Abstract

Increasing attention has been devoted to elucidating the mechanism of lost or decreased expression of MHC or melanoma-associated antigens (MAAs), which may lead to tumor escape from immune recognition. Loss of expression of HLA class I or MAA has, as an undisputed consequence, loss of recognition by HLA class I–restricted cytotoxic T cells (CTLs). However, the relevance of down-regulation remains in question in terms of frequency of occurrence. Moreover the functional significance of epitope down-regulation, defining the relationship between MHC/epitope density and CTL interactions, is a matter of controversy, particularly with regard to whether the noted variability of expression of MHC/epitope occurs within a range likely to affect target recognition by CTLs. In this study, bulk metastatic melanoma cell lines originated from 25 HLA-A*0201 patients were analyzed for expression of HLA-A2 and MAAs. HLA-A2 expression was heterogeneous and correlated with lysis by CTLs. Sensitivity to lysis was also independently affected by the amount of ligand available for binding at concentrations of 0.001 to 1 mM. Natural expression of MAA was variable, independent from the expression of HLA-A*0201, and a significant co-factor determining recognition of melanoma targets. Thus, the naturally occurring variation in the expression of MAA and/or HLA documented by our in vitro results modulates recognition of melanoma targets and may (i) partially explain CTL–target interactions in vitro and (ii) elucidate potential mechanisms for progressive escape of tumor cells from immune recognition in vivo.

Developments in recent years have been crucial for understanding T-cell recognition of melanoma in vitro and perhaps in vivo. Many melanoma-associated antigens (MAAs) recognized by T cells have been identified (Rosenberg, 1997). These often include differentiation antigens expressed by normal cells of the same lineage. Interestingly, T cells reactive against such self-molecules have been detected among peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) of melanoma patients and, to a lesser extent, in normal non-tumor-bearing individuals (Marincola et al., 1996b). Furthermore, in vitro sensitization experiments have shown that potent MAA-specific T-cell reactivity can be induced in vivo by active specific vaccination with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I–restricted epitopic determinants from such MAAs (Cormier et al., 1997). Yet, in a large proportion of patients, an uneventful co-existence occurs in vivo between effector and target cells.

Among the possible mechanisms that could explain this paradoxical lack of effectiveness of specific T cells in vivo are escape mechanisms able to “stealth” tumor cells from recognition. Such mechanisms include loss or down-regulation of MAAs (Chen et al., 1995; Marincola et al., 1996a) and abnormalities of expression of HLA class I antigens (Ferrone and Marincola, 1995). While the functional effect of total loss of HLA class I expression on cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) recognition is undisputed, its actual frequency of occurrence remains a topic of debate. Melanoma lesions are also extremely heterogeneous in expression of MAAs in vivo. However, a detailed analysis quantifying variability of MAA expression by cell lines from metastatic melanoma has never been performed.

While it is accepted that loss of HLA expression leads to a loss of target recognition by CTLs, the relevance of down-regulation of HLA class I antigen expression remains in question in terms of frequency of occurrence. Most importantly, the functional significance of MHC–peptide (epitope density) down-regulation, defined as the direct effect of epitope down-regulation of CTL recognition, remains a matter of controversy. It has been suggested that as few as 1 peptide–MHC complex on a target cell is sufficient to elicit a CTL response (Sykulev et al., 1996). This concept has suggested to many investigators that minimal amounts of endogenous antigen expression may correspond to adequate epitope density on the surface of target cells for CTL recognition and killing. As a consequence, many dismiss the possibility that tumor escape from immune recognition may start with gradual and saddle decrements of epitope density. In natural conditions, however, endogenous peptides compete with more than 1,000 other peptides for binding to specific HLA alleles, and therefore, a large number of MHC and/or endogenous antigen molecules may be necessary to achieve this minimal threshold of epitope density.

Although the theoretical basis for a contribution of the number of MHC–antigen complexes to peripheral tolerance is well established, there are few examples in which the conditions predicted by such models are met in natural conditions. We have previously shown that a strict correlation exists between the relative number of HLA-A2 molecules expressed by a variety of clones derived from a bulk melanoma line and their recognition by HLA-A*0201-restricted CTLs in situations of borderline expression of MAA and/or MHC ((Rivoltini et al., 1995). In addition, a correlation between the variability of expression of tumor antigens and recognition by CTLs has been reported (Marincola et al., 1996a). These studies, however, did not address the degree of variability, frequency and intensity of occurrence in natural conditions. In this study, therefore, we aimed at documenting the natural range of expression of HLA class I and/or MAAand evaluating its potential functional significance. A synchronous evaluation of HLA class I and MAA expression was performed in a large panel of cell lines derived from patients with metastatic melanoma. In this model, the natural variation of expression of HLA and/or MAA on target cells modulated CTL recognition. Our findings have significant implications for understanding (i) CTL–target interaction in vitro and (ii) mechanisms of progressive tumor escape from immune recognition.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Culture medium

All cell lines and lymphocytes were maintained in complete medium (CM), consisting of RPMI 1640 (Biofluids, Rockville, MD) supplemented with 10 mM Hepes buffer, 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Biofluids), 10 µg/ml ciprofloxacin (Bayer, West Haven, CT), 0.03% l-glutamine (Biofluids), 0.5 mg/ml amphotericin B (Biofluids) and 10% heat-inactivated human AB serum (Gemini Bioproducts Inc, Calabasas, CA).

MART-1/MelanA and Flu M1 peptides

MART-127–35 (AAGIGILTV) was produced by solid-phase synthesis techniques by Peptide Technologies, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD). Flu-M158–66 (GILGFVFTL) from the influenza matrix protein was purchased from Multiple Peptide Systems (San Diego, CA). Gp100154 (KTWGQYWQV), gp100209 (ITDQVPFSV) and gp100280 (YLEPGPVTA) were synthesized by solid-phase synthesis. Peptide purity (>99%) was confirmed by mass spectrometry.

Anti-HLA and anti-melanoma antibodies

The following murine monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) were used: W6/32 (Sera Labs, Westbury, NY), which reacts with a monomorphic determinant on the HLA class I MA2.1, and HO-2, which recognizes HLA-A2 and HLA-B17 (HO MAbs were generated in our laboratories and are not currently published). CR11–351, KS-1, KRE-501, HO-1, HO-3, HO-4 and HO-5 recognize HLA-A2, A-28. BB7.2 recognizes HLA-A2 and A-69. MAb dilutions were selected following guidelines from the HLA and Cancer Workshop (Table I). For analysis of MAA expression, the following MAbs were used: anti-MART-1/MelanA murine IgG2b (M2–7C10) and anti-Pmel17/gp100 MAb HMB45 (Enzo, Farmingdale, NY) at dilutions of 1:1,000 and 1:10, respectively. Secondary staining for FACS consisted of fluorescein (FITC)-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG, -M and -A (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), 0.1 mg/ml, and, for immunohistochemistry, biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG at 1:1,000 dilution (Kirkegaard and Perry, Gaithersburg, MD).

TABLE I.

Variability of HLA-A2 Expression in Melanoma Cell Lines

| MAbs1 |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor number |

HLA2 phenotype |

Relative3 surface (µm²) |

MA2.1 1:10 (B17) |

HO-4 1:10 (A28) |

CR11 1:10 (A28) |

BB7.2 1:10 (A69) |

KRE501 1:10 (A28) |

KS-1 1:10 (A28) |

HO-2 1:10 |

HO-5 1:10 |

HO-3 1:10 |

HO-1 1:10 |

160 1:10 (69) |

| 553* | 2,23 | 3017 | 0 | 31 | 31 | 0 | 31 | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 |

| 1195* | 2,24 | 8167 | 0 | 76 | 117 | 0 | 0 | 66 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 697 | 2,11 | 3420 | 16 | 0 | 578 | 1922 | 2500 | 2484 | 274 | 792 | 1036 | 3809 | 137 |

| 1376 | 1,2 | 7539 | 18 | 0 | 293 | 615 | 768 | 891 | 35 | 193 | 164 | 668 | nd |

| 501 | 2,24 | 2641 | 31 | 0 | 578 | 1047 | 1406 | 1281 | 274 | nd | 762 | 2224 | 198 |

| 1287 | 2,– | 9156 | 37 | 34 | 279 | 619 | 1053 | 1007 | 216 | 503 | 780 | 1953 | nd |

