Abstract

Evaluation of the fate and transport of biological warfare (BW) agents in landfills requires the development of specific and sensitive detection assays. The objective of the current study was to develop and validate SYBR green quantitative real-time PCR (Q-PCR) assays for the specific detection and quantification of surrogate BW agents in synthetic building debris (SBD) and leachate. Bacillus atrophaeus (vegetative cells and spores) and Serratia marcescens were used as surrogates for Bacillus anthracis (anthrax) and Yersinia pestis (plague), respectively. The targets for SYBR green Q-PCR assays were the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic transcribed spacer (ITS) region and recA gene for B. atrophaeus and the gyrB, wzm, and recA genes for S. marcescens. All assays showed high specificity when tested against 5 ng of closely related Bacillus and Serratia nontarget DNA from 21 organisms. Several spore lysis methods that include a combination of one or more of freeze-thaw cycles, chemical lysis, hot detergent treatment, bead beat homogenization, and sonication were evaluated. All methods tested showed similar threshold cycle values. The limit of detection of the developed Q-PCR assays was determined using DNA extracted from a pure bacterial culture and DNA extracted from sterile water, leachate, and SBD samples spiked with increasing quantities of surrogates. The limit of detection for B. atrophaeus genomic DNA using the ITS and B. atrophaeus recA Q-PCR assays was 7.5 fg per PCR. The limits of detection of S. marcescens genomic DNA using the gyrB, wzm, and S. marcescens recA Q-PCR assays were 7.5 fg, 75 fg, and 7.5 fg per PCR, respectively. Quantification of B. atrophaeus vegetative cells and spores was linear (R2 > 0.98) over a 7-log-unit dynamic range down to 101 B. atrophaeus cells or spores. Quantification of S. marcescens (R2 > 0.98) was linear over a 6-log-unit dynamic range down to 102 S. marcescens cells. The developed Q-PCR assays are highly specific and sensitive and can be used for monitoring the fate and transport of the BW surrogates B. atrophaeus and S. marcescens in building debris and leachate.

The first recorded attempt to use pathogens as biological warfare (BW) agents was in the 14th century when the Mongols catapulted plague-infected victims into the city of Kaffa (Feodosiya, Ukraine) to spread the disease (33, 53). During and after World War II, the development and use of pathogens, such as Yersinia pestis (plague), Bacillus anthracis (anthrax), and Francisella tularensis (tularemia), as BW agents intensified (41, 53). Recently, there has been concern about the potential “weaponization” of pathogens for bioterrorism use, with the October 2001 bioterrorist attack with B. anthracis in the United States as the most prominent example (17, 41).

The 2001 event has sparked renewed interest in the development of detection platforms for BW agents (8, 17, 24, 33, 48, 57), methods for inactivation (16, 39, 61) and decontamination of Bacillus spores (4, 44), sampling protocols for recovery of Bacillus spores from surfaces (5, 20), and methods for viability assessment (31, 47). The decontamination of a building following a terrorist attack with BW agents will generate a significant amount of building decontamination residue that is likely to remain contaminated with BW agents. One disposal alternative is burial in a landfill. Despite the significance of the aforementioned studies in improving bioterrorism preparedness, information on the fate and transport of microorganisms in general and specifically of BW agents in landfills is lacking. This knowledge will assist in bioterrorism preparedness and in the assessment of alternatives for the safe disposal of building decontamination residue.

Evaluation of the fate and transport of BW agents in landfills requires the development of specific and sensitive detection assays. However, surrogates are required, as it is sometimes not feasible to use actual BW agents (40). Several surrogate organisms of BW agents have been used in previous research (40). Specifically, Bacillus atrophaeus has been used as a surrogate for B. anthracis in studies to develop methods to detect B. atrophaeus spores (8, 52, 55), to determine the effects of electric charge and field on the viability of airborne bacteria (34), to develop methods for viability assessment of Bacillus spores (31), to evaluate the effect of electric beam irradiation for inactivation of Bacillus spores in envelopes (16), and to investigate the effectiveness of decontamination methods against B. atrophaeus spores present on furniture (4, 44). Serratia marcescens has been used as a surrogate for Yersinia pestis for examining the fate of pathogens in indoor air (56).

Traditional monitoring of biocontaminants relies on culture-based techniques that are time-consuming and can detect only culturable cells (5). However, recent developments in nucleic acid-based detection systems, in particular quantitative real-time PCR (Q-PCR), offer significant advantages over culture-based methods for the detection and quantification of BW agents. Q-PCR provides high specificity, sensitivity, and speed (38, 49). In addition, it allows the detection of cells irrespective of their culturability. Several Q-PCR assays have been developed and validated for the detection and quantification of BW agents (e.g., Y. pestis, B. anthracis, F. tularensis, and smallpox virus) (17, 18, 21, 23, 24, 33, 43, 48, 57). However, to date, only one Q-PCR assay for the BW surrogate B. atrophaeus and one Q-PCR assay for the BW surrogate S. marcescens have been reported (4, 5, 25). While Buttner et al. (4, 5) reported the detection of B. atrophaeus using Q-PCR targeting the B. atrophaeus recA gene, the specificity of the assay was not reported. In addition, the sequence of the target gene could not be identified in published sequences in the GenBank, DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ), and European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) databases. Iwaya et al. (25) used the 16S rRNA gene for designing a Q-PCR assay for detecting S. marcescens in blood. Although the 16S rRNA gene has commonly been used for modern species classification, it has limitations in discriminating species of closely related taxa because of high 16S rRNA sequence similarities (13). Instead, protein-coding genes and the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic transcribed spacer (ITS) region, which both exhibit higher sequence variation than the more conserved 16S rRNA gene, have been used for identifying species of closely related taxa (6, 9, 10, 27, 42, 43, 50). Therefore, to facilitate the use of B. atrophaeus and S. marcescens as surrogates for pathogens that could potentially be used as BW agents, nucleic acid target sequences that provide the most discrimination between the surrogate organism and its nearest evolutionary neighbor are needed for the design of specific Q-PCR assays for detection and quantification of B. atrophaeus and S. marcescens.

The objective of this study was to develop and validate a set of SYBR green Q-PCR assays for the specific detection and quantification of BW surrogates S. marcescens and B. atrophaeus. The targets for SYBR green Q-PCR assays were the 16S-23S rRNA ITS region and recA gene for B. atrophaeus and the 16S rRNA and gyrB, wzm, and recA genes for S. marcescens. The Q-PCR assays were validated using DNA extracted from a pure bacterial culture and DNA extracted from sterile water, synthetic building debris (SBD), and leachate spiked with surrogates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains were grown on Difco nutrient agar (Becton, Dickinson, and Co., Sparks, MD) at 30°C for 24 h with the exception of S. marcescens ATCC 13880, Serratia plymuthica DSM 4540, and Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC 13525 that were grown at 26°C. In addition to obtaining B. atrophaeus ATCC 9372 vegetative cells (formerly Bacillus subtilis var. niger) from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), purified spore suspensions of B. atrophaeus ATCC 9372 were obtained from the North American Science Associates, Inc., (NAMSA) Ohio laboratory (Northwood, OH).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used for assessment of primer specificity and the CT values obtained in Q-PCR

