Abstract

Enhanced dispersion of repolarization (DR) and refractoriness may be a unifying mechanism central to arrhythmia genesis in the long QT (LQT) syndrome. The role of DR in promoting arrhythmias was investigated in several strains of molecularly engineered mice: (a) Kv4.2 dominant negative transgenic (Kv4.2DN) that lacks the fast component of the transient outward current, Ito,f, have action potential (AP) and QT prolongation, but no spontaneous arrhythmias, (b) Kv1.4 targeted mice (Kv1.4−/−) that lack the slow component of Ito (Ito,s), have no QT prolongation and no spontaneous arrhythmias, and (c) double transgenic (Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/−) mice that lack both Ito,f and Ito,s, have AP and QT prolongation, and spontaneous ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Hearts were perfused, stained with di-4-ANEPPS and optically mapped. Activation patterns and conduction velocities were similar between the strains but AP duration at 75% recovery (APD75) was longer in Kv4.2DN (28.0 ± 2.5 ms, P < 0.01, n = 6), Kv1.4−/− (28.4 ± 0.4 ms, P < 0.01, n = 5) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (34.3 ± 2.6 ms, P < 0.01, n = 6) mice than controls (20.3 ± 1.0 ms, n = 5). Dispersion of refractoriness between apex and base was markedly reduced in Kv4.2DN (0.3 ± 0.5 ms, n = 6, P < 0.05) but enhanced in Kv1.4−/− (14.2 ± 2.0 ms, n = 5, P < 0.05) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (15.0 ± 3 ms, n = 5, P < 0.5) mice compared with controls (10 ± 2 ms, n = 5). A premature pulse elicited ventricular tachycardia (VT) in Kv1.4−/− (n = 4/5) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− hearts (n = 5/5) but not Kv4.2DN hearts (n = 0/6). Voltage-clamp recordings showed that Ito,f was 30% greater in myocytes from the apex than base which may account for the absence of DR in Kv4.2DN mice. Thus, dispersion of repolarization (DR) appears to be an important determinant of arrhythmia vulnerability.

Enhanced dispersion of repolarization (DR) and refractoriness has been implicated as an underlying mechanism of cardiac arrhythmias in patients with congenital or drug-acquired long QT syndrome (LQTS). LQTS type 1 and 2 have been linked to mutations or pharmacological inhibition of delayed rectifying K+ currents, IKs and IKr, respectively, resulting in the prolongation of cardiac action potentials (APs) (Ackerman, 1998). The prolongation of AP durations (APDs) and refractory periods produces an abnormal prolongation of the QT interval which promotes a form of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) called Torsade de Pointes (Dessertenne, 1966). However, QT prolongation alone is not sufficient to trigger polymorphic VT and enhanced DR has been proposed as an additional requirement and potential unifying mechanism for the formation of reentrant circuits central to the initiation of polymorphic VT (Smith et al. 1988; Frazier et al. 1989; Surawicz, 1989; El-Sherif et al. 1991, 1997; Shimizu & Antzelevitch, 1998).

Voltage-dependent K+ currents mediate the repolarization of the AP and hence are critical determinants of APD, refractory period (RP) and DR. In mammalian hearts, K+ channels are heterogeneously distributed across the wall of the ventricles (epicardium to endocardium) as well as along the wall (base to apex). Most studies have investigated the differential expression of various K+ currents across the wall of the left ventricle, demonstrated shorter APs in the epicardium than mid-myocardium or endocardium due to variations in the transient outward current (Ito) or the slow component of the delayed rectifier current (IKs), and attributed the ensuing regional differences of APD profile as an underlying mechanism for cardiac arrhythmias (Wit et al. 1982; Antzelevitch et al. 1991; Antzelevitch et al. 1994; Barry & Nerbonne, 1996). In contrast to transmural DR, apex–base differences in cardiac repolarization are consistently observed in hearts from different mammalian species even though they express different combinations of K+ currents. The distribution of ionic currents consistently leads to DR with shorter APDs at the apex compared with the base as demonstrated in guinea pig (Salama et al. 1987; Efimov et al. 1996), rabbit (Choi et al. 2002), mouse (Baker et al. 2000) and canine (B.R. Choi & G. Salama, unpublished observations) hearts. Moreover, single cell measurements of various K+ currents suggest that similar apex–base gradients of APDs exist in human hearts (Szentadrassy et al. 2005). This repolarization sequence from apex to base determines, in large part, the relaxation sequence of the ventricular chambers and appears to be a pattern common to all mammalian hearts that have been tested so far.

In the mouse heart, repolarization is primarily mediated by a fast component of the rapidly activating, rapidly inactivating transient outward current encoded by Kv4.3 and Kv4.2 (Ito,f), a more slowly inactivating component of the transient outward current encoded by Kv1.4 (Ito,s), a rapidly activating slowly inactivating 4-aminopyridine (4-AP)-sensitive current encoded by Kv1.5 (IK,slow1), a rapidly activating slowly inactivating 4-AP-insensitive current encoded by Kv2.1 (IK,slow2), and a steady-state current (Iss). (Xu et al. 1999a; Nerbonne, 2000) The differential expression of Ito,f and Ito,s contributes to regional heterogeneities in ventricular repolarization (apex–base, endocardium–epicardium, septum–ventricular free wall) and may have profound effects on susceptibility to life-threatening arrhythmias (London et al. 1998b; Xu et al. 1999a; Guo et al. 2000; Brunet et al. 2004). Dominant negative mice overexpressing an N-terminal fragment of Kv1.1 lack IK,slow1 and Ito,s, have cardiac AP and QT prolongation, and spontaneous and inducible ventricular tachyarrhythmias due to enhanced DR between apex and base (Baker et al. 2000). Transgenic mice targeting the components of Ito show varying degrees of APD and QT prolongation that do not directly correlate with the arrhythmia susceptibility (Barry et al. 1998; London et al. 1998b; Guo et al. 2000). In the present report, we investigated the influence of DR on the vulnerability to arrhythmias in molecularly engineered mouse models which lack Ito,f, Ito,s, or both Ito,f and Ito,s., and test whether the arrhythmia phenotype in these models of long QT is determined by the regional distribution of the repolarizing K+ currents and DR. We applied voltage-sensitive dyes and optical mapping techniques to Langendorff perfused hearts to investigate the link between vulnerability to arrhythmias, the elimination of specific K+ currents, and changes in the dispersion of repolarization and refractoriness. In addition, whole-cell voltage-clamp experiments were used to analyse differences of It.o and IK,slow in myocytes isolated from the apex and base to identify the determinants of DR in the mouse heart.

Methods

Transgenic and gene-targeted mouse models

All animal procedures complied with NIH guidelines and were approved by the IACUC of the University of Pittsburgh. We used three molecular engineered lines of mice: (1) The Kv4.2DN dominant negative transgenic mouse was developed by a point mutation (W to F) introduced at position 362 in the pore region of Kv4.2 which produced a non-conducting mutant α-subunit of Kv4.2 channels that co-assembled with Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 and eliminated Ito,f (Barry et al. 1998). Kv4.2DN mice have an up-regulation of Kv1.4 and Ito,s in the ventricular walls outside the septum, prolongation of APD in isolated myocytes and QT intervals in EKG recordings, but no spontaneous arrhythmias on ambulatory telemetry monitoring (Barry et al. 1998; Xu et al. 1999b). (2) Kv1.4−/− mice were engineered by targeted disruption in embryonic stem cells, which selectively eliminated Ito,s, a current present only in cells from the interventricular septum (London et al. 1998b; Guo et al. 1999b, 2000). Kv1.4−/− mice have normal QT intervals and no spontaneous arrhythmias on ambulatory telemetry monitoring. (3) Kv4.2DN and Kv1.4−/− mice were crossed to eliminate both Ito,f and Ito,s (Guo et al. 2000). Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− mice have prolongation of APD in myocytes, QT interval prolongation on EKG recordings, and spontaneous episodes of VT on ambulatory telemetry monitoring (Guo et al. 2000).

