Abstract

A novel vector has been constructed for the constitutive luminescent tagging of gram-negative bacteria by site-specific integration into the 16S locus of the bacterial chromosome. A number of gram-negative pathogens were successfully tagged using this vector, and the system was validated during murine infections of living animals.

Bioluminescent imaging (BLI) has become a valuable tool for studying bacterial infections in real time in small animal models. Various species of gram-negative bacteria have been rendered luminescent using a variety of approaches. The species include Escherichia coli (3, 4, 11, 12), Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (1, 2), Yersinia enterocolitica (7), Brucella melitensis (9), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (5), and Citrobacter rodentium (13). In E. coli, both firefly luciferase (3, 4) and the bacterial lux system (11) have been used to provide the luminescent signal. However, the use of firefly luciferase is somewhat limited in that the substrate for the reaction (luciferin) must be added exogenously. For this reason, most researchers favor the use of the lux operon from Photorhabdus luminescens, in which the substrate for the luminescence reaction is synthesized endogenously, allowing accurate real-time in vivo tracking of bacterial localization. To date, the lux operon has been provided either on a plasmid (2-4, 11, 12) or via transposon mutagenesis (1, 5, 7, 9, 13). However, both of these methods have significant limitations. When animals are infected with strains carrying a bioluminescence plasmid and monitored over several days, there is the possibility of plasmid loss, resulting in underrepresentation of bacterial infection. When transposon mutagenesis is utilized, a bank of transposon integrants must be screened for strains with sufficient light emission, and the integrating transposon has the potential to influence local gene expression, bacterial fitness, and bacterial pathogenesis.

We therefore sought to develop a method to reproducibly label gram-negative bacteria by site-directed chromosomal integration using a constitutively expressed luminescence reporter system.

We recently reported the construction of pPL2luxPhelp, a chromosomal integration vector containing a synthetic lux operon derived from Photorhabdus luminescens (where Phelp indicates a highly expressed Listeria promoter) (8) for real-time monitoring of Listeria monocytogenes infections in mice (10). Our construct was based on combining the lux operon with the backbone of pGh9::ISS1, a thermosensitive E. coli/gram-positive shuttle vector which integrates randomly into the bacterial chromosome as a consequence of the presence of ISS1 (6). To construct p16Slux, a fragment containing the constitutive luxPhelp construct was cloned in pGh9::ISS1, yielding pGhlux. The ISS1 element was then excised and replaced with a fragment of the E. coli DH10B 16S rRNA genes, obtained by PCR using KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase (Merck, Nottingham, United Kingdom) primers 16S_fwd_Econew (5′-CTGATGAATTCCAGGTGTAGCGGTGAAATG-3′) and 16S_rev_XhoI (5′-CTGATCTCGAGGGCGGTGTGTACAAGG-3′). The resulting vector, p16Slux (Fig. 1A), was then transformed into various gram-negative bacteria by electroporation using standard protocols.

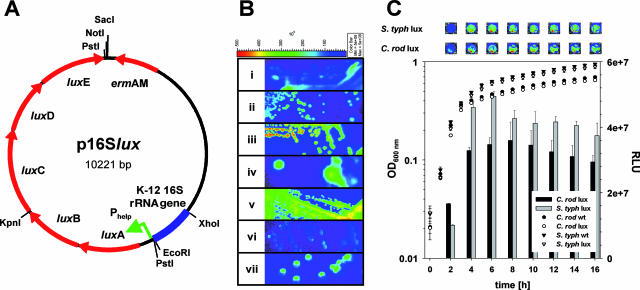

FIG. 1.

(A) Plasmid map of p16Slux with relevant restriction sites and arrangement of the E. coli DH10B 16S sequence (blue), the Phelp promoter region (green arrow), and luxABCDE (red arrows). (B) Gram-negative strains tagged by chromosomal integration of p16Slux (i, E. coli DH10B::p16Slux; ii, C. rodentium ICC169::p16Slux; iii, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium UK-1::p16Slux; iv, P. aeruginosa PAO1::p16Slux; v, E. sakazakii DPC6440::p16Slux; vi, S. flexneri 2a ATCC 700930::p16Slux; vii, Y. enterocolitica NCTC13174::p16Slux). The color bar indicates bioluminescence signal intensity (in photons s−1 cm−2). Strains were grown on LB agar plates containing erythromycin under nonpermissive conditions and imaged using the Xenogen IVIS100 imaging system. min, minimum; max, maximum. (C) Growth (symbols) and luminescence (bars) of wild-type (wt) and lux-tagged strains of C. rodentium ICC169 (C. rod) and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium UK-1 (S. typh) on LB medium. Data for luminescence are presented as mean RLU ± standard deviations of results for four wells, and the results from one representative of three independent experiments are shown. The top panel shows representative wells containing the indicated strain in LB broth at the indicated time points.

