Abstract

Transient changes in extracellular pH (pHo) occur in the retina and may have profound effects on neurotransmission and visual processing due to the pH sensitivity of ion channels. The present study characterized the effects of acidification on the activity of membrane ion channels in isolated horizontal cells (HCs) of the goldfish retina using whole-cell patch-clamp recording. Currents recorded from HCs were characterized by prominent inward rectification at potentials negative to −80 mV, a negative slope conductance between −70 and −40 mV, a sustained inward current, and outward rectification positive to 40 mV. Inward currents were identified as those of inward rectifier K+ (Kir) channels and Ca2+ channels by their sensitivity to 10 mm Cs+ or 20 μm Cd2+, respectively. Both of these currents were reduced when pHo decreased from 7.8 to 6.8. Glutamate (1 mm)-activated currents were also identified, as were hemichannel currents that were enhanced by removal of extracellular Ca2+ and application of 1 mm quinidine. Both glutamate-activated and hemichannel currents were suppressed by a similar reduction of pHo. When all of these H+-inhibited currents were blocked, a small, sustained inward current at −60 mV increased following a decrease in pHo from 7.8 to 6.8. In addition, slope conductance between −70 and −20 mV increased during this acidification. Suppression of this H+-activated current by removal of extracellular Na+, and an extrapolated Erev near ENa, indicated that this current was carried predominantly by Na+ ions.

In the central nervous system (CNS), changes in pH can produce significant modulation of neuronal excitability, membrane potential and synaptic transmission (Somjen & Tombaugh, 1998). Despite tight pH regulation, such modulation is produced through the effects of transient intracellular and extracellular pH change on the function of voltage- and ligand-gated membrane ion channels (Tombaugh & Somjen, 1998; Traynelis, 1998; Chesler, 2003).

The retina represents a convenient experimental preparation in the CNS with which to study the modulation of ion channels by H+. Many retinal synapses utilize graded changes in presynaptic membrane potential (instead of action potentials) to trigger neurotransmitter release, thereby leading to a high degree of sensitivity of retinal activity to extracellular pH (Barnes, 1998). The pH of the extracellular space in the retina changes depending on light stimulation (Borgula et al. 1989; Oakley & Wen, 1989; Yamamoto et al. 1992) and is controlled by a circadian clock (Dmitriev & Mangel, 2000, 2001). At resting potentials, synaptic terminals of light-sensitive photoreceptors are depolarized and release H+, with glutamate, into the synaptic cleft (DeVries, 2001). This acidification of cleft pH may lead to inhibition of H+-sensitive Ca2+ channels located on presynaptic photoreceptor terminals (Barnes & Bui, 1991; Barnes et al. 1993; DeVries, 2001) and the modulation of other ion channels located within the synapse. Horizontal cells (HCs) are postsynaptic neurons in the outer retina that project dendrites into the synaptic invagination of presynaptic photoreceptor terminals, and contribute to formation of the receptive field surround of the retina by sending inhibitory feedback signals back to cone photoreceptors during illumination (Baylor et al. 1971; Dowling, 1987). Horizontal cells express a wide variety of ion channels that are well characterized (Tachibana, 1983, 2985; Lasater, 1986; Shingai & Christensen, 1986; DeVries & Schwartz, 1992). The small extracellular volume of the synaptic space within the photoreceptor invagination (see Raviola & Gilula, 1975), and the close proximity of synaptic partners, may allow for pH-sensitive changes of ion channel activity by H+ uptake and release into the synaptic cleft. Indeed, it has been proposed that inhibitory feedback signals from HCs to presynaptic photoreceptors are mediated by H+ (Hirasawa & Kaneko, 2003; Vessey et al. 2005; Cadetti & Thoreson, 2006).

The present study characterized the H+ sensitivity of ion channels in isolated HCs of the retina. While several ion channel types were inhibited by acidification, a H+-induced conductance was described in these cells that appeared to be carried by Na+ ions.

Methods

Animals

Adult goldfish (Carassius auratus) 8–12 cm in length were obtained from the Aquatron Laboratory (Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada) and maintained in a 400 l aquarium at 12–14°C on a 12 h light–dark cycle. All procedures for animal care were carried out according to institutional guidelines, which adhere to those of the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC). Goldfish were dark-adapted overnight, or for a minimum of 1 h during the day, before removal of retinal tissue.

Isolated horizontal cell preparation

Goldfish were decapitated and pithed. Eyes were quickly removed and placed in ice-cold Ca2+-free Ringer solution containing the following (mm): 120 NaCl, 2.6 KCl, 1 NaHCO3, 0.5 NaH2PO4, 1 sodium pyruvate, 4 Hepes and 16 glucose at pH 7.4. The sclera and lens of the eye were first dissected away, allowing for removal of the retina from the eyecup. Whole retinas were placed in 100 U ml−1 hyaluronidase (Cat. No. H-3506, Sigma, Mississauga, ON, Canada) in L-15 solution for 20 min at room temperature to remove excess vitreous material. L-15 solution contained 30% Ca2+-free Ringer solution and 70% L-15 (Sigma) (Connaughton & Dowling, 1998). After rinsing 3 times in fresh L-15 solution, retinas were placed in L-15 solution containing 7 U ml−1 papain (Cat. no. 3126, Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ, USA) and 2.5 mml-cysteine (Sigma) for 40 min at room temperature. Tissue was rinsed again and placed in L-15 solution at ∼15°C until needed. HCs were isolated by triturating a small piece of retinal tissue in L-15 solution with a Pasteur pipette, and placing ∼100 μl of cell suspension in a 35 mm plastic Petri dish (Nunclon, Nunc A/S, Roskilde, Denmark). Cells were allowed to settle for 15 min. HCs were visualized using an inverted microscope (Diaphot, Nikon, Japan).

Patch-clamp recording

Voltage-clamp recordings were performed on HCs in whole-cell configuration. Patch electrodes were fabricated from capillary glass (Cat. no. 2502, Chase Scientific Glass, Inc., Rockwood, TN, USA) and pulled on a vertical pipette puller (Model 730, David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA). Electrodes had a tip resistance of 5–8 MΩ when filled with intracellular recording solution containing (mm): 120 KCl, 10 NaCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 2 Mg-ATP, 5 EGTA, 10 Hepes, pH adjusted to 7.4 with KOH. See Table 1 for extracellular recording solutions (pH adjusted to 7.8 with NaOH in normal solution). Liquid junction potentials (VL) ranging from −1.0 mV to 4.2 mV were calculated using pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and subtracted from pipette potentials (Vp) to determine actual membrane potential (Vm), according to the equation: Vm=Vp−VL. All current–voltage (I–V) curves were corrected for VL.

Table 1.