Each of the three lines of mice had normal cardiac morphology and no evidence of hypertrophy or heart failure. The Kv4.2DN mice were either engineered on a C57Black6 background while the Kv1.4−/− mice were initially engineered on a SV129 background and were backcrossed into C57Black6 for more than five generations. C57Black6 littermates were used for control experiments.

Perfusion of mouse hearts

Female C57Black6, Kv4.2DN, Kv1.4−/−, and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− mice were anaesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg kg−1) and heparinized (35 mg kg−1) with an intraperitoneal injection. The heart was rapidly excised, cannulated, placed in a chamber specially designed to immobilize the ventricles (see Fig. 1A) paced, and the anterior surface of the heart was imaged on a photodiode array. The perfusate contained (mm): 112 NaCl, 1.0 KH2PO4, 25.0 NaHCO3, 1.2 MgSO4, 5.0 KCl, 50.0 dextrose, 1.8 CaCl2, at pH 7.4 and was gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Perfusion pressure was adjusted to 60–80 mmHg by controlling the flow rate of a peristaltic pump. The temperature of the bath surrounding the heart was kept at 37°C by continuously monitoring the temperature with a thermistor, which controlled a heating coil located in the back of the chamber, via a feedback amplifier. All recordings were made in the absence of chemical uncouplers such as diacetyl monoxime or cytochalasin D. Motion artifacts were suppressed by mechanical stabilization with the chamber and extensive controls were carried out to insure that immobilization of the heart did not make the heart ischaemic, as previously described (Baker et al. 2000, 2004; London et al. 2003). Hearts were stained with the voltage-sensitive dye di4-ANEPPS by injecting 10 μl of stock solution (1 mg dye per ml dimethyl sulfoxide) in the compliance chamber and bubble trap located 3 cm above the heart. The study was carried out with female mice to avoid possible sex differences in ion channel expression (Trepanier-Boulay et al. 2001; Brunet et al. 2004) and/or arrhythmia phenotype (Drici et al. 2002). In addition, female rather than male mice were used to avoid variation in K+ channel expression known to occur with differences in testosterone levels (Brouillette et al. 2005).

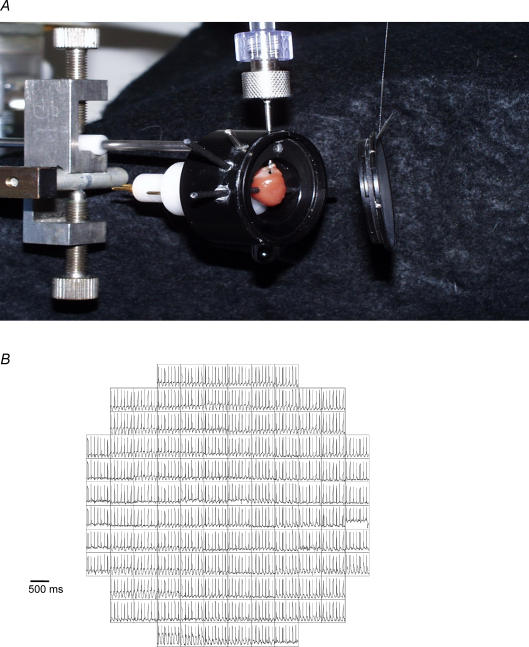

Figure 1. Chamber assembly and photodiode array.

A, a digital picture of cannula and chamber assembly used in our experiments. The chamber assembly consisted of the following three parts: the main frame, a glass window which locks onto the front of the main frame, and a Teflon cylinder which was inserted in the rear of the main frame. The main frame functioned to hold the aortic cannula and fasten the thermistor and recording and stimulating electrodes firmly in place on the heart. The Telfon cylinder contains a heating coil to control the bath temperature around the heart. B, an illustration of 124 optical APs recorded from a control heart; the array viewed 4 mm × 4 mm of left ventricle, with each box representing a diode and APs recorded by that diode were displayed as a symbolic map in their respective box or location on the heart. Note that diodes near the edge of the heart and the array tended to have more movement artifacts compared with diodes near the centre of the array.

Optical apparatus, computer interface

Bipolar Ag+–AgCl electrodes (250 μm diameter Teflon-coated silver wire) were placed on the apical and basal surfaces of the ventricle and used to stimulate or record electrograms in parallel with the 256 optical APs continuously during the time course of an experiment.

The optical apparatus and computer interface have been previously described (Salama et al. 1987; Kanai & Salama, 1995; Baker et al. 2000; Choi & Salama, 2000). Briefly, light from a 100 W tungsten–halogen lamp was collimated, passed through a 530 ± 20 nm interference filter, and focused on the surface of the heart by epi-illumination using a 570 nm dichroic mirror and a camera lens (Nikon, 50 mm 1 : 1.2). Fluorescence from the heart was passed through a cut-off filter (> 610 nm) and focused on a 12 × 12 element photodiode array with a magnification of 4.5 such that each diode detected light from a 312 μm × 312 μm region of ventricle with a depth of 70 μm. The photocurrent from each diode was passed through a current-to-voltage converter (50 MΩ feedback resistor), AC or DC coupled, amplified (× 1, 50, 200 or 1000), digitized at 2000 or 4000 frames s−1 at a 12-bit resolution (DAP 3200e/214 Microstar Laboratories), and stored in computer memory.

APD75 was determined from measurements of the time point of maximum upstroke velocity (dF/dt)max to the time point at which the downstroke recovered to 75% back to baseline. APs with signal-to-noise ratios of < 10 or with excessive movement artifact (i.e. AP downstroke does not recover smoothly and within 10% of baseline voltage) were not included in the analysis. Isochronal maps of activation and repolarization, local conduction velocity maps, and conduction velocities were generated from local activation and repolarization time points, as previously described. Delaunay's triangulation algorithm was used to compensate for rejected data points. Fast Fourier transforms (FFT) at each site were used to test for spatial organization in VT, as previously described (Choi et al. 2002).

Restitution kinetics of AP amplitudes

The short duration and triangulation of the AP downstroke in the mouse make it difficult to measure the restitution kinetics of APDs. Instead, we analysed the restitution kinetics of the AP amplitude (APA) which depends on the restitution of inward (INa and ICa) as well as outward K+ repolarizing currents (Baker et al. 2000). In mouse, as in hearts from larger mammalian species, the restitution kinetics of APA (APA versus the diastolic interval, DI) was shown to be an excellent surrogate measurement for the more standard restitution of APD (Gettes & Reuter, 1974; Baker et al. 2000). Hearts were paced at the apex at a basic cycle length (CL) S1–S1 of 200 ms (10 beats) and single premature stimulus, S2 was delivered at decreasing coupling intervals S1–S2 at either the base or apex. The S1–S2 interval was gradually reduced in 2 ms steps for long coupling intervals and 1 ms decrements for short S1–S2 intervals or during the steep phase of the restitution kinetics curve. S1–S2 was reduced until S2 failed to capture an AP. The refractory period at that site was defined as the longest S1–S2 interval which failed to elicit a propagating AP.

Voltage-clamp studies

Myocytes were isolated from base and the apex of the left ventricle of 2–3 month, 25–30 g mice of the FVs strain using type 2 collagenase as previously described (Petkova-Kirova et al. 2006). The whole-cell configuration was used to record regional differences in outward K+ currents. Patch electrodes (1.5–3 MΩ) of borosilicate glass (WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA) were polished and filled with (mm): 135 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 5 glucose, 3 MgATP, at pH 7.2. Currents were measured (EPC9, HEKA Electronik, Lambrecht, Germany) using PULSE software (v8.50) at 22–24°C, from cells superfused at 0.5–1.5 ml min−1 (mm: 136 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 5 CoCl2, 10 Hepes and 10 glucose, pH 7.35). Tetrodotoxin (20 μm) was added to block INa. Cell capacitance and series resistance (Rs) were measured and compensated. Outward K+ currents were elicited by 4.5 s voltage steps from a holding potential of −90 mV to test potentials from −40 to +50 mV in 10 mV increments at 15 s intervals. Voltage steps were preceded by a short prepulse (20 ms, at −20 mV) to eliminate residual Na+ current. 4-AP (50 μm) and TEA (25 mm) were used to block over 50% of IKslow1, IKslow2 and Iss and highlight the changes in Ito (Xu et al. 1999a). The amplitudes (in pA pF−1) of the K+ currents Ito,f,IKslow and Iss were determined by fitting to the overall K+ current traces to the double exponential function I(t) = A0 + A1exp(−t/τ1) +A2exp(−t/τ2) where A0, A1 and A2 represent the amplitudes of Iss, Ito,f and IKslow, respectively, and τ1 and τ2 the time constants of inactivation of Ito,f and IK,slow. The data fit was done using PulseFit software (v8.0; HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Values are given as mean ± s.d. except as indicated. Student's t tests were performed on APD and velocities to compare control and transgenic mice. Results were considered significant when P < 0.05. Refractory periods and APDs from the same heart were averaged from eight diodes at the base and apex and compared with the use of a paired Student's t test to determine gradients of repolarization and refractoriness. Grouped tests were used to determine the statistical significance of gradients of refractoriness and APD between control and transgenic mice.