| 1280 | 1,2 | 10930 | 46 | 122 | 762 | 107 | 2026 | 2133 | 61 | 533 | 427 | 1508 | nd |

| 526 | 2,3 | 4776 | 94 | 125 | 1016 | 2859 | 3141 | 3563 | 716 | nd | 1782 | 4673 | 579 |

| 1286 | 2,29 | 6644 | 107 | 168 | 807 | 975 | 1478 | 1569 | 229 | 564 | 427 | 1006 | nd |

| 1102 | 2,24 | 5498 | 117 | 122 | 437 | 945 | 1317 | 1441 | 320 | 990 | 1676 | 4567 | 168 |

| 624 | 2,3 | 2123 | 122 | 107 | 823 | 1584 | 1889 | 2041 | 305 | 731 | 701 | 1432 | nd |

| 1495 | 2,3 | 6358 | 122 | 137 | 548 | 1569 | 1873 | 2285 | 229 | 548 | 731 | 2011 | nd |

| 836 | 2,11 | 7539 | 132 | 140 | 330 | 780 | 810 | 1100 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 1143 | 2,11 | 3215 | 137 | 152 | 762 | 1828 | 2378 | 2529 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 1520 | 2,29 | 9498 | 137 | 107 | 640 | 914 | 1097 | 1097 | 168 | 396 | 320 | 868 | nd |

| 1317 | 1,2 | 6644 | 152 | 137 | 1143 | 2392 | 2803 | 3184 | 244 | nd | 899 | 3336 | 183 |

| 1088 | 1,2 | 8491 | 168 | 152 | 1097 | 1981 | 2803 | 3230 | 229 | 1082 | 792 | 2651 | 137 |

| 1363 | 1,2 | 9847 | 168 | 137 | 1066 | 2270 | 2971 | 3565 | 305 | 1036 | 1097 | 3199 | nd |

| 1479 | 2,3 | 5539 | 168 | 152 | 762 | 2514 | 2179 | 2636 | 350 | 716 | 838 | 2087 | nd |

| 677 | 2,11 | 3017 | 183 | 168 | 1127 | 2102 | 2392 | 3047 | 305 | 899 | 884 | 2087 | nd |

| 1199 | 1,2 | 7539 | 183 | 168 | 1371 | 3093 | 3352 | 3900 | 503 | 1402 | 1508 | 3595 | nd |

| 1390 | 1,2 | 9156 | 198 | 183 | 1295 | 2788 | 3656 | 4283 | 609 | 1722 | 1569 | 3656 | nd |

| 1182 | 2,11 | 4069 | 229 | 198 | 1249 | 2742 | 3016 | 4051 | 411 | 1706 | 1523 | 3489 | nd |

| 1300 | 2,24 | 12861 | 305 | 320 | 2179 | 4632 | 6722 | 7043 | 701 | nd | 2742 | 6995 | 381 |

| 1383 | 2,24 | 10202 | 381 | 396 | 2483 | 3245 | 4157 | 4026 | 366 | 1356 | 1478 | 2940 | nd |

| Average4 | 130 | 133 | 870 | 1741 | 2232 | 2499 | 274 | 607 | 885 | 2351 | 255 | ||

| Correction factor | 1 | 1 | 7 | 13 | 17 | 19 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 18 | 2 | ||

| 883 | 1,3 | 6079 | 0 | 0 | 66 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 1278 | 11,28 | 8167 | 15 | 91 | 518 | 76 | 1615 | 2102 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 1338 | 24,31 | 3420 | 0 | 183 | 1097 | 0 | 4120 | 4150 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

Variability of expression of HLA-A*0201 antigen expression in melanoma cell lines tested with 11 MAbs recognizing different determinants of the HLA-A*0201 heavy chain.

MAbs were obtained from the XII Histocompatibility Workshop in spent medium and diluted according to criteria suggested by the Workshop (Garrido et al., 1997). The additional known HLA class I specificities recognized by each MAb are shown in parentheses.

HLA phenotype of PBMCs from the patient from whom the cell line was developed.

Average surface area of each cell line, calculated by determining the average diameter of each cell line as a proportion of forward scatter of cell lines over beads (bead diameter = 10 µm). The average surface area for each cell line was used for estimation of HLA-A2 surface density as described in the text.

HLA-A*0201 expression is represented as mean equivalent of fluorescence (MEF), as described in “Material and Methods.” The average of all MEF values obtained for each MAb was devided by the average of all MEF values obtained with MAb MA2.1 (selected arbitrarily). This value was used as a correction factor for the strength of each MAb compared with MA2.1 and to normalize (nMEF) values among different MAbs for graphic representation.

Lines 553 and 1195 have been previously shown to have lost HLA-A2 as part of a full HLA haplotype (Marincola et al., 1994).

n.d., not done.

Melanoma and other cell lines

The following breast cancer cell lines were purchased from the ATCC (Rockville, MD): MDA-231 (ATCC HTB 26), SK23-MEL (ATCC HTB 71) and A375-MEL (ATCC CRL 1619). The melanoma line FM3–29-MEL was a gift from Dr. Y. Kawakami (Bethesda, MD). All other lines were derived from surgically removed metastatic melanoma lesions of patients treated at the NCI (Bethesda, MD). Tumor lines were grown in vitro and maintained in monolayer culture as previously described (Marincola et al., 1994). Briefly, specimens were dissociated mechanically to approximately 1-mm-wide pieces, then enzymatic digestion was carried out overnight at room temperature in RPMI 1640 medium (Biofluids) with 30 U/ml deoxyribonuclease (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 100 µg/ml hyaluronidase (Sigma) and 1 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma). After digestion, cells were placed in 24-well plates (Costar, Cambridge MA) in CM. Cultures were split at 70% confluence.

CTL cultures

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

Early bulk tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) cultures (>95% CD8+) were generated from metastatic melanomas and selected for HLA-A*0201-restricted recognition of MART-127–35-expressing targets. MART-127–35-specific CD8+ clones were established from TILs by limiting dilution.

Epitope-specific CTL cultures

Epitope-specific CTL cultures were induced from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) by repeated in vitro stimulation with relevant peptide as previously described (Cormier et al., 1997). TILs were maintained in 6,000 IU IL-2.

Lymphokine-activated killer cell cultures

Lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) cells were generated from donor PBMCs in 6,000 IU IL-2.

HLA typing of lymphocytes and tumor lines

The HLA class I phenotype of patients and/or cell lines was established on PBLs using either the Amos modified microcytotoxicity test or sequence-specific primer PCR. PCR was used for molecular HLA-A2 sub-typing (Player et al., 1996).

Flow-cytometric analysis

Surface expression of antigens

Surface antigen expression was analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence. Primary and secondary staining was performed with 20 µl of the appropriate MAb by incubation for 45 min at 4°C in ice-cold HBSS free of Ca2+, Mg2+ and phenol red; 5% heat-inactivated FBS (Biofluids) and 0.2% sodium azide (FACS buffer). Non-viable cells were gated out with propidium iodide. Ten thousand events were acquired for each analysis.

Intracellular staining for MAA expression

Cells (106) were fixed in 200 µl acetone for 10 min at room temperature, as a modification of a previously described protocol, then treated as above.

Immuno-histochemistry

Surface expression of HLA-A2 was analyzed on cytospin preparations using MA2.1 as primary MAb and biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG (Kirkegaard and Perry), followed by avidin-peroxidase (Vectasin Elite kit; Vector, Burlingame, CA).

