Abstract

Adenosine is a biologically active molecule that is formed at sites of metabolic stress associated with trauma and inflammation, and its systemic level reaches high concentrations in sepsis. We have recently shown that inactivation of A2A adenosine receptors decreases bacterial burden as well as IL-10, IL-6, and MIP-2 production in mice that were made septic by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Macrophages are important in both elimination of pathogens and cytokine production in sepsis. Therefore, in the present study, we questioned whether macrophages are responsible for the decreased bacterial load and cytokine production in A2A receptor-inactivated septic mice. We showed that A2A KO and WT peritoneal macrophages obtained from septic animals were equally effective in phagocytosing opsonized E. coli. IL-10 production induced by opsonized E. coli was decreased in macrophages obtained from septic A2A KO mice as compared to WT counterparts. In contrast, the release of IL-6 and MIP-2 induced by opsonized E. coli was higher in septic A2A KO macrophages than WT macrophages. These results suggest that peritoneal macrophages are not responsible for the decreased bacterial load and diminished MIP-2 and IL-6 production that are observed in septic A2A KO mice. In contrast, peritoneal macrophages may contribute to the suppressive effect of A2A receptor inactivation on IL-10 production during sepsis.

Keywords: Adenosine, Cytokines, Inflammation, Macrophages, Phagocytosis, Sepsis

Introduction

Severe sepsis is an extremely costly medical problem in the United States and develops in >750,000 people annually. Although the treatment of primary infections per se is well-established, ~200,000 deaths/year occur as a result of residual sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction [1, 2]. Current theory suggests that the sepsis syndrome is associated with an early overwhelming innate immune response, characterized by unabated activation and release of pro-inflammatory mediators. Subsequently, the exaggerated systemic inflammatory response is counterbalanced by sustained expression of potent anti-inflammatory mediators, which often results in the desensitization of effector cells (such as phagocytes) and development of a hypoimmune or “immunoparalytic” state. In fact, the inability to kill invading pathogens effectively at later stages during sepsis is due to immunosupression, and it is also a major cause of late organ dysfunction syndrome [3, 4]. Potential mechanisms of immune suppression after a septic insult include decreased antigen presentation, diminished phagocytosis of pathogens, as well as dysregulation in cytokine production [5–9].

Adenosine, an endogenous purine nucleoside, is a biologically active extracellular signaling molecule that is formed at sites of metabolic stress associated with hypoxia, ischemia, trauma, or inflammation. Systemic adenosine levels are highly elevated in septic patients [10–12]. Adenosine acts by engaging A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 adenosine receptors [13], through which it can exert immunosuppressive effects [14–21]. Besides the immunomodulatory effect of A3 [22, 23] and A2B receptors [24], the most potent immunosuppressive effects of adenosine are attributed to occupancy of A2A receptors on immune cells. Stimulation of A2A receptors induces many phenotypic changes in immune cells that are characteristic of the late “immunoparalytic” phase of sepsis [25–30]. We demonstrated previously, by using genetic and pharmacological inactivation of the A2A receptor in the clinically relevant cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model of sepsis [31] that stimulation of A2A receptors contributed to the lethal effect of sepsis and led to increased bacterial burden [32]. Furthermore, stimulation of A2A receptors increased levels of the immunoregulatory cytokines IL-10, IL-6, and MIP-2. Because macrophages are important in mediating cytokine production and anti-bacterial defense in septic mice, we questioned whether the increased bacterial burden and cytokine production caused by the activation of A2A receptors in septic animals are mediated by macrophages.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals and cell cultures

A2A receptor KO mice and their WT littermates [32, 33] on the CD-1 background were bred in a specific pathogen-free facility, using founder heterozygous male and female mice. CD-1 male mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. All mice were maintained in accordance with the recommendations of the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals,” and the experiments were approved by the New Jersey Medical School Animal Care Committee. WT and KO littermates of heterozygous parents were used exclusively in all studies. At weaning, a 0.5-cm tail sample was removed for the purpose of DNA collection for genotyping. Genotyping was performed by using RT-PCR as described previously [32–34]. CLP-elicited mouse peritoneal macrophages were cultured in Dulbeccos’s modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 1.5 mg/ml sodium bicarbonate in a humified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Cecal ligation and puncture