| Species (strain)a |

CT value obtained in Q-PCR withb:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | recABa | gyrB | recASm | wzm | 16S rRNA genes | |

| Bacillus atrophaeus (ATCC 9372) | 16 ± 0.17 | 18 ± 0.23 | − | − | 37 ± 0.12 | − |

| Bacillus brevis (CBSC 15-4865) | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Bacillus cereus (CBSC 15-4870) | 36 ± 0.25 | − | − | − | − | 33 ± 0.12 |

| Bacillus mycoides (CBSC 15-4871) | − | − | − | − | − | 34 ± 0.23 |

| Bacillus megaterium (CBSC 15-4900) | − | 34 ± 0.20 | − | − | − | − |

| Bacillus sphaericus (CBSC 15-4908) | − | − | − | − | 36 ± 0.17 | 36 ± 0.45 |

| Bacillus subtilis (CBSC 15-4921) | − | − | − | − | 37 ± 0.28 | 36 ± 0.61 |

| Bacillus thuringiensis (CBSC 15-4926) | − | − | − | − | − | 35 ± 0.12 |

| Bacillus badius (DSM 23) | − | − | − | − | 36 ± 0.53 | 35 ± 0.32 |

| Bacillus flexus (DSM 1320) | − | − | − | − | − | 34 ± 0.42 |

| Bacillus amyloliquifaciens (DSM 7) | − | − | − | − | − | 35 ± 0.29 |

| Bacillus mojavensis (DSM 9205) | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Bacillus fusiformis (DSM 2898) | − | − | − | − | 37 ± 0.30 | − |

| Paenibacillus validus (DSM 3037) | − | 38 ± 0.40 | − | − | − | − |

| Paenibacillus chondroitinus (DSM 5051) | − | − | − | − | − | 34 ± 0.10 |

| Serratia marcescens (ATCC 13880) | − | − | 17 ± 0.15 | 18 ± 0.43 | 16 ± 0.22 | 14 ± 0.11 |

| Serratia ficaria (DSM 4569) | 36 ± 0.33 | − | − | 38 ± 0.33 | − | 38 ± 0.22 |

| Serratia fonticola (DSM 4576) | − | − | − | − | 37 ± 0.13 | 35 ± 0.58 |

| Serratia odorifora (DSM 4582) | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Serratia plymuthica (DSM 4540) | − | − | − | − | 36 ± 0.45 | 35 ± 0.34 |

| Serratia quinivorans (DSM 4597) | − | − | − | − | − | 36 ± 0.22 |

| Serratia entomophila (DSM 12358) | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens (ATCC 13525) | − | − | − | − | 36 ± 0.19 | 33 ± 0.39 |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA; CBSC, Carolina Biological Supply Company, Burlington, NC; DSM, German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures.

CT values are mean values ± standard deviations of duplicates. −, no detection above threshold before cycle 40.

Primer design for SYBR green Q-PCR.

The primers utilized in this study are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for SYBR green Q-PCR assays

| Target gene | Primera | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Tm (°C)b | % GC | Amplicon length (bp) | Accession no. (position on gene)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. atrophaeus spacer | ITS_F | CATTCGATTCTTCGAGATG | 48 | 42 | 75 | AF478080 (259-333) |

| region | ITS_R | GGTCTTACTTTTGAATGTGATGTC | 52 | 38 | ||

| B. atrophaeus recA | recABa_F | ACCAGACAATGCTCGACGT | 57 | 53 | 131 | NA |

| gene | recABa_R | CCCTCTTGAAATTCCCGAAT | 53 | 45 | ||

| S. marcescens gyrB | gyrB_F | AGTGCACGAACAAACTTACAG | 53 | 43 | 138 | AJ300536 (113-251) |

| gene | gyrB_R | GTCGTACTCGAAATCGGTCACA | 57 | 50 | ||

| S. marcescens recA | recASm_F | CAAGGCGAATGCCTGTAACT | 56 | 50 | 202 | M22935 (1526-1727) |

| gene | recASm_R | GAGGATAGGCGCCACATAAA | 55 | 50 | ||

| S. marcescens | wzm_F | GGTCATGCGGGTTCAAATAC | 54 | 50 | 153 | L34166 (547-699) |

| integral membrane | wzm_R | ATGACCGAGCGTGGAAATAC | 55 | 50 | ||

| protein gene | ||||||

| S. marcescens 16S | 16S_F | GGTGAGCTTAATACGTTCATCAATTG | 55 | 39 | 179 | AJ233431 (435-613) |

| rRNA gene | 16S_R | GCAGTTCCCAGGTTGAGCC | 59 | 63 |

The primer is named after the target gene, and F and R at the end of the primer name indicate forward and reverse orientations, respectively.

Theoretical melting temperature (Tm) calculated using the OligoAnalyzer 3.0 from Integrated DNA Technologies (http://www.idtdna.com/analyzer/Applications/OligoAnalyzer/Default.aspx; Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA).

Positions of genes are given according to the accession numbers. NA, not applicable.

B. atrophaeus-specific Q-PCR primers.

The sequences of the primers (ITS_F and ITS_R) targeting the 16S-23S rRNA ITS region specific for B. atrophaeus were designed on the basis of the 16S-23S rRNA ITS region of B. atrophaeus ATCC 49337 (GenBank accession number AF478080 [60]). The 16S-23S rRNA ITS sequences of 23 Bacillus spp., 9 Paenibacillus spp., 6 Brevibacillus spp., 2 Geobacillus spp., 1 Marinibacillus species, and 1 Virgibacillus species were retrieved from the GenBank, EMBL, and DDBJ databases (accession numbers AF478062 to AF478111 [60], AB05068, AJ544538, AY157575, and AY149473). The retrieved sequences were aligned via the multiple alignment tool ClustalW (54) using BioEdit v7.0.5 (14). Sequence regions suitable for the design of B. atrophaeus ITS-specific Q-PCR primers (ITS_F and ITS_R) were selected by visual inspection of ClustalW multiple alignments. For the amplification of B. atrophaeus recA gene, previously designed Q-PCR primers were used, although the specificity of this previously developed Q-PCR assay was not reported (4, 5). The specificity of the recA Q-PCR assay was tested in this study. To differentiate the B. atrophaeus recA Q-PCR assay from the S. marcescens recA Q-PCR assay, B. atrophaeus recA is hereafter referred to as recABa and S. marcescens recA is hereafter referred to as recASm.

S. marcescens-specific Q-PCR primers.

The sequences of the primers (gyrB_F and gyrB_R) targeting the gyrB gene specific for S. marcescens were designed on the basis of the gyrB sequence of S. marcescens ATCC 13880 (EMBL accession number AJ300536) (9). The gyrB sequences of 10 Serratia spp., 1 Citrobacter species, 2 Enterobacter spp., 1 Hafnia species, 2 Klebsiella spp., 1 Morganella species, 1 Pectobacterium species, 2 Proteus spp., 1 Providencia species, and 1 Salmonella species were retrieved from the EMBL database (accession numbers AJ300528 to AJ300554 [9]). The retrieved sequences were aligned as described above.