Cytotoxicity assays

Standard 51Cr-release assay

Effector cells were plated at different E:T ratios in 96-well, U-bottomed plates (Costar). Supernatants were harvested using the Skatron (Sterling, VA) apparatus and counted in a gamma-counter. Percent lysis was calculated as follows: (experimental cpm − spontaneous cpm) / (maximal cpm − spontaneous cpm) ✕ 100. Later experiments were performed with the calcein-AM fluorescent cytotoxicity assay: 106 target cells/well were incubated with 15 µl calcein-AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for fluorescent labeling. After 30 min, all targets were washed 3 times in CM and plated in triplicate in 96-well, flat-bottomed plates at 3,000 target cells/100 µl. Effector cells were harvested and added to the target cells at E:T ratios of 10:1, 2.5:1 and 0.625:1 in 100 µl CM. Plates were centrifuged at 34 g for 3 min. After 3 hr at 37°C, 5 µl of FluoroQuench (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA) were added to each well to extinguish background fluorescence. Plates were centrifuged, incubated for an additional 60 min and then scanned on a FluorImager 595 (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Fluorescence was quantified using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). Lysis was calculated using the following formula: (1 − [experimental fluorescence − background fluorescence] / [target only fluorescence − background fluorescence]) ✕ 100. In some experiments, tumor cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of exogenous peptide for 2 hr at 37°C before testing. In other experiments, target cell lines were infected at a multiple of infection of 10:1 for 1 hr with the vaccinia virus, including the coding sequence for MART-1/MelanA (rVV-MART-1) or Pmel17/gp100 (rVV-gp100), and expression of MAA by infected targets was documented by intracellular FACS.

PCR amplification

Total NA was isolated from fresh cells using the RNeasy isolation kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA). RNA (4 µg) was transcribed to first-strand cDNA with M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) and oligo (dT) as primer. The MART-1/MelanA gene was PCR-amplified using 3 pairs of primers: MA268 sense 5′-ACTGCTCATCGGCTGTTG-3′ and anti-sense 5′-TTCAGCATGTCTCAGGTG-3′, spanning a 268-bp fragment; MA644 sense 5′-GCAGACAGAGGACTCTCA-3′ and anti-sense 5′-AGTATCATGCATTGCAACAT-3′, spanning a 644-bp fragment; and MA1496 sense 5′-GCAGACAGAGGACTCTCA-3′ and anti-sense 5′-TCTGCACATTCTTGTGAG-3′, spanning a 1,496-bp fragment. Actin was used as positive control. The reaction was performed in a final volume of 20 µl and overlaid with mineral oil. The final reaction mix contained 1 µg of cDNA, 1 U Ampli Taq DNA Polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Branchburg, NJ) and 25 pmol of each primer in a 50 mMKCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.9) and 200 µM of each dNTP solution. PCR analyses were carried out in a Perkin-Elmer Thermal Cycler 9600 using the following parameters: 30 cycles of 30 sec at 96°C, 30 sec at 53°C and 90 sec at 72°C. To monitor the size and amount of amplified product, 4 µl of PCR were electrophoresed through a 2.0% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. The m.w. marker Φ ✕ 174 RF DNA/Hae III (GIBCO BRL) was used. The specificity of the PCR amplification was confirmed by sequencing on an ABI Prism 377 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of HLA and MAA expression

Relative numbers of HLAs and MAAs expressed by different cells were determined by indirect immunofluorescence using primary murine MAbs followed by a secondary FITC-rabbit anti-mouse IgG. The level of cellular fluorescence was then correlated to the level of fluorescence of a set of beads. The beads were either bare or surface-labeled with specified amounts of murine MAb [IgG2a; antigen-binding capacity (ABC) = 3,000; 9,200; 38,000; 150,000; 390,000] and stained with the same fluorescein-labeled rabbit anti-mouse Ig used to label cells in each experiment. The mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) of the beads showed a linear relationship with the specified ABC (R²=0.999, p < 0.0001). In each experiment, a linear regression was calculated, correlating ABC with specific mean fluorescence intensity (SMFI = MFI standard beads − MFI bare beads). The regression formula was then used to determine the relative ABC for each cell population and was termed the mean equivalent of fluorescence (MEF).

Data analysis

The relative surface antigen density for HLA expression (rHLA-A2/S) was determined by dividing the MEF for HLA-A2, as detected by MAb MA2.1, by calculated cell-surface value. The cell surface was deducted by calculating the diameter as a proportion of the forward scatter of each cell line over the forward scatter of beads (10 µm diameter). rHLA-A2/S = (MEFMA2·1/surface area) ✕ 1,000. MEF values for intracellular expression of MAAs were not corrected by cell size because of lack of knowledge about the quantitative relationship between total cellular expression of the antigenic protein and cell-surface density of putative CTL epitopes. Correlation analysis comparing different variables with lysis of target cells was performed using a simple regression model. For graphic representation only, the MEF values for all HLA-A2-specific MAbs were normalized (nMEF) to MA2.1 (selected arbitrarily). This normalization allowed the representation of data in a graphic form without changing the mathematical relationship between MEFs for each MAb. Polynomial regression was used to analyze the relationship between lysis of targets (dependent variable) and rHLA-A2/S expression (independent variable) with the assumption that such a relationship becomes curvilinear at extremes of HLA-A2 expression. FACS positivity was defined as the percentage of cells with MFI above the 97th percentile of staining of the paired negative control (isotype-matched primary IgG + FITC-secondary MAb). Comparison between expression of HLA-A2 and MAAs was carried out using a standard linear regression model. For analysis of expression of MAAs between lines derived from patients with or without the HLA-A*0201 phenotype, the χ² test for independence was used.

RESULTS

Variability of HLA class I expression in metastatic melanoma cell lines

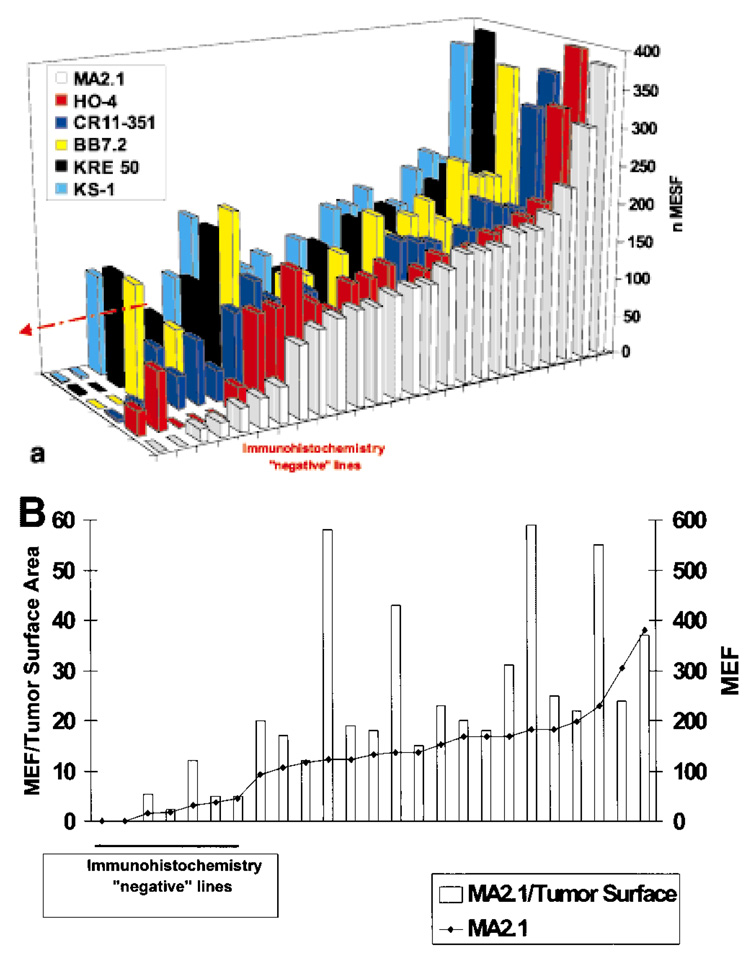

Twenty-five HLA class I-expressing cell lines derived from metastatic lesions of HLA-A*0201 melanoma patients were analyzed with MAbs specific for various determinants of HLA class I. Expression of HLA class I, as detected by MAb W6/32 directed against the monomorphic component of the HLA-class I–β2-microglobulin complex, was present in 100% of cell lines. Despite the relative homogeneity of expression of HLA class I, a significant variability in HLA-A2 expression was noted (Table I). Two cell lines did not express HLA-A2 according to at least 3 MAbs. We have previously shown that the loss of expression of HLA-A2 in these 2 lines is due to a genomic deletion encompassing a full HLA haplotype. The low level of reactivity noted with the other HLA-A2-specific MAbs (particularly in the case of 1195-MEL) could therefore be explained by cross-reactivity with other surface antigens. A clear pattern of cross-reactivity for each MAb could not be defined here, though cross-reactivity between HLA-A2 and -A24 (the other HLA-A allele expressed by 1195-MEL) is established. When lines from non-HLA-A2 patients were analyzed, HLA-A28- (1278-MEL) and HLA-A24- (1338-MEL) expressing lines cross-reacted with several HLA-A2-specific MAbs (Table I). Taken together, the data obtained with several HLA-A2-specific MAbs were consistent and suggested a wide variability in expression of HLA-A2 among cell lines. Data collected with 6 MAbs are shown, after normalization, in Figure 1a. MEF values were corrected according to cell diameter to assure that heterogeneous fluorescence was not due to variability in surface area of individual cell lines rather than density of expression per unit of surface area. With few exceptions, correction of MEF by cell-surface area did not alter the overall characteristics of the cell lines (Fig. 1b). Because of their very small diameter, the MEF values for 624-MEL, 1143-MEL, 677-MEL and 1182-MEL were different from the corrected MEF/tumor surface area, suggesting that the HLA-A2 surface density was higher in these cells than predicted by MEF. As there was no firm understanding of the relationship between this correction and the sensitivity to lysis of targets, we excluded these lines from subsequent functional studies.