Polymicrobial sepsis was induced by subjecting mice to CLP, as we have described previously [32]. Six- to eight-week-old male A2AR KO or WT mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg), given intraperitoneally (i.p.). Under aseptic conditions, a 2-cm midline laparotomy was performed to allow exposure of the cecum with adjoining intestine. Approximately two-thirds of the cecum was tightly ligated with a 3.0 silk suture, and the ligated part of the cecum was perforated twice (through and through) with a 20-gauge needle (BD Biosciences). The cecum was then gently squeezed to extrude a small amount of feces from the perforation sites. The cecum was then returned to the peritoneal cavity, and the laparotomy was closed in two layers with 4.0 silk sutures. The mice were resuscitated with 1 ml of physiological saline injected subcutaneously (s.c.) and returned to their cages with free access to food and water.

Harvesting of peritoneal macrophages

Sixteen hours after the operation, mice were reanesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg i.p.), and peritoneal macrophages were harvested in 4 ml of sterile physiological saline. Peritoneal cells were seeded into multiwell tissue culture plates. After 4 h of incubation, nonadherent cells were removed by washing with serum-free DMEM, following which phagocytosis assay was performed.

Opsonization of E. coli and phagocytosis assay

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled E. coli (Molecular Probes) were opsonized by incubation with an equal volume of opsonizing reagent (Molecular Probes) for 1 h at 37°C. The bacteria were then washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline and added to macrophages at a macrophage-to-bacteria ratio of 1:50 for 2.5, 5, or 16 h. At the end of the incubation period, the medium was removed and frozen until use in ELISA experiments (see below). Thereafter, 100 μl of 250 μg/ml Trypan Blue suspension was added to all wells for 1 min. The Trypan Blue solution was then removed by aspiration, and the experimental and control wells (without peritoneal macrophages) were read with a fluorescence plate reader at 480 nm for excitation and 520 nm for emission.

Determination of IL-10, IL-6, and MIP-2 cytokine levels

IL-10, IL-6, and MIP-2 cytokine levels were determined from cell supernatants taken at the indicated points following treatment of macrophages with opsonized bacteria. Cytokine concentrations were measured using DuoSet ELISA kits (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Values in the figures are expressed as mean ± SEM of n observations. Statistical analysis of the data was performed by one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett’s test, as appropriate.

Results

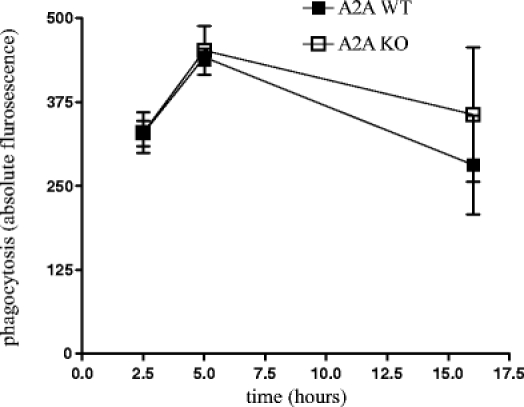

Effect of A2A adenosine receptor inactivation on macrophage phagocytosis of opsonized E. coli

Macrophages play an essential role in the innate immune response against bacterial invasion, and they also eliminate bacteria from the peritoneum and bloodstream during sepsis. Since the inactivation of A2A receptors enhances bacterial clearance, we first examined whether the absence of A2A receptors has any impact on the phagocytic activity of peritoneal macrophages. As illustrated in Fig. 1, no significant differences in macrophage phagocytotic activity were detected between A2A WT (n = 5) or A2A KO (n = 8) cells.

Fig. 1.

