Abstract

The role of the stress response regulator σB (encoded by sigB) in directing the expression of selected putative and confirmed cold response genes was evaluated using Listeria monocytogenes 10403S and an isogenic ΔsigB mutant, which were either cold shocked at 4°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth for up to 30 min or grown at 4°C in BHI for 12 days. Transcript levels of the housekeeping genes rpoB and gap, the σB-dependent genes opuCA and bsh, and the cold stress genes ltrC, oppA, and fri were measured using quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR. Transcriptional start sites for ltrC, oppA, and fri were determined using rapid amplification of cDNA ends PCR. Centrifugation was found to rapidly induce σB-dependent transcription, which necessitated the use of centrifugation-independent protocols to evaluate the contributions of σB to transcription during cold shock. Our data confirmed that transcription of the cold stress genes ltrC and fri is at least partially σB dependent and experimentally identified a σB-dependent ltrC promoter. In addition, our data indicate that (i) while σB activity is induced during 30 min of cold shock, this cold shock does not induce the transcription of σB-dependent or -independent cold shock genes; (ii) σB is not required for L. monocytogenes growth at 4°C in BHI; and (iii) transcription of the putative cold stress genes opuCA, fri, and oppA is σB independent during growth at 4°C, while both bsh and ltrC show growth phase and σB-dependent transcription during growth at 4°C. We conclude that σB-dependent and σB-independent mechanisms contribute to the ability of L. monocytogenes to survive and grow at low temperatures.

Listeria monocytogenes is a food-borne pathogen that can cause an invasive human illness and that can multiply at temperatures ranging from −0.4 to 45°C (20, 24, 39). Most human listeriosis cases appear to be caused by consumption of refrigerated ready-to-eat foods that permit L. monocytogenes growth (37). As the infectious dose for L. monocytogenes appears to be high and as initial contamination of processed foods generally occurs at low levels (37), the ability of this organism to grow during refrigerated storage appears to be critical in enabling this pathogen to reach high enough numbers in foods to cause human disease. Consequently, a detailed understanding of the physiology of L. monocytogenes during cold shock and cold growth is needed to allow for the design of effective strategies to prevent or minimize L. monocytogenes growth on refrigerated ready-to-eat foods and to reduce the number of human listeriosis cases.

Mechanisms that L. monocytogenes may use to adapt to low-temperature conditions include the expression of cold shock proteins (CSPs) and cold acclimation proteins (CAPs), changes in membrane lipid composition, and the uptake of osmolytes and oligopeptides (3-5, 8, 10, 29). CSPs and CAPs are defined as proteins showing increased expression during temperature downshift from an organism's optimal growth temperature to a lower temperature; in general, CAPs continue to be expressed at high levels during prolonged cold exposure. In Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, a number of CSPs have been characterized as RNA chaperones that facilitate the initiation of translation (22, 23). While CSPs and CAPs have also been identified in L. monocytogenes (4, 32), the functions of many of these proteins have not yet been clearly defined. One L. monocytogenes CSP that is highly synthesized during low-temperature exposure is ferritin (Fri; encoded by fri) (21). Fri is involved in hydrogen peroxide resistance and has been hypothesized to be required for iron acquisition (31). However, the specific contributions of Fri to L. monocytogenes cold growth and survival are unknown.

In both L. monocytogenes and B. subtilis exposed to low temperatures, compatible low-molecular-weight solutes can be transported into the bacterial cell and can accumulate to high concentrations (1, 11). In L. monocytogenes, carnitine and glycine betaine are the predominant compatible solutes that accumulate during low-temperature exposure and growth (5, 8). These compatible solutes have been shown to stimulate L. monocytogenes growth at low temperatures in defined media (1, 2, 5) and function as osmoprotectants (2, 5, 8, 16, 27). Meat and dairy products are rich in carnitine, while glycine betaine is abundant in plants and shellfish (30, 42); therefore, L. monocytogenes has access to these compatible solutes in many different foods. The carnitine ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporter system, encoded by the opuC operon, and the glycine betaine porter II, encoded by gbuABC, are responsible for the uptake of the respective compatible solutes into L. monocytogenes (16, 27). In addition to compatible solutes, oligopeptides can be transported into bacterial cells and can accumulate to high concentrations in L. monocytogenes exposed to low temperatures (10, 38). Oligopeptide uptake in L. monocytogenes is mediated by an oligopeptide permease (encoded by oppA) which can transport peptides that are generally ≤8 residues (10, 38). Characterization of an oppA null mutant has shown that the peptide transporter encoded by oppA is required for L. monocytogenes growth at 5°C in brain heart infusion (BHI) medium (10).

Previous studies of the regulation of gene expression during exposure to low temperatures in L. monocytogenes (7) and the closely related nonpathogenic bacterium B. subtilis (11) have provided preliminary evidence that the stress-responsive alternative sigma factor σB (encoded by sigB) contributes to the regulation of gene expression in gram-positive bacteria exposed to low temperatures. Specifically, a B. subtilis sigB null mutant showed reduced survival at a low temperature (11); in addition, transcription of the B. subtilis σB regulon appears to be induced at low temperatures (11). In L. monocytogenes, σB-dependent transcription is induced when the organism enters stationary phase or is subjected to environmental stress conditions, including carbon starvation and acid, osmotic, or oxidative stress (6, 15, 17, 25, 41). Becker et al. (7) reported that σB also appears to contribute to the adaptation of stationary-phase L. monocytogenes cells to growth at low temperatures. In addition, a number of L. monocytogenes genes with confirmed (e.g., opuCA, ltrC, and gbu) or putative (e.g., fri) roles in cold growth and adaptation (2, 21, 28, 43, 44) have been shown to be at least partially σB dependent (12, 17, 25, 31). We thus hypothesized that σB contributes to the regulation of gene expression in L. monocytogenes exposed to cold temperatures. To test this hypothesis, we used quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) as well as promoter mapping strategies to characterize the transcription of selected putative and confirmed cold response genes in an L. monocytogenes ΔsigB null mutant and its isogenic parent strain that had been either (i) cold shocked at 4°C in BHI broth for 30 min or (ii) grown for 12 days at 4°C in BHI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

The L. monocytogenes serotype 1/2a strain 10403S (9) and an isogenic sigB null mutant (ΔsigB), FSL A1-254 (41), were used throughout this study. Cells were grown in BHI (Difco, Sparks, MD) at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm). Log-phase cells (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.4) of both strains were used for all experiments, unless otherwise stated.