FIGURE 1.

(a) Variability of expression of HLA class I in melanoma cell lines. Heterogeneity in the staining by 6 MAbs [MA2.1 (white), HO-4 (red), CR11–351 (dark blue), BB7.2 (yellow), KRE 50 (black) and KS-1 (light blue)] recognizing distinct determinants of HLA-A2 antigens of 25 melanoma cell lines derived from HLA-A*0201 patients with metastatic melanoma. Data are expressed as normalized MEF (nMEF) as described “Material and Methods”. A significant proportion of cell lines displayed either loss of expression of HLA-A2 related to genomic loss (first 2 lanes) or greatly reduced level of expression (lanes 3–8). (b) Expression of HLA-A2 detected by MAb MA2.1 in the 25 melanoma cell lines shown in Figure 3a. Data are presented as MEF (◆) as well as MEF corrected for the calculated surface area (MEF/S, gray bars) for each cell line, providing a relative value of HLA-A2 molecule density. In 4 cell lines of very small cell size, the corrected values were quite different from the uncorrected MEF.

Among the melanoma cell lines tested, 7 did not express or only minimally expressed HLA-A2. In a literature review, we noted a discrepancy between the frequency of HLA class I loss reported in tissue specimens and the lower frequency reported for cell lines (Ferrone and Marincola, 1995). Such a discrepancy could partially be attributed to the limited sensitivity of the immunoperoxidase technique used to analyze tissue specimens compared with the more sensitive FACS technology used to analyze cell lines. Low expression of HLA antigens in tissue specimens could, therefore, be interpreted, in a significant proportion of cases, as negative due to low sensitivity of the assay. When cytospins from cell lines characterized by low HLA-A2 expression using FACS analysis were stained with MAb MA2.1, no HLA-A2 expression was detected by immuno-histochemistry, suggesting that this technique is less sensitive than FACS for detection of low amounts of surface expression.

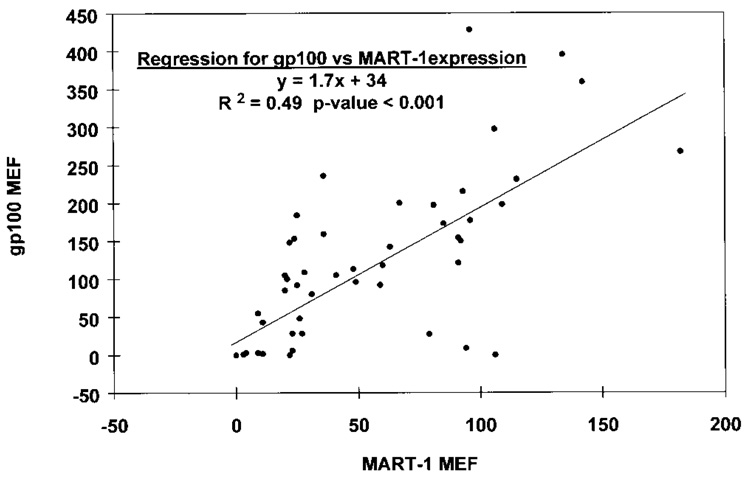

Variability of MAA expression

The intracellular expression of MAAs was analyzed in 25 melanoma cell lines derived from HLA-A*0201 patients and in 21 cell lines from non-HLA-A*0201 patients. SK23-MEL (Pmel17/ gp100- and MART-1/MelanA-positive) and A375-MEL (Pmel17/gp100- and MART-1/MelanA-negative) melanoma cell lines were added to all experiments. These lines gave highly reproducible MEF values (55.7 + 1.4 and 132.5 + 3.8 for MART-1/MelanA and Pmel17/gp100, respectively, in SK23-MEL; 3.67 + 0.5 and 0.9 + 0.3 for MART-1/MelanA and Pmel17/gp100, respectively, in A375-MEL; n = 12). Large variability in expression of both Pmel17/gp100 and MART-1/MelanA was noted (Table II). Furthermore, expression of MART-1/MelanA roughly correlated with expression of Pmel17/gp100 (R² = 0.49, p <0.001; Fig. 2), though lines expressing one or the other MAA were seen. The level of HLA-A2 expression did not correlate with that of MAAs in lines derived from HLA-A*0201 patients (p > 0.05). Similarly, no significant differences were noted in the expression of MAAs in cell lines derived from patients with or without the HLA-A*0201 phenotype (χ², p >0.05; Table II).

TABLE II.

Variability of Melanoma Antigen Expression in Melanoma Cell Lines

| MAA1 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor number | HLA2 A-2 | MA2.13 MEF | MART-1/MelanA |

Pmel17/gp100 |

||

| MEF | % positive | MEF | % positive | |||

| 553B | + | 0 | 22 | 26 | 148 | 88 |

| 1195 | + | 0 | 11 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| 697 | + | 16 | 60 | 60 | 118 | 70 |

| 1376-3 | + | 18 | 79 | 37 | 27 | 8 |

| 501A | + | 31 | 81 | 36 | 197 | 57 |

| 1287 | + | 37 | 63 | 40 | 142 | 72 |

| 1280-1 | + | 46 | 91 | 46 | 121 | 75 |

| 526 | + | 94 | 93 | 56 | 215 | 88 |

| 1286 | + | 107 | 31 | 28 | 80 | 58 |

| 1102 | + | 117 | 11 | 7 | 443 | 25 |

| 624 | + | 122 | 28 | 33 | 109 | 81 |

| 1495 | + | 122 | 49 | 32 | 96 | 40 |

| 836 | + | 132 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 1143 | + | 137 | 96 | 54 | 177 | 81 |

| 1520 | + | 137 | 20 | 5 | 105 | 26 |

| 1317 | + | 152 | 106 | 53 | 297 | 73 |

| 1088 | + | 168 | 25 | 20 | 184 | 65 |

| 1363 | + | 168 | 27 | 30 | 28 | 24 |

| 1479 | + | 168 | 91 | 48 | 154 | 77 |

| 677II | + | 183 | 92 | 30 | 150 | 53 |

| 1199 | + | 183 | 67 | 34 | 200 | 74 |

| 1390 | + | 198 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1182 | + | 229 | 109 | 47 | 198 | 72 |

| 1300 | + | 305 | 142 | 70 | 359 | 91 |

| 1383 | + | 381 | 96 | 40 | 428 | 74 |

| 586 | − | 94 | 54 | 9 | 5 | |

| 1330 | − | 9 | 12 | 55 | 46 | |

| 397 | − | 25 | 26 | 92 | 59 | |

| 1359 | − | 23 | 20 | 6 | 5 | |

| 888 | − | 36 | 31 | 236 | 89 | |

| 1379 | − | 36 | 20 | 159 | 74 | |

| 1351 | − | 182 | 42 | 267 | 72 | |

| 1123 | − | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 297 | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1308 | − | 59 | 22 | 92 | 31 | |

| 1362 | − | 41 | 38 | 105 | 59 | |

| 1338 | − | 115 | 46 | 231 | 61 | |

| 537 | − | 22 | 26 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1335 | − | 23 | 17 | 28 | 21 | |

| 883 | − | 26 | 15 | 48 | 33 | |

| 938 | − | 48 | 42 | 113 | 70 | |

| 1173 | − | 21 | 20 | 100 | 65 | |

| 1241 | − | 106 | 12 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1352 | − | 85 | 54 | 173 | 87 | |

| 1498 | − | 134 | 49 | 395 | 80 | |

| 1274 | − | 9 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| MDA231* | + | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| SK23* | + | 59 | 46 | 139 | 76 | |

| A375* | + | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

Intracellular levels of MAA were analyzed by FACS after permeabilization and fixation of the cell membrane with acetone. Data are presented as MEF (see “Material and Methods”) as well as percentage of positive cells (cells staining with intensity above the 97th percentile with irrelevant isotype-matched MAb).