Extracellular recording solutions

| Solution and chemical concentrations (mm) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 51 | 6 |

| NaCl | 120 | 110 | 90 | 80 | 111.5 | — |

| KCl | 5 | 5 | 35 | 5 | 5 | — |

| CaCl2 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | — | 1 | — |

| MgCl2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4.5 | 2 | 2 |

| Buffer2 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Glucose | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| CsCl | — | 10 | — | 10 | 10 | — |

| CdCl2 | — | — | — | — | 0.02 | — |

| TEA | — | — | — | 20 | — | 20 |

| 4-AP | — | — | — | 10 | — | 10 |

| NMDG | — | — | — | — | — | 97.5 |

pH 8.8, 7.8, 6.8 or 5.8 with NaOH.

Trizma for pH 8.8, Hepes for pH 7.8 and 6.8, Mes for pH 5.8. TEA, t Tetraethylammonium chloride. 4-AP, 4-aminopyridine. NMDG, N-methyl-d-glucamine.

Voltage-clamp protocols were performed using an Axopatch-1D amplifier (Axon Instruments) and pCLAMP 7 software. Recorded signals were digitally converted using a DigiData 1200 interface (Axon Instruments) and stored on a PC computer. Cells were held at −60 mV and currents were evoked by changing Vm to a series of test potentials (as specified in figures and legends). This was performed either by a voltage-step protocol, in which Vm was changed to potentials for 100 ms at a frequency of 5 Hz, or by a voltage-ramp protocol, in which the membrane potential was continuously changed (0.18–0.22 mV ms−1) over a period of 1 s. Signals were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at a rate of 10 kHz. Membrane capacitance (Cm) was measured using pCLAMP software or the Axopatch-1D amplifier. In some experiments, the inverse slope of the I–V relationship was used to calculate input resistance (Rin) according to Ohm's law: Rin=ΔVΔI−1. All data were analysed using pCLAMP software, and figures were arranged using Origin 7.0 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA) and Corel Draw 9 (Corel Corp., Ottawa, ON, Canada).

Experimental procedures and solutions

Petri dishes were fitted with a superfusion chamber formed from Sylgard (Dow Corning Corp., Midland, MI, USA) to allow the continuous exchange of extracellular recording solutions in a small bath volume (200–300 μl) by gravity inflow (∼2 ml min−1) and vacuum aspiration. Solutions were superfused into the recording chamber using a four-reservoir system and chamber manifold (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA). Changes in ion channel current were measured 2–3 min following application of drugs or solutions of different pH to allow for adequate diffusion in the recording medium. Patch-clamp experiments were performed to demonstrate the H+ sensitivity of several types of ion channels by showing a change in ion channel current during a decrease in the pH of the extracellular recording solution. Table 1 summarizes extracellular solutions used in patch-clamp experiments. Recordings were initially obtained in normal extracellular solution (i.e. solution 1, Table 1). The divalent cation, 20 μm Cd2+, was used to inhibit voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (Takahashi et al. 1993), and inward rectifier K+ (Kir) channels were inhibited by 10 mm Cs+ (Tachibana, 1983). Equimolar substitution of intracellular K+ with CsCl in the pipette solution was also used to block Kir channels in HCs (Lasater, 1986). 4-Aminopyridine (10 mm, 4-AP; Sigma) was used to inhibit transient outward K+ currents (Tachibana, 1983). In experiments designed to examine hemichannel currents (Iγ), solutions were used that were high in Mg2+ but free of Ca2+ (which inhibits Iγ; DeVries & Schwartz, 1992). Quinidine, which stimulates Iγ (Malchow et al. 1994), was used at a concentration of 1 mm. Experiments designed to test the pH sensitivity of ion channel currents utilized solutions set to different pH values (Table 1). Solutions with a pH between 6.5 and 7.8 were buffered with Hepes, while solutions with a pH of 5.8 or 8.8 were buffered with Mes or Trizma (Sigma), respectively. Other recording conditions, or drugs, were used to further characterize H+-sensitive currents. Equimolar substitution of extracellular ions with N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG) was performed to determine any dependence of H+-sensitive current on these ions, such as Na+. Amiloride (100 μm, Sigma) and Zn2+ (100 μm) are inhibitors of ion channels of the epithelial Na+ channel/degenerin (ENaC/DEG) family (de Weille et al. 1998; Baron et al. 2002; Kellenberger & Schild, 2002) and were used to test for sensitivity of the H+-sensitive current. Amiloride is also a known inhibitor of the Na+–H+ exchanger (Bevensee & Boron, 1998). Furthermore, Zn2+ is an inhibitor of voltage-dependent H+-selective channels in several cell types (DeCoursey, 2003) and was used to determine if these channels were present in HCs. Bafilomycin A1 (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA, USA) is a potent and specific inhibitor of H+-permeable V-type ATPases at a concentration of 0.1 μm (Bowman et al. 1998) and was used in the present study at 1 μm. Glutamate (Sigma) was used at 100 μm and 1 mm concentrations to activate glutamate-sensitive currents.

Statistical analysis

All data in text and figures are presented as means ±s.e.m. Changes in membrane current and conductance were compared using Student's t test, Student's paired t test, or analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical analyses were performed using Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and Statistix 2.0 (Analytical Software, Tallahassee, FL, USA).

Results

Isolated horizontal cell properties

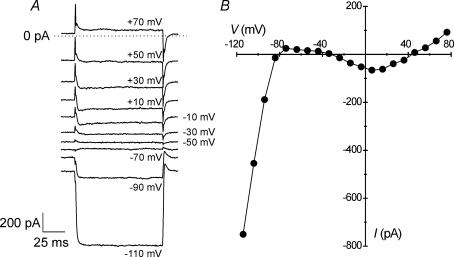

Horizontal cells (HCs) of the goldfish retina were identified in vitro by the presence of several extensive dendritic processes and a large flat cell body. The present experiments examined all subtypes of HCs collectively. Mean membrane capacitance (Cm) of HCs was 27 ± 2 pF (n = 40), as determined from whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings. In addition, input resistance (Rin), measured from the inverse slope of current–voltage (I–V) curves between −70 and −40 mV, was −5 ± 0.4 GΩ (n = 40), reflecting a negative slope conductance of −285 ± 26 pS within the physiological range. During voltage-clamp recording, isolated HCs displayed a variety of membrane currents evoked by hyperpolarizing or depolarizing protocols from a holding potential of −60 mV (Fig. 1A). An I–V curve (Fig. 1B) was generated from these currents that conformed to the previously described ‘N-shaped’ curve (see also Tachibana, 1983; Shingai & Christensen, 1986). Currents recorded from HCs were characterized by prominent inward rectification at potentials negative to −80 mV, a negative slope conductance between −70 and −40 mV (as indicated above), a sustained inward current that was activated near −40 mV and peaked near 10 mV, and modest outward rectification positive to 40 mV (Fig. 1A and B).

Figure 1. Membrane currents in isolated horizontal cells.

Recordings performed in solution 1 (see Table 1). A, whole-cell voltage-clamp recording from a horizontal cell shows currents evoked by hyperpolarizing or depolarizing voltage steps (indicated in figure) from a holding potential of −60 mV. B, current–voltage (I–V) relationship of currents recorded in A. The characteristic ‘N’ shape of the I–V curve illustrates a prominent inwardly rectifying current carried by K+ at potentials negative to −80 mV, a negative slope conductance between −70 and −40 mV, a sustained inward current carried by Ca2+, and outward rectification.

