Abstract

Background

Cystic fibrosis (CF) patients have enhanced renal clearance of aminoglycosides and several β-lactams and require higher dosages. Levofloxacin is a fluoroquinolone with extensive renal elimination and enhanced penetration into lungs and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) biofilms. We studied the preliminary pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) relationship of levofloxacin in CF.

Methods

Twelve patients at least 18 years old with a mild-to-moderate pulmonary exacerbation and fluoroquinolone-sensitive PA colonization received oral levofloxacin, 500 mg qd, for 14 days. Steady-state serum concentrations were collected after 3 to 7 days, and sputum samples for PA densities were collected before and after levofloxacin. PK/PD relationships for reducing PA sputum densities were evaluated.

Results

When compared to published data on non-CF patients, CF patients had similar area under the curve for 24 h (AUC24), total clearance, volume of distribution, maximum serum concentration (Cpmax), and elimination half-life: mean, 7.33 μg × h/mL/kg (SD, 1.70); 2.43 mL/min/kg (SD, 0.74); 1.33 L/kg (SD, 0.37); 7.06 μg/mL (SD, 2.35); and 6.44 h (SD, 1.1), respectively. Time to reach maximum serum concentration (Tmax) in CF was longer: mean, 2.20 h (SD, 0.99) vs 1.1 h (SD, 0.4) [p < 0.01]. Preliminary PK/PD analysis failed to demonstrate trends for decreasing PA sputum densities with increasing Cpmax/minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) ratio and AUC24/MIC ratio.

Conclusion

CF levofloxacin pharmacokinetics corrected for body weight are similar to non-CF, except for Tmax. Standard levofloxacin dosing (especially monotherapy) is unlikely to produce maximum therapeutic effectiveness. Additional levofloxacin studies in CF are necessary to evaluate its sputum concentrations; the benefits of higher daily dosages (≥ 750 mg); and establish PK/PD targets for managing PA pulmonary infections.

Keywords: cystic fibrosis, fluoroquinolones, levofloxacin, pharmacokinetics, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Fluoroquinolone antibiotics in convenient oral dosage forms are commonly prescribed in cystic fibrosis (CF) for pulmonary infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA). CF patients have rapid clearance of antibiotics that are renally excreted (eg, aminoglycosides, ceftazidime, and ticarcillin).1–4 This requires the use of higher-than-usual doses to achieve therapeutic serum concentrations.5,6 Mechanisms describing enhanced drug clearance in CF have included induction of hepatic drug metabolizing enzymes (cytochrome P-450) and enhanced renal or nonrenal clearance.7

Levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin PA susceptibility rates from clinical isolates have been reported at 67% and 68%, respectively.8 Despite limited clinical data, levofloxacin may offer some advantages in CF with better penetration into PA biofilm strains9,10; higher concentrations in alveolar macrophages, epithelial lining fluid, and lung tissue11–14; and excellent sputum penetration.15 Levofloxacin is well absorbed (99% bioavailability), minimally bound to plasma proteins (24 to 38%), and primarily eliminated unchanged in the urine (87% in 48 h).14,16 Side effects are reported at 6.2%, including diarrhea, nausea, vaginitis, flatulence, and pruritis.16

Given the extensive renal elimination of levofloxacin, we hypothesized that CF patients would clear the drug faster and are at risk of therapeutic failure when receiving a typical recommended dosage. We conducted a pharmacokinetic study in CF patients for whom a course of levofloxacin was clinically indicated.

Materials and Methods

A phase IV open-label trial was designed to characterize the pharmacokinetics of levofloxacin in adult CF patients with a mild-to-moderate pulmonary exacerbation. A preliminary pharmacodynamic analysis examining the effect on sputum pseudomonas densities was also performed. The protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board and General Clinical Research Center. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Twelve patients were recruited from the Cystic Fibrosis Adult and Pediatric Clinics at The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Inclusion criteria consisted of a diagnosis of CF, age ≥ 18 years, active mild-to-moderate pulmonary exacerbation (clinician determined), colonization with PA, and assumed sensitivity to fluoroquinolones. Patients were excluded if they had known fluoroquinolone hypersensitivity, history of seizures or diabetes, active renal insufficiency (estimated glomerular filtration rate17 [GFR] ≤ 50 mL/min/1.73 m2) or receiving high-dose ibuprofen for pulmonary inflammation. Pregnant or nursing women were also excluded. Concurrent antibiotics in another class (eg, aminoglycosides) were allowed since our primary goal was to evaluate the pharmacokinetics of levofloxacin in CF in a clinical setting.

