Abstract

The unique drinking patterns of college students call for Event-Specific Prevention (ESP) strategies that address college student drinking associated with peak times and events. Despite limited research evaluating ESP, many college campuses are currently implementing programming for specific events. The present paper provides a review of existing literature related to ESP and offers practical guidance for research and practice. The prevention typology proposed by DeJong and Langford (2002) provides a framework for strategic planning, suggesting that programs and policies should address problems at the individual, group, institution, community, state, and society level, and that these interventions should focus on knowledge change, environmental change, health protection, and intervention and treatment services. From this typology, specific examples are provided for comprehensive program planning related to orientation/beginning of school year, homecoming, 21st birthday celebrations, spring break, and graduation. In addition, the University of Connecticut’s efforts to address problems resulting from its annual Spring Weekend are described as an illustration of how advance planning by campus and community partners can produce a successful ESP effort.

Keywords: College, Alcohol, Prevention, Intervention, Policy

1. Overview

Over the past decades, college student drinking has received significant attention from students, parents, campus administrators, and public health officials. As a result of this process, a range of prevention and intervention programs have been developed to address heavy or high-risk drinking. Most of these interventions seek to reduce students’ overall level of alcohol consumption, and a few have shown promising results based on students’ self-reported drinking and alcohol-related consequences.

However, these programs have often failed to take into account the variability of college student drinking. That is, while an intervention program may decrease overall drinking, students might still drink heavily during events that are culturally significant or personally meaningful. In the domain of peer-reviewed research, relatively few campus-based programs have directly addressed excessive drinking associated with high-risk events.

The purpose of this paper is to review, evaluate, and propose Event-Specific Prevention (ESP) strategies that address college student drinking associated with specific times and events. We begin with an overview of college student drinking, followed by a review of existing ESP strategies. Next, we use the prevention typology introduced by DeJong and Langford (2002) to suggest a framework for event-specific strategic planning. Using this framework, we give suggestions for addressing drinking during new student orientation, homecoming, 21st birthday celebrations, spring break, and graduation. Finally, we provide a case example of how the University of Connecticut used advance planning and collaborative partnerships to reduce problems associated with its annual Spring Weekend event.

2. College Student Drinking: Characteristics and Variability

College student drinking tends to be highly variable. While rates of daily drinking are low, a significant number of students report drinking heavily on single occasions (Johnson et al., 2005; Rabow and Newman, 1984). When Del Boca and colleagues (Del Boca, Darkes, Greenbaum, & Goldman, 2004; Greenbaum, Del Boca, Darkes, Wang, & Goldman, 2005) asked students to keep a diary of their drinking over an entire academic year, three important patterns emerged: (1) drinking varied with time of year and was higher at both the start and end of the academic year; (2) drinking varied with day of the week with students drinking four times as much on the weekends as during the week; (3) drinking varied with the event calendar, with consumption at its lowest during exam periods and highest during holidays and special events. Understanding this variability helps to identify times and events that might call for targeted prevention strategies.

Community events are experienced at the same time by all students. Several holidays, including New Year’s Eve, St. Patrick’s Day, spring break, and Halloween, have been associated with excessive drinking, even among students who do not ordinarily report heavy drinking (Greenbaum et al., 2005; Lee, Maggs, & Rankin, 2006). Nationally prominent sporting events, such as the World Series and the Super Bowl, and local campus events, including orientation, graduation, homecoming, and other festivals and sporting events, especially those with tailgating parties (Neighbors et al., 2006; Nelson and Wechsler, 2003), are of concern as well.

In contrast to community events, personal events are experienced individually, and their timing varies from student to student. Celebratory drinking at a 21st birthday party is a prototypical example. Klein (1992) found that celebrating special occasions was one of the top two reasons college students reported drinking. Neighbors et al. (2005) found that 90.3% of college students reported consuming alcohol while celebrating their 21st birthday. Other events such as weddings, graduations, and major accomplishments may also involve excessive alcohol consumption.

3. Rationale for Event-Specific Prevention

Prevention efforts that focus on lowering overall drinking rates should be complemented by event-specific prevention strategies focused on community and personal events. The reason for this is clear: even when campuses succeed in reducing overall consumption levels, special events may still lead students to drink at dangerous levels. In fact, the motivation for drinking on a typical day may be quite different from the motivation for event-related drinking. Targeted efforts, attuned to the characteristics and dynamics of each event, are needed.

