Abstract

Ca2+ is vital for release of neurotransmitters and trophic factors from peripheral sensory nerve terminals (PSNTs), yet Ca2+ regulation in PSNTs remains unexplored. To elucidate the Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms in PSNTs, we determined the effects of a panel of pharmacological agents on electrically evoked Ca2+ transients in rat corneal nerve terminals (CNTs) in vitro that had been loaded with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator, Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 dextran or fura-2 dextran in vivo. Inhibition of the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase, disruption of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, or inhibition of the Na+–Ca2+ exchanger did not measurably alter the amplitude or decay kinetics of the electrically evoked Ca2+ transients in CNTs. By contrast, inhibition of the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) by increasing the pH slowed the decay of the Ca2+ transient by 2-fold. Surprisingly, the energy for ion transport across the plasma membrane of CNTs is predominantly from glycolysis rather than mitochondrial respiration, as evidenced by the observation that Ca2+ transients were suppressed by iodoacetate but unaffected by mitochondrial inhibitors. These observations indicate that, following electrical activity, the PMCA is the predominant mechanism of Ca2+ clearance from the cytosol of CNTs and glycolysis is the predominant source of energy.

Primary sensory neurons play a vital role in a wide range of physiological and pathophysiological processes, including detecting noxious and non-noxious stimuli, releasing trophic factors into peripheral tissues, and initiating neurogenic inflammation. Regulation of these and other processes by sensory neurons is, in many ways, dependent on intracellular free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and therefore on the mechanisms that underlie Ca2+ homeostasis.

Ca2+ has many diverse and important functions in cells and consequently its regulation, both temporally and spatially, must be tightly controlled for proper signalling to occur. In neurons, this regulation includes voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs) on the plasma membrane (PM), so that electrical activity may be ‘sensed’ by the internal signalling mechanisms of the cell. Peripheral sensory afferents express multiple types of VDCCs, including L-, N-, R- and T-type (Fox et al. 1987; Schild et al. 1994; Kim & Chung, 1999). In addition to Ca2+ influx across the PM, sensory neurons have effective mechanisms for amplifying Ca2+ signals, including Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) from intracellular stores through ryanodine receptors. Ca2+ can also be released from intracellular stores through inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (Thayer et al. 1988). To terminate Ca2+ signals, efficient Ca2+ clearance mechanisms must also exist. These include transport of Ca2+ across the PM by the PM Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA), and by the Na+–Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) (Verdru et al. 1997; Usachev et al. 2002). Ca2+ may also be transported from the cytosol into Ca2+-sequestering intracellular organelles, the most prominent of which are the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria. Both organelles have been shown to take up Ca2+ from the cytoplasm of sensory neurons (Shishkin et al. 2002).

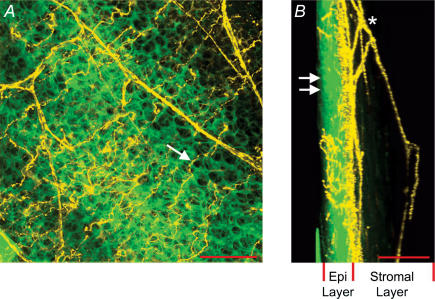

To date, investigations of Ca2+ homeostasis in primary sensory afferents have been limited to cell body and nerve trunk preparations (Thayer & Miller, 1990; Mayer et al. 1999). Although these studies have greatly increased our knowledge of sensory neuron physiology and Ca2+ homeostasis, caution is necessary when extrapolating such studies to peripheral sensory nerve terminals. Until recently, the small size (0.15–0.25 μm in diameter; Whitear, 1960) and physical inaccessibility of these terminals have precluded direct measurements of Ca2+ currents and Ca2+ signalling. We have developed a novel preparation for measuring Ca2+ transients evoked by electrical or chemical stimulation in the sensory nerve terminals of the rat cornea (Gover et al. 2003). The cornea has unique properties that make it an ideal preparation for studying Ca2+ dynamics in nociceptive sensory nerve terminals. In addition to being transparent, the cornea has the greatest density of sensory nerve innervation of any tissue (Lele & Weddell, 1956). The nerve terminals of the cornea are all free nerve endings which reside in the superficial epithelial cell layers no more than 50 μm from the surface of the cornea (Fig. 1; Zander & Weddell, 1951; MacIver & Tanelian, 1993). Ultrastructural studies have demonstrated that corneal nerve terminals are truly ‘free’, without Schwann cell ensheathment or fine specializations (Muller et al. 1996). The combination of a high density of nociceptive innervation, simple tissue structure, proximity of nerve terminals to the tissue surface and the transparency of the cornea makes the cornea an exceptional preparation for functional neuronal imaging. In the current work, we have used this preparation to examine [Ca2+]i regulation during electrically evoked Ca2+ transients.

Figure 1. Anatomy of sensory nerve terminals in the rat cornea.

A, flattened Z-stack image of cornea loaded with FM1-43. On the basis of their distinctive morphology, nerve fibres and epithelial cells are artificially coloured in yellow and green, respectively. Arrow indicates nerve terminal residing in the superficial epithelial cell layer. Scale bar, 50 μm. B, same Z-stack as in A but flattened with a 90 deg orientation with respect to A. In this orientation, the thickness of the epithelial cell layer (Epi Layer) is evident. Double arrows indicate surface of the epithelial cell layer. Asterisk indicates subepithelial nerve plexus residing in the stromal layer (collagen layer) of the cornea. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Methods

Fluorescent indicator loading in vivo and tissue dissection

Experiments were performed on isolated corneas from male Sprague-Dawley rats (140–300 g). All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland, Baltimore. For cornea dye loading, 0.25–1.0 μl of a solution containing 0.9% w/v NaCl, 20% w/v Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 dextran (OGB-1 dextran, 10 kDa; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) or 10% w/v tetramethylrhodamine dextran (10 kDa; Molecular Probes) and 1–2% v/v Triton X-100 (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was deposited on each cornea of a ketamine-anaesthetized animal for 1 min. After dye exposure, the eyes were rinsed with Ca2+- and Mg2+-free phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Rats were killed 16–60 h later by pentobarbital (100 mg kg−1, i.p.). Corneas were dissected directly from the animal immediately after death. Isolated corneas were maintained in an oxygenated Locke solution containing (mm): glucose 10, NaCl 136, KCl 5.6, NaH2PO4 1.2, NaHCO3 14.3, MgCl2 1.2 and CaCl2 2.2; pH 7.4. For experiments determining the effects of alkaline pH on Ca2+ regulation, we maintained the cornea in a solution containing (mm): glucose 10, NaCl 150, KCl 5.6, NaHCO3 5.0, tris(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane (Tris base) 10, MgCl2 1.2 and CaCl2 2.2.