Phagocytic activity of A2A WT and KO CLP-elicited peritoneal macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages were harvested from A2A WT and KO mice after 16 h of polymicrobial sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture. Cells were seeded at 106/ml density in 96-well plates. Peritoneal macrophages were then stimulated with IgG-coated, FITC-labeled E. coli for 2.5, 5 or 16 h, and phagocytosis was quantitated by measuring fluorescence. Results (mean ± SEM, n = 5–8) shown are one representative experiment from three separate studies

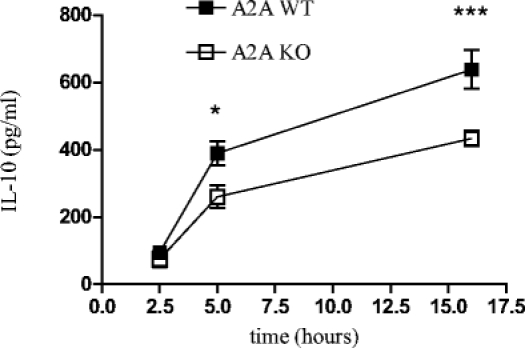

Effect of A2A adenosine receptor inactivation on macrophage cytokine release

IL-10 is a potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive cytokine that has been shown to be elevated in patients with sepsis. We have previously shown that its level was markedly lower in A2A KO mice than its WT littermates under septic conditions. Therefore, we measured the IL-10 level after stimulation with opsonized E. coli in CLP-elicited peritoneal macrophages. We observed that opsonized E. coli enhanced IL-10 levels (n = 30 in case of A2A WT), the induction of which was inhibited by genetic inactivation of A2A receptors (n = 48 in case of A2A KO) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

IL-10 release is decreased by peritoneal macrophages obtained from A2A KO vs. WT mice. Peritoneal macrophages were obtained from A2A WT and KO mice 16 h after cecal ligation and puncture. Cells were plated at a density of 106/ml in 96-well plates. Cells were stimulated with IgG-coated FITC-labeled E. coli for the indicated time periods, and IL-10 release was measured using ELISA. Results (mean ± SEM) depicted are from n = 30–48 wells from six separate experiments. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.005 vs. A2A WT group

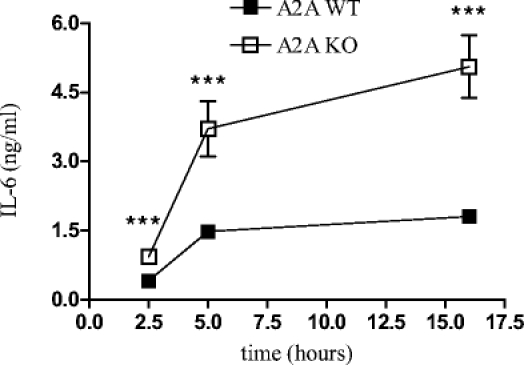

Our previous work has shown that the level of IL-6 was markedly lower in the bloodstream of A2A KO receptor mice compared with their WT counterparts in CLP-induced polymicrobial sepsis [32]. To assess the effect of A2A receptor inactivation on IL-6 release by macrophages, CLP-elicited peritoneal macrophages were stimulated with opsonized E. coli. We found that the IL-6 level was markedly higher in A2A KO macrophages stimulated with opsonized E. coli (n = 48) than in WT (n = 30) macrophages at 2.5 h, and this difference was even more robust at 5 and 16 h (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of genetic inactivation of the A2A receptor on IL-6 production by CLP-elicited peritoneal macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages were obtained from A2A WT and KO mice 16 h after cecal ligation and puncture. Cells were plated at a density of 106/ml in 96-well plates. Cells were stimulated with IgG-coated FITC-labeled E. coli for the indicated time periods, and IL-6 release was measured using ELISA. Results (mean ± SEM) depicted are from n = 30–48 wells from six separate experiments. ***P < 0.005 vs. A2A WT group

