Summary

The mechanisms underlying desensitization of serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) receptor signaling by antagonists are unclear but may involve changes in gene expression mediated via signal transduction pathways. In cells in culture, olanzapine causes desensitization of 5-HT2A receptor signaling and increases the levels of regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) 7 protein dependent on phosphorylation/activation of the Janus kinase 2 (Jak2)/signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (Stat3) signaling pathway. In the current study, the 5-HT2A receptor signaling system in rat frontal cortex was examined following 7 days of daily treatment with 0.5, 2.0 or 10.0 mg/kg i.p. olanzapine. Olanzapine increased phosphorylation of Stat3 in rats treated daily with 10 mg/kg olanzapine and caused a dose-dependent desensitization of 5-HT2A receptor-mediated phospholipase C activity. There were dose-dependent increases in the levels of membrane-associated 5-HT2A receptor, Gα11 and Gαq protein levels but no changes in the Gβ protein levels. With olanzapine treatment, RGS4 protein levels increase in the membrane-fraction and decrease in the cytosolic fraction by similar amounts suggesting a redistribution of RGS4 protein within neurons. RGS7 protein levels increase in both the membrane and cytosolic fractions in rats treated daily with10 mg/kg olanzapine. The olanzapine-induced increase in Stat3 activity could underlie the increase in RGS7 protein expression in vivo as previously demonstrated in cultured cells. Furthermore, the increases in membrane-associated RGS proteins could play a role in desensitization of signaling by terminating the activated Gαq/11 proteins more rapidly.

Keywords: antipsychotic, serotonin 2A receptor, in vivo

Introduction

Adaptive changes in post-synaptic serotonin2A/2C (5-HT2A/2C) receptor signaling may underlie the mechanism of action of several drug treatments for neuropsychiatric disorder (Roth, et al., 1998). For example, several antipsychotic drugs, such as olanzapine, desensitize both 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors (Roth, et al., 1998) while 5-HT uptake blockers (e.g., fluoxetine), can increase the maximal efficacy of 5-HT2A receptor signaling (Damjanoska, et al., 2003;Tilakaratne, et al., 1995).These adaptive changes may explain the 2-3 week delay in full symptom improvement seen with these drug treatments. However, the molecular mechanisms that underlie these adaptive changes in 5-HT2A receptor signaling are not well understood.

Treatment with many 5-HT2A receptor antagonists including olanzapine causes a decrease in the density of 5-HT2A receptor binding sites with no change in KD in rat frontal cortex and in cells in culture (Anji, et al., 2000;Kusumi, et al., 2000;Tarazi, et al., 2002;Willins, et al., 1999). Consistent with these findings, 5-HT2A receptor antagonists including clozapine and olanzapine cause 5-HT2A receptor internalization, i.e., redistribution of 5-HT2A receptors from plasma membrane to within cell bodies, both in vivo and in cells in culture (Bhatnagar, et al., 2001;Willins, et al., 1999). Internalization of a number of receptors, including 5-HT1A receptors and m1 muscarinic receptors, leads to activation of signal transduction pathways (Pierce and Lefkowitz, 2001). Sustained activation of specific intracellular signal transduction pathways, such as the Jak/Stat pathway, as would occur following internalization of 5-HT2A receptors induced by chronic antagonist treatment, could then lead to changes in gene expression and long-term changes in the 5-HT2A receptor signaling system. This receptor system is composed of 5-HT2A receptors that are coupled via Gαq/11 proteins to increase the activity of phospholipase C (PLC) (Roth, et al., 1998). Hydrolysis and thereby termination of 5-HT2A receptor-activated Gαq/11 protein signaling is enhanced by RGS4 and RGS7 proteins (Ghavami, et al., 2004;Shuey, et al., 1998).

The Jak/Stat pathway is activated by a number of G protein coupled receptors such as 5-HT2A, β2-adenoreceptors and angiotensin II receptors (Guillet-Deniau, et al., 1997;Ram and Iyengar, 2001). Activation of 5-HT2A receptors causes a rapid and transient activation of Jak2 and Stat3 (Guillet-Deniau, et al., 1997). Serotonin stimulation also induced the co-immunoprecipitation of Stat3 with Jak2 and the 5-HT2A receptor (Guillet-Deniau, et al., 1997). The Jak/Stat pathway regulates expression of a number of genes including cFos, c-Jun and c-Myc (Burysek, et al., 2002;Cattaneo, et al., 1999), transcription factors which can then stimulate expression of select genes. These transcription factors could impact directly on the expression of proteins in the 5-HT2A receptor signaling system. In A1A1v cells, a cell line that constitutively expresses the 5-HT2A receptor signaling system, 24-hour treatment with olanzapine causes desensitization of 5-HT2A receptor signaling and an increase in membrane-associated RGS7 protein that is dependent on activation of the Jak2/Stat3 pathway (Singh, et al., 2007). Based on these previous studies in cell culture and as shown in Figure 1, we hypothesize that chronic treatment with a 5-HT2A receptor antagonist causes alterations in the expression of RGS7 protein and activation of the Jak/Stat pathway in vivo.

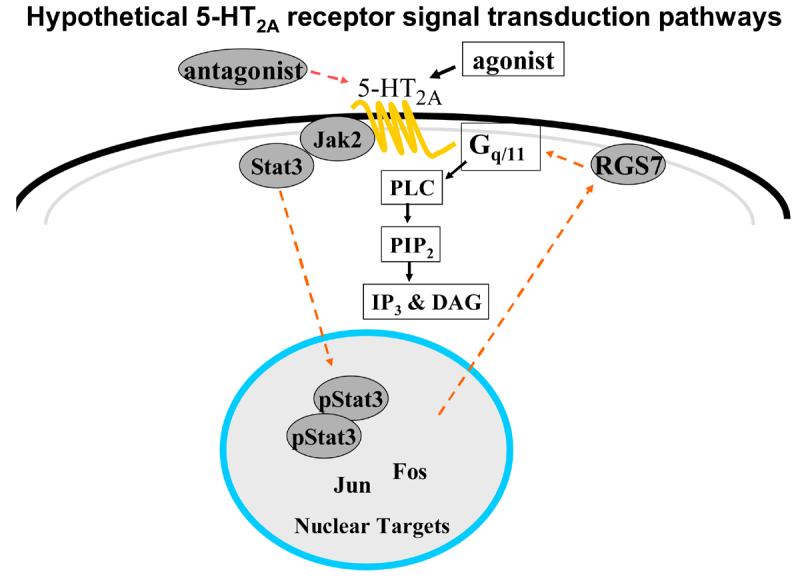

Figure 1.