Electrical stimulation

Corneal nerve terminals (CNTs) were activated by electric field stimulation with platinum electrodes placed on either side of the recording chamber. Electrical stimulation (50 pulses 10 Hz, 2 ms duration) were generated by a stimulator and delivered through a stimulus isolation unit (both from Astro-Medical, West Warwick, RI, USA). The stimulation frequency was chosen to be representative of physiological firing frequencies in CNTs (MacIver & Tanelian, 1993). The stimulation voltage was greater than threshold to ensure consistent neuronal activation (120–150 V), as detected by transient rises in [Ca2+]i. Corneas were continuously superfused with oxygenated Locke solution at room temperature (22–24°C) except where noted.

Calcium imaging

Ca2+ imaging of isolated corneas was performed on an upright epifluorescence microscope (Laborlux 12; Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a water-immersion objective (40 ×; NA, 0.8; Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Tissues were excited by the output of a 100 W mercury arc lamp that passed through a 480 nm bandpass filter (30 nm bandwidth). Fluorescence emission was passed through a 535 nm bandpass filter (40 nm bandwidth) before capture by a cooled CCD camera (Retiga Exi, Q-Imaging, Burnaby, Canada). An example image of a typical CNT loaded with OGB-1 dextran is shown in Fig. 1A of the Supplemental Material. The CNTs lie in the epithelial layer of the cornea, as seen through brightfield microscopy (Fig. 1B of the Supplemental Material). Excitation exposure was controlled by an electromechanical shutter (Uniblitz; Vincent Associates, Rochester, NY, USA) gated by transistor–transistor logic (TTL) pulses. Images were acquired at 0.5 Hz with 4 × 4 binning. MetaMorph software (Universal Imaging, Dowingtown, PA, USA) was used for instrument control, image acquisition and analysis. Ca2+ imaging of isolated corneas loaded with the Ca2+ indicator fura-2 dextran (10 kDa; Molecular Probes) was performed on an inverted microscope (TE200, Nikon) equipped with a UV-transmitting objective (40 ×, NA, 1.4; SuperFluor; Nikon). Fura-2 dextran fluorescence was alternately excited by 340 and 380 nm light from a monochromator (PolyChrome II; TILL Photonics, Gräfelfing, Germany), and fluorescence emission was passed through a 510 nm bandpass filter (full width at half maximum, 40 nm) before being captured with a cooled CCD camera (CoolSnap HQ; Roper Scientific, Tucson, AZ, USA). MetaFluor software was used for instrument control and data analysis.

Confocal imaging

Imaging of CNTs loaded with FM1-43 was performed on a Zeiss LSM 510 NLO microscope. Whole corneas were incubated in 5 μm FM1-43 (Molecular Probes) in Locke solution for 1 h at room temperature and then washed for 1 h in normal Locke solution. FM1-43 was excited at 488 nm (argon ion laser), and its fluorescence was filtered (500–550 nm bandpass) before quantification. Scans were at 512 pixel × 512 pixel resolution. Pixel dwell time was 1.6 μs, and intensity was digitized at 12 bit resolution. Z-stacks were analysed and compressed with MetaMorph software. Confocal microscopical imaging of nerve fibres labelled with tetramethylrhodamine dextran was performed on an inverted microscope with a 40 × water-immersion objective (Axiovert, LSM 410; Zeiss). Corneal sections were excited at 568 nm, and fluorescence emission was passed through a 590 nm long-pass filter before photometric detection.

Verification of drug access to the corneal epithelium

In studying sensory nerve terminals in intact corneas, we used the pharmacological agents cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), carbonyl cyanide 3-chloro-phenylhydrazone (CCCP) and KB-R7943, which, respectively, inhibit the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA), mitochondria and the NCX. The corneal epithelium, within which CNTs reside and whose cells surround the CNTs intimately, poses a barrier to the penetration of some drugs (Maurice & Mishima, 1984). Therefore it was important to verify that the drugs we used could gain access to the corneal epithelium. Corneal epithelial cells were loaded with OGB-1 dextran by ‘biolistic’ delivery. Briefly, 25 mg tungsten particles (∼1 μm diameter) were washed three times in 100% ethanol and spread out on a glass microscope slide to dry. OGB-1 dextran (5 mg) dissolved in 250 μl distilled water was placed on the tungsten particles and allowed to dry. Dye-coated particles were scraped off the glass slide, suspended in 1 ml 100% ethanol, and sonicated for 1 min. The particles were separated from ethanol by centrifugation and resuspended in 1 ml 100% ethanol. This suspension was stored at –20°C until use. Tungsten particles were delivered to the cornea with a custom-fabricated gene gun modified from the particle inflow gun (PIG) designed by Finer et al. (1992). The stock tungsten particle suspension was diluted 1 : 10 with 100% ethanol. The diluted suspension (1 μl) was shot from the gun onto the whole cornea, on the intact eyeball. After loading, the corneas were allowed to recover for 30 min prior to recording. Corneal epithelial cells loaded with OGB-1 dextran were monitored by Ca2+ imaging as 5 μm CPA, 2 μm CCCP or 5 μm KB-R7943 were bath applied to the cornea. In all cases, drug application evoked a Ca2+ response in ≤ 3 min (Fig. 2A–C in the Supplemental Material). These tests confirm that the drugs used in this study readily permeate the corneal epithelium – well within the time frame of drug incubation used in the experiments presented below.

Data analysis

Ca2+ indicator measurements for isolated corneas are reported as the fractional change in fluorescence intensity relative to baseline fluorescence (ΔF/F0), which was determined as follows. Within a temporal sequence of fluorescence images, a region of interest (ROI) was drawn around a selected portion of each CNT to be analysed. The fluorescence signal from each terminal was calculated as the pixel-averaged intensity within each ROI. The precise boundary of each ROI enclosing a terminal was replicated and placed over an adjacent region of the image that was devoid of nerve processes. The pixel-averaged intensity from each ROI was taken as background and was subtracted from the fluorescence signal obtained for the corresponding nerve terminal to yield the background-corrected fluorescence signal (F) from that terminal. In electrical stimulation experiments, sequences of images were acquired over extended time periods. In these experiments, we typically observed a slight downward drift in baseline, which was principally attributable to photo-bleaching of the indicator. In such cases, the drift was always well fitted by a low-amplitude single-exponential decay. The fitted baseline value (F0) at every time point was then used to calculate ΔF/F0. The decay of Ca2+ transients were determined from ΔF/F0 traces that were smoothed by three-point adjacent averaging. ΔF/F0 values are reported as mean ± s.e.m. For CNTs loaded with fura-2 dextran, [Ca2+]i was derived using the ratio method of Grynkiewicz et al. (1985). All fura-2 fluorescence records were corrected for background fluorescence by subtracting the light intensity measured in an adjacent region as described above. [Ca2+]i was calculated using the equation of Grynkiewicz et al. (1985):

where R =F340/F380, with F340 and F380 being fura-2 emission intensities measured with 340 and 380 nm excitation, respectively; Rmin and Rmax are the values of R at zero and saturating Ca2+ concentrations, respectively; and Sf2/Sb2 is the ratio of emission intensities for the Ca2+-free and Ca2+-bound indicator when excited at 380 nm. The Kd used for fura-2 dextran was 240 nm; Rmin, Rmax and Sf2/Sb2 were determined in vitro. Ca2+ transients were smoothed by three-point adjacent averaging prior to analysis. [Ca2+]i values are reported as mean ± s.e.m. In all cases, n refers to the number of CNTs recorded; one or two CNTs were recorded from each corneal section. Statistical significance was determined by paired t test; P < 0.05 was considered significant. For comparison of groups of CNTs, statistical significance was determined by unpaired t test; P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