Exposure to centrifugation stress.

Initial experiments were performed to evaluate the effect of centrifugation on transcript levels of the target genes studied here. Briefly, 5 ml of log-phase L. monocytogenes 10403S (OD600 = 0.4) were pelleted in a Sorvall RT6000B swing bucket rotor centrifuge (Kendro, Asheville, NC) at 2,190 × g for 5 min. Bacterial cells were then resuspended in 250 μl of BHI broth, and cells were added to either (i) 5 ml of prechilled (4°C) BHI or (ii) 5 ml of prewarmed (37°C) BHI broth. Total RNA was isolated from log-phase cells prior to centrifugation as well as from bacterial cells immediately after exposure (i.e., within <30 s) to BHI at 4 or 37°C.

Cold shock and low-temperature growth conditions.

To allow for the rapid exposure of L. monocytogenes cells to 4°C without prior centrifugation, we initially measured the cooling rate of 8 ml of prewarmed (37°C) BHI broth added to a prechilled (4°C) sterile stainless steel (type 18-8) pan (17.5 cm by 10.8 cm by 5.1 cm; Polarware, Sheboygan, WI). As this protocol allowed for rapid cooling (see Results), it was subsequently used for cold shock experiments that were designed to rapidly expose L. monocytogenes cells to 4°C. Briefly, 8 ml of log-phase cultures of L. monocytogenes 10403S or the ΔsigB strain were cold shocked by adding the culture to a prechilled 4°C pan. A control sample was added to a prewarmed (37°C) stainless steel pan. Bacterial cells were used for RNA isolation as described below either immediately after addition to the covered pan (representing an initial exposure time of <30 s [time zero]) or at 15 or 30 min after addition to the pan. Cells collected from the log-phase culture (37°C) before addition to the stainless steel pans were used as a no-treatment control. Three independent cold shock experiments were carried out for both L. monocytogenes 10403S and the ΔsigB strain.

For cold growth experiments, log-phase cultures of L. monocytogenes 10403S and ΔsigB were used to inoculate 10 ml of prechilled BHI (4°C) in 18- by 150-mm disposable culture tubes (borosilicate glass tubes; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) to a starting OD600 of 0.15 ± 0.05. Cells were incubated at 4°C without shaking for 12 days, and optical densities were measured every day. Bacterial cells were collected for RNA isolation on days 3, 6, 9, and 12. Three independent replicates of this experiment were performed. In addition, bacterial numbers on days 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 were determined by spread plating on BHI agar plates.

Total RNA isolation.

Total RNA isolation was performed using the RNeasy midi kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) essentially as described by Kazmierczak et al. (26). Briefly, 2 volumes of RNAprotect bacterial reagent (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) were added to L. monocytogenes cells at the time points specified above, followed by cell lysis using QIAGEN′s protocol for “enzymatic lysis with mechanical disruption,” except that sonication was performed instead of bead beating as previously described (26). Two DNase treatments (60 min each) were performed on each spin column using 175 μl RNase-free DNase (QIAGEN). After elution from the purification columns, total RNA was precipitated at −80°C and resuspended in RNase-free TE buffer (pH, 8.0; 10 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA) (Ambion, Austin, TX) immediately before qRT-PCR. Total nucleic acid concentrations (ng/μl) and purity were evaluated using absorbance readings (A260 divided by A230 and A260 divided by A280) determined on a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Rockland, DE).

qRT-PCR.

qRT-PCR was performed using a 5′ nuclease (TaqMan) assay format. qRT-PCR primers and TaqMan probes for the housekeeping genes rpoB and gap as well as for opuCA and bsh have previously been reported (33, 35). Primer Express 1.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used to design oligonucleotide primers and TaqMan probe sets for fri, oppA, and ltrC (Table 1). TaqMan probes containing the quencher QSY7 or the minor groove binder and a 3′ nonfluorescent quencher were synthesized by Megabases, Inc. (Evanston, IL) or Applied Biosystems.

TABLE 1.

Primers and TaqMan probes used for this studya

| Gene | Primers | TaqMan probeb |

|---|---|---|

| fri | 5′-CGGCGGAAGCCCATTC-3′ | FAM-5′-TATAAGGCGCTTCTTCTACGCTGGCATTTTCT-3′-QSY7 |

| 5′-CTAAGTCTTCCATTAATTGATCCATTGT-3′ | ||

| ltrC | 5′-CCAGGCATTCTTGCAAAACTAA-3′ | FAM-5′-CCGTTCACACATTCCTTGA-3′-MGB-NFQ |

| 5′-GATGGCGCCGACAATGTC-3′ | ||

| oppA | 5′-GAAGATGCAAAATGGTCAAACG-3′ | FAM-5′-CCTGTAACTGCAAATGACTAT-3′-MGB-NFQ |

| 5′-TGCACGACGCCATGAGTAAA-3′ |

qRT-PCR was performed using TaqMan one-step RT-PCR master mix reagent (Applied Biosystems) and the ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) as described previously by Kazmierczak et al. (26). Control reactions without RT were performed for each template to quantify genomic DNA contamination. As described in detail by Sue et al. (35), standard curves for each target gene were included for each assay to allow absolute quantification of cDNA levels. Data were analyzed using the ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system software (Applied Biosystems) as previously described (35).

RACE-PCR.

A 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was used as previously described (25) to map the transcriptional start sites for selected genes. Briefly, mRNA was reverse transcribed using a gene-specific primer (GSP1) and tailed with dCTP using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase. Poly(dC)-tailed cDNA was amplified using a nested gene-specific primer (GSP2) and a poly(G/I) primer (provided in the RACE-PCR kit) using AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems) and a touchdown PCR protocol. Gene-specific primers included ltrC GSP1 (5′-AACTGCGTGCTTTTGATTCT-3′), ltrC GSP2 (5′-AGGCACTTTGTTTTTCTACCA-3′), oppA GSP1 (5′-AATTAGTGCGCTTTCTGTCAA-3′), oppA GSP2 (5′-CCTCCGCATGCTACCAAGAC-3′), opuCA PsigA GSP1 (5′-ATCGATAACTAATTTCCCTAACTA-3′), and opuCA PsigA GSP2 (5′-CAGTGTTACATTCAAACGGAAGT-3′). In addition, previously described gene-specific primers for opuCA were used (25). PCR products were separated on 3% agarose gels; DNA fragments of interest were purified using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (QIAGEN) and cloned into pCR2.1 using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). Plasmids containing an insert were sequenced at the Cornell University Bioresource Center (Ithaca, NY). Sequences were analyzed using Lasergene v6.0 (DNAstar, Inc., Madison, WI).