5-HT2A receptor agonists cause activation of Gαq/11 proteins which in turn activate the second messenger enzyme PLC. Chronic treatment with olanzapine causes desensitization of this pathway as measured by either production of inositol phosphate in cells or PLC activity in brain tissue. We hypothesize that 5-HT2A receptor antagonism (induced by olanzapine) activates the Jak2/Stat3 pathway causing phosphorylated Stat3 to dimerize and translocate to the nucleus, stimulate immediate early genes and subsequently increase RGS7 transcription and RGS7 protein levels in the membrane. The increased membrane-associated RGS7 protein can then increase hydrolysis of activated Gαq/11 and result in desensitization of 5-HT2A receptor signaling.

Methods

Treatment

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250-275 g; Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) were housed 2 in a cage in an environment controlled for temperature, humidity, and lighting (lights on 7 am-7 pm), food and water were provided ad libitum. Rats were given 7 daily i.p. injections of olanzapine (0.5 mg/kg, 2.0 mg/kg, or 10 mg/kg) or saline. Olanzapine was chosen because it is clinically used in the treatment of schizophrenia, and it is useful in combination with fluoxetine for treatment-resistant depression, bipolar disorder and other mood disorders (Corya, et al., 2006;Marek, et al., 2003;Tohen, et al., 2003). The olanzapine doses were chosen based on previous data suggesting that a single injection of 2 mg/kg will result in peak concentrations in the clinically relevant range and repeated daily injections of 10 mg/kg/day will result in clinically relevant peak and trough concentrations of olanzapine (Kapur, et al., 2003). Rats were weighed every other day during the treatment period. On the 8th day, the rats were injected with either 1 mg/kg (-)-1-(2,5-dimethoxy-4-lodophenyl)-2-aminopropane HCl (DOI) or saline s.c. The rats were killed 30 min. post injection by guillotine. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals as approved by the Loyola University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tissue Preparation

Membrane and cytosol samples were prepared for the PLC assay and western blot procedure as previously described (Damjanoska, et al., 2004) using tissue from rats given saline challenge injections. The membrane-bound proteins were collected for the PLC activity measurements and both membrane-bound and cytosolic protein fractions were examined by immunoblot analysis. For analysis of Stat3, tissues from the DOI-challenged rats were used and were homogenized in 10 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.7, containing 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitors purchased as a cocktail (containing 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride, pepstatin A, trans-epoxysuccinyl-L-leucyl-amido(4-guanidino)butane, bestatin, leupeptin, and aprotinin) from Sigma (1.5μL/30mg tissue; St. Louis, MO). Phosphatase inhibitors (50 mM NaF and 1 mM Na3VO4) were also added to the homogenation buffer. The protein concentration was measured with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Phospholipase Cβ (PLC) Activity

PLC activity was measured in membrane fractions of rat frontal cortex as previously described using an ED50 concentration of GTPγS and an Emax concentration of serotonin (Damjanoska, et al., 2003;Wolf and Schutz, 1997). 5-HT-stimulated PLC activity in the frontal cortex is almost entirely mediated by 5-HT2A receptors, as pretreatment with 5-HT2A receptor antagonists (ketanserin, spiperone, or mianserin) inhibits most of the 5-HT-stimulated PLC activity in the frontal cortex of rats (Wolf and Schutz, 1997). Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Immunoblots

Immunoblot analysis of proteins has been described previously in detail (Damjanoska, et al., 2003). Briefly, the membrane or cytosolic proteins (10-2.5μg/lane depending on the antibody used) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated at room temperature with a blocking buffer (5% nonfat dry milk, 0.1% Triton-X100, 50 mM Tris, and 150mM NaCl). The membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with polyclonal antisera for Gα11 (D-17; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; 1:500 dilution), or Gαq (E-17; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; 1:500 dilution), RGS7 (1:15,000 dilution), or RGS4 (N-16 Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; 1:500 dilution). The 5-HT2A receptor antibody (Singh, et al., 2007) was used at a dilution of 1:100,000 with overnight incubation. Next, the membranes were incubated at room temperature with a secondary antibody. For 5-HT2A receptor, Gα11, Gαq and RGS7, we used peroxidase conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) at a 1:10,000-20,000 dilution. For RGS4, we used rabbit anti-goat IgG (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at a 1:2,000 dilution, and the blot was then incubated with goat peroxidase anti-peroxidase (ICN, Aurora, OH; 1:10,000 dilution). Membranes were incubated with monoclonal Gβ1-4 antibody (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego CA; 1:1,000) or monoclonal actin antibody (ICN, Aurora Ohio; 1:15,000) for 2 hours at room temperature followed by incubation in peroxidase conjugated goat-anti-mouse antibody at 1:5,000 for Gβ1-4 or 1:15,000 for actin. For Stat3, a polyclonal antibody from Cell Signaling (Beverly,MA) was used at 1:500 and for phospho-Stat3 (phosphorylated at Ser 727) a monoclonal antibody from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA) was used at 1:500. For both the Stat3 and phospho-Stat3, secondary antibody was used at 1:500 followed by peroxidase-anti-peroxidase at 1:1,000. Actin or Gβ1-4 protein levels were measured on all blots and used to verify equal loading of protein in gels.

All nitrocellulose membranes were incubated with ECL enhanced chemiluminescence substrate solution (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) for 1 min and then exposed to Kodak x-ray film for 5 sec – 15 min. Films were analyzed densitometrically with the Scion Image program (Fredrick, MD). Gray scale density readings were calibrated using a transmission step wedge standard. The integrated optical densities (IOD) of each band were calculated within the linear range as the sum of the densities of all of the pixels within the area of the band outlined. An area adjacent to the band was used to calculate the background density of the band. The background IOD was subtracted from the IOD of each band. The data for each sample were the means of three replications. The mean IOD values of the treated samples were calculated with respect to the average of the IOD values of saline-treated samples. Western blot assays were repeated at least three times.

[125I]-(±)-DOI Saturation Analysis

[125I]-(±)-DOI with a specific activity of 2200 Ci/mmol was purchased from Perkin-Elmer Life Science, Inc. (Boston, MA). Frontal cortex from rats treated with either olanzapine 10mg/kg/day or vehicle for 7 days was homogenized using a Tekmar Tissumizer (Cincinnati, OH) in 30 volumes of ice-cold assay buffer containing 50mM Tris pH 7.4, 0.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgSO4 (Battaglia, et al., 2000). The homogenate was centrifuged at 37,000× g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The resultant pellet was then resuspended again in the same buffer and centrifuged at 37,000× g for 15 minutes. The same process was repeated two more times, and a final membrane pellet was resuspended in assay buffer to reach a concentration of 20 mg wet weight/ml. The final amount of protein was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL).