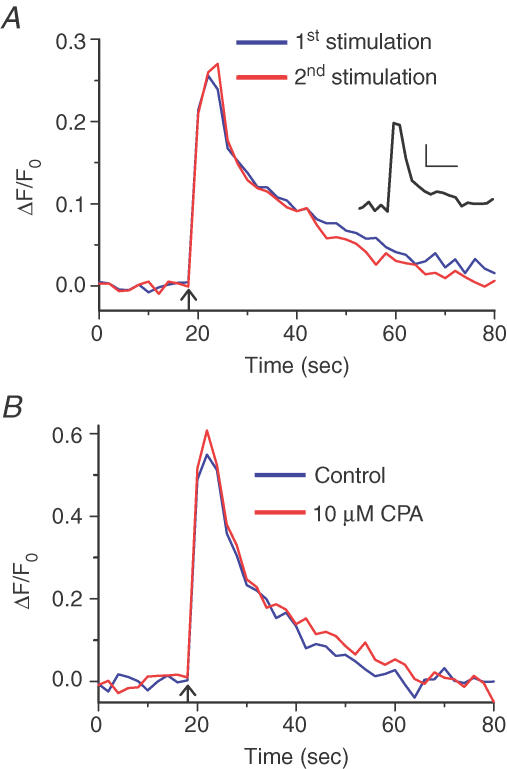

Role of ER in Ca2+ homeostasis

Previously, we have reported that action potential (AP)-evoked Ca2+ influx into CNTs occurs primarily through L-type VDCCs (Gover et al. 2003). We performed a series of experiments to determine whether intracellular Ca2+ stores have a functional role in either releasing Ca2+ into, or removing Ca2+ from, the cytoplasm subsequent to Ca2+ influx through the PM. Electrical field stimulation (50 stimuli at 10 Hz) applied to the isolated cornea reliably evoked Ca2+ transients in individual CNTs. In any particular CNT, the Ca2+ transients were reproducible in both amplitude and time course of decay, as demonstrated by the representative experiment shown in Fig. 2A, where two Ca2+ transients evoked by identical stimuli 10 min apart were essentially identical. Similar results were obtained for a total of seven CNTs studied: ΔF/F0 of the first electrically evoked Ca2+ was 0.36 ± 0.18, while the second transient evoked 10–20 min later showed peak ΔF/F0 of 0.36 ± 0.15 (P = 0.973). The time for the Ca2+ transient to decay from 95% to 10% of peak amplitude (t95–10) was 43.9 ± 5.7 and 31.7 ± 3.8 s for the first and second stimulus, respectively (n = 7, P = 0.136). To determine the absolute change in [Ca2+]i in CNTs during AP activity, we evoked Ca2+ transients electrically in CNTs loaded with the ratiometric Ca2+ indicator, fura-2 dextran. We observed that electrically evoked Ca2+ transients had a peak Ca2+ rise of 442 ± 114 nm from a resting [Ca2+]i of 92 ± 12 nm (n = 7; 50 field stimuli at 10 Hz; Fig. 2A inset). The high reproducibility of the evoked Ca2+ transients in individual CNTs enabled us to use the same nerve terminals as their own controls in subsequent experiments where Ca2+ transporter antagonists were used.

Figure 2. Reproducibility of Ca2+ transients evoked in corneal nerve terminals (CNTs) by electrical field stimulation and the unimportance of intracellular Ca2+ stores in Ca2+ regulation.

A, two Ca2+ transients evoked 10 min apart by electric field stimulation (50 stimuli at 10 Hz) in an individual sensory nerve terminal in an isolated cornea. The first (blue) and second (red) Ca2+ transients were essentially super-imposable. In seven CNTs studied, the two transients did not differ in amplitude (P = 0.973) or decay time (P = 0.136). Arrow marks time of stimulation. Inset, Ca2+ transients evoked by electric field stimulation (50 stimuli at 10 Hz) in individual CNTs loaded with the Ca2+ indicator fura-2 dextran (average data from n = 7 CNTs). Scale bars represent 100 nm[Ca2+] (vertical) and 10 s (horizontal). B, Ca2+ transient evoked in CNTs by electric field stimulation (50 stimuli at 10 Hz; blue trace, average data from nine CNTs). After incubation with 10 μm CPA for 10 min, identical electrical stimulation evoked a Ca2+ transient that was similar in peak amplitude (P = 0.571) and 95%–10% decay time (P = 0.294) (red trace, average data from n = 9 CNTs).

To test the role of the ER in Ca2+ homeostasis we used the SERCA inhibitors CPA and 2,5-di-tert-butylhydroquinone (DBHQ; Inesi & Sagara, 1994). SERCA mediates ATP-dependent Ca2+ uptake from the cytosol into the ER (Lytton et al. 1992). Therefore, if SERCA contributes to the decay of the Ca2+ transient, SERCA inhibition should lengthen the decay time. Moreover, in the presence of SERCA inhibitors, SERCA-dependent intracellular Ca2+ stores will run down. Therefore, if intracellular Ca2+ stores release Ca2+ consequent to Ca2+ influx through the PM (i.e. CICR), the Ca2+ transient amplitude should be reduced in the presence of the SERCA inhibitors. In nine CNTs, the peak amplitude of ΔF/F0 of the electrically evoked Ca2+ transient was 0.57 ± 0.16 under control conditions, and essentially unchanged at ΔF/F0 of 0.62 ± 0.11 after SERCA blockade by incubation with 10 μm CPA for 10 min (n = 9, P = 0.571; Fig. 2B). Decay kinetics were also not significantly altered, with t95–10 being 23.1 ± 3.9 and 26.3 ± 4.8 s before and after SERCA inhibition, respectively (n = 9, P = 0.294). Similar results were also observed when 20 μm DBHQ, another SERCA inhibitor, was used (P = 0.605 and 0.676 for amplitude and t95–10, respectively, n = 7). Finally, SERCA blockers by themselves had no effect on resting [Ca2+]i in CNTs. Together, these results indicate that the ER Ca2+ stores contribute negligibly to Ca2+ transients in CNTs.