Statistical analyses.

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine if the OD600 values of L. monocytogenes 10403S and the ΔsigB strain grown at 4°C were affected by strain (parent strain or ΔsigB strain), replicate, or time of incubation was performed with the Proc general linear model (GLM) function of SAS (version 8e; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) using a split-plot model. Bacterial strain and replicate were designated category variables. Day of incubation was treated as a continuous variable in the ANOVA. Distortion of the ANOVA by multicollinearity of the linear and quadratic terms for time of incubation was minimized by centering the incubation times using a mathematical transformation (19). The day of incubation time was transformed as follows: day transformed = day of storage − [(last storage day − first storage day)/2]. This transformation made the data set orthogonal with respect to time. The whole plot error term (strain by replicate interaction) was used as the error term to test the significance of strain and replicate. The model was considered significant if the F test had a P of <0.05.

Transcript levels for target genes determined by qRT-PCR data were log10 transformed and then normalized to the geometric mean of rpoB and gap transcript levels as previously described (26); log10 ratios less than 0 thus indicate that the target gene had lower transcript levels than the average transcript levels for rpoB and gap, which are highly transcribed. Statistical analysis of qRT-PCR data was performed as described by Kazmierczak et al. (26) using a GLM with multiple comparisons performed using Tukey's studentized range test (implemented as least-square [LS] means in SAS). Cell collection date, RNA collection date, and qRT-PCR assay date were used as blocking factors in a mixed-effects model for selected genes if these factors were found to be significant in the initial GLM analysis. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Centrifugation increases transcript levels for σB-dependent genes, requiring the development of a centrifugation-independent protocol for cold shock exposure.

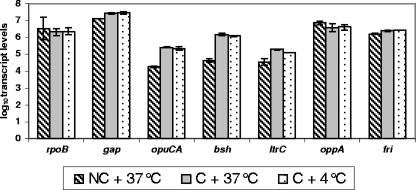

In initial experiments, we found that the transcript levels of the σB-dependent genes opuCA, bsh, and ltrC were consistently higher for cells collected immediately after a centrifugation step (regardless of whether the cells were resuspended in BHI tempered at 4 or 37°C) than for cells collected for RNA isolation immediately before RNA stabilization (Fig. 1). On the other hand, centrifugation did not show any apparent effect on transcript levels for fri and genes that are not σB dependent (rpoB, oppA, and gap). As these preliminary results were consistent with observations by Chaturongakul and Boor (13), who also found increased transcript levels for σB-dependent genes after centrifugation, we devised a cold shock exposure protocol for L. monocytogenes that did not include a centrifugation step. Specifically, 8 ml of log-phase L. monocytogenes cells grown in BHI at 37°C was pipetted into prechilled (4°C) sterile stainless steel pans, and the temperature of the broth was measured at 1-min intervals for 15 min. The temperature of the broth reached 4°C after 6 min (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), indicating that this protocol was suitable for creating cold shock exposure in L. monocytogenes cells that had been grown at 37°C, without a centrifugation step.

FIG. 1.

Log-transformed absolute transcript levels for selected genes before and after centrifugation of L. monocytogenes. Transcript levels were determined by qRT-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from (i) log-phase L. monocytogenes parent strain cells grown at 37°C prior to centrifugation, (ii) log-phase L. monocytogenes parent strain cells centrifuged and immediately exposed for <30 s to fresh BHI prewarmed to 37°C, and (iii) log-phase L. monocytogenes parent strain cells centrifuged and immediately exposed to fresh BHI prechilled to 4°C for <30 s. Values shown represent the averages of results from qRT-PCR assays performed on two independent RNA collections. Error bars indicate the data range. NC, no centrifugation; C, centrifugation.

Cold shock exposure to 4°C for 30 min does not induce the transcription of ltrC, oppA, opuCA, or fri but induces the σB-dependent transcription of bsh.

To determine if σB-dependent transcription is activated during cold shock, log-phase cells of L. monocytogenes 10403S and the ΔsigB strain that had been grown at 37°C were cold shocked by rapidly cooling them in prechilled (4°C) sterile stainless steel pans with cell collection for qRT-PCR at the initial time point (0 min, i.e., <30 s after addition to the pan) and after 15 and 30 min. As a control, an equal aliquot of the same culture was also transferred to prewarmed (37°C) pans. Bacterial cells were also collected for qRT-PCR from the culture immediately before cells were added to the pans. Transcript levels did not differ significantly (P was >0.05 as determined by ANOVA using data for all genes before exposure and after exposure for 0 min to 37°C) between cells before exposure and immediately after exposure to 37°C (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Normalized, log-transformed transcript levels for opuCA, bsh, ltrC, oppA, and fri during the cold shock at 4°C and during control exposure to 37°C of the L. monocytogenes parent strain and a ΔsigB mutant. Transcript levels were determined by qRT-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from the (i) log-phase L. monocytogenes parent strain (10403S) and ΔsigB strain before exposure (directly from the culture [DFC]); (ii) parent strain and ΔsigB strain cold shocked at 4°C in prechilled stainless steel pans for <30 s (0 min), 15 min, and 30 min; and (iii) parent strain and ΔsigB mutant exposed to 37°C in prewarmed stainless steel pans for <30 s (0 min), 15 min, and 30 min. Transcript levels for each gene were log transformed and normalized to the geometric mean of the transcript levels for the housekeeping genes rpoB and gap. Values shown represent the averages of results from qRT-PCR assays performed on three independent RNA collections; error bars show standard deviations. Results of statistical analyses using ANOVA are detailed in the text and shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Overall, opuCA and bsh transcript levels were consistently higher in L. monocytogenes 10403S than in the ΔsigB mutant (Fig. 2), and the transcript levels for these two genes were significantly affected by the factor “strain” (P < 0.0001, GLM analysis), consistent with previous observations that these two genes are σB dependent (34). In addition, ltrC transcript levels were also consistently higher in 10403S than in the ΔsigB mutant (Fig. 2) and were significantly affected by the factor “strain” (P < 0.05, GLM analysis), indicating that ltrC transcription is also σB dependent. Interestingly, bsh transcript levels increased over time in parent strain cells exposed to 4°C, with transcript levels at both 15 and 30 min after cold exposure significantly (P was <0.05 as determined by LS means analysis of 4°C data for the parent strain) higher than transcript levels at 0 min at 4°C, indicating induction of this σB-dependent gene during cold shock at 4°C. The factor “time” significantly affected bsh transcript levels in 10403S at 4°C, while there was no significant effect of time on bsh transcript levels in the ΔsigB mutant at 4°C or on bsh levels in either the ΔsigB mutant or the parent at 37°C (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Combined, these results indicate that bsh induction at 4°C is σB dependent (as no induction was observed in the ΔsigB mutant) and occurs during cold shock but not at 37°C.