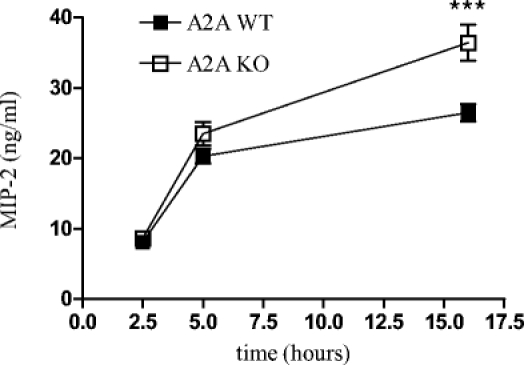

We previously observed that MIP-2 production was decreased both in the bloodstream and in the peritoneum of A2A KO vs. WT mice under septic conditions [32]. Consequently, we studied the effect of opsonized E. coli on the release of the MIP-2 in CLP-elicited macrophages. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the MIP-2 release induced by opsonized E. coli was higher in A2A KO (n = 48) than WT (n = 30) macrophages.

Fig. 4.

Effect of genetic inactivation of the A2A receptor on MIP-2 production by CLP-elicited peritoneal macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages were obtained from A2A WT and KO mice 16 h after CLP. Cells were plated at a density of 106/ml in 96-well plates. Cells were stimulated with IgG-coated FITC-labeled E. coli for the indicated time periods, and MIP-2 release was measured using ELISA. Results (mean ± SEM) depicted are from n = 30–48 wells from six separate experiments. ***P < 0.05 vs. A2A WT group

Discussion

The most important result of this study is that the increased bacterial clearance we found in septic A2A KO mice [32] is not due to the enhanced phagocytic activity of peritoneal macrophages. Bacterial clearance is an elaborate process that includes bacterial killing as well as phagocytosis by macrophages and neutrophils. We reported in a previous study that A2A receptor inactivation decreased bacterial burden in septic mice [32]. Thus, in the present study we questioned whether this decreased bacterial load in A2A KO mice was due to enhanced phagocytosis by macrophages. Our results indicated that this was not the case, because A2A KO macrophages did not ingest greater numbers of opsonized E. coli than WT macrophages.

The regulation of FcγR-mediated phagocytosis by adenosine was one of the first effects described for this purine nucleoside in modifying macrophage functionality [35]. It is well known that adenosine augments FcγR-mediated phagocytosis by human monocytes [30]. In contrast to its stimulatory effect on phagocytosis by human monocytes, adenosine reduced FcγR-mediated erythrocyte phagocytosis by mouse peritoneal macrophages [36, 37], suggesting that depending on the cellular stimulus and source, adenosine may have differential effects on phagocytosis. In this study, we found that there was no difference in the FcγR-mediated phagocytotic activity of A2A KO and WT peritoneal macrophages. These results suggest that the decreased bacterial burden in A2A KO mice under septic conditions is not due to enhanced phagocytosis by macrophages. Since actual bacterial burden is determined by both bacterial dissemination and clearance, and clearance is a complex process that includes not only phagocytosis but also killing of pathogens by macrophages and other cell types, it will be important in the future to study how A2A receptors govern all these bactericidal functions.

In a previous study [32], we showed that A2A receptor inactivation decreased IL-10, IL-6, and MIP-2 production in the bloodstream and in the peritoneum in CLP-induced sepsis. In this study we observed that opsonized-E. coli-induced IL-10 release was diminished in A2A KO peritoneal macrophages in vitro. This finding is in accord with our previous in vivo data obtained in the CLP model and suggests that under septic conditions the decreased IL-10 level of A2A KO mice is due to a decreased production of IL-10 by macrophages. In contrast to the in vivo results showing decreased IL-6 and MIP-2 production in A2A receptor-inactivated mice [32], we found that peritoneal macrophages isolated from A2A KO mice showed enhanced IL-6 and MIP-2 production as compared with WT macrophages. These results suggest that other cell types or other macrophage populations may be responsible for IL-6 and MIP-2 production under septic conditions. In this regard, it is noteworthy that Riedemann et al. [38] demonstrated that serum IL-6 concentrations during sepsis in rats are reduced when neutrophils are depleted. Furthermore, it has been reported that GdCl3 (a Kupffer cell-depleting agent) prevents the up-regulation of IL-6 in a mouse septic peritonitis model [39]. In addition, it has been shown that MIP-2 production by liver mononuclear cells in mice with peritonitis is significantly increased compared with sham-operated mice, confirming the important role of Kupffer cells in cytokine production during sepsis [40]. Therefore, it is possible that either neutrophils or Kupffer cells, both of which express A2A receptors [14, 25], are responsible for the decreased IL-6 and MIP-2 levels that we detected in A2A KO vs. WT mice [32].