The activity of enzymes controlling intracellular Ca2+ stores is expected to be highly temperature-dependent (Dode et al. 2001). Therefore, conducting our experiments at room temperature may have minimized the contribution of SERCA to Ca2+ regulation and, consequently, may have contributed to negative results with SERCA blockers. To determine whether the ineffectiveness of SERCA blockers to modify CNT Ca2+ transients was due to lower-than-physiological temperatures, we repeated the SERCA experiments with CPA at a more physiological temperature. We observed that Ca2+ transient decay times were significantly faster when CNTs were excited at 35–37°C rather than at room temperature (P < 0.001, n = 40 and 12 for 22–24°C and 35–37°C, respectively; Fig. 4). Ca2+ transient peak amplitudes were not significantly different at room temperature (22–24°C) or physiological temperature (35–37°C) (P = 0.183). Although the Ca2+ transients evoked at 35–37°C were significantly faster, our CPA experiments performed at 35°C mirrored those done at room temperature: electrically evoked Ca2+ transients peaked at ΔF/F0 of 0.53 ± 0.14 and 0.46 ± 0.11 before and after incubation with 5 μm CPA for 15 min, respectively (n = 3, P = 0.124). The corresponding t95–10 values were 14.6 ± 5.5 and 11.9 ± 2.5 s (n = 3, P = 0.614). The above results demonstrate that in CNTs, ER Ca2+ stores contribute neither to the rise nor to the fall of the Ca2+ transient.

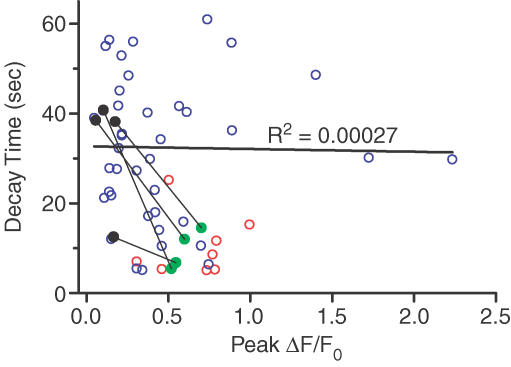

Figure 4. Ca2+ transient decay times but not peak Ca2+ transient amplitudes are dependent on temperature and glycolysis.

Peak amplitudes and 95%–10% decay times of Ca2+ transients were plotted for individual CNTs excited by electrical field stimulation (50 stimuli at 10 Hz). Each point represents data from an individual CNT excited either at room temperature (22–24°C, blue) or at physiological temperature (35–37°C, red and green). There was no correlation between peak amplitudes and 95%–10% decay times (R2= 0.00027). Average 95%–10% decay times were significantly different between experiments performed at 22–24°C and 35–37°C (P < 0.001, n = 40 and 12, for 22–24°C and 35–37°C, respectively). For experiments with iodoacetate, the temperature was 36°C; pre- and post-drug data are shown by green and black points, respectively, and pre- and post-drug data from the same CNT are connected by a thin line. Solid black line is the result of linear regression performed on pre-drug data points acquired at room temperature.

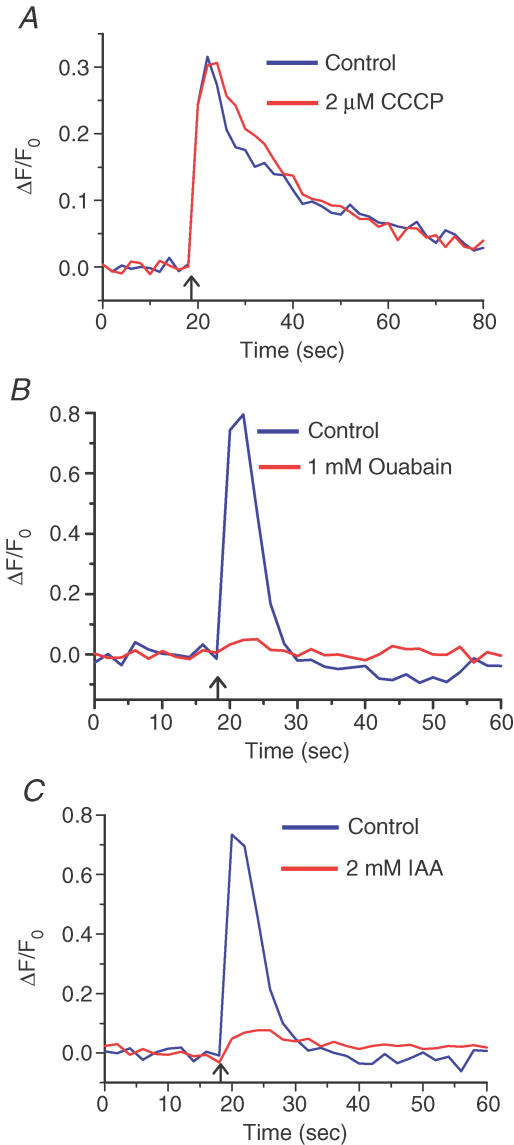

Role of mitochondria in Ca2+ homeostasis

Another organelle that could contribute to Ca2+ homeostasis is the mitochondrion (Werth & Thayer, 1994). To determine the contribution of mitochondria to Ca2+ regulation, we used the protonophore CCCP. The ability of mitochondria to sequester Ca2+ depends on the normally high electrical potential across the mitochondrial membrane (inside negative). Disruption of this large membrane potential with protonophores leads to release of Ca2+ from the mitochondrial stores and disables Ca2+ uptake from the cytosol by the mitochondria (Werth & Thayer, 1994). In CNTs at room temperature, before and after a 20 min incubation with 2 μm CCCP, the amplitudes of electrically evoked Ca2+ transients were not significantly different at ΔF/F0 of 0.32 ± 0.12 and 0.31 ± 0.089, respectively (n = 5, P = 0.985; Fig. 3A). Similarly, the Ca2+ transient decay times were also not affected: t95–10 of 50.8 ± 4.6 and 48.7 ± 0.7 s before and after CCCP treatment, respectively (n = 5, P = 0.75).

Figure 3. Glycolysis not mitochondrial respiration is critical for Ca2+ clearance in corneal nerve terminals (CNTs).

A, Ca2+ transient evoked in CNTs by electric field stimulation (50 stimuli at 10 Hz; blue trace, average data from n = 5 CNTs). After incubation with 2 μm CCCP for 20 min, electrical stimulation evoked a Ca2+ transient that was similar to the first transient in amplitude (P = 0.985) and 95%–10% decay time (P = 0.75) (red trace, average data from n = 5 CNTs). B, Ca2+ transients evoked in CNTs by electric field stimulation (50 stimuli at 10 Hz) before (blue) and after (red) 20 min incubation with 1 mm ouabain (traces are average data from n = 5 CNTs). Inhibition of the Na+–K+-ATPase by ouabain reduced the Ca2+ transient amplitude by 82 ± 1.2% (P = 0.042, n = 5). C, Ca2+ transients evoked in CNTs by electric field stimulation (50 stimuli at 10 Hz) before (blue) and after (red) 20 min incubation with 2 mm iodoacetate (IAA) (traces are average data from n = 5 CNTs). Inhibition of glycolysis by IAA reduced the Ca2+ transient amplitude by 82 ± 4.3% (P = 0.003, n = 5) and slowed its decay 3.5-fold (P = 0.035). All experiments were done at 35–37°C.

