes showed rising or falling trends that varied in magnitude and direction. This often correlated with anesthesia: amplitudes usually rose after switching from sevoflurane to TIVA and tended to vary inversely with infusion rates. However, unexplained cortical SEP fading despite stable infusion was a common pattern (Fig. 6). Potential fade exceeded 50% (as much as 80%) in 10% of the first 33 surgeries and our subsequent experience concurred.

Fig. 6.

Cortical SEP systemic patterns and focal decrements. N20 median cortical SEP, P37 tibial cortical SEP. Plotted amplitudes are normalized to maximum observed values (=1.0). Example 1 Generalized potential fade. Example 2 Generalized potential fade, then abrupt increase after correcting elevated scalp electrode impedances, then further fade. Example 3 Generalized potential fade reaching stability, then transient increase due to propofol infusion failure and then further fade. Example 4 Generalized potential fade punctuated by abrupt right median SEP decrements, each restored after correcting extreme shoulder position (suspected transient brachial plexus compromise, no deficit). Example 5 Generalized rising–falling–rising pattern punctuated by bilateral 20–30% tibial SEP decrements that resolved spontaneously. There was bilateral leg dysesthesia (suspected dorsal column contusion). Example 6 Generalized rising-falling-rising pattern punctuated by left tibial 40% SEP decrement that followed thoracic hook placement and resolved after hook removal without injury

Systemic MEP changes tended to shadow SEP trends. Potential fade was again common, threatened disappearance if stimulation was not increased and tended to affect leg more than thenar potentials. Consequently, stimulus increments to maintain leg muscle potentials were made in 82 surgeries (40%). These consisted of a 25–250 V increase in 30, a 1–4 pulse number increase in 31, and of both in 21. Increments normally restored fading amplitudes, but occasionally maintained only presence with substantially smaller closing amplitudes.

When generalized change was the only SEP pattern there was no intraoperative dorsal column injury and when it was the only MEP pattern there was no intraoperative spinal cord motor injury.

Focal decrements

One or more focal decrements occurred in 21 surgeries (Table 2). They were readily distinguished from generalized patterns by visual analysis without quantification. There were 16 transient decrements; 15 resolved after intervention and one spontaneously. There were five protracted decrements of at least one potential despite intervention.

Table 2.

Focal decrements and injuries

| Decrement | Intervention | Decrement response | Injury |

|---|---|---|---|

| R arm SEP > MEP | Reposition shoulder | Transient | – |

| L arm SEP > MEP | Release shoulder strap | Transient | – |

| L arm SEP > MEP | Reposition shoulder | Transient | – |

| L arm SEP > MEP | Relieve forearm pressure | Transient | – |

| R arm SEP > MEP | Relieve mid-humeral pressure | Transient | Radial nerve palsy |

| R arm SEP | Relieve forearm pressure | Transient | – |

| B leg MEP | Straighten patient; restore BP | Transient | – |

| B leg MEP | Restore BP | Transient | – |

| B leg MEP | Remove hook | Transient | – |

| B leg MEP | Release rods (4 times) | Transient | – |

| B leg MEP | Pause surgery, raise BP | Protracted R TA MEP | Delayed paraparesis |

| R leg MEP | Correct acute kyphosis | Protracted R leg MEP | R leg paresis |

| B leg MEP > SEP | Release rods | Transient | – |

| B leg MEP > SEP | Restore BP, remove hook (twice) | Transient | – |

| B leg MEP > SEP | Remove wire | Transient | – |

| B leg/arm MEP > leg SEP | Raise BP, remove hook (delayed) | Protracted L leg MEP | L leg paresis |

| B leg MEP + SEP | Remove hook | Protracted R MEP + SEP | R Brown–Sequard |

| L leg MEP + SEP | Restore BP | Transient | – |

| B leg MEP + SEP (incl. PF) | Relieve femoral artery pressure | Protracted R TA MEP | R L5 radiculopathy |

| B leg SEP (20–30%) | – | Transient (spontaneous) | B leg dysesthesia |

| L leg SEP (40%) | Remove hook | Transient | – |

| – | – | – | L4 radiculopathy |

| – | – | – | L5 radiculopathy |

| – | – | – | Delayed paraparesis |

Transient decrements resolved quickly after intervention. Protracted decrements persisted to closure or for more than 40 min. Injuries were temporary except the two unpredicted radiculopathies

R right, L left, B bilateral, > before, MEP cortico-muscle motor-evoked potential, SEP cortical somatosensory-evoked potential, BP blood pressure, TA tibialis anterior; PF popliteal fossa

Focal arm decrements

Transient unilateral arm decrements occurred in six surgeries (2.9%) and suggested arm neural injury prevention in five (2.4%). They were abrupt in 5 and evolved over 20 min in one. Five were manifest by cortical SEP decrement before MEP loss and one by SEP decrement only. Full restoration followed extreme shoulder position correction in three (Fig. 6, Example 4) and arm pressure relief in three. Two due to forearm pressure also produced Br potential loss. Temporary radial nerve palsy followed one caused by mid-humeral pressure.