Another consideration is that community events often spark greater numbers of alcohol-related problems off campus, which can strain campus-community relations. Post-game riots are an extreme example, but large numbers of off-campus student parties—with attendant noise, litter, public urination, property damage, and alcohol-impaired driving—can also be a source of aggravation for community residents. On the college side, high-profile drinking events may exacerbate students’ misperceptions of campus drinking norms, which in turn can increase normative pressures to drink heavily on other occasions (Borsari & Carey, 2001).

Finally, focusing on alcohol problems tied to a specific event can energize a campus-community coalition, giving it a defined problem to solve, in contrast to the more daunting task of developing exhaustive prevention and intervention programs. Progress on event-specific prevention can serve as a springboard for a larger prevention effort, with coalition members practiced in thinking strategically and working together. While these ideas have prima facie validity, evaluations of ESP programs, especially those that include broader campus-community involvement, have been limited. The following section provides a review of the peer reviewed literature on ESP programs. To identify studies, we used a combination of database searches and manual searches of article reference lists.

4. ESP Examples from the Peer-Reviewed Literature

The literature on ESP is relatively sparse, focusing primarily on sporting events, spring break, and birthday celebrations. Regarding prevention strategies related to sports, we found three evaluations in the peer-reviewed literature focusing on policy-level interventions. Bormann and Stone (2001) evaluated a ban on alcohol in a college football stadium by comparing game-day incident data from before and after the institution of the ban. In the year following the ban, significant decreases were seen in the number of ejections from the stadium, arrests, assaults, and student referrals to the campus judicial affairs office. Season ticket holders held neutral to positive views on the ban, while students tended to hold more negative views.

Spaite et al. (1990) examined the effects of prohibiting alcohol in a college football stadium. While alcohol had never been served inside the stadium, the new ban also prohibited alcohol from being brought in. Comparing medical incident reports from before and after the ban was implemented did not suggest a significant difference in the number of injuries. The authors suggest that the lack of effect may have been due to continued drinking prior to the game, success in smuggling alcohol in to the stadium, or low alcohol consumption prior to the ban.

Johannessen et al. (2001) describe a set of environmental policies to curb the number of alcohol-related problems resulting from a university homecoming celebration. The majority of the policies focused on reducing alcohol consumption at the pre-game party on the campus mall. Policies included restrictions on where and how alcohol could be served. Additional policies prohibited alcohol displays, required servers to carry liability insurance, and increased the profile of campus police at the event. Surveys before and after the policies were instituted showed that those who thought alcohol was important or very important at homecoming decreased from 44.2% to 12.5% among students and 42.9% to 8.3% among alumni. In addition, there were fewer neighborhood complaint calls and law enforcement actions following the ban.

We were able to locate only one evaluation of a spring break intervention. Cronin (1996) compared spring break alcohol use and negative consequences between an intervention group and a no-treatment control group. The week prior to spring break, students randomly assigned to the intervention group were asked to complete a diary anticipating how much they intended to drink each day during spring break and what negative consequences they thought they might experience. The same students, along with the no-treatment control group, were asked to complete a retrospective diary the week after spring break. Students in the monitoring condition reported fewer negative consequences during spring break than the control group, illustrating the power of this simple strategy.

Published evaluations of interventions targeting celebrations have been limited to 21st birthday drinking. Many campuses have begun to send 21st birthday cards to students with messages encouraging them to celebrate sensibly. This approach was pioneered by the B.R.A.D. (Be Responsible About Drinking) organization. To date, peer-reviewed empirical support for this approach has been equivocal (Lewis et al., under review; Neighbors et al. 2005, 2006; McCue et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2006). The most recent evidence suggests that this approach may be effective when students read the information and remember the content (McCue et al, in press). As an alternative approach, Neighbors and colleagues (in preparation) recently completed a randomized trial evaluating web-based personalized feedback to reduce 21st birthday drinking. Participants in the intervention condition received personalized feedback immediately prior to their 21st birthday based on their responses to a baseline survey. Feedback focused on celebrants drinking intentions prior to their birthday and included 21st birthday specific norms, alcohol expectancies, expected consequences, personalized information regarding blood alcohol concentration, and moderation tips. Results indicated that participants in the intervention condition drank less on their 21st birthday than participants in the control group. Further evaluation of these innovative approaches is likely to teach us how to refine and further development strategies for reducing 21st birthday drinking.