Mitochondrial sequestration of Ca2+ is highly temperature-dependent in some preparations (David & Barrett, 2000). To determine whether the ineffectiveness of protonophores to modify Ca2+ transients in CNTs was attributable to lower-than-physiological temperatures, we conducted a series of experiments with CCCP at 36°C. In CNTs at 36°C, the amplitudes of electrically evoked Ca2+ transients before and after a 15 min incubation with 2 μm CCCP were not significantly different at ΔF/F0 of 0.74 ± 0.11 and 0.62 ± 0.15, respectively (n = 4, P = 0.331). The corresponding decay times were also similar: t95–10 values were 8.6 ± 2.4 for control and 11.4 ± 3.5 s in the presence of CCCP (n = 4, P = 0.129). These results reinforce those obtained at room temperature, and indicate that in CNTs, mitochondria do not play a significant role in Ca2+ regulation during a Ca2+ transient. These results are unlikely to be attributable to the inability of CCCP to reach the CNTs (see Methods and Supplemental Material).

Dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential by protonophores leads to rapid depletion of the ATP reserve in neurons (Budd & Nicholls, 1996). Vital transporters such as the Na+–K+-ATPase and the PMCA should be severely blocked by ATP depletion, and yet elimination of mitochondria as a source of ATP had no effect on the Ca2+ transients in CNTs. Direct blockade of these transporters, however, did severely affect the normal functioning of CNTs. Incubation with ouabain, a Na+–K+-ATPase inhibitor, strongly attenuated the electrical-evoked Ca2+ transient in five out of six CNTs tested. The amplitudes of the electrically evoked Ca2+ transients before and after a 20 min incubation with 1 mm ouabain were significantly different at ΔF/F0 of 0.67 ± 0.25 and 0.075 ± 0.043, respectively (n = 5, P = 0.042; Fig. 3B). In one CNT, 1 mm ouabain appeared to have no affect. Next, we investigated whether glycolysis could be a major source of ATP in CNTs. It is remarkable that a 20 min incubation at 36°C with 2 mm iodoacetate, an inhibitor of glycolysis, reduced the electrically evoked Ca2+ transient in CNTs by 82 ± 4% (n = 5; Fig. 3C). Indeed, in one CNT, electrical stimulation evoked no Ca2+ response at all. The Ca2+ transient amplitudes (ΔF/F0) before and after iodoacetate incubation were 0.775 ± 0.098 and = 0.134 ± 0.027, respectively (n = 5, P = 0.003). The control Ca2+ transients decayed with t95–10 = 9.7 ± 2.1 s (n = 4), whereas the small Ca2+ transients evoked in the presence of iodoacetate decayed much more slowly (t95–10, 32.5 ± 6.7 s; n = 4, P = 0.035). The above observations suggest that inhibition of glycolysis had at least two related manifestations. First, Na+–K+-ATPase activity was attenuated, leading to reduced Na+ and K+ electrochemical gradients, which could not support AP generation under electric field stimulation. This, in turn, limited activation of L-type VDCCs, which are the principal mediators of electrically evoked Ca2+ transients in CNTs (Gover et al. 2003). Second, the PM Ca2+- ATPase activity was also attenuated, so that basal [Ca2+]i could not be restored efficiently even after a small [Ca2+]i rise. Below, we further demonstrate the importance of the PMCA in CNTs. It could be the case that the differences in the time course of the Ca2+ transient decay before and after incubation with iodoacetate merely reflect a dependence of Ca2+ clearance kinetics on [Ca2+]i (i.e. larger Ca2+ transients are cleared faster). This proved not to be the case: we observed no correlation between the peak amplitude and decay time of the Ca2+ transients (R2= 0.00027; Fig. 4).

Role of the NCX in Ca2+ efflux

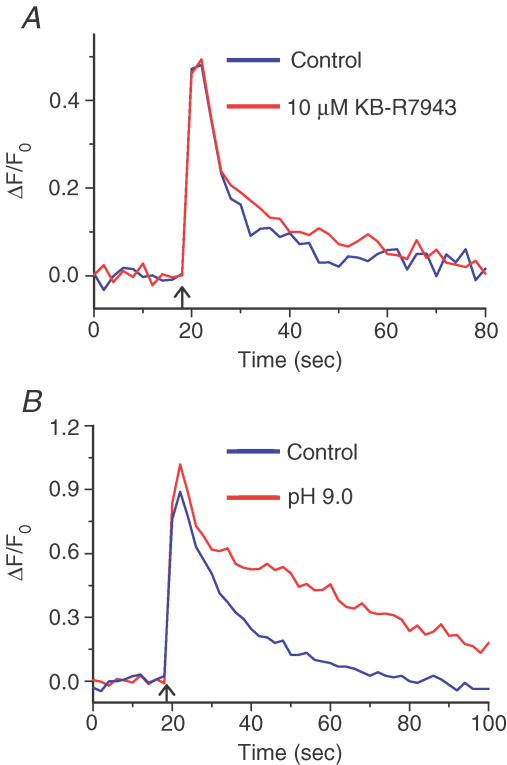

We next performed a series of experiments to determine how Ca2+ is extruded from the cytosol across the PM. Two mechanisms for transporting Ca2+ across the PM were explored: the NCX (Verdru et al. 1997) and the PMCA (Benham et al. 1992). To determine the role of the NCX in Ca2+ clearance during an electrically evoked Ca2+ transient, we used the isothiourea derivative KB-R7943, which selectively inhibits NCX with an IC50 of 1 μm under physiological conditions (Kimura et al. 1999). Treatment with KB-R7943 did not significantly affect electrically evoked Ca2+ transients in CNTs: Ca2+ transient amplitudes (ΔF/F0) 0.516 ± 0.098 and 0.512 ± 0.09, respectively, before and after a 10 min incubation with 10 μm KB-R7943 (n = 6, P = 0.969; Fig. 5A). The corresponding t95–10 values were also similar, being 24.8 ± 8.3 and 24.4 ± 5.0 s, respectively (n = 6, P = 0.943). These observations suggest that in CNTs, the NCX is not a significant Ca2+ efflux mechanism during an electrically evoked Ca2+ transient.

Figure 5. The plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA), but not the Na+–Ca2+ exchanger, plays a significant role in Ca2+ homeostasis in corneal nerve terminals (CNTs).

A, Ca2+ transients evoked in CNTs by electrical field stimulation (50 stimuli at 10 Hz) before (blue) and after (red) 10 min incubation with 10 μm KB-R7943 (traces are average data from n = 6 CNTs). The Ca2+ transients had similar amplitudes (P = 969, n = 6) and 95%–10% decay times (P = 0.943). B, Ca2+ transients evoked in a CNT by electric field stimulation (50 stimuli at 10 Hz) before (blue) and after (red) 25 min exposure to alkaline extracellular pH (pHo 9.0) to block the PMCA. The Ca2+ transient amplitudes were similar (P = 0.688, n = 6); however, decay of the transients was much slower at pH 9.0 than at pH 7.3 (95%–10% decay times were 2-fold longer; P = 0.006).