Focal leg decrements

At least one unilateral or bilateral focal leg decrement occurred in 15 surgeries (7.3%). Five were protracted and predicted temporary neurological injury. Ten were transient and nine of these suggested spinal cord injury prevention (4.4%). All were abrupt. Next-set MEP disappearance was typical, but marked amplitude reduction sometimes immediately preceded total loss. Decrements were MEP-only in six, MEP 2–17 min before SEP in four, simultaneous in three and SEP-only in two; congruent decrements increased interpretive confidence.

Leg MEP-only decrements

The first of these consisted of bilateral leg MEP disappearance after discectomy without hypotension during idiopathic scoliosis anterior release. The patient was in marked lateral flexion. Potentials reappeared after straightening the patient, but later disappeared again with hypotension. Blood pressure normalized and MEPs returned after relieving inadvertent inferior vena cava pressure. There was no injury.

The second consisted of bilateral leg MEP disappearance with hypotension during anterior release for idiopathic scoliosis. Potentials reappeared after blood pressure restoration and there was no injury.

The third consisted of bilateral leg MEP disappearance following thoracic hook placement without hypotension in an idiopathic scoliosis patient. Potentials returned after hook removal. Satisfactory curve correction omitting this hook produced no further decrement or injury.

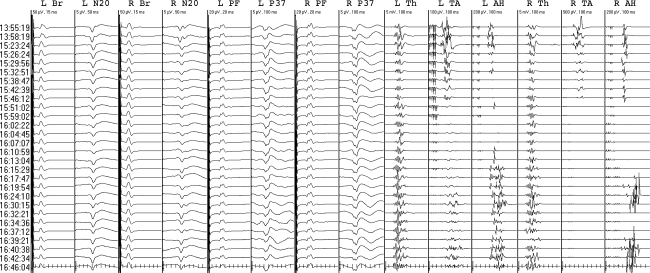

The fourth consisted of repeated bilateral leg MEP disappearances without hypotension while attempting progressively smaller curve corrections for idiopathic scoliosis (Fig. 7). Potentials returned after rod release each time. Spinal fusion in situ produced no further decrement or injury.

Fig. 7.

Transient leg MEP-only decrements in a 9-year-old idiopathic scoliosis patient. Br brachial, N20 optimized median cortical (CPc-FPz), PF tibial popliteal fossa, P37 optimized tibial cortical (left CP3-CP4; right Cz-Pz); Th thenar, TA tibialis anterior, AH abductor hallucis. The median interval between evoked potential sets was 2.0 min. High amplitude EEG typical of young children reduced signal-to-noise ratios and lesser SEP reproducibility had to be accepted. Each progressively smaller curve correction (asterisk) produced leg MEP-only decrements (exclamatory symbol) that resolved after rod release. There was no injury

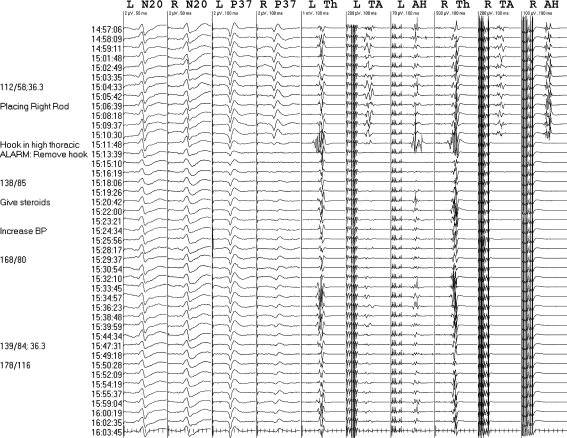

The fifth involved a neurofibromatosis scoliosis patient with rib head migration into the spinal canal causing cord compression (Fig. 8). There was fleeting left abductor hallucis MEP loss and then bilateral Leg MEP disappearance during rib head resection without hypotension. After pausing surgery and raising blood pressure potentials reappeared except for protracted right tibialis anterior MEP absence through to closure. The right abductor hallucis MEP again transiently disappeared on resuming surgery, reappearing after raising blood pressure. We gave dexamethasone and deferred instrumentation. No initial deficit was identified on cursory exam, but paraparesis developed within hours. Leg strength was 3/5 at successful spinal fusion three days later; tibial SEPs were intact but leg MEPs were unmonitorable. Clinical recovery ensued over several weeks.

Fig. 8.

Protracted leg MEP decrement. Br brachial, N20 optimized median cortical (CPc-FPz), PF popliteal fossa, P37 optimized tibial cortical (CPz–CPc), Th thenar, TA tibialis anterior, AH abductor hallucis. The first two evoked potential sets are from the beginning of surgery and the subsequent sets were obtained during intra-canal rib head resection. The median inter-set interval was 2.9 min due to frequent electrosurgery. Bilateral leg MEP decrements mostly resolved after pausing surgery and raising blood pressure, except for protracted right TA MEP absence. No initial weakness was identified but paraparesis developed within 1 day

The sixth involved a patient with T10/11 vertebral tumor, cord compression and paraparesis. There was protracted right leg MEP disappearance without hypotension after vertebrectomy caused acute kyphosis. Raising blood pressure had no effect. Partial reappearance after more than 1 h followed urgent kyphosis correction. Worsened right leg paresis rapidly resolved to preoperative strength.