The sequences of the primers (recASm_F and recASm_R) targeting the recA gene specific for S. marcescens were designed on the basis of the recA sequence of S. marcescens (GenBank accession number M22935) (2). The recA sequences of 2 Serratia spp., 11 Erwinia spp., 4 Yersinia spp., 2 Pantoea spp., 1 Hafnia species, 1 Rahnella species, 7 Pectobacterium spp., 5 Brenneria spp., 1 Samsonia species, 1 Salmonella species, 3 Enterobacter spp., 1 Klebsiella species, 2 Shigella spp., 2 Escherichia spp., 1 Citrobacter species, 2 Bacillus spp., 2 Pseudomonas spp., 1 Photobacterium species, and 2 Vibrio spp. were retrieved from the GenBank, EMBL, and DDBJ databases (accession numbers M22935 [2], DQ859854 to DQ859890, DQ196414, AF301039, AY332960, AY332972, AY219007, AY727899, AY208918, AJ580873, AY686537, DQ995254, AJ511368, AJ515542, AY707924, AF301120, AY217064, AY332993, DQ458613, AJ223882, and AJ316152). The retrieved sequences were aligned as described above.

The sequences of the primers (wzm_F and wzm_R) targeting the wzm gene specific for S. marcescens were designed on the basis of the wzm sequence of S. marcescens (GenBank accession number L34166) (45). All available wzm gene sequences were retrieved from the GenBank, EMBL, and DDBJ databases (accession numbers L34166 [45], DQ907230, AY528413, BK000051, AJ605741, AY659979, Z18920, AJ007311, AJ007747, AY558875, AY337617, AY319940, AF337647, AY442352, AY653208, AF503594, AF328862, AY376146, AY253301, AF097519, AF285636, AE012010, AE012158, AF18284, AY028370, AF047478, AF189151, AF064070, L41518, L31775, D14156, AB010296, AB010293, and U63722). The retrieved sequences were aligned as described above.

The Q-PCR primers (16S_F and 16S_R) used for the 16S rRNA gene of S. marcescens have been described (25). The specificity of the primers (16S_F and 16S_R) has been tested previously (25) and in the present study.

All primers were tested for in silico specificity using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST v.2.2.15) (1). The specificity of the primers was also tested against 5 ng of genomic DNA isolated from pure cultures of target organisms (in this study, surrogate organisms) and nontarget organisms (closely related organisms) (Table 1). All primers used in this study were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA).

DNA extraction from microbial cells and spores.

Five methods of DNA extraction were evaluated for spore lysis and DNA release. Spores of B. atrophaeus ATCC 9372 were placed in sterile phosphate-buffered saline to 104 spores/ml, and then 100 μl of the suspension (equivalent to 103 spores) was subjected to different DNA extraction treatments as described below.

(i) Treatment 1 (freeze-thaw cycles followed by chemical lysis and bead beat homogenization).

Samples were frozen at −80°C for 5 min and then immediately placed in a water bath at 65°C for 1 min to rapidly thaw. This process was repeated four times. Samples were then added into a 2-ml mini-bead beater tube containing a mixture of PowerSoil beads and 300 mg of 106-μm glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Then, 60 μl of solution C1 (a lysis buffer containing sodium dodecyl sulfate) provided in the PowerSoil kit was added to the mixture, and the tube was placed in a mini-bead beater (Biospec Inc., Bartlesville, OK) and homogenized for 3 min at maximum speed. After homogenization, the genomic DNA was extracted using the PowerSoil DNA extraction kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Solana Beach, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

(ii) Treatment 2 (hot detergent treatment followed by bead beat homogenization).

Samples were added to a 2-ml mini-bead beater tube containing a mixture of PowerSoil beads and 300 mg of 106-μm glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Then, 60 μl of solution C1 was added to the mixture, and the mixture was incubated at 70°C for 20 min. After incubation, the tube was homogenized for 3 min at maximum speed. Genomic DNA was extracted using the PowerSoil DNA extraction kit protocol.

(iii) Treatment 3 (bead beat homogenization and chemical lysis).

The genomic DNA was extracted following the PowerSoil DNA extraction kit protocol with one modification: 300 mg of 106-μm glass beads were added.

(iv) Treatment 4 (sonication at different times followed by chemical lysis.

Samples were sonicated in 2-ml centrifuge tubes containing 100 mg of 106-μm glass beads using a Fisher Scientific model 550 Sonic Dismembrator (Pittsburgh, PA) at 20 kHz for 1, 2, or 3 min. After sonication, mixtures were transferred into 2-ml mini-bead beater tubes, and 60 μl of solution C1 was added to each mixture. The mixtures were vortexed for 5 seconds. After the mixtures were vortexed, the genomic DNA was extracted by following the PowerSoil DNA extraction kit protocol but without the bead beating step.

(v) Treatment 5 (sonication followed by chemical lysis and bead beat homogenization).

Treatment 5 is the same as treatment 4, but after the mixtures were vortexed, the tubes were subjected to bead beat homogenization for 3 min at maximum speed.

The quality (A260/A280) and quantity (A260) of extracted genomic DNA was determined with a Nanodrop (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE) spectrophotometer. The extracted genomic DNA from each treatment was amplified in duplicate using Q-PCR, and the threshold cycles (CT) were recorded (see below).

Q-PCR conditions.

Real-time PCR was performed in a 25-μl reaction mixture volume containing 12.5 μl of 2× iQ SYBR green supermix (100 mM KCl, 40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.4, 0.4 mM [each] deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 50 U/ml iTaq DNA polymerase, 6 mM MgCl2, SYBR green I, 20 nM fluorescein, stabilizers) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), 0.5 μM of each primer, sample template (1 μl for the specificity experiment, 5 μl for the spore lysis experiment, 2 μl for standard curves using DNA extracted from a pure bacterial culture, and 5 μl for the spiking experiment), and RNase-free sterile water to a final volume of 25 μl. Amplification was performed using the iQ5 real-time detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) using the following program: (i) an initial denaturing step at 95°C for 5 min; (ii) 45 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 50 s, annealing at 63°C for 50 s, and extension at 72°C for 45 s; and (iii) a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. All assays were identical in primer concentration and annealing temperature. Q-PCR assays with CT values over 40 were considered negative. For each PCR run, a negative (no-template) control was used to test for false-positive results or contamination. The presence of nonspecific products or primer dimers was confirmed by observation of a single melting peak in a melting curve analysis using the iCycler iQ5 optical system software v1.0. In addition, the PCR products were subjected to gel electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide to confirm the absence of nonspecific products or primer dimers.

Q-PCR standard curves.

SBD contained the following components (dry weight shown as a percentage in parentheses) (based on information in reference 32): ceiling tile (12.79), carpet (4.47), vinyl (0.78), electronics (5.56), furniture (33.68), white office paper (34.29), folders/cardboard (4.22), and mixed office paper (4.21). The SBD materials were shredded and mixed in the proportions given above. After the material was shredded, it was ground in a Wiley mill to pass a 1-mm screen for use in the spiking experiment. Leachate for the spiking experiment was obtained from a 208-liter drum containing well-decomposed residential waste incubated at 37°C.

To determine the limits of detection, linear ranges, and amplification efficiencies of the Q-PCR assays, two types of standard curves were constructed: (i) standard curves based on DNA extracted from a pure bacterial culture; and (ii) standard curves constructed using DNA extracted from spiked sterile water, SBD, and leachate samples.