Participants were administered one levofloxacin tablet, 500 mg qd, on an empty stomach at 9:00 pm for 14 days. Food or dairy products were allowed up until 1 h prior to or beginning 2 h after taking levofloxacin. Antacids, vitamins, minerals containing iron, or sucralfate were allowed if administered at least 2 h before or after levofloxacin administration.

After 3 to 7 days of starting levofloxacin (assumed steady state), a single set of 10 3-mL blood samples were obtained just prior to dose administration (trough) and 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h after dose administration. Samples were collected in a red-top tube, incubated at room temperature for 30 min, and then centrifuged at 1,500 to 2000 revolutions per minute for 10 min at room temperature. Resultant serum was transferred into a polypropylene vial and frozen at <− 20°C until time of assay. Serum levofloxacin concentrations were assayed in batch at the National Jewish Medical Research Center in Denver, CO, with a validated high-pressure liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection method.18 The calibration curve ranged from 0.2 to 15 μg/mL, and precision during the assay validation was 4.83% at 0.8, 8, and 14 μg/mL.19

Medical histories and physical examinations were administered at all three study visits: enrollment, pharmacokinetic blood sampling, and end of study visit (within 3 days after completing levofloxacin). Patient safety assessments included serum metabolic panel (sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, creatinine, BUN, glucose) and liver function tests (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, γ-guanosine triphosphate, and total bilirubin) at the time of enrollment and at the end of study visit. Female subjects underwent a urine pregnancy test prior to enrollment to confirm nonpregnancy status. Adverse drug reaction assessments were collected throughout, especially during the last two study visits.

For the preliminary pharmacodynamic evaluation, sputum samples were collected by expectoration prior to and after levofloxacin therapy, during study enrollment and end of study visit, respectively. Samples were shipped within8hof collection under refrigeration (2 to 8°C) to Children's Hospital and Medical Center in Seattle, WA. Samples were analyzed within 48 h of collection for PA sputum densities by techniques described by Burns and associates.20 Corresponding levofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were performed by E-test using the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute, formerly National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, MIC susceptibility breakpoints; S ≤ 2 μg/mL, I = 4 μg/mL, and R ≤ 8 μg/mL.21,22

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

Serum concentration data were analyzed by noncompartmental methods (WinNonlin Standard, version 3.1 software; Pharsight Corporation; Mountain View, CA). Individual maximum serum concentration (Cpmax) and time to reach Cpmax (Tmax) values at steady state were obtained by visual inspection of the semilogrithmic plots of serum concentrations vs time. Steady-state area under the concentration vs time curve for 24 h (AUC24) was calculated by the log-linear trapezoidal method. The elimination rate constant (λz) was determined from the slope of the terminal phase of the serum concentration vs time curve using uniform weight. The elimination half-life (T1/2) was calculated as 0.693 divided by λz. Standard equations for apparent volume of distribution (Vd/F) and total clearance (Cl/F) were used.23

Pharmacodynamic Analysis

A preliminary pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) relationship was assessed by comparing the Cpmax/MIC and AUC24/MIC ratios to the change in PA sputum density. A weighted average of the individual pretherapy PA MIC was used to perform the calculations. Prelevofloxacin and postlevofloxacin PA isolates were compared with regards to fluoroquinolone sensitivity.

Statistical Analysis

A sample size of 12 subjects was selected on the assumption that CF patients would have a 20% greater total body clearance than non-CF adults (174 ± 24.5 mL/min) and a similar variance in clearance as with non-CF adults.24 This sample size provides 84% power to detect a 12% increase in clearance and > 99% power for an increase of ≥ 20% (α =0.05, two sided).