Predicted HLA-A2 expression according to the HLA phenotype of the patient from whom the cell line was developed, as determined by typing of PBLs.

Amount of HLA-A2 expression by each cell line as detected by MAb MA2.1 (Table I).

MDA 231 (ATCC HTB 26) is an HLA-A2+ breast cancer cell line; SK23 (ATCC HTB 71) is an HLA A1−, A2− and MAA-expressing melanoma cell line; and A375 (ATCC CRL 1619) is another melanoma cell line previously shown to have lost expression of both MART-1 and gp100 message expression (Parker et al., 1994).

FIGURE 2.

Correlation between expression of MART-1/MelanA and Pmel17/gp100 expression (MEF) in 46 melanoma cell lines derived from patients with metastatic melanoma (Surgery Branch, NCI). Data points represent the average of 2 experiments.

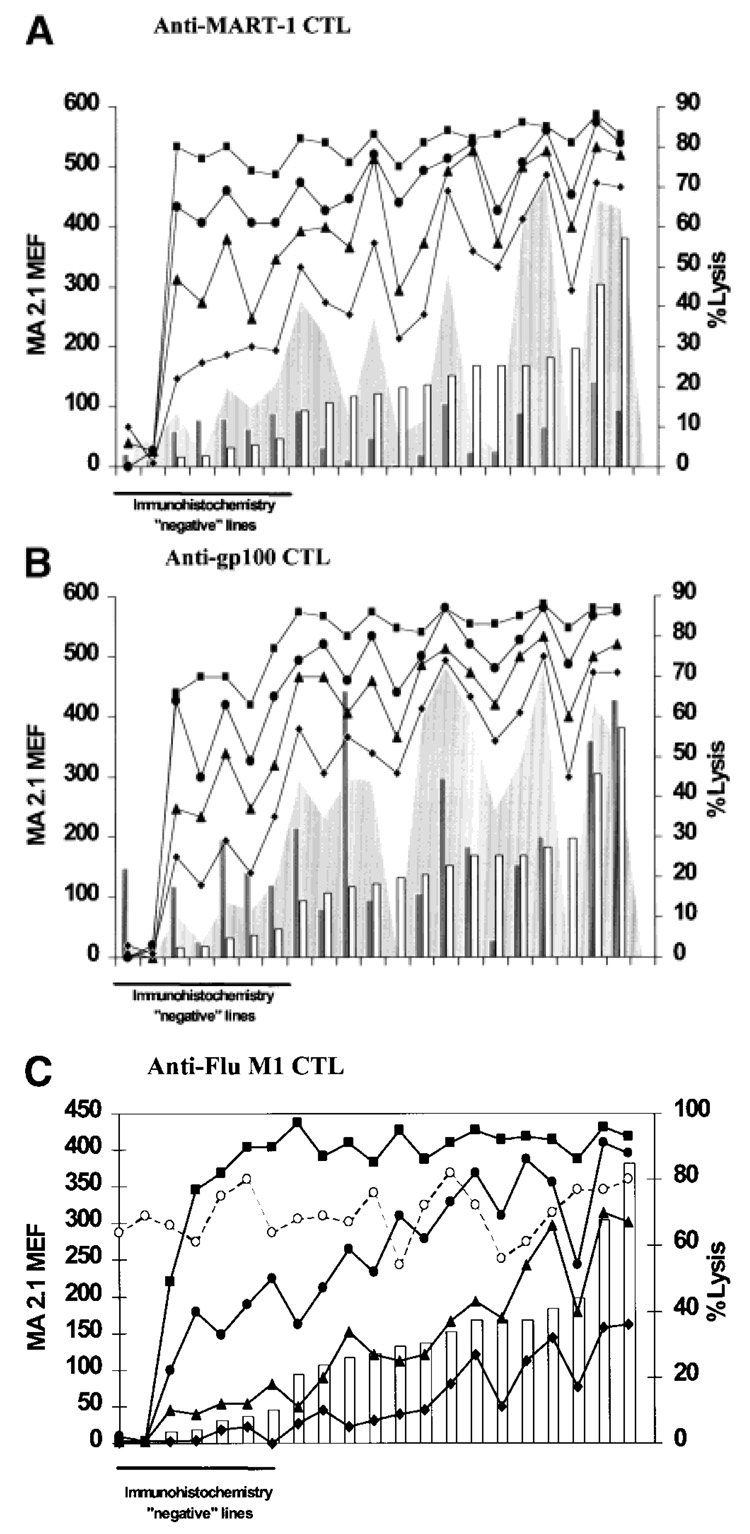

Correlation between HLA-A2 expression and lysis by CTLs

Although the majority of cell lines expressed HLA-A2, the level of expression was heterogeneous. We therefore analyzed the impact on CTL recognition by variability of HLA expression within the range suggested by our results. To investigate the functional significance of allelic down-regulation, we examined melanoma cell lines expressing different amounts of HLA-A2 molecules (including 2 lines with total loss of expression of HLA-A2 and those with levels of expression below the threshold of detection by immuno-histochemistry). When the various cell lines were tested for lysis by MART-1- or gp100-specific CTLs (Fig. 3a,b, respectively), no obvious correlation was noted between HLA-A2 expression and lysis, though lines with low or minimal expression of HLA-A2 were least sensitive to lysis. The lack of absolute correlation could easily be explained by concomitant variability of expression of the relevant MAAs. Several lines, despite high expression of HLA-A2, did not express or expressed poorly the MAA recognized by the specific CTL. The variability of expression of MAAs as co-factors determining the sensitivity to lysis could be demonstrated by loading the cell lines with increasing amounts of exogenous peptide from the relevant MAAs. In this case, the correlation between HLA-A2 expression and sensitivity to lysis by CTLs could easily be restored. To standardize the availability of antigen for each cell line, we also provided each line with increasing amounts of the HLA-A2-restricted Flu M158–66 peptide from the influenza matrix protein and tested these targets for sensitivity to lysis by Flu M158–66-specific, HLA-A*0201-restricted CTLs (Fig. 3c). In this case, killing of cell lines was totally dependent on exogenous antigen as melanomas do not express Flu antigens. To obtain a semi-quantitative prediction of target recognition in relation to available ligand, a polynomial trends analysis was performed, correlating lysis of targets with relative HLA-A2 molecule surface density (rHLA-A2/S = MA2.1 MEF divided by the estimated surface area). Cell lines completely negative for HLA-A2 expression (553-MEL and 1195-MEL) were excluded from the analysis of trends. At high concentrations (1 µg/ml) of target peptide, CTL recognition was similar in all lines independent of the rHLA-A2/S (R² = 0.33) and significantly greater (p = 0.002) than the lysis of HLA-A2-negative controls. At a peptide concentration of 0.1 µg/ml, rHLA-A2/S (R² = 0.59) had wide effects on lysis, which still reached functionally saturating levels in target cells with high rHLA-A2/S. At gradually lower concentrations of ligand (0.01 and 0.001 µg/ml), rHLA-A2/S (R² = 0.66 and 0.68, respectively) still modulated target recognition but could not promote maximal lysis. For all peptide concentrations, lysis of peptide-pulsed targets was significantly greater than lysis of HLA-A2-negative peptide-pulsed controls [p = 0.002 (1 µg/ml), p = 2 ✕ 10−7 (0.1 µg/ml), p = 3 ✕ 10−10 (0.01 µg/ml) and p = 4 ✕ 10−9 (0.001 µg/ml)]. As the concentration of exogenously provided epitope decreased, cell lines with very low expression of HLA behaved as HLA-A2-negative lines. Thus, this analysis suggested that the availability of HLA and that of MAA are co-dependent variables capable of modulating target recognition and that the observed variations occur in a range likely to affect target sensitivity to lysis by CTLs.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of the level of HLA-A2 antigen expression on the recognition of cultured melanoma cells by HLA-A2-restricted CTLs. The cell lines described in Table I (with the exclusion of 624-MEL, 1143-MEL, 677-MEL and 1182-MEL) were derived from HLA-A*0201 melanoma patients and ranked according to different surface expression of HLA-A2 molecules (open bars). Expression of the relevant MAAs (gray bars) is also shown. These lines were tested for sensitivity to lysis by anti-MART-127–35-, anti-gp100209–217- anti-Flu M158–66-specific, HLA-A*0201-restricted CTLs. Cytotoxicity was tested in natural conditions (shaded areas) in the presence of different concentrations of the relevant peptide (■ = 1 µM, ● = 0.1 µM, ▲ = 0.01 µM, ◆ = 0.001 µM). The data summarize the percent of lysis obtained at an effector to target ratio of 10:1 (for MART-1- and gp100-specific CTLs) or 20:1 (for Flu-specific CTLs) and represent the mean of 3 separate experiments. Lysis by LAK cells (40:1 E:T ratio) is similar among different cell lines and is represented by the dashed line and the open circles in (c).