To determine changes in the density and affinity of high-affinity 5-HT2A receptors increasing concentrations of [125I]-(±)-DOI (0.4 – 4.0 nM) were incubated with the tissue homogenates (∼50μg protein/tube) for 1.5 hour at room temperature in the same assay buffer as described above. The concentration range of [125I]-(±)-DOI was based on the KD in our previous study (Li, et al., 1997) and was over 7 times the KD. This range of ligand (0.4 – 4.0 nM) resulted in up to 86% fractional occupancy of 5-HT2A receptors. Non-specific binding was defined in the presence of 100 nM MDL 100,907, a selective 5-HT2A receptor antagonist. The reaction was terminated by rapid filtration over Whatman GF/C glass fiber filters. The filters were then washed with 15 ml ice-cold 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4). The amount of [125I]-(±)-DOI on the filters was determined by using a Micromedic 4/200 Plus γ-counter. All radioligand receptor binding assays were performed in triplicate in a final volume of 0.5 ml. Specific binding was defined as the total binding minus nonspecific binding. Bmax and KD values determined by either computer-assisted analyses of saturation data using Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) or by linear transformation of saturation data via Scatchard plots gave comparable results.

Statistics

For all statistical analyses, GB-STAT software (Dynamic Microsystems, Inc., Silver Spring, MD) was used. All data are shown as a group mean ± SEM. PLC activity and 5-HT2A receptor signaling system protein levels were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance, followed by a Newman-Keuls' post hoc analysis. Stat3 and phospho-Stat3 levels in the rats treated with 10 mg/kg olanzapine and challenged with 1 mg/kg DOI were compared to saline-treated controls challenged with 1 mg/kg DOI using a Student's t-test.

Results

Body Weight

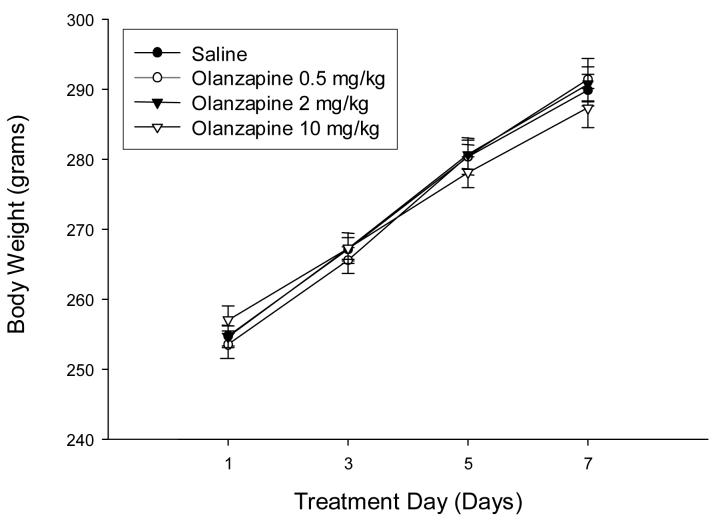

As shown in Figure 2, body weights of saline-treated rats increased over the treatment period. Unlike clinical studies with chronic olanzapine treatments in humans in which there is reported weight gain (Chrzanowski, et al., 2006), daily treatment with 0.5, 2 or 10 mg/kg olanzapine did not significantly alter weight gain over the 7 day treatment period.

Figure 2.

Rat body weight is not altered by 0.5, 2, or 10 mg/kg olanzapine injected daily for 1, 3, 5, or 7 days.

PLC Activity in Frontal Cortex

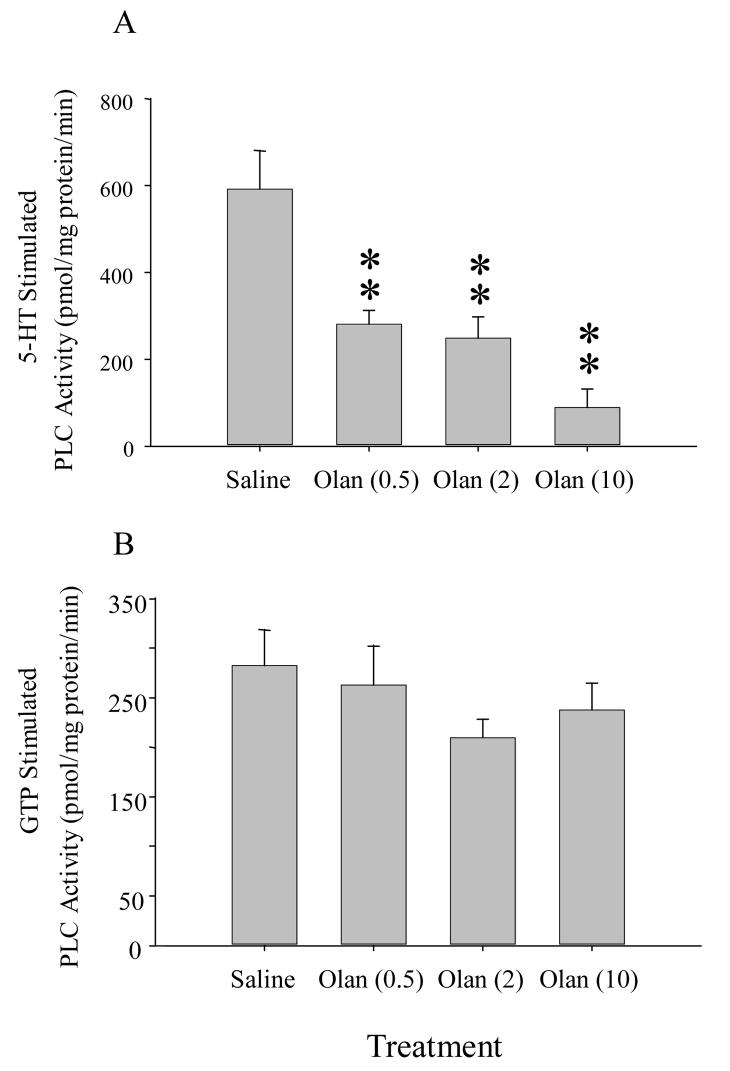

Olanzapine treatment for 7 days caused a significant decrease in 5-HT-stimulated PLC activity in the rat frontal cortex (F(3,20)= 13.39; p < 0.0001) as shown in Figure 3A. A post-hoc analysis revealed a decrease in activity by 53% with 0.5 mg/kg (p<0.01), 58% with 2 mg/kg (p<0.01), and 85% with 10 mg/kg treatment (p<0.01) (Figure 3). As further shown in Figure 3B, treatment with olanzapine did not significantly affect GTPγS-mediated PLC activity (F(3,20)= 1.01; p = 0.41). These results suggest that the ability of the activated G proteins to stimulate PLC activity is not altered by chronic olanzapine.

Figure 3.

(A) 5-HT-stimulated PLC activity in the frontal cortex was significantly attenuated by daily treatments with olanzapine for 7 days. Each dose of olanzapine (Olan), 0.5, 2.0 and 10.0 mg/kg, significantly reduced PLC activity compared to saline-treated controls (** indicates significantly different from saline-treated controls rats at p< 0.01). (B) GTPγS-stimulated-PLC activity was not altered by the olanzapine treatments.