Proton-inhibited currents

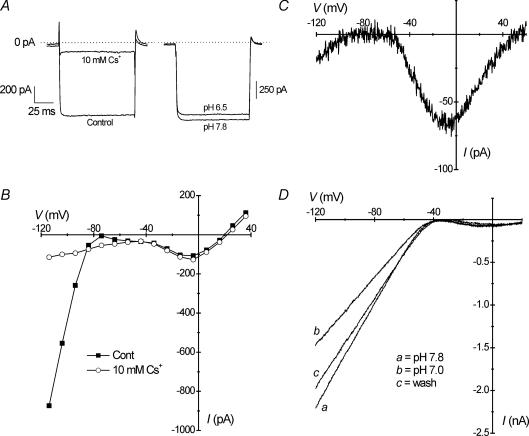

Isolated HCs expressed several types of ion channel conductances that were sensitive to extracellular pH. Inward currents negative to −80 mV were identified as those of inwardly rectifying K+ (Kir) channels based on their inhibition by Cs+ (Tachibana, 1983). Superfusion of the recording bath with solution containing 10 mm Cs+ resulted in near-complete inhibition of inward K+ currents (IKir) from −599 ± 72 pA to −79 ± 11 pA (P < 0.001; Student's paired t test; n = 14), as demonstrated during voltage steps from −60 mV to −110 mV (Fig. 2A, left trace) and the plot of the I–V curves before and after Cs+ application (Fig. 2B). Only a linear current with a positive slope conductance remained at potentials negative to −40 mV. In addition, substitution of equimolar KCl with CsCl in the pipette solution had the same effect of inhibiting IKir (Fig. 2C). The H+ sensitivity of inward IKir was demonstrated in goldfish HCs by reducing the pH of the recording medium from 7.8 to 6.5. During voltage steps from a holding potential of −60 mV to −110 mV, IKir was reversibly reduced (Fig. 2A, right trace; see also ramp recordings in Fig. 3B). In four cells, mean IKir was significantly reduced from −332 ± 77 pA to −284 ± 66 pA during acidification from a pH of 7.8 to 6.8 (P < 0.05; Student's paired t test). In ramp recordings, the sensitivity of Kir to changes in pH from 7.8 to 7.0 was demonstrated in a more dramatic experiment with high K+ solutions (Fig. 2D) and shows reversible inhibition of inward IKir negative to the equilibrium potential for K+ (EK=−31 mV).

Figure 2. Horizontal cells express H+-sensitive inwardly rectifying K+ channels.

A (left trace), voltage-clamp recording from a cell shows inhibition of inwardly rectifying K+ current (IKir) by the K+ channel blocker, Cs+. The cell was stepped from −60 to −110 mV in both control and in the presence of 10 mm Cs+ (solution 2; Table 1). In another cell (right trace) following the same protocol, IKir was inhibited at −110 mV by reduction of extracellular pH from 7.8 to 6.5. B, current–voltage (I–V) relationship of the cell shown in A (left) indicates inhibition of IKir negative to −80 mV by Cs+ (○) compared with control (▪). C, ramp recording in another cell demonstrates that equimolar substitution of KCl with CsCl in the pipette solution inhibited IKir, as in B. D, in recordings performed in high K+ (solution 3; Table 1), a more dramatic inhibition of IKir was observed during a change in bath pH from 7.8 (a) to 7.0 (b) and during recovery (c).

Figure 3. Ca2+ channels are inhibited by extracellular H+.

A, voltage-clamp recording of a cell stepped from −60 to 0 mV demonstrates reversible inhibition of Ca2+ current (ICa) by acidification of the recording bath from a pH of 7.8 to 6.5. B, ramp recording shows reversible changes in the current–voltage (I–V) relationship during a brief decrease of extracellular pH from 7.8 (a) to 7.0 (b) and during recovery (c, inset). ICa was inhibited between −40 mV and 10 mV. Note also an apparent positive shift in activation potential of ICa during acidification. C, ramp recording from a horizontal cell demonstrates reduction of ICa by the Ca2+ channel blocker, 20 μm Cd2+, without a shift in activation.

Sustained inward currents in HCs that activated near −40 mV (Fig. 1A and B) were inhibited by Cd2+, and were characteristic of those carried by Ca2+ ions though high voltage-activated (HVA) or L-type Ca2+ channels (Takahashi et al. 1993). Ca2+ currents (ICa) in goldfish HCs were sensitive to changes in extracellular pH. In a cell stepped from −60 mV to 0 mV, ICa was reversibly suppressed when bath pH was reduced from 7.8 to 6.5 (Fig. 3A). In several cells, mean current at 0 mV was significantly reduced from −76 ± 11 to −44 ± 7 pA during acidification from a pH of 7.8 to 6.8 (P < 0.001; Student's paired t test; n = 7). In addition, changes in the I–V relationship indicated that extracellular acidification reduced ICa across a range of potentials, and showed a slight shift in activation potential to more positive values along the voltage axis (Fig. 3B). By contrast, application of 20 μm Cd2+, which also reduced ICa at potentials positive to −40 mV, did not induce a shift in activation potential (Fig. 3C). Mean ICa at 0 mV was significantly reduced by Cd2+ from −67 ± 7 pA to 16 ± 2 pA (P < 0.001; Student's paired t test; n = 15).

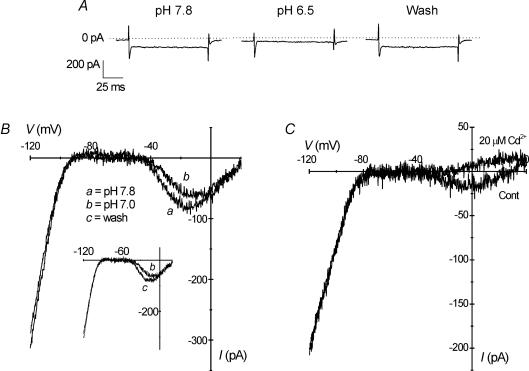

Horizontal cell membrane currents have been shown to be affected by the application of the neurotransmitter, glutamate (Tachibana, 1985). Glutamate was applied to isolated HCs at concentrations of 100 μm and 1 mm, and changes in inward and outward currents induced by glutamate (Iglu) are shown in Fig. 4. Application of both glutamate concentrations had similar effects on HCs, such as increased outward current at positive potentials, and increased inward current and slope conductance between −80 and −40 mV. However, glutamate had reduced effects at more negative potentials (Fig. 4A and D). As also demonstrated in Fig. 4C, 1 mm glutamate increased mean inward current at −60 mV from −8 ± 7 to −93 ± 20 pA, and outward current at 60 mV from 74 ± 20 to 330 ± 49 pA (P < 0.01; Student's paired t test; n = 5). Isolation of the glutamate-induced current by difference current subtraction indicated an inward current increase that peaked near −80 mV (Fig. 4B). This was probably due to the activating effect of glutamate on Iglu within the physiological range (−70 to −20 mV) and suppression of IKir negative to EK (−80 mV). In addition, a non-linearity in the I–V curve of the difference current between −40 and 40 mV indicated a decrease in ICa with glutamate application (Fig. 4B) that was abolished in Ca2+-free medium (Fig. 4B, inset). Reduction of IKir and ICa by glutamate are well known and have previously been reported (Tachibana, 1985; Kaneko & Tachibana, 1985; Dixon et al. 1993). Moreover, Iglu was shown to be inhibited by acidification of the recording medium from a pH of 7.8 to 5.5, as shown in step depolarizations and an I–V curve (Fig. 4C and D). Mean Iglu at −60 and 60 mV was reduced by 76 and 65%, respectively, upon extracellular acidification.