The factor “temperature” had a significant effect only on fri and oppA transcript levels (P < 0.0001, mixed-effects analysis). The mean-normalized, log-transformed transcript levels for fri and oppA at 4°C (−0.49 and −0.24, respectively [averages of values at all three time points, i.e., 0, 15, and 30 min]) were higher than the mean transcript levels for these genes at 37°C (−0.79 and −0.42, respectively, for fri and oppA [averages of results at all three time points]). Transcript levels for cells prior to exposure (−0.49 and −0.19 for fri and oppA, respectively) were similar to those for cells exposed to 4°C but higher than those for cells exposed to 37°C. Thus, rather than being upregulated during exposure to 4°C, transcript levels for these two genes appear to be lower in cells exposed to 37°C.

Expression of the putative cold stress genes opuCA, fri, and oppA is predominantly σB independent during growth at 4°C, as shown by mRNA transcript levels.

While OD600 measurements and cell enumeration showed that L. monocytogenes 10403S and the ΔsigB strain have similar growth patterns over 12 days in BHI at 4°C (Fig. 3), the OD600 values for the ΔsigB strain were consistently slightly lower than the OD600 values for the isogenic parent strain (10403S). While statistical analysis confirmed that there was a significant effect (P was 0.01 as determined by GLM analysis using a split-plot model) of the factor “strain” (i.e., the parent strain or ΔsigB strain) on OD600 measurements of L. monocytogenes cells grown at 4°C, statistical analyses of cell enumeration data performed in triplicate indicated no significant effect of “strain” on L. monocytogenes 10403S and ΔsigB strain numbers for bacteria grown at 4°C for 12 days (Y. C. Chan, Y. Hu, S. Chaturongakul, K. D. Files, B. Bowen, K. J. Boor, and M. Wiedmann, submitted for publication). Thus, the parent and the ΔsigB strain do not appear to differ in their abilities to grow in BHI at 4°C.

FIG. 3.

Growth of the L. monocytogenes parent strain 10403S and the ΔsigB strain at 4°C. The OD600s of the L. monocytogenes parent strain 10403S and ΔsigB mutant were measured during growth at 4°C for 12 days. Data on the left y axis show the average OD600 values from five independent experiments; error bars indicate standard deviations. Data on the right y axis show the average cell counts for L. monocytogenes strain 10403S and the ΔsigB mutant determined in one experiment.

In order to determine the contributions of σB to the transcription of L. monocytogenes genes during growth at 4°C, transcript levels for selected L. monocytogenes genes were determined using qRT-PCR with 10403S and the ΔsigB mutant grown at 4°C for 3, 6, 9, and 12 days (Fig. 4). Analysis of normalized transcript levels showed that bsh and ltrC transcript levels were consistently lower in the ΔsigB mutant than in the parent strain (Fig. 4); statistical analysis using GLM also showed that the factor “strain” (i.e., 10403S or the ΔsigB mutant) has a significant effect on bsh (P < 0.0001) and ltrC (P < 0.005) transcript levels (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). opuCA, fri, and oppA transcript levels were similar in the parent strain and the ΔsigB mutant (Fig. 4) and were not affected by the factor “strain” (P > 0.05, GLM analysis). For opuCA, this finding was initially surprising as this gene has been identified as σB dependent in multiple studies (12, 13, 16, 17, 25, 26, 34, 35). The results were subsequently explained by identification of a σB-independent promoter that is active at 4°C and located upstream of opuCA (see below).

FIG. 4.

Normalized, log-transformed transcript levels of rpoB, gap, opuCA, bsh, ltrC, oppA, and fri for the L. monocytogenes parent strain and the ΔsigB strain grown at 4°C. Transcript levels were determined by qRT-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from the L. monocytogenes parent strain 10403S and the ΔsigB strain grown in BHI at 4°C for 3, 6, 9, and 12 days. Transcript levels for each gene were log transformed and normalized to the geometric mean of the transcript levels for the housekeeping genes rpoB and gap. Values shown represent the averages of results of qRT-PCR assays performed on three independent RNA collections; error bars show standard deviations. Results of statistical analyses using ANOVA are detailed in the text and shown in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

Transcript levels for the σB-dependent genes bsh and ltrC were significantly affected by the factor “time” (P was <0.001 as determined by GLM analysis using data for the parent and the ΔsigB strain [see Table S2 in the supplemental material]), although opuCA, fri, and oppA transcript levels were not. bsh transcript levels in the parent strain grown for 6, 9, and 12 days at 4°C were significantly higher (P < 0.05, LS means analysis) than those of the parent strain grown for only 3 days at 4°C. ltrC transcript levels in the parent strain showed similar trends, even though only ltrC transcript levels at days 9 and 12 were significantly higher (P < 0.05, LS means analysis) than those at day 3. These findings for these two σB-dependent genes are consistent with observations that σB is a stationary-phase alternative sigma factor (6, 34) and indicate that both σB activity and σB-dependent transcription increase as L. monocytogenes cells enter stationary phase at 4°C.

Initial analysis of absolute transcript levels for rpoB and gap in L. monocytogenes cells grown at 4°C showed that transcript levels for rpoB were significantly affected by the factors “time” and “strain” (with transcript levels at days 9 and 12 being lower than transcript levels at days 3 and 6), while transcript levels for gap were not significantly affected by these two factors. While we still elected to normalize transcript levels for all target genes (i.e., oppA, ltrC, bsh, fri, and opuCA) to the geometric means of the rpoB and gap transcript levels, providing (i) for more robust normalization due to the use of two rather than one housekeeping gene and (ii) for comparisons with other data that used the same two housekeeping genes for normalization (e.g., see reference 26), we also reanalyzed our data using ltrC and bsh transcript levels normalized to gap only (as ltrC and bsh were the only two genes that showed significant differences in transcript levels). The results from both analyses were consistent; in both analyses, ltrC and bsh transcript levels were significantly (P < 0.05) affected by the factors “time” and “strain.”

ltrC and fri are transcribed from at least one σB-dependent promoter as revealed by RACE-PCR.

