The scope of arsenic contamination of drinking water, and the threat it poses to global health, is much more widespread than previously believed, new research suggests.

As many as 140 million people worldwide may have been exposed to drinking water with arsenic contamination levels higher than the World Health Organization's (WHO) provisional guideline of 10 μg/L, says University of Cambridge geographer Peter Ravenscroft.

“Natural arsenic pollution is a global phenomenon. We have documented more than 230 occurrences in 70 countries on all continents, except Antarctica,” Ravenscroft told CMAJ in an email interview. “In large areas of the world, water has apparently not been tested for arsenic, and we believe that more cases will be discovered in the next few years. We estimate that in recent decades about 140 million people worldwide have been exposed to drinking water containing more than 10 μg/L of arsenic.”

Ravenscroft told the annual conference of the Royal Geographic Society in London this summer that the international response to the problem of arsenic-contaminated water, though substantial, has been woefully inadequate given the scale of the problem and will undoubtedly lead to an epidemic of cancer in the future.

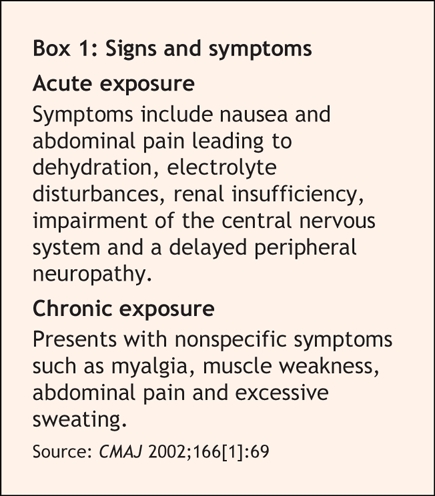

Arsenic poisoning leads to higher rates of lung, bladder and skin tumours, as well as heart and other lung conditions (Box 1).

Box 1.

The WHO is equally convinced that the arsenic problem is assuming global dimensions. “The WHO sourcebook of arsenic contamination [now in preparation] estimates that, considering just geogenic sources, exclusive of volcanogenic sources, there are at least 40 countries worldwide with arsenic concentrations in groundwater higher than 10 μg/L,” spokesperson Gregory Härtl told CMAJ in an email interview.

Arsenic contamination first surfaced as a major health issue in Bangladesh (CMAJ 2002;166[12]:1578) and the West Bengal region of India, where high concentrations of arsenic were discovered after being brought down from the surrounding hills for generations.

Higher arsenic levels have since been found in natural aquifiers that serve as a supply of water in dozens of countries on all 5 continents. Those include Canada, where leachings from mine tailings have resulted in high levels in Nova Scotia, as well as the United States, because of similar leachings and widespread use of arsenic as a pesticide to spray crops.

Nations in South and East Asia now account for over one-half of all cases of arsenic poisoning and researchers fear the health risk will only be exacerbated because residents consume large amounts of rice grown in affected areas. “The arsenic problem now has gone well beyond Bangladesh and India,” says Dipankar Chakraborti, director (research) at the Jadavpur University School of Environmental Studies in Kolkata. “This is acute in Southeast Asia where ground water withdrawal is maximum. In India, before 2000, we knew about groundwater arsenic contamination only in West Bengal. Now in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, as well as in Nepal, millions are drinking arsenic contaminated water.”

Chakraborti said that while there is growing awareness of the arsenic problem, there are still many existing wells, and proposed new ones, that go untested. “Due to temporal variability more tubewells are getting unsafe. A lot of new tubewells have been drilled without testing.”

Ravenscroft argues widespread testing of all wells should be undertaken by governments to determine potential health risk to communities.

He also noted the arsenic problem is partially a function of previous international aid policies. For years, aid agencies encouraged the digging of wells as an alternative to the consumption of surface water, which was often contaminated with bacteria. “This was good but they failed to test for arsenic, heavy metals and fluoride. First, suitable water testing facilities were generally lacking until the 1990's in some developing countries. Second, scientists failed to either predict the occurrence of arsenic on geological grounds or test for it following the precautionary principle. Another factor is the failure of medical doctors to identify the dermatological symptoms of arsenic poisoning. A notable exception was Dr. K.C. Saha who tracked the cause of arsenical skin lesions to water wells in West Bengal in 1983.”

David Polya, senior lecturer at the University of Manchester's School of Earth, Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, says that while Bangladesh's arsenic problem was exacerbated by drilling new wells, “it is easy to look back in hindsight and criticize those organizations and individuals engaged in this activity. But it is also worth bearing in mind that the massive program of well construction in Bangladesh, for example, has, along with other interventions, made massive improvements to countrywide mortality rates, particularly amongst young children who are very susceptible to water-borne diseases.”

Solutions are problematic because the wells are so widely dispersed and the health challenges plentiful, Polya adds. “Many of the countries most deeply impacted are amongst the poorer nations of the world — this impacts remediation both from the point of view of restrictions on funding but also because many of these countries have other major health issues also to address,” he told CMAJ in an email interview.

While Ravenscroft and Chakraborti argue that international aid agencies haven't shown much initiative to combat the arsenic problem, Härtl defended the WHO's efforts, saying the agency “is working to strengthen national health systems capacity to respond to the arsenic problem, especially in Southeast Asia. Concerning water supply, WHO is advocating for a holistic approach, because in developing a response to the arsenic crisis, the potential for risk substitution from other hazards must be considered.”

“There are water-related health risks associated with all forms of water supply and in reducing one water-related health risk another may be substituted, sometimes of greater magnitude. Water supply options should be selected within an overall risk management framework of Water Safety Plans,” Härtl added. — Sanjit Bagchi MBBS, Kolkata, India

Figure. Arsenic, once the preferred poison of kings, now threatens as many as 140 million people worldwide as a result of contamination of drinking water. In Bangladesh, it has eroded from the hills into the aquifers that serve as the nation's primary source of water. Photo by: Davexplore / iStockphoto