Although the empirical literature is very lean, ESP approaches seem to be relatively common on many campuses. We recently sent an email request through the DRUGHIED listserv and to prevention leaders identified by the U.S. Department of Education’s Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse and Violence Prevention to ask what campuses were doing to focus on alcohol-related events. Specific events included orientation week, the first week of classes, Halloween, Cinco de Mayo, St. Patrick’s Day, sporting events (including football games and the NCAA basketball tournament), homecoming weekend, Greek rush, spring break, 21st birthdays, and a number of campus-specific events. Prevention efforts included policy restrictions, increased enforcement, substance-free alternatives (e.g., game night, karaoke, alcohol-free pub), “mocktail” competitions, and birthday cards encouraging safe celebrations. Efforts often involved a variety of departments/divisions and subdivisions (e.g., Student Affairs, Counseling Center, Residence Life) and student organizations.

It is encouraging that campuses are implementing ESP approaches even in the relative absence of attention by prevention researchers. In light of this effort, a second aim of this manuscript is to provide campus administrators with a way of systematically planning ESP interventions, by adapting the prevention typology described by DeJong and Langford (2002).

5. A Prevention Typology

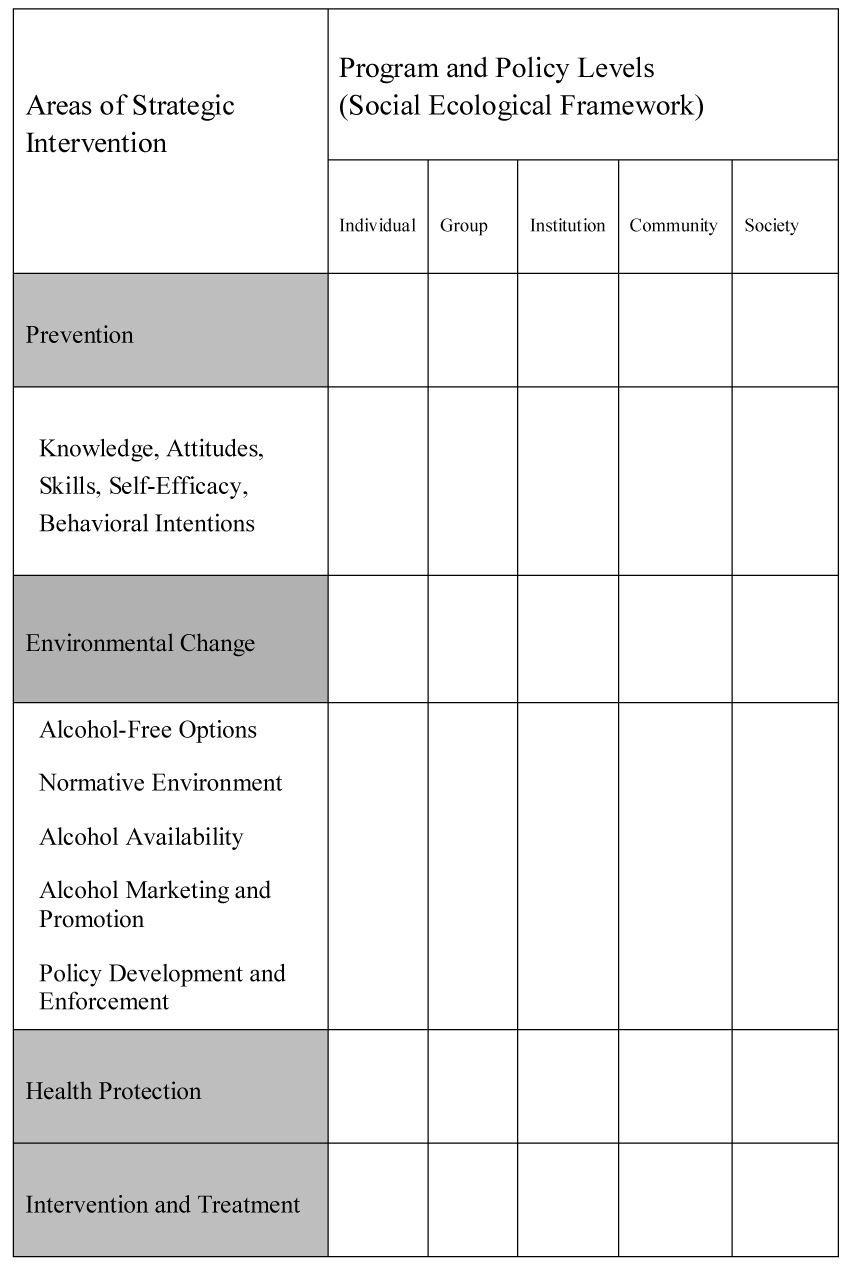

The typology matrix introduced by DeJong and Langford (2002) provides a framework for event-specific planning (see Figure 1). The typology’s first dimension is defined by the social ecological model, which classifies programs and policies into one of five levels: individual, group, institution, community, and society. The second dimension features key areas of strategic intervention: 1) changing knowledge, attitudes, skills, self-efficacy, and behavioral intentions; 2) eliminating or modifying environmental factors that contribute to problems; 3) protecting students from the negative consequences of alcohol consumption ("health protection”); and 4) intervening with students who show evidence of problematic drinking.

Figure 1.

A typology matrix for mapping campus and community prevention efforts

The environmental change category has five subgroups: 1) offer and promote social, recreational, extracurricular, and public service options that do not include alcohol; 2) create a social, academic, and residential environment that supports health-promoting norms; 3) limit alcohol availability both on- and off-campus; 4) restrict marketing and promotion of alcoholic beverages both on- and off-campus; and 5) develop and enforce campus policies and local, state, and federal laws.

The matrix captures the idea that many areas of strategic intervention can be simultaneously pursued at different levels. For example, in the realm of health protection, a campus-community coalition might organize a designated driver program for a homecoming celebration. This community-level intervention could be enhanced at the group level by having fraternity and sorority members sign pledges to use a designated driver and at the individual level by using a campus-based media campaign that encourages students to utilize the new program. Thus, the intervention is enhanced by operating at three levels.