Standard curves with DNA extracted from a pure bacterial culture were constructed using serial dilutions of genomic DNA (75 ng, 7.5 ng, 0.75 ng, 75 pg, 7.5 pg, 0.75 pg, 75 fg, 7.5 fg, and 0.75 fg per amplification reaction mixture) from B. atrophaeus ATCC 9372 and S. marcescens ATCC 13880. For each Q-PCR assay, the experiment was repeated twice on separate plates with triplicate Q-PCRs per experiment (n = 6) to determine intra-assay reproducibility (within a plate) and interassay reproducibility (between plates). No-template controls were included in all PCR runs.

To construct standard curves based on spiked environmental samples, overnight cultures of B. atrophaeus ATCC 9372 vegetative cells and S. marcescens ATCC 13880 cells grown in nutrient broth were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min. The resulting pellets were resuspended in sterile water, and total bacterial counts were determined using a Cellometer (Nexcelom Bioscience, Lawrence, MA) and phase-contrast microscope at a magnification of ×40. In addition, four replicate B. atrophaeus ATCC 9372 spore suspensions were counted using a Cellometer. The serial dilutions for spiking experiments were based on those counts. B. atrophaeus ATCC 9372 vegetative cells or spores (100 μl) and S. marcescens ATCC 13880 cell suspensions (100 μl) were simultaneously added in increasing amounts (ranging from 100 to 107 cells or spores) to leachate (0.3 ml), SBD (0.5 g), and sterile water (0.3 ml) samples. Immediately after spiking, genomic DNA from each sample was extracted using the hot detergent and bead beat homogenization method (treatment 2). The spiking experiment was repeated twice on the same day with triplicate Q-PCRs per spiking experiment/assay (n = 6). Duplicate spiking experiments/assays were run on the same plate. No-template controls and nonspiked samples were included in all Q-PCR runs.

Data analysis.

Data collection and analysis were performed using iQ5 optical system software v1.0 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2003. The amplification efficiency, E, was calculated from the slope of the standard curve using the formula E = 10−1/slope − 1 (19). The coefficients of variation (CV) for the slope, y intercept, R2, and E values were used to determine intra-assay reproducibility (within a plate) and interassay reproducibility (between plates). The slopes and y intercepts among replicate standard curves obtained from two DNA extractions (corresponding to duplicate spiking experiments), each quantified in triplicate on the same plate (n = 6) were compared using paired sample t tests at P < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Specificity of the assays.

The annealing temperatures and primer concentrations of all six assays (Table 2) were optimized to determine the temperature and primer concentration that gave the best specificity without reduction in yield. The optimal annealing temperature and primer concentration for all Q-PCR assays were determined to be 63°C and 500 nM, respectively.

The BLAST results did not show any significant homology to other published sequences in the GenBank, DDBJ, and EMBL databases. The specificity of the primers in the present study was also verified empirically by running Q-PCR using 5 ng of genomic DNA isolated from 21 closely related organisms (Table 1). When testing the specificity of the newly developed Q-PCR assays (ITS, gyrB, recASm, and wzm), the majority of non-S. marcescens and non-B. atrophaeus species showed negative CT values (CT values over 40 were considered negative) with the exception of a few species that were detected but only at higher CT values (CT ≥ 36) compared to the CT values (16 ≤ CT ≤ 18) of the target organisms (Table 1). These findings indicate that the Q-PCR assays developed in this study are specific and that a minimum of 5 ng of DNA is required to generate a positive signal for some nontarget organisms. The recABa primers developed by Buttner et al. (4, 5) as tested here showed high specificity (Table 1). However, this is the first report of their specificity.

Although the 16S rRNA primers (16S_F and 16S_R) have been used successfully for the specific identification of S. marcescens in blood samples (25), they resulted in poor specificity in this study, as most of the tested organisms showed slight, but detectable, amplification at CT values of ≥33 (Table 1). The difference in specificity results between the two studies may be attributed to the fact that a different group of species was tested for specificity in the current study. In addition, SYBR green chemistry was used in this study and TaqMan probe chemistry was used in the previous study (25), which may have contributed to higher specificity. Despite the higher specificity of TaqMan probe chemistry compared to SYBR green chemistry, it is not always possible to design assays for TaqMan probe chemistry. These assays require the design of primers and probes that must satisfy rigid constraints that cannot always be easily applied, especially with the gene sequences selected in this study. For subsequent experiments, we decided to use only gyrB, recABa, and wzm Q-PCR assays for the detection and quantification of S. marcescens.

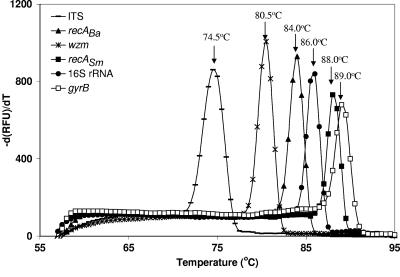

The absence of nonspecific products or primer dimers was confirmed by performing a melting curve analysis. The melting curve analysis showed a single clear melting peak for all Q-PCR assays and no formation of nonspecific products (Fig. 1). In addition, agarose gel electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide confirmed the absence of nonspecific products or primer dimers (data not shown). All no-template controls tested negative for the six Q-PCR assays used in this study.

FIG. 1.

Melting curve analysis with the corresponding melting temperatures of the six Q-PCR assays. RFU, relative fluorescence units.

The rationale behind the choice of the 16S-23S rRNA ITS region and protein-coding genes for the design of specific Q-PCR assays for the detection of B. atrophaeus and S. marcescens is that these target sequences exhibit higher genetic variation than the more conserved 16S rRNA gene and therefore can be utilized for differentiating species of closely related taxa (6, 9, 10, 27, 42, 43, 50). For example, because of its high nucleotide sequence variability, the gyrB gene has been shown to be a more reliable phylogenetic marker than the 16S rRNA gene for classifying Serratia species (9). Qi et al. (43) utilized the rpoB gene to differentiate B. anthracis from closely related bacilli. Similarly, Palmisano et al. (42) reported the use of rpoB gene to differentiate Bacillus licheniformis from the closely related species Bacillus sonorensis. Chun and Bae (6) demonstrated the usefulness of the gyrA gene for the rapid identification of B. subtilis and related taxa. Johnson et al. (27) and Shaver et al. (50) reported the use of 16S-23S rRNA ITS region to differentiate B. subtilis from the closely related species B. atrophaeus.

Extraction methods tested for maximum recovery of DNA from lysed spores.

Spore suspensions were tested for purity by phase-contrast microscopy at a magnification of ×100 to check for the presence of vegetative cells. In addition, to check for the presence of extracellular DNA that could be carried over from vegetative cells during spore preparation, 1 ml of spore suspension (108 spores) was subjected to centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 15 min to pellet the spores. The supernatant was then subjected to DNA extraction followed by Q-PCR. The results from both phase-contract microscopy and Q-PCR revealed the high purity of the spore suspensions obtained from the NAMSA Ohio laboratory (Northwood, OH). The CT values from an evaluation of several spore lysis methods were all between 31.5 and 33.5 (data not shown), suggesting that the methods tested were equally efficient in lysing the spores. In addition, spores were sonicated for different times (1, 2, or 3 min), with or without a bead beating step, using a sonicator probe in the presence of 106-μm glass beads and the calculated CT values were again similar (data not shown).