CF pharmacokinetic parameters obtained from this study were compared to published healthy, non-CF pharmacokinetic data using a two-sided t test.24 Distributions of pretherapy and posttherapy numbers and types of levofloxacin-sensitive and levofloxacin-resistant strains were described.

Results

Demographic Data

Twelve patients, 5 men and 7 women, 18 to 37 years old were enrolled. All patients had a calculated GFR > 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 (Cockroft-Gault) at enrollment. Demographics and baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics (n = 12)*

| Variables | Data | Median |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 23.8 (5.5) | 21.5 |

| Weight, kg | ||

| All | 54.5 (10.8) | 51.05 |

| Men | 60.3 (11.5)§ | 62.3 |

| Women | 50.3 (8.6) | 50.3 |

| Height, cm | 165.5 (8.7) | 164.25 |

| Body surface area, m2† | 1.58 (0.19) | 1.53 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 19.76 (2.54) | 19.90 |

| Male/female gender | 5/7 | |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.68 (0.24) | 0.65 |

| Calculated GFR, mL/min/1.73 m2‡ | 136.2 | |

| All | 136.5 (31.7) | |

| Men | 132.3 (41.5)§ | 133.1 |

| Women | 139.5 (26.0) | 139.3 |

| Genotype | ||

| Δ508 homozygous | 8 | |

| Δ508 heterozygous | 3 | |

| S549N/R553X | 1 |

Pharmacokinetics

Mean steady-state levofloxaxin Cpmax and Tmax were 7.06 μg/mL (SD, 2.35) and 2.20 h (SD, 0.99), respectively (Table 2). Steady-state AUC24, T1/2, Cl/F, and Vd/F were based on 11 patients because 1 patient had inadequate serum sampling. The corresponding values were 71.32 μg × h/mL (SD, 24.87), 6.44 h (SD, 1.1), 130.19 mL/min (SD, 44.90), and 70.60 L (SD, 20.48), respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Levofloxacin Pharmacokinetic Analysis: Comparison by CF Status*

| Variables | CF (n = 12) | Non-CF (n = 10)† | p Value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 23.8 (5.5) | 27.5 (9.3) | NS |

| Range | 18−37 | 18−48 | |

| Weight, kg | 54.5 (10.8) | 75.5 (10.8) | < 0.001 |

| Dosage, mg/kg/d | 9.50 (1.79) | 6.73 (0.91) | < 0.001 |

| Cpmax, μg/mL | 7.06 (2.35) | 5.72 (1.4) | NS |

| Tmax, h | 2.20 (0.99) | 1.1 (0.4) | < 0.01 |

| AUC24, μg × h/mL | 71.32 (24.87)§ | 47.5 (6.7) | < 0.01 |

| T1/2, h | 6.44 (1.1)§∥ | 6.81 (1.3) | NS |

| Cl/F, mL/min | |||

| All | 130.19 (44.90) | 174.5 (24.5) | < 0.05 |

| Men | 164.03 (49.9)# | ||

| Women | 110.86 (30.2) | ||

| Vd/F, L | 70.60 (20.48)§ | 102 (21.9) | < 0.01 |

| Weight-adjusted pharmacokinetic parameters¶ | |||

| AUC24, μg × h/mL/kg | 7.33 (1.70) | 7.14 (1.20) | NS |

| Cl/F, mL/min/kg | |||

| All | 2.43 (0.74)∥ | 2.34 (0.39) | NS |

| Men | 2.84 (1.05)** | ||

| Women | 2.19 (0.43) | ||

| Vd/F, L/kg | 1.33 (0.37)∥ | 1.35 (0.15) | NS |

Data are presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated.

Normal adult data (all males) from Chien et al.24

All CF vs all non-CF by t test.

One male subject removed from the analysis due to inadequate serum sampling during the terminal phase.

Similar to 750 mg of levofloxacin in five CF patients26; T1/2 (6.8 ± 1 h), Cl/F (2.36 ± 0.49 mL/min/kg), and Vd/F (1.03 ± 0.27 L/kg), p = NS by t test (mean ± SD).

Derived from individual pharmacokinetic parameters and weights; non-CF individual pharmacokinetic and weight data provided by Ortho McNeil.

Four men vs seven women, p = 0.0522 by t test.