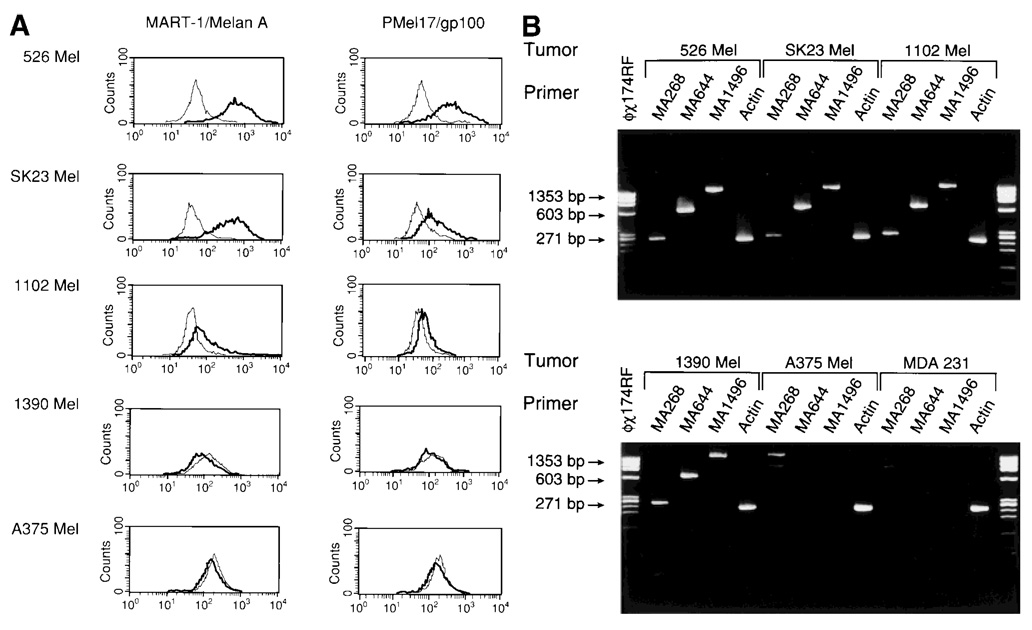

Variability of MAA expression as a cofactor in determining T-cell recognition of melanoma cell targets

To investigate the effect of MAA expression on sensitivity to lysis by CTLs, we selected 526-MEL, 1102-MEL and 1390-MEL. These cell lines are characterized by similar surface density of HLA-A2 (rHLA-A2/S = 20, 21 and 22, respectively) but variable expression of MART-1/Melan A (MEF = 93, 11 and 0, respectively) (Fig. 4a). Two additional, commercially available cell lines, both HLA-A2+, were added to the panel (SK23-MEL and A375-MEL, MART MEF = 62 and 0, respectively). Although MART-1 could not be detected by FACS in A375-MEL or 1390-MEL, these cell lines differ as the former lacks mRNA for MART-1/Melan A while mRNA is detectable in 1390-MEL (Fig. 4b), suggesting that RT-PCR under-estimates the frequency of loss of MAAs.

FIGURE 4.

(a) Intracellular expression of MART-1/Melan A and Pmel17/gp100. MAA expression (bold lines) of 5 tumor lines (526-MEL, SK23-MEL, 1102-MEL, 1390-MEL and A375-MEL) as detected by intracellular FACS analysis (fine lines represent negative control, which is an isotype-matched IgG control plus secondary Goat Anti-mouse FITC (GAMF) MAb). (b) Expression of MART-1/MelanA by RT-PCR. mRNA expression of MART-1/Melan A in 5 melanoma lines (526-MEL, SK23-MEL, 1102-MEL, 1390-MEL and A375-MEL) and in the MDA 231 breast cancer cell line. Three different sets of primers (MA268, MA644 and MA1496) were used, encompassing different sequences of the MART-1/MelanA coding region. The m.w. marker ϕ ✕ 174 RF DNA/HaeIII was used for size confirmation, and β-actin-specific primer pairs were used in each PCR.

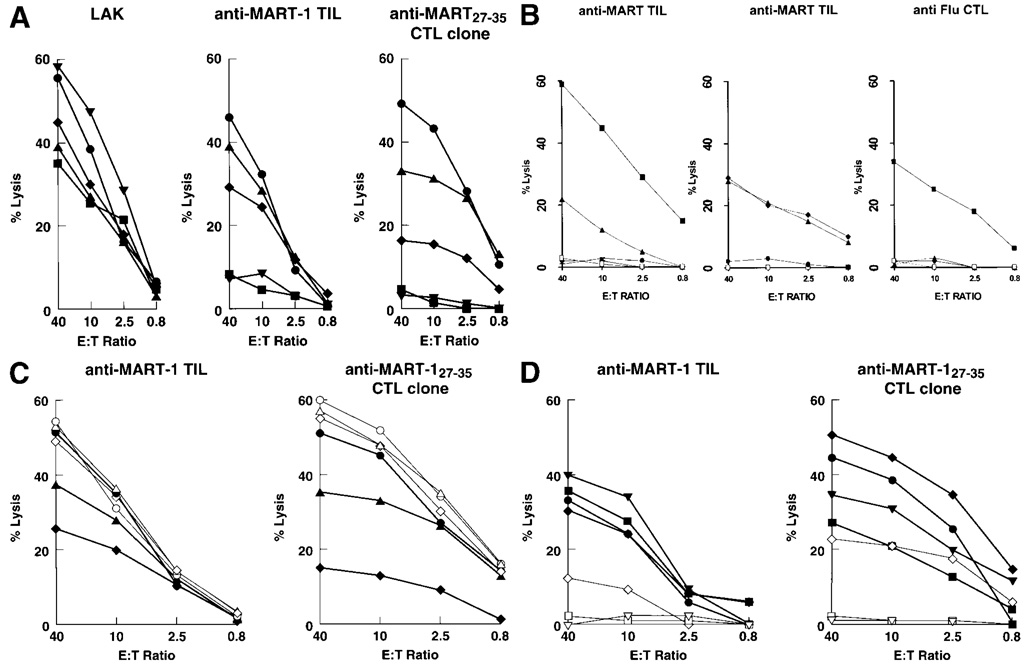

Among cell lines characterized by similar surface density of HLA-A2, levels of MART-1 expression accurately predicted sensitivity to lysis by MART-1-specific effector cells. This correlation was particularly striking when a CTL clone recognizing MART-127–35 was tested (Fig. 5a). An early TIL culture, also specific for MART-1/MelanA, exhibited limited lysis of MART-1-negative (1390-MEL) or poorly expressing (1102-MEL) cell lines. Although a bystander effect responsible for the recognition of these cell lines was not formally ruled out by cloning experiments, the polyclonality of this TIL population was suggested by the recognition of at least another MAA (Fig. 5b). Bystander killing was also unlikely considering the inability of activated TILs to cause lysis of 51Cr-labeled breast cancer cells in the presence of cold melanoma cells (1102-MEL). Furthermore, the inability of Flu-specific CTLs to lyse 51Cr-labeled 1102-MEL in the presence of Flu M158–66-pulsed cold targets suggests that this melanoma cell line is not particularly sensitive to killing by cytokines or other apoptotic factors released by activated CTLs.