Transformants were obtained by plating cells on LB agar containing erythromycin (at 500 μg/ml, except with P. aeruginosa PAO1, for which 800 μg/ml was used) and incubating them for 24 to 48 h at the permissive temperature (30°C). Eryr colonies were checked for light emission using a Xenogen IVIS100 imaging system (Xenogen, Alameda, CA), and the presence of p16Slux was confirmed by mini-prep and restriction analyses. Positive clones were incubated aerobically in LB broth containing erythromycin at 30°C overnight, diluted 1:1,000 into fresh medium containing erythromycin, and incubated overnight at the nonpermissive temperature (42°C). Dilutions were then plated on LB agar containing erythromycin and incubated at 42°C. After the initial transformation with p16Slux, bacteria were maintained under permissive conditions, which allowed for plasmid replication. When we shifted culture conditions to the nonpermissive temperature while at the same time maintaining antibiotic pressure, p16Slux was forced to integrate into a 16S locus of the bacterial chromosome by homologous recombination. This is an event statistically predicted to occur at a very low frequency. Moreover, the pGh9::ISS1 vector backbone used in the current system was designed to integrate primarily in a single copy (6). While it is highly unlikely that more than one copy of the plasmid integrates per bacterium, in cases where exact levels of luminescence are critical (e.g., in comparisons of wild-type and mutant strains), relative levels of luminescence or copy numbers of integrants should be verified. Eryr colonies were checked for light emission, and the integration of p16Slux was confirmed by PCR using primers 16S_rev_XhoI and 16S_fwd_int (5′- ATTAGCTAGTAGGTGGGGTAACGGCTCACCTAGG-3′). 16S_fwd_int anneals upstream of 16S_fwd_Econew in the 16S rRNA gene sequence and yields a 1,150-bp PCR fragment only if p16Slux is integrated at the correct site in the chromosome. By using this protocol, the following organisms were rendered bioluminescent: E. coli DH10B, C. rodentium ICC169, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium UK-1, P. aeruginosa PAO1, Enterobacter sakazakii DPC6440, Shigella flexneri 2a ATCC 700930, and Y. enterocolitica NCTC13174 (Fig. 1B). In all lux-tagged strains, plasmid integration was stable in the absence of antibiotic for at least 50 generations. All lux-labeled strains were tested for differences in growth on complex media in a SpectraMax M2, 96-well plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). At the time points indicated in Fig. 1, luminescence was measured in relative light units (RLU, in photons s−1) with the IVIS100 imaging system. As shown in Fig. 1C for C. rodentium and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium UK-1, none of the tagged strains exhibited a significant difference from the wild-type strain in growth rate and final optical density at 600 nm on LB media (Fig. 1C and data not shown).

All gram-negative strains presented here produced intense luminescence (∼1 × 107 to 5 × 107 RLU) in LB broth in 96-well plates (Fig. 1C and data not shown). Luminescence in the gram-negative strains was approximately 10-fold higher than the luminescence observed in L. monocytogenes EGDe::pPL2luxPhelp, which harbors the same luxPhelp construct as a single-copy chromosomal integration (10). Also, luminescence in the gram-negative strains was about 10-fold higher than that in the gram-positive strains containing p16Slux replicating as a plasmid (data not shown). Additionally, while luminescence in L. monocytogenes (10) and other gram-positive bacteria (data not shown) decreased dramatically in stationary phase, luminescence in all gram-negative bacteria tested remained relatively stable throughout the entire growth curve (Fig. 1C and data not shown). Whether these differences are due to the availability of the substrate of the reaction or to differences in the intracellular conditions remains to be elucidated.