Campus and community coalitions can categorize their existing prevention efforts for specific high-risk events along these two dimensions, and then use the typology to generate additional ideas for an extensive, but integrated intervention. Consider the example of spring break. At the institutional level, college administrators could organize alternative trips that feature volunteer work. For students remaining on campus, they could offer substance-free social events, special one-week courses, and tutoring services for students needing additional help. Faculty could be encouraged to schedule exams or papers for the week after spring break. Private institutions could look at banning spring break advertisements that glorify high-risk drinking. Looking at other levels of social ecological model, administrators could launch an education campaign that cautions students about spring break-related risks, and students could be asked to use the diary technique described above (Cronin, 1996). At the individual level, administrators could sponsor a social norms campaign to raise awareness of the norms around spring break and parents could be encouraged to visit their children on campus during the vacation week.

Table 1 offers a range of ESP strategies for orientation, homecoming, 21st birthday celebrations, spring break, and graduation, organized using the typology matrix. In the next section, we present a case study at the University of Connecticut, which illustrates how advance planning by campus and community partners can produce a successful ESP effort.

Table 1.

Examples of event-specific prevention efforts

| Event: | Orientation/Beginning of School Year |

|---|---|

| Problem: | At the beginning of the school year, academic requirements are minimal and students often have a great deal of unstructured and unsupervised time. |

| Objective: | Decrease drinking during the peak period that surrounds the beginning of the school year, especially for first-year students. |

| Examples of Strategies: | |

| Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intention | |

| |

| Environmental Change: Alcohol-Free Options, Normative Environment, Alcohol Availability, Alcohol Promotion, and Policy/Law Enforcement | |

| |

| Health Protection | |

| |

| Intervention and Treatment | |

| |

| Event: | Homecoming |

| Problem: | The homecoming game is often seen as the first major event of the school year, and is accompanied by an increase in drinking before, during, and after the event. |

| Objective: | Decrease high-risk drinking that accompanies homecoming. |

| Examples of Strategies: | |

| Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intention | |

| |

| Environmental Change: Alcohol-Free Options, Normative Environment, Alcohol Availability, Alcohol Promotion, and Policy/Law Enforcement | |

| |

| Health Protection | |

| |

| Intervention and Treatment | |

| |

| Event: | 21st Birthday |

| Problem: | A student's 21st birthday is seen as a rite of passage, and is sometimes accompanied by heavy celebratory drinking immediately upon turning 21. |