FIGURE 5.

(a) Effect of the natural variation of MART-1/Melan A expression on the lysis of melanoma cells by anti-MART-1/Melan A CTLs. The 5 melanoma cell lines (A375, SK23, 1102-MEL, 526-MEL and 1390-MEL) express similar amounts of the HLA-A2 allele but varying amounts of MART-1/MelanA antigen [A375 (▼), MEF 0; SK23 (●), MEF 62; 1102-MEL (◆), MEF 11; 526-MEL (▲), MEF 93; 1390-MEL (■), MEF 0]. These cell lines were tested for lysis by LAK cells (left panel), anti-MART-1/MelanA TILs (center panel) and an anti-MART-127–35 CTL clone originated from a TIL culture (right panel). The data represent the average of 3 experiments (SEM <10% for all data points). Cumulative linear correlation analysis between lysis and MAA expression was significant for TILs and the anti-MART-1 CTL clone at E:T ratios of 40, 10, 2.5 and 0.8:1 (p < 0.01 for all data points). The early TIL culture used for recognition of melanoma targets (TIL 1235) is relatively oligoclonal, recognizes MART-127–35 and does not recognize most Pmel17/gp100-associated epitopes with the exception of gp100154 pulsed on T2 cells. Such specificity was lost in subsequent passages in culture (Kawakami et al., 1995). (b) Lysis of different targets by the early MART-1-specific TIL culture used for the experiments described in Figure 6a,c. In the left panel, the TIL culture was tested against T2 cells pulsed with MART-127–35 (■), gp100154 (▲), gp100209 (●), gp100280 (▼) and unpulsed T2 (□). In the central panel, lysis of MDA231 (breast cancer cell line) alone (□) or in the presence of unlabeled 1102-MEL (●) and lysis of MDA231 pulsed with 1 µM MART-127–35 in the presence (▲) or absence (◆) of unlabeled 1102-MEL. Susceptibility of 1102-MEL to non-specific killing by activated CTLs was tested in the right panel. 1102-MEL was tested for lysis by Flu-specific CTLs: alone (□), alone and pulsed with FluM158–66 peptide (■) and in the presence of unlabeled MDA231 pulsed (▲) or not pulsed (◆) with FluM158–66 peptide. Data are the average of 3 experiments (SEM <10% for all data points). (c) Effect of exogenous MART-1/MelanA peptide on the lysis of melanoma cells by anti-MART-1/Melan A CTLs. Functional saturation of HLA-A2-binding sites equalized the recognition of melanoma targets by anti-MART-1/MelanA CTLs. The 3 melanoma cell lines express similar amounts of HLA-A2 alleles but varying amounts of MART-1 (SK23, MEF 62; 1102-MEL, MEF 11; and 526-MEL, MEF 93). Lysis was compared in the presence of natural processing and presentation of MART-1/MelanAby the cell lines [SK23 (●), 1102-MEL (◆) and 526-MEL (▲)] or after exogenous loading (5 µg/ml) of the same targets with MART-127–35 (open symbols). The anti-MART-1/MelanA TILs (left panel) and anti-MART-127–35 CTL clone originated from a TIL culture (right panel) were used as effectors. Average of 2 experiments, SEM <10 % for all data points. (d) Effect of endogenously processed MART-1/MelanA peptide on the lysis of melanoma cells by anti-MART-1/Melan A CTLs. The 3 melanoma cell lines 1102-MEL, 1390-Mel and A375-MEL express similar amounts of HLA-A2 alleles but varying amounts of MART-1/Melan A. The anti-MART-1/MelanA TILs (left panel) and anti- MART-127–35 CTL clone originated from a TIL culture (right panel) were used as effectors. Lysis was tested against endogenous processing and presentation of MART-1/Melan A by the cell lines after infection with recombinant vaccinia virus encoding MART-1/Melan A (rVV-MART) [A375 (▼), 1390 (■) and 1102 (◆)] or with the irrelevant recombinant vaccinia virus encoding Pmel17/gp100 (rVV-gp100) (open symbols). As a control for maximal lysis in natural conditions (without viral infection), SK23-MEL (●) cells were added to the panel of targets.

Variable recognition of melanoma targets is not due to aberrant HLA class I or antigen processing

Functional saturation of HLA-A2-binding sites by exogenous administration of MART-127–35 (5 µg/ml, Fig. 5c) could restore recognition of melanoma cell lines 526-MEL, 1102-MEL and SK23-MEL to comparable levels. This suggested that the variable lysis observed in natural conditions was not due to aberrant HLA-A2 molecules. This possibility was excluded by direct sequencing of the HLA-A2 heavy chain. Cell lines could also vary in antigen-processing capability. However, endogenous amplification of MART-1/MelanA expression by infection with a recombinant vaccinia virus carrying the MART-1 coding sequence (rVV-MART-1/MelanA, Fig. 5d) equalized lysis of melanoma targets deficient in or lacking MART-1 to that of SK23-MEL.

DISCUSSION

MART-1/Melan A and Pmel17/gp100 are the MAAs most commonly recognized by HLA-A*0201-restricted TILs. Furthermore, in the majority of melanoma patients, the adult T-cell repertoire can easily be shown to include MAA-specific CTLs (Marincola et al., 1996b) and T-cell reactivity can readily be enhanced in vivo by the parenteral administration of MAAepitopes (Cormier et al., 1997). Yet, a paradoxical co-existence occurs in vivo between MAA-specific T cells and their targets.

It is reasonable to postulate that TILs attracted to a tumor site and activated in situ by antigen-presenting cells may be incapable of tumor cell recognition if the antigenic stimulation provided by the targets themselves is inadequate. Inadequacy of tumor cells as targets is generally referred to as “tumor escape”. Among possible mechanisms, loss of HLA (Ferrone and Marincola, 1995) and/or tumor antigens (Marincola et al., 1996a) have been extensively discussed. In general, these mechanisms are analyzed as “all-or-none” occurrences with little attention to quantitative aspects. It is possible, however, that in the natural environment productive engagements between T-cell receptors and HLA–peptide complexes proceed to a point where balance between avidity for binding and availability of ligand is achieved. The effects of down-regulation on sensitivity to lysis were analyzed primarily on the well-characterized model of MART-1/Melan A recognition in the context of HLA-A*0201. This was selected because of the ease of generating CTLs against MART-1 and the high prevalence of HLA-A*0201 in the melanoma population. Altogether, the data show that (i) variation in HLA expression occurs in a limited but significant proportion of melanoma cell lines; (ii) this variability has functional significance because it occurs within a range likely to affect recognition of targets by CTLs, particularly in situations of low MAA expression; and (iii) decreased MAA expression independently determines target susceptibility to lysis by CTLs.

These findings are not in contrast with the possibility that as few as 1 (Sykulev et al., 1996) peptide–MHC complex may be sufficient for recognition by CTLs. Under natural conditions, endogenous peptides compete with more than 1,000 other peptides for binding to specific HLA alleles. Epitope density on the surface of tumor cells is therefore dependent on a number of factors, including the affinity for binding of individual amino acid sequences to a particular HLA allele and their relative availability. It is possible that some proteins are expressed in amounts not sufficient to yield the epitope density required for CTL recognition and peripheral tolerance may ensue. When antigen/HLA availability is sufficient to yield one or more epitope determinants on the cell surface, it is theoretically possible for a cell to be lysed through serial T-cell receptor engagement as an all-or-none phenomenon. However, if a cell population, rather than a single cell, is considered, it is understandable how a proportional relationship still governs the effects of epitope density on lysis. First, a normal distribution predicts that, in borderline conditions of epitope density, some cells will be below and some above the requirements for recognition; second, the statistical probability of productive encounters between epitope and T-cell receptor increases with density.