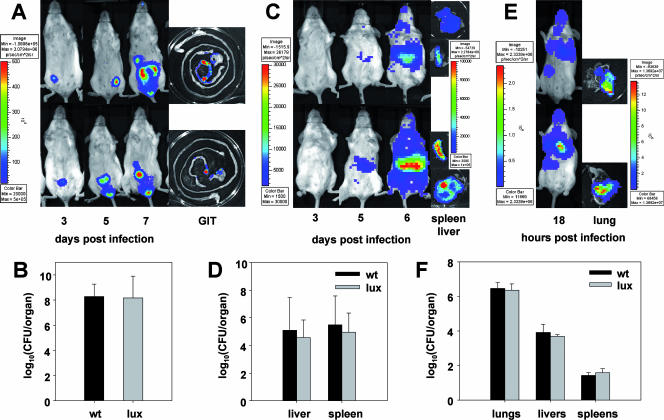

To assess the functionality of the Phelp-driven expression of luxABCDE in gram-negative bacteria in vivo, three of the labeled strains were tested in murine models of infection in 6- to 8-week-old conventional female BALB/c mice and compared to their wild-type strains. C. rodentium, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, and P. aeruginosa were chosen as models for noninvasive intestinal, invasive intestinal, and invasive pulmonary pathogens, respectively. Animals were kept in a conventional animal colony, and all experiments were approved by the animal ethics committee of University College Cork. Animals were infected by gavage (C. rodentium and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium) or intranasally (P. aeruginosa) with bacteria from overnight cultures washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Doses used were 2 × 109 CFU/animal in 100 μl of PBS for C. rodentium, 1 × 107 CFU/animal in 100 μl PBS for S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, and 1 × 106 CFU/animal in 10 μl PBS for P. aeruginosa. At various time points during infection (Fig. 2), animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and imaged in the IVIS system. After the final image acquisition, the animals were euthanized and their organs dissected, imaged, homogenized, and plated for determination of bacterial loads. Infections of C. rodentium were detected in vivo by luminescence as early as day 3 postinfection (p.i.) and peaked at day 7 p.i. (Fig. 2A). Luminescence (Fig. 2A) and plate counts (Fig. 2B) from the dissected organs indicated the typical localization of C. rodentium in the cecum and distal colon (14). No bacteria were detected in other organs. S. enterica serovar Typhimurium gastrointestinal infections were not detectable on day 6 p.i. At this stage, luminescence (Fig. 2C) and plate counts (Fig. 2D) indicated that systemic infection of livers and spleens had occurred. P. aeruginosa rapidly colonized the lungs (Fig. 2E) and, 18 h after inoculation, translocated and caused systemic infections of livers and spleens as shown by plate counting (Fig. 2F). Also, low levels of luminescence were detected from livers but not from spleens (data not shown). No difference in bacterial load in the organs was observed between the three lux-tagged strains and the wild-type strains, indicating that the p16Slux system does not influence bacterial pathogenesis in these models (Fig. 2B, D, and F). Luminescence from the dissected organs correlated highly with bacterial loads for all organs and all three luminescent strains tested (Table 1).

FIG. 2.

BLI results for living animals and dissected gastrointestinal tracts, livers, spleens, and lungs (A, C, and E) and quantification of bacterial loads in dissected organs (B, D, and F) from animals infected with C. rodentium ICC169::p16Slux (A and B), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium UK-1::p16Slux (C and D), P. aeruginosa PAO1::p16Slux (E and F), or the relevant wild-type control. All animal trials were performed at least twice (five mice in each group). BLI results for two representative animals from one trial and their dissected organs are shown. The color bars indicate bioluminescence signal intensity (in photons s−1 cm−2). Data for bacterial loads are shown as mean log10 numbers of CFU per organ ± standard deviations from all organs of one representative trial (five mice for each organ). min, minimum; max, maximum; wt, wild type; p, photons; sr, steradian.

TABLE 1.

Statistical analysis of the correlation between luminescence and bacterial loads from dissected organs of BALB/c mice infected with lux-tagged bacteriaa

| Strain | Organ | No. of organs | Pearson's r | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. rodentium ICC169::p16Slux | Cecum | 9 | 0.95 | <0.001 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium | Liver | 10 | 0.99 | <0.001 |

| UK-1::p16Slux | Spleen | 10 | 0.99 | <0.001 |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1::p16Slux | Lung | 10 | 0.91 | <0.001 |

Luminescence was measured in RLU per organ, and bacterial loads were measured in numbers of CFU per organ.

We further tested whether p16Slux is also functional as an integrating vector in gram-positive bacteria. p16Slux was successfully transformed into Lactococcus lactis NZ9000 and Streptococcus mutans UA159, giving rise to luminescent bacteria which could be maintained under antibiotic pressure and growth at the permissive temperature (30°C). However, all attempts to integrate the plasmid into the chromosomes of these bacteria failed (data not shown). Integration of pGhlux, which is inserted at random sites in the chromosome, was successful in L. lactis NZ9000 (data not shown). Replacing the E. coli DH10B 16S sequence in p16Slux with the 16S sequence of L. lactis NZ9000 did not promote integration of the resulting plasmid, p16SLlalux, into the chromosome of gram-positive bacteria (data not shown). By contrast, p16SLlalux was successfully integrated into the chromosomes of all gram-negative strains tested (data not shown), indicating that the 16S homology is not the limiting factor for integration. We postulate that gram-positive bacteria are more sensitive to the disruption of a copy of the 16S rRNA gene than gram-negative bacteria and suggest that the current p16Slux system is not suitable for application in gram-positive bacteria.