Figure 4. Glutamate-activated currents in horizontal cells are inhibited by extracellular H+.

A, ramp recordings show changes in the current–voltage (I–V) relationship following application of 100 μm glutamate compared with control. In addition to changes in outward current, glutamate induced an increase in inward current and slope conductance within the voltage range of −80 to −40 mV. B, difference current of traces in A (i.e. glutamate minus control) revealed that glutamate induced an inward current that peaked near −80 mV, and decreased inward rectifier K+ current (IKir) below −80 mV. In addition, the positive ‘increase’ in difference current between −40 and 40 mV indicated inhibition of Ca2+ current (ICa). In a similar experiment in which extracellular Ca2+ was removed (inset), this change in the I–V was not observed (arrow). C, in a cell stepped from −60 mV to a variety of test potential (indicated in figure), inward current at −60 mV and outward current at 60 mV increased in the presence of 1 mm glutamate, when compared with control. During extracellular acidification to pH 5.5, these currents were suppressed. D, I–V relationship of recordings from the cell in C. The effects of 1 mm glutamate were similar to those shown in A. As in C, following acidification of the recording medium to a pH of 5.5, these glutamate-activated currents were attenuated.

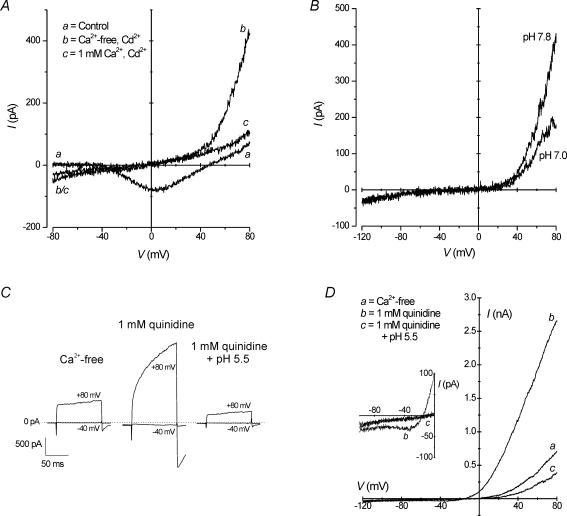

Horizontal cells have previously been shown to express hemichannel currents (Iγ) that are activated by reduced extracellular Ca2+ (DeVries & Schwartz, 1992). Activation of Iγ in goldfish HCs, in the present study, was demonstrated by removal of extracellular Ca2+ from the recording solution. Under such conditions, outward current increased at potentials positive to 40 mV and showed prominent rectification (Fig. 5A). In seven cells, mean outward current significantly increased from 60 ± 9 pA to 549 ± 84 pA at 80 mV when extracellular Ca2+ was removed, compared with control (P < 0.001; Student's paired t test). These experiments also showed that replacement of 1 mm Ca2+ was sufficient to suppress outward Iγ at these potentials (Fig. 5A). Note, in the above experiment 20 μm Cd2+ was present in the extracellular solution during Ca2+ reduction, and prevented recovery of ICa. Subsequent experiments designed to further show the pH sensitivity of Iγ were performed in Ca2+-free recording solution (solution 4 in Table 1). As shown in Fig. 5B, in Ca2+-free recording solution, Iγ was inhibited by a reduction in extracellular pH from 7.8 to 7. In several such experiments, mean outward current was significantly reduced from 549 ± 85 to 367 ± 54 pA at 80 mV during acidification (P < 0.01; Student's paired t test; n = 7). In addition, quinidine has been shown to activate Iγ in HCs (Malchow et al. 1994). Application of 1 mm quinidine to the recording bath stimulated a prominent, slowly activating outward current at positive potentials, and a small but detectable inward current at negative potentials. These Iγ currents were demonstrated during step depolarizations from −60 mV to −40 and 80 mV (Fig. 5C). In ramp recordings, the I–V relationship of quinidine-activated Iγ demonstrated outward rectification at depolarized potentials, and a region of negative resistance between −60 mV and −40 mV (Fig. 5D). In two cells, quinidine increased outward current from 821 ± 186 to 2952 ± 421 pA at 80 mV in Ca2+-free solution, and induced inward current from −9 ± 1 to −39 ± 9 pA at −40 mV. In addition, quinidine had similar effects in the presence of 2.5 mm Ca2+. Iγ increased from 105 ± 20 to 353 ± 42 pA at 80 mV, and from −20 ± 2 to −30 ± 4 pA at −60 mV, respectively. Moreover, quinidine-activated Iγ was determined to be pH sensitive. In cells exposed to 1 mm quinidine, change of extracellular pH from 7.8 to 5.5 suppressed outward Iγ from 2952 ± 421 to 418 ± 71 pA at 80 mV, and inward Iγ was reduced from −39 ± 9 to −8 ± 1 pA at −40 mV. This is demonstrated by a reduction of inward and outward current in Fig. 5C and D.

Figure 5. Hemichannel currents in horizontal cells are inhibited by extracellular H+.

A, hemichannel currents (Iγ) are suppressed by Ca2+. Ramp recordings show the current–voltage (I–V) relationship in a horizontal cell (HC) during changes in extracellular Ca2+. Compared with control (2.5 mm Ca2+; a), removal of Ca2+ activated outward Iγ at potentials positive to 40 mV (b). Addition of 1 mm Ca2+ back to the recording medium was sufficient to suppress Iγ(c). Note, in b and c 20 μm Cd2+, 10 mm Cs+, 20 mm TEA and 10 mm 4-AP were also present in the bath solution. B, Iγ is reduced by extracellular acidification. Recordings performed in Ca2+-free solution containing 10 mm Cs+, 20 mm TEA and 10 mm 4-AP. Acidification of the recording bath from a pH of 7.8 to 7.0 inhibited outward Iγ at potentials positive to 40 mV. C, recordings performed in solution 4 (see Table 1). In an HC bathed in Ca2+-free extracellular solution and stepped from −60 mV to test potentials indicated in the figure, some outward Iγ was recorded (left traces) as shown in A. The application of 1 mm quinidine further induced a small, but detectable, inward current at −40 mV, and a large, slowly activating outward current at 80 mV (middle traces). Both these inward and outward currents were inhibited by extracellular acidification from pH 7.8 to 5.5 (right traces). D, ramp recordings in another cell show changes in the I–V relationship during inhibition of quinidine-activated inward (see expanded scale in inset) and outward Iγ by acidification to pH 5.5.