Several studies have reported that bead beat homogenization and sonication are effective in lysing spores (3, 15, 27, 28, 37, 59). Kuske et al. (30) reported that hot detergent and freeze-thaw (40 cycles) treatments were not effective in lysing B. atrophaeus and Fusarium moniliforme spores and that bead beat homogenization was the most effective method for extracting DNA from spores. It was shown using microscopic counts that Bacillus spores are resistant to freeze-thaw treatment (37). Similarly, Keswani et al. (28), Williams et al. (59), and Haugland et al. (15) have demonstrated that the bead beating method was most effective in recovering DNA from fungal spores. Belgrader et al. (3) improved the sonication time for spore lysis (30 seconds using a sonicator probe and 2 min using a sonicating water bath) by using 106-μm glass beads in the suspension. They reported that using a sonicator probe improved the limit of detection of spores by 3 log units.

Based on the comparisons of spore lysis methods presented here, the hot detergent treatment followed by bead beat homogenization (treatment 2) was selected to extract genomic DNA from bacterial cells and spores because it was shown to be equally effective in lysing spores, easy to conduct, and fast and has high sample processing capacity compared to treatments with sonication.

Limits of detection, linear ranges, and reproducibility of the Q-PCR assays using pure culture DNA.

Standard curves for the five Q-PCR assays developed in this study were constructed (not shown). The limit of detection, corresponding to the smallest amount of template DNA resulting in positive amplification in all replicates (35, 40, 46), for B. atrophaeus genomic DNA using the ITS and recABa Q-PCR assays was 7.5 fg per PCR (2 genome equivalents). The limits of detection of S. marcescens genomic DNA using gyrB, wzm, and recASm Q-PCR assays were 7.5 fg (1 genome equivalent), 75 fg (13 genome equivalents), and 7.5 fg per PCR (1 genome equivalent), respectively. Genome equivalents were calculated assuming that one molecule of B. atrophaeus and S. marcescens DNA corresponds to 4.45 and 5.4 fg of DNA, respectively, according to equation 1 below (46) and considering a genome size of 4.2 and 5.1 Mb as determined for Bacillus subtilis subsp. subtilis strain 168 (29) and Serratia marcescens strain Db11 (information found at Sanger Institute [http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/S_marcescens/]), respectively.

|

(1) |

Quantitative amplification parameters for B. atrophaeus were optimal with linearity over an 8-log-unit dynamic range (R2 > 0.99 for both ITS and recABa Q-PCR assays), and the overall PCR amplification efficiencies for the ITS and recABa Q-PCR assays were 90.39% and 97.98%, respectively. Similarly, quantification of S. marcescens was linear over a 7-log-unit (gyrB) to 8-log-unit (recASm and wzm) dynamic range (R2 > 0.99), and the overall PCR amplification efficiencies for the gyrB, recASm, and wzm Q-PCR assays were 95.08%, 95.21%, and 96.04%, respectively. From the amplification efficiency values, it can be determined that the slopes of the standard curves were very close to the theoretical optimum of −3.32. A lower y intercept indicates greater sensitivity at a given cycle number. The y intercept values from the standard curves showed that the ITS Q-PCR assay (y intercept = 15.503) has greater sensitivity than the recABa Q-PCR assay (y intercept = 17.238), and the gyrB (y intercept = 17.354) and wzm (y intercept = 17.46) Q-PCR assays have greater sensitivity than the recASm Q-PCR assay (y intercept = 20.067).

The presence of multiple copies of genes of interest on the genome of the target organism is important because it provides a means to increase the sensitivity of the assay and allows detection of a low number of target organisms in environmental samples (36). The fact that the ITS Q-PCR assay was more sensitive than the recABa Q-PCR assay is likely due to the presence of seven copies of the 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA genes per genome in B. atrophaeus (information found at The Ribosomal RNA Operon Copy Number Database [http://rrndb.cme.msu.edu]). Data on the number of recABa gene copies in B. atrophaeus and recASm and wzm gene copies in S. marcescens could not be identified. The gyrB gene is present as a single-copy gene in all bacteria (22). The results show that gyrB, wzm, and recASm Q-PCR assays have similar amplification efficiencies that are very close to the optimal value of E = 1 (i.e., the template is doubled in each amplification cycle), and under these conditions, it is possible to calculate the number of gene copies of wzm and recASm, according to equation 2 (46):

|

(2) |

where dCT = CT (wzm or recASm) − CT(gyrB). From this equation, the calculated detectable average numbers of wzm and recASm gene copies were 1 and 0.17, respectively. The fractional copy number of recASm does not imply an actual gene copy number but a detectable copy number relative to that of gyrB. Thus, for the same mass of target DNA, gyrB and wzm Q-PCR assays will detect sixfold-more genes (1/0.17) than the recASm Q-PCR assay.

To evaluate the reproducibility of the Q-PCR assays, two experiments (experiments 1 and 2) were conducted. Each experiment consisted of triplicate standard curves generated by plotting the CT values versus log ng DNA/PCR. Experiments 1 and 2 were run on separate plates. A total of six standard curves were constructed (three standard curves/experiment). The slope, y intercept, percent efficiency, and R2 values from the three standard curves in each experiment were pooled, and the averages and standard deviations were used to calculate the intra-assay CVs (within an experiment) and interassay reproducibility (between experiments) (Table 3). The low CVs for both the inter- and intra-assay variability (0.02% to 5.36%) indicate good reproducibility of the Q-PCR standard curves. In the literature, most of the variability in Q-PCR assays has been described based on CT values and gene copy numbers (11, 51). Smith et al. (51) reported intra-assay CVs for the numbers of 16S rRNA gene copies between 3.16% and 9.09%. They also reported interassay CVs between 0.27% and 1.50% for the CT values and between 11.24% and 26.02% for the gene copy number. A similar range of CVs for the CT and gene copy number was reported by Dionisi et al. (11). In the present study, the CVs for the CT values ranged between 0.09% and 5.22% for intra-assay variability and between 0.27% and 7.37% for interassay variability.

TABLE 3.

Intra- and interassay CVs for reproducibility of the Q-PCR assays

| Q-PCR assay | CV

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

R2

|

E (%)

|

y intercept

|

Slope

|

|||||||||

| Expt 1a | Expt 2a | Expt 1 + 2b | Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Expt 1 + 2 | Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Expt 1 + 2 | Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Expt 1 + 2 | |

| ITS | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 3.24 | 1.92 | 2.43 | 0.02 | 0.61 | 5.36 | 2.35 | 1.40 | 1.78 |

| recABa | 0.74 | 0.12 | 0.82 | 1.86 | 2.28 | 2.08 | 0.93 | 0.16 | 5.00 | 1.34 | 1.66 | 1.49 |

| gyrB | 0.55 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 2.94 | 3.14 | 2.93 | 0.75 | 1.01 | 0.74 | 2.16 | 3.18 | 2.15 |

| wzm | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.42 | 3.71 | 5.12 | 3.81 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 1.94 | 2.71 | 3.85 | 2.75 |

| recASm | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 1.80 | 1.64 | 2.21 | 0.02 | 0.59 | 3.17 | 1.30 | 1.24 | 1.60 |

Intra-assay CV. Each experiment consists of triplicate Q-PCRs/assay/plate. Experiments 1 and 2 were run on separate plates.