Results

Action potential durations and restitution kinetics

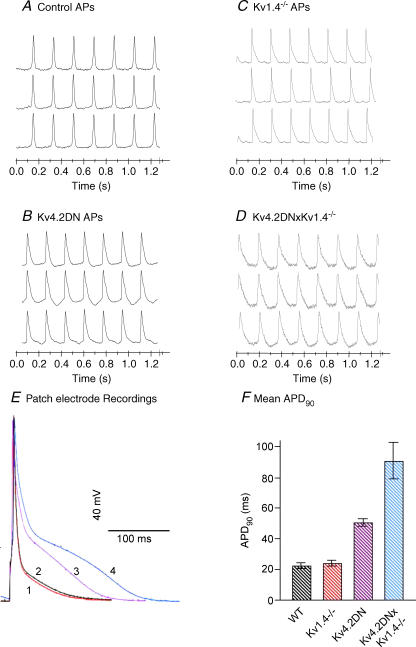

Figure 1 shows the chamber and a map of simultaneously recorded APs. The map consists of a symbolic map of the array with an AP recorded by each photodiode displayed in its respective location. Figure 2 demonstrates optical APs from three diodes midway between the apex and base from control (A), Kv4.2DN (B), Kv1.4−/− (C) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (D) mice. Note the AP prolongation in all transgenic mice compared with control mice. Figure 2E illustrates the superposition of APs measured with patch electrodes from myocytes isolated from control (1), Kv1.4−/− (2), Kv4.2DN (3) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (4) mice. Figure 2F shows the summary data by comparing the mean APD90 ± s.e.m. (n = 6–8 myocytes in each group). Note that the AP recorded with a patch electrode from a Kv1.4 null mouse was similar to the wild type because they were recorded from the apex of the left ventricles where Kv1.4 is not expressed. In contrast, the optical APs were recorded from the anterior surface of the heart where the septum merges with the right and left epicardium and are prolonged in Kv1.4−/− compared with wild type mice. Note that APs recorded optically and with patch electrodes had different time courses because they are measured under different conditions (cycle length, temperature, location) and because optical recordings were made in coupled myocytes under an electrical load. Nevertheless, both measurements are in agreement regarding the relative changes in APDs. Figure 3A shows a histogram of optically recorded APD75 values from control and transgenic mice. At a cycle length (CL) of 200 ms, APD75 was longer in the Kv4.2DN (28.0 ± 2.5 ms, n = 6 hearts, P < 0.01) and Kv1.4−/− (28.4 ± 0.4 ms, n = 5, P < 0.01) than control (20.3 ± 1.0 ms, n = 5) hearts, and was even more prolonged in the Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (34.3 ± 2.6 ms, n = 6, P < 0.01) hearts. Similar results were found in isolated ventricular myocytes from Kv4.2DN and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− mice, where APDs were prolonged in transgenic mice compared with littermate controls (Guo et al. 2000). In Kv1.4−/− mice, myocytes isolated from the ventricular free wall lack Ito,s or APD prolongation (London et al. 1998b; Guo et al. 2000). The APD prolongation seen in Kv1.4−/− with optical mapping represents segments of the septum that merges with the right and left epicardium and express Ito,s.

Figure 2. Optical APs from mice with LQT.

Examples of optical action potentials recorded from 3 diodes obtained from control (A), Kv4.2DN (B), Kv1.4−/− (C) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (D) mice. APDs can be compared because all the hearts were paced at 200 ms CL. Note the progression of APD prolongation in Kv4.2DN (lacks Ito,f) and Kv1.4−/− (lacks Ito,s) and even longer in the Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (lacks Ito,f and Ito,s) compared with controls. E shows representative APs recorded with a patch electrode from myocytes isolated from wild type (WT) control (1), Kv1.4−/− (2), Kv4.2DN (3) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (3). APs were recorded following supra-threshold depolarizing currents (3 ms duration) at 10 Hz and 35°C. F, summary data of mean APD at 90% repolarization (APD90) ±s.e.m., measured in wild type (WT), Kv1.4−/−, Kv4.2DN and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− myocytes (n = 6–8 in each group). All myocytes were isolated from the apex of the left ventricles which accounts for the normal looking AP recorded from Kv1.4−/− myocytes.

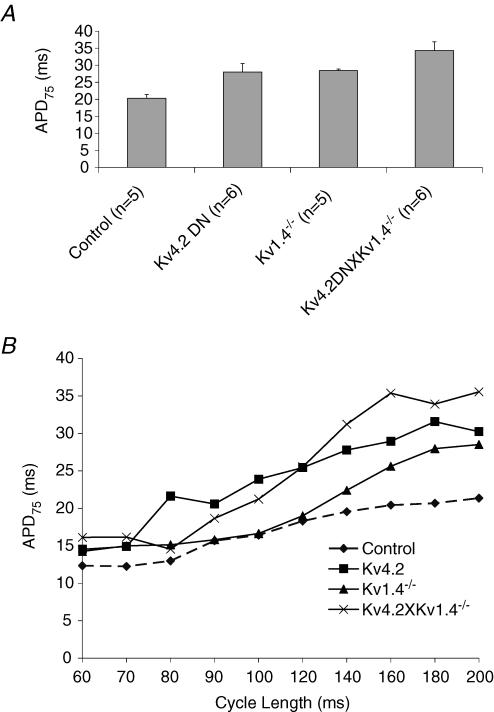

Figure 3. APD versus cycle length.

A, a histogram displaying the mean APD75 for control (n = 5), Kv4.2DN (n = 6), Kv1.4−/− (n = 5) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (n = 6). The 3 transgenic lines of mice had statistically longer APDs compared with controls (APD75 = 20.3 ± 1.0 ms in control, 28.0 ± 2.5 ms in Kv4.2DN, P < 0.01, 28.4 ± 0.4 ms in Kv1.4−/−, P < 0.01, and 34.3 ± 2.6 ms in Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/−, P < 0.01). B, APD75versus CL for transgenic and control hearts. Each data point represented the mean ± s.d. of APDs measured at 8 diodes at the centre of the array. The plots demonstrate an enhanced APD adaptation to CL in transgenic hearts with Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− having statistically significant steepest slope (m = 0.17); Kv4.2DN (m = 0.12) and Kv1.4−/− (m = 0.11) also had steeper slopes compared with control hearts (m = 0.07, P < 0.05).

Figure 3B compares the changes in APD as a function of cycle length for the control, Kv4.2DN, Kv1.4−/−, and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− mice. The slopes of APD versus CL were significantly greater for Kv4.2DN (m = 0.11), Kv1.4−/− (m = 0.11) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (m = 0.17) compared with control mice (m = 0.07). All three mouse models of long QT had the expected APD prolongation compared with controls since the genetic manipulations reduced K+ currents involved in cardiac repolarization.