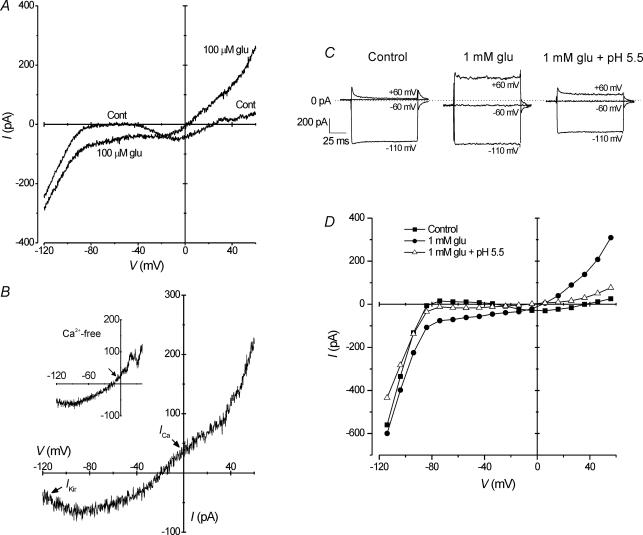

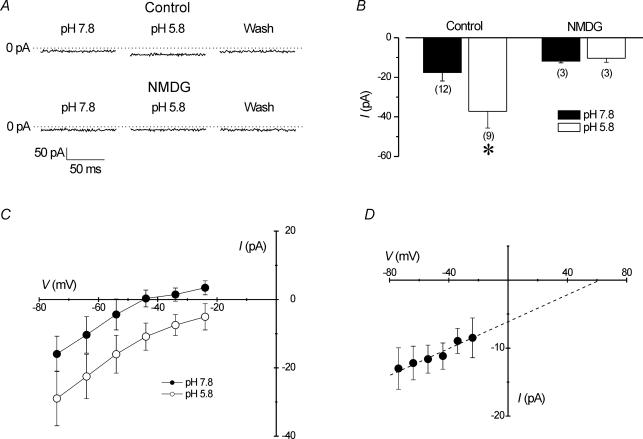

Proton-induced inward current

When H+-inhibited membrane currents described in the preceding section were suppressed (solution 5 in Table 1), a small, sustained H+-activated inward current was revealed during bath acidification (Fig. 6A; upper traces). In a population of cells, the increase in inward current from −18 ± 4 to −37 ± 8 pA was shown to be significant during acidification (Fig. 6B; P < 0.05, Student's t test). A change in membrane current across a range of potentials following extracellular acidification is demonstrated in the I–V relationship in Fig. 6C. As the pH of the recording bath was reduced from 7.8 to 5.8, inward current progressively increased as membrane potentials became more negative. Mean slope conductance calculated within the physiological range between −70 and −20 mV from several cells revealed a significant increase from 387 ± 87 to 478 ± 95 pS during a change of pH from 7.8 to 5.8 (P < 0.05; Student's paired t test; n = 6). It is worth noting that although the reversal potential (Erev) of the I–V relationship appeared to shift slightly during acidification by 2 pH units (Fig. 6C), this shift is not indicative of the presence of H+-selective ion channels, which are characterized by Erev shifts of 40–50 mV per pH unit during acidification (DeCoursey, 2003).

Figure 6. Extracellular H+ induces a Na+-selective inward current.

Recordings performed with solution 5 (see Table 1). A (upper traces), extracellular acidification increased inward current. Inward current (at −60 mV) increased when bath pH was changed from 7.8 to 5.8. Complete recovery was observed after wash. Lower traces, following replacement of extracellular ions with equimolar NMDG+ (solution 6; Table 1), extracellular acidification to pH 5.8 failed to produce a change in current at holding potential. B, in a population of cells, decreasing extracellular pH from 7.8 (filled bars) to 5.8 (open bars) under control conditions (i.e. extracellular Na+, K+ and Ca2+) significantly increased inward current (P < 0.05; Student's t test), but in NMDG solutions, no effect was observed (P > 0.05; Student's t test). Sample sizes are indicated in the figure. C, mean (±s.e.m.) currents from 6 cells showing the current–voltage relationships (I–V) at pH 7.8 and pH 5.8. D, mean (±s.e.m.) change in the I–V relationship within the physiological range (−70 to −20 mV) during activation of inward current by extracellular acidification from a pH of 7.8 to 5.8. Data points were derived by subtracting currents at pH 7.8 from those at pH 5.8 for each cell and represent the mean difference current from 6 cells. The I–V relationship of the difference current has a slope conductance of about 90 pS. Dashed line represents a linear trend of the data extrapolated to intersect with the voltage axis at an Erev of ∼60 mV. Confidence limits (95%) of the approximated value of Erev were 41 and 80 mV, as predicted following linear regression (P = 0.15; r2= 0.06).

In experiments in which extracellular cations, such as Na+, K+ and Ca2+, were removed from the extracellular medium and replaced with impermeable NMDG+, the pH-dependent increase in inward current was abolished during acidification to pH 5.8 (Fig. 6A; lower traces). In three cells, mean inward current did not significantly change upon extracellular acidification (−12 ± 1 to −11 ± 2 pA) when extracellular cations were replaced with NMDG (Fig. 6B). In addition, mean conductance was unaffected by a decrease in pH from 7.8 to 5.8 in the presence of NMDG. Moreover, additional experiments were performed (not shown) in which only Ca2+ (n = 9) or K+ (n = 3) was removed from the extracellular solution, and during acidification the increase in inward current persisted. These data suggest that the H+-induced inward current is carried predominantly by Na+. We also show that the H+-induced inward current may be Na+ selective (Fig. 6D). In six cells, the difference of inward current activated at a pH of 5.8 minus inward current at a pH of 7.8 (see data in Fig. 6C) for each cell was measured between −70 mV and −20 mV. The I–V relationship of these mean difference currents is plotted in Fig. 6D, and corresponds to a conductance increase of 90 pS. A linear fit of these data points reveals a trend in the I–V relationship that extrapolates to an Erev of ∼60 mV (with 95% confidence limits of 41 and 80 mV), near the calculated equilibrium potential for Na+ (ENa) of 62.6 mV. Although an analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the data shown in Fig. 6D indicated that the linear fit of the difference current is only a trend and is not statistically significant, a comparison of means with the paired t test showed that inward current at −20 mV was significantly smaller than current recorded at −70 mV.