Role of the PMCA in Ca2+ efflux

Finally, we tested the possibility that the PMCA is the predominant mechanism for Ca2+ extrusion across the PM of CNTs. Although there are no selective PMCA antagonists at present, alkaline extracellular pH can inhibit the PMCA; the ATP-dependent Ca2+ pump removes Ca2+ from the cytoplasmic side of the PM and, in exchange, protons are counter-transported across the PM into the cytoplasm (Carafoli, 1992). Therefore, reducing the extracellular proton concentration attenuates PMCA activity. At physiological extracellular pH (pHo 7.3), the amplitude of electrically evoked Ca2+ transients in CNTs was 0.82 ± 0.29 (n = 6), which was unchanged after exposure to pHo = 9.0 for 25 min (0.84 ± 0.32; n = 6, P = 0.688). In remarkable contrast, the shift in pHo from 7.3 to 9.0 increased t95–10 2-fold, from 27.5 ± 4.8 to 56.0 ± 9.6 s (n = 6, P = 0.006; Fig. 5B). The effect of alkaline pHo was reversed upon return to physiological pHo (data not shown). These results indicate that the PMCA is the principal mechanism for Ca2+ removal from the cytoplasm of CNTs during a Ca2+ transient.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to understand Ca2+ homeostasis in peripheral nerve terminals of primary sensory neurons. We used a newly developed in vitro preparation, CNTs of the rat labelled with fluorescent Ca2+ indicators (Gover et al. 2003). In cell bodies and axons of primary sensory neurons, many diverse processes have been shown to control the clearance of Ca2+. These include distinct ATP-dependent Ca2+ pumps in the plasma, endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial membranes, NCX and Ca2+ buffering proteins (Thayer & Miller, 1990; Verkhratsky & Shmigol, 1996; Mayer et al. 1999). In order to determine which of these processes may support Ca2+ homeostasis in CNTs, we studied the effects of a variety of pharmacological reagents that interfere with different Ca2+ clearance mechanisms. The actions of these reagents were assessed by measuring the magnitude and time course of the Ca2+ transients evoked by electrical field stimulation of CNTs in vitro.

CICR in CNTs

We have demonstrated that the L-type VDCC is the major ion channel responsible for Ca2+ influx across the PM of CNTs during electrical activity (Gover et al. 2003). Application of SERCA inhibitors (CPA or DBHQ) did not significantly affect the amplitude or the kinetics of the Ca2+ transients in CNTs, suggesting that ER Ca2+ stores do not play a significant role in electrically evoked Ca2+ signalling in the peripheral nerve terminals of primary sensory neurons.

CICR from intracellular Ca2+ stores has been characterized in all primary afferent cell bodies studied to date, yet its physiological functions in these neurons are incompletely defined. One known function of CICR is to amplify AP-evoked Ca2+ transients to support a slowly developing and long-lasting (many seconds) after-spike hyperpolarization recorded in vagal afferent cell bodies (Moore et al. 1998). This slow afterpotential controls spike frequency accommodation and excitability of vagal afferent somata (Weinreich & Wonderlin, 1987). In contrast to primary sensory somata, Ca2+ transients recorded in CNTs were not modified by SERCA inhibitors such as DBHQ or CPA. Non-sensory peripheral nerve terminals such as motor nerve terminals, sympathetic nerve terminals and cholinergic nerve terminals have been reported to utilize CICR (Onodera, 1973; Smith & Cunnane, 1996; Narita et al. 2000). The difference in Ca2+ release mechanisms between afferent and efferent nerve terminals may be due to the different requirements for different rates of neurotransmitter release. Owing to their large surface to volume ratio, CNTs may not require CICR to substantially elevate [Ca2+]i. We estimate that the surface to volume ratio of a 1 μm diameter CNT is 29 times greater than that of the average trigeminal ganglion cell body. This greater surface to volume ratio could enable CNTs to support robust Ca2+ transients following activation of VDCCs even without Ca2+ release from intracellular stores.

The role of mitochondria in Ca2+ homeostasis

In addition to SERCA, mitochondria can also have a significant effect on Ca2+ buffering in nerves by attenuating the amplitude and prolonging the duration of Ca2+ transients (Werth & Thayer, 1994; Shishkin et al. 2002). Ultrastructural studies have revealed prominent clusters of mitochondria throughout CNTs (Hoyes & Barber, 1976; Beckers et al. 1992). It was therefore surprising that manipulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering had no effect on the Ca2+ transients in CNTs recorded at either room temperature (22–24°C) or physiological temperature (35–37°C). Lack of an observable effect of mitochondria on CNT Ca2+ transients may be attributable to several causes. The first is technical: mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake generally functions when [Ca2+]i is severely elevated, such as following excessive nerve stimulation or pathological stimuli (Thayer et al. 2002). Thus, it was possible that the electrical stimulation protocols employed in the present work did not produce as large a Ca2+ load in CNTs. Direct measurements showed that electrically evoked Ca2+ transients had a peak Ca2+ concentration of 442 ± 114 nm from a resting [Ca2+]i of 92 ± 12.0 nm. Werth & Thayer (1994) showed that mitochondria buffered Ca2+ in dorsal root ganglion somata when electrically evoked Ca2+ loads reached > 450 nm. Therefore, we conclude that the observed lack of effect of mitochondria on Ca2+ transients is unlikely to be attributed to our electrically evoked Ca2+ transients having been too small. The reasons for the apparently minor role of mitochondria observed in CNTs may be biological. First, mitochondria in CNTs are not homogeneously distributed; there is preferential localization of mitochondria in CNTs at the periphery of the cornea, whereas CNTs closer to the centre of the cornea appear to have fewer mitochondria (Hoyes & Barber, 1976). Second, it is possible that the CNT mitochondrial Ca2+ stores are already nearly full prior to electrical stimulation and therefore are unable to take up more Ca2+ during nerve stimulation. Finally, because the surface to volume ratio in CNTs is so large, PM-associated Ca2+ efflux mechanisms may predominate over intracellular Ca2+-sequestering mechanisms.

The role of glycolysis in Ca2+ homeostasis

The likely depletion of ATP after dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential by protonophores (Budd & Nicholls, 1996) appeared to have little effect on electrically evoked Ca2+ transients in CNTs. We have demonstrated that multiple ATP-driven pumps are active and necessary for normal CNT functioning. These pumps include the ouabain-sensitive Na+–K+-ATPase and the PMCA. We have also demonstrated that glycolysis is required for normal CNT function. After incubation with the glycolysis inhibitor, iodoacetate, the electrically evoked Ca2+ transients were significantly smaller and decayed back to baseline significantly more slowly. There was a modest increase in resting [Ca2+]i in CNTs upon application of iodoacetate (ΔF/F0 = 0.39 ± 0.019, n = 5). The increase in resting [Ca2+]i indicates that glycolysis is necessary for Ca2+ homeostasis in CNTs even under resting conditions. Because the resting [Ca2+]i only increased ∼40%, the observed attenuation of the electrically evoked Ca2+ transients is physiological and not the result of indicator saturation. For reasonable resting [Ca2+]i values of 50, 75 and 100 nm, the maximum values of ΔF/F0 for OGB-1 dextran are 3.6, 2.6 and 2.1, respectively (Gover et al. 2003). The rise in ΔF/F0 baseline in response to iodoacetate was always much smaller than these predicted maxima, suggesting that our measurements were unlikely to have been distorted by indicator saturation. Our findings suggest that inhibition of glycolysis leads to reduced Na+ and K+ electrochemical gradients (as a result of reduced Na+–K+-ATPase activity) and reduced PMCA activity, so that basal [Ca2+]i could not be restored efficiently even after a small [Ca2+]i rise. The small rise in [Ca2+]i observed in the presence of iodoacetate may result from direct activation of VDCCs. We have observed that after incubation with the Na+ channel blocker, lidocaine, field stimulation can produce small Ca2+ transients in some nerve terminals (data not shown). We therefore conclude that our field stimulation protocol may depolarize some CNTs sufficiently to activate VDCCs directly. Given that CNTs derive their energy predominantly from glycolysis, the question arises as to the role of mitochondria in CNT function. One possibility is that mitochondria in CNTs serve an important role following nerve terminal injury.