Interassay CV for a total of six replicate Q-PCRs/assay in two separate experiments (experiments 1 and 2, with triplicate Q-PCRs/experiment).

Limits of detection and linear ranges of the Q-PCR assays in sterile water, SBD, and leachate samples spiked with surrogate organisms.

Quantitative amplification parameters for the Q-PCR assays are presented in Table 4. Amplification parameters for B. atrophaeus using the ITS Q-PCR assay were optimal, with linearity (R2 > 0.98) over a 7-log-unit dynamic range and a detection limit of 101 B. atrophaeus vegetative cells or spores (or 2 × 101 cells or spores per g of SBD or ml of leachate or sterile water), with amplification efficiencies ranging between 0.93 and 1.04 (Table 4). For comparison, the recABa Q-PCR assay was used to determine the detection limit of B. atrophaeus spores in SBD where linearity (R2 > 0.99) was over a 6-log-unit dynamic range, and the detection limit was 20 × 101 spores/g of SBD (Table 4). The fact that the amplification parameters for B. atrophaeus vegetative cells and spores in leachate samples were very similar (Table 4) suggests that the hot detergent treatment followed by bead beat homogenization was effective in spore lysis. In contrast, amplification parameters for B. atrophaeus vegetative cells and spores in SBD were different (Table 4). This difference may be because B. atrophaeus spores are hydrophobic (12) and they adhere to different solid matrices (e.g., soil and building debris), thus requiring treatment for spore recovery before lysis. Dragon and Rennie (12) reported that solutions containing both a nonionic detergent (Triton X-100 or Nonidet P-40) and buoyant concentrations of sucrose, which helps to lift spores after disruption of hydrophobic forces using nonionic detergents, improved the recovery of B. anthracis spores from soil. Similarly, Ryu et al. (48) showed that more B. anthracis spores in soil samples were detected when a solution of sucrose and Triton X-100 was used than when a solution of phosphate-buffered saline and Triton X-100 was used. In the present study, no pre-PCR treatment for spore recovery from SBD samples was made.

TABLE 4.

Quantitative amplification parameters for the Q-PCR assays in leachate and SBD

| Q-PCR assay | Sample | Target | Amplification parametera

|

Linear range (no. of cells or spores) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | Slope | y intercept | R2 | ||||

| ITS | Leachate | B. atrophaeus vegetative cells | 0.99 ± 0.07 | −3.34 ± 0.18 | 37.7 ± 0.8 | >0.98 | 101-107 |

| B. atrophaeus spores | 0.97 ± 0.04 | −3.39 ± 0.12 | 38.7 ± 0.6 | >0.98 | 101-107 | ||

| SBD | B. atrophaeus vegetative cells | 0.96 ± 0.05 | −3.42 ± 0.13 | 36.7 ± 0.6 | >0.98 | 101-107 | |

| B. atrophaeus spores | 1.04 ± 0.22 | −3.24 ± 0.52 | 39.6 ± 2.7 | >0.98 | 101-107 | ||

| Sterile water | B. atrophaeus vegetative cells | 0.93 ± 0.08 | −3.51 ± 0.21 | 38.6 ± 1.0 | >0.98 | 101-107 | |

| recABa | SBD | B. atrophaeus spores | 0.87 ± 0.01 | −3.66 ± 0.04 | 39.9 ± 0.3 | >0.99 | 102-107 |

| gyrB | Leachate | S. marcescens | 1.04 ± 0.04 | −3.24 ± 0.09 | 39.4 ± 0.6 | >0.98 | 102-107 |

| SBD | S. marcescens | 0.82 ± 0.07 | −3.85 ± 0.28 | 43.9 ± 1.4 | >0.99 | 102-107 | |

| recASm | Leachate | S. marcescens | 1.03 ± 0.05 | −3.26 ± 0.11 | 43.1 ± 0.7 | >0.97 | 102-107 |

| SBD | S. marcescens | 0.78 ± 0.03 | −3.98 ± 0.11 | 46.7 ± 0.4 | >0.99 | 102-107 | |

| wzm | Leachate | S. marcescens | 0.94 ± 0.05 | −3.47 ± 0.13 | 38.9 ± 0.5 | >0.98 | 102-107 |

| SBD | S. marcescens | 0.82 ± 0.02 | −3.86 ± 0.07 | 40.6 ± 0.4 | >0.99 | 102-107 | |

| Sterile water | S. marcescens | 0.81 ± 0.03 | −3.87 ± 0.12 | 41.2 ± 0.9 | >0.99 | 102-107 | |

The value for each parameter except R2 is a mean ± standard deviation of two DNA extractions (corresponding to two spiking experiments), each quantified in triplicate on the same plate (n = 6).

Quantitative amplification parameters for S. marcescens using the gyrB, wzm, and recASm Q-PCR assays were optimal, with linearity (R2 > 0.98) over a 6-log-unit dynamic range and a detection limit of 102 S. marcescens cells (or 20 × 101 cells per g of SBD or ml of leachate or sterile water) (Table 4). The amplification efficiencies for all three assays were higher in leachate (ranging between 0.94 and 1.04) than in SBD (ranging between 0.78 and 0.82). In addition, higher sensitivities (lower y intercept) were observed for leachate than for SBD. Although wzm and gyrB Q-PCR assays resulted in similar sensitivities when using DNA extracted from a pure bacterial culture, their sensitivities in environmental samples were different, with wzm Q-PCR assay showing higher sensitivity (Table 4). These findings suggest that the sensitivity of an assay using DNA extracted from a pure bacterial culture does not always reflect the performance of the assay in environmental samples. All five Q-PCR assays tested negative for the no-template and nonspiked samples.

To assess the variability of the Q-PCR assays between duplicate DNA extractions corresponding to duplicate spiking experiments, paired sample t tests were used, and the results showed that the difference in slopes and y intercepts among replicate standard curves obtained from two DNA extractions (corresponding to two spiking experiments), each quantified in triplicate on the same plate (n = 6), were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). These results illustrate the low variability in DNA extraction efficiencies between duplicate spiking experiments.

A major limitation of Q-PCR is the occurrence of false-negative results due to the presence of PCR inhibitors in environmental samples. Internal controls have been used by several investigators (35, 46) for the identification of false-negative PCR using TaqMan chemistry. The CT values obtained for leachate and SBD were similar to the CT values obtained for sterile water samples using the ITS and wzm Q-PCR assays (data not shown), suggesting that PCR inhibition due to the presence of nonbiological contaminants in leachate and SBD was insignificant.

Another limitation to the application of Q-PCR-based tests is the potential variability in cell lysis and DNA extraction efficiency. Therefore, this variation must be taken into consideration for reliable quantification. Several investigators (7, 26, 58) have used internal controls to quantify losses due to cell lysis and nucleic acid extraction. Although the actual target organism is the best control for quantifying losses in nucleic acid extraction, it is rarely used because of the potential natural occurrence of the target organism in the same environmental sample. To evaluate extraction efficiency, standard curves for quantification were constructed by spiking known amounts of B. atrophaeus ATCC 9372 (vegetative cells or spores) and S. marcescens ATCC 13880 cell suspensions into leachate, SBD, and sterile water. Quantification by this method corrects for losses in cell lysis and target DNA during extraction. In addition, all nonspiked samples tested in this study resulted in negative PCR, suggesting that B. atrophaeus and S. marcescens were not present in the SBD and leachate samples used in this study.