The above characteristics suggest that this H+-activated Na+ current (INa(H)) may be similar to currents carried by ion channels of the ENaC/DEG family (Kellenberger & Schild, 2002; Wemmie et al. 2006). We therefore tested the effects of two ENaC/DEG inhibitors, amiloride and Zn2+, for their effects on INa(H) activation. Exposure of 100 μm amiloride or 100 μm Zn2+ alone had no effects on membrane currents at −60 mV in isolated HCs under control conditions (not shown; see also Vessey et al. 2005). Pre-application of amiloride or Zn2+ at these same concentrations failed to inhibit activation of INa(H) following acidification of extracellular pH (Fig. 7A and B). In several cells, mean INa(H) increased from −10 ± 4 to −29 ± 8 pA in amiloride (n = 3), and from −5 ± 2 to −14 ± 3 pA in Zn2+ (n = 5) (Fig. 7C; P < 0.01; Student's paired t test). These increases in inward current were not significantly different from the increase induced by H+ under control conditions (i.e. data from Fig. 6B; ANOVA, P > 0.05). To further implicate the H+-induced inward current as one carried by Na+, additional experiments were performed to rule out potential contamination by H+ inhibition of residual IKir at potentials positive to EK. As shown in Fig. 2C, substitution of KCl with equimolar CsCl in the pipette solution inhibited IKir. When intracellular Cs+ was used to block outward IKir within the physiological range, an increase in inward current was still recorded at −60 mV during a reduction in extracellular pH from 7.8 to 5.8, suggesting that the H+-induced inward current is not due to a pH-sensitive decrease in IKir at potentials positive to EK. In addition, experiments were performed to determine the potential role of a H+ current, as may be supported by conductance pathways such as the electrogenic V-type ATPase (Bevensee & Boron, 1998) and H+-selective ion channels (DeCoursey, 2003). In the presence of 1 μm bafilomycin, a potent and specific inhibitor of V-type ATPases (Bowman et al. 1998), extracellular acidification increased inward current at −60 mV (Fig. 7D). In several cells, mean current increased from −3 ± 3 to −14 ± 4 pA in the presence of bafilomycin (Fig. 7E; P < 0.01; Student's paired t test; n = 5). Furthermore, since the H+-activated current was not inhibited by 100 μm Zn2+ (Fig. 7B and C), an inhibitor of H+-selective ion channels (DeCoursey, 2003), these results suggest that H+-selective channels are not involved in the H+-induced increase in inward current in HCs.

Figure 7. H+-activated inward current is not sensitive to amiloride, Zn2+ or bafilomycin.

A, inward current at −60 mV was increased when bath pH was reduced from 7.8 to 6.5 in the presence of 100 μm amiloride, an inhibitor of ENaC/DEG ion channels and the Na+–H+ exchanger. B, inward current at −60 mV was increased when bath pH was reduced from 7.8 to 5.8 in the presence of 100 μm Zn2+, an inhibitor of ENaC/DEG and H+-selective ion channels. C, in a population of cells, decreasing extracellular pH from 7.8 (filled bars) to more acidic pH values (open bars) in the presence of 100 μm amiloride (n = 3), or 100 μm Zn2+ (n = 5) significantly increased inward current (P < 0.05; Student's paired t test). D, H+-induced inward current is insensitive to the V-type ATPase blocker, bafilomycin. Recordings performed in solution 5 (see Table 1). Inward current at −60 mV was increased when bath pH was reduced from 7.8 to 5.8 in the presence of 1 μm bafilomycin A1. E, in several cells (n = 5), decreasing extracellular pH from 7.8 (filled bar) to 5.8 (open bar) in the presence of 1 μm bafilomycin significantly increased inward current (P < 0.01; Student's paired t test).

Discussion

This study has described the modulation of a wide variety of ion channels by extracellular H+ in isolated horizontal cells (HCs) of the goldfish retina. We have demonstrated the H+ inhibition of membrane currents through inward rectifier K+ channels (IKir), Ca2+ channels (ICa), ionotropic glutamate receptors (Iglu), and hemichannels (Iγ). Additionally, the present work has characterized a previously undescribed current in HCs that is carried by Na+ ions and is activated by extracellular acidification.

Inhibition of ion channels by extracellular protons

Modulation of ion channels by changes in intracellular or extracellular pH in the central nervous system (CNS) has been described, and plays a role in the regulation of important physiological processes (Tombaugh & Somjen, 1998; Traynelis, 1998). Ion channels are modified by H+ at multiple sites. H+ may modulate ion channel conductance by neutralizing negative charges on proteins within the channel or near the mouth of the pore, or by neutralizing fixed negative charges on the surface of the plasma membrane (‘surface charge screening effect’) and shifting the activation potential of the channel (Tombaugh & Somjen, 1998). In the retina, activity-dependent changes in extracellular pH occur and may influence synaptic output from photoreceptors and the processing of visual information (Barnes, 1998; Hirasawa & Kaneko, 2003; Vessey et al. 2005). H+ ions are released into the synaptic cleft from photoreceptor terminals of the outer retina during normal activity, such as during the release of the neurotransmitter glutamate (DeVries, 2001), and from HCs during regulation of intracellular pH (Haugh-Scheidt & Ripps, 1998).

Kir channel inhibition by intracellular and extracellular acidification has previously been reported in a variety of preparations, such as myocytes, oocytes, and central neurons (Tombaugh & Somjen, 1998), and may indicate the presence of two distinct pH sensors (e.g. Sabirov et al. 1997; Zhu et al. 1999). In HCs of the catfish retina, intracellular acidification was shown to have only minor effects on IKir, compared with the enhancing effects of intracellular alkalinization (Takahashi & Copenhagen, 1995). In the present study, we demonstrate that extracellular acidification had clear inhibitory effects on IKir in high K+ solution, and confirm that under physiological K+ concentrations these effects may be diminished. However, given the demonstration of extracellular and intracellular H+-sensitive sites in Kir channels (Sabirov et al. 1997; Zhu et al. 1999), the present results suggest that IKir in HCs may be directly sensitive to extracellular pH change. We also showed a suppression of ICa and an apparent shift in Ca2+ channel activation potential with a reduction in extracellular pH. Inhibition of Ca2+ channels in the retina has been shown to occur in cone photoreceptors via an extracellular surface charge screening effect (Barnes & Bui, 1991), and in HCs of the catfish retina by intracellular acidification, such as during glutamatergic neurotransmission (Dixon et al. 1993; Takahashi et al. 1993). The present study has shown that ICa inhibition in goldfish HCs occurred during glutamate application, and also by extracellular acidification. Note that, in the latter case, the shift in activation potential of Ca2+ channels to more positive voltages is indicative of a surface charge screening effect of extracellular H+, which was not observed during glutamate application.

Horizontal cells of the retina express AMPA-type ionotropic glutamate receptors (Yang, 2004), and activation by glutamate leads to multiple changes in membrane conductance. These include inhibition of Kir channels, activation of a non-selective cation current, suppression of Ca2+ channels, and enhanced outward rectification (Kaneko & Tachibana, 1985; Tachibana, 1985; Dixon et al. 1993). We verify modulation of the same inward and outward currents by application of glutamate in isolated goldfish HCs, and have further shown reversal of the effect of glutamate by a decrease in extracellular pH. Thus, induction of Iglu via AMPA-type receptors, which have been localized to goldfish and carp HCs (Klooster et al. 2001; Schultz et al. 2001; Yang, 2004), appears to be dependent on extracellular pH, as has also been reported for NMDA receptors in catfish HCs (Wu & Christensen, 1996).