| Objective: | Decrease celebratory drinking that accompanies the 21st birthday. |

| Examples of Strategies: | |

| Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intention | |

| |

| Environmental Change: Alcohol-Free Options, Normative Environment, Alcohol Availability, Alcohol Promotion, and Policy/Law Enforcement | |

| |

| Health Protection | |

| |

| Intervention and Treatment | |

| |

| Event: | Spring Break |

| Problem: | Students may view spring Break as a collective "time out" from the normal college experience, especially if they travel away from campus, and drink much more during this week than they would ordinarily consume. |

| Objective: | Decrease high-risk drinking that accompanies spring break. |

| Examples of Strategies: | |

| Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intention | |

| |

| Environmental Change: Alcohol-Free Options, Normative Environment, Alcohol Availability, Alcohol Promotion, and Policy/Law Enforcement | |

| |

| Health Protection | |

| |

| Intervention and Treatment | |

| |

| Event: | Graduation |

| Problem: | The end of the school year is accompanied by parties and celebratory drinking. |

| Objective: | Reduce high-risk drinking associated with the end of the school year. |

| Examples of Strategies: | |

| Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavioral Intention | |

| |

| Environmental Change: Alcohol-Free Options, Normative Environment, Alcohol Availability, Alcohol Promotion, and Policy/Law Enforcement | |

| |

| Health Protection | |

| |

| Intervention and Treatment | |

| |

6. Redesigning UConn’s Spring Weekend

The annual Spring Weekend at the University of Connecticut (UConn) presented a serious problem for administrators. Unsanctioned street parties—two held at off-campus apartment buildings and one held at an on-campus parking lot—drew thousands of New England high school and college students, and resulted in well-publicized fires, vandalism, and dozens of alcohol overdoses. In response, UConn officials convened a task force in 2002 to plan a prevention effort for spring 2003. Formative research found that most students liked having a weekend to celebrate the end of the academic year, but that they were also disturbed by the destructive behavior that sometimes accompanied unsanctioned parties. With this input, the task force sought to redesign Spring Weekend, using a mix of environmental strategies to reduce high-risk drinking (Zimmerman & DeJong, 2003).

Since that time, UConn’s task force has met each fall to review its work from the previous Spring Weekend and refine its plan for the upcoming spring. By 2006, a comprehensive and integrated plan to reduce alcohol-related problems during the three-day celebration had emerged. Elements of the 2006 plan are described below, organized according to the DeJong and Langford (2002) typology.

6.1. Alcohol-Free Options

To plan the 2006 event, UConn’s Office of Alcohol and Other Drug Education and Services formed a committee consisting of undergraduate and graduate students, university staff, and police to develop a broader range of alcohol-free activities to compete with the street parties. In addition, during the fall semester, the Dean of Students wrote to student group advisors to encourage them to work with student leaders in planning campus activities for the upcoming Spring Weekend.

With the theme “Recess 2006,” the planning committee organized activities for the entire preceding week, not just the weekend itself. A website made students aware of a wide variety of activities:

Monday: a singing competition (“UConn Idol”)

Tuesday: a pep rally and an end-of-the-year picnic sponsored by UConn’s cultural centers

Wednesday: a charity car smash sponsored by the Zeta Beta Tau fraternity, a dance competition at the Center for the Performing Arts, and a “Take Back the Night” rally

Thursday: a Dodgeball tournament and a capella concert

Friday: a Founder’s Day picnic to celebrate UConn’s 125th anniversary (attended by over 10,000 people) and UConn Late Night, with a movie and a “Build-a-Bear” activity

Saturday: a breakfast buffet (designed to compete with a traditional “Kegs and Eggs” event at a nearby bar and restaurant), the traditional mud volleyball tournament, a Spring Weekend Carnival, a Fine Arts Festival featuring student artwork and musical performances, a Twister tournament, a charity 5K race, and an evening rock concert, which ended at 12:30 a.m.

To draw more people, the committee worked with the Student Alumni Association to expand the mud volleyball tournament into a carnival-like event. Student groups sponsored a range of activities, and UConn faculty and staff were encouraged to enter teams. The 2006 tournament had 930 participants, a 20 percent increase over the previous year.