In summary, the developed Q-PCR assays are highly specific and sensitive and can be used for monitoring the fate and transport of the BW surrogates B. atrophaeus and S. marcescens in building debris and leachate samples which is our intended application. Although the assays used in this study were designed primarily for biodefense research, they could be applied to detect and quantify B. atrophaeus and S. marcescens in any sample, provided that PCR inhibition is minimal and nucleic acid extraction losses can be quantified.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the U.S. EPA through the National Homeland Security Research Center, Susan Thorneloe, Senior Project Officer.

The input of Susan Thorneloe and Paul Lemieux of the U.S. EPA is acknowledged.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 August 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball, T. K., C. R. Wasmuth, S. C. Braunagel, and M. J. Benedik. 1990. Expression of Serratia marcescens extracellular proteins requires recA. J. Bacteriol. 172:342-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belgrader, P., D. Hansford, G. T. A. Kovacs, K. Venkateswaran, R. Mariella, Jr., F. Milanovich, S. Nasarabadi, M. Okuzumi, F. Pourahmadi, and M. A. Northrup. 1999. A minisonicator to rapidly disrupt bacterial spores for DNA analysis. Anal. Chem. 71:4232-4236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buttner, M. P., P. Cruz, L. D. Stetzenbach, A. K. Klima-Comba, V. L. Stevens, and T. D. Cronin. 2004. Determination of the efficacy of two building decontamination strategies by surface sampling with culture and quantitative PCR analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4740-4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buttner, M. P., P. Cruz-Perez, and L. D. Stetzenbach. 2001. Enhanced detection of surface-associated bacteria in indoor environments by quantitative PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2564-2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chun, J., and K. S. Bae. 2000. Phylogenetic analysis of Bacillus subtilis and related taxa on partial gyrA gene sequences. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 78:123-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costafreda, M. I., A. Bosch, and R. M. Pintó. 2006. Development, evaluation, and standardization of a real-time TaqMan reverse transcription-PCR assay for quantification of hepatitis A virus in clinical and shellfish samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3846-3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czerwieniec, G. A., S. C. Russell, H. J. Tobias, M. E. Pitesky, D. P. Fergenson, P. Steele, A. Srivastava, J. M. Horn, M. Frank, E. E. Gard, and C. B. Lebrilla. 2005. Stable isotope labeling of entire Bacillus atrophaeus spores and vegetative cells using bioaerosol mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 77:1081-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dauga, C. 2002. Evolution of the gyrB gene and the molecular phylogeny of Enterobacteriaceae: a model molecule for molecular systematic studies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52:531-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Clerck, E. D., T. Vanhoutte, T. Hebb, J. Geerinck, J. Devos, and P. De Vos. 2004. Isolation, characterization, and identification of bacterial contaminants in semifinal gelatin extracts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3664-3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dionisi, H. M., G. Harmas, A. C. Layton, I. R. Gregory, J. Parker, S. A. Hawkins, K. G. Robinson, and G. S. Saylor. 2003. Power analysis for real-time PCR quantification of genes in activated sludge and analysis of the variability introduced by DNA extraction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6597-6604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dragon, D. C., and R. P. Rennie. 2001. Evaluation of spore extraction and purification methods for selective recovery of viable Bacillus anthracis spores. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 33:100-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox, G. E., J. D. Wisotzkey, and P. Jurtshuk, Jr. 1992. How close is close: 16S rRNA sequence identity may not be sufficient to guarantee species identity. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42:166-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall, T. A. 1999. BIOEDIT: a user friendly sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41:95-98. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haugland, R. A., N. Brinkman, and S. J. Vesper. 2002. Evaluation of rapid DNA extraction methods for the quantitative detection of fungi using real-time PCR analysis. J. Microbiol. Methods 50:319-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helfinstine, S. L., C. Vargus-Aburto, R. M. Uribe, and C. J. Woolverton. 2005. Inactivation of Bacillus endospores in envelopes by electron beam irradiation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:7029-7032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins, J. A., M. Cooper, L. Schroeder-Tucker, S. Black, D. Miller, J. S. Karns, E. Manthey, R. Breeze, and M. L. Perdue. 2003. A field investigation of Bacillus anthracis contamination of U.S. Department of Agriculture and other Washington, D.C., buildings during the anthrax attack of October 2001. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:593-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins, J. A., S. Nasarabadi, J. S. Karns, D. R. Shelton, M. Cooper, A. Gbakima, and R. P. Koopman. 2003. A handheld real time thermal cycler for bacterial pathogen detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 18:1115-1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higuchi, C., R. Fockler, C. Dollinger, and R. Watson. 1993. Kinetic PCR analysis: real-time monitoring of DNA amplification reactions. Bio/Technology 11:1026-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodges, L. R., L. J. Rose, A. Peterson, J. Nobel-Wang, and M. J. Arduino. 2006. Evaluation of a macrofoam swab protocol for the recovery of Bacillus anthracis spores from a steel surface. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4429-4430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffmaster, A. R., R. F. Meyer, M. P. Bowen, C. K. Marston, R. S. Weyant, G. A. Barnett, J. J. Sejvar, J. A. Jernigan, B. A. Perkins, and T. Popovic. 2002. Evaluation and validation of a real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for rapid identification of Bacillus anthracis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:1178-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, W. M. 1996. Bacterial diversity based on type II DNA topoisomerase genes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 30:79-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ibrahim, M. S., D. A. Kulesh, S. S. Saleh, I. K. Damon, J. J. Esposito, A. L. Schmaljohn, and P. B. Jahrling. 2003. Real-time PCR assay to detect smallpox virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3835-3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ivnitski, D., D. J. O'Neil, A. Gattuso, R. Schlicht, M. Calidonna, and R. Fisher. 2003. Nucleic acid approaches for detection and identification of biological warfare and infectious disease agents. BioTechniques 35:862-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwaya, A., S. Nakagawa, N. Iwakura, I. Taneike, M. Kurihara, T. Kuwano, F. Gondaria, M. Endo, K. Hatakeyama, and T. Yamamoto. 2005. Rapid and quantitative detection of blood Serratia marcescens by a real-time PCR assay: its clinical application and evaluation in a mouse infection model. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 248:163-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson, D. R., P. K. H. Lee, V. F. Holmes, and L. Alvarez-Cohen. 2005. An internal reference technique for accurately quantifying specific mRNAs by real-time PCR with application to the tceA reductive dehalogenase gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:3866-3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson, Y. A., M. Nagpal, M. T. Krahmer, K. F. Fox, and A. Fox. 2000. Precise molecular weight determination of PCR products of the rRNA intergenic spacer region using electrospray quadrupole mass spectrometry for differentiation of B. subtilis and B. atrophaeus, closely related species of bacilli. J. Microbiol. Methods 40:241-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keswani, J., M. L. Kashon, and B. T. Chen. 2005. Evaluation of interference to conventional and real-time PCR for detection and quantification of fungi in dust. J. Environ. Monit. 7:311-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kunst, F., N. Ogasawara, I. Moszer, A. M. Albertini, G. Alloni, V. Azevedo, M. G. Bertero, P. Bessieres, A. Bolotin, S. Borchert, R. Borriss, L. Boursier, A. Brans, M. Braun, S. C. Brignell, S. Bron, S. Brouillet, C. V. Bruschi, B. Caldwell, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuske, C. R., K. L. Banton, D. L. Adorda, P. C. Stara, K. K. Hill, and P. J. Jackson. 1998. Small-scale DNA sample preparation method for field PCR detection of microbial cells and spores in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2463-2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laflamme, C., S. Lavigne, J. Ho, and C. Duchaine. 2004. Assessment of bacterial endospore viability with fluorescent dyes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 96:684-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lemeieux, P., S. Thorneloe, K. Nickel, and M. Rodgers. 2006. A decision support tool (DST) for disposal of residual materials resulting from national emergencies. Air and Waste Management Association Annual Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans, LA, 20 to 23 June 2006.