Gap junction channels (composed of two hemichannels) provide a direct pathway for electrical and metabolic signalling between coupled cells. In the retina, gap junctions occur in HCs where they allow for intercellular communication and increase the size of the receptive field. It is widely accepted that gap junctional coupling, and conductance, in most preparations is reduced by a decrease in intracellular pH, and H+ binding appears to occur at the cytoplasmic side of the hemichannel (Peracchia, 2004; Bukauskas & Verselis, 2004). In HCs isolated from catfish retina, gap junctional conductance between isolated cell pairs, and hemichannel current in solitary HCs, were decreased following intracellular acidification (DeVries & Schwartz, 1989, 1992). However, extracellular acidification reduced dye coupling in HCs of the rat retina (Hampson et al. 1994) and gap junctional conductance in progenitor cells of the goldfish retina (Tamalu et al. 2001). The present study reports activation of a large outwardly rectifying hemichannel current, and a small inward hemichannel current, by removal of extracellular Ca2+ or application of quinidine, as previously described in other fish species (DeVries & Schwartz, 1992; Malchow et al. 1994), and that this conductance is reduced by extracellular acidification. It is possible, however, that inhibition of Iγ in goldfish, following a decrease in extracellular pH, may have occurred via a subsequent decrease in intracellular pH.

Activation of an inward Na+ current by protons

When the H+-inhibited conductances described in the previous section were suppressed, a reduction of extracellular pH activated an inward current in HCs within the physiological range of −70 to −20 mV. This H+-activated current appeared not to be the result of modulation of a H+ current through potential H+ conducting pathways, such as the electrogenic V-type ATPase, H+-selective ion channels, or Na+–H+ exchange as evidenced by its resistance to bafilomycin, Zn2+, and amiloride, respectively (Bowman et al. 1998; DeCoursey, 2003). Moreover, removal of extracellular cations, especially Na+, dramatically inhibited the current and conductance increase induced by extracellular acidification, suggesting that the H+-activated current may be carried predominantly by Na+ ions. We also showed that extrapolation of the current–voltage relationship of the H+-activated current indicates an Erev near the equilibrium potential for Na+, suggesting that this current is highly selective for Na+ ions. These results lead us to conclude that isolated HCs from the goldfish retina express an inward Na+ current (INa(H)) that is activated during extracellular acidification, and is detectable during suppression of H+-inhibited membrane currents.

While most ion channels in the CNS display suppression by H+ (Tombaugh & Somjen, 1998), some channels of the DEG/ENaC family are activated by extracellular acidification. Acid-sensitive ion channel (ASIC) currents, for example, are depolarizing and carried predominantly by Na+ ions (Kellenberger & Schild, 2002; Wemmie et al. 2006). Several ASIC subunits have been found in the retina, including the localization of ASIC1a to HC dendrites and cell bodies (Brockway et al. 2002; Ettaiche et al. 2004, 2006; Lilley et al. 2004). Given the functional characteristics of ASICs, and their prevalence in the retina, it is reasonable to propose that INa(H) in goldfish HCs may reflect the presence of ASICs in these cells. However, the insensitivity of INa(H) to amiloride and Zn2+, which block ASIC currents (de Weille et al. 1998; Baron et al. 2002; Kellenberger & Schild, 2002) argues against this point. Studies designed to investigate the pharmacological properties of INa(H) will be necessary to further characterize this current.

Physiological significance

This study has described a number of pH-sensitive ion channels in HCs that each represents a potential site of H+ modulation at the photoreceptor–HC synapse in the outer retina. Therefore, extracellular acidification may have significant effects on HC activity. Specifically, inhibitory effects on Kir channels and AMPA receptors would lead to changes in membrane potential during bright illumination or in darkness, respectively. Neurotransmitter release from HCs, if dependent on voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, would also be reduced under acidic conditions. Since coupling and hemichannel conductance in HCs via gap junctions is pH dependent, acidification would promote HC uncoupling and reduce the size of the receptive field. Activation of depolarizing Na+ currents by acid could also lead to modulation of membrane potential. While the acid-induced currents described in the present study were small at physiological pH values, they were recorded within the operating range of HCs (−70 to −20 mV), where a high input resistance is observed. These currents therefore may influence HC activity under specific conditions of high acidity in the retina, although the effects of acid on glutamate-gated current would probably dominate membrane potential modulation. Moreover, should further investigation demonstrate the presence of ASICs in HCs, these channels would provide a H+ conducting pathway that might contribute to H+ modulation in the synaptic cleft (Hirasawa & Kaneko, 2003; Vessey et al. 2005; Cadetti & Thoreson, 2006) since ASICs are more permeable to H+ than Na+ (Waldmann et al. 1997). Overall, acidification of the HC environment would have complex effects on the light response. As HCs contribute to the receptive field surround of neurons in the retina, modulation of ion channels in HCs may have profound effects on visual processing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs M.E.M. Kelly and W.H. Baldridge for equipment and animal use, respectively. We also thank Bryan Daniels for assistance with animal care. M.G.J. was supported by the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation (NSHRF). Research was supported by a CIHR grant to S.B. (MOP-10968).

References

- Barnes S. Modulation of vertebrate retinal function by pH. In: Kaila K, Ransom BR, editors. pH and Brain Function. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1998. pp. 491–505. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S, Bui Q. Modulation of calcium-activated chloride current via pH-induced changes of calcium channel properties in cone photoreceptors. J Neurosci. 1991;11:4015–4023. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-12-04015.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S, Merchant V, Mahmud F. Modulation of transmission gain by protons at the photoreceptor output synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10081–10085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron A, Waldmann R, Lazdunski M. ASIC-like, proton-activated currents in rat hippocampal neurons. J Physiol. 2002;539:485–494. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.014837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor DA, Fuortes MG, O'Bryan PM. Receptive fields of cones in the retina of the turtle. J Physiol. 1971;214:265–294. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevensee MO, Boron WF. Thermodynamics and physiology of cellular pH regulation. In: Kaila K, Ransom BR, editors. pH and Brain Function. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1998. pp. 173–231. [Google Scholar]