[125I]-(±)-DOI binding in the Frontal Cortex

Treatment with 10mg/kg/day of olanzapine for 7 days produced a marked significant reduction in the high affinity state of 5-HT2A receptors. The Bmax of [125I]-(±)-DOI labeled 5-HT2A receptors was decreased by 43% in the frontal cortex of olanzapine-treated rats compared to vehicle-treat controls (Student's t-test t=-3.90 with 4 degrees of freedom, p < 0.05). In addition a small but significant (34%) increase in the KD for [125I]-(±)-DOI labeled 5-HT2A receptors was also observed in frontal cortex of olanzapine-treated rats the (Table 1) as determine by a Student's t-test (t = 6.30 with 4 degrees of freedom, p < 0.01).

Table 1.

The effects of olanzapine on [125I]-(±)-DOI binding in rat frontal cortex

| KD | Bmax | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.56 ± 0.04 (mean ± SEM) | 48.0 ± 8.6 (mean ± SEM) |

| Olanzapine | 0.75 ± 0.03 (mean ± SEM) | 27.4 ± 3.1 (mean ± SEM) |

| Percent change | 34% increase | 43% decrease |

5-HT2A Receptor Protein Levels in the Frontal Cortex

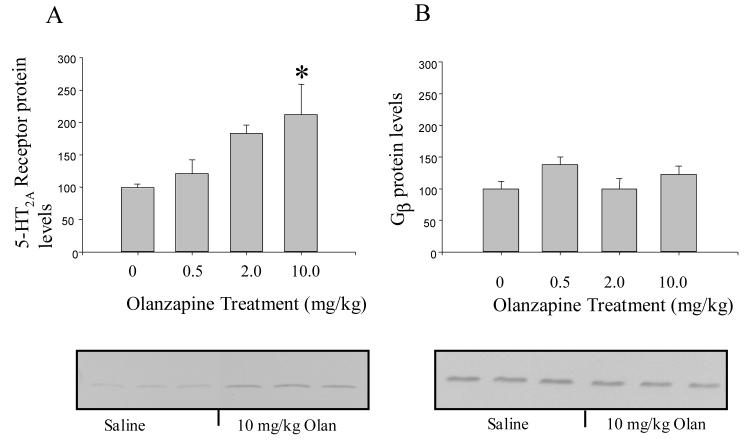

As shown in Figure 4A, membrane-associated 5-HT2A receptor protein levels in the frontal cortex were dose-dependently increased by chronic treatment with olanzapine (F(3,20) = 3.86, p < 0.05). Post-hoc analysis revealed that 5-HT2A receptor proteins levels in rats treated with 10 mg/kg olanzapine were significantly different from saline-treated control rats. The levels of the 5-HT2A receptor in rats treated with 10 mg/kg olanzapine were approximately twice the level of saline- treated control rats.

Figure 4.

(A) Olanzapine (Olan) treatment increased the membrane-associated levels of the 5-HT2A receptor protein in rat frontal cortex measured on western blots. (B) There were no changes in the levels of Gβ1-4 in the membrane fraction with olanzapine treatment. Actin was used to verify equal loading of lanes in the SDS PAGE gel. * indicates significantly different from saline-treated controls at p < 0.05.

G Protein Levels in the Frontal Cortex

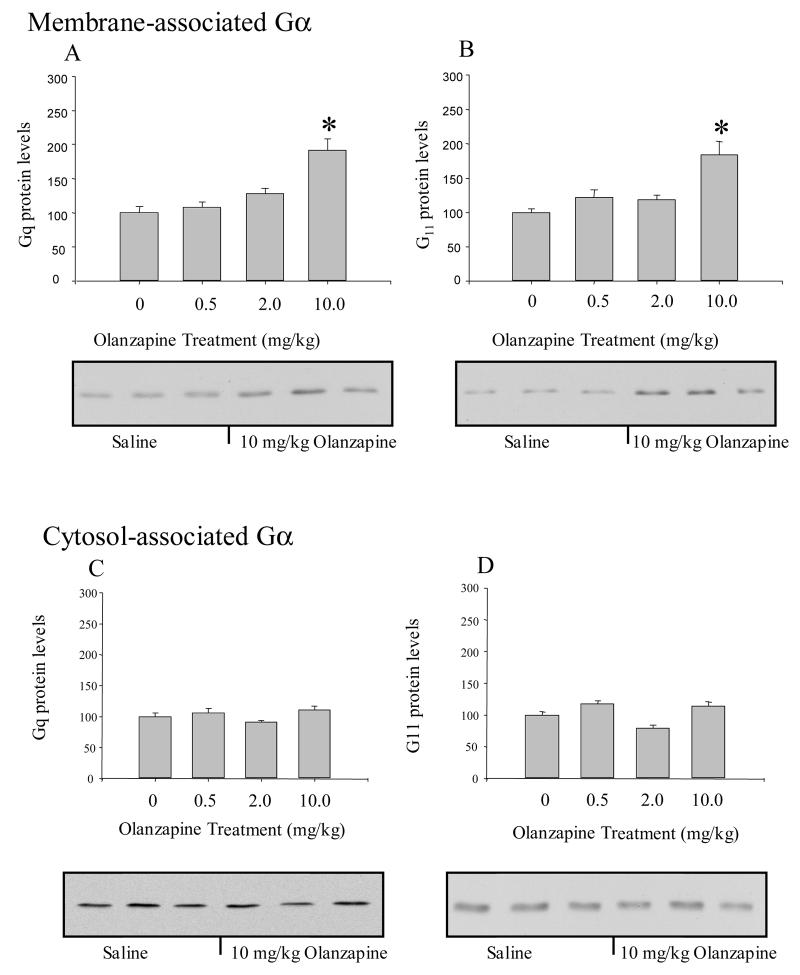

The levels of Gβ1-4 protein in the membrane-fraction of the frontal cortex of rats treated with olanzapine were not significantly different from saline-treated rats (Figure 4B). The levels of membrane-associated Gαq protein (F(3,20) = 13.20, p < 0.0001) and Gα11 protein (F(3,22) = 10.14, p < 0.001) were significantly altered by olanzapine as shown in Figure 5A & B. There were dose-dependent increases in both Gαq and Gα11 protein in the membrane fraction. In rats treated with 10 mg/kg olanzapine, the levels of both Gαq protein and Gα11 protein in the membrane fraction were approximately double the level measured in saline-treated rats. Gαq protein and Gα11 protein levels in the cytosolic fraction of the olanzapine-treated rats were not significantly different from the saline-treated control rats (Figure 5C & D).

Figure 5.

Chronic olanzapine differentially altered Gα protein levels in the cytosolic and membrane fraction of the frontal cortex as measured by western blotting. The levels of Gαq (A) and Gα11 (B) in the membrane fraction were significantly increased in the rats treated with 10 mg/kg olanzapine. In contrast, the levels of Gαq (C) and Gα11 (D) proteins in the cytosol fraction of rat frontal cortex were not significantly altered by chronic olanzapine treatments. * indicates significantly different from saline-treated control rats at p< 0.05.