Leg MEP before SEP decrements

The first of these consisted of bilateral leg MEP disappearance and then SEP reduction 4 min later during derotation without hypotension in a neurofibromatosis patient. Potentials returned after rod release. Satisfactory curve correction using distraction proceeded without further decrement or injury.

The second consisted of bilateral leg MEP disappearance 2–3 min before bilateral SEP reduction after thoracic hook placement during hypotension in an idiopathic scoliosis patient. Potentials returned after hook removal and raising blood pressure. Another transient bilateral leg MEP and then right SEP decrement occurred on briefly replacing and then removing the hook without hypotension. Satisfactory curve correction omitting this hook proceeded without further decrement or injury.

The third consisted of bilateral leg MEP loss 5 min before SEP decrement following thoracic sublaminar wiring without hypotension in an idiopathic scoliosis patient. Potentials returned after wire removal. Satisfactory curve correction omitting this wire produced no further decrement or injury.

The fourth began with left leg MEP disappearance after left T1 hook placement without hypotension in an HGPPS patient (Fig. 9). This progressed to generalized MEP loss and eventually bilateral leg SEP reduction 17 min later while waiting to see the effect of raising blood pressure. After finally removing the hook, potentials returned except for protracted left leg MEP absence. We gave dexamethasone and deferred instrumentation. Small left leg MEPs reappeared after 1.5 h. Grade 4/5 left leg paresis resolved in a few days. At satisfactory curve correction omitting the T1 hook one week later MEPs were large and there was no decrement or injury.

Fig. 9.

Protracted leg MEP decrement. N20 median cortical SEP, P37 tibial cortical SEP. The patient had horizontal gaze palsy and progressive scoliosis with sensorimotor non-decussation requiring ipsilateral montages: CPi-FPz for median SEPs, CPz-CPi for tibial SEPs, M1–M2 stimulation for left MEPs and M2–M1 for right MEPs. Traces are selected from the intraoperative record that had greater time resolution. A Left T1 hook. B Left leg, then generalized MEP and finally bilateral leg SEP decrements despite raising blood pressure. C Hook removal followed by potential restoration except for protracted left leg MEP absence. D Late left leg MEP reappearance. Mild left leg paresis resolved in a few days

Simultaneous leg MEP and SEP decrements

The first of these consisted of right leg MEP and SEP decrement immediately following right thoracic hook placement without hypotension in an idiopathic scoliosis patient (Fig. 10). The next set showed bilateral leg decrements. After hook removal left leg potentials returned, but protracted right leg MEP and SEP decrement persisted to closure. Raising blood pressure had no positive effect. We suspected cord contusion and proceeded with moderate deformity correction after giving dexamethasone. Right Brown–Sequard injury resolved in a few days.

Fig. 10.

Protracted right leg MEP and SEP decrement. N20 optimized median cortical SEP (CPc-FPz), P37 optimized tibial cortical SEP (left Cz-CP4, right CPz-CP3), Th thenar, TA tibialis anterior, AH abductor hallucis. The median inter-set interval was 79 s. Initially right, then bilateral leg MEP and SEP decrements immediately followed right T1 hook placement. The decrement resolved on the left after hook removal but persisted on the right, predicting right Brown–Sequard injury (suspected spinal cord contusion)

The second consisted of left leg MEP and SEP decrement during hypotension and spinal cord exposure in a patient with T8/9 vertebral tumor. Potentials returned after restoring blood pressure and there was no injury.

The third occurred during right L5 pedicle tumor surgery. After a 30-min monitoring pause during electrosurgery for opening, all leg potentials including PF potentials were absent. We suspected leg ischemia due to femoral artery pressure and repositioned the pelvic support. Potentials gradually returned over 20–30 min except for protracted right tibialis anterior MEP absence through to closure; there were no EMG discharges. There was a right L5 radiculopathy with subsequent recovery.

Leg SEP-only decrements

The first of these consisted of bilateral 20–30% SEP reduction during instrumentation for idiopathic scoliosis (Fig. 6, Example 5). There was spontaneous restoration but marked bilateral leg dysesthesia lasting several days. The second consisted of left tibial SEP 40% reduction after left thoracic hook placement without hypotension in an idiopathic scoliosis patient (Fig. 6, Example 6). Restoration followed hook removal and satisfactory curve correction omitting this hook proceeded without further decrement or injury.

Unpredicted injuries

Two scoliosis patients with no focal decrements suffered permanent L4 or L5 radiculopathy. Neither had EMG or pedicle screw testing. One congenital scoliosis patient with cord compression and absent tibial SEPs but monitorable leg MEPs showing no decrement suffered day 1 delayed paraparesis that clinically resolved over several weeks.

Sensitivity and specificity

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of protracted, transient or either type of focal decrements are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sensitivity and specificity for any injury

| Type of focal decrement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Protracted | Transient | Either | |

| Sensitivity | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.70 |

| Specificity | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| Positive predictive value | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.33 |

| Negative predictive value | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.98 |

Impact on surgery and safety

Monitoring prompted modified instrumentation but satisfactory curve correction in four surgeries (1.9%), modified curve correction in three (1.5%), deferral to a successful second surgery in two (1.0%) and no modification in 197 (95.6%). The surgeon found that TES patient twitch did not interfere with surgery. No EEG or clinical seizures occurred, including the patient with controlled epilepsy. One tongue bite with M3/4 TES healed spontaneously.