Role of plasmalemmal NCX

Most of the Ca2+ in the cytoplasm of CNTs during a Ca2+ transient must leave through the PM. In sensory somata or peripheral axons, blocking the NCX had little, if any, effect on Ca2+ transients (Thayer & Miller, 1990; Wächtler et al. 1998; see however, Verdru et al. 1997). In this study, selective blockade of NCX with KB-R7943 did not alter Ca2+ transients in CNTs. Lack of NCX activity in the CNTs is surprising, because the NCX seems well suited for Ca2+ removal in a structure with a very large surface to volume ratio and therefore presumably high Ca2+ turnover. Indeed, immunostaining has revealed NCX localization at neuromuscular junctions, and at synapses in spinal and brain tissue (Luther et al. 1992). Functionally, the NCX does not contribute to the decay of Ca2+ transients in vagal axons, which also presumably have large surface to volume ratio (Wächtler et al. 1998).

PM Ca2+ pumps

Removal of Ca2+ across the PM of sensory somata appears to be dominated by the PMCA (Usachev et al. 2002). Unfortunately, there are currently no selective pharmacological inhibitors of the PMCA. In an ATP-dependent process, for each Ca2+ ion extruded, the PMCA counter-transports two protons (H+) into the cytosol. Thus, removal of extracellular H+ effectively inhibits PMCA-mediated Ca2+ efflux (Carafoli, 1992). In CNTs, electrically evoked Ca2+ transients decayed much more slowly in the presence of alkaline extracellular saline. This effect was reversed upon return to physiological pH (data not shown).

The apparent simplicity of CNTs with respect to Ca2+ homeostasis may be understandable in view of the large surface-to-volume ratio of the nerve terminals. The large surface-to-volume ratio implies that AP-evoked Ca2+ influx can elevate [Ca2+]i much more effectively in CNTs than in sensory somata. Therefore, Ca2+ amplification through a mechanism such as CICR would not be necessary in CNTs. Similarly, the large surface to volume ratio also means that efflux mechanisms would remove Ca2+ from the cytosol more efficiently in CNTs than in sensory cell bodies. For these reasons, it is perhaps not surprising that the geometrical differences between the cell bodies and the nerve terminals translate into mechanistic differences in ion transport.

Collectively, our studies on CNTs reveal that the major pathway for Ca2+ influx following an AP is via L-type VDCCs (Gover et al. 2003), and that the PMCA is the predominant Ca2+ clearance mechanism in these nerve terminals. It is well established that the cornea is innervated by both nociceptive C- and Aδ-fibre types and most of these fibres are sensitive to capsaicin (MacIver & Tanelian, 1993; Gover et al. 2003). It is therefore noteworthy, that our studies demonstrate homogenous Ca2+ regulatory mechanisms across fibre types. It will be interesting to determine how these Ca2+ regulatory systems support known functions of CNTs; namely, nociception and secretion of neurotrophic factors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Michael Gold for helpful discussions and for reviewing a previous version of this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from NIH (NS-22069 to D.W. and GM-56481 to J.P.Y.K.) and Conselho Nacional para o Progresso da Ciência (to T.H.V.M.).

Supplementary material

The online version of this paper can be accessed at:

DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.119008

http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2006.119008/DC1 and contains supplemental material consisting of two figures:

Typical corneal nerve terminals (CNTs) coursing through the corneal epithelial cell layer.

Supplemental Figure 1. Typical corneal nerve terminals (CNTs) coursing through the corneal epithelial cell layer. A, Typical CNT loaded with the Ca2+ indicator Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 dextran (10 kDa) 24 hr before imaging with a cooled CCD camera. Scale bar for A is equal to 10 μm. B, CNTs loaded with the fluorophore tetramethylrhodamine dextran (10,000 MW) 24 hr before imaging with confocal microscopy. Corneal epithelium in the same object plane as the CNT was imaged by detection of transmitted laser light (633 nm) by the confocal's transmission photomultiplier tube. Scale bar for B is equal to 20 μm.

Assessment of drug penetration into the corneal epithelium.

Supplemental Figure 2. Assessment of drug penetration into the corneal epithelium. To determine drug access to the corneal epithelium, wherein corneal nerve terminals reside, the epithelia in intact corneas were loaded biolistically with OGD-1 dextran (see Methods) and [Ca2+]i changes in epithelial cells were imaged as drugs that can alter Ca2+ homeostasis were bath-applied. Cells deep within the corneal epithelium (∼50 μm from the surface) were imaged.\ A. Bath application of 5 μm CPA (blue bar) elevated [Ca2+]i in epithelial cells in ∼60 s. B. [Ca2+]i in epithelial cells increased ∼120 s after 2 μm CCCP was bath-applied (green bar). C. Bath-applied KB-R7943 (5 ?M; red bar) evoked a rise in [Ca2+]i in epithelial cells in ∼70 s. Rises in epithelial [Ca2+]i tended to be oscillatory as can be seen from the rises in [Ca2+]i at the end of each trace.

This material can also be found as part of the full-text HTML version available from http://www.blackwell-synergy.com