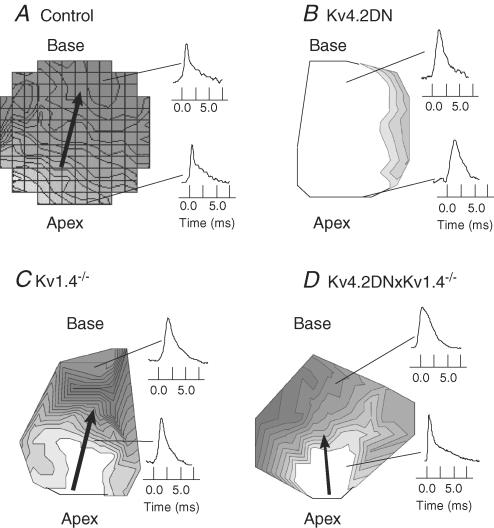

Figure 4 illustrates maps of APDs recorded from the anterior surfaces of hearts from the three mouse lines with long QT compared with control. In control mice, APDs were shorter at the apex and progressively longer towards the base with a dispersion of APDs of 80 ± 2.3 ms (n = 5) (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, maps of APDs from Kv4.2DN mice were highly homogeneous with no significant apex–base heterogeneities (1.5 ± 2.3 ms, n = 4) (Fig. 4B). In contrast, APD maps from Kv1.4−/− and Kv4.2×Kv1.4−/− had a tendency towards enhanced dispersions of APD from apex to base compared with controls, with gradients of 16.0 ± 3.3 ms (n = 4) and 14.0 ± 2.8 ms (n = 4), respectively (Fig. 4C and D). The high density of isochrones in the centre of the APD map for Kv1.4−/− hearts indicated that gradients of APDs occurred primarily on the septum as it merged with the epicardium of the right and left ventricles (Fig. 4C). This enhanced dispersion of APDs in the centre of the anterior surface of the heart is consistent with the restricted expression of Kv1.4 on the septum (Guo et al. 1999a).

Figure 4. Maps of APDs.

APD maps were recorded from the anterior surface of the heart at 200 ms CL and 37°C; maps are orientated with the base on top, apex at the bottom, left ventricle on the right side, and right ventricle on the left side; the interventricular septum merges with the epicardium and appears at the centre of the maps along the vertical axis separating right from left ventricles. APD maps are shown for wild type (WT) (A), Kv4.2DN (B), Kv1.4−/− (C) and Kv4.2×Kv1.4−/− (D). In each map, representative AP recordings from the apex and base are shown. APD distributions are shown as isochronal lines 1 ms apart for A, B and C and 2 ms apart in D. Gradients are from short (bright) to long (dark) APDs; summary data of APD75 values are shown in Table 1.

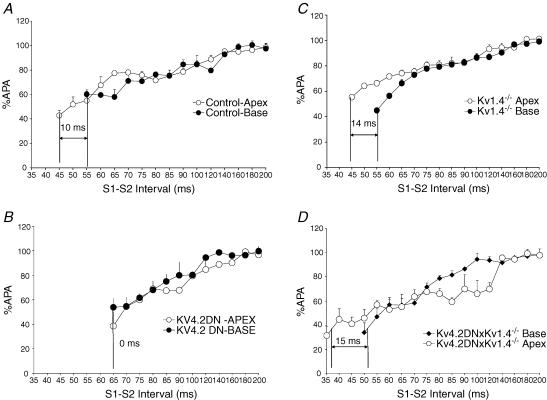

Figure 5 plots the restitution kinetics of APA measured from the apex and base of control (A), Kv4.2DN (B), Kv1.4−/− (C) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (D), hearts. For control mice, the refractory period was longer at the base than the apex and the dispersion of refractoriness, ΔDR, was measured from the difference in refractory periods between the apex and the base of the heart (Fig. 5A; ΔDR = 10 ms: 55.5 ± 11 ms, base; 45 ± 9 ms, apex, n = 5). In Kv4.2DN hearts (Fig. 5B), the slope of the APA restitution curve was similar to control mice but the apex–base dispersion of refractoriness was zero, with identical refractory periods at the base and apex (ΔDR = 0.3 ± 0.5 ms, n = 6, P < 0.05). In contrast, Kv1.4−/− (14.2 ± 2.0 ms, n = 5, P < 0.05) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (15.0 ± 3, n = 5, P < 0.05) mouse hearts had similar restitution slopes but significantly longer ΔDR compared with controls (Fig. 5C and D). Table 1 summarizes the refractory periods from the base and apex of mice with long APDs and their littermate controls. For all four mouse lines, refractory periods were longer than APD75, consistent with a post-repolarization refractory period of 10–12 ms, as previously described (Baker et al. 2000).

Figure 5. Restitution kinetics of APA.

Restitution kinetics of APA was measured by pacing the ventricle at a basic CL (S1–S1 = 200 ms for 10 beats, followed by a premature pulse (S2) applied at a varying (S1–S2) intervals. A, control; B, Kv4.2DN; C, Kv1.4−/−; and D, Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− hearts. Differences in refractory periods (RPs) between apex and base for controls, ΔDR, was measured for controls (10 ± 2 ms, n = 5 hearts), Kv4.2DN (0.3 ± 0.5 ms, n = 6), Kv1.4−/− (14.2 ± 2.0 ms, n = 5) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (15.0 ± 3 ms, n = 5). Although the slopes of the restitution kinetics curves were not significantly different, ΔDR was markedly different among the 3 transgenic lines and control mice.

Table 1.

Apex–base differences in APD75, refractory periods, spatial dispersions and VT vulnerability

| WT (n = 5) | Kv4.2DN (n = 6) | Kv1.4−/− (n = 5) | Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (n = 5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APD75 base | 25 ± 2.5 | 26.68 ± 1.7 | 36 ± 3.9 | 44.8 ± 5.7 |

| APD75 apex | 17 ± 2.2* | 29.7 ± 2.0 | 20 ± 2.7* | 30.8 ± 6.6* |

| ΔAPD75 | 8 ± 2.3 | 1.5 ± 2.3** | 16 ± 3.3** | 14 ± 2.8** |

| RF base | 55.6 ± 15 | 54.2 ± 12 | 51.7 ± 3 | 48 ± 6 |

| RF apex | 45.0 ± 9* | 53.9 ± 12 | 37.5 ± 3* | 39.8 ± 7* |

| ΔRP | 10 ± 2 | 0.3 ± 0.5** | 14 ± 2** | 15 ± 3** |

| Propensity to VT (extra pulse at base) | 0/5 | 0/6 | 1/5 | 4/5 |

| Propensity to VT (extra pulse at apex) | 0/5 | 0/6 | 4/5 | 4/5 |

| VT burst pacing | 4/5 | 3/6 | 4/5 | 5/5 |

| Duration | 2–3 min | 30 s | 4 min | ∼30 min |

APD75s were recorded from the base and apex of Langendorff perfused hearts at 200 ms cycle length, averaged for each heart and for number of hearts (n). Refractory periods (RF) were measured using programmed stimulation at sites on the base and apex of the heart and the apex–base dispersion of refractoriness was averaged for n for wild type (WT) control and transgenic mouse hearts.

P < 0.05 between base and apex for APD75 and RPs.

P < 0.05 ΔAPD75 and ΔRP between control and transgenic hearts.