Discussion

Monitorability

The high monitorability we achieved supports TIVA [8, 9, 16, 26, 27, 32] and confirms that standard Nicolet stimulators are effective for TES. While M3/4-Mz is useful for decussation assessment [17], it should not be used for leg monitoring. M3/4 appears to be most efficient for leg MEPs, possibly due to less current shunting between the widely spaced electrodes [6, 20] and is necessary for some patients. At the same time, it tends to produce strong patient twitch and may increase the chance of bite injuries owing to closer stimulating electrode proximity to the temporalis muscles and trigeminal nerves [20, 22]. When effective for leg MEPs, M1/2 tends to produce milder twitch and might reduce the chance of bite injury. In practice, the M4, M2, Mz, M1, M3 array was useful to assess motor decussation and maximize monitorability and safety.

Neurologically intact patients are fully monitorable with these techniques, but neurologically diseased patients sometimes have unilateral or bilateral pathologic absence of one or both leg modalities. The overall 99.0% leg monitorability for at least one modality emphasizes the value of their combination. Notably, the only two patients with bilateral absence of both had severe myelopathy due to Freidrich’s ataxia or recent thoracic cord damage.

Decussation

Non-decussation will cause suboptimal inaccurate monitoring if standard methods that assume normal decussation are used [17]. Furthermore, it is not that rare since we found it in six surgeries (2.9%) on four HGPPS patients. This autosomal recessive disorder is likely more frequent at our hospital in Saudi Arabia where consanguinity is common, but has also been reported in Japan, Europe and North America and the gaze palsy may go unnoticed [2, 17]. Non-decussation also occurs in some other rare disorders [17]. Simply recording bilaterally to unilateral stimulation assesses decussation and is inherent to SEP optimization and M3/4-Mz MEP screening. Sensorimotor decussation should not be assumed.

Rapidity

Rapid feedback provides timely surgical correlation and should increase the likelihood of successful intervention. Muscle MEPs can provide instantaneous feedback, but their acquisition is interrupted by SEPs that require averaging. Consequently, rapid feedback depends on SEP methods because averaging time decreases dramatically as SNR increases [19]. Since even modest SNR gains substantially speed acquisition, one should maximize SNR by optimally balancing high signal amplitude and low noise [19]. Anesthetic choice and derivation selection achieve this.

Propofol and opioid infusion produces larger cortical SEP signal amplitude than inhalational anesthesia and should therefore be preferred [8, 9, 18, 32]. This choice also enhances muscle MEP monitorability [16, 20, 26, 27].

Routine laboratory derivations are inappropriate for intraoperative monitoring. In the laboratory, derivations are standardized for valid normative control comparison, latency is more important than amplitude and SNR is not critical because there is ample averaging time. In the operating room, derivations needn’t be standardized because patients serve as their own controls, amplitude change is more important than latency and SNR is critical to feedback rapidity [19].

Signal amplitude depends on Input 1 picking up the maximum surface potential and Input 2 picking up a concurrent opposite-polarity potential to boost amplitude, or at least being inactive to avoid in-phase signal cancellation. Noise consists of electrical interference, EMG, ECG, and EEG [19]. Short inter-electrode distance, tight lead braiding and low impedance minimize electrical interference. Adequate anesthesia and analgesia eliminates EMG. Omitting scalp-noncephalic and Erb’s point derivations eliminates ECG. Avoiding FPz and Fz minimizes EEG noise characterized by frontal-dominant anesthetic fast activity [19]. Burst-suppression or suppression markedly accelerates cortical SEP reproducibility by almost eliminating EEG noise; we have not intentionally titrated anesthesia to these patterns, but welcome their occurrence [19].

Peripheral and median cortical SEPs are easily optimized. Brachial and standard PF potentials have high SNRs and reproduce quickly [19]; Erb’s point having lower SNR is omitted. The median cortical SEP Input 1 is normally CPc to pick up the negative N20 potential, but must be CPi for non-decussation [17]. FPz is sometimes a satisfactory Input 2 because it contains the frontal positive P22 that boosts signal amplitude. However, CPc-CPz or CPc-CPi (CPi-CPz or CPi-CPc for non-decussation) often show faster reproducibility due to due to substantially less EEG noise, producing higher SNR despite slightly lower signal amplitude. The CPc-CPz (or CPi-CPz) derivation’s short inter-electrode distance can further reduce noise, but N20 field spread to CPz may diminish signal amplitude through in-phase cancellation; when this does not occur, it is often optimal. Simple comparison determines the best derivation.

Marked topographic variability between individuals and sides makes tibial cortical SEP optimization more complex [13, 18, 19]. Input 1 should be the P37 maximum that is commonly at CPz, but may be at Cz, Pz, iCPi or CPi (iCPi being the intermediate CP1 or CP2 site ipsilateral to the stimulated nerve). With non-decussation it could even be at iCPc or CPc. Input 2 should be the N37 that is normally located at CPc, but may be at CPi with non-decussation or ectopic at Pz when the P37 maximum is at Cz. Even when an FPz Input 2 produces greatest signal amplitude, using CPc (or CPi with non-decussation) for Input 2 often produces faster reproducibility due to substantially lower EEG noise and therefore higher SNR despite slightly lower signal amplitude [19]. Consequently, optimal derivations infrequently include FPz and never Fz that also contains anterior spread of the P37 causing in-phase signal cancellation [13].