RGS Protein Levels in the Frontal Cortex

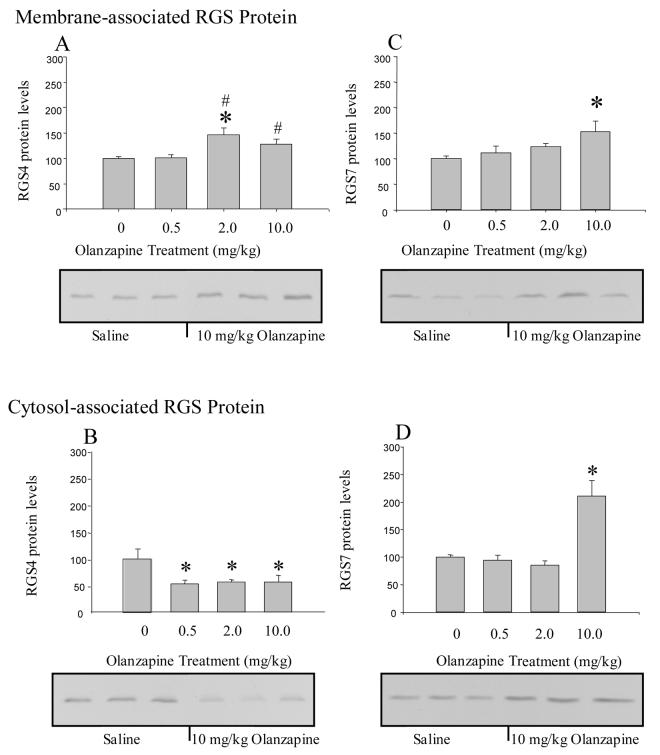

Olanzapine significantly increased the levels of RGS4 protein in the membrane fraction of the frontal cortex (F(3,23) = 6.03, p < 0.01) as shown in Figure 6A. These RGS4 protein levels were significantly higher in rats treated with 2 mg/kg (46% increased over controls) compared to saline-treated rats and rats treated with 0.5 mg/kg olanzapine (Figure 6A). RGS4 protein levels were also significantly higher in rats treated with10 mg/kg of olanzapine (28% increased over controls) compared to rats treated with 0.5 mg/kg olanzapine (Figure 6A). There were corresponding decreases (44%-43%) in the levels of RGS4 protein in the cytosolic fraction of rats treated with 2 and 10 mg/kg olanzapine (F(3,20) = 3.7, p < 0.05, Figure 6B). The levels of RGS4 protein in the cytosol were also reduced in rats treated with 0.5 mg/kg olanzapine but there were no corresponding increases in the membrane-associated levels of RGS4 protein.

Figure 6.

Chronic olanzapine differentially altered RGS4 and RGS7 protein levels in the frontal cortex. RGS4 levels in the membrane fraction (A) were increased by daily treatment with 2.0 and 10.0 mg/kg olanzapine. The levels of RGS4 in the cytosol (B) were reduced by approximately half with all doses of olanzapine. In contrast, RGS7 protein levels in the membrane (C) and cytosol (D) were significantly increased by daily injections of 10 mg/kg olanzapine. * indicates significantly different from saline-treated control rats and # indicates significantly different compared to 0.5 mg/kg olanzapine at p< 0.05.

Analysis of variance revealed that RGS7 protein levels in the membrane-fraction were significantly increased (F(3,22) = 3.69, p < 0.05) as shown in Figure 6C. The levels of RGS7 protein were also significantly increased in the cytosolic fraction of the frontal cortex of rats treated with olanzapine (F(3,20) = 14.5, p < 0.0001; Figure 6D. Post-hoc analysis revealed that RGS7 protein levels in the cytosolic fraction from rats treated with 10 mg/kg olanzapine were statistically different from saline-treated control rats; the levels of RGS7 were more than twice the levels measured in saline-treated rats (Figure 6D).