Arrhythmia vulnerability in mouse models of LQT

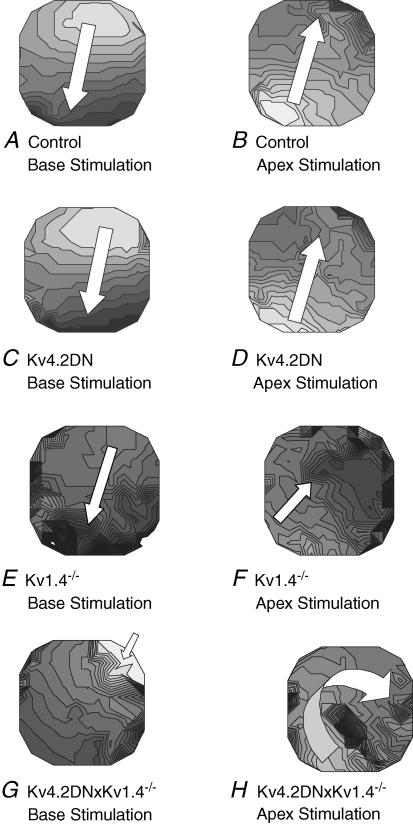

The vulnerability to arrhythmias was tested by applying a single premature pulse near the refractory period with the electrode located at the base or the apex of the left ventricle. Figure 6 shows the activation maps of the premature stimulus when applied at the base (left panels) or when applied at the apex (right panels) for control (panels A and B), Kv4.2DN (C and D), Kv1.4−/− (E and F), and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (G and H) hearts. The control (n = 0/5) and Kv4.2DN (n = 0/6) hearts could not be induced to VT with a single premature pulse located at either the apex or the base (Fig. 6A–D). The Kv1.4−/− hearts displayed inducible VT from apex stimulation (n = 4/5) but not from base stimulation (n = 1/5). (Fig. 6E and F) As previously reported (Guo et al. 1999b), Kv1.4 is primarily expressed in the left ventricular septum which would be located along the vertical axis at the centre of the anterior surface of the heart (i.e. vertical axis in Fig. 6E and F). In Kv1.4−/− mice, premature impulses applied at the base or apex tended to capture, propagate and encounter regions of slow conduction along the centre of the anterior surface indicative of prolonged refractory periods (Fig. 6E and F). Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− hearts had the largest dispersion of refractoriness and the most arrhythmogenic substrate; a single premature impulse induced VT when applied either at the base (n = 4/5) or apex (n = 4/5). The premature impulse from the base captured, encountered a functional line of block, and elicited VT (Fig. 6G). Similarly, APs triggered by a premature impulse at the apex encountered a line of refractory myocardium and then spread clockwise around the block to elicit VT (Fig. 6H).

Figure 6. Activation maps of a premature impulse.

Programmed stimulation was applied to evaluate the arrhythmia vulnerability of control and transgenic mice. Hearts were paced at a basic cycle length (S1–S1 = 200 ms CL) for 10 beats then a premature stimulus was applied near the apex or the base of the left ventricle with a coupling interval close to the local RP. Activation maps of the premature impulse are shown to assess the propensity to arrhythmias. In these examples, the coupling interval was 56 ms for control (A), 60 ms for Kv4.2DN (C), 52 ms for Kv1.4 −/− (E), and 55 ms for Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− hearts (G). No VTs were induced by a premature impulse applied at the base or apex for control (A and B) or Kv4.2DN hearts (C and D). However, VTs occurred by applying the premature pulse at the apex (but not the base) of Kv1.4−/− (F) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (H) mice. In the latter cases the premature pulse encountered a functional line of block (depicted by a high density of isochrones in F and H), propagated around the region of high refractory periods to initiate the first cycle of VT. Isochronal lines are 1 ms apart.

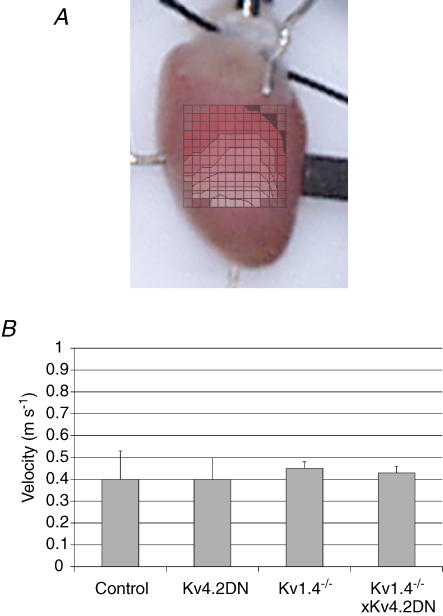

We compared the activation patterns and conduction velocities of these mice to evaluate conduction slowing as a potential contribution to arrhythmia vulnerability. Figure 7A illustrates a typical isochronal map of activation (4 mm × 4 mm) recorded from a control heart and overlaid on a digital picture of the heart to visualize the mapped region. Isochronal maps of activation (not shown) and conduction velocity histograms (Fig. 7B) showed that there were no statistical differences in conduction velocities (in m s−1) of control (0.4 ± 0.10, n = 5), Kv4.2DN (0.4 ± 0.13, n = 6), Kv1.4−/− (0.45 ± 0.03, n = 5) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (0.43 ± 0.03, n = 5) hearts.

Figure 7. Activation sequence and conduction velocities.

A, isochronal map of activation (4 mm × 4 mm) from a control heart was superimposed on a picture of the heart to visualize the activation sequence. Isochronal maps from all 3 transgenic mouse lines were identical. B, histogram of conduction velocities. Conduction velocities were calculated for each heart (see Methods) then averaged to compare control and transgenic mice. No statistically significant differences were found in conduction velocities between control (0.4 ± 0.10 m s−1, n = 5), Kv4.2DN (0.4 ± 0.13 m s−1, n = 6), Kv1.4−/− (0.45 ± 0.03 m s−1, n = 5) and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (0.43 ± 0.03 m s−1, n = 5) mice.

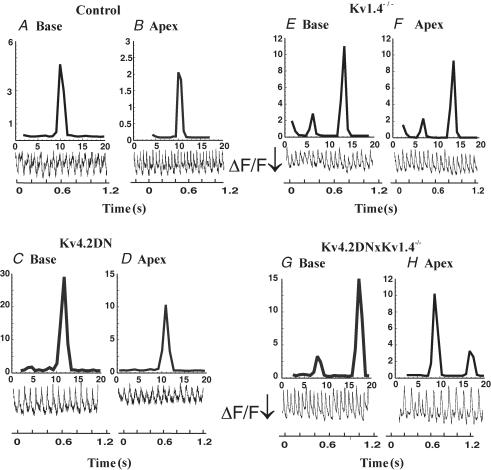

The propensity to reentrant VT in control and transgenic mice was also tested by burst stimulation where the heart was paced at a basic cycle length (S1–S1 = 200 ms) followed by a burst of 30 beats at 20–30 ms cycle length. Burst pacing was applied near the apex of the left ventricle of control and transgenic mice to test for their vulnerability to arrhythmias (Fig. 8). Fast Fourier transform (FFT) from various sites on the heart was used to analyse the spatial organization and nature of VT. Control hearts consistently had arrhythmias (n = 4/5) that lasted 2–3 min and FFT spectra recorded from various sites recorded a single dominant frequency (12.2 ± 0.7 Hz; n = 4) (Fig. 8A and B). It was more difficult to elicit arrhythmias in Kv4.2DN hearts (n = 3/6) and in those that were inducible, the VT was brief (30 s) and had a single frequency throughout the heart (12.9 ± 0.72 Hz, n = 3) (Fig. 7C and D). In Kv1.4−/− mice, burst pacing elicited VTs with alternating frequencies at 14.1 ± 1.5 and 7.1 ± 0.9 Hz (n = 4/5) that lasted ∼4 min (Fig. 8E and F). In contrast, Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− had long-lasting VTs (n = 5/5) that lasted ∼30 min with alternating frequencies of 17.6 ± 1.8 and 8.7 ± 0.7 Hz (Fig. 8G and H). These data imply that Kv4.2DN mice with uniform refractory periods along the epicardium were most resistant to arrhythmias than control mice. Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− mice were the most vulnerable to arrhythmias, with long-lasting, stable VTs that could be elicited by either a single premature pulse or by burst pacing.

Figure 8. Arrhythmias elicited by burst pacing.

Burst pacing was applied as a more stringent test to elicit arrhythmias then the nature and duration of VTs was monitored. For each mouse line, we illustrate the arrhythmia by showing voltage oscillations (Vm) and their fast Fourier transform (FFT) to analyse the dominant frequencies of VT. In each panel, Vm and FFT spectra are shown from the base (left) and the apex (right) for control (A and B), Kv4.2DN (C and D), Kv1.4−/− (E and F), and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (G and H) mice. Control (A and B) and Kv4.2DN (D and E) mice had short lived VT with a single dominant frequency whereas Kv1.4−/− and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− had long lasting VT alternans (E–H). FFT spectra are in arbitrary units, ×109 for A–F and ×1010 for G and H. Examples of optical recordings of membrane potential (Vm) during VT are shown for the base and apex of each mouse line and the fractional fluorescence change, ΔF/F increased (arrow = 6% fluorescence increase) for more negative Vm.