Superior results justify the minimal extra effort of tibial SEP optimization: optimized derivations have a mean 2.1:1 SNR advantage over the standard CPz-FPz and the arithmetic of averaging translates this to a fourfold reduction of the median sweep number needed for reproducibility (128 vs. 512 sweeps) [19]. Some other recommended derivations such as CPi-FPz, iCPi-FPz and CPi-CPc [1, 33] are actually rarely or never optimal (Table 1). If one insists on a routine derivation for convenience, then CPz-CPc is the best choice, but will still be suboptimal for many patients and non-decussation would require CPz-CPi instead.

The tibial subcortical P31 from FPz-C5S is often recommended [1, 33], but due to very low mean SNR requires a median of 1,000 sweeps for reproducibility; about 24% require more and 7% are not practically reproducible [19]. Despite is lesser sensitivity to inhalational anesthesia [25, 36] this slow inconsistent potential should normally be omitted [19].

Spinal cord ischemia is an important injury mechanism during spine surgery. It typically causes muscle MEP loss within 2 min and infarction could begin within ten, possibly leaving a narrow window for effective remedial action [21]. Therefore, the 1–3 min feedback intervals were appropriate and validated by observed abrupt next-set focal leg decrements. SEP optimization provided these intervals without compromising reproducibility that is fundamental for valid interpretation. Either lesser reproducibility risking misleading results or intervention delays would have occurred with traditional techniques.

Rapid feedback often implicated the most recent surgical maneuver as the likely cause of focal decrement. Potential restoration usually followed undoing this maneuver and whenever possible this should be done before waiting to see the effect of raising blood pressure unless hypotension appears to be the likely cause. Temporarily interrupting SEP acquisition could allow extremely rapid muscle MEP feedback, but we did not find this to be necessary.

Technical control

The results confirm that peripheral SEPs and thenar MEPs are effective technical controls [1, 14, 16, 19, 21, 33]. Their preservation immediately excludes and their loss immediately suggests stimulus failure that was so identified and corrected in eight instances without alarm. Peripheral SEP loss also detects distal conduction block due to limb ischemia or pressure as a cause for focal decrement that was so identified in four surgeries [14, 21, 35]. Correcting these disturbances might even help prevent distal nerve injury. One must also consider cerebral or cervical cord compromise as causes for simultaneous thenar and leg MEP loss, but thoracolumbar cord disturbance is excluded by this pattern.

Systemic control

The results emphasize that generalized systemic changes are frequent, benign and commonly include gradual potential fade despite stable anesthesia. Also, they can exceed 50% cortical SEP amplitude reduction or threaten muscle MEP loss if stimulus increments are not made [12, 14, 16, 20]. Potential fade varies considerably from little or none to marked and is exacerbated by antecedent myelopathy [12]. This unpredictable evolving neurophysiologic state opposes percentage of baseline or threshold criteria that incorrectly assume stability.

Invasive epidural or subarachnoid spinal recordings make quantitative criteria more logical because they are resistant to anesthesia [7, 20]. However, these pure white matter potentials can miss or delay the detection of ischemia that begins in and may be limited to anterior horn gray matter [21]. Furthermore, epidural recordings may be altered by curve correction itself: thoracic epidural D wave MEP amplitude can decrease or increase by up to 75% after spine straightening without muscle MEP alteration or correlation to outcome [34]. This might be due to increased or decreased distance between the epidural electrode and the spinal cord as its position shifts within the newly straightened spinal canal. Subarachnoid recordings might not be subject to this problem.

Because invasive electrodes have a small risk of hemorrhagic, traumatic or infectious complications their use should be justified or deferred to non-invasive methods when sufficient [15, 20, 22]. Intramedullary spinal cord tumor surgery is one instance in which non-invasive techniques alone are insufficient, justifying invasive D wave monitoring as an essential addition [5, 20]. However, our results suggest that non-invasive monitoring is sufficient for other spine surgery [20]. This is not to exclude invasive techniques that can be complimentary. Nevertheless, they will likely remain limited to a few centers while non-invasive recordings will remain common and essential because they are not altered by a change of spinal cord position and because of greater muscle MEP sensitivity to cord ischemia [20, 21].

Therefore, systemic alterations must be identified and the results confirm that generalized change is a reliable indicator when surgery threatens the thoracolumbar cord so that arm potentials are valid controls [1, 14, 16, 19, 20, 21, 24, 31]. When the cervical cord is at risk one must emphasize the time course that is normally gradual for systemic and abrupt for pathologic change. Indeed, we encountered one example of generalized MEP loss due to lower cervical cord compromise. However, the abrupt onset and initially focal left leg MEP loss clearly distinguished this event from a systemic cause. Large anesthetic boluses or inadvertent administration or potentiation of neuromuscular blockade that can cause rapid generalized decrements should be avoided to prevent confusion.