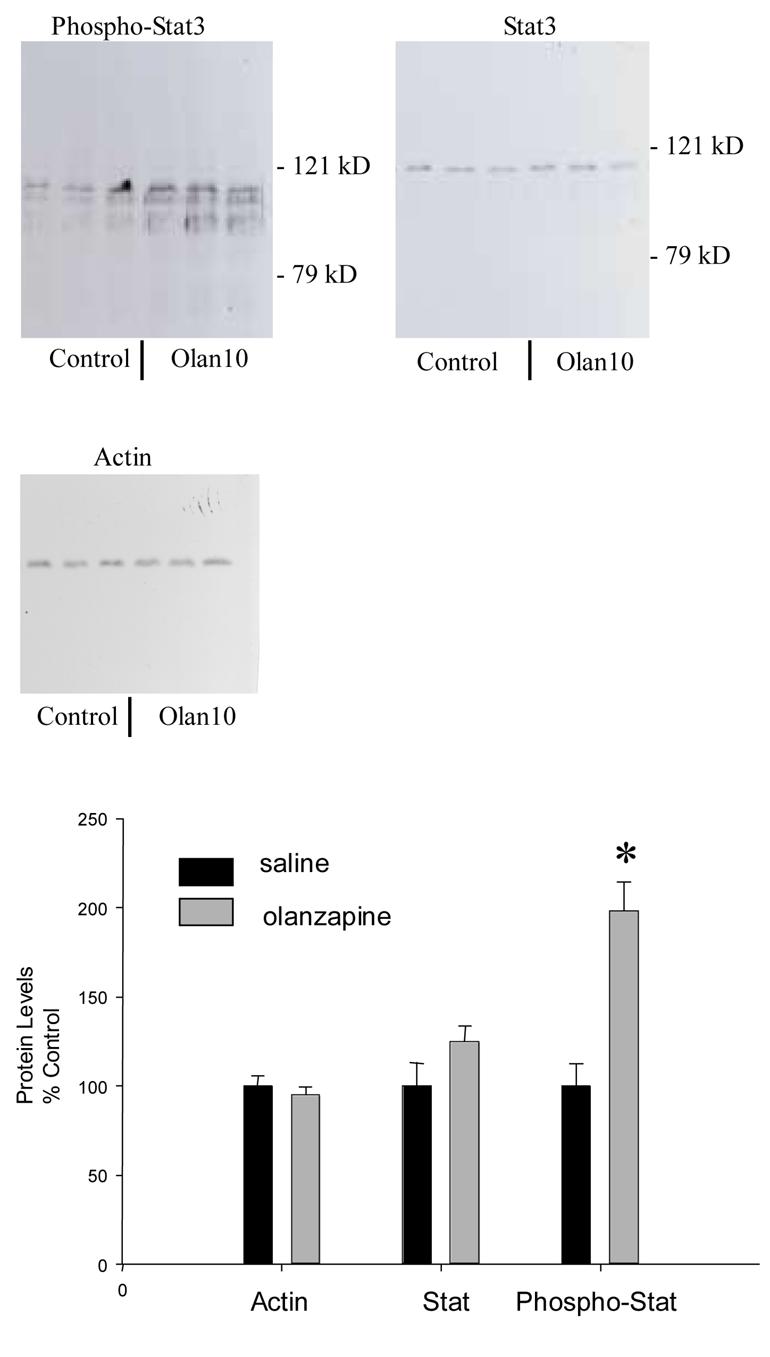

Stat3 phosphorylation

In rats treated with 10 mg/kg olanzapine daily for 7 days and DOI-stimulated 30 minutes before sacrifice, Stat3 protein phosphorylation in the frontal cortex was significantly increased to over twice the levels in saline-treated rats (t = -4.82 with 10 degrees of freedom, p < 0.001, Figure 7). As shown in Figure 7, Stat3 protein levels were not altered in the frontal cortex by chronic treatment with 10 mg/kg olanzapine.

Figure 7.

Chronic olanzapine increased Stat3 activity in the frontal cortex. The levels of phosphorylated Stat 3 were significantly increased by daily treatments of 10 mg/kg olanzapine (Olan 10). Stat protein levels were not altered by olanzapine. Actin protein levels were used to verify equal loading of lanes on the SDS-PAGE gel. * indicates significantly different from saline-treated control rats at p< 0.05.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that olanzapine treatment reduced the function of the 5-HT2A receptor signaling system, reduced the Bmax for [125I]-(±)-DOI binding, altered expression of several proximate components of the system and increased activity of the Stat3 signal transduction pathway in rat frontal cortex. PLC activity was used as an index of the function (i.e., desensitization) of the 5-HT2A receptor signaling system after chronic olanzapine treatment. Desensitization of 5-HT2A receptor signaling caused by chronic treatment with olanzapine and other 5-HT2A receptor antagonists is well established (for a review see (Gray and Roth, 2001)) and is repeated in the current study for direct comparison with the other measures such as protein expression and phosphorylation. Based on the half-life of olanzapine in rat brain of 2.5 to 5.1 hours (Aravagiri, et al., 1999;Kapur, et al., 2003) and the extensive washing of the membrane-fraction prior to the assay, olanzapine is not likely blocking 5-HT2A receptors during the performance of the PLC assay and thus not likely directly impacting 5-HT-stimulated PLC activity measurements. We found that chronic olanzapine dose-dependently decreased 5-HT-stimulated PLC activity without significantly reducing GTPγS-stimulated PLC activity. These changes in agonist-stimulated PLC activity without an accompanying change in PLC activity with direct stimulation of Gαq/11 proteins are similar to the effects produced by chronic agonist treatment (Damjanoska, et al., 2004). Our results using GTPγS to stimulate PLC activity suggest that the ability of activated Gαq/11 proteins to stimulate second messengers is not altered by chronic olanzapine. In contrast, the ability of the agonist to stimulate the activation of PLC activity is reduced by olanzapine. Taken together, these results suggest that olanzapine alters 5-HT interaction with the 5-HT2A receptors or decreases the ability of 5-HT2A receptors to activate Gαq/11 proteins.

A decrease in the ability of 5-HT2A receptors to stimulate PLC is consistent with our results showing a decrease in the Bmax of [I125] DOI labeled 5-HT2A receptors in the frontal cortex of rats treated with 10mg/kg olanzapine for 7 days. It is also consistent with previous studies that showed that 5-HT2A receptor antagonists reduce radiolabeled agonist binding to 5-HT2A receptors (Kusumi, et al., 2000;Tarazi, et al., 2002) and that 5-HT2A receptor antagonists induce internalization of 5-HT2A receptors (Willins, et al., 1999). However, immunoblot analysis demonstrated that 5-HT2A receptor protein levels in the membrane were increased rather than decreased by olanzapine treatment. Olanzapine exposure also increased the 5-HT2A receptor protein levels measured by immunoblot analysis, in A1A1v cells in culture (Singh, et al., 2007). There are at least two possible explanations for the differences between our results with immunoblot analysis of 5-HT2A receptors and our 5-HT2A receptor binding results as well as previous findings demonstrating decreased receptor binding and internalization. First, olanzapine may alter the ability of the 5-HT2A receptor protein to bind agonist or second, to bind G proteins possibly through alterations in post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation. In this scenario, total 5-HT2A receptor protein levels could increase despite a decrease in agonist binding if the post-translational modification directly reduced the number of receptors that can bind to the agonist or indirectly altered agonist binding by interfering with the ability of the receptor to bind to Gα proteins, and thus maintaining the receptors in a low affinity state. Phosphorylation of 5-HT2A receptors has been described in cells in culture (Gray, et al., 2003) and we have demonstrated phosphorylation of Gα11 protein that causes desensitization of 5-HT2A receptor signaling (Shi, et al., 2007). Considering that the 5-HT2A receptor antibody epitope is based on the primary amino acid sequence, it is feasible to obtain differences in levels of 5-HT2A receptors detected by immunoblot analysis versus changes detected by radioligand binding studies.

Additionally, we found an increase in membrane-associated RGS proteins following olanzapine treatment. An increase in membrane-associated RGS proteins would increase the termination rate of 5-HT2A receptor-Gαq/11 protein signaling by more rapidly hydrolyzing GTP, and could thereby produce or contribute to the desensitization response. When GTPγS, a non-hydrolysable GTP analog is used to activate G proteins as in our PLC assay, RGS proteins are not able to hydrolyze GTPγS bound to G proteins. Therefore, the differential effects of olanzapine on receptor versus G-protein activation of PLC activity are consistent with an increase in RGS protein as an underlying mechanism for olanzapine-induced desensitization.

Both RGS4 and RGS7 protein levels were increased in the membrane fraction following chronic treatment with olanzapine. RGS4 protein levels in the membrane were increased by an amount similar to the decrease in the cytosol with 2.0 and 10 mg/kg olanzapine treatments suggesting a redistribution of RGS4 proteins. Previous in vivo and in vitro studies demonstrated that RGS4 protein function is dependent on membrane association (Tu, et al., 2001). The redistribution of RGS4 protein following chronic olanzapine treatment would thereby increase the rate of hydrolysis of activated Gαq/11 and could contribute to the desensitization response. The mechanism whereby chronic olanzapine causes a redistribution of RGS4 protein is not clear but could be due to the increased expression of Gαq /11 protein and 5-HT2A receptor protein. A previous study demonstrated that localization of RGS protein to the membrane increases with increased expression of Gα protein (Roy et al, 2003). However, in the cell culture system used in that study, Gαi protein but not Gαq protein expression increased association of RGS4 with the cell membrane. Increased Gαo but not Gαq protein expression increased palmitoylation and membrane association of RGS7 (Takida, et al., 2005). Gα11 was not examined in that study but could also impact the distribution of RGS protein. Increased expression of receptor proteins also increases membrane association of RGS protein (Roy, et al., 2003) suggesting that increased expression of 5-HT2A receptors could also increase RGS4 protein association with the cell membrane.