Four men vs seven women, p = NS by t test.

Results were compared to previously published steady-state pharmacokinetic data from healthy, non-CF adults receiving the same oral regimen24 (Table 2). Mean body weight was 28% lower in our CF patients (54.5 kg vs 75.5 kg, p < 0.001). The mean Cpmax in CF was 23% higher (7.06 mg/L vs 5.72 mg/L, p = not significant [NS]), and the T1/2 values were similar (6.44 h vs 6.81 h, p = NS). Mean Tmax and AUC24 were 100% and 50.1% higher in CF (2.2 h vs 1.1 h, p < 0.01; and 71.32 μg × h/mL vs 47.5 μg × h/mL, p < 0.01; respectively). Mean Cl/F and Vd/F were 25.2% and 30.8% lower in CF (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively). Weight-adjusted parameters of AUC24 (7.33 μg × h/mL/kg vs 7.14 μg × h/mL/kg), Cl/F (2.43 mL/min/kg vs 2.34 mL/min/kg), and Vd/F (1.33 L/kg vs 1.35 L/kg) resulted in the elimination of the aforementioned differences of the respective pharmacokinetic parameters between the groups (Table 2).

Pharmacodynamics

Two of 12 subjects did not grow an organism in either the pretherapy or posttherapy sampling periods and were not evaluated for pharmacodynamics. Six of the 10 evaluable patients had posttherapy declines in sputum PA densities. Two patients had 5-log reductions, one had a 2-log decrease, and three had 1-log reductions. Of these, five patients received concurrent synergistic antibiotics, three received inhaled tobramycin, one received inhaled colistin, and one received a course of IV antibiotics for PA. Four patients had posttherapy increases in sputum PA densities: three patients had 1-log increases, and one patient had a 50% increase. Two of these patients received concurrent inhaled tobramycin.

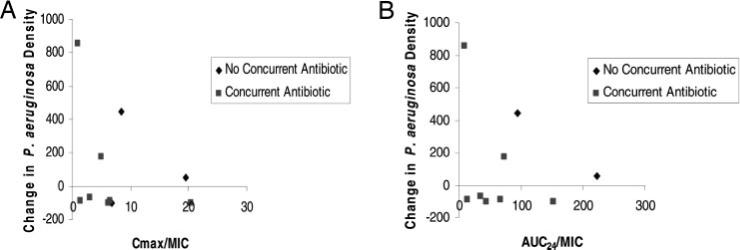

Figure 1 illustrates the preliminary PK/PD relationship of levofloxacin in our CF group. No trend for decreasing PA densities with increasing Cmax/MIC (n = 10) or AUC24/MIC (n = 9) ratios was observed. Based on suggested fluoroquinolone PK/PD targets for Gram-negative bacteria,27 only two patients achieved a Cmax/MIC ratio > 10 and an AUC24/MIC ratio > 125.

Figure 1.

PK/PD relationship of levofloxacin in CF. Left, A: Cmax/MIC ratio vs change in PA sputum density (n = 10). Right, B: AUC24/MIC ratio vs change in PA sputum density (n = 9). MIC = weighted average of pretherapy P aeruginosa MIC.

Thirty-one PA isolates were obtained prior to levofloxacin therapy and 33 isolates were obtained after therapy from all 12 subjects (Table 3). Subjects with posttherapy reductions in PA sputum density had a slight decrease in the proportion of levofloxacin-sensitive isolates (MIC ≤ 2 μg/mL), 71.4 to 68.8%; an increase in proportion of resistant isolates (MIC ≥ 8 μg/mL), 14.3 to 31.2%; and a decrease in mean MIC of sensitive isolates of 0.91 (SD, 0.67) to 0.75 (SD, 0.49). Subjects with posttherapy increases in PA sputum density had a greater decrease in percentage of sensitive isolates (86.7 to 46.3%); larger increase in percentage of resistant isolates (6.7 to 38.5%); and an increase in the mean MIC of sensitive isolates (0.66 μg/mL [SD, 0.56] to 1.4 μg/mL [SD, 0.75]).

Table 3.