- Borgula GA, Karwoski CJ, Steinberg RH. Light-evoked changes in extracellular pH in frog retina. Vis Res. 1989;29:1069–1077. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(89)90054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman EJ, Siebers A, Altendorf K. Bafilomycins: a class of inhibitors of membrane ATPases from microorganisms, animal cells, and plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;85:7972–7976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockway LM, Zhou Z-H, Bubien JK, Jovov B, Benos DJ, Keyser KT. Rabbit retinal neurons and glia express a variety of ENaC/DEG subunits. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C126–C134. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00457.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukauskas FF, Verselis VK. Gap junction channel gating. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1662:42–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadetti L, Thoreson WB. Feedback effects of horizontal cell membrane potential on cone calcium currents studied with simultaneous recordings. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:1992–1995. doi: 10.1152/jn.01042.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesler M. Regulation and modulation of pH in the brain. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1183–1221. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connaughton VP, Dowling JE. Comparative morphology of distal neurons in larval and adult zebrafish retinas. Vision Res. 1998;38:13–18. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(97)00146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCoursey TE. Voltage-gated proton channels and other proton transfer pathways. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:475–579. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries SH. Exocytosed protons feedback to suppress the Ca2+ current in mammalian cone photoreceptors. Neuron. 2001;32:1107–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00535-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries SH, Schwartz EA. Modulation of an electrical synapse between solitary pairs of catfish horizontal cells by dopamine and second messengers. J Physiol. 1989;414:351–375. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries SH, Schwartz EA. Hemi-gap-junction channels in solitary horizontal cells of the catfish retina. J Physiol. 1992;445:201–230. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp018920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Weille JR, Bassilana F, Lazdunski M, Waldmann R. Identification, functional expression and chromosomal localisation of a sustained human proton-gated channel. FEBS Lett. 1998;433:257–260. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00916-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon DB, Takahashi K-I, Copenhagen DR. l-Glutamate suppresses HVA calcium current in catfish horizontal cells by raising intracellular proton concentration. Neuron. 1993;11:267–277. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90183-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitriev AV, Mangel SC. A circadian clock regulates the pH of the fish retina. J Physiol. 2000;522:77–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.0077m.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dmitriev AV, Mangel SC. Circadian clock regulation of pH in the rabbit retina. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2897–2902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02897.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling JE. The Retina: an Approachable Part of the Brain. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ettaiche M, Deval E, Cougnon M, Lazdunski M, Voilley N. Silencing acid-sensing ion channel 1a alters cone-mediated retinal function. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5800–5809. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0344-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettaiche M, Guy N, Hofman P, Lazdunski M, Waldmann R. Acid-sensing ion channel 2 is important for retinal function and protects against light-induced retinal degeneration. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1005–1012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4698-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson ECGM, Weiler R, Vaney DI. pH-gated dopaminergic modulation of horizontal cell gap junctions in mammalian retina. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1994;255:67–72. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugh-Scheidt L, Ripps H. pH regulation in horizontal cells of the skate retina. Exp Eye Res. 1998;66:449–463. doi: 10.1006/exer.1997.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa H, Kaneko A. pH changes in the invaginating synaptic cleft mediate feedback from horizontal cells to cone photoreceptors by modulating Ca2+ channels. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122:657–671. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko A, Tachibana M. Effects of l-glutamate on the anomalous rectifier potassium current in horizontal cells of Carassius auratus retina. J Physiol. 1985;358:169–182. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellenberger S, Schild L. Epithelial sodium channel/degenerin family of ion channels: a variety of functions for a shared structure. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:735–767. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klooster J, Studholme KM, Yazulla S. Localization of the AMPA subunit GluR2 in the outer plexiform layer of goldfish retina. J Comp Neurol. 2001;441:155–167. doi: 10.1002/cne.1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasater EM. Ionic currents of cultured horizontal cells isolated from white perch retina. J Neurophysiol. 1986;55:499–513. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.55.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley S, LeTissier P, Robbins J. The discovery and characterization of a proton-gated sodium current in rat retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1013–1022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3191-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchow RP, Qian H, Ripps H. A novel action of quinine and quinidine on the membrane conductance of neurons from the vertebrate retina. J Gen Physiol. 1994;104:1039–1055. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.6.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley B, Wen R. Extracellular pH in the isolated retina of the toad in darkness and during illumination. J Physiol. 1989;419:353–378. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peracchia C. Chemical gating of gap junction channels: Roles of calcium, pH and calmodulin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1662:61–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raviola E, Gilula NB. Intramembrane organization of specialized contacts in the outer plexiform layer of the retina. J Cell Biol. 1975;65:192–222. doi: 10.1083/jcb.65.1.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabirov RZ, Okada Y, Oiki S. Two-sided action of protons on an inward rectifier K+ channel (IRK1) Pflugers Arch. 1997;433:428–434. doi: 10.1007/s004240050296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz K, Janssen-Beinhold U, Weiler R. Selective synaptic distribution of AMPA and kainate receptor subunits in the outer plexiform layer of the carp retina. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:433–449. doi: 10.1002/cne.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingai R, Christensen BN. Excitable properties and voltage-sensitive ion conductances of horizontal cells isolated from catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) retina. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:32–49. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somjen GG, Tombaugh GC. pH modulation of neuronal excitability and central nervous system functions. In: Kaila K, Ransom BR, editors. pH and Brain Function. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1998. pp. 373–394. [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana M. Ionic currents of solitary horizontal cells isolated from goldfish retina. J Physiol. 1983;345:329–351. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachibana M. Permeability changes induced by l-glutamate in solitary retinal horizontal cells isolated from Carassius auratus. J Physiol. 1985;358:153–167. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K-I, Copenhagen DR. Intracellular alkalinization enhances inward rectifier K+ current in retinal horizontal cells of catfish. Zool Sci. 1995;12:29–34. doi: 10.2108/zsj.12.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K-I, Dixon DB, Copenhagen DR. Modulation of a sustained calcium current by intracellular pH in horizontal cells of fish retina. J Gen Physiol. 1993;101:695–714. doi: 10.1085/jgp.101.5.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamalu F, Chiba C, Saito T. Gap junctional coupling between progenitor cells at the retinal margin of adult goldfish. J Neurobiol. 2001;48:204–214. doi: 10.1002/neu.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh GC, Somjen GG. pH modulation of voltage-gated ion channels. In: Kaila K, Ransom BR, editors. pH and Brain Function. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1998. pp. 395–416. [Google Scholar]

- Traynelis SF. pH modulation of ligand-gated ion channels. In: Kaila K, Ransom BR, editors. pH and Brain Function. New York: Wiley-Liss; 1998. pp. 417–446. [Google Scholar]

- Vessey JP, Stratis AK, Daniels BA, Da Silva N, Jonz MG, Lalonde MR, Baldridge WH, Barnes S. Proton-mediated feedback inhibition of presynaptic calcium channels at the cone photoreceptor synapse. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4108–4117. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5253-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldmann R, Champigny G, Bassilana F, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. A proton-gated cation channel involved in acid-sensing. Nature. 1997;386:173–177. doi: 10.1038/386173a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wemmie JA, Price MP, Welsh MJ. Acid-sensing ion channels: advances, questions and therapeutic opportunities. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Christensen BN. Proton inhibition of the NMDA-gated channel in isolated catfish cone horizontal cells. Vis Res. 1996;36:1521–1528. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(95)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto F, Borgula GA, Steinberg RH. Effects of light and darkness on pH outside rod photoreceptors in the cat retina. Exp Eye Res. 1992;54:685–697. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(92)90023-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X-L. Characterization of receptors for glutamate and GABA in retinal neurons. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;73:127–150. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G, Chanchevalap S, Cui N, Jiang C. Effects of intra- and extracellular acidifications on single channel Kir2.3 currents. J Physiol. 1999;516:699–710. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0699u.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]