We found that potential fade tends to reduce leg MEPs somewhat more than thenar responses that are therefore not ideal systemic controls. Consequently, we have adopted the strategy of stimulus increments to maintain leg potentials. The up to 250 V or four pulse increments made in 40% of surgeries were never by themselves associated with intraoperative spinal cord motor injury, nor were reduced but consistently present MEPs. This supports the idea that ongoing muscle MEP presence indicates spinal cord corticospinal system integrity while amplitudes and stimulus requirements may fluctuate [5, 20]. They conflict with threshold [3], morphology [29] or proposed amplitude reduction criteria that range from 50 to 80% and currently remain controversial [20].

Focal-evoked potential decrements

In the context of generalized systemic patterns, focal decrements are visually obvious and do not need quantification. The limb and modality congruent deficits predicted by protracted focal decrements in five surgeries establish their pathologic significance. This supports the conclusion that transient decrements without injury signified neural injury prevention in the arms (2.4%) or spinal cord (4.4%). However, we acknowledge that some focal decrements might spontaneously resolve without intervention or injury. Therefore, only historical control studies or large surveys similar to those previously undertaken for SEP monitoring [4, 23] could prove this contention.

Focal arm decrements

Of the six one-arm decrements, SEPs were more sensitive than MEPs, supporting their continued use. The one temporary radial nerve injury was not directly predictable by restored median SEPs and thenar MEPs, but there might have been more extensive injury had not the mid-humeral pressure been relieved as prompted by monitoring. Adding brachioradialis and hypothenar MEPs for the radial and ulnar nerves might be useful if channels are available. The findings suggest that brachial plexus or arm peripheral nerve compromise occurs commonly enough during spine surgeries and support the conclusion that upper limb monitoring offers protection [16, 24, 30].

Focal leg decrements

Of the 15 leg decrements, MEPs were more sensitive than SEPs, suggesting that muscle MEP monitoring should further reduce paraplegia risk [3, 16, 20, 28]. The last one consisting of loss of all leg potentials including peripheral SEPs was unique and suggested leg ischemia [35]. The restoration after pelvic support repositioning intended to relieve suspected femoral artery pressure supports this interpretation. Protracted right tibialis anterior MEP loss correlated with L5 radiculopathy, suggesting that by the time other leg potentials returned there had already been a root injury due to the pedicle surgery and that these injuries may sometimes be detected by muscle MEPs. Interestingly, there were no EMG discharges.

The other 14 suggested spinal cord compromise. The six MEP-only and four MEP before SEP decrements suggest anterior cord disturbances sometimes becoming transverse and their striking similarity to aortic surgery-evoked potential decrements suggests ischemia [14, 21], although compression might cause the same patterns. Both could be reversible if detected quickly.

The temporary Brown–Sequard injury predicted by protracted right leg MEP/SEP decrement immediately following the placement of a hook and despite its removal suggests contusion. While not reversible, contusion might be minimized through rapid detection and correction of the cause. The occurrence of this and other unilateral or asymmetric decrements and injuries confirms the importance of monitoring each side separately.

Although SEPs were less sensitive overall, the increased interpretive confidence afforded by congruent decrements and the two SEP-only decrements support their continued use. One SEP-only decrement resolved after hook removal exactly like several other focal decrements. Leg dysesthesia following the other suggests that it had pathologic significance despite its spontaneous resolution; dorsal column contusion is a possible explanation. That neither of these exceeded 50% again opposes percentage criteria. The issue is whether the decrement clearly exceeds trial-to-trial variation. One should also keep in mind that SEP decrements tend to underestimate dorsal column conduction block because of central amplification, while muscle MEP decrements tend to overestimate motor system compromise due to high sensitivity [20].

It is of interest that only two focal leg decrements implicated curve correction as the cause. Instead, most implicated thoracic hook or wire placement, hypotension, vertebrectomy, discectomy or intra-canal rib head resection, indicating that these are more frequently risky.

Unpredicted injuries

The three unpredicted injuries show that radiculopathy and delayed paraparesis can evade detection. Due to overlapping muscle innervation and inherent muscle MEP variability, there may be no definite MEP decrement despite the loss of one motor root [20]. Sometimes, a step-like reduction can be seen, but may not exceed any warning criteria [20]. Perhaps, we might have identified or avoided the two radiculopathies with EMG or pedicle screw testing [10]. However, EMG discharges that suggest irritation do not necessarily indicate injury, nor as we have seen does their absence exclude it. In addition, pedicle screw stimulation can detect pedicle breach, but provides no functional assessment. In our view, root protection remains an incompletely resolved problem and we have chosen to emphasize spinal cord assessment.

The one unpredicted delayed paraparesis is readily explained by its onset after monitoring had stopped. There will likely remain an irreducible incidence of this complication. Since both instances of delayed paraparesis (one unanticipated) occurred with preoperative cord compression, particularly diligent postoperative management may be indicated for these patients.