In summary, we have developed p16Slux, an integrating plasmid system for tagging a range of gram-negative bacteria with the constitutive expression of high levels of luminescence to allow in vivo BLI in murine infection models. We demonstrated the functionality of the system with a wide range of gram-negative bacteria, including some species which have not previously been labeled using bioluminescence, such as S. flexneri and E. sakazakii. p16Slux offers the possibility of simply and consistently labeling different strains and mutants of various gram-negative bacteria with the same efficient expression of luminescence. The system has the advantages of site-specific chromosomal integration and stability in the absence of antibiotic without the need for extensive screening of transposon mutant libraries.

Acknowledgments

Our research was supported by the Irish Government under the National Development Plan (2000 to 2006) and by Science Foundation Ireland through a Centre for Science Engineering and Technology award to the Alimentary Pharmabiotic Centre. H.M. and F.O. were supported in part by grants awarded by Science Foundation Ireland (SFI 02/IN.1/B1261 and 04/BR/B0597 to F.O.) and the Health Research Board (RP/2004/145 and RP/2006/271 to F.O.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 August 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burns-Guydish, S. M., I. N. Olomu, H. Zhao, R. J. Wong, D. K. Stevenson, and C. H. Contag. 2005. Monitoring age-related susceptibility of young mice to oral Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection using an in vivo murine model. Pediatr. Res. 58:153-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Contag, C. H., P. R. Contag, J. I. Mullins, S. D. Spilman, D. K. Stevenson, and D. A. Benaron. 1995. Photonic detection of bacterial pathogens in living hosts. Mol. Microbiol. 18:593-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jawhara, S., and S. Mordon. 2004. In vivo imaging of bioluminescent Escherichia coli in a cutaneous wound infection model for evaluation of an antibiotic therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3436-3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jawhara, S., and S. Mordon. 2006. Monitoring of bactericidal action of laser by in vivo imaging of bioluminescent E. coli in a cutaneous wound infection. Lasers Med. Sci. 21:153-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadurugamuwa, J. L., L. Sin, E. Albert, J. Yu, K. Francis, M. DeBoer, M. Rubin, C. Bellinger-Kawahara, T. R. Parr, Jr., and P. R. Contag. 2003. Direct continuous method for monitoring biofilm infection in a mouse model. Infect. Immun. 71:882-890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maguin, E., H. Prévost, S. D. Ehrlich, and A. Gruss. 1996. Efficient insertional mutagenesis in lactococci and other gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 178:931-935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maoz, A., R. Mayr, G. Bresolin, K. Neuhaus, K. P. Francis, and S. Scherer. 2002. Sensitive in situ monitoring of a recombinant bioluminescent Yersinia enterocolitica reporter mutant in real time on Camembert cheese. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5737-5740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qazi, S. N. A., E. Counil, J. Morrissey, C. E. D. Rees, A. Cockayne, K. Winzer, W. C. Chan, P. Williams, and P. J. Hill. 2001. agr expression precedes escape of internalized Staphylococcus aureus from the host endosome. Infect. Immun. 69:7074-7082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajashekara, G., D. A. Glover, M. Banai, D. O'Callaghan, and G. A. Splitter. 2006. Attenuated bioluminescent Brucella melitensis mutants GR019 (virB4), GR024 (galE), and GR026 (BMEI1090-BMEI1091) confer protection in mice. Infect. Immun. 74:2925-2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riedel, C. U., I. R. Monk, P. G. Casey, D. Morrissey, G. C. O'Sullivan, M. Tangney, C. Hill, and C. G. M. Gahan. 2007. Improved luciferase tagging system for Listeria monocytogenes allows real-time monitoring in vivo and in vitro. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3091-3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rocchetta, H. L., C. J. Boylan, J. W. Foley, P. W. Iversen, D. L. LeTourneau, C. L. McMillian, P. R. Contag, D. E. Jenkins, and T. R. Parr, Jr. 2001. Validation of a noninvasive, real-time imaging technology using bioluminescent Escherichia coli in the neutropenic mouse thigh model of infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:129-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siragusa, G. R., K. Nawotka, S. D. Spilman, P. R. Contag, and C. H. Contag. 1999. Real-time monitoring of Escherichia coli O157:H7 adherence to beef carcass surface tissues with a bioluminescent reporter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1738-1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiles, S., S. Clare, J. Harker, A. Huett, D. Young, G. Dougan, and G. Frankel. 2004. Organ specificity, colonization and clearance dynamics in vivo following oral challenges with the murine pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. Cell. Microbiol. 6:963-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiles, S., K. M. Pickard, K. Peng, T. T. MacDonald, and G. Frankel. 2006. In vivo bioluminescence imaging of the murine pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. Infect. Immun. 74:5391-5396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]