6.2. Normative Environment

A student survey conducted in early 2006 revealed that 73 percent of UConn students thought allowing uninvited guests made Spring Weekend less safe. Indeed, relatively few people arrested each year were UConn students. Several ideas were implemented to discourage outsiders from coming to campus:

The Undergraduate Student Government (USG) worked to position Spring Weekend as a time of student pride, using the theme “I am UConn, We are UConn.” USG handed out t-shirts and held a student rally to promote this theme.

Identification bracelets were issued to identify UConn students and their invited guests. Campus police removed visitors who were not formal guests of UConn students and (if applicable) notified their high school or college.

Area high school principals received a letter to raise awareness of the problem and urge them to ask parents to keep their children home.

Responding to appeals from UConn officials, Eastern Connecticut State University (ECSU) scheduled several campus events aimed at keeping ECSU students from traveling to UConn during the Spring Weekend.

Additional normative approaches were employed. A student survey conducted in early 2006 revealed that fewer than half of juniors and seniors planned to attend the unsponsored events at the off-campus apartment buildings and the on-campus parking lot, the “X-Lot.” This inspired an advertisement with the headline “First you outgrew your tricycle. Then you outgrow X-Lot.”

The survey also revealed that a majority of UConn students wanted more non-alcohol events during Spring Weekend. An information campaign told students of this fact, listed the numerous activities planned for 2006 (using the headline “We Listened”), and provided the Spring Weekend website.

6.3. Policy Development and Enforcement

State and campus police collaborated to created a more visible police presence, including the deployment of 200 state police officers and 50 campus police officers, the use of plainclothes officers and a state police helicopter to monitor crowds, new equipment for detecting fake IDs, and three DWI checkpoints set up on major roads leading to campus. UConn’s Office of Judicial Affairs set up a “night court” to expedite hearings and impose immediate sanctions.

UConn officials held a press conference to outline the law enforcement efforts that would be in place on and near campus. Press conference speakers urged students to attend the sponsored activities, to watch out for their safety and that of their friends, and to call 911 if they were aware of a situation that posed a threat to anyone’s safety. The press conference also included a demonstration of standard arrest procedures that the police would be employing.

Reinforcing this message, the student newspaper ran a column about Spring Weekend, which highlighted how the new rules would be enforced. The newspaper also published an editorial, a letter from the Chief of Police, and an additional column about how to avoid drinking and driving during Spring Weekend.

6.4. Health Protection

Several measures were taken to reduce physical harm during Spring Weekend: (1) area alcohol retailers were asked in advance to sell alcohol only in cans or plastic bottles during Spring Weekend; (2) emergency medical vehicles were brought to a staging area at the X-Lot parking lot; (3) 80 nursing students trained to identify signs of alcohol poisoning were assigned to conduct rounds in residence halls; and (4) Interns from HEART House, a student alcohol and other drug rehabilitation program, helped the local hospital emergency department process any college students admitted for alcohol poisoning.

A safety pledge was widely distributed, by which, students promised to contact emergency personnel if they observed anyone showing signs of injury or alcohol poisoning and to drive sober and/or ride with a sober driver. The pledge card featured a BAC chart and information on signs of alcohol poisoning. Students returned a bottom stub from the signed pledge card to enter a raffle for autographed basketballs and an iPod. Northeast Communities Against Substance Abuse issued a student discount card recognized by local businesses, which included information on signs of alcohol poisoning.

6.5. Outcomes

Prior to 2003, 70 to 80 students were typically seen each year by medical personnel during Spring Weekend. In 2005, only 14 students were seen and in 2006, only 13 students were seen during this period. In 2002, state police made 105 arrests; these totals have steadily fallen since the program started the following spring: 2003 (n = 86), 2004 (n = 44), 2005 (n = 58), and 2006 (n = 37).

In terms of future planning, the planning committee is considering additional steps to reduce alcohol availability and to deal with problematic alcohol marketing and promotion. Specific efforts to promote intervention and treatment (e.g., advertising the availability of online alcohol screening tools and local treatment resources) are also being considered.

7. Developing ESP Strategies

Temporally fixed community and personal events are often predictable and thus provide advance notice for putting targeted prevention efforts into place. For example, a prevention-oriented educational campaign might be implemented during the week prior to St. Patrick’s Day, while other interventions designed to reduce alcohol availability and increase the visibility of law enforcement might operate on the day itself in locations where drinking is known to occur. Strategically timing an intervention may allow schools to apply limited resources in more precise concentration around specific times and events, thereby increasing the relevance and impact of the activity.