RGS7 protein levels increased in both the membrane and cytosol with 10 mg/kg olanzapine treatment. Expression of RGS4 and RGS7 have been previously noted to be independent (Krumins, et al., 2004). RGS7 phosphorylation and subsequent binding to 14-3-3 sequesters RGS7 in the cytoplasm (Burchett, 2003). Furthermore, RGS7 binding to Gβ5 is necessary for stability of each protein (Chen, et al., 2003). Therefore, an increase in phosphorylation of RGS7 or increased expression of 14-3-3 or Gβ5 could increase the levels of RGS7 in the cytoplasm. RGS4 does not bind to 14-3-3 or Gβ5 as RGS7 does. In contrast with olanzapine-treatment, a similar treatment schedule with the 5-HT2A receptor agonist DOI produces 5-HT2A receptor desensitization without changing RGS7 protein expression in the frontal cortex (Damjanoska et al., 2004) possibly suggesting different underlying mechanisms for induction of desensitization with agonists versus antagonists. Our observed increase in membrane-associated RGS4 and RGS7 could both contribute to the desensitization response caused by olanzapine.

While the membrane-associated component of Gαq and Gα11 proteins increased with 10 mg/kg olanzapine treatments, the cytosolic levels of these proteins were unchanged. Our previous study in transgenic rats over-expressing Gαq protein showed a similar increase in only the membrane-associated fraction of Gαq protein and no change in the cytosolic fraction (Shi, et al., 2006). These results suggest that the membrane and cytosolic fractions are not in an equilibrium relationship since this would predict that both the membrane and cytosolic components would increase with an increase in expression of Gαq/11 proteins. The constant levels of Gαq/11 protein in the cytosol in these models suggest that the levels of Gαq/11 in the cytosol are statically regulated while membrane-associated Gαq/11 proteins are dynamic and follow expression levels of the proteins. An increase in Gαq/11 proteins would be expected when an increase rather than a decrease in 5-HT2A receptor signaling is detected and therefore the increase in membrane-associated Gαq/11 proteins could not contribute to the desensitization response caused by chronic olanzapine. Other studies in our laboratory suggest that phosphorylation of Gα11 protein contributes to desensitization of 5-HT2A receptor signaling induced by DOI treatment (Shi, et al., 2007) and could mitigate the effects of increased levels of Gα proteins. We are currently determining whether phosphorylation of Gα11 protein occurs with chronic olanzapine treatment as well.

Not all of the G proteins examined after olanzapine treatment showed an increased expression. Gβ1-4 protein levels in the membrane were not altered by chronic olanzapine treatment, demonstrating that chronic olanzapine produces selective increases in proteins associated with 5-HT2A receptor signaling.

One mechanism by which olanzapine could alter the expression levels of RGS proteins and other signaling proteins is via the increase in Stat3 activity that occurred in the frontal cortex following chronic treatment with olanzapine. We previously demonstrated in A1A1v cells, that olanzapine also increased Stat3 phosphorylation and caused a Jak2/Stat3 dependent-increase in membrane-associated RGS7 protein (Singh, et al., 2007). The Jak/Stat pathway increases immediate-early gene expression including expression of c-Fos, c-Jun and c-Myc (Burysek, et al., 2002;Cattaneo, et al., 1999). Indeed, olanzapine has been shown to increase the number of Fos-positive cells in rat frontal cortex (Sebens, et al., 1998). These transcription factors could subsequently increase expression of select genes such as those encoding Gαq, Gα11, and RGS7 proteins found to be increased in this study after chronic olanzapine treatment. The increase in 5-HT2A receptor protein levels is not dependent on Jak2/Stat3 signaling as RGS7 is in A1A1v cells (Singh et al., 2007) and may be regulated similarly in vivo.

In conclusion, chronic olanzapine caused a dose-dependent desensitization of 5-HT2A receptor signaling, a decrease in the Bmax for [125I]-(±)-DOI binding and an increase in the expression of several proteins in the 5-HT2A receptor signaling pathway in the membrane fraction of rat frontal cortex. Olanzapine caused an increase in Stat3 phosphorylation and thus an increase in activity of Stat3 that could underlie the increase in expression of these proteins in the 5-HT2A receptor pathway. Notably, the increase in RGS4 and RGS7 proteins in the membrane could contribute to the desensitization response induced by chronic olanzapine treatment. The time course for the full therapeutic effects of olanzapine in humans is 2-3 weeks while the current study examined the effects of olanzapine after only 1 week of daily treatment. Future studies are needed to determine if the changes in protein expression especially the RGS proteins are maintained with longer treatment regimens.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Susan Luecke at Eli Lilly and Company for the generous donation of olanzapine and Drs. Philip Jones and Kathleen Young (Wyeth-Ayerst Research, Princeton, N.J., U.S.A.) for their generous donation of rabbit polyclonal RGS7 antibody.