In summary, A2A receptors differentially regulate immune function in vitro and in vivo. In the future it will be interesting to determine the mechanisms that are responsible for these differences.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM66189 and the Intramural Research Program of NIH, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, as well as Hungarian Research Fund OTKA (T 049537) and Hungarian National R&D Programme 1A/036/2004.

References

- 1.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J et al (2001) Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 29:1303–1310 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S et al (2003) The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med 348:1546–1554 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Benjamim CF, Hogaboam CM, Kunkel SL (2004) The chronic consequences of severe sepsis. J Leukocyte Biol 75:408–412 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Oberholzer A, Oberholzer C, Moldawer LL (2002) Interleukin-10: a complex role in the pathogenesis of sepsis syndromes and its potential as an anti-inflammatory drug. Crit Care Med 30:58–63 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE (2003) The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med 348:138–150 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Riedemann NC, Guo RF, Ward PA (2003) The enigma of sepsis. J Clin Invest 112:460–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Ayala A, Herdon CD, Lehman DL et al (1996) Differential induction of apoptosis in lymphoid tissues during sepsis: variation in onset, frequency, and the nature of the mediators. Blood 87:4261–4275 [PubMed]

- 8.Oberholzer A, Oberholzer C, Moldawer LL (2001) Sepsis syndromes: understanding the role of innate and acquired immunity. Shock 16:83–96 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Murphy TJ, Paterson HM, Mannick JA et al (2004) Injury, sepsis, and the regulation of Toll-like receptor responses. J Leukocyte Biol 75:400–407 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Martin C, Leone M, Viviand X et al (2000) High adenosine plasma concentration as a prognostic index for outcome in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med 28:3198–3202 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Jabs CM, Sigurdsson GH, Neglen P (1998) Plasma levels of high-energy compounds compared with severity of illness in critically ill patients in the intensive care unit. Surgery 124:65–72 [PubMed]

- 12.Schmidt H, Siems WG, Grune T et al (1995) Concentration of purine compounds in the cerebrospinal fluid of infants suffering from sepsis, convulsions and hydrocephalus. J Perinat Med 23:167–174 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA et al (2001) International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev 53:527–552 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Hasko G, Cronstein BN (2004) Adenosine: an endogenous regulator of innate immunity. Trends Immunol 25:33–39 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hasko G, Deitch EA, Szabo C et al (2002) Adenosine: a potential mediator of immunosuppression in multiple organ failure. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2:440–444 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Sitkovsky M, Lukashev D, Apasov S et al (2004) Physiological control of immune response and inflammatory tissue damage by hypoxia-inducible factors and adenosine A2A receptors. Annu Rev Immunol 22:657–682 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Linden J (2001) Molecular approach to adenosine receptors: receptor-mediated mechanisms of tissue protection. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 41:775–787 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Ohta A, Sitkovsky M (2001) Role of G-protein-coupled adenosine receptors in downregulation of inflammation and protection from tissue damage. Nature 414:916–920 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Blackburn MR (2003) Too much of a good thing: adenosine overload in adenosine-deaminase-deficient mice. Trends Pharmacol Sci 24:66–70 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Thompson LF, Eltzschig HK, Ibla JC et al (2004) Crucial role for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) in vascular leakage during hypoxia. J Exp Med 200:1395–1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Eltzschig HK, Thompson LF, Karhausen J et al (2004) Endogenous adenosine produced during hypoxia attenuates neutrophil accumulation: coordination by extracellular nucleotide metabolism. Blood 104:3986–3992 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Gessi S, Varani K, Merighi S et al (2004) Expression of A3 adenosine receptors in human lymphocytes: up-regulation in T cell activation. Mol Pharmacol 65(3):711–719 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Lee HT, Kim M, Joo JD et al (2006) A3 adenosine receptor activation decreases mortality and renal and hepatic injury in murine septic peritonitis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291(4):959–969 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Ryzhov S, Goldstein AE, Matafonov A et al (2004) Adenosine-activated mast cells induce IgE synthesis by B lymphocytes: an A2B-mediated process involving Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 with implications for asthma. J Immunol 172(12):7726–7733 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Cronstein BN, Daguma L, Nichols D et al (1990) The adenosine/neutrophil paradox resolved: human neutrophils possess both A1 and A2 receptors that promote chemotaxis and inhibit O2 generation, respectively. J Clin Invest 85:1150–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Eppell BA, Newell AM, Brown EJ (1989) Adenosine receptors are expressed during differentiation of monocytes to macrophages in vitro: implications for regulation of phagocytosis. J Immunol 143:4141–4145 [PubMed]