Apex–base distribution of Ito,f

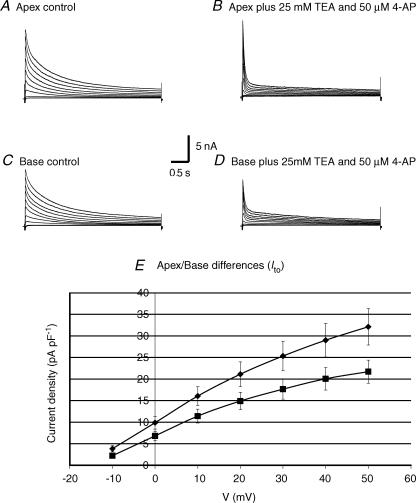

As previously reported for adult FVB mouse hearts, repolarization spreads from the apex to the base across the left and right ventricular epicardium (Baker et al. 2000). Consistent with these findings, Brunet et al. reported that in the C57Black6 mouse strain, Ito,f densities were significantly higher in cells from the apex than the base and Ito,s was detected in cells from the septum but not cells from the right or left ventricles (Brunet et al. 2004). We compared outward K+ current densities in control FVB mice, and found that Ito,f density was significantly higher in cells from the apex (35% at +50 mV and 30% at +20 mV) than in cells from the base (Fig. 9). These findings and the absence of a gradient of refractoriness in the Kv4.2DN mice provide compelling evidence that the apex–base dispersions of repolarization and refractoriness are primarily due to the regional distribution of Ito,f.

Figure 9. Regional distribution of Ito,f.

Cells were isolated from the apex (n = 14, 6 hearts) and base (n = 14, 7 hearts) of FVB mice. A, K+ currents from the apex and base are shown at baseline (left) and after blockade of IK,slow with 50 μm 4-AP and 25 mm TEA to accentuate Ito,f. B, I–V curves showing the amplitude of Ito,f in cells from the apex and base. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. At +20 mV, Ito,f was 20.3 ± 2.9 pA pF−1 at the apex and 15.2 ± 1.9 pA pF−1 at the base. Differences of Ito,f between apex and base were statistically significant for −10 to +50 mV with P < 0.05.

Discussion

The main findings of this studay are that dispersion of repolarization and refractoriness are important determinants of arrhythmia phenotype and that the elimination of specific currents by genetic manipulation of Ito,f, Ito,s and IK,slow cause alterations in dispersion of repolarization that can enhance or reduce the vulnerability to arrhythmia. In Kv4.2DN mice, the homogeneity of repolarization from apex to base produced a remarkable anti-arrhythmic phenotype that was highly protective compared with wild type mice. Conversely, Kv1.4−/− and Kv4.2×Kv1.4−/− mice had higher dispersion of repolarization and a higher propensity to long lived VTs. Of note, APD and QT interval were markedly prolonged in Kv4.2DN and Kv4.2×Kv1.4−/− mice, but only mildly prolonged in Kv1.4−/− mice. These mouse models reveal that APD prolongation alone is not a reliable determinant of arrhythmia phenotype and other factors such as regional distribution of currents and refractory periods are critical to assess arrhythmia vulnerability.

Action potential durations and cycle length dependence

APD75 measured in control mice were in excellent agreement with previous measurements in both isolated cells and optical mapping studies (London et al. 1998a; Zhou et al. 1998; Baker et al. 2000). Consistent with single-cell voltage-clamp experiments (Guo et al. 2000), the systematic elimination of K+ currents involved in the repolarization of the AP produced the expected AP and QT prolongation. As shown in Figs 2 and 3, APDs were significantly longer in molecularly engineered KV4.2×Kv1.4−/− mice lacking both Ito,f and Ito,s than in Kv4.2DN mice lacking Ito,f, or Kv1.4−/− mice lacking Ito,s. The transient outward currents play an important role in shaping the early phase of the cardiac action potential such that alterations of Ito influenced the balance of currents during the plateau phase and prolonged APDs, refractory periods and QT intervals.

Murine hearts have short APDs (APD75= 20 ms) that tend to vary weakly as a function of rate or basic cycle length (CL). In the mouse lines studied here, Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− hearts had the longest APDs and the steepest APD versus CL relationship. In mice lacking both Ito,f and Ito,s, repolarization relied more on the inactivation of the L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ current, ICa-L, IK,slow and the inward rectifying K+ current, IK1. These remaining currents must exhibit a greater rate dependence that increases the steepness of the APD versus CL relationship.

Dispersion of repolarization and distribution of Ito,f and Ito,s

Gradients of refractoriness between apex and base most likely reflect the differential expression of ion channels. In another mouse model prone to arrhythmias (Kv1.1DN mice), loss of the rapidly activating, slowly inactivating 4-AP-sensitive current IK,slow1 and the slow component of the transient outward current Ito,s led to APD and QT prolongation associated with enhanced dispersion of repolarization and refractoriness (London et al. 1998a; Baker et al. 2000). Kv1.1DN mice were generated on an FVB background, which had significantly higher levels of Ito,f and shorter APDs at the apex than the base of the left ventricle (Fig. 8). The loss of IK,slow1, a major repolarizing current that is spatially uniform (Brunet et al. 2004), led to exacerbation of the gradients between apex and base.

In Kv4.2DN mice, the down-regulation of Ito,f resulted in APD prolongation (Guo et al. 2000) and the disappearance of the normal dispersion of refractoriness (Fig. 4B). The spatially uniform refractory periods can be attributed to the loss of Ito,f. In contrast, Kv1.4−/− and Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− mice had greater apex–base gradients of refractoriness than wild type mice, suggesting that ion channels other than Ito,f and Ito,s may contribute to the DR. This is consistent with recent reports that blocking Ito can lead to significant changes in ICa,L (Wang et al. 2006).

Conduction velocities

Conduction velocities are in excellent agreement with those obtained with electrodes (Θ = 0.4 ± 0.10 m s−1) (Thomas et al. 1998), optical mapping with a photodiode array (Θmax = 0.85 ± 0.13 m s−1 and Θmin = 0.33 ± 0.17 m s−1) (Baker et al. 2000) and with charge coupled devises (CCD) (Θ = 0.4 ± 0.03 m s−1) (Morley et al. 1999; Vaidya et al. 1999; Gutstein et al. 2001). No differences were detected between control and transgenic mice implying that genetic manipulations of K+ current did not alter conduction velocity and played no significant role in promoting the arrhythmia phenotype in these models.

Mechanisms underlying arrhythmias

The prolongation of APDs and refractory periods (RPs) had been proposed as a possible strategy to protect the heart from triggered activity and arrhythmias by reducing excitability of the heart for longer periods (Hondeghem, 1992). However, drugs that prolonged APD and QT interval are now known to be highly arrhythmogenic as they tend to elicit early afterdepolarizations (EADs) that progress to a form of polymorphic ventricular arrhythmias called Torsade de Pointes (Roden, 1993). The mechanisms whereby QT prolongation leads to arrhythmias remain unclear, although the initiation of EADs and an enhanced dispersion of repolarization have been proposed as underlying mechanisms (Surawicz, 1987; Choi et al. 2002). Single cells isolated from Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− mice had prominent EADs at 1–3 Hz and 25°C (Guo et al. 2000). Conditions favourable to spontaneous EADs were not practical in the Langendorff perfused hearts studied here, where low temperature arrested electrical activity and slow pacing rates could not be reliably maintained without interference from spontaneous activity. Instead, we applied programmed stimulation (S1–S2 stimulation) and found that a single premature pulse applied close to the local refractory period elicited reentrant VT in Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− (n = 4/5) but not Kv4.2DN hearts (n = 0/6) due to enhanced dispersion of repolarization and refractoriness.