To further test whether transcription of the cold stress genes ltrC, fri, and oppA is σB dependent, a RACE-PCR protocol was used to map transcriptional start sites and identify the promoters for these genes. For ltrC, we found a single σB-specific transcript (i.e., a transcript was amplified in 10403S but was absent in the ΔsigB strain) (Fig. 5A). Sequencing of this σB-specific ltrC RACE-PCR product allowed us to map the transcriptional start site for this transcript and identified a putative σB-dependent promoter (Fig. 5B) that closely matches the σB consensus promoter described by Kazmierczak et al. (25) but that differs from the putative σB-dependent ltrC promoter previously identified by visual inspection of the DNA sequence upstream of this gene (25). The −10 region of this promoter is located approximately 40 nucleotides upstream of the ltrC start codon (Fig. 5B). For fri, RACE-PCR identified a σB-independent transcript (i.e., a transcript was amplified in both 10403S and the ΔsigB strain) (Fig. 5A) as well as a σB-specific transcript (i.e., a transcript was amplified in 10403S but was absent from the ΔsigB strain) (Fig. 5A). Despite repeated attempts, we were unable to clone the σB-specific RACE-PCR product for fri, most likely due to the presence of a larger quantity of a σB-independent RACE-PCR product of similar size. However, Olsen et al. (31) recently used primer extension to identify a putative σB-dependent promoter upstream of fri, which is consistent with the size of the RACE-PCR product observed here. For oppA, RACE-PCR identified only a σB-independent transcript (i.e., a transcript that was amplified in both 10403S and the ΔsigB strain).

FIG. 5.

RACE-PCR and promoter sequences of ltrC and fri. RACE-PCR was performed using total RNA collected from L. monocytogenes parent strain (10403S) and ΔsigB cells cold shocked at 4°C for 30 min. (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of RACE-PCR products for ltrC (lanes 2 to 6) and fri (lanes 8 to 12). Lanes 1 and 7, pGEM DNA size marker (Promega, Madison, WI); lanes 2 and 8, PCR of untailed L. monocytogenes parent strain cDNA (negative control); lanes 3 and 9, PCR of poly(dC)-tailed parent strain cDNA; lanes 4 and 10, PCR of untailed L. monocytogenes ΔsigB cDNA (negative control); lanes 5 and 11, PCR of poly(dC)-tailed ΔsigB cDNA; lanes 6 and 12, negative-control PCR with no cDNA. Arrows indicate σB-dependent transcripts (i.e., transcripts that were detected in RNA from the parent strain but not in RNA from the ΔsigB strain). The contrast of the ltrC gel picture was enhanced to visualize DNA fragments. (B) σB promoter sequence for ltrC determined by RACE-PCR. The −35 and −10 regions are underlined. The triangle indicates the transcriptional start site determined by RACE-PCR.

opuCA is transcribed from a σA-dependent promoter during growth at a low temperature and in the absence of σB expression.

Our data indicated that opuCA transcription in L. monocytogenes grown at 4°C was σB independent, while opuCA transcription during cold shock (our data reported here) and during growth at 30 and 37°C (25, 34) was σB dependent, so we used RACE-PCR to map opuCA transcriptional start sites in 10403S and ΔsigB cells grown to stationary phase (day 9) at 4°C or grown to stationary phase (OD600 = 2.0) at 37°C. For L. monocytogenes 10403S and the ΔsigB strain grown at 4°C, RACE-PCR identified a single σB-independent transcript (i.e., transcripts were amplified in both 10403S and the ΔsigB strain) but no σB-dependent transcript, indicating σB-independent transcription of opuCA at 4°C. Sequencing of this RACE-PCR product identified a putative σA-dependent promoter upstream of this transcriptional start site (Fig. 6B). For stationary-phase L. monocytogenes grown at 37°C, RACE-PCR identified a σB-specific transcript (i.e., the transcript was amplified in 10403S but was absent from the ΔsigB strain) (Fig. 6A) as well as a σB-independent transcript (found only in the ΔsigB strain), which matched the size of the σB-independent transcript amplified in L. monocytogenes grown at 4°C. Sequencing of these PCR products identified transcriptional start sites that corresponded to the putative σA-dependent promoter identified in cells grown at 4°C as well as to the σB-dependent promoter previously identified upstream of opuCA (25). As the σB-independent RACE-PCR product was not detected in L. monocytogenes 10403S grown at 37°C (possibly due to the abundance of the σB-dependent transcript in this strain, which might be amplified preferentially during cDNA synthesis relative to the larger σA-dependent transcript), we designed gene-specific RACE-PCR primers (opuCA PsigA GSP1 and GSP2) to exclusively reverse transcribe and amplify the σA-dependent opuCA transcript. RACE-PCR with these primers yielded a σB-independent RACE-PCR product (which mapped to the same σA-dependent promoter identified above) in both L. monocytogenes 10403S and the ΔsigB strain cells grown to stationary phase at 37°C. Thus, the σA-dependent promoter identified upstream of opuCA also contributes to opuCA transcription at 37°C in a L. monocytogenes strain with a functional σB.

FIG. 6.

RACE-PCR and promoter sequence of opuCA. RACE-PCR was performed using total RNA collected from the L. monocytogenes parent strain and ΔsigB strain after growth to stationary phase (day 9) at 4°C or after growth to stationary phase (OD600 = 2.0) at 37°C and previously described opuCA-specific primers (25). (A) Agarose gel electrophoresis of RACE-PCR products for opuCA in L. monocytogenes grown to stationary phase in BHI at 37°C (lanes 2 to 5) or at 4°C (lanes 7 to 10). Lanes 1 and 6, pGEM DNA size marker; lanes 2 and 7, PCR of untailed L. monocytogenes parent strain (10403S) cDNA (negative control); lanes 3 and 8, PCR of poly(dC)-tailed parent strain cDNA; lanes 4 and 9, PCR of untailed ΔsigB strain cDNA (negative control); lanes 5 and 10, PCR of poly(dC)-tailed ΔsigB cDNA; lane 11, negative-control PCR with no cDNA. (B) σB and σA promoter sequences for opuCA as determined by RACE-PCR. The −35 and −10 regions for the σB- and σA-dependent promoters are double and single underlined, respectively. Triangles indicate transcriptional start sites for opuCA determined by RACE-PCR in the L. monocytogenes parent strain (▵) and ΔsigB mutant ( ) grown at 37°C and for the parent strain and ΔsigB mutant grown at 4°C (▴).