Pretherapy and Posttherapy Isolate Levofloxacin PA Sensitivities in CF*

| Variables | Isolates per Patient, Mean; Median (Range) | Sensitive Isolates (≤ 2 μg/mL), No. (%)‡ | MIC of Sensitive Isolates, Mean (SD) | Intermediate Isolates, No. (%)‡ | Resistant Isolates (≥ 8 μg/mL), No. (%)‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretherapy isolates† | |||||

| All (n = 31) | 2.8; 3 (1−5) | 25 (80.6) | 0.71 (0.61) | 3 (9.7) | 3 (9.7) |

| Patients with decreased PA sputum density (n = 14)‡ | 2.3; 2.5 (1−3) | 10 (71.4) | 0.91 (0.67) | 2 (14.3) | 2 (14.3) |

| Patients with increased PA sputum density (n = 15)‡ | 3.75; 4 (2−5) | 13 (86.7) | 0.66 (0.56) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) |

| Posttherapy isolates† | |||||

| All (n = 33) | 3; 2 (1−6) | 18 (54.5) | 0.99 (0.64) | 2 (6.1) | 13 (39.4) |

| Patients with decreased PA sputum density (n = 16)‡ | 2.7; 2 (1−5) | 11 (68.8) | 0.75 (0.49) | 0 (0) | 5 (31.2) |

| Patients with increased PA sputum density (n = 13)‡ | 3.3; 2.5 (2−6) | 6 (46.2) | 1.4 (0.75) | 2 (15.4) | 5 (38.5) |

Levofloxacin PA sensitive and resistant MICs defined by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute, formerly National Committee on Clinical Laboratory Standards.21,22

One patient missing before therapy; one patient missing after therapy.

Excludes isolates from patients for whom change in posttherapy sputum density could not be determined.

Safety

There were no serious or life-threatening levofloxacin-related adverse events. Seven subjects had at least one adverse event. Of these, four patients reported insomnia that resolved after 2 days in two patients and the remaining two patients after changing the levofloxacin dosage administration time from 9:00 pm to the morning. There were two episodes each of rash and nausea, and one episode each of vomiting, pruritis, vaginitis, taste perversion, fatigue, tremor, dizziness, headache, abdominal pain, and flatulence. All adverse events were mild and transient. There were no clinically significant changes in safety laboratory values.

Discussion

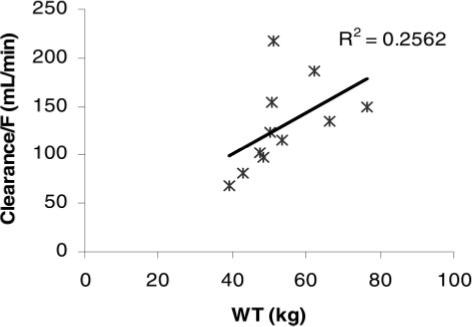

Similarities in weight-adjusted levofloxacin clearances are illustrated in Figure 2 with a proportional relationship of body weight to levofloxacin clearance in our CF patients. A similar non-CF clearance of 175 mL/min is obtained when plotting the mean non-CF weight of 75.5 kg on the graph regression line. Similar weight-adjusted volume of distribution is attributed to low-protein binding and extensive tissue and fluid distribution characteristics for levofloxacin.14,16

Figure 2.

Weight (WT) vs Cl/F in subjects with CF.

Enhanced renal excretion of antibiotics in CF may be explained by the inverse relationship between the multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein renal tubular drug transporter for secretion and CF transmembrane regulator.28–31 Despite exhibiting P-glycoprotein substrate characteristics in a kidney cell line system,32 levofloxacin renal clearance was similar in rats with or without a P-glycoprotein inhibitor.33 These conflicting results may suggest alternative drug transport mechanisms (eg, organic cation transport) as the predominant route of renal clearance. Also, renal tubular reabsorption contribution to overall levofloxacin clearance is not known.

Levofloxacin rate of oral absorption in CF is slower than non-CF, as the mean Tmax for CF was two times greater. This difference is probably due to prolonged gastric emptying in CF and is consistent with ciprofloxacin absorption in CF.34 The 23% higher Cpmax in CF was attributed to higher dosage per body weight (9.50 mg/kg/d [SD, 1.79] vs 6.73 mg/kg/d [SD, 0.91], p < 0.001). The extent of levofloxacin oral absorption was similar when normalizing AUC24 values by dosage per body weight (Table 2).