As noted previously, Table 1 lists example strategies for several specific events associated with increased student drinking. In practice, each campus will have to choose and adapt the strategies that make sense given their campus and community.

Two attributes of ESP should be considered when devising a strategic plan. First, perceived drinking norms are likely to be different for specific events than for general drinking. For example, on one campus where the perceived norm for typical number of drinks on a single occasion was just over 6 drinks, students estimated that their peers consumed an average of more then 10 drinks when celebrating their 21st birthday (Neighbors et al., 2006). Moreover, the norms for drinking on New Year’s Eve or a 21st birthday are likely to be very different than norms for a typical weekend. Thus, approaches that attempt to change general drinking norms may be perceived as irrelevant by students when deciding how much to drink during specific events.

A second attribute of ESP is that approaches found to be effective for addressing one specific event (e.g., St. Patrick’s Day) might be readily modified to address other events that present similar problems (e.g., New Year’s Eve). Likewise, efforts that show no impact on St. Patrick’s Day drinking are unlikely to have any impact on New Year’s Eve drinking. Thus, ESP strategies can be quickly assessed and revised for the next event of concern, thus maximizing the efficient use of resources.

8. Conclusions

The adaptation of existing prevention approaches to target high-risk events represents a fairly new approach to prevention. College student drinking is opportunistic, but it is not unpredictable. We know that college students tend to drink more on the weekends, at the beginning and end of the school year, and during times of celebration. In considering prevention strategies targeting these high-risk windows, it is important to recognize both the overlap among specific events as well as each event’s unique features.

This paper suggests a number of potentially useful prevention strategies for high-risk events, all of which hold promise for reducing negative consequences related to underage and excessive alcohol consumption. As college officials begin to develop and refine their ESP strategies, the dearth of published literature evaluating programs and policies for specific events underscores the need for additional formal evaluation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bormann CA, Stone MH. The effects of eliminating alcohol in a college stadium: The Folsom Field Beer Ban. Journal of American College Health. 2001;50:81–88. doi: 10.1080/07448480109596011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin C. Harm reduction for alcohol-use-related problems among college students. Substance Use & Misuse. 1996;31:2029–2037. doi: 10.3109/10826089609066450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong W, Langford LM. A typology for campus-based alcohol prevention: Moving toward environmental management strategies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002:140–147. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Up close and personal: Temporal variability in the drinking of individual college students during their first year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:155–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum PE, Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Wang CP, Goldman MS. Variation in the drinking trajectories of freshmen college students. J Consult Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:229–238. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen K, Glider P, Collins C, Hueston H, DeJong W. Preventing alcohol-related problems at the university of Arizona's homecoming: An environmental management case study. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2001;27:587–597. doi: 10.1081/ada-100104520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2004: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–45. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2005 (NIH Publication No. 05-5728)

- Klein H. Self-reported reasons for why college students drink. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 1992;37:14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Maggs JL, Rankin LA. Spring break trips as a risk factor for heavy alcohol use among first-year college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:911–916. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCue C, Greenamyer J, Atkin C, Martell D. Reaction to "Celebration Intoxication: An Evaluation of 21st Birthday Alcohol Consumption". Journal of American College Health. 2006;54:305–306. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.5.305-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Oster-Aaland L, Bergstrom RL, Lewis MA. Event- and context-specific normative misperceptions and high-risk drinking: 21st birthday celebrations and football tailgating. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:282–289. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Spieker CJ, Oster-Aaland L, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL. Celebration intoxication: An evaluation of 21st birthday alcohol consumption. Journal of American College Health. 2005;54:76–80. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.2.76-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson TF, Wechsler H. School spirits: alcohol and collegiate sports fans. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabow J, Neuman CA. Saturday night live: Chronicity of alcohol consumption among college students. Substance and Alcohol Actions/Misuse. 1984;5:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaite DW, Meislin HW, Valenzuela TD. Banning alcohol in a major college stadium: impact on the incidence and patterns of injury and illness. Journal of American College Health. 1990;39:125–128. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1990.9936223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman R, DeJong W. Safe lanes on campus: A guide for preventing impaired driving and underage drinking. Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse and Violence Prevention [On-line] 2003 Available: http://www.higheredcenter.org/pubs/safelanes/