) grown at 37°C and for the parent strain and ΔsigB mutant grown at 4°C (▴).

DISCUSSION

To determine the role of σB during cold shock and growth at a low temperature, L. monocytogenes 10403S and an isogenic ΔsigB null mutant were (i) exposed to cold shock conditions or (ii) grown at 4°C over 12 days. qRT-PCR using mRNA isolated from these cells was used to measure transcript levels for selected cold stress genes and σB-dependent genes and to map, using RACE-PCR, transcriptional start sites of selected genes. We confirmed that centrifugation rapidly induces σB-dependent transcription, which necessitated the use of centrifugation-independent protocols to evaluate the contributions of σB to transcription during cold shock. Our data indicate that (i) σB is not required for L. monocytogenes growth at 4°C in BHI; (ii) transcription of the cold stress genes ltrC and fri is at least partially σB dependent; (iii) while σB activity is induced during 30 min of cold shock at 4°C, this cold shock does not induce the transcription of σB-dependent or -independent cold shock genes; and (iv) expression of the putative cold stress genes opuCA, fri, and oppA is σB independent during growth at 4°C, while the cold shock gene ltrC as well as bsh shows growth phase and σB-dependent transcription during growth at 4°C.

Centrifugation rapidly induces σB-dependent transcription.

Consistently with a previous report (13), we found that transcript levels of the σB-dependent genes opuCA, bsh, and ltrC increased following centrifugation. Centrifugation prior to RNA stabilization should thus be avoided in experiments aimed at evaluating the effects of σB on gene transcription. The inclusion of a centrifugation step may result in underestimation of σB's contributions to gene transcript levels or phenotypic measurements if both control and experimental treatments are exposed to centrifugation, as σB-dependent transcription would also be induced in the control. On the other hand, experiments where only the treatment group is exposed to centrifugation may overestimate the contribution of σB, as centrifugation rather than the intended treatment could induce σB activity. Consequently, the cold shock procedures used in the study reported here differed from those used in previous studies that included a centrifugation step (29, 36, 40). As previous studies have shown that activation of σB under stress conditions occurs rapidly (i.e., <5 min [35]), we also chose to avoid cold shock protocols in which bacterial cultures are cooled in glass flasks, as these protocols produce a slow “temperature downshift” from 37°C to 4°C, which can take 30 min or more (14, 18). To allow for rapid cold shock exposure of L. monocytogenes without centrifugation, we thus developed a cold shock protocol that entailed rapid cooling of bacterial cultures in sterile, large-surface stainless steel pans.

σB is not required for L. monocytogenes growth at 4°C.

While our results indicate that an L. monocytogenes strain with a nonpolar ΔsigB deletion did not show reduced growth at 4°C in BHI compared to that of its isogenic parent strain, despite lower OD600 values for the ΔsigB strain, others (7) have reported the reduced growth at 4°C of L. monocytogenes 10403S with an insertional mutation in sigB in defined medium, which is less nutrient rich than BHI. These discrepancies may result from σB-independent effects of the insertional mutagenesis approach used by Becker et al. (7), e.g., growth retardation at 4°C due to the presence and expression of an antibiotic resistance gene in the insert. Alternatively, a sigB deletion may affect L. monocytogenes growth only at low temperatures in minimal media, e.g., as growth in these media may also represent a stress condition unrelated to temperature. Further characterization of L. monocytogenes strains with in-frame sigB deletions for the ability to grow in different media and in selected foods at 4 and 30 or 37°C will be necessary to further dissect possible contributions of σB to cold growth under different environmental conditions.

Transcription of the cold stress genes ltrC and fri is at least partially σB dependent.

The transcription of opuCA and the opuCABCD operon, which encodes a carnitine transporter that appears to be involved in enhancing L. monocytogenes survival under conditions of osmotic and cold stress (2), has been found to be at least partially σB dependent in a number of studies (12, 16, 17, 25, 34). Our study confirmed that other genes with putative or confirmed roles in cold stress survival/cold growth (i.e., ltrC and fri) are also at least partially σB dependent. ltrC, which encodes a protein termed low-temperature requirement C protein, with an as-yet-unknown function, has previously been shown to be required for the growth of L. monocytogenes at 4°C in BHI (43, 44) with antibiotics, which were needed to maintain the transposon insertion in ltrC in the strain used. Our results are consistent with a previous microarray study which showed that ltrC transcript levels are σB dependent in L. monocytogenes exposed to osmotic-stress conditions (25) and which found that ltrC is preceded by a putative σB-dependent promoter. We experimentally identified a σB-dependent ltrC promoter and thus showed that ltrC transcription can directly be activated by σB. Our data on the transcription of fri, which encodes an 18-kDa CSP hypothesized to be required for iron storage in L. monocytogenes (31), are consistent with a study by Olsen et al. (31) which mapped the σB- and σA-dependent promoter regions of fri and found that fri was partially σB dependent at 37°C. Importantly, our data show that fri is transcribed using both σB-dependent and -independent mechanisms in L. monocytogenes exposed to 4°C. Our data also show that the transcription of oppA, which encodes an oligopeptide permease that is required during growth at low temperatures (10), is clearly σB independent. Overall, we conclude that, among selected genes that have previously been reported to contribute to cold growth or to be induced by low temperatures, some genes are partially σB dependent while others are clearly σB independent. Even those genes with contributions to cold growth that are preceded by a σB-dependent promoter and clearly show σB-dependent transcription under certain conditions may be predominantly expressed through σB-independent mechanisms at 4°C, as was strikingly demonstrated by the σB-independent transcription of opuCA during growth at 4°C.

While σB activity is induced during 30 min of cold shock at 4°C, this cold shock does not lead to the induction of σB-dependent or -independent cold shock genes.

Measurements of transcript levels of selected genes in the L. monocytogenes 10403S and ΔsigB strains during 4°C cold shock for 30 min revealed that σB activity is induced within 15 min of exposure of L. monocytogenes to 4°C, as supported by increased transcription of the σB-dependent bsh gene in 10403S. While bsh does not have a recognized role during growth at low temperatures, it appears to be a suitable indicator gene for σB activity under these conditions. opuCA has been used as an indicator gene for σB activity in a number of previous studies (35); however, our results show σB-independent opuCA transcription, particularly at 4°C. The rapid induction of σB activity reported here is consistent with previous studies that have shown the induction of σB activity within <5 min of L. monocytogenes exposure to other stress conditions (e.g., osmotic stress) (35).