Over half of our CF subjects were women, compared to an all-male non-CF group. Despite this difference, there were no significant differences in body weight, GFR, and weight-adjusted levofloxacin clearance between gender within our CF subjects (Tables 1, 2). GFR gender differences is considered a weight effect since GFR is proportional to body weight.35

Pai and associates26 recently report a 19% decrease and 37% increase in levofloxacin Cpmax and Tmax, respectively, when levofloxacin was administered 2 h before oral antacids in CF. Our study, conducted prior to this report, allowed antacid use 2 h before or after levofloxacin. No subjects received any antacid preparation during the study; thus, the potential for an antacid absorption interaction was not present in our study. This absorption study also reported levofloxacin pharmacokinetic parameters in five CF patients receiving 750 mg/d and is currently the only published report with levofloxacin CF pharmacokinetic data available.26 Comparable pharmacokinetic parameters of T1/2, Cl/F, and Vd/F were similar to our results (Table 2).

Our small pharmacodynamic analysis supports duoantibiotic coverage, as reduction of PA sputum density was best achieved with a concurrent antipseudomonal antibiotic. Of the 10 evaluable patients, 5 of 7 patients receiving combination antipseudomonal therapy had PA sputum reductions. Two of three patients receiving levofloxacin monotherapy had elevated sputum PA after therapy. This finding is consistent with the recommendation of double antimicrobial coverage for PA infections due to potential rapid development of resistance.5

Fluoroquinolone PK/PD targets for PA have been suggested for optimal bacteriologic and clinical outcomes and minimizing resistance and are supported by in vitro and limited in vivo models.36–41 Specific clinical PK/PD PA pulmonary infection data are comprised of analyses that included patients with the same pathogen with other sites of infections (eg, wounds and urinary tract) or in patients with pulmonary infections grouped with other bacteria.42–45 Although these trials42–45 support the aforementioned targets by broader patient groups, it is not known if these PK/PD targets hold true for PA pulmonary infections in the general clinical setting due to limited sample sizes. In our study, two patients achieved the recommended PK/PD targets for efficacy of AUC24/MIC ratio > 125 and Cpmax/MIC ratio > 12. One of these patients, receiving concurrent inhaled tobramycin, had a 99% reduction in PA sputum density (Fig 1). In regards to developing resistant PA strains, 3 of 10 patients met the suggested PK/PD targets (AUC24/MIC ratio > 100 and Cpmax/MIC ratio > 8) for minimizing resistance.37,38,45 All three patients had pretherapy mean MIC isolates sensitive to levofloxacin (< 2 μg/mL). Posttherapy mean MIC isolates were resistant (> 8 μg/mL) in one patient; this patient received levofloxacin monotherapy. One of the remaining two patients also did not receive combination therapy.

Levofloxacin is well distributed into sputum, as sputum PK/PD targets of AUC24/MIC ratio > 30 and Cpmax/MIC ratio > 4.01 were associated with successful treatment of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis in non-CF patients.46 Currently, no levofloxacin sputum penetration data in CF pul- monary disease exit. Unfortunately, we did not evaluate sputum penetration in our study.

In summary, steady-state Cl/F, Vd/F, and AUC24 of levofloxacin in CF patients receiving 500 mg qd po are similar to non-CF patients when corrected for body mass. CF patients have a longer Tmax probably due to prolonged gastric emptying. Use of higher daily dosages of ≥ 750 mg should hypothetically provide more favorable PK/PD indexes of Cpmax/MIC ratio and AUC24/MIC ratio for improved clinical outcomes if tolerated. Additional studies are needed to evaluate levofloxacin sputum penetration and to determine if PK/PD targets support the bacteriologic and clinical outcomes for managing PA pulmonary infections in CF.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Noah Lechtzin, MD, Christian Merlo, MD, and Sharon Watts, RN, for their assistance in patient recruitment; and Deborah H. Schaible, PharmD (Ortho McNeil) and Joseph Massarella, PhD (Johnson and Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development) for providing the individual pharmacokinetic data of healthy subjects.