Sensitivity and specificity

Classical test-condition analysis fits intraoperative monitoring poorly because intervention based on a positive test (decrement) reduces the likelihood of the condition (post-operative deficit). Furthermore, there is no independent means to confirm or refute transient positive results when they occur. Consequently, some transient focal decrements without injury are incorrectly classified ‘false positive’ [23]. Therefore, transient and protracted focal decrements should be analyzed separately. We chose 40 min or persistence to closure to define protracted decrements based on aortic surgery monitoring experience [21]. Note that delayed paraparesis, radiculopathy and untested peripheral nerve injuries that have inherently low intraoperative predictability are difficult to analyze.

With these caveats in mind, test-condition analysis showed overall 70% sensitivity and 93% specificity for either type of focal decrement. However, protracted focal decrements had no false positives and therefore 100% specificity and positive predictive value, whereas transient focal decrements logically had significantly lower 13% positive predictive value (Chi square, P < 0.01). On the other hand, protracted focal decrements had only 50% sensitivity because they did not predict the one radial nerve and one dorsal column injury that were anticipated by transient decrements, nor the three understandably unpredicted injuries. Nevertheless, all three intraoperative spinal cord injuries, one radiculopathy and one delayed paraparesis were anticipated by protracted focal leg MEP decrements and four of these would have gone undetected by SEP monitoring alone.

Impact on surgery and safety

No undue alteration of surgery occurred. This is important because false warnings signify a failure of essential performance that can interfere with the patient’s surgical result [22]. The instances of modified instrumentation but satisfactory curve correction (4) or modified curve correction (3) were justifiably guided by clear focal decrements and comprise the rational for monitoring. The two deferred fusions were similarly justified and subsequently completed successfully. The lack of surgical interference from patient twitch confirms that partial muscle relaxation is unnecessary [20].

The one bitten tongue during M3/4 TES might have been prevented with soft bite blocks that we have since used routinely. The absence of other adverse effects reconfirms that TES MEP monitoring is sufficiently safe for clinical use [15, 22].

Conclusions

These methods are reliable and rapid, provide technical/systemic control, avoid false results, adjust to scoliosis-related non-decussation and enhance intraoperative spinal cord and arm neural protection. In particular, SEP optimization accelerates surgical feedback and muscle MEP monitoring should further reduce paraplegia risk. Radiculopathy and delayed paraparesis can evade detection.

Acknowledgments

The following technologists participated in the recordings: Mohammad Al Enazi, William Gene, Betty Jarvis, Judy Barclay, Andrew Warrington, Brent Hedgecock, Ameer Jan, Saima Naseer and Marela Bien.

Conflict of interest statement None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.American Electroencephalographic Society Guideline eleven: guidelines for intraoperative monitoring of sensory evoked potentials. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;11(1):77–87. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199401000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosley TM, Salih MA, Jen JC, et al. Neurologic features of horizontal gaze palsy and progressive scoliosis with mutations in ROBO3. Neurology. 2005;64(7):1196–1203. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000156349.01765.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calancie B, Harris W, Broton JG, et al. “Threshold-level” multipulse transcranial electrical stimulation of motor cortex for intraoperative monitoring of spinal motor tracts: description of method and comparison to somatosensory evoked potential monitoring. J Neurosurg. 1998;88(3):457–470. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.3.0457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawson EG, Sherman JE, Kanim LE, et al. Spinal cord monitoring: results of the Scoliosis Research Society and the European Spinal Deformity Society survey. Spine. 1991;16(8 Suppl):S361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deletis V. Intraoperative neurophysiology and methodologies used to monitor the functional integrity of the motor system. In: Deletis V, Shils JL, editors. Neurophysiology in neurosurgery. CA: Academic; 2002. pp. 25–51. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holdefer RN, Sadleir R, Russell MJ. Predicted current densities in the brain during transcranial electrical stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(6):1388–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwasaki H, Tamaki T, Yoshida M, Ando M, Yamada H, Tsutsui S, Takami M. Efficacy and limitations of current methods of intraoperative spinal cord monitoring. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8(5):635–642. doi: 10.1007/s00776-003-0693-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalkman CJ, ten Brink SA, Been HD, et al. Variability of somatosensory cortical evoked potentials during spinal surgery: effects of anesthetic technique and high-pass digital filtering. Spine. 1991;16(8):924–929. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199108000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langeron O, Vivien B, Paqueron X, et al. Effects of propofol, propofol-nitrous oxide and midazolam on cortical somatosensory evoked potentials during sufentanil anaesthesia for major spinal surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82(3):340–345. doi: 10.1093/bja/82.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leppanen RE, American Society of Neurophysiological Monitoring Intraoperative monitoring of segmental spinal nerve root function with free-run and electrically-triggered electromyography and spinal cord function with reflexes and F-responses: a position statement by the American Society of Neurophysiological Monitoring. J Clin Monit Comput. 2005;19(6):437–461. doi: 10.1007/s10877-005-0086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lesser RP, Raudzens P, Luders H, et al. Postoperative neurological deficits may occur despite unchanged intraoperative somatosensory evoked potentials. Ann Neurol. 1986;19(1):22–25. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyon R, Feiner J, Lieberman JA. Progressive suppression of motor evoked potentials during general anesthesia: the phenomenon of “anesthetic fade”. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2005;17(1):13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacDonald DB. Individually optimizing posterior tibial somatosensory evoked potential P37 scalp derivations for intraoperative monitoring. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;18(4):364–371. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200107000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacDonald DB, Janusz M. An approach to intraoperative monitoring of thoracoabdominal aneurysm surgery. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;19(1):43–54. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacDonald DB. Safety of intraoperative transcranial electric stimulation motor evoked potential monitoring. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;19(5):416–429. doi: 10.1097/00004691-200210000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacDonald DB, Al-Zayed Z, Khodeir I, Stigsby B. Monitoring scoliosis surgery with combined transcranial electric motor and cortical somatosensory evoked potentials from the lower and upper extremities. Spine. 2003;28(2):194–203. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200301150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald DB, Streletz L, Al-Zayed Z, Abdool S, Stigsby B. Intraoperative neurophysiologic discovery of uncrossed sensory and motor pathways in a patient with horizontal gaze palsy and scoliosis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115(3):576–582. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacDonald DB, Stigsby B, Al-Zayed Z. A comparison between derivation optimization and Cz’-FPz for posterior tibial P37 somatosensory evoked potential intraoperative monitoring. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:1925–1930. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDonald DB, Al Zayed Z, Stigsby B. Tibial somatosensory evoked potential intraoperative monitoring: Recommendations based on signal to noise ratio analysis of popliteal fossa, optimized P37, standard P37 and P31 potentials. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116(8):1858–1869. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDonald DB. Intraoperative motor evoked potential monitoring: overview and update. J Clin Monit Comput. 2006;20(5):347–377. doi: 10.1007/s10877-006-9033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacDonald DB, Dong CC (2006) Spinal cord monitoring of descending aortic procedures. In: Nuwer MR (eds) Monitoring neural function during surgery: handbook of clinical neurophysiology (in press)