Supported by USPHS MH068612 and NS034153.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anji A, Kumari M, Hanley NRS, Bryan GL, Hensler JG. Regulation of 5-HT2A receptor mRNA levels and binding sites in rat frontal cortex by the agonist DOI and the antagonist mianserin. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:1996–2005. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aravagiri M, Teper Y, Marder SR. Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of olanzapine in rats. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1999;20:369–377. doi: 10.1002/1099-081x(199911)20:8<369::aid-bdd200>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia G, Cabrera-Vera TM, Van de Kar LD. Prenatal cocaine exposure potentiates 5-HT2A receptor function in male and female rat offspring. Synapse. 2000;35:163–172. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(20000301)35:3<163::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar A, Willins DL, Gray JA, Woods J, Benovic JL, Roth BL. The dynamin-dependent, arrestin-independent internalization of 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A (5-HT2A) serotonin receptors reveals differential sorting of arrestins and 5-HT2A receptors during endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8269–8277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchett SA. In through the out door: nuclear localization of the regulators of G protein signaling. J Neurochem. 2003;87:551–559. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burysek L, Syrovets T, Simmet T. The Serine Protease Plasmin Triggers Expression of MCP-1 and CD40 in Human Primary Monocytes via Activation of p38 MAPK and Janus Kinase (JAK)/STAT Signaling Pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33509–33517. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201941200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo E, Conti L, De-Fraja C. Signalling through the JAK-STAT pathway in the developing brain. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:365–369. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01378-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CK, Eversole-Cire P, Zhang H, Mancino V, Chen YJ, He W, Wensel TG, Simon MI. Instability of GGL domain-containing RGS proteins in mice lacking the G protein beta-subunit Gbeta5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6604–6609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631825100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrzanowski WK, Marcus RN, Torbeyns A, Nyilas M, McQuade RD. Effectiveness of long-term aripiprazole therapy in patients with acutely relapsing or chronic, stable schizophrenia: a 52-week, open-label comparison with olanzapine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;189:259–266. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0564-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corya SA, Williamson D, Sanger TM, Briggs SD, Case M, Tollefson G. A randomized, double-blind comparison of olanzapine/fluoxetine combination, olanzapine, fluoxetine, and venlafaxine in treatment-resistant depression. Depress Anxiety. 2006 doi: 10.1002/da.20130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damjanoska KJ, Heidenreich BA, Kindel GH, D'Souza DN, Zhang Y, Garcia F, Battaglia G, Wolf WA, Van de Kar LD, Muma NA. Agonist-Induced Serotonin 2A Receptor Desensitization in the Rat Frontal Cortex and Hypothalamus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:1043–1050. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.062067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damjanoska KJ, Van de Kar LD, Kindel GH, Zhang Y, D'Souza DN, Garcia F, Battaglia G, Muma NA. Chronic fluoxetine differentially affects 5- HT2A receptor signaling in frontal cortex, oxytocin and corticotropin releasing factor (CRF)- containing neurons in rat paraventricular nucleus. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:563–571. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.050534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami A, Hunt RA, Olsen MA, Zhang J, Smith DL, Kalgaonkar S, Rahman Z, Young KH. Differential effects of regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins on serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, and dopamine D2 receptor-mediated signaling and adenylyl cyclase activity. Cell Signal. 2004;16:711–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, Compton-Toth BA, Roth BL. Identification of two serine residues essential for agonist-induced 5-HT2A receptor desensitization. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10853–10862. doi: 10.1021/bi035061z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA, Roth BL. Paradoxical trafficking and regulation of 5HT2A receptors by agonists and antagonists. Brain Research Bulletin. 2001;56:441–451. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillet-Deniau I, Burnol AF, Girard J. Identification and localization of a skeletal muscle secrotonin 5-HT2A receptor coupled to the Jak/STAT pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14825–14829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, VanderSpek SC, Brownlee BA, Nobrega JN. Antipsychotic dosing in preclinical models is often unrepresentative of the clinical condition: a suggested solution based on in vivo occupancy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:625–631. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumins AM, Barker SA, Huang C, Sunahara RK, Yu K, Wilkie TM, Gold SJ, Mumby SM. Differentially regulated expression of endogenous RGS4 and RGS7. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2593–2599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311600200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumi I, Takahashi Y, Suzuki K, Kameda K, Koyama T. Differential effects of subchronic treatments with atypical antipsychotic drugs on dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in the rat brain. J Neural Transm. 2000;107:295–302. doi: 10.1007/s007020050024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Muma NA, Battaglia G, Van de Kar LD. Fluoxetine gradually increases [125I]DOI-labelled 5-HT2A/2C receptors in the hypothalamus without changing the levels of Gq- and G11-proteins. Brain Res. 1997;775:225–228. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00961-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek GJ, Carpenter LL, Mcdougle CJ, Price LH. Synergistic action of 5-HT2A antagonists and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:402–412. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce KL, Lefkowitz RJ. Classical and new roles of beta-arrestins in the regulation of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:727–733. doi: 10.1038/35094577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram PT, Iyengar R. G protein coupled receptor signaling through the Src and Stat3 pathway: role in proliferation and transformation. Oncogene. 2001;20:1601–1606. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth BL, Willins DL, Kristiansen K, Kroeze WK. 5-Hydroxytryptamine2-family (hydroxytryptamine2A, hydroxytryptamine2B, hydroxytryptamine2C): where structure meets function. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;79:231–257. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy AA, Lemberg KE, Chidiac P. Recruitment of RGS2 and RGS4 to the plasma membrane by G proteins and receptors reflects functional interactions. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:587–593. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebens JB, Koch T, ter Horst GJ, Korf J. Olanzapine-induced Fos expression in the rat forebrain; cross-tolerance with haloperidol and clozapine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;353:13–21. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00391-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Damjanoska KJ, Zemaitaitis BW, Garcia F, Carrasco GA, Sullivan NR, She Y, Young KH, Battaglia G, Van de Kar LD, Howland DS, Muma NA. Alterations in 5-HT2A receptor signaling in male and female transgenic rats overexpressing either Gq or RGS-insensitive Gq protein. Neuropharmacology. 2006;51:524–536. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Zemaitaitis B, Muma NA. Phosphorylation of Galpha11 protein contributes to agonist-induced desensitization of 5-HT2A receptor signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:303–313. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuey DJ, Betty M, Jones PG, Khawaja XZ, Cockett MI. RGS7 attenuates signal transduction through the Gαq family of heterotrimeric G proteins in mammalian cells. J Neurochem. 1998;70:1964–1972. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70051964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RK, Shi J, Zemaitaitis B, Muma NA. Olanzapine increases RGS7 protein expression via increased activation of the JAK/Stat signaling cascade. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007 doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.120386. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takida S, Fischer CC, Wedegaertner PB. Palmitoylation and plasma membrane targeting of RGS7 are promoted by alpha o. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:132–139. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.003418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarazi FI, Zhang KH, Baldessarini RJ. Long-term effects of olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine on serotonin 1A, 2A and 2C receptors in rat forebrain regions. Psychopharmacology. 2002;161:263–270. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilakaratne N, Yang ZL, Friedman E. Chronic fluoxetine or desmethylimipramine treatment alters 5-HT2 receptor mediated c-fos gene expression. Eur J Pharmacol Mol Pharmacol. 1995;290:263–266. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(95)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohen M, Vieta E, Calabrese J, Ketter TA, Sachs G, Bowden C, Mitchell PB, Centorrino F, Risser R, Baker RW, Evans AR, Beymer K, Dube S, Tollefson GD, Breier A. Efficacy of olanzapine and olanzapine-fluoxetine combination in the treatment of bipolar I depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1079–1088. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.11.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu YP, Woodson J, Ross EM. Binding of regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins to phospholipid bilayers - Contribution of location and/or orientation to GTPase-activating protein activty. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20160–20166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101599200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willins DL, Berry SA, Alsayegh L, Backstrom JR, Sanders-Bush E, Friedman L, Roth BL. Clozapine and other 5-hydroxytryptamine-2A receptor antagonists alter the subcellular distribution of 5-hydroxytryptamine-2A receptors in vitro and in vivo. Neuroscience. 1999;91:599–606. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00653-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf WA, Schutz LJ. The 5-HT2C receptor is a prominent 5-HT receptor in basal ganglia: evidence from functional studies on 5-HT-mediated phosphoinositide hydrolysis. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1449–1458. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69041449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]