Burst pacing was also used as a more robust arrhythmogenic test and was effective in eliciting arrhythmias even in control hearts. The same protocol elicited only brief electrical instabilities in a fraction of Kv4.2DN hearts. The remarkably uniform refractory periods of Kv4.2DN hearts (ΔDR = 0.3 ± 0.5 ms; n = 6) compared with control hearts (10.0 ± 2 ms, n = 5) produced a highly anti-arrhythmic substrate.

In Kv1.4−/− mice, VT was elicited by an extra pulse if applied at the apex but not if applied at the base of the heart. Kv1.4−/− mice lack Ito,s which is expressed only in the septum. Loss of this current may prolong the refractory period in the septum. A premature stimulus at the apex may lead to a functional line of block and reentry due to prolonged refractory periods in the septum, while premature stimuli at the base do not because the refractory period is longer. These experimental findings in mouse hearts are consistent with simulations that showed that APD heterogeneities and DR provide a substrate for unidirectional block and reentry (Viswanathan & Rudy, 2000).

In contrast, Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− mice had a high dispersion of refractoriness and were readily induced into VT alternans with two dominant frequencies by either burst pacing or a single premature impulse. The Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− transgenic mice offer an experimental model of stable VT alternans. The interplay of long APD and large gradients of refractoriness adjusted the wavelength of the reentry circuit (APD × conduction velocity) to match the reentry pathway to the approximate dimensions of the perimeter of the heart. Each rapidly propagating reentry wavefront catches up to its tail and encounters relatively refractory tissue resulting in a slowing down of conduction. The slow reentrant wavefront propagates through a cycle and then encounters excitable tissue to initiate the fast reentrant beat, perpetuating VT alternans. Such VTs can be stable and long lasting in Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− mice because there are no anatomical obstacles or metabolic injury.

Hence, heterogeneities of repolarizing K+ currents underlie gradients of APDs and refractory periods which influence VT dynamics. A similar VT alternans was reported in the Kv1.1DN transgenic mouse lacking the IK,slow1 and Ito,s currents (Baker et al. 2000). The differences in cycle length between the long and short cycles were greater in Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− than Kv1.1DN mice, suggesting that the magnitude of refractory periods and DR may influence the dynamics of the arrhythmia.

Kv4.2DN mouse hearts have an anti-arrhythmic substrate. Crossing the Kv4.2DN mouse with the Kv1.1DN mouse yielded Kv1.1DN×Kv4.2DN mice with significant APD and QT prolongation and an attenuation of the spontaneous and inducible arrhythmias (Brunner et al. 2001).

A different mouse model that lacked Ito,f was developed by a targeted deletion of KChIP2, an auxiliary subunit for Kv4.2 and 4.3 (Kuo et al. 2001). KChIP2−/− mice had a complete absence of Ito, prolonged APDs and sustained polymorphic VT induced by programmed stimulation (Kuo et al. 2001). KChIP2 may play a critical role in trafficking of Kv4.2 and/or Kv4.3 from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cell membrane and may modulate the gating and kinetics of the channel. The weak arrhythmia phenotype of KChIP2−/− mice makes it difficult to identify the specific mechanism from in situ electrophysiological studies. Kuo et al. (2001) proposed that the elimination of Ito resulted in a uniform DR between endocardium and epicardium that promoted polymorphic VT. In the absence of DR measurements on KChIP2−/− mice, it is difficult to explain how uniform repolarization (transmural or apex–base) can enhance the vulnerability to arrhythmias and why the results differ from the current study.

Limitations

Motion artifacts may limit the validity and interpretation of APD and repolarization maps in the mouse. We did not use agents that inhibit contraction such as diacetyl monoxime and cytochalasin-D because they prolong APDs and act as anti-arrhythmic agents (Baker et al. 2000, 2004). Instead, we relied on a chamber to mechanically abate large displacement of the heart in and out of the focal plane of the optical apparatus. We would argue that APD data shown in this study are accurate and valid based on the quality of the signals as in Figs 1 and 2 and on the agreement between APDs measured optically and with intracellular microelectrodes. Besides overt differences in the size of human and mouse hearts, the two species rely on significantly different sets of K+ channels to drive cardiac repolarization. Here, genetic manipulations of mouse genes were used to produce a loss of function of K+ currents that are involved in repolarization of mouse APs (Ito,f and Ito,s) rather than K+ currents important to repolarization of the human AP (IKr, and IKs). The mouse models of LQT showed us that the loss of function of a K+ current affects not only the shape of the AP but also DR and demonstrate that the arrhythmia phenotype depends on DR. Even in mouse models of long QT that produce 2-fold increases in APD from 23 to 46 ms, such long APDs still remain far shorter than human APDs (200–300 ms). Still, mouse models of long QT exhibit alterations of APD that parallel those found in congenital and acquired forms of human long QT syndrome, such as EADs, enhanced DR and an enhanced arrhythmia phenotype. Nevertheless, the structural and electrophysiological differences between mouse and man require us to interpret findings in molecularly engineered mice with caution.

Conclusions

The capacity to selectively mutate, over-express or delete genes in the mouse remains a powerful tool to investigate congenital heart diseases, and optical mapping provides a uniquely valuable tool to investigate arrhythmic phenotypes. This study focused on lines of mice with loss of function of specific K+ currents, the regional distributions of these currents in wild type mice, and how the severity of the dispersion of repolarization is linked to the propensity to arrhythmias. Interestingly, although both models have APD and QT prolongation, Kv4.2DN×Kv1.4−/− mice have increased DR and stable VT alternans whereas Kv4.2DN mice have uniform repolarization and no arrhythmias. The findings highlight the importance of spatial heterogeneities of ion channel expression and dispersion of repolarization and refractoriness as major determinants of arrhythmia vulnerability.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) with RO1 grants HL 59614, HL 57929 and HL 70722 to G.S.; HL034161 and HL066388 to J.M.N.; and HL-66096 and an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award to B.L.; a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Western Pennsylvania Affiliate of the American Heart Association to L.C.B. and an AHA Grant-in-Aid to B.-R.C. The authors thank William Hughes of our departmental machine shop for the construction of optical components and the mouse chamber and Greg J. Szekeres of our departmental electronic shop for building the computer interface.

References

- Ackerman MJ. The long QT syndrome: ion channel diseases of the heart. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:250–269. doi: 10.4065/73.3.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzelevitch C, Sicouri S, Litovsky SH, Lukas A, Krishnan SC, Di Diego JM, Gintant GA, Liu DW. Heterogeneity within the ventricular wall. Electrophysiology and pharmacology of epicardial, endocardial, and M cells. Circ Res. 1991;69:1427–1449. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.6.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzelevitch C, Sicouri S, Lukas A, Nesterenko V, Liu D-W, Di Diego JM. Regional differences in the ventricular cells: physical implications. In: Zipes DP, Jalife J, editors. Cardiac Electrophysiology: from Cell to Bedside. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1994. pp. 228–245. [Google Scholar]