- 27.Link AA, Kino T, Worth JA et al (2000) Ligand-activation of the adenosine A2a receptors inhibits IL-12 production by human monocytes. J Immunol 164:436–442 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Khoa ND, Montesinos MC, Reiss AB et al (2001) Inflammatory cytokines regulate function and expression of adenosine A2A receptors in human monocytic THP-1 cells. J Immunol 167:4026–4032 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Pinhal-Enfield G, Ramanathan M, Hasko G et al (2003) An angiogenic switch in macrophages involving synergy between Toll-like receptors 2, 4, 7, and 9 and adenosine A2A receptors. Am J Pathol 163:711–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Hasko G, Pacher P, Deitch EA et al (2007) Shaping of monocyte and macrophage function by adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Therap 113:264–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Bone RC, Sprung CL, Sibbald WJ (1992) Definitions for sepsis and organ failure. Crit Care Med 20:724–726 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Nemeth ZH, Csoka B, Wilmanski J et al (2006) Adenosine A2A receptor inactivation increases survival in polymicrobial sepsis. J Immunol 176:5616–5626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Ledent C, Vaugeois JM, Schiffmann SN et al (1997) Aggressiveness, hypoalgesia and high blood pressure in mice lacking the adenosine A2a receptor. Nature 388:674–678 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Nemeth ZH, Lutz CS, Csoka B et al (2005) Adenosine augments IL-10 production by macrophages through an A2B receptor-mediated posttranscriptional mechanism. J Immunol 175:8260–8270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Pike MC, Kredich NM, Snyderman R (1978) Requirement of S-adenosyl-L-methionine-mediated methylation for human monocytes chemotaxis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 75(8):3928–3932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Leonard EJ, Skeel A, Chiang PK et al (1978) The action of the adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase inhibitor, 3-deazaadenosine, on phagocytic function of mouse macrophages and human monocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 84:102–109 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Sung SJ, Silverstein SC (1985) Inhibition of macrophage phagocytosis by methylation inhibitors. Lack of correlation of protein carboxymethylation and phospholipid methylation with phagocytosis. J Biol Chem 260:546–554 [PubMed]

- 38.Riedemann NC, Guo RF, Hollmann TJ et al (2004) Regulatory role of C5a in LPS-induced IL-6 production by neutrophils during sepsis. FASEB J 18(2):370–372 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Koo DJ, Chaudry IH, Wang P (1999) Kupffer cells are responsible for producing inflammatory cytokines and hepatocellular dysfunction during early sepsis. J Surg Res 83(2):151–157 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Tsujimoto H, Ono S, Majima T et al (2005) Neutrophil elastase, MIP-2, and TLR-4 expression during human and experimental sepsis. Shock 23(1):39–44 [DOI] [PubMed]