This study was supported, in part, by the Johns Hopkins University General Clinical Research Center (GCRC M01-RR00052) and the Cystic Fibrosis Therapeutic Development Network (ZEITLI03YO).

Abbreviations

- AUC24

area under concentration time curve for 24 h

- CF

cystic fibrosis

- Cl/F

total clearance

- Cpmax

maximum serum concentration

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- NS

not significant

- PA

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- PK/PD

pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic

- Tmax

time to reach maximum serum concentration

- T1/2

elimination half-life

- Vd/F

volume of distribution

Footnotes

This study was performed at The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, MD.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestjournal.org/misc/reprints.shtml).

References

- 1.Levy J, Smith AL, Koup JR, et al. Disposition of tobramycin in patients with cystic fibrosis: a prospective controlled study. J Pediatr. 1984;105:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80375-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kearns GL, Hilman BC, Wilson JT. Dosing implications of altered gentamicin disposition in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 1982;100:312–318. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80663-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leeder SJ, Spino M, Isles AF, et al. Ceftazidime disposition in acute and stable cystic fibrosis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984;36:355–362. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1984.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeGroot R, Hack BD, Weber A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of ticarcillin in patients with cystic fibrosis: a controlled prospective study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1990;47:73–78. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1990.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsey BW. Management of pulmonary disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:179–188. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607183350307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindsay CA, Boss JA. Optimisation of antibiotic therapy in cystic fibrosis patients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1993;24:496–506. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199324060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rey E, Treluyer JM, Pons G. Drug disposition in cystic fibrosis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1998;35:313–329. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199835040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlowsk JA, Jones ME, Thornsberry C, et al. Stable antimicrobial susceptibility rates for clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the 2001–2003 Tracking Resistance in the United States Today Surveillance Studies. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(suppl 2):S89–S98. doi: 10.1086/426188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shigeta M, Tanaka G, Komatsuzawa H, et al. Permeation of antimicrobial agents through Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: a simple method. Chemotherapy. 1997;43:340–345. doi: 10.1159/000239587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishida H, Ishida Y, Kurosaka Y, et al. In vitro and in vivo activities of levofloxacin against biofilm producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1641–1645. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.7.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotfried MH, Danziger LH, Rodvold KA. Steady-state plasma and intrapulmonary concentrations of levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin in healthy adult subjects. Chest. 2001;119:1114–1122. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.4.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodvold KA, Danziger LH, Gotfried MH. Steady-state plasma and bronchopulmonary concentrations of intravenous levofloxacin and azithromycin in healthy adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2450–2457. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.8.2450-2457.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagai H, Yamasaki T, Masuda M, et al. Penetration of levofloxacin into bronchoalveolar lavage fluid [abstract]. Drugs. 1993;45(suppl 3):259. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fish DN, Chow AT. The clinical pharmacokinetics of levofloxacin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32:101–119. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199732020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamori Y, Miyashita Y, Nakatani I, et al. Levofloxacin: penetration into sputum and once-daily treatment of respiratory tract infections. Drugs. 1995;49(suppl 2):418– 419. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199500492-00120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical Inc . Levaquin (levofloxacin) tablets: Levaquin (levofloxacin) injection; prescribing information. Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical; Raritan, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cockroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang H, Kays MB, Sowinski KM. Separation of levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin, moxifloxacin, trovafloxacin and cinoxacin by high-performance liquid chromatography: application to levofloxacin determination in human plasma. J Chromatograph B. 2002;772:53–63. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu M, Stambaugh JJ, Berning SE, et al. Ofloxacin population pharmacokinetics in patients with tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:503–509. doi: 10.5588/09640569513011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burns JL, Emerson J, Stapp JR, et al. Microbiology of sputum from patients at cystic fibrosis centers in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:158–163. doi: 10.1086/514631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones RN, Erwin ME, Croco JL. Critical appraisal of E test for the detection of fluoroquinolone resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996;38:21–25. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swiatlo E, Moore E, Watt J, et al. In vitro activity of four fluoroquinolones against clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa determined by the E test. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15:73–76. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibaldi M, Perrier D. Pharmacokinetics. 2nd ed. Dekker; New York, NY: 1982. pp. 409–417. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chien SC, Rogge MC, Gisclon LG, et al. Pharmacokinetic profile of levofloxacin following once-daily 500-milligram oral or intravenous doses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2256–2260. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosteller RD. Simplified calculation of body-surface area. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198710223171717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pai MP, Allen SE, Amsden GW. Altered steady state pharmacokinetics of levofloxacin in adult cystic fibrosis patients receiving calcium carbonate. J Cystic Fibrosis. 2006;5:153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pickerall KE, Paladino JA, Schentag JJ. Comparison of the fluoroquinolones based on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters. Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:417–428. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.5.417.35062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breuer W, Slotki IN, Ausiello DA, et al. Induction of multidrug resistance down regulates the expression of CFTR in colon epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:C1711–C1715. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.6.C1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trezise AEO, Romano PR, Gill DR, et al. The multidrug resistance and cystic fibrosis genes have complementary patterns of epithelia expression. EMBO J. 1992;11:4291–4303. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05528.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trezie AEO, Ratcliff R, Hawkins TE, et al. Co-ordinate regulation of the cystic fibrosis and multidrug resistance genes in cystic fibrosis knockout mice. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:527–537. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Susanto M, Benet LZ. Can the enhanced renal clearance of antibiotics in cystic fibrosis patients be explained by P-glycoprotein transport? Pharmacol Res. 2002;19:457–462. doi: 10.1023/a:1015191511817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ito T, Yano I, Tanaka K, et al. Transport of quinolone antibacterial drugs in human P-glycoprotein expressed in a kidney epithelial cell line, LLC-PK1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:955–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamaguchi H, Yano I, Saito H, et al. Pharmacokinetic role of P-glycoprotein in oral bioavailability and intestinal secretion of grepafloxacin in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:1063–1069. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.3.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed MD, Stern RC, Myers CM, et al. Lack of unique ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetics in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;28:691–699. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1988.tb03202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beierle I, Meibohm B, Berendorf H. Gender differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1999;37:529–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dursano GL, Johnson DE, Rosen M, et al. Pharmacodynamics of a fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agent in a neutropenic rat model of Pseudomonas sepsis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:483–490. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.3.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blaser J, Stone BB, Groner MC, et al. Comparative study of enoxacin and netilmicin in a pharmacodynamic model to determine importance of ratio of antibiotic peak concentration to MIC for bactericidal activity and emergence of resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1054–1060. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.7.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dudley MN, Blaser J, Gilbert D, et al. Combination therapy with ciprofloxacin plus azlocillin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: effect of simultaneous versus staggered administration in an in vitro model of infection. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:499–506. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Madaras-Kelly KJ, Ostergaard BE, Hovde LB, et al. Twentyfour hour area under the concentration-time curve/MIC ratio as a generic predictor of fluoroquinolone antimicrobial effect using three strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:627–632. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.3.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hyatt JM, Nix DE, Schentag JJ. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic activities of ciprofloxacin against strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa for which MICs are similar. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2730–2737. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.12.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomas JK, Forrest A, Bhavnai SM, et al. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of factors associated with the development of bacterial resistance in acutely ill patient during therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:521–527. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Preston SL, Drusano GL, Berman AL, et al. Pharmacodynamics of levofloxacin: a new paradigm for early clinical trials. JAMA. 1998;279:125–129. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forrest A, Nix DE, Ballow CH, et al. Pharmacodynamics of intravenous ciprofloxacin in seriously ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1073–1081. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drusano GL, Preston SL, Fowler C, et al. Relationship between fluoroquinolone area under the curve: minimum inhibitory concentration ratio and the probability of eradication of the infecting pathogen, in patients with nosocomial pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1590–1597. doi: 10.1086/383320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Forrest A, Chodosh S, Amantea MA, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral grepafloxacin in patients with acute bacterial exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40(SupplA):47–57. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.suppl_1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cazzola M, Matera MG, Donnarumma G, et al. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of levofloxacin in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. Chest. 2005;128:2093–2098. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]