- 22.MacDonald DB, Deletis V (2006) Safety issues during surgical monitoring. In: Nuwer MR (eds) Monitoring neural function during surgery: handbook of clinical neurophysiology (in press)

- 23.Nuwer MR, Dawson EG, Carlson LG, et al. Somatosensory evoked potential spinal cord monitoring reduces neurologic deficits after scoliosis surgery: results of a large multicenter survey. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1995;96(1):6–11. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(94)00235-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Brien MF, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, et al. Evoked potential monitoring of the upper extremities during thoracic and lumbar spinal deformity surgery: a prospective study. J Spinal Disord. 1994;7(4):277–284. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199408000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pathak KS, Amaddio MD, Scoles PV, et al. Effects of halothane, enflurane, and isoflurane in nitrous oxide on multilevel somatosensory evoked potentials. Anesthesiology. 1989;70(2):207–212. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198902000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pechstein U, Nadstawek J, Zentner J, et al. Isoflurane plus nitrous oxide versus propofol for recording of motor evoked potentials after high frequency repetitive electrical stimulation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;108(2):175–181. doi: 10.1016/S0168-5597(97)00086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelosi L, Stevenson M, Hobbs GJ, et al. Intraoperative motor evoked potentials to transcranial electrical stimulation during two anaesthetic regimens. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112(6):1076–1087. doi: 10.1016/S1388-2457(01)00529-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelosi L, Lamb J, Grevitt M, Mehdian SMH, Webb JK, Blumhardt LD. Combined monitoring of motor and somatosensory evoked potentials in orthopaedic spinal surgery. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113:1082–1091. doi: 10.1016/S1388-2457(02)00027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Lyon R, Zada G, Lamborn KR, Gupta N, Parsa AT, McDermott MW, Weinstein PR. Changes in transcranial motor evoked potentials during intramedullary spinal cord tumor resection correlate with postoperative motor function. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(5):982–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwartz DM, Drummond DS, Hahn M, et al. Prevention of positional brachial plexopathy during surgical correction of scoliosis. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13(2):178–182. doi: 10.1097/00002517-200004000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shahin GM, Hamerlijnck RP, Schepens MA, et al. Upper and lower extremity somatosensory evoked potential recording during surgery for aneurysms of the descending thoracic aorta. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1996;10(5):299–304. doi: 10.1016/S1010-7940(96)80086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taniguchi M, Nadstawek J, Pechstein U, et al. Total intravenous anesthesia for improvement of intraoperative monitoring of somatosensory evoked potentials during aneurysm surgery. Neurosurgery. 1992;31(5):891–897. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199211000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toleikis JR, American Society of Neurophysiological Monitoring Intraoperative monitoring using somatosensory evoked potentials: a position statement by the American Society of Neurophysiological Monitoring. J Clin Monit Comput. 2005;19(3):241–258. doi: 10.1007/s10877-005-4397-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ulkatan S, Neuwirth M, Bitan F, Minardi C, Kokoszka A, Deletis V. Monitoring of scoliosis surgery with epidurally recorded motor evoked potentials (D wave) revealed false results. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(9):2093–2101. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vossler DG, Stonecipher T, Millen MD. Femoral artery ischemia during spinal scoliosis surgery detected by posterior tibial nerve somatosensory-evoked potential monitoring. Spine. 2000;25(11):1457–1459. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200006010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfe DE, Drummond JC. Differential effects of isoflurane/nitrous oxide on posterior tibial somatosensory evoked responses of cortical and subcortical origin. Anesth Analg. 1988;67(9):852–859. doi: 10.1213/00000539-198809000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]