- Baker LC, London B, Choi BR, Koren G, Salama G. Enhanced dispersion of repolarization and refractoriness in transgenic mouse hearts promotes reentrant ventricular tachycardia. Circ Res. 2000;86:396–407. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.4.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LC, Wolk R, Choi BR, Watkins S, Plan P, Shah A, Salama G. Effects of mechanical uncouplers, diacetyl monoxime, and cytochalasin-D on the electrophysiology of perfused mouse hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1771–H1779. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00234.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DM, Nerbonne JM. Myocardial potassium channels: electrophysiological and molecular diversity. Annu Rev Physiol. 1996;58:363–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.58.030196.002051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry DM, Xu H, Schuessler RB, Nerbonne JM. Functional knockout of the transient outward current, long-QT syndrome, and cardiac remodeling in mice expressing a dominant-negative Kv4 alpha subunit. Circ Res. 1998;83:560–567. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.5.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouillette J, Rivard K, Lizotte E, Fiset C. Sex and strain differences in adult mouse cardiac repolarization: importance of androgens. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:148–157. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet S, Aimond F, Li H, Guo W, Eldstrom J, Fedida D, Yamada KA, Nerbonne JM. Heterogeneous expression of repolarizing, voltage-gated K+ currents in adult mouse ventricles. J Physiol. 2004;559:103–120. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.063347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner M, Guo W, Mitchell GF, Buckett PD, Nerbonne JM, Koren G. Characterization of mice with a combined suppression of Ito and IK,slow. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H1201–H1209. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.3.H1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BR, Nho W, Liu T, Salama G. Life span of ventricular fibrillation frequencies. Circ Res. 2002;91:339–345. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000031801.84308.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BR, Salama G. Simultaneous maps of optical action potentials and calcium transients in guinea-pig hearts: mechanisms underlying concordant alternans. J Physiol. 2000;529:171–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessertenne F. Ventricular tachycardia with 2 variable opposing foci (in French) Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1966;59:263–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drici MD, Baker L, Plan P, Barhanin J, Romey G, Salama G. Mice display sex differences in halothane-induced polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2002;106:497–503. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023629.72479.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimov IR, Ermentrout B, Huang DT, Salama G. Activation and repolarization patterns are governed by different structural characteristics of ventricular myocardium: experimental study with voltage-sensitive dyes and numerical simulations. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1996;7:512–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1996.tb00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sherif N, Chinushi M, Caref EB, Restivo M. Electrophysiological mechanism of the characteristic electrocardiographic morphology of torsade de pointes tachyarrhythmias in the long-QT syndrome: detailed analysis of ventricular tridimensional activation patterns. Circulation. 1997;96:4392–4399. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.12.4392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sherif N, Gough WB, Restivo M. Reentrant ventricular arrhythmias in the late myocardial infarction period: mechanism by which a short-long-short cardiac sequence facilitates the induction of reentry. Circulation. 1991;83:268–278. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.1.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier DW, Wolf PD, Wharton JM, Tang AS, Smith WM, Ideker RE. Stimulus-induced critical point. Mechanism for electrical initiation of reentry in normal canine myocardium. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1039–1052. doi: 10.1172/JCI113945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gettes LS, Reuter H. Slow recovery from inactivation of inward currents in mammalian myocardial fibres. J Physiol. 1974;240:703–724. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Li H, London B, Nerbonne JM. Functional consequences of elimination of Ito,f and Ito,s. Early afterdepolarizations, atrioventricular block, and ventricular arrhythmias in mice lacking Kv1.4 and expressing a dominant-negative Kv4 α subunit. Circ Res. 2000;87:73–79. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, London B, Nerbonne JM. Kv1.4 underlies the slow outward K+ current in mouse ventricular myocytes and is upregulated in transgenic mice expressing a dominant negative Kv4 subunit. Circulation. 1999a;100:1–352. [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Xu H, London B, Nerbonne JM. Molecular basis of transient outward K+ current diversity in mouse ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1999b;521:587–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutstein DE, Morley GE, Tamaddon H, Vaidya D, Schneider MD, Chen J, Chien KR, Stuhlmann H, Fishman GI. Conduction slowing and sudden arrhythmic death in mice with cardiac-restricted inactivation of connexin43. Circ Res. 2001;88:333–339. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hondeghem LM. Development of class III antiarrhythmic agents. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;20:S17–S22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai A, Salama G. Optical mapping reveals that repolarization spreads anisotropically and is guided by fiber orientation in guinea pig hearts. Circ Res. 1995;77:784–802. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.4.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo HC, Cheng CF, Clark RB, Lin JJ, Lin JL, Hoshijima M, Nguyen-Tran VT, Gu Y, Ikeda Y, Chu PH, Ross J, Giles WR, Chien KR. A defect in the Kv channel-interacting protein 2 (KChIP2) gene leads to a complete loss of Ito and confers susceptibility to ventricular tachycardia. Cell. 2001;107:801–813. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B, Baker LC, Lee JS, Shusterman V, Choi BR, Kubota T, McTiernan CF, Feldman AM, Salama G. Calcium-dependent arrhythmias in transgenic mice with heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H431–H441. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00431.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B, Jeron A, Zhou J, Buckett P, Han X, Mitchell GF, Koren G. Long QT and ventricular arrhythmias in transgenic mice expressing the N terminus and first transmembrane segment of a voltage-gated potassium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998a;95:2926–2931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London B, Wang DW, Hill JA, Bennett PB. The transient outward current in mice lacking the potassium channel gene Kv1.4. J Physiol. 1998b;509:171–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.171bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley GE, Vaidya D, Samie FH, Lo C, Delmar M, Jalife J. Characterization of conduction in the ventricles of normal and heterozygous Cx43 knockout mice using optical mapping. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10:1361–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerbonne JM. Molecular basis of functional voltage-gated K+ channel diversity in the mammalian myocardium. J Physiol. 2000;525:285–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkova-Kirova PS, Gursoy E, Mehdi H, McTiernan CF, London B, Salama G. Electrical remodeling of cardiac myocytes from mice with heart failure due to the overexpression of tumor necrosis factor-α. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2098–H2107. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00097.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden DM. Torsade de pointes. Clin Cardiol. 1993;16:683–686. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960160910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama G, Lombardi R, Elson J. Maps of optical action potentials and NADH fluorescence in intact working hearts. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:H384–H394. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.2.H384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the ECG features of the LQT1 form of the long-QT syndrome: effects of β-adrenergic agonists and antagonists and sodium channel blockers on transmural dispersion of repolarization and torsade de pointes (see comments) Circulation. 1998;98:2314–2322. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JM, Clancy EA, Valeri CR, Ruskin JN, Cohen RJ. Electrical alternans and cardiac electrical instability. Circulation. 1988;77:110–121. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.77.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surawicz B. Contributions of cellular electrophysiology to the understanding of the electrocardiogram. Experientia. 1987;43:1061–1068. doi: 10.1007/BF01956040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surawicz B. Electrophysiologic substrate of torsade de pointes: dispersion of repolarization or early afterdepolarizations? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14:172–184. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szentadrassy N, Banyasz T, Biro T, Szabo G, Toth BI, Magyar J, Lazar J, Varro A, Kovacs L, Nanasi PP. Apico-basal inhomogeneity in distribution of ion channels in canine and human ventricular myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:851–860. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SA, Schuessler RB, Berul CI, Beardslee MA, Beyer EC, Mendelsohn ME, Saffitz JE. Disparate effects of deficient expression of connexin43 on atrial and ventricular conduction: evidence for chamber-specific molecular determinants of conduction. Circulation. 1998;97:686–691. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.7.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trepanier-Boulay V, St-Michel C, Tremblay A, Fiset C. Gender-based differences in cardiac repolarization in mouse ventricle. Circ Res. 2001;89:437–444. doi: 10.1161/hh1701.095644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya D, Morley GE, Samie FH, Jalife J. Reentry and fibrillation in the mouse heart. A challenge to the critical mass hypothesis. Circ Res. 1999;85:174–181. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan PC, Rudy Y. Cellular arrhythmogenic effects of congenital and acquired long-QT syndrome in the heterogeneous myocardium. Circulation. 2000;101:1192–1198. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.10.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Cheng J, Tandan S, Jiang M, McCloskey DT, Hill JA. Transient-outward K+ channel inhibition facilitates L-type Ca2+ current in heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:298–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wit AL, Allessie MA, Bonke FI, Lammers W, Smeets J, Fenoglio JJ., Jr Electrophysiologic mapping to determine the mechanism of experimental ventricular tachycardia initiated by premature impulses. Experimental approach and initial results demonstrating reentrant excitation. Am J Cardiol. 1982;49:166–185. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(82)90292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Guo W, Nerbonne JM. Four kinetically distinct depolarization-activated K+ currents in adult mouse ventricular myocytes. J General Physiol. 1999a;113:661–678. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.5.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Li H, Nerbonne JM. Elimination of the transient outward current and action potential prolongation in mouse atrial myocytes expressing a dominant negative Kv4 α subunit. J Physiol. 1999b;519:11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0011o.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Jeron A, London B, Han X, Koren G. Characterization of a slowly inactivating outward current in adult mouse ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1998;83:806–814. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.8.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]