Interestingly, in our study, neither the σB-independent gene oppA nor the at least partially σB-dependent cold shock genes fri, opuCA, and ltrC showed induction of transcription during cold shock exposure for 30 min. In contrast, Graumann et al. (18) showed that the production of 23 proteins was induced within 30 min of cold shock (i.e., exposure to 15°C) in B. subtilis. While Angelidis et al. (2) reported increased carnitine uptake through activation of a transporter encoded by opuC in L. monocytogenes exposed to cold shock for 30 min in defined media with carnitine, their protocol used a centrifugation step. In addition, increased carnitine uptake could be mediated by protein activation or increased translation of the preformed opuC transcript rather than induction of transcription. While our findings may indicate that rapid induction of cold shock genes is limited in the transition of log-phase L. monocytogenes cells from higher temperatures (e.g., 37°C) to low temperatures in BHI, future full-genome transcriptional profiling during cold shock is needed to determine whether there are any specific L. monocytogenes genes that are rapidly induced during cold shock. The identification of σB-independent promoters upstream of fri and opuCA provides a possible explanation for the observation that transcription of these genes is not induced during a 30-min cold shock, even though σB activity seems to be induced; enhanced σB-dependent transcription of these genes may be too limited to be detected above baseline levels of σB-independent transcription. Alternatively or in addition, only part of the σB regulon may be induced during cold shock and the induction of σB-dependent transcription under cold shock conditions may require transcriptional activators in addition to σB. This hypothesis is consistent with microarray-based data that indicated that different members of the σB regulon are induced under different σB-activating stress conditions (i.e., osmotic or stationary-phase stress) (25).

Expression of the putative cold stress genes opuCA, fri, and oppA is σB independent during growth at 4°C, while the cold shock gene ltrC as well as bsh shows growth phase and σB-dependent transcription during growth at 4°C.

Consistently with the fact that σB is a stationary-phase σ factor and that σB activity is induced in L. monocytogenes cells grown to stationary phase at 30 and 37°C (25, 34), we found that the transcription of bsh and ltrC, both of which are preceded by σB-dependent promoters, is higher in stationary-phase cells grown at 4°C than in log-phase cells grown at this temperature. On the other hand, transcript levels of oppA, opuCA, and fri in cells grown at 4°C in BHI were not affected by growth phase. Further, transcript levels for opuCA and fri, both of which are preceded by a σB-dependent promoter, were not lower in the ΔsigB null mutant. This observation was particularly striking for opuCA, which clearly shows σB-dependent transcription at 30 and 37°C (25, 34) and encodes a carnitine transporter that appears to contribute to cold growth in L. monocytogenes (2). Based on our promoter-mapping experiments, it appears that opuCA transcription originates predominantly from a σA-dependent promoter during growth at 4°C. Overall, it appears that the transcription of selected genes that encode proteins with roles in cold growth and that are partially σB dependent (e.g., opuCA, fri, and ltrC) is driven predominantly from σB-independent promoters in L. monocytogenes grown at 4°C. It is possible that activation of σB would contribute to enhanced transcription of these genes at 4°C if L. monocytogenes was exposed to other stress conditions reported to activate σB in L. monocytogenes grown at 30 or 37°C, e.g., nutrient limitation, acid stress, and osmotic stress (13, 15, 25, 35, 41). While contributions of σB to L. monocytogenes growth at 4°C may appear minor in cells grown in rich media, σB may contribute to the ability of L. monocytogenes to grow under refrigeration temperatures in at least some types of foods. Future experiments investigating the ability of an L. monocytogenes strain with a nonpolar sigB mutation to grow on different foods stored at refrigeration temperatures and investigating σB-dependent transcription in L. monocytogenes on foods stored at 4°C are needed to further clarify the contributions of σB to cold growth.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Nightingale and D. Barbano for assistance with statistical analyses. We also thank S. Chaturongakul and S. Raengpradub for critical review of the manuscript.

Y. C. Chan was supported by USDA National Needs Fellowship grant 2002-38420-11738 (to K.J.B.). This work was also supported by National Institutes of Health award no. RO1-AI052151-01A1 (to K.J.B.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 August 2007.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angelidis, A. S., and G. M. Smith. 2003. Role of the glycine betaine and carnitine transporters in adaptation of Listeria monocytogenes to chill stress in defined medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:7492-7498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angelidis, A. S., L. T. Smith, L. M. Hoffman, and G. M. Smith. 2002. Identification of OpuC as a chill-activated and osmotically activated carnitine transporter in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:2644-2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annous, B. A., L. A. Becker, D. O. Bayles, D. P. Labeda, and B. J. Wilkinson. 1997. Critical role of anteiso-C15:0 fatty acid in the growth of Listeria monocytogenes at low temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3887-3894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayles, D. O., B. A. Annous, and B. J. Wilkinson. 1996. Cold stress proteins induced in Listeria monocytogenes in response to temperature downshock and growth at low temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1116-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayles, D. O., and B. J. Wilkinson. 2000. Osmoprotectants and cryoprotectants for Listeria monocytogenes. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 30:23-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becker, L. A., M. S. Çetin, R. W. Hutkins, and A. K. Benson. 1998. Identification of the gene encoding the alternative sigma factor σB from Listeria monocytogenes and its role in osmotolerance. J. Bacteriol. 180:4547-4554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker, L. A., S. N. Evans, R. W. Hutkins, and A. K. Benson. 2000. Role of σB in adaptation of Listeria monocytogenes to growth at low temperature. J. Bacteriol. 182:7083-7087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beumer, R. R., M. C. Te Giffel, L. J. Cox, F. M. Rombouts, and T. Abee. 1994. Effect of exogenous proline, betaine, and carnitine on growth of Listeria monocytogenes in a minimal medium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1359-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bishop, D. K., and D. J. Hinrichs. 1987. Adoptive transfer of immunity to Listeria monocytogenes. The influence of in vitro stimulation on lymphocyte subset requirements. J. Immunol. 139:2005-2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borezee, E., E. Pellegrini, and P. Berche. 2000. OppA of Listeria monocytogenes, an oligopeptide-binding protein required for bacterial growth at low temperature and involved in intracellular survival. Infect. Immun. 68:7069-7077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brigulla, M., T. Hoffmann, A. Krisp, A. Völker, E. Bremer, and U. Völker. 2003. Chill induction of the SigB-dependent general stress response in Bacillus subtilis and its contribution to low-temperature adaptation. J. Bacteriol. 185:4305-4314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cetin, M. S., C. Zhang, R. W. Hutkins, and A. K. Benson. 2004. Regulation of transcription of compatible solute transporters by the general stress sigma factor, σB, in Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 186:794-802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaturongakul, S., and K. J. Boor. 2006. σB activation under environmental and energy stress conditions in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5197-5203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Datta, P. P., and R. K. Bhadra. 2003. Cold shock response and major cold shock proteins of Vibrio cholerae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6361-6369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferreira, A., C. P. O'Byrne, and K. J. Boor. 2001. Role of σB in heat, ethanol, acid, and oxidative stress resistance and during carbon starvation in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4454-4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraser, K. R., D. Harvie, P. J. Coote, and C. P. O'Byrne. 2000. Identification and characterization of an ATP binding cassette l-carnitine transporter in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4696-4704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser, K. R., D. Sue, M. Wiedmann, K. Boor, and C. P. O'Byrne. 2003. Role of σB in regulating the compatible solute uptake systems of Listeria monocytogenes: osmotic induction of opuC is σB dependent. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2015-2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graumann, P., K. Schröder, R. Schmid, and M. A. Marahiel. 1996. Cold shock stress-induced proteins in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:4611-4619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glantz, S. A., and B. K. Slinker. 2001. Primer of applied regression & analysis of variance, 2nd ed., p. 185-240. McGraw-Hill, Inc., New York, NY.