References

- Beckers HJ, Klooster J, Vrensen GF, Lamers WP. Ultrastructural identification of trigeminal nerve endings in the rat cornea and iris. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:1979–1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham CD, Evans ML, McBain CJ. Ca2+ efflux mechanisms following depolarization evoked calcium transients in cultured rat sensory neurones. J Physiol. 1992;455:567–583. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd SL, Nicholls DG. A reevaluation of the role of mitochondria in neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis. J Neurochem. 1996;66:403–411. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66010403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carafoli E. The Ca2+ pump of the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:2115–2118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David G, Barrett EF. Stimulation-evoked increases in cytosolic [Ca2+] in mouse motor nerve terminals are limited by mitochondrial uptake and are temperature-dependent. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7290–7296. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07290.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dode L, Van Baelen K, Wuytack F, Dean WL. Low temperature molecular adaptation of the skeletal muscle sarco (endo) plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 1 (SERCA 1) in the wood frog (Rana sylvatica) J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3911–3919. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007719200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer JJ, Vain P, Jones MW, McMullen MD. Development of the particle inflow gun to plant cells. Plant Cell Rep. 1992;11:232–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00233358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AP, Nowycky MC, Tsien RW. Single-channel recordings of three types of calcium channels in chick sensory neurones. J Physiol. 1987;394:173–200. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gover TD, Kao JPY, Weinreich D. Calcium signaling in single peripheral sensory nerve terminals. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4793–4797. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04793.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyes AD, Barber P. Ultrastructure of the corneal nerves in the rat. Cell Tissue Res. 1976;172:133–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00226054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inesi G, Sagara Y. Specific inhibitors of intracellular Ca2+ transport ATPases. J Membr Biol. 1994;141:1–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00232868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HC, Chung MK. Voltage-dependent sodium and calcium currents in acutely isolated adult rat trigeminal root ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:1123–1134. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.3.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura J, Watano T, Kawahara M, Sakai E, Yatabe J. Direction-independent block of bi-directional Na+/Ca2+ exchange current by KB-R7943 in guinea-pig cardiac myocytes. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:969–974. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lele PP, Weddell G. The relationship between neurohistology and corneal sensibility. Brain. 1956;79:119–154. doi: 10.1093/brain/79.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther PW, Yip RK, Bloch RJ, Ambesi A, Lindenmayer GE, Blaustein MP. Presynaptic localization of sodium/calcium exchangers in neuromuscular preparations. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4898–4904. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-12-04898.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton J, Westlin M, Burk SE, Shull GE, MacLennan DH. Functional comparisons between isoforms of the sarcoplasmic or endoplasmic reticulum family of calcium pumps. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14483–14489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIver MB, Tanelian DL. Structural and functional specialization of Aδ and C fiber free nerve endings innervating rabbit corneal epithelium. J Neurosci. 1993;13:4511–4524. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-10-04511.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice DM, Mishima S. Ocular pharmacokinetics. In: Sears ML, editor. Pharmacology of the Eye. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. New York: Springer; 1984. pp. 19–116. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer C, Quasthoff S, Grafe P. Confocal imaging reveals activity-dependent intracellular Ca2+ transients in nociceptive human C fibres. Pain. 1999;81:317–322. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KA, Cohen AS, Kao JP, Weinreich D. Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release mediates a slow post-spike hyperpolarization in rabbit vagal afferent neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:688–694. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller LJ, Pels L, Vrensen GF. Ultrastructural organisation of human corneal nerves. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:476–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita K, Akita T, Hachisuka J, Huang S, Ochi K, Kuba K. Functional coupling of Ca2+ channels to ryanodine receptors at presynaptic terminals. Amplification of exocytosis and plasticity. J Gen Physiol. 2000;115:519–532. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onodera K. Effect of caffeine on the neuromuscular junction of the frog, and its relation to external calcium concentration. Jpn J Physiol. 1973;23:587–597. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.23.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild JH, Clark JW, Hay M, Mendelowitz D, Andresen MC, Kunze DL. A- and C-type rat nodose sensory neurons: model interpretations of dynamic discharge characteristics. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:2338–2358. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.6.2338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishkin V, Potapenko E, Kostyuk E, Girnyk O, Voitenko N, Kostyuk P. Role of mitochondria in intracellular calcium signaling in primary and secondary sensory neurons of rats. Cell Calcium. 2002;32:121–130. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(02)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AB, Cunnane TC. Ryanodine-sensitive calcium stores involved in neurotransmitter release from sympathetic nerve terminals of the guinea-pig. J Physiol. 1996;497:657–664. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer SA, Miller RJ. Regulation of the intracellular free calcium concentration in single rat dorsal root ganglion neurons in vitro. J Physiol. 1990;425:85–115. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer SA, Perney TM, Miller RJ. Regulation of calcium homeostasis in sensory neurons by bradykinin. J Neurosci. 1988;11:4089–4097. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-11-04089.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer SA, Usachev YM, Pottorf WJ. Modulating Ca2+ clearance from neurons. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d1255–1279. doi: 10.2741/A838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usachev YM, DeMarco SJ, Campbell C, Strehler EE, Thayer SA. Bradykinin and ATP accelerates Ca2+ efflux from rat sensory neurons via protein kinase C and the plasma membrane Ca2+ pump isoform 4. Neuron. 2002;33:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00557-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdru P, De Greef C, Mertens L, Carmeliet E, Callewaert G. Na+-Ca2+ exchange in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:484–490. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.1.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A, Shmigol A. Calcium-induced calcium release in neurones. Cell Calcium. 1996;19:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(96)90009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wächtler J, Mayer C, Grafe P. Activity-dependent intracellular Ca2+ transients in unmyelinated nerve fibres of the isolated adult rat vagus nerve. Pflugers Arch. 1998;435:678–686. doi: 10.1007/s004240050569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinreich D, Wonderlin WF. Inhibition of calcium-dependent spike after-hyperpolarization increases excitability of rabbit visceral sensory neurones. J Physiol. 1987;394:415–427. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werth JL, Thayer SA. Mitochondria buffer physiological calcium loads in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 1994;14:348–356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00348.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitear EC. An electron microscope study of the cornea in mice, with special reference to the innervation. J Anat. 1960;94:387–409. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zander E, Weddell G. Observations of the innervation of the cornea. J Anat. 1951;85:68–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Typical corneal nerve terminals (CNTs) coursing through the corneal epithelial cell layer.

Supplemental Figure 1. Typical corneal nerve terminals (CNTs) coursing through the corneal epithelial cell layer. A, Typical CNT loaded with the Ca2+ indicator Oregon Green 488 BAPTA-1 dextran (10 kDa) 24 hr before imaging with a cooled CCD camera. Scale bar for A is equal to 10 μm. B, CNTs loaded with the fluorophore tetramethylrhodamine dextran (10,000 MW) 24 hr before imaging with confocal microscopy. Corneal epithelium in the same object plane as the CNT was imaged by detection of transmitted laser light (633 nm) by the confocal's transmission photomultiplier tube. Scale bar for B is equal to 20 μm.

Assessment of drug penetration into the corneal epithelium.

Supplemental Figure 2. Assessment of drug penetration into the corneal epithelium. To determine drug access to the corneal epithelium, wherein corneal nerve terminals reside, the epithelia in intact corneas were loaded biolistically with OGD-1 dextran (see Methods) and [Ca2+]i changes in epithelial cells were imaged as drugs that can alter Ca2+ homeostasis were bath-applied. Cells deep within the corneal epithelium (∼50 μm from the surface) were imaged.\ A. Bath application of 5 μm CPA (blue bar) elevated [Ca2+]i in epithelial cells in ∼60 s. B. [Ca2+]i in epithelial cells increased ∼120 s after 2 μm CCCP was bath-applied (green bar). C. Bath-applied KB-R7943 (5 ?M; red bar) evoked a rise in [Ca2+]i in epithelial cells in ∼70 s. Rises in epithelial [Ca2+]i tended to be oscillatory as can be seen from the rises in [Ca2+]i at the end of each trace.