Due to the extreme heterogeneity of treatments, no clinical correlates could be analyzed comparing cell line characteristics and treatment outcome. Furthermore, we appreciate that as the melanoma cell lines used were propagated in culture, variations in antigen expression may represent variability of adaptation to culture conditions by various melanoma biopsies, which may not necessarily correlate with the melanoma phenotypes in vivo. The ideal study would entail the use of fresh tumor preparations. However, previous attempts to differentiate fibroblast contamination from tumors expressing low or no MAAs have made such quantitative analysis impossible in our hands. Few lines of evidence, however, suggest that variability of MAA/HLA expression detected in cell lines may bear some relevance to the in vivo condition. We and others, in metastatic melanoma, have documented extensive variability of HLA (Ferrone and Marincola, 1995) and MAA expression independent of previous immunotherapy (Cormier et al., 1998; Yoshino et al., 1994), in association with systemic IL-2 treatment (Scheibenbogen et al., 1996) or MAA-specific vaccination (Jager et al., 1996). In a prospective analysis of 222 consecutive melanoma lesions, we noted a wide range of expression of MART-1/Melan A and Pmel17/gp100. Approximately 50% of specimens showed evidence of MAA down-regulation, and in 10% MART-1/Melan A could not be detected because of either loss of expression or expression below the threshold of detection of the immunoperoxidase technique. It is theoretically possible that the conditions regulating recognition of target in the in vitro model discussed here could fall within the range of abnormalities described in vivo. We are completing a study in which cytospin preparations from fine needle aspirates (FNAs) of metastatic lesions were tested for MAA and HLA expression by immuno-histochemistry. Data were correlated with expression of the same MAAs by cell lines derived from the FNAs and analyzed by FACS and PCR. At high frequency, the aberrations documented in the FNAs matched those of the cell lines (data not shown).

This analysis does not address the question of whether the aberrations are due to in vivo selection. We have previously noted loss of HLA class I expression in 5 melanoma patients after immunotherapy (Restifo et al., 1996), and Jager et al. (1996) have suggested decreased expression of MAAs in tissues after CTL-mediated clinical responses. Nisticó et al. (1997) reported reduced expression of the erbB-2 proto-oncogene recognized by HLA-A2-restricted CTLs in HLA-A2-expressing breast cancer lesions, suggesting that lesions expressing HLA alleles other than HLA-A2 may be under less severe immune pressure. In our study, the level of HLA-A2 expression had no bearing on that of MAA expression in lines derived from HLA-A*0201 patients. Furthermore, no significant differences were noted in MAA expression among cell lines derived from patients with or without the HLA-A2 phenotype. The lack of such correlation, therefore, does not support in vivo immunologial pressure as the cause of the heterogeneity observed in cell lines. However, tumor escape from immune recognition is different from identification of aberrations in expression of HLA and/or MAA. It is possible that tumor cells lose expression of such molecules in relation to neoplastic de-differentiation independently from immune pressure. Still, loss or down-regulation of such molecules will make those cells unsuitable targets for class I-restricted CTLs.

In summary, our results demonstrate that melanoma cells are heterogeneous for expression of HLA and MAA. This natural variation occurs in a range affecting sensitivity to lysis of target cells and may help us to understand CTL–target interactions in vitro. Furthermore, the gradualness of this heterogeneity suggests a potential mechanism for progressive adjustment of tumor cells to a putative, immunologically unfavorable environment. Finally, the strictly quantitative relationship between HLA/antigen expression and lysis by HLA class I-restricted CTLs suggests a general model of peripheral tolerance in which the pacific co-existence of epitope-specific CTLs and related targets is allowed.

REFERENCES

- Chen Y-T, Stockert E, Tsang S, Coplan KE, Old LJ. Immunophenotyping of melanomas for tyrosinase: implications for vaccine development. Proc. nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:8125–8129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier JN, Hijazi YM, Abati A, Fetsch P, Bettinotti M, Steinberg SM, Rosenberg SA, Marincola FM. Heterogeneous expression of melanoma-associated antigens (MAA) and HLA-A2 in metastatic melanoma in vivo. Int. J. Cancer. 1998;75:517–524. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980209)75:4<517::aid-ijc5>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier JN, Salgaller ML, Prevette T, Barracchini KC, Rivoltini L, Restifo NP, Rosenberg SA, Marincola FM. Enhancement of cellular immunity in melanoma patients immunized with a peptide from MART-1/MelanA. Cancer J. Sci. Am. 1997;3:37–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrone S, Marincola FM. Loss of HLA class I antigens by melanoma cells: molecular mechanisms, functional significance and clinical relevance. Immunol. Today. 1995;16:487–494. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido F, et al. Proceedings of the XII HLA International Workshop. France: EDK, Sèvres; 1997. HLA and cancer. [Google Scholar]

- Jager E, Ringhoffer M, Karbach J, Arand M, Oesch F, Knuth A. Inverse relationship of melanocyte differentiation antigen expression in melanoma tissues and CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell responses: evidence for immunoselection of antigen-loss variants in vivo. Int. J. Cancer. 1996;66:470–476. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960516)66:4<470::AID-IJC10>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami Y, Eliyahu S, Jennings C, Sakaguchi K, Kang X, Southwood S, Robbins PF, Sette A, Appella E, Rosenberg SA. Recognition of multiple epitopes in the human melanoma antigen gp100 by tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes associated with in vivo tumor regression. J. Immunol. 1995;154:3961–3968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marincola FM, Hijazi YM, Fetsch P, Salgaller ML, Rivoltini L, Cormier J, Simonis TB, Duray PH, Herlyn M, Kawakami Y, Rosenberg SA. Analysis of expression of the melanoma associated antigens MART-1 and gp100 in metastatic melanoma cell lines and in in situ lesions. J. Immunother. 1996a;19:192–205. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199605000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marincola FM, Rivoltini L, Salgaller ML, Player M, Rosenberg SA. Differential anti-MART-1/MelanACTLactivity in peripheral blood of HLA-A2 melanoma patients in comparison to healthy donors: evidence for in vivo priming by tumor cells. J. Immunother. 1996b;19:266–277. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199607000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marincola FM, Shamamian P, Alexander RB, Gnarra JR, Turetskaya RL, Nedospasov SA, Simonis TB, Taubenberger JK, Yannelli J, Mixon A, Rosenberg SA. Loss of HLA haplotype and B locus down-regulation in melanoma cell lines. J. Immunol. 1994;153:1225–1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisticó P, Moulese M, Mammi C, Benevolo M, Delbello D, Rublu O, Gentile FP, Botti C, Ventura I, Natali PG. Low frequency of ErbB-2 protooncogene overexpression in human leukocyte antigen A2 positive breast cancer patients. J. nat. Cancer Inst. 1997;89:319–321. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.4.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker KC, Bednarek MA, Coligan JE. Scheme for ranking potential HLA-A2 binding peptides based on independent binding of individual peptide side-chains. J. Immunol. 1994;152:163–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Player MA, Barracchini KC, Simonis TB, Rivoltini L, Arienti F, Castelli C, Mazzocchi A, Belli F, Marincola FM. Differences in frequency distribution of HLA-A2 sub-types between American and Italian Caucasian melanoma patients: relevance for epitope specific vaccination protocols. J. Immunother. 1996;19:357–363. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199609000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restifo NP, Marincola FM, Kawakami Y, Taubenberger J, Yannelli JR, Rosenberg SA. The loss of functional b2-microglobulin in metastatic melanomas from five patients undergoing immunotherapy. J. nat. Cancer Inst. 1996;88:100–108. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.2.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivoltini L, Baracchini KC, Viggiano V, Kawakami Y, Smith A, Mixon A, Restifo NP, Topalian SL, Simonis TB, Rosenberg SA, Marincola FM. Quantitative correlation between HLA class I allele expression and recognition of melanoma cells by antigen specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3149–3157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg SA. Cancer vaccines based on the identification of genesencoding cancer regression antigens. Immunol. Today. 1997;18:175–182. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)84664-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibenbogen C, Weyers I, Ruiter DJ, Willhauck M, Bittinger A, Keiholz U. Expression of gp100 in melanoma metastases resected before and after treatment with IFNα and IL-2. J. Immunother. 1996;19:375–380. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199609000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykulev Y, Joo M, Vturina I, Tsomides TJ, Eisen HN. Evidence that a single peptide–MHC complex on a target cell can elicit a cytolytic T cell response. Immunity. 1996;4:565–571. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino I, Peoples GE, Goedegebuure PS, Maziarz R, Eberlein TJ. Association of HER2/neu expression with sensitivity to tumor-specific CTL in human ovarian cancer. J. Immunol. 1994;152:2393–2400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]