- 20.Gray, M. L., and A. H. Killinger. 1966. Listeria monocytogenes and listeric infections. Bacteriol. Rev. 30:309-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hébraud, M., and J. Guzzo. 2000. The main cold shock protein of Listeria monocytogenes belongs to the family of ferritin-like proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 190:29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunger, K., C. L. Beckering, F. Wiegeshoff, P. L. Graumann, and M. A. Marahiel. 2006. Cold-induced putative DEAD box RNA helicases CshA and CshB are essential for cold adaptation and interact with cold shock protein B in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 188:240-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang, W., Y. Hou, and M. Inouye. 1997. CspA, the major cold-shock protein of Escherichia coli, is an RNA chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 272:196-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junttila, J. R., S. I. Niemela, and J. Hirn. 1988. Minimum growth temperatures of Listeria monocytogenes and non-haemolytic Listeria. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 65:321-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kazmierczak, M. J., S. C. Mithoe, K. J. Boor, and M. Wiedmann. 2003. Listeria monocytogenes σB regulates stress response and virulence functions. J. Bacteriol. 185:5722-5734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kazmierczak, M. J., M. Wiedmann, and K. J. Boor. 2006. Contributions of Listeria monocytogenes σB and PrfA to expression of virulence and stress response genes during extra- and intracellular growth. Microbiology 152:1827-1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ko, R., and L. T. Smith. 1999. Identification of an ATP-driven, osmoregulated glycine betaine transport system in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4040-4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ko, R., L. T. Smith, and G. M. Smith. 1994. Glycine betaine confers enhanced osmotolerance and cryotolerance on Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 176:426-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu, S., J. E. Graham, L. Bigelow, P. D. Morse II, and B. J. Wilkinson. 2002. Identification of Listeria monocytogenes genes expressed in response to growth at low temperature. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1697-1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell, M. E. 1978. Carnitine metabolism in human subjects. I. Normal metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 31:293-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olsen, K. N., M. H. Larsen, C. G. Gahan, B. Kallipolitis, X. A. Wolf, R. Rea, C. Hill, and H. Ingmer. 2005. The Dps-like protein Fri of Listeria monocytogenes promotes stress tolerance and intracellular multiplication in macrophage-like cells. Microbiology 151:925-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phan-Thanh, L., and T. Gormon. 1995. Analysis of heat and cold shock proteins in Listeria by two-dimensional electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 16:444-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwab, U., B. Bowen, C. Nadon, M. Wiedmann, and K. J. Boor. 2005. The Listeria monocytogenes prfAP2 promoter is regulated by sigma B in a growth phase dependent manner. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 245:329-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sue, D., K. J. Boor, and M. Wiedmann. 2003. σB-dependent expression patterns of compatible solute transporter genes opuCA and lmo1421 and the conjugated bile salt hydrolase gene bsh in Listeria monocytogenes. Microbiology 149:3247-3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sue, D., D. Fink, M. Wiedmann, and K. J. Boor. 2004. σB-dependent gene induction and expression in Listeria monocytogenes during osmotic and acid stress conditions simulating the intestinal environment. Microbiology 150:3843-3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tasara, T., and R. Stephan. 2007. Evaluation of housekeeping genes in Listeria monocytogenes as potential internal control references for normalizing mRNA expression levels in stress adaptation models using real-time PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 269:265-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2003. Quantitative assessment of the relative risk to public health from foodborne Listeria monocytogenes among selected categories of ready-to-eat foods. http://www.foodsafety.gov/∼dms/lmr2-toc.html. Accessed 28 March 2007.

- 38.Verheul, A., F. M. Rombouts, and T. Abee. 1998. Utilization of oligopeptides by Listeria monocytogenes Scott A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1059-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker, S. J., and M. F. Stringer. 1987. Growth of Listeria monocytogenes and Aeromonas hydrophila at chill temperatures. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 63:R20. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wemekamp-Kamphuis, H. H., R. D. Sleator, J. A. Wouters, C. Hill, and T. Abee. 2004. Molecular and physiological analysis of the role of osmolyte transporters BetL, Gbu, and OpuC in growth of Listeria monocytogenes at low temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2912-2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiedmann, M., T. J. Arvik, R. J. Hurley, and K. J. Boor. 1998. General stress transcription factor σB and its role in acid tolerance and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 180:3650-3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeisel, S. H., M. H. Mar, J. C. Howe, and J. M. Holden. 2003. Concentrations of choline-containing compounds and betaine in common foods. J. Nutr. 133:1302-1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng, W., and S. Kathariou. 1995. Differentiation of epidemic-associated strains of Listeria monocytogenes by restriction fragment length polymorphism in a gene region essential for growth at low temperatures (4°C). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:4310-4314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zheng, W., and S. Kathariou. 1994. Transposon-induced mutants of Listeria monocytogenes incapable of growth at low temperature (4°C). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 121:287-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.