- 33.Lim, D. V., J. C. Simpson, E. A. Kearns, and M. F. Kramer. 2005. Current and developing technologies for monitoring agents of bioterrorism and biowarfare. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18:583-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mainelis, G., R. L. Gorny, T. Reponen, M. Trunov, S. A. Grinshpun, P. Baron, J. Yadav, and K. Willeke. 2002. Effect of electrical charges and fields on injury and viability of airborne bacteria. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 79:229-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martín, B., A. Jofré, M. Garriaga, M. Pla, and T. Aymerich. 2006. Rapid quantitative detection of Lactobacillus saki in meat and fermented sausages by real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:6040-6048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDevitt, J. J., P. S. J. Lees, W. G. Merz, and K. J. Schwab. 2004. Development of a method to detect and quantify Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by quantitative PCR for environmental air samples. Mycopathologia 158:325-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moré, M. I., J. B. Herrick, M. C. Silva, W. G. Ghiorse, and E. L. Madsen. 1994. Quantitative cell lysis of indigenous microorganisms and rapid extraction of microbial DNA from sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1572-1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nam, H. M., V. Srinivasan, B. E. Gillespi, S. E. Murinda, and S. P. Oliver. 2005. Application of SYBR green real-time PCR for specific detection of Salmonella spp. in dairy farm environmental samples. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 102:161-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicholson, W. L., and B. Galeani. 2003. UV resistance of Bacillus anthracis spores revisited: validation of Bacillus subtilis spores as UV surrogates for spores of B. anthracis Sterne. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1327-1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Connell, K. P., J. R. Bucher, P. E. Anderson, C. J. Cao, A. S. Khan, M. V. Gostomski, and J. J. Valdes. 2006. Real-time fluorogenic transcription-PCR assays for detection of bacteriophage MS2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:478-483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oyston, P. C. F., A. Sjosted, and R. W. Titball. 2004. Tularemia: bioterrorism defense renews interest in Francisella tularensis. Nat. Rev. 2:967-978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmisano, M. M., L. K. Nakamura, K. E. Duncan, C. A. Istock, and F. M. Cohan. 2001. Bacillus sonorensis sp. nov., a close relative of Bacillus licheniformis, isolated from soil in the Sonoran Desert, Arizona. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51:1671-1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qi, Y., G. Patra, X. Liang, L. E. Williams, S. Rose, R. J. Redkar, and V. G. DelVecchio. 2001. Utilization of the rpoB gene as a specific chromosomal marker for real-time PCR detection of Bacillus anthracis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3720-3727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raber, E., and R. McGuire. 2002. Oxidative decontamination of chemical and biological warfare agents using L-Gel. J. Hazard. Mater. B93:339-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reeves, P. R., M. Hobbs, M. A. Valvano, M. Skurnik, C. Whitefield, D. Coplin, N. Kido, J. Klena, D. Maskell, C. R. Raetz, and P. D. Rick. 1996. Bacterial polysaccharide synthesis and gene nomenclature. Trends Microbiol. 4:495-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodríguez-Lázaro, D., D. A. Lewis, A. A. Ocampo-Sosa, U. Fogarty, L. Makrai, J. Navas, M. Scortti, M. Hernandez, and J. A. Vazquez-Boland. 2006. Internally controlled real-time PCR method for quantitative species-specific detection and vapA genotyping of Rhodococcus equi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4256-4263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rose, L. J., R. Donlan, S. N. Banerjee, and M. J. Ardulino. 2003. Survival of Yersinia pestis on environmental surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2166-2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryu, C., K. Lee, C. Yoo, W. K. Seong, and H. B. Oh. 2003. Sensitive and rapid detection of anthrax spores isolated from soil samples by real-time PCR. Microbiol. Immunol. 47:693-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharkey, F. H., I. M. Banat, and R. Marchant. 2004. Detection and quantification of gene expression in environmental bacteriology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3795-3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shaver, Y. J., M. L. Nagpal, R. Rudner, L. K. Nakamura, K. F. Fox, and A. Fox. 2002. Restriction fragment length polymorphism of rRNA operons for discrimination and intergenic spacer sequences for cataloging of Bacillus subtilis sub-groups. J. Microbiol. Methods 50:215-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith, C. J., D. B. Nedwell, L. F. Dong, and A. M. Osborn. 2006. Evaluation of quantitative polymerase reaction-based approaches for determining gene copy and gene transcript numbers in environmental samples. Environ. Microbiol. 8:804-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stratis-Cullum, D. N., G. D. Griffin, J. Mobley, A. A. Vass, and T. Vo-Dinh. 2003. A miniature biochip system for detection of aerosolized Bacillus globigii spores. Anal. Chem. 75:275-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szinicz, L. 2005. History of chemical and biological warfare agents. Toxicology 214:161-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and J. J. Gibson. 1994. Clustal W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequences alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties, and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turnbough, C., L. 2003. Discovery of phage display peptide ligands for species-specific detection of Bacillus spores. J. Microbiol. Methods 53:263-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Utrup, L. J., and A. H. Frey. 2004. Fate of bioterrorism-relevant viruses and bacteria, including spores, aerosolized into an indoor air environment. Exp. Biol. Med. 229:345-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Varma-Basil, M., H. El-Hajj, S. A. E. Marras, M. H. Hazbon, J. M. Mann, N. D. Connell, F. R. Kramer, and D. Alland. 2004. Molecular beacons for multiplex detection of four bacterial bioterrorism agents. Clin. Chem. 50:1060-1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Widada, J., H. Nojiri, K. Kasuga, T. Yoshida, H. Habe, and T. Omori. 2001. Quantification of the carbazole 1,9a-dioxygenase gene by real-time competitive PCR combined with co-extraction of internal standards. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 202:51-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams, R. H., E. Ward, and H. A. McCartney. 2001. Methods for integrated air sampling and DNA analysis for detection of airborne fungal spores. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2453-2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu, D., and J.-C. Côté. 2003. Phylogenetic relationships between Bacillus species and related genera inferred from comparison of 3′ and 16S rDNA and 5′ end 16S-23S ITS nucleotide sequences. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53:695-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu, S., T. P. Labuza, and F. Diez-Gonzalez. 2006. Thermal inactivation of Bacillus anthracis spores in cow